International Perspectives in Values-Based Mental Health Practice pp 27–35 Cite as

Antonella: ‘A Stranger in the Family’—A Case Study of Eating Disorders Across Cultures

- Vincenzo Di Nicola 6 , 7

- Open Access

- First Online: 12 December 2020

7388 Accesses

2 Citations

7 Altmetric

The story of Antonella illustrates the way in which cultural and other values impact on the presentation and treatment of eating disorders. Displaced from her European home culture to live in Canada, Antonella presents with an eating disorder and a fluctuating tableau of anxiety and mood symptoms linked to her lack of a sense of identity. These arose against a background of her adoption as a foundling child in Italy and her attachment problems with her adoptive family generating chronically unfixed and unstable identities, resulting in her cross-cultural marriage as both flight and refuge followed by intense conflicts. Her predicament is resolved only when after an extended period in cultural family therapy she establishes a deep cross-species identification by becoming a breeder of husky dogs. The wider implications of Antonella’s story for understanding the relationship between cultural values and mental health are briefly considered.

- Eating disorders

- Anorexia multiforme

- Cultural values

- Uniqueness of the individual

- Role of animals

- Cross-species identification

- Cultural family therapy

Download chapter PDF

1 Introduction

Eating disorders are a potentially fruitful area of study for understanding the links between values—in particular cultural values—and mental distress and disorder. Eating disorders show widely different prevalence rates across cultures, and much attention has been given to theories linking these differences with variations in cultural values. In particular, the cultural value placed on ‘fashionable slimness’ in the industrialised world has for some time been identified with the greater prevalence of eating disorders among women in Western societies [ 1 ]. Consistently with this view, the growing prevalence of eating disorders in other parts of the world does seem to be correlated with increasing industrialisation [ 2 , 3 ]. In my review of cultural distribution and historical evolution of eating disorders , I was so struck by its protean nature and its variability of clinical presentations of anorexia nervosa that I renamed this predicament ‘anorexia multiforme’ [ 4 , 5 ].

The story of Antonella that follows illustrates the potential importance of contemporary theories linking cultural values with eating disorders though also some of their limitations.

2 Case Narrative: Antonella’s Story

Ottawa in the early 1990s. Antonella Trevisan, a 24-year-old woman, was referred to me by an Italian psychiatrist and family therapist, Dr. Claudio Angelo, who had treated her in Italy [ 6 ] . When Antonella came to Canada to live with a man she had met through her work, Dr. Angelo referred her to me. Antonella’s presenting problems concerned two areas of her life: her eating problems, which emerged after her emigration from Italy, and her relationship with her partner in Canada.

2.1 Antonella’s Predicament

My initial psychiatric consultation (conducted in Italian) revealed the complexities of Antonella’s life. This was reflected in the difficulty of making an accurate diagnosis. Her food-related problems had some features of eating disorders , such as restriction of intake, the resulting weight loss, and a history of weight gain and being teased for it. What was missing was the ‘psychological engine’ of an eating disorder: a drive for thinness or a morbid fear of fatness. Her problem was perhaps better understood as a food-related anxiety arising from a ‘globus’ sensation (lump in the throat) and a learned avoidance response that generalized from one specific situation to eating in any context.

Although it was clear that her weight gain in late adolescence and the teasing and insults from her mother had sensitized her, other factors had to be considered. Antonella showed an exquisite rejection sensitivity that both arose from and was a metaphor for the circumstances of her birth and adoption. Her migration to Canada also seemed to generate anxieties and uncertainties, and there were hints of conflicts with her partner. Was she also re-enacting another, earlier trauma? In the first journey of her life, she was given up by her birth mother (or taken away?) and left on the steps of a foundry. In the first year of her life, Antonella had shown failure to thrive and developmental delays. And she had, at best, an insecure attachment to her adoptive family, predisposing her to lifelong insecurities.

2.2 A Therapeutic Buffet

After my assessment, we faced a choice: whether to treat the eating problem concretely, in purely behavioral terms, or more metaphorically, with some form of psychotherapy. Given the stabilization of her eating pattern and her weight and the larger context of her predicament, we negotiated to do psychotherapy. There were several components to her therapy. Starting with a psychiatric consultation, three types of therapy were negotiated, with Antonella sampling a kind of ‘therapeutic buffet’ over a period of some 2 years: individual therapy for Antonella, couple therapy for Antonella and Rick, and brief family therapy with Antonella’s adoptive family visiting from Italy.

The individual work with Antonella was at first exploratory, getting to know the complex bicultural world of the Italian Alps, how she experienced the move to Canada, examining her choices to move here and live with Rick. Sessions were conducted in a mix of Italian and English. At first, the Italian language was like a ‘transitional object’ in her acculturation process; slowly, as she gained confidence in her daily life, English began to dominate her sessions. Under stress, however, she would revert to Italian. I could follow her progress just by noting the balance of Italian and English in each session. This does not imply any superiority of English or language preferences; rather, it acknowledges the social realities of culture making its demands felt even in private encounters. This is the territory of sociolinguistics [ 7 , 8 ] . Like Italian, these individual sessions were a secure home base to which Antonella returned during times of stress or between other attempts to find solutions.

After some months in Canada and the stabilization of her eating problems, Antonella became more invested in examining her relationship to Rick. They had met through work while she was still in Italy. After communicating on the telephone, she daringly took him up on an offer to visit. During her holiday in Canada, a romance developed. After her return to Italy, Antonella made the extraordinary decision to emigrate, giving up an excellent position in industry, leaving her family for a country she did not know well. Rick is 22 years her senior and was only recently separated from his first wife.

In therapy she not only expressed ambivalence about her situation with Rick but enacted it. She asked for couple sessions to discuss some difficulties in their relationship. Beyond collecting basic information, couple sessions were unproductive. While Rick was frank about his physical attraction to her and his desire to have children, Antonella talked about their relationship in an oddly detached way. She could not quite articulate her concerns. As we got closer to examining the problems of their relationship, Antonella abruptly announced that they were planning their wedding. The conjoint sessions were put on hold as they dealt with the wedding arrangements.

Her parents did not approve of the marriage and boycotted the wedding. Her paternal aunt, however, agreed to come to Canada for the wedding. Since I was regarded by Antonella as part of her extended family support system, she brought her aunt to meet me. It gave me another view of Antonella’s family. Her aunt was warm and supportive of Antonella, trying to smooth over the family differences. A few months later, at Christmas time, her parents and sister visited, and Antonella brought them to meet me. To understand these family meetings, however, it is necessary to know Antonella’s early history.

2.3 A Foundling Child

Antonella was a foundling child. Abandoned on the steps of a foundry in Turin as a newborn, she was the subject of an investigation into the private medical clinics of Turin. This revealed that the staff of the clinic where she was born was ‘paid off to hide the circumstances of my birth.’ As a result, her date of birth could only be presumed because the clinic staff destroyed her birth records. She was taken into care by the state and, as her origins could not be established, she was put up for adoption.

Antonella has always tried to fill in this void of information with meaning that she draws from her own body. She questions me closely: ‘Just look at me. Don’t you think I look like a Japanese?’ She feels that her skin tone is different from other Italians, that her facial features and eyes have an ‘Asian’ cast. With a few, limited facts, and some speculation, she has constructed a personal myth: that she is the daughter of an Italian mother from a wealthy family (hence her hidden birth in a private clinic) and a Japanese father (hence her ‘Asian’ features). It is oddly reassuring to her, but also perhaps a source of her alienation from her family.

At about 6 months of age, Antonella was adopted into a family in the Italian Alps, near the border with Austria. This is a bicultural region where both Italian and German are spoken and services are available in both languages (much like Ottawa, which is bilingually English and French). Her father, Aldo, who is Italian, is a retired FIAT factory worker. Annalise, her mother, who is a homemaker, had an Italian father and an Austrian mother. About her family she said, ‘I had a wonderful childhood compared to what came afterwards.’ Years after her adoption, her parents had a natural child, Oriana, who is 15.

She describes her mother as the disciplinarian at home. Her mother, she said, was ‘tough, German.’ When she visited her Austrian grandmother, no playing was allowed in that strict home. Her own mother allowed her ‘no friends in the house,’ but her father ‘was my pal when I was a kid.’ Although she had a good relationship with her father, he became ‘colder’ when she turned 13. Her parents’ relationship is remembered as cordial, but she later learned that they had many marital problems. Mother told her that she married to get away from home, but in fact she was in love with someone else. Overall, the feeling is of a rigid family organization. Her father is clearly presented by Antonella as warmer and more sociable. She experiences her mother as being ‘tough’. But she is crying all the time, feeling betrayed by everybody.

2.4 A Family Visit from the Italian Alps

When her family finally came to visit, Antonella brought them to see me. At first, the session had the quality of a student introducing out-of-town parents to her college teacher. They were pleased that I spoke Italian and knew Dr. Angelo, who they trusted. I soon found that the Trevisans were hungry to tell their story. Instead of a social exchange of pleasantries, this meeting turned into the first session of an impromptu course of brief family therapy.

Present were Antonella’s parents, Aldo and Annalise, and her sister, Oriana. Annalise led the conversation. Relegating Aldo to a support role. Oriana alternated between disdain and agitation, punctuated by bored indifference. Annalise had much to complain about: her own troubled childhood, her sense of betrayal and abandonment, heightened by Antonella’s departure from the family and from Italy. I was struck by the parallel themes of abandonment in mother and daughter. Mother clearly needed to tell this story, so I tried to set the stage for the family to hear her, what narrative therapists call ‘recruiting an audience’ [ 9 ] . I used Antonella, who I knew best, as a barometer of the progress of the session, and by that indicator, believed it had gone well.

When I saw them again some 10 days later, I was stunned by the turn of events. Oriana had assaulted her parents. The father had bandages over his face and the mother had covered her bruises with heavy make-up and dark glasses. Annalise was very upset about Oriana, who was defiant and aggressive at home. For her part, Oriana defended herself by saying she had been provoked and hit by her mother. Worried by this dangerous escalation, I tried to open some space for a healthy standoff and renegotiation.

Somehow, the concern had shifted away from Antonella to Oriana. Antonella was off the hook, but I waited for an opening to deal with this. I first tried to explore the cultural attitudes to adolescence in Italy by asking how the Italian and the German subcultures in their area understood teenagers differently. What were Oriana’s concerns? Had they seen this outburst coming? The whole family participated in a kind of sociological overview of Italian adolescence, with me as their grateful audience. The parents demonstrated keen insight and empathy. Concerned about Oriana’s experience of the session, I made a concerted effort to draw her into it. Eventually, the tone of the session lightened. Knowing they would return to Italy soon, I explored whether they had considered family work. Since they had met a few times with Dr. Angelo over Antonella’s eating problems, they were comfortable seeing Dr. Angelo as a family to find ways to understand Oriana and her concerns and for Oriana to explore other, nonviolent ways to be heard in the family. I agreed to meet them again before their departure and to communicate with Dr. Angelo about their wishes. On their way out, I wondered aloud about the apparent switch in their focus from Antonella to Oriana. The parents reassured me that they were ready to let Antonella live her own life now.

When they returned to say goodbye, we had a brief session. Oriana and Antonella were oddly buoyant and at ease. The parents were relieved. Antonella had offered the possibility of Oriana returning to spend the summer in Canada with her. I tried to connect this back to the previous session, wondering how much the two sisters supported each other. I was delighted, I said emphatically, by the family’s apparent approval of Antonella’s marriage to Rick. It was striking that, even from a distance of thousands of miles away, Antonella was still a part of the Trevisan family. And Rick was still not in the room.

3 Discussion

In this section, I will consider the impact of cultural and other values on Antonella and those around her and then look briefly at the wider implications of her story for our understanding not only of eating disorders but of mental distress and disorders in general.

3.1 Antonella: Life Before Man

The key to understanding Antonella’s attachments was her passion for her Siberian huskies. In the language of values-based practice , it was above all her huskies that mattered or were important to her. And it is not hard to see why. From the beginning of her relationship with Rick, she used her interest in dogs as a way for them to be more socially active as a couple, getting them out of the house to go to dog shows, for example. As her interests expanded, she wanted to buy bitches for breeding and to set up a kennel. Rick was only reluctantly supportive in this. Nonetheless, they ended up buying a home in the country where she could establish a kennel. Her haggling with Rick over the dogs was quite instrumental on her part, representing her own choices and interests and a test of the extent to which Rick would support her.

Yet the importance to Antonella of her huskies rests I believe on deeper cultural factors, both negative and positive. As to negative factors , these are evident in the fact that from the first days of her life, Antonella was rejected by her birth parents, literally abandoned and exposed, and later adopted by what she experienced as a non-nurturing family. Positive cultural factors , on the other hand, are evident in the way that having thrown her net wider afield, she looked initially to Canada, and to Rick, for nurturance and for identity. Then, finding herself only partly satisfied, she turned to the nonhuman world for the constancy of affection she could not find with people. Her huskies gave her pleasure, a task, and an identity. She spent many sessions discussing their progress, showing me pictures of her dogs and their awards. As it happened, my secretary at the time was also a dog lover who raised Samoyed dogs (related to huskies) and the two of them exchanged stories of dog lore.

As to positive factors , again, is there something, too, in the mythology of Canada that helps us understand Antonella? Does Canada still hold a place in the European imagination as a ‘New World’ for radical departures and identity makeovers? Or does Canada specifically represent the ‘malevolent North,’ as Margaret Atwood [ 10 ] calls it in her exploration of Canadian fiction? Huskies are a Northern animal, close to the wolf in their origins and habits. Bypassing the human world, Antonella finds her identity within a new world through its animals. If people have failed her, then she will leave not only her own tribe (Italy), but skip the identification with Canada’s Native peoples, responding to the ‘call of the wild’ to identify with a ‘life before man’ (to use another of Atwood’s evocative phrases, [ 11 ]), finding companionship and solace with her dogs.

3.2 Wider Implications of Antonella’s Story

Antonella may seem on first inspection something of an outlier to the human tribe. Orphaned from her culture of origin, she finds her place not in another country but by identification with another and altogether wilder species, her husky dogs. Yet, understood through the lens of values-based practice Antonella’s story has, I believe, wider significance at a number of levels.

First, Antonella’s story is significant for our understanding of the role of values – of what is important or matters to the individual concerned – in the presentation and treatment of eating disorders , and, by extension, of perhaps many other forms of mental distress and disorder. Specifically, her story provides at least one clear ‘proof of principle’ example supporting the role of cultural values.

As noted in my introduction, much attention has been given in the literature to the correlations between the uneven geographical distribution of eating disorders and cultural values. Correlations are of course no proof of causation. But in Antonella’s story at least the role of cultural values seems clearly evident. They were key to understanding her presenting problems. And this understanding in turn proved to be key to the cultural family therapy [ 12 ] through which these problems were, at least to the extent of her presenting eating disorder, resolved.

The cultural values involved, it is true, were not those of fashionable slimness so widely discussed in the literature. But this takes us to a second level at which Antonella’s story has wider significance. For it shows that to the extent that cultural values are important in eating disorders , their importance plays out at the level of individually unique persons. In this sense, social stresses and cultural values are played out in the body of the individual suffering with an eating disorder, making her body the ‘final frontier’ of psychiatric phenomenology [ 13 ]. Yes, there are no doubt valid cultural generalisations to be made about eating disorders and mental disorders of other kinds. And yes, these generalisations no doubt include generalisations about cultural values—about things that matter or are important to this or that group of people as a whole. Yet, this does not mean that we can ignore the values of the particular individual concerned. It has been truly said in values-based practice that as to their values, everyone is an ‘ n of 1’ [ 14 ]. Antonella, then, in the very idiosyncrasies of her story, reminds us of the idiosyncrasies of the stories of each and every one of us, whatever the culture or cultures to which we belong.

Antonella’s identification with animals , furthermore, to come to yet another level at which her story has wider significance, was a strongly positive factor in her recovery. As with other areas of mental health, it is with the negative impact of cultural values that the literature has been largely concerned: the pathogenetic influences of cultural values of slimness being a case in point in respect of eating disorders . Antonella’s story illustrates what has been clear for some time in the ‘recovery movement’, that positive values are often the very key to recovery. Not only that, but as Antonella’s passion for her husky dogs illustrates, the particular positive values concerned may, and importantly often are, individually unique.

Not, it is worth adding finally, that Antonella’s values were in this respect entirely unprecedented. Animals , after all, are widely valued, positively and negatively, and for many different reasons, in many cultures [ 11 ]. Their healing powers are indeed acknowledged. Just how far these powers depend on the kind of cross-species identification shown by Antonella, remains a matter for speculation. But, again, her story even in this respect is far from unique. Elsewhere, I have described the story of a white boy with what has become known as the ‘Grey Owl Syndrome’ , wishing to be native [ 12 , chapter 5 ]. Similarly, in Bear , Canadian novelist Marion Engel [ 15 ] portrays Lou, a woman who lives in the wilderness and befriends a bear. Lou seeks her identity from him: ‘Bear, make me comfortable in the world at last. Give me your skin’ [ 15 , p. 106]. After some time with the bear, the woman changes: ‘What had passed to her from him she did not know…. She felt not that she was at last human, but that she was at last clean’ [ 15 , p. 137]. It was perhaps to some similarly partial resolution that Antonella came.

4 Conclusions

Antonella’s story as set out above goes to the heart of the importance of cultural values in mental health. Her presenting eating disorder develops when, displaced from her culture of origin in Italy, and in effect rejected by her birth family, she finds healing only through cross-species identification with the wildness of husky dogs in her adoptive country of Canada. Although somewhat unusual in its specifics, her story illustrates the importance of cultural values at a number of levels in the presentation and management of eating and other forms of mental distress disorder.

And Antonella? I met her again in a gallery in Ottawa, rummaging through old prints. She was asking about prints of dogs; I was looking for old prints of Brazil where my father had made a second life. How was she, I asked? ‘Well …,’ she said hesitantly. Was that a healthy ‘well’ or the start of an explanation? ‘Me and Rick are splitting up,’ she said without ceremony, ‘but I still have the huskies.’ For each of us, the prints represented another world of connections.

Makino M, Tsuboi K, Denerson L. Prevalence of eating disorders: a comparison of Western and non-Western countries. MedGenMed. 2004;6(3):49. Published online 2004 Sep 27 at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed .

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Erskine HE, Whiteford HA, Pike KM. The global burden of eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2016;29(6):346–53.

Article Google Scholar

Selvini Palazzoli M. Anorexia nervosa: a syndrome of the affluent society. Transcult Psychiatr Res Rev. 1985;22( 3 ):199–205.

Google Scholar

Di Nicola VF. Overview: anorexia multiforme: self-starvation in historical and cultural context. I: self-starvation as a historical chameleon. Transcult Psychiatr Res Rev. 1990;27(3):165–96.

Di Nicola VF. Overview: anorexia multiforme: self-starvation in historical and cultural context. II: anorexia nervosa as a culture-reactive syndrome. Transcult Psychiatr Res Rev. 1990;27(4):245–86.

Andolfi M, Angelo C, de Nichilo M. The myth of atlas: families and the therapeutic story. Edited & translated by Di Nicola VF. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 1989.

Douglas M. Humans speak. Ch 11. In: Implicit meanings: essays in anthropology. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; 1975. p. 173–80.

Crystal D. The Cambridge encyclopedia of language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1987.

Parry A, Doan RE. Story re-visions: narrative therapy in the postmodern world. New York: Guilford Press; 1995.

Atwood M. Strange things: the malevolent north in Canadian literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1995.

Atwood M. Life before man: a novel. New York: Anchor Books; 1998.

Di Nicola VF. A stranger in the family: culture, families, and therapy. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.; 1997.

Nasser M, Di Nicola V. Changing bodies, changing cultures: an intercultural dialogue on the body as the final frontier. Ch 9. In: Nasser M, Katzman MA, Gordon RA, editors. Eating disorders and cultures in transition. East Sussex: Brunner-Routledge; 2001. p. 171–93.

Fulford KWM, Peile E, Carroll H. A smoking enigma: getting and not getting the knowledge. Ch 6. In: Fulford KWM, Peile E, Carroll H, editors. Essential values-based practice: clinical stories linking science with people. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2012. p. 65–82.

Chapter Google Scholar

Engel M. Bear: a novel. Toronto: Emblem (Penguin Random House Books); 2009.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The story of Antonella was first published in reference [ 12 ] (pp. 214–220) and presented at the Advanced Studies Seminar of the Collaborating Centre for Values-based Practice in Health and Social Care at St Catherine’s College, Oxford in October 2019. The names and other details of the case have been altered to maintain confidentiality. Parts of the discussion are adapted from that publication and the Oxford seminar. I am grateful to the publishers for permission to reproduce these materials here and to Professor Fulford and the members of the Advanced Studies Seminar for their stimulating exchanges. The subheading to the discussion of Antonella’s story (‘Life before Man’) was inspired by Margaret Atwood’s novel, Life Before Man [ 11 ].

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Canadian Association of Social Psychiatry (CASP), World Association of Social Psychiatry (WASP), Department of Psychiatry and Addictions, University of Montreal, Montreal, QC, Canada

Vincenzo Di Nicola

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, The George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Vincenzo Di Nicola .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Medical University Plovdiv, Plovdiv, Bulgaria

Drozdstoy Stoyanov

St Catherine’s College, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Bill Fulford

Department of Psychological, Health & Territorial Sciences, “G. D’Annunzio” University, Chieti Scalo, Italy

Giovanni Stanghellini

Centre for Ethics and Philosophy of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

Werdie Van Staden

Department of Psychiatry, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

Michael TH Wong

Guide to Further Sources

For a more extended treatment of the role of culture in eating disorders and family therapy see:

Di Nicola VF (1990a) Overview: Anorexia multiforme: Self-starvation in historical and cultural context. I: Self-starvation as a historical chameleon. Transcultural Psychiatric Research Review, 27(3): 165–196.

Di Nicola VF (1990b) Overview: Anorexia multiforme: Self-starvation in historical and cultural context. II: Anorexia nervosa as a culture-reactive syndrome. Transcultural Psychiatric Research Review, 27(4): 245–286.

Di Nicola, V (1997) A Stranger in the Family: Culture, Families, and Therapy . New York & London: W.W. Norton & Co.

Nasser M and Di Nicola, V. (2001) Changing bodies, changing cultures: An intercultural dialogue on the body as the final frontier. In: Nasser M, Katzman M A, and Gordon R A, eds. Eating Disorders and Cultures in Transition . East Sussex, UK: Brunner-Routledge, pp. 171–193.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Di Nicola, V. (2021). Antonella: ‘A Stranger in the Family’—A Case Study of Eating Disorders Across Cultures. In: Stoyanov, D., Fulford, B., Stanghellini, G., Van Staden, W., Wong, M.T. (eds) International Perspectives in Values-Based Mental Health Practice. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47852-0_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47852-0_3

Published : 12 December 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-47851-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-47852-0

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Search by category

Popular searches.

Eating disorder case study

Contact us to make an enquiry or for more information

- Telemedicine

- Healthcare Professionals

- Go to MyChart

- Find a Doctor

- Make an Appointment

- Cancel an Appointment

- Find a Location

- Visit ED or Urgent Care

- Get Driving Directions

- Refill a Prescription

- Contact Children's

- Pay My Bill

- Estimate My Cost

- Apply for Financial Assistance

- Request My Medical Records

- Find Patient Education

- Refer and Manage a Patient

Treatment for Eating Disorders: A Q&A and Case Study by Robyn Evans, ARNP

March 2, 2022

Robyn Evans, ARNP, is the lead nurse practitioner for Seattle Children’s Eating Disorders Clinic . She attended Yale University School of Nursing and has been at Seattle Children’s since 2013.

Q: What changes has Seattle Children’s seen during the pandemic in eating disorder referrals?

Referrals for eating disorders have grown fourfold at Seattle Children’s in the last two years. The increase in number and severity of eating disordered patients began during the pandemic’s first summer (2020) and continues to this day. This comports with what has been reported in the medical literature over the last two years. Studies from the University of Michigan and Boston Children’s Hospital all published similar results demonstrating at least a doubling in the numbers of patients seeking care for treatment of eating disorders.

Otto, AK, Jary JM, Sturza J et al. Medical Admissions Among Adolescents with Eating Disorders During Covid-19 Pandemic. Pediatrics. 2021; 148(4).

Lin, J, Hartman-Munick, S et al. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Number of Adolescent / Young Adults Seeking Eating Disorder-Related Care. Journal of Adolescent Health. 69 (2021); 660 – 663.

Q: How is the Eating Disorders Clinic keeping up with the high demand for services?

We have adapted our care model at Seattle Children’s to stretch resources to more patients. Beginning January 1, 2022, all patients referred to Eating Disorders with a complete referral are being offered a one-time telehealth visit with the option to join a waitlist for ongoing care based on fit of services and family interest. A complete referral must be submitted before we schedule a visit:

- New Appointment Request Form ( PDF ) ( DOC )

- Orthostatic vital signs with resting heart rate – within the last 14 days

- Weight and height – within the last 14 days

- Growth charts

- Labs (CBC, ALT, T4, TSH, electrolytes, BUN/creatinine, calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, sed rate) – within the last 30 days

- EKG within the last 30 days

By transitioning to time-limited care models, our goal is to reach more families in the communities we serve.

Q: Does the telehealth visit include the patient and parent(s)?

Yes, both the patient and parent(s) attend the telemed consult. The patient may meet confidentially with the provider for a portion of the visit.

Q: How does the one-time telehealth visit work?

Once a complete referral is received, patients and families are scheduled for a 60-minute telemedicine consultation with a physician or advanced practice provider/ARNP who will discuss family and patient concerns, eating disorder symptoms and behaviors and will review supporting documentation that was provided in the referral. The family will receive an initial assessment including diagnosis, recommended treatment plan and community resources to help support their teen. These will also be forwarded to the primary care provider after the visit.

The adolescent medicine provider will coordinate with our social work team to provide additional resources such as school accommodations, supervised school lunches and parental supports such as employment accommodations (i.e., FMLA) and caregiver educational supports such as Seattle Children’s caregiver meal support class. Resources are also provided to help families find dietitians and therapists with eating disorder treatment experience.

Q: Do families meet with a social worker?

We’ve made some recent changes to the social work portion of the visit. Instead of scheduling a separate visit between the social worker and patient/family, our social work team primarily uses MyChart messaging to provide families with written resources.

Q: What is the biggest obstacle to a patient being seen quickly?

We would really like to emphasize we are unable to offer consultation for incomplete referrals that do not include required supporting clinical documentation (as listed on the Eating Disorders’ Refer a Patient page and in the bullets above).

Seattle Children’s Eating Disorders Website – Referral information and instructions

“ Eating Disorders in Children Increased During the Pandemic ,” Verywell Mind, Feb. 22, 2002, featuring Dr. Yolanda Evans, clinical director of Seattle Children’s Adolescent Medicine.

Condition-specific resources

- Eating Disorders: A Guide for Parents and Caregivers (PDF) ( Russian ) ( Spanish )

- Eating Disorders Booklist and Resources (PDF)

- Restoring Nutrition: What to Expect During Your Child’s Hospital Stay ( Spanish ) (PDF) (useful if the family is being sent to the Emergency Department for admission)

Treatment-specific resources

- Choosing a Mental Health Provider (PDF) ( Spanish )

- How to Find a Therapist (PDF) ( Spanish )

- Meal Support Training for Parents (PDF) ( Spanish )

- Outpatient Eating Disorders Program (PDF) (how our program works)

- Outpatient Nutrition Counseling for Adolescents (PDF) ( Spanish )

- Eating Disorder Treatment Facilities (PDF) (for-profit facilities in the Western United States)

Outside facilities with expertise in the management of eating disorders

- The Emily Program

- Center for Discovery

- Eating Recovery Center

- The Evidence Based Treatment Centers of Seattle

- Opal (for patients over age 18 years)

- Thira Health (offering services for mood disorders)

- Sunrise Nutrition

- Mind/Body Nutrition

- The Veritas Collaborative

- Roger’s Memorial

- Virtual Eating Disorder Treatment | Equip Health

External Links

- Adolescent Nutrition (University of Washington Maternal Child Health Program)

- National Association for Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Eating Disorders

- National Eating Disorders Association

Case Study: Eating Disorder in a 15-Year-Old Female

Author: Robyn Evans, ARNP , Clinical Lead for Outpatient Eating Disorder Care at Seattle Children’s

Date: March 2022

Summary : A 15-year-old female with an eating disorder is referred to Seattle Children’s. After evaluation, the patient and her family receive education, social work consultation, care instructions and safety planning to support them while they wait for an opening in the eating disorders outpatient treatment program at Seattle Children’s or elsewhere.

Patient History: The patient is a 15-year-old female with 15 months of weight loss. She is referred for telemedicine evaluation for an eating disorder due to accelerating rate of weight loss. She reports food restriction and food group elimination (carbohydrates) in the setting of increased levels of physical activity after she transitioned to online school at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The patient experienced menarche at the age of 14 years and had approximately six consecutive monthly menses until they ceased 12 months ago.

Total weight loss is now approximately 20% of prior body weight.

Labs show increased CO 2 , low white blood cell count and iron deficiency anemia. EKG is normal except for bradycardia.

The review of systems is positive for the following: fatigue, dizziness with standing, generalized abdominal pain (worse after meals), constipation, amenorrhea, cold intolerance and hair loss.

The physical exam includes vital signs collected by the PCP two weeks ago (HR of 49 bpm with orthostatic tachycardia). During the telemedicine visit the patient is withdrawn and irritable.

Current nutritional intake includes two meals a day of two servings and one snack a day of one serving. Beverages are water only. The patient demonstrates extreme rigidity when discussing nutrition choices, sharing that she feels her food choices are “very healthy” and she will not consider making dietary changes due to fear of weight gain.

She reports an increasing number of minutes of physical activity a day, which includes getting up early in the morning to do YouTube exercise videos and running for up to an hour after school each day.

The patient earns a 4.0 GPA at school. Parents report homework is now taking significantly more time to complete as compared to before onset of weight loss. They also observe their daughter isolating herself in her room. Her social media interests revolve around nutrition and exercise. Parents observe she downloads activity and calorie tracker apps onto her phone.

Parents tried to encourage their daughter to eat more and exercise less. They are unable to provide adequate support when she becomes emotionally upset. They feel the only way their daughter can manage low mood is through exercise.

During her confidential interview the patient shares that she is struggling with passive suicidal ideation and that her only reason to live is to participate in track this spring. The teen reports no history of gender identity concerns or sexual activity. She denies all substance use.

Patient Diagnosis: The patient’s symptoms support a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa.

Treatment/Discussion: Eating disorders are mental health diagnoses with physiologic consequences, which can be fatal.

Best outcomes for adolescents with eating disorders are seen when patients have a multidisciplinary team consisting of a therapist, medical provider and dietitian. The therapist aids in management of the intrusive eating disorder thoughts. Dietitians support parents and teens in implementing adequate nutrition at home on a schedule that promotes recovery from malnutrition.

Given her bradycardia, the patient is advised to follow up with her primary care provider weekly to assess for need for hospitalization if her heart rate decreases to less than 45 bpm per the Seattle Children’s Refeeding Guidelines (see link in references below). Reasons to go to the Emergency Department are reviewed with the family. The PCP is recommended to order a DEXA bone scan to further evaluate for low bone density due to prolonged amenorrhea.

The family is counseled that an eating disorder is a mental health diagnosis with significant medical consequences. The importance of establishing care with a therapist and dietitian is emphasized. Social work is consulted to offer parents support in building their daughter’s treatment team. Education is provided on the effects of prolonged starvation on adolescent growth and development. Strict guidelines regarding the importance of physical rest and abstaining from all exercise are discussed.

Safety planning was completed alone with the teen and shared with her parents along with resources including the Crisis Text Line.

Reassurance was provided that abdominal symptoms will likely resolve with increased nutritional intake.

Parents are referred to Meal Support class (available twice weekly on Zoom at Seattle Children’s) to learn more about effective feeding strategies at home. The patient is offered a spot on the waitlist to receive 12 weeks of in-person medical monitoring in the Outpatient Eating Disorder Program (OPED). Community providers are welcome to request reevaluation via telemedicine in the 90 days after the initial evaluation.

References:

- Seattle Children’s Eating Disorder Website (Includes information on Referral Guidelines):

- Eating Disorders Clinic – Seattle Children’s

- Academy of Eating Disorders. Eating Disorders: A Guide to Medical Care. 2021. Publications – Academy for Eating Disorders (aedweb.org)

- Safe Exercise at Every Stage Guidelines. 2021. SEES (safeexerciseateverystage.com)

Subscribe to Provider News

Monthly news about Seattle Children's programs, services, policies and people delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe Now

Access Dashboard

You can find information about current wait times in our specialty clinics using our Access Dashboard, updated monthly.

Healthcare Provider Resources

- Refer a Patient

- Algorithms for PCPs

- Educational Programs and Resources

Seattle Children’s complies with applicable federal and other civil rights laws and does not discriminate, exclude people or treat them differently based on race, color, religion (creed), sex, gender identity or expression, sexual orientation, national origin (ancestry), age, disability, or any other status protected by applicable federal, state or local law. Financial assistance for medically necessary services is based on family income and hospital resources and is provided to children under age 21 whose primary residence is in Washington, Alaska, Montana or Idaho.

By clicking “Accept All Cookies,” you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage and assist in marketing efforts. For more information, see Website Privacy .

- Open access

- Published: 14 November 2023

Experiences of living with binge eating disorder and facilitators of recovery processes: a qualitative study

- Marit Fjerdingren Bremer 1 ,

- Lisa Garnweidner-Holme 2 ,

- Linda Nesse 1 , 3 &

- Marianne Molin 2 , 4

Journal of Eating Disorders volume 11 , Article number: 201 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1455 Accesses

Metrics details

Binge eating disorder (BED) is the most prevalent eating disorder worldwide. BED is often associated with low quality of life and mental health problems. Given the complexity of the disorder, recovery may be challenging. Since BED was only recently specified as a diagnostic category by the World Health Organization (2021), little is known about how patients experience living with BED in everyday life. This study aimed to explore how patients experience living with BED and to investigate factors perceived as facilitating recovery.

Individual interviews were conducted with six patients in a rehabilitation programme for recovery from BED. Interviews were conducted digitally and verbally transcribed between December 2020 and January 2021. The analysis was based on Malterud’s systematic text condensation.

Being diagnosed with BED could be experienced as a relief. The participants perceived living with BED as a challenging addiction. They struggled with a low self-image and experienced a lack of understanding from others, resulting in shame. Self-compassion and social support from friends and family and through participation in a rehabilitation programme were important facilitators of recovery.

Participants perceived living with BED as a challenging addiction. They struggled with low self-esteem and experienced a lack of understanding from others, resulting in shame. Being diagnosed with BED was perceived as a relief. They appreciated that issues related to mental health were addressed during rehabilitation to better understand the complexity of BED. Knowledge about BED, as well as the difficulties of living with BED among family members and friends might help patients with BED feel less ashamed of their disorder and could thus contribute to increased self-compassion.

Plain English summary

We interviewed six patients with binge eating disorder (BED) about their experiences living with BED, which is the most prevalent eating disorder worldwide. However, difficulties diagnosing patients with BED and a lack of knowledge about BED among healthcare professionals make it challenging to provide patients with appropriate help to recover from BED. The participants in our study participated in a rehabilitation programme for BED. They experienced living with BED as a challenging addiction. Low self-image and others’ lack of understanding made the individuals ashamed of their eating disorders. Self-compassion and social support through taking part in the rehabilitation programme were important facilitators of recovery. This study indicates that more knowledge about BED among family members, friends and healthcare professionals and social support are notable facilitators for recovering from BED.

Article Highlights

Even though BED is the most prevalent eating disorder, we have limited knowledge about how patients experience living with BED and their recovery processes

Patients with BED described the disorder as a challenging addiction

Low self-image and lack of understanding by others made the participants ashamed of their disordered eating behaviours

Self-compassion and social support were perceived as core facilitators of recovery

The key characteristics of binge eating disorder (BED) are the tendency to engage in binge eating episodes during which excessive amounts of food are consumed in a short period of time, paired with a subjective sense of loss of control [ 1 ]. BED was first recognised as a diagnostic category in the fifth version of the American Diagnostic and Statistical Model of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 2013 [ 2 ]. In the European System’s International Classification of Diseases, BED was first specified in 2018 [ 3 ]. The lifetime prevalence of BED is estimated to between 1.5 and 1.9%, making it the most prevalent of the eating disorders [ 4 , 5 ]. Although BED is considered the most common eating disorder, it can be argued to be the eating disorder that receives the least attention in mental health care. Several models of environmental factors contributing to BED have been proposed [ 6 ]. These for instance include media exposure, thin-ideal internalisation, and personality traits such as negative emotionality [ 6 ]. People with overweight or obesity appear to be at particular risk of developing BED although the directionality in the relationship between overweight, obesity and BED is complex and unclear [ 7 ].

Recovery from eating disorders is a non-linear process that includes psychological and social changes, including experiences of empowerment, relationships with others, as well as improvements in body image and reductions in disordered eating patterns [ 8 ]. Given the complexity of BED, recovery can be a challenging process [ 9 ]. Recovery rates, on average, remain below 50% and largely depend on how recovery is defined [ 10 ]. Recovery from BED may be understood and defined differently by patients and health professionals [ 10 ].

There is an increasing awareness of BED in the research literature on eating disorders, with several studies exploring patients’ positive and negative experiences of participation in treatment and rehabilitation [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. However, there appears to be fewer studies on patients’ experiences of living with BED in everyday life [ 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]. In qualitative studies, patients have described living with BED as characterized by experiences of guilt and shame, as well as a loss of control [ 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]. However, accepting the disorder and being validated by others have been described as important steps in the recovery process [ 17 ]. Furthermore, psychotherapy and person-centred treatment may facilitate recovery [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Although some studies have investigated patients’ experiences with recovery from BED [ 8 , 17 , 20 , 21 ], we have limited in-depth knowledge on facilitators of recovery. Knowledge about how patients experience living with and recovering from BED may be important for better informing our understanding of the influence of BED on everyday life and for tailoring treatment to best promote recovery [ 22 ]. This study explores how persons with BED experience living with this eating disorder and investigates factors that were perceived as facilitating recovery.

Design and data collection

Semi-structured individual interviews were conducted by MFB between December 2020 and January 2021. MFB holds a master’s degree in public health science and a bachelor’s degree in public nutrition. MFB currently works at a rehabilitation centre as a nutritionist with patients with obesity. The individuals in this study were recruited from another rehabilitation centre and MFB did not have former knowledge to the participants. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the interviews took place online using a digital platform called Visiba Care (visibacare.com), an application or web interface that offers secure communication through video. The interview guide (Additional file 1 ) was developed by MFB, LN and MM. LN is a clinical psychologist with a PhD in public health science who works in addiction research. MM holds a PhD in nutrition and is a professor in public health and public health nutrition. The themes in the interview guide were developed inductively guided by the research questions of the investigators. The interview guide was pilot tested with a patient with BED. The pilot interview did not change the interview guide. Hence, the pilot interview was included in the sample and analysis of this article. 11 participants attending the rehabilitation programme were invited to participate in the study. 6 agreed to participate. We did not include more participants because we reached information power [ 23 ], due to these 6 informants provided very relevant information for the actual research questions in the study. Before participation, the interviewees gave their written informed consent. Recruitment continued until we reached informational power related to the richness of the data [ 23 ]. Interviews were audio-recorded with a Dictaphone application [ 24 ] and lasted 45–60 min. The interviews were transcribed verbatim by MFB. All the authors read the transcribed interviews. The study was conducted in accordance with COREQ guidelines [ 25 ].

Participants and setting

The participants were all women between 30 and 70 years old. In Norway, persons who have a Body Mass Index (BMI) > 40 without comorbidities or a BMI > 35 with comorbidities qualify for treatment at rehabilitation centres [ 26 ]. In some of these centres, patients are screened for eating disorders to identify the potential coexistence of BED. Participants in this study were in treatment for obesity at one of these rehabilitation centres. Based on screening procedures after entering rehabilitation, patients who experienced co-occurring challenges with binge eating were offered participation in a rehabilitation programme focusing on coping with and recovering from BED. The screening process consisted of six questionnaires and a consultation with a psychologist. A clinical assessment was made of whether the person met BED criteria. The questionnaires explored the patients’ eating behaviours and thoughts and feelings related to food. Two questionnaires mapped the patients’ mental health, including anxiety and depressive symptoms.

As part of the rehabilitation programme, sessions were held once a week over three months. The programme involved individual and group-based sessions, with 10 participants, about behaviour change, physical activity, diet, mental health, motivation and empowerment. The group-based sessions were led by a specialist in clinical psychology and a clinical nutritionist. The group-based sessions focused on challenges with binge eating, and important parts of the group discussions were self-esteem, causes and triggers of binging, knowledge of physiological mechanisms, understanding of thoughts and emotions’ influence on behaviours, and further work on recovery. Respondents were given fictive names in the presentation of the results to secure their privacy.

The analysis was conducted by MFB and was guided by Malterud’s systematic text condensation [ 27 ], a descriptive and explorative method inspired by phenomenology. LGH, LN and MM assisted with the analysis. The analysis involved the following steps: (1) reading all the transcribed interviews to obtain an overall impression and rereading them with a focus on the study’s aim; (2) identifying and sorting meaning units representing aspects of participants’ lived experiences with BED and perceived facilitators for recovery and coding; (3) condensing the contents and meanings of each coded group and (4) synthesising the contents of each code group to generalise descriptions and concepts. The process to formulate meaning units and the subsequent coding of the content and meaning involved discussion and clearance of the text. The main focus was to discuss understanding of the text, compare main impressions and themes, which again could provide an overview of similarities and differences. We highlighted recurring citations and citations that gave information on equal topics.

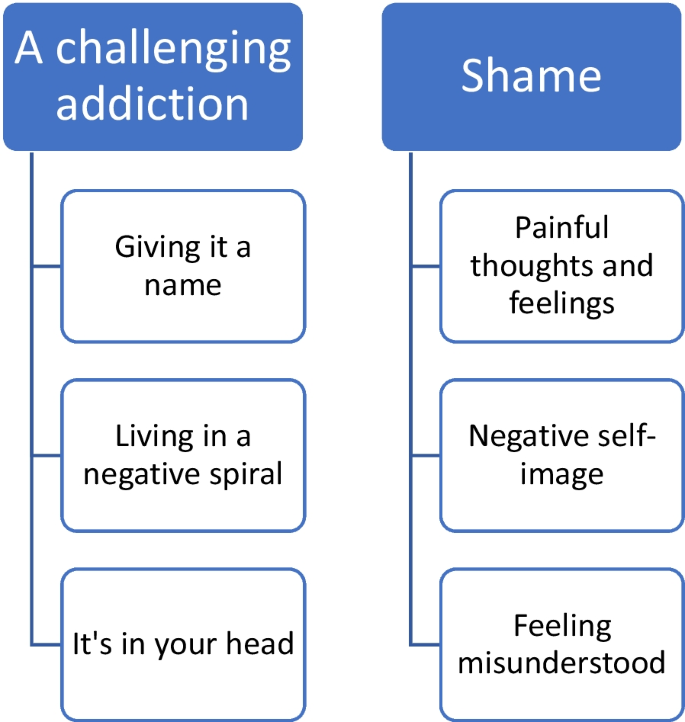

We identified the following two main themes related to patients’ experiences with BED (Fig. 1 ): (1) A challenging addiction with the subthemes giving it a name , living in a negative spiral and it’s in your head ; and (2) shame with the subthemes painful thoughts and feelings , negative self-image and feeling misunderstood . We found three main themes regarding the perceived facilitators of recovery: (1) recovery is a long process with the subthemes acceptance of the disorder and give yourself time ; (2) coping with the subthemes self-compassion and strategies to manage the disorder ; (3) community with the subthemes group affiliation and social support .

Main themes and subthemes concerning the experience of living with BED

Experiences of living with BED

The participants described living with BED as a challenging addiction . Berit explained how difficult it was to stop eating: ‘When I eat, I get happy right there and then, but when I think about it, and the dopamine or whatever it is stops working, I feel completely unsuccessful, and then I think that I can just give up. It is over. I just continue to eat. … I can’t do anything right anyway’.

Giving it a name describes participants’ experienced relief of being diagnosed with BED. The participants experienced BED as a complex condition and a challenging disorder that removed their focus from other notable areas of life. They often told stories of repeated feelings of failure in their management of BED. They felt too embarrassed to tell anyone in their lives about their diagnoses and, thus, kept it a secret, even though they thought their family members already probably knew. Their frustration with not being able to control their eating was described as confusing and time consuming. They felt hopeless and stupid. However, being diagnosed with BED was often described as a relief, which Nora expressed:

‘It’s actually been really nice. (...) I was referred because of my overweight, uhh, and based on mapping and such, I was diagnosed with binge eating disorder. And I was about to say, uhh, that I wasn’t completely surprised. I’ve realised in a way that there has been a problem, uhh, but at the same time, it was kind of good to have it confirmed (...)’.

All participants were diagnosed with BED at the rehabilitation centre.

The participants described living with BED as a negative spiral that was difficult to escape and characterised by periods of guilt when they could not control their eating habits. Tuva explained, ‘Yes, it’s like I don’t use my head. I don’t do what I’m supposed to, ehh, and I don’t enjoy it. I sit and eat with a guilty conscience’. Conversely, the participants stated that binging gave them good feelings and satisfaction. These binge eating episodes were considered a reward or a strategy to escape stressful experiences in daily life.

Dealing with binge eating was often viewed in the context of how they otherwise felt in life. A negative spiral was also mentioned concerning weight management experiences. Individuals had experiences in which they lost weight but had trouble maintaining weight loss. This led to dissatisfaction and hopelessness and resulted in episodes of increased binge eating. Some participants had lived with BED for a long time and had experienced BED as a permanent part of them.

Participants experienced BED as something that is in your head , as Pia expressed: ‘At least it starts there, that the body is a symptom of what’s in the head. I think that about my suffering, that the physical kind of reflects the mental’. It was vital for participants to understand the connection between physical and mental challenges and how these affect each other. Negative thoughts and feelings often led to binge eating episodes, and subjects appreciated the focus on mental health in the rehabilitation centre to learn strategies to cope and choose differently.

All participants associated BED with shame , as illustrated by Berit’s statement:

‘It is very taboo, very taboo. I try to hide it from everyone. When we’re with others, I don’t eat more than others, but when I’m at home and no one sees me, that’s when I eat. So, it’s tiring, and you always watch out. You never feel well enough, and uhh yeah, it really hurts’. Shame was often described as painful feelings and negative thoughts . The participants often felt ashamed when other people asked them, ‘Why can’t you just stop eating?’ This question made them feel ashamed of not being in control of their eating behaviours. In this context, the respondents explained that most binge eating episodes occurred when they were alone to avoid feelings of shame. The participants had many negative thoughts and spent much time ruminating about what others thought about them. Thus, shame often related to subjects’ negative self-image , as this comment by Pia illustrated: ‘That’s kind of what the body ideals are today, thin and slim, and if you don’t fit in that category, there’s something wrong with you’.

Several participants described having a negative self-image and critical thoughts about their bodies and behaviours. They mentioned that they already had negative self-images before developing obesity and being diagnosed with BED. Obesity was considered challenging in terms of physical limitations and mental health struggles. They described feelings of not fitting into the bodily ideals in today’s society, where thinness and health are expected.

Living with shame was also connected to a feeling of being misunderstood by family members, friends or even health professionals. Berit stated: ‘I had a doctor who said, “You just have to pull yourself together. You just have to eat right”. I think there are probably a lot of doctors who don’t have knowledge about binge eating’.

Participants experienced little openness about BED. They expressed that they feel it is more common to talk and hear about anorexia and bulimia. Having a less-known eating disorder makes it harder to be open and honest. Some kept the disorder a secret from family and friends, which again worsened their shame and hopelessness.

Facilitators of recovery processes

Recovery from BED was often considered a long process involving accepting the disorder and giving oneself time . Participants defined ‘recovery’ as the process of reducing binge eating and enhancing coping. Being healthy did not imply the total absence of binge eating episodes, but having greater control over the occurrence and amount of food consumed during binge eating episodes, as Kari explained: ‘It is about coping with it so that it does not happen so often and regularly, but to accept that it can happen once in a while and that it is normal and that you should not feel that you have failed. Because I think that when it happens once, seldom, that I have succeeded in recovering’. The participants did not perceive recovery from BED as being healthy, since they often had other diseases that they had to handle, such as diabetes.

They perceived it as important to have strategies to manage recovery, as Pia described: ‘ I think that you have to work on it continuously. But I see a change because I have gotten some tools that I can use in such situations, and I have another mindset now. I feel more relaxed’.

Managing to cope with recurring binge eating episodes was considered an important facilitator of recovery. Participants associated coping with exerting control over their eating behaviours. Many subjects felt more in control with others but felt they could lose it when they were alone, as Silje explained: ‘It’s kind of like how you compare yourself to others and how they manage to control their eating, uhh, and that's what I want, too’.

The participants often managed to have control by avoiding access to foods that triggered BED (e.g. sweets). Nora said, ‘I have the knowledge to choose the food that’s right for me, and I need to have it available’ . Furthermore, they related coping to ‘inner factors’ that influence their health and quality of life. For instance, focusing on health aspects was considered more important than focusing on weight. Health aspects were also an important motivation for recovery. Several participants explained that pain due to being overweight, such as knee arthrosis, motivated them to control their BED.

In addition, self-compassion was often mentioned as a significant facilitator of recovery. Participants gave themselves credit and bragged about periods without binge eating as positively self-reinforcing, often disrupting their negative spirals. Pia explained, ‘Self-compassion is very important for me, hm, being good with myself, being my own best friend and to think about what is good for me. Like, ‘Are episodes with binge eating good for me? No, they are not. It is better for me to go for a walk or to eat fruit’. However, the participants said that self-compassion requires awareness and practice. They highlighted getting older, gaining life experience and being more mature and reflective as factors that made it easier to give oneself acceptance.

‘Time outs’ from eating were reported as an important strategy to manage the disorder . The patients stated that breaks gave them time to reflect on why they were eating, as Berit explained: ‘It has also helped me to wait for 15 min and to eat what you like. Take a 15-min break to see if I really want to eat. Very often, you actually don’t want to. I may start to eat, but then I am at least more aware of eating.’ Another participant stated that it was important not to be too strict with oneself and not to have overly strict rules, such as ‘yes food’ and ‘no food’, to cope with BED. Good eating routines were another factor that facilitated recovery. Outdoor activities, listening to music, reading books, knitting and talking to oneself often helped interviewees to avoid new BED episodes. They appreciated that the present rehabilitation programme focused on mental health, well-being and personal relationships with food. Learning about BED gave them a better understanding that obesity did not just result from a lack of self-control and willpower.

One of the most significant facilitators for managing recovery was a community characterised by group affiliation and social support . All outlined the importance of the community at the rehabilitation centre, as Pia described: ‘It was very good to meet others in the same situation and to get validation that there are more people in the same situation and that you can talk to them openly about these episodes without being judged’.

Some participants feared how they would cope with BED once they no longer belonged to a rehabilitation programme. The perceived social support of others in the group gave them safety. Nora explained, ‘It was very good to not feel alone (…) to hear that others have the same problems. This made it easier to share my experiences. Being together with others in the same situation makes me feel safe’. The subjects learned to share BED-related experiences and feelings in the group. For recovery, they also considered it important to learn to share their feelings with others outside the programme, as Nora said: ‘I have been better about talking about my feelings at home, for example “Now I am alone, and I am sad because you are not here”’.

The participants in this study perceived living with BED as a challenging addiction. Being diagnosed with BED could be a relief; however, a negative self-image and experiencing a lack of understanding from others made the participants ashamed of their disorder. The participants experienced limited openness about BED and mental disorders in their social surroundings. Even though participants were still living with BED, perceived facilitators of recovery were self-compassion and social support received during rehabilitation.

In a study comparing how obese women with and without BED experienced binge eating [ 28 ], the authors found that women experienced BED as a form of addiction. In this context, the participants in our study experienced living with BED as characterised by negative thoughts and feelings. A review of research on emotion regulation in BED found that negative emotions play an important role in the onset and maintenance of binge eating [ 29 ]. Likewise, the participants in our study perceived living with BED as a rollercoaster ride of emotions, where the distance between positive and negative feelings was short. Experiences of living with BED as a negative spiral was also described in another study of patients with BED in the US [ 14 ].

The participants in our study often experienced living with BED as characterized by the shame of not having control over their eating habits and weight. Negative comments from family members or friends about their eating habits or obesity exacerbated shame. The participants also related shame to feeling misunderstood by family members, friends or even health professionals. This finding corroborates studies that found that patients with BED often felt misunderstood by health professionals [ 8 ]. There are indications that health professionals have limited knowledge of BED. A cross-sectional study in the US identified low awareness of and knowledge about BED among health professionals.

Shame of not having control was identified as hindering recovery in other studies [ 17 , 29 , 30 ]. For instance, a qualitative study investigating using online messages in a rehabilitation programme for BED found that self-blame promoted a feedback cycle of binging, which was perceived as barrier for recovery [ 17 ]. As mentioned in the background, some studies have investigated patients’ experiences with recovery from BED [ 8 , 17 , 20 , 21 ]. Our participants experienced recovery as a long process that mainly concerned coping. Interestingly, recovery did not imply being fully recovered from binge eating episodes but rather control over the disorder. We found that self-compassion and social support within a rehabilitation programme were the most important facilitators for recovery. Self-compassion involves developing an accepting relationship with oneself, particularly in instances of perceived failure, inadequacy and personal suffering [ 31 ], while social support constitutes the availability of potential supporters, or structural support, and the perception of support, or functional support [ 32 ]. Studies have revealed promising results for compassion-focused therapy for recovery from BED [ 33 , 34 ]. Social support may play an important role in BED recovery process [ 32 , 35 , 36 ]. An Australian mixed-methods study outlined the social support in a Instagram community as important facilitator for recovery [ 37 ]. Similarly, social support was also a notable facilitator of group-based recovery for patients with BED, combining guided physical exercise and dietary therapy in a study from Norway [ 14 ]. Our participants outlined that for recovery, they considered it important to learn to share their feelings with others outside the programme.

All of our participants outlined the importance of being part in a rehabilitation programme for recovery from BED. Several studies have investigated participants’ experiences with different rehabilitation programmes for BED [ 12 , 14 , 17 , 37 ]. For instance, a qualitative study exploring participants’ experiences of a web-based programme for bulimia and BED found that interventions should be flexible, considering individual preferences [ 38 ]. The participants in our study described the value of addressing cognitive behavioural change and mental health and appreciated receiving support from an interprofessional team that collaborated in their recovery process. However, it should be acknowledged that all of the participants were overweight or obese before their diagnosis with BED. Their experiences with previous weight-loss programmes might have influenced their preferences for addressing mental health in rehabilitation. Women with BED in the US have also reported appreciating receiving weight-neutral rehabilitation programmes for BED after experiences of being blamed for their weight and health conditions [ 11 ]. Thus, rehabilitation programmes for patients with BED should be tailored towards subjectively relevant themes to facilitate recovery.

Limitations

This study was conducted in a small sample size, which is usual for qualitative research aiming to investigate participants’ experiences [ 23 ]. However, it has to be acknowledged that the findings of this study are primarily applicable to the specific setting of the study and perhaps only transferable to patients in similar situations or rehabilitation programmes. Participants were interviewed a short time after they completed the programme. Hence, their responses might have been influenced by the focus of the content in programme in regard to facilitators for recovery. In addition, interviews were conducted digitally, which might have influenced the openness of the participants [ 39 ].

Conclusion and implications for practice

The participants perceived living with BED as a challenging addiction. They struggled with low self-esteem and experienced a lack of understanding from others, resulting in shame. They appreciated that issues related to mental health were addressed during rehabilitation to better understand the complexity of BED. Knowledge about BED as well as the difficulties of living with BED among family members and friends might help patients with BED feel less ashamed of their disorder and could thus contribute to increased self-compassion.Rehabilitation programmes should address social support in order to promote recovery from BED.

Availability of data and materials

The data analysis for this manuscript can be made available upon reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- Binge eating disorder

World Health Organization

Giel KE, Bulik CM, Fernandez-Aranda F, Hay P, Keski-Rahkonen A, Schag K, et al. Binge eating disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2022;8(1):16.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5 ed. Arlington, VA, USA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). The global standard for diagnostic health information 2018. Available from: https://icd.who.int/en .

Qian J, Wu Y, Liu F, Zhu Y, Jin H, Zhang H, et al. An update on the prevalence of eating disorders in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eat Weight Disord. 2022;27(2):415–28.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Chiu WT, Deitz AC, Hudson JI, Shahly V, et al. The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(9):904–14.

Culbert KM, Racine SE, Klump KL. Research review: what we have learned about the causes of eating disorders—a synthesis of sociocultural, psychological, and biological research. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56(11):1141–64.

Davis HA, Graham AK, Wildes JE. Overview of binge eating disorder. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2020;14(12):26.

Article Google Scholar

Richmond TK, Woolverton GA, Mammel K, Ornstein RM, Spalding A, Woods ER, et al. How do you define recovery? A qualitative study of patients with eating disorders, their parents, and clinicians. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(8):1209–18.

de Vos JA, LaMarre A, Radstaak M, Bijkerk CA, Bohlmeijer ET, Westerhof GJ. Identifying fundamental criteria for eating disorder recovery: a systematic review and qualitative meta-analysis. J Eat Disord. 2017;5:34.

Bardone-Cone AM, Alvarez A, Gorlick J, Koller KA, Thompson KA, Miller AJ. Longitudinal follow-up of a comprehensive operationalization of eating disorder recovery: concurrent and predictive validity. Int J Eat Disord. 2019;52(9):1052–7.

Salvia MG, Ritholz MD, Craigen KLE, Quatromoni PA. Women’s perceptions of weight stigma and experiences of weight-neutral treatment for binge eating disorder: a qualitative study. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;56: 101811.

Rørtveit K, FurnesPh DB, DysvikPh DE, UelandPh DV. Patients’ experience of attending a binge eating group program—qualitative evaluation of a pilot study. SAGE Open Nurs. 2021;7:23779608211026504.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Moghimi E, Davis C, Bonder R, Knyahnytska Y, Quilty L. Exploring women’s experiences of treatment for binge eating disorder: Methylphenidate vs cognitive behavioural therapy. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2022;114:110492.

Bakland M, Rosenvinge JH, Wynn R, Sundgot-Borgen J, FostervoldMathisen T, Liabo K, et al. Patients’ views on a new treatment for Bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder combining physical exercise and dietary therapy (the PED-t). A qualitative study. Eat Disord. 2019;27(6):503–20.

Perelman H, Gilbert K, Grilo CM, Lydecker JA. Loss of control in binge-eating disorder: Fear and resignation. Int J Eat Disord. 2023.

Brownstone LM, Mihas P, Butler RM, Maman S, Peterson CB, Bulik CM, et al. Lived experiences of subjective binge eating: an inductive thematic analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 2021;54(12):2192–205.

Lord VM, Reiboldt W, Gonitzke D, Parker E, Peterson C. Experiences of recovery in binge-eating disorder: a qualitative approach using online message boards. Eat Weight Disord. 2018;23(1):95–105.

Salvia MG, Ritholz MD, Craigen KLE, Quatromoni PA. Managing type 2 diabetes or prediabetes and binge eating disorder: a qualitative study of patients’ perceptions and lived experiences. J Eat Disord. 2022;10(1):148.

Lewke-Bandara RS, Thapliyal P, Conti J, Hay P. It also taught me a lot about myself: a qualitative exploration of how men understand eating disorder recovery. J Eat Disord. 2020;8:3.

Eaton CM. Eating disorder recovery: a metaethnography. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2020;26(4):373–88.

van Bree ESJ, Slof-Op't Landt MCT, van Furth EF. Predictors of recovery in eating disorders: A focus on different definitions. Int J Eat Disord. 2023.

Bray B, Bray C, Bradley R, Zwickey H. Binge eating disorder is a social justice issue: a cross-sectional mixed-methods study of binge eating disorder experts' opinions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(10).

Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753–60.

Nettskjema Diktaphone Application. [Available from: https://www.uio.no/tjenester/it/adm-app/nettskjema/hjelp/diktafon.html .

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57.