Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Content Analysis | Guide, Methods & Examples

Content Analysis | Guide, Methods & Examples

Published on July 18, 2019 by Amy Luo . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Content analysis is a research method used to identify patterns in recorded communication. To conduct content analysis, you systematically collect data from a set of texts, which can be written, oral, or visual:

- Books, newspapers and magazines

- Speeches and interviews

- Web content and social media posts

- Photographs and films

Content analysis can be both quantitative (focused on counting and measuring) and qualitative (focused on interpreting and understanding). In both types, you categorize or “code” words, themes, and concepts within the texts and then analyze the results.

Table of contents

What is content analysis used for, advantages of content analysis, disadvantages of content analysis, how to conduct content analysis, other interesting articles.

Researchers use content analysis to find out about the purposes, messages, and effects of communication content. They can also make inferences about the producers and audience of the texts they analyze.

Content analysis can be used to quantify the occurrence of certain words, phrases, subjects or concepts in a set of historical or contemporary texts.

Quantitative content analysis example

To research the importance of employment issues in political campaigns, you could analyze campaign speeches for the frequency of terms such as unemployment , jobs , and work and use statistical analysis to find differences over time or between candidates.

In addition, content analysis can be used to make qualitative inferences by analyzing the meaning and semantic relationship of words and concepts.

Qualitative content analysis example

To gain a more qualitative understanding of employment issues in political campaigns, you could locate the word unemployment in speeches, identify what other words or phrases appear next to it (such as economy, inequality or laziness ), and analyze the meanings of these relationships to better understand the intentions and targets of different campaigns.

Because content analysis can be applied to a broad range of texts, it is used in a variety of fields, including marketing, media studies, anthropology, cognitive science, psychology, and many social science disciplines. It has various possible goals:

- Finding correlations and patterns in how concepts are communicated

- Understanding the intentions of an individual, group or institution

- Identifying propaganda and bias in communication

- Revealing differences in communication in different contexts

- Analyzing the consequences of communication content, such as the flow of information or audience responses

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

- Unobtrusive data collection

You can analyze communication and social interaction without the direct involvement of participants, so your presence as a researcher doesn’t influence the results.

- Transparent and replicable

When done well, content analysis follows a systematic procedure that can easily be replicated by other researchers, yielding results with high reliability .

- Highly flexible

You can conduct content analysis at any time, in any location, and at low cost – all you need is access to the appropriate sources.

Focusing on words or phrases in isolation can sometimes be overly reductive, disregarding context, nuance, and ambiguous meanings.

Content analysis almost always involves some level of subjective interpretation, which can affect the reliability and validity of the results and conclusions, leading to various types of research bias and cognitive bias .

- Time intensive

Manually coding large volumes of text is extremely time-consuming, and it can be difficult to automate effectively.

If you want to use content analysis in your research, you need to start with a clear, direct research question .

Example research question for content analysis

Is there a difference in how the US media represents younger politicians compared to older ones in terms of trustworthiness?

Next, you follow these five steps.

1. Select the content you will analyze

Based on your research question, choose the texts that you will analyze. You need to decide:

- The medium (e.g. newspapers, speeches or websites) and genre (e.g. opinion pieces, political campaign speeches, or marketing copy)

- The inclusion and exclusion criteria (e.g. newspaper articles that mention a particular event, speeches by a certain politician, or websites selling a specific type of product)

- The parameters in terms of date range, location, etc.

If there are only a small amount of texts that meet your criteria, you might analyze all of them. If there is a large volume of texts, you can select a sample .

2. Define the units and categories of analysis

Next, you need to determine the level at which you will analyze your chosen texts. This means defining:

- The unit(s) of meaning that will be coded. For example, are you going to record the frequency of individual words and phrases, the characteristics of people who produced or appear in the texts, the presence and positioning of images, or the treatment of themes and concepts?

- The set of categories that you will use for coding. Categories can be objective characteristics (e.g. aged 30-40 , lawyer , parent ) or more conceptual (e.g. trustworthy , corrupt , conservative , family oriented ).

Your units of analysis are the politicians who appear in each article and the words and phrases that are used to describe them. Based on your research question, you have to categorize based on age and the concept of trustworthiness. To get more detailed data, you also code for other categories such as their political party and the marital status of each politician mentioned.

3. Develop a set of rules for coding

Coding involves organizing the units of meaning into the previously defined categories. Especially with more conceptual categories, it’s important to clearly define the rules for what will and won’t be included to ensure that all texts are coded consistently.

Coding rules are especially important if multiple researchers are involved, but even if you’re coding all of the text by yourself, recording the rules makes your method more transparent and reliable.

In considering the category “younger politician,” you decide which titles will be coded with this category ( senator, governor, counselor, mayor ). With “trustworthy”, you decide which specific words or phrases related to trustworthiness (e.g. honest and reliable ) will be coded in this category.

4. Code the text according to the rules

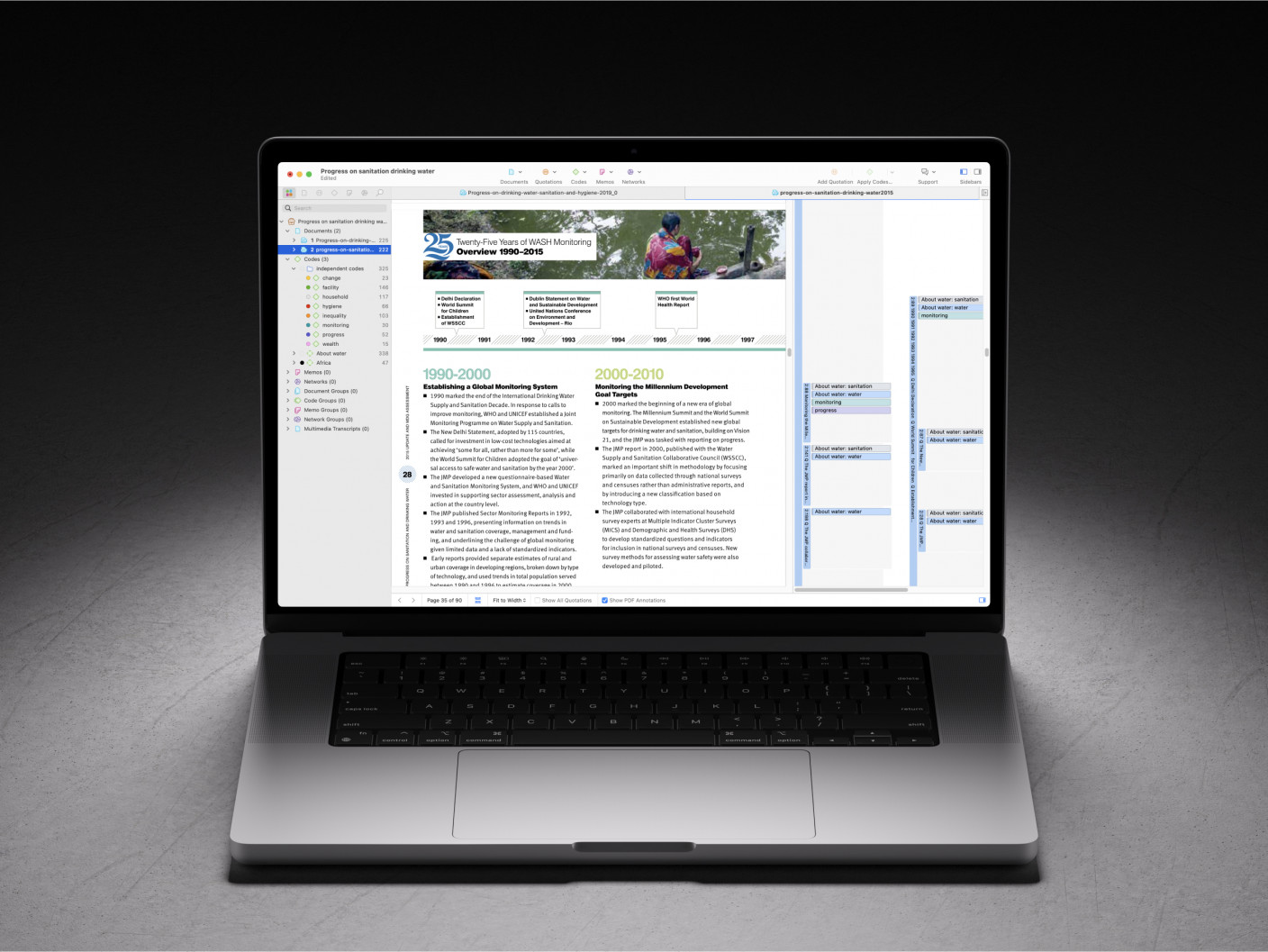

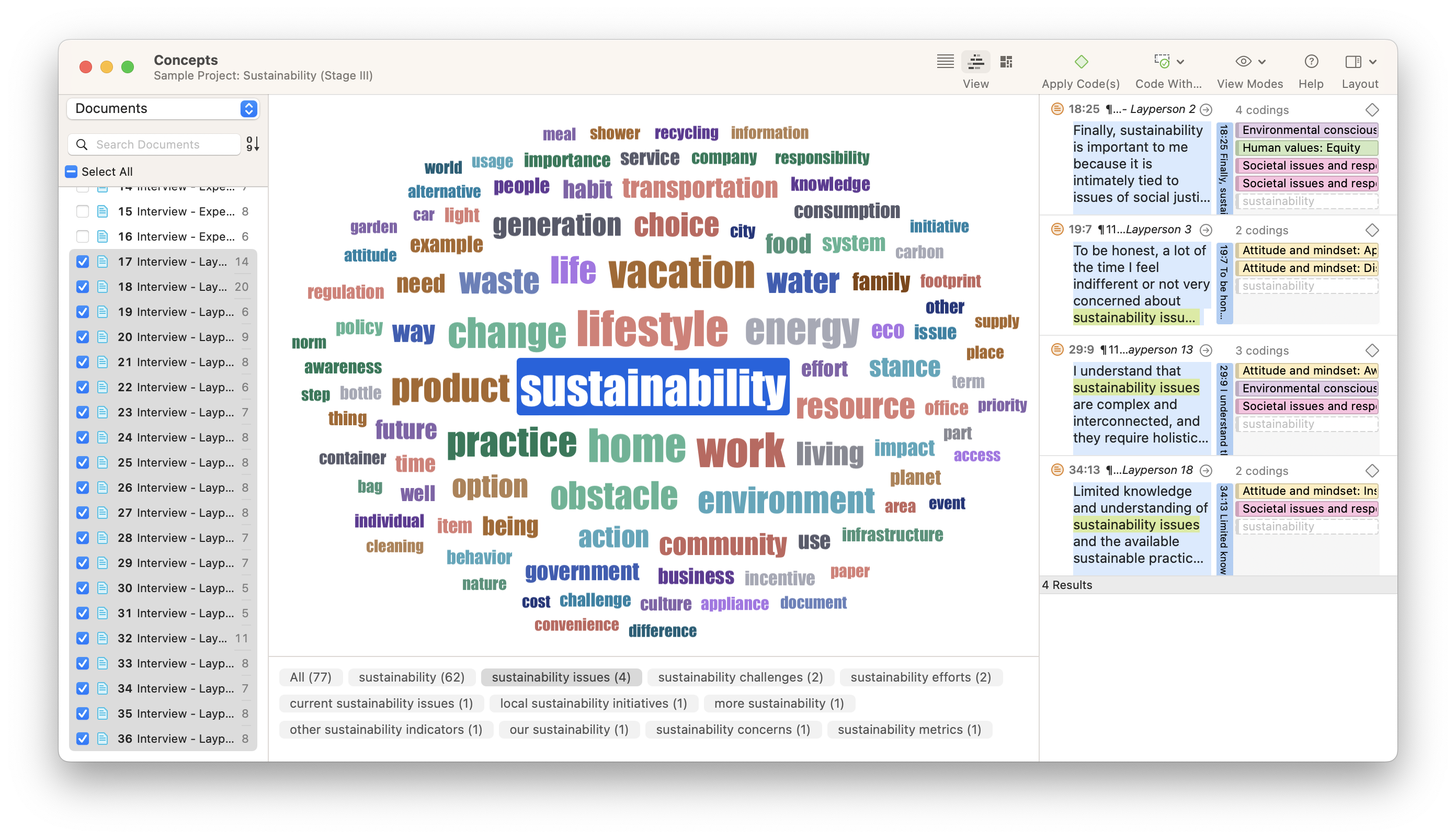

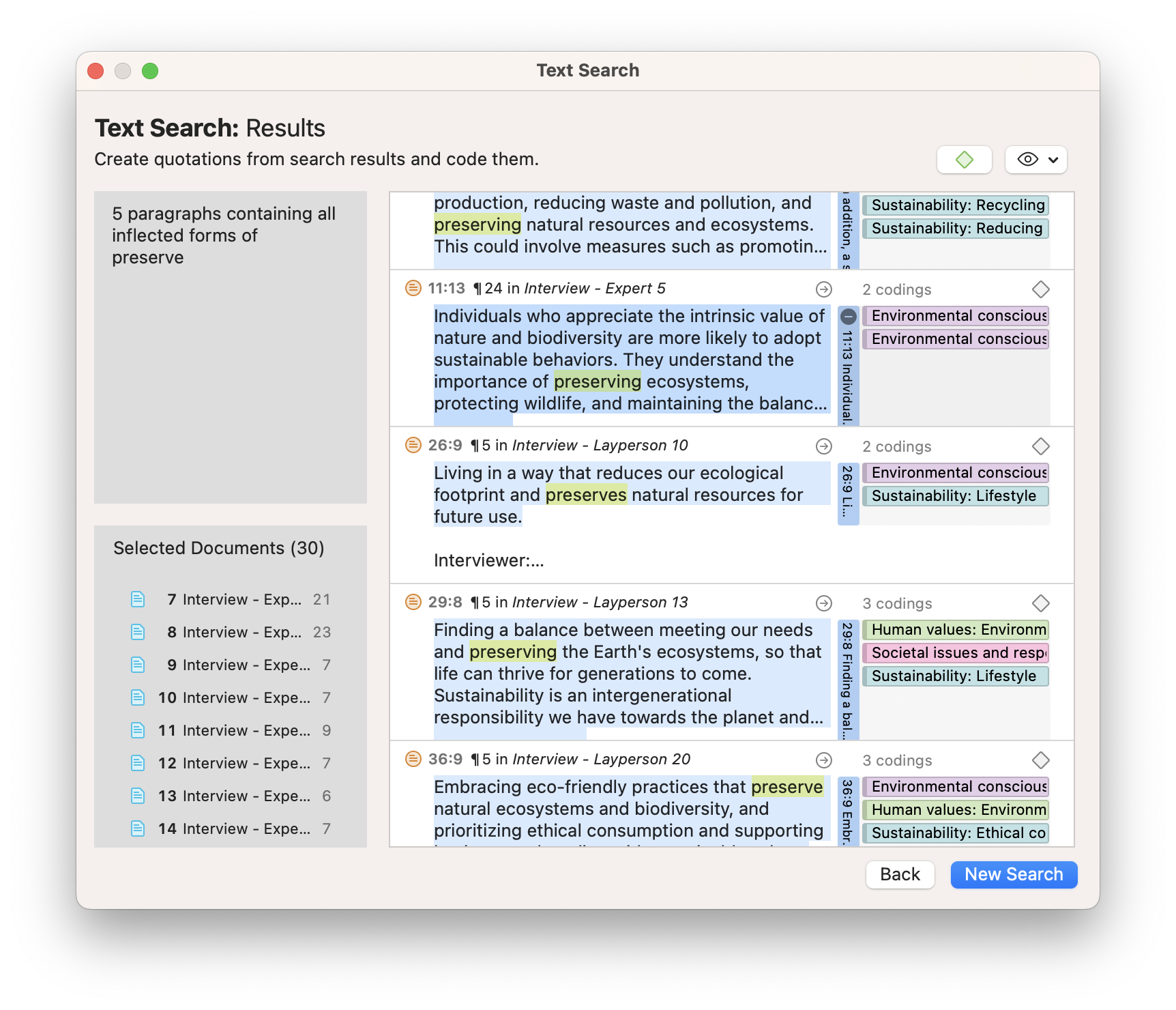

You go through each text and record all relevant data in the appropriate categories. This can be done manually or aided with computer programs, such as QSR NVivo , Atlas.ti and Diction , which can help speed up the process of counting and categorizing words and phrases.

Following your coding rules, you examine each newspaper article in your sample. You record the characteristics of each politician mentioned, along with all words and phrases related to trustworthiness that are used to describe them.

5. Analyze the results and draw conclusions

Once coding is complete, the collected data is examined to find patterns and draw conclusions in response to your research question. You might use statistical analysis to find correlations or trends, discuss your interpretations of what the results mean, and make inferences about the creators, context and audience of the texts.

Let’s say the results reveal that words and phrases related to trustworthiness appeared in the same sentence as an older politician more frequently than they did in the same sentence as a younger politician. From these results, you conclude that national newspapers present older politicians as more trustworthy than younger politicians, and infer that this might have an effect on readers’ perceptions of younger people in politics.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Cohort study

- Peer review

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Luo, A. (2023, June 22). Content Analysis | Guide, Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/content-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked

Qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, descriptive research | definition, types, methods & examples, reliability vs. validity in research | difference, types and examples, what is your plagiarism score.

What Is Qualitative Content Analysis?

Qca explained simply (with examples).

By: Jenna Crosley (PhD). Reviewed by: Dr Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | February 2021

If you’re in the process of preparing for your dissertation, thesis or research project, you’ve probably encountered the term “ qualitative content analysis ” – it’s quite a mouthful. If you’ve landed on this post, you’re probably a bit confused about it. Well, the good news is that you’ve come to the right place…

Overview: Qualitative Content Analysis

- What (exactly) is qualitative content analysis

- The two main types of content analysis

- When to use content analysis

- How to conduct content analysis (the process)

- The advantages and disadvantages of content analysis

1. What is content analysis?

Content analysis is a qualitative analysis method that focuses on recorded human artefacts such as manuscripts, voice recordings and journals. Content analysis investigates these written, spoken and visual artefacts without explicitly extracting data from participants – this is called unobtrusive research.

In other words, with content analysis, you don’t necessarily need to interact with participants (although you can if necessary); you can simply analyse the data that they have already produced. With this type of analysis, you can analyse data such as text messages, books, Facebook posts, videos, and audio (just to mention a few).

The basics – explicit and implicit content

When working with content analysis, explicit and implicit content will play a role. Explicit data is transparent and easy to identify, while implicit data is that which requires some form of interpretation and is often of a subjective nature. Sounds a bit fluffy? Here’s an example:

Joe: Hi there, what can I help you with?

Lauren: I recently adopted a puppy and I’m worried that I’m not feeding him the right food. Could you please advise me on what I should be feeding?

Joe: Sure, just follow me and I’ll show you. Do you have any other pets?

Lauren: Only one, and it tweets a lot!

In this exchange, the explicit data indicates that Joe is helping Lauren to find the right puppy food. Lauren asks Joe whether she has any pets aside from her puppy. This data is explicit because it requires no interpretation.

On the other hand, implicit data , in this case, includes the fact that the speakers are in a pet store. This information is not clearly stated but can be inferred from the conversation, where Joe is helping Lauren to choose pet food. An additional piece of implicit data is that Lauren likely has some type of bird as a pet. This can be inferred from the way that Lauren states that her pet “tweets”.

As you can see, explicit and implicit data both play a role in human interaction and are an important part of your analysis. However, it’s important to differentiate between these two types of data when you’re undertaking content analysis. Interpreting implicit data can be rather subjective as conclusions are based on the researcher’s interpretation. This can introduce an element of bias , which risks skewing your results.

2. The two types of content analysis

Now that you understand the difference between implicit and explicit data, let’s move on to the two general types of content analysis : conceptual and relational content analysis. Importantly, while conceptual and relational content analysis both follow similar steps initially, the aims and outcomes of each are different.

Conceptual analysis focuses on the number of times a concept occurs in a set of data and is generally focused on explicit data. For example, if you were to have the following conversation:

Marie: She told me that she has three cats.

Jean: What are her cats’ names?

Marie: I think the first one is Bella, the second one is Mia, and… I can’t remember the third cat’s name.

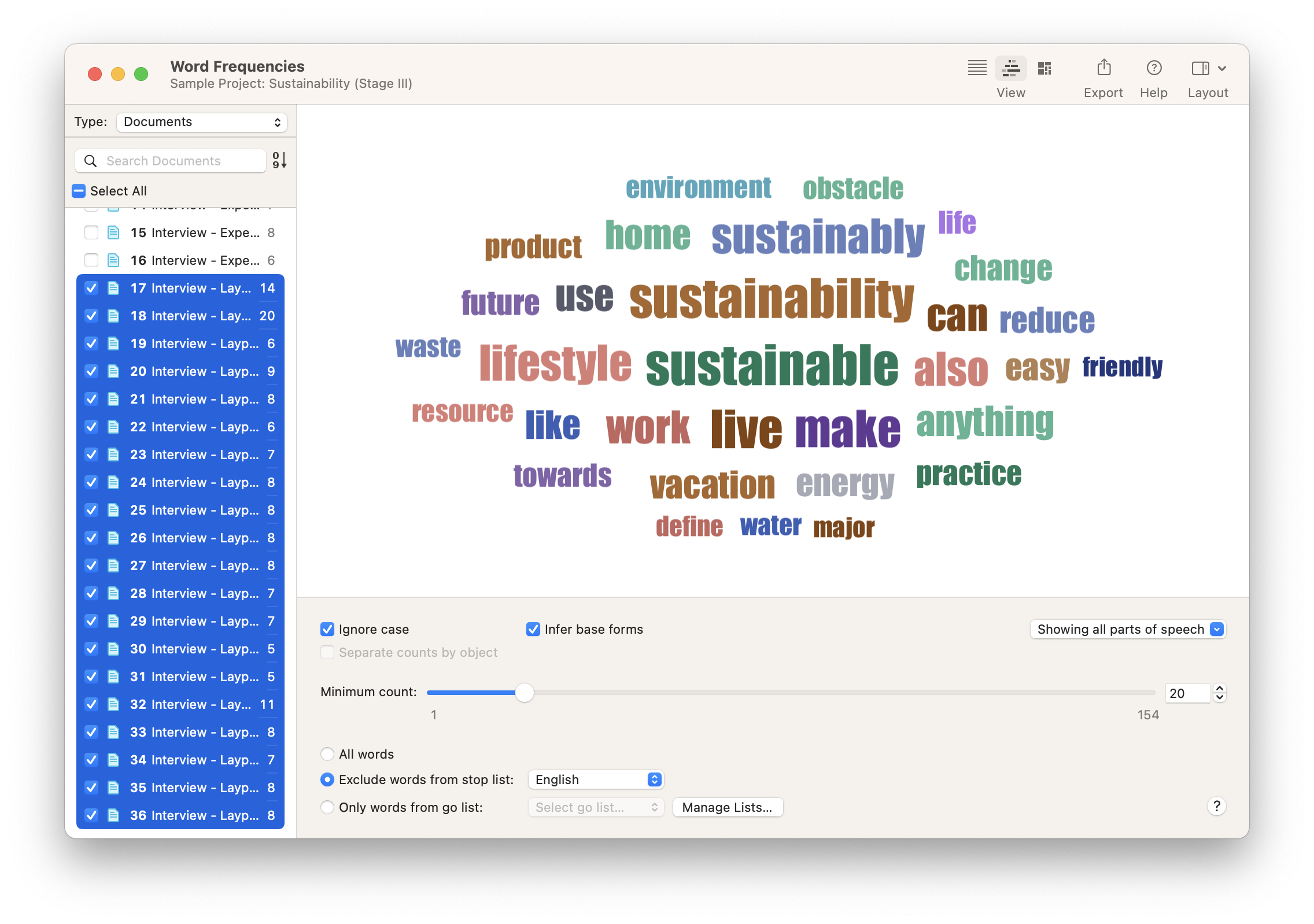

In this data, you can see that the word “cat” has been used three times. Through conceptual content analysis, you can deduce that cats are the central topic of the conversation. You can also perform a frequency analysis , where you assess the term’s frequency in the data. For example, in the exchange above, the word “cat” makes up 9% of the data. In other words, conceptual analysis brings a little bit of quantitative analysis into your qualitative analysis.

As you can see, the above data is without interpretation and focuses on explicit data . Relational content analysis, on the other hand, takes a more holistic view by focusing more on implicit data in terms of context, surrounding words and relationships.

There are three types of relational analysis:

- Affect extraction

- Proximity analysis

- Cognitive mapping

Affect extraction is when you assess concepts according to emotional attributes. These emotions are typically mapped on scales, such as a Likert scale or a rating scale ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 is “very sad” and 5 is “very happy”.

If participants are talking about their achievements, they are likely to be given a score of 4 or 5, depending on how good they feel about it. If a participant is describing a traumatic event, they are likely to have a much lower score, either 1 or 2.

Proximity analysis identifies explicit terms (such as those found in a conceptual analysis) and the patterns in terms of how they co-occur in a text. In other words, proximity analysis investigates the relationship between terms and aims to group these to extract themes and develop meaning.

Proximity analysis is typically utilised when you’re looking for hard facts rather than emotional, cultural, or contextual factors. For example, if you were to analyse a political speech, you may want to focus only on what has been said, rather than implications or hidden meanings. To do this, you would make use of explicit data, discounting any underlying meanings and implications of the speech.

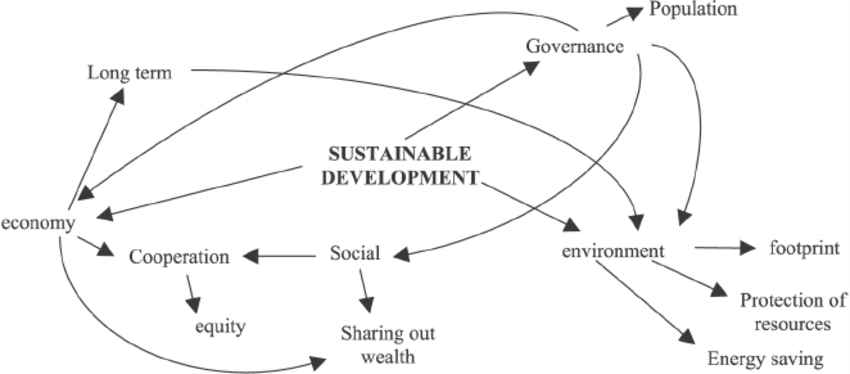

Lastly, there’s cognitive mapping, which can be used in addition to, or along with, proximity analysis. Cognitive mapping involves taking different texts and comparing them in a visual format – i.e. a cognitive map. Typically, you’d use cognitive mapping in studies that assess changes in terms, definitions, and meanings over time. It can also serve as a way to visualise affect extraction or proximity analysis and is often presented in a form such as a graphic map.

To recap on the essentials, content analysis is a qualitative analysis method that focuses on recorded human artefacts . It involves both conceptual analysis (which is more numbers-based) and relational analysis (which focuses on the relationships between concepts and how they’re connected).

Need a helping hand?

3. When should you use content analysis?

Content analysis is a useful tool that provides insight into trends of communication . For example, you could use a discussion forum as the basis of your analysis and look at the types of things the members talk about as well as how they use language to express themselves. Content analysis is flexible in that it can be applied to the individual, group, and institutional level.

Content analysis is typically used in studies where the aim is to better understand factors such as behaviours, attitudes, values, emotions, and opinions . For example, you could use content analysis to investigate an issue in society, such as miscommunication between cultures. In this example, you could compare patterns of communication in participants from different cultures, which will allow you to create strategies for avoiding misunderstandings in intercultural interactions.

Another example could include conducting content analysis on a publication such as a book. Here you could gather data on the themes, topics, language use and opinions reflected in the text to draw conclusions regarding the political (such as conservative or liberal) leanings of the publication.

4. How to conduct a qualitative content analysis

Conceptual and relational content analysis differ in terms of their exact process ; however, there are some similarities. Let’s have a look at these first – i.e., the generic process:

- Recap on your research questions

- Undertake bracketing to identify biases

- Operationalise your variables and develop a coding scheme

- Code the data and undertake your analysis

Step 1 – Recap on your research questions

It’s always useful to begin a project with research questions , or at least with an idea of what you are looking for. In fact, if you’ve spent time reading this blog, you’ll know that it’s useful to recap on your research questions, aims and objectives when undertaking pretty much any research activity. In the context of content analysis, it’s difficult to know what needs to be coded and what doesn’t, without a clear view of the research questions.

For example, if you were to code a conversation focused on basic issues of social justice, you may be met with a wide range of topics that may be irrelevant to your research. However, if you approach this data set with the specific intent of investigating opinions on gender issues, you will be able to focus on this topic alone, which would allow you to code only what you need to investigate.

Step 2 – Reflect on your personal perspectives and biases

It’s vital that you reflect on your own pre-conception of the topic at hand and identify the biases that you might drag into your content analysis – this is called “ bracketing “. By identifying this upfront, you’ll be more aware of them and less likely to have them subconsciously influence your analysis.

For example, if you were to investigate how a community converses about unequal access to healthcare, it is important to assess your views to ensure that you don’t project these onto your understanding of the opinions put forth by the community. If you have access to medical aid, for instance, you should not allow this to interfere with your examination of unequal access.

Step 3 – Operationalise your variables and develop a coding scheme

Next, you need to operationalise your variables . But what does that mean? Simply put, it means that you have to define each variable or construct . Give every item a clear definition – what does it mean (include) and what does it not mean (exclude). For example, if you were to investigate children’s views on healthy foods, you would first need to define what age group/range you’re looking at, and then also define what you mean by “healthy foods”.

In combination with the above, it is important to create a coding scheme , which will consist of information about your variables (how you defined each variable), as well as a process for analysing the data. For this, you would refer back to how you operationalised/defined your variables so that you know how to code your data.

For example, when coding, when should you code a food as “healthy”? What makes a food choice healthy? Is it the absence of sugar or saturated fat? Is it the presence of fibre and protein? It’s very important to have clearly defined variables to achieve consistent coding – without this, your analysis will get very muddy, very quickly.

Step 4 – Code and analyse the data

The next step is to code the data. At this stage, there are some differences between conceptual and relational analysis.

As described earlier in this post, conceptual analysis looks at the existence and frequency of concepts, whereas a relational analysis looks at the relationships between concepts. For both types of analyses, it is important to pre-select a concept that you wish to assess in your data. Using the example of studying children’s views on healthy food, you could pre-select the concept of “healthy food” and assess the number of times the concept pops up in your data.

Here is where conceptual and relational analysis start to differ.

At this stage of conceptual analysis , it is necessary to decide on the level of analysis you’ll perform on your data, and whether this will exist on the word, phrase, sentence, or thematic level. For example, will you code the phrase “healthy food” on its own? Will you code each term relating to healthy food (e.g., broccoli, peaches, bananas, etc.) with the code “healthy food” or will these be coded individually? It is very important to establish this from the get-go to avoid inconsistencies that could result in you having to code your data all over again.

On the other hand, relational analysis looks at the type of analysis. So, will you use affect extraction? Proximity analysis? Cognitive mapping? A mix? It’s vital to determine the type of analysis before you begin to code your data so that you can maintain the reliability and validity of your research .

How to conduct conceptual analysis

First, let’s have a look at the process for conceptual analysis.

Once you’ve decided on your level of analysis, you need to establish how you will code your concepts, and how many of these you want to code. Here you can choose whether you want to code in a deductive or inductive manner. Just to recap, deductive coding is when you begin the coding process with a set of pre-determined codes, whereas inductive coding entails the codes emerging as you progress with the coding process. Here it is also important to decide what should be included and excluded from your analysis, and also what levels of implication you wish to include in your codes.

For example, if you have the concept of “tall”, can you include “up in the clouds”, derived from the sentence, “the giraffe’s head is up in the clouds” in the code, or should it be a separate code? In addition to this, you need to know what levels of words may be included in your codes or not. For example, if you say, “the panda is cute” and “look at the panda’s cuteness”, can “cute” and “cuteness” be included under the same code?

Once you’ve considered the above, it’s time to code the text . We’ve already published a detailed post about coding , so we won’t go into that process here. Once you’re done coding, you can move on to analysing your results. This is where you will aim to find generalisations in your data, and thus draw your conclusions .

How to conduct relational analysis

Now let’s return to relational analysis.

As mentioned, you want to look at the relationships between concepts . To do this, you’ll need to create categories by reducing your data (in other words, grouping similar concepts together) and then also code for words and/or patterns. These are both done with the aim of discovering whether these words exist, and if they do, what they mean.

Your next step is to assess your data and to code the relationships between your terms and meanings, so that you can move on to your final step, which is to sum up and analyse the data.

To recap, it’s important to start your analysis process by reviewing your research questions and identifying your biases . From there, you need to operationalise your variables, code your data and then analyse it.

5. What are the pros & cons of content analysis?

One of the main advantages of content analysis is that it allows you to use a mix of quantitative and qualitative research methods, which results in a more scientifically rigorous analysis.

For example, with conceptual analysis, you can count the number of times that a term or a code appears in a dataset, which can be assessed from a quantitative standpoint. In addition to this, you can then use a qualitative approach to investigate the underlying meanings of these and relationships between them.

Content analysis is also unobtrusive and therefore poses fewer ethical issues than some other analysis methods. As the content you’ll analyse oftentimes already exists, you’ll analyse what has been produced previously, and so you won’t have to collect data directly from participants. When coded correctly, data is analysed in a very systematic and transparent manner, which means that issues of replicability (how possible it is to recreate research under the same conditions) are reduced greatly.

On the downside , qualitative research (in general, not just content analysis) is often critiqued for being too subjective and for not being scientifically rigorous enough. This is where reliability (how replicable a study is by other researchers) and validity (how suitable the research design is for the topic being investigated) come into play – if you take these into account, you’ll be on your way to achieving sound research results.

Recap: Qualitative content analysis

In this post, we’ve covered a lot of ground – click on any of the sections to recap:

If you have any questions about qualitative content analysis, feel free to leave a comment below. If you’d like 1-on-1 help with your qualitative content analysis, be sure to book an initial consultation with one of our friendly Research Coaches.

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

You Might Also Like:

13 Comments

If I am having three pre-decided attributes for my research based on which a set of semi-structured questions where asked then should I conduct a conceptual content analysis or relational content analysis. please note that all three attributes are different like Agility, Resilience and AI.

Thank you very much. I really enjoyed every word.

please send me one/ two sample of content analysis

send me to any sample of qualitative content analysis as soon as possible

Many thanks for the brilliant explanation. Do you have a sample practical study of a foreign policy using content analysis?

1) It will be very much useful if a small but complete content analysis can be sent, from research question to coding and analysis. 2) Is there any software by which qualitative content analysis can be done?

Common software for qualitative analysis is nVivo, and quantitative analysis is IBM SPSS

Thank you. Can I have at least 2 copies of a sample analysis study as my reference?

Could you please send me some sample of textbook content analysis?

Can I send you my research topic, aims, objectives and questions to give me feedback on them?

please could you send me samples of content analysis?

really we enjoyed your knowledge thanks allot. from Ethiopia

can you please share some samples of content analysis(relational)? I am a bit confused about processing the analysis part

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Skip to content

Read the latest news stories about Mailman faculty, research, and events.

Departments

We integrate an innovative skills-based curriculum, research collaborations, and hands-on field experience to prepare students.

Learn more about our research centers, which focus on critical issues in public health.

Our Faculty

Meet the faculty of the Mailman School of Public Health.

Become a Student

Life and community, how to apply.

Learn how to apply to the Mailman School of Public Health.

Content Analysis

Content analysis is a research tool used to determine the presence of certain words, themes, or concepts within some given qualitative data (i.e. text). Using content analysis, researchers can quantify and analyze the presence, meanings, and relationships of such certain words, themes, or concepts. As an example, researchers can evaluate language used within a news article to search for bias or partiality. Researchers can then make inferences about the messages within the texts, the writer(s), the audience, and even the culture and time of surrounding the text.

Description

Sources of data could be from interviews, open-ended questions, field research notes, conversations, or literally any occurrence of communicative language (such as books, essays, discussions, newspaper headlines, speeches, media, historical documents). A single study may analyze various forms of text in its analysis. To analyze the text using content analysis, the text must be coded, or broken down, into manageable code categories for analysis (i.e. “codes”). Once the text is coded into code categories, the codes can then be further categorized into “code categories” to summarize data even further.

Three different definitions of content analysis are provided below.

Definition 1: “Any technique for making inferences by systematically and objectively identifying special characteristics of messages.” (from Holsti, 1968)

Definition 2: “An interpretive and naturalistic approach. It is both observational and narrative in nature and relies less on the experimental elements normally associated with scientific research (reliability, validity, and generalizability) (from Ethnography, Observational Research, and Narrative Inquiry, 1994-2012).

Definition 3: “A research technique for the objective, systematic and quantitative description of the manifest content of communication.” (from Berelson, 1952)

Uses of Content Analysis

Identify the intentions, focus or communication trends of an individual, group or institution

Describe attitudinal and behavioral responses to communications

Determine the psychological or emotional state of persons or groups

Reveal international differences in communication content

Reveal patterns in communication content

Pre-test and improve an intervention or survey prior to launch

Analyze focus group interviews and open-ended questions to complement quantitative data

Types of Content Analysis

There are two general types of content analysis: conceptual analysis and relational analysis. Conceptual analysis determines the existence and frequency of concepts in a text. Relational analysis develops the conceptual analysis further by examining the relationships among concepts in a text. Each type of analysis may lead to different results, conclusions, interpretations and meanings.

Conceptual Analysis

Typically people think of conceptual analysis when they think of content analysis. In conceptual analysis, a concept is chosen for examination and the analysis involves quantifying and counting its presence. The main goal is to examine the occurrence of selected terms in the data. Terms may be explicit or implicit. Explicit terms are easy to identify. Coding of implicit terms is more complicated: you need to decide the level of implication and base judgments on subjectivity (an issue for reliability and validity). Therefore, coding of implicit terms involves using a dictionary or contextual translation rules or both.

To begin a conceptual content analysis, first identify the research question and choose a sample or samples for analysis. Next, the text must be coded into manageable content categories. This is basically a process of selective reduction. By reducing the text to categories, the researcher can focus on and code for specific words or patterns that inform the research question.

General steps for conducting a conceptual content analysis:

1. Decide the level of analysis: word, word sense, phrase, sentence, themes

2. Decide how many concepts to code for: develop a pre-defined or interactive set of categories or concepts. Decide either: A. to allow flexibility to add categories through the coding process, or B. to stick with the pre-defined set of categories.

Option A allows for the introduction and analysis of new and important material that could have significant implications to one’s research question.

Option B allows the researcher to stay focused and examine the data for specific concepts.

3. Decide whether to code for existence or frequency of a concept. The decision changes the coding process.

When coding for the existence of a concept, the researcher would count a concept only once if it appeared at least once in the data and no matter how many times it appeared.

When coding for the frequency of a concept, the researcher would count the number of times a concept appears in a text.

4. Decide on how you will distinguish among concepts:

Should text be coded exactly as they appear or coded as the same when they appear in different forms? For example, “dangerous” vs. “dangerousness”. The point here is to create coding rules so that these word segments are transparently categorized in a logical fashion. The rules could make all of these word segments fall into the same category, or perhaps the rules can be formulated so that the researcher can distinguish these word segments into separate codes.

What level of implication is to be allowed? Words that imply the concept or words that explicitly state the concept? For example, “dangerous” vs. “the person is scary” vs. “that person could cause harm to me”. These word segments may not merit separate categories, due the implicit meaning of “dangerous”.

5. Develop rules for coding your texts. After decisions of steps 1-4 are complete, a researcher can begin developing rules for translation of text into codes. This will keep the coding process organized and consistent. The researcher can code for exactly what he/she wants to code. Validity of the coding process is ensured when the researcher is consistent and coherent in their codes, meaning that they follow their translation rules. In content analysis, obeying by the translation rules is equivalent to validity.

6. Decide what to do with irrelevant information: should this be ignored (e.g. common English words like “the” and “and”), or used to reexamine the coding scheme in the case that it would add to the outcome of coding?

7. Code the text: This can be done by hand or by using software. By using software, researchers can input categories and have coding done automatically, quickly and efficiently, by the software program. When coding is done by hand, a researcher can recognize errors far more easily (e.g. typos, misspelling). If using computer coding, text could be cleaned of errors to include all available data. This decision of hand vs. computer coding is most relevant for implicit information where category preparation is essential for accurate coding.

8. Analyze your results: Draw conclusions and generalizations where possible. Determine what to do with irrelevant, unwanted, or unused text: reexamine, ignore, or reassess the coding scheme. Interpret results carefully as conceptual content analysis can only quantify the information. Typically, general trends and patterns can be identified.

Relational Analysis

Relational analysis begins like conceptual analysis, where a concept is chosen for examination. However, the analysis involves exploring the relationships between concepts. Individual concepts are viewed as having no inherent meaning and rather the meaning is a product of the relationships among concepts.

To begin a relational content analysis, first identify a research question and choose a sample or samples for analysis. The research question must be focused so the concept types are not open to interpretation and can be summarized. Next, select text for analysis. Select text for analysis carefully by balancing having enough information for a thorough analysis so results are not limited with having information that is too extensive so that the coding process becomes too arduous and heavy to supply meaningful and worthwhile results.

There are three subcategories of relational analysis to choose from prior to going on to the general steps.

Affect extraction: an emotional evaluation of concepts explicit in a text. A challenge to this method is that emotions can vary across time, populations, and space. However, it could be effective at capturing the emotional and psychological state of the speaker or writer of the text.

Proximity analysis: an evaluation of the co-occurrence of explicit concepts in the text. Text is defined as a string of words called a “window” that is scanned for the co-occurrence of concepts. The result is the creation of a “concept matrix”, or a group of interrelated co-occurring concepts that would suggest an overall meaning.

Cognitive mapping: a visualization technique for either affect extraction or proximity analysis. Cognitive mapping attempts to create a model of the overall meaning of the text such as a graphic map that represents the relationships between concepts.

General steps for conducting a relational content analysis:

1. Determine the type of analysis: Once the sample has been selected, the researcher needs to determine what types of relationships to examine and the level of analysis: word, word sense, phrase, sentence, themes. 2. Reduce the text to categories and code for words or patterns. A researcher can code for existence of meanings or words. 3. Explore the relationship between concepts: once the words are coded, the text can be analyzed for the following:

Strength of relationship: degree to which two or more concepts are related.

Sign of relationship: are concepts positively or negatively related to each other?

Direction of relationship: the types of relationship that categories exhibit. For example, “X implies Y” or “X occurs before Y” or “if X then Y” or if X is the primary motivator of Y.

4. Code the relationships: a difference between conceptual and relational analysis is that the statements or relationships between concepts are coded. 5. Perform statistical analyses: explore differences or look for relationships among the identified variables during coding. 6. Map out representations: such as decision mapping and mental models.

Reliability and Validity

Reliability : Because of the human nature of researchers, coding errors can never be eliminated but only minimized. Generally, 80% is an acceptable margin for reliability. Three criteria comprise the reliability of a content analysis:

Stability: the tendency for coders to consistently re-code the same data in the same way over a period of time.

Reproducibility: tendency for a group of coders to classify categories membership in the same way.

Accuracy: extent to which the classification of text corresponds to a standard or norm statistically.

Validity : Three criteria comprise the validity of a content analysis:

Closeness of categories: this can be achieved by utilizing multiple classifiers to arrive at an agreed upon definition of each specific category. Using multiple classifiers, a concept category that may be an explicit variable can be broadened to include synonyms or implicit variables.

Conclusions: What level of implication is allowable? Do conclusions correctly follow the data? Are results explainable by other phenomena? This becomes especially problematic when using computer software for analysis and distinguishing between synonyms. For example, the word “mine,” variously denotes a personal pronoun, an explosive device, and a deep hole in the ground from which ore is extracted. Software can obtain an accurate count of that word’s occurrence and frequency, but not be able to produce an accurate accounting of the meaning inherent in each particular usage. This problem could throw off one’s results and make any conclusion invalid.

Generalizability of the results to a theory: dependent on the clear definitions of concept categories, how they are determined and how reliable they are at measuring the idea one is seeking to measure. Generalizability parallels reliability as much of it depends on the three criteria for reliability.

Advantages of Content Analysis

Directly examines communication using text

Allows for both qualitative and quantitative analysis

Provides valuable historical and cultural insights over time

Allows a closeness to data

Coded form of the text can be statistically analyzed

Unobtrusive means of analyzing interactions

Provides insight into complex models of human thought and language use

When done well, is considered a relatively “exact” research method

Content analysis is a readily-understood and an inexpensive research method

A more powerful tool when combined with other research methods such as interviews, observation, and use of archival records. It is very useful for analyzing historical material, especially for documenting trends over time.

Disadvantages of Content Analysis

Can be extremely time consuming

Is subject to increased error, particularly when relational analysis is used to attain a higher level of interpretation

Is often devoid of theoretical base, or attempts too liberally to draw meaningful inferences about the relationships and impacts implied in a study

Is inherently reductive, particularly when dealing with complex texts

Tends too often to simply consist of word counts

Often disregards the context that produced the text, as well as the state of things after the text is produced

Can be difficult to automate or computerize

Textbooks & Chapters

Berelson, Bernard. Content Analysis in Communication Research.New York: Free Press, 1952.

Busha, Charles H. and Stephen P. Harter. Research Methods in Librarianship: Techniques and Interpretation.New York: Academic Press, 1980.

de Sola Pool, Ithiel. Trends in Content Analysis. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1959.

Krippendorff, Klaus. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1980.

Fielding, NG & Lee, RM. Using Computers in Qualitative Research. SAGE Publications, 1991. (Refer to Chapter by Seidel, J. ‘Method and Madness in the Application of Computer Technology to Qualitative Data Analysis’.)

Methodological Articles

Hsieh HF & Shannon SE. (2005). Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.Qualitative Health Research. 15(9): 1277-1288.

Elo S, Kaarianinen M, Kanste O, Polkki R, Utriainen K, & Kyngas H. (2014). Qualitative Content Analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. Sage Open. 4:1-10.

Application Articles

Abroms LC, Padmanabhan N, Thaweethai L, & Phillips T. (2011). iPhone Apps for Smoking Cessation: A content analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 40(3):279-285.

Ullstrom S. Sachs MA, Hansson J, Ovretveit J, & Brommels M. (2014). Suffering in Silence: a qualitative study of second victims of adverse events. British Medical Journal, Quality & Safety Issue. 23:325-331.

Owen P. (2012).Portrayals of Schizophrenia by Entertainment Media: A Content Analysis of Contemporary Movies. Psychiatric Services. 63:655-659.

Choosing whether to conduct a content analysis by hand or by using computer software can be difficult. Refer to ‘Method and Madness in the Application of Computer Technology to Qualitative Data Analysis’ listed above in “Textbooks and Chapters” for a discussion of the issue.

QSR NVivo: http://www.qsrinternational.com/products.aspx

Atlas.ti: http://www.atlasti.com/webinars.html

R- RQDA package: http://rqda.r-forge.r-project.org/

Rolly Constable, Marla Cowell, Sarita Zornek Crawford, David Golden, Jake Hartvigsen, Kathryn Morgan, Anne Mudgett, Kris Parrish, Laura Thomas, Erika Yolanda Thompson, Rosie Turner, and Mike Palmquist. (1994-2012). Ethnography, Observational Research, and Narrative Inquiry. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University. Available at: https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/guide.cfm?guideid=63 .

As an introduction to Content Analysis by Michael Palmquist, this is the main resource on Content Analysis on the Web. It is comprehensive, yet succinct. It includes examples and an annotated bibliography. The information contained in the narrative above draws heavily from and summarizes Michael Palmquist’s excellent resource on Content Analysis but was streamlined for the purpose of doctoral students and junior researchers in epidemiology.

At Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, more detailed training is available through the Department of Sociomedical Sciences- P8785 Qualitative Research Methods.

Join the Conversation

Have a question about methods? Join us on Facebook

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Content Analysis | A Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Amy Luo . Revised on 5 December 2022.

Content analysis is a research method used to identify patterns in recorded communication. To conduct content analysis, you systematically collect data from a set of texts, which can be written, oral, or visual:

- Books, newspapers, and magazines

- Speeches and interviews

- Web content and social media posts

- Photographs and films

Content analysis can be both quantitative (focused on counting and measuring) and qualitative (focused on interpreting and understanding). In both types, you categorise or ‘code’ words, themes, and concepts within the texts and then analyse the results.

Table of contents

What is content analysis used for, advantages of content analysis, disadvantages of content analysis, how to conduct content analysis.

Researchers use content analysis to find out about the purposes, messages, and effects of communication content. They can also make inferences about the producers and audience of the texts they analyse.

Content analysis can be used to quantify the occurrence of certain words, phrases, subjects, or concepts in a set of historical or contemporary texts.

In addition, content analysis can be used to make qualitative inferences by analysing the meaning and semantic relationship of words and concepts.

Because content analysis can be applied to a broad range of texts, it is used in a variety of fields, including marketing, media studies, anthropology, cognitive science, psychology, and many social science disciplines. It has various possible goals:

- Finding correlations and patterns in how concepts are communicated

- Understanding the intentions of an individual, group, or institution

- Identifying propaganda and bias in communication

- Revealing differences in communication in different contexts

- Analysing the consequences of communication content, such as the flow of information or audience responses

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

- Unobtrusive data collection

You can analyse communication and social interaction without the direct involvement of participants, so your presence as a researcher doesn’t influence the results.

- Transparent and replicable

When done well, content analysis follows a systematic procedure that can easily be replicated by other researchers, yielding results with high reliability .

- Highly flexible

You can conduct content analysis at any time, in any location, and at low cost. All you need is access to the appropriate sources.

Focusing on words or phrases in isolation can sometimes be overly reductive, disregarding context, nuance, and ambiguous meanings.

Content analysis almost always involves some level of subjective interpretation, which can affect the reliability and validity of the results and conclusions.

- Time intensive

Manually coding large volumes of text is extremely time-consuming, and it can be difficult to automate effectively.

If you want to use content analysis in your research, you need to start with a clear, direct research question .

Next, you follow these five steps.

Step 1: Select the content you will analyse

Based on your research question, choose the texts that you will analyse. You need to decide:

- The medium (e.g., newspapers, speeches, or websites) and genre (e.g., opinion pieces, political campaign speeches, or marketing copy)

- The criteria for inclusion (e.g., newspaper articles that mention a particular event, speeches by a certain politician, or websites selling a specific type of product)

- The parameters in terms of date range, location, etc.

If there are only a small number of texts that meet your criteria, you might analyse all of them. If there is a large volume of texts, you can select a sample .

Step 2: Define the units and categories of analysis

Next, you need to determine the level at which you will analyse your chosen texts. This means defining:

- The unit(s) of meaning that will be coded. For example, are you going to record the frequency of individual words and phrases, the characteristics of people who produced or appear in the texts, the presence and positioning of images, or the treatment of themes and concepts?

- The set of categories that you will use for coding. Categories can be objective characteristics (e.g., aged 30–40, lawyer, parent) or more conceptual (e.g., trustworthy, corrupt, conservative, family-oriented).

Step 3: Develop a set of rules for coding

Coding involves organising the units of meaning into the previously defined categories. Especially with more conceptual categories, it’s important to clearly define the rules for what will and won’t be included to ensure that all texts are coded consistently.

Coding rules are especially important if multiple researchers are involved, but even if you’re coding all of the text by yourself, recording the rules makes your method more transparent and reliable.

Step 4: Code the text according to the rules

You go through each text and record all relevant data in the appropriate categories. This can be done manually or aided with computer programs, such as QSR NVivo , Atlas.ti , and Diction , which can help speed up the process of counting and categorising words and phrases.

Step 5: Analyse the results and draw conclusions

Once coding is complete, the collected data is examined to find patterns and draw conclusions in response to your research question. You might use statistical analysis to find correlations or trends, discuss your interpretations of what the results mean, and make inferences about the creators, context, and audience of the texts.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Luo, A. (2022, December 05). Content Analysis | A Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 2 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/content-analysis-explained/

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked

How to do thematic analysis | guide & examples, data collection methods | step-by-step guide & examples, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods.

Chapter 17. Content Analysis

Introduction.

Content analysis is a term that is used to mean both a method of data collection and a method of data analysis. Archival and historical works can be the source of content analysis, but so too can the contemporary media coverage of a story, blogs, comment posts, films, cartoons, advertisements, brand packaging, and photographs posted on Instagram or Facebook. Really, almost anything can be the “content” to be analyzed. This is a qualitative research method because the focus is on the meanings and interpretations of that content rather than strictly numerical counts or variables-based causal modeling. [1] Qualitative content analysis (sometimes referred to as QCA) is particularly useful when attempting to define and understand prevalent stories or communication about a topic of interest—in other words, when we are less interested in what particular people (our defined sample) are doing or believing and more interested in what general narratives exist about a particular topic or issue. This chapter will explore different approaches to content analysis and provide helpful tips on how to collect data, how to turn that data into codes for analysis, and how to go about presenting what is found through analysis. It is also a nice segue between our data collection methods (e.g., interviewing, observation) chapters and chapters 18 and 19, whose focus is on coding, the primary means of data analysis for most qualitative data. In many ways, the methods of content analysis are quite similar to the method of coding.

Although the body of material (“content”) to be collected and analyzed can be nearly anything, most qualitative content analysis is applied to forms of human communication (e.g., media posts, news stories, campaign speeches, advertising jingles). The point of the analysis is to understand this communication, to systematically and rigorously explore its meanings, assumptions, themes, and patterns. Historical and archival sources may be the subject of content analysis, but there are other ways to analyze (“code”) this data when not overly concerned with the communicative aspect (see chapters 18 and 19). This is why we tend to consider content analysis its own method of data collection as well as a method of data analysis. Still, many of the techniques you learn in this chapter will be helpful to any “coding” scheme you develop for other kinds of qualitative data. Just remember that content analysis is a particular form with distinct aims and goals and traditions.

An Overview of the Content Analysis Process

The first step: selecting content.

Figure 17.2 is a display of possible content for content analysis. The first step in content analysis is making smart decisions about what content you will want to analyze and to clearly connect this content to your research question or general focus of research. Why are you interested in the messages conveyed in this particular content? What will the identification of patterns here help you understand? Content analysis can be fun to do, but in order to make it research, you need to fit it into a research plan.

Figure 17.1. A Non-exhaustive List of "Content" for Content Analysis

To take one example, let us imagine you are interested in gender presentations in society and how presentations of gender have changed over time. There are various forms of content out there that might help you document changes. You could, for example, begin by creating a list of magazines that are coded as being for “women” (e.g., Women’s Daily Journal ) and magazines that are coded as being for “men” (e.g., Men’s Health ). You could then select a date range that is relevant to your research question (e.g., 1950s–1970s) and collect magazines from that era. You might create a “sample” by deciding to look at three issues for each year in the date range and a systematic plan for what to look at in those issues (e.g., advertisements? Cartoons? Titles of articles? Whole articles?). You are not just going to look at some magazines willy-nilly. That would not be systematic enough to allow anyone to replicate or check your findings later on. Once you have a clear plan of what content is of interest to you and what you will be looking at, you can begin, creating a record of everything you are including as your content. This might mean a list of each advertisement you look at or each title of stories in those magazines along with its publication date. You may decide to have multiple “content” in your research plan. For each content, you want a clear plan for collecting, sampling, and documenting.

The Second Step: Collecting and Storing

Once you have a plan, you are ready to collect your data. This may entail downloading from the internet, creating a Word document or PDF of each article or picture, and storing these in a folder designated by the source and date (e.g., “ Men’s Health advertisements, 1950s”). Sølvberg ( 2021 ), for example, collected posted job advertisements for three kinds of elite jobs (economic, cultural, professional) in Sweden. But collecting might also mean going out and taking photographs yourself, as in the case of graffiti, street signs, or even what people are wearing. Chaise LaDousa, an anthropologist and linguist, took photos of “house signs,” which are signs, often creative and sometimes offensive, hung by college students living in communal off-campus houses. These signs were a focal point of college culture, sending messages about the values of the students living in them. Some of the names will give you an idea: “Boot ’n Rally,” “The Plantation,” “Crib of the Rib.” The students might find these signs funny and benign, but LaDousa ( 2011 ) argued convincingly that they also reproduced racial and gender inequalities. The data here already existed—they were big signs on houses—but the researcher had to collect the data by taking photographs.

In some cases, your content will be in physical form but not amenable to photographing, as in the case of films or unwieldy physical artifacts you find in the archives (e.g., undigitized meeting minutes or scrapbooks). In this case, you need to create some kind of detailed log (fieldnotes even) of the content that you can reference. In the case of films, this might mean watching the film and writing down details for key scenes that become your data. [2] For scrapbooks, it might mean taking notes on what you are seeing, quoting key passages, describing colors or presentation style. As you might imagine, this can take a lot of time. Be sure you budget this time into your research plan.

Researcher Note

A note on data scraping : Data scraping, sometimes known as screen scraping or frame grabbing, is a way of extracting data generated by another program, as when a scraping tool grabs information from a website. This may help you collect data that is on the internet, but you need to be ethical in how to employ the scraper. A student once helped me scrape thousands of stories from the Time magazine archives at once (although it took several hours for the scraping process to complete). These stories were freely available, so the scraping process simply sped up the laborious process of copying each article of interest and saving it to my research folder. Scraping tools can sometimes be used to circumvent paywalls. Be careful here!

The Third Step: Analysis

There is often an assumption among novice researchers that once you have collected your data, you are ready to write about what you have found. Actually, you haven’t yet found anything, and if you try to write up your results, you will probably be staring sadly at a blank page. Between the collection and the writing comes the difficult task of systematically and repeatedly reviewing the data in search of patterns and themes that will help you interpret the data, particularly its communicative aspect (e.g., What is it that is being communicated here, with these “house signs” or in the pages of Men’s Health ?).

The first time you go through the data, keep an open mind on what you are seeing (or hearing), and take notes about your observations that link up to your research question. In the beginning, it can be difficult to know what is relevant and what is extraneous. Sometimes, your research question changes based on what emerges from the data. Use the first round of review to consider this possibility, but then commit yourself to following a particular focus or path. If you are looking at how gender gets made or re-created, don’t follow the white rabbit down a hole about environmental injustice unless you decide that this really should be the focus of your study or that issues of environmental injustice are linked to gender presentation. In the second round of review, be very clear about emerging themes and patterns. Create codes (more on these in chapters 18 and 19) that will help you simplify what you are noticing. For example, “men as outdoorsy” might be a common trope you see in advertisements. Whenever you see this, mark the passage or picture. In your third (or fourth or fifth) round of review, begin to link up the tropes you’ve identified, looking for particular patterns and assumptions. You’ve drilled down to the details, and now you are building back up to figure out what they all mean. Start thinking about theory—either theories you have read about and are using as a frame of your study (e.g., gender as performance theory) or theories you are building yourself, as in the Grounded Theory tradition. Once you have a good idea of what is being communicated and how, go back to the data at least one more time to look for disconfirming evidence. Maybe you thought “men as outdoorsy” was of importance, but when you look hard, you note that women are presented as outdoorsy just as often. You just hadn’t paid attention. It is very important, as any kind of researcher but particularly as a qualitative researcher, to test yourself and your emerging interpretations in this way.

The Fourth and Final Step: The Write-Up

Only after you have fully completed analysis, with its many rounds of review and analysis, will you be able to write about what you found. The interpretation exists not in the data but in your analysis of the data. Before writing your results, you will want to very clearly describe how you chose the data here and all the possible limitations of this data (e.g., historical-trace problem or power problem; see chapter 16). Acknowledge any limitations of your sample. Describe the audience for the content, and discuss the implications of this. Once you have done all of this, you can put forth your interpretation of the communication of the content, linking to theory where doing so would help your readers understand your findings and what they mean more generally for our understanding of how the social world works. [3]

Analyzing Content: Helpful Hints and Pointers

Although every data set is unique and each researcher will have a different and unique research question to address with that data set, there are some common practices and conventions. When reviewing your data, what do you look at exactly? How will you know if you have seen a pattern? How do you note or mark your data?

Let’s start with the last question first. If your data is stored digitally, there are various ways you can highlight or mark up passages. You can, of course, do this with literal highlighters, pens, and pencils if you have print copies. But there are also qualitative software programs to help you store the data, retrieve the data, and mark the data. This can simplify the process, although it cannot do the work of analysis for you.

Qualitative software can be very expensive, so the first thing to do is to find out if your institution (or program) has a universal license its students can use. If they do not, most programs have special student licenses that are less expensive. The two most used programs at this moment are probably ATLAS.ti and NVivo. Both can cost more than $500 [4] but provide everything you could possibly need for storing data, content analysis, and coding. They also have a lot of customer support, and you can find many official and unofficial tutorials on how to use the programs’ features on the web. Dedoose, created by academic researchers at UCLA, is a decent program that lacks many of the bells and whistles of the two big programs. Instead of paying all at once, you pay monthly, as you use the program. The monthly fee is relatively affordable (less than $15), so this might be a good option for a small project. HyperRESEARCH is another basic program created by academic researchers, and it is free for small projects (those that have limited cases and material to import). You can pay a monthly fee if your project expands past the free limits. I have personally used all four of these programs, and they each have their pluses and minuses.

Regardless of which program you choose, you should know that none of them will actually do the hard work of analysis for you. They are incredibly useful for helping you store and organize your data, and they provide abundant tools for marking, comparing, and coding your data so you can make sense of it. But making sense of it will always be your job alone.

So let’s say you have some software, and you have uploaded all of your content into the program: video clips, photographs, transcripts of news stories, articles from magazines, even digital copies of college scrapbooks. Now what do you do? What are you looking for? How do you see a pattern? The answers to these questions will depend partially on the particular research question you have, or at least the motivation behind your research. Let’s go back to the idea of looking at gender presentations in magazines from the 1950s to the 1970s. Here are some things you can look at and code in the content: (1) actions and behaviors, (2) events or conditions, (3) activities, (4) strategies and tactics, (5) states or general conditions, (6) meanings or symbols, (7) relationships/interactions, (8) consequences, and (9) settings. Table 17.1 lists these with examples from our gender presentation study.

Table 17.1. Examples of What to Note During Content Analysis

One thing to note about the examples in table 17.1: sometimes we note (mark, record, code) a single example, while other times, as in “settings,” we are recording a recurrent pattern. To help you spot patterns, it is useful to mark every setting, including a notation on gender. Using software can help you do this efficiently. You can then call up “setting by gender” and note this emerging pattern. There’s an element of counting here, which we normally think of as quantitative data analysis, but we are using the count to identify a pattern that will be used to help us interpret the communication. Content analyses often include counting as part of the interpretive (qualitative) process.

In your own study, you may not need or want to look at all of the elements listed in table 17.1. Even in our imagined example, some are more useful than others. For example, “strategies and tactics” is a bit of a stretch here. In studies that are looking specifically at, say, policy implementation or social movements, this category will prove much more salient.

Another way to think about “what to look at” is to consider aspects of your content in terms of units of analysis. You can drill down to the specific words used (e.g., the adjectives commonly used to describe “men” and “women” in your magazine sample) or move up to the more abstract level of concepts used (e.g., the idea that men are more rational than women). Counting for the purpose of identifying patterns is particularly useful here. How many times is that idea of women’s irrationality communicated? How is it is communicated (in comic strips, fictional stories, editorials, etc.)? Does the incidence of the concept change over time? Perhaps the “irrational woman” was everywhere in the 1950s, but by the 1970s, it is no longer showing up in stories and comics. By tracing its usage and prevalence over time, you might come up with a theory or story about gender presentation during the period. Table 17.2 provides more examples of using different units of analysis for this work along with suggestions for effective use.

Table 17.2. Examples of Unit of Analysis in Content Analysis

Every qualitative content analysis is unique in its particular focus and particular data used, so there is no single correct way to approach analysis. You should have a better idea, however, of what kinds of things to look for and what to look for. The next two chapters will take you further into the coding process, the primary analytical tool for qualitative research in general.

Further Readings

Cidell, Julie. 2010. “Content Clouds as Exploratory Qualitative Data Analysis.” Area 42(4):514–523. A demonstration of using visual “content clouds” as a form of exploratory qualitative data analysis using transcripts of public meetings and content of newspaper articles.

Hsieh, Hsiu-Fang, and Sarah E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15(9):1277–1288. Distinguishes three distinct approaches to QCA: conventional, directed, and summative. Uses hypothetical examples from end-of-life care research.

Jackson, Romeo, Alex C. Lange, and Antonio Duran. 2021. “A Whitened Rainbow: The In/Visibility of Race and Racism in LGBTQ Higher Education Scholarship.” Journal Committed to Social Change on Race and Ethnicity (JCSCORE) 7(2):174–206.* Using a “critical summative content analysis” approach, examines research published on LGBTQ people between 2009 and 2019.

Krippendorff, Klaus. 2018. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology . 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. A very comprehensive textbook on both quantitative and qualitative forms of content analysis.

Mayring, Philipp. 2022. Qualitative Content Analysis: A Step-by-Step Guide . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Formulates an eight-step approach to QCA.

Messinger, Adam M. 2012. “Teaching Content Analysis through ‘Harry Potter.’” Teaching Sociology 40(4):360–367. This is a fun example of a relatively brief foray into content analysis using the music found in Harry Potter films.

Neuendorft, Kimberly A. 2002. The Content Analysis Guidebook . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Although a helpful guide to content analysis in general, be warned that this textbook definitely favors quantitative over qualitative approaches to content analysis.

Schrier, Margrit. 2012. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice . Thousand Okas, CA: SAGE. Arguably the most accessible guidebook for QCA, written by a professor based in Germany.

Weber, Matthew A., Shannon Caplan, Paul Ringold, and Karen Blocksom. 2017. “Rivers and Streams in the Media: A Content Analysis of Ecosystem Services.” Ecology and Society 22(3).* Examines the content of a blog hosted by National Geographic and articles published in The New York Times and the Wall Street Journal for stories on rivers and streams (e.g., water-quality flooding).

- There are ways of handling content analysis quantitatively, however. Some practitioners therefore specify qualitative content analysis (QCA). In this chapter, all content analysis is QCA unless otherwise noted. ↵

- Note that some qualitative software allows you to upload whole films or film clips for coding. You will still have to get access to the film, of course. ↵

- See chapter 20 for more on the final presentation of research. ↵

- . Actually, ATLAS.ti is an annual license, while NVivo is a perpetual license, but both are going to cost you at least $500 to use. Student rates may be lower. And don’t forget to ask your institution or program if they already have a software license you can use. ↵

A method of both data collection and data analysis in which a given content (textual, visual, graphic) is examined systematically and rigorously to identify meanings, themes, patterns and assumptions. Qualitative content analysis (QCA) is concerned with gathering and interpreting an existing body of material.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion