Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Pregnancy week by week

- Fetal presentation before birth

The way a baby is positioned in the uterus just before birth can have a big effect on labor and delivery. This positioning is called fetal presentation.

Babies twist, stretch and tumble quite a bit during pregnancy. Before labor starts, however, they usually come to rest in a way that allows them to be delivered through the birth canal headfirst. This position is called cephalic presentation. But there are other ways a baby may settle just before labor begins.

Following are some of the possible ways a baby may be positioned at the end of pregnancy.

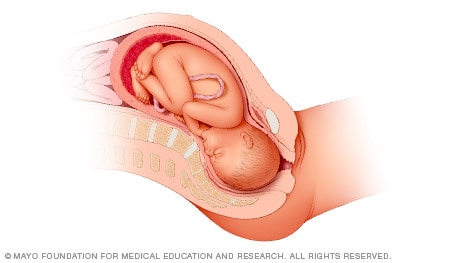

Head down, face down

When a baby is head down, face down, the medical term for it is the cephalic occiput anterior position. This the most common position for a baby to be born in. With the face down and turned slightly to the side, the smallest part of the baby's head leads the way through the birth canal. It is the easiest way for a baby to be born.

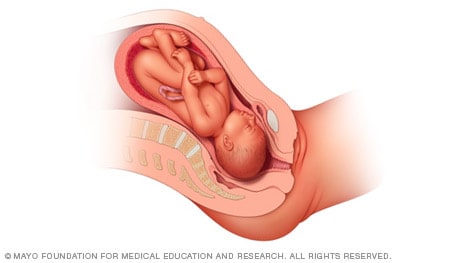

Head down, face up

When a baby is head down, face up, the medical term for it is the cephalic occiput posterior position. In this position, it might be harder for a baby's head to go under the pubic bone during delivery. That can make labor take longer.

Most babies who begin labor in this position eventually turn to be face down. If that doesn't happen, and the second stage of labor is taking a long time, a member of the health care team may reach through the vagina to help the baby turn. This is called manual rotation.

In some cases, a baby can be born in the head-down, face-up position. Use of forceps or a vacuum device to help with delivery is more common when a baby is in this position than in the head-down, face-down position. In some cases, a C-section delivery may be needed.

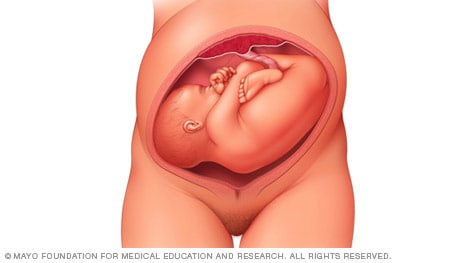

Frank breech

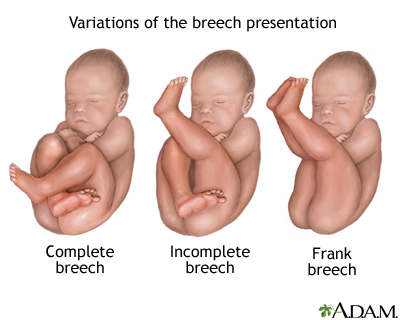

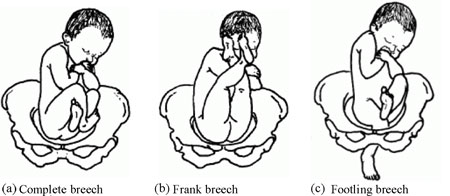

When a baby's feet or buttocks are in place to come out first during birth, it's called a breech presentation. This happens in about 3% to 4% of babies close to the time of birth. The baby shown below is in a frank breech presentation. That's when the knees aren't bent, and the feet are close to the baby's head. This is the most common type of breech presentation.

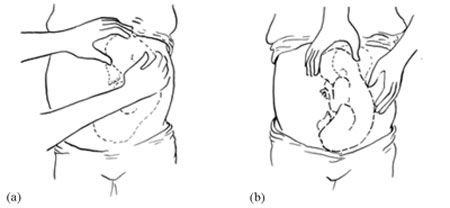

If you are more than 36 weeks into your pregnancy and your baby is in a frank breech presentation, your health care professional may try to move the baby into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. It involves one or two members of the health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

If the procedure isn't successful, or if the baby moves back into a breech position, talk with a member of your health care team about the choices you have for delivery. Most babies in a frank breech position are born by planned C-section.

Complete and incomplete breech

A complete breech presentation, as shown below, is when the baby has both knees bent and both legs pulled close to the body. In an incomplete breech, one or both of the legs are not pulled close to the body, and one or both of the feet or knees are below the baby's buttocks. If a baby is in either of these positions, you might feel kicking in the lower part of your belly.

If you are more than 36 weeks into your pregnancy and your baby is in a complete or incomplete breech presentation, your health care professional may try to move the baby into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. It involves one or two members of the health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

If the procedure isn't successful, or if the baby moves back into a breech position, talk with a member of your health care team about the choices you have for delivery. Many babies in a complete or incomplete breech position are born by planned C-section.

When a baby is sideways — lying horizontal across the uterus, rather than vertical — it's called a transverse lie. In this position, the baby's back might be:

- Down, with the back facing the birth canal.

- Sideways, with one shoulder pointing toward the birth canal.

- Up, with the hands and feet facing the birth canal.

Although many babies are sideways early in pregnancy, few stay this way when labor begins.

If your baby is in a transverse lie during week 37 of your pregnancy, your health care professional may try to move the baby into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. External cephalic version involves one or two members of your health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

If the procedure isn't successful, or if the baby moves back into a transverse lie, talk with a member of your health care team about the choices you have for delivery. Many babies who are in a transverse lie are born by C-section.

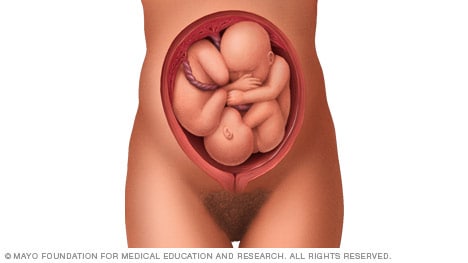

If you're pregnant with twins and only the twin that's lower in the uterus is head down, as shown below, your health care provider may first deliver that baby vaginally.

Then, in some cases, your health care team may suggest delivering the second twin in the breech position. Or they may try to move the second twin into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. External cephalic version involves one or two members of the health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

Your health care team may suggest delivery by C-section for the second twin if:

- An attempt to deliver the baby in the breech position is not successful.

- You do not want to try to have the baby delivered vaginally in the breech position.

- An attempt to move the baby into a head-down position is not successful.

- You do not want to try to move the baby to a head-down position.

In some cases, your health care team may advise that you have both twins delivered by C-section. That might happen if the lower twin is not head down, the second twin has low or high birth weight as compared to the first twin, or if preterm labor starts.

- Landon MB, et al., eds. Normal labor and delivery. In: Gabbe's Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed May 19, 2023.

- Holcroft Argani C, et al. Occiput posterior position. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 19, 2023.

- Frequently asked questions: If your baby is breech. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/if-your-baby-is-breech. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Hofmeyr GJ. Overview of breech presentation. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Strauss RA, et al. Transverse fetal lie. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Chasen ST, et al. Twin pregnancy: Labor and delivery. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Cohen R, et al. Is vaginal delivery of a breech second twin safe? A comparison between delivery of vertex and non-vertex second twins. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2021; doi:10.1080/14767058.2021.2005569.

- Marnach ML (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. May 31, 2023.

Products and Services

- A Book: Obstetricks

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy

- 3rd trimester pregnancy

- Fetal development: The 3rd trimester

- Overdue pregnancy

- Pregnancy due date calculator

- Prenatal care: 3rd trimester

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

- Getting Pregnant

- Registry Builder

- Baby Products

- Birth Clubs

- See all in Community

- Ovulation Calculator

- How To Get Pregnant

- How To Get Pregnant Fast

- Ovulation Discharge

- Implantation Bleeding

- Ovulation Symptoms

- Pregnancy Symptoms

- Am I Pregnant?

- Pregnancy Tests

- See all in Getting Pregnant

- Due Date Calculator

- Pregnancy Week by Week

- Pregnant Sex

- Weight Gain Tracker

- Signs of Labor

- Morning Sickness

- COVID Vaccine and Pregnancy

- Fetal Weight Chart

- Fetal Development

- Pregnancy Discharge

- Find Out Baby Gender

- Chinese Gender Predictor

- See all in Pregnancy

- Baby Name Generator

- Top Baby Names 2023

- Top Baby Names 2024

- How to Pick a Baby Name

- Most Popular Baby Names

- Baby Names by Letter

- Gender Neutral Names

- Unique Boy Names

- Unique Girl Names

- Top baby names by year

- See all in Baby Names

- Baby Development

- Baby Feeding Guide

- Newborn Sleep

- When Babies Roll Over

- First-Year Baby Costs Calculator

- Postpartum Health

- Baby Poop Chart

- See all in Baby

- Average Weight & Height

- Autism Signs

- Child Growth Chart

- Night Terrors

- Moving from Crib to Bed

- Toddler Feeding Guide

- Potty Training

- Bathing and Grooming

- See all in Toddler

- Height Predictor

- Potty Training: Boys

- Potty training: Girls

- How Much Sleep? (Ages 3+)

- Ready for Preschool?

- Thumb-Sucking

- Gross Motor Skills

- Napping (Ages 2 to 3)

- See all in Child

- Photos: Rashes & Skin Conditions

- Symptom Checker

- Vaccine Scheduler

- Reducing a Fever

- Acetaminophen Dosage Chart

- Constipation in Babies

- Ear Infection Symptoms

- Head Lice 101

- See all in Health

- Second Pregnancy

- Daycare Costs

- Family Finance

- Stay-At-Home Parents

- Breastfeeding Positions

- See all in Family

- Baby Sleep Training

- Preparing For Baby

- My Custom Checklist

- My Registries

- Take the Quiz

- Best Baby Products

- Best Breast Pump

- Best Convertible Car Seat

- Best Infant Car Seat

- Best Baby Bottle

- Best Baby Monitor

- Best Stroller

- Best Diapers

- Best Baby Carrier

- Best Diaper Bag

- Best Highchair

- See all in Baby Products

- Why Pregnant Belly Feels Tight

- Early Signs of Twins

- Teas During Pregnancy

- Baby Head Circumference Chart

- How Many Months Pregnant Am I

- What is a Rainbow Baby

- Braxton Hicks Contractions

- HCG Levels By Week

- When to Take a Pregnancy Test

- Am I Pregnant

- Why is Poop Green

- Can Pregnant Women Eat Shrimp

- Insemination

- UTI During Pregnancy

- Vitamin D Drops

- Best Baby Forumla

- Postpartum Depression

- Low Progesterone During Pregnancy

- Baby Shower

- Baby Shower Games

Breech, posterior, transverse lie: What position is my baby in?

Fetal presentation, or how your baby is situated in your womb at birth, is determined by the body part that's positioned to come out first, and it can affect the way you deliver. At the time of delivery, 97 percent of babies are head-down (cephalic presentation). But there are several other possibilities, including feet or bottom first (breech) as well as sideways (transverse lie) and diagonal (oblique lie).

Fetal presentation and position

During the last trimester of your pregnancy, your provider will check your baby's presentation by feeling your belly to locate the head, bottom, and back. If it's unclear, your provider may do an ultrasound or an internal exam to feel what part of the baby is in your pelvis.

Fetal position refers to whether the baby is facing your spine (anterior position) or facing your belly (posterior position). Fetal position can change often: Your baby may be face up at the beginning of labor and face down at delivery.

Here are the many possibilities for fetal presentation and position in the womb.

Medical illustrations by Jonathan Dimes

Head down, facing down (anterior position)

A baby who is head down and facing your spine is in the anterior position. This is the most common fetal presentation and the easiest position for a vaginal delivery.

This position is also known as "occiput anterior" because the back of your baby's skull (occipital bone) is in the front (anterior) of your pelvis.

Head down, facing up (posterior position)

In the posterior position , your baby is head down and facing your belly. You may also hear it called "sunny-side up" because babies who stay in this position are born facing up. But many babies who are facing up during labor rotate to the easier face down (anterior) position before birth.

Posterior position is formally known as "occiput posterior" because the back of your baby's skull (occipital bone) is in the back (posterior) of your pelvis.

Frank breech

In the frank breech presentation, both the baby's legs are extended so that the feet are up near the face. This is the most common type of breech presentation. Breech babies are difficult to deliver vaginally, so most arrive by c-section .

Some providers will attempt to turn your baby manually to the head down position by applying pressure to your belly. This is called an external cephalic version , and it has a 58 percent success rate for turning breech babies. For more information, see our article on breech birth .

Complete breech

A complete breech is when your baby is bottom down with hips and knees bent in a tuck or cross-legged position. If your baby is in a complete breech, you may feel kicking in your lower abdomen.

Incomplete breech

In an incomplete breech, one of the baby's knees is bent so that the foot is tucked next to the bottom with the other leg extended, positioning that foot closer to the face.

Single footling breech

In the single footling breech presentation, one of the baby's feet is pointed toward your cervix.

Double footling breech

In the double footling breech presentation, both of the baby's feet are pointed toward your cervix.

Transverse lie

In a transverse lie, the baby is lying horizontally in your uterus and may be facing up toward your head or down toward your feet. Babies settle this way less than 1 percent of the time, but it happens more commonly if you're carrying multiples or deliver before your due date.

If your baby stays in a transverse lie until the end of your pregnancy, it can be dangerous for delivery. Your provider will likely schedule a c-section or attempt an external cephalic version , which is highly successful for turning babies in this position.

Oblique lie

In rare cases, your baby may lie diagonally in your uterus, with his rump facing the side of your body at an angle.

Like the transverse lie, this position is more common earlier in pregnancy, and it's likely your provider will intervene if your baby is still in the oblique lie at the end of your third trimester.

Was this article helpful?

What to know if your baby is breech

What's a sunny-side up baby?

How your twins’ fetal positions affect labor and delivery

What happens to your baby right after birth

BabyCenter's editorial team is committed to providing the most helpful and trustworthy pregnancy and parenting information in the world. When creating and updating content, we rely on credible sources: respected health organizations, professional groups of doctors and other experts, and published studies in peer-reviewed journals. We believe you should always know the source of the information you're seeing. Learn more about our editorial and medical review policies .

Ahmad A et al. 2014. Association of fetal position at onset of labor and mode of delivery: A prospective cohort study. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology 43(2):176-182. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23929533 Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Gray CJ and Shanahan MM. 2019. Breech presentation. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448063/ Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Hankins GD. 1990. Transverse lie. American Journal of Perinatology 7(1):66-70. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2131781 Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Medline Plus. 2020. Your baby in the birth canal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002060.htm Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Where to go next

Enter search terms to find related medical topics, multimedia and more.

Advanced Search:

- Use “ “ for exact phrases.

- For example: “pediatric abdominal pain”

- Use – to remove results with certain keywords.

- For example: abdominal pain -pediatric

- Use OR to account for alternate keywords.

- For example: teenager OR adolescent

Fetal Presentation, Position, and Lie (Including Breech Presentation)

, MD, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia

Variations in Fetal Position and Presentation

- 3D Models (0)

- Calculators (0)

- Lab Test (0)

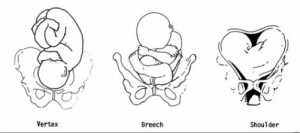

Presentation refers to the part of the fetus’s body that leads the way out through the birth canal (called the presenting part). Usually, the head leads the way, but sometimes the buttocks (breech presentation), shoulder, or face leads the way.

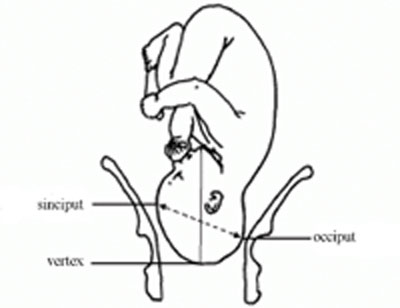

Position refers to whether the fetus is facing backward (occiput anterior) or forward (occiput posterior). The occiput is a bone at the back of the baby's head. Therefore, facing backward is called occiput anterior (facing the mother’s back and facing down when the mother lies on her back). Facing forward is called occiput posterior (facing toward the mother's pubic bone and facing up when the mother lies on her back).

Lie refers to the angle of the fetus in relation to the mother and the uterus. Up-and-down (with the baby's spine parallel to mother's spine, called longitudinal) is normal, but sometimes the lie is sideways (transverse) or at an angle (oblique).

For these aspects of fetal positioning, the combination that is the most common, safest, and easiest for the mother to deliver is the following:

Head first (called vertex or cephalic presentation)

Facing backward (occiput anterior position)

Spine parallel to mother's spine (longitudinal lie)

Neck bent forward with chin tucked

Arms folded across the chest

If the fetus is in a different position, lie, or presentation, labor may be more difficult, and a normal vaginal delivery may not be possible.

Variations in fetal presentation, position, or lie may occur when

The fetus is too large for the mother's pelvis (fetopelvic disproportion).

The fetus has a birth defect Overview of Birth Defects Birth defects, also called congenital anomalies, are physical abnormalities that occur before a baby is born. They are usually obvious within the first year of life. The cause of many birth... read more .

There is more than one fetus (multiple gestation).

Position and Presentation of the Fetus

Some variations in position and presentation that make delivery difficult occur frequently.

Occiput posterior position

In occiput posterior position (sometimes called sunny-side up), the fetus is head first (vertex presentation) but is facing forward (toward the mother's pubic bone—that is, facing up when the mother lies on her back). This is a very common position that is not abnormal, but it makes delivery more difficult than when the fetus is in the occiput anterior position (facing toward the mother's spine—that is facing down when the mother lies on her back).

Breech presentation

In breech presentation, the baby's buttocks or sometimes the feet are positioned to deliver first (before the head).

When delivered vaginally, babies that present buttocks first are more at risk of injury or even death than those that present head first.

The reason for the risks to babies in breech presentation is that the baby's hips and buttocks are not as wide as the head. Therefore, when the hips and buttocks pass through the cervix first, the passageway may not be wide enough for the head to pass through. In addition, when the head follows the buttocks, the neck may be bent slightly backwards. The neck being bent backward increases the width required for delivery as compared to when the head is angled forward with the chin tucked, which is the position that is easiest for delivery. Thus, the baby’s body may be delivered and then the head may get caught and not be able to pass through the birth canal. When the baby’s head is caught, this puts pressure on the umbilical cord in the birth canal, so that very little oxygen can reach the baby. Brain damage due to lack of oxygen is more common among breech babies than among those presenting head first.

Breech presentation is more likely to occur in the following circumstances:

Labor starts too soon (preterm labor).

Sometimes the doctor can turn the fetus to be head first before labor begins by doing a procedure that involves pressing on the pregnant woman’s abdomen and trying to turn the baby around. Trying to turn the baby is called an external cephalic version and is usually done at 37 or 38 weeks of pregnancy. Sometimes women are given a medication (such as terbutaline ) during the procedure to prevent contractions.

Other presentations

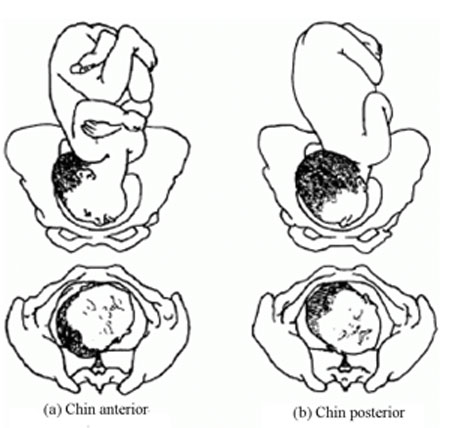

In face presentation, the baby's neck arches back so that the face presents first rather than the top of the head.

In brow presentation, the neck is moderately arched so that the brow presents first.

Usually, fetuses do not stay in a face or brow presentation. These presentations often change to a vertex (top of the head) presentation before or during labor. If they do not, a cesarean delivery is usually recommended.

In transverse lie, the fetus lies horizontally across the birth canal and presents shoulder first. A cesarean delivery is done, unless the fetus is the second in a set of twins. In such a case, the fetus may be turned to be delivered through the vagina.

Was This Page Helpful?

Test your knowledge

Brought to you by Merck & Co, Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA (known as MSD outside the US and Canada)—dedicated to using leading-edge science to save and improve lives around the world. Learn more about the MSD Manuals and our commitment to Global Medical Knowledge .

- Permissions

- Cookie Settings

- Terms of use

- Veterinary Edition

- IN THIS TOPIC

Enter search terms to find related medical topics, multimedia and more.

Advanced Search:

- Use “ “ for exact phrases.

- For example: “pediatric abdominal pain”

- Use – to remove results with certain keywords.

- For example: abdominal pain -pediatric

- Use OR to account for alternate keywords.

- For example: teenager OR adolescent

Fetal Presentation, Position, and Lie (Including Breech Presentation)

, MD, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia

- 3D Models (0)

- Calculators (0)

Abnormal fetal lie or presentation may occur due to fetal size, fetal anomalies, uterine structural abnormalities, multiple gestation, or other factors. Diagnosis is by examination or ultrasonography. Management is with physical maneuvers to reposition the fetus, operative vaginal delivery Operative Vaginal Delivery Operative vaginal delivery involves application of forceps or a vacuum extractor to the fetal head to assist during the second stage of labor and facilitate delivery. Indications for forceps... read more , or cesarean delivery Cesarean Delivery Cesarean delivery is surgical delivery by incision into the uterus. The rate of cesarean delivery was 32% in the United States in 2021 (see March of Dimes: Delivery Method). The rate has fluctuated... read more .

Terms that describe the fetus in relation to the uterus, cervix, and maternal pelvis are

Fetal presentation: Fetal part that overlies the maternal pelvic inlet; vertex (cephalic), face, brow, breech, shoulder, funic (umbilical cord), or compound (more than one part, eg, shoulder and hand)

Fetal position: Relation of the presenting part to an anatomic axis; for transverse presentation, occiput anterior, occiput posterior, occiput transverse

Fetal lie: Relation of the fetus to the long axis of the uterus; longitudinal, oblique, or transverse

Normal fetal lie is longitudinal, normal presentation is vertex, and occiput anterior is the most common position.

Abnormal fetal lie, presentation, or position may occur with

Fetopelvic disproportion (fetus too large for the pelvic inlet)

Fetal congenital anomalies

Uterine structural abnormalities (eg, fibroids, synechiae)

Multiple gestation

Several common types of abnormal lie or presentation are discussed here.

Transverse lie

Fetal position is transverse, with the fetal long axis oblique or perpendicular rather than parallel to the maternal long axis. Transverse lie is often accompanied by shoulder presentation, which requires cesarean delivery.

Breech presentation

There are several types of breech presentation.

Frank breech: The fetal hips are flexed, and the knees extended (pike position).

Complete breech: The fetus seems to be sitting with hips and knees flexed.

Single or double footling presentation: One or both legs are completely extended and present before the buttocks.

Types of breech presentations

Breech presentation makes delivery difficult ,primarily because the presenting part is a poor dilating wedge. Having a poor dilating wedge can lead to incomplete cervical dilation, because the presenting part is narrower than the head that follows. The head, which is the part with the largest diameter, can then be trapped during delivery.

Additionally, the trapped fetal head can compress the umbilical cord if the fetal umbilicus is visible at the introitus, particularly in primiparas whose pelvic tissues have not been dilated by previous deliveries. Umbilical cord compression may cause fetal hypoxemia.

Predisposing factors for breech presentation include

Preterm labor Preterm Labor Labor (regular uterine contractions resulting in cervical change) that begins before 37 weeks gestation is considered preterm. Risk factors include prelabor rupture of membranes, uterine abnormalities... read more

Multiple gestation Multifetal Pregnancy Multifetal pregnancy is presence of > 1 fetus in the uterus. Multifetal (multiple) pregnancy occurs in up to 1 of 30 deliveries. Risk factors for multiple pregnancy include Ovarian stimulation... read more

Uterine abnormalities

Fetal anomalies

If delivery is vaginal, breech presentation may increase risk of

Umbilical cord prolapse

Perinatal death

It is best to detect abnormal fetal lie or presentation before delivery. During routine prenatal care, clinicians assess fetal lie and presentation with physical examination in the late third trimester. Ultrasonography can also be done. If breech presentation is detected, external cephalic version can sometimes move the fetus to vertex presentation before labor, usually at 37 or 38 weeks. This technique involves gently pressing on the maternal abdomen to reposition the fetus. A dose of a short-acting tocolytic ( terbutaline 0.25 mg subcutaneously) may help. The success rate is about 50 to 75%. For persistent abnormal lie or presentation, cesarean delivery is usually done at 39 weeks or when the woman presents in labor.

Face or brow presentation

In face presentation, the head is hyperextended, and position is designated by the position of the chin (mentum). When the chin is posterior, the head is less likely to rotate and less likely to deliver vaginally, necessitating cesarean delivery.

Brow presentation usually converts spontaneously to vertex or face presentation.

Occiput posterior position

The most common abnormal position is occiput posterior.

The fetal neck is usually somewhat deflexed; thus, a larger diameter of the head must pass through the pelvis.

Progress may arrest in the second phase of labor. Operative vaginal delivery Operative Vaginal Delivery Operative vaginal delivery involves application of forceps or a vacuum extractor to the fetal head to assist during the second stage of labor and facilitate delivery. Indications for forceps... read more or cesarean delivery Cesarean Delivery Cesarean delivery is surgical delivery by incision into the uterus. The rate of cesarean delivery was 32% in the United States in 2021 (see March of Dimes: Delivery Method). The rate has fluctuated... read more is often required.

Position and Presentation of the Fetus

If a fetus is in the occiput posterior position, operative vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery is often required.

In breech presentation, the presenting part is a poor dilating wedge, which can cause the head to be trapped during delivery, often compressing the umbilical cord.

For breech presentation, usually do cesarean delivery at 39 weeks or during labor, but external cephalic version is sometimes successful before labor, usually at 37 or 38 weeks.

Drugs Mentioned In This Article

Was This Page Helpful?

Test your knowledge

Brought to you by Merck & Co, Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA (known as MSD outside the US and Canada) — dedicated to using leading-edge science to save and improve lives around the world. Learn more about the Merck Manuals and our commitment to Global Medical Knowledge.

- Permissions

- Cookie Settings

- Terms of use

- Veterinary Manual

- IN THIS TOPIC

Fetal Presentation: Baby’s First Pose

Share this post

Occiput Anterior

Occiput posterior, transverse position, complete breech, frank breech, changing fetal presentation, baby positions.

The position in which your baby develops is called the “fetal presentation.” During most of your pregnancy, the baby will be curled up in a ball – that’s why we call it the “fetal position.” The baby might flip around over the course of development, which is why you can sometimes feel a foot poking into your side or an elbow prodding your bellybutton. As you get closer to delivery, the baby will change positions and move lower in your uterus in preparation. Over the last part of your pregnancy, your doctor or medical care provider will monitor the baby’s position to keep an eye out for any potential problems.

In the occiput anterior position, the baby is pointed headfirst toward the birth canal and is facing down – toward your back. This is the easiest possible position for delivery because it allows the crown of the baby’s head to pass through first, followed by the shoulders and the rest of the body. The crown of the head is the narrowest part, so it can lead the way for the rest of the head.

The baby’s head will move slowly downward as you get closer to delivery until it “engages” with your pelvis. At that point, the baby’s head will fit snugly and won’t be able to wobble around. That’s exactly where you want to be just before labor. The occiput anterior position causes the least stress on your little one and the easiest labor for you.

In the occiput posterior position, the baby is pointed headfirst toward the birth canal but is facing upward, toward your stomach. This can trap the baby’s head under your pubic bone, making it harder to get out through the birth canal. In most cases, a baby in the occiput posterior position will either turn around naturally during the course of labor or your doctor or midwife may help it along manually or with forceps.

In a transverse position, the baby is sideways across the birth canal rather than head- or feet-first. It’s rare for a baby to stay in this position all the way up to delivery, but your doctor may attempt to gently push on your abdomen until the baby is in a more favorable fetal presentation. If you go into labor while the baby is in a transverse position, your medical care provider will likely recommend a c-section to avoid stressing or injuring the baby.

Breech Presentation

If the baby’s legs or buttocks are leading the way instead of the head, it’s called a breech presentation. It’s much harder to deliver in this position – the baby’s limbs are unlikely to line up all in the right direction and the birth canal likely won’t be stretched enough to allow the head to pass. Breech presentation used to be extremely dangerous for mothers and children both, and it’s still not easy, but medical intervention can help.

Sometimes, the baby will turn around and you’ll be able to deliver vaginally. Most healthcare providers, however, recommend a cesarean section for all breech babies because of the risks of serious injury to both mother and child in a breech vaginal delivery.

A complete breech position refers to the baby being upside down for delivery – feet first and head up. The baby’s legs are folded up and the feet are near the buttocks.

In a frank breech position, the baby’s legs are extended and the baby’s buttocks are closest to the birth canal. This is the most common breech presentation .

By late in your pregnancy, your baby can already move around – you’re probably feeling those kicks! Unfortunately, your little one doesn’t necessarily know how to aim for the birth canal. If the baby isn’t in the occiput anterior position by about 32 weeks, your doctor or midwife will typically recommend trying adjust the fetal presentation. They’ll use monitors to keep an eye on the baby and watch for signs of stress as they push and lift on your belly to coax your little one into the right spot. Your doctor may also advise you to try certain exercises at home to encourage the baby to move into the proper position. For example, getting on your hands and knees for a few minutes every day can help bring the baby around. You can also put cushions on your chairs to make sure your hips are always elevated, which can help move things into the right place. It’s important to start working on the proper fetal position early, as it becomes much harder to adjust after about 37 weeks when there’s less room to move around.

In many cases, the baby will eventually line up properly before delivery. Sometimes, however, the baby is still in the wrong spot by the time you go into labor. Your doctor or midwife may be able to move the baby during labor using forceps or ventouse . If that’s not possible, it’s generally safer for you and the baby if you deliver by c-section.

Image Credit and License

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Stages of Pregnancy

- Foods to Avoid

- Medicines to Avoid

- Pregnancy Road Map

Birth Injuries

- Cerebral Palsy

- Brachial Plexus Injuries & Erb’s Palsy

- Brain Damage

- Meconium Aspiration

- Bone Fractures

- Nerve Damage

Newborn Care

- Baby Development

Legal Issues

- Birth Injury vs. Birth Defect

- Birth Injury Lawsuits

- Proving Your Case

- Elements Of A Case

- Email Address *

- Phone Number *

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Variation in fetal presentation

- Report problem with article

- View revision history

Citation, DOI, disclosures and article data

At the time the article was created The Radswiki had no recorded disclosures.

At the time the article was last revised Yuranga Weerakkody had no financial relationships to ineligible companies to disclose.

- Delivery presentations

- Variation in delivary presentation

- Abnormal fetal presentations

There can be many variations in the fetal presentation which is determined by which part of the fetus is projecting towards the internal cervical os . This includes:

cephalic presentation : fetal head presenting towards the internal cervical os, considered normal and occurs in the vast majority of births (~97%); this can have many variations which include

left occipito-anterior (LOA)

left occipito-posterior (LOP)

left occipito-transverse (LOT)

right occipito-anterior (ROA)

right occipito-posterior (ROP)

right occipito-transverse (ROT)

straight occipito-anterior

straight occipito-posterior

breech presentation : fetal rump presenting towards the internal cervical os, this has three main types

frank breech presentation (50-70% of all breech presentation): hips flexed, knees extended (pike position)

complete breech presentation (5-10%): hips flexed, knees flexed (cannonball position)

footling presentation or incomplete (10-30%): one or both hips extended, foot presenting

other, e.g one leg flexed and one leg extended

shoulder presentation

cord presentation : umbilical cord presenting towards the internal cervical os

- 1. Fox AJ, Chapman MG. Longitudinal ultrasound assessment of fetal presentation: a review of 1010 consecutive cases. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;46 (4): 341-4. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.2006.00603.x - Pubmed citation

- 2. Merz E, Bahlmann F. Ultrasound in obstetrics and gynecology. Thieme Medical Publishers. (2005) ISBN:1588901475. Read it at Google Books - Find it at Amazon

Incoming Links

- Obstetric curriculum

- Cord presentation

- Polyhydramnios

- Footling presentation

- Normal obstetrics scan (third trimester singleton)

Promoted articles (advertising)

ADVERTISEMENT: Supporters see fewer/no ads

By Section:

- Artificial Intelligence

- Classifications

- Imaging Technology

- Interventional Radiology

- Radiography

- Central Nervous System

- Gastrointestinal

- Gynaecology

- Haematology

- Head & Neck

- Hepatobiliary

- Interventional

- Musculoskeletal

- Paediatrics

- Not Applicable

Radiopaedia.org

- Feature Sponsor

- Expert advisers

- Pregnancy Classes

Breech Births

In the last weeks of pregnancy, a baby usually moves so his or her head is positioned to come out of the vagina first during birth. This is called a vertex presentation. A breech presentation occurs when the baby’s buttocks, feet, or both are positioned to come out first during birth. This happens in 3–4% of full-term births.

What are the different types of breech birth presentations?

- Complete breech: Here, the buttocks are pointing downward with the legs folded at the knees and feet near the buttocks.

- Frank breech: In this position, the baby’s buttocks are aimed at the birth canal with its legs sticking straight up in front of his or her body and the feet near the head.

- Footling breech: In this position, one or both of the baby’s feet point downward and will deliver before the rest of the body.

What causes a breech presentation?

The causes of breech presentations are not fully understood. However, the data show that breech birth is more common when:

- You have been pregnant before

- In pregnancies of multiples

- When there is a history of premature delivery

- When the uterus has too much or too little amniotic fluid

- When there is an abnormally shaped uterus or a uterus with abnormal growths, such as fibroids

- The placenta covers all or part of the opening of the uterus placenta previa

How is a breech presentation diagnosed?

A few weeks prior to the due date, the health care provider will place her hands on the mother’s lower abdomen to locate the baby’s head, back, and buttocks. If it appears that the baby might be in a breech position, they can use ultrasound or pelvic exam to confirm the position. Special x-rays can also be used to determine the baby’s position and the size of the pelvis to determine if a vaginal delivery of a breech baby can be safely attempted.

Can a breech presentation mean something is wrong?

Even though most breech babies are born healthy, there is a slightly elevated risk for certain problems. Birth defects are slightly more common in breech babies and the defect might be the reason that the baby failed to move into the right position prior to delivery.

Can a breech presentation be changed?

It is preferable to try to turn a breech baby between the 32nd and 37th weeks of pregnancy . The methods of turning a baby will vary and the success rate for each method can also vary. It is best to discuss the options with the health care provider to see which method she recommends.

Medical Techniques

External Cephalic Version (EVC) is a non-surgical technique to move the baby in the uterus. In this procedure, a medication is given to help relax the uterus. There might also be the use of an ultrasound to determine the position of the baby, the location of the placenta and the amount of amniotic fluid in the uterus.

Gentle pushing on the lower abdomen can turn the baby into the head-down position. Throughout the external version the baby’s heartbeat will be closely monitored so that if a problem develops, the health care provider will immediately stop the procedure. ECV usually is done near a delivery room so if a problem occurs, a cesarean delivery can be performed quickly. The external version has a high success rate and can be considered if you have had a previous cesarean delivery.

ECV will not be tried if:

- You are carrying more than one fetus

- There are concerns about the health of the fetus

- You have certain abnormalities of the reproductive system

- The placenta is in the wrong place

- The placenta has come away from the wall of the uterus ( placental abruption )

Complications of EVC include:

- Prelabor rupture of membranes

- Changes in the fetus’s heart rate

- Placental abruption

- Preterm labor

Vaginal delivery versus cesarean for breech birth?

Most health care providers do not believe in attempting a vaginal delivery for a breech position. However, some will delay making a final decision until the woman is in labor. The following conditions are considered necessary in order to attempt a vaginal birth:

- The baby is full-term and in the frank breech presentation

- The baby does not show signs of distress while its heart rate is closely monitored.

- The process of labor is smooth and steady with the cervix widening as the baby descends.

- The health care provider estimates that the baby is not too big or the mother’s pelvis too narrow for the baby to pass safely through the birth canal.

- Anesthesia is available and a cesarean delivery possible on short notice

What are the risks and complications of a vaginal delivery?

In a breech birth, the baby’s head is the last part of its body to emerge making it more difficult to ease it through the birth canal. Sometimes forceps are used to guide the baby’s head out of the birth canal. Another potential problem is cord prolapse . In this situation the umbilical cord is squeezed as the baby moves toward the birth canal, thus slowing the baby’s supply of oxygen and blood. In a vaginal breech delivery, electronic fetal monitoring will be used to monitor the baby’s heartbeat throughout the course of labor. Cesarean delivery may be an option if signs develop that the baby may be in distress.

When is a cesarean delivery used with a breech presentation?

Most health care providers recommend a cesarean delivery for all babies in a breech position, especially babies that are premature. Since premature babies are small and more fragile, and because the head of a premature baby is relatively larger in proportion to its body, the baby is unlikely to stretch the cervix as much as a full-term baby. This means that there might be less room for the head to emerge.

Want to Know More?

- Creating Your Birth Plan

- Labor & Birth Terms to Know

- Cesarean Birth After Care

Compiled using information from the following sources:

- ACOG: If Your Baby is Breech

- William’s Obstetrics Twenty-Second Ed. Cunningham, F. Gary, et al, Ch. 24.

- Danforth’s Obstetrics and Gynecology Ninth Ed. Scott, James R., et al, Ch. 21.

BLOG CATEGORIES

- Can I get pregnant if… ? 3

- Child Adoption 19

- Fertility 54

- Pregnancy Loss 11

- Breastfeeding 29

- Changes In Your Body 5

- Cord Blood 4

- Genetic Disorders & Birth Defects 17

- Health & Nutrition 2

- Is it Safe While Pregnant 54

- Labor and Birth 65

- Multiple Births 10

- Planning and Preparing 24

- Pregnancy Complications 68

- Pregnancy Concerns 62

- Pregnancy Health and Wellness 149

- Pregnancy Products & Tests 8

- Pregnancy Supplements & Medications 14

- The First Year 41

- Week by Week Newsletter 40

- Your Developing Baby 16

- Options for Unplanned Pregnancy 18

- Paternity Tests 2

- Pregnancy Symptoms 5

- Prenatal Testing 16

- The Bumpy Truth Blog 7

- Uncategorized 4

- Abstinence 3

- Birth Control Pills, Patches & Devices 21

- Women's Health 34

- Thank You for Your Donation

- Unplanned Pregnancy

- Getting Pregnant

- Healthy Pregnancy

- Privacy Policy

Share this post:

Similar post.

Episiotomy: Advantages & Complications

Retained Placenta

What is Dilation in Pregnancy?

Track your baby’s development, subscribe to our week-by-week pregnancy newsletter.

- The Bumpy Truth Blog

- Fertility Products Resource Guide

Pregnancy Tools

- Ovulation Calendar

- Baby Names Directory

- Pregnancy Due Date Calculator

- Pregnancy Quiz

Pregnancy Journeys

- Partner With Us

- Corporate Sponsors

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Health Topics

- Drugs & Supplements

- Medical Tests

- Medical Encyclopedia

- About MedlinePlus

- Customer Support

Breech - series—Types of breech presentation

- Go to slide 1 out of 7

- Go to slide 2 out of 7

- Go to slide 3 out of 7

- Go to slide 4 out of 7

- Go to slide 5 out of 7

- Go to slide 6 out of 7

- Go to slide 7 out of 7

There are three types of breech presentation: complete, incomplete, and frank.

Complete breech is when both of the baby's knees are bent and his feet and bottom are closest to the birth canal.

Incomplete breech is when one of the baby's knees is bent and his foot and bottom are closest to the birth canal.

Frank breech is when the baby's legs are folded flat up against his head and his bottom is closest to the birth canal.

There is also footling breech where one or both feet are presenting.

Review Date 11/21/2022

Updated by: LaQuita Martinez, MD, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Emory Johns Creek Hospital, Alpharetta, GA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.

Related MedlinePlus Health Topics

- Childbirth Problems

Obstetric and Newborn Care I

10.02 key terms related to fetal positions.

a. “Lie” of an Infant.

Lie refers to the position of the spinal column of the fetus in relation to the spinal column of the mother. There are two types of lie, longitudinal and transverse. Longitudinal indicates that the baby is lying lengthwise in the uterus, with its head or buttocks down. Transverse indicates that the baby is lying crosswise in the uterus.

b. Presentation/Presenting Part.

Presentation refers to that part of the fetus that is coming through (or attempting to come through) the pelvis first.

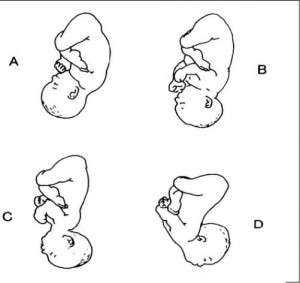

(1) Types of presentations (see figure 10-1). The vertex or cephalic (head), breech, and shoulder are the three types of presentations. In vertex or cephalic, the head comes down first. In breech, the feet or buttocks comes down first, and last–in shoulder, the arm or shoulder comes down first. This is usually referred to as a transverse lie.

(2) Percentages of presentations.

(a) Head first is the most common-96 percent.

(b) Breech is the next most common-3.5 percent.

(c) Shoulder or arm is the least common-5 percent.

(3) Specific presentation may be evaluated by several ways.

(a) Abdominal palpation-this is not always accurate.

(b) Vaginal exam–this may give a good indication but not infallible.

(c) Ultrasound–this confirms assumptions made by previous methods.

(d) X-ray–this confirms the presentation, but is used only as a last resort due to possible harm to the fetus as a result of exposure to radiation.

c. Attitude.

This is the degree of flexion of the fetus body parts (body, head, and extremities) to each other. Flexion is resistance to the descent of the fetus down the birth canal, which causes the head to flex or bend so that the chin approaches the chest.

(1) Types of attitude (see figure 10-2).

(a) Complete flexion. This is normal attitude in cephalic presentation. With cephalic, there is complete flexion at the head when the fetus “chin is on his chest.” This allows the smallest cephalic diameter to enter the pelvis, which gives the fewest mechanical problems with descent and delivery.

(b) Moderate flexion or military attitude. In cephalic presentation, the fetus head is only partially flexed or not flexed. It gives the appearance of a military person at attention. A larger diameter of the head would be coming through the passageway.

(c) Poor flexion or marked extension. In reference to the fetus head, it is extended or bent backwards. This would be called a brow presentation. It is difficult to deliver because the widest diameter of the head enters the pelvis first. This type of cephalic presentation may require a C/Section if the attitude cannot be changed.

(d) Hyperextended. In reference to the cephalic position, the fetus head is extended all the way back. This allows a face or chin to present first in the pelvis. If there is adequate room in the pelvis, the fetus may be delivered vaginally.

(2) Areas to look at for flexion.

(a) Head-discussed in previous paragraph, 10-2c(1).

(b) Thighs-flexed on the abdomen.

(c) Knees-flexed at the knee joints.

(d) Arches of the feet-rested on the anterior surface of the legs.

(e) Arms-crossed over the thorax.

(3) Attitude of general flexion. This is when all of the above areas are flexed appropriately as described.

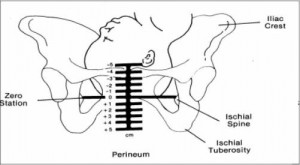

d. Station.

This refers to the depth that the presenting part has descended into the pelvis in relation to the ischial spines of the mother’s pelvis. Measurement of the station is as follows:

(1) The degree of advancement of the presenting part through the pelvis is measured in centimeters.

(2) The ischial spines is the dividing line between plus and minus stations.

(3) Above the ischial spines is referred to as -1 to -5, the numbers going higher as the presenting part gets higher in the pelvis (see figure10-3).

(4) The ischial spines is zero (0) station.

(5) Below the ischial spines is referred to +1 to +5, indicating the lower the presenting part advances.

e. Engagement.

This refers to the entrance of the presenting part of the fetus into the true pelvis or the largest diameter of the presenting part into the true pelvis. In relation to the head, the fetus is said to be engaged when it reaches the midpelvis or at a zero (0) station. Once the fetus is engaged, it (fetus) does not go back up. Prior to engagement occurring, the fetus is said to be “floating” or ballottable.

f. Position.

This is the relationship between a predetermined point of reference or direction on the presenting part of the fetus to the pelvis of the mother.

(1) The maternal pelvis is divided into quadrants.

(a) Right and left side, viewed as the mother would.

(b) Anterior and posterior. This is a line cutting the pelvis in the middle from side to side. The top half is anterior and the bottom half is posterior.

(c) The quadrants never change, but sometimes it is confusing because the student or physician’s viewpoint changes.

NOTE: Remember that when you are describing the quadrants, view them as the mother would.

(2) Specific points on the fetus.

(a) Cephalic or head presentation.

1 Occiput (O). This refers to the Y sutures on the top of the head.

2 Brow or fronto (F). This refers to the diamond sutures or anterior fontanel on the head.

3 Face or chin presentation (M). This refers to the mentum or chin.

(b) Breech or butt presentation.

1 Sacrum or coccyx (S). This is the point of reference.

2 Breech birth is associated with a higher perinatal mortality.

(c) Shoulder presentation.

1 This would be seen with a transverse lie.

2. Scapula (Sc) or its upper tip, the acromion (A) would be used for the point of reference.

(3) Coding of positions.

(a) Coding simplifies explaining the various positions.

1 The first letter of the code tells which side of the pelvis the fetus reference point is on (R for right, L for left).

2 The second letter tells what reference point on the fetus is being used (Occiput-O, Fronto-F, Mentum-M, Breech-S, Shoulder-Sc or A).

3 The last letter tells which half of the pelvis the reference point is in (anterior-A, posterior-P, transverse or in the middle-T).

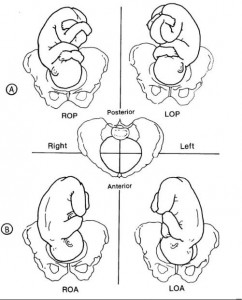

(b) Each presenting part has the possibility of six positions. They are normally recognized for each position–using “occiput” as the reference point.

1 Left occiput anterior (LOA).

2 Left occiput posterior (LOP).

3 Left occiput transverse (LOT).

4 Right occiput anterior (ROA).

5. Right occiput posterior (ROP).

6 Right occiput transverse (ROT).

(c) A transverse position does not use a first letter and is not the same as a transverse lie or presentation.

1 Occiput at sacrum (O.S.) or occiput at posterior (O.P.).

2 Occiput at pubis (O.P.) or occiput at anterior (O.A.).

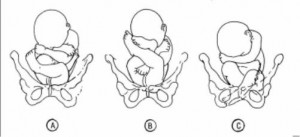

(4) Types of breech presentations (see figure10-4).

(a) Complete or full breech. This involves flexion of the fetus legs. It looks like the fetus is sitting in a tailor fashion. The buttocks and feet appear at the vaginal opening almost simultaneously.

A–Complete. B–Frank. C–Incomplete.

(b) Frank and single breech. The fetus thighs are flexed on his abdomen. His legs are against his trunk and feet are in his face (foot-in-mouth posture). This is the most common and easiest breech presentation to deliver.

(c) Incomplete breech. The fetus feet or knees will appear first. His feet are labeled single or double footing, depending on whether 1 or 2 feet appear first.

(5) Observations about positions (see figure 10-5).

(a) LOA and ROA positions are the most common and permit relatively easy delivery.

(b) LOP and ROP positions usually indicate labor may be longer and harder, and the mother will experience severe backache.

(c) Knowing positions will help you to identify where to look for FHT’s.

1 Breech. This will be upper R or L quad, above the umbilicus.

2 Vertex. This will be lower R or L quad, below the umbilicus.

(d) An occiput in the posterior quadrant means that you will feel lumpy fetal parts, arms and legs (see figure 10-5 A). If delivered in that position, the infant will come out looking up.

(e) An occiput in the anterior quadrant means that you will feel a more smooth back (see figure 10-5 B). If delivered in that position, the infant will come out looking down at the floor.

Distance Learning for Medical and Nursing Professionals

Contemporary Obstetrics and Gynecology for Developing Countries pp 193–201 Cite as

Breech Presentation and Delivery

- Uche A. Menakaya 5 , 6

- First Online: 06 August 2021

1228 Accesses

Breech presentation refers to the presence of the fetal buttocks, knees or feet at the lower pole of the gravid uterus during pregnancy. At term, up to 4% of pregnancies are breech. The term breech foetus faces peculiar challenges in resource restricted countries with its lack of consensus on management and limited investments in health care systems and training of health care providers. This chapter describes the different types of breech presentation, the risk factors for term breech presentation and the antenatal management options including external cephalic version available to women presenting with a term breech foetus. The chapter also describes the techniques for performing external cephalic version and the maneuvers critical for a successful vaginal breech delivery and highlights the limitations of the evidence for and against vaginal breech delivery in the sub-Saharan continent.

- Term breech

- Caesarean section

- External cephalic version

- Vaginal breech delivery

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Hofmeyr GJ, Lockwood CJ, Barss VA. Overview of issues related to breech presentation: Uptodate Topic 6776 Version 24.0.

Google Scholar

Scheer K, Nubar J. Variation of fetal presentation with gestational age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;125(2):269–70.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hickok DE, Gordon DC, Milberg JA, Williams MA, Daling JR. The frequency of breech presentation by gestational age at birth: a large population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(3):851–2.

Albrechtsen S, Rasmussen S, Dalaker K, Irgens LM. Reproductive career after breech presentation: subsequent pregnancy rates, inter pregnancy interval, and recurrence. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92(3):345.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ford JB, Roberts CL, Nassar N, Giles W, Morris JM. Recurrence of breech presentation in consecutive pregnancies. BJOG. 2010;117(7):830.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Nordtveit TI, Melve KK, Albrechtsen S, Skjaerven R. Maternal and paternal contribution to intergenerational recurrence of breech delivery: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7649):872.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hofmeyr GJ. Abnormal fetal presentation and position. In: Chapter 34, Turnbull's obstetrics; 2000.

Thorp JM Jr, Jenkins T, Watson W. Utility of Leopold maneuvers in screening for malpresentation. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78(3 Pt 1):394.

PubMed Google Scholar

Grootscholten K, Kok M, Oei SG, Mol BW, van der Post JA. External cephalic version-related risks: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(5):1143.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R, West HM. External cephalic version for breech presentation at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Apr;4:CD000083.

De Hundt M, Velzel J, de Groot CJ, Mol BW, Kok M. Mode of delivery after successful external cephalic version: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1327.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Tan JM, Macario A, Carvalho B, Druzin ML, El-Sayed YY. Cost-effectiveness of external cephalic version for term breech presentation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10:3.

Gifford DS, Keeler E, Kahn KL. Reductions in cost and caesarean rate by routine use of external cephalic version: a decision analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(6):930–6.

Ben-Meir A, Erez Y, Sela HY, Shveiky D, Tsafrir A, Ezra Y. Prognostic parameters for successful external cephalic version. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21(9):660.

Kok M, Cnossen J, Gravendeel L, van der Post J, Opmeer B, Mol BW. Clinical factors to predict the outcome of external cephalic version: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(6):630.e1.

Article Google Scholar

Ebner F, Friedl TW, Leinert E, Schramm A, Reister F, Lato K, Janni W, De Gregorio N. Predictors for a successful external cephalic version: a single centre experience. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293(4):749.

Buhimschi CS, Buhimschi IA, Wehrum MJ, Molaskey-Jones S, Sfakianaki AK, Pettker CM, Thung S, Campbell KH, Dulay AT, Funai EF, Bahtiyar MO. Ultrasonographic evaluation of myometrial thickness and prediction of a successful external cephalic version. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(4):913–20.

Fortunato SJ, Mercer LJ, Guzick DS. External cephalic version with tocolysis: factors associated with success. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72(1):59.

Boucher M, Bujold E, Marquette GP, Vezina Y. The relationship between amniotic fluid index and successful external cephalic version: a 14-year experience. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(3):751.

Hofmeyr GJ, Sadan O, Myer IG, Galal KC, Simko G. External cephalic version and spontaneous version rates: ethnic and other determinants. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1986;93(1):13.

Hofmeyr GJ. Effect of external cephalic version in late pregnancy on breech presentation and caesarean section rate: a controlled trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1983;90(5):392.

Collins S, Ellaway P, Harrington D, Pandit M, Impey LW. The complications of external cephalic version: results from 805 consecutive attempts. BJOG. 2007;114(5):636.

Holmes WR, Hofmeyr GJ. Management of breech presentation in areas with high prevalence of HIV infection. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004;87(3):272.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. External cephalic version. Practice Bulletin No. 161. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:e54.

Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. External Cephalic Version (ECV) and Reducing the Incidence of Breech Presentation (Green-top Guideline No. 20a). https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-researchservices/guidelines/gtg20a/ . Accessed on 12 May 2016.

Ben-Meir A, Elram T, Tsafrir A, Elchalal U, Ezra Y. The incidence of spontaneous version after failed external cephalic version. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(2):157.e1.

Hutton EK, Hannah ME, Ross SJ, Delisle MF, Carson GD, Windrim R, Ohlsson A, Willan AR, Gafni A, Sylvestre G, Natale R, Barrett Y, Pollard JK, Dunn MS, Turtle P. Early ECV2 Trial Collaborative Group. The Early External Cephalic Version (ECV) 2 Trial: an international multicentre randomised controlled trial of timing of ECV for breech pregnancies. BJOG. 2011;118(5):564.

Hutton EK, Hofmeyr GJ, Dowswell T. External cephalic version for breech presentation before term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7:CD000084.

Hutton EK, Kaufman K, Hodnett E, Amankwah K, Hewson SA, McKay D, Szalai JP, Hannah ME. External cephalic version beginning at 34 weeks' gestation versus 37 weeks' gestation: a randomized multicenter trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(1):245.

Nassar N, Roberts CL, Raynes-Greenow CH, Barratt A, Peat B. Decision aid for breech presentation trial collaborators evaluation of a decision aid for women with breech presentation at term: a randomised controlled trial [ISRCTN14570598]. BJOG. 2007;114(3):325.

Cluver C, Gyte GM, Sinclair M, Dowswell T, Hofmeyr GJ. Interventions for helping to turn term breech babies to head first presentation when using external cephalic version. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Feb;2:CD000184.

Rosman AN, Vlemmix F, Fleuren MA, Rijnders ME, Beuckens A, Opmeer BC, Mol BW, van Zwieten MC, Kok M. Patients' and professionals' barriers and facilitators to external cephalic version for breech presentation at term, a qualitative analysis in the Netherlands. Midwifery. 2014;30(3):324.

Hofmeyr GJ. Sonnendecker EW Cardiotocographic changes after external cephalic version. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1983;90(10):914.

Menakaya UA, Trivedi A. Qualitative assessment of women experiences with ECV. Women Birth. 2013;26(1):41–4.

ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice ACOG Committee Opinion No. 340. Mode of term singleton breech delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108 (1):235.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologist (RCOG). The management of breech presentation. London: RCOG; 2006.

Westgren M, Edvall H, Nordström L, Svalenius E, Ranstam J. Spontaneous cephalic version of breech presentation in the last trimester. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1985;92(1):19.

Coyle ME, Smith CA, Peat B. Cephalic version by moxibustion for breech presentation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD003928.

Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R. Cephalic version by postural management for breech presentation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD000051.

Glezerman M. Five years to the term breech trial: the rise and fall of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(1):20.

Menticoglou SM. Why vaginal breech delivery should still be offered. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2006;28(5):380.

Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, Hodnett ED, Saigal S, Willan AR. Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet. 2000;356(9239):1375.

Vlemmix F, Bergenhenegouwen L, Schaaf JM, Ensing S, Rosman AN, Ravelli AC, Van Der Post JA, Verhoeven A, Visser GH, Mol BW, Kok M. Term breech deliveries in the Netherlands: did the increased caesarean rate affect neonatal outcome? A population-based cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93(9):888.

Whyte H, Hannah ME, Saigal S, Hannah WJ, Hewson S, Amankwah K, Cheng M, Gafni A, Guselle P, Helewa M, Hodnett ED, Hutton E, Kung R, McKay D, Ross S, Willan A, Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Outcomes of children at 2 years after planned cesarean birth versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: The International Randomized Term Breech Trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(3):864–71.

Adegbola O, Akindele OM. Outcome of term singleton breech deliveries at a University Teaching Hospital in Lagos. Nigeria Niger Postgrad Med J. 2009;16(2):154–7.

Hartnack Tharin JE, Rasmussen S, Krebs L. Consequences of the term breech trial in Denmark. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90(7):767.

Vistad I, Klungsøyr K, Albrechtsen S, Skjeldestad FE. Neonatal outcome of singleton term breech deliveries in Norway from 1991 to 2011. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(9):997.

Lyons J, Pressey T, Bartholomew S, Liu S, Liston RM, Joseph KS. Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System (Public Health Agency of Canada) Delivery of breech presentation at term gestation in Canada, 2003-2011. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1153.

Goffinet F, Carayol M, Foidart JM, Alexander S, Uzan S, Subtil D, Bréart G, PREMODA Study Group. Is planned vaginal delivery for breech presentation at term still an option? Results of an observational prospective survey in France and Belgium. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(4):1002.

Kotaska A, Menticoglou S, Gagnon R, Farine D, Basso M, Bos H, Delisle MF, Grabowska K, Hudon L, Mundle W, Murphy-Kaulbeck L, Ouellet A, Pressey T, Roggensack A. Maternal Fetal Medicine Committee, Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. Vaginal delivery of breech presentation. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009;31 (6):557.

Goffinet F, Blondel B, Breart G. Breech presentation: questions raised by the controlled trial by Hannah et al. on systematic use of caesarean section for breech presentations. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod. 2001;30:187–90.

CAS Google Scholar

Glezerman M. Five years to the term breech trial: the risk and fall of a randomised controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:20–5.

Hauth JC, Cunningham FG. Vaginal breech delivery is still justified. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:1115–6.

Hull AD, Moore TR. Multiple repeat caesareans and the threat of placenta accreta: incidence, diagnosis, management. Clin Perinatol. 2011;38(2):285.

Moore WT, Steptoe PP. The experience of the John Hopkins hospital with breech presentation: an analysis of 1444 cases. South Med J. 1943;36:295.

Piper EB, Bachman C. The prevention of fetal injuries in breech delivery. J Am Med Assoc. 1929;92:217–21.

DeLee JB. Year book of obstetrics and gynaecology. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers; 1939.

Azria E, Le Meaux JP, Khoshnood B, Alexander S, Subtil D, Goffinet F. PREMODA Study Group Factors associated with adverse perinatal outcomes for term breech fetuses with planned vaginal delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(4):285.e1–9. Epub 2012 Aug 17

Alarab M, Regan C, O'Connell MP, Keane DP, O'Herlihy C, Foley ME. Singleton vaginal breech delivery at term: still a safe option. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(3):407.

Hofmeyr GJ, Lockwood CJ, Barss VA. Delivery of the fetus in breech presentation. Uptodate.com 2016 Topic 5384 version 18.

De Hundt M, Vlemmix F, Bais JM, Hutton EK, de Groot CJ, Mol BW, Kok M. Risk factors for developmental dysplasia of the hip: a meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;165(1):8.

Kenfack B, Ateudjieu J, Ymele FF, et al. Does the advice to Assumethe knee-chest position at the 36th to 37th weeks of gestation reduce the incidence of breech presentation at delivery? Clin Mother Child Health. 2012;9:1–5.

Dobbit JS, Foumane P, Tochie JN, Mamoudou F, Mazou N, Temgoua MN, Tankeu R, Aletum V, Mboudou E. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of vaginal breech delivery for singleton term pregnancies in a carefully selected Cameroonian population: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e017198.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

JUNIC Specialist Imaging and Women’s Centre, Coombs, ACT, Australia

Uche A. Menakaya

Calvary Public Hospital, Bruce, ACT, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Uche A. Menakaya .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Centre of Excellence in Reproductive Health Innovation, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Benin, Benin City, Nigeria

Friday Okonofua

College of Health Sciences, Chicago State University, Chicago, IL, USA

Joseph A. Balogun

Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY, USA

Kunle Odunsi

Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Weil Cornell Medicine, Doha, Qatar

Victor N. Chilaka

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Menakaya, U.A. (2021). Breech Presentation and Delivery. In: Okonofua, F., Balogun, J.A., Odunsi, K., Chilaka, V.N. (eds) Contemporary Obstetrics and Gynecology for Developing Countries . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75385-6_17

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75385-6_17

Published : 06 August 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-75384-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-75385-6

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

- MEDICAL ASSISSTANT

- Abdominal Key

- Anesthesia Key

- Basicmedical Key

- Otolaryngology & Ophthalmology

- Musculoskeletal Key

- Obstetric, Gynecology and Pediatric

- Oncology & Hematology

- Plastic Surgery & Dermatology

- Clinical Dentistry

- Radiology Key

- Thoracic Key

- Veterinary Medicine

- Gold Membership

Labor and Birth