The Current Education Issues in the Philippines — and How Childhope Rises to the Challenge

- August 25, 2021

Even before COVID-19 struck and caused problems for millions of families, the country’s financial status is one of the top factors that add to the growing education issues in the Philippines. Furthermore, more children, youth, and adults can’t get a leg up and are thus left behind due to unfair access to learning.

Moving forward, such issues can lead to worse long-term effects. Now, we’ll delve deep into the current status and how we can take part in social efforts to help fight these key concerns of our country.

Crisis in Philippine Education: How is It Really?

Filipinos from rich households or living in cities and developed towns have more access to private schools. In contrast, less favored groups are more bound to deal with lack of classrooms, teachers, and means to sustain topnotch learning.

A 2018 study found that a sample number of 15-year-old Filipino students ranked last in reading comprehension out of 79 countries . They also ranked 78 th in science and math. One key insight from this study is it implies those tested mostly came from public schools. Hence, the crisis also lies in the fact that a lot of Filipinos can’t read or do simple math.

Indeed, it’s clear that there is a class divide between rich and poor students in the country. Though this is the case, less developed states can focus on learning if it’s covered in their top concerns. However, the Philippines doesn’t invest on topnotch learning as compared to its neighbor countries. In fact, many public schools lack computers and other tools despite the digital age. Further, a shortfall in the number of public school teachers is also one of the top issues in the country due to their being among the lowest-paid state workers. Aside from that, more than 3 million children, youth, and adults remain unenrolled since the school shutdown.

It goes without saying that having this constant crisis has its long-term effects. These include mis- and disinformation, poor decision-making, and other social concerns.

The Education System in the Philippines

Due to COVID-19, education issues in the Philippines have increased and received new challenges that worsened the current state of the country. With the sudden events brought about by the health crisis, distance learning modes via the internet or TV broadcasts were ordered. Further, a blended learning program was launched in October 2020, which involves online classes, printouts, and lessons broadcast on TV and social platforms. Thus, the new learning pathways rely on students and teachers having access to the internet.

This yet brings another issue in the current system. Millions of Filipinos don’t have access to computers and other digital tools at home to make their blended learning worthwhile. Hence, the value of tech in learning affects many students. Parents’ and guardians’ top concerns with this are:

- Money for mobile load

- Lack of gadget

- Poor internet signal

- Students’ struggle to focus and learn online

- Parents’ lack of knowledge of their kids’ lessons

It’s key to note that equipped schools have more chances to use various ways to deal with the new concerns for remote learning. This further shows the contrasts in resources and training for both K-12 and tertiary level both for private and public schools.

One more thing that can happen is that schools may not be able to impart the most basic skills needed. To add, the current status can affect how tertiary education aims to impart the respect for and duty to knowledge and critical outlook. Before, teachers handled 40 to 60 students. With the current online setup, the quality of learning can be compromised if the class reaches 70 to 80 students.

Data on Students that Have Missed School due to COVID-19

Of the world’s student population, 89% or 1.52 billion are the children and youth out of school due to COVID-19 closures. In the Philippines, close to 4 million students were not able to enroll for this school year, as per the DepEd. With this, the number of out-of-school youth (OSY) continues to grow, making it a serious issue needing to be checked to avoid worse problems in the long run.

List of Issues When it Comes to the Philippines’ Education System

For a brief rundown, let’s list the top education issues in the Philippines:

- Quality – The results of the 2014 National Achievement Test (NAT) and the National Career Assessment Examination (NCAE) show that there had been a drop in the status of primary and secondary education.

- Budget – The country remains to have one of the lowest budget allotments to learning among ASEAN countries.

- Cost – There still is a big contrast in learning efforts across various social groups due to the issue of money—having education as a status symbol.

- OSY – The growing rate of OSY becomes daunting due to the adverse effects of COVID-19.

- Mismatch – There is a large sum of people who are jobless or underpaid due to a large mismatch between training and actual jobs.

- Social divide – There is no fair learning access in the country.

- Lack of resources – Large-scale shortfalls in classrooms, teachers, and other tools to sustain sound learning also make up a big issue.

All these add to the big picture of the current system’s growing concerns. Being informed with these is a great first step to know where we can come in and help in our own ways. Before we talk about how you can take part in various efforts to help address these issues, let’s first talk about what quality education is and how we can achieve it.

What Quality Education Means

Now, how do we really define this? For VVOB , it is one that provides all learners with what they need to become economically productive that help lead them to holistic development and sustainable lifestyles. Further, it leads to peaceful and democratic societies and strengthens one’s well-being.

VVOB also lists its 6 dimensions:

- Contextualization and Relevance

- Child-friendly Teaching and Learning

- Sustainability

- Balanced Approach

- Learning Outcomes

Aside from these, it’s also key to set our vision to reach such standards. Read on!

Vision for a Quality Education

Of course, any country would want to build and keep a standard vision for its learning system: one that promotes cultural diversity; is free from bias; offers a safe space and respect for human rights; and forms traits, skills, and talent among others.

With the country’s efforts to address the growing concerns, one key program that is set to come out is the free required education from TESDA with efforts to focus on honing skills, including technical and vocational ones. Also, OSY will be covered in the grants of the CHED.

Students must not take learning for granted. In times of crises and sudden changes, having access to education should be valued. Aside from the fact that it is a main human right, it also impacts the other human rights that we have. Besides, the UN says that when learning systems break, having a sustained state will be far from happening.

How Childhope KalyEskwela Program Deals with Changes

The country rolled out its efforts to help respond to new and sudden changes in learning due to the effects of COVID-19 measures. Here are some of the key ones we can note:

- Continuous learning – Since the future of a state lies on how good the learning system is, the country’s vision for the youth is to adopt new learning paths despite the ongoing threat of COVID-19.

- Action plans – These include boosting the use of special funds to help schools make modules, worksheets, and study guides approved by the DepEd. Also, LGUs and schools can acquire digital tools to help learners as needed.

Now, even with the global health crisis, Childhope Philippines remains true to its cause to help street children:

- Mobile learning – The program provides topnotch access to street children to new learning methods such as non-formal education .

- Access to tools – This is to give out sets of school supplies to help street kids attend and be ready for their remote learning.

- Online learning sessions – These are about Skills for Life, Life Skill Life Goal Planning, Gender Sensitivity, Teenage Pregnancy and Adolescent Reproductive Health.

You may also check out our other programs and projects to see how we help street children fulfill their right to education . You can be a part of these efforts! Read on to know how.

Shed a Light of Hope for Street Children to Reach Their Dreams

Building a system that empowers the youth means helping them reach their full potential. During these times, they need aid from those who can help uphold the rights of the less privileged. These include kids in the streets and their right to attain quality education.

You may hold the power to change lives, one child at a time. Donate or volunteer , and help us help street kids learn and reach their dreams and bring a sense of hope and change toward a bright future. You may also contact us for more details. We’d love to hear from you!

With our aim to reach more people who can help, we’re also in social media! Check out our Facebook page to see latest news on our projects in force.

Subscribe to our Mailing List

©1989-2024 All Rights Reserved.

UNESCO and DepEd launch the 2020 Global Education Monitoring Report in the Philippines

MANILA, 25 November 2020. Along with government officials, international aid agencies, education and humanitarian experts, policymakers, teachers and learners, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the Department of Education (DepEd) launched the 2020 Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report on 25 November 2020 virtually.

With the theme “Inclusion and education: All means All,” the national launch was organized to increase awareness of the Report’s messages and recommendations on inclusion in education with a wider education community, with those working on humanitarian responses, and with government officials and policymakers. The event was broadcasted live on the official Facebook of UNESCO Jakarta and the Philippines’ Department of Education.

As part of its progress towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4)and its targets, the 2020 GEM Report ( https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373721 ) provides an in-depth analysis of key factors in exclusion of learners in education systems worldwide, such as background, identity and ability (i.e. gender, age, location, poverty, disability, ethnicity, indigeneity, language, religion, migration or displacement status, sexual orientation or gender identity expression, incarceration, beliefs and attitudes).

One of the numerous examples highlighted in the report is the gender-responsive basic education policy created by DepEd. The policy calls for an end to discrimination based on gender, sexual orientation, and gender identity by defining ways for education administrators and school leaders such as improving curricula and teacher education programmes with the content on bullying, discrimination, gender, sexuality and human rights.

The Report also identifies the heightening of exclusion during the COVID-19 pandemic, where it has shown that about 40% of low and lower-middle income countries have not supported disadvantaged learners during temporary school shutdown. The event featured speeches and presentations from experts on inclusion from both government and non-governmental organizations, policy makers and practitioners, including a message from UNESCO’s Global Champion of Inclusive Education, Ms Brina Kei Maxino, and performances by the world-renowned and 2009 UNESCO Artist for Peace, the Philippine Madrigal Singers.

The highlight of the event was the live discussion between DepEd Secretary, Professor Emeritus Leonor Magtolis-Briones, and the Director of UNESCO Jakarta, Dr Shahbaz Khan, as they explored the findings of the report and deliberated on issues such as inclusion and education and its implementation; adjustment on the school policies during Covid-19; a horizontal collaboration between government and non-government stakeholders; education budget and spending; grants for students; and, social programs to support education.

Alongside today’s publication, UNESCO GEM Report team has also launched a new website called Profiles Enhancing Education Reviews (PEER) that contains information on laws and policies concerning inclusion in education for every country in the world. According to UNESCO, PEER shows that although many countries still practice education segregation, which reinforces stereotyping, discrimination and alienation, some countries like the Philippines have already crafted education policies strong on inclusiveness that target vulnerable groups.

The 2020 Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report urges countries to focus on those left behind as schools reopen to foster more resilient and equal societies.

- Global Education Monitoring Report

Related items

- Education for sustainable development

- Country page: Philippines

- UNESCO Office in Jakarta and Regional Bureau for Science

- SDG: SDG 4 - Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all

- See more add

This article is related to the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals .

Other recent news

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

With Schools Closed, Covid-19 Deepens a Philippine Education Crisis

The country remains among the few that have not at least partially reopened, sparking worry in a place where many lack a computer or internet access.

By Jason Gutierrez and Dan Bilefsky

MANILA — As jubilant students across the globe trade in online learning for classrooms, millions of children in the Philippines are staying home for the second year in a row because of the pandemic, fanning concerns about a worsening education crisis in a country where access to the internet is uneven.

President Rodrigo Duterte has justified keeping elementary schools and high schools closed by arguing that students and their families need to be protected from the coronavirus. The Philippines has one of the lowest vaccination rates in Asia, with just 16 percent of its population fully inoculated, and Delta variant infections have surged in recent months.

That makes the Philippines, with its roughly 27 million students, one of only a handful of countries that has kept schools fully closed throughout the pandemic, joining Venezuela, according to UNICEF, the United Nations Agency for Children. Other countries that kept schools closed, like Bangladesh, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, have moved to reopen them.

“I cannot gamble on the health of the children,” Mr. Duterte said in June, rejecting recommendations by the health department to reopen schools.

The move — which has kept nearly 2,000 schools closed — has spawned a backlash among parents and students in a sprawling nation with endemic poverty. Many people, particularly in remote and rural areas, do not have access to a computer or the internet at home for online learning.

Iljon Roxas, a high school student stuck at home in Bacoor City, south of Manila, said the monotony of staring at a computer screen over the past year made it difficult to concentrate, and he yearned to return to a real classroom. The fun and joy of learning, he added, had evaporated.

“I miss a lot of things, like bonding with classmates during free time,” said Iljon, 16. “I also miss my teachers, believe it or not. Since last year we have been stuck in front of our screens — you listen, you tune out.”

The crisis in the Philippines comes as countries across the world, including the United States, have been grappling with one of the worst disruptions of public schooling in modern history. Governments have struggled to balance the imperative of health and safety with the public duty to educate children.

Some countries, like Britain, have taken an aggressive approach to keeping schools open, including from late spring into early summer, when the Delta variant surged. While many elementary school students and their teachers did not wear masks, the British government focused instead on other safety measures, such as rapid testing and widespread quarantining.

Where schools have been closed for a long time, such as the Philippines, education experts have expressed concerns that the pandemic has created a “lost generation” of students, buffeted by the limits of remote learning and by overstretched parents struggling to serve as surrogate physics and literature teachers.

Maritess Talic, 46, a mother of two, said she feared her children had barely learned anything during the past year. Ms. Talic, who works part time as a maid, said she and her husband, a construction worker, had scraped together about 5,000 pesos, or about $100, to buy a secondhand computer tablet to share with their children, ages 7 and 9.

But the family — which lives in Imus, a suburb south of Manila — does not have consistent internet access at home. They rely on prepaid internet cards that are constantly running out, sometimes in the middle of her children’s online classes, Ms. Talic said. She has also struggled to teach her children science and math with her limited schooling.

“It is very hard,” she said, adding that the children struggled to share one device. “We can’t even find enough money to pay our electricity bill sometimes, and now we have to also look for extra money to pay for internet cards.”

She said she understood the need to prioritize health ahead of keeping schools opened, but she feared for her children’s future. “The thing is, I don’t think they are learning at all,” she added. “The internet connection is just too slow sometimes.”

Even before the pandemic, the Philippines was facing an education crisis, with overcrowded classrooms, shoddy public school infrastructure and desperately low wages for teachers creating a teacher shortage.

A 2020 World Bank report said the country also suffered from a digital divide. In 2018, it said, about 57 percent of the Philippines’s roughly 23 million households did not have internet access. However, the government has since been working to narrow that gap. Manila City Mayor Francisco Domagoso , said in an interview that last year, City Hall had handed out 130,000 tablets for school children and some 11,000 laptops for teachers.

UNICEF said in an August study that the school closures were especially damaging for vulnerable children, already facing the challenges of poverty and inequality. It called for the phased reopening of schools in the country, starting in low-risk areas and with stringent safety protocols in place.

The school closures have had negative consequences for students, said Oyunsaikhan Dendevnorov , UNICEF’s representative in the Philippines. Students have fallen behind and reported mental distress. She also cited a heightened risk of drop outs, child labor and child marriage.

As remote classes resumed this week, Leonor Briones, the education secretary, sought to portray the electronic reopening as a success. She said that about 24 million children, from elementary school to high school, were enrolled in school. But she acknowledged that the enrollment figure included about two million fewer students than last year.

Regina Tolentino, deputy secretary general of the College Editors Guild of the Philippines, which represents college newspaper editors, said the government’s attempt to put a positive spin on the second year of shuttered schools was “delusional.”

With remote learning the only option, she said, poor students were being forced to spend money on computers and internet cards rather than on basic necessities like food. “The government must hear students out and uphold their basic rights to education even during the pandemic,” she said.

But leading doctors and health experts said that, while opening schools was an important aim, health and safety needed to be prioritized.

They pointed out that just over 14 million people in the Philippines were fully vaccinated, well below the government’s initial target of 70 million by the end of the year. Some hospitals were filled to capacity, and scenes of patients receiving oxygen in parking lots had become commonplace.

Dr. Anthony Leachon, a prominent public health expert who was a member of the government’s Covid-19 advisory panel, called for the vaccination of 12 to 17 year-olds to be fast-tracked to help clear the way for schools to be reopened.

“It’s dangerous,” he said, “to reopen schools with the Delta variant strains at the moment.”

Dan Bilefsky is a Canada correspondent for The New York Times, based in Montreal. He was previously based in London, Paris, Prague and New York. He is author of the book "The Last Job," about a gang of aging English thieves called "The Bad Grandpas." More about Dan Bilefsky

- High contrast

- OUR REPRESENTATIVE

- WORK FOR UNICEF

- NATIONAL AMBASSADORS

- PRESS CENTRE

Search UNICEF

More to explore.

- Article (17)

- Campaign (1)

- In other news (1)

- Photo essay (1)

- Press release (24)

- Programme (1)

- Remarks (1)

- Statement (4)

- East Asia and the Pacific (1)

- Philippines (52)

- Republic of Korea (1)

Upholding the rights of every Bangsamoro child

Education Factsheet

Development of a Socio-Emotional Skills Assessment in the Philippines

Support Multigrade Schools with Digital Technology

How daycare workers strengthen the Philippines’ human capital

Fathers, we play a critical role in our child's first years of learning

Investing in day care workers is an investment in the future -UNICEF

Mga Maling Akala Tungkol sa Pag-aaral sa Child Development Center

Changing lives through education

Peace builds the future

A teacher by heart

Seven Hopes on the First Day of Classes

- Philippines

The Philippines Still Hasn’t Fully Reopened Its Schools Because of COVID-19. What Is This Doing to Children?

I f 17-year-old Ruzel Delaroso needs to ask her teacher a question, she can’t simply raise her hand, much less fire off an email from the kitchen table. She has to leave the modest shack that her family calls home in Januiay, a farming town in the central Philippines, and head to an area of dense shrubbery, a 10-minute walk away. There, if she’s lucky, she can pick up a phone signal and finally ask about the math problem in the self-learning materials her mother picked up from school.

“We’re so used to our teachers always being around,” Delaroso tells TIME via the same temperamental phone connection. “But now it’s harder to communicate with them.”

Her school, Calmay National High School, is among the tens of thousands of Philippine public schools shuttered since March 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, and Delaroso is one of 1.6 billion children affected by worldwide school closures, according to a UNESCO estimate.

But while other countries have taken the opportunity to resume in-person classes, the Philippines has lagged behind. After 20 months of pandemic prevention measures, amounting to one of the world’s longest lockdowns , only 5,000 students, in just over 100 public schools, have been allowed to go back to class in a two-month trial program—a tiny fraction of the 27 million public school students who enrolled this year. The Philippines must be one of a very few countries, if not the only country, to remain so reliant on distance learning. It has become a vast experiment in life without in-person schooling.

Read More: What It’s Like Being a Teacher During the COVID-19 Pandemic

“[Education secretary Leonor Briones] always reminds us that in the past when there were military sieges, or volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, typhoons, floods, learning continued,” says education undersecretary Diosdado San Antonio.

But has it this time? Educators fear that prolonged closure is having negative effects on students’ ability to learn, impacting their futures just a time when the country needs a young, well-educated workforce to resume the impressive economic growth it was enjoying before the pandemic hit.

Globally, COVID-19 will be impacting the mental health of children and young adolescents for years to come, UNICEF warns. School shutdowns have already been blamed for a rise in dropout rates and decreased literacy, and the World Bank estimates that the number of children aged 10 and below, from low- and middle-income countries, who cannot read simple text has risen from 53% prior to the pandemic to 70% today.

If the pilot resumption of classes passes without incident, there are hopes for a wider reopening of Philippine schools. But without it, there are fears of a lost generation .

How COVID-19 impacted Philippine education

From March 2020 to September 2021, UNICEF tallied 131 million pre-tertiary students from 11 countries who had been trying to learn at home for at least three quarters of the time that they would normally have been in school. Of that number, 66 million came from just two countries where face-to-face classes were almost completely nixed: Bangladesh and the Philippines. (Bangladesh reopened its schools in September.)

Amid the initial COVID-19 surge of March 2020—just weeks shy of the end of the academic year—the Philippines stopped in-person classes for its entire cohort of public education students, which then numbered some 24.9 million according to UNESCO. The start of the new school year in September also got pushed back, as President Rodrigo Duterte imposed a “no vaccine, no classes” policy.

When schooling finally resumed in October 2020, the education department’s solution was a blend of remote-learning options: online platforms, educational TV and radio, and printed modules. But social inequalities and the lack of resources at home to support these approaches have dealt a huge blow to many students and teachers.

A departmental report released in March 2021 found that 99% of public school students got passing marks for the first academic quarter of last year. But other surveys claim that students are being disadvantaged. Over 86% of the 1,299 students polled by the Movement for Safe, Equitable, Quality and Relevant Education said they learned less through the education department’s take-home modules—so did 66% of those using online learning and 74% using a blend of online learning and hard-copy material.

Read More: Angelina Jolie on Why We Can Let COVID-19 Derail Education

Even though she’s an academic topnotcher—getting a weighted grade average of 91 out of 100 last year—Delaroso also feels that remote learning is inferior.

At Delaroso’s high school, teacher Johnnalie Consumo, 25, has detected a lack of eagerness to study, with some parents even filling in worksheets on their child’s behalf—going by the evidence of the handwriting.

“They have a hard time forcing the kid to answer modules because the kid isn’t intimidated by their parents,” she tells TIME. “The way a teacher encourages is very different from how a parent would.”

Consumo sometimes visits the homes of under-performing students and finds that they are out doing farm work—harvesting sugar cane, say, or making charcoal—to augment a family income that has been slashed by a suffering economy and a rising unemployment rate . Exercise books have been turned in blank, she says. Or students appear to pass their modules, only for her to find that they copied the answers. The frustration is enormous.

“It’s hard on our part,” Consumo tells TIME, “because we really try our best.”

Poverty and education in the Philippines

Internet access is a huge challenge. In urban areas, instructors can give lessons over video conferencing platforms, or Facebook Live, but 52.6% of the Philippines’ 110 million people live in rural areas with unreliable connectivity. It doesn’t come cheap either: research from cybersecurity firm SurfShark found that the internet in the Philippines is among the least stable and slowest, yet the most expensive, of 79 countries surveyed.

Internet access assumes, of course, that the user has a device, but in the Philippines that’s not a given. Private polling firm Social Weather Stations found that just over 40% of students did not have any device to help them in distance learning. Of the rest, some 27% were using a device they already owned, and 10% were able to borrow one, but 12% had to buy one, with families spending an average of $172 per learner. To put it into perspective, that’s more than half the average monthly salary in the Philippines.

“Some of them don’t have cell phones,” says Marilyn Tomelden, a teacher in Quezon province, three hours away from the Philippine capital Manila, who first noticed the digital divide when many of her sixth graders were unable to comply with what she thought of as a fun homework assignment: submitting videos of themselves performing dance moves she had demonstrated in an earlier video.

“Because we’re in public school, we cannot demand that they buy phones,” Tomelden says. “They don’t have money to buy their own food, and they’re going to buy their own cell phone for learning? Which is more important to live—to eat or to study?”

Instructors need to be equipped with the right resources too. A study from the National Research Council of the Philippines found that many teachers have had to shell out their own money to support their students in remote learning.

Read More: The Long History of Vaccinating Kids in School

Government agencies do what they can to help. Earlier this year, the customs bureau donated phones and other gadgets it had confiscated to the education department for distribution to needy students. But it’s a drop in the ocean.

“It’s something that is beyond [our] capacity to address—the inequality in terms of availability of resources of learners, depending on the socioeconomic status of families,” says education undersecretary San Antonio.

Some students are so exhausted by the struggle to study remotely that they are calling for long breaks between modules. Many parents and pressure groups are going even further, demanding total academic suspension until a clearer post-pandemic education system is ironed out.

Congresswoman France Castro is a member of ACT Teachers Partylist, a political party representing the education sector. She says a complete freeze would cause more problems than it solves.

“Education is a right,” she tells TIME. “Whatever form it will be, whether blended learning or modular, it’s better to continue it than to stop.”

But in the meantime, with their workloads multiplied, it is students and teachers paying the price. Consumo, the teacher from Januiay, regularly stays up late completing the reams of new paperwork generated by the distance learning system.

“You won’t be able to sleep anymore, just thinking about the deadlines and the work that still needs to be done,” she says. “I cry over that.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Passengers Are Flying up to 30 Hours to See Four Minutes of the Eclipse

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Essay: The Complicated Dread of Early Spring

- Why Walking Isn’t Enough When It Comes to Exercise

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

You May Also Like

- Geopolitics

- Environment

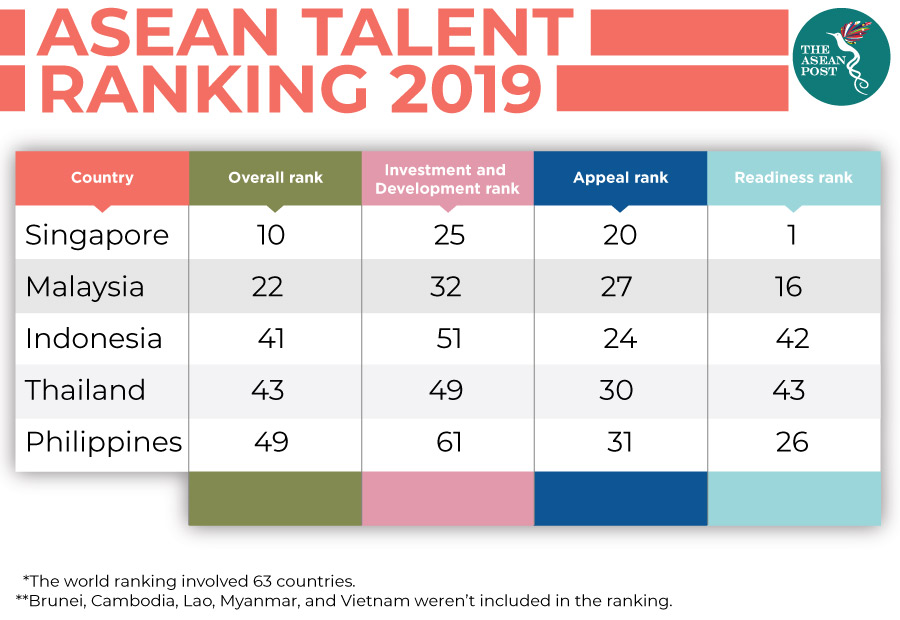

Philippines needs to improve its education system

The research arm of Switzerland-based business school, the International Institute for Management Development (IMD) recently released the results of its survey on the talent competitiveness of 63 countries from around the world. Based on the rankings, the Philippines managed to jump up to 49th place from 55th last year.

Regardless of the jump, the ASEAN country, unfortunately, still performed the worst when compared to other bloc members. In order to understand how this happened, it’s important to look at what the study uses for its indicators.

The World Talent Ranking looks at three main factors when determining how to rank a country. The investment and development factor, which measures resources used to cultivate homegrown human capital; the appeal factor, which evaluates the extent to which a country attracts and retains foreign and local talent; and the readiness factor, which looks at the quality of skills and competencies of a country’s labour force.

While a simple example of the investment and development factor would be whether a country is able to provide education to its citizens, the readiness factor seems to indicate that it is also important to look at the quality of the education provided. This, according to the study, is where countries like the Philippines fall short.

Quality of education

For the three factors, the Philippines scored 31st for appeal, 61st for investment and development, and 26th for readiness. Similarly, last year, the Philippines scored lowest for investment and development.

In 2018, the IMD World Competitiveness Center’s director, Arturo Bris told the media that the Philippines’ labour force is not as equipped with skills that firms are looking for.

He acknowledged that it was true that the Philippines was making progress in managing its talent pool and is, in fact, one of only two countries in Southeast Asia along with Malaysia which has improved government investment in education as a percent of gross domestic product (GDP).

“However, in 2018, The Philippines witnessed a deterioration of its ability to provide the economy with the skills needed, which points to a mismatch between school curriculums and the demands of companies,” he said.

But it isn’t just a Swiss business school that thinks the Philippines needs to improve its quality of education. In June last year, local media reported the Philippine Business for Education (PBEd) as saying that while the state of education nationwide has progressed in terms of accessibility, it still has a long way to go when it comes to delivery of quality learning for the success of every learner.

PBEd executive director, Love Basillote said this can be attributed to many factors such as prevalence of malnutrition and a shortage of appropriate learning tools, adding that many college graduates are not work-ready due to a lack of socio-emotional skills.

“Our recommendation is we focus on learning by starting early, monitoring learning, raising accountability and aligning actors,” she said, also suggesting that the country participate consistently in international learning assessments to make Filipino learners and graduates globally competitive.

The World Talent Ranking 2018 cited the country’s top weaknesses in the areas of total public expenditure on education, pupil-teacher ratio in primary and secondary schools, and remuneration in service professions and labour force growth.

Upgrading digital skills

The World Economic Forum (WEF) head of Asia Pacific and Member of the Executive Committee, Justin Wood noted that Industry 4.0, also known as the Fourth Industrial Revolution, was unfolding at accelerating speed and changing the skills that workers will need for the jobs of the future.

On 19 November last year, a coalition of major technology companies pledged to develop digital skills for the ASEAN workforce. Being part of the WEF’s Digital ASEAN initiative, the pledge aims to train some 20 million people in Southeast Asia by 2020, especially those working in small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs).

The move is most welcomed especially due to the threat of huge job displacement across the region. Now, following results from the World Talent Ranking, it seems that this initiative would be much needed in the Philippines as well.

However, the Philippines must understand that the pledge will only go so far in ensuring that it has the right workforce for the new skills demands of companies. Improving the quality of education in the country is still critical and as 2019’s results highlight, the Philippines needs to continue working on this.

This article was first published on 5 December, 2019.

Related articles:

Critical thinking needed to upgrade skills

Time to invest in human capital

Tangshan And Xuzhou: China's Treatment Of Women

Myanmar's suu kyi: prisoner of generals, philippines ends china talks for scs exploration, ukraine war an ‘alarm for humanity’: china’s xi, china to tout its governance model at brics summit, wrist-worn trackers detect covid before symptoms.

By providing an email address. I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge that I have read the Privacy Policy .

Issues in PH education: A teacher’s perspective

The Philippine education system is riddled with challenges and issues, from the K-12 curriculum and teachers’ training, to the continuing battle for higher salaries for teachers, and the shortage of classrooms and learning materials for students. These issues have been reported in news media platforms and have been the subject of everyday conversation, proof that education is still top of mind in Philippine society.

These issues were also highlighted in the Second Congressional Commission on Education (EdCom II), which has begun consultations with stakeholders in the education sector, including teachers like me. The consultation, which was participated in by teachers from Metro Manila, revolved around our experiences, learning impediments, and challenges both in school governance, and with regards to the Department of Education. The consultation also welcomed discussions on success stories essential for the continued progress of programs for learners and teachers.

For all the discussions on educational reforms, curriculum revisions, and career progression, one question remained unanswered: Where does a public school teacher like me stand? What are the issues that are priorities for us teachers in government? Throughout a decade of teaching experience in public schools, I share the sentiments of my fellow teachers who identified crucial issues that may be a game changer if EdCom II successfully addresses them.

Topping the list is the salary increase for teachers. Not only would it boost morale, it would also help the rebranding of teaching as a profession, thus enticing competitive young minds to take up education as a career. Another issue highlighted is the weak preservice and in-service training of teachers, both of which are often not aligned with the demands and skills of the education sector. This includes mismatched teacher specialization and subjects taught in class, resulting in a lack of mastery among learners and failure to achieve target competencies in a given quarter.

The curriculum is congested, and several prerequisites of some learning competencies are missing and misplaced. The outcome is poor results in the academic performance of learners in international assessments, such as the Programme for International Student Assessment and the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study. The failure to hit the target skills of learners is magnified by another culprit: the ineffective pedagogical skill of our teachers.

The K-12 curriculum demands a learner-centered approach which is barely seen in seasoned and experienced teachers in public schools. This is a skill that may be premised on underlying problems such as unfulfilled principles of inclusion, diversity, and individual differences among students. As Heraldo Richards, Ayanna Brown, and Timothy Forde (2007) put it, there are three levels essential to establish inclusivity: institutional, personal, and instructional.

Institutional commitment refers to the organization dimensions such as space, building and infrastructure, facilities, and conducive classrooms which remain a huge problem as the number of enrollees increase every year. The personal dimension refers to a teacher’s ability to reflect on diversity issues, challenging their own attitudes, beliefs, perception, and willingness to know their students as learners and individuals, a difficult task considering the teacher-learner ratio both in elementary and secondary public schools.

The third level, the instructional dimension refers to the pedagogy, instructional materials, and strategies to be used that align with the needs of diverse students. Neglecting these elements and diversity-related issues may lead to inequality and subsequently hinder the teaching and learning process within our classrooms.

EdCom II plays a crucial role in augmenting some pressing issues in the realm of teacher education and training. In a healthy ecosystem, we need birds and frogs. Birds that soar above see the overall picture, while frogs on the ground see the granular details on the frontline. We need both EdCom II and the voice of the teachers, which represent the knowledge and view of birds and frogs, respectively, to be able to craft sustainable solutions to ever-recurring issues and challenges in our basic education system.

—————-

David Yu is a Grade 12 teacher who participated in EdCom II’s consultations on teacher education and training. His personal views in this article do not represent those of any organization or institution.

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

Fearless views on the news

Disclaimer: Comments do not represent the views of INQUIRER.net. We reserve the right to exclude comments which are inconsistent with our editorial standards. FULL DISCLAIMER

© copyright 1997-2024 inquirer.net | all rights reserved.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. By continuing, you are agreeing to our use of cookies. To find out more, please click this link.

share this!

April 2, 2024

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies . Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

reputable news agency

Hundreds of Philippine schools suspend classes over heat danger

by Cecil MORELLA

Hundreds of schools in the Philippines, including dozens in the capital Manila, suspended in-person classes on Tuesday due to dangerous levels of heat, education officials said.

The country's heat index measures what a temperature feels like, taking into account humidity.

The index was expected to reach the "danger" level of 42 degrees Celsius in Manila on Tuesday and 43C on Wednesday, with similar levels in a dozen other areas of the country, the state weather forecaster said.

The actual highest recorded temperature for the metropolis on Tuesday was 35.7C, below the record of 38.6C reached on May 17, 1915.

Local officials across the main island of Luzon, the central islands, and the southern island of Mindanao suspended in-person classes or shortened school hours to avoid the hottest part of the day, education ministry officials said.

The Department of Education was unable to provide an exact number of schools affected.

March, April and May are typically the driest months of the year for swathes of the tropical country. This year conditions have been exacerbated by the El Niño weather phenomenon.

Primary and secondary schools in Quezon, the most populous part of the capital, were ordered to shut while schools in other areas were given the option by local officials to shift to remote learning.

Some schools in Manila also reduced class hours.

A heat index of 42-51C can cause heat cramps and exhaustion, with heat stroke "probable with continued exposure", the weather forecaster said in an advisory.

Heat cramps and heat exhaustion are also possible at 33-41C, according to the forecaster.

The orders affected hundreds of schools in the Mindanao provinces of Cotabato, South Cotabato and Sultan Kudarat, as well as the cities of Cotabato, General Santos and Koronadal, Zamboanga regional education ministry spokeswoman Rea Halique told AFP.

Five schools in Mindanao's Zamboanga region also shut schools for the day, though local officials in the area did not recommend the suspension of in-person classes in other schools, the ministry said.

"At the Pagadian City Pilot School one (kindergarten) student and two in the elementary school suffered nosebleeds," Zamboanga regional education ministry official Dahlia Paragas told AFP.

"All of them are back at home in stable condition and were advised to avoid exposure to the sunlight."

Cotabato city experienced the highest heat index in Mindanao, reaching 42C on Monday and Tuesday, the state forecaster reported.

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Researchers envision sci-fi worlds involving changes to atmospheric water cycle

4 hours ago

New fossil dolphin identified

5 hours ago

Pacific rock samples offer glimpse of active Earth 2.5 billion years ago

What four decades of canned salmon reveal about marine food webs

6 hours ago

Study reports that people and environment both benefit from diversified farming, while bottom lines also thrive

New research traces the fates of stars living near the Milky Way's central black hole

How NASA's Roman Telescope will measure the ages of stars

Rusty-patched bumblebee's struggle for survival found in its genes

Click chemistry: Research team creates 150 new compounds

7 hours ago

The life aquatic: Why diurnal frog species kept genes adapted to night vision

Relevant physicsforums posts, unlocking the secrets of prof. verschure's rosetta stones, major earthquakes - 7.4 (7.2) mag and 6.4 mag near hualien, taiwan.

8 hours ago

Iceland warming up again - quakes swarming

Mar 30, 2024

‘Our clouds take their orders from the stars,’ Henrik Svensmark on cosmic rays controlling cloud cover and thus climate

Mar 27, 2024

Higher Chance to get Lightning Strike by Large Power Consumption?

Mar 20, 2024

A very puzzling rock or a pallasite / mesmosiderite or a nothing burger

Mar 16, 2024

More from Earth Sciences

Related Stories

Stay hydrated: It's going to be a long, hot July for much of the U.S.

Jul 13, 2020

Expert discusses heat exhaustion and heatstroke

Jul 18, 2023

Italy's Milan records hottest day in 260 years

Aug 25, 2023

Spanish city shatters heat record

Aug 10, 2023

France sizzles in late summer 'heat dome'

Aug 21, 2023

Factors in the severity of heat stroke in China

Aug 16, 2022

Recommended for you

Electric vehicles may be lowering Bay Area's carbon footprint: Monitors record small decrease in CO₂ emissions

Researchers find the link between human activity and shifting weather patterns in western North America

9 hours ago

Unlocking Arctic mysteries: How melting ice shapes our climate

Ancient ocean oxygenation timeline revealed

10 hours ago

With the planet facing a 'polycrisis,' biodiversity researchers uncover major knowledge gaps

11 hours ago

Let us know if there is a problem with our content

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Addressing stakeholders with President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. in attendance, Duterte highlighted the key issues that plague the country's basic education system before announcing her department ...

For a brief rundown, let's list the top education issues in the Philippines: Quality - The results of the 2014 National Achievement Test (NAT) and the National Career Assessment Examination (NCAE) show that there had been a drop in the status of primary and secondary education. Budget - The country remains to have one of the lowest budget ...

In the Philippines, the Department of Education (DepEd) expected a drop of 20 percent of enrollment last school year. Online schooling was a great challenge to teachers who were not familiar with ...

In-person learning also enables teachers to identify and address learning delays, mental health issues, and abuse that could negatively affect children's well-being. "In 2020, schools globally were fully closed for an average of 79 teaching days, while the Philippines has been closed for more than a year, forcing students to enroll in ...

On Wednesday, March 13, Rappler's Bonz Magsambol sits down with Second Congressional Commission on Education or EDCOM II executive director Karol Yee to talk about the issues confronting the ...

Abstract. The Philippines has embarked on significant education reforms for the past three decades to raise the quality of education at all levels and address inclusion and equity issues. The country's AmBisyon Natin 2040 or the national vision for a prosperous and healthy society by 2040 is premised on education's role in developing human ...

Along with government officials, international aid agencies, education and humanitarian experts, policymakers, teachers and learners, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the Department of Education (DepEd) launched the 2020 Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report on 25 November 2020 virtually. With ...

Aaron Favila/Associated Press. MANILA — As jubilant students across the globe trade in online learning for classrooms, millions of children in the Philippines are staying home for the second ...

This factsheet provides an overview of education in the Philippines, highlighting enduring challenges. Despite progress with the K to 12 Program, issues persist in areas such as limited early childhood education participation, concerns about the quality and access to basic education, and the impact of natural disasters.

Amid the initial COVID-19 surge of March 2020—just weeks shy of the end of the academic year—the Philippines stopped in-person classes for its entire cohort of public education students, which ...

MANILA, 25 November 2020 - United Nations (UN) Resident Coordinator Gustavo Gonzalez cited the major progress achieved by the Philippine Government towards inclusive education in recent decades, but warned that the COVID-19 pandemic threatens reversing these hard-won gains. Gonzalez issued this statement at the launch today of the 2020 Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report.

Abstract. The Philippines is concerned about the number of students attending schools, the quality of education. they receive, and the state of the learning environment. Solvi ng the education ...

In order to grapple with some of these protracted issues, fragmented waves of education reform initiatives have been enacted. The most far-reaching effort thus far has been the Basic Education Sector Reform Agenda (BESRA). ... Philippines' education crisis far from over - UNESCO, The Philippine Star, pp. 1-2. Philippine Star Printing Co ...

For a brief rundown, let's list the top education issues in the Philippines: Quality - The results of the 2014 National Achievement Test (NAT) and the National Career Assessment Examination (NCAE) show that there had been a drop in the status of primary and secondary education. Budget - The country remains to have one of the lowest budget ...

Improving the quality of education in the country is still critical and as 2019's results highlight, the Philippines needs to continue working on this. This article was first published on 5 December, 2019. Critical thinking needed to upgrade skills. Time to invest in human capital. The Philippines scored poorly for education among ASEAN ...

A study by Philippine Business for Education (PBEd) revealed that since 2010, 56 percent of teacher education schools scored below average passing rates in the board licensure examination for professional teachers. And once they are in service, challenges continue to burden them, including administrative work that takes time away from teaching.

Key Issues in Education and Social Justice. London: SAGE. D. SAN ANTONIO ET AL. 11. ... (LEAP) which is a joint effort between the Philippines' Department of Education, the Ateneo de Manila ...

In the Philippines, some 2.3 million students were forced to drop out for varying reasons, among them, problems of connectivity, health, apathy, tardiness, absenteeism, and computer illiteracy. Parents have complained about having to spend 40 percent more to support online learning. Bridging these serious gaps, among them, lack of enough ...

Philippine Daily Inquirer / 05:02 AM September 15, 2023. The Philippine education system is riddled with challenges and issues, from the K-12 curriculum and teachers' training, to the continuing battle for higher salaries for teachers, and the shortage of classrooms and learning materials for students. These issues have been reported in news ...

In July 2022, RA 11899 created Edcom II to find ways of harnessing the educational sector "with the end in view of making the Philippines globally competitive in both education and labor markets ...

The Philippine Business for Education (PBEd) said the country's education system is in a "crisis." In its 2023 State of Philippine Education Report, PBEd said the declining mental health among students and teachers; lack of support for teachers; culture of "mass promotion" of learners, and the lack of proper assessments are among the most pressing issues that must be addressed.

Our childhood educational center is open for franchising. Mar 21, 2024 7:00 PM PHT. Philippine News.

Data from the World Bank shows that the Philippines' learning-adjusted years of school (LAYS) proficiency would be pushed back from 7.5 years pre-pandemic to 5.9 to 6.5 years, depending on the ...

Hundreds of schools in the Philippines, including dozens in the capital Manila, suspended in-person classes on Tuesday due to dangerous levels of heat, education officials said. The country's heat ...