Featured Topics

View the Entrepreneurship Working Group page.

Econometrics

Microeconomics, macroeconomics, international economics, financial economics, public economics, health, education, and welfare, labor economics, industrial organization, development and growth, environmental and resource economics, regional and urban economics, more from nber.

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

Browse Econ Literature

- Working papers

- Software components

- Book chapters

- JEL classification

More features

- Subscribe to new research

RePEc Biblio

Author registration.

- Economics Virtual Seminar Calendar NEW!

Taylor & Francis Journals

Economic systems research.

- Publisher Info

- Serial Info

Corrections

Contact information of taylor & francis journals, serial information, impact factors.

- Simple ( last 10 years )

- Recursive ( 10 )

- Discounted ( 10 )

- Recursive discounted ( 10 )

- H-Index ( 10 )

- Euclid ( 10 )

- Aggregate ( 10 )

- By citations

- By downloads (last 12 months)

January 2024, Volume 36, Issue 1

October 2023, volume 35, issue 4, july 2023, volume 35, issue 3, april 2023, volume 35, issue 2, january 2023, volume 35, issue 1, october 2022, volume 34, issue 4, july 2022, volume 34, issue 3, april 2022, volume 34, issue 2, january 2022, volume 34, issue 1, october 2021, volume 33, issue 4, july 2021, volume 33, issue 3, april 2021, volume 33, issue 2, january 2021, volume 33, issue 1, october 2020, volume 32, issue 4, july 2020, volume 32, issue 3, april 2020, volume 32, issue 2, january 2020, volume 32, issue 1, october 2019, volume 31, issue 4, july 2019, volume 31, issue 3, april 2019, volume 31, issue 2, january 2019, volume 31, issue 1, october 2018, volume 30, issue 4, july 2018, volume 30, issue 3, april 2018, volume 30, issue 2, january 2018, volume 30, issue 1, october 2017, volume 29, issue 4, july 2017, volume 29, issue 3, april 2017, volume 29, issue 2, more services and features.

Follow serials, authors, keywords & more

Public profiles for Economics researchers

Various research rankings in Economics

RePEc Genealogy

Who was a student of whom, using RePEc

Curated articles & papers on economics topics

Upload your paper to be listed on RePEc and IDEAS

New papers by email

Subscribe to new additions to RePEc

EconAcademics

Blog aggregator for economics research

Cases of plagiarism in Economics

About RePEc

Initiative for open bibliographies in Economics

News about RePEc

Questions about IDEAS and RePEc

RePEc volunteers

Participating archives

Publishers indexing in RePEc

Privacy statement

Found an error or omission?

Opportunities to help RePEc

Get papers listed

Have your research listed on RePEc

Open a RePEc archive

Have your institution's/publisher's output listed on RePEc

Get RePEc data

Use data assembled by RePEc

- Library Guides

Economics Research Methods

- Let's Get Started!

- Practice: How to Generate Keywords

- What Literature to Search

- Finding Articles

- Handbooks in Economics This link opens in a new window

- Working Papers

- Data Sources

- Data Sources, Part 2

- Extending Your Searching with Citation Chains

- Forward Citation Chains - Cited Reference Searching

- Managing Your Research - Endnote Web

Graduate College Resources

Here are some essential resources provided by the Graduate College:

- Dissertation and Thesis Information

- Center for Communication Excellence

- Graduate College Handbook

Introduction to Research Methods

Research methods help you as a researcher answer a specific economic questions The first step in becoming a proficient researcher is to build some skills in finding, evaluating and using academic literature. Research in economics, as in any other academic field,builds on the work of previous researchers. A literature review is a important first step when beginning a research project to get an sense of what research has already been done on the topic.

A literature review is a survey of existing literature that provides context for your research contribution, and demonstrates your subject knowledge. It is also the way to tell the story of how your research extends knowledge in your field.

The first step to writing a successful literature review is knowing how to find and evaluate literature on your topic.This guide is designed to introduce you to tools and give you skills you can use to effectively do economics research..

Below are some questions to think about as you begin your research:

Questions to ask as you think about your literature review:

What is my research question.

Choosing a valid research question is something you will need to discuss with your academic advisor and/or POS committee. Ideas for your topic may come from your coursework, lab rotations, or work as a research assistant. Having a specific research topic allows you to focus your research on a project that is manageable. Beginning work on your literature review can help narrow your topic.

What kind of literature review is appropriate for my research question?

Depending on your area of research, the type of literature review you do for your thesis will vary. Consult with your advisor about the requirements for your discipline. You can view theses and dissertations from your field in the library's Digital Repository can give you ideas about how your literature review should be structured.

What kind of literature should I use?

The kind of literature you use for your thesis will depend on your discipline. The Library has developed a list of Guides by Subject with discipline-specific resources. For a given subject area, look for the guide titles "[Discipline] Research Guide." You may also consult our liaison librarians for information about the literature available your research area.

How will I make sure that I find all the appropriate information that informs my research?

Consulting multiple sources of information is the best way to insure that you have done a comprehensive search of the literature in your area. The What Literature to Search tab has information about the types of resources you may need to search. You may also consult our liaison librarians for assistance with identifying resources..

How will I evaluate the literature to include trustworthy information and eliminate unnecessary or untrustworthy information?

While you are searching for relevant information about your topic you will need to think about the accuracy of the information, whether the information is from a reputable source, whether it is objective and current. Our guides about Evaluating Scholarly Books and Articles and Evaluating Websites will give you criteria to use when evaluating resources.

How should I organize my literature? What citation management program is best for me?

Citation management software can help you organize your references in folders and/or with tags. You can also annotate and highlight the PDFs within the software and usually the notes are searchable. To choose a good citation management software, you need to consider which one can be streamlined with your literature search and writing process. Here is a guide page comparing EndNote, Mendeley & Zotero. The Library also has guides for three of the major citation management tools:

- EndNote & EndNote Web Guide

- Mendeley Guide

- Getting Started with Zotero

What steps should I take to ensure academic integrity?

The best way to ensure academic integrity is to familiarize yourself with different types of intentional and unintentional plagiarism and learn about the University's standards for academic integrity. Start with this guide . The Library also has a guide about your rights and responsibilities regarding copyrighted images and figures that you include in your thesis.

Where can I find writing and editing help?

Writing and editing help is available at the Graduate College's Center for Communication Excellence . The CCE offers individual consultations, peer writing groups, workshops and seminars to help you improve your writing.

Where can I find I find formatting standards? Technical support?

The Graduate College has a Dissertation/ Thesis website with extensive examples and videos about formatting theses and dissertations. The site also has templates and formatting instructions for Word and LaTex .

What citation style should I use?

The Graduate College thesis guidelines require that you "use a consistent, current academic style for your discipline." The Library has a Citation Style Guides resource you can use for guidance on specific citation styles. If you are not sure, please consult your advisor or liaison librarians for help.

Adapted from The Literature Review: For Dissertations, by the University of Michigan Library. Available: https://guides.lib.umich.edu/dissertationlitreview

Presentation Slides

Slides from the ECON 594X class presentation" held on October 7, 2020 are below:

- ECON 594X Class presentation slides

Your Librarian

- Next: Developing a Search Strategy >>

The library's collections and services are available to all ISU students, faculty, and staff and Parks Library is open to the public .

- Last Updated: Apr 17, 2024 12:55 PM

- URL: https://instr.iastate.libguides.com/econresearch

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Economics →

- 11 Apr 2024

- In Practice

Why Progress on Immigration Might Soften Labor Pains

Long-term labor shortages continue to stoke debates about immigration policy in the United States. We asked Harvard Business School faculty members to discuss what's at stake for companies facing talent needs, and the potential scenarios on the horizon.

- 01 Apr 2024

Navigating the Mood of Customers Weary of Price Hikes

Price increases might be tempering after historic surges, but companies continue to wrestle with pinched consumers. Alexander MacKay, Chiara Farronato, and Emily Williams make sense of the economic whiplash of inflation and offer insights for business leaders trying to find equilibrium.

- 29 Jan 2024

- Research & Ideas

Do Disasters Rally Support for Climate Action? It's Complicated.

Reactions to devastating wildfires in the Amazon show the contrasting realities for people living in areas vulnerable to climate change. Research by Paula Rettl illustrates the political ramifications that arise as people weigh the economic tradeoffs of natural disasters.

- 10 Jan 2024

Technology and COVID Upended Tipping Norms. Will Consumers Keep Paying?

When COVID pushed service-based businesses to the brink, tipping became a way for customers to show their appreciation. Now that the pandemic is over, new technologies have enabled companies to maintain and expand the use of digital payment nudges, says Jill Avery.

- 17 Aug 2023

‘Not a Bunch of Weirdos’: Why Mainstream Investors Buy Crypto

Bitcoin might seem like the preferred tender of conspiracy theorists and criminals, but everyday investors are increasingly embracing crypto. A study of 59 million consumers by Marco Di Maggio and colleagues paints a shockingly ordinary picture of today's cryptocurrency buyer. What do they stand to gain?

- 15 Aug 2023

Why Giving to Others Makes Us Happy

Giving to others is also good for the giver. A research paper by Ashley Whillans and colleagues identifies three circumstances in which spending money on other people can boost happiness.

- 13 Mar 2023

What Would It Take to Unlock Microfinance's Full Potential?

Microfinance has been seen as a vehicle for economic mobility in developing countries, but the results have been mixed. Research by Natalia Rigol and Ben Roth probes how different lending approaches might serve entrepreneurs better.

- 23 Jan 2023

After High-Profile Failures, Can Investors Still Trust Credit Ratings?

Rating agencies, such as Standard & Poor’s and Moody's, have been criticized for not warning investors of risks that led to major financial catastrophes. But an analysis of thousands of ratings by Anywhere Sikochi and colleagues suggests that agencies have learned from past mistakes.

- 29 Nov 2022

How Much More Would Holiday Shoppers Pay to Wear Something Rare?

Economic worries will make pricing strategy even more critical this holiday season. Research by Chiara Farronato reveals the value that hip consumers see in hard-to-find products. Are companies simply making too many goods?

- 21 Nov 2022

Buy Now, Pay Later: How Retail's Hot Feature Hurts Low-Income Shoppers

More consumers may opt to "buy now, pay later" this holiday season, but what happens if they can't make that last payment? Research by Marco Di Maggio and Emily Williams highlights the risks of these financing services, especially for lower-income shoppers.

- 01 Sep 2022

- What Do You Think?

Is It Time to Consider Lifting Tariffs on Chinese Imports?

Many of the tariffs levied by the Trump administration on Chinese goods remain in place. James Heskett weighs whether the US should prioritize renegotiating trade agreements with China, and what it would take to move on from the trade war. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 05 Jul 2022

Have We Seen the Peak of Just-in-Time Inventory Management?

Toyota and other companies have harnessed just-in-time inventory management to cut logistics costs and boost service. That is, until COVID-19 roiled global supply chains. Will we ever get back to the days of tighter inventory control? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 09 Mar 2022

War in Ukraine: Soaring Gas Prices and the Return of Stagflation?

With nothing left to lose, Russia's invasion of Ukraine will likely intensify, roiling energy markets further and raising questions about the future of globalization, says Rawi Abdelal. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 10 Feb 2022

Why Are Prices So High Right Now—and Will They Ever Return to Normal?

And when will sold-out products return to store shelves? The answers aren't so straightforward. Research by Alberto Cavallo probes the complex interplay of product shortages, prices, and inflation. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 11 Jan 2022

- Cold Call Podcast

Can Entrepreneurs and Governments Team Up to Solve Big Problems?

In 2017, Shield AI’s quadcopter, with no pilot and no flight plan, could clear a building and outpace human warfighters by almost five minutes. It was evidence that autonomous robots could help protect civilian and service member lives. But was it also evidence that Shield AI—a startup barely two years past founding—could ask their newest potential customer, the US government, for a large contract for a system of coordinated, exploring robots? Or would it scare them away? Harvard Business School professor Mitch Weiss and Brandon Tseng, Shield AI’s CGO and co-founder, discuss these and other challenges entrepreneurs face when working with the public sector, and how investing in new ideas can enable entrepreneurs and governments to join forces and solve big problems in the case, “Shield AI.” Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 06 May 2021

How Four Women Made Miami More Equitable for Startups

A case study by Rosabeth Moss Kanter examines what it takes to break gender barriers and build thriving businesses in an emerging startup hub. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 20 Apr 2021

- Working Paper Summaries

The Emergence of Mafia-like Business Systems in China

This study sheds light on the political pathology of fraudulent, illegal, and corrupt business practices. Features of the Chinese system—including regulatory gaps, a lack of formal means of property protection, and pervasive uncertainty—seem to facilitate the rise of mafia systems.

- 02 Feb 2021

Nonprofits in Good Times and Bad Times

Tax returns from millions of US nonprofits reveal that charities do not expand during bad times, when need is the greatest. Although they are able to smooth the swings of their activities more than for-profit organizations, nonprofits exhibit substantial sensitivity to economic cycles.

- 01 Feb 2021

Has the New Economy Finally Arrived?

Economists have long tied low unemployment to inflation. James Heskett considers whether the US economic policy of the past four years has shaken those assumptions. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 06 Jan 2021

Aggregate Advertising Expenditure in the US Economy: What's Up? Is It Real?

We analyze total United States advertising spending from 1960 to 2018. In nominal terms, the elasticity of annual advertising outlays with respect to gross domestic product appears to have increased substantially beginning in the late 1990s, roughly coinciding with the dramatic growth of internet-based advertising.

400+ Economic Project Topics: How to Choose and Excel in Research

Economic project topics play a pivotal role in the academic journey of students pursuing degrees in economics or related fields. These topics serve as the foundation for research, analysis, and the development of critical thinking skills.

Selecting the right economic project topic is crucial, as it can significantly impact the success of your research and the depth of your understanding of economic principles.

In this blog, we’ll guide you through the process of choosing the right economic project topic, explore different categories of topics, and provide tips for a successful research journey.

How To Select Economic Project Topics?

Table of Contents

Before diving into the categories of economic project topics, it’s essential to understand the process of selecting a topic that aligns with your interests, expertise, and available resources. Here’s a closer look at how to choose the right topic:

Identifying Your Interests and Expertise

Passion for your research topic can be a powerful motivator. Consider areas within economics that genuinely interest you.

Do you have a fascination with microeconomic concepts like market dynamics and consumer behavior, or are you more drawn to macroeconomic issues like fiscal and monetary policies? Identifying your interests will make the research process more enjoyable and rewarding.

Moreover, leveraging your expertise can lead to a more fruitful research experience. If you have a background in a specific industry or possess unique skills, it may be wise to select a topic that aligns with your strengths.

Your existing knowledge can provide valuable insights and a competitive edge in your research.

Assessing the Relevance and Timeliness of Topics

Economic research should address current and relevant issues in the field. To ensure the significance of your project, consider the timeliness of the topic.

Are you exploring an emerging economic trend, or does your research address a longstanding issue that still requires attention?

Additionally, think about the broader implications of your research. How does your chosen topic contribute to the existing body of knowledge in economics?

Assessing the relevance and potential impact of your research can help you choose a topic that resonates with both academic and real-world audiences.

Considering Available Resources and Data

Practicality is a crucial factor in selecting an economic project topic. Assess the availability of resources and data required for your research. Do you have access to relevant datasets, surveys, or academic journals that support your chosen topic?

It’s essential to ensure that the necessary resources are accessible to facilitate your research process effectively.

400+ Economic Project Topics: Category-Wise

Economic project topics encompass a wide range of areas within the field. Here are four major categories to explore:

100+ Microeconomics Project Topics

- The impact of advertising on consumer behavior.

- Price elasticity of demand for luxury goods.

- Analyzing market structure in the tech industry.

- Consumer preferences for sustainable products.

- The economics of online streaming services.

- Factors affecting pricing strategies in the airline industry.

- The role of information asymmetry in used car markets.

- Microeconomics of fast fashion and its environmental effects.

- Behavioral economics in food choices and obesity.

- The impact of minimum wage on small businesses.

- Market competition and pharmaceutical drug prices.

- Monopoly power in the pharmaceutical industry.

- Economic analysis of the gig economy.

- Elasticity of demand for healthcare services.

- Price discrimination in the hotel industry.

- Consumer behavior in the sharing economy.

- Economic analysis of e-commerce marketplaces.

- The economics of ride-sharing services like Uber.

- Factors influencing the demand for organic foods.

- Game theory and strategic pricing in oligopolistic markets.

- Microeconomics of the coffee industry.

- Analyzing the effects of tariffs on imported goods.

- Price elasticity of demand for electric vehicles.

- The economics of artificial intelligence and job displacement.

- Behavioral economics in the stock market.

- Impact of advertising on children’s consumer choices.

- Monopolistic competition in the smartphone industry.

- Economic analysis of the video game industry.

- The role of patents in pharmaceutical pricing.

- Price discrimination in the airline industry.

- Analyzing consumer behavior in the luxury fashion industry.

- The economics of addiction and substance abuse.

- Market structure in the online advertising industry.

- Price elasticity of demand for energy-efficient appliances.

- Economic analysis of the fast-food industry.

- The impact of product recalls on consumer trust.

- Factors influencing consumer choices in the beer industry.

- Microeconomics of the music streaming industry.

- Behavioral economics and food labeling.

- Economic analysis of the fitness and wellness industry.

- The economics of organic farming and sustainability.

- Analyzing the demand for mobile app-based services.

- Price discrimination in the entertainment industry.

- Economic analysis of subscription box services.

- Consumer preferences for eco-friendly packaging.

- Game theory in online auction markets.

- Analyzing the effects of congestion pricing.

- The economics of university tuition and student loans.

- Microeconomics of the fashion resale market.

- Behavioral economics in online shopping cart abandonment.

- Market structure in the pharmaceutical distribution.

- Analyzing the economics of cryptocurrency.

- Economic analysis of the real estate market.

- Price elasticity of demand for streaming music services.

- Consumer choices in the electric vehicle market.

- The economics of food delivery services.

- Monopoly power in the cable television industry.

- Factors influencing consumer decisions in the cosmetics industry.

- Behavioral economics and charitable donations.

- Economic analysis of the online dating industry.

- The impact of healthcare regulations on prices.

- Price discrimination in the cruise line industry.

- Economic analysis of the fashion resale market.

- Analyzing the effects of subsidies on agriculture.

- Consumer preferences for eco-friendly transportation.

- Market structure in the book publishing industry.

- Microeconomics of the craft beer industry.

- Behavioral economics and impulse buying.

- Price elasticity of demand for video game consoles.

- Economic analysis of the coffee shop industry.

- The economics of mobile payment systems.

- Analyzing consumer choices in the fast-food breakfast market.

- Monopolistic competition in the smartphone app industry.

- Factors influencing consumer decisions in the beauty industry.

- Behavioral economics in the context of online reviews.

- Economic analysis of the organic skincare industry.

- The impact of government regulations on tobacco prices.

- Price discrimination in the movie theater industry.

- Microeconomics of the subscription box industry.

- Analyzing the effects of trade barriers on agricultural exports.

- Consumer preferences for sustainable fashion.

- Market structure in the video game console industry.

- The economics of mobile app monetization.

- Price elasticity of demand for streaming television services.

- Economic analysis of the organic food industry.

- Behavioral economics and the psychology of pricing.

- Analyzing consumer choices in the electric scooter market.

- Monopoly power in the cable internet service industry.

- Factors influencing consumer decisions in the wine industry.

- Economic analysis of the impact of product reviews on sales.

- The economics of online crowdfunding platforms.

- Price discrimination in the music festival industry.

- Microeconomics of the meal kit delivery industry.

- Behavioral economics and the impact of discounts on purchasing behavior.

- Analyzing the effects of trade agreements on global supply chains.

- Consumer preferences for sustainable home appliances.

- Market structure in the online marketplace for handmade goods.

- The economics of esports and gaming tournaments.

- Price elasticity of demand for online streaming subscriptions.

- Economic analysis of the fast-casual restaurant industry.

- The impact of government subsidies on renewable energy prices.

100+ Macroeconomics Project Topics

- The impact of fiscal policy on economic growth.

- Analyzing the effectiveness of monetary policy.

- Inflation targeting and its implications.

- The relationship between unemployment and inflation.

- Factors influencing exchange rates.

- The effects of globalization on income inequality.

- Assessing the economic consequences of trade wars.

- The role of central banks in financial stability.

- Economic growth in emerging markets.

- Government debt and its impact on the economy.

- The economics of healthcare reform.

- Income distribution and poverty alleviation strategies.

- The economics of renewable energy adoption.

- The impact of automation on employment.

- Economic consequences of climate change.

- The economics of the gig economy.

- The Phillips Curve and its modern relevance.

- The economics of housing bubbles.

- Economic development in sub-Saharan Africa.

- The economics of education funding.

- The impact of technology on productivity growth.

- The role of the IMF in global financial stability.

- Economic consequences of Brexit.

- The economics of cryptocurrency.

- Economic implications of aging populations.

- The economics of natural disasters.

- The effects of income tax cuts on the economy.

- The relationship between economic freedom and growth.

- The role of infrastructure investment in economic development.

- The economics of health insurance markets.

- The impact of minimum wage laws on employment.

- The economics of food security.

- The effects of government subsidies on industries.

- The role of the World Bank in global development.

- Economic consequences of government regulation.

- The economics of corporate mergers.

- The relationship between government spending and economic growth.

- Economic effects of monetary policy on asset prices.

- The economics of social safety nets.

- The impact of income inequality on economic growth.

- The role of entrepreneurship in economic development.

- Economic consequences of trade deficits.

- The effects of financial deregulation.

- The economics of the opioid crisis.

- The relationship between economic growth and environmental sustainability.

- The impact of tax evasion on government revenue.

- Economic development in post-conflict regions.

- The economics of the sharing economy.

- The role of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in international trade.

- Economic consequences of government debt crises.

- The effects of population aging on healthcare systems.

- The economics of public-private partnerships.

- The impact of economic sanctions on countries.

- Economic implications of income tax reform.

- The role of venture capital in innovation.

- The economics of foreign aid.

- The relationship between education and economic growth.

- Economic effects of natural resource extraction.

- The economics of financial market crashes.

- The role of economic incentives in behavior.

- Economic consequences of currency devaluation.

- The effects of income tax progressivity on income distribution.

- The economics of income mobility.

- The impact of government subsidies on renewable energy.

- Economic development in post-communist countries.

- The economics of intellectual property rights.

- The relationship between government corruption and economic growth.

- Economic consequences of government budget deficits.

- The effects of financial globalization.

- The role of behavioral economics in policy-making.

- The economics of healthcare access.

- The impact of automation on manufacturing jobs.

- Economic implications of population growth.

- The economics of housing affordability.

- The relationship between monetary policy and asset bubbles.

- Economic effects of immigration policies.

- The role of economic forecasting in decision-making.

- The economics of taxation on multinational corporations.

- Economic development in the digital age.

- The impact of economic shocks on consumer behavior.

- Economic consequences of natural disasters.

- The effects of income inequality on social cohesion.

- The economics of financial innovation.

- The relationship between economic freedom and entrepreneurship.

- Economic implications of healthcare reform.

- The role of gender inequality in economic development.

- The economics of climate change mitigation.

- The impact of government regulations on small businesses.

- Economic development in the Middle East.

- The economics of consumer debt.

- The relationship between trade policy and national security.

- Economic consequences of housing market crashes.

- The effects of monetary policy on income distribution.

- The economics of sustainable agriculture.

- The role of economic sanctions in international diplomacy.

- Economic implications of corporate tax reform.

- The economics of innovation clusters.

- The impact of government procurement policies on industries.

- Economic development in post-apartheid South Africa.

- The relationship between economic inequality and political instability.

100+ International Economics Project Topics

- Impact of Trade Wars on Global Economies

- Exchange Rate Determinants and Fluctuations

- The Role of Multinational Corporations in International Trade

- Effects of Brexit on International Trade

- Comparative Analysis of Free Trade Agreements

- Currency Manipulation and Its Consequences

- Economic Integration in the European Union

- Global Supply Chains and Vulnerabilities

- The Impact of China’s Belt and Road Initiative

- Trade Liberalization in Developing Countries

- Globalization and Income Inequality

- Economic Consequences of Economic Sanctions

- International Trade and Environmental Sustainability

- The Role of the World Trade Organization (WTO)

- Foreign Direct Investment and Economic Growth

- Exchange Rate Regimes: Fixed vs. Floating

- International Financial Crises and Their Causes

- NAFTA vs. USMCA: A Comparative Analysis

- The Effects of Tariffs on Import-Dependent Industries

- Trade and Economic Development in Africa

- Offshoring and Outsourcing in a Global Economy

- The Economics of Remittances

- Currency Wars and Competitive Devaluations

- International Trade and Intellectual Property Rights

- The Impact of Economic Openness on Inflation

- The Eurozone Crisis: Causes and Solutions

- Trade Imbalances and Their Consequences

- The Economics of International Migration

- Exchange Rate Volatility and Speculation

- The Silk Road: Historical and Modern Perspectives

- The Role of International Aid in Development

- Globalization and Cultural Homogenization

- International Trade and National Security

- The Economic Effects of Brexit on the EU

- Sovereign Debt Crises and Bailouts

- The Economics of Global Energy Markets

- International Trade and Human Rights

- The Asian Financial Crisis of 1997

- The Economics of International Tourism

- The Impact of Global Economic Institutions

- International Trade and Technological Innovation

- Comparative Advantage and Trade Theory

- Globalization and Income Redistribution

- International Trade and Agriculture

- The BRICS Countries in the Global Economy

- Exchange Rate Pegs and Currency Boards

- The Economics of Global Health Challenges

- International Trade and Gender Inequality

- The Effects of Economic Migration on Sending and Receiving Countries

- The Role of Non-Tariff Barriers in International Trade

- International Trade and Economic Development in Latin America

- The European Debt Crisis and Austerity Measures

- Globalization and Income Mobility

- The Impact of International Trade on Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs)

- The Economics of Regional Integration: ASEAN, Mercosur, etc.

- Trade Agreements and Dispute Resolution

- Exchange Rate Forecasting Models

- The Economics of Foreign Aid Allocation

- The Role of International Trade in Poverty Alleviation

- International Trade and Economic Freedom

- The Economics of International Banking

- Globalization and Income Convergence

- The Effects of Political Instability on International Trade

- Trade and Economic Development in South Asia

- The Role of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in Trade

- International Trade and Labor Standards

- Economic Consequences of Trade Deficits

- The Economics of International Taxation

- Trade and Economic Development in the Middle East

- Globalization and Income Polarization

- The Impact of Global Value Chains (GVCs) on Trade

- International Trade and Health Care Systems

- The Economics of Bilateral vs. Multilateral Trade Agreements

- Trade and Economic Development in Southeast Asia

- Exchange Rate Parity Conditions

- The Economics of International Migration Policies

- The Role of Trade Facilitation Measures

- International Trade and Human Capital Development

- Globalization and Income Insecurity

- The Effects of Trade on Environmental Sustainability

- The Economics of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) Incentives

- Trade and Economic Development in Eastern Europe

- The Role of Export Credit Agencies (ECAs) in Trade

- International Trade and Technological Transfer

- Globalization and Income Resilience

- The Impact of Global Economic Shocks

- Trade and Economic Development in Oceania

- Exchange Rate Risk Management Strategies

- The Economics of Foreign Exchange Reserves

- International Trade and Economic Geography

- The Role of Trade Promotion Agencies

- Globalization and Income Diversity

- The Effects of Exchange Rate Intervention

- International Trade and Financial Inclusion

- Trade and Economic Development in the Caribbean

- The Economics of Trade Agreements on Services

- The Role of Export Processing Zones (EPZs) in Trade

- International Trade and Income Mobility

- Globalization and Income Equality Policies

- The Impact of Trade Disputes on International Relations.

100+ Economic Policy Project Topics

- The impact of minimum wage laws on employment rates.

- The effectiveness of quantitative easing in stimulating economic growth.

- Analyzing the consequences of trade tariffs on international commerce.

- The role of government subsidies in shaping agricultural markets.

- The economic implications of healthcare reform policies.

- Examining the relationship between income inequality and economic growth.

- Evaluating the effects of corporate tax cuts on business investments.

- The impact of immigration policies on labor markets.

- Analyzing the economic consequences of climate change regulations.

- Assessing the effectiveness of financial regulations in preventing economic crises.

- The role of central banks in controlling inflation.

- The economic implications of universal basic income programs.

- Investigating the relationship between education spending and economic development.

- The impact of government debt on future generations.

- Analyzing the effects of fiscal stimulus packages on economic recovery.

- The role of monetary policy in addressing unemployment.

- Evaluating the economic consequences of government healthcare programs.

- The impact of exchange rate fluctuations on international trade.

- The economic implications of public-private partnerships in infrastructure development.

- Analyzing the effects of antitrust laws on competition in markets.

- The role of social welfare programs in poverty reduction.

- Evaluating the economic consequences of aging populations.

- The impact of housing policies on real estate markets.

- Investigating the relationship between foreign aid and economic development.

- The economic implications of globalization on income distribution.

- Analyzing the effects of regulatory capture in financial markets.

- The role of tax incentives in promoting renewable energy.

- Evaluating the economic consequences of healthcare privatization.

- The impact of immigration reform on labor market dynamics.

- Investigating the relationship between government debt and interest rates.

- The economic implications of trade liberalization agreements.

- Analyzing the effects of corporate social responsibility on profitability.

- The role of fiscal policy in addressing economic recessions.

- Evaluating the economic consequences of income tax reforms.

- The impact of technology policies on innovation and economic growth.

- Investigating the relationship between monetary policy and asset bubbles.

- The economic implications of minimum wage adjustments.

- Analyzing the effects of government regulations on the pharmaceutical industry.

- The role of foreign direct investment in economic development.

- Evaluating the economic consequences of healthcare cost containment measures.

- The impact of labor market policies on workforce participation.

- Investigating the relationship between exchange rates and export competitiveness.

- The economic implications of intellectual property rights protection.

- Analyzing the effects of fiscal austerity measures on economic stability.

- The role of government spending in stimulating economic growth.

- Evaluating the economic consequences of energy subsidies.

- The impact of trade agreements on job displacement.

- Investigating the relationship between infrastructure investment and productivity.

- The economic implications of financial market deregulation.

- Analyzing the effects of income tax credits on low-income families.

- The role of social safety nets in mitigating economic shocks.

- Evaluating the economic consequences of healthcare rationing.

- The impact of labor market flexibility on employment stability.

- Investigating the relationship between corporate governance and firm performance.

- The economic implications of government subsidies for renewable energy.

- Analyzing the effects of taxation on wealth distribution.

- The role of sovereign wealth funds in economic development.

- Evaluating the economic consequences of currency devaluation.

- The impact of government regulation on the gig economy.

- Investigating the relationship between foreign aid and political stability.

- The economic implications of healthcare privatization.

- Analyzing the effects of income inequality on social cohesion.

- The role of infrastructure investment in reducing transportation costs.

- Evaluating the economic consequences of carbon pricing policies.

- The impact of trade protectionism on domestic industries.

- Investigating the relationship between public education funding and student outcomes.

- The economic implications of housing affordability challenges.

- Analyzing the effects of labor market discrimination on wage gaps.

- The role of monetary policy in addressing asset price bubbles.

- Evaluating the economic consequences of financial market speculation.

- The impact of government procurement policies on small businesses.

- Investigating the relationship between population aging and healthcare expenditures.

- The economic implications of regional economic integration.

- Analyzing the effects of government subsidies on agricultural sustainability.

- The role of tax incentives in promoting technology startups.

- Evaluating the economic consequences of trade imbalances.

- The impact of healthcare cost containment measures on patient outcomes.

- Investigating the relationship between government debt and economic growth.

- The economic implications of housing market speculation.

- Analyzing the effects of labor unions on wage negotiations.

- The role of economic sanctions in shaping international relations.

- Evaluating the economic consequences of natural resource depletion.

- The impact of fiscal policy on income redistribution.

- Investigating the relationship between education quality and workforce productivity.

- The economic implications of government investment in green infrastructure.

- Analyzing the effects of income tax evasion on government revenue.

- The role of gender-based economic disparities in overall growth.

- Evaluating the economic consequences of healthcare fraud.

- The impact of public transportation policies on urban development.

- Investigating the relationship between corporate social responsibility and consumer behavior.

- The economic implications of government support for the arts and culture sector.

- Analyzing the effects of government subsidies on electric vehicles.

- The role of economic diplomacy in promoting international trade.

- Evaluating the economic consequences of financial market volatility.

- The impact of globalization on wage convergence or divergence.

- Investigating the relationship between economic sanctions and human rights violations.

- The economic implications of government investments in digital infrastructure.

- Analyzing the effects of government interventions in housing markets.

- The role of economic policies in addressing income mobility.

- Evaluating the economic consequences of occupational licensing regulations.

Popular Economic Project Topics

To inspire your research journey, here are some popular economic project topics within each category:

- Case Studies

1. Analyzing the Impact of COVID-19 on a Specific Industry: Examine how the pandemic affected industries like hospitality, aviation, or e-commerce.

2. Evaluating the Economic Effects of Tax Reforms: Investigate the consequences of recent tax policy changes on businesses, individuals, and government revenue.

- Research-Based Topics

1. Exploring the Relationship Between Inflation and Unemployment: Conduct empirical research to analyze the Phillips Curve and its relevance in the modern economy.

2. Investigating the Factors Influencing Consumer Spending Patterns: Use surveys and data analysis to understand what drives consumer spending behavior.

- Policy Analysis

1. Assessing the Effectiveness of a Recent Economic Stimulus Package: Evaluate the impact of government stimulus measures on economic recovery, employment, and inflation.

2. Examining the Pros and Cons of Minimum Wage Adjustments: Analyze the economic effects of changes in the minimum wage on low-wage workers, businesses, and overall employment.

Research Methodologies: Economic Project Topics

The methodology you choose for your economic project can significantly impact the outcomes of your research. Here are some common research approaches:

- Quantitative Research

Quantitative research involves collecting and analyzing numerical data. Common methods include:

1. Surveys and Questionnaires: Conduct surveys to gather data from respondents and use statistical analysis to draw conclusions.

2. Data Analysis and Regression Models: Employ statistical software to analyze datasets and establish relationships between variables using regression analysis.

- Qualitative Research

Qualitative research focuses on understanding the underlying reasons, motivations, and perceptions of individuals or groups. Common methods include:

1. Interviews and Focus Groups: Conduct interviews or group discussions to gain insights into specific economic behaviors or attitudes.

2. Content Analysis: Analyze textual or visual data, such as documents, reports, or media, to identify themes and patterns.

- Mixed-Methods Research

Mixed-methods research combines both quantitative and qualitative approaches to provide a comprehensive understanding of economic phenomena. Researchers often collect numerical data alongside qualitative insights.

Tips for Successful Project Topic Selection

To ensure a successful research journey, keep these tips in mind:

- Narrowing Down Your Focus: While it’s essential to choose a topic you’re passionate about, make sure it’s specific enough to be manageable within the scope of your project.

- Staying Informed About Current Economic Events: Stay up-to-date with economic news and events to identify emerging trends and issues that may inspire your research.

- Seeking Guidance from Professors or Advisors: Don’t hesitate to seek advice from your professors or academic advisors. They can provide valuable insights and help you refine your research questions.

Selecting the right economic project topics is a critical step in your academic journey. By identifying your interests, considering the relevance and timeliness of topics, and assessing available resources, you can embark on a rewarding research journey.

Whether you choose to delve into microeconomics, macroeconomics, international economics, or economic policy, remember that your research has the potential to contribute to the broader understanding of economic principles and their real-world applications.

Start your research journey today, and you’ll not only gain valuable knowledge but also make a meaningful contribution to the field of economics.

Related Posts

Top 8 Best Significance Of Economics Everyone Must Know

Types of Economics | Which Is The Most Popular Type of Economics?

Please log in to save materials. Log in

Education Standards

Nebraska business, marketing and management standards.

Learning Domain: Marketing

Standard: Explain the types of economic systems.

Economic Systems - Create a Country Project

This lesson introduces students to the three main types of economic systems, command, market, and mixed. Students work with limited knowledge, not knowing about mixed systems until the very end. This allows students to see the pieces of command systems and market systems that are present in the United States and in their “ideal” economies.

Economic Systems

This lesson introduces students to the three main types of economic systems. Students work with limited knowledge, not knowing about mixed systems until the very end. This allows students to see the pieces of command systems and market systems that are present in the United States and in their “ideal” economies.

Part 1 - Hook

Part 2 - Direct Instruction on Command and Market Economies

Part 3 - Create Country Project

Part 4 - Direct instruction on Mixed Economies, Debrief Island Economies

Part 5 - Present Island Project

Part 6 - Rubric

An ancient artifact has been unearthed, giving you the ability to insert your own country anywhere in the world. Once you place your 20 square miles, the artifact goes dormant. Now is the time to get to work!

Students will work in pairs for this project. They may choose to use the country they started working on during the hook, or create a completely new one.

To have a successful country, you will need to answer the following questions.

- Name of the country and flag.

- Factors of Production:

- Land - Where is your country located? Do some research and list out the land that is available naturally in that area!

- Labor - Who will be allowed to move to your country? Will there be requirements on items such as their education level or ability to work specific jobs?

- Capital - What capital will be needed? Will your businesses create them or will you import them?

- Entrepreneurship - What kind of business will your country have? What goods and services will be created? You will need entrepreneurs to start the businesses, and who will be the labor?

- Wants vs Needs: Will the government provide for any of its citizens wants and needs? Or is it up to each person? Will any basic needs be provided for? (Remember to think about things like education, insurance, safety net for people in need, etc).

- What is the role of government in your country?

- How will prices be set for goods and services? By the businesses? Or will the government set prices?

- What (if anything) will the government regulate?

Put everything together in a creative way, such as an infographic or commercial for your country! Have your own idea? Run it by the teacher!

New Learning/Debrief:

Introduce students to mixed economic systems. Have students compare and contrast the systems.

- Include how they answer the three big questions, and provide students with pros and cons.

- Discuss what pieces about the United States economy is command, market, and how we are a mixed economy.

Have them reflect on the type of system that they chose to create with the following questions.

- Identify some areas that your economic system has that are from a command system and some areas that are from a market system.

- Which system most closely resembles the one you designed (market, command, or mixed)? Define that system and explain how yours compares. Explain referring to how you answered the questions on your economy.

- Identify at least 3 strengths and 3 weaknesses to the economic system that you created. (I suggest looking up strengths and weaknesses of the various types of systems).

- In the past there has been a variety of economic systems, but today the most popular system is the mixed economy. Based on what you know about the United States and your created country, why do you think that is?

Presentation : Have groups present their islands. Audience members will fill out this sheet while listening.

Grading Rubric:

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 17 April 2024

The economic commitment of climate change

- Maximilian Kotz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2564-5043 1 , 2 ,

- Anders Levermann ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4432-4704 1 , 2 &

- Leonie Wenz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8500-1568 1 , 3

Nature volume 628 , pages 551–557 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

63k Accesses

3473 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Environmental economics

- Environmental health

- Interdisciplinary studies

- Projection and prediction

Global projections of macroeconomic climate-change damages typically consider impacts from average annual and national temperatures over long time horizons 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 . Here we use recent empirical findings from more than 1,600 regions worldwide over the past 40 years to project sub-national damages from temperature and precipitation, including daily variability and extremes 7 , 8 . Using an empirical approach that provides a robust lower bound on the persistence of impacts on economic growth, we find that the world economy is committed to an income reduction of 19% within the next 26 years independent of future emission choices (relative to a baseline without climate impacts, likely range of 11–29% accounting for physical climate and empirical uncertainty). These damages already outweigh the mitigation costs required to limit global warming to 2 °C by sixfold over this near-term time frame and thereafter diverge strongly dependent on emission choices. Committed damages arise predominantly through changes in average temperature, but accounting for further climatic components raises estimates by approximately 50% and leads to stronger regional heterogeneity. Committed losses are projected for all regions except those at very high latitudes, at which reductions in temperature variability bring benefits. The largest losses are committed at lower latitudes in regions with lower cumulative historical emissions and lower present-day income.

Similar content being viewed by others

Climate damage projections beyond annual temperature

Paul Waidelich, Fulden Batibeniz, … Sonia I. Seneviratne

Investment incentive reduced by climate damages can be restored by optimal policy

Sven N. Willner, Nicole Glanemann & Anders Levermann

Climate economics support for the UN climate targets

Martin C. Hänsel, Moritz A. Drupp, … Thomas Sterner

Projections of the macroeconomic damage caused by future climate change are crucial to informing public and policy debates about adaptation, mitigation and climate justice. On the one hand, adaptation against climate impacts must be justified and planned on the basis of an understanding of their future magnitude and spatial distribution 9 . This is also of importance in the context of climate justice 10 , as well as to key societal actors, including governments, central banks and private businesses, which increasingly require the inclusion of climate risks in their macroeconomic forecasts to aid adaptive decision-making 11 , 12 . On the other hand, climate mitigation policy such as the Paris Climate Agreement is often evaluated by balancing the costs of its implementation against the benefits of avoiding projected physical damages. This evaluation occurs both formally through cost–benefit analyses 1 , 4 , 5 , 6 , as well as informally through public perception of mitigation and damage costs 13 .

Projections of future damages meet challenges when informing these debates, in particular the human biases relating to uncertainty and remoteness that are raised by long-term perspectives 14 . Here we aim to overcome such challenges by assessing the extent of economic damages from climate change to which the world is already committed by historical emissions and socio-economic inertia (the range of future emission scenarios that are considered socio-economically plausible 15 ). Such a focus on the near term limits the large uncertainties about diverging future emission trajectories, the resulting long-term climate response and the validity of applying historically observed climate–economic relations over long timescales during which socio-technical conditions may change considerably. As such, this focus aims to simplify the communication and maximize the credibility of projected economic damages from future climate change.

In projecting the future economic damages from climate change, we make use of recent advances in climate econometrics that provide evidence for impacts on sub-national economic growth from numerous components of the distribution of daily temperature and precipitation 3 , 7 , 8 . Using fixed-effects panel regression models to control for potential confounders, these studies exploit within-region variation in local temperature and precipitation in a panel of more than 1,600 regions worldwide, comprising climate and income data over the past 40 years, to identify the plausibly causal effects of changes in several climate variables on economic productivity 16 , 17 . Specifically, macroeconomic impacts have been identified from changing daily temperature variability, total annual precipitation, the annual number of wet days and extreme daily rainfall that occur in addition to those already identified from changing average temperature 2 , 3 , 18 . Moreover, regional heterogeneity in these effects based on the prevailing local climatic conditions has been found using interactions terms. The selection of these climate variables follows micro-level evidence for mechanisms related to the impacts of average temperatures on labour and agricultural productivity 2 , of temperature variability on agricultural productivity and health 7 , as well as of precipitation on agricultural productivity, labour outcomes and flood damages 8 (see Extended Data Table 1 for an overview, including more detailed references). References 7 , 8 contain a more detailed motivation for the use of these particular climate variables and provide extensive empirical tests about the robustness and nature of their effects on economic output, which are summarized in Methods . By accounting for these extra climatic variables at the sub-national level, we aim for a more comprehensive description of climate impacts with greater detail across both time and space.

Constraining the persistence of impacts

A key determinant and source of discrepancy in estimates of the magnitude of future climate damages is the extent to which the impact of a climate variable on economic growth rates persists. The two extreme cases in which these impacts persist indefinitely or only instantaneously are commonly referred to as growth or level effects 19 , 20 (see Methods section ‘Empirical model specification: fixed-effects distributed lag models’ for mathematical definitions). Recent work shows that future damages from climate change depend strongly on whether growth or level effects are assumed 20 . Following refs. 2 , 18 , we provide constraints on this persistence by using distributed lag models to test the significance of delayed effects separately for each climate variable. Notably, and in contrast to refs. 2 , 18 , we use climate variables in their first-differenced form following ref. 3 , implying a dependence of the growth rate on a change in climate variables. This choice means that a baseline specification without any lags constitutes a model prior of purely level effects, in which a permanent change in the climate has only an instantaneous effect on the growth rate 3 , 19 , 21 . By including lags, one can then test whether any effects may persist further. This is in contrast to the specification used by refs. 2 , 18 , in which climate variables are used without taking the first difference, implying a dependence of the growth rate on the level of climate variables. In this alternative case, the baseline specification without any lags constitutes a model prior of pure growth effects, in which a change in climate has an infinitely persistent effect on the growth rate. Consequently, including further lags in this alternative case tests whether the initial growth impact is recovered 18 , 19 , 21 . Both of these specifications suffer from the limiting possibility that, if too few lags are included, one might falsely accept the model prior. The limitations of including a very large number of lags, including loss of data and increasing statistical uncertainty with an increasing number of parameters, mean that such a possibility is likely. By choosing a specification in which the model prior is one of level effects, our approach is therefore conservative by design, avoiding assumptions of infinite persistence of climate impacts on growth and instead providing a lower bound on this persistence based on what is observable empirically (see Methods section ‘Empirical model specification: fixed-effects distributed lag models’ for further exposition of this framework). The conservative nature of such a choice is probably the reason that ref. 19 finds much greater consistency between the impacts projected by models that use the first difference of climate variables, as opposed to their levels.

We begin our empirical analysis of the persistence of climate impacts on growth using ten lags of the first-differenced climate variables in fixed-effects distributed lag models. We detect substantial effects on economic growth at time lags of up to approximately 8–10 years for the temperature terms and up to approximately 4 years for the precipitation terms (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Extended Data Table 2 ). Furthermore, evaluation by means of information criteria indicates that the inclusion of all five climate variables and the use of these numbers of lags provide a preferable trade-off between best-fitting the data and including further terms that could cause overfitting, in comparison with model specifications excluding climate variables or including more or fewer lags (Extended Data Fig. 3 , Supplementary Methods Section 1 and Supplementary Table 1 ). We therefore remove statistically insignificant terms at later lags (Supplementary Figs. 1 – 3 and Supplementary Tables 2 – 4 ). Further tests using Monte Carlo simulations demonstrate that the empirical models are robust to autocorrelation in the lagged climate variables (Supplementary Methods Section 2 and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5 ), that information criteria provide an effective indicator for lag selection (Supplementary Methods Section 2 and Supplementary Fig. 6 ), that the results are robust to concerns of imperfect multicollinearity between climate variables and that including several climate variables is actually necessary to isolate their separate effects (Supplementary Methods Section 3 and Supplementary Fig. 7 ). We provide a further robustness check using a restricted distributed lag model to limit oscillations in the lagged parameter estimates that may result from autocorrelation, finding that it provides similar estimates of cumulative marginal effects to the unrestricted model (Supplementary Methods Section 4 and Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9 ). Finally, to explicitly account for any outstanding uncertainty arising from the precise choice of the number of lags, we include empirical models with marginally different numbers of lags in the error-sampling procedure of our projection of future damages. On the basis of the lag-selection procedure (the significance of lagged terms in Extended Data Fig. 1 and Extended Data Table 2 , as well as information criteria in Extended Data Fig. 3 ), we sample from models with eight to ten lags for temperature and four for precipitation (models shown in Supplementary Figs. 1 – 3 and Supplementary Tables 2 – 4 ). In summary, this empirical approach to constrain the persistence of climate impacts on economic growth rates is conservative by design in avoiding assumptions of infinite persistence, but nevertheless provides a lower bound on the extent of impact persistence that is robust to the numerous tests outlined above.

Committed damages until mid-century

We combine these empirical economic response functions (Supplementary Figs. 1 – 3 and Supplementary Tables 2 – 4 ) with an ensemble of 21 climate models (see Supplementary Table 5 ) from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP-6) 22 to project the macroeconomic damages from these components of physical climate change (see Methods for further details). Bias-adjusted climate models that provide a highly accurate reproduction of observed climatological patterns with limited uncertainty (Supplementary Table 6 ) are used to avoid introducing biases in the projections. Following a well-developed literature 2 , 3 , 19 , these projections do not aim to provide a prediction of future economic growth. Instead, they are a projection of the exogenous impact of future climate conditions on the economy relative to the baselines specified by socio-economic projections, based on the plausibly causal relationships inferred by the empirical models and assuming ceteris paribus. Other exogenous factors relevant for the prediction of economic output are purposefully assumed constant.

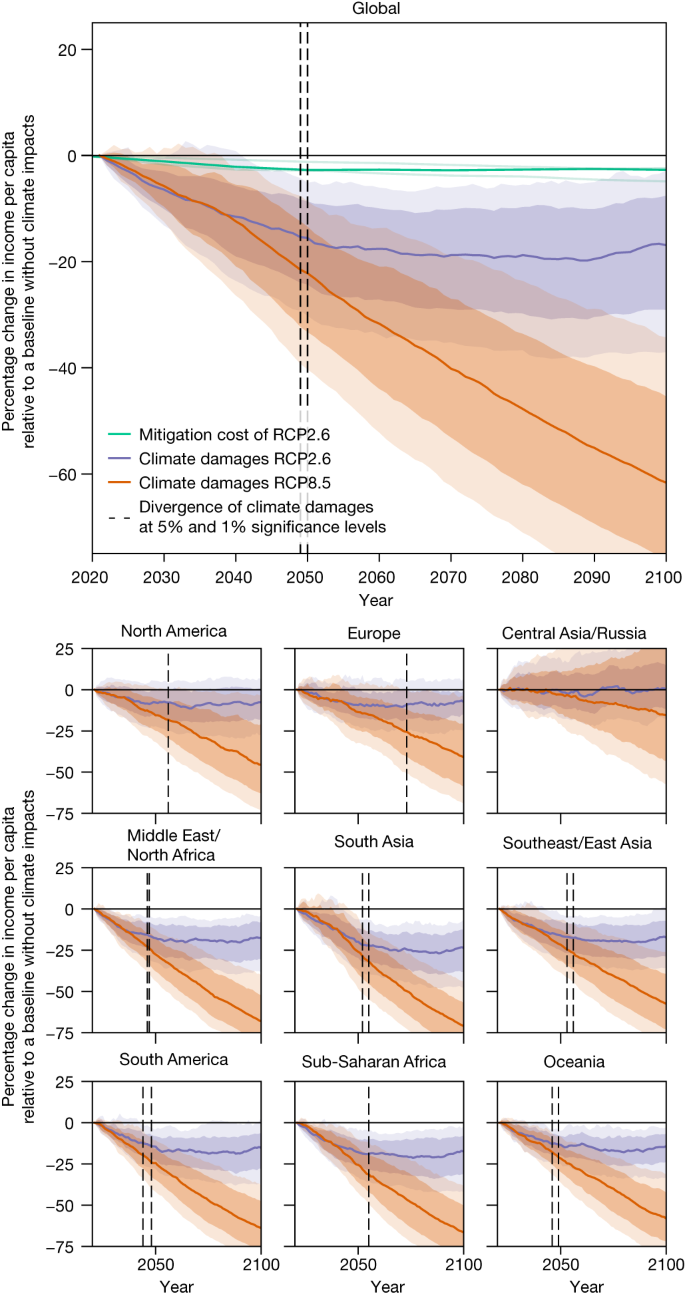

A Monte Carlo procedure that samples from climate model projections, empirical models with different numbers of lags and model parameter estimates (obtained by 1,000 block-bootstrap resamples of each of the regressions in Supplementary Figs. 1 – 3 and Supplementary Tables 2 – 4 ) is used to estimate the combined uncertainty from these sources. Given these uncertainty distributions, we find that projected global damages are statistically indistinguishable across the two most extreme emission scenarios until 2049 (at the 5% significance level; Fig. 1 ). As such, the climate damages occurring before this time constitute those to which the world is already committed owing to the combination of past emissions and the range of future emission scenarios that are considered socio-economically plausible 15 . These committed damages comprise a permanent income reduction of 19% on average globally (population-weighted average) in comparison with a baseline without climate-change impacts (with a likely range of 11–29%, following the likelihood classification adopted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); see caption of Fig. 1 ). Even though levels of income per capita generally still increase relative to those of today, this constitutes a permanent income reduction for most regions, including North America and Europe (each with median income reductions of approximately 11%) and with South Asia and Africa being the most strongly affected (each with median income reductions of approximately 22%; Fig. 1 ). Under a middle-of-the road scenario of future income development (SSP2, in which SSP stands for Shared Socio-economic Pathway), this corresponds to global annual damages in 2049 of 38 trillion in 2005 international dollars (likely range of 19–59 trillion 2005 international dollars). Compared with empirical specifications that assume pure growth or pure level effects, our preferred specification that provides a robust lower bound on the extent of climate impact persistence produces damages between these two extreme assumptions (Extended Data Fig. 3 ).

Estimates of the projected reduction in income per capita from changes in all climate variables based on empirical models of climate impacts on economic output with a robust lower bound on their persistence (Extended Data Fig. 1 ) under a low-emission scenario compatible with the 2 °C warming target and a high-emission scenario (SSP2-RCP2.6 and SSP5-RCP8.5, respectively) are shown in purple and orange, respectively. Shading represents the 34% and 10% confidence intervals reflecting the likely and very likely ranges, respectively (following the likelihood classification adopted by the IPCC), having estimated uncertainty from a Monte Carlo procedure, which samples the uncertainty from the choice of physical climate models, empirical models with different numbers of lags and bootstrapped estimates of the regression parameters shown in Supplementary Figs. 1 – 3 . Vertical dashed lines show the time at which the climate damages of the two emission scenarios diverge at the 5% and 1% significance levels based on the distribution of differences between emission scenarios arising from the uncertainty sampling discussed above. Note that uncertainty in the difference of the two scenarios is smaller than the combined uncertainty of the two respective scenarios because samples of the uncertainty (climate model and empirical model choice, as well as model parameter bootstrap) are consistent across the two emission scenarios, hence the divergence of damages occurs while the uncertainty bounds of the two separate damage scenarios still overlap. Estimates of global mitigation costs from the three IAMs that provide results for the SSP2 baseline and SSP2-RCP2.6 scenario are shown in light green in the top panel, with the median of these estimates shown in bold.

Damages already outweigh mitigation costs

We compare the damages to which the world is committed over the next 25 years to estimates of the mitigation costs required to achieve the Paris Climate Agreement. Taking estimates of mitigation costs from the three integrated assessment models (IAMs) in the IPCC AR6 database 23 that provide results under comparable scenarios (SSP2 baseline and SSP2-RCP2.6, in which RCP stands for Representative Concentration Pathway), we find that the median committed climate damages are larger than the median mitigation costs in 2050 (six trillion in 2005 international dollars) by a factor of approximately six (note that estimates of mitigation costs are only provided every 10 years by the IAMs and so a comparison in 2049 is not possible). This comparison simply aims to compare the magnitude of future damages against mitigation costs, rather than to conduct a formal cost–benefit analysis of transitioning from one emission path to another. Formal cost–benefit analyses typically find that the net benefits of mitigation only emerge after 2050 (ref. 5 ), which may lead some to conclude that physical damages from climate change are simply not large enough to outweigh mitigation costs until the second half of the century. Our simple comparison of their magnitudes makes clear that damages are actually already considerably larger than mitigation costs and the delayed emergence of net mitigation benefits results primarily from the fact that damages across different emission paths are indistinguishable until mid-century (Fig. 1 ).

Although these near-term damages constitute those to which the world is already committed, we note that damage estimates diverge strongly across emission scenarios after 2049, conveying the clear benefits of mitigation from a purely economic point of view that have been emphasized in previous studies 4 , 24 . As well as the uncertainties assessed in Fig. 1 , these conclusions are robust to structural choices, such as the timescale with which changes in the moderating variables of the empirical models are estimated (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11 ), as well as the order in which one accounts for the intertemporal and international components of currency comparison (Supplementary Fig. 12 ; see Methods for further details).

Damages from variability and extremes

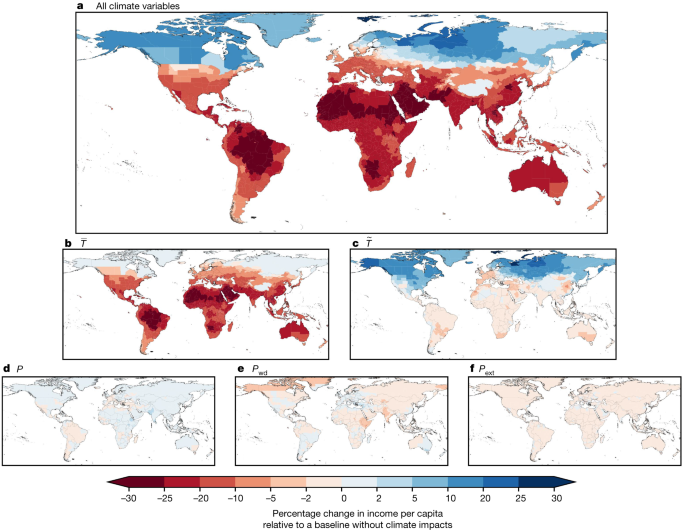

Committed damages primarily arise through changes in average temperature (Fig. 2 ). This reflects the fact that projected changes in average temperature are larger than those in other climate variables when expressed as a function of their historical interannual variability (Extended Data Fig. 4 ). Because the historical variability is that on which the empirical models are estimated, larger projected changes in comparison with this variability probably lead to larger future impacts in a purely statistical sense. From a mechanistic perspective, one may plausibly interpret this result as implying that future changes in average temperature are the most unprecedented from the perspective of the historical fluctuations to which the economy is accustomed and therefore will cause the most damage. This insight may prove useful in terms of guiding adaptation measures to the sources of greatest damage.

Estimates of the median projected reduction in sub-national income per capita across emission scenarios (SSP2-RCP2.6 and SSP2-RCP8.5) as well as climate model, empirical model and model parameter uncertainty in the year in which climate damages diverge at the 5% level (2049, as identified in Fig. 1 ). a , Impacts arising from all climate variables. b – f , Impacts arising separately from changes in annual mean temperature ( b ), daily temperature variability ( c ), total annual precipitation ( d ), the annual number of wet days (>1 mm) ( e ) and extreme daily rainfall ( f ) (see Methods for further definitions). Data on national administrative boundaries are obtained from the GADM database version 3.6 and are freely available for academic use ( https://gadm.org/ ).

Nevertheless, future damages based on empirical models that consider changes in annual average temperature only and exclude the other climate variables constitute income reductions of only 13% in 2049 (Extended Data Fig. 5a , likely range 5–21%). This suggests that accounting for the other components of the distribution of temperature and precipitation raises net damages by nearly 50%. This increase arises through the further damages that these climatic components cause, but also because their inclusion reveals a stronger negative economic response to average temperatures (Extended Data Fig. 5b ). The latter finding is consistent with our Monte Carlo simulations, which suggest that the magnitude of the effect of average temperature on economic growth is underestimated unless accounting for the impacts of other correlated climate variables (Supplementary Fig. 7 ).

In terms of the relative contributions of the different climatic components to overall damages, we find that accounting for daily temperature variability causes the largest increase in overall damages relative to empirical frameworks that only consider changes in annual average temperature (4.9 percentage points, likely range 2.4–8.7 percentage points, equivalent to approximately 10 trillion international dollars). Accounting for precipitation causes smaller increases in overall damages, which are—nevertheless—equivalent to approximately 1.2 trillion international dollars: 0.01 percentage points (−0.37–0.33 percentage points), 0.34 percentage points (0.07–0.90 percentage points) and 0.36 percentage points (0.13–0.65 percentage points) from total annual precipitation, the number of wet days and extreme daily precipitation, respectively. Moreover, climate models seem to underestimate future changes in temperature variability 25 and extreme precipitation 26 , 27 in response to anthropogenic forcing as compared with that observed historically, suggesting that the true impacts from these variables may be larger.

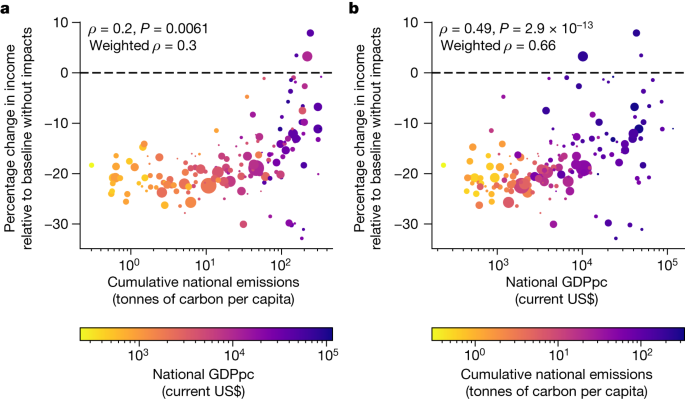

The distribution of committed damages

The spatial distribution of committed damages (Fig. 2a ) reflects a complex interplay between the patterns of future change in several climatic components and those of historical economic vulnerability to changes in those variables. Damages resulting from increasing annual mean temperature (Fig. 2b ) are negative almost everywhere globally, and larger at lower latitudes in regions in which temperatures are already higher and economic vulnerability to temperature increases is greatest (see the response heterogeneity to mean temperature embodied in Extended Data Fig. 1a ). This occurs despite the amplified warming projected at higher latitudes 28 , suggesting that regional heterogeneity in economic vulnerability to temperature changes outweighs heterogeneity in the magnitude of future warming (Supplementary Fig. 13a ). Economic damages owing to daily temperature variability (Fig. 2c ) exhibit a strong latitudinal polarisation, primarily reflecting the physical response of daily variability to greenhouse forcing in which increases in variability across lower latitudes (and Europe) contrast decreases at high latitudes 25 (Supplementary Fig. 13b ). These two temperature terms are the dominant determinants of the pattern of overall damages (Fig. 2a ), which exhibits a strong polarity with damages across most of the globe except at the highest northern latitudes. Future changes in total annual precipitation mainly bring economic benefits except in regions of drying, such as the Mediterranean and central South America (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 13c ), but these benefits are opposed by changes in the number of wet days, which produce damages with a similar pattern of opposite sign (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 13d ). By contrast, changes in extreme daily rainfall produce damages in all regions, reflecting the intensification of daily rainfall extremes over global land areas 29 , 30 (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 13e ).