- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Action Research in Education

Introduction.

- Chapters and Articles

- Theory and Ethics

- Practical Texts for Individual Teachers

- Collaborative Inquiry and School-Wide Teams for Administrators and School Leaders

- Action Research in Teacher Education

- Action Research in Graduate Education

- PAR Inquiry Processes

- Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR)

- Critical Participatory Action Research

- Critical Youth Participatory Action Research

- International Perspectives

- Exemplary Case Studies

- Practitioner Journals for Action Researchers across All Disciplines

- Research Journals for Action Researchers across All Disciplines

- Journals Primarily for English/Language Arts/Literacy Educators, Teacher Educators, and Researchers

- Action Research Organizations

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Ethical Research with Young Children

- Grounded Theory

- Methodologies for Conducting Education Research

- Mixed Methods Research

- Qualitative Data Analysis Techniques

- Qualitative Research Design

- Social Science and Education Research

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Gender, Power, and Politics in the Academy

- Girls' Education in the Developing World

- Non-Formal & Informal Environmental Education

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Action Research in Education by Mary Beth Hines , Kerry Armbruster , Adam Henze , Maria Lisak , Christina Romero-Ivanova , Leslie Rowland , Lottie Waggoner LAST REVIEWED: 02 May 2019 LAST MODIFIED: 15 January 2020 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0140

Educational action research involves participants conducting inquiry into their own practices in order to improve teaching and learning, practices and programs. This means that the researcher is a participant in the activity being investigated, be it in schools or community centers—wherever teaching and learning occur. In Guiding School Improvement with Action Research ( Sagor 2000 , cited under Collaborative Inquiry and School-Wide Teams for Administrators and School Leaders ), Richard Sagor describes action research as “a disciplined process of inquiry conducted by and for those taking the action . . .[in order to] assist the “actor” in improving and/or refining his or her actions” (p. 3). The term “educational action research” encompasses a variety of approaches with different goals (see Historical Overviews of Educational Action Research ). While no consensus exists on a taxonomy that best describes its variations (modes, goals, epistemologies, politics, processes), most analyses identify the following types: (1) “Teacher research” signifies P-16 teacher-conducted inquiry designed to explore research questions related to educational improvement. It is often used interchangeably with “practitioner research/participant inquiry,” although this is a broader term that also refers to projects initiated by others in the educational experience (e.g., administrators, staff, community members). (2) “Participatory action research” (PAR) emphasizes equal, collaborative participation among university and/or school personnel and/or others with vested interests in education, working toward the shared goal of producing educational change. (3) “Youth participatory action research” (YPAR) includes young people as research partners and agents of change. (4) “Critical action research” refers to investigations of underlying power relations present in one’s situated educational practices. All educational action research is designed to impact local policy and practice. Critiques of action research object to this focus on the micro level, claiming that it does not impact education beyond the immediate audience. However, this viewpoint obscures the fact that qualitative action research case studies and cross-case analyses are generalizable to theory, thus carrying the potential to create widespread change. Another critique centers on the limited effectiveness of connecting action research with social justice. However, others argue that social justice is inextricably woven into action research because the inquiry stems from grassroots movements that emphasize social change ( Cochran-Smith and Lytle 2009 , cited under Books ) and privileges the educator’s “insider” knowledge alongside the outside researcher’s formal academic training. The following criteria were used for selecting the texts cited in this article: (1) texts that were peer-reviewed, (2) texts explicitly described as action research (or a synonymous term) by the writer or other scholars, (3) texts cited more frequently than other texts on the same issue, (4) texts originally written in English. These criteria guidelines eliminated the use of dissertations, conference papers, blogs, or pedagogical narratives that were not described as action research (or a comparable term), or reports written in other languages.

Historical Overviews of Educational Action Research

This section contains key texts in defining and outlining the history of educational action research. The scholars whose works are included are among the most cited, recognized, and respected in this field. These articles and books will aid in understanding the spectrum of issues that led to action research’s inception as well as its implementations, changes, and ideologies. This section is broken into shorter works ( Chapters and Articles ) and longer works ( Books ) that will guide the reader in gaining a better understanding of action research’s past and its growth as an area of study.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Education »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Academic Achievement

- Academic Audit for Universities

- Academic Freedom and Tenure in the United States

- Action Research in Education

- Adjuncts in Higher Education in the United States

- Administrator Preparation

- Adolescence

- Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate Courses

- Advocacy and Activism in Early Childhood

- African American Racial Identity and Learning

- Alaska Native Education

- Alternative Certification Programs for Educators

- Alternative Schools

- American Indian Education

- Animals in Environmental Education

- Art Education

- Artificial Intelligence and Learning

- Assessing School Leader Effectiveness

- Assessment, Behavioral

- Assessment, Educational

- Assessment in Early Childhood Education

- Assistive Technology

- Augmented Reality in Education

- Beginning-Teacher Induction

- Bilingual Education and Bilingualism

- Black Undergraduate Women: Critical Race and Gender Perspe...

- Blended Learning

- Case Study in Education Research

- Changing Professional and Academic Identities

- Character Education

- Children’s and Young Adult Literature

- Children's Beliefs about Intelligence

- Children's Rights in Early Childhood Education

- Citizenship Education

- Civic and Social Engagement of Higher Education

- Classroom Learning Environments: Assessing and Investigati...

- Classroom Management

- Coherent Instructional Systems at the School and School Sy...

- College Admissions in the United States

- College Athletics in the United States

- Community Relations

- Comparative Education

- Computer-Assisted Language Learning

- Computer-Based Testing

- Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Evaluating Improvement Net...

- Continuous Improvement and "High Leverage" Educational Pro...

- Counseling in Schools

- Critical Approaches to Gender in Higher Education

- Critical Perspectives on Educational Innovation and Improv...

- Critical Race Theory

- Crossborder and Transnational Higher Education

- Cross-National Research on Continuous Improvement

- Cross-Sector Research on Continuous Learning and Improveme...

- Cultural Diversity in Early Childhood Education

- Culturally Responsive Leadership

- Culturally Responsive Pedagogies

- Culturally Responsive Teacher Education in the United Stat...

- Curriculum Design

- Data Collection in Educational Research

- Data-driven Decision Making in the United States

- Deaf Education

- Desegregation and Integration

- Design Thinking and the Learning Sciences: Theoretical, Pr...

- Development, Moral

- Dialogic Pedagogy

- Digital Age Teacher, The

- Digital Citizenship

- Digital Divides

- Disabilities

- Distance Learning

- Distributed Leadership

- Doctoral Education and Training

- Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) in Denmark

- Early Childhood Education and Development in Mexico

- Early Childhood Education in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Childhood Education in Australia

- Early Childhood Education in China

- Early Childhood Education in Europe

- Early Childhood Education in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Early Childhood Education in Sweden

- Early Childhood Education Pedagogy

- Early Childhood Education Policy

- Early Childhood Education, The Arts in

- Early Childhood Mathematics

- Early Childhood Science

- Early Childhood Teacher Education

- Early Childhood Teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Years Professionalism and Professionalization Polici...

- Economics of Education

- Education For Children with Autism

- Education for Sustainable Development

- Education Leadership, Empirical Perspectives in

- Education of Native Hawaiian Students

- Education Reform and School Change

- Educational Statistics for Longitudinal Research

- Educator Partnerships with Parents and Families with a Foc...

- Emotional and Affective Issues in Environmental and Sustai...

- Emotional and Behavioral Disorders

- Environmental and Science Education: Overlaps and Issues

- Environmental Education

- Environmental Education in Brazil

- Epistemic Beliefs

- Equity and Improvement: Engaging Communities in Educationa...

- Equity, Ethnicity, Diversity, and Excellence in Education

- Ethics and Education

- Ethics of Teaching

- Ethnic Studies

- Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention

- Family and Community Partnerships in Education

- Family Day Care

- Federal Government Programs and Issues

- Feminization of Labor in Academia

- Finance, Education

- Financial Aid

- Formative Assessment

- Future-Focused Education

- Gender and Achievement

- Gender and Alternative Education

- Gender-Based Violence on University Campuses

- Gifted Education

- Global Mindedness and Global Citizenship Education

- Global University Rankings

- Governance, Education

- Growth of Effective Mental Health Services in Schools in t...

- Higher Education and Globalization

- Higher Education and the Developing World

- Higher Education Faculty Characteristics and Trends in the...

- Higher Education Finance

- Higher Education Governance

- Higher Education Graduate Outcomes and Destinations

- Higher Education in Africa

- Higher Education in China

- Higher Education in Latin America

- Higher Education in the United States, Historical Evolutio...

- Higher Education, International Issues in

- Higher Education Management

- Higher Education Policy

- Higher Education Research

- Higher Education Student Assessment

- High-stakes Testing

- History of Early Childhood Education in the United States

- History of Education in the United States

- History of Technology Integration in Education

- Homeschooling

- Inclusion in Early Childhood: Difference, Disability, and ...

- Inclusive Education

- Indigenous Education in a Global Context

- Indigenous Learning Environments

- Indigenous Students in Higher Education in the United Stat...

- Infant and Toddler Pedagogy

- Inservice Teacher Education

- Integrating Art across the Curriculum

- Intelligence

- Intensive Interventions for Children and Adolescents with ...

- International Perspectives on Academic Freedom

- Intersectionality and Education

- Knowledge Development in Early Childhood

- Leadership Development, Coaching and Feedback for

- Leadership in Early Childhood Education

- Leadership Training with an Emphasis on the United States

- Learning Analytics in Higher Education

- Learning Difficulties

- Learning, Lifelong

- Learning, Multimedia

- Learning Strategies

- Legal Matters and Education Law

- LGBT Youth in Schools

- Linguistic Diversity

- Linguistically Inclusive Pedagogy

- Literacy Development and Language Acquisition

- Literature Reviews

- Mathematics Identity

- Mathematics Instruction and Interventions for Students wit...

- Mathematics Teacher Education

- Measurement for Improvement in Education

- Measurement in Education in the United States

- Meta-Analysis and Research Synthesis in Education

- Methodological Approaches for Impact Evaluation in Educati...

- Mindfulness, Learning, and Education

- Motherscholars

- Multiliteracies in Early Childhood Education

- Multiple Documents Literacy: Theory, Research, and Applica...

- Multivariate Research Methodology

- Museums, Education, and Curriculum

- Music Education

- Narrative Research in Education

- Native American Studies

- Note-Taking

- Numeracy Education

- One-to-One Technology in the K-12 Classroom

- Online Education

- Open Education

- Organizing for Continuous Improvement in Education

- Organizing Schools for the Inclusion of Students with Disa...

- Outdoor Play and Learning

- Outdoor Play and Learning in Early Childhood Education

- Pedagogical Leadership

- Pedagogy of Teacher Education, A

- Performance Objectives and Measurement

- Performance-based Research Assessment in Higher Education

- Performance-based Research Funding

- Phenomenology in Educational Research

- Philosophy of Education

- Physical Education

- Podcasts in Education

- Policy Context of United States Educational Innovation and...

- Politics of Education

- Portable Technology Use in Special Education Programs and ...

- Post-humanism and Environmental Education

- Pre-Service Teacher Education

- Problem Solving

- Productivity and Higher Education

- Professional Development

- Professional Learning Communities

- Program Evaluation

- Programs and Services for Students with Emotional or Behav...

- Psychology Learning and Teaching

- Psychometric Issues in the Assessment of English Language ...

- Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research Samp...

- Quantitative Research Designs in Educational Research

- Queering the English Language Arts (ELA) Writing Classroom

- Race and Affirmative Action in Higher Education

- Reading Education

- Refugee and New Immigrant Learners

- Relational and Developmental Trauma and Schools

- Relational Pedagogies in Early Childhood Education

- Reliability in Educational Assessments

- Religion in Elementary and Secondary Education in the Unit...

- Researcher Development and Skills Training within the Cont...

- Research-Practice Partnerships in Education within the Uni...

- Response to Intervention

- Restorative Practices

- Risky Play in Early Childhood Education

- Scale and Sustainability of Education Innovation and Impro...

- Scaling Up Research-based Educational Practices

- School Accreditation

- School Choice

- School Culture

- School District Budgeting and Financial Management in the ...

- School Improvement through Inclusive Education

- School Reform

- Schools, Private and Independent

- School-Wide Positive Behavior Support

- Science Education

- Secondary to Postsecondary Transition Issues

- Self-Regulated Learning

- Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices

- Service-Learning

- Severe Disabilities

- Single Salary Schedule

- Single-sex Education

- Single-Subject Research Design

- Social Context of Education

- Social Justice

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Pedagogy

- Social Studies Education

- Sociology of Education

- Standards-Based Education

- Statistical Assumptions

- Student Access, Equity, and Diversity in Higher Education

- Student Assignment Policy

- Student Engagement in Tertiary Education

- Student Learning, Development, Engagement, and Motivation ...

- Student Participation

- Student Voice in Teacher Development

- Sustainability Education in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Higher Education

- Teacher Beliefs and Epistemologies

- Teacher Collaboration in School Improvement

- Teacher Evaluation and Teacher Effectiveness

- Teacher Preparation

- Teacher Training and Development

- Teacher Unions and Associations

- Teacher-Student Relationships

- Teaching Critical Thinking

- Technologies, Teaching, and Learning in Higher Education

- Technology Education in Early Childhood

- Technology, Educational

- Technology-based Assessment

- The Bologna Process

- The Regulation of Standards in Higher Education

- Theories of Educational Leadership

- Three Conceptions of Literacy: Media, Narrative, and Gamin...

- Tracking and Detracking

- Traditions of Quality Improvement in Education

- Transformative Learning

- Transitions in Early Childhood Education

- Tribally Controlled Colleges and Universities in the Unite...

- Understanding the Psycho-Social Dimensions of Schools and ...

- University Faculty Roles and Responsibilities in the Unite...

- Using Ethnography in Educational Research

- Value of Higher Education for Students and Other Stakehold...

- Virtual Learning Environments

- Vocational and Technical Education

- Wellness and Well-Being in Education

- Women's and Gender Studies

- Young Children and Spirituality

- Young Children's Learning Dispositions

- Young Children's Working Theories

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.136]

- 81.177.182.136

Advertisement

Implementing Action Research in EFL/ESL Classrooms: a Systematic Review of Literature 2010–2019

- Published: 09 March 2020

- Volume 33 , pages 341–362, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Amira Desouky Ali ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4175-4194 1

1843 Accesses

4 Citations

Explore all metrics

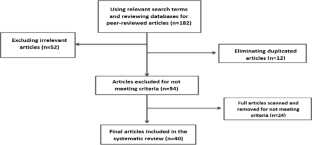

Action research studies in education often address learners’ needs and empower practitioners to effectively change instructional practices and school communities. A systematic review of action research (AR) studies undertaken in EFL/ESL setting was conducted in this paper to systematically analyze empirical studies on action research published within a ten-year period (between 2010 and 2019). The review also aimed at investigating the focal themes in teaching the language skills at school level and evaluating the overall quality of AR studies concerning purpose, participants, and methodology. Inclusion criteria were established and 40 studies that fit were finally selected for the systematic review. Garrard’s ( 2007 ) Matrix Method was used to structure and synthesize the literature. Results showed a significant diversity in teaching the language skills and implementation of the AR model. Moreover, findings revealed that (50%) of the studies used a mixed-method approach followed by a qualitative method (37.5%); whereas only (12.5%) employed quantitative methodology. Research gaps for future action research in developing language skills were highlighted and recommendations were offered.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Transforming Educational Practice Through Action Research: Three Australian Examples

Challenges in Teaching Tertiary English: Benefits of Action Research, Professional Reflection and Professional Development

Educational action research in south korea: finding new meanings in practitioner-based research.

Abdallah MS (2016) Towards improving content and instruction of the ‘TESOL/TEFL for special needs’ course: an action research study. Educ Action Res 25(3):420–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2016.1173567

Article Google Scholar

Ahmad S (2012) Pedagogical action research projects to improve the teaching skills of Egyptian EFL student teachers. Proceedings of the ICERI2012, 5th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation (PP.3589-3598). Madrid: Spain

Ahn H (2012) Teaching writing skills based on a genre approach to L2 primary school students: an action research. Engl Lang Teach 5(2):2–16

Google Scholar

Ainscow M, Booth T, Dyson A (2004) Understanding and developing inclusive practices in schools: a collaborative action research network. Int J Incl Educ 8(2):125–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360311032000158015

Allwright D, Bailey KM (1991) Focus on the language classroom: an introduction to classroom research for language teachers. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Alsowat H (2017) A systematic review of research on teaching English language skills for Saudi EFL students. Adv Lang Lit Stud 8(5):30–45

Alvarez CLF (2014) Selective use of the mother tongue to enhance students’ English learning processes…beyond the same assumptions. PROFILE Issues Teach Prof Dev 16(1):137–151. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n1.38661

Arteaga-Lara HM (2017) Using the process-genre approach to improve fourth-grade EFL learners’ paragraph writing. Lat Am J Content Lang Integr Learn 10(2):217–244. https://doi.org/10.5294/laclil.2017.10.2.3

Bethany-Saltikov J (2012) How to do a systematic literature review in nursing: a step-by-step guide. Open University Press, Maidenhead

Burns A (2010) Doing action research in English language teaching: a guide for practitioners. Routledge, New York, p 196 ISBN 978-0-415-99145-2

Campbell E, Cuba M (2015) Analyzing the role of visual cues in developing prediction-making skills of third- and ninth-grade English language learners. CATESOL J 27(1):53–93

Campbell YC, Filimon C (2018) Supporting the argumentative writing of students in linguistically diverse classrooms: an action research study. RMLE Online 41(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404476.2017.1402408

Carolina B, Astrid R (2018) Speaking activities to foster students’ oral performance at a public school. Engl Lang Teach 11(8):65–72

Carr W, Kemmis S (1986) Becoming critical: education. knowledge and action research. Falmer, London

Cerón CN (2014) The effect of story read-alouds on children’s foreign language development. Gist Educ Learn Res J 8:83–98

Chaves O, Fernandez A (2016) A didactic proposal for EFL in a public school in Cali. HOW 23(1):10–29. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.23.1.139

Chen S, Huang F, Zeng W (2018) Comments on systematic methodologies of action research in the new millennium: a review of publications 2000–2014. Action Res 16(4):341–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750317691103

Cho Y, Egan TM (2009) Action learning research: a systematic review and conceptual framework. Hum Resour Dev Rev 8(4):431–462 SAGE Publications

Cochrane TD (2014) Critical success factors for transforming pedagogy with mobile web 2.0. Br J Educ Technol 45(1):65–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01384.x

Cooper K, White RE (2012) Qualitative research in the postmodern era: contexts of qualitative research. Springer, Dordrecht

Dewi R, Kultsum U, Armadi A (2017) Using communicative games in improving students’ speaking skills. Engl Lang Teach 10(1):63–71

El-Deghaidy H (2012) Education for sustainable development: experiences from action research with science teachers. Discourse Commun Sustain Educ 3(1):23–40

Elliott J (1991) Action research for educational change. Open University Press, Milton Keynes

Fahrurrozi (2017) Improving students’ vocabulary mastery by using Total physical response. Engl Lang Teach 10(3):118–127. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v10n3p118

Fischer JC (2001) Action research, rationale and planning: developing a framework for teacher inquiry. In: Burnaford G, Fischer J, Hobson D (eds) Teachers doing research: The power of action through inquiry, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, pp 29–48

Fullerton S, Clemson A, Robson K (2015) Using a scaffolded multi-component intervention to support the reading and writing development of English learners. i.e. Inq Educ 7(1):1–20 http://digitalcommons.nl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1104&context=ie

Gámez DY, Cuellar JA (2019) The use of Plotagon to enhance the English writing skill in secondary school students. Profile Issues Teach Prof Dev 21(1):139–153. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v21n1.71721

Garrard J (2007) Health sciences literature review made easy: the matrix method. Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Sudbury

Greenwood DJ, Levin M (1998) Introduction to action research: social research for social change. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Gutiérrez KG, Puello MN, Galvis LA (2015) Using pictures series technique to enhance narrative writing among ninth grade students at Institución Educativa Simón Araujo. Engl Lang Teach 8(5):45–71

Halwani N (2017) Visual aids and multimedia in second language acquisition. Engl Lang Teach 10(6):53–59

Hamilton C (2018) The Effects of peer-revision on student writing performance in a middle school ELA classroom (doctoral dissertation). University of South Carolina. ProQuest: Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4596

Han L (2017) Analysis of the problems in language teachers’ action research. Int Educ Stud 10(11):123–128

Jaime-Osorio MF, Caicedo-Muñoz MC, Trujillo-Bohórquez IC (2019) A radio program: a strategy to develop students’ speaking and citizenship skills. HOW 26(1):8–33. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.26.1.470

Jones-Jackson B (2015) Supplemental Literacy Instruction: Examining its effects on student learning and achievement outcomes: An action research study (doctoral dissertation). Capella University, ProQuest: Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED558987

Juriah J (2015) Implementing controlled composition to improve vocabulary mastery of EFL students. Dinamika Ilmu 15(1):137–162

Kemmis S, McTaggert R (1998) The action research planner. Deakin University Press, Geelong

Kostandy M (2013) Teachers as agents of change: A case study of action research for school improvement in Egypt (unpublished Master’s thesis). American University in Cairo, Graduate School of Education, Cairo, Egypt

Lan Y-J (2015) Action research contextual EFL learning in a 3D virtual environment. Lang Learn Technol 19(2):16–31

Lavalle PI, Briesmaster M (2017) The study of the use of picture descriptions in enhancing communication skills among the 8th-grade students—learners of English as a foreign language. I.e. Inq Educ 9(1):1–16 Article 4

Lee MW (2018) Translation revisited for low-proficiency EFL writers. ELT J 72(4):365–373

Madriñan MS (2014) The use of first language in the second-language classroom: a support for second language acquisition. Gist Educ Learn Res J 9:50–66

Marenco-Domínguez JM (2017) Peer-tutoring fosters spoken fluency in computer-mediated tasks. Lat Am J Content Lang Integr Learn 10(2):271–296. https://doi.org/10.5294/laclil.2017.10.2.5

McNiff J, Whitehead J (2006) All you need to know about action research. SAGE Publications, London

Mertler CA (2014) Action research: improving schools and empowering educators (4th ed). SAGE, Thousand Oaks

Miles GE (2006) Action research: A guide for the teacher researcher, 3rd edn. Merrill Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River

Montelongo J, Herter RJ, Ansaldo R, Hatter N (2010) A lesson cycle for teaching expository reading and writing. J Adolesc Adult Lit 53(8):656–666. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.53.8.4

Murillo HA (2013) Adapting features from the SIOP component: lesson delivery to English lessons in a Colombian public school. PROFILE 15(1):171–193

Nair S, Sanai M (2018) Effects of utilizing the STAD method (cooperative learning approach) in enhancing students’ descriptive writing skills. International. J Educ Pract 6(4):239–252

Nasrollahi M, Krishnasamy PN, Noor N (2015) Process of implementing critical Reading strategies in an Iranian EFL classroom: an action research. Int Educ Stud 8(1):9–16

Niño F, Páez M (2018) Building writing skills in English in fifth graders: analysis of strategies based on literature and creativity. Engl Lang Teach 11(9):102–117

Nova J, Chavarro C, Córdoba A (2017) Educational videos: a didactic tool for strengthening English vocabulary through the development of affective learning in kids. Gist Educ Learn Res J 14:68–87

Nurhayati DA (2015) Improving students’ English pronunciation ability through go fish game and maze game. Dinamika Ilmu 15(2):215–233

Ortiz SM, Cuéllar MT (2018) Authentic tasks to foster oral production among English as a foreign language learners. HOW 25(1):51–68. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.1.362

Ortiz-Neira RA (2019) The impact of information gap activities on young EFL learners’ oral fluency. Profile: Issues Teach Prof Dev 21(2):113–125. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v21n2.73385

Samawiyah Z, Saifuddin M (2016) Phonetic symbols through audiolingual method to improve the students’ listening skill. DINAMIKA ILMU 16(1):35–46

Sánchez RA (2017) Reading comprehension course through a genre-oriented approach at a school in Colombia. HOW 24(2):35–62. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.24.2.331

Singh G, Hardaker G (2014) Barriers and enablers to adoption and diffusion of eLearning. Educ Train 56(2/3):105–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-11-2012-0123

Snyder MJ (2012) Reconnecting with your passion: an action research study exploring humanities and professional nursing (doctoral dissertation). ProQuest LLC

Stern T (2014) What is good action research? Considerations about quality criteria. In: Stern T, Townsend A, Rauch F, Schuster A (eds) Action research, innovation and change: international perspectives across disciplines. Routledge, London

Szabo S (2010) Older children need phonemic awareness instruction, too. TESOL J 1(1):130–141

Torres AM, Rodríguez LF (2017) Increasing EFL learners’ oral production at a public school through project-based learning. Profile Issues Teach Prof Dev 19(2):57–71. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n2.59889

Townsend A (2013) Action research: the challenges of understanding and researching practice. Open University Press, Maidenhead Berkshire

Triviño PA (2016) Using cooperative learning to foster the development of adolescents’ English writing skills. Profile Issues Teach Prof Dev 18(1):21–38. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.53079

Urquijo J (2012) Improving oral performance through interactions flashcards (unpublished doctoral dissertation). Centro Colombo Americano, Colombia

Vasileiadou I, Makrina Z (2017) Using online computer games in the ELT classroom: a case study. Engl Lang Teach 10(12):134–150

Vaughan M (2019) The body of literature on action research in education. The Wiley handbook of action research in education, first edition. Edited by Craig a. Mertler, 53-74

Vaughan M, Burnaford G (2015) Action research in graduate teacher education: a review of the literature, 2005-2015. Educ Action Res 24:280–299

Wach A (2014) Action research and teacher development: MA students’ perspective. In Pawlak, Mirosław; Bielak, Jakub; Mystkowska-Wiertelak, Anna (eds.) Classroom-oriented Research. Achievements and Challenges. Heidelberg: Springer, 121–137

Westbrook J (2013) Reading as a hermeneutical Endeavour: whole-class approaches to teaching narrative with low-attaining adolescent readers. Literacy 47(1):42–49

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Languages, Sadat Academy for Management Sciences, 151 Maadi Al Khabiri Al Wasti, Al Maadi, Cairo, 12411, Egypt

Amira Desouky Ali

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Amira Desouky Ali .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Ali, A.D. Implementing Action Research in EFL/ESL Classrooms: a Systematic Review of Literature 2010–2019. Syst Pract Action Res 33 , 341–362 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-020-09523-y

Download citation

Published : 09 March 2020

Issue Date : June 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-020-09523-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Action research

- EFL/ESL context

- Language skills

- Systematic review

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Teaching in the suburbs: participatory action research against educational wastage.

- 1 Department of Humanities, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy

- 2 Non-profit Association Maestri di Strada, Naples, Italy

If teaching is a stressful job, it can be even more so in schools in disadvantaged areas, such as the metropolitan suburbs, where the rates of educational wastage are high. Here, teachers often feel ineffective: as a result, there is a reduced sense of well-being at work, which triggers a negative cycle that damages their educational performance. From the literature, it is known that teachers need social support, which has a positive effect on well-being and resilience. For these reasons, the Association “Maestri di Strada” (MdS) has chosen to offer teachers professional social support and to actively involve them through Teacher Participatory Action Research (T-PAR): the “Crossing Educational Boundaries” project. These are the research questions that gave life to the project: do the teachers have resources to analyze the problematic situations they are immersed in and to build improvement strategies? Would a professional social support reinforce their resilience? The objective was the following: to actively engage the teachers in order to generate hypotheses concerning the causes of educational wastage in their schools, and to work with them to plan new methods to lessen the problem. The project was carried out in 12 suburban secondary schools in six Italian cities. This paper illustrates the activities of three cities. All phases of the T-PAR were completed. The teachers organized discussion groups and started workshops in the classes considered at risk. The activities were subject to non-participant observation, and the observation reports underwent semantic-structural analysis. Four clusters emerged the analysis. The results show that the teachers are aware of the importance of a good educational relationship as a way to oppose educational wastage, and, at the same time, they are aware of the difficulties of building it, which they attribute to the mistrust and passiveness of the pupils, and to the demands of the institution. The moments of discouragement shown by the teachers, and their strong emotional engagement in the pupils’ difficulties are significant. At the end of the project, a small group of teachers planned and implemented a reflective space in some of the schools.

Introduction

Teaching is a stressful and tiring job for a complex variety of reasons linked to multiple factors, including: the nature of the work, which implies a high degree of relationality; personal characteristics, on both a social and emotional level; and school organization, which is influenced by the historical and geographical context ( Kyriacou, 2001 ; Hastings and Bham, 2003 ; Hakanen et al., 2006 ; Bizumic et al., 2009 ; Chang, 2009 ; Day and Gu, 2009 ; Zurlo et al., 2016 ; Steffens et al., 2017 ; Capone et al., 2019 ; Parrello et al., 2019a ). To this end, an extensive array of literature testifies to the importance of cultivating well-being and resilience in teachers, and identifies protection factors and intervention strategies.

In particular, resilience in teachers is defined as a quality that enables teachers to maintain their commitment to teaching and to their teaching practices, despite challenging conditions and recurring setbacks ( Brunetti, 2006 ). Resilient teachers have been described as those who have the capacity to thrive in difficult circumstances, are skilled in behavior management, are able to empathize with difficult students as well as restrain negative emotions and focus on the positive, and who experience a sense of pride, fulfilment, and increased commitment to their school and profession ( Howard and Johnson, 2004 ). Resilience involves the capacity of an individual teacher to harness personal and contextual resources to navigate through educational challenges and to facilitate the outcome of professional engagement, growth, commitment, enthusiasm, satisfaction, and wellbeing ( Beltman, 2015 ). In recent years, researchers have begun to conceptualize resilience from a social-ecological perspective, wherein resilience is defined as a set of behaviors over time that reflect the interactions between individuals and their environments, in particular the opportunities for personal growth that are available and accessible ( Ungar, 2012 ). Some authors speak of relational resilience ( Le Cornu, 2013 ; Gu, 2014 ): in particular, reciprocal and mutually supportive personal, professional and peer relationships are important in this process ( Sammons et al., 2007 ). The outcome is that teachers maintain job satisfaction and commitment to their profession ( Brunetti, 2006 ). Many authors do not explicitly examine resilience, but do address the question of what sustains teachers and what enables them to thrive rather than just survive. These papers could be grouped into three categories, each with a different focus: those emphasizing individual factors; contextual factors; and individual perceptions of, and responses to, the specific contexts of teacher work ( Beltman et al., 2011 ).

The urban suburbs are among the contexts considered at risk. If teaching is always difficult, it can be even more so in schools in these disadvantaged areas. In suburban schools, teachers have to deal with adolescents of lower socio-economic status who often experience distress in their personal lives as well as at school ( Sommantico et al., 2015 ; Pellerone et al., 2018 ; Lavy and Ayuob, 2019 ), and who have an internalized marginality which becomes a learned sense of powerlessness ( David, 2014 ). Teaching in these environments therefore means: interacting and connecting daily with young people who are struggling with problems and pain, as well as working to decrease educational wastage. In these environments, we find both material and educational poverty: the material poverty of one generation often causes the deprivation of educational opportunities for the next ( Jones, 2003 ; Lott, 2012 ; OCSE, 2015 ). In order to break this vicious circle, schools in deprived areas will need more funds and investments. In Italy, on the contrary, schools populated by disadvantaged students tend to have fewer resources ( OCSE-PISA, 2012 ). Consequently, we can identify a socio-economic map showing the distribution of young people with a serious deficiency in the fundamental skills needed to grow and work in the world, to which we can also add a map of early school leavers.

According to UNESCO (1972) , educational wastage is the combination of repeated grades and early school leaving. In Italy, this phenomenon reaches alarming levels: in 2014, the “Educational Wastage” Dossier complied by Ministry of Education, University and Research [MIUR] (2014) observed the presence of almost three million young people who did not complete upper secondary education. In 2015, Italy reduced the rate of early school leavers, although the percentage was still higher than the EU average ( Istat, 2015 ). Over time, experts have highlighted different causes for educational wastage. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, they focused especially on its socio-economic factors . In the ‘80s, they additionally considered some of the students’ subjective dimensions . Over the same period, researchers began studying the relational dimension concerning students and teachers: increased attention was paid to classroom management styles, to the active or passive role of the students, and to the language used in the educational environment ( Batini and Bartolucci, 2016 ). If we take this relational standpoint, we cannot speak of “wastage” in the singular, but rather of “wastages,” plural ( Perone, 2006 ), or of a wasteful system: the situation does not concern only those who leave school entirely, but also those who attend without learning, as in the case of in-school drop-outs ( Solomon, 1989 ). The waste is not limited to the potential of students: it also extends to the work of teachers and to school equipment ( Brimer and Pauli, 1971 ). Contributions from psychoanalysis, which study affective/emotional dynamics, processes of symbolization in inter-generational relationships, and relationships with institutions, belong to the same perspective ( Blandino and Granieri, 1995 ). Depending on the different theoretical approaches, a succession of interventions aimed at strengthening teaching have been employed over the years, for example through the repetition and simplification of the material being taught, as well as interventions aimed at motivating and re-motivating students. There have also been interventions aimed at improving the quality of the educational relationship , which encompassed a variety of the teacher’s relational skills, e.g., their emotional skills ( Nouwen et al., 2016 ; Molloy Elreda et al., 2019 ). Fewer studies have focused on the importance of developing resilience in teachers if they are, in turn, to foster this trait in students ( Bobek, 2002 ; Henderson and Milstein, 2003 ), even though resilience as a personal characteristic has been studied extensively in at-risk students ( McMillan and Reed, 1994 ; Johnson, 1997 ; Aronson, 2001 ). Day and Gu (2014) have cogently argued that “efforts to increase the quality of teaching and raise standards of learning and achievement for all pupils must focus on efforts to build, sustain and renew teacher resilience, and that these efforts must take place in initial teacher training” (p. 22).

The Work of the Association MdS to Contain Educational Wastage

The non-profit Association Maestri di Strada (MdS) was born in Naples in 2003 with the Chance Project, a second chance school for drop-outs, recognized as an “activity of excellence” by the European Union: MdS carries out complex socio-educational interventions inside and outside suburban schools, in order to prevent educational wastage and to promote social inclusion ( De Rosa et al., 2017 ). In the last 10 years, in line with several European approaches to reduce early school leaving ( Nouwen et al., 2016 ), MdS has chosen to work especially in schools in the eastern suburbs of Naples: they support teachers in the classroom and share different methods with them.

The environment of the eastern suburbs of Naples is characterized by social and economic marginality, unemployment, environmental neglect, a lack of public services, the widespread presence of organized crime, and educational wastage. In this context, teachers feel ineffective or powerless, and as if their job has lost meaning. It is not easy to work in these environments for MdS, either. The relationships with children, teenagers, families and teachers, all charged with problems and distress, are trying. It is just as stressful to connect with educational or political institutions, because it entails facing different forms of inflexibility. MdS takes care of the well-being of its partners and encourages their professional reflection , communication and cooperation through observations, narrations, and group meetings. Observation ( McMahon and Farnfield, 2010 ) is employed both for on-field educational activities and for reflective group meetings. All partners are also asked to write narrations about their work throughout the year. The multi-vision group ( Parrello et al., 2019b ) is the method chosen to support professional reflection: it was inspired by the Balint group ( Van Roy et al., 2015 ). The results of the Association’s efforts are encouraging: at the end of each school year, 90% of the kids they care for stay in school and succeed in moving on to the next school year ( Parrello, 2018 ).

Spending considerable time inside of schools, MdS partners become witnesses of the hardships of many teachers and suggest activities to support their work. For these reasons, MdS has chosen to offer teachers professional social support, to support their resilience, and to actively engage them through T-PAR methodology.

From the literature, it is known that teachers need social support, both internal and external to the school system. In fact, good professional relationships have a positive effect on well-being, sense of engagement, empowerment, self-efficacy and the resilience of teachers in their work ( Betoret, 2006 ; Halbesleben, 2006 ; Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2009 ; Soini et al., 2010 ; Brouwers et al., 2011 ; Avanzi et al., 2018 ). The resilience of teachers is linked to the social support that they receive from colleagues, family and other professionals ( Stanford, 2001 ), as well as to a “relevant, rigorous and responsive” education ( Cefai and Cavioni, 2014 , p. 144). The T-PAR methodology is a form of teachers’ education via Action Research.

Action Research (AR), as it is known, is an investigation model whose main aim is to improve the future skills and activities of the researcher, rather than produce theoretical knowledge ( Lewin, 1948 ). In the ‘50s, Corey (1953) promoted AR in the United States in the field of education, gaining great cooperation from school districts and teachers: his method was later called Cooperative Action Research . At the end of the ‘60s, an international network of researchers created Participatory Action Research (PAR) in order to tackle various problems with disadvantaged members of society ( Susman and Evered, 1978 ; Hall, 1992 ; Fals-Borda, 2001 ; Kidd and Kral, 2005 ; Arcidiacono et al., 2016 ). McTaggart (1997) explains that the dual objective of PAR is, on the one hand, to intervene in the situation being researched, and, on the other, to change the researchers themselves, activating in them a process of transformation that will make them agents of their own changes. From then on, PAR has been applied to many fields and disciplines, and it has assumed a much more critical position with respect to the broader field of AR, given its specific objective of dealing with power imbalances that generate social and personal distress ( Arcidiacono et al., 2017 ; Stapleton, 2018 ). For this reason, the PAR method is thought to be particularly suited to the educational field (T-PAR), where power issues are a constant influence ( Jacobs, 2016 ). Hooks (1984) discusses the power issue found in traditional educational environments: there are power discrepancies between teacher and pupil that start with teachers grading their pupils; however, this power can be used in non-coercive ways to improve the learning process.

Teachers often perceive a divide between theory and practice, between being able to think and having to do, whereas in PAR, knowledge is built by the people involved in the research process, in a non-hierarchical, democratic environment which ultimately constitutes “a social enterprise” ( Savin-Baden and Wimpenny, 2007 ) that produces “a contextual knowledge” ( Pine, 2009 , p. 31). PAR can change both teachers and students, and also their mutual perception ( Brydon-Miller and Maguire, 2009 ) and the emotions dominating the classroom ( Hooks, 1994 ). Moreover, according to multiple authors, in-classroom research is in itself a way to promote self-reflection ( Schön, 1983 ; Alber and Nelson, 2002 ), improving the teachers’ self-awareness, their control over their emotions and actions and over their own power, thereby reducing the pressure created by the context and finding resources where they previously only saw limits. More specifically, reflection – as part of the PAR cycle – is a meta-cognitive process that consists of exploring personal beliefs, thoughts and actions in a deliberate, autobiographical, and critical way ( Marcosa et al., 2009 ). Thus, PAR is considered to be a powerful form of professional development for teachers ( Johnson and Button, 2000 ), who are nevertheless usually reluctant to participate in action research: they do not comprehend how research could improve their work, because they lack the knowledge and training to see the connection between theory and practice ( Bondy, 2001 ).

The PAR cycle is composed of the following phases: planning, action, reflection and evaluation. Some common characteristics of PARs are active participation, open-ended objectives and high levels of commitment ( Greenwood et al., 1993 ; Morales, 2016 ). Multiple authors report the following various benefits of action research, which often go beyond the goal of the research project: improved teaching practice; enhanced collegiality; feelings of closeness to one another after working on a group research project; and becoming more reflective about the improvement of student performance ( Glanz, 2003 ).

Materials and Methods

In the academic year 2017–2018, MdS carried out the T-PAR project “Crossing Educational Boundaries”: the title is a reference to the importance of making education “cross the boundary” and leave the outskirts of society’s interests; it also alludes to the necessity of going beyond physical and mental limits, thus letting professionals, disciplines and methods meet in a free and creative way.

These are the research questions that gave life to the project: do the teachers have resources to analyze the problematic situations they are immersed in and to build improvement strategies? Would a professional social support reinforce their resilience?

The objective was the following: to actively engage the teachers in order to generate hypotheses concerning the causes of educational wastage in their schools, and to work with them to plan new methods to lessen the problem.

Participants

The schools that participated are all located in the suburbs and have a high rate of educational wastage. 12 suburban schools participated, with about 200 teachers and 20 classes from different Italian cities: two metropolises (Rome, Naples), two medium-sized cities (Bologna, Florence), and two smaller provincial towns from the North and South (Rozzano, Sciacca). This paper will describe the first phase of the PAR project carried out in the first three participating schools – Rome, Bologna, Naples.

The School in Rome

Rome is a metropolis (population of city and provinces: almost four and a half million) in central Italy. The school that participated in the project is a Higher Technical Institute in a suburban area. The students are between 14 and 18 years old, and many do not obtain a high school diploma. Here, 15 teachers participated in the PAR.

The School in Bologna

Bologna is a medium-sized city (population of city and province: about 1 million) of Northern Italy. The school that participated in the project is a Lower Secondary School (students between 12 and 14 years old) located in a suburban area, where the teenagers attending are mostly children of immigrants. A few years ago, some Italian students also returned to the school, because the principal added a class with a curriculum using high-technology teaching. However, the result was a clear-cut separation between Italians and foreigners. Here, 14 teachers participated in the PAR.

The School in Naples

Naples is a metropolis (population of city and province: about 3 million) in Southern Italy. Its suburbs are known for the high rate of educational wastage, unemployment and organized crime. In this Lower Secondary School, teachers have been cooperating with MdS for some time, putting on workshops and accepting the help of its partners. This school’s biggest problem is educational wastage in its many forms. Here, 10 teachers participated in the PAR.

The project was presented to the school principals and teachers. MdS offered a preliminary time schedule, a team of the Association’s partners (pedagogues, psychologists, educators, workshop teachers, observers) and a “menu” of possible tools. The five phases of PAR have been planned and implemented, albeit in a specific way, in each school:

1. Planning: construction of a space – guided by a conductor of MdS – in which the teachers can meet to share experiences, think and plan freely.

2. Action: realization of educational actions (for example laboratories) guided by teachers with the support of MdS.

3. Reflection: construction of a space – guided by a conductor of MdS – to reflect together on the actions carried out.

4. Assessment: collection and analysis of materials useful for evaluating the path of PAR (for example observation reports); common discussion of the results.

5. New planning: formation of a group of teachers that, in collaboration with MdS, proposes prototypes of intervention.

In agreement with the teachers, all activities were observed by psychologists from the MdS Association, in the non-participant role ( Ahola and Lucas, 1981 ). Observation is used regularly by researchers to collect data in classrooms ( Kawulich, 2012 ). However, observing is not a natural ability, but rather the result of precise training: for this reason trained psychologists who belong to the association have been involved.

Observers were presented to teachers and students, explaining their role. They took notes during the observation. They had the task of observing freely, with particular regard to the activities and interactions that occurred in the setting: the non-verbal and verbal behaviors, and the conversations between participants.

However, the observer, whether he is aware of it or not, is a deformed and deforming mirror: some consider subjectivity as a risk to be avoided if possible because it is a source of error, while others see it as a resource, as a further component of cognition and therefore they consider subjectivity a main path to knowledge ( McMahon and Farnfield, 2010 ). To limit the threshold of subjectivity inherent in observation, they were asked to use denotative and descriptive language, referring to precise (not generic) situations. They were also asked to include direct speech in the written notes. They were asked to insert their own comments and report them as such.

Observation reports were read out to research participants after the activities. They were then analyzed in a descriptive and content-oriented way in order to report processes and outcomes resulting from phase 1–3 in each school. Then, the reports related to phases 1–3 were analyzed in a lexical-oriented perspective in order to be used as an input for discussion in phase 4.

In particular, the corpus composed of all reports from the three schools was subjected to textual analysis by ALCESTE software (Analyse des Lexèmes Co-occurrents dans les Énoncés d’un TExte) ( Reinert, 1990 , 1993 ). The adoption of computerized textual analysis software enables researchers to overcome several limitations that are likely to occur in the manual coding of text: the time-consuming nature of manual coding, the potential for rater bias, the reliability and accuracy of coding as a result of researcher fatigue, and the practical difficulties of coding large data sets ( Illia et al., 2012 ). It is noted that, on the other hand, this type of analysis reduces the complexity of the meaning making: the data obtained therefore only represent some aspects of this complexity. In particular, we chose the software ALCESTE (Analyse des Lexèmes Co-occurrents dans les Énoncés d’un TExte) ( Reinert, 1990 , 1993 ): it is an instrument of statistical analysis that explores the inner organization of a text through the concurrent presence or co-occurrence of several content words . The “positioning text analysis” makes it possible to make sense of a word based on its natural context. It is based on the fundamental assumption that “since the meaning of words is learned through reading and hearing them used in particular combinations, word co-occurrence is a suitable basis for representing meaning” ( Ocasio and Joseph, 2005 , p. 165). Discourse is conceived as a semantic space, and a word is considered based on the position it takes in this space. The use of ALCESTE is advisable for analyzing a set of data using a non-predefined dictionary which scans the entire text so as to include idiomatic language.

ALCESTE develops a spreadsheet with the list of words in the columns, and pieces of text or extracts in the rows (a typical extract – not necessarily corresponding to a set of sentences – is between 16 and 19 words long) and, based on this, produces a two-by-two matrix to identify classes of discourse which are very different. In technical terms this procedure is called “ hierarchical downward classification of words .” The software compares how words co-occur or do not co-occur in each extract and develops a classification tree that is descendant, since the whole text is divided first into two large classes of discourse, each with the most differentiated use of words. Then, for each of these two parts, the software again divides the text into two further parts, which are differentiated, certainly, but less so than the first ones. The software continues this classification until the differences among classes of discourse become too small to be significant. At this third step, the researcher does not yet interpret the results. Instead, next, ALCESTE begins co-occurrence analysis by benchmarking different parts of the text. This benchmark is developed two times, which provides a measure of stability for the comparison (stability index). Thus, here one gets a measure of stability for the descending hierarchical classification. A good measure of stability is said to have been obtained when about 70% 1 of the text is classified in the same way twice ( Illia et al., 2012 ). Only in the second phase of its process does ALCESTE analyze each part of the text separately. This has the added value of managing the potential for human bias in the interpretation of the results: ALCESTE does not impose an interpretation according to which one part of the text is considered different from or similar to others. The researcher analyses quotations only once they have been identified as being either typical or atypical of a specific co-use of words. To put it another way, when the researcher analyses the quotations, s/he does so based on a report of how the language in each quotation is different from or similar to the language used in other quotations. Thus, the human coding is guided by an informative report, and human bias is controlled ( Illia et al., 2012 ). The researcher receives a number of written or visual descriptions of the results. All of the elements listed below have been analyzed by the refinement process described above, until the meaning of each class is clear and the researcher gains a comprehensive understanding of how and why each cluster is distinct. This is the phase in which human interpretation takes place. In the classification tree or dendrogram, composed of macro-areas divided into stable clusters which correspond to lexical universes or “mental rooms” which the authors of the texts “enter” ( Reinert, 1993 ), the distance trees visually represent the descending hierarchical classification. Each cluster is characterized by a specific vocabulary , composed of words which recur significantly more frequently inside the corpus, and by a set of elementary context units ( ECUs ), obtained through the analysis of punctuation and length (fundamental statistical units for the software). In each cluster, the frequency of words is only a secondary parameter, as frequency is relevant only when it reveals that there is a more frequent use of certain words in a specific part of the text, compared with another part of the text. This is indicated by the Chi 2 for words in a class. The value of Chi 2 is not absolute; it can only be computed within each class. All words listed in the report are relevant for interpretation, even considering that a high positive Chi 2 indicates words that co-occur the most in a cluster ( Illia et al., 2012 ).

We will describe the phases of the PAR cycle carried out in each school: planning, action, and reflection. The fourth phase (evaluation) is common to all three schools.

Phase 1: Planning

The teachers decided to form discussion groups about educational wastage that also included the students, followed by workshops and, finally, new discussion groups to discuss the workshops. During the first meeting, the teachers started by describing the negative characteristics of their pupils: unenthusiastic, passive, inept, uninterested, lazy, dull, distracted, flat. The students were also described in the following terms: they have no passion, they don’t care about politics, they have no interests; they don’t know how to communicate with each other; they are atomized, isolated, and divided; they don’t form a group; they don’t know how to communicate with teachers; they have no perception of their limits and resources; they have an inaccurate perception of (the institution’s) space and time; they are often compliant with the teachers, but not genuine; they do not follow the rules. It is not clear whether the characteristics the teachers discussed are subjective or context-bound. Only one teacher said: “it’s weird; they shouldn’t be bored at that age.” Teachers also formulated some interesting theories on the learning/teaching process, along the lines of the following: there is no learning without relationships, but it’s difficult here; if a student has specific learning difficulties, the family has to be involved, although they don’t usually cooperate; the clever ones have to leave, or they’ll waste away. The desire/goal of the teachers is to create an environment of trust and an alliance with the pupils. They listed the educational strategies employed thus far, to no avail, and the obstacles they met. Then they recounted a fragment of daily life in the classroom: “During an hour of substitution, someone in class throws a shoe in the air. The teacher asks who’s to blame for this violent and irresponsible gesture. The class joins forces to keep the secret.” In the follow-up discussion, the teachers said they fear the aggressiveness of their students, and for this reason they try to avoid any possible conflict. But one teacher said, “In my opinion, there is no education without conflict.” Then, they discussed the chance offered by the project to become equipped with a tool for observation and reflection in order to understand why the strategies used thus far do not work.

Later on, the teachers introduced the project to their students. The first meeting with the students followed, where students described themselves as suburban teenagers: as suburban teenagers, different from city center teens. As they said, in the suburbs, you become autonomous early and you start working early; if you leave the suburbs, you’re in trouble; the suburbs are freedom and the center is a cage, but it’s also true that the suburbs have no rules and are out of control, while the center is protected and follows the rules. They also illustrated theories explaining what is wrong with school, according to them: they want privacy, while adults ask questions and then judge and punish them. Because of this, they hide from the adults; sometimes they pretend to be interested, but it’s difficult to have a real dialogue between students and teachers, because the distance is too great. They discussed at length the fact that the teachers address the students with “tu” (informal language) while demanding to be addressed with “lei” (formal language). The teachers actively underline their institutional role. One of the teachers does so aggressively, sarcastically making fun of the student who is talking. The students’ desire to not be treated like children and to have more independence and be less controlled emerged. Then came the recounting of a moment of daily school life: “the other day, two girls beat each other up in the hallway. The teachers decided to add more controlling rules applying to all students”; and “all field trips have been cancelled for lack of trust in the students, who are all considered irresponsible.” During the discussion, the students said that the teachers forget what it means to be teenagers and don’t give second chances, and that it would be good to have teachers who really care about the students and give second chances.

The next meeting began in the midst of many organizational hindrances. The atmosphere was chaotic. Nevertheless, the teachers managed to discuss the issues raised by the students; some teachers critiqued the lack of strictness of present-day schooling, by now “reduced to a playroom.” Afterward, they started planning some experimental educational approaches, trying to answer the question: why is it that not even workshop-based pedagogy is successful with students?

Teachers then decided to come up with the following: a workshop on aggressiveness and rules of conduct during law classes; a workshop on the use of technology during English classes; and a lesson “that allows the students to take time to make mistakes and correct them” during maths classes.

During the first meeting, the teachers started by describing the negative characteristics of their pupils: they are difficult, suburban kids who are left out, disowned and different. They communicate through physical violence, speak a different language, and have no self-awareness, nor awareness of time and space, but are receptive, sometimes accepting the teachers’ assistance, letting themselves be guided. Additionally, they immediately pointed out the school’s strengths: open and democratic management, good relationships between colleagues, the school’s participation in supply requests, funding, and services, new teachers being seen as a resource, and the welcoming and protective environment. The school’s problems then followed: too many students drop out of school in the transition to high school, there is aggressiveness in the classroom, and some teachers are insulted. Afterward, they recounted an educational experience carried out the previous year: the teachers offered the students a workshop about Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies . The goal was to make the students understand the importance of rules. Their evaluations of the experiment emerged during the discussion: what caused the failure of the workshop were language issues, infantility, and the pace of learning differing between pupils.

They also recounted an experience with the students’ parents: the Women’s School, aimed at teaching Italian to immigrant mothers. During the discussion, many doubts emerged over the usefulness of involving the parents in this way.

Finally, they described another educational experience: a workshop on the topic of violence against women, based on newspaper readings. During the discussion, the teachers reported to have observed the presence of widespread misogyny and of an alarming aggressive tendency in the classroom.

The teachers proposed to investigate the causes behind the academic failure and school wastage of their pupils, distributing questionnaires or collecting information post hoc . But the methodological proposal, which had initially excited the teachers, was then abandoned. Later on, the teachers decided to introduce interdisciplinary workshops: a workshop about the telegraph, as it is the ancestor of modern immediate, long-distance communication; a workshop teaching how to plan a trip to a foreign country; and a workshop teaching how to build polygons using plastic straws.

As already mentioned, in this Lower Secondary School, teachers have been cooperating with MdS for some time, offering workshops and accepting the help of its partners. Many times MdS has offered the school a reflective space for teachers, but opposition has been considerable. This school’s manifest problem is educational wastage in its many forms.

For the “Crossing Educational Boundaries” Project, we decided to observe some already-existing workshops, characterized by interactive methods and by the presence of a teacher, an expert on the subject, and an educator: a buoyancy workshop; a workshop about food composition; and a workshop about the food pyramid.

Phase 2: Action

Because of some new organizational issues, only one workshop was carried out: the one about aggression and rules of conduct, which used triggering images and created spaces of narration and discussion. The workshop was managed by an MdS pedagogue, but the teachers were present too. Some photos were projected: a picture of wolves baring their teeth but not attacking, and another of wolves playing. A debate arose among the students about the reasons behind animal and human aggression, about strategies to restrain it and control emotions, and about civilization and friendship.

All workshops were carried out and observed: the observer noticed that during the workshop involving learning the basics of the Morse alphabet, the students were divided into groups placed in different classrooms in order to try and communicate from a distance, and as a result many students were bored and some did not participate at all. During the workshop that involved a division into groups in order to use a computer to buy tickets, book accommodations, and plan museum visits and nights out, many conflicts erupted between single students or subgroups for the use of the computer, and some students did not participate at all. During the workshop consisting of building different polygons following the teacher’s instructions, using straws of different lengths, only one small group participated, while many students remained inactive.

The first workshop began in a situation of confusion that caused a strong emotional reaction of discouragement in the teacher: “I can’t do it anymore! I wasn’t trained to educate, it’s not my job! I’m sick and tired of shouldering the education of other people’s children!” The chaos continued: some pupils stood up and wandered around, some exited the classroom, some strangers entered, one threw pencils, another isolated himself, some provoked others. According to the observer, the teacher became cynical with some students, mocking them for their physical features or for their mistakes. Then she managed to restore calm, and demanded loudly for the approval of the MdS partners: “Here, see, I shut them up.” In the second workshop, we found the same chaos, but here one of the students intervened to restore calm: “Shut up, we can’t work like this!” After a while, the chaos started again: some left the class, some entered, some joked around, some threw things, some ate, some used mobile phones, some ruined the others’ project. At this point, the teacher had a strong emotional reaction and started screaming in turn. The observer noted that when no adult in the classroom decides to stop the actions and talk to the students, chaos grows and the adults explode; when the educator intervenes by stopping the action and listening to the kids, calm is restored.

Phase 3: Reflection

During the final discussion, the teachers expressed their opinions: the workshop worked, but they don’t have time to do things like that, because they have to follow the syllabus. A single teacher says: “Actually, we could, we are free to choose.”

At the end of the workshops in this school, the teachers entrusted the reflection to their students. The observer commented that “they seem to struggle to talk about what they feel more than what they know.” Finally, the students said that working in groups is at the same time more tiring and more fun, and that they lacked the time to finish the workshop because the bell rang. A young girl said that today she felt good at school, she felt like she was at home.

After many organizational issues, the teachers suspended the research activities.

A discussion meeting is held with teachers and students, in order to reflect on the workshops’ progress: the teachers decided to assign some students the task of cooperating and maintaining order, so that they are responsible. A third workshop started peacefully, then the usual chaos began. The teacher left the class often. This time, the educator took it upon herself to talk to the kids to make them reflect on what was happening and on a sense of the rules for working in a group.

A new discussion with the students followed, where they discussed their own self-representation: some kids said that they are seen as “monsters,” and that it’s true they are “monsters,” and that is why there is an observer.

During the final discussion, the teachers suggested to pupils that they keep diaries about what happens in class, to discuss them together later, but the kids say they don’t want to write negative things about their classmates. During the last group discussion, the students gave their evaluation of the workshop activities they took part in, using words like: nice, bad, tranquillity, serenity, happiness, relaxing. A girl adds: “I felt good, like at home.”

In this school as well, after some organizational issues, the research activities were temporarily suspended.

Phase 4: Evaluation

Subsequently, MdS decided – together with the teachers – to entrust a team of external researchers with the textual analysis of the corpus composed of the observational reports. The initial results have been discussed with the teachers from all schools on the occasion of the International Convention “Crossing Educational Boundaries,” held in Naples in October 2017.

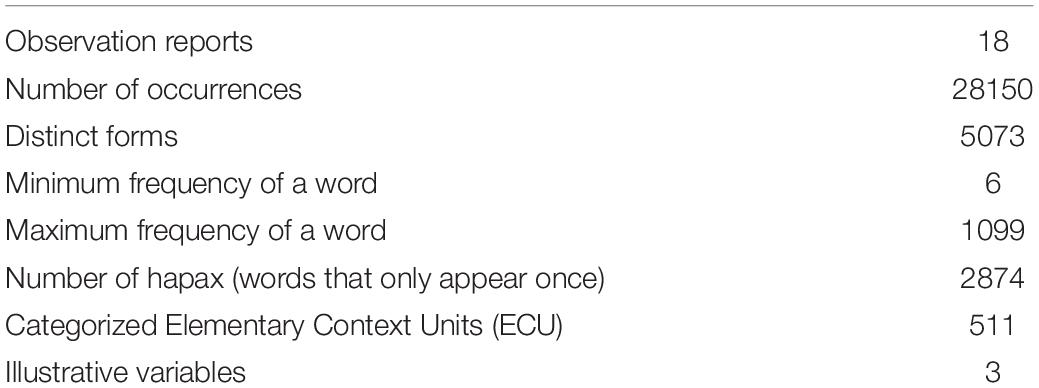

The corpus – composed of 18 observational reports – was pre-processed, as it underwent disambiguation and partial lemmatization . Each text was marked by three illustrative variables : city (Roma, Bologna, Napoli), type of school (Lower or Upper Secondary), and type of activity (discussion or workshop). The analyzed characteristics of the textual corpus are illustrated in Table 1 .

Table 1. Textual corpus: quantitative characteristics.

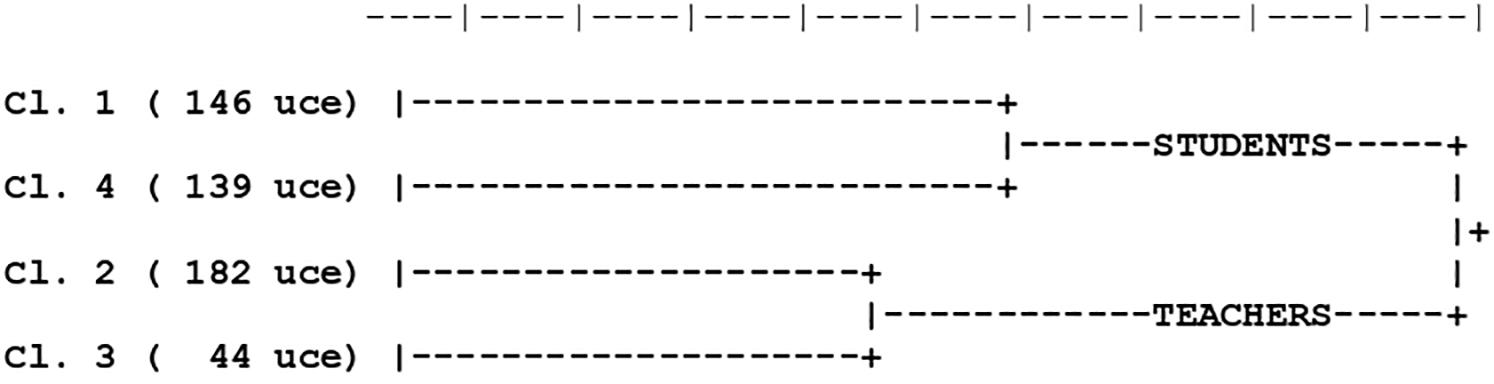

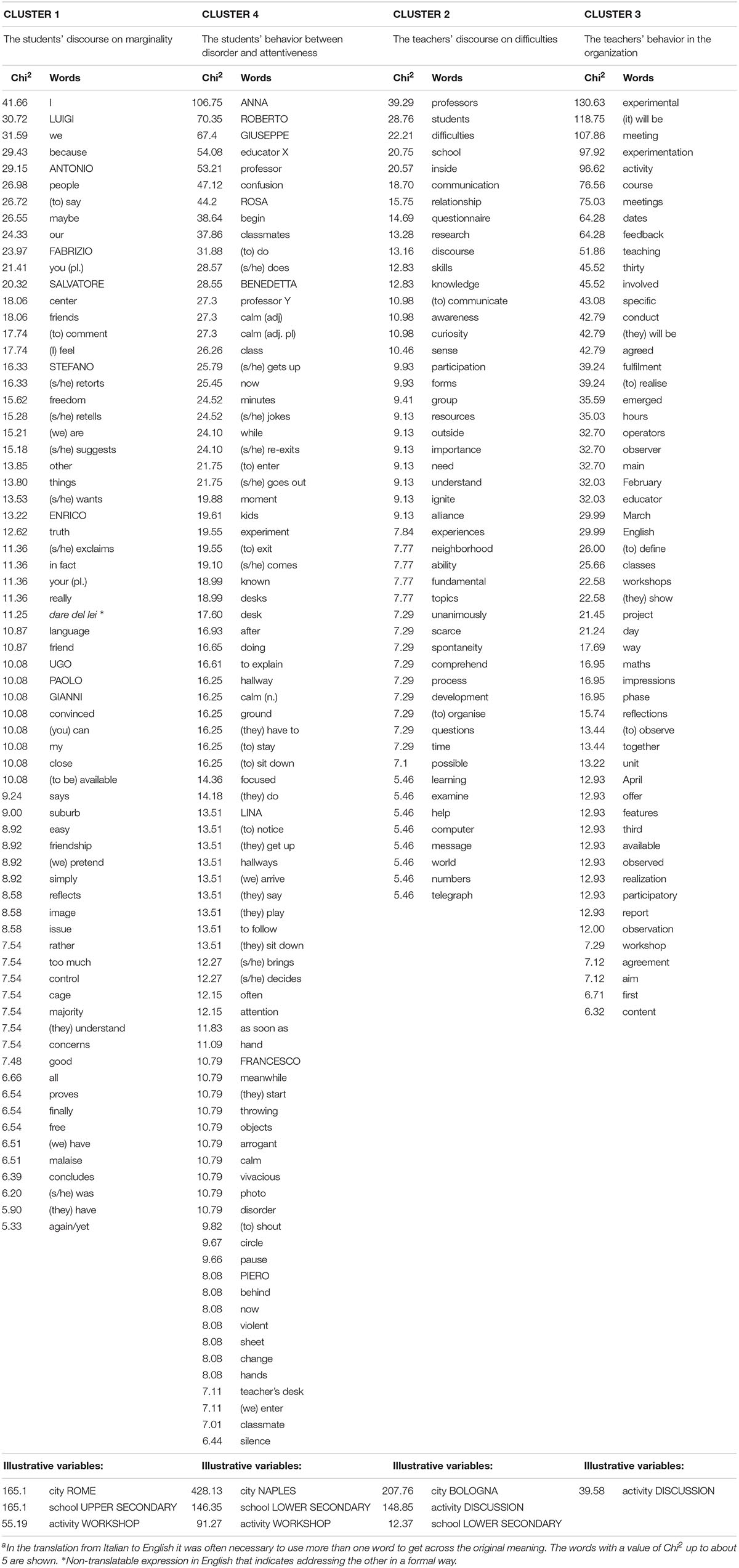

The analysis classified 511 ECUs out of the 732 detected (stability index 69.81%), divided in two macro-areas (A. Students; B. Teachers) and four stable clusters, as shown in the dendrogram of ECU classification (see Figure 1 ). For each cluster, the number and percentage of ECUs were indicated (see Table 2 ). Each cluster was assigned a thematic label on the basis of the specific vocabularies and of the most significant ECUs . Specific vocabularies and illustrative variables of clusters are illustrated in Table 2 . 2

Figure 1. Descending hierarchical classification.

Table 2. Clusters: specific vocabularies a and illustrative variables.

I Macro-Area

The first macro-area identified by ALCESTE contains clusters 1 and 4, regarding, respectively, the words and actions of the students.

Cluster 1 – The students’ discourse on marginality (146 ECUs) (28.57%)