The Meaning of Life According to Viktor Frankl

The meaning of life according to Viktor Frankl

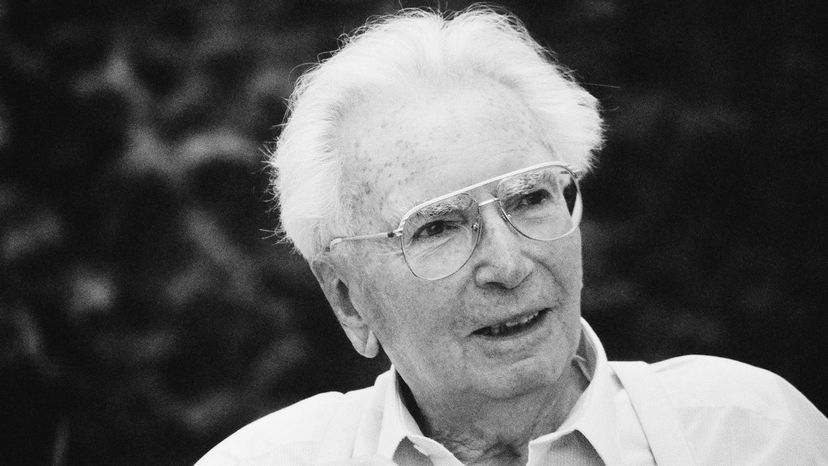

Viktor Frankl published “ Man’s Search for Meaning “in 1945. It inspired millions of people to identify their attitudes towards life. Frankl lived through the horrors of the Holocaust, a prisoner in Auschwitz and Dachau. He overcame it stoically and it laid the foundation of a very personal type of therapy, logotherapy .

Also, the loss of his family clarified for him that his purpose in this world was simply to help others find their own purpose in life . There were three very specific points to it, however:

- Work day by day with motivation.

- Live from a perspective of love.

- Have courage at all times in adversity.

Let’s see below how this can help us find our purpose in life.

Live with decision

We’ve all seen before: p eople who handle very tough circumstances with positivity and motivation. How do they do that? We all share the same biological structures, but what sets us apart from these people is their determination. Being determined to achieve something, overcome all obstacles and fight for what we want, however small, will help us clarify our purpose in each stage of our life.

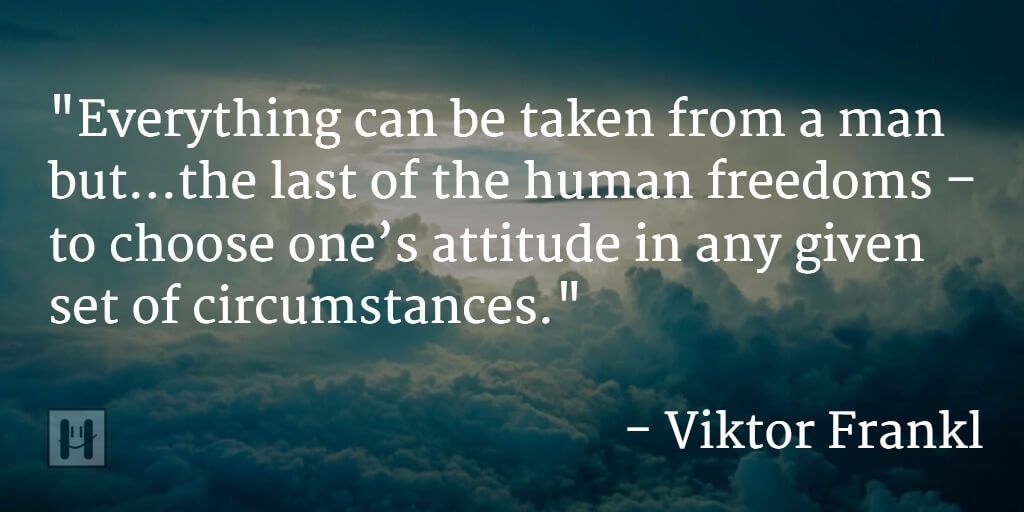

“Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.” -Viktor Frankl-

Viktor Frankl Understanding of Life

- Categories: Church Psychoanalytic Theory

About this sample

Words: 805 |

Published: Nov 8, 2019

Words: 805 | Pages: 2 | 5 min read

Works Cited:

- Ham, L. S., & Hope, D. A. (2006). College students and problematic drinking: A review of the literature. Clinical psychology review, 26(6), 872-888.

- Montana, J. (2015). Understanding social anxiety disorder. Positive Health, 217, 2-5.

- Thomasson, M., & Psouni, E. (2016). The Relationship Between Social Anxiety and Academic Functioning: A Systematic Review. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 45(6), 455-469.

- Uncommon Help. (n.d.). How to deal with social anxiety. Retrieved from https://www.uncommonhelp.me/articles/social-anxiety/

- Van Ameringen, M., Mancini, C., & Farvolden, P. (2003). The impact of anxiety disorders on educational achievement. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 17(5), 561-571.

- Zvolensky, M. J., Bernstein, A., Sachs-Ericsson, N., Schmidt, N. B., & Buckner, J. D. (2006). Lifetime associations between cannabis, use, abuse, and dependence and panic attacks in a representative sample. Journal of psychiatric research, 40(8), 848-855.

- Zvolensky, M. J., Cougle, J. R., Bonn-Miller, M. O., Norberg, M. M., & Johnson, K. A. (2010). Anxiety sensitivity and the subjective effects of alcohol: A laboratory examination. Addictive behaviors, 35(7), 593-599.

- Zvolensky, M. J., Gibson, L. E., Vujanovic, A. A., Gregor, K. L., Bernstein, A., Kahler, C., ... & Brown, R. A. (2008). Impact of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder on early smoking lapse and relapse during a self-guided quit attempt among community-recruited daily smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 10(8), 1415-1427.

- Zvolensky, M. J., Vujanovic, A. A., Bernstein, A., Bonn-Miller, M. O., & Marshall, E. C. (2007). Marijuana use motives: A confirmatory test and evaluation among young adult marijuana users. Addictive Behaviors, 32(12), 3122-3130.

- Zlomke, K. R., & Hahn, K. S. (2010). Cognitive emotion regulation strategies: Gender differences and associations to worry. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(4), 408-413.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: Religion Psychology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1213 words

3 pages / 1549 words

3 pages / 1296 words

1 pages / 597 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Psychoanalytic Theory

Erik Erikson’s was a follower of Jean Piaget and his work/theory was inspired by Piaget and with the work he saw Piaget did, Erikson wanted to expand his theory, but with a different focus. Erik Erikson came up with the [...]

Dr. Barbara LoFrisco, a professor at the University of South Florida, once said, “If you understand why something is important, not only will you be more motivated to understand it, but you will also be able to put your new [...]

Chu, Q., Grühn, D., & Holland, A. M. (2018). Before I die: The impact of time horizon and age on bucket-list goals. GeroPsych: The Journal of Gerontopsychology and Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(3), 151–162. Education

Protagonists in most of Robert Browning’s monologues are psychologically twisted individuals, and Porphyria’s Lover is arguably the one with a psychoanalytic perspective. This essay seeks to discuss and apply Sigmund Freud’s [...]

Psychology is the scientific study of the human mind. There are many theorists that believe there are different approaches to psychology, this essay will be focusing on two of those. The two theoretical approaches that this [...]

Psychodynamic Theory is a collection of many psychological theorists which emphasize the importance of drives and forces in human functioning which is unconscious drives. This theory emphasizes that childhood experience is the [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Yes to Life, in Spite of Everything: Viktor Frankl’s Lost Lectures on Moving Beyond Optimism and Pessimism to Find the Deepest Source of Meaning

By maria popova.

“To decide whether life is worth living is to answer the fundamental question of philosophy,” Albert Camus wrote in his classic 119-page essay The Myth of Sisyphus in 1942. “Everything else… is child’s play; we must first of all answer the question.”

Sometimes, life asks this question not as a thought experiment but as a gauntlet hurled with the raw brutality of living.

That selfsame year, the young Viennese neurologist and psychiatrist Viktor Frankl (March 26, 1905–September 2, 1997) was taken to Auschwitz along with more than a million human beings robbed of the basic right to answer this question for themselves, instead deemed unworthy of living. Some survived by reading . Some through humor . Some by pure chance. Most did not. Frankl lost his mother, his father, and his brother to the mass murder in the concentration camps. His own life was spared by the tightly braided lifeline of chance, choice, and character.

A mere eleven months after surviving the unsurvivable, Frankl took up the elemental question at the heart of Camus’s philosophical parable in a set of lectures, which he himself edited into a slim, potent book published in Germany in 1946, just as he was completing Man’s Search for Meaning .

As our collective memory always tends toward amnesia and erasure — especially of periods scarred by civilizational shame — these existential infusions of sanity and lucid buoyancy fell out of print and were soon forgotten. Eventually rediscovered — as is also the tendency of our collective memory when the present fails us and we must lean for succor on the life-tested wisdom of the past — they are now published in English for the first time as Yes to Life: In Spite of Everything ( public library ).

Frankl begins by considering the question of whether life is worth living through the central fact of human dignity. Noting how gravely the Holocaust disillusioned humanity with itself, he cautions against the defeatist “end-of-the-world” mindset with which many responded to this disillusionment, but cautions equally against the “blithe optimism” of previous, more naïve eras that had not yet faced this gruesome civilizational mirror reflecting what human beings are capable of doing to one another. Both dispositions, he argues, stem from nihilism. In consonance with his colleague and contemporary Erich Fromm’s insistence that we can only transcend the shared laziness of optimism and pessimism through rational faith in the human spirit , Frankl writes:

We cannot move toward any spiritual reconstruction with a sense of fatalism such as this.

Generations and myriad cultural upheavals before Zadie Smith observed that “progress is never permanent, will always be threatened, must be redoubled, restated and reimagined if it is to survive,” Frankl considers what “progress” even means, emphasizing the centrality of our individual choices in its constant revision:

Today every impulse for action is generated by the knowledge that there is no form of progress on which we can trustingly rely. If today we cannot sit idly by, it is precisely because each and every one of us determines what and how far something “progresses.” In this, we are aware that inner progress is only actually possible for each individual, while mass progress at most consists of technical progress, which only impresses us because we live in a technical age.

Insisting that it takes a measure of moral strength not to succumb to nihilism, be it that of the pessimist or of the optimist, he exclaims:

Give me a sober activism anytime, rather than that rose-tinted fatalism! How steadfast would a person’s belief in the meaningfulness of life have to be, so as not to be shattered by such skepticism. How unconditionally do we have to believe in the meaning and value of human existence, if this belief is able to take up and bear this skepticism and pessimism? […] Through this nihilism, through the pessimism and skepticism, through the soberness of a “new objectivity” that is no longer that “new” but has grown old, we must strive toward a new humanity.

Sophie Scholl, upon whom chance did not smile as favorably as it did upon Frankl, affirmed this notion with her insistence that living with integrity and belief in human goodness is the wellspring of courage as she courageously faced her own untimely death in the hands of the Nazis. But while the Holocaust indisputably disenchanted humanity, Frankl argues, it also indisputably demonstrated “that what is human is still valid… that it is all a question of the individual human being.” Looking back on the brutality of the camps, he reflects:

What remained was the individual person, the human being — and nothing else. Everything had fallen away from him during those years: money, power, fame; nothing was certain for him anymore: not life, not health, not happiness; all had been called into question for him: vanity, ambition, relationships. Everything was reduced to bare existence. Burnt through with pain, everything that was not essential was melted down — the human being reduced to what he was in the last analysis: either a member of the masses, therefore no one real, so really no one — the anonymous one, a nameless thing (!), that “he” had now become, just a prisoner number; or else he melted right down to his essential self.

In a sentiment that bellows from the hallways of history into the great vaulted temple of timeless truth, he adds:

Everything depends on the individual human being, regardless of how small a number of like-minded people there is, and everything depends on each person, through action and not mere words, creatively making the meaning of life a reality in his or her own being.

Frankl then turns to the question of finding a sense of meaning when the world gives us ample reasons to view life as meaningless — the question of “continuing to live despite persistent world-weariness.” Writing in the post-war pre-dawn of the golden age of consumerism, which has built a global economy by continually robbing us of the sense of meaning and selling it back to us at the price of the product, Frankl first dismantles the notion that meaning is to be found in the pursuit and acquisition of various pleasures:

Let us imagine a man who has been sentenced to death and, a few hours before his execution, has been told he is free to decide on the menu for his last meal. The guard comes into his cell and asks him what he wants to eat, offers him all kinds of delicacies; but the man rejects all his suggestions. He thinks to himself that it is quite irrelevant whether he stuffs good food into the stomach of his organism or not, as in a few hours it will be a corpse. And even the feelings of pleasure that could still be felt in the organism’s cerebral ganglia seem pointless in view of the fact that in two hours they will be destroyed forever. But the whole of life stands in the face of death, and if this man had been right, then our whole lives would also be meaningless, were we only to strive for pleasure and nothing else — preferably the most pleasure and the highest degree of pleasure possible. Pleasure in itself cannot give our existence meaning; thus the lack of pleasure cannot take away meaning from life, which now seems obvious to us.

He quotes a short verse by the great Indian poet and philosopher Rabindranath Tagore — the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize, Einstein’s onetime conversation partner in contemplating science and spirituality, and a man who thought deeply about human nature :

I slept and dreamt that life was joy. I awoke and saw that life was duty. I worked — and behold, duty was joy.

In consonance with Camus’s view of happiness as a moral obligation — an outcome to be attained not through direct pursuit but as a byproduct of living with authenticity and integrity — Frankl reflects on Tagore’s poetic point:

So, life is somehow duty, a single, huge obligation. And there is certainly joy in life too, but it cannot be pursued, cannot be “willed into being” as joy; rather, it must arise spontaneously, and in fact, it does arise spontaneously, just as an outcome may arise: Happiness should not, must not, and can never be a goal, but only an outcome; the outcome of the fulfillment of that which in Tagore’s poem is called duty… All human striving for happiness, in this sense, is doomed to failure as luck can only fall into one’s lap but can never be hunted down.

In a sentiment James Baldwin would echo two decades later in his superb forgotten essay on the antidote to the hour of despair and life as a moral obligation to the universe , Frankl turns the question unto itself:

At this point it would be helpful [to perform] a conceptual turn through 180 degrees, after which the question can no longer be “What can I expect from life?” but can now only be “What does life expect of me?” What task in life is waiting for me? Now we also understand how, in the final analysis, the question of the meaning of life is not asked in the right way, if asked in the way it is generally asked: it is not we who are permitted to ask about the meaning of life — it is life that asks the questions, directs questions at us… We are the ones who must answer, must give answers to the constant, hourly question of life, to the essential “life questions.” Living itself means nothing other than being questioned; our whole act of being is nothing more than responding to — of being responsible toward — life. With this mental standpoint nothing can scare us anymore, no future, no apparent lack of a future. Because now the present is everything as it holds the eternally new question of life for us.

Frankl adds a caveat of tremendous importance — triply so in our present culture of self-appointed gurus, self-help demagogues, and endless podcast feeds of interviews with accomplished individuals attempting to distill a universal recipe for self-actualization:

The question life asks us, and in answering which we can realize the meaning of the present moment, does not only change from hour to hour but also changes from person to person: the question is entirely different in each moment for every individual. We can, therefore, see how the question as to the meaning of life is posed too simply, unless it is posed with complete specificity, in the concreteness of the here and now. To ask about “the meaning of life” in this way seems just as naive to us as the question of a reporter interviewing a world chess champion and asking, “And now, Master, please tell me: which chess move do you think is the best?” Is there a move, a particular move, that could be good, or even the best, beyond a very specific, concrete game situation, a specific configuration of the pieces?

What emerges from Frankl’s inversion of the question is the sense that, just as learning to die is learning to meet the universe on its own terms , learning to live is learning to meet the universe on its own terms — terms that change daily, hourly, by the moment:

One way or another, there can only be one alternative at a time to give meaning to life, meaning to the moment — so at any time we only need to make one decision about how we must answer, but, each time, a very specific question is being asked of us by life. From all this follows that life always offers us a possibility for the fulfillment of meaning, therefore there is always the option that it has a meaning. One could also say that our human existence can be made meaningful “to the very last breath”; as long as we have breath, as long as we are still conscious, we are each responsible for answering life’s questions.

With this symphonic prelude, Frankl arrives at the essence of what he discovered about the meaning of life in his confrontation with death — a central fact of being at which a great many of humanity’s deepest seers have arrived via one path or another: from Rilke, who so passionately insisted that “death is our friend precisely because it brings us into absolute and passionate presence with all that is here, that is natural, that is love,” to physicist Brian Greene, who so poetically nested our search for meaning into our mortality into the most elemental fact of the universe . Frankl writes:

The fact, and only the fact, that we are mortal, that our lives are finite, that our time is restricted and our possibilities are limited, this fact is what makes it meaningful to do something, to exploit a possibility and make it become a reality, to fulfill it, to use our time and occupy it. Death gives us a compulsion to do so. Therefore, death forms the background against which our act of being becomes a responsibility. […] Death is a meaningful part of life, just like human suffering. Both do not rob the existence of human beings of meaning but make it meaningful in the first place. Thus, it is precisely the uniqueness of our existence in the world, the irretrievability of our lifetime, the irrevocability of everything with which we fill it — or leave unfulfilled — that gives our existence significance. But it is not only the uniqueness of an individual life as a whole that gives it importance, it is also the uniqueness of every day, every hour, every moment that represents something that loads our existence with the weight of a terrible and yet so beautiful responsibility! Any hour whose demands we do not fulfill, or fulfill halfheartedly, this hour is forfeited, forfeited “for all eternity.” Conversely, what we achieve by seizing the moment is, once and for all, rescued into reality, into a reality in which it is only apparently “canceled out” by becoming the past. In truth, it has actually been preserved, in the sense of being kept safe. Having been is in this sense perhaps even the safest form of being. The “being,” the reality that we have rescued into the past in this way, can no longer be harmed by transitoriness.

In the remainder of the slender and splendid Yes to Life , Frankl goes on to explore how the imperfections of human nature add to, rather than subtract from, the meaningfulness of our lives and what it means for us to be responsible for our own existence. Complement it with Mary Shelley, writing two centuries ago about a pandemic-savaged world, on what makes life worth living , Walt Whitman contemplating this question after surviving a paralytic stroke, and a vitalizing cosmic antidote to the fear of death from astrophysicist and poet Rebecca Elson, then revisit Frankl on humor as lifeline to sanity and survival .

— Published May 17, 2020 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2020/05/17/yes-to-life-in-spite-of-everything-viktor-frankl/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, books culture philosophy psychology viktor frankl, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

There's More to Life Than Being Happy

Meaning comes from the pursuit of more complex things than happiness

"It is the very pursuit of happiness that thwarts happiness."

In September 1942, Viktor Frankl, a prominent Jewish psychiatrist and neurologist in Vienna, was arrested and transported to a Nazi concentration camp with his wife and parents. Three years later, when his camp was liberated, most of his family, including his pregnant wife, had perished -- but he, prisoner number 119104, had lived. In his bestselling 1946 book, Man's Search for Meaning , which he wrote in nine days about his experiences in the camps, Frankl concluded that the difference between those who had lived and those who had died came down to one thing: Meaning, an insight he came to early in life. When he was a high school student , one of his science teachers declared to the class, "Life is nothing more than a combustion process, a process of oxidation." Frankl jumped out of his chair and responded, "Sir, if this is so, then what can be the meaning of life?"

As he saw in the camps, those who found meaning even in the most horrendous circumstances were far more resilient to suffering than those who did not. "Everything can be taken from a man but one thing," Frankl wrote in Man's Search for Meaning , "the last of the human freedoms -- to choose one's attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one's own way."

Frankl worked as a therapist in the camps, and in his book, he gives the example of two suicidal inmates he encountered there. Like many others in the camps, these two men were hopeless and thought that there was nothing more to expect from life, nothing to live for. "In both cases," Frankl writes, "it was a question of getting them to realize that life was still expecting something from them; something in the future was expected of them." For one man, it was his young child, who was then living in a foreign country. For the other, a scientist, it was a series of books that he needed to finish. Frankl writes:

This uniqueness and singleness which distinguishes each individual and gives a meaning to his existence has a bearing on creative work as much as it does on human love. When the impossibility of replacing a person is realized, it allows the responsibility which a man has for his existence and its continuance to appear in all its magnitude. A man who becomes conscious of the responsibility he bears toward a human being who affectionately waits for him, or to an unfinished work, will never be able to throw away his life. He knows the "why" for his existence, and will be able to bear almost any "how."

In 1991, the Library of Congress and Book-of-the-Month Club listed Man's Search for Meaning as one of the 10 most influential books in the United States. It has sold millions of copies worldwide. Now, over twenty years later, the book's ethos -- its emphasis on meaning, the value of suffering, and responsibility to something greater than the self -- seems to be at odds with our culture, which is more interested in the pursuit of individual happiness than in the search for meaning. "To the European," Frankl wrote, "it is a characteristic of the American culture that, again and again, one is commanded and ordered to 'be happy.' But happiness cannot be pursued; it must ensue. One must have a reason to 'be happy.'"

According to Gallup , the happiness levels of Americans are at a four-year high -- as is, it seems, the number of best-selling books with the word "happiness" in their titles. At this writing, Gallup also reports that nearly 60 percent all Americans today feel happy, without a lot of stress or worry. On the other hand, according to the Center for Disease Control , about 4 out of 10 Americans have not discovered a satisfying life purpose. Forty percent either do not think their lives have a clear sense of purpose or are neutral about whether their lives have purpose. Nearly a quarter of Americans feel neutral or do not have a strong sense of what makes their lives meaningful. Research has shown that having purpose and meaning in life increases overall well-being and life satisfaction, improves mental and physical health, enhances resiliency, enhances self-esteem, and decreases the chances of depression. On top of that, the single-minded pursuit of happiness is ironically leaving people less happy, according to recent research . "It is the very pursuit of happiness," Frankl knew, "that thwarts happiness."

This is why some researchers are cautioning against the pursuit of mere happiness. In a new study , which will be published this year in a forthcoming issue of the Journal of Positive Psychology , psychological scientists asked nearly 400 Americans aged 18 to 78 whether they thought their lives were meaningful and/or happy. Examining their self-reported attitudes toward meaning, happiness, and many other variables -- like stress levels, spending patterns, and having children -- over a month-long period, the researchers found that a meaningful life and happy life overlap in certain ways, but are ultimately very different. Leading a happy life, the psychologists found, is associated with being a "taker" while leading a meaningful life corresponds with being a "giver."

"Happiness without meaning characterizes a relatively shallow, self-absorbed or even selfish life, in which things go well, needs and desire are easily satisfied, and difficult or taxing entanglements are avoided," the authors write.

How do the happy life and the meaningful life differ? Happiness, they found, is about feeling good. Specifically, the researchers found that people who are happy tend to think that life is easy, they are in good physical health, and they are able to buy the things that they need and want. While not having enough money decreases how happy and meaningful you consider your life to be, it has a much greater impact on happiness. The happy life is also defined by a lack of stress or worry.

Most importantly from a social perspective, the pursuit of happiness is associated with selfish behavior -- being, as mentioned, a "taker" rather than a "giver." The psychologists give an evolutionary explanation for this: happiness is about drive reduction. If you have a need or a desire -- like hunger -- you satisfy it, and that makes you happy. People become happy, in other words, when they get what they want. Humans, then, are not the only ones who can feel happy. Animals have needs and drives, too, and when those drives are satisfied, animals also feel happy, the researchers point out.

"Happy people get a lot of joy from receiving benefits from others while people leading meaningful lives get a lot of joy from giving to others," explained Kathleen Vohs, one of the authors of the study, in a recent presentation at the University of Pennsylvania. In other words, meaning transcends the self while happiness is all about giving the self what it wants. People who have high meaning in their lives are more likely to help others in need. "If anything, pure happiness is linked to not helping others in need," the researchers, which include Stanford University's Jennifer Aaker and Emily Garbinsky, write.

What sets human beings apart from animals is not the pursuit of happiness, which occurs all across the natural world, but the pursuit of meaning, which is unique to humans, according to Roy Baumeister, the lead researcher of the study and author, with John Tierney, of the recent book Willpower: Rediscovering the Greatest Human Strength . Baumeister, a social psychologists at Florida State University, was named an ISI highly cited scientific researcher in 2003.

The study participants reported deriving meaning from giving a part of themselves away to others and making a sacrifice on behalf of the overall group. In the words of Martin E. P. Seligman, one of the leading psychological scientists alive today, in the meaningful life "you use your highest strengths and talents to belong to and serve something you believe is larger than the self." For instance, having more meaning in one's life was associated with activities like buying presents for others, taking care of kids, and arguing. People whose lives have high levels of meaning often actively seek meaning out even when they know it will come at the expense of happiness. Because they have invested themselves in something bigger than themselves, they also worry more and have higher levels of stress and anxiety in their lives than happy people. Having children, for example, is associated with the meaningful life and requires self-sacrifice, but it has been famously associated with low happiness among parents, including the ones in this study. In fact, according to Harvard psychologist Daniel Gilbert, research shows that parents are less happy interacting with their children than they are exercising, eating, and watching television.

"Partly what we do as human beings is to take care of others and contribute to others. This makes life meaningful but it does not necessarily make us happy," Baumeister told me in an interview.

Meaning is not only about transcending the self, but also about transcending the present moment -- which is perhaps the most important finding of the study, according to the researchers. While happiness is an emotion felt in the here and now, it ultimately fades away, just as all emotions do; positive affect and feelings of pleasure are fleeting. The amount of time people report feeling good or bad correlates with happiness but not at all with meaning.

Meaning, on the other hand, is enduring. It connects the past to the present to the future. "Thinking beyond the present moment, into the past or future, was a sign of the relatively meaningful but unhappy life," the researchers write. "Happiness is not generally found in contemplating the past or future." That is, people who thought more about the present were happier, but people who spent more time thinking about the future or about past struggles and sufferings felt more meaning in their lives, though they were less happy.

Having negative events happen to you, the study found, decreases your happiness but increases the amount of meaning you have in life. Another study from 2011 confirmed this, finding that people who have meaning in their lives, in the form of a clearly defined purpose, rate their satisfaction with life higher even when they were feeling bad than those who did not have a clearly defined purpose. "If there is meaning in life at all," Frankl wrote, "then there must be meaning in suffering."

Which brings us back to Frankl's life and, specifically, a decisive experience he had before he was sent to the concentration camps. It was an incident that emphasizes the difference between the pursuit of meaning and the pursuit of happiness in life.

In his early adulthood, before he and his family were taken away to the camps, Frankl had established himself as one of the leading psychiatrists in Vienna and the world. As a 16-year-old boy, for example, he struck up a correspondence with Sigmund Freud and one day sent Freud a two-page paper he had written. Freud, impressed by Frankl's talent, sent the paper to the International Journal of Psychoanalysis for publication. "I hope you don't object," Freud wrote the teenager.

While he was in medical school, Frankl distinguished himself even further. Not only did he establish suicide-prevention centers for teenagers -- a precursor to his work in the camps -- but he was also developing his signature contribution to the field of clinical psychology: logotherapy, which is meant to help people overcome depression and achieve well-being by finding their unique meaning in life. By 1941, his theories had received international attention and he was working as the chief of neurology at Vienna's Rothschild Hospital, where he risked his life and career by making false diagnoses of mentally ill patients so that they would not, per Nazi orders, be euthanized.

That was the same year when he had a decision to make, a decision that would change his life. With his career on the rise and the threat of the Nazis looming over him, Frankl had applied for a visa to America, which he was granted in 1941. By then, the Nazis had already started rounding up the Jews and taking them away to concentration camps, focusing on the elderly first. Frankl knew that it would only be time before the Nazis came to take his parents away. He also knew that once they did, he had a responsibility to be there with his parents to help them through the trauma of adjusting to camp life. On the other hand, as a newly married man with his visa in hand, he was tempted to leave for America and flee to safety, where he could distinguish himself even further in his field.

As Anna S. Redsand recounts in her biography of Frankl, he was at a loss for what to do, so he set out for St. Stephan's Cathedral in Vienna to clear his head. Listening to the organ music, he repeatedly asked himself, "Should I leave my parents behind?... Should I say goodbye and leave them to their fate?" Where did his responsibility lie? He was looking for a "hint from heaven."

When he returned home, he found it. A piece of marble was lying on the table. His father explained that it was from the rubble of one of the nearby synagogues that the Nazis had destroyed. The marble contained the fragment of one of the Ten Commandments -- the one about honoring your father and your mother. With that, Frankl decided to stay in Vienna and forgo whatever opportunities for safety and career advancement awaited him in the United States. He decided to put aside his individual pursuits to serve his family and, later, other inmates in the camps.

RECOMMENDED

The wisdom that Frankl derived from his experiences there, in the middle of unimaginable human suffering, is just as relevant now as it was then: "Being human always points, and is directed, to something or someone, other than oneself -- be it a meaning to fulfill or another human being to encounter. The more one forgets himself -- by giving himself to a cause to serve or another person to love -- the more human he is."

Baumeister and his colleagues would agree that the pursuit of meaning is what makes human beings uniquely human. By putting aside our selfish interests to serve someone or something larger than ourselves -- by devoting our lives to "giving" rather than "taking" -- we are not only expressing our fundamental humanity, but are also acknowledging that that there is more to the good life than the pursuit of simple happiness.

Viktor Frankl

Only when the emotions work in terms of values can the individual feel pure joy ~Viktor Frankl ~

Happiness and Meaning: The Bottom Line

While Frankl rarely touches on the topic of the pursuit of happiness , he is very concerned with satisfaction and fulfillment in life. We can see this in his preoccupation with addressing depression, anxiety and meaninglessness. (Frankl 1992, p. 143).

In the pursuit of meaning, Frankl recommends three different kinds of experience: through deeds, the experience of values through some kind of medium (beauty through art, love through a relationship , etc.) or suffering . While the third is not necessarily in the absence of the first two, within Frankl’s frame of thought, suffering became an option through which to find meaning and experience values in life in the absence of the other two opportunities (Frankl 1992, p. 118).

Frankl famously stated that: “ Happiness must happen, and the same holds for success: you have to let it happen by not caring about it.” Though for Frankl, joy could never be an end to itself, it was an important byproduct of finding meaning in life. He points to studies where there is marked difference in life spans between “trained, tasked animals,” i.e., animals with a purpose, than “taskless, jobless animals.” And yet it is not enough simply to have something to do, rather what counts is the “manner in which one does the work” (Frankl 1986, p. 125)

Striving to find meaning in one’s life is the primary motivational force in man ~Viktor Frankl ~

Frankl’s Background

Victor Emil Frankl (1905 – 1997), Austrian neurologist, psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor, devoted his life to studying, understanding and promoting “meaning.”

His famous book, Man’s Search for Meaning , tells the story of how he survived the Holocaust by finding personal meaning in the experience, which gave him the will to live through it. He went on to later establish a new school of existential therapy called logotherapy, based in the premise that man’s underlying motivator in life is a “will to meaning ,” even in the most difficult of circumstances.

Frankl pointed to research indicating a strong relationship between “meaninglessness” and criminal behaviors, addictions and depression. Without meaning, people fill the void with hedonistic pleasures, power, materialism, hatred, boredom, or neurotic obsessions and compulsions. Some may also strive for Suprameaning, the ultimate meaning in life, a spiritual kind of meaning that depends solely on a greater power outside of personal or external control.

“ What man actually needs is not a tensionless state but rather the striving and struggling for some goal worthy of him. What he needs is not the discharge of tension at any cost, but the call of a potential meaning waiting to be fulfilled by him. ”

Viktor Frankl was an Austrian neurologist and psychologist who founded what he called the field of “Logotherapy”, which has been dubbed the “Third Viennese School of Psychology” (following Freud and Alder). Logotherapy developed in and through Frankl’s personal experience in the Theresienstadt Nazi concentration camp. The years spent there deeply affected his understanding of reality and the meaning of human life . His most popular book, Man’s Search for Meaning, chronicles his experience in the camp as well as the development of logotherapy. During his time there, he found that those around him who did not lose their sense of purpose and meaning in life were able to survive much longer than those who had lost their way. William James would have considered this life changing event to be a “crisis of meaning.”

Logotherapy

In The Will to Meaning, Frankl notes that “logotherapy aims to unlock the will to meaning in life.” More often than not, he found that people would ponder the meaning of life when for Frankl, it is very clear that, “it is life itself that asks questions of man.” Paradoxically, by abandoning the desire to have “freedom from” we take the “freedom to” make the “decision for” one’s unique and singular life task (Frankl 1988, p. 16).

Logotherapy developed in a context of extreme suffering, depression and sadness and so it is not surprising that Frankl focuses on a way out of these things. His experience showed him that life can be meaningful and fulfilling even in spite of the harshest circumstances. On the other hand, he also warns against the pursuit of hedonistic pleasures because of its tendency to distract people from their search for meaning in life.

Only when the emotions work in terms of values can the individual feel pure joy (Frankl 1986, p. 40).

In the pursuit of meaning, Frankl recommends three different kinds of experience : through deeds, the experience of values through some kind of medium (beauty through art, love through a relationship , etc.) or suffering. While the third is not necessarily in the absence of the first two, within Frankl’s frame of thought, suffering became an option through which to find meaning and experience values in life in the absence of the other two opportunities (Frankl 1992, p. 118).

Though for Frankl, joy could never be an end to itself, it was an important byproduct of finding meaning in life. He points to studies where there is marked difference in life spans between “trained, tasked animals,” i.e., animals with a purpose, than “taskless, jobless animals.” And yet it is not enough simply to have something to do, rather what counts is the “manner in which one does the work” (Frankl 1986, p. 125)

Responsibility

Human freedom is not a freedom from but freedom to (Frankl 1988, p. 16).

As mentioned above, Frankl sees our ability to respond to life and to be responsible to life as a major factor in finding meaning and therefore, fulfillment in life. In fact, he viewed responsibility to be the “essence of existence” (Frankl 1992, 114). He believed that humans were not simply the product of heredity and environment and that they had the ability to make decisions and take responsibility for their own lives. This “third element” of decision is what Frankl believed made education so important; he felt that education must be education towards the ability to make decisions, take responsibility and then become free to be the person you decide to be (Frankl 1986, p. xxv).

Individuality

Frankl is careful to state that he does not have a one-size-fits all answer to the meaning of life. His respect for human individuality and each person’s unique identity, purpose and passions does not allow him to do otherwise. And so he encourages people to answer life and find one’s own unique meaning in life. When posed the question of how this might be done, he quotes from Goethe: “How can we learn to know ourselves? Never by reflection but by action. Try to do your duty and you will soon find out what you are. But what is your duty? The demands of each day.” In quoting this, he points to the importance attached to the individual doing the work and the manner in which the job is done rather than the job or task itself (Frankl 1986, p. 56).

Frankl’s logotherapy utilizes several techniques to enhance the quality of one’s life. First is the concept of paradoxical Intention, wherethe therapist encourages the patient to intend or wish for, even if only for a second, precisely what they fear. This is especially useful for obsessive, compulsive and phobic conditions, as well as cases of underlying anticipatory anxiety.

The case of the sweating doctor

A young doctor had major hydrophobia. One day, meeting his chief on the street, as he extended his hand in greeting, he noticed that he was perspiring more than usual. The next time he was in a similar situation he expected to perspire again, and this anticipatory anxiety precipitated excessive sweating. It was a vicious circle … We advised our patient, in the event that his anticipatory anxiety should recur, to resolve deliberately to show the people whom he confronted at the time just how much he could really sweat.A week later he returned to report that whenever he met anyone who triggered his anxiety, he said to himself, “I only sweated out a little before, but now I’m going to pour out at least ten litres!” What was the result of this paradoxical resolution? After suffering from his phobia for four years, he was quickly able, after only one session, to free himself of it for good. (Frankl, 1967)

Dereflection

Another technique is that of dereflection, whereby the therapist diverts the patients away from their problems towards something else meaningful in the world. Perhaps the most commonly known use of this is for sexual dysfunction, since the more one thinks about potency during the sexual act, the less likely one is able to achieve it.

The following is a transcript from Frankl’s advice to Anna, 19-year old art student who displays severe symptoms of incipient schizophrenia. She considers herself as being confused and asks for help.

Patient: What is going on within me? Frankl: Don’t brood over yourself. Don’t inquire into the source of your trouble. Leave this to us doctors. We will steer and pilot you through the crisis. Well, isn’t there a goal beckoning you – say, an artistic assignment? Patient : But this inner turmoil …. Frankl: Don’t watch your inner turmoil, but turn your gaze to what is waiting for you. What counts is not what lurks in the depths, but what waits in the future, waits to be actualized by you…. Patient: But what is the origin of my trouble? Frankl: Don’t focus on questions like this. Whatever the pathological process underlying your psychological affliction may be, we will cure you. Therefore, don’t be concerned with the strange feelings haunting you. Ignore them until we make you get rid of them. Don’t watch them. Don’t fight them. Imagine, there are about a dozen great things, works which wait to be created by Anna, and there is no one who could achieve and accomplish it but Anna. No one could replace her in this assignment. They will be your creations, and if you don’t create them, they will remain uncreated forever… Patient: Doctor, I believe in what you say. It is a message which makes me happy.

Discernment of Meaning

Finally, the logotherapist tries to enlarge the patient’s discernment of meaning in at least three ways: creatively, experientially and attitudinally.

a) Meaning through creative values

Frankl writes that “The logotherapist’s role consists in widening and broadening the visual field of the patient so that the whole spectrum of meaning and values becomes conscious and visible to him”. A major source of meaning is through the value of all that we create, achieve and accomplish.

b) Meaning through experiential values

Frankl writes “Let us ask a mountain-climber who has beheld the alpine sunset and is so moved by the splendor of nature that he feels cold shudders running down his spine – let us ask him whether after such an experience his life can ever again seem wholly meaningless” (Frankl,1965).

c) Meaning through attitudinal values

Frankl argued that we always have the freedom to find meaning through meaningful attitudes even in apparently meaningless situations. For example, an elderly, depressed patient who could not overcome the loss of his wife was helped by the following conversation with Frankl:

Frankl asked “What would have happened if you had died first, and your wife would have had to survive you.”

“Oh,” replied the patient, “for her this would have been terrible; how she would have suffered!”

Frankl continued, “You see such a suffering has been spared her; and it is you who have spared her this suffering; but now, you have to pay for it by surviving her and mourning her.” The man said no word, but shook Frankl’s hand and calmly left his office (Frankl, 1992).

Frankl’s surprising resilience amidst his experiences of extreme suffering and sadness speaks to how his theories may have helped him and those around him. As the alarming suicide and depression rates among young teenagers and adults in the United States continue, his call to answer life’s call through logotherapy may be a promising resource.

Our Related Articles

The next three scientists have also made substantial contributions to the literature on the science of happiness:

- Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

- Abraham Maslow

- Marie Jahoda

External Readings

- The Unheard Cry for Meaning: Psychotherapy and Humanism (Touchstone Books).

- The Will to Meaning: Foundations and Applications of Logotherapy (Meridian).

Bibliography

- Frankl, Victor (1992). Man’s Search for Meaning. (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Frankl, Victor (1986). The Doctor and the Soul. (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- Frankl, Victor (1967). Psychotherapy and Existentialism. New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

- Frankl, Victor (1988). The Will to Meaning: Foundations and Applications of Logotherapy. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

- Frankl, Victor (2000). Recollections: An Autobiography. New York, NY: Perseus Books.

Start Your Journey to Happiness. Register Now!

Pursuit-of-Happiness.org ©2024

Logotherapy: Viktor Frankl’s Theory of Meaning

When we bask in the glory of a sunset and reflect on creation or enjoy the embrace of a loved one, it provides meaning.

As we engage with our community, participate in creative endeavors, and support a cause greater than ourselves, we experience the value of life.

What is it then that brings meaning to life? What is it that makes those hard moments, the dark nights, and endless struggles worth the fight?

The quest to answer “what is the meaning of life?” has been around since the beginning of time. To find meaning in life can be seen as the primary motivation of each person, and the concept of logotherapy is based on that proposition.

In the following article, we will take a deep dive into the creation of logotherapy, research, techniques, and worksheets.

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our three Meaning & Valued Living Exercises for free . These creative, science-based exercises will help you learn more about your values, motivations, and goals and will give you the tools to inspire a sense of meaning in the lives of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

Logotherapy: a definition, who was viktor frankl, viktor frankl’s theory, research and empirical results, 3 techniques of logotherapy, 4 activities and worksheets, 6 famous quotes on life and meaning, 5 books on the topic, our meaning & valued living masterclass, a take-home message.

Logotherapy is often referred to as the “ third Viennese school of psychotherapy ,” and it originated in the 1930s as a response to both Freud’s psychoanalysis and Adler’s emphasis on power within society. It is more than just “therapy.” It is a philosophy for the spiritually lost and an education for those who are confused. It offers support in the face of suffering and healing for the sick (Guttmann, 2008).

Logotherapy examines the physical, psychological, and spiritual (noological) aspects of a human being, and it can be seen through the expression of an individual’s functioning. It is often regarded as a humanistic–existential school of thought but can also be used in conjunction with contemporary therapies (McMullin, 2000).

In contrast to Freud’s “ will to pleasure ” and Adler’s “ will to power ,” logotherapy is based on the idea that we are driven by a “ will to meaning ” or an inner desire to find purpose and meaning in life (Amelis & Dattilio, 2013).

As humans, we often respond to situations in the first two dimensions of functioning (physical/psychological) with conditioned and automatic reactions. Examples of these reactions include negative self-talk, irrational actions, outbursts, and negative emotions.

Animals also respond in the first two dimensions. It is the third dimension of functioning that separates humans from other species. This is the unique beauty of logotherapy.

While humans can survive just like animals living within the first two dimensions (satisfying physical needs and thinking), logotherapy offers a deeper connection to the soul and an opportunity to explore that which makes us uniquely human.

The spiritual dimension is one of meaning. The basic tenets of logotherapy are that

- human life has meaning,

- human beings long to experience their own sense of life meaning, and

- humans have the potential to experience meaning under any and every circumstance (Schulenberg, 2003).

The Austrian psychiatrist and neurologist was born March 26, 1905, and is best known for his psychological memoir Man’s Search for Meaning (2006) and as the father of logotherapy.

He published 40 books that have been translated into 50 languages, demonstrating that love, freedom, meaning, and responsibility transcend race, culture, religion, and continents.

His most famous memoir begins by outlining a personal experience through the gruesome Auschwitz concentration camps. The three years he spent in concentration camps became more than a story of survival. Frankl embodies the modern-day definition of resilience.

Download 3 Meaning & Valued Living Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to find meaning in life help and pursue directions that are in alignment with values.

Download 3 Free Meaning Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Frankl viewed logotherapy as a way to enhance existing therapies by emphasizing the “meaning-dimension” or spiritual dimension of human beings. Three philosophical and psychological concepts make up Frankl’s logotherapy: freedom of will, will to meaning, and meaning of life (Batthyany, 2019).

Freedom of will asserts that humans are free to decide and can take a stance toward both internal and external conditions. Freedom in this context is defined as a space to shape one’s own life within limits of specific possibilities. It provides the client with room for autonomy in the face of somatic or psychological illness. In essence, we are free to choose our responses no matter our circumstances.

Will to meaning states that humans are free to achieve goals and purposes in life. Frustration, aggression, addiction, depression, and suicidality arise when individuals cannot realize their “will to meaning.” As humans, our primary motive is to search for meaning or purpose in our lives. We are capable of surpassing pleasure and supporting pain for a meaningful cause.

Meaning in life is based on the idea that meaning is an objective reality rather than merely an illusion or personal perception. Humans have both freedom and responsibility to bring forth their best possible selves by realizing the meaning of the moment in every situation.

Can we find meaning under all circumstances, even unavoidable suffering? We can discover meaning in life through creative clues, experiential values, and attitudinal values (Lewis, 2011).

Viktor Frankl: Logotherapy and man’s search for meaning

Logotherapy has significant application to every dimension of an individual (the tri-dimensional ontology). Psychologically, logotherapy uses the specific techniques of paradoxical intention and dereflection to deal with problems of anxiety, compulsive disorders, obsessions, and phobias. These will be discussed in further detail in the next section.

Physiologically, logotherapy is an effective way to cope with suffering and physical pain or loss. Spiritually, logotherapy demonstrates that life has meaning or purpose when people suffer from the “existential vacuum” that we experience as boredom, apathy, emptiness, and depression (Frankl, 2006).

1. PTSD and acute stress

One of the most effective things about logotherapy is its ability to empower individuals, allowing them to be freed from their symptoms and increase their capacity to be proactive.

Since logotherapy was founded on a preface of suffering, it is a natural therapy for treating traumatic experiences. Logotherapy is a useful treatment for individuals with acute stress disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

In numerous case studies of clients with combat-related PTSD, logotherapy exercises that highlight the construct of meaning led to a significant decrease in symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression (Schiraldi, 2000). Research on logotherapy’s effectiveness for treating PTSD has mostly been established through qualitative research and case studies.

2. Alcohol and drug treatment

There are obvious parallels between the spiritual elements of Alcoholics Anonymous and the concepts of discovering personal meaning found in logotherapy.

Frankl (2006) discussed a “mass neurotic triad” of aggression, depression, and addiction that occurs when individuals experience an existential vacuum. This vacuum leads to violations of social norms, symptoms of stress, and addiction.

The treatment for this existential vacuum is, of course, to guide the client into discovering the freedom to choose, the will to find meaning, and the responsibility of living a purposeful life (Hutzell, 1990).

Logotherapy has been effective in reducing cravings and participation in drinking among alcoholics. Additionally, logotherapy groups successfully improved the meaning of life and mental health among wives of alcoholics (Cho, 2008).

Frankl would argue that when individuals can tap into their freedom, responsibility, and life purpose, there is no longer a need or desire for mind-altering substances like alcohol or drugs.

3. Anxiety and depression

Logotherapy has successfully been used to treat depression and anxiety. One study looked specifically at depression and stress among cervical cancer patients (Soetrisno & Moewardi, 2017).

Researchers measured cortisol levels (stress hormone) and scores from the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) among two groups of 15 patients. One group received logotherapy treatment for a total of six weeks (45-minute sessions once per week), and the control group received standard cancer treatment.

After six weeks, there was a significant decrease in BDI scores and levels of cortisol for the treatment group, while the control group had no change (Soetrisno & Moewardi, 2017). It makes sense that improving the meaning of life for cancer patients decreased their levels of stress and depression.

Logotherapy also successfully decreased measurable levels of suffering and increased the meaning of life in a group of adolescent cancer patients when compared with a matched control group (Kang et al., 2009).

Similarly, two-hour sessions of logotherapy among a group of 22 breast cancer patients significantly decreased BDI scores (Hagighi, Khodaei, and Sharifzadeh, 2012). This research demonstrated that logotherapy can be a beneficial treatment for individuals struggling through cancer or other major illnesses.

4. Group logotherapy

There is also significant research to support the use of logotherapy in group settings. Instructing both individuals and groups on the dimensions of responsibility, freedom, and values can help decrease suffering and increase various measures of psychological wellbeing.

When comparing the effectiveness of gestalt and logotherapy in a group setting of divorced women, logotherapy provided a more substantial decrease in depression, anxiety, and aggression (Yousefi, 2006).

Group logotherapy also led to increased psychological wellbeing, positive relationships, autonomy, personal growth, and mastery among mothers of children with intellectual disabilities (Faramarzi & Bavali, 2017).

There are similarities between the therapeutic techniques of logotherapy and both Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT).

1. Dereflection

The first technique is dereflection, which is aimed at helping clients focus attention away from problems and complaints and toward something positive. It is based on the concept of self-distancing and self-transcendence .

Practically speaking, it involves asking questions like “ What would your life be like without X problem? ”; “ If everything went perfectly in your life, what would that look like? ”; and “ Is there anything in your life you would die for? ”

2. Paradoxical intention

Paradoxical intention is an effective technique to use with phobias, fear, and anxiety.

The basis of this technique is that humor and ridicule can be useful when fear is paralyzing. Fear is removed when action/intention focuses on what is feared the most. For example, if a person struggles with a fear of rejection, they would purposely put themselves in positions where they would be rejected or told “no.”

An apt illustration is in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Rowling, 1999), where young students had to face their worst fears. To conquer their fear, they had to turn the terrifying thought into something laughable, such as a big spider on roller skates, thereby ridiculing and overcoming the paralyzing fear.

3. Socratic dialogue

Socratic dialogue is a tool in logotherapy that walks a client through a process of self-discovery in their own words.

It is different from Socratic questioning , which is often used in CBT. Socratic questioning breaks down anxious or negative thoughts, while Socratic dialogue is used to find meaning within a conversation. It allows the client to realize they already have the answers to their purpose, meaning, and freedom.

Our Positive Psychology Toolkit© contains over 400 tools, exercises and questionnaires to assist therapists, coaches and educators, to name a few. Some of these worksheets are described below.

1. Valued Living During Challenging Times

A perfect fit for Frankl’s logotherapy, the Valued Living During Challenging Times worksheet has clients reflect on a challenging circumstance and reconnect with personal values. Through this process, clients can find meaning in their suffering and become more resilient and tolerant of stress.

2. Passengers on the Bus group activity

The empirically tested metaphor “passengers on the bus” has been effectively used in ACT interventions. The Passengers on the Bus group activity uses role-play and debriefing to help clients learn to react to distressing situations in line with their values rather than choosing to avoid painful situations or act on their emotions.

3. A Value Tattoo

While logotherapy uses Socratic dialogue to find meaning, the Value Tattoo worksheet is helpful for clients who might find questions difficult or confronting. Instead of asking, “ What is most important in life? ” the client is encouraged to use creativity and imagine a tattoo that would be meaningful to them.

4. Find Your Purpose worksheet

This Find Your Purpose worksheet asks a series of basic questions designed to identify gifts, talents, skills, and abilities, which can ultimately reflect finding purpose in life. By finding your purpose and using your strengths in a positive way, you can create a lasting impact on the world around you and ultimately find meaning in life.

While finding the meaning of life seems to be at the forefront of logotherapy, Frankl argued that instead of asking this question, an individual should realize that they are the one being questioned.

He stated, “ It doesn’t really matter what we expected from life, but what life expected from us ” (Frankl, 1986).

Other notable quotes from Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning (2006) include:

When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.

Suffering is an ineradicable part of life, even as fate and death. Without suffering and death human life cannot be complete. For success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue, and it only does so as the unintended side-effect of one’s personal dedication to a cause greater than oneself or as the by-product of one’s surrender to a person other than oneself.

Related famous quotes include:

He who has a why to live for can bear with almost any how.

- Man’s Search for Meaning (2006) is the best place to start for a brief background on Viktor Frankl and a great introduction to logotherapy. ( Amazon )

- The Will to Meaning (Frankl, 2014) dives a bit deeper into the application of logotherapy ( Amazon )

- Frankl’s The Doctor and the Soul: From Psychotherapy to Logotherapy (1986) is the first book published after his release from Nazi concentration camps. He discusses that the fundamental human drive is not sex (Freud’s view) or the need for approval (Adler’s perspective) but the drive to have a meaningful life . ( Amazon )

- In the book Viktor Frankl’s Logotherapy , author Ann Graber (2019) focuses on the practical application of logotherapy and the effectiveness of using the spiritual dimension in existential therapy to find healing. ( Amazon )

- Joseph Fabry compiles work on logotherapy in the text Finding Meaning in Life: Logotherapy (1995) , which can specifically help clients with drug, alcohol, or life adjustment issues. ( Amazon )

For more reading, visit our post listing the 7 Best Books to Help You Find the Meaning of Life .

17 Tools To Encourage Meaningful, Value-Aligned Living

This 17 Meaning & Valued Living Exercises [PDF] pack contains our best exercises for helping others discover their purpose and live more fulfilling, value-aligned lives.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

The apparent parallels between positive psychology and Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy are endless.

While there are also notable differences, there is no denying that finding value and meaning in this journey of life leads to an array of positive outcomes.

The Meaning & Valued Living Masterclass provides an excellent background of positive psychology. It builds on the sailboat metaphor by emphasizing the types and paradox of meaning. By introducing practical exercises to find meaning and values, professionals can immediately apply techniques to address a wide range of issues.

One of the best things about positive psychology and the practicality of this masterclass is that it can improve life and wellbeing for those who are struggling, those who are suffering, and those who are looking to thrive.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others discover meaning, this collection contains 17 validated meaning tools for practitioners. Use them to help others choose directions for their lives in alignment with what is truly important to them.

Perhaps the question, “ what is the meaning of life? ” is not the right question for us.

Asking this question is like addressing the symptom rather than the actual problem.

If we worked on finding sources of meaning within our lives through both the good and bad experiences, then we could gain relief from existential issues and increase our resilience and wellbeing.

Once we find these potential sources of meaning and align them with our personal values and strengths, that will ultimately result in the most profound sense of joy and meaning possible.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Meaning & Valued Living Exercises for free .

- Amelis, M., & Dattilio, F. M. (2013). Enhancing cognitive behavior therapy with logotherapy: Techniques for clinical practice. Psychotherapy , 50 (3), 387–391.

- Batthyany, A. (2019). What is logotherapy/existential analysis? Logotherapy and existential analysis. Viktor Frankl Institut . Retrieved from https://www.viktorfrankl.org/logotherapy.html

- Cho, S. (2008). Effects of logo-autobiography program on meaning in life and mental health in the wives of alcoholics. Journal of Asian Nursing Research , 2 (2), 129–139.

- Fabry, J. B. (1995). Finding meaning in life: Logotherapy . Jason Aronson.

- Faramarzi, S., & Bavali, F. (2017). The effectiveness of group logotherapy to improve psychological wellbeing of mothers with intellectually disabled children. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities , 63 (1), 45–51.

- Frankl, V. E. (1986). The doctor and the soul. Penguin Random House.

- Frankl, V. E. (2006). Man’s search for meaning. Beacon Press.

- Frankl, V. E. (2014). The will to meaning: Foundations and applications of logotherapy (Expanded ed.). Plume.

- Graber, A. V. (2019). Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy: Method of choice in ecumenical pastoral psychology (2nd ed.). Wyndham Hall Press.

- Guttmann, D. (2008). Finding meaning in life, at midlife and beyond: Wisdom and spirit from logotherapy. Praege Inc.

- Hagighi, F., Khodaei, S., & Sharifzadeh, G. R. (2012). Effect of logotherapy group counseling on depression in breast cancer patients. Modern Care Journal , 9 (3), 165–172.

- Hutzell, R. R. (1990). An introduction to logotherapy. In P. A. Keller & S. R. Heyman (Eds.) Innovations in clinical practice: A source book. Professional Resource Exchange.

- Kang, K. A., Im, J. I., Kim, H. S., Kim, S. J., Song, M. K., & Songyong, S. (2009). The effect of logotherapy on the suffering, finding meaning, and spiritual wellbeing of adolescents with terminal cancer. Journal of Korean Academy of Child Health Nursing , 15 (2), 136–144.

- Lewis, M. H. (2011). Defiant power: An overview of Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy and existential analysis. Retrieved June 19, 2020, from www.defiantpower.com.

- McMullin, R. E. (2000). The new handbook of cognitive therapy techniques. Norton Press.

- Rowling, J. K. (1999). Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Schulenberg, S. E. (2003). Empirical research and logotherapy. Psychological Reports , 93 , 307–319.

- Schiraldi, G. R. (2000). Post traumatic stress disorder sourcebook: A guide to healing, recovery and growth. Lowell House.

- Soetrisno, S., & Moewardi. (2017). The effect of logotherapy on the expressions of cortisol, HSP70, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and pain scales in advanced cervical cancer patients. Health Care for Women International , 38( 2), 91–99.

- Yousefi, N. (2006). Comparing the effectiveness of two counseling approaches of gestalt therapy and logotherapy on decrease of depression symptoms, anxiety and aggression among women divorce applicants. Cross-Country Congress of Family Pathology , 10 (3), 658–663.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

I am a trauma survivor, I didn’t even realize, what I was dealing with for such a long time was PTSD, Disassociation, Depression, Grief and Anxiety. I found a lot of relief when I discovered that I have the power, in how I perceive my past. I listen more than I speak, unless someone wants to hear what I have to say. During COVID-19 I was deemed an essential worker, I am an Auto Technician, before and during COVID-19 I was Shop Manager, I had never felt such extreme pressure knowing that the safety of the people I work with was in my hands. I drove to work everyday with no other car in sight, until I got to work. The atmosphere was so tense, I felt where I cut into it, as I walked from my car to the building I work in, I could not understand other managers attitudes and why I questioned mine. Like a wise Philosopher once said in a moment of chaos, normal behavior seems abnormal. I encouraged everyone everyday, letting them know, this wasn’t the first time in history this has happened, just like the Philosopher King Marcus Aurelius. Everyday I had something humors to say. I am used to pressure, being I grew up around violence and witnessed a kid get shot and killed by drive a by. This wasn’t my first Rodeo. What was going on in the moment, did not phase me. I would find justification in my own way, why things happen. I continued until my back eventually gave out from so much stress. I felt guilt that I had never felt before, I kept giving happiness and hope until I lost my own, and gave into the excruciating pain that bulging disc in my lower back produce. This was the life changing moment in my life. COVID-19 in full bloom and running rampant, I did not turn to traditional medicine. Instead I found a Phycologist and Therapist that helped me get past my own internal struggles, as I have come together with myself and countless hours of reading, exercising, meditation, yoga, and Philosophy. I have come to this website. After reading your article, and understanding my own struggles, I am a firm believer Logotherapy can help so many people.

Dr. Melissa Madeson, Thank you for your well defined points about V Frankle and logotherapy. I once led a group of seniors at a convalescent center. We discussed the meaningful moments they recalled in their lives. I encouraged the participants to write their short and focused memoirs. These writings were subsequently published in a small volume. The writers and participants took part in a public reading, with family, friends, facility staff , and public in attendance. Overall, the lectures, writing, and readings were meaningful to all involved.

Finding meaning in trauma patients’ stories help them heal. Their traumas don’t define them, they’re just facts when their stories make sense. I am a trauma therapist and I love Viktor Frankl. This article actually helped me realize that how I work with trauma patients is actually how logotherapy help patients. Thank you.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Existential Crisis: How to Cope With Meaninglessness

Recent statistics suggest that over a quarter of UK nationals feel a deep sense of meaninglessness (Dinic, 2021). In the wake of multiple global economic, [...]

9 Powerful Existential Therapy Techniques for Your Sessions

While not easily defined, existential therapy builds on ideas taken from philosophy, helping clients to understand and clarify the life they would like to lead [...]

15 Values Worksheets to Enrich Clients’ Lives (+ Inventory)

It’s not always easy to align our actions with our values. And yet, by identifying and exploring what we find meaningful, we can learn to [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (48)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (27)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (17)

- Positive Parenting (2)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (47)

- Resilience & Coping (35)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (30)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Meaning Exercises Pack (PDF)

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Eur J Psychol

- v.17(3); 2021 Aug

Searching for Meaning in Chaos: Viktor Frankl’s Story

Hanan bushkin.

1 The Anxiety and Trauma Clinic, Johannesburg, South Africa

Roelf van Niekerk

2 Department of Industrial and Organisational Psychology, Nelson Mandela University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa

Louise Stroud

3 Department of Psychology, Nelson Mandela University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa

The existential psychiatrist Viktor Frankl (1905–1997) lived an extraordinary life. He witnessed and experienced acts of anti-Semitism, persecution, brutality, physical abuse, malnutrition, and emotional humiliation. Ironically, through these experiences, the loss of dignity and the loss of the lives of his wife, parents and brother, his philosophy of human nature, namely, that the search for meaning is the drive behind human behaviour, was moulded. Frankl formulated the basis of his existential approach to psychological practice before World War II (WWII). However, his experiences in the concentration camps confirmed his view that it is through a search for meaning and purpose in life that individuals can endure hardship and suffering. In a sense, Frank’s theory was tested in a dramatic way by the tragedies of his life. Following WWII, Frankl shaped modern psychological thinking by lecturing at more than 200 universities, authoring 40 books published in 50 languages and receiving 29 honorary doctorates. His ideas and experiences related to the search for meaning influenced theorists, practitioners, researchers, and lay people around the world. This study focuses specifically on the period between 1942 and 1945. The aim is to explore Frankl’s search for meaning within an unpredictable, life-threatening, and chaotic context through the lens of his concept of noö-dynamics.