How to Write the Perfect Essay

06 Feb, 2024 | Blog Articles , English Language Articles , Get the Edge , Humanities Articles , Writing Articles

You can keep adding to this plan, crossing bits out and linking the different bubbles when you spot connections between them. Even though you won’t have time to make a detailed plan under exam conditions, it can be helpful to draft a brief one, including a few key words, so that you don’t panic and go off topic when writing your essay.

If you don’t like the mind map format, there are plenty of others to choose from: you could make a table, a flowchart, or simply a list of bullet points.

Discover More

Thanks for signing up, step 2: have a clear structure.

Think about this while you’re planning: your essay is like an argument or a speech. It needs to have a logical structure, with all your points coming together to answer the question.

Start with the basics! It’s best to choose a few major points which will become your main paragraphs. Three main paragraphs is a good number for an exam essay, since you’ll be under time pressure.

If you agree with the question overall, it can be helpful to organise your points in the following pattern:

- YES (agreement with the question)

- AND (another YES point)

- BUT (disagreement or complication)

If you disagree with the question overall, try:

- AND (another BUT point)

For example, you could structure the Of Mice and Men sample question, “To what extent is Curley’s wife portrayed as a victim in Of Mice and Men ?”, as follows:

- YES (descriptions of her appearance)

- AND (other people’s attitudes towards her)

- BUT (her position as the only woman on the ranch gives her power as she uses her femininity to her advantage)

If you wanted to write a longer essay, you could include additional paragraphs under the YES/AND categories, perhaps discussing the ways in which Curley’s wife reveals her vulnerability and insecurities, and shares her dreams with the other characters. Alternatively, you could also lengthen your essay by including another BUT paragraph about her cruel and manipulative streak.

Of course, this is not necessarily the only right way to answer this essay question – as long as you back up your points with evidence from the text, you can take any standpoint that makes sense.

Step 3: Back up your points with well-analysed quotations

You wouldn’t write a scientific report without including evidence to support your findings, so why should it be any different with an essay? Even though you aren’t strictly required to substantiate every single point you make with a quotation, there’s no harm in trying.

A close reading of your quotations can enrich your appreciation of the question and will be sure to impress examiners. When selecting the best quotations to use in your essay, keep an eye out for specific literary techniques. For example, you could highlight Curley’s wife’s use of a rhetorical question when she says, a”n’ what am I doin’? Standin’ here talking to a bunch of bindle stiffs.” This might look like:

The rhetorical question “an’ what am I doin’?” signifies that Curley’s wife is very insecure; she seems to be questioning her own life choices. Moreover, she does not expect anyone to respond to her question, highlighting her loneliness and isolation on the ranch.

Other literary techniques to look out for include:

- Tricolon – a group of three words or phrases placed close together for emphasis

- Tautology – using different words that mean the same thing: e.g. “frightening” and “terrifying”

- Parallelism – ABAB structure, often signifying movement from one concept to another

- Chiasmus – ABBA structure, drawing attention to a phrase

- Polysyndeton – many conjunctions in a sentence

- Asyndeton – lack of conjunctions, which can speed up the pace of a sentence

- Polyptoton – using the same word in different forms for emphasis: e.g. “done” and “doing”

- Alliteration – repetition of the same sound, including assonance (similar vowel sounds), plosive alliteration (“b”, “d” and “p” sounds) and sibilance (“s” sounds)

- Anaphora – repetition of words, often used to emphasise a particular point

Don’t worry if you can’t locate all of these literary devices in the work you’re analysing. You can also discuss more obvious techniques, like metaphor, simile and onomatopoeia. It’s not a problem if you can’t remember all the long names; it’s far more important to be able to confidently explain the effects of each technique and highlight its relevance to the question.

Step 4: Be creative and original throughout

Anyone can write an essay using the tips above, but the thing that really makes it “perfect” is your own unique take on the topic. If you’ve noticed something intriguing or unusual in your reading, point it out – if you find it interesting, chances are the examiner will too!

Creative writing and essay writing are more closely linked than you might imagine. Keep the idea that you’re writing a speech or argument in mind, and you’re guaranteed to grab your reader’s attention.

It’s important to set out your line of argument in your introduction, introducing your main points and the general direction your essay will take, but don’t forget to keep something back for the conclusion, too. Yes, you need to summarise your main points, but if you’re just repeating the things you said in your introduction, the body of the essay is rendered pointless.

Think of your conclusion as the climax of your speech, the bit everything else has been leading up to, rather than the boring plenary at the end of the interesting stuff.

To return to Of Mice and Men once more, here’s an example of the ideal difference between an introduction and a conclusion:

Introduction

In John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men , Curley’s wife is portrayed as an ambiguous character. She could be viewed either as a cruel, seductive temptress or a lonely woman who is a victim of her society’s attitudes. Though she does seem to wield a form of sexual power, it is clear that Curley’s wife is largely a victim. This interpretation is supported by Steinbeck’s description of her appearance, other people’s attitudes, her dreams, and her evident loneliness and insecurity.

Overall, it is clear that Curley’s wife is a victim and is portrayed as such throughout the novel in the descriptions of her appearance, her dreams, other people’s judgemental attitudes, and her loneliness and insecurities. However, a character who was a victim and nothing else would be one-dimensional and Curley’s wife is not. Although she suffers in many ways, she is shown to assert herself through the manipulation of her femininity – a small rebellion against the victimisation she experiences.

Both refer back consistently to the question and summarise the essay’s main points. However, the conclusion adds something new which has been established in the main body of the essay and complicates the simple summary which is found in the introduction.

Hannah is an undergraduate English student at Somerville College, University of Oxford, and has a particular interest in postcolonial literature and the Gothic. She thinks literature is a crucial way of developing empathy and learning about the wider world. When she isn’t writing about 17th-century court masques, she enjoys acting, travelling and creative writing.

Recommended articles

A Day in the Life of an Oxford Scholastica Student: The First Monday

Hello, I’m Abaigeal or Abby for short, and I attended Oxford Scholastica’s residential summer school as a Discover Business student. During the Business course, I studied various topics across the large spectrum that is the world of business, including supply and...

Mastering Writing Competitions: Insider Tips from a Two-Time Winner

I’m Costas, a third-year History and Spanish student at the University of Oxford. During my time in secondary school and sixth form, I participated in various writing competitions, and I was able to win two of them (the national ISMLA Original Writing Competition and...

Beyond the Bar: 15 Must-Read Books for Future Lawyers

Reading within and around your subject, widely and in depth, is one of the most important things you can do to prepare yourself for a future in Law. So, we’ve put together a list of essential books to include on your reading list as a prospective or current Law...

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

A (Very) Simple Way to Improve Your Writing

- Mark Rennella

It’s called the “one-idea rule” — and any level of writer can use it.

The “one idea” rule is a simple concept that can help you sharpen your writing, persuade others by presenting your argument in a clear, concise, and engaging way. What exactly does the rule say?

- Every component of a successful piece of writing should express only one idea.

- In persuasive writing, your “one idea” is often the argument or belief you are presenting to the reader. Once you identify what that argument is, the “one-idea rule” can help you develop, revise, and connect the various components of your writing.

- For instance, let’s say you’re writing an essay. There are three components you will be working with throughout your piece: the title, the paragraphs, and the sentences.

- Each of these parts should be dedicated to just one idea. The ideas are not identical, of course, but they’re all related. If done correctly, the smaller ideas (in sentences) all build (in paragraphs) to support the main point (suggested in the title).

Where your work meets your life. See more from Ascend here .

Most advice about writing looks like a long laundry list of “do’s and don’ts.” These lists can be helpful from time to time, but they’re hard to remember … and, therefore, hard to depend on when you’re having trouble putting your thoughts to paper. During my time in academia, teaching composition at the undergraduate and graduate levels, I saw many people struggle with this.

- MR Mark Rennella is Associate Editor at HBP and has published two books, Entrepreneurs, Managers, and Leaders and The Boston Cosmopolitans .

Partner Center

- Tips for Reading an Assignment Prompt

- Asking Analytical Questions

- Introductions

- What Do Introductions Across the Disciplines Have in Common?

- Anatomy of a Body Paragraph

- Transitions

- Tips for Organizing Your Essay

- Counterargument

- Conclusions

- Strategies for Essay Writing: Downloadable PDFs

- Brief Guides to Writing in the Disciplines

Tips for Writing an Effective Application Essay

How to Write an Effective Essay

Writing an essay for college admission gives you a chance to use your authentic voice and show your personality. It's an excellent opportunity to personalize your application beyond your academic credentials, and a well-written essay can have a positive influence come decision time.

Want to know how to draft an essay for your college application ? Here are some tips to keep in mind when writing.

Tips for Essay Writing

A typical college application essay, also known as a personal statement, is 400-600 words. Although that may seem short, writing about yourself can be challenging. It's not something you want to rush or put off at the last moment. Think of it as a critical piece of the application process. Follow these tips to write an impactful essay that can work in your favor.

1. Start Early.

Few people write well under pressure. Try to complete your first draft a few weeks before you have to turn it in. Many advisers recommend starting as early as the summer before your senior year in high school. That way, you have ample time to think about the prompt and craft the best personal statement possible.

You don't have to work on your essay every day, but you'll want to give yourself time to revise and edit. You may discover that you want to change your topic or think of a better way to frame it. Either way, the sooner you start, the better.

2. Understand the Prompt and Instructions.

Before you begin the writing process, take time to understand what the college wants from you. The worst thing you can do is skim through the instructions and submit a piece that doesn't even fit the bare minimum requirements or address the essay topic. Look at the prompt, consider the required word count, and note any unique details each school wants.

3. Create a Strong Opener.

Students seeking help for their application essays often have trouble getting things started. It's a challenging writing process. Finding the right words to start can be the hardest part.

Spending more time working on your opener is always a good idea. The opening sentence sets the stage for the rest of your piece. The introductory paragraph is what piques the interest of the reader, and it can immediately set your essay apart from the others.

4. Stay on Topic.

One of the most important things to remember is to keep to the essay topic. If you're applying to 10 or more colleges, it's easy to veer off course with so many application essays.

A common mistake many students make is trying to fit previously written essays into the mold of another college's requirements. This seems like a time-saving way to avoid writing new pieces entirely, but it often backfires. The result is usually a final piece that's generic, unfocused, or confusing. Always write a new essay for every application, no matter how long it takes.

5. Think About Your Response.

Don't try to guess what the admissions officials want to read. Your essay will be easier to write─and more exciting to read─if you’re genuinely enthusiastic about your subject. Here’s an example: If all your friends are writing application essays about covid-19, it may be a good idea to avoid that topic, unless during the pandemic you had a vivid, life-changing experience you're burning to share. Whatever topic you choose, avoid canned responses. Be creative.

6. Focus on You.

Essay prompts typically give you plenty of latitude, but panel members expect you to focus on a subject that is personal (although not overly intimate) and particular to you. Admissions counselors say the best essays help them learn something about the candidate that they would never know from reading the rest of the application.

7. Stay True to Your Voice.

Use your usual vocabulary. Avoid fancy language you wouldn't use in real life. Imagine yourself reading this essay aloud to a classroom full of people who have never met you. Keep a confident tone. Be wary of words and phrases that undercut that tone.

8. Be Specific and Factual.

Capitalize on real-life experiences. Your essay may give you the time and space to explain why a particular achievement meant so much to you. But resist the urge to exaggerate and embellish. Admissions counselors read thousands of essays each year. They can easily spot a fake.

9. Edit and Proofread.

When you finish the final draft, run it through the spell checker on your computer. Then don’t read your essay for a few days. You'll be more apt to spot typos and awkward grammar when you reread it. After that, ask a teacher, parent, or college student (preferably an English or communications major) to give it a quick read. While you're at it, double-check your word count.

Writing essays for college admission can be daunting, but it doesn't have to be. A well-crafted essay could be the deciding factor─in your favor. Keep these tips in mind, and you'll have no problem creating memorable pieces for every application.

What is the format of a college application essay?

Generally, essays for college admission follow a simple format that includes an opening paragraph, a lengthier body section, and a closing paragraph. You don't need to include a title, which will only take up extra space. Keep in mind that the exact format can vary from one college application to the next. Read the instructions and prompt for more guidance.

Most online applications will include a text box for your essay. If you're attaching it as a document, however, be sure to use a standard, 12-point font and use 1.5-spaced or double-spaced lines, unless the application specifies different font and spacing.

How do you start an essay?

The goal here is to use an attention grabber. Think of it as a way to reel the reader in and interest an admissions officer in what you have to say. There's no trick on how to start a college application essay. The best way you can approach this task is to flex your creative muscles and think outside the box.

You can start with openers such as relevant quotes, exciting anecdotes, or questions. Either way, the first sentence should be unique and intrigue the reader.

What should an essay include?

Every application essay you write should include details about yourself and past experiences. It's another opportunity to make yourself look like a fantastic applicant. Leverage your experiences. Tell a riveting story that fulfills the prompt.

What shouldn’t be included in an essay?

When writing a college application essay, it's usually best to avoid overly personal details and controversial topics. Although these topics might make for an intriguing essay, they can be tricky to express well. If you’re unsure if a topic is appropriate for your essay, check with your school counselor. An essay for college admission shouldn't include a list of achievements or academic accolades either. Your essay isn’t meant to be a rehashing of information the admissions panel can find elsewhere in your application.

How can you make your essay personal and interesting?

The best way to make your essay interesting is to write about something genuinely important to you. That could be an experience that changed your life or a valuable lesson that had an enormous impact on you. Whatever the case, speak from the heart, and be honest.

Is it OK to discuss mental health in an essay?

Mental health struggles can create challenges you must overcome during your education and could be an opportunity for you to show how you’ve handled challenges and overcome obstacles. If you’re considering writing your essay for college admission on this topic, consider talking to your school counselor or with an English teacher on how to frame the essay.

Related Articles

Essay Papers Writing Online

Tips and tricks for crafting engaging and effective essays.

Writing essays can be a challenging task, but with the right approach and strategies, you can create compelling and impactful pieces that captivate your audience. Whether you’re a student working on an academic paper or a professional honing your writing skills, these tips will help you craft essays that stand out.

Effective essays are not just about conveying information; they are about persuading, engaging, and inspiring readers. To achieve this, it’s essential to pay attention to various elements of the essay-writing process, from brainstorming ideas to polishing your final draft. By following these tips, you can elevate your writing and produce essays that leave a lasting impression.

Understanding the Essay Prompt

Before you start writing your essay, it is crucial to thoroughly understand the essay prompt or question provided by your instructor. The essay prompt serves as a roadmap for your essay and outlines the specific requirements or expectations.

Here are a few key things to consider when analyzing the essay prompt:

- Read the prompt carefully and identify the main topic or question being asked.

- Pay attention to any specific instructions or guidelines provided, such as word count, formatting requirements, or sources to be used.

- Identify key terms or phrases in the prompt that can help you determine the focus of your essay.

By understanding the essay prompt thoroughly, you can ensure that your essay addresses the topic effectively and meets the requirements set forth by your instructor.

Researching Your Topic Thoroughly

One of the key elements of writing an effective essay is conducting thorough research on your chosen topic. Research helps you gather the necessary information, facts, and examples to support your arguments and make your essay more convincing.

Here are some tips for researching your topic thoroughly:

By following these tips and conducting thorough research on your topic, you will be able to write a well-informed and persuasive essay that effectively communicates your ideas and arguments.

Creating a Strong Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is a crucial element of any well-crafted essay. It serves as the main point or idea that you will be discussing and supporting throughout your paper. A strong thesis statement should be clear, specific, and arguable.

To create a strong thesis statement, follow these tips:

- Be specific: Your thesis statement should clearly state the main idea of your essay. Avoid vague or general statements.

- Be concise: Keep your thesis statement concise and to the point. Avoid unnecessary details or lengthy explanations.

- Be argumentative: Your thesis statement should present an argument or perspective that can be debated or discussed in your essay.

- Be relevant: Make sure your thesis statement is relevant to the topic of your essay and reflects the main point you want to make.

- Revise as needed: Don’t be afraid to revise your thesis statement as you work on your essay. It may change as you develop your ideas.

Remember, a strong thesis statement sets the tone for your entire essay and provides a roadmap for your readers to follow. Put time and effort into crafting a clear and compelling thesis statement to ensure your essay is effective and persuasive.

Developing a Clear Essay Structure

One of the key elements of writing an effective essay is developing a clear and logical structure. A well-structured essay helps the reader follow your argument and enhances the overall readability of your work. Here are some tips to help you develop a clear essay structure:

1. Start with a strong introduction: Begin your essay with an engaging introduction that introduces the topic and clearly states your thesis or main argument.

2. Organize your ideas: Before you start writing, outline the main points you want to cover in your essay. This will help you organize your thoughts and ensure a logical flow of ideas.

3. Use topic sentences: Begin each paragraph with a topic sentence that introduces the main idea of the paragraph. This helps the reader understand the purpose of each paragraph.

4. Provide evidence and analysis: Support your arguments with evidence and analysis to back up your main points. Make sure your evidence is relevant and directly supports your thesis.

5. Transition between paragraphs: Use transitional words and phrases to create flow between paragraphs and help the reader move smoothly from one idea to the next.

6. Conclude effectively: End your essay with a strong conclusion that summarizes your main points and reinforces your thesis. Avoid introducing new ideas in the conclusion.

By following these tips, you can develop a clear essay structure that will help you effectively communicate your ideas and engage your reader from start to finish.

Using Relevant Examples and Evidence

When writing an essay, it’s crucial to support your arguments and assertions with relevant examples and evidence. This not only adds credibility to your writing but also helps your readers better understand your points. Here are some tips on how to effectively use examples and evidence in your essays:

- Choose examples that are specific and relevant to the topic you’re discussing. Avoid using generic examples that may not directly support your argument.

- Provide concrete evidence to back up your claims. This could include statistics, research findings, or quotes from reliable sources.

- Interpret the examples and evidence you provide, explaining how they support your thesis or main argument. Don’t assume that the connection is obvious to your readers.

- Use a variety of examples to make your points more persuasive. Mixing personal anecdotes with scholarly evidence can make your essay more engaging and convincing.

- Cite your sources properly to give credit to the original authors and avoid plagiarism. Follow the citation style required by your instructor or the publication you’re submitting to.

By integrating relevant examples and evidence into your essays, you can craft a more convincing and well-rounded piece of writing that resonates with your audience.

Editing and Proofreading Your Essay Carefully

Once you have finished writing your essay, the next crucial step is to edit and proofread it carefully. Editing and proofreading are essential parts of the writing process that help ensure your essay is polished and error-free. Here are some tips to help you effectively edit and proofread your essay:

1. Take a Break: Before you start editing, take a short break from your essay. This will help you approach the editing process with a fresh perspective.

2. Read Aloud: Reading your essay aloud can help you catch any awkward phrasing or grammatical errors that you may have missed while writing. It also helps you check the flow of your essay.

3. Check for Consistency: Make sure that your essay has a consistent style, tone, and voice throughout. Check for inconsistencies in formatting, punctuation, and language usage.

4. Remove Unnecessary Words: Look for any unnecessary words or phrases in your essay and remove them to make your writing more concise and clear.

5. Proofread for Errors: Carefully proofread your essay for spelling, grammar, and punctuation errors. Pay attention to commonly misused words and homophones.

6. Get Feedback: It’s always a good idea to get feedback from someone else. Ask a friend, classmate, or teacher to review your essay and provide constructive feedback.

By following these tips and taking the time to edit and proofread your essay carefully, you can improve the overall quality of your writing and make sure your ideas are effectively communicated to your readers.

Related Post

How to master the art of writing expository essays and captivate your audience, convenient and reliable source to purchase college essays online, step-by-step guide to crafting a powerful literary analysis essay, tips and techniques for crafting compelling narrative essays.

- Academic Skills

- Reading, writing and referencing

Writing a great essay

This resource covers key considerations when writing an essay.

While reading a student’s essay, markers will ask themselves questions such as:

- Does this essay directly address the set task?

- Does it present a strong, supported position?

- Does it use relevant sources appropriately?

- Is the expression clear, and the style appropriate?

- Is the essay organised coherently? Is there a clear introduction, body and conclusion?

You can use these questions to reflect on your own writing. Here are six top tips to help you address these criteria.

1. Analyse the question

Student essays are responses to specific questions. As an essay must address the question directly, your first step should be to analyse the question. Make sure you know exactly what is being asked of you.

Generally, essay questions contain three component parts:

- Content terms: Key concepts that are specific to the task

- Limiting terms: The scope that the topic focuses on

- Directive terms: What you need to do in relation to the content, e.g. discuss, analyse, define, compare, evaluate.

Look at the following essay question:

Discuss the importance of light in Gothic architecture.

- Content terms: Gothic architecture

- Limiting terms: the importance of light. If you discussed some other feature of Gothic architecture, for example spires or arches, you would be deviating from what is required. This essay question is limited to a discussion of light. Likewise, it asks you to write about the importance of light – not, for example, to discuss how light enters Gothic churches.

- Directive term: discuss. This term asks you to take a broad approach to the variety of ways in which light may be important for Gothic architecture. You should introduce and consider different ideas and opinions that you have met in academic literature on this topic, citing them appropriately .

For a more complex question, you can highlight the key words and break it down into a series of sub-questions to make sure you answer all parts of the task. Consider the following question (from Arts):

To what extent can the American Revolution be understood as a revolution ‘from below’? Why did working people become involved and with what aims in mind?

The key words here are American Revolution and revolution ‘from below’. This is a view that you would need to respond to in this essay. This response must focus on the aims and motivations of working people in the revolution, as stated in the second question.

2. Define your argument

As you plan and prepare to write the essay, you must consider what your argument is going to be. This means taking an informed position or point of view on the topic presented in the question, then defining and presenting a specific argument.

Consider these two argument statements:

The architectural use of light in Gothic cathedrals physically embodied the significance of light in medieval theology.

In the Gothic cathedral of Cologne, light served to accentuate the authority and ritual centrality of the priest.

Statements like these define an essay’s argument. They give coherence by providing an overarching theme and position towards which the entire essay is directed.

3. Use evidence, reasoning and scholarship

To convince your audience of your argument, you must use evidence and reasoning, which involves referring to and evaluating relevant scholarship.

- Evidence provides concrete information to support your claim. It typically consists of specific examples, facts, quotations, statistics and illustrations.

- Reasoning connects the evidence to your argument. Rather than citing evidence like a shopping list, you need to evaluate the evidence and show how it supports your argument.

- Scholarship is used to show how your argument relates to what has been written on the topic (citing specific works). Scholarship can be used as part of your evidence and reasoning to support your argument.

4. Organise a coherent essay

An essay has three basic components - introduction, body and conclusion.

The purpose of an introduction is to introduce your essay. It typically presents information in the following order:

- A general statement about the topic that provides context for your argument

- A thesis statement showing your argument. You can use explicit lead-ins, such as ‘This essay argues that...’

- A ‘road map’ of the essay, telling the reader how it is going to present and develop your argument.

Example introduction

"To what extent can the American Revolution be understood as a revolution ‘from below’? Why did working people become involved and with what aims in mind?"

Introduction*

Historians generally concentrate on the twenty-year period between 1763 and 1783 as the period which constitutes the American Revolution [This sentence sets the general context of the period] . However, when considering the involvement of working people, or people from below, in the revolution it is important to make a distinction between the pre-revolutionary period 1763-1774 and the revolutionary period 1774-1788, marked by the establishment of the continental Congress(1) [This sentence defines the key term from below and gives more context to the argument that follows] . This paper will argue that the nature and aims of the actions of working people are difficult to assess as it changed according to each phase [This is the thesis statement] . The pre-revolutionary period was characterised by opposition to Britain’s authority. During this period the aims and actions of the working people were more conservative as they responded to grievances related to taxes and scarce land, issues which directly affected them. However, examination of activities such as the organisation of crowd action and town meetings, pamphlet writing, formal communications to Britain of American grievances and physical action in the streets, demonstrates that their aims and actions became more revolutionary after 1775 [These sentences give the ‘road map’ or overview of the content of the essay] .

The body of the essay develops and elaborates your argument. It does this by presenting a reasoned case supported by evidence from relevant scholarship. Its shape corresponds to the overview that you provided in your introduction.

The body of your essay should be written in paragraphs. Each body paragraph should develop one main idea that supports your argument. To learn how to structure a paragraph, look at the page developing clarity and focus in academic writing .

Your conclusion should not offer any new material. Your evidence and argumentation should have been made clear to the reader in the body of the essay.

Use the conclusion to briefly restate the main argumentative position and provide a short summary of the themes discussed. In addition, also consider telling your reader:

- What the significance of your findings, or the implications of your conclusion, might be

- Whether there are other factors which need to be looked at, but which were outside the scope of the essay

- How your topic links to the wider context (‘bigger picture’) in your discipline.

Do not simply repeat yourself in this section. A conclusion which merely summarises is repetitive and reduces the impact of your paper.

Example conclusion

Conclusion*.

Although, to a large extent, the working class were mainly those in the forefront of crowd action and they also led the revolts against wealthy plantation farmers, the American Revolution was not a class struggle [This is a statement of the concluding position of the essay]. Working people participated because the issues directly affected them – the threat posed by powerful landowners and the tyranny Britain represented. Whereas the aims and actions of the working classes were more concerned with resistance to British rule during the pre-revolutionary period, they became more revolutionary in nature after 1775 when the tension with Britain escalated [These sentences restate the key argument]. With this shift, a change in ideas occurred. In terms of considering the Revolution as a whole range of activities such as organising riots, communicating to Britain, attendance at town hall meetings and pamphlet writing, a difficulty emerges in that all classes were involved. Therefore, it is impossible to assess the extent to which a single group such as working people contributed to the American Revolution [These sentences give final thoughts on the topic].

5. Write clearly

An essay that makes good, evidence-supported points will only receive a high grade if it is written clearly. Clarity is produced through careful revision and editing, which can turn a good essay into an excellent one.

When you edit your essay, try to view it with fresh eyes – almost as if someone else had written it.

Ask yourself the following questions:

Overall structure

- Have you clearly stated your argument in your introduction?

- Does the actual structure correspond to the ‘road map’ set out in your introduction?

- Have you clearly indicated how your main points support your argument?

- Have you clearly signposted the transitions between each of your main points for your reader?

- Does each paragraph introduce one main idea?

- Does every sentence in the paragraph support that main idea?

- Does each paragraph display relevant evidence and reasoning?

- Does each paragraph logically follow on from the one before it?

- Is each sentence grammatically complete?

- Is the spelling correct?

- Is the link between sentences clear to your readers?

- Have you avoided redundancy and repetition?

See more about editing on our editing your writing page.

6. Cite sources and evidence

Finally, check your citations to make sure that they are accurate and complete. Some faculties require you to use a specific citation style (e.g. APA) while others may allow you to choose a preferred one. Whatever style you use, you must follow its guidelines correctly and consistently. You can use Recite, the University of Melbourne style guide, to check your citations.

Further resources

- Germov, J. (2011). Get great marks for your essays, reports and presentations (3rd ed.). NSW: Allen and Unwin.

- Using English for Academic Purposes: A guide for students in Higher Education [online]. Retrieved January 2020 from http://www.uefap.com

- Williams, J.M. & Colomb, G. G. (2010) Style: Lessons in clarity and grace. 10th ed. New York: Longman.

* Example introduction and conclusion adapted from a student paper.

Looking for one-on-one advice?

Get tailored advice from an Academic Skills Adviser by booking an Individual appointment, or get quick feedback from one of our Academic Writing Mentors via email through our Writing advice service.

Go to Student appointments

Tips for Online Students , Tips for Students

How To Write An Essay: Beginner Tips And Tricks

Updated: July 11, 2022

Published: June 22, 2021

Many students dread writing essays, but essay writing is an important skill to develop in high school, university, and even into your future career. By learning how to write an essay properly, the process can become more enjoyable and you’ll find you’re better able to organize and articulate your thoughts.

When writing an essay, it’s common to follow a specific pattern, no matter what the topic is. Once you’ve used the pattern a few times and you know how to structure an essay, it will become a lot more simple to apply your knowledge to every essay.

No matter which major you choose, you should know how to craft a good essay. Here, we’ll cover the basics of essay writing, along with some helpful tips to make the writing process go smoothly.

Photo by Laura Chouette on Unsplash

Types of Essays

Think of an essay as a discussion. There are many types of discussions you can have with someone else. You can be describing a story that happened to you, you might explain to them how to do something, or you might even argue about a certain topic.

When it comes to different types of essays, it follows a similar pattern. Like a friendly discussion, each type of essay will come with its own set of expectations or goals.

For example, when arguing with a friend, your goal is to convince them that you’re right. The same goes for an argumentative essay.

Here are a few of the main essay types you can expect to come across during your time in school:

Narrative Essay

This type of essay is almost like telling a story, not in the traditional sense with dialogue and characters, but as if you’re writing out an event or series of events to relay information to the reader.

Persuasive Essay

Here, your goal is to persuade the reader about your views on a specific topic.

Descriptive Essay

This is the kind of essay where you go into a lot more specific details describing a topic such as a place or an event.

Argumentative Essay

In this essay, you’re choosing a stance on a topic, usually controversial, and your goal is to present evidence that proves your point is correct.

Expository Essay

Your purpose with this type of essay is to tell the reader how to complete a specific process, often including a step-by-step guide or something similar.

Compare and Contrast Essay

You might have done this in school with two different books or characters, but the ultimate goal is to draw similarities and differences between any two given subjects.

The Main Stages of Essay Writing

When it comes to writing an essay, many students think the only stage is getting all your ideas down on paper and submitting your work. However, that’s not quite the case.

There are three main stages of writing an essay, each one with its own purpose. Of course, writing the essay itself is the most substantial part, but the other two stages are equally as important.

So, what are these three stages of essay writing? They are:

Preparation

Before you even write one word, it’s important to prepare the content and structure of your essay. If a topic wasn’t assigned to you, then the first thing you should do is settle on a topic. Next, you want to conduct your research on that topic and create a detailed outline based on your research. The preparation stage will make writing your essay that much easier since, with your outline and research, you should already have the skeleton of your essay.

Writing is the most time-consuming stage. In this stage, you will write out all your thoughts and ideas and craft your essay based on your outline. You’ll work on developing your ideas and fleshing them out throughout the introduction, body, and conclusion (more on these soon).

In the final stage, you’ll go over your essay and check for a few things. First, you’ll check if your essay is cohesive, if all the points make sense and are related to your topic, and that your facts are cited and backed up. You can also check for typos, grammar and punctuation mistakes, and formatting errors.

The Five-Paragraph Essay

We mentioned earlier that essay writing follows a specific structure, and for the most part in academic or college essays , the five-paragraph essay is the generally accepted structure you’ll be expected to use.

The five-paragraph essay is broken down into one introduction paragraph, three body paragraphs, and a closing paragraph. However, that doesn’t always mean that an essay is written strictly in five paragraphs, but rather that this structure can be used loosely and the three body paragraphs might become three sections instead.

Let’s take a closer look at each section and what it entails.

Introduction

As the name implies, the purpose of your introduction paragraph is to introduce your idea. A good introduction begins with a “hook,” something that grabs your reader’s attention and makes them excited to read more.

Another key tenant of an introduction is a thesis statement, which usually comes towards the end of the introduction itself. Your thesis statement should be a phrase that explains your argument, position, or central idea that you plan on developing throughout the essay.

You can also include a short outline of what to expect in your introduction, including bringing up brief points that you plan on explaining more later on in the body paragraphs.

Here is where most of your essay happens. The body paragraphs are where you develop your ideas and bring up all the points related to your main topic.

In general, you’re meant to have three body paragraphs, or sections, and each one should bring up a different point. Think of it as bringing up evidence. Each paragraph is a different piece of evidence, and when the three pieces are taken together, it backs up your main point — your thesis statement — really well.

That being said, you still want each body paragraph to be tied together in some way so that the essay flows. The points should be distinct enough, but they should relate to each other, and definitely to your thesis statement. Each body paragraph works to advance your point, so when crafting your essay, it’s important to keep this in mind so that you avoid going off-track or writing things that are off-topic.

Many students aren’t sure how to write a conclusion for an essay and tend to see their conclusion as an afterthought, but this section is just as important as the rest of your work.

You shouldn’t be presenting any new ideas in your conclusion, but you should summarize your main points and show how they back up your thesis statement.

Essentially, the conclusion is similar in structure and content to the introduction, but instead of introducing your essay, it should be wrapping up the main thoughts and presenting them to the reader as a singular closed argument.

Photo by AMIT RANJAN on Unsplash

Steps to Writing an Essay

Now that you have a better idea of an essay’s structure and all the elements that go into it, you might be wondering what the different steps are to actually write your essay.

Don’t worry, we’ve got you covered. Instead of going in blind, follow these steps on how to write your essay from start to finish.

Understand Your Assignment

When writing an essay for an assignment, the first critical step is to make sure you’ve read through your assignment carefully and understand it thoroughly. You want to check what type of essay is required, that you understand the topic, and that you pay attention to any formatting or structural requirements. You don’t want to lose marks just because you didn’t read the assignment carefully.

Research Your Topic

Once you understand your assignment, it’s time to do some research. In this step, you should start looking at different sources to get ideas for what points you want to bring up throughout your essay.

Search online or head to the library and get as many resources as possible. You don’t need to use them all, but it’s good to start with a lot and then narrow down your sources as you become more certain of your essay’s direction.

Start Brainstorming

After research comes the brainstorming. There are a lot of different ways to start the brainstorming process . Here are a few you might find helpful:

- Think about what you found during your research that interested you the most

- Jot down all your ideas, even if they’re not yet fully formed

- Create word clouds or maps for similar terms or ideas that come up so you can group them together based on their similarities

- Try freewriting to get all your ideas out before arranging them

Create a Thesis

This is often the most tricky part of the whole process since you want to create a thesis that’s strong and that you’re about to develop throughout the entire essay. Therefore, you want to choose a thesis statement that’s broad enough that you’ll have enough to say about it, but not so broad that you can’t be precise.

Write Your Outline

Armed with your research, brainstorming sessions, and your thesis statement, the next step is to write an outline.

In the outline, you’ll want to put your thesis statement at the beginning and start creating the basic skeleton of how you want your essay to look.

A good way to tackle an essay is to use topic sentences . A topic sentence is like a mini-thesis statement that is usually the first sentence of a new paragraph. This sentence introduces the main idea that will be detailed throughout the paragraph.

If you create an outline with the topic sentences for your body paragraphs and then a few points of what you want to discuss, you’ll already have a strong starting point when it comes time to sit down and write. This brings us to our next step…

Write a First Draft

The first time you write your entire essay doesn’t need to be perfect, but you do need to get everything on the page so that you’re able to then write a second draft or review it afterward.

Everyone’s writing process is different. Some students like to write their essay in the standard order of intro, body, and conclusion, while others prefer to start with the “meat” of the essay and tackle the body, and then fill in the other sections afterward.

Make sure your essay follows your outline and that everything relates to your thesis statement and your points are backed up by the research you did.

Revise, Edit, and Proofread

The revision process is one of the three main stages of writing an essay, yet many people skip this step thinking their work is done after the first draft is complete.

However, proofreading, reviewing, and making edits on your essay can spell the difference between a B paper and an A.

After writing the first draft, try and set your essay aside for a few hours or even a day or two, and then come back to it with fresh eyes to review it. You might find mistakes or inconsistencies you missed or better ways to formulate your arguments.

Add the Finishing Touches

Finally, you’ll want to make sure everything that’s required is in your essay. Review your assignment again and see if all the requirements are there, such as formatting rules, citations, quotes, etc.

Go over the order of your paragraphs and make sure everything makes sense, flows well, and uses the same writing style .

Once everything is checked and all the last touches are added, give your essay a final read through just to ensure it’s as you want it before handing it in.

A good way to do this is to read your essay out loud since you’ll be able to hear if there are any mistakes or inaccuracies.

Essay Writing Tips

With the steps outlined above, you should be able to craft a great essay. Still, there are some other handy tips we’d recommend just to ensure that the essay writing process goes as smoothly as possible.

- Start your essay early. This is the first tip for a reason. It’s one of the most important things you can do to write a good essay. If you start it the night before, then you won’t have enough time to research, brainstorm, and outline — and you surely won’t have enough time to review.

- Don’t try and write it in one sitting. It’s ok if you need to take breaks or write it over a few days. It’s better to write it in multiple sittings so that you have a fresh mind each time and you’re able to focus.

- Always keep the essay question in mind. If you’re given an assigned question, then you should always keep it handy when writing your essay to make sure you’re always working to answer the question.

- Use transitions between paragraphs. In order to improve the readability of your essay, try and make clear transitions between paragraphs. This means trying to relate the end of one paragraph to the beginning of the next one so the shift doesn’t seem random.

- Integrate your research thoughtfully. Add in citations or quotes from your research materials to back up your thesis and main points. This will show that you did the research and that your thesis is backed up by it.

Wrapping Up

Writing an essay doesn’t need to be daunting if you know how to approach it. Using our essay writing steps and tips, you’ll have better knowledge on how to write an essay and you’ll be able to apply it to your next assignment. Once you do this a few times, it will become more natural to you and the essay writing process will become quicker and easier.

If you still need assistance with your essay, check with a student advisor to see if they offer help with writing. At University of the People(UoPeople), we always want our students to succeed, so our student advisors are ready to help with writing skills when necessary.

Related Articles

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write an essay introduction | 4 steps & examples

How to Write an Essay Introduction | 4 Steps & Examples

Published on February 4, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 23, 2023.

A good introduction paragraph is an essential part of any academic essay . It sets up your argument and tells the reader what to expect.

The main goals of an introduction are to:

- Catch your reader’s attention.

- Give background on your topic.

- Present your thesis statement —the central point of your essay.

This introduction example is taken from our interactive essay example on the history of Braille.

The invention of Braille was a major turning point in the history of disability. The writing system of raised dots used by visually impaired people was developed by Louis Braille in nineteenth-century France. In a society that did not value disabled people in general, blindness was particularly stigmatized, and lack of access to reading and writing was a significant barrier to social participation. The idea of tactile reading was not entirely new, but existing methods based on sighted systems were difficult to learn and use. As the first writing system designed for blind people’s needs, Braille was a groundbreaking new accessibility tool. It not only provided practical benefits, but also helped change the cultural status of blindness. This essay begins by discussing the situation of blind people in nineteenth-century Europe. It then describes the invention of Braille and the gradual process of its acceptance within blind education. Subsequently, it explores the wide-ranging effects of this invention on blind people’s social and cultural lives.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: hook your reader, step 2: give background information, step 3: present your thesis statement, step 4: map your essay’s structure, step 5: check and revise, more examples of essay introductions, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about the essay introduction.

Your first sentence sets the tone for the whole essay, so spend some time on writing an effective hook.

Avoid long, dense sentences—start with something clear, concise and catchy that will spark your reader’s curiosity.

The hook should lead the reader into your essay, giving a sense of the topic you’re writing about and why it’s interesting. Avoid overly broad claims or plain statements of fact.

Examples: Writing a good hook

Take a look at these examples of weak hooks and learn how to improve them.

- Braille was an extremely important invention.

- The invention of Braille was a major turning point in the history of disability.

The first sentence is a dry fact; the second sentence is more interesting, making a bold claim about exactly why the topic is important.

- The internet is defined as “a global computer network providing a variety of information and communication facilities.”

- The spread of the internet has had a world-changing effect, not least on the world of education.

Avoid using a dictionary definition as your hook, especially if it’s an obvious term that everyone knows. The improved example here is still broad, but it gives us a much clearer sense of what the essay will be about.

- Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is a famous book from the nineteenth century.

- Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is often read as a crude cautionary tale about the dangers of scientific advancement.

Instead of just stating a fact that the reader already knows, the improved hook here tells us about the mainstream interpretation of the book, implying that this essay will offer a different interpretation.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Next, give your reader the context they need to understand your topic and argument. Depending on the subject of your essay, this might include:

- Historical, geographical, or social context

- An outline of the debate you’re addressing

- A summary of relevant theories or research about the topic

- Definitions of key terms

The information here should be broad but clearly focused and relevant to your argument. Don’t give too much detail—you can mention points that you will return to later, but save your evidence and interpretation for the main body of the essay.

How much space you need for background depends on your topic and the scope of your essay. In our Braille example, we take a few sentences to introduce the topic and sketch the social context that the essay will address:

Now it’s time to narrow your focus and show exactly what you want to say about the topic. This is your thesis statement —a sentence or two that sums up your overall argument.

This is the most important part of your introduction. A good thesis isn’t just a statement of fact, but a claim that requires evidence and explanation.

The goal is to clearly convey your own position in a debate or your central point about a topic.

Particularly in longer essays, it’s helpful to end the introduction by signposting what will be covered in each part. Keep it concise and give your reader a clear sense of the direction your argument will take.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

As you research and write, your argument might change focus or direction as you learn more.

For this reason, it’s often a good idea to wait until later in the writing process before you write the introduction paragraph—it can even be the very last thing you write.

When you’ve finished writing the essay body and conclusion , you should return to the introduction and check that it matches the content of the essay.

It’s especially important to make sure your thesis statement accurately represents what you do in the essay. If your argument has gone in a different direction than planned, tweak your thesis statement to match what you actually say.

To polish your writing, you can use something like a paraphrasing tool .

You can use the checklist below to make sure your introduction does everything it’s supposed to.

Checklist: Essay introduction

My first sentence is engaging and relevant.

I have introduced the topic with necessary background information.

I have defined any important terms.

My thesis statement clearly presents my main point or argument.

Everything in the introduction is relevant to the main body of the essay.

You have a strong introduction - now make sure the rest of your essay is just as good.

- Argumentative

- Literary analysis

This introduction to an argumentative essay sets up the debate about the internet and education, and then clearly states the position the essay will argue for.

The spread of the internet has had a world-changing effect, not least on the world of education. The use of the internet in academic contexts is on the rise, and its role in learning is hotly debated. For many teachers who did not grow up with this technology, its effects seem alarming and potentially harmful. This concern, while understandable, is misguided. The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its critical benefits for students and educators—as a uniquely comprehensive and accessible information source; a means of exposure to and engagement with different perspectives; and a highly flexible learning environment.

This introduction to a short expository essay leads into the topic (the invention of the printing press) and states the main point the essay will explain (the effect of this invention on European society).

In many ways, the invention of the printing press marked the end of the Middle Ages. The medieval period in Europe is often remembered as a time of intellectual and political stagnation. Prior to the Renaissance, the average person had very limited access to books and was unlikely to be literate. The invention of the printing press in the 15th century allowed for much less restricted circulation of information in Europe, paving the way for the Reformation.

This introduction to a literary analysis essay , about Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein , starts by describing a simplistic popular view of the story, and then states how the author will give a more complex analysis of the text’s literary devices.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is often read as a crude cautionary tale. Arguably the first science fiction novel, its plot can be read as a warning about the dangers of scientific advancement unrestrained by ethical considerations. In this reading, and in popular culture representations of the character as a “mad scientist”, Victor Frankenstein represents the callous, arrogant ambition of modern science. However, far from providing a stable image of the character, Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to gradually transform our impression of Frankenstein, portraying him in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Your essay introduction should include three main things, in this order:

- An opening hook to catch the reader’s attention.

- Relevant background information that the reader needs to know.

- A thesis statement that presents your main point or argument.

The length of each part depends on the length and complexity of your essay .

The “hook” is the first sentence of your essay introduction . It should lead the reader into your essay, giving a sense of why it’s interesting.

To write a good hook, avoid overly broad statements or long, dense sentences. Try to start with something clear, concise and catchy that will spark your reader’s curiosity.

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . Everything else you write should relate to this key idea.

The thesis statement is essential in any academic essay or research paper for two main reasons:

- It gives your writing direction and focus.

- It gives the reader a concise summary of your main point.

Without a clear thesis statement, an essay can end up rambling and unfocused, leaving your reader unsure of exactly what you want to say.

The structure of an essay is divided into an introduction that presents your topic and thesis statement , a body containing your in-depth analysis and arguments, and a conclusion wrapping up your ideas.

The structure of the body is flexible, but you should always spend some time thinking about how you can organize your essay to best serve your ideas.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, July 23). How to Write an Essay Introduction | 4 Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 11, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/introduction/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, how to conclude an essay | interactive example, what is your plagiarism score.

Money-Saving Services for Writing College Essays Online

Writing argumentative essay like an expert.

Having big plans for the future? Willing to enter the best college that will develop your skills and talents? Unfortunately, thousands of other students think the same. Writing college essay is the first step to understanding that your career will be bright!

On the basis of your work, admission committee will decide whether you’re worthy to be enrolled in the college. Just imagine how many application they receive annually. Some of them are brilliant, others are commonplace and naive. But your task here is not to turn writing a persuasive essay into a nightmare by thinking about it.

What should you start with? The first step to write college essay is think about the main idea you want to describe. There should be something important, impressing, heartwarming in your work. And, of course, it should be truthful and original as well. Even if you know how to write an argument essay, there’s also a necessity to follow the right structure and composition. And here, you might need help of professionals.

Special services that help students in writing college essays exist all over the world. You can see it for yourself. Type “write my essay” and scroll through the results – the amount of websites will surprise you. Be careful when choosing a cheap service: you might end getting your paper done by a non-native English speaker. Do you actually want to waste your money on that? Make a little research before you start writing an argument essay, read the examples you find on the Internet, make notes and try to write down all the thoughts you have during the day (not when you actually seat in front your PC).

In attempt to write a college essay, people are spending countless night drinking one cup of coffee after another and rotating thousands thoughts in their heads. However, it might not be enough. People who write a persuasive essay also seeking help on the side. There’s no shame in that.

Quality guarantee

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 12 April 2024

Feedback sources in essay writing: peer-generated or AI-generated feedback?

- Seyyed Kazem Banihashem 1 , 2 ,

- Nafiseh Taghizadeh Kerman 3 ,

- Omid Noroozi 2 ,

- Jewoong Moon 4 &

- Hendrik Drachsler 1 , 5

International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education volume 21 , Article number: 23 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

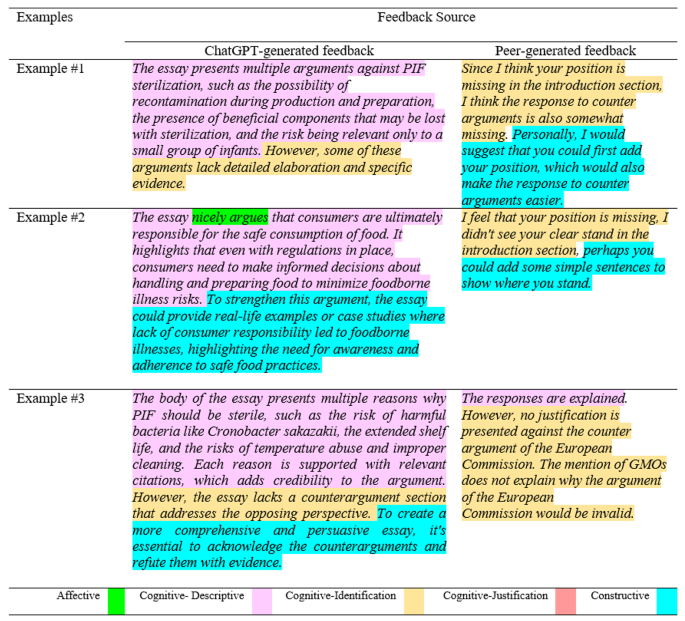

Peer feedback is introduced as an effective learning strategy, especially in large-size classes where teachers face high workloads. However, for complex tasks such as writing an argumentative essay, without support peers may not provide high-quality feedback since it requires a high level of cognitive processing, critical thinking skills, and a deep understanding of the subject. With the promising developments in Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly after the emergence of ChatGPT, there is a global argument that whether AI tools can be seen as a new source of feedback or not for complex tasks. The answer to this question is not completely clear yet as there are limited studies and our understanding remains constrained. In this study, we used ChatGPT as a source of feedback for students’ argumentative essay writing tasks and we compared the quality of ChatGPT-generated feedback with peer feedback. The participant pool consisted of 74 graduate students from a Dutch university. The study unfolded in two phases: firstly, students’ essay data were collected as they composed essays on one of the given topics; subsequently, peer feedback and ChatGPT-generated feedback data were collected through engaging peers in a feedback process and using ChatGPT as a feedback source. Two coding schemes including coding schemes for essay analysis and coding schemes for feedback analysis were used to measure the quality of essays and feedback. Then, a MANOVA analysis was employed to determine any distinctions between the feedback generated by peers and ChatGPT. Additionally, Spearman’s correlation was utilized to explore potential links between the essay quality and the feedback generated by peers and ChatGPT. The results showed a significant difference between feedback generated by ChatGPT and peers. While ChatGPT provided more descriptive feedback including information about how the essay is written, peers provided feedback including information about identification of the problem in the essay. The overarching look at the results suggests a potential complementary role for ChatGPT and students in the feedback process. Regarding the relationship between the quality of essays and the quality of the feedback provided by ChatGPT and peers, we found no overall significant relationship. These findings imply that the quality of the essays does not impact both ChatGPT and peer feedback quality. The implications of this study are valuable, shedding light on the prospective use of ChatGPT as a feedback source, particularly for complex tasks like argumentative essay writing. We discussed the findings and delved into the implications for future research and practical applications in educational contexts.

Introduction

Feedback is acknowledged as one of the most crucial tools for enhancing learning (Banihashem et al., 2022 ). The general and well-accepted definition of feedback conceptualizes it as information provided by an agent (e.g., teacher, peer, self, AI, technology) regarding aspects of one’s performance or understanding (e.g., Hattie & Timplerely, 2007 ). Feedback serves to heighten students’ self-awareness concerning their strengths and areas warranting improvement, through providing actionable steps required to enhance performance (Ramson, 2003 ). The literature abounds with numerous studies that illuminate the positive impact of feedback on diverse dimensions of students’ learning journey including increasing motivation (Amiryousefi & Geld, 2021 ), fostering active engagement (Zhang & Hyland, 2022 ), promoting self-regulation and metacognitive skills (Callender et al., 2016 ; Labuhn et al., 2010 ), and enriching the depth of learning outcomes (Gan et al., 2021 ).

Normally, teachers have primarily assumed the role of delivering feedback, providing insights into students’ performance on specific tasks or their grasp of particular subjects (Konold et al., 2004 ). This responsibility has naturally fallen upon teachers owing to their expertise in the subject matter and their competence to offer constructive input (Diezmann & Watters, 2015 ; Holt-Reynolds, 1999 ; Valero Haro et al., 2023 ). However, teachers’ role as feedback providers has been challenged in recent years as we have witnessed a growth in class sizes due to the rapid advances in technology and the widespread use of digital technologies that resulted in flexible and accessible education (Shi et al., 2019 ). The growth in class sizes has translated into an increased workload for teachers, leading to a pertinent predicament. This situation has directly impacted their capacity to provide personalized and timely feedback to each student, a capability that has encountered limitations (Er et al., 2021 ).

In response to this challenge, various solutions have emerged, among which peer feedback has arisen as a promising alternative instructional approach (Er et al., 2021 ; Gao et al., 2024 ; Noroozi et al., 2023 ; Kerman et al., 2024 ). Peer feedback entails a process wherein students assume the role of feedback providers instead of teachers (Liu & Carless, 2006 ). Involving students in feedback can add value to education in several ways. First and foremost, research indicates that students delve into deeper and more effective learning when they take on the role of assessors, critically evaluating and analyzing their peers’ assignments (Gielen & De Wever, 2015 ; Li et al., 2010 ). Moreover, involving students in the feedback process can augment their self-regulatory awareness, active engagement, and motivation for learning (e.g., Arguedas et al., 2016 ). Lastly, the incorporation of peer feedback not only holds the potential to significantly alleviate teachers’ workload by shifting their responsibilities from feedback provision to the facilitation of peer feedback processes but also nurtures a dynamic learning environment wherein students are actively immersed in the learning journey (e.g., Valero Haro et al., 2023 ).

Despite the advantages of peer feedback, furnishing high-quality feedback to peers remains a challenge. Several factors contribute to this challenge. Primarily, generating effective feedback necessitates a solid understanding of feedback principles, an element that peers often lack (Latifi et al., 2023 ; Noroozi et al., 2016 ). Moreover, offering high-quality feedback is inherently a complex task, demanding substantial cognitive processing to meticulously evaluate peers’ assignments, identify issues, and propose constructive remedies (King, 2002 ; Noroozi et al., 2022 ). Furthermore, the provision of valuable feedback calls for a significant level of domain-specific expertise, which is not consistently possessed by students (Alqassab et al., 2018 ; Kerman et al., 2022 ).

In recent times, advancements in technology, coupled with the emergence of fields like Learning Analytics (LA), have presented promising avenues to elevate feedback practices through the facilitation of scalable, timely, and personalized feedback (Banihashem et al., 2023 ; Deeva et al., 2021 ; Drachsler, 2023 ; Drachsler & Kalz, 2016 ; Pardo et al., 2019 ; Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019 ; Rüdian et al., 2020 ). Yet, a striking stride forward in the field of educational technology has been the advent of a novel Artificial Intelligence (AI) tool known as “ChatGPT,” which has sparked a global discourse on its potential to significantly impact the current education system (Ray, 2023 ). This tool’s introduction has initiated discussions on the considerable ways AI can support educational endeavors (Bond et al., 2024 ; Darvishi et al., 2024 ).

In the context of feedback, AI-powered ChatGPT introduces what is referred to as AI-generated feedback (Farrokhnia et al., 2023 ). While the literature suggests that ChatGPT has the potential to facilitate feedback practices (Dai et al., 2023 ; Katz et al., 2023 ), this literature is very limited and mostly not empirical leading us to realize that our current comprehension of its capabilities in this regard is quite restricted. Therefore, we lack a comprehensive understanding of how ChatGPT can effectively support feedback practices and to what degree it can improve the timeliness, impact, and personalization of feedback, which remains notably limited at this time.

More importantly, considering the challenges we raised for peer feedback, the question is whether AI-generated feedback and more specifically feedback provided by ChatGPT has the potential to provide quality feedback. Taking this into account, there is a scarcity of knowledge and research gaps regarding the extent to which AI tools, specifically ChatGPT, can effectively enhance feedback quality compared to traditional peer feedback. Hence, our research aims to investigate the quality of feedback generated by ChatGPT within the context of essay writing and to juxtapose its quality with that of feedback generated by students.

This study carries the potential to make a substantial contribution to the existing body of recent literature on the potential of AI and in particular ChatGPT in education. It can cast a spotlight on the quality of AI-generated feedback in contrast to peer-generated feedback, while also showcasing the viability of AI tools like ChatGPT as effective automated feedback mechanisms. Furthermore, the outcomes of this study could offer insights into mitigating the feedback-related workload experienced by teachers through the intelligent utilization of AI tools (e.g., Banihashem et al., 2022 ; Er et al., 2021 ; Pardo et al., 2019 ).

However, there might be an argument regarding the rationale for conducting this study within the specific context of essay writing. Addressing this potential query, it is crucial to highlight that essay writing stands as one of the most prevalent yet complex tasks for students (Liunokas, 2020 ). This task is not without its challenges, as evidenced by the extensive body of literature that indicates students often struggle to meet desired standards in their essay composition (e.g., Bulqiyah et al., 2021 ; Noroozi et al., 2016 ;, 2022 ; Latifi et al., 2023 ).

Furthermore, teachers frequently express dissatisfaction with the depth and overall quality of students’ essay writing (Latifi et al., 2023 ). Often, these teachers lament that their feedback on essays remains superficial due to the substantial time and effort required for critical assessment and individualized feedback provision (Noroozi et al., 2016 ;, 2022 ). Regrettably, these constraints prevent them from delving deeper into the evaluation process (Kerman et al., 2022 ).

Hence, directing attention towards the comparison of peer-generated feedback quality and AI-generated feedback quality within the realm of essay writing bestows substantial value upon both research and practical application. This study enriches the academic discourse and informs practical approaches by delivering insights into the adequacy of feedback quality offered by both peers and AI for the domain of essay writing. This investigation serves as a critical step in determining whether the feedback imparted by peers and AI holds the necessary caliber to enhance the craft of essay writing.

The ramifications of addressing this query are noteworthy. Firstly, it stands to significantly alleviate the workload carried by teachers in the process of essay evaluation. By ascertaining the viability of feedback from peers and AI, teachers can potentially reduce the time and effort expended in reviewing essays. Furthermore, this study has the potential to advance the quality of essay compositions. The collaboration between students providing feedback to peers and the integration of AI-powered feedback tools can foster an environment where essays are not only better evaluated but also refined in their content and structure.With this in mind, we aim to tackle the following key questions within the scope of this study:

RQ1. To what extent does the quality of peer-generated and ChatGPT-generated feedback differ in the context of essay writing?