- Our Mission

What Does the Research Say About Testing?

There’s too much testing in schools, most teachers agree, but well-designed classroom tests and quizzes can improve student recall and retention.

For many teachers, the image of students sitting in silence filling out bubbles, computing mathematical equations, or writing timed essays causes an intensely negative reaction.

Since the passage of the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) in 2002 and its 2015 update, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), every third through eighth grader in U.S. public schools now takes tests calibrated to state standards, with the aggregate results made public. In a study of the nation’s largest urban school districts , students took an average of 112 standardized tests between pre-K and grade 12.

This annual testing ritual can take time from genuine learning, say many educators , and puts pressure on the least advantaged districts to focus on test prep—not to mention adding airless, stultifying hours of proctoring to teachers’ lives. “Tests don’t explicitly teach anything. Teachers do,” writes Jose Vilson , a middle school math teacher in New York City. Instead of standardized tests, students “should have tests created by teachers with the goal of learning more about the students’ abilities and interests,” echoes Meena Negandhi, math coordinator at the French American Academy in Jersey City, New Jersey.

The pushback on high-stakes testing has also accelerated a national conversation about how students truly learn and retain information. Over the past decade and a half, educators have been moving away from traditional testing —particularly multiple choice tests—and turning to hands-on projects and competency-based assessments that focus on goals such as critical thinking and mastery rather than rote memorization.

But educators shouldn’t give up on traditional classroom tests so quickly. Research has found that tests can be valuable tools to help students learn , if designed and administered with format, timing, and content in mind—and a clear purpose to improve student learning.

Not All Tests Are Bad

One of the most useful kinds of tests are the least time-consuming: quick, easy practice quizzes on recently taught content. Tests can be especially beneficial if they are given frequently and provide near-immediate feedback to help students improve. This retrieval practice can be as simple as asking students to write down two to four facts from the prior day or giving them a brief quiz on a previous class lesson.

Retrieval practice works because it helps students retain information in a better way than simply studying material, according to research . While reviewing concepts can help students become more familiar with a topic, information is quickly forgotten without more active learning strategies like frequent practice quizzes.

But to reduce anxiety and stereotype threat—the fear of conforming to a negative stereotype about a group that one belongs to—retrieval-type practice tests also need to be low-stakes (with minor to no grades) and administered up to three times before a final summative effort to be most effective.

Timing also matters. Students are able to do fine on high-stakes assessment tests if they take them shortly after they study. But a week or more after studying, students retain much less information and will do much worse on major assessments—especially if they’ve had no practice tests in between.

A 2006 study found that students who had brief retrieval tests before a high-stakes test remembered 60 percent of material, while those who only studied remembered 40 percent. Additionally, in a 2009 study , eighth graders who took a practice test halfway through the year remembered 10 percent more facts on a U.S. history final at the end of the year than peers who studied but took no practice test.

Short, low-stakes tests also help teachers gauge how well students understand the material and what they need to reteach. This is effective when tests are formative —that is, designed for immediate feedback so that students and teachers can see students’ areas of strength and weakness and address areas for growth. Summative tests, such as a final exam that measures how much was learned but offers no opportunities for a student to improve, have been found to be less effective.

Testing Format Matters

Teachers should tread carefully with test design, however, as not all tests help students retain information. Though multiple choice tests are relatively easy to create, they can contain misleading answer choices—that are either ambiguous or vague—or offer the infamous all-, some-, or none-of-the-above choices, which tend to encourage guessing.

While educators often rely on open-ended questions, such short-answer questions, because they seem to offer a genuine window into student thinking, research shows that there is no difference between multiple choice and constructed response questions in terms of demonstrating what students have learned.

In the end, well-constructed multiple choice tests , with clear questions and plausible answers (and no all- or none-of-the-above choices), can be a useful way to assess students’ understanding of material, particularly if the answers are quickly reviewed by the teacher.

All students do not do equally well on multiple choice tests, however. Girls tend to do less well than boys and perform better on questions with open-ended answers , according to a 2018 study by Stanford University’s Sean Reardon, which found that test format alone accounts for 25 percent of the gender difference in performance in both reading and math. Researchers hypothesize that one explanation for the gender difference on high-stakes tests is risk aversion, meaning girls tend to guess less .

Giving more time for fewer, more complex or richer testing questions can also increase performance, in part because it reduces anxiety. Research shows that simply introducing a time limit on a test can cause students to experience stress, so instead of emphasizing speed, teachers should encourage students to think deeply about the problems they’re solving.

Setting the Right Testing Conditions

Test achievement often reflects outside conditions, and how students do on tests can be shifted substantially by comments they hear and what they receive as feedback from teachers.

When teachers tell disadvantaged high school students that an upcoming assessment may be a challenge and that challenge helps the brain grow, students persist more, leading to higher grades, according to 2015 research from Stanford professor David Paunesku. Conversely, simply saying that some students are good at a task without including a growth-mindset message or the explanation that it’s because they are smart harms children’s performance —even when the task is as simple as drawing shapes.

Also harmful to student motivation are data walls displaying student scores or assessments. While data walls might be useful for educators, a 2014 study found that displaying them in classrooms led students to compare status rather than improve work.

The most positive impact on testing comes from peer or instructor comments that give the student the ability to revise or correct. For example, questions like , “Can you tell me more about what you mean?” or “Can you find evidence for that?” can encourage students to improve engagement with their work. Perhaps not surprisingly, students do well when given multiple chances to learn and improve—and when they’re encouraged to believe that they can.

Created by the Great Schools Partnership , the GLOSSARY OF EDUCATION REFORM is a comprehensive online resource that describes widely used school-improvement terms, concepts, and strategies for journalists, parents, and community members. | Learn more »

Summative Assessment

Summative assessments are used to evaluate student learning, skill acquisition, and academic achievement at the conclusion of a defined instructional period—typically at the end of a project, unit, course, semester, program, or school year. Generally speaking, summative assessments are defined by three major criteria:

- The tests, assignments, or projects are used to determine whether students have learned what they were expected to learn. In other words, what makes an assessment “summative” is not the design of the test, assignment, or self-evaluation, per se, but the way it is used—i.e., to determine whether and to what degree students have learned the material they have been taught.

- Summative assessments are given at the conclusion of a specific instructional period, and therefore they are generally evaluative, rather than diagnostic—i.e., they are more appropriately used to determine learning progress and achievement, evaluate the effectiveness of educational programs, measure progress toward improvement goals, or make course-placement decisions, among other possible applications.

- Summative-assessment results are often recorded as scores or grades that are then factored into a student’s permanent academic record, whether they end up as letter grades on a report card or test scores used in the college-admissions process. While summative assessments are typically a major component of the grading process in most districts, schools, and courses, not all assessments considered to be summative are graded.

Summative assessments are commonly contrasted with formative assessments , which collect detailed information that educators can use to improve instruction and student learning while it’s happening. In other words, formative assessments are often said to be for learning, while summative assessments are of learning. Or as assessment expert Paul Black put it, “When the cook tastes the soup, that’s formative assessment. When the customer tastes the soup, that’s summative assessment.” It should be noted, however, that the distinction between formative and summative is often fuzzy in practice, and educators may have divergent interpretations and opinions on the subject.

Some of the most well-known and widely discussed examples of summative assessments are the standardized tests administered by states and testing organizations, usually in math, reading, writing, and science. Other examples of summative assessments include:

- End-of-unit or chapter tests.

- End-of-term or semester tests.

- Standardized tests that are used to for the purposes of school accountability, college admissions (e.g., the SAT or ACT), or end-of-course evaluation (e.g., Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate exams).

- Culminating demonstrations of learning or other forms of “performance assessment,” such as portfolios of student work that are collected over time and evaluated by teachers or capstone projects that students work on over extended periods of time and that they present and defend at the conclusion of a school year or their high school education.

While most summative assessments are given at the conclusion of an instructional period, some summative assessments can still be used diagnostically. For example, the growing availability of student data, made possible by online grading systems and databases, can give teachers access to assessment results from previous years or other courses. By reviewing this data, teachers may be able to identify students more likely to struggle academically in certain subject areas or with certain concepts. In addition, students may be allowed to take some summative tests multiple times, and teachers might use the results to help prepare students for future administrations of the test.

It should also be noted that districts and schools may use “interim” or “benchmark” tests to monitor the academic progress of students and determine whether they are on track to mastering the material that will be evaluated on end-of-course tests or standardized tests. Some educators consider interim tests to be formative, since they are often used diagnostically to inform instructional modifications, but others may consider them to be summative. There is ongoing debate in the education community about this distinction, and interim assessments may defined differently from place to place. See formative assessment for a more detailed discussion.

While educators have arguably been using “summative assessments” in various forms since the invention of schools and teaching, summative assessments have in recent decades become components of larger school-improvement efforts. As they always have, summative assessments can help teachers determine whether students are making adequate academic progress or meeting expected learning standards, and results may be used to inform modifications to instructional techniques, lesson designs, or teaching materials the next time a course, unit, or lesson is taught. Yet perhaps the biggest changes in the use of summative assessments have resulted from state and federal policies aimed at improving public education—specifically, standardized high-stakes tests used to make important decisions about schools, teachers, and students.

While there is little disagreement among educators about the need for or utility of summative assessments, debates and disagreements tend to center on issues of fairness and effectiveness, especially when summative-assessment results are used for high-stakes purposes. In these cases, educators, experts, reformers, policy makers, and others may debate whether assessments are being designed and used appropriately, or whether high-stakes tests are either beneficial or harmful to the educational process. For more detailed discussions of these issues, see high-stakes test , measurement error , test accommodations , test bias , score inflation , standardized test , and value-added measures .

Alphabetical Search

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Conceptual analysis article, the past, present and future of educational assessment: a transdisciplinary perspective.

- 1 Department of Applied Educational Sciences, Umeå Universitet, Umeå, Sweden

- 2 Faculty of Education and Social Work, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

To see the horizon of educational assessment, a history of how assessment has been used and analysed from the earliest records, through the 20th century, and into contemporary times is deployed. Since paper-and-pencil assessments validity and integrity of candidate achievement has mattered. Assessments have relied on expert judgment. With the massification of education, formal group-administered testing was implemented for qualifications and selection. Statistical methods for scoring tests (classical test theory and item response theory) were developed. With personal computing, tests are delivered on-screen and through the web with adaptive scoring based on student performance. Tests give an ever-increasing verisimilitude of real-world processes, and analysts are creating understanding of the processes test-takers use. Unfortunately testing has neglected the complicating psychological, cultural, and contextual factors related to test-taker psychology. Computer testing neglects school curriculum and classroom contexts, where most education takes place and where insights are needed by both teachers and learners. Unfortunately, the complex and dynamic processes of classrooms are extremely difficult to model mathematically and so remain largely outside the algorithms of psychometrics. This means that technology, data, and psychometrics have become increasingly isolated from curriculum, classrooms, teaching, and the psychology of instruction and learning. While there may be some integration of these disciplines within computer-based testing, this is still a long step from where classroom assessment happens. For a long time, educational, social, and cultural psychology related to learning and instruction have been neglected in testing. We are now on the cusp of significant and substantial development in educational assessment as greater emphasis on the psychology of assessment is brought into the world of testing. Herein lies the future for our field: integration of psychological theory and research with statistics and technology to understand processes that work for learning, identify how well students have learned, and what further teaching and learning is needed. The future requires greater efforts by psychometricians, testers, data analysts, and technologists to develop solutions that work in the pressure of living classrooms and that support valid and reliable assessment.

Introduction

In looking to the horizon of educational assessment, I would like to take a broad chronological view of where we have come from, where we are now, and what the horizons are. Educational assessment plays a vital role in the quality of student learning experiences, teacher instructional activities, and evaluation of curriculum, school quality, and system performance. Assessments act as a lever for both formative improvement of teaching and learning and summative accountability evaluation of teachers, schools, and administration. Because it is so powerful, a nuanced understanding of its history, current status, and future possibilities seems a useful exercise. In this overview I begin with a brief historical journey from assessments past through the last 3000 years and into the future that is already taking place in various locations and contexts.

Early records of the Chinese Imperial examination system can be found dating some 2,500 to 3,000 years ago ( China Civilisation Centre, 2007 ). That system was used to identify and reward talent wherever it could be found in the sprawling empire of China. Rather than rely solely on recommendations, bribery, or nepotism, it was designed to meritocratically locate students with high levels of literacy and memory competencies to operate the Emperor’s bureaucracy of command and control of a massive population. To achieve those goals, the system implemented standardised tasks (e.g., completing an essay according to Confucian principles) under invigilated circumstances to ensure integrity and comparability of performances ( Feng, 1995 ). The system had a graduated series of increasingly more complex and demanding tests until at the final examination no one could be awarded the highest grade because it was reserved for the Emperor alone. Part of the rationale for this extensive technology related to the consequences attached to selection; not only did successful candidates receive jobs with substantial economic benefits, but they were also recognised publicly on examination lists and by the right to wear specific colours or badges that signified the level of examination the candidate had passed. Unsurprisingly, given the immense prestige and possibility of social advancement through scholarship, there was an industry of preparing cheat materials (e.g., miniature books that replicated Confucian classics) and catching cheats (e.g., ranks of invigilators in high chairs overlooking desks at which candidates worked; Elman, 2013 ).

In contrast, as described by Encyclopedia Brittanica (2010a) , European educational assessment grew out of the literary and oratorical remains of the Roman empire such as schools of grammarians and rhetoricians. At the same time, schools were formed in the various cathedrals, monasteries (especially, the Benedictine monasteries), and episcopal schools throughout Europe. Under Charlemagne, church priests were required to master Latin so that they could understand scripture correctly, leading to more advanced religious and academic training. As European society developed in the early Renaissance, schools were opened under the authority of a bishop or cathedral officer or even from secular guilds to those deemed sufficiently competent to teach. Students and teachers at these schools were given certain protection and rights to ensure safe travel and free thinking. European universities from the 1100s adopted many of the clerical practices of reading important texts and scholars evaluating the quality of learning by student performance in oral disputes, debates, and arguments relative to the judgement of higher ranked experts. The subsequent centuries added written tasks and performances to the oral disputes as a way of judging the quality of learning outcomes. Nonetheless, assessment was based, as the Chinese Imperial system, on the expertise and judgment of more senior scholars or bureaucrats.

These mechanisms were put in place to meet the needs of society or religion for literate and numerate bureaucrats, thinkers, and scholars. The resource of further education, or even basic education, was generally rationed and limited. Standardised assessments, even if that were only the protocol rather than the task or the scoring, were carried out to select candidates on a relatively meritocratic basis. Families and students engaged in these processes because educational success gave hope of escape from lives of poverty and hard labour. Consequently, assessment was fundamentally a summative judgement of the student’s abilities, schooling was preparation for the final examination, and assessments during the schooling process were but mimicry of a final assessment.

With the expansion of schooling and higher education through the 1800s, more efficient methods were sought to the workload surrounding hearing memorized recitations ( Encyclopedia Brittanica, 2010b ). This led to the imposition of leaving examinations as an entry requirement to learned professions (e.g., being a teacher), the civil service, and university studies. As more and more students attended universities in the 1800s, more efficient ways collecting information were established, most especially the essay examination and the practice of answering in writing by oneself without aids. This tradition can still be seen in ordered rows of desks in examination halls as students complete written exam papers under scrutiny and time pressure.

The 20th century

By the early 1900s, however, it became apparent that the scoring of these important intellectual exercises was highly problematic. Markers did not agree with each other nor were they consistent within themselves across items or tasks and over time so that their scores varied for the same work. Consequently, early in the 20th century, multiple-choice question tests were developed so that there would be consistency in scoring and efficiency in administration ( Croft and Beard, 2022 ). It is also worth noting that considerable cost and time efficiencies were obtained through using multiple-choice test methods. This aspect led, throughout the century, to increasingly massive use of standardised machine scoreable tests for university entrance, graduate school selection, and even school evaluation. The mechanism of scoring items dichotomously (i.e., right or wrong), within classical test theory statistical modelling, resulted in easy and familiar numbers (e.g., mean, standard deviation, reliability, and standard error of measurement; Clauser, 2022 ).

As the 20th century progressed, the concepts of validity have grown increasingly expansive, and the methods of validation have become increasingly complex and multi-faceted to ensure validity of scores and their interpretation ( Zumbo and Chan, 2014 ). These included scale reliability, factor analysis, item response theory, equating, norming, and standard setting, among others ( Kline, 2020 ). It is worth noting here that statistical methods for test score analysis grew out of the early stages of the discipline of psychology. As psychometric methods became increasingly complex, the world of educational testing began to look much more like the world of statistics. Indeed, Cronbach (1954) noted that the world of psychometrics (i.e., statistical measurement of psychological phenomena) was losing contact with the world of psychology which was the most likely user of psychometric method and research. Interestingly, the world of education makes extensive use of assessment, but few educators are adept at the statistical methods necessary to evaluate their own tests, let alone those from central authorities. Indeed, few teachers are taught statistical test analysis techniques, even fewer understand them, and almost none make use of them.

Of course, assessment is not just a scored task or set of questions. It is legitimately an attempt to operationalize a sample of a construct or content or curriculum domain. The challenge for assessment lies in the conundrum that the material that is easy to test and score tends to be the material that is the least demanding or valuable in any domain. Learning objectives for K-12 schooling, let alone higher education, expect students to go beyond remembering, recalling, regurgitating lists of terminology, facts, or pieces of data. While recall of data pieces is necessary for deep processing, recall of those details is not sufficient. Students need to exhibit complex thinking, problem-solving, creativity, and analysis and synthesis. Assessment of such skills is extremely complex and difficult to achieve.

However, with the need to demonstrate that teachers are effective and that schools are achieving society’s goals and purposes it becomes easy to reduce the valued objectives of society to that which can be incorporated efficiently into a standardised test. Hence, in many societies the high-stakes test becomes the curriculum. If we could be sure that what was on the test is what society really wanted, this would not be such a bad thing; what Resnick and Resnick (1989) called measurement driven reform. However, research over extensive periods since the middle of the 20 th century has shown that much of what we test does not add value to the learning of students ( Nichols and Harris, 2016 ).

An important development in the middle of the 20th century was Scriven’s (1967) work on developing the principles and philosophy of evaluation. A powerful aspect to evaluation that he identified was the distinction between formative evaluation taking place early enough in a process to make differences to the end points of the process and summative evaluation which determined the amount and quality or merit of what the process produced. The idea of formative evaluation was quickly adapted into education as a way of describing assessments that teachers used within classrooms to identify which children needed to be taught what material next ( Bloom et al., 1971 ). This contrasted nicely with high-stakes end-of-unit, end-of-course, or end-of-year formal examinations that summatively judged the quality of student achievement and learning. While assessment as psychometrically validated tests and examinations historically focused on the summative experience, Scriven’s formative evaluation led to using assessment processes early in the educational course of events to inform learners as to what they needed to learn and instructors as to what they needed to teach.

Nonetheless, since the late 1980s (largely thanks to Sadler, 1989 ) the distinction between summative and formative transmogrified from timing to one of type. Formative assessments began to be only those which were not formal tests but were rather informal interactions in classrooms. This perspective was extended by the UK Assessment Reform Group (2002) which promulgated basic principles of formative assessment around the world. Those classroom assessment practices focused much more on what could be seen as classroom teaching practices ( Brown, 2013 , 2019 , 2020a ). Instead of testing, teachers interacted with students on-the-fly, in-the-moment of the classroom through questions and feedback that aimed to help students move towards the intended learning outcomes established at the beginning of lessons or courses. Thus, assessment for learning has become a child-friendly approach ( Stobart, 2006 ) to involving learners in their learning and developing rich meaningful outcomes without the onerous pressure of testing. Much of the power of this approach was that it came as an alternative to the national curriculum of England and Wales that incorporated high-stakes standardised assessment tasks of children at ages 7, 9, 11, and 14 (i.e., Key Stages 1 to 4; Wherrett, 2004 ).

In line with increasing access to schooling worldwide throughout the 20 th century, there is concern that success on high-consequence, summative tests simply reinforced pre-existing social status and hierarchy ( Bourdieu, 1974 ). This position argues tests are not neutral but rather tools of elitism ( Gipps, 1994 ). Unfortunately, when assessments have significant consequences, much higher proportions of disadvantaged students (e.g., minority students, new speakers of the language-medium of assessment, special needs students, those with reading difficulties, etc.) do not experience such benefits ( Brown, 2008 ). This was a factor in the development of using assessment high-quality formative assessment to accelerate the learning progression of disadvantaged students. Nonetheless, differences in group outcomes do not always mean tests are the problem; group score differences can point out that there is sociocultural bias in the provision of educational resources in the school system ( Stobart, 2005 ). This would be rationale for system monitoring assessments, such as Hong Kong’s Territory Wide System Assessment, 1 the United States’ National Assessment of Educational Progress, 2 or Australia’s National Assessment Program Literacy and Numeracy. 3 The challenge is how to monitor a system without blaming those who have been let down by it.

Key Stage tests were put in place, not only to evaluate student learning, but also to assure the public that teachers and schools were achieving important goals of education. This use of assessment put focus on accountability, not for the student, but for the school and teacher ( Nichols and Harris, 2016 ). The decision to use tests of student learning to evaluate schools and teachers was mimicked, especially in the United States, in various state accountability tests, the No Child Left Behind legislation, and even such innovative programs of assessment as Race to the Top and PARCC. It should be noted that the use of standardised tests to evaluate teachers and schools is truly a global phenomenon, not restricted to the UK and the USA ( Lingard and Lewis, 2016 ). In this context, testing became a summative evaluation of teachers and school leaders to demonstrate school effectiveness and meet accountability requirements.

The current situation is that assessment is perceived quite differently by experts in different disciplines. Psychometricians tend to define assessment in terms of statistical modelling of test scores. Psychologists use assessments for diagnostic description of client strengths or needs. Within schooling, leaders tend to perceive assessment as jurisdiction or state-mandated school accountability testing, while teachers focus on assessment as interactive, on-the-fly experiences with their students, and parents ( Buckendahl, 2016 ; Harris and Brown, 2016 ) understand assessment as test scores and grades. The world of psychology has become separated from the worlds of classroom teaching, curriculum, psychometrics and statistics, and assessment technologies.

This brief history bringing us into early 21 st century shows that educational assessment is informed by multiple disciplines which often fail to talk with or even to each other. Statistical analysis of testing has become separated from psychology and education, psychology is separated from curriculum, teaching is separated from testing, and testing is separated from learning. Hence, we enter the present with many important facets that inform effective use of educational assessment siloed from one another.

Now and next

Currently the world of educational statistics has become engrossed in the large-scale data available through online testing and online learning behaviours. The world of computational psychometrics seeks to move educational testing statistics into the dynamic analysis of big data with machine learning and artificial intelligence algorithms potentially creating a black box of sophisticated statistical models (e.g., neural networks) which learners, teachers, administrators, and citizens cannot understand ( von Davier et al., 2019 ). The introduction of computing technologies means that automation of item generation ( Gierl and Lai, 2016 ) and scoring of performances ( Shin et al., 2021 ) is possible, along with customisation of test content according to test-taker performance ( Linden and Glas, 2000 ). The Covid-19 pandemic has rapidly inserted online and distance testing as a commonplace practice with concerns raised about how technology is used to assure the integrity of student performance ( Dawson, 2021 ).

The ecology of the classroom is not the same as that of a computerised test. This is especially notable when the consequence of a test (regardless of medium) has little relevance to a student ( Wise and Smith, 2016 ). Performance on international large-scale assessments (e.g., PISA, TIMSS) may matter to government officials ( Teltemann and Klieme, 2016 ) but these tests have little value for individual learners. Nonetheless, governmental responses to PISA or TIMSS results may create policies and initiatives that have trickle-down effect on schools and students ( Zumbo and Forer, 2011 ). Consequently, depending on the educational and cultural environment, test-taking motivation on tests that have consequences for the state can be similar to a test with personal consequence in East Asia ( Zhao et al., 2020 ), but much lower in a western democracy ( Zhao et al., 2022 ). Hence, without surety that in any educational test learners are giving full effort ( Thorndike, 1924 ), the information generated by psychometric analysis is likely to be invalid. Fortunately, under computer testing conditions, it is now possible to monitor reduced or wavering effort during an actual test event and provide support to such a student through a supervising proctor ( Wise, 2019 ), though this feature is not widely prevalent.

Online or remote teaching, learning, and assessment have become a reality for many teachers and students, especially in light of our educational responses to the Covid-19 pandemic. Clearly, some families appreciate this because their children can progress rapidly, unencumbered by the teacher or classmates. For such families, continuing with digital schooling would be seen as a positive future. However, reliance on a computer interface as the sole means of assessment or teaching may dehumanise the very human experience of learning and teaching. As Asimov (1954) described in his short story of a future world in which children are taught individually by machines, Margie imagined what it must have been like to go to school with other children:

Margie …was thinking about the old schools they had when her grandfather's grandfather was a little boy. All the kids from the whole neighborhood came, laughing and shouting in the schoolyard, sitting together in the schoolroom, going home together at the end of the day. They learned the same things so they could help one another on the homework and talk about it.

And the teachers were people...

The mechanical teacher was flashing on the screen: "When we add the fractions ½ and ¼ -"

Margie was thinking about how the kids must have loved it in the old days. She was thinking about the fun they had.

As Brown (2020b) has argued the option of a de-schooled society through computer-based teaching, learning, and assessment is deeply unattractive on the grounds that it is likely to be socially unjust. The human experience of schooling matters to the development of humans. We learn through instruction ( Bloom, 1976 ), culturally located experiences ( Cole et al., 1971 ), inter-personal interaction with peers and adults ( Vygotsky, 1978 ; Rogoff, 1991 ), and biogenetic factors ( Inhelder and Piaget, 1958 ). Schooling gives us access to environments in which these multiple processes contribute to the kinds of citizens we want. Hence, we need confidence in the power of shared schooling to do more than increase the speed by which children acquire knowledge and learning; it helps us be more human.

This dilemma echoes the tension between in vitro and in vivo biological research. Within the controlled environment of a test tube (vitro) organisms do not necessarily behave the same way as they do when released into the complexity of human biology ( Autoimmunity Research Foundation, 2012 ). This analogy has been applied to educational assessment ( Zumbo, 2015 ) indicating that how students perform in a computer-mediated test may not have validity for how students perform in classroom interactions or in-person environments.

The complexity of human psychology is captured in Hattie’s (2004) ROPE model which posits that the various aspects of human motivation, belief, strategy, and values interact as threads spun into a rope. This means it is hard to analytically separate the various components and identify aspects that individually explain learning outcomes. Indeed, Marsh et al. (2006) showed that of the many self-concept and control beliefs used to predict performance on the PISA tests, almost all variables have relations to achievement less than r = 0.35. Instead, interactions among motivation, beliefs about learning, intelligence, assessment, the self, and attitudes with and toward others, subjects, and behaviours all matter to performance. Aspects that create growth-oriented pathways ( Boekaerts and Niemivirta, 2000 ) and strategies include inter alia mastery goals ( Deci and Ryan, 2000 ), deep learning ( Biggs et al., 2001 ) beliefs, malleable intelligence ( Duckworth et al., 2011 ) beliefs, improvement-oriented beliefs about assessment ( Brown, 2011 ), internal, controllable attributes ( Weiner, 1985 ), effort ( Wise and DeMars, 2005 ), avoiding dishonesty ( Murdock et al., 2016 ), trusting one’s peers ( Panadero, 2016 ), and realism in evaluating one’s own work ( Brown and Harris, 2014 ). All these adaptive aspects of learning stand in contrast to deactivating and maladaptive beliefs, strategies, and attitudes that serve to protect the ego and undermine learning. What this tells us that psychological research matters to understanding the results of assessment and that no one single psychological construct is sufficient to explain very much of the variance in student achievement. However, it seems we are as yet unable to identify which specific processes matter most to better performance for all students across the ability spectrum, given that almost all the constructs that have been reported in educational psychology seem to have a positive contribution to better performance. Here is the challenge for educational psychology within an assessment setting —which constructs are most important and effectual before, during, and after any assessment process ( Mcmillan, 2016 ) and how should they be operationalised.

A current enthusiasm is to use ‘big data’ from computer-based assessments to examine in more detail how students carry out the process of responding to tasks. Many large-scale testing programs through computer testing collect, utilize, and report on test-taker engagement as part of their process data collection (e.g., the United States National Assessment of Educational Progress 4 ). These test systems provide data about what options were clicked on, in what order, what pages were viewed, and the timings of these actions. Several challenges to using big data in educational assessment exist. First, computerised assessments need to capture the processes and products we care about. That means we need a clear theoretical model of the underlying cognitive mechanisms or processes that generate the process data itself ( Zumbo et al., in press ). Second, we need to be reminded that data do not explain themselves; theory and insight about process are needed to understand data ( Pearl and Mackenzie, 2018 ). Examination of log files can give some insight into effective vs. ineffective strategies, once the data were analysed using theory to create a model of how a problem should be done ( Greiff et al., 2015 ). Access to data logs that show effort and persistence on a difficult task can reveal that, despite failure to successfully resolve a problem, such persistence is related to overall performance ( Lundgren and Eklöf, 2020 ). But data by itself will not tell us how and why students are successful and what instruction might need to do to encourage students to use the scientific method of manipulating one variable at a time or not giving up quickly.

Psychometric analyses of assessments can only statistically model item difficulty, item discrimination, and item chance parameters to estimate person ability ( Embretson and Reise, 2000 ). None of the other psychological features of how learners relate to themselves and their environment are included in score estimation. In real classroom contexts, teachers make their best efforts to account for individual motivation, affect, and cognition to provide appropriate instruction, feedback, support, and questioning. However, the nature of these factors varies across time (cohorts), locations (cultures and societies), policy priorities for schooling and assessment, and family values ( Brown and Harris, 2009 ). This means that what constitutes a useful assessment to inform instruction in a classroom context (i.e., identify to the teacher who needs to be taught what next) needs to constantly evolve and be incredibly sensitive to individual and contextual factors. This is difficult if we keep psychology, curriculum, psychometrics, and technology in separate silos. It seems highly desirable that these different disciplines interact, but it is not guaranteed that the technology for psychometric testing developments will cross-pollinate with classroom contexts where teachers have to relate to and monitor student learning across all important curricular domains.

It is common to treat what happens in the minds and emotions of students when they are assessed as a kind of ‘black box’ implying that the processes are opaque or unknowable. This is an approach I have taken previously in examining what students do when asked to self-assess ( Yan and Brown, 2017 ). However, the meaning of a black box is quite different in engineering. In aeronautics, the essential constructs related to flight (e.g., engine power, aileron settings, pitch and yaw positions, etc.) are known very deeply, otherwise flight would not happen. The black box in an airplane records the values of those important variables and the only thing unknown (i.e., black) is what the values were at the point of interest. If we are to continue to use this metaphor as a way of understanding what happens when students are assessed or assess, then we need to agree on what the essential constructs are that underlie learning and achievement. Our current situation seems to be satisfied with everything is correlated and everything matters. It may be that data science will help us sort through the chaff for the wheat provided we design and implement sensors appropriate to the constructs we consider hypothetically most important. It may be that measuring timing of mouse clicks and eye tracking do connect to important underlying mechanisms, but at this stage data science in testing seems largely a case of crunch the ‘easy to get’ numbers and hope that the data mean something.

To address this concern, we need to develop for education’s sake, assessments that have strong alignment with curricular ambitions and values and which have applicability to classroom contexts and processes ( Bennett, 2018 ). This will mean technology that supports what humans must do in schooling rather than replace them with teaching/testing machines. Fortunately, some examples of assessment technology for learning do exist. One supportive technology is PeerWise ( Denny et al., 2008 ; Hancock et al., 2018 ) in which students create course related multiple-choice questions and use them as a self-testing learning strategy. A school-based technology is the e-asTTle computer assessment system that produces a suite of diagnostic reports to support teachers’ planning and teaching in response to what the system indicated students need to be taught ( Hattie and Brown, 2008 ; Brown and Hattie, 2012 ; Brown et al., 2018 ). What these technologies do is support rather than supplant the work that teachers and learners need to do to know what they need to study or teach and to monitor their progress. Most importantly they are well-connected to what students must learn and what teachers are teaching. Other detailed work uses organised learning models or dynamic learning maps to mark out routes for learners and teachers using cognitive and curriculum insights with psychometric tools for measuring status and progress ( Kingston et al., 2022 ). The work done by Wise (2019) shows that it is possible in a computer assisted testing environment to monitor student effort based on their speed of responding and give prompts that support greater effort and less speed.

Assessment needs to exploit more deeply the insights educational psychology has given us into human behavior, attitudes, inter- and intra-personal relations, emotions, and so on. This was called for some 20 years ago ( National Research Council, 2001 ) but the underlying disciplines that inform this integration seem to have grown away from each other. Nonetheless, the examples given above suggest that the gaps can be closed. But assessments still do not seem to consider and respond to these psychological determinants of achievement. Teachers have the capability of integrating curriculum, testing, psychology, and data at a superficial level but with some considerable margin of error ( Meissel et al., 2017 ). To overcome their own error, teachers need technologies that support them in making useful and accurate interpretations of what students need to be taught next that work with them in the classroom. As Bennett (2018) pointed out more technology will happen, but perhaps not more tests on computers. This is the assessment that will help teachers rather than replace them and give us hope for a better future.

Author contributions

GB wrote this manuscript and is solely responsible for its content.

Support for the publication of this paper was received from the Publishing and Scholarly Services of the Umeå University Library.

Acknowledgments

A previous version of this paper was presented as a keynote address to the 2019 biennial meeting of the European Association for Research in Learning and Instruction, with the title Products, Processes, Psychology, and Technology: Quo Vadis Educational Assessment ?

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^ https://www.hkeaa.edu.hk/en/sa_tsa/tsa/

2. ^ https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/

3. ^ https://nap.edu.au/

4. ^ https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/process_data/

Asimov, I. (1954). Oh the fun they had. Fantasy Sci. Fiction 6, 125–127.

Google Scholar

Assessment Reform Group (2002). Assessment for learning: 10 principles Research-based Principles to Guide Classroom Practice Cambridge: Assessment Reform Group.

Autoimmunity Research Foundation. (2012). Differences between in vitro, in vivo, and in silico studies [online]. The Marshall Protocol Knowledge Base. Available at: http://mpkb.org/home/patients/assessing_literature/in_vitro_studies (Accessed November 12, 2015).

Bennett, R. E. (2018). Educational assessment: what to watch in a rapidly changing world. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 37, 7–15. doi: 10.1111/emip.12231

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Biggs, J., Kember, D., and Leung, D. Y. (2001). The revised two-factor study process questionnaire: R-SPQ-2F. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 71, 133–149. doi: 10.1348/000709901158433

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bloom, B. S. (1976). Human Characteristics and School Learning . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Bloom, B., Hastings, J., and Madaus, G. (1971). Handbook on Formative and Summative Evaluation of Student Learning . New York:McGraw Hill.

Boekaerts, M., and Niemivirta, M. (2000). “Self-regulated learning: finding a balance between learning goals and ego-protective goals,” in Handbook of Self-regulation . eds. M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, and M. Zeidner (San Diego, CA: Academic Press).

Bourdieu, P. (1974). “The school as a conservative force: scholastic and cultural inequalities,” in Contemporary Research in the Sociology of Education . ed. J. Eggleston (London: Methuen).

Brown, G. T. L. (2008). Conceptions of Assessment: Understanding what Assessment Means to Teachers and Students . New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Brown, G. T. L. (2011). Self-regulation of assessment beliefs and attitudes: a review of the Students' conceptions of assessment inventory. Educ. Psychol. 31, 731–748. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2011.599836

Brown, G. T. L. (2013). “Assessing assessment for learning: reconsidering the policy and practice,” in Making a Difference in Education and Social Policy . eds. M. East and S. May (Auckland, NZ: Pearson).

Brown, G. T. L. (2019). Is assessment for learning really assessment? Front. Educ. 4:64. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00064

Brown, G. T. L. (2020a). Responding to assessment for learning: a pedagogical method, not assessment. N. Z. Annu. Rev. Educ. 26, 18–28. doi: 10.26686/nzaroe.v26.6854

Brown, G. T. L. (2020b). Schooling beyond COVID-19: an unevenly distributed future. Front. Educ. 5:82. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00082

Brown, G. T. L., and Harris, L. R. (2009). Unintended consequences of using tests to improve learning: how improvement-oriented resources heighten conceptions of assessment as school accountability. J. MultiDisciplinary Eval. 6, 68–91.

Brown, G. T. L., and Harris, L. R. (2014). The future of self-assessment in classroom practice: reframing self-assessment as a core competency. Frontline Learn. Res. 3, 22–30. doi: 10.14786/flr.v2i1.24

Brown, G. T. L., O'leary, T. M., and Hattie, J. A. C. (2018). “Effective reporting for formative assessment: the asTTle case example,” in Score Reporting: Research and Applications . ed. D. Zapata-Rivera (New York: Routledge).

Brown, G. T., and Hattie, J. (2012). “The benefits of regular standardized assessment in childhood education: guiding improved instruction and learning,” in Contemporary Educational Debates in Childhood Education and Development . eds. S. Suggate and E. Reese (New York: Routledge).

Buckendahl, C. W. (2016). “Public perceptions about assessment in education,” in Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment . eds. G. T. L. Brown and L. R. Harris (New York: Routledge).

China Civilisation Centre (2007). China: Five Thousand Years of History and Civilization . Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong Press.

Clauser, B. E. (2022). “A history of classical test theory,” in The History of Educational Measurement: Key Advancements in Theory, Policy, and Practice . eds. B. E. Clauser and M. B. Bunch (New York: Routledge).

Cole, M., Gay, J., Glick, J., and Sharp, D. (1971). The Cultural Context of Learning and Thinking: An Exploration in Experimental Anthropology . New York: Basic Books.

Croft, M., and Beard, J. J. (2022). “Development and evolution of the SAT and ACT,” in The History of Educational Measurement: Key Advancements in Theory, Policy, and Practice . eds. B. E. Clauser and M. B. Bunch (New York: Routledge).

Cronbach, L. J. (1954). Report on a psychometric mission to Clinicia. Psychometrika 19, 263–270. doi: 10.1007/BF02289226

Dawson, P. (2021). Defending Assessment Security in a Digital World: Preventing e-cheating and Supporting Academic Integrity in Higher Education . London: Routledge.

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78.

Denny, P., Hamer, J., Luxton-Reilly, A., and Purchase, H. PeerWise: students sharing their multiple choice questions. ICER '08: Proceedings of the Fourth international Workshop on Computing Education Research; September6–7 (2008). Sydney, Australia, 51-58.

Duckworth, A. L., Quinn, P. D., and Tsukayama, E. (2011). What no child left behind leaves behind: the roles of IQ and self-control in predicting standardized achievement test scores and report card grades. J. Educ. Psychol. 104, 439–451. doi: 10.1037/a0026280

Elman, B. A. (2013). Civil Examinations and Meritocracy in Late IMPERIAL China . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Embretson, S. E., and Reise, S. P. (2000). Item Response Theory for Psychologists . Mahwah: LEA.

Encyclopedia Brittanica (2010a). Europe in the middle ages: the background of early Christian education. Encyclopedia Britannica.

Encyclopedia Brittanica (2010b). Western education in the 19th century. Encyclopedia Britannica.

Feng, Y. (1995). From the imperial examination to the national college entrance examination: the dynamics of political centralism in China's educational enterprise. J. Contemp. China 4, 28–56. doi: 10.1080/10670569508724213

Gierl, M. J., and Lai, H. (2016). A process for reviewing and evaluating generated test items. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 35, 6–20. doi: 10.1111/emip.12129

Gipps, C. V. (1994). Beyond Testing: Towards a Theory of Educational Assessment . London: Falmer Press.

Greiff, S., Wüstenberg, S., and Avvisati, F. (2015). Computer-generated log-file analyses as a window into students' minds? A showcase study based on the PISA 2012 assessment of problem solving. Comput. Educ. 91, 92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2015.10.018

Hancock, D., Hare, N., Denny, P., and Denyer, G. (2018). Improving large class performance and engagement through student-generated question banks. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 46, 306–317. doi: 10.1002/bmb.21119

Harris, L. R., and Brown, G. T. L. (2016). “Assessment and parents,” in Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy And theory . ed. M. A. Peters (Springer: Singapore).

Hattie, J. Models of self-concept that are neither top-down or bottom-up: the rope model of self-concept. 3rd International Biennial Self Research Conference; July, (2004). Berlin, DE.

Hattie, J. A., and Brown, G. T. L. (2008). Technology for school-based assessment and assessment for learning: development principles from New Zealand. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 36, 189–201. doi: 10.2190/ET.36.2.g

Inhelder, B., and Piaget, J. (1958). The Growth of Logical Thinking from Childhood to Adolescence . New York; Basic Books

Kingston, N. M., Alonzo, A. C., Long, H., and Swinburne Romine, R. (2022). Editorial: the use of organized learning models in assessment. Front. Education 7:446. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1009446

Kline, R. B. (2020). “Psychometrics,” in SAGE Research Methods Foundations . eds. P. Atkinson, S. Delamont, A. Cernat, J. W. Sakshaug, and R. A. Williams (London: Sage).

Linden, W. J. V. D., and Glas, G. A. W. (2000). Computerized Adaptive Testing: Theory and Practice . London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Lingard, B., and Lewis, S. (2016). “Globalization of the Anglo-American approach to top-down, test-based educational accountability,” in Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment . eds. G. T. L. Brown and L. R. Harris (New York: Routledge).

Lundgren, E., and Eklöf, H. (2020). Within-item response processes as indicators of test-taking effort and motivation. Educ. Res. Eval. 26, 275–301. doi: 10.1080/13803611.2021.1963940

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K.-T., Artelt, C., Baumert, J., and Peschar, J. L. (2006). OECD's brief self-report measure of educational psychology's most useful affective constructs: cross-cultural, psychometric comparisons across 25 countries. Int. J. Test. 6, 311–360. doi: 10.1207/s15327574ijt0604_1

Mcmillan, J. H. (2016). “Section discussion: student perceptions of assessment,” in Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment . eds. G. T. L. Brown and L. R. Harris (New York: Routledge).

Meissel, K., Meyer, F., Yao, E. S., and Rubie-Davies, C. M. (2017). Subjectivity of teacher judgments: exploring student characteristics that influence teacher judgments of student ability. Teach. Teach. Educ. 65, 48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.02.021

Murdock, T. B., Stephens, J. M., and Groteweil, M. M. (2016). “Student dishonesty in the face of assessment: who, why, and what we can do about it,” in Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in assessment . eds. G. T. L. Brown and L. R. Harris (New York: Routledge).

National Research Council (2001). Knowing what students know: The science and design of educational assessment. The National Academies Press.

Nichols, S. L., and Harris, L. R. (2016). “Accountability assessment’s effects on teachers and schools,” in Handbook of human and Social Conditions in Assessment . eds. G. T. L. Brown and L. R. Harris (New York: Routledge).

Panadero, E. (2016). “Is it safe? Social, interpersonal, and human effects of peer assessment: a review and future directions,” in Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment . eds. G. T. L. Brown and L. R. Harris (New York: Routledge).

Pearl, J., and Mackenzie, D. (2018). The Book of why: The New Science of Cause and Effect . New York: Hachette Book Group.

Resnick, L. B., and Resnick, D. P. (1989). Assessing the Thinking Curriculum: New Tools for Educational Reform . Washington, DC: National Commission on Testing and Public Policy.

Rogoff, B. (1991). “The joint socialization of development by young children and adults,” in Learning to Think: Child Development in Social Context 2 . eds. P. Light, S. Sheldon, and M. Woodhead (London: Routledge).

Sadler, D. R. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instr. Sci. 18, 119–144. doi: 10.1007/BF00117714

Scriven, M. (1967). “The methodology of evaluation,” in Perspectives of Curriculum Evaluation . eds. R. W. Tyler, R. M. Gagne, and M. Scriven (Chicago, IL: Rand McNally).

Shin, J., Guo, Q., and Gierl, M. J. (2021). “Automated essay scoring using deep learning algorithms,” in Handbook of Research on Modern Educational Technologies, Applications, and Management . ed. D. B. A. M. Khosrow-Pour (Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global).

Stobart, G. (2005). Fairness in multicultural assessment systems. Assess. Educ. Principles Policy Pract. 12, 275–287. doi: 10.1080/09695940500337249

Stobart, G. (2006). “The validity of formative assessment,” in Assessment and Learning . ed. J. Gardner (London: Sage).

Teltemann, J., and Klieme, E. (2016). “The impact of international testing projects on policy and practice,” in Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment . eds. G. T. L. Brown and L. R. Harris (New York: Routledge).

Thorndike, E. L. (1924). Measurement of intelligence. Psychol. Rev. 31, 219–252. doi: 10.1037/h0073975

Von Davier, A. A., Deonovic, B., Yudelson, M., Polyak, S. T., and Woo, A. (2019). Computational psychometrics approach to holistic learning and assessment systems. Front. Educ. 4:69. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00069

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes . Cambridge, MA:Harvard University Press.

Weiner, B. (1985). An Attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychol. Rev. 92, 548–573. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.92.4.548

Wherrett, S. (2004). The SATS story. The Guardian, 24 August.

Wise, S. L. (2019). Controlling construct-irrelevant factors through computer-based testing: disengagement, anxiety, & cheating. Educ. Inq. 10, 21–33. doi: 10.1080/20004508.2018.1490127

Wise, S. L., and Demars, C. E. (2005). Low examinee effort in low-stakes assessment: problems and potential solutions. Educ. Assess. 10, 1–17. doi: 10.1207/s15326977ea1001_1

Wise, S. L., and Smith, L. F. (2016). “The validity of assessment when students don’t give good effort,” in Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment . eds. G. T. L. Brown and L. R. Harris (New York: Routledge).

Yan, Z., and Brown, G. T. L. (2017). A cyclical self-assessment process: towards a model of how students engage in self-assessment. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 42, 1247–1262. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2016.1260091

Zhao, A., Brown, G. T. L., and Meissel, K. (2020). Manipulating the consequences of tests: how Shanghai teens react to different consequences. Educ. Res. Eval. 26, 221–251. doi: 10.1080/13803611.2021.1963938

Zhao, A., Brown, G. T. L., and Meissel, K. (2022). New Zealand students’ test-taking motivation: an experimental study examining the effects of stakes. Assess. Educ. 29, 1–25. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2022.2101043

Zumbo, B. D. (2015). Consequences, side effects and the ecology of testing: keys to considering assessment in vivo. Plenary Address to the 2015 Annual Conference of the Association for Educational Assessment—Europe (AEA-E). Glasgow, Scotland.

Zumbo, B. D., and Chan, E. K. H. (2014). Validity and Validation in Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences . Cham, CH: Springer Press.

Zumbo, B. D., and Forer, B. (2011). “Testing and measurement from a multilevel view: psychometrics and validation,” in High Stakes Testing in Education-Science and Practice in K-12 Settings . eds. J. A. Bovaird, K. F. Geisinger, and C. W. Buckendahl (Washington: American Psychological Association Press).

Zumbo, B. D., Maddox, B., and Care, N. M. (in press). Process and product in computer-based assessments: clearing the ground for a holistic validity framework. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess.

Keywords: assessment, testing, technology, psychometrics, psychology, curriculum, classroom

Citation: Brown GTL (2022) The past, present and future of educational assessment: A transdisciplinary perspective. Front. Educ . 7:1060633. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1060633

Received: 03 October 2022; Accepted: 25 October 2022; Published: 11 November 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Brown. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gavin T. L. Brown, [email protected] ; [email protected]

This article is part of the Research Topic

Horizons in Education 2022

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Am J Pharm Educ

- v.77(9); 2013 Nov 12

Educational Testing and Validity of Conclusions in the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

Michael j. peeters.

a College of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Toledo, Toledo, Ohio

Svetlana A. Beltyukova

b Judith Herb College of Education, University of Toledo, Toledo, Ohio

Beth A. Martin

c School of Pharmacy, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin

Validity and its integral evidence of reliability are fundamentals for educational and psychological measurement, and standards of educational testing. Herein, we describe these standards of educational testing, along with their subtypes including internal consistency, inter-rater reliability, and inter-rater agreement. Next, related issues of measurement error and effect size are discussed. This article concludes with a call for future authors to improve reporting of psychometrics and practical significance with educational testing in the pharmacy education literature. By increasing the scientific rigor of educational research and reporting, the overall quality and meaningfulness of SoTL will be improved.

INTRODUCTION

The rigor of education research, including research in medical education, has been under scrutiny for years. 1,2 On the technical side, issues raised include lack of examination of the psychometric properties of assessment instruments and/or insufficient reporting of validity and reliability. 3-5 On the applied side, researchers have frequently based their conclusions on significance without addressing the practical implications of their findings. 6 These issues appear even more pronounced in the pharmacy education literature. In a review of over 300 articles published in pharmacy and medical education journals using educational tests, Hoover and colleagues found that pharmacy education articles much more often lacked evidence of reliability (and consequently validity) than did medical education articles, while neither consistently reported validity evidence. 7 While not specifically evaluated in that study, few pharmacy education articles reported an effect size of their studied intervention (MJ Hoover, e-mail, April 17, 2013).

It is encouraging that diverse pharmacy education instructors have authored many of the reviewed articles, representing a scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL). However, authors still need to actively pursue psychometric evaluation of their student-learning assessments and examine the practical significance of the results. Increasing the technical rigor of research and reporting effect sizes will increase the overall quality and meaningfulness of SoTL. While doing so can be challenging, it can be accomplished without formal training. Just as scientists would not conduct experiments without verifying that their instruments were properly calibrated and would not claim that an experiment worked without indicating the magnitude of the effect, a SoTL investigator should not presume an assessment instrument’s reliability and validity but rather should seek evidence of both prior to attempting statistical analyses and interpret the results of those analyses from the perspective of educational significance (ie, effect size). This should be standard practice not only for standardized tests but also for other types of assessments of student knowledge and abilities, including performance-based assessments (eg, objective structured clinical examinations [OSCEs]) and traditional classroom assessments (eg, assessments with true/false, multiple-choice questions, case clinical notes, short-answer questions, and essay questions) used in SoTL.

This paper can be seen as an extension of a measurement series in Medical Education 8 for a SoTL audience, wherein it explicitly discusses the interrelatedness of psychometrics, statistics, and validity of conclusions. It is intended as a less-technical review of several established practices related to reporting educational test psychometrics and effect sizes, while also explaining how addressing both will contribute important evidence to the overall validity of data-based conclusions. Some of these practices involve statistical computations while others are based on logic. Following these practices should help SoTL investigators, who may not have formal training in psychometrics or statistics, to increase the rigor of their scholarship. We also offer a brief overview of some major advanced psychometric models that can be used to obtain further validity evidence. It is beyond the scope and focus of this paper to show how to create and administer assessments or how to calculate most statistics. We hope that the level of language, ideas, and examples herein will be relevant to the diverse readership. Examples from published studies, mainly in pharmacy education, are provided to illustrate some of the ways in which SoTL researchers could report findings.

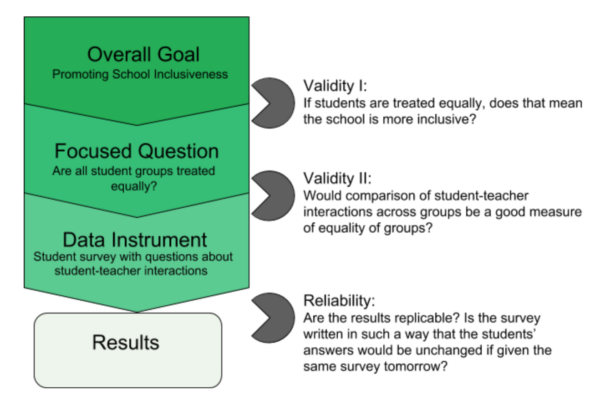

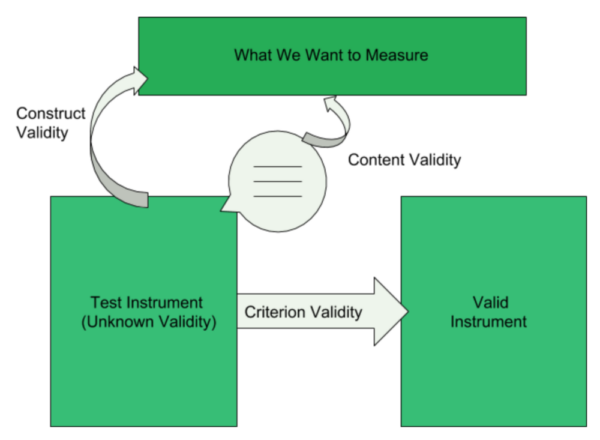

By its traditional definition, validity refers to the degree to which a test accurately and meaningfully measures what it is supposed to measure. The seminal work, Test Validity and the Ethics of Assessment reminds us that validity also refers to the appropriateness of inferences or conclusions from assessment data and emphasizes that it is an ethical responsibility of researchers to provide evidence in support of their inferences. 9 The more convincing the evidence, the stronger the validity of inferences and the higher the degree to which researchers’ interpretations of assessment results are justifiable and defensible. With the focus on the nature of evidence underlying validity of inferences, the unitary validity framework presented in this text forms the basis of current testing standards. 10

Differing from an older framework comprised of 3 separate types of validity (ie, content, criterion, and construct), Messick argues that “different kinds of inferences … require different kinds of evidence, not different kinds of validity” 9 and presents the current standards according to which researchers should think of validity as 1 unifying concept instead of several separate types of validity. 9 Further, researchers are advised to consider reliability as evidence of validity and not as a separate statistic. Approaching validity as 1 holistic concept allows researchers to focus on the evidence they need to collect to be confident in the quality of their assessment instrument. This evidence typically involves reliability or stability of the instrument, discussion of the content relevance of the items, evidence that the items form a stable linear measure that is able to differentiate more-able from less-able persons in a way that is meaningful and consistent with the theory. It is also sometimes necessary to establish that an assessment produces results comparable to some other well-known instrument or functions the same way with different subgroups; that is, researchers must frequently consider multiple sources of validity evidence to be able to argue with confidence that their assessment instrument generates meaningful data from which justifiable conclusions can be drawn. No single validity source can provide such evidence. Taking an evidence-seeking approach to validity also implies that validity is contextual and that gathering such evidence is a process wherein researchers seek their own evidence each time they use an assessment based on this proposed purpose, use, and interpretation. For this reason, researchers should not solely rely on validity evidence reported by others. As overwhelming as this may sound, it is a doable task that does not necessarily require advanced psychometric training. Validity is a matter of degree and researchers can always find ways to gather validity evidence at the level of their own expertise and may seek help from a psychometrician when needed. Much of validity evidence comes in the form of words and logical arguments, while some (eg, reliability) may involve statistical applications and even advanced psychometric analyses.

For example, every researcher should be able to provide evidence of content relevance and content coverage, and the process of gathering this evidence should start prior to administering an educational test. As part of the process, the researcher should operationally define the knowledge, skills, or abilities that are being measured. This does not require psychometric expertise and is deeply grounded in content expertise of the investigator(s) or other subject matter experts. To illustrate, let us examine an assessment of a physician’s ability to practice medicine. To determine if the assessment we are considering is the right one to use, we need to reflect on how we define this ability and then draw on existing evidence and theories. Alternatively, we could match test items to a blueprint created after surveying numerous other content experts in the practice of medicine. If we define a physician’s ability to practice medicine as the ability to apply knowledge, concepts, and principles, and to demonstrate fundamental patient-centered skills, the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 3 would be a test of choice 11 ; however, this examination would not be appropriate to use in nurse or pharmacist licensing because validity is contextual. For reporting purposes, an operational definition of what is being measured should be explicitly presented, given that inferences about the construct evaluated are based on this definition. The operational definition also becomes the driving factor in determining whether the right questions are included and whether they are constructed in such a way that they will elicit the needed information. Later in the research process, all of this knowledge about content relevance and coverage becomes evidence that is used to argue the validity of test-score interpretations and inferences about the construct after the statistical analyses are completed. In the example above, the term “validity of an examination” was deliberately avoided; instead, the focus was on “validity of inferences ” or “validity of conclusions ” from the data generated by an examination in this sample of participants.

Gathering validity evidence does not stop at the item review and instrument selection stages. Although evidence of content coverage and relevance contributes important information about the construct being measured and might influence the nature of inferences, it cannot be used in direct support of inferences from the scores. 9 Therefore, while it is important to collect content-related evidence, investigators also need to seek other evidence after participants have completed the test, focusing on internal structure evidence, including reliability . Collection of this evidence involves investigating the extent to which survey instrument items function well together to measure the underlying construct in a meaningful way, and for this task, researchers typically consider several different options, such as computing reliability indices, conducting an item analysis, using factor analysis, using generalizability theory, and applying item response theory. If problems such as low internal consistency or inter-rater reliability, lack of the meaning of a variable, poor item fit, multidimensionality, lack of variance explained, or inconsistent item functioning across different subgroups of respondents are discovered, interpretations of the results and inferences about the construct should not be attempted. Instead, the investigator should go back to the drawing board, revisit the theory behind the construct, reexamine content relevance and coverage, and start the process again until the content and structure-related evidence points to good psychometric properties of an assessment instrument.

RELIABILITY

Reliability — reproducibility or consistency of assessment scores within a sample of participants — is a major initial quantitative “quality index” of the assessment data as well as essential evidence toward the overall validity. However, as with any other validity evidence, its use alone is not sufficient for arguing overall validity. Reliability alone has limited usefulness because it indicates only that an assessment’s items measure something consistently. Reliability does not indicate what knowledge, skills and/or abilities are being measured. Thus, along with reliability, other validity evidence is crucial before any validity conclusions can be made.

While seeking reliability evidence, researchers should select the most appropriate type and explicitly identify this type while reporting a SoTL study. Two common types of reliability include internal consistency reliability and inter-rater reliability. The first is particularly relevant for many SoTL investigators . The internal consistency reliability index shows the extent to which patterns of responses are consistent across items on a single test occasion, whereas the inter-rater reliability index indicates consistency across raters and is reported when judges or scorers are involved. That said, it is also possible and sometimes necessary to report more than 1 reliability index (eg, when using multiple educational tests). In many instances, reliability is specific to each use of an assessment and can change when the assessment is used with another group or when an assessment is even slightly modified. Thus, it is prudent to report reliability for every occasion within any scholarship. 12

Reliability can be relative or absolute. 13,14 When repeated measurements are used, relative reliability refers to a consistency or reproducibility of rankings of scores in a sample, whereas absolute reliability refers to the degree to which individual scores are reproduced (eg, when judges agree on 1 specific score). A relative reliability index can be helpful when student performances are ranked in relation to 1 another, whereas absolute reliability could be helpful when the focus is on specific scores from an evaluation. Of the 2, absolute reliability is often omitted, even though it is considered by some to be of greater clinical 15 and educational 16-18 value. Standard error of measurement (SEM) is a recommended absolute reliability index to report, whereas internal consistency reliability would be a choice as relative reliability index. That said, both absolute and relative reliability should be assessed when appropriate.

Internal Consistency Reliability