- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- The PRISMA 2020...

The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews

PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews

- Related content

- Peer review

- Matthew J Page , senior research fellow 1 ,

- Joanne E McKenzie , associate professor 1 ,

- Patrick M Bossuyt , professor 2 ,

- Isabelle Boutron , professor 3 ,

- Tammy C Hoffmann , professor 4 ,

- Cynthia D Mulrow , professor 5 ,

- Larissa Shamseer , doctoral student 6 ,

- Jennifer M Tetzlaff , research product specialist 7 ,

- Elie A Akl , professor 8 ,

- Sue E Brennan , senior research fellow 1 ,

- Roger Chou , professor 9 ,

- Julie Glanville , associate director 10 ,

- Jeremy M Grimshaw , professor 11 ,

- Asbjørn Hróbjartsson , professor 12 ,

- Manoj M Lalu , associate scientist and assistant professor 13 ,

- Tianjing Li , associate professor 14 ,

- Elizabeth W Loder , professor 15 ,

- Evan Mayo-Wilson , associate professor 16 ,

- Steve McDonald , senior research fellow 1 ,

- Luke A McGuinness , research associate 17 ,

- Lesley A Stewart , professor and director 18 ,

- James Thomas , professor 19 ,

- Andrea C Tricco , scientist and associate professor 20 ,

- Vivian A Welch , associate professor 21 ,

- Penny Whiting , associate professor 17 ,

- David Moher , director and professor 22

- 1 School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

- 2 Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Amsterdam University Medical Centres, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 3 Université de Paris, Centre of Epidemiology and Statistics (CRESS), Inserm, F 75004 Paris, France

- 4 Institute for Evidence-Based Healthcare, Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, Bond University, Gold Coast, Australia

- 5 University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas, USA; Annals of Internal Medicine

- 6 Knowledge Translation Program, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, Toronto, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

- 7 Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada

- 8 Clinical Research Institute, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon; Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

- 9 Department of Medical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon, USA

- 10 York Health Economics Consortium (YHEC Ltd), University of York, York, UK

- 11 Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada; Department of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

- 12 Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Odense (CEBMO) and Cochrane Denmark, Department of Clinical Research, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark; Open Patient data Exploratory Network (OPEN), Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark

- 13 Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Canada; Clinical Epidemiology Program, Blueprint Translational Research Group, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada; Regenerative Medicine Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada

- 14 Department of Ophthalmology, School of Medicine, University of Colorado Denver, Denver, Colorado, United States; Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

- 15 Division of Headache, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Head of Research, The BMJ , London, UK

- 16 Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Indiana University School of Public Health-Bloomington, Bloomington, Indiana, USA

- 17 Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

- 18 Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, York, UK

- 19 EPPI-Centre, UCL Social Research Institute, University College London, London, UK

- 20 Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael's Hospital, Unity Health Toronto, Toronto, Canada; Epidemiology Division of the Dalla Lana School of Public Health and the Institute of Health Management, Policy, and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; Queen's Collaboration for Health Care Quality Joanna Briggs Institute Centre of Excellence, Queen's University, Kingston, Canada

- 21 Methods Centre, Bruyère Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

- 22 Centre for Journalology, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

- Correspondence to: M J Page matthew.page{at}monash.edu

- Accepted 4 January 2021

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement, published in 2009, was designed to help systematic reviewers transparently report why the review was done, what the authors did, and what they found. Over the past decade, advances in systematic review methodology and terminology have necessitated an update to the guideline. The PRISMA 2020 statement replaces the 2009 statement and includes new reporting guidance that reflects advances in methods to identify, select, appraise, and synthesise studies. The structure and presentation of the items have been modified to facilitate implementation. In this article, we present the PRISMA 2020 27-item checklist, an expanded checklist that details reporting recommendations for each item, the PRISMA 2020 abstract checklist, and the revised flow diagrams for original and updated reviews.

Systematic reviews serve many critical roles. They can provide syntheses of the state of knowledge in a field, from which future research priorities can be identified; they can address questions that otherwise could not be answered by individual studies; they can identify problems in primary research that should be rectified in future studies; and they can generate or evaluate theories about how or why phenomena occur. Systematic reviews therefore generate various types of knowledge for different users of reviews (such as patients, healthcare providers, researchers, and policy makers). 1 2 To ensure a systematic review is valuable to users, authors should prepare a transparent, complete, and accurate account of why the review was done, what they did (such as how studies were identified and selected) and what they found (such as characteristics of contributing studies and results of meta-analyses). Up-to-date reporting guidance facilitates authors achieving this. 3

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement published in 2009 (hereafter referred to as PRISMA 2009) 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 is a reporting guideline designed to address poor reporting of systematic reviews. 11 The PRISMA 2009 statement comprised a checklist of 27 items recommended for reporting in systematic reviews and an “explanation and elaboration” paper 12 13 14 15 16 providing additional reporting guidance for each item, along with exemplars of reporting. The recommendations have been widely endorsed and adopted, as evidenced by its co-publication in multiple journals, citation in over 60 000 reports (Scopus, August 2020), endorsement from almost 200 journals and systematic review organisations, and adoption in various disciplines. Evidence from observational studies suggests that use of the PRISMA 2009 statement is associated with more complete reporting of systematic reviews, 17 18 19 20 although more could be done to improve adherence to the guideline. 21

Many innovations in the conduct of systematic reviews have occurred since publication of the PRISMA 2009 statement. For example, technological advances have enabled the use of natural language processing and machine learning to identify relevant evidence, 22 23 24 methods have been proposed to synthesise and present findings when meta-analysis is not possible or appropriate, 25 26 27 and new methods have been developed to assess the risk of bias in results of included studies. 28 29 Evidence on sources of bias in systematic reviews has accrued, culminating in the development of new tools to appraise the conduct of systematic reviews. 30 31 Terminology used to describe particular review processes has also evolved, as in the shift from assessing “quality” to assessing “certainty” in the body of evidence. 32 In addition, the publishing landscape has transformed, with multiple avenues now available for registering and disseminating systematic review protocols, 33 34 disseminating reports of systematic reviews, and sharing data and materials, such as preprint servers and publicly accessible repositories. To capture these advances in the reporting of systematic reviews necessitated an update to the PRISMA 2009 statement.

Summary points

To ensure a systematic review is valuable to users, authors should prepare a transparent, complete, and accurate account of why the review was done, what they did, and what they found

The PRISMA 2020 statement provides updated reporting guidance for systematic reviews that reflects advances in methods to identify, select, appraise, and synthesise studies

The PRISMA 2020 statement consists of a 27-item checklist, an expanded checklist that details reporting recommendations for each item, the PRISMA 2020 abstract checklist, and revised flow diagrams for original and updated reviews

We anticipate that the PRISMA 2020 statement will benefit authors, editors, and peer reviewers of systematic reviews, and different users of reviews, including guideline developers, policy makers, healthcare providers, patients, and other stakeholders

Development of PRISMA 2020

A complete description of the methods used to develop PRISMA 2020 is available elsewhere. 35 We identified PRISMA 2009 items that were often reported incompletely by examining the results of studies investigating the transparency of reporting of published reviews. 17 21 36 37 We identified possible modifications to the PRISMA 2009 statement by reviewing 60 documents providing reporting guidance for systematic reviews (including reporting guidelines, handbooks, tools, and meta-research studies). 38 These reviews of the literature were used to inform the content of a survey with suggested possible modifications to the 27 items in PRISMA 2009 and possible additional items. Respondents were asked whether they believed we should keep each PRISMA 2009 item as is, modify it, or remove it, and whether we should add each additional item. Systematic review methodologists and journal editors were invited to complete the online survey (110 of 220 invited responded). We discussed proposed content and wording of the PRISMA 2020 statement, as informed by the review and survey results, at a 21-member, two-day, in-person meeting in September 2018 in Edinburgh, Scotland. Throughout 2019 and 2020, we circulated an initial draft and five revisions of the checklist and explanation and elaboration paper to co-authors for feedback. In April 2020, we invited 22 systematic reviewers who had expressed interest in providing feedback on the PRISMA 2020 checklist to share their views (via an online survey) on the layout and terminology used in a preliminary version of the checklist. Feedback was received from 15 individuals and considered by the first author, and any revisions deemed necessary were incorporated before the final version was approved and endorsed by all co-authors.

The PRISMA 2020 statement

Scope of the guideline.

The PRISMA 2020 statement has been designed primarily for systematic reviews of studies that evaluate the effects of health interventions, irrespective of the design of the included studies. However, the checklist items are applicable to reports of systematic reviews evaluating other interventions (such as social or educational interventions), and many items are applicable to systematic reviews with objectives other than evaluating interventions (such as evaluating aetiology, prevalence, or prognosis). PRISMA 2020 is intended for use in systematic reviews that include synthesis (such as pairwise meta-analysis or other statistical synthesis methods) or do not include synthesis (for example, because only one eligible study is identified). The PRISMA 2020 items are relevant for mixed-methods systematic reviews (which include quantitative and qualitative studies), but reporting guidelines addressing the presentation and synthesis of qualitative data should also be consulted. 39 40 PRISMA 2020 can be used for original systematic reviews, updated systematic reviews, or continually updated (“living”) systematic reviews. However, for updated and living systematic reviews, there may be some additional considerations that need to be addressed. Where there is relevant content from other reporting guidelines, we reference these guidelines within the items in the explanation and elaboration paper 41 (such as PRISMA-Search 42 in items 6 and 7, Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) reporting guideline 27 in item 13d). Box 1 includes a glossary of terms used throughout the PRISMA 2020 statement.

Glossary of terms

Systematic review —A review that uses explicit, systematic methods to collate and synthesise findings of studies that address a clearly formulated question 43

Statistical synthesis —The combination of quantitative results of two or more studies. This encompasses meta-analysis of effect estimates (described below) and other methods, such as combining P values, calculating the range and distribution of observed effects, and vote counting based on the direction of effect (see McKenzie and Brennan 25 for a description of each method)

Meta-analysis of effect estimates —A statistical technique used to synthesise results when study effect estimates and their variances are available, yielding a quantitative summary of results 25

Outcome —An event or measurement collected for participants in a study (such as quality of life, mortality)

Result —The combination of a point estimate (such as a mean difference, risk ratio, or proportion) and a measure of its precision (such as a confidence/credible interval) for a particular outcome

Report —A document (paper or electronic) supplying information about a particular study. It could be a journal article, preprint, conference abstract, study register entry, clinical study report, dissertation, unpublished manuscript, government report, or any other document providing relevant information

Record —The title or abstract (or both) of a report indexed in a database or website (such as a title or abstract for an article indexed in Medline). Records that refer to the same report (such as the same journal article) are “duplicates”; however, records that refer to reports that are merely similar (such as a similar abstract submitted to two different conferences) should be considered unique.

Study —An investigation, such as a clinical trial, that includes a defined group of participants and one or more interventions and outcomes. A “study” might have multiple reports. For example, reports could include the protocol, statistical analysis plan, baseline characteristics, results for the primary outcome, results for harms, results for secondary outcomes, and results for additional mediator and moderator analyses

PRISMA 2020 is not intended to guide systematic review conduct, for which comprehensive resources are available. 43 44 45 46 However, familiarity with PRISMA 2020 is useful when planning and conducting systematic reviews to ensure that all recommended information is captured. PRISMA 2020 should not be used to assess the conduct or methodological quality of systematic reviews; other tools exist for this purpose. 30 31 Furthermore, PRISMA 2020 is not intended to inform the reporting of systematic review protocols, for which a separate statement is available (PRISMA for Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement 47 48 ). Finally, extensions to the PRISMA 2009 statement have been developed to guide reporting of network meta-analyses, 49 meta-analyses of individual participant data, 50 systematic reviews of harms, 51 systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy studies, 52 and scoping reviews 53 ; for these types of reviews we recommend authors report their review in accordance with the recommendations in PRISMA 2020 along with the guidance specific to the extension.

How to use PRISMA 2020

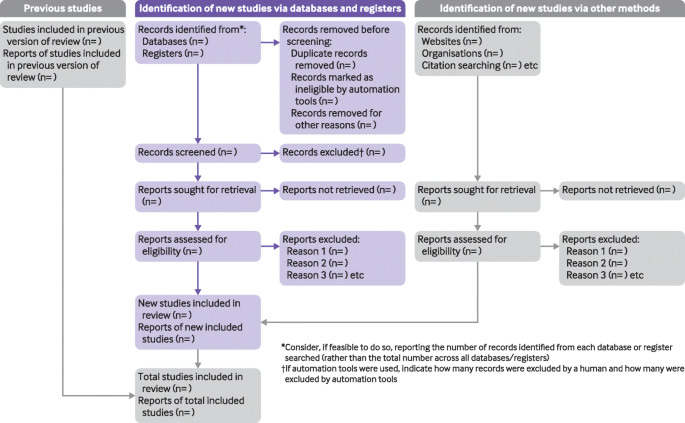

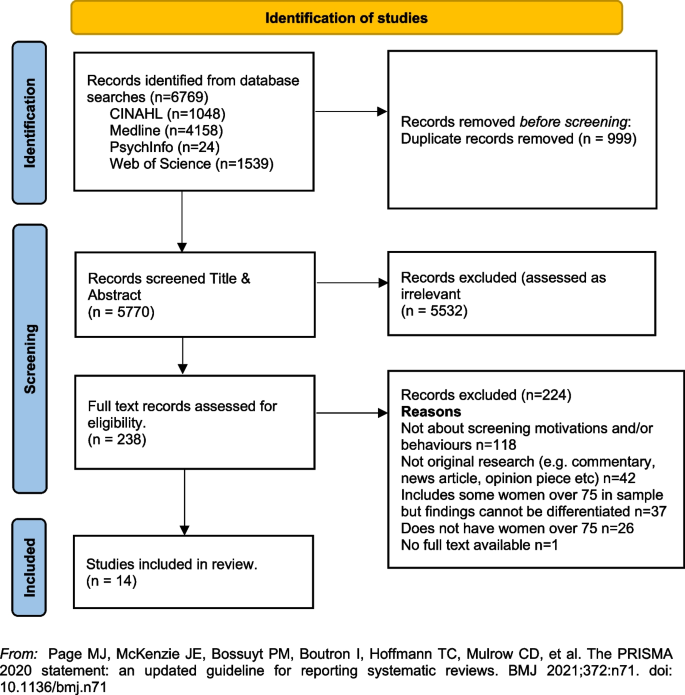

The PRISMA 2020 statement (including the checklists, explanation and elaboration, and flow diagram) replaces the PRISMA 2009 statement, which should no longer be used. Box 2 summarises noteworthy changes from the PRISMA 2009 statement. The PRISMA 2020 checklist includes seven sections with 27 items, some of which include sub-items ( table 1 ). A checklist for journal and conference abstracts for systematic reviews is included in PRISMA 2020. This abstract checklist is an update of the 2013 PRISMA for Abstracts statement, 54 reflecting new and modified content in PRISMA 2020 ( table 2 ). A template PRISMA flow diagram is provided, which can be modified depending on whether the systematic review is original or updated ( fig 1 ).

Noteworthy changes to the PRISMA 2009 statement

Inclusion of the abstract reporting checklist within PRISMA 2020 (see item #2 and table 2 ).

Movement of the ‘Protocol and registration’ item from the start of the Methods section of the checklist to a new Other section, with addition of a sub-item recommending authors describe amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol (see item #24a-24c).

Modification of the ‘Search’ item to recommend authors present full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites searched, not just at least one database (see item #7).

Modification of the ‘Study selection’ item in the Methods section to emphasise the reporting of how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process (see item #8).

Addition of a sub-item to the ‘Data items’ item recommending authors report how outcomes were defined, which results were sought, and methods for selecting a subset of results from included studies (see item #10a).

Splitting of the ‘Synthesis of results’ item in the Methods section into six sub-items recommending authors describe: the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis; any methods required to prepare the data for synthesis; any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses; any methods used to synthesise results; any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (such as subgroup analysis, meta-regression); and any sensitivity analyses used to assess robustness of the synthesised results (see item #13a-13f).

Addition of a sub-item to the ‘Study selection’ item in the Results section recommending authors cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded (see item #16b).

Splitting of the ‘Synthesis of results’ item in the Results section into four sub-items recommending authors: briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among studies contributing to the synthesis; present results of all statistical syntheses conducted; present results of any investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results; and present results of any sensitivity analyses (see item #20a-20d).

Addition of new items recommending authors report methods for and results of an assessment of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome (see items #15 and #22).

Addition of a new item recommending authors declare any competing interests (see item #26).

Addition of a new item recommending authors indicate whether data, analytic code and other materials used in the review are publicly available and if so, where they can be found (see item #27).

PRISMA 2020 item checklist

- View inline

PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist*

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram template for systematic reviews. The new design is adapted from flow diagrams proposed by Boers, 55 Mayo-Wilson et al. 56 and Stovold et al. 57 The boxes in grey should only be completed if applicable; otherwise they should be removed from the flow diagram. Note that a “report” could be a journal article, preprint, conference abstract, study register entry, clinical study report, dissertation, unpublished manuscript, government report or any other document providing relevant information.

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

We recommend authors refer to PRISMA 2020 early in the writing process, because prospective consideration of the items may help to ensure that all the items are addressed. To help keep track of which items have been reported, the PRISMA statement website ( http://www.prisma-statement.org/ ) includes fillable templates of the checklists to download and complete (also available in the data supplement on bmj.com). We have also created a web application that allows users to complete the checklist via a user-friendly interface 58 (available at https://prisma.shinyapps.io/checklist/ and adapted from the Transparency Checklist app 59 ). The completed checklist can be exported to Word or PDF. Editable templates of the flow diagram can also be downloaded from the PRISMA statement website.

We have prepared an updated explanation and elaboration paper, in which we explain why reporting of each item is recommended and present bullet points that detail the reporting recommendations (which we refer to as elements). 41 The bullet-point structure is new to PRISMA 2020 and has been adopted to facilitate implementation of the guidance. 60 61 An expanded checklist, which comprises an abridged version of the elements presented in the explanation and elaboration paper, with references and some examples removed, is available in the data supplement on bmj.com. Consulting the explanation and elaboration paper is recommended if further clarity or information is required.

Journals and publishers might impose word and section limits, and limits on the number of tables and figures allowed in the main report. In such cases, if the relevant information for some items already appears in a publicly accessible review protocol, referring to the protocol may suffice. Alternatively, placing detailed descriptions of the methods used or additional results (such as for less critical outcomes) in supplementary files is recommended. Ideally, supplementary files should be deposited to a general-purpose or institutional open-access repository that provides free and permanent access to the material (such as Open Science Framework, Dryad, figshare). A reference or link to the additional information should be included in the main report. Finally, although PRISMA 2020 provides a template for where information might be located, the suggested location should not be seen as prescriptive; the guiding principle is to ensure the information is reported.

Use of PRISMA 2020 has the potential to benefit many stakeholders. Complete reporting allows readers to assess the appropriateness of the methods, and therefore the trustworthiness of the findings. Presenting and summarising characteristics of studies contributing to a synthesis allows healthcare providers and policy makers to evaluate the applicability of the findings to their setting. Describing the certainty in the body of evidence for an outcome and the implications of findings should help policy makers, managers, and other decision makers formulate appropriate recommendations for practice or policy. Complete reporting of all PRISMA 2020 items also facilitates replication and review updates, as well as inclusion of systematic reviews in overviews (of systematic reviews) and guidelines, so teams can leverage work that is already done and decrease research waste. 36 62 63

We updated the PRISMA 2009 statement by adapting the EQUATOR Network’s guidance for developing health research reporting guidelines. 64 We evaluated the reporting completeness of published systematic reviews, 17 21 36 37 reviewed the items included in other documents providing guidance for systematic reviews, 38 surveyed systematic review methodologists and journal editors for their views on how to revise the original PRISMA statement, 35 discussed the findings at an in-person meeting, and prepared this document through an iterative process. Our recommendations are informed by the reviews and survey conducted before the in-person meeting, theoretical considerations about which items facilitate replication and help users assess the risk of bias and applicability of systematic reviews, and co-authors’ experience with authoring and using systematic reviews.

Various strategies to increase the use of reporting guidelines and improve reporting have been proposed. They include educators introducing reporting guidelines into graduate curricula to promote good reporting habits of early career scientists 65 ; journal editors and regulators endorsing use of reporting guidelines 18 ; peer reviewers evaluating adherence to reporting guidelines 61 66 ; journals requiring authors to indicate where in their manuscript they have adhered to each reporting item 67 ; and authors using online writing tools that prompt complete reporting at the writing stage. 60 Multi-pronged interventions, where more than one of these strategies are combined, may be more effective (such as completion of checklists coupled with editorial checks). 68 However, of 31 interventions proposed to increase adherence to reporting guidelines, the effects of only 11 have been evaluated, mostly in observational studies at high risk of bias due to confounding. 69 It is therefore unclear which strategies should be used. Future research might explore barriers and facilitators to the use of PRISMA 2020 by authors, editors, and peer reviewers, designing interventions that address the identified barriers, and evaluating those interventions using randomised trials. To inform possible revisions to the guideline, it would also be valuable to conduct think-aloud studies 70 to understand how systematic reviewers interpret the items, and reliability studies to identify items where there is varied interpretation of the items.

We encourage readers to submit evidence that informs any of the recommendations in PRISMA 2020 (via the PRISMA statement website: http://www.prisma-statement.org/ ). To enhance accessibility of PRISMA 2020, several translations of the guideline are under way (see available translations at the PRISMA statement website). We encourage journal editors and publishers to raise awareness of PRISMA 2020 (for example, by referring to it in journal “Instructions to authors”), endorsing its use, advising editors and peer reviewers to evaluate submitted systematic reviews against the PRISMA 2020 checklists, and making changes to journal policies to accommodate the new reporting recommendations. We recommend existing PRISMA extensions 47 49 50 51 52 53 71 72 be updated to reflect PRISMA 2020 and advise developers of new PRISMA extensions to use PRISMA 2020 as the foundation document.

We anticipate that the PRISMA 2020 statement will benefit authors, editors, and peer reviewers of systematic reviews, and different users of reviews, including guideline developers, policy makers, healthcare providers, patients, and other stakeholders. Ultimately, we hope that uptake of the guideline will lead to more transparent, complete, and accurate reporting of systematic reviews, thus facilitating evidence based decision making.

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this paper to the late Douglas G Altman and Alessandro Liberati, whose contributions were fundamental to the development and implementation of the original PRISMA statement.

We thank the following contributors who completed the survey to inform discussions at the development meeting: Xavier Armoiry, Edoardo Aromataris, Ana Patricia Ayala, Ethan M Balk, Virginia Barbour, Elaine Beller, Jesse A Berlin, Lisa Bero, Zhao-Xiang Bian, Jean Joel Bigna, Ferrán Catalá-López, Anna Chaimani, Mike Clarke, Tammy Clifford, Ioana A Cristea, Miranda Cumpston, Sofia Dias, Corinna Dressler, Ivan D Florez, Joel J Gagnier, Chantelle Garritty, Long Ge, Davina Ghersi, Sean Grant, Gordon Guyatt, Neal R Haddaway, Julian PT Higgins, Sally Hopewell, Brian Hutton, Jamie J Kirkham, Jos Kleijnen, Julia Koricheva, Joey SW Kwong, Toby J Lasserson, Julia H Littell, Yoon K Loke, Malcolm R Macleod, Chris G Maher, Ana Marušic, Dimitris Mavridis, Jessie McGowan, Matthew DF McInnes, Philippa Middleton, Karel G Moons, Zachary Munn, Jane Noyes, Barbara Nußbaumer-Streit, Donald L Patrick, Tatiana Pereira-Cenci, Ba’ Pham, Bob Phillips, Dawid Pieper, Michelle Pollock, Daniel S Quintana, Drummond Rennie, Melissa L Rethlefsen, Hannah R Rothstein, Maroeska M Rovers, Rebecca Ryan, Georgia Salanti, Ian J Saldanha, Margaret Sampson, Nancy Santesso, Rafael Sarkis-Onofre, Jelena Savović, Christopher H Schmid, Kenneth F Schulz, Guido Schwarzer, Beverley J Shea, Paul G Shekelle, Farhad Shokraneh, Mark Simmonds, Nicole Skoetz, Sharon E Straus, Anneliese Synnot, Emily E Tanner-Smith, Brett D Thombs, Hilary Thomson, Alexander Tsertsvadze, Peter Tugwell, Tari Turner, Lesley Uttley, Jeffrey C Valentine, Matt Vassar, Areti Angeliki Veroniki, Meera Viswanathan, Cole Wayant, Paul Whaley, and Kehu Yang. We thank the following contributors who provided feedback on a preliminary version of the PRISMA 2020 checklist: Jo Abbott, Fionn Büttner, Patricia Correia-Santos, Victoria Freeman, Emily A Hennessy, Rakibul Islam, Amalia (Emily) Karahalios, Kasper Krommes, Andreas Lundh, Dafne Port Nascimento, Davina Robson, Catherine Schenck-Yglesias, Mary M Scott, Sarah Tanveer and Pavel Zhelnov. We thank Abigail H Goben, Melissa L Rethlefsen, Tanja Rombey, Anna Scott, and Farhad Shokraneh for their helpful comments on the preprints of the PRISMA 2020 papers. We thank Edoardo Aromataris, Stephanie Chang, Toby Lasserson and David Schriger for their helpful peer review comments on the PRISMA 2020 papers.

Contributors: JEM and DM are joint senior authors. MJP, JEM, PMB, IB, TCH, CDM, LS, and DM conceived this paper and designed the literature review and survey conducted to inform the guideline content. MJP conducted the literature review, administered the survey and analysed the data for both. MJP prepared all materials for the development meeting. MJP and JEM presented proposals at the development meeting. All authors except for TCH, JMT, EAA, SEB, and LAM attended the development meeting. MJP and JEM took and consolidated notes from the development meeting. MJP and JEM led the drafting and editing of the article. JEM, PMB, IB, TCH, LS, JMT, EAA, SEB, RC, JG, AH, TL, EMW, SM, LAM, LAS, JT, ACT, PW, and DM drafted particular sections of the article. All authors were involved in revising the article critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the article. MJP is the guarantor of this work. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: There was no direct funding for this research. MJP is supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE200101618) and was previously supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Early Career Fellowship (1088535) during the conduct of this research. JEM is supported by an Australian NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (1143429). TCH is supported by an Australian NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (1154607). JMT is supported by Evidence Partners Inc. JMG is supported by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Health Knowledge Transfer and Uptake. MML is supported by The Ottawa Hospital Anaesthesia Alternate Funds Association and a Faculty of Medicine Junior Research Chair. TL is supported by funding from the National Eye Institute (UG1EY020522), National Institutes of Health, United States. LAM is supported by a National Institute for Health Research Doctoral Research Fellowship (DRF-2018-11-ST2-048). ACT is supported by a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Synthesis. DM is supported in part by a University Research Chair, University of Ottawa. The funders had no role in considering the study design or in the collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/conflicts-of-interest/ and declare: EL is head of research for the BMJ ; MJP is an editorial board member for PLOS Medicine ; ACT is an associate editor and MJP, TL, EMW, and DM are editorial board members for the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology ; DM and LAS were editors in chief, LS, JMT, and ACT are associate editors, and JG is an editorial board member for Systematic Reviews . None of these authors were involved in the peer review process or decision to publish. TCH has received personal fees from Elsevier outside the submitted work. EMW has received personal fees from the American Journal for Public Health , for which he is the editor for systematic reviews. VW is editor in chief of the Campbell Collaboration, which produces systematic reviews, and co-convenor of the Campbell and Cochrane equity methods group. DM is chair of the EQUATOR Network, IB is adjunct director of the French EQUATOR Centre and TCH is co-director of the Australasian EQUATOR Centre, which advocates for the use of reporting guidelines to improve the quality of reporting in research articles. JMT received salary from Evidence Partners, creator of DistillerSR software for systematic reviews; Evidence Partners was not involved in the design or outcomes of the statement, and the views expressed solely represent those of the author.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and the public were not involved in this methodological research. We plan to disseminate the research widely, including to community participants in evidence synthesis organisations.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

- Gurevitch J ,

- Koricheva J ,

- Nakagawa S ,

- Liberati A ,

- Tetzlaff J ,

- Altman DG ,

- PRISMA Group

- Tricco AC ,

- Sampson M ,

- Shamseer L ,

- Leoncini E ,

- de Belvis G ,

- Ricciardi W ,

- Fowler AJ ,

- Leclercq V ,

- Beaudart C ,

- Ajamieh S ,

- Rabenda V ,

- Tirelli E ,

- O’Mara-Eves A ,

- McNaught J ,

- Ananiadou S

- Marshall IJ ,

- Noel-Storr A ,

- Higgins JPT ,

- Chandler J ,

- McKenzie JE ,

- López-López JA ,

- Becker BJ ,

- Campbell M ,

- Sterne JAC ,

- Savović J ,

- Sterne JA ,

- Hernán MA ,

- Reeves BC ,

- Whiting P ,

- Higgins JP ,

- ROBIS group

- Hultcrantz M ,

- Stewart L ,

- Bossuyt PM ,

- Flemming K ,

- McInnes E ,

- France EF ,

- Cunningham M ,

- Rethlefsen ML ,

- Kirtley S ,

- Waffenschmidt S ,

- PRISMA-S Group

- ↵ Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions : Version 6.0. Cochrane, 2019. Available from https://training.cochrane.org/handbook .

- Dekkers OM ,

- Vandenbroucke JP ,

- Cevallos M ,

- Renehan AG ,

- ↵ Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JV, eds. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis. Russell Sage Foundation, 2019.

- IOM (Institute of Medicine)

- PRISMA-P Group

- Salanti G ,

- Caldwell DM ,

- Stewart LA ,

- PRISMA-IPD Development Group

- Zorzela L ,

- Ioannidis JP ,

- PRISMAHarms Group

- McInnes MDF ,

- Thombs BD ,

- and the PRISMA-DTA Group

- Beller EM ,

- Glasziou PP ,

- PRISMA for Abstracts Group

- Mayo-Wilson E ,

- Dickersin K ,

- MUDS investigators

- Stovold E ,

- Beecher D ,

- Noel-Storr A

- McGuinness LA

- Sarafoglou A ,

- Boutron I ,

- Giraudeau B ,

- Porcher R ,

- Chauvin A ,

- Schulz KF ,

- Schroter S ,

- Stevens A ,

- Weinstein E ,

- Macleod MR ,

- IICARus Collaboration

- Kirkham JJ ,

- Petticrew M ,

- Tugwell P ,

- PRISMA-Equity Bellagio group

Reporting Standards for Literature Reviews

- First Online: 11 August 2022

Cite this chapter

- Rob Dekkers 4 ,

- Lindsey Carey 5 &

- Peter Langhorne 6

1636 Accesses

Previous chapters have already referred to reporting of literature reviews. Cases in point are Section 3.5 about evidencing engagement with consulted studies, the assessment of the quality of evidence in Sections 6.4 and 6.5 , and combining quantitative and qualitative syntheses in Section 12.4 . Considering how to report results, conjectures, findings, conclusions and recommendations is an important aspect of conducting a literature review; this applies to literature reviews for empirical studies as well as stand-alone literature reviews. Depending on the purpose of the literature review, the audience may consist of scholars, researchers, practitioners, policymakers and citizens, or even examiners, for example in the case of doctoral theses. Such broad variety of readers also requires paying attention to reporting, presenting of the literature review and making it accessible to intended readers, which includes writing (for the latter, see Sections 15.6 and 15.7 ).

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Systematic Process for Investigating and Describing Evidence-based Research.

For a further elaboration of these and related arguments, see Section 17.2 .

Bem DJ (1995) Writing a review article for psychological bulletin. Psychol Bull 118(2):172–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.118.2.172

Article Google Scholar

Bin Ali N, Usman M (2019) A critical appraisal tool for systematic literature reviews in software engineering. Inform Softw Technol 112:48–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2019.04.006

Boote DN, Beile P (2005) Scholars before researchers: on the centrality of the dissertation literature review in research preparation. Educ Res 34(6):3–15. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x034006003

Boote DN, Beile P (2006) On “Literature reviews of, and for, educational research”: a response to the critique by Joseph Maxwell. Educ Res 35(9):32–35. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x035009032

Booth A (2006) “Brimful of STARLITE”: toward standards for reporting literature searches. J Med Libr Assoc 94(4):421-e205

Google Scholar

Booth A, Clarke M, Dooley G, Ghersi D, Moher D, Petticrew M, Stewart L (2012) The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: an international prospective register of systematic reviews. Systemat Rev 1(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-2

Brown P, Brunnhuber K, Chalkidou K, Chalmers I, Clarke M, Fenton M, Forbes C, Glanville J, Hicks NJ, Moody J, Twaddle S, Timimi H, Young P (2006) How to formulate research recommendations. BMJ 333(7572):804–806. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38987.492014.94

Budgen D, Brereton P, Drummond S, Williams N (2018) Reporting systematic reviews: some lessons from a tertiary study. Inf Softw Technol 95:62–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2017.10.017

Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, Katikireddi SV, Brennan SE, Ellis S, Hartmann-Boyce J, Ryan R, Shepperd S, Thomas J, Welch V, Thomson H (2020) Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ 368:l6890. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6890

Classen S, Winter S, Awadzi KD, Garvan CW, Lopez EDS, Sundaram S (2008) Psychometric testing of SPIDER: data capture tool for systematic literature reviews. Am J Occupat Therapy 62(3):335–348. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.62.3.335

Clemen RT (1989) Combining forecasts: areview and annotated bibliography. Int J Forecast 5(4):559–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-2070(89)90012-5

Dekkers R, Barlow A, Chaudhuri A, Saranga H (2020) Theory informing decision-making on outsourcing: a review of four ‘Five-Year’ snapshots spanning 47 years. University of Glasgow, Glasgow

Elamin MB, Flynn DN, Bassler D, Briel M, Alonso-Coello P, Karanicolas PJ, Guyatt GH, Malaga G, Furukawa TA, Kunz R, Schünemann H, Murad MH, Barbui C, Cipriani A, Montori VM (2009) Choice of data extraction tools for systematic reviews depends on resources and review complexity. J Clin Epidemiol 62(5):506–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.016

Felizardo KR, Salleh N, Martins RM, Mendes E, MacDonell SG, Maldonado JC (2011) Using visual text mining to support the study selection activity in systematic literature reviews. Paper presented at the International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement, Banff, AB, 22–23 September 2011

Ferrari R (2015) Writing narrative style literature reviews. Med Writ 24(4):230–235. https://doi.org/10.1179/2047480615Z.000000000329

Free C, Phillips G, Felix L, Galli L, Patel V, Edwards P (2010) The effectiveness of M-health technologies for improving health and health services: a systematic review protocol. BMC Res Notes 3(1):250. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-3-250

Garside R (2014) Should we appraise the quality of qualitative research reports for systematic reviews, and if so, how? Innov Eur J Soc Sci Res 27(1):67–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2013.777270

Goldman KD, Schmalz KJ (2004) The matrix method of literature reviews. Health Promot Pract 5(1):5–7

Grosso G, Godos J, Galvano F, Giovannucci EL (2017) Coffee, caffeine, and health outcomes: an umbrella review. Ann Rev Nutr 37(1):131–156. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nutr-071816-064941

Haddaway NR, Macura B (2018) The role of reporting standards in producing robust literature reviews. Nat Clim Chang 8(6):444–447. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0180-3

Haddaway NR, Macura B, Whaley P, Pullin AS (2018) ROSES reporting standards for systematic evidence syntheses: pro forma, flow-diagram and descriptive summary of the plan and conduct of environmental systematic reviews and systematic maps. Environ Evid 7(1):7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-018-0121-7

Houghton C, Murphy K, Meehan B, Thomas J, Brooker D, Casey D (2017) From screening to synthesis: using nvivo to enhance transparency in qualitative evidence synthesis. J Clin Nurs 26(5–6):873–881. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13443

Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, Chaimani A, Schmid CH, Cameron C, Ioannidis JPA, Straus S, Thorlund K, Jansen JP, Mulrow C, Catalá-López F, Gøtzsche PC, Dickersin K, Boutron I, Altman DG, Moher D (2015) The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Internal Med 162(11):777–784. PMID 26030634. https://doi.org/10.7326/m14-2385

Kohl C, McIntosh EJ, Unger S, Haddaway NR, Kecke S, Schiemann J, Wilhelm R (2018) Online tools supporting the conduct and reporting of systematic reviews and systematic maps: a case study on CADIMA and review of existing tools. Environ Evid 7(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-018-0115-5

Lawal AK, Rotter T, Kinsman L, Sari N, Harrison L, Jeffery C, Kutz M, Khan MF, Flynn R (2014) Lean management in health care: definition, concepts, methodology and effects reported (systematic review protocol). Systemat Rev 3(1):103. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-3-103

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 62(10):e1–e34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006

Macdonald S, Kam J, Aardvark et al (2007a) Quality journals and gamesmanship in management studies. J Inform Sci 33(6), 702–717. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551507077419

Macdonald S, Kam J (2007b) Ring a Ring o’ Roses: quality journals and gamesmanship in management studies. J Manag Stud 44(4):640–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00704.x

MacLure M (2005) ‘Clarity bordering on stupidity’: where’s the quality in systematic review? J Educ Policy 20(4):393–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930500131801

Maggio LA, Tannery NH, Kanter SL (2011) Reproducibility of literature search reporting in medical education reviews. Acad Med 86(8):1049–1054. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822221e7

Marangunić N, Granić A (2015) Technology acceptance model: a literature review from 1986 to 2013. Univ Access Inf Soc 14(1):81–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-014-0348-1

Maxwell JA (2006) Literature reviews of, and for, educational research: a commentary on Boote and Beile’s “Scholars before researchers.” Educ Res 35(9):28–31. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x035009028

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:b2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA & PRISMA-P Group (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systemat Rev 4(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

Moja LP, Telaro E, D’Amico R, Moschetti I, Coe L, Liberati A (2005) Assessment of methodological quality of primary studies by systematic reviews: results of the metaquality cross sectional study. BMJ 330(7499):1053. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38414.515938.8F

Newman MEJ (2003) The structure and function of complex networks. SIAM Rev 45(2):167–256. https://doi.org/10.1137/S003614450342480

Neyeloff JL, Fuchs SC, Moreira LB (2012) Meta-analyses and forest plots using a microsoft excel spreadsheet: step-by-step guide focusing on descriptive data analysis. BMC Res Notes 5(1):52. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-5-52

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA (2014) Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 89(9):1245–1251. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000388

O’Mara-Eves A, Thomas J, McNaught J, Miwa M, Ananiadou S (2015) Using text mining for study identification in systematic reviews: a systematic review of current approaches. Syst Rev 4(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-5

Olorisade BK, Brereton P, Andras P (2017) Reproducibility of studies on text mining for citation screening in systematic reviews: evaluation and checklist. J Biomed Inform 73:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2017.07.010

Otero-Cerdeira L, Rodríguez-Martínez FJ, Gómez-Rodríguez A (2015) Ontology matching: aliterature review. Expert Syst Appl 42(2):949–971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2014.08.032

Oxman AD, Guyatt GH (1988) Guidelines for reading literature reviews. Can Med Assoc J 138(8):697–703

Pati D, Lorusso LN (2018) How to write a systematic review of the literature. HERD: Health Environ Res Des J 11(1):15–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1937586717747384

Pidgeon TE, Wellstead G, Sagoo H, Jafree DJ, Fowler AJ, Agha RA (2016) An assessment of the compliance of systematic review articles published in craniofacial surgery with the PRISMA statement guidelines: a systematic review. J Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg 44(10):1522–1530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2016.07.018

Poole R, Kennedy OJ, Roderick P, Fallowfield JA, Hayes PC, Parkes J (2017) Coffee consumption and health: umbrella review of meta-analyses of multiple health outcomes. BMJ 359:j5024. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j5024

Pullin AS, Stewart GB (2006) Guidelines for systematic review in conservation and environmental management. Conserv Biol 20(6):1647–1656. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00485.x

Salgado EG, Dekkers R (2018) Lean product development: nothing new under the sun? Int J Manag Rev 20(4):903–933. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12169

Siddaway AP, Wood AM, Hedges LV (2019) How to do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Ann Rev Psychol 70(1):747–770. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

Silagy CA, Middleton P, Hopewell S (2002) Publishing protocols of systematic reviews comparing what was done to what was planned. JAMA 287(21):2831–2834. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.21.2831

Simera I, Altman DG, Moher D, Schulz KF, Hoey J (2008) Guidelines for reporting health research: the EQUATOR Networ’s survey of guideline authors. PLoS Med 5(6):e139. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050139

Singh G, Haddad KM, Chow CW (2007) Are articles in “top” management journals necessarily of higher quality? J Manag Inq 16(4):319–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492607305894

Stewart LA, Clarke M, Rovers M, Riley RD, Simmonds M, Stewart G, Tierney JF (2015) Preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data: the PRISMA-IPD statement. JAMA 313(16):1657–1665. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.3656

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB (2000) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA 283(15):2008–2012. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.283.15.2008

Templier M, Paré G (2018) Transparency in literature reviews: an assessment of reporting practices across review types and genres in top IS journals. Eur J Inf Syst 27(5):503–550. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2017.1398880

Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J (2012) Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol 12(1):181. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-12-181

Tornquist EM, Funk SG, Champagne MT (1989) Writing research reports for clinical audiences. West J Nurs Res 11(5):576–582. https://doi.org/10.1177/019394598901100507

Torraco RJ (2005) Writing integrative literature reviews: guidelines and examples. Hum Resour Dev Rev 4(3):356–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484305278283

Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, Poole C, Schlesselman JJ, Egger M, STROBE Initiative (2007) Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 4(10):e297. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040297

Webster J, Watson RT (2002) Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: writing a literature review. MIS Quart 26(2):xiii–xxiii

Welch V, Petticrew M, Tugwell P, Moher D, O’Neill J, Waters E, White H (2012) PRISMA-equity 2012 extension: reporting guidelines for systematic reviews with a focus on health equity. PLoS Med 9(10):e1001333. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001333

Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R (2013a) RAMESES publication standards: meta-narrative reviews. BMC Med 11(1):20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-20

Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R (2013b) RAMESES publication standards: realist syntheses. BMC Med 11(1):21(21–14). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-21

Yoshii A, Plaut DA, McGraw KA, Anderson MJ, Wellik KE (2009) Analysis of the reporting of search strategies in cochrane systematic reviews. J Med Libr Assoc: JMLA 97(1):21–29. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.97.1.004

Zhang J, Han L, Shields L, Tian J, Wang J (2019) A PRISMA assessment of the reporting quality of systematic reviews of nursing published in the Cochrane library and paper-based journals. Medicine 98(49):e18099. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000018099

Zumsteg JM, Cooper JS, Noon MS (2012) Systematic review checklist. J Ind Ecol 16(s1):S12–S21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9290.2012.00476.x

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK

Rob Dekkers

Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow, UK

Lindsey Carey

Peter Langhorne

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Dekkers, R., Carey, L., Langhorne, P. (2022). Reporting Standards for Literature Reviews. In: Making Literature Reviews Work: A Multidisciplinary Guide to Systematic Approaches. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90025-0_13

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90025-0_13

Published : 11 August 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-90024-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-90025-0

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Jump to navigation

Cochrane Training

Chapter iii: reporting the review.

Miranda Cumpston, Toby Lasserson, Ella Flemyng, Matthew J Page

Key Points:

- Clear reporting of a systematic review allows readers to evaluate the rigour of the methods applied, and to interpret the findings appropriately. Transparency can facilitate attempts to verify or reproduce the results, and make the review more usable for health care decision makers.

- The target audience for Cochrane Reviews is people making decisions about health care, including healthcare professionals, consumers and policy makers. Cochrane Reviews should be written so that they are easy to read and understand by someone with a basic sense of the topic who may not necessarily be an expert in the area.

- Cochrane Protocols and Reviews should comply with the PRISMA 2020 and PRISMA for Protocols reporting guidelines.

- Guidance on the composition of plain language summaries of Cochrane Reviews is also available to help review authors specify the key messages in terms that are accessible to consumers and non-expert readers.

- Review authors should ensure that reporting of objectives, important outcomes, results, caveats and conclusions is consistent across the main text, the abstract, and any other summary versions of the review (e.g. plain language summary).

This chapter should be cited as: Cumpston M, Lasserson T, Flemyng E, Page MJ. Chapter III: Reporting the review. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023). Cochrane, 2023. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

III.1 Introduction

The effort of undertaking a systematic review is wasted if review authors do not report clearly what they did and what they found ( Glasziou et al 2014 ). Clear reporting enables others to replicate the methods used in the review, which can facilitate attempts to verify or reproduce the results ( Page et al 2018 ). Transparency can also make the review more usable for healthcare decision makers. For example, clearly describing the interventions assigned in the included studies can help users determine how best to deliver effective interventions in practice ( Hoffmann et al 2017 ). Also, comprehensively describing the eligibility criteria applied, sources consulted, analyses conducted, and post-hoc decisions made, can reduce uncertainties in assessments of risk of bias in the review findings ( Whiting et al 2016 ). For these reasons, transparent reporting is an essential component of all systematic reviews.

Surveys of the transparency of published systematic reviews suggest that many elements of systematic reviews could be reported better. For example, Nguyen and colleagues evaluated a random sample of 300 systematic reviews of interventions indexed in bibliographic databases in November 2020 ( Nguyen et al 2022 ). They found that in at least 20% of the reviews there was no information about the years of coverage of the search, the methods used to collect data and appraise studies, or the funding source of the review. Less than half of the reviews provided information on a protocol or registration record for the review. However, Cochrane Reviews, which accounted for 3% of the sample, had more complete reporting than all other types of systematic reviews.

Possible reasons why more complete reporting of Cochrane Reviews has been observed include the use of software (RevMan, https://training.cochrane.org/online-learning/core-software-cochrane-reviews/revman ) and strategies in the editorial process that promote good reporting. RevMan includes many standard headings and subheadings which are designed to prompt Cochrane Review authors to document their methods and results clearly.

Cochrane Reviews of interventions should adhere to the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis) reporting guideline; see http://www.prisma-statement.org/ . PRISMA is an evidence-based, minimum set of items for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses to ensure the highest possible standard for reporting is met. Extensions to PRISMA and additional reporting guidelines for specific areas of methods are cited in the relevant sections below.

Cochrane’s Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews (MECIR) detail standards for the conduct of Cochrane Reviews of interventions. They provide expectations for the general methodological approach to be followed from designing the review up to interpreting the findings at the end. There is a good reason to distinguish between conduct (MECIR) and reporting (PRISMA): good conduct does not necessarily lead to good reporting, good reporting cannot improve poor conduct, and poor reporting can obscure good or poor conduct of a review. The MECIR expectations of conduct are embedded in the relevant chapters of this Handbook and authors should adhere to MECIR throughout the development of their systematic review. MECIR conduct guidance for updates of Cochrane Reviews of interventions are presented in Chapter IV . For the latest version of all MECIR conduct guidance, readers should consult the MECIR web pages, available at https://methods.cochrane.org/mecir .

This chapter is built on reporting guidance from PRISMA 2020 ( Page et al 2021a , Page et al 2021b ) and is divided into sections for Cochrane Review protocols ( Section III.2) and new Cochrane Reviews ( Section III.3 ). Many of the standard headings recommended for use in Cochrane Reviews are referred to in this chapter, although the precise headings available in RevMan may be amended as new versions are released. New headings can be added and some standard headings can be deactivated; if the latter is done, review authors should ensure that all information expected (as outlined in PRISMA 2020) is still reported somewhere in the review.

III.2 Reporting of protocols of new Cochrane Reviews

Preparing a well-written review protocol is important for many reasons (see Chapter 1 ). The protocol is a public record of the question of interest and the intended methods before results of the studies are fully known. This helps readers to judge how the eligibility criteria of the review, stated outcomes and planned methods will address the intended question of interest. It also helps anyone who evaluates the completed review to judge how far it fulfilled its original objectives ( Lasserson et al 2016 ). Investing effort in the development of the review question and planning of methods also stimulates review authors to anticipate methodological challenges that may arise, and helps minimize potential for non-reporting biases by encouraging review authors to publish their review and report results for all pre-specified outcomes ( Shamseer et al 2015 ).

See the Introduction and Methods sections of PRISMA 2020 for the reporting items relevant to protocols for new Cochrane Reviews. All these items are also covered in PRISMA for Protocols, an extension to the PRISMA guidelines for the reporting of systematic review protocols ( Moher et al 2015 , Shamseer et al 2015 ). They include guidance for reporting of the:

- Background;

- Objectives;

- Criteria for considering studies for inclusion in the review;

- Search methods for identification of studies (e.g. a list of all sources that will be searched, a complete search strategy to be implemented for at least one database);

- Data collection and analysis (e.g. types of information that will be sought from reports of included studies and methods for obtaining such information, how risk of bias in included studies will be assessed, and any intended statistical methods for combining results across studies); and

- Other information (e.g. acknowledgements, contributions of authors, declarations of interest, and sources of support).

These sections correspond to the same sections in a completed review, and further details are outlined in Section III.3 .

The required reporting items have been incorporated into a template for protocols for Cochrane Reviews, which is available in Cochrane’s review production tool, RevMan (see the RevMan Knowledge Base ). If using the template, authors should carefully consider the methods that are appropriate for their specific review and adapt the template where required.

One key difference between a review protocol and a completed review is that the Methods section in a protocol should be written in the future tense. Because Cochrane Reviews are updated as new evidence accumulates, methods outlined in the protocol should generally be written as if a suitably large number of studies will be identified to allow the objectives to be met (even if this is assumed to be unlikely the case at the time of writing).

PRISMA 2020 reflects the minimum expectations for good reporting of a review protocol. Further guidance on the level of planning required for each aspect of the review methods and the detailed information recommended for inclusion in the protocol is given in the relevant chapters of this Handbook.

III.3 Reporting of new Cochrane Reviews

The main text of a Cochrane Review should be succinct and readable. Although there is no formal word limit for Cochrane Reviews, review authors should consider 10,000 words a maximum for the main text of the review unless there is a special reason to write a longer review, such as when the question is unusually broad or complex.

People making decisions about health care are the target audience for Cochrane Reviews. This includes healthcare professionals, consumers and policy makers, and reviews should be accessible to these audiences. Cochrane Reviews should be written so that they are easy to read and understand by someone with a basic sense of the topic who is not necessarily an expert in the area. Some explanation of terms and concepts is likely to be helpful, and perhaps even essential. However, too much explanation can detract from the readability of a review. Simplicity and clarity are also vital to readability. The readability of Cochrane Reviews should compare to that of a well-written article in a general medical journal.

Review authors should ensure that reporting of objectives, outcomes, results, caveats and conclusions is consistent across the main text, the tables and figures, the abstract, and any other summary versions of the review (e.g. ‘Summary of findings’ table and plain language summary). Although this sounds simple, it can be challenging in practice; authors should review their text carefully to ensure that readers of a summary version are likely to come away with the same overall understanding of the conclusions of the review as readers accessing the full text.

Plagiarism is not acceptable and all sources of information should be cited (for more information see the Cochrane Library editorial policy on plagiarism ). Also, the unattributed reproduction of text from other sources should be avoided. Quotes from other published or unpublished sources should be indicated and attributed clearly, and permission may be required to reproduce any published figures.

PRISMA 2020 provides the main reporting items for new Cochrane Reviews. A template for Cochrane Reviews of interventions is available that incorporates the relevant reporting guidance from PRISMA 2020. The template is available in RevMan to facilitate author adherence to the reporting guidance via the RevMan Knowledge Base . If using the template, authors should consider carefully the methods that are appropriate for their specific review and adapt the template where required. In the remainder of this section we summarize the reporting guidance relating to different sections of a Cochrane Review.

III.3.1 Abstract

All reviews should include an abstract of not more than 1000 words, although in the interests of brevity, authors should aim to include no more than 700 words, without sacrificing important content. Abstracts should be targeted primarily at healthcare decision makers (clinicians, consumers and policy makers) rather than just to researchers.

Terminology should be reasonably easy to understand for a general rather than a specialist healthcare audience. Abbreviations should be avoided, except where they are widely understood (e.g. HIV). Where essential, other abbreviations should be spelt out (with the abbreviations in brackets) on first use. Names of drugs and interventions that can be understood internationally should be used wherever possible. Trade or brand names should not be used and generic names are preferred.

Abstracts of Cochrane Reviews are made freely available on the internet and published in bibliographic databases that index the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (e.g. MEDLINE, Embase). Some readers may be unable to access the full review, or the full text may not have been translated into their language, so abstracts may be the only source they have to understand the review results ( Beller et al 2013 ). It is important therefore that they can be read as stand-alone documents. The abstract should summarize the key methods, results and conclusions of the review. An abstract should not contain any information that is not in the main body of the review, and the overall messages should be consistent with the conclusions of the review.

Abstracts for Cochrane Reviews of interventions should follow the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist ( Page et al 2021b ). Each abstract should include:

- Rationale (a concise summary of the rationale for and context of the review);

- Objectives (of the review);

- Search methods (including an indication of databases searched, and the date of the last search for which studies were fully incorporated);

- Eligibility criteria (including a summary of eligibility criteria for study designs, participants, interventions and comparators);

- Risk of bias (methods used to assess risk of bias);

- Synthesis methods (methods used to synthesize results, especially any variations on standard approaches);

- Included studies (total number of studies and participants and a brief summary of key characteristics);

- Results of syntheses (including the number of studies and participants for each outcome, a clear statement of the direction and magnitude of the effect, the effect estimate and 95% confidence interval if meta-analysis was used, and the GRADE assessment of the certainty of the evidence. The results should contain the same outcomes as found in other summary formats such as the plain language summary and ‘Summary of findings’ table, including those for which no studies reported the outcome and those that are not statistically significant. This section should also provide a brief summary of the limitations of the evidence included in the review);

- Authors’ conclusions (including implications both for practice and for research);

- Funding (primary source of funding for the review); and

- Registration (registration name and number and/or DOIs of previously published protocols and versions of the review, if applicable).

III.3.2 Plain language summary

A Cochrane Plain language summary is a stand-alone summary of the systematic review. Like the Abstract, the Plain language summary may be read alone, and its overall messages should be consistent with the conclusions in the full review. The Plain language summary should convey clearly the questions and key findings of the review, using language that can be understood by a wide range of non-expert readers. The summary should use words and sentence structures that are easy to understand, and should avoid technical terms and jargon where possible. Any technical terms used should be explained. The audience for Plain language summaries may include people with a health condition, carers, healthcare workers or policy makers. Readers may not have English as their first language. Cochrane Plain language summaries are frequently translated, and using plain language is also helpful for translators.

Writing in plain language is a skill that is different from writing for a scientific audience. Full guidance and a template are available as online supplementary material to this chapter. Authors are strongly encouraged to use this guidance to ensure good practice and consistency with other summaries in the Cochrane Library. It may also be helpful to seek assistance for this task, such as asking someone with experience in writing in plain language for a general audience for help, or seeking feedback on the draft summary from a consumer or someone with little knowledge of the topic area.

III.3.3 Background and Objectives

Well-formulated review questions occur in the context of an already-formed body of knowledge. The Background section should address this context, including a description of the condition or problem of interest. It should help clarify the rationale for the review, and explain why the questions being addressed are important. It should be concise (generally under 1000 words) and be understandable to the users of the intervention(s) under investigation.

It is important that the eligibility criteria and other aspects of the methods, such as the comparisons used in the synthesis, build on ideas that have been developed in the Background section. For example, if there are uncertainties to be explored in how variation in setting, different populations or type of intervention influence the intervention effect, then it would be important to acknowledge these as objectives of the review, and ensure the concepts and rationale are explained.

The following three standard subheadings in the Background section of a Cochrane Review are intended to facilitate a structured approach to the context and overall rationale for the review.

- Description of the condition: A brief description of the condition being addressed, who is affected, and its significance, is a useful way to begin the review. It may include information about the biology, diagnosis, prognosis, prevalence, incidence and burden of the condition, and may consider equity or variation in how different populations are affected.

- Description of the intervention and how it might work: A description of the experimental intervention(s) should place it in the context of any standard or alternative interventions, remembering that standard practice may vary widely according to context. The role of the comparator intervention(s) in standard practice should also be made clear. For drugs, basic information on clinical pharmacology should be presented where available, such as dose range, metabolism, selective effects, half-life, duration and any known interactions with other drugs. For more complex interventions, such as behavioural or service-level interventions, a description of the main components should be provided (see Chapter 17 ). This section should also provide theoretical reasoning as to why the intervention(s) under review may have an impact on potential recipients, for example, by relating a drug intervention to the biology of the condition. Authors may refer to a body of empirical evidence such as similar interventions having an impact on the target recipients or identical interventions having an impact on other populations. Authors may also refer to a body of literature that justifies the possibility of effectiveness. Authors may find it helpful to use a logic model ( Kneale et al 2015 ) or conceptual framework to illustrate the proposed mechanism of action of the intervention and its components. This will also provide review authors with a framework for the methods and analyses undertaken throughout the review to ensure that the review question is clearly and appropriately addressed. More guidance on considering the conceptual framework for a particular review question is presented in Chapter 2 and Chapter 17 .

- Why it is important to do this review: Review authors should explain clearly why the questions being asked are important. Rather than justifying the review on the grounds that there are known eligible studies, it is more helpful to emphasize what aspects of, or uncertainties in, the accumulating evidence base now justify a systematic review. For example, it might be the case that studies have reached conflicting conclusions, that there is debate about the evidence to date, or that there are competing approaches to implementing the intervention.

Immediately following the Background section of the review, review authors should declare the review objectives. They should begin with a precise statement of the primary objective of the review, ideally in a single sentence. Where possible the style should be of the form “To assess the effects of [intervention or comparison] for [health problem] for/in [types of people, disease or problem and setting if specified] ”. This might be followed by a series of secondary objectives relating to different participant groups, different comparisons of interventions or different outcome measures. If relevant, any objectives relating to the evaluation of economic or qualitative evidence should be stated. It is not necessary to state specific hypotheses.

III.3.4 Methods

The Methods section in a completed review should be written in the past tense, and should describe what was done to obtain the results and conclusions of the current review.

Review authors are expected to cite their protocol to make it clear that there was one. Often a review is unable to implement all the methods outlined in the protocol. For example, planned investigations of heterogeneity (e.g. subgroup analyses) and small-study effects may not have been conducted because of an insufficient number of studies. Authors should describe and explain all amendments to the prespecified methods in the main Methods section.

The Methods section of a Cochrane Review includes five main subsections, within which are a series of standard headings to guide authors in reporting all the relevant information. See Sections III.3.4.1 , III.3.4.2 , III.3.4.3 , III.3.4.4, and III.3.4.5 for a summary of content recommended for inclusion under each subheading.

III.3.4.1 Criteria for considering studies for this review

Review authors should declare all criteria used to decide which studies are included in the review. Doing so will help readers understand the scope of the review and recognize why particular studies they are aware of were not included. Eligible study designs should be described, with a focus on specific features of a study’s design rather than design labels (e.g. how groups were formed, whether the intervention was assigned to individuals or clusters of individuals) ( Reeves et al 2017 ). Review authors should describe eligibility criteria for participants, including any restrictions based on age, diagnostic criteria, location and setting. If relevant, it is useful to describe how studies including a subset of relevant participants were addressed (e.g. when children up to the age of 16 years only were eligible but a study included children up to the age of 18 years). Eligibility criteria for interventions and comparators should be stated also, including any criteria around delivery, dose, duration, intensity, co-interventions and characteristics of complex interventions. The rationale for all criteria should be clear, including the eligible study designs.