No internet connection.

All search filters on the page have been cleared., your search has been saved..

- All content

- Dictionaries

- Encyclopedias

- Expert Insights

- Foundations

- How-to Guides

- Journal Articles

- Little Blue Books

- Little Green Books

- Project Planner

- Tools Directory

- Sign in to my profile My Profile

- Sign in Signed in

- My profile My Profile

The SAGE Handbook of Action Research

- Edition: Third Edition

- Edited by: Hilary Bradbury

- Publisher: SAGE Publications Ltd

- Publication year: 2015

- Online pub date: June 25, 2020

- Discipline: Sociology

- Methods: Action research , Theory , Participatory action research

- DOI: https:// doi. org/10.4135/9781473921290

- Keywords: inquiry , knowledge , organizations , publications , students , systems theory , teams Show all Show less

- Print ISBN: 9781446294543

- Online ISBN: 9781473921290

- Buy the book icon link

Subject index

The third edition of the SAGE Handbook of Action Research presents a fully updated version of the bestselling text, including new chapters written by key figures in the field covering emerging areas in healthcare, social work, education and international development, as well as an expanded ‘skills’ section which includes new consultant-relevant materials. Building on the strength of the previous editions, editor Hilary Bradbury has carefully developed the third edition to take a strong international approach to the topic of action research and thus expanding the already-impressive scale and scope of the work. In essence, the third edition follows in the footsteps of the landmark previous editions by mapping the current state of the discipline, as well as looking to the future of the field and exploring the issues at the cutting edge of the action research paradigm today. This volume is an essential resource for scholars and professionals engaged in social and political inquiry, organizational research and education.

Front Matter

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Notes on the Editor and Contributors

- Introduction: How to Situate and Define Action Research

- Chapter 1 | Introduction to Practices

- Chapter 2 | The Practice of Learning History: Local and Open System Approaches

- Chapter 3 | PRA, PLA and Pluralism: Practice and Theory

- Chapter 4 | Developing the Practice of Leading Change Through Insider Action Research: A Dynamic Capability Perspective

- Chapter 5 | Innovations in Appreciative Inquiry: Critical Appreciative Inquiry with Excluded Pakistani Women

- Chapter 6 | Collaborative Developmental Action Inquiry

- Chapter 7 | Systematization of Experiences: A Practice of Participatory Research from Latin America

- Chapter 8 | Empowerment Evaluation and Action Research: A Convergence of Values, Principles, and Purpose

- Chapter 9 | Action Evaluation: An Action Research Practice for the Participative Definition, Monitoring, and Assessment of Success in Social Innovation and Conflict Engagement

- Chapter 10 | Theatre in Participatory Action Research: Experiences from Bangladesh

- Chapter 11 | Using T-Groups to Develop Action Research Skills in Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous Environments

- Chapter 12 | The Action Research Practice of Urban Planning – An Example from Hong Kong

- Chapter 13 | The Artistry of Emancipatory Practice: Photovoice, Creative Techniques, and Feminist Anti-Racist Participatory Action Research

- Chapter 14 | Action Science Revisited: Building Knowledge Out of Practice to Transform Practice

- Chapter 15 | Systemic Intervention

- Chapter 16 | Community-Based Participatory Research with Communities Defined by Race, Ethnicity, and Disability: Translating Theory to Practice

- Chapter 17 | Action Learning

- Chapter 18 | The Network Leadership Innovation Lab: A Practice for Social Change

- Chapter 19 | Awareness-Based Action Research: Catching Social Reality Creation in Flight

- Chapter 20 | The World Café in Action Research Settings

- Chapter 21 | Ethnographic Action Research: Media, Information and Communicative Ecologies for Development Initiatives

- Chapter 22 | Re-Fashioning Citizens’ Juries: Participatory Democracy in Action

- Chapter 23 | The Practice of Helping Students to Find Their First Person Voice in Creating Living-Theories for Education

- Chapter 24 | The Practice of Teaching Co-Operative Inquiry

- Chapter 25 | Introduction to Exemplars

- Chapter 26 | Symbiosis of Action Research and Deliberative Democracy in the Context of Participatory Constitution-Making

- Chapter 27 | Action Research in Universities and Higher Education Worldwide

- Chapter 28 | ‘I’m Not Afraid of Him; That Dog Barks But He Don’t Bite’. PAR Processes, Gender Equity and Emancipation with Women in Yucatán, Mexico

- Chapter 29 | Insurgent Inquiry: Connecting Action Research, Impact Evaluation, and Global Strategy in a Rights-Based International Development NGO

- Chapter 30 | Action Research with Marginalized Immigrants’ Coming to Voice: Twenty Years of Social Movement Support in Taiwan and Still Going

- Chapter 31 | Improving Health and Well-being: Researching Alongside Marginalized People Across Diverse Domains

- Chapter 32 | After a Decade of Action Research: Impactful Systems Improvement in Swedish Healthcare

- Chapter 33 | Action Research as a Transformative Force in Management Education: Introducing the Collaboratory

- Chapter 34 | Achieving Equity in Education

- Chapter 35 | Introduction to Groundings

- Chapter 36 | Praxis – Retrieving the Roots of Action Research

- Chapter 37 | Core Issues in Modern Epistemology for Action Researchers: Dancing Between Knower and Known

- Chapter 38 | Social Construction and Research as Action

- Chapter 39 | How to Succeed in Action Research without Really Acting: Tracing the Development of Action Research to Constructivist Practice in Organizational Worklife

- Chapter 40 | Organization Development: Action Research for Organizational Change

- Chapter 41 | Evolutionary Systems Thinking: What Gregory Bateson, Kurt Lewin and Jacob Moreno Offered to Action Research that Still Remains to be Learned

- Chapter 42 | How Change Happens: The Implications of Complexity and Systems Thinking for Action Research

- Chapter 43 | Complex Systems and Emergence in Action Research

- Chapter 44 | Critical Theory and Critical Participatory Action Research

- Chapter 45 | Power and Knowledge

- Chapter 46 | Research, Participation and Social Transformation: Grounding Systematization of Experiences in Latin American Perspectives

- Chapter 47 | Knowledge Democracy, Community-based Action Research, the Global South and the Excluded North

- Chapter 48 | Participatory Action Research: Its Origins and Future in Women’s Ways

- Chapter 49 | The Location of Race in Action Research

- Chapter 50 | Sex and Sensibilities: Doing Action Research while Respecting even Inspiring Dignity

- Chapter 51 | Crowdsourcing and Action Research. Fostering People’s Participation in Research through Digital Media

- Chapter 52 | Naturally Emerging Regulation and the Danger of Delegitimizing Conventional Leadership: Drawing on the Example of Wikipedia

- Chapter 53 | Action Research in an Online World

- Chapter 54 | Large Scale Change Action Research

- Chapter 55 | Companions to Action Research: Reaching Beyond our Networks to Build Alignments and a Common Repository of Resources

- Chapter 56 | Action Research and Ecological Practice

- Chapter 57 | Ecofeminism and Systems Thinking: Shared Ethics of Care for Action Research

- Chapter 58 | The Integrating (Feminine) Reach of Action Research: A Nonet for Epistemological Voice

- Chapter 59 | Expanding Reach and Justice with PAR: Working with More than Humans

- Chapter 60 | Introduction to Skills

- Chapter 61 | Widening the Circle: Ethical Reflection in Action Research and the Practice of Structured Ethical Reflection

- Chapter 62 | The Skillful Means of Engaged Research

- Chapter 63 | Feelings in First Person Action Research

- Chapter 64 | Clearing Obstacles: An Exercise to Expand a Person’s Repertoire of Action

- Chapter 65 | A Cross-Cultural Approach with East-Asian Epistemology: Developing Soft Skills in Action Research

- Chapter 66 | Cultivating Intention (As we Enter the Fray): The Skillful Practice of Embodying Presence, Awareness, and Purpose as Action Researchers

- Chapter 67 | Holding Theory Skillfully in Consulting Interventions

- Chapter 68 | You Better Check Your Method Before You Wreck Your Method: Challenging and Transforming Photovoice

- Chapter 69 | Discovering Philosophical Assumptions that Guide Action Research: The Reflexive Toolbox Approach

- Chapter 70 | Radical Epistemology as Caffeine for Social Change

- Chapter 71 | Mediated Dialogue in Action Research

- Chapter 72 | Teaching the Heart of Action Research Skills: Breaking Free in the Classroom

- Chapter 73 | Practice of Mindful Intuition: Bi-directional Openness: The Skill of Expressing and Sensing Leadership that Serves a Group

- Chapter 74 | Designerly Ways for Action Research

- Chapter 75 | Nurturing Creative Destruction: Bringing Management Mindsets and Influence Skillsets to Health Care

- Chapter 76 | Teaching and Learning Reflective Practice in the Action Science/Action Inquiry Tradition

- Chapter 77 | From Research ‘on’ to Research ‘with’: Developing Skills for Research with Sex Workers

- Chapter 78 | Shared Inquiry Capabilities and Differing Inquiry Preferences: Navigating ‘Full Cycle’ Iterations of Action Research

- Chapter 79 | Unlocking the Secrets of Personal and Systemic Power: The Power Lab and Action Inquiry in the Classroom

Sign in to access this content

Get a 30 day free trial, more like this, sage recommends.

We found other relevant content for you on other Sage platforms.

Have you created a personal profile? Login or create a profile so that you can save clips, playlists and searches

- Sign in/register

Navigating away from this page will delete your results

Please save your results to "My Self-Assessments" in your profile before navigating away from this page.

Sign in to my profile

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Learning Resources have to offer.

You must have a valid academic email address to sign up.

Get off-campus access

- View or download all content my institution has access to.

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Research Methods has to offer.

- view my profile

- view my lists

Action Research

- First Online: 02 January 2023

Cite this chapter

- Janet Mola Okoko 4

Part of the book series: Springer Texts in Education ((SPTE))

3706 Accesses

The term Action Research was first credited by scholars and practitioners to Kurt Lewin’s work from the mid-1930’s. Action Research began to assert its place as a distinct type of research in the social sciences in the mid-1940’s, after Lewin’s article entitled “Action Research and Minority Problems”.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Adelman, C. (1993). Kurt Lewin and the origins of action research. Educational Action Research, 1 (1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965079930010102

Article Google Scholar

Andronic, R. L. (2010). A brief history of action research. Review of the Air Force Academy 144–149. http://www.afahc.ro/ro/revista/Nr_2_2010/2.2010%20Andronic.pdf

Creswell, J., & Guetterman, T. (2019). Educational research: Planning, conducting and evaluating qualitative and quantitative research . Pearson.

Google Scholar

Duesbery, L., & Twyman T. (2020). 100 questions and answers about action research . SAGE.

Helskog, G. H. (2014). Justifying action research. Educational Action Research, 22 (1), 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2013.856769

Hendricks, C. C. (2017). Improving schools through action research: A reflective practice approach (4th ed.). Pearson.

Mackenzie, J., Tan, P. L., Hoverman, S., & Baldwin, C. (2012). The value and limitations of participatory action research methodology. Journal of Hydrology, 474, 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2012.09.008

Masters, J. (1995). The history of action research. In I. Hughes (Ed.) Action research electronic reader . The University of Sydney. http://www.behs.cchs.usyd.edu.au/arow/Reader/rmasters.htm

McNiff, J. (2013). Action research principles and practice . Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Mertler, C. (2020). Action research: Improving schools and empowering educators . SAGE.

Thorkildsen, A. (2013). Participation, power and democracy: Exploring the tensional field between empowerment and constraint in action research. International Journal of Action Research, 9 (1), 15–37. https://www.budrich-journals.de/index.php/ijar/article/view/26732

Stringer, E. T. (2008). Action research in education . Pearson Prentice Hall.

Additional Reading

Johnson, A. P. (2008). A short guide to action research (3rd Ed.). Allyn and Bacon.

McNiff, J. (2016). You and your action research project . Routledge.

Mertler, C. A. (2016). Leading and facilitating educational change through action research learning communities. Journal of Ethical Educational Leadership , 3 (3), 1–11.

Mertler, C. A (2018). Action research communities professional learning, empowerment, and improvement through collaborative action research . Routledge.

Sagor, R. (2011). The action research guidebook: A four-stage process for educators and school teams . Corwin Press.

Online Resources

Overview of Action Research (2018) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cmBSKK9izao 12:48 min

Action Research development (2020) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ns7S-N4_aJ0 2:08 min

What is Action Research (2016) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kTwmdPSSgDs 2:02 min

What is Action Research (2017) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ov3F3pdhNkk 2:24 min

Personal empowerment through reflection and learning (2019) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uzDsT-25w14 10:52 min

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada

Janet Mola Okoko

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Janet Mola Okoko .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Educational Administration, College of Education, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada

Scott Tunison

Department of Educational Administration, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada

Keith D. Walker

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Okoko, J.M. (2023). Action Research. In: Okoko, J.M., Tunison, S., Walker, K.D. (eds) Varieties of Qualitative Research Methods. Springer Texts in Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04394-9_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04394-9_2

Published : 02 January 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-04396-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-04394-9

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

Published on January 27, 2023 by Tegan George . Revised on January 12, 2024.

Table of contents

Types of action research, action research models, examples of action research, action research vs. traditional research, advantages and disadvantages of action research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about action research.

There are 2 common types of action research: participatory action research and practical action research.

- Participatory action research emphasizes that participants should be members of the community being studied, empowering those directly affected by outcomes of said research. In this method, participants are effectively co-researchers, with their lived experiences considered formative to the research process.

- Practical action research focuses more on how research is conducted and is designed to address and solve specific issues.

Both types of action research are more focused on increasing the capacity and ability of future practitioners than contributing to a theoretical body of knowledge.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Action research is often reflected in 3 action research models: operational (sometimes called technical), collaboration, and critical reflection.

- Operational (or technical) action research is usually visualized like a spiral following a series of steps, such as “planning → acting → observing → reflecting.”

- Collaboration action research is more community-based, focused on building a network of similar individuals (e.g., college professors in a given geographic area) and compiling learnings from iterated feedback cycles.

- Critical reflection action research serves to contextualize systemic processes that are already ongoing (e.g., working retroactively to analyze existing school systems by questioning why certain practices were put into place and developed the way they did).

Action research is often used in fields like education because of its iterative and flexible style.

After the information was collected, the students were asked where they thought ramps or other accessibility measures would be best utilized, and the suggestions were sent to school administrators. Example: Practical action research Science teachers at your city’s high school have been witnessing a year-over-year decline in standardized test scores in chemistry. In seeking the source of this issue, they studied how concepts are taught in depth, focusing on the methods, tools, and approaches used by each teacher.

Action research differs sharply from other types of research in that it seeks to produce actionable processes over the course of the research rather than contributing to existing knowledge or drawing conclusions from datasets. In this way, action research is formative , not summative , and is conducted in an ongoing, iterative way.

As such, action research is different in purpose, context, and significance and is a good fit for those seeking to implement systemic change.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Action research comes with advantages and disadvantages.

- Action research is highly adaptable , allowing researchers to mold their analysis to their individual needs and implement practical individual-level changes.

- Action research provides an immediate and actionable path forward for solving entrenched issues, rather than suggesting complicated, longer-term solutions rooted in complex data.

- Done correctly, action research can be very empowering , informing social change and allowing participants to effect that change in ways meaningful to their communities.

Disadvantages

- Due to their flexibility, action research studies are plagued by very limited generalizability and are very difficult to replicate . They are often not considered theoretically rigorous due to the power the researcher holds in drawing conclusions.

- Action research can be complicated to structure in an ethical manner . Participants may feel pressured to participate or to participate in a certain way.

- Action research is at high risk for research biases such as selection bias , social desirability bias , or other types of cognitive biases .

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Action research is conducted in order to solve a particular issue immediately, while case studies are often conducted over a longer period of time and focus more on observing and analyzing a particular ongoing phenomenon.

Action research is focused on solving a problem or informing individual and community-based knowledge in a way that impacts teaching, learning, and other related processes. It is less focused on contributing theoretical input, instead producing actionable input.

Action research is particularly popular with educators as a form of systematic inquiry because it prioritizes reflection and bridges the gap between theory and practice. Educators are able to simultaneously investigate an issue as they solve it, and the method is very iterative and flexible.

A cycle of inquiry is another name for action research . It is usually visualized in a spiral shape following a series of steps, such as “planning → acting → observing → reflecting.”

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

George, T. (2024, January 12). What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 28, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/action-research/

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Research methods in education (8th edition). Routledge.

Naughton, G. M. (2001). Action research (1st edition). Routledge.

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is an observational study | guide & examples, primary research | definition, types, & examples, guide to experimental design | overview, steps, & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 What is Action Research for Classroom Teachers?

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

- What is the nature of action research?

- How does action research develop in the classroom?

- What models of action research work best for your classroom?

- What are the epistemological, ontological, theoretical underpinnings of action research?

Educational research provides a vast landscape of knowledge on topics related to teaching and learning, curriculum and assessment, students’ cognitive and affective needs, cultural and socio-economic factors of schools, and many other factors considered viable to improving schools. Educational stakeholders rely on research to make informed decisions that ultimately affect the quality of schooling for their students. Accordingly, the purpose of educational research is to engage in disciplined inquiry to generate knowledge on topics significant to the students, teachers, administrators, schools, and other educational stakeholders. Just as the topics of educational research vary, so do the approaches to conducting educational research in the classroom. Your approach to research will be shaped by your context, your professional identity, and paradigm (set of beliefs and assumptions that guide your inquiry). These will all be key factors in how you generate knowledge related to your work as an educator.

Action research is an approach to educational research that is commonly used by educational practitioners and professionals to examine, and ultimately improve, their pedagogy and practice. In this way, action research represents an extension of the reflection and critical self-reflection that an educator employs on a daily basis in their classroom. When students are actively engaged in learning, the classroom can be dynamic and uncertain, demanding the constant attention of the educator. Considering these demands, educators are often only able to engage in reflection that is fleeting, and for the purpose of accommodation, modification, or formative assessment. Action research offers one path to more deliberate, substantial, and critical reflection that can be documented and analyzed to improve an educator’s practice.

Purpose of Action Research

As one of many approaches to educational research, it is important to distinguish the potential purposes of action research in the classroom. This book focuses on action research as a method to enable and support educators in pursuing effective pedagogical practices by transforming the quality of teaching decisions and actions, to subsequently enhance student engagement and learning. Being mindful of this purpose, the following aspects of action research are important to consider as you contemplate and engage with action research methodology in your classroom:

- Action research is a process for improving educational practice. Its methods involve action, evaluation, and reflection. It is a process to gather evidence to implement change in practices.

- Action research is participative and collaborative. It is undertaken by individuals with a common purpose.

- Action research is situation and context-based.

- Action research develops reflection practices based on the interpretations made by participants.

- Knowledge is created through action and application.

- Action research can be based in problem-solving, if the solution to the problem results in the improvement of practice.

- Action research is iterative; plans are created, implemented, revised, then implemented, lending itself to an ongoing process of reflection and revision.

- In action research, findings emerge as action develops and takes place; however, they are not conclusive or absolute, but ongoing (Koshy, 2010, pgs. 1-2).

In thinking about the purpose of action research, it is helpful to situate action research as a distinct paradigm of educational research. I like to think about action research as part of the larger concept of living knowledge. Living knowledge has been characterized as “a quest for life, to understand life and to create… knowledge which is valid for the people with whom I work and for myself” (Swantz, in Reason & Bradbury, 2001, pg. 1). Why should educators care about living knowledge as part of educational research? As mentioned above, action research is meant “to produce practical knowledge that is useful to people in the everyday conduct of their lives and to see that action research is about working towards practical outcomes” (Koshy, 2010, pg. 2). However, it is also about:

creating new forms of understanding, since action without reflection and understanding is blind, just as theory without action is meaningless. The participatory nature of action research makes it only possible with, for and by persons and communities, ideally involving all stakeholders both in the questioning and sense making that informs the research, and in the action, which is its focus. (Reason & Bradbury, 2001, pg. 2)

In an effort to further situate action research as living knowledge, Jean McNiff reminds us that “there is no such ‘thing’ as ‘action research’” (2013, pg. 24). In other words, action research is not static or finished, it defines itself as it proceeds. McNiff’s reminder characterizes action research as action-oriented, and a process that individuals go through to make their learning public to explain how it informs their practice. Action research does not derive its meaning from an abstract idea, or a self-contained discovery – action research’s meaning stems from the way educators negotiate the problems and successes of living and working in the classroom, school, and community.

While we can debate the idea of action research, there are people who are action researchers, and they use the idea of action research to develop principles and theories to guide their practice. Action research, then, refers to an organization of principles that guide action researchers as they act on shared beliefs, commitments, and expectations in their inquiry.

Reflection and the Process of Action Research

When an individual engages in reflection on their actions or experiences, it is typically for the purpose of better understanding those experiences, or the consequences of those actions to improve related action and experiences in the future. Reflection in this way develops knowledge around these actions and experiences to help us better regulate those actions in the future. The reflective process generates new knowledge regularly for classroom teachers and informs their classroom actions.

Unfortunately, the knowledge generated by educators through the reflective process is not always prioritized among the other sources of knowledge educators are expected to utilize in the classroom. Educators are expected to draw upon formal types of knowledge, such as textbooks, content standards, teaching standards, district curriculum and behavioral programs, etc., to gain new knowledge and make decisions in the classroom. While these forms of knowledge are important, the reflective knowledge that educators generate through their pedagogy is the amalgamation of these types of knowledge enacted in the classroom. Therefore, reflective knowledge is uniquely developed based on the action and implementation of an educator’s pedagogy in the classroom. Action research offers a way to formalize the knowledge generated by educators so that it can be utilized and disseminated throughout the teaching profession.

Research is concerned with the generation of knowledge, and typically creating knowledge related to a concept, idea, phenomenon, or topic. Action research generates knowledge around inquiry in practical educational contexts. Action research allows educators to learn through their actions with the purpose of developing personally or professionally. Due to its participatory nature, the process of action research is also distinct in educational research. There are many models for how the action research process takes shape. I will share a few of those here. Each model utilizes the following processes to some extent:

- Plan a change;

- Take action to enact the change;

- Observe the process and consequences of the change;

- Reflect on the process and consequences;

- Act, observe, & reflect again and so on.

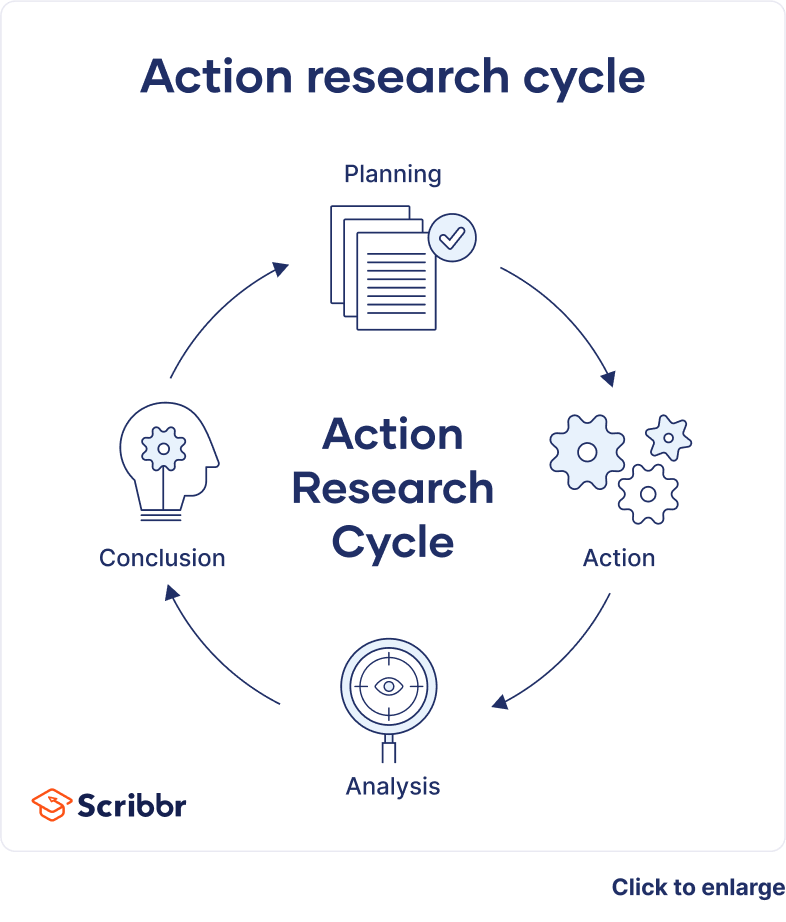

Figure 1.1 Basic action research cycle

There are many other models that supplement the basic process of action research with other aspects of the research process to consider. For example, figure 1.2 illustrates a spiral model of action research proposed by Kemmis and McTaggart (2004). The spiral model emphasizes the cyclical process that moves beyond the initial plan for change. The spiral model also emphasizes revisiting the initial plan and revising based on the initial cycle of research:

Figure 1.2 Interpretation of action research spiral, Kemmis and McTaggart (2004, p. 595)

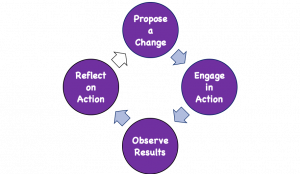

Other models of action research reorganize the process to emphasize the distinct ways knowledge takes shape in the reflection process. O’Leary’s (2004, p. 141) model, for example, recognizes that the research may take shape in the classroom as knowledge emerges from the teacher’s observations. O’Leary highlights the need for action research to be focused on situational understanding and implementation of action, initiated organically from real-time issues:

Figure 1.3 Interpretation of O’Leary’s cycles of research, O’Leary (2000, p. 141)

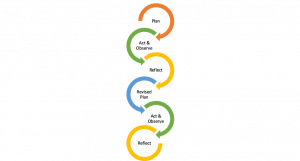

Lastly, Macintyre’s (2000, p. 1) model, offers a different characterization of the action research process. Macintyre emphasizes a messier process of research with the initial reflections and conclusions as the benchmarks for guiding the research process. Macintyre emphasizes the flexibility in planning, acting, and observing stages to allow the process to be naturalistic. Our interpretation of Macintyre process is below:

Figure 1.4 Interpretation of the action research cycle, Macintyre (2000, p. 1)

We believe it is important to prioritize the flexibility of the process, and encourage you to only use these models as basic guides for your process. Your process may look similar, or you may diverge from these models as you better understand your students, context, and data.

Definitions of Action Research and Examples

At this point, it may be helpful for readers to have a working definition of action research and some examples to illustrate the methodology in the classroom. Bassey (1998, p. 93) offers a very practical definition and describes “action research as an inquiry which is carried out in order to understand, to evaluate and then to change, in order to improve educational practice.” Cohen and Manion (1994, p. 192) situate action research differently, and describe action research as emergent, writing:

essentially an on-the-spot procedure designed to deal with a concrete problem located in an immediate situation. This means that ideally, the step-by-step process is constantly monitored over varying periods of time and by a variety of mechanisms (questionnaires, diaries, interviews and case studies, for example) so that the ensuing feedback may be translated into modifications, adjustment, directional changes, redefinitions, as necessary, so as to bring about lasting benefit to the ongoing process itself rather than to some future occasion.

Lastly, Koshy (2010, p. 9) describes action research as:

a constructive inquiry, during which the researcher constructs his or her knowledge of specific issues through planning, acting, evaluating, refining and learning from the experience. It is a continuous learning process in which the researcher learns and also shares the newly generated knowledge with those who may benefit from it.

These definitions highlight the distinct features of action research and emphasize the purposeful intent of action researchers to improve, refine, reform, and problem-solve issues in their educational context. To better understand the distinctness of action research, these are some examples of action research topics:

Examples of Action Research Topics

- Flexible seating in 4th grade classroom to increase effective collaborative learning.

- Structured homework protocols for increasing student achievement.

- Developing a system of formative feedback for 8th grade writing.

- Using music to stimulate creative writing.

- Weekly brown bag lunch sessions to improve responses to PD from staff.

- Using exercise balls as chairs for better classroom management.

Action Research in Theory

Action research-based inquiry in educational contexts and classrooms involves distinct participants – students, teachers, and other educational stakeholders within the system. All of these participants are engaged in activities to benefit the students, and subsequently society as a whole. Action research contributes to these activities and potentially enhances the participants’ roles in the education system. Participants’ roles are enhanced based on two underlying principles:

- communities, schools, and classrooms are sites of socially mediated actions, and action research provides a greater understanding of self and new knowledge of how to negotiate these socially mediated environments;

- communities, schools, and classrooms are part of social systems in which humans interact with many cultural tools, and action research provides a basis to construct and analyze these interactions.

In our quest for knowledge and understanding, we have consistently analyzed human experience over time and have distinguished between types of reality. Humans have constantly sought “facts” and “truth” about reality that can be empirically demonstrated or observed.

Social systems are based on beliefs, and generally, beliefs about what will benefit the greatest amount of people in that society. Beliefs, and more specifically the rationale or support for beliefs, are not always easy to demonstrate or observe as part of our reality. Take the example of an English Language Arts teacher who prioritizes argumentative writing in her class. She believes that argumentative writing demonstrates the mechanics of writing best among types of writing, while also providing students a skill they will need as citizens and professionals. While we can observe the students writing, and we can assess their ability to develop a written argument, it is difficult to observe the students’ understanding of argumentative writing and its purpose in their future. This relates to the teacher’s beliefs about argumentative writing; we cannot observe the real value of the teaching of argumentative writing. The teacher’s rationale and beliefs about teaching argumentative writing are bound to the social system and the skills their students will need to be active parts of that system. Therefore, our goal through action research is to demonstrate the best ways to teach argumentative writing to help all participants understand its value as part of a social system.

The knowledge that is conveyed in a classroom is bound to, and justified by, a social system. A postmodernist approach to understanding our world seeks knowledge within a social system, which is directly opposed to the empirical or positivist approach which demands evidence based on logic or science as rationale for beliefs. Action research does not rely on a positivist viewpoint to develop evidence and conclusions as part of the research process. Action research offers a postmodernist stance to epistemology (theory of knowledge) and supports developing questions and new inquiries during the research process. In this way action research is an emergent process that allows beliefs and decisions to be negotiated as reality and meaning are being constructed in the socially mediated space of the classroom.

Theorizing Action Research for the Classroom

All research, at its core, is for the purpose of generating new knowledge and contributing to the knowledge base of educational research. Action researchers in the classroom want to explore methods of improving their pedagogy and practice. The starting place of their inquiry stems from their pedagogy and practice, so by nature the knowledge created from their inquiry is often contextually specific to their classroom, school, or community. Therefore, we should examine the theoretical underpinnings of action research for the classroom. It is important to connect action research conceptually to experience; for example, Levin and Greenwood (2001, p. 105) make these connections:

- Action research is context bound and addresses real life problems.

- Action research is inquiry where participants and researchers cogenerate knowledge through collaborative communicative processes in which all participants’ contributions are taken seriously.

- The meanings constructed in the inquiry process lead to social action or these reflections and action lead to the construction of new meanings.

- The credibility/validity of action research knowledge is measured according to whether the actions that arise from it solve problems (workability) and increase participants’ control over their own situation.

Educators who engage in action research will generate new knowledge and beliefs based on their experiences in the classroom. Let us emphasize that these are all important to you and your work, as both an educator and researcher. It is these experiences, beliefs, and theories that are often discounted when more official forms of knowledge (e.g., textbooks, curriculum standards, districts standards) are prioritized. These beliefs and theories based on experiences should be valued and explored further, and this is one of the primary purposes of action research in the classroom. These beliefs and theories should be valued because they were meaningful aspects of knowledge constructed from teachers’ experiences. Developing meaning and knowledge in this way forms the basis of constructivist ideology, just as teachers often try to get their students to construct their own meanings and understandings when experiencing new ideas.

Classroom Teachers Constructing their Own Knowledge

Most of you are probably at least minimally familiar with constructivism, or the process of constructing knowledge. However, what is constructivism precisely, for the purposes of action research? Many scholars have theorized constructivism and have identified two key attributes (Koshy, 2010; von Glasersfeld, 1987):

- Knowledge is not passively received, but actively developed through an individual’s cognition;

- Human cognition is adaptive and finds purpose in organizing the new experiences of the world, instead of settling for absolute or objective truth.

Considering these two attributes, constructivism is distinct from conventional knowledge formation because people can develop a theory of knowledge that orders and organizes the world based on their experiences, instead of an objective or neutral reality. When individuals construct knowledge, there are interactions between an individual and their environment where communication, negotiation and meaning-making are collectively developing knowledge. For most educators, constructivism may be a natural inclination of their pedagogy. Action researchers have a similar relationship to constructivism because they are actively engaged in a process of constructing knowledge. However, their constructions may be more formal and based on the data they collect in the research process. Action researchers also are engaged in the meaning making process, making interpretations from their data. These aspects of the action research process situate them in the constructivist ideology. Just like constructivist educators, action researchers’ constructions of knowledge will be affected by their individual and professional ideas and values, as well as the ecological context in which they work (Biesta & Tedder, 2006). The relations between constructivist inquiry and action research is important, as Lincoln (2001, p. 130) states:

much of the epistemological, ontological, and axiological belief systems are the same or similar, and methodologically, constructivists and action researchers work in similar ways, relying on qualitative methods in face-to-face work, while buttressing information, data and background with quantitative method work when necessary or useful.

While there are many links between action research and educators in the classroom, constructivism offers the most familiar and practical threads to bind the beliefs of educators and action researchers.

Epistemology, Ontology, and Action Research

It is also important for educators to consider the philosophical stances related to action research to better situate it with their beliefs and reality. When researchers make decisions about the methodology they intend to use, they will consider their ontological and epistemological stances. It is vital that researchers clearly distinguish their philosophical stances and understand the implications of their stance in the research process, especially when collecting and analyzing their data. In what follows, we will discuss ontological and epistemological stances in relation to action research methodology.

Ontology, or the theory of being, is concerned with the claims or assumptions we make about ourselves within our social reality – what do we think exists, what does it look like, what entities are involved and how do these entities interact with each other (Blaikie, 2007). In relation to the discussion of constructivism, generally action researchers would consider their educational reality as socially constructed. Social construction of reality happens when individuals interact in a social system. Meaningful construction of concepts and representations of reality develop through an individual’s interpretations of others’ actions. These interpretations become agreed upon by members of a social system and become part of social fabric, reproduced as knowledge and beliefs to develop assumptions about reality. Researchers develop meaningful constructions based on their experiences and through communication. Educators as action researchers will be examining the socially constructed reality of schools. In the United States, many of our concepts, knowledge, and beliefs about schooling have been socially constructed over the last hundred years. For example, a group of teachers may look at why fewer female students enroll in upper-level science courses at their school. This question deals directly with the social construction of gender and specifically what careers females have been conditioned to pursue. We know this is a social construction in some school social systems because in other parts of the world, or even the United States, there are schools that have more females enrolled in upper level science courses than male students. Therefore, the educators conducting the research have to recognize the socially constructed reality of their school and consider this reality throughout the research process. Action researchers will use methods of data collection that support their ontological stance and clarify their theoretical stance throughout the research process.

Koshy (2010, p. 23-24) offers another example of addressing the ontological challenges in the classroom:

A teacher who was concerned with increasing her pupils’ motivation and enthusiasm for learning decided to introduce learning diaries which the children could take home. They were invited to record their reactions to the day’s lessons and what they had learnt. The teacher reported in her field diary that the learning diaries stimulated the children’s interest in her lessons, increased their capacity to learn, and generally improved their level of participation in lessons. The challenge for the teacher here is in the analysis and interpretation of the multiplicity of factors accompanying the use of diaries. The diaries were taken home so the entries may have been influenced by discussions with parents. Another possibility is that children felt the need to please their teacher. Another possible influence was that their increased motivation was as a result of the difference in style of teaching which included more discussions in the classroom based on the entries in the dairies.

Here you can see the challenge for the action researcher is working in a social context with multiple factors, values, and experiences that were outside of the teacher’s control. The teacher was only responsible for introducing the diaries as a new style of learning. The students’ engagement and interactions with this new style of learning were all based upon their socially constructed notions of learning inside and outside of the classroom. A researcher with a positivist ontological stance would not consider these factors, and instead might simply conclude that the dairies increased motivation and interest in the topic, as a result of introducing the diaries as a learning strategy.

Epistemology, or the theory of knowledge, signifies a philosophical view of what counts as knowledge – it justifies what is possible to be known and what criteria distinguishes knowledge from beliefs (Blaikie, 1993). Positivist researchers, for example, consider knowledge to be certain and discovered through scientific processes. Action researchers collect data that is more subjective and examine personal experience, insights, and beliefs.

Action researchers utilize interpretation as a means for knowledge creation. Action researchers have many epistemologies to choose from as means of situating the types of knowledge they will generate by interpreting the data from their research. For example, Koro-Ljungberg et al., (2009) identified several common epistemologies in their article that examined epistemological awareness in qualitative educational research, such as: objectivism, subjectivism, constructionism, contextualism, social epistemology, feminist epistemology, idealism, naturalized epistemology, externalism, relativism, skepticism, and pluralism. All of these epistemological stances have implications for the research process, especially data collection and analysis. Please see the table on pages 689-90, linked below for a sketch of these potential implications:

Again, Koshy (2010, p. 24) provides an excellent example to illustrate the epistemological challenges within action research:

A teacher of 11-year-old children decided to carry out an action research project which involved a change in style in teaching mathematics. Instead of giving children mathematical tasks displaying the subject as abstract principles, she made links with other subjects which she believed would encourage children to see mathematics as a discipline that could improve their understanding of the environment and historic events. At the conclusion of the project, the teacher reported that applicable mathematics generated greater enthusiasm and understanding of the subject.

The educator/researcher engaged in action research-based inquiry to improve an aspect of her pedagogy. She generated knowledge that indicated she had improved her students’ understanding of mathematics by integrating it with other subjects – specifically in the social and ecological context of her classroom, school, and community. She valued constructivism and students generating their own understanding of mathematics based on related topics in other subjects. Action researchers working in a social context do not generate certain knowledge, but knowledge that emerges and can be observed and researched again, building upon their knowledge each time.

Researcher Positionality in Action Research

In this first chapter, we have discussed a lot about the role of experiences in sparking the research process in the classroom. Your experiences as an educator will shape how you approach action research in your classroom. Your experiences as a person in general will also shape how you create knowledge from your research process. In particular, your experiences will shape how you make meaning from your findings. It is important to be clear about your experiences when developing your methodology too. This is referred to as researcher positionality. Maher and Tetreault (1993, p. 118) define positionality as:

Gender, race, class, and other aspects of our identities are markers of relational positions rather than essential qualities. Knowledge is valid when it includes an acknowledgment of the knower’s specific position in any context, because changing contextual and relational factors are crucial for defining identities and our knowledge in any given situation.

By presenting your positionality in the research process, you are signifying the type of socially constructed, and other types of, knowledge you will be using to make sense of the data. As Maher and Tetreault explain, this increases the trustworthiness of your conclusions about the data. This would not be possible with a positivist ontology. We will discuss positionality more in chapter 6, but we wanted to connect it to the overall theoretical underpinnings of action research.

Advantages of Engaging in Action Research in the Classroom

In the following chapters, we will discuss how action research takes shape in your classroom, and we wanted to briefly summarize the key advantages to action research methodology over other types of research methodology. As Koshy (2010, p. 25) notes, action research provides useful methodology for school and classroom research because:

Advantages of Action Research for the Classroom

- research can be set within a specific context or situation;

- researchers can be participants – they don’t have to be distant and detached from the situation;

- it involves continuous evaluation and modifications can be made easily as the project progresses;

- there are opportunities for theory to emerge from the research rather than always follow a previously formulated theory;

- the study can lead to open-ended outcomes;

- through action research, a researcher can bring a story to life.

Action Research Copyright © by J. Spencer Clark; Suzanne Porath; Julie Thiele; and Morgan Jobe is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

How social science helps us combat climate change

- March 19, 2024

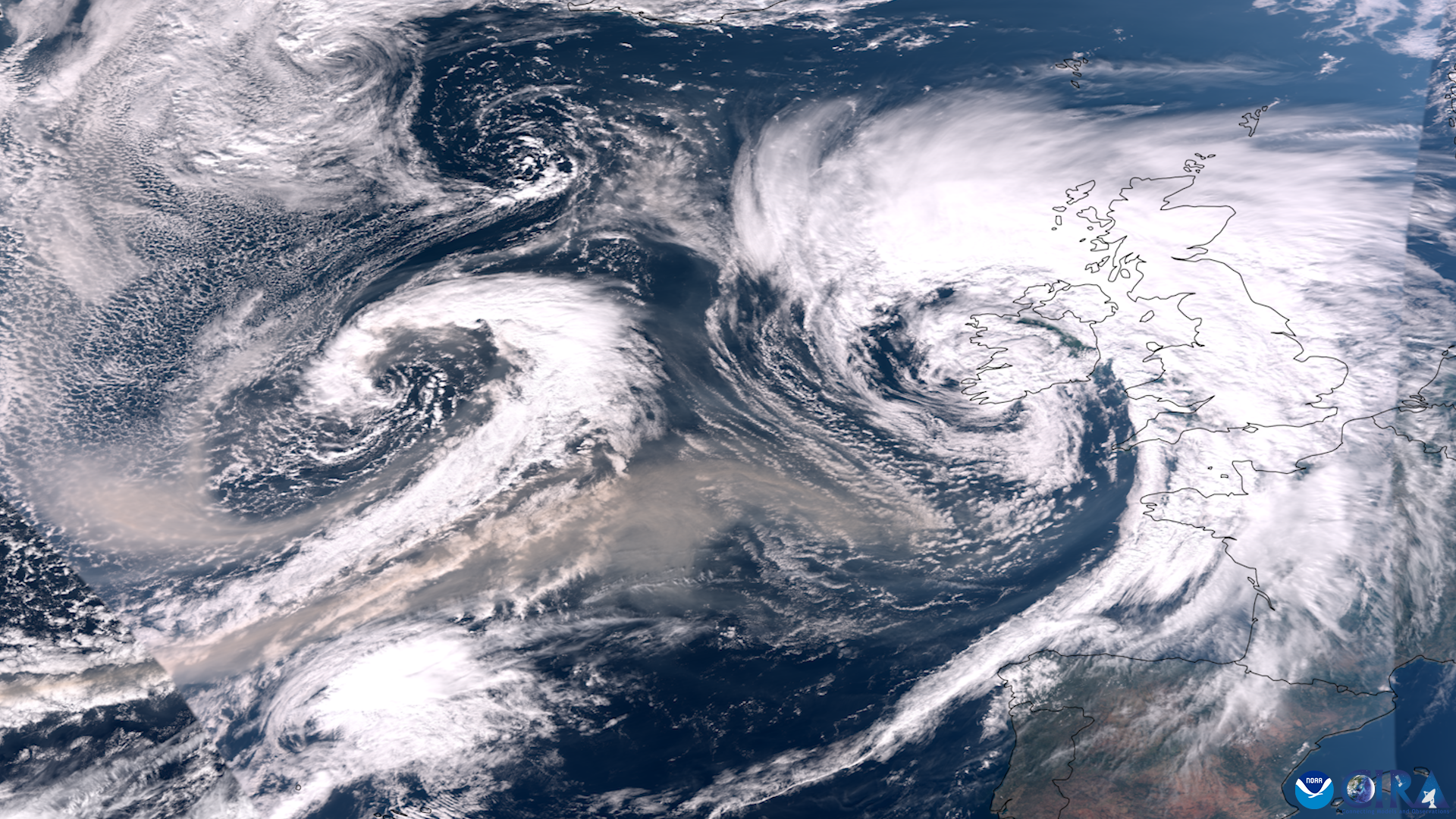

Meet three social scientist authors of the Fifth National Climate Assessment

One of the strengths of the Fifth National Climate Assessment is its expanded inclusion of social science across every part of the new report. We caught up with three NOAA authors of the climate assessment to hear how social science when combined with physical science can help our nation find and put to work solutions to the climate crisis with equity and effectiveness.

Ariela Zycherman

Agency chapter lead for the social systems and justice chapter and chapter author for the overview chapter, from noaa’s climate program office, climate and societal interactions division..

Caption: Ariela Zycherman prepares for a kayak trip in the coastal waters off Stonington, Maine. Photo courtesy of Ariela Zycherman.

Why did you take on this role of a lead author?

Serving as an agency chapter lead for the Social Systems and Justice chapter and an author on the Overview chapter has been one of the most exciting moments of my career as a federal social scientist. I am trained as an environmental and applied anthropologist, and my interests are in understanding the complex ways communities and households engage with their environments and find meaning in them. These patterns are shaped both by internal cultural systems and by larger systems of economics, politics, society and environment. Often, there is a dominance of physical data in climate assessments. This information is vital to understanding climatic hazards, but it is most impactful when combined with social data, which offers important contextual information on why and how these hazards create serious risks for communities, as well as how this information might be used with economic, political, or social knowledge to make practical, implementable and effective decisions.

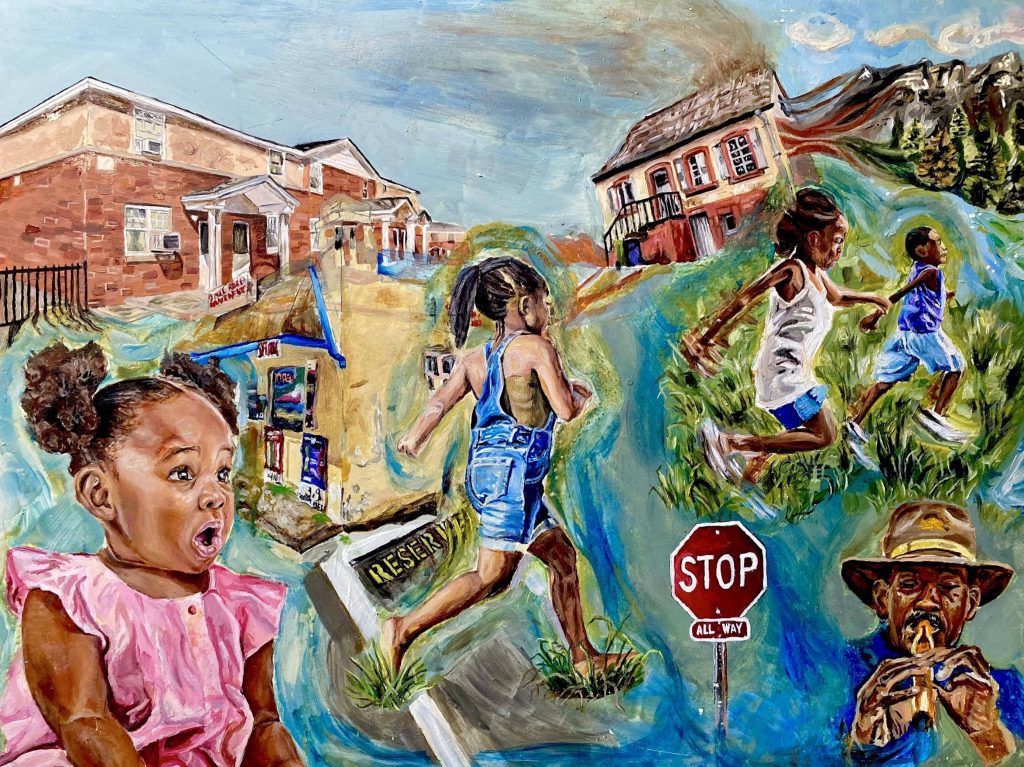

Focusing on just physical data can also mask inequalities in why impacts are more severe in one area than another, as often it is not just the risk of a storm, for example, but the investments or lack of investments in resilient infrastructures that can exacerbate the storm’s impacts. In the Fifth National Climate Assessment, there is a clear understanding that humans are at the center of climate change, this includes as drivers of it, recipients of its impacts, and creators of resilience building actions. For me, the incorporation of social sciences, like anthropology, across the NCA is a long awaited and celebrated step in thinking comprehensively about climate change and it opens up doors to have meaningful conversations about peoples’ experiences of climate change and how real, effective, equitable and lasting solutions can be developed.

What are the Main Messages of your Chapter?

- Social systems are changing the climate and distributing its impacts inequitably. Social systems refers to the institutions, policies, programs, practices, values, behaviors and governance models that shape our assumptions and activities around climate change, these systems not only drive processes that create climate change, like the production of greenhouse gases and where, but also where risks to climate hazards are greatest because of processes of investment or disinvestment in communities over time.

- Social systems structure how people know and communicate about climate change. People’s experiences with climate change are guided by their educations, cultures, traditions, economies, values and uses of and changes to their environments. This diversity of approaches shapes how people interpret and/or drive the changes around them, as well as respond to climate change. To address climate change, processes that engage with multiple ways of knowing, like co-production, help create relevant and appropriate solutions.

- Climate justice is possible if processes like migration and energy transitions are equitable. Climate justice recognizes that the inequitable distribution of resources and other social and political capital impacts the capacity for adaptation during the upheaval created by climate change. Adaptive and mitigative actions, like migration or using renewable energy technologies, have the potential to create co-benefits that not only address climate change, but also remediate past injustices.

Main Challenges?

Rather than focus on challenges, I would like to focus on my hope for a positive climate future. The chapter argues that a just transition is possible. A just transition refers to mitigating and adapting to climate change in a managed process that ensures equitable access to jobs, environmental goods and quality of life. The chapter highlights that we already have the tools to think through how justice can be applied to not only understanding how climate injustices have come about, but also to the creation of implementable adaptation and mitigation actions. By focusing on the complexities of governance models, including legal, political and decisional spaces, decision makers and communities can focus on the structural issues that create inequities and then identify approaches to incorporate multiple perspectives and ensure adequate resources are available to implement them.

Monica Grasso

Agency chapter lead for the economics chapter and noaa’s chief economist.

Caption: Monica Grasso enjoys a day of taking photos of waterfowl and marsh birds in Isle of Wight Park in Worcester County, Maryland. Photo courtesy of Monica Grasso

Why did you take on this role of lead author?

The opportunity to participate in the development of the first Economics chapter in the National Climate Assessment was a one of a kind opportunity to work with experts and show the state of our knowledge of the economic impacts from our changing environment. I have a passion for nature and the outdoors and this was the reason I decided to become an economist. Economics is a common language between individuals and businesses and I wanted to pursue the challenge of demonstrating how natural resources bring value to society.

Main messages of your chapter?

Extreme weather events affect the U.S. economy in many different ways, impacting transportation, agricultural production, tourism and many other economic activities. The increase in frequency and intensity of these events are expected to impose new costs to the U.S. economy and potentially slow our economic growth. We already see some markets and budgets responding to current and anticipated climate changes, and we expect stronger responses as climate change progresses. For example, as the risk of climate extremes grows, new costs and challenges will emerge in insurance systems and public budgets that were not originally designed to respond to climate change. Another important issue is that we expect that these impacts from climate extremes will be unequal across different communities, affecting certain regions, industries and socioeconomic groups more than others.The inequality comes from the fact that certain communities and individuals are more sensitive to climate, have more exposure to these events, and/or lack the resources to adapt and recover from the damages caused by these extreme events.

Main challenges?

One of the major challenges we identified during this process is how to deal with the uncertainty related to the unknown trajectory of future greenhouse gas emissions and associated risks. The uncertainty caused by climate change is itself an economic burden since most individuals and businesses are generally risk averse. As the risk of climate extremes grows, we expect new costs and challenges to emerge in insurance systems, public budgets and other economic systems that were not originally designed to respond to climate change. For example: anticipation of future flood risks has begun to reduce the prices of vulnerable properties. But there are still barriers that prevent market prices from adjusting to reflect climate risks due to inaccurate information or incomplete understanding of the relevant climate risks. In addition, there are also broad research gaps remaining about unequal climate change impacts across demographics, people with differing health status, and socio-economic background.

Promising adaptation example

America’s energy transition will create new economic opportunities, as increased demand for clean energy and low-carbon technologies leads to long-term expansion in most states’ energy and decarbonization workforce. New job opportunities are anticipated to support new and emerging technologies, as well as increased demand for energy efficiency retrofits, clean energy, and resilience measures. For example, grid expansion and energy efficiency projects are already creating new jobs in a number of states.

Caitlin Simpson

Agency chapter lead for the adaptation chapter from noaa’s climate program office climate and societal interactions division.

Caption: Caitlin Simpson enjoys spending time with her dog along the East coast where she likes to let residents know about NOAA’s digital resources on sea level rise and climate change more broadly. Photo courtesy of Caitlin Simpson.

Why did you take on this role of lead author?

With a background in economics and human dimensions research, I have been working on climate adaptation issues for many decades and have been pushing for more transdisciplinary science that combines social, physical and other sciences with close community collaboration and input. I have thoroughly enjoyed contributing to the assessment of this field of practice and helping to highlight the importance of more transformative adaptation that is inclusive of community input. I will continue to bring the Fifth National Climate Assessment findings into the adaptation and resilience dialogues at NOAA.

Adaptation efforts are occurring in every region of the U.S. but are insufficient in relation to the pace of climate change. Most of these efforts have been small in scale, incremental in approach, and lack sufficient investment and funding. They need to be transformative, meaning that system-wide changes are needed. For any adaptation activity to be effective, it needs to be both just and equitable. This will require addressing the uneven distribution of climate harms and collaborating with local communities.

Government, private industry and civil society are planning for climate adaptation in different ways, and each is focusing on a subset of climate vulnerability, such as disaster resilience, risk and liability, and equity and justice, respectively. They need to address compound and complex events instead of individual hazards such as sea level rise, flooding or heat. Climate services need to include community collaboration and ensure broad access for historically disinvested communities. Adaptation activities need to be coordinated and incorporate multiple voices. Transformative adaptation that involves persistent, novel, and significant changes to institutions, behaviors, values, and/or technology will be key. Finally, more and different funding/investment is needed for adaptation as is better financial and evaluation data to determine what adaptation is occurring, how well it is distributed, and the effectiveness of the adaptation solutions.

Approximately 40% of US states have assessed their climate change risks, and a number of cities and localities have begun to take action. For example, the city of New York recently legislated Climate Resiliency Design Guidelines , which include the city’s guidance to builders for the required height of flood protection needed in design standards; the requirements now use climate projections from the New York City Panel on Climate Change. Members of the NOAA-funded Climate Adaptation Partnerships team in the Northeast participate on this panel and have provided their latest findings on the social and physical ramifications of climate change for the city.

Additional resources:

- Climate change impacts are increasing for Americans

- Meet 5 NOAA authors of the National Climate Assessmen t

- Fifth National Climate Assessment

- NCA5 Webinars (upcoming)

- NCA5 Webinars (past webinars recorded)

- NCA5 Art X Climate Gallery

For more information, please contact Monica Allen, NOAA Communications, at [email protected], 202-379-6693

5 science wins from the 2023 NOAA Science Report

Filling A Data Gap In The Tropical Pacific To Reveal Daily Air-Sea Interactions

Scientists detail research to assess viability and risks of marine cloud brightening

Could drying the stratosphere help cool the planet?

Popup call to action.

A prompt with more information on your call to action.

7 best movies to watch right now before they leave Netflix this month

This is your last chance to watch these top Netflix movies right now before they're gone

Sadly, it's time for more great movies to leave Netflix. Each month, the popular streaming service adds a ton of new movies . But what the Netflix gods give us, they also taketh away, and that means there are some movies you need to watch right now before they're gone from Netflix for good. Or, at least gone for now.

This month, the best Netflix movies leaving the service include the criminally underrated "Jackie Brown" from Quentin Tarantino. We also say goodbye to some of the few good DC comics movies and one of my favorite action movies — nay, one of my favorite movies — of all time. Read on to see the five best movies you need to watch before they leave Netflix in March 2024.

And for more recommendations see our list of the 5 best movies to stream this weekend on Netflix, Prime Video, Hulu and more .

'Wonder Woman' (2017)

One of three genuinely good DC movies leaving this month, "Wonder Woman" stars Gal Gadot as Diana Prince, aka the titular Wonder Woman. The entire movie is technically a flashback, but this origin story in essence starts with Diana's upbringing in Themyscira, the mythical home of the Amazonian race.

But part way through, the arrival of U.S. Air Army Corps pilot Steve Trevor (Chris Pine) shatters Diana's perception of the world. What follows is a well-executed World War I period piece with a compelling villain (David Thewlis) and excellent on-screen chemistry between Gadot and Pine. The sequel to this movie is forgettable, but this is still a must-watch.

Watch on Netflix by March 31

'The Suicide Squad' (2021)

Speaking of forgettable movies, the original "Suicide Squad" from 2016 was forgettable , and that's being generous. The premise of both films? A group of criminals — led by Bloodsport (Idris Elba) in this edition — are assembled into Task Force X by Amanda Waller (Viola Davis). Their mission, which they're forced to accept or tiny bombs explode in their heads, is to infiltrate the island nation of Corto Maltese and to destroy the covert laboratory Jötunheim.

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom’s Guide direct to your inbox.

Upgrade your life with a daily dose of the biggest tech news, lifestyle hacks and our curated analysis. Be the first to know about cutting-edge gadgets and the hottest deals.

But while Margot Robbie and Joel Kinneman reprise their roles as Harley Quinn and Rick Flagg, respectively — yes, this is technically a sequel — you don't need to have any recollection of the original to watch James Gunn's version. And you should definitely watch Gunn's version. It's funny, it's irreverent and it's incredibly violent. It may honestly be my favorite movie of the DC Extended Universe. Come for the many on-screen deaths, stay for Peacemaker's (John Cena) completely unitentional deadpan humor.

'Shazam!' (2019)

To me, "Shazam!" is the "Ant-Man" of the DC Extended Universe. There's nothing groundbreaking about it, but it's well-paced, engaging and frankly underrated. If I was to pick a DC movie I could just start watching no question when it comes on cable, this would be toward the top of the list.

This origin story superhero movie stars Asher Angel as Billy Batson. Billy is a 14-year-old boy who's made his way through the Philadelphia foster care system and is still searching for his birth mother. One day, after defending his foster brother Freddy (Jack Dylan Grazer), he's empowered with "the wisdom of Solomon, the strength of Hercules, the stamina of Atlas, the power of Zeus, the courage of Achilles, and the speed of Mercury" by the wizard Shazam (Djimon Honsou). Now, all Billy needs to do is say the magic word — "Shazam!" — and he becomes a superhero (Zachary Levi) on par with any other.

'Jackie Brown' (1997)

Speaking of underrated, Quentin Tarantino's "Jackie Brown" is underrated . Is it as good as "Reservoir Dogs," "Pulp Fiction," "Kill Bill" or "Inglorious Basterds?" Well ... no, but that doesn't mean it isn't excellent! After all, this is Tarantino we're talking about. He's basically made one movie that wasn't great, and even then "Death Proof" is, at worst, fine.

This homage to 1970s blaxploitation films based on "Rum Punch" by Elmore Leonard (of "Justified" fame), this movie stars Pam Grier as the titular Jackie Brown. Jackie is a flight attendant who smuggles money from Mexico into the U.S. for gun runner Ordell Robbie (Samuel L. Jackson). After being caught by ATF Agent Ray Nicolette (Michael Keaton) and LAPD Detective Mark Dargus (Michael Bowen), they try to recruit her to turn on Robbie. Does that go according to plan? You'll have to watch to find out.

Watch on Netflix by March 30

'John Wick' (2014)

"John Wick" is one of the four greatest movies of all time. Period. This movie is a flawless execution of an action movie and runs just a mere 101 minutes. In that time though, we get incredible world-building and the creation of a now iconic character. There's no filler, and it's more grounded than the three movies that would follow.

The movie stars Keanu Reeves as the titular John Wick, a legendary assassin who has retired and is grieving the loss of his wife Helen (Bridget Moynahan). In her last act from beyond the grave, she sends him a beagle to help him cope with the loss. So when Russian mobster Iosef Tarasov (Alfie Allen) kills the dog and steals Wick's car, you know he's made a fatal mistake. Turns out, so does literally everyone else in this world but Iosef, and now they're cowering in fear as Wick — aka the Baba Yaga (a mythical Slavic spirit) — is out for revenge.

'John Wick: Chapter 2' (2017)

Just because the sequel to "John Wick" isn't quite as perfect as the original film doesn't mean it isn't still excellent. In fact, some may prefer the more fantastical, comic book-like story and world of this movie to the darker, more grounded predecessor. Especially since the fight scenes do admittedly get turned up a level.

In "John Wick: Chapter 2," Reeves reprises as the titular assassin Wick, who tries to remain retired until his old crime world acquaintance Santino D'Antonio (Riccardo Scamarcio) comes back into his life and uses their world's traditions to force John back into the game. After Santino destroys John's house with a grenade launcher, John is left with an impossible choice — get revenge on Santino or fulfill his oath and kill the Italian crime lord's sister (Claudia Gerini).

'John Wick: Chapter 3 - Parabellum' (2019)

If you managed to already watch the first two "John Wick" movies before March 30, then it's time to boot up the third. Or, to be honest, you could just watch it on its own. While groundwork is laid in the previous two movies, "John Wick: Chapter 3 - Parabellum" is still plenty good and plenty entertaining on its own. That said if you do want to watch "John Wick: Chapter 2," you should stop reading now and go do that.

Reeves, of course, returns yet again as the titular assassin John Wick, who is very much unretired after the events of the previous movie. Now, the consequences of his actions against the High Table — rulers of the criminal underworld — have come home to roost at the New York City Continental Hotel. What follows is 131 minutes of pure action movie gold. Make sure to watch this movie before it leaves Netflix.

More from Tom's Guide

- ‘House of the Dragon’ season 2 release date officially revealed

- Netflix's '3 Body Problem' is the best show of 2024 so far

- 9 top new movies to stream this week (March 19-March 25)

Malcolm McMillan is a senior writer for Tom's Guide, covering all the latest in streaming TV shows and movies. That means news, analysis, recommendations, reviews and more for just about anything you can watch, including sports! If it can be seen on a screen, he can write about it. Previously, Malcolm had been a staff writer for Tom's Guide for over a year, with a focus on artificial intelligence (AI), A/V tech and VR headsets.

Before writing for Tom's Guide, Malcolm worked as a fantasy football analyst writing for several sites and also had a brief stint working for Microsoft selling laptops, Xbox products and even the ill-fated Windows phone. He is passionate about video games and sports, though both cause him to yell at the TV frequently. He proudly sports many tattoos, including an Arsenal tattoo, in honor of the team that causes him to yell at the TV the most.

New on Netflix in April 2024 — all the new shows and movies to watch

Netflix just announced the dumbest true crime doc yet

Apple just quietly added Qi2 fast-charging to the iPhone 12 — how to get it

Most Popular

By Ryan Morrison March 28, 2024

By Dave Meikleham March 28, 2024

By Dan Bracaglia March 28, 2024

By Brittany Vincent March 28, 2024

By Rory Mellon March 28, 2024

By Kate Kozuch March 28, 2024

By Alyse Stanley March 28, 2024

By Don Reisinger March 27, 2024

By Josh Bell March 27, 2024

By Josh Render March 27, 2024

By Bill Borrows March 27, 2024

- 2 Hurry! 15% off Spring Sale at eBay ends soon — here's the 11 deals I'd buy

- 3 Google Gemini Nano AI is coming to Pixel 8 — here's the new features

- 4 I just had a conversation with an empathic AI chatbot — and it creeped me out

- 5 New Xbox Series X appears to have leaked — and it comes with a key improvement and a refreshed look

- 2 New Darcula phishing service using iMessage to target iPhone users — how to stay safe

- 3 Florence Pugh shares a first look at MCU’s ‘Thunderbolts’ movie

- 4 Epic Best Buy deal: How to get a free 65-inch Samsung TV right now

- 5 Yes, I’m still shopping spring sales—here are the 7 best deals starting at just $19

Fortnite: Best Chapter 5 Season 2 Landing Spots

- Charon's Crossing offers beginner players plenty of loot and easy access to rotating to other POIs for quick engagements.

- Summit Temple on the edge of the map provides high rarity loot and natural resources while linking to nearby POIs for rotation.

- Research Rock in the corner of the map is underrated but a goldmine for loot with 22 chests and farming opportunities.

Fortnite ’s Chapter 5 Season 2 is in full swing, and players are excited to explore the Greek mythology-inspired map. The map is filled with secret corners, cabins, and spots awaiting a player’s discovery. While all these locations have valuable items players can loot, some have more potential than others. This makes picking the best landing spot crucial to surviving the match and claiming a Victory Royale. Players who want to excel should pick locations on the map that suit individual playstyles while providing solid loot.

Fortnite: All Chapter 5 Season 2 Battle Pass Skins

The best landing spots in Fortnite have sufficient loot spawn, are out of the way, and are close to POIs (points of interest). Since there’s no shortage of fantastic landing spots, picking the ideal locations boils down to the player’s preferences. Here’s a list of the best landing spots in Chapter 5 Season 2.

Charon’s Crossing

Optimal location with multiple loot routes.

Charon’s Crossing is located in the Underworld biome, and it's a lowkey landing spot with a good amount of loot. Players can find up to five chests in this location with reliable weapons and shields. The beauty of Charon’s Crossing is that it’s close to other high POIs like Grim’s Gate. So, players can drop, loot chests, and rotate to these POIs quickly and easily .

Charon’s Crossing is ideal for beginner Fortnite players who want a chill landing spot where they can grab sufficient loot. It’s not too contested and is right next to the water, which players can use to get more loot, activate the Underworld Dash, and rotate.

Summit Temple

A good amount of valuable loot and natural resources.