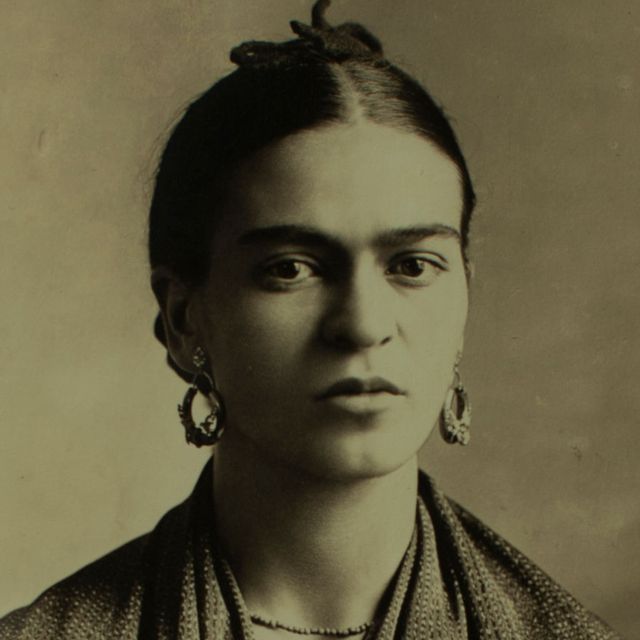

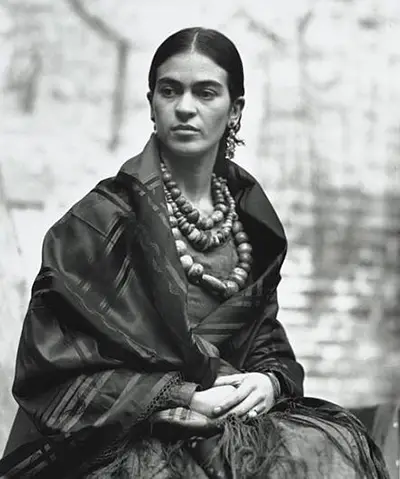

Frida Kahlo

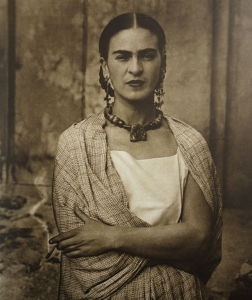

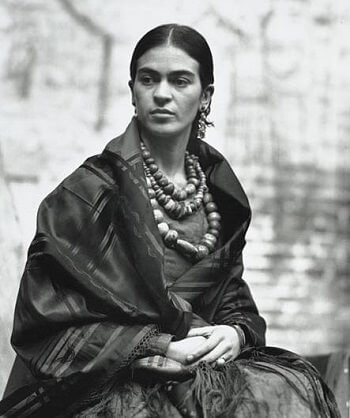

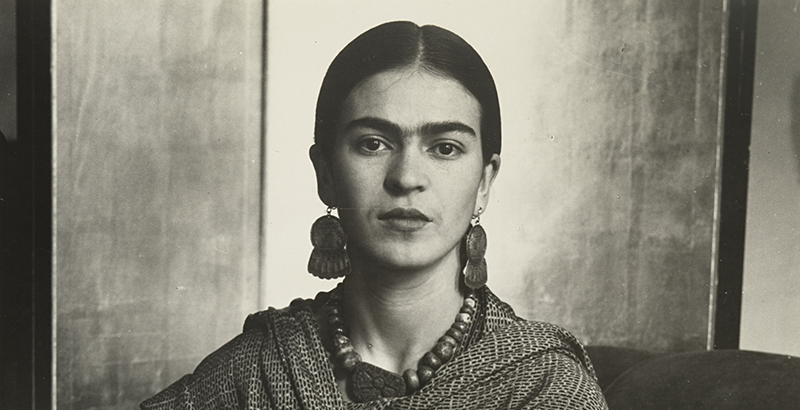

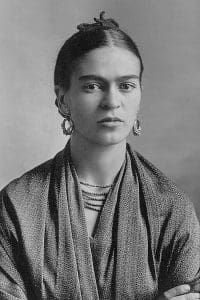

Painter Frida Kahlo was a Mexican artist who was married to Diego Rivera and is still admired as a feminist icon.

(1907-1954)

Who Was Frida Kahlo?

Artist Frida Kahlo was considered one of Mexico's greatest artists who began painting mostly self-portraits after she was severely injured in a bus accident. Kahlo later became politically active and married fellow communist artist Diego Rivera in 1929. She exhibited her paintings in Paris and Mexico before her death in 1954.

Family, Education and Early Life

Kahlo was born Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderón on July 6, 1907, in Coyoacán, Mexico City, Mexico.

Kahlo's father, Wilhelm (also called Guillermo), was a German photographer who had immigrated to Mexico where he met and married her mother Matilde. She had two older sisters, Matilde and Adriana, and her younger sister, Cristina, was born the year after Kahlo.

Around the age of six, Kahlo contracted polio, which caused her to be bedridden for nine months. While she recovered from the illness, she limped when she walked because the disease had damaged her right leg and foot. Her father encouraged her to play soccer, go swimming, and even wrestle — highly unusual moves for a girl at the time — to help aid in her recovery.

In 1922, Kahlo enrolled at the renowned National Preparatory School. She was one of the few female students to attend the school, and she became known for her jovial spirit and her love of colorful, traditional clothes and jewelry.

While at school, Kahlo hung out with a group of politically and intellectually like-minded students. Becoming more politically active, Kahlo joined the Young Communist League and the Mexican Communist Party.

Frida Kahlo's Accident

After staying at the Red Cross Hospital in Mexico City for several weeks, Kahlo returned home to recuperate further. She began painting during her recovery and finished her first self-portrait the following year, which she gave to Gómez Arias.

Frida Kahlo's Marriage to Diego Rivera

In 1929, Kahlo and famed Mexican muralist Diego Rivera married. Kahlo and Rivera first met in 1922 when he went to work on a project at her high school. Kahlo often watched as Rivera created a mural called The Creation in the school’s lecture hall. According to some reports, she told a friend that she would someday have Rivera’s baby.

Kahlo reconnected with Rivera in 1928. He encouraged her artwork, and the two began a relationship. During their early years together, Kahlo often followed Rivera based on where the commissions that Rivera received were. In 1930, they lived in San Francisco, California. They then went to New York City for Rivera’s show at the Museum of Modern Art and later moved to Detroit for Rivera’s commission with the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Kahlo and Rivera’s time in New York City in 1933 was surrounded by controversy. Commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller , Rivera created a mural entitled Man at the Crossroads in the RCA Building at Rockefeller Center. Rockefeller halted the work on the project after Rivera included a portrait of communist leader Vladimir Lenin in the mural, which was later painted over. Months after this incident, the couple returned to Mexico and went to live in San Angel, Mexico.

Never a traditional union, Kahlo and Rivera kept separate, but adjoining homes and studios in San Angel. She was saddened by his many infidelities, including an affair with her sister Cristina. In response to this familial betrayal, Kahlo cut off most of her trademark long dark hair. Desperately wanting to have a child, she again experienced heartbreak when she miscarried in 1934.

Kahlo and Rivera went through periods of separation, but they joined together to help exiled Soviet communist Leon Trotsky and his wife Natalia in 1937. The Trotskys came to stay with them at the Blue House (Kahlo's childhood home) for a time in 1937 as Trotsky had received asylum in Mexico. Once a rival of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin , Trotsky feared that he would be assassinated by his old nemesis. Kahlo and Trotsky reportedly had a brief affair during this time.

Kahlo divorced Rivera in 1939. They did not stay divorced for long, remarrying in 1940. The couple continued to lead largely separate lives, both becoming involved with other people over the years .

Artistic Career

While she never considered herself a surrealist, Kahlo befriended one of the primary figures in that artistic and literary movement, Andre Breton, in 1938. That same year, she had a major exhibition at a New York City gallery, selling about half of the 25 paintings shown there. Kahlo also received two commissions, including one from famed magazine editor Clare Boothe Luce, as a result of the show.

In 1939, Kahlo went to live in Paris for a time. There she exhibited some of her paintings and developed friendships with such artists as Marcel Duchamp and Pablo Picasso .

Kahlo received a commission from the Mexican government for five portraits of important Mexican women in 1941, but she was unable to finish the project. She lost her beloved father that year and continued to suffer from chronic health problems. Despite her personal challenges, her work continued to grow in popularity and was included in numerous group shows around this time.

In 1953, Kahlo received her first solo exhibition in Mexico. While bedridden at the time, Kahlo did not miss out on the exhibition’s opening. Arriving by ambulance, Kahlo spent the evening talking and celebrating with the event’s attendees from the comfort of a four-poster bed set up in the gallery just for her.

After Kahlo’s death, the feminist movement of the 1970s led to renewed interest in her life and work, as Kahlo was viewed by many as an icon of female creativity.

Frida Kahlo's Most Famous Paintings

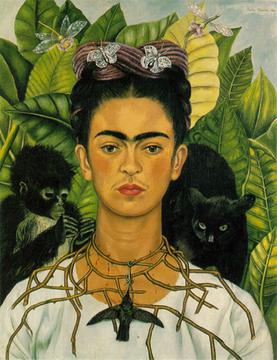

Many of Kahlo’s works were self-portraits. A few of her most notable paintings include:

'Frieda and Diego Rivera' (1931)

Kahlo showed this painting at the Sixth Annual Exhibition of the San Francisco Society of Women Artists, the city where she was living with Rivera at the time. In the work, painted two years after the couple married, Kahlo lightly holds Rivera’s hand as he grasps a palette and paintbrushes with the other — a stiffly formal pose hinting at the couple’s future tumultuous relationship. The work now lives at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

'Henry Ford Hospital' (1932)

In 1932, Kahlo incorporated graphic and surrealistic elements in her work. In this painting, a naked Kahlo appears on a hospital bed with several items — a fetus, a snail, a flower, a pelvis and others — floating around her and connected to her by red, veinlike strings. As with her earlier self-portraits, the work was deeply personal, telling the story of her second miscarriage.

'The Suicide of Dorothy Hale' (1939)

Kahlo was asked to paint a portrait of Luce and Kahlo's mutual friend, actress Dorothy Hale, who had committed suicide earlier that year by jumping from a high-rise building. The painting was intended as a gift for Hale's grieving mother. Rather than a traditional portrait, however, Kahlo painted the story of Hale's tragic leap. While the work has been heralded by critics, its patron was horrified at the finished painting.

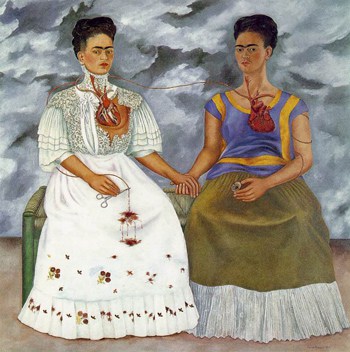

'The Two Fridas' (1939)

One of Kahlo’s most famous works, the painting shows two versions of the artist sitting side by side, with both of their hearts exposed. One Frida is dressed nearly all in white and has a damaged heart and spots of blood on her clothing. The other wears bold colored clothing and has an intact heart. These figures are believed to represent “unloved” and “loved” versions of Kahlo.

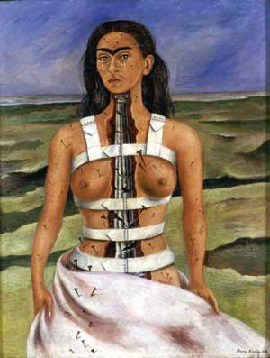

'The Broken Column' (1944)

Kahlo shared her physical challenges through her art again with this painting, which depicted a nearly nude Kahlo split down the middle, revealing her spine as a shattered decorative column. She also wears a surgical brace and her skin is studded with tacks or nails. Around this time, Kahlo had several surgeries and wore special corsets to try to fix her back. She would continue to seek a variety of treatments for her chronic physical pain with little success.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S FRIDA KAHLO FACT CARD

Frida Kahlo’s Death

About a week after her 47th birthday, Kahlo died on July 13, 1954, at her beloved Blue House. There has been some speculation regarding the nature of her death. It was reported to be caused by a pulmonary embolism, but there have also been stories about a possible suicide.

Kahlo’s health issues became nearly all-consuming in 1950. After being diagnosed with gangrene in her right foot, Kahlo spent nine months in the hospital and had several operations during this time. She continued to paint and support political causes despite having limited mobility. In 1953, part of Kahlo’s right leg was amputated to stop the spread of gangrene.

Deeply depressed, Kahlo was hospitalized again in April 1954 because of poor health, or, as some reports indicated, a suicide attempt. She returned to the hospital two months later with bronchial pneumonia. No matter her physical condition, Kahlo did not let that stand in the way of her political activism. Her final public appearance was a demonstration against the U.S.-backed overthrow of President Jacobo Arbenz of Guatemala on July 2nd.

Movie on Frida Kahlo

Kahlo’s life was the subject of a 2002 film entitled Frida , starring Salma Hayek as the artist and Alfred Molina as Rivera. Directed by Julie Taymor, the film was nominated for six Academy Awards and won for Best Makeup and Original Score.

Frida Kahlo Museum

The family home where Kahlo was born and grew up, later referred to as the Blue House or Casa Azul, was opened as a museum in 1958. Located in Coyoacán, Mexico City, the Museo Frida Kahlo houses artifacts from the artist along with important works including Viva la Vida (1954), Frida and Caesarean (1931) and Portrait of my father Wilhelm Kahlo (1952).

Book on Frida Kahlo

Hayden Herrera’s 1983 book on Kahlo, Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo , helped to stir up interest in the artist. The biographical work covers Kahlo’s childhood, accident, artistic career, marriage to Diego Rivera, association with the communist party and love affairs.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Frida Kahlo

- Birth Year: 1907

- Birth date: July 6, 1907

- Birth City: Mexico City

- Birth Country: Mexico

- Gender: Female

- Best Known For: Painter Frida Kahlo was a Mexican artist who was married to Diego Rivera and is still admired as a feminist icon.

- Astrological Sign: Cancer

- National Preparatory School

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- Frida Kahlo met Diego Rivera when he was commissioned to paint a mural at her high school.

- Kahlo dealt with chronic pain most of her life due to a bus accident.

- Death Year: 1954

- Death date: July 13, 1954

- Death City: Mexico City

- Death Country: Mexico

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Frida Kahlo Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/artists/frida-kahlo

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: November 19, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- I never paint dreams or nightmares. I paint my own reality.

- My painting carries with it the message of pain.

- I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.

- I think that, little by little, I'll be able to solve my problems and survive.

- The only thing I know is that I paint because I need to, and I paint whatever passes through my head without any other consideration.

- I was born a bitch. I was born a painter.

- I love you more than my own skin.

- I am not sick, I am broken, but I am happy as long as I can paint.

- Feet, what do I need you for when I have wings to fly?

- I tried to drown my sorrows, but the bastards learned how to swim, and now I am overwhelmed with this decent and good feeling.

- There have been two great accidents in my life. One was the trolley and the other was Diego. Diego was by far the worst.

- I hope the end is joyful, and I hope never to return.

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Famous Painters

11 Notable Artists from the Harlem Renaissance

Fernando Botero

Gustav Klimt

The Surreal Romance of Salvador and Gala Dalí

Salvador Dalí

Margaret Keane

Andy Warhol

- Arts & Photography

- History & Criticism

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: $19.95 $19.95 FREE delivery: Tuesday, April 23 on orders over $35.00 shipped by Amazon. Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Buy used: $11.61

Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) is a service we offer sellers that lets them store their products in Amazon's fulfillment centers, and we directly pack, ship, and provide customer service for these products. Something we hope you'll especially enjoy: FBA items qualify for FREE Shipping and Amazon Prime.

If you're a seller, Fulfillment by Amazon can help you grow your business. Learn more about the program.

Other Sellers on Amazon

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo Paperback – October 1, 2002

Purchase options and add-ons.

"Through her art, Herrera writes, Kahlo made of herself both performer and icon. Through this long overdue biography, Kahlo has also, finally, been made fully human." — San Francisco Chronicle

Hailed by readers and critics across the country, this engrossing biography of Mexican painter Frida Kahlo reveals a woman of extreme magnetism and originality, an artist whose sensual vibrancy came straight from her own experiences: her childhood near Mexico City during the Mexican Revolution; a devastating accident at age eighteen that left her crippled and unable to bear children; her tempestuous marriage to muralist Diego Rivera and intermittent love affairs with men as diverse as Isamu Noguchi and Leon Trotsky; her association with the Communist Party; her absorption in Mexican folklore and culture; and her dramatic love of spectacle.

Here is the tumultuous life of an extraordinary twentieth-century woman -- with illustrations as rich and haunting as her legend.

- Print length 528 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Harper Perennial

- Publication date October 1, 2002

- Dimensions 6.12 x 1.4 x 9.25 inches

- ISBN-10 0060085894

- ISBN-13 978-0060085896

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Similar items that may ship from close to you

Editorial Reviews

"A haunting, highly vivid biography." — Ms . magazine

From the Back Cover

About the author.

Hayden Herrera is an art historian. She has lectured widely, curated several exhibitions of art, taught Latin American art at New York University, and has been awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship. She is the author of numerous articles and reviews for such publications as Art in America, Art Forum, Connoisseur, and the New York Times, among others. Her books include Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo; Mary Frank; and Matisse: A Portrait. She is working on a critical biography of Arshile Gorky. She lives in New York City.

Product details

- Publisher : Harper Perennial (October 1, 2002)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 528 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0060085894

- ISBN-13 : 978-0060085896

- Item Weight : 1.43 pounds

- Dimensions : 6.12 x 1.4 x 9.25 inches

- #55 in Artist & Architect Biographies

- #80 in Arts & Photography Criticism

- #154 in Art History (Books)

About the author

Hayden herrera.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Frida Kahlo, in her own words: A new documentary draws from diaries, letters

Mandalit del Barco

A new documentary about Frida Kahlo's life, now streaming on Amazon Prime, tells her story using her own words and art. Leo Matiz/Fundación Leo Matiz hide caption

A new documentary about Frida Kahlo's life, now streaming on Amazon Prime, tells her story using her own words and art.

"I paint myself because that's who I know the best," the late Mexican artist Frida Kahlo once wrote in her illustrated diary. So it's fitting that a new documentary about Kahlo's life, now streaming on Amazon Prime, tells her story using her own words and art.

In the 70 years since Kahlo's death there have been countless efforts to revisit her complicated life, politics and artwork. Most famous is probably the 2002 fictional film starring Salma Hayek and directed by Julie Taymor that depicted Kahlo's tempestuous relationship with painter Diego Rivera. Many of these treatments have relied on actors, interviews with academics, art historians and contemporary artists. Filmmaker Carla Gutiérrez wanted a fresh take.

"Instead of having that historical distance of other people explaining [to] us what she meant with her art," Gutiérrez says, "I really wanted to give that gift to viewers of just hearing from her own words. We wanted to have the most intimate entry way into her heart and into her mind."

In Frida, Kahlo's words are taken from letters and diaries, and voiced by Mexican actor Fernanda Echevarría del Rivero. The film is in Spanish, with English subtitles. Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, S.C. hide caption

In Frida, Kahlo's words are taken from letters and diaries, and voiced by Mexican actor Fernanda Echevarría del Rivero. The film is in Spanish, with English subtitles.

In Gutiérrez's documentary Frida, Kahlo's words are taken from handwritten letters and illustrated diaries, and voiced by Mexican actor Fernanda Echevarría del Rivero. The film is in Spanish, with English subtitles.

Gutiérrez says she wanted to get inside Kahlo's head. "What was she thinking? what was she feeling? I felt that as a Latina, somebody that grew up in Latin America, there was this connection I have with the world that created Frida."

Gutiérrez was born in Peru and saw her first Frida Kahlo painting, as a college student in Massachusetts. It was an image of Kahlo standing with one foot in Mexico, another in the U.S. "Her impressions of the United States and yearning [for] home for Mexico, that painting really reflected my own experience," says Gutiérrez. "And then I became obsessed, like millions of people around the world."

As an editor, Gutiérrez has worked on documentaries on other what she calls "badass women", including the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg , singer Chavela Vargas and chef Julia Child . But Frida is her first film as director.

The Picture Show

Frida kahlo's private stash of pictures.

She enlisted the help of Hayden Herrera, who wrote the definitive Frida Kahlo biography in 1983 . Gutiérrez' team combed through Herrera's closets and attic, looking through her archives.

"We had a good time," Herrera says. "I basically gave them all my research material."

That included transcripts of interviews with people who knew Kahlo. One of the film's archivists, Gabriel Rivera, also scoured university libraries, museums and private collections finding photos and handwritten messages.

"These letters often have little doodles on them," Rivera says. "She would, like, do kind of lipstick kisses on these letters."

The film includes the words written by or about Kahlo's contemporaries, including Diego Rivera, who she married twice, her friends such as surrealist André Breton and her lovers such as Russian revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky.

Some of Kahlo's paintings are slightly animated in the new film. Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, S.C. hide caption

Some of Kahlo's paintings are slightly animated in the new film.

Gabriel Rivera says they tried to follow any lead, including a tip about some footage of Kahlo dancing in the streets of New York City with a rose stem gripped in her mouth. He discovered through writings that the film canister had been left on an airplane in the late 1960s, which Rivera said is "just devastating." They tried to find lost luggage and are still hoping it shows up one day.

But there is plenty of material they did find.

In Mexico, another archivist, Adrián Gutiérrez, was able to collect some rarely seen photos and footage of Kahlo and Rivera together, and of Rivera kissing another woman. There's footage of the Mexican revolutionary Emilio Zapata and of Red Cross workers in Mexico City bandaging trolley accident victims like Kahlo, who was famously injured as a teen. She painted about that and other pain she suffered.

For the documentary, composer Víctor Hernández Stumpfhauser created a soundtrack of electronic music with folkloric guitar and the ethereal voice of his wife, Alexa Ramírez.

Hear Mandalit del Barco's 1991 radio documentary about Frida Kahlo

"The idea was that Frida herself was so ahead of her time, with her thoughts, her ideas. She was a very modern person," says Stumpfhauser. "So we thought, well, let's let's do something modern, but of course, with a with a Mexican flair."

Gutiérrez also made the decision to slightly animate some of Kahlo's paintings. Frida's open heart beats and bleeds, tears roll down her face, and when she cuts her hair in desperation over her divorce, her scissors move and pieces of her hair fall to the floor.

Latin America

As mexico capitalizes on her image, has frida kahlo become over-commercialized.

The Salma Hayek film also animated some of Kahlo's work. But Herrera says doing so in a documentary was gutsy.

"When I saw the first animation, I thought, Oh my God," says Herrera. "But then I found it really seductive and really added so much to the understanding of her paintings. I found them very astute and actually quite witty. And they brought you closer to Frida."

Art Where You're At

5 lesser-known, late-in-life works by frida kahlo now on view in dallas.

Herrera says its remarkable that Frida mania is still very much alive.

"I think she would have been pleased that we're still talking about her, and I think she would have liked this film," she says. "Although seeing your own paintings animated might not be easy, but she might have given one of her big guffaws and laughed and thought it was amusing."

Herrera says this latest documentary is her favorite telling of Frida Kahlo, and is itself a work of art.

Detroit's 'Frida' Aims To Build Latino Audiences For Opera

Music Interviews

The villalobos brothers match music with frida kahlo.

- frida kahlo

ARTS & CULTURE

Frida kahlo.

The Mexican artist’s myriad faces, stranger-than-fiction biography and powerful paintings come to vivid life in a new film

Phyllis Tuchman

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9c/04/9c0461e2-407f-48e6-8293-bab6c7c5f353/frida_kahlo_by_guillermo_kahlo.jpg)

Frida Kahlo, who painted mostly small, intensely personal works for herself, family and friends, would likely have been amazed and amused to see what a vast audience her paintings now reach. Today, nearly 50 years after her death, the Mexican artist’s iconic images adorn calendars, greeting cards, posters, pins, even paper dolls. Several years ago the French couturier Jean Paul Gaultier created a collection inspired by Kahlo, and last year a self-portrait she painted in 1933 appeared on a 34-cent U.S. postage stamp. This month, the movie Frida, starring Salma Hayek as the artist and Alfred Molina as her husband, renowned muralist Diego Rivera, opens nationwide. Directed by Julie Taymor, the creative wizard behind Broadway’s long-running hit The Lion King , the film is based on Hayden Herrera’s 1983 biography, Frida. Artfully composed, Taymor’s graphic portrayal remains, for the most part, faithful to the facts of the painter’s life. Although some changes were made because of budget constraints, the movie “is true in spirit,” says Herrera, who was first drawn to Kahlo because of “that thing in her work that commands you—that urgency, that need to communicate.”

Focusing on Kahlo’s creativity and tumultuous love affair with Rivera, the film looks beyond the icon to the human being. “I was completely compelled by her story,” says Taymor. “I knew it superficially; and I admired her paintings but didn’t know them well. When she painted, it was for herself. She transcended her pain. Her paintings are her diary. When you’re doing a movie, you want a story like that.” In the film, the Mexican born and raised Hayek, 36, who was one of the film’s producers, strikes poses from the paintings, which then metamorphose into action-filled scenes. “Once I had the concept of having the paintings come alive,” says Taymor, “I wanted to do it.”

Kahlo, who died July 13, 1954, at the age of 47, reportedly of a pulmonary embolism (though some suspected suicide), has long been recognized as an important artist. In 2001-2002, a major traveling exhibition showcased her work alongside that of Georgia O’Keeffe and Canada’s Emily Carr. Earlier this year several of her paintings were included in a landmark Surrealism show in London and New York. Currently, works by both Kahlo and Rivera are on view through January 5, 2003, at the SeattleArt Museum. As Janet Landay, curator of exhibitions at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and one of the organizers of a 1993 exhibition of Kahlo’s work, points out, “Kahlo made personal women’s experiences serious subjects for art, but because of their intense emotional content, her paintings transcend gender boundaries. Intimate and powerful, they demand that viewers—men and women—be moved by them.”

Kahlo produced only about 200 paintings—primarily still lifes and portraits of herself, family and friends. She also kept an illustrated journal and did dozens of drawings. With techniques learned from both her husband and her father, a professional architectural photographer, she created haunting, sensual and stunningly original paintings that fused elements of surrealism, fantasy and folklore into powerful narratives. In contrast to the 20th-century trend toward abstract art, her work was uncompromisingly figurative. Although she received occasional commissions for portraits, she sold relatively few paintings during her lifetime. Today her works fetch astronomical prices at auction. In 2000, a 1929 self-portrait sold for more than $5 million.

Biographies of the artist, which have been translated into many languages, read like the fantastical novels of Gabriel García Márquez as they trace the story of two painters who could not live with or without each other. (Taymor says she views her film version of Kahlo’s life as a “great, great love story.”) Married twice, divorced once and separated countless times, Kahlo and Rivera had numerous affairs, hobnobbed with Communists, capitalists and literati and managed to create some of the most compelling visual images of the 20th century. Filled with such luminaries as writer André Breton, sculptor Isamu Noguchi, playwright Clare Boothe Luce and exiled Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky, Kahlo’s life played out on a phantasmagorical canvas.

She was born Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón July 6, 1907, and lived in a house (the Casa Azul, or Blue House, now the Museo Frida Kahlo) built by her father in Coyoacán, then a quiet suburb of Mexico City. The third of her parents’ four daughters, Frida was her father’s favorite—the most intelligent, he thought, and the most like himself. She was a dutiful child but had a fiery temperament. (Shortly before Kahlo and Rivera were wed in 1929, Kahlo’s father warned his future son-in-law, who at age 42 had already had two wives and many mistresses, that Frida, then 21, was “a devil.” Rivera replied: “I know it.”)

A German Jew with deep-set eyes and a bushy mustache, Guillermo Kahlo had immigrated to Mexico in 1891 at the age of 19. After his first wife died in childbirth, he married Matilde Calderón, a Catholic whose ancestry included Indians as well as a Spanish general. Frida portrayed her hybrid ethnicity in a 1936 painting, My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (opposite).

Kahlo adored her father. On a portrait she painted of him in 1951, she inscribed the words, “character generous, intelligent and fine.” Her feelings about her mother were more conflicted. On the one hand, the artist considered her “very nice, active, intelligent.” But she also saw her as fanatically religious, calculating and sometimes even cruel. “She did not know how to read or write,” recalled the artist. “She only knew how to count money.”

A chubby child with a winning smile and sparkling eyes, Kahlo was stricken with polio at the age of 6. After her recovery, her right leg remained thinner than her left and her right foot was stunted. Despite her disabilities or, perhaps, to compensate for them, Kahlo became a tomboy. She played soccer, boxed, wrestled and swam competitively. “My toys were those of a boy: skates, bicycles,” the artist later recalled. (As an adult, she collected dolls.)

Her father taught her photography, including how to retouch and color prints, and one of his friends gave her drawing lessons. In 1922, the 15-year-old Kahlo entered the elite, predominantly male NationalPreparatory School, which was located near the Cathedral in the heart of Mexico City.

As it happened, Rivera was working in the school’s auditorium on his first mural. In his autobiography— My Art, My Life —the artist recalled that he was painting one night high on a scaffold when “all of a sudden the door flew open, and a girl who seemed to be no more than ten or twelve was propelled inside. . . . She had,” he continued, “unusual dignity and self-assurance, and there was a strange fire in her eyes.” Kahlo, who was actually 16, apparently played pranks on the artist. She stole his lunch and soaped the steps by the stage where he was working.

Kahlo planned to become a doctor and took courses in biology, zoology and anatomy. Her knowledge of these disciplines would later add realistic touches to her portraits. She also had a passion for philosophy, which she liked to flaunt. According to biographer Herrera, she would cry out to her boyfriend, Alejandro Gómez Arias, “lend me your Spengler. I don’t have anything to read on the bus.” Her bawdy sense of humor and passion for fun were well known among her circle of friends, many of whom would become leaders of the Mexican left.

Then, on September 17, 1925, the bus on which she and her boyfriend were riding home from school was rammed by a trolley car. A metal handrail broke off and pierced her pelvis. Several people died at the site, and doctors at the hospital where the 18-year-old Kahlo was taken did not think she would survive. Her spine was fractured in three places, her pelvis was crushed and her right leg and foot were severely broken. The first of many operations she would endure over the years brought only temporary relief from pain. “In this hospital,” Kahlo told Gómez Arias, “death dances around my bed at night.” She spent a month in the hospital and was later fitted with a plaster corset, variations of which she would be compelled to wear throughout her life.

Confined to bed for three months, she was unable to return to school. “Without giving it any particular thought,” she recalled, “I started painting.” Kahlo’s mother ordered a portable easel and attached a mirror to the underside of her bed’s canopy so that the nascent artist could be her own model.

Though she knew the works of the old masters only from reproductions, Kahlo had an uncanny ability to incorporate elements of their styles in her work. In a painting she gave to Gómez Arias, for instance, she portrayed herself with a swan neck and tapered fingers, referring to it as “Your Botticeli.”

During her months in bed, she pondered her changed circumstances. To Gómez Arias, she wrote, “Life will reveal [its secrets] to you soon. I already know it all. . . . I was a child who went about in a world of colors. . . . My friends, my companions became women slowly, I became old in instants.”

As she grew stronger, Kahlo began to participate in the politics of the day, which focused on achieving autonomy for the government-run university and a more democratic national government. She joined the Communist party in part because of her friendship with the young Italian photographer Tina Modotti, who had come to Mexico in 1923 with her then companion, photographer Edward Weston. It was most likely at a soiree given by Modotti in late 1928 that Kahlo re-met Rivera.

They were an unlikely pair. The most celebrated artist in Mexico and a dedicated Communist, the charismatic Rivera was more than six feet tall and tipped the scales at 300 pounds. Kahlo, 21 years his junior, weighed 98 pounds and was 5 feet 3 inches tall. He was ungainly and a bit misshapen; she was heart-stoppingly alluring. According to Herrera, Kahlo “started with dramatic material: nearly beautiful, she had slight flaws that increased her magnetism.” Rivera described her “fine nervous body, topped by a delicate face,” and compared her thick eyebrows, which met above her nose, to “the wings of a blackbird, their black arches framing two extraordinary brown eyes.”

Rivera courted Kahlo under the watchful eyes of her parents. Sundays he visited the Casa Azul, ostensibly to critique her paintings. “It was obvious to me,” he later wrote, “that this girl was an authentic artist.” Their friends had reservations about the relationship. One Kahlo pal called Rivera “a pot-bellied, filthy old man.” But Lupe Marín, Rivera’s second wife, marveled at how Kahlo, “this so-called youngster,” drank tequila “like a real mariachi.”

The couple married on August 21, 1929. Kahlo later said her parents described the union as a “marriage between an elephant and a dove.” Kahlo’s 1931 Colonial-style portrait, based on a wedding photograph, captures the contrast. The newlyweds spent almost a year in Cuernavaca while Rivera executed murals commissioned by the American ambassador to Mexico, Dwight Morrow. Kahlo was a devoted wife, bringing Rivera lunch every day, bathing him, cooking for him. Years later Kahlo would paint a naked Rivera resting on her lap as if he were a baby.

With the help of Albert Bender, an American art collector, Rivera obtained a visa to the United States, which previously had been denied him. Since Kahlo had resigned from the Communist party when Rivera, under siege from the Stalinists, was expelled, she was able to accompany him. Like other left-wing Mexican intellectuals, she was now dressing in flamboyant native Mexican costume—embroidered tops and colorful, floor-length skirts, a style associated with the matriarchal society of the region of Tehuantepec. Rivera’s new wife was “a little doll alongside Diego,” Edward Weston wrote in his journal in 1930. “People stop in their tracks to look in wonder.”

The Riveras arrived in the United States in November 1930, settling in San Francisco while Rivera worked on murals for the San Francisco Stock Exchange and the California School of Fine Arts, and Kahlo painted portraits of friends. After a brief stay in New York City for a show of Rivera’s work at the Museum of Modern Art, the couple moved on to Detroit, where Rivera filled the Institute of Arts’ garden court with compelling industrial scenes, and then back to New York City, where he worked on a mural for Rockefeller Center. They stayed in the United States for three years. Diego felt he was living in the future; Frida grew homesick. “I find that Americans completely lack sensibility and good taste,” she observed. “They are boring and they all have faces like unbaked rolls.”

In Manhattan, however, Kahlo was exhilarated by the opportunity to see the works of the old masters firsthand. She also enjoyed going to the movies, especially those starring the Marx Brothers or Laurel and Hardy. And at openings and dinners, she and Rivera met the rich and the renowned.

But for Kahlo, despair and pain were never far away. Before leaving Mexico, she had suffered the first in a series of miscarriages and therapeutic abortions. Due to her trolley-car injuries, she seemed unable to bring a child to term, and every time she lost a baby, she was thrown into a deep depression. Moreover, her polio-afflicted and badly injured right leg and foot often troubled her. While in Michigan, a miscarriage cut another pregnancy short. Then her mother died. Up to that time she had persevered. “I am more or less happy,” she had written to her doctor, “because I have Diego and my mother and my father whom I love so much. I think that is enough. . . . ” Now her world was starting to fall apart.

Kahlo had arrived in America an amateur artist. She had never attended art school, had no studio and had not yet focused on any particular subject matter. “I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best,” she would say years later. Her biographers report that despite her injuries she regularly visited the scaffolding on which Rivera worked in order to bring him lunch and, they speculate, to ward off alluring models. As she watched him paint, she learned the fundamentals of her craft. His imagery recurs in her pictures along with his palette—the sunbaked colors of pre- Columbian art. And from him—though his large-scale wall murals depict historical themes, and her small-scale works relate her autobiography—she learned how to tell a story in paint.

Works from her American period reveal her growing narrative skill. In Self-Portrait on the Borderline betweenMexico and the United States, Kahlo’s homesickness finds expression in an image of herself standing between a pre-Columbian ruin and native flowers on one side and Ford Motor Company smokestacks and looming skyscrapers on the other. In HenryFordHospital, done soon after her miscarriage in Detroit, Kahlo’s signature style starts to emerge. Her desolation and pain are graphically conveyed in this powerful depiction of herself, nude and weeping, on a bloodstained bed. As she would do time and again, she exorcises a devastating experience through the act of painting.

When they returned to Mexico toward the end of 1933, both Kahlo and Rivera were depressed. His RockefellerCenter mural had created a controversy when the owners of the project objected to the heroic portrait of Lenin he had included in it. When Rivera refused to paint out the portrait, the owners had the mural destroyed. (Rivera later re-created a copy for the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City.) To a friend Kahlo wrote, Diego “thinks that everything that is happening to him is my fault, because I made him come [back] to Mexico. . . . ” Kahlo herself became physically ill, as she was prone to do in times of stress. Whenever Rivera, a notorious philanderer, became involved with other women, Kahlo succumbed to chronic pain, illness or depression. When he returned home from his wanderings, she would usually recover.

Seeking a fresh start, the Riveras moved into a new home in the upscale San Angel district of Mexico City. The house, now the Diego Rivera Studio museum, featured his-and-her, brightly colored (his was pink, hers, blue) Le Corbusier-like buildings connected by a narrow bridge. Though the plans included a studio for Kahlo, she did little painting, as she was hospitalized three times in 1934. When Rivera began an affair with her younger sister, Cristina, Kahlo moved into an apartment. A few months later, however, after a brief dalliance with the sculptor Isamu Noguchi, Kahlo reconciled with Rivera and returned to San Angel.

In late 1936, Rivera, whose leftist sympathies were more pronounced than ever, interceded with Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas to have the exiled Leon Trotsky admitted to Mexico. In January 1937, the Russian revolutionary took up a two-year residency with his wife and bodyguards at the Casa Azul, Kahlo’s childhood home, available because Kahlo’s father had moved in with one of her sisters. In a matter of months, Trotsky and Kahlo became lovers. “El viejo” (“the old man”), as she called him, would slip her notes in books. She painted a mesmerizing fulllength portrait of herself (far right), in bourgeois finery, as a gift for the Russian exile. But this liaison, like most of her others, was short lived.

The French Surrealist André Breton and his wife, Jacqueline Lamba, also spent time with the Riveras in San Angel. (Breton would later offer to hold an exhibition of Kahlo’s work in Paris.) Arriving in Mexico in the spring of 1938, they stayed for several months and joined the Riveras and the Trotskys on sight-seeing jaunts. The three couples even considered publishing a book of their conversations. This time, it was Frida and Jacqueline who bonded.

Although Kahlo would claim her art expressed her solitude, she was unusually productive during the time spent with the Trotskys and the Bretons. Her imagery became more varied and her technical skills improved. In the summer of 1938, the actor and art collector Edward G. Robinson visited the Riveras in San Angel and paid $200 each for four of Kahlo’s pictures, among the first she sold. Of Robinson’s purchase she later wrote, “For me it was such a surprise that I marveled and said: ‘This way I am going to be able to be free, I’ll be able to travel and do what I want without asking Diego for money.’”

Shortly after, Kahlo went to New York City for her first one-person show, held at the Julien Levy Gallery, one of the first venues in America to promote Surrealist art. In a brochure for the exhibition, Breton praised Kahlo’s “mixture of candour and insolence.” On the guest list for the opening were artist Georgia O’Keeffe, to whom Kahlo later wrote a fan letter, art historian Meyer Schapiro and Vanity Fair editor Clare Boothe Luce, who commissioned Kahlo to paint a portrait of a friend who had committed suicide. Upset by the graphic nature of Kahlo’s completed painting, however, Luce wanted to destroy it but in the end was persuaded not to. The show was a critical success. Time magazine noted that “the flutter of the week in Manhattan was caused by the first exhibition of paintings by famed muralist Diego Rivera’s . . . wife, Frida Kahlo. . . . Frida’s pictures, mostly painted in oil on copper, had the daintiness of miniatures, the vivid reds and yellows of Mexican tradition, the playfully bloody fancy of an unsentimental child.” A little later, Kahlo’s hand, bedecked with rings, appeared on the cover of Vogue .

Heady with success, Kahlo sailed to France, only to discover that Breton had done nothing about the promised show. A disappointed Kahlo wrote to her latest lover, portrait photographer Nickolas Muray: “It was worthwhile to come here only to see why Europe is rottening, why all this people—good for nothing—are the cause of all the Hitlers and Mussolinis.” Marcel Duchamp— “The only one,” as Kahlo put it, “who has his feet on the earth, among all this bunch of coocoo lunatic sons of bitches of the Surrealists”—saved the day. He got Kahlo her show. The Louvre purchased a self-portrait, its first work by a 20th-century Mexican artist. At the exhibition, according to Rivera, artist Wassily Kandinsky kissed Kahlo’s cheeks “while tears of sheer emotion ran down his face.” Also an admirer, Pablo Picasso gave Kahlo a pair of earrings shaped like hands, which she donned for a later self-portrait. “Neither Derain, nor I, nor you,” Picasso wrote to Rivera, “are capable of painting a head like those of Frida Kahlo.”

Returning to Mexico after six months abroad, Kahlo found Rivera entangled with yet another woman and moved out of their San Angel house and into the Casa Azul. By the end of 1939 the couple had agreed to divorce.

Intent on achieving financial independence, Kahlo painted more intensely than ever before. “To paint is the most terrific thing that there is, but to do it well is very difficult,” she would tell the group of students—known as Los Fridos—to whom she gave instruction in the mid-1940s. “It is necessary . . . to learn the skill very well, to have very strict self-discipline and above all to have love, to feel a great love for painting.” It was during this period that Kahlo created some of her most enduring and distinctive work. In self-portraits, she pictured herself in native Mexican dress with her hair atop her head in traditional braids. Surrounded by pet monkeys, cats and parrots amid exotic vegetation reminiscent of the paintings of Henri Rousseau, she often wore the large pre-Columbian necklaces given to her by Rivera.

In one of only two large canvases ever painted by Kahlo, The Two Fridas, a double self-portrait done at the time of her divorce, one Frida wears a European outfit torn open to reveal a “broken” heart; the other is clad in native Mexican costume. Set against a stormy sky, the “twin sisters,” joined together by a single artery running from one heart to the other, hold hands. Kahlo later wrote that the painting was inspired by her memory of an imaginary childhood friend, but the fact that Rivera himself had been born a twin may also have been a factor in its composition. In another work from this period, Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940), Kahlo, in a man’s suit, holds a pair of scissors she has used to sever the locks that surround the chair on which she sits. More than once when she discovered Rivera with other women, she had cut off the long hair that he adored.

Despite the divorce, Kahlo and Rivera remained connected. When Kahlo’s health deteriorated, Rivera sought medical advice from a mutual friend, San Francisco doctor Leo Eloesser, who felt her problem was “a crisis of nerves.” Eloesser suggested she resolve her relationship with Rivera. “Diego loves you very much,” he wrote, “and you love him. It is also the case, and you know it better than I, that besides you, he has two great loves—1) Painting 2) Women in general. He has never been, nor ever will be, monogamous.” Kahlo apparently recognized the truth of this observation and resigned herself to the situation. In December 1940, the couple remarried in San Francisco.

The reconciliation, however, saw no diminution in tumult. Kahlo continued to fight with her philandering husband and sought out affairs of her own with various men and women, including several of his lovers. Still, Kahlo never tired of setting a beautiful table, cooking elaborate meals (her stepdaughter Guadalupe Rivera filled a cookbook with Kahlo’s recipes) and arranging flowers in her home from her beloved garden. And there were always festive occasions to celebrate. At these meals, recalled Guadalupe, “Frida’s laughter was loud enough to rise above the din of yelling and revolutionary songs.”

During the last decade of her life, Kahlo endured painful operations on her back, her foot and her leg. (In 1953, her right leg had to be amputated below the knee.) She drank heavily—sometimes downing two bottles of cognac a day—and she became addicted to painkillers. As drugs took control of her hands, the surface of her paintings became rough, her brushwork agitated.

In the spring of 1953, Kahlo finally had a one-person show in Mexico City. Her work had previously been seen there only in group shows. Organized by her friend, photographer Lola Alvarez Bravo, the exhibition was held at Alvarez Bravo’s Gallery of Contemporary Art. Though still bedridden following the surgery on her leg, Kahlo did not want to miss the opening night. Arriving by ambulance, she was carried to a canopied bed, which had been transported from her home. The headboard was decorated with pictures of family and friends; papier-mâché skeletons hung from the canopy. Surrounded by admirers, the elaborately costumed Kahlo held court and joined in singing her favorite Mexican ballads.

Kahlo remained a dedicated leftist. Even as her strength ebbed, she painted portraits of Marx and of Stalin and attended demonstrations. Eight days before she died, Kahlo, in a wheelchair and accompanied by Rivera, joined a crowd of 10,000 in Mexico City protesting the overthrow, by the CIA, of the Guatemalan president.

Although much of Kahlo’s life was dominated by her debilitated physical state and emotional turmoil, Taymor’s film focuses on the artist’s inventiveness, delight in beautiful things and playful but caustic sense of humor. Kahlo, too, preferred to emphasize her love of life and a good time. Just days before her death, she incorporated the words Viva La Vida (Long Live Life) into a still life of watermelons. Though some have wondered whether the artist may have intentionally taken her own life, others dismiss the notion. Certainly, she enjoyed life fully and passionately. “It is not worthwhile,” she once said, “to leave this world without having had a little fun in life.”

Get the latest Travel & Culture stories in your inbox.

Articles and Features

Female Iconoclasts: Frida Kahlo

By Shira Wolfe

“I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality. The only thing I know is that I paint because I need to, and I paint whatever passes through my head without any other consideration.” Frida Kahlo

Who is Frida Kahlo?

Our “Female Iconoclasts” series highlights some of the most boundary-breaking works of our time, crafted by women who defied conventions in contemporary art and society in order to pursue their passion and contribute their unique vision to the world. This week, we focus on Frida Kahlo, one of the greatest artistic icons ever to have lived, whose life has become just as iconic as her body of work. Her art was deeply personal and political, reflecting her own turbulent personal life, her physical ailments, her relationship with the great muralist Diego Rivera , and the Mexico she so loved and fought for. Since the 1970s she has grown into a feminist icon and the past decade has seen her persona and art become co-opted by pop culture.

During her lifetime she was called a ‘surrealist’ by André Breton, and a ‘realist’ by her husband Diego Rivera. Kahlo, however, eschewed labels; in fact, one of the most famous quotes by the artist reads: “I paint my own reality. The only thing I know is that I paint because I need to, and I paint whatever passes through my head without any other consideration.”

Biography of Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo was born as Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo Calderón on 6 July 1907 in the Casa Azul, her family home in the Mexico City municipality Coyoacán.

The Family of Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo’s father, Wilhelm (Guillermo) Kahlo, was a photographer of German-Jewish descent who had immigrated to Mexico. Her mother was the Mexican Matilde Calderón. Frida had three sisters, Matilde, Adriana, and Cristina.

The Early Life of Frida Kahlo

Frida’s early life was marked by severe health issues. At the age of 6, she contracted polio, causing her right leg to remain slightly shorter than the left one. At 18, she suffered a tragic accident that would haunt her for the rest of her life: a streetcar crashed into the bus she was travelling in, and she was terribly injured: she was impaled by the metal bannister, fractured many bones, suffered severe damage to her spinal cord, and dislocated her shoulder and foot. During the hard recuperation period, she lay practically immobilized in her bed and took up painting. Her mother had an easel built that allowed her to paint while lying in bed and mounted a mirror above her bed so she could paint herself.

For Frida, painting became a mode of survival and self-expression, which helped her to cope with her tortuous chronic pain, prolonged periods of bed rest and physical fragility that frustrated the enigmatic woman with such a lust for life. Throughout her life, Frida underwent several intense operations in order to attempt to improve the quality of her life following the accident. These operations were followed by long convalescences and had serious consequences, including having to wear corsets to correct her posture and suffering three miscarriages.

The Relationship with Diego Rivera

The other event that shook Frida’s life to the core was her meeting and forming a relationship with renowned artist Diego Rivera. Diego was a huge supporter of her art and started frequenting the Casa Azul. The couple married in 1929, when Rivera was 43 years old, and Frida just 22. Their marriage was described by Frida’s mother as “the wedding between an elephant and a dove.” The love between Frida and Diego was strong and passionate, yet their relationship was also volatile and tumultuous, with many affairs on both sides shaking things up. On an artistic level, they supported each other unconditionally and each considered the other to be the greatest living Mexican painter. They also shared a passion for politics and the revolutionary ideals of the time. Both were affiliated with the Communist Party of Mexico, and they even took in the Russian dissident Leon Trotsky for two years, between 1937 and 1939, who was being persecuted by Stalin. The couple resided in different intervals at the Casa Azul, at Diego’s studio in San Ángel, in Cuernavaca, and in various cities in the United States. Frida and Diego spent three years in the United States from 1930 to 1933, living in New York, Detroit and San Francisco.

Following deep emotional crises as a result of Diego’s many infidelities, Frida divorced him in 1939, only to remarry him one year later with a mutual agreement that they would lead autonomous sex lives.

How Frida Kahlo Died

Toward the end of her life, Frida’s health deteriorated and she was confined to the Hospital Inglés from 1950 to 1951. Her right leg was amputated in 1953, due to a threat of gangrene, and Frida died at the Casa Azul on 13 July 1954. The National Institute of Fine Arts was just in the process of preparing a retrospective exhibition as a national tribute to her. Following her wishes, the Casa Azul was turned into a museum several years after her death, and it remains one of the most important spaces in Mexico, filled with her being and her objects.

“ I paint self-portraits because I am the person I know best. I paint my own reality. The only thing I know is that I paint because I need to and I paint whatever passes through my head without any consideration .” Frida Kahlo

Themes, styles and approach

Frida Kahlo found a way to express herself and survive the difficult episodes in her life through art. She was determined to paint her own reality, and two-thirds of her paintings are self-portraits, revealing her keen interest in exploring her own being and identity in depth. She once said: “I paint self-portraits because I am the person I know best. I paint my own reality. The only thing I know is that I paint because I need to and I paint whatever passes through my head without any consideration.” Her self-portraits are beautiful and honest, showing images of herself with her signature moustache and unibrow, and in moments of suffering and pain, as such boldly defying conventional beauty norms.

At the same time, Frida was interested in reclaiming the roots of Mexican folk art and culture through her daily life and her art. She dressed in indigenous Mexican attire and avidly collected Mexican folk art. All these influences were reflected in her painting. Although the Surrealists tried to claim her as one of their own and Frida was interested in their work, she preferred to avoid any labels when it came to her art. For her, the surrealist images in her paintings were actually her reality. She never painted her dreams, but painted what was happening to her and passing through her mind at that very moment.

The Most Famous Art by Frida Kahlo

The two fridas.

Frida painted The Two Fridas in 1939, the year she divorced Diego Rivera. The painting shows two Frida Kahlos sitting side by side. Both their hearts are revealed, and they are distinguished from one another through their clothing. The one on the left wears a traditional Tehuana costume and her heart is torn open; the one on the right wears a more modern outfit. The main artery leading from the torn open heart of the traditional Frida connects to the modern Frida’s heart, wraps around her arm, and is cut off with a pair of scissors by the traditional Frida. The modern Frida holds a pendant with a portrait of a young Diego Rivera. This powerful painting shows two sides of Frida Kahlo, suffering from heartache while also remembering the good aspects of her love for Diego.

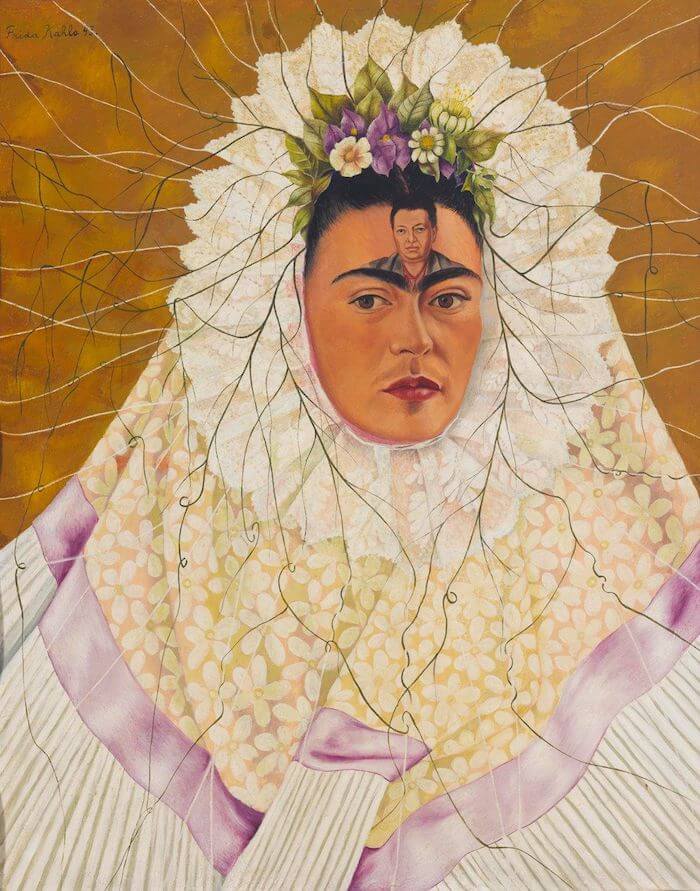

Diego on My Mind (Self-Portrait as a Tehuana)

Frida started painting Diego on My Mind (Self-Portrait as a Tehuana) in 1940 when the couple were still divorced, and finished it in 1943, at which point they had reconciled. The painting shows Frida wearing a traditional Tehuana costume, with the face of Diego as a third eye in her forehead. The painting shows how she cannot stop thinking about him, despite his betrayals and their separation.

The Broken Column

The Broken Column is a painting from 1944. It depicts Frida after spinal surgery, bound and constrained by a cage-like body brace. She is missing flesh, and a broken column is exposed where her spine should be. Metal nails pierce Frida’s face, breasts, arms, torso and upper thigh, and tears are streaming down her face. This is one of her most brutally revealing self-portraits where she deals with her physical suffering.

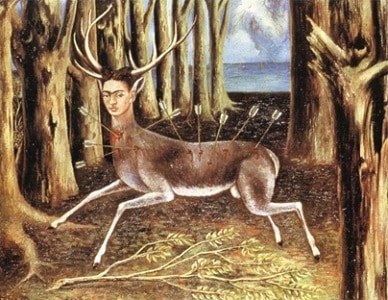

The Wounded Deer

The Wounded Deer is a 1946 painting, which Frida painted following another spinal operation in New York that same year. We see Frida as a young deer in the forest, fatally wounded by several arrows. She had hoped that the New York surgery would free her from her severe physical pain, but it failed, and this painting expresses her disappointment following the procedure.

Where to Find Frida Kahlo’s Work

During her lifetime, Frida held several exhibitions internationally: at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York, at the Renou et Colle Gallery in Paris, and at the Lola Álvarez Bravo Gallery in Mexico. She also participated in the Group Surrealist Show at the Mexican Art Gallery. In 1939, The Louvre acquired her painting The Frame (1938). Today, Frida Kahlo’s paintings can be found in numerous private collections in Mexico, the United States, and Europe. A current exhibition at the Cobra Museum in Amstelveen, the Netherlands, brought together an impressive selection of works by Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera and several other Mexican contemporaries of theirs. But by far the most moving experience is to experience the full essence of Frida Kahlo in her Casa Azul in Mexico City, which is still left almost exactly in the same condition as when Frida herself lived there. Several of her and Diego Rivera’s paintings are on display there, as well as the Mexican folk art that they collected, and the many objects that were important to Frida.

Frequently Asked Questions

Frida Kahlo was born in Casa Azul, her family home in the Mexico City Coyoacán.

Frida Kahlo died at an age of 47.

Relevant sources to learn more

The excellent exhibition “Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera: A Love Revolution” is on show at the Cobra Museum of Modern Art in Amstelveen, the Netherlands through 26 September 2021

Discover the art of María Izquierdo, a contemporary of Kahlo and Rivera who was far less known but also made an important contribution to Mexican art

Read more about Art Movements and Styles Throughout History here

You may also like: The Fantastic Women of Surrealism

Frida Kahlo

Mexican Painter

Summary of Frida Kahlo

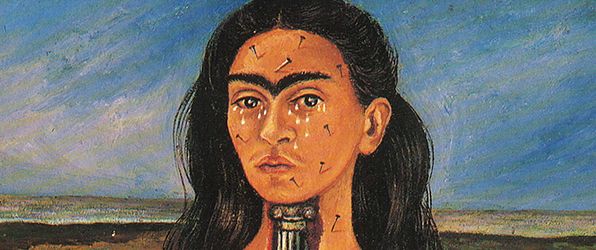

Small pins pierce Kahlo's skin to reveal that she still 'hurts' following illness and accident, whilst a signature tear signifies her ongoing battle with the related psychological overflow. Frida Kahlo typically uses the visual symbolism of physical pain in a long-standing attempt to better understand emotional suffering. Prior to Kahlo's efforts, the language of loss, death, and selfhood, had been relatively well investigated by some male artists (including Albrecht Dürer , Francisco Goya , and Edvard Munch ), but had not yet been significantly dissected by a woman. Indeed not only did Kahlo enter into an existing language, but she also expanded it and made it her own. By literally exposing interior organs, and depicting her own body in a bleeding and broken state, Kahlo opened up our insides to help explain human behaviors on the outside. She gathered together motifs that would repeat throughout her career, including ribbons, hair, and personal animals, and in turn created a new and articulate means to discuss the most complex aspects of female identity. As not only a 'great artist' but also a figure worthy of our devotion, Kahlo's iconic face provides everlasting trauma support and she has influence that cannot be underestimated.

Accomplishments

- Kahlo made it legitimate for women to outwardly display their pains and frustrations and to thus make steps towards understanding them. It became crucial for women artists to have a female role model and this is the gift of Frida Kahlo.

- As an important question for many Surrealists , Kahlo too considers: What is Woman? Following repeated miscarriages, she asks: to what extent does motherhood or its absence impact on female identity? She irreversibly alters the meaning of maternal subjectivity. It becomes clear through umbilical symbolism (often shown by ribbons) that Kahlo is connected to all that surrounds her, and that she is a 'mother' without children.

- Finding herself often alone, she worked obsessively with self-portraiture. Her reflection fueled an unflinching interest in identity. She was particularly interested in her mixed German-Mexican ancestry, as well as in her divided roles as artist, lover, and wife.

- Kahlo uses religious symbolism throughout her oeuvre . She appears as the Madonna holding her 'animal babies', and becomes the Virgin Mary as she cradles her husband and famous national painter Diego Rivera . She identifies with Saint Sebastian, and even fittingly appears as the martyred Christ. She positions herself as a prophet when she takes to the head of the table in her Last Supper -style painting, and her depiction of the accident which left her impaled on a metal bar (and covered in gold dust when lying injured) recalls the crucifixion and suggests her own holiness.

- Women prior to Kahlo who had attempted to communicate the wildest and deepest of emotions were often labeled hysterical or condemned insane - while men were aligned with the 'melancholy' character type. By remaining artistically active under the weight of sadness, Kahlo revealed that women too can be melancholy rather than depressed, and that these terms should not be thought of as gendered.

The Life of Frida Kahlo

"I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone... because I am the subject I know best." From battles with her mind and her body, Kahlo lived through her art.

Important Art by Frida Kahlo

Frieda and Diego Rivera

It is as if in this painting Kahlo tries on the role of wife to see how it fits. She does not focus on her identity as a painter, but instead adopts a passive and supportive role, holding the hand of her talented and acclaimed husband. It was indeed the case that during the majority of her painting career, Kahlo was viewed only in Rivera's shadow and it was not until later in life that she gained international recognition. This early double-portrait was painted primarily to mark the celebration of Kahlo's marriage to Rivera. Whilst Rivera holds a palette and paint brushes, symbolic of his artistic mastery, Kahlo limits her role to his wife by presenting herself slight in frame and without her artistic accoutrements. Kahlo furthermore dresses in costume typical of the Mexican woman, or "La Mexicana," wearing a traditional red shawl known as the rebozo and jade Aztec beads. The positioning of the figures echoes that of traditional marital portraiture where the wife is placed on her husband's left to indicate her lesser moral status as a woman. In a drawing made the following year called Frida and the Miscarriage , the artist does hold her own palette, as though the experience of losing a fetus and not being able to create a baby shifts her determination wholly to the creation of art.

Oil on canvas - San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Henry Ford Hospital

Many of Kahlo's paintings from the early 1930s, especially in size, format, architectural setting and spatial arrangement, relate to religious ex-voto paintings of which she and Rivera possessed a large collection ranging in date over several centuries. Ex-votos are made as a gesture of gratitude for salvation, a granted prayer or disaster averted and left in churches or at shrines. Ex-votos are generally painted on small-scale metal panels and depict the incident along with the Virgin or saint to whom they are offered. Henry Ford Hospital , is a good example where the artist uses the ex-voto format but subverts it by placing herself centre stage, rather than recording the miraculous deeds of saints. Kahlo instead paints her own story, as though she becomes saintly and the work is made not as thanks to the lord but in defiance, questioning why he brings her pain. In this painting, Kahlo lies on a bed, bleeding after a miscarriage. From the exposed naked body six vein-like ribbons flow outwards, attached to symbols. One of these six objects is a fetus, suggesting that the ribbons could be a metaphor for umbilical cords. The other five objects that surround Frida are things that she remembers, or things that she had seen in the hospital. For example, the snail makes reference to the time it took for the miscarriage to be over, whilst the flower was an actual physical object given to her by Diego. The artist demonstrates her need to be attached to all that surrounds her: to the mundane and metaphorical as much as the physical and actual. Perhaps it is through this reaching out of connectivity that the artist tries to be 'maternal', even though she is not able to have her own child.

Oil on canvas - Dolores Olmedo Collection, Mexico City, Mexico

This is a haunting painting in which both the birth giver and the birthed child seem dead. The head of the woman giving birth is shrouded in white cloth while the baby emerging from the womb appears lifeless. At the time that Kahlo painted this work, her mother had just died so it seems reasonable to assume that the shrouded funerary figure is her mother while the baby is Kahlo herself (the title supports this reading). However, Kahlo had also just lost her own child and has said that she is the covered mother figure. The Virgin of Sorrows , who hangs above the bed suggests that this is an image that overflows with maternal pain and suffering. Also though, and revealingly, Kahlo wrote in her diary, next to several small drawings of herself, 'the one who gave birth to herself ... who wrote the most wonderful poem of her life.' Similar to the drawing, Frida and the Miscarriage , My Birth represents Kahlo mourning for the loss of a child, but also finding the strength to make powerful art because of such trauma. The painting is made in a retablo (or votive) style (a small traditional Mexican painting derived from Catholic Church art) in which thanks would typically be given to the Madonna beneath the image. Kahlo instead leaves this section blank, as though she finds herself unable to give thanks either for her own birth, or for the fact that she is now unable to give birth. The painting seems to bring the message that it is important to acknowledge that birth and death live very closely together. Many believe that My Birth was heavily inspired by an Aztec sculpture that Kahlo had at home representing Tiazolteotl, the Goddess of fertility and midwives.

Oil and tempera on zinc - Private Collection

My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (Family Tree)

This dream-like family tree was painted on zinc rather than canvas, a choice that further highlights the artist's fascination with and collection of 18 th -century and 19 th -century Mexican retablos. Kahlo completed this work to accentuate both her European Jewish heritage and her Mexican background. Her paternal side, German Jewish, occupies the right side of the composition symbolized by the sea (acknowledging her father's voyage to get to Mexico), while her maternal side of Mexican descent is represented on the left by a map faintly outlining the topography of Mexico. While Kahlo's paintings are assertively autobiographical, she often used them to communicate transgressive or political messages: this painting was completed shortly after Adolf Hitler passed the Nuremberg laws banning interracial marriage. Here, Kahlo simultaneously affirms her mixed heritage to confront Nazi ideology, using a format - the genealogical chart - employed by the Nazi party to determine racial purity. Beyond politics, the red ribbon used to link the family members echoes the umbilical cord that connects baby Kahlo to her mother - a motif that recurs throughout Kahlo's oeuvre .

Oil and tempera on zinc - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Fulang-Chang and I

This painting debuted at Kahlo's exhibition in Julien Levy's New York gallery in 1938, and was one of the works that most fascinated André Breton, the founder of Surrealism. The canvas in the New York show is a self-portrait of the artist and her spider monkey, Fulang-Chang, a symbol employed as a surrogate for the children that she and Rivera could not have. The arrangement of figures in the portrait signals the artist's interest in Renaissance paintings of the Madonna and child. After the New York exhibition, a second frame containing a mirror was added. The later inclusion of the mirror is a gesture inviting the viewer into the work: it was through looking at herself intensely in a mirror in her months spent at home after her bus accident that Kahlo first began painting portraits and delving deeper into her psyche. The inclusion of the mirror, considered from this perspective, is a remarkably intimate vision into both the artist's aesthetic process and into her personal introspection. In many of Kahlo's self-portraits, she is accompanied by monkeys, dogs, and parrots, all of which she kept as pets. Since the Middle Ages, small spider monkeys, like those kept by Kahlo, have been said to symbolize the devil, heresy, and paganism, finally coming to represent the fall of man, vice, and the embodiment of lust. These monkeys were depicted in the past as a cautionary symbol against the dangers of excessive love and the base instincts of man. Kahlo again depicts herself with her monkey in both 1939 and 1940. In a later version in 1945, Kahlo paints her monkey and also her dog, Xolotl. This little dog that often accompanies the artist, is named after a mythological Aztec god, known to represent lightning and death, and also to be the twin of Quetzalcoatl, both of who had visited the underworld. All of these pictures, including Fulang-Chang and I include 'umbilical' ribbons that wrap between Kahlo's and the animal's necks. Kahlo is the Madonna and her pets become the holy (yet darkly symbolic) infant for which she longs.

In two parts, oil on composition board (1937) with painted mirror frame (added after 1939) - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

What the Water Gave Me

In this painting most of Kahlo's body is obscured from view. We are unusually confronted with the foot and plug end of the bath, and with focus placed on the artist's feet. Furthermore, Kahlo adopts a birds-eye view and looks down on the water from above. Within the water, Kahlo paints an alternative self-portrait, one in which the more traditional facial portrait has been replaced by an array of symbols and recurring motifs. The artist includes portraits of her parents, a traditional Tehuana dress, a perforated shell, a dead humming bird, two female lovers, a skeleton, a crumbling skyscraper, a ship set sail, and a woman drowning. This painting was featured in Breton's 1938 book on Surrealism and Painting and Hayden Herrera, in her biography of Kahlo, mentions that the artist herself considered this work to have a special importance. Recalling the tapestry style painting of Northern Renaissance masters, Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder, the figures and objects floating in the water of Kahlo's painting create an at once fantastic and real landscape of memory. Kahlo discussed What the Water Gave Me with the Manhattan gallery owner Julien Levy, and suggested that it was a sad piece that mourned the loss of her childhood. Perhaps the strangled figure at the centre is representative of the inner emotional torments experienced by Kahlo herself. It is clear from the conversation that the artist had with Levy, that Kahlo was aware of the philosophical implications of her work. In an interview with Herrera, Levy recalls, in 'a long philosophical discourse, Kahlo talked about the perspective of herself that is shown in this painting'. He further relays that 'her idea was about the image of yourself that you have because you do not see your head. The head is something that is looking, but is not seen. It is what one carries around to look at life with.' The artist's head in What the Water Gave Me is thus appropriately replaced by the interior thoughts that occupy her mind. As well as an inclusion of death by strangulation in the centre of the water, there is also a labia-like flower and a cluster of pubic hair painted between Kahlo's legs. The work is quite sexual while also showing preoccupation with destruction and death. The motif of the bathtub in art is one that has been popular since Jacques-Louis David's The Death of Marat (1793), and was later taken up many different personalities such as Francesca Woodman and Tracey Emin.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

The Two Fridas