- 0 Shopping Cart

Hurricane Katrina Case Study

Hurricane Katrina is tied with Hurricane Harvey (2017) as the costliest hurricane on record. Although not the strongest in recorded history, the hurricane caused an estimated $125 billion worth of damage. The category five hurricane is the joint eight strongest ever recorded, with sustained winds of 175 mph (280 km/h).

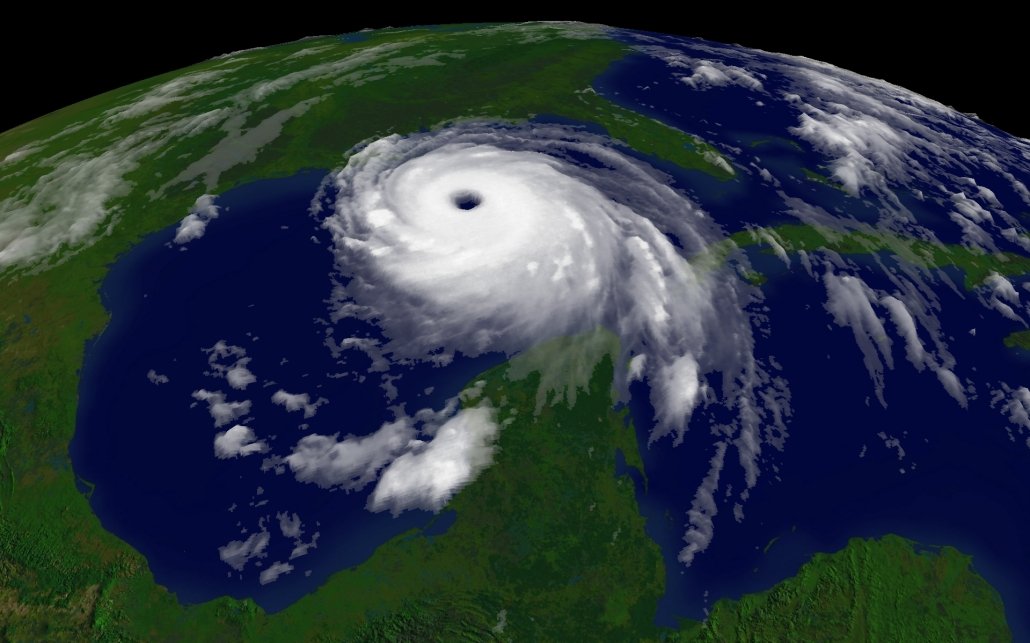

The hurricane began as a very low-pressure system over the Atlantic Ocean. The system strengthened, forming a hurricane that moved west, approaching the Florida coast on the evening of the 25th August 2005.

A satellite image of Hurricane Katrina.

Hurricane Katrina was an extremely destructive and deadly Category 5 hurricane. It made landfall on Florida and Louisiana, particularly the city of New Orleans and surrounding areas, in August 2005, causing catastrophic damage from central Florida to eastern Texas. Fatal flaws in flood engineering protection led to a significant loss of life in New Orleans. The levees, designed to cope with category three storm surges, failed to lead to catastrophic flooding and loss of life.

What were the impacts of Hurricane Katrina?

Hurricane Katrina was a category five tropical storm. The hurricane caused storm surges over six metres in height. The city of New Orleans was one of the worst affected areas. This is because it lies below sea level and is protected by levees. The levees protect the city from the Mississippi River and Lake Ponchartrain. However, these were unable to cope with the storm surge, and water flooded the city.

$105 billion was sought by The Bush Administration for repairs and reconstruction in the region. This funding did not include potential interruption of the oil supply, destruction of the Gulf Coast’s highway infrastructure, and exports of commodities such as grain.

Although the state made an evacuation order, many of the poorest people remained in New Orleans because they either wanted to protect their property or could not afford to leave.

The Superdome stadium was set up as a centre for people who could not escape the storm. There was a shortage of food, and the conditions were unhygienic.

Looting occurred throughout the city, and tensions were high as people felt unsafe. 1,200 people drowned in the floods, and 1 million people were made homeless. Oil facilities were damaged, and as a result, the price of petrol rose in the UK and USA.

80% of the city of New Orleans and large neighbouring parishes became flooded, and the floodwaters remained for weeks. Most of the transportation and communication networks servicing New Orleans were damaged or disabled by the flooding, and tens of thousands of people who had not evacuated the city before landfall became stranded with little access to food, shelter or basic necessities.

The storm surge caused substantial beach erosion , in some cases completely devastating coastal areas.

Katrina also produced massive tree loss along the Gulf Coast, particularly in Louisiana’s Pearl River Basin and among bottomland hardwood forests.

The storm caused oil spills from 44 facilities throughout southeastern Louisiana. This resulted in over 7 million US gallons (26,000 m 3 ) of oil being leaked. Some spills were only a few hundred gallons, and most were contained on-site, though some oil entered the ecosystem and residential areas.

Some New Orleans residents are no longer able to get home insurance to cover them from the impact of hurricanes.

What was the response to Hurricane Katrina?

The US Government was heavily criticised for its handling of the disaster. Despite many people being evacuated, it was a very slow process. The poorest and most vulnerable were left behind.

The government provided $50 billion in aid.

During the early stages of the recovery process, the UK government sent food aid.

The National Guard was mobilised to restore law and order in New Orleans.

Premium Resources

Please support internet geography.

If you've found the resources on this page useful please consider making a secure donation via PayPal to support the development of the site. The site is self-funded and your support is really appreciated.

Related Topics

Use the images below to explore related GeoTopics.

Hurricane Florence

Topic home, hurricane michael, share this:.

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

If you've found the resources on this site useful please consider making a secure donation via PayPal to support the development of the site. The site is self-funded and your support is really appreciated.

Search Internet Geography

Top posts and pages.

Latest Blog Entries

Pin It on Pinterest

- Click to share

- Print Friendly

Teach the Earth the portal for Earth Education

From NAGT's On the Cutting Edge Collection

- Course Topics

- Atmospheric Science

- Biogeoscience

- Environmental Geology

- Environmental Science

- Geochemistry

- Geomorphology

- GIS/Remote Sensing

- Hydrology/Hydrogeology

- Oceanography

- Paleontology

- Planetary Science

- Sedimentary Geology

- Structural Geology

- Incorporating Societal Issues

- Climate Change

- Complex Systems

- Ethics and Environmental Justice

- Geology and Health

- Public Policy

- Sustainability

- Strengthening Your Department

- Career Development

- Strengthening Departments

- Student Recruitment

- Teacher Preparation

- Teaching Topics

- Biocomplexity

- Early Earth

- Earthquakes

- Hydraulic Fracturing

- Plate Tectonics

- Teaching Environments

- Intro Geoscience

- Online Teaching

- Teaching in the Field

- Two-Year Colleges

- Urban Students

- Enhancing your Teaching

- Affective Domain

- Course Design

- Data, Simulations, Models

- Geophotography

- Google Earth

- Metacognition

- Online Games

- Problem Solving

- Quantitative Skills

- Rates and Time

- Service Learning

- Spatial Thinking

- Teaching Methods

- Teaching with Video

- Undergrad Research

- Visualization

- Teaching Materials

- Two Year Colleges

- Departments

- Workshops and Webinars

Geology and Human Health Topical Resources

- ⋮⋮⋮ ×

The Health Effects of Hurricane Katrina

Hurricane Katrina

Hurricanes are natural disasters that have unfortunately been on the rise as the years have gone on. With any natural disaster, comes concerns for human health. Hurricane Katrina brought with it flood waters, the loss of power, little livable space left, and a breeding ground for mosquitoes. This in turn caused molds to grow, endotoxin levels to rise, little clean drinking water, spoiled food, West Nile virus concerns, and many other causes for a person to be sick. New Orleans, Louisiana was devastated by Hurricane Katrina. Close to 90 percent of the city was flooded, some parts of the city under 20 feet of water. Many structures were completely destroyed and those that weren't destroyed by the hurricane, most likely had to be destroyed because of how long the flood waters were there. The pumps used to rid the city of the water, were not working and because they couldn't be replaced, had to be repaired. This led to the integrity of the buildings to be compromised, leaving people homeless and worries to arise about the places refugees were going to stay when the water was all pumped out of the city.

Katrina's Path

Katrina began about 200 miles southeast of Nassau in the Bahamas. It then moved northwest, becoming Tropical Storm Katrina. It continued through the northwestern Bahamas (August 24-25) and then went westward towards southern Florida. Tropical Storm Katrina became Hurricane Katrina just before it made landfall near the Miami-Dade/Broward county line (August 25). It then moved southwest across southern Florida and into the eastern Gulf of Mexico (August 26). The center made landfall near Buras, Louisiana (August 29) and continued north. It was still a hurricane near Laurel, Mississippi, but became a tropical depression over the Tennessee Valley (August 30). It continued up to the Great Lakes, weakening until it became a frontal zone (August 31).

Health Effects of Hurricane Katrina

The main health effects of Hurricane Katrina had to deal with the amount of water left behind in New Orleans. Outbreaks of West Nile, mold, and endotoxin levels rising were the biggest concerns. With the flooding came all new types of bacteria from the open water, leaving New Orleans with little to defend itself. The medical centers were either destroyed or in utter disarray and power was lost for quite awhile. The concern that people were going to get sick because of contaminated food or water also weighed heavily on people's minds. All of the health concerns for New Orleans came from the amount of flood water because there was so much of it, that it was an optimal breeding ground for mosquitoes and the water covered everything making nothing truly safe.

Here is a link to the NOAA (National Oceanic And Atmospheric Administration) site on Hurricane Katrina and a few impacts Katrina had in the south United States. Hurricane Katrina .

The clean up for Hurricane Katrina is still on going. A lot of water flooded the city and some areas that were flooded near New Orleans are still under water. Those areas may just become lakes because the water may never drain out. New Orleans had to fix their water pumps in order to drain their city. This took a few days because they couldn't replace them since the pumps they did have, weren't manufactured anymore. The extra time it took to repair the pumps meant that the city stayed in the dirty water that much longer. This meant that most homes that were flooded had to be completely destroyed. The foundations were weakened and more and more mold was growing. The city was going to be uninhabitatable longer and longer. The levees also had to be repaired to keep the water out of the city. When the water was finally pumped out, the homes had to be taken care of. The people of the city were put in temporary trailers while their homes were destroyed and then reconstructed. Every home that was flooded, had to be destroyed because it sat too long, too much mold and putrid water sat within them. Once the homes were cleared and power was restored, the concerns for human health went down considerably. Clean water and food were brought in while the plants that filtered the water were being repaired and power was restored.

Effects Hurricane Katrina Had on the Rest of the U.S.

Katrina hit New Orleans the hardest, mainly because it is below sea level and easily flooded, but it also did damage in other states. It caused flooding in Southern Florida and damage and extensive power outages in Miami. From the Gulf coast to the Ohio Valley, flood watches and warnings were issued. Parts of Biloxi and Gulfport, Mississippi were under water. Some rain bands from Katrina also produced tornadoes creating more damage. Some areas effected by the tornadoes were in Georgia. Most of the death toll though, was in Mississippi and Louisiana, but a few deaths were also reported in Florida. The entire U.S. was also affected when the oil rigs in the Gulf were found to have suffered major damages, making gas prices go up.

In order to prevent more disasterous floods in New Orleans, better levees have been built and a better disaster plan has been made. Unfortunately, because New Orleans is below sea level completely preventing a disaster like this is not possible. New Orleans will continue to sink and flooding will always be a problem. Better, faster clean up is the only way that the city can prevent a disaster as great as Hurricane Katrina. Routine maintenance of the pumps and levees can help keep the water at bay, but one day it will return. Fast action, awareness, and knowledge of a disaster plan are the only things that people can do to protect themselves. Those and flood insurance, will help to make sure people stay safe. Also, when a city is evacuated for a hurricane make sure to secure your home and then evacuate yourself.

Recommended Readings

"Effect of Hurricane Katrina on New Orleans." Angelfire . N.p., 2005. Web. Sept. 2012. https://www.angelfire.com/la3/judyb/katrina.html

This website covers what was done in New Orleans before and after Hurricane Katrina. It also talks about the different problems that arose and how they were taken care of. This is a reliable, objective source that discusses the events of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. It was very useful in discussing the specific effects Hurricane Katrina had on New Orleans and how the hurricane was handled there.

Used sites:

National oceanic and atmospheric administration (last accessed 12/10/12):.

This website gives an account of what happen before, during, and after Hurricane Katrina.

- http://www.vos.noaa.gov/MWL/apr_06/katrina.shtml

This website tells of the path Hurricane Katrina took and the effects Katrina had on certain areas.

- http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/outreach/history/#katrina

This website is an overview of the weather side of Hurricane Katrina and how that effected the areas Katrina passed over.

- http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/special-reports/katrina.html

National Center of Biotechnology Information (last accessed 12/10/12):

This website about the procedure people took to check their homes for mold and check the endotoxin levels to make sure they're home was safe.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17185280

Environmental Protection Agency (last accessed 12/10/12):

The website tells about the health problems facing New Orleans and how to deal with them.

- http://www.epa.gov/katrina/healthissues.html#d

Effects of Hurricane Katrina on New Orleans (last accessed 12/10/12):

This website tells about the predictions given for Katrina and then what actually happened and how everything was taken care of.

- https://www.angelfire.com/la3/judyb/katrina.html

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (last accessed 12/10/12):

This website gives an overview of what happened and what was done to deal with the effects.

- http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/hurricanes/archives/2005/h2005_katrina.html

See more Health Case Studies »

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Hurricane Katrina

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 28, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

Early in the morning on August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast of the United States. When the storm made landfall, it had a Category 3 rating on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale–it brought sustained winds of 100–140 miles per hour–and stretched some 400 miles across.

While the storm itself did a great deal of damage, its aftermath was catastrophic. Levee breaches led to massive flooding, and many people charged that the federal government was slow to meet the needs of the people affected by the storm. Hundreds of thousands of people in Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama were displaced from their homes, and experts estimate that Katrina caused more than $100 billion in damage.

Hurricane Katrina: Before the Storm

The tropical depression that became Hurricane Katrina formed over the Bahamas on August 23, 2005, and meteorologists were soon able to warn people in the Gulf Coast states that a major storm was on its way. By August 28, evacuations were underway across the region. That day, the National Weather Service predicted that after the storm hit, “most of the [Gulf Coast] area will be uninhabitable for weeks…perhaps longer.”

Did you know? During the past century, hurricanes have flooded New Orleans six times: in 1915, 1940, 1947, 1965, 1969 and 2005.

New Orleans was at particular risk. Though about half the city actually lies above sea level, its average elevation is about six feet below sea level–and it is completely surrounded by water. Over the course of the 20th century, the Army Corps of Engineers had built a system of levees and seawalls to keep the city from flooding. The levees along the Mississippi River were strong and sturdy, but the ones built to hold back Lake Pontchartrain, Lake Borgne and the waterlogged swamps and marshes to the city’s east and west were much less reliable.

Levee Failures

Before the storm, officials worried that surge could overtop some levees and cause short-term flooding, but no one predicted levees might collapse below their designed height. Neighborhoods that sat below sea level, many of which housed the city’s poorest and most vulnerable people, were at great risk of flooding.

The day before Katrina hit, New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin issued the city’s first-ever mandatory evacuation order. He also declared that the Superdome, a stadium located on relatively high ground near downtown, would serve as a “shelter of last resort” for people who could not leave the city. (For example, some 112,000 of New Orleans’ nearly 500,000 people did not have access to a car.) By nightfall, almost 80 percent of the city’s population had evacuated. Some 10,000 had sought shelter in the Superdome, while tens of thousands of others chose to wait out the storm at home.

By the time Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans early in the morning on Monday, August 29, it had already been raining heavily for hours. When the storm surge (as high as 9 meters in some places) arrived, it overwhelmed many of the city’s unstable levees and drainage canals. Water seeped through the soil underneath some levees and swept others away altogether.

By 9 a.m., low-lying places like St. Bernard Parish and the Ninth Ward were under so much water that people had to scramble to attics and rooftops for safety. Eventually, nearly 80 percent of the city was under some quantity of water.

Hurricane Katrina: The Aftermath

Many people acted heroically in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. The Coast Guard rescued some 34,000 people in New Orleans alone, and many ordinary citizens commandeered boats, offered food and shelter, and did whatever else they could to help their neighbors. Yet the government–particularly the federal government–seemed unprepared for the disaster. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) took days to establish operations in New Orleans, and even then did not seem to have a sound plan of action.

Officials, even including President George W. Bush , seemed unaware of just how bad things were in New Orleans and elsewhere: how many people were stranded or missing; how many homes and businesses had been damaged; how much food, water and aid was needed. Katrina had left in her wake what one reporter called a “total disaster zone” where people were “getting absolutely desperate.”

Failures in Government Response

For one thing, many had nowhere to go. At the Superdome in New Orleans, where supplies had been limited to begin with, officials accepted 15,000 more refugees from the storm on Monday before locking the doors. City leaders had no real plan for anyone else. Tens of thousands of people desperate for food, water and shelter broke into the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center complex, but they found nothing there but chaos.

Meanwhile, it was nearly impossible to leave New Orleans: Poor people especially, without cars or anyplace else to go, were stuck. For instance, some people tried to walk over the Crescent City Connection bridge to the nearby suburb of Gretna, but police officers with shotguns forced them to turn back.

Katrina pummeled huge parts of Louisiana , Mississippi and Alabama , but the desperation was most concentrated in New Orleans. Before the storm, the city’s population was mostly black (about 67 percent); moreover, nearly 30 percent of its people lived in poverty. Katrina exacerbated these conditions and left many of New Orleans’s poorest citizens even more vulnerable than they had been before the storm.

In all, Hurricane Katrina killed nearly 2,000 people and affected some 90,000 square miles of the United States. Hundreds of thousands of evacuees scattered far and wide. According to The Data Center , an independent research organization in New Orleans, the storm ultimately displaced more than 1 million people in the Gulf Coast region.

Political Fallout From Hurricane Katrina

In the wake of the storm's devastating effects, local, state and federal governments were criticized for their slow, inadequate response, as well as for the levee failures around New Orleans. And officials from different branches of government were quick to direct the blame at each other.

"We wanted soldiers, helicopters, food and water," Denise Bottcher, press secretary for then-Gov. Kathleen Babineaux Blanco of Louisiana told the New York Times . "They wanted to negotiate an organizational chart."

New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin argued that there was no clear designation of who was in charge, telling reporters, “The state and federal government are doing a two-step dance."

President George W. Bush had originally praised his director of FEMA, Michael D. Brown, but as criticism mounted, Brown was forced to resign, as was the New Orleans Police Department Superintendent. Louisiana Governor Blanco declined to seek re-election in 2007 and Mayor Nagin left office in 2010. In 2014 Nagin was convicted of bribery, fraud and money laundering while in office.

The U.S. Congress launched an investigation into government response to the storm and issued a highly critical report in February 2006 entitled, " A Failure of Initiative ."

Changes Since Katrina

The failures in response during Katrina spurred a series of reforms initiated by Congress. Chief among them was a requirement that all levels of government train to execute coordinated plans of disaster response. In the decade following Katrina, FEMA paid out billions in grants to ensure better preparedness.

Meanwhile, the Army Corps of Engineers built a $14 billion network of levees and floodwalls around New Orleans. The agency said the work ensured the city's safety from flooding for the time. But an April 2019 report from the Army Corps stated that, in the face of rising sea levels and the loss of protective barrier islands, the system will need updating and improvements by as early as 2023.

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Katrina Meteorology and Forecasting

- Katrina Impacts

Case Study – Hurricane Katrina

At least 1,500 people were killed and around $300 billion worth of damage was caused when Hurricane Katrina hit the south-eastern part of the USA. Arriving in late August 2005 with winds of up to 127 mph, the storm caused widespread flooding.

Physical impacts of Hurricane Katrina

Flooding Hurricanes can cause the sea level around them to rise, this effect is called a storm surge. This is often the most dangerous characteristic of a hurricane, and causes the most hurricane-related deaths. It is especially dangerous in low-lying areas close to the coast.

There is more about hurricanes in the weather section of the Met Office website https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/research/weather/tropical-cyclones/facts

Hurricane Katrina tracked over the Gulf of Mexico and hit New Orleans, a coastal city with huge areas below sea-level which were protected by defence walls, called levees. The hurricane’s storm surge, combined with huge waves generated by the wind, pushed up water levels around the city.

The levees were overwhelmed by the extra water, with many collapsing completely. This allowed water to flood into New Orleans, and up to 80% of the city was flooded to depths of up to six metres.

Hurricane Katrina also produced a lot of rainfall, which also contributed to the flooding.

In pictures

Strong winds The strongest winds during 25-30 August were over the coastal areas of Louisiana and Florida. A map of the maximum wind speeds which were recorded during the Hurricane Katrina episode is shown. Although the winds did not directly kill many people, it did produce a storm surge over the ocean which led to flooding in coastal areas and was responsible for many deaths.

Satellite Image

Illustration

Tornadoes Hurricanes can create tornadoes. Thirty-three tornadoes were produced by Hurricane Katrina over a five-day period, although only one person died due to a tornado which affected Georgia.

Impact on humans

- 1,500 deaths in the states of Louisiana, Mississippi and Florida.

- Costs of about $300 billion.

- Thousands of homes and businesses destroyed.

- Criminal gangs roamed the streets, looting homes and businesses and committing other crimes.

- Thousands of jobs lost and millions of dollars in lost tax incomes.

- Agricultural production was damaged by tornadoes and flooding. Cotton and sugar-cane crops were flattened.

- Three million people were left without electricity for over a week.

- Tourism centres were badly affected.

- A significant part of the USA oil refining capacity was disrupted after the storm due to flooded refineries and broken pipelines, and several oil rigs in the Gulf were damaged.

- Major highways were disrupted and some major road bridges were destroyed.

- Many people have moved to live in other parts of the USA and many may never return to their original homes.

The broken levees were repaired by engineers and the flood water in the streets of New Orleans took several months to drain away. The broken levees and consequent flooding were largely responsible for most of the deaths in New Orleans. One of the first challenges in the aftermath of the flooding was to repair the broken levees. Vast quantities of materials, such as sandbags, were airlifted in by the army and air force and the levees were eventually repaired and strengthened.

Although the USA is one of the wealthiest developed countries in the world, it highlighted that when a disaster is large enough, even very developed countries struggle to cope.

Weather Map

Web page reproduced with the kind permission of the Met Office

Start exploring

- Search Resources

- All Levels Primary Secondary Geography Secondary Maths Secondary Science

- Choose a topic All Topics Air Masses Anticyclones Carbon Cycle Climate Climate Change Climate Zones Clouds Contour Coriolis Depressions El Nino Extreme Weather Flooding Front Global Atmospheric Circulation Hydrological Cycle Microclimates Past Climate Snow Synoptic Charts Tropical Cyclones Urban Heat Island Water Cycle Weather Weather Forecast Weather Map Weather System

- All Climate Change Adaptation Afforestation Agriculture air quality aircraft Albedo Anthropocene anthropogenic Arctic/ Antarctic Carbon cycle Carbon dioxide removal/ sequestration Carbon footprint Carbon sinks Causes Climate Climate Crisis/ Emergency Climate justice Climate literacy climate stripes/ visualisation Climate zone shift clouds CO2/ carbon dioxide emissions COP Cryosphere Deforestation Desertification Ecosystems Electric vehicles Energy Equity Evidence Extreme weather Feedback loops Fire weather Flood defences Flooding/ flood risk Fossil fuels Fuel security Global energy budget/ balance Green climate fund Greenhouse effect Greenhouse gas concentrations Heatwaves/ extreme heat Hydroelectric power Ice sheets Impacts IPCC Keeling curve Mitigation Modelling Natural variability Nature based solutions Negotiations Net zero Nuclear power Observations Ocean acidification Ocean warming Proxy records Regional climate change Renewable/ non fossil fuel energy Scenarios Schools Strike for Climate Society Solar energy Solutions Storms Temperature/ global warming Tipping points Transport Tropical cyclones Uneven impacts UNFCCC/ governance Urban green infrastructure Urban heat Urbanisation Water cycle Water security Water vapour (H2O) concentrations Weather Wild fires Wind power

- Choose an age range All ages Primary 0 to 7 7 to 11 Secondary 11 to 14 14 to 16 16 to 18

Latest from blog

A new climate for design education, book review: a climate in chaos, new maths lessons with climate contexts, climate change and the natural history gcse, related resources ….

IPCC Updates for Geography Teachers

In Depth – The Global Atmospheric Circulation

Thunderstorms

Beast from the East

Subscribe to metlink updates, weather and climate resources and events for teachers.

© 2024 Royal Meteorological Society RMetS is a registered charity No. 208222

About MetLink Cookies Policy Privacy Policy

- We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experienceBy clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies. More info

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies. More info

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The Impact of Hurricane Katrina on the Mental and Physical Health of Low-Income Parents in New Orleans

The purpose of this study was to document changes in mental and physical health among 392 low-income parents exposed to Hurricane Katrina and to explore how hurricane-related stressors and loss relate to post-Katrina well being. The prevalence of probable serious mental illness doubled, and nearly half of the respondents exhibited probable PTSD. Higher levels of hurricane-related loss and stressors were generally associated with worse health outcomes, controlling for baseline socio-demographic and health measures. Higher baseline resources predicted fewer hurricane-associated stressors, but the consequences of stressors and loss were similar regardless of baseline resources. Adverse health consequences of Hurricane Katrina persisted for a year or more, and were most severe for those experiencing the most stressors and loss. Long-term health and mental health services are needed for low-income disaster survivors, especially those who experience disaster-related stressors and loss.

Hurricane Katrina was one of the worst natural disasters in U.S. history ( U.S. Department of Commerce, 2006 ). Beyond the physical devastation, the hurricane led to elevated health and mental health difficulties among survivors ( Galea et al., 2007 ; Kessler, Galea, Jones, & Parker, 2006 ; Mills, Edmondson, & Park, 2007 ; Wang et al., 2007 ; Weisler, Barbee, & Townsend, 2006 ). Low-income, African American, single mothers were at particularly high risk for suffering these adverse effects ( Adeola, 2009 ; Jones-DeWeever, 2008 ). Even among the most vulnerable groups, however, there is often considerable variation in survivors’ resources, exposure, and responses ( Dyson, 2006 ). The present study investigated how a sample of primarily single, low-income, African-American women adjusted in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Pre-hurricane data permitted an assessment of change in physical and mental health over time and of the role of material and social resources in protecting participants from both hurricane exposure and adverse outcomes following the event.

Each year, excluding droughts and war, nearly 500 incidents across the globe meet the Red Cross definition of a disaster ( Norris, Baker, Murphy, & Kaniasty, 2005 ). A substantial literature has examined the mental and physical health effects of exposure to disasters ( Galea, Nandi, & Vlahov, 2005 ; Rubonis & Bickman, 1991 ). Much of this research focuses on the short-term implications and indicates that disaster survivors evidence a wide range of reactions, including symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as well as other, often co-morbid, conditions such as depression, anxiety, somatization, substance abuse, and physical illness ( Kessler et al., 2006 ; Pfefferbaum & Doughty, 2001 ; Solomon & Green, 1992 ). Specific transient symptoms may include distressing worries, difficulties sleeping and concentrating, and disturbing memories, many of which dissipate over time with solid emotional support ( Norris et al., 2005 ).

Findings on the long-term health and mental health consequences of disasters are somewhat mixed. Whereas some studies have noted enduring effects ( Green et al., 1990 ; Lima, Pai, Santacruz, Lozano, & Luna, 1987 ; Stein et al., 2004 ; Thienkrua et al., 2006 ), the majority find that problems are relatively short-lived, with survivors recovering from the initial shock and trauma within a matter of weeks or months of the event (e.g., Cook & Bickman, 1990 ; Salzer & Bickman, 1999 ; Sundin & Horowitz, 2003 ). Indeed, a meta-analysis of 52 disaster studies indicated that effects attenuate as the number of weeks from the event elapse ( Rubonis & Bickman, 1991 ). Moreover, as many as half of survivors show resilience in the face of loss and trauma, displaying little or no grief beyond the first few months ( Bonanno, 2008 ). Several personality factors appear to be associated with such resilience, including a tendency toward self-enhancement and positive emotions ( Bonanno, Rennicke, & Dekel, 2005 ). Likewise, certain demographic and contextual factors, including gender, education, social support, health, and less stress exposure, are associated with resilient functioning ( Bonanno, Galea, Bucciarelli, & Vlahov, 2007 ). Nonetheless, the emotional and behavioral effects of Hurricane Katrina—which produced widespread community disruption, exposure to an array of known risk factors, and a protracted recovery—were more substantial than those resulting from most previous natural disasters ( Galea et al., 2008 ; Rateau, 2009 ; Sastry & VanLandingham, 2009 ).

Hurricane Katrina

Hurricane Katrina devastated the Gulf Coast region of the United States, contributing to the loss of nearly 2,000 lives and displacing approximately 1.5 million residents. Hurricane Rita occurred just one month later, also affecting some of the participants in this study. Hurricane Katrina was particularly stressful to the low-income and African American residents of New Orleans, many of whom were left homeless and isolated from their social and community networks ( Adeola, 2009 ; Elliot & Pais, 2006 ; Galea, Tracy, Norris, & Coffey, 2008 ; Sharkey, 2007 ). In the city of New Orleans, which was most heavily affected by the levee breaks, it is estimated that 60% percent of the housing stock was destroyed ( U.S. Department of Commerce, 2006 ). The hurricane also seriously damaged or destroyed educational and health facilities in the city, leading to numerous school closures, destruction of medical records, and reductions in the number of hospital beds and health clinics. Large numbers of evacuees have still not returned to New Orleans ( Fussell, Sastry, & VanLandingham, in press ).

Growing evidence suggests that the hurricane had both immediate and lasting adverse health and mental health consequences. A rapid-needs assessment of returning New Orleans residents conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in October 2005 revealed that more than 50 percent of respondents showed signs of a “possible” need for mental health treatment ( Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006 ; Weisler et al., 2006 ). A study of families living in FEMA-subsidized hotels or trailers conducted in February of 2006 reported high rates of disability among caregivers of children, due to depression, anxiety and other psychiatric problems ( Abramson & Garfield, 2006 ). The survey also yielded high rates of reports of chronic health problems (34 percent) and numerous new mental health problems (nearly 50 percent) among children in these families. Another cross-sectional survey of 222 survivors found that over half (52%) continued to experience poor mental and physical health 15 months after Katrina ( Kim, Plumb, Gredig, Rankin, & Taylor, 2008 ). Other researchers have noted an even longer-term persistence of these symptoms ( Galea et al., 2008 ; Ginzburg, 2008 ; Kessler et al., 2008 ; Schoenbaum, 2009 ; Wang et al., 2008 ), with young adults, women, parents of small children, and those with low income suffering the highest levels of PTSD and mental health disorders ( Bolin & Boltin, 1986 ; Galea et al., 2007 ; Kessler et al., 2008 ; Jones-DeWeever, 2008 ).

A major difficulty in assessing such effects, however, is the lack of information on the pre-disaster functioning. Few studies have access to true “baseline” information collected prior to the disaster. Among those studies of events that do have such data, few have been on the catastrophic scale of Hurricane Katrina. An extensive review by Norris and colleagues (2002) found that only 7 of the 160 studies reviewed had pre-disaster data on the individuals examined. Moreover, the samples used in these studies were generally small, with a median sample size of 149 across the 160 studies. The vast majority of disaster studies relied on post-disaster or retrospective data. Although it provides some measure of pre-disaster functioning, retrospective information is likely to be measured with error, leading to biased estimates of effects on post-disaster outcomes. For example, responses to retrospective questions about pre-disaster social support or living circumstances could be colored by post-disaster experiences. A closely related issue is that measures of the actual amount of stressors and loss during the course of a disaster may also be affected by the individual’s state of mind or mental health. For example, reports of actual stressors experienced during a disaster (e.g. fear that one’s life was in danger during the disaster) may be heightened by pre-existing anxiety or depression. If so, it would not be surprising to find that anxiety or depression measured after the disaster is associated with reports of stressful experiences. However, this association would not provide information on whether the stressors heightened mental health problems.

One study examined how 1,043 survivors’ mental health changed from before to between five and eight months after the hurricane ( Kessler et al., 2006 ). Survivors’ reports of health problems were compared to those of 826 people who lived in hurricane-affected areas at the time of this survey and previously were participants in the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCS-R), conducted between 2001 and 2003. This study found significantly higher rates of serious and mild-moderate rates of mental illness (based on the K6 screening scale; Kessler et al., 2002 ) among the post-Katrina sample, but found less suicidality among those in the post-Katrina sample. The much higher (doubled) rate of mental illness is striking. Unfortunately, because this study does not track individuals from before to after the storm, it is not possible to assess which pre-hurricane factors were protective against increases in mental illness and which were not.

It is also difficult, in the absence of baseline data, to account for variability in adaptive functioning among survivors. Even among the most vulnerable populations, there is often considerable heterogeneity in survivors’ responses to traumatic events. Baseline data permit an exploration of the economic, social, and health and mental health resources, alone and in combination, that might heighten vulnerability or strengthen resilience. Previous explanatory models of disaster responses have focused on the interrelationships between the severity of exposure and the resources available to the individual. Most of these models have posited that resources function to moderate or “buffer” the effects of hurricane experiences, influencing individuals’ perceptions of and their responses to the disaster. Survivors with initially low levels of health, social or economic resources are thought to be more vulnerable to the negative consequences of the hurricane, and to experience relatively steeper declines in emotional and physical health outcomes. Social support has been shown to buffer against stress, and the lack of social support has been identified as a risk factor of PTSD ( Galea et al., 2008 ; Kaniasty & Norris, 2008 ; Ozer & Weiss, 2004 ; Weems et al., 2007 ).

Researchers have also looked at the loss of social support and other resources in explaining variability in stress responses. Within this context, the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory posits that it is the threatened or actual loss of health, social, or economic resources that leads to psychological distress ( Hobfoll, 1989 ). According to COR, individuals strive to obtain and retain personal and social resources, and experience stress when circumstances threaten or diminish these resources. Resources tend to beget more resources, whereas a loss of resources tends to result in further loss. In particular, those individuals who have fewer resources prior to a stressor are less equipped to invest resources in recovery, such that efforts to recover from losses lead to progressive depletion of resources. Previous research on natural disasters indicates that the loss of social, health, or economic resources is associated with declines in psychosocial functioning ( Kaiser, Sattler, Bellack, & Dersin, 1996 ; Sattler et al., 2002 ; Smith & Freedy, 2000 ; Sümer, Karancı, Berument, & ve Güneş, 2005 ).

Resources can also affect the degree of hurricane-related stress that is experienced. Differential access to resources prior to the storm, such as reliable information, transportation, and more geographically extended social networks, can affect variations in exposure to the disaster ( Adeola, 2009 ; Lieberman, 2006 ; Stephens, Hamedani, Markus, Bergsieker, & Eloul, 2009 ). Hobfoll and Parris Stevens (1990) have posited that social support may “directly prevent or limit resource loss and thereby insulate people from stressful circumstances” (p. 458). Likewise, Kaniasty and Norris (2009) noted that pre-disaster resources can influence the degree of disaster exposure. This was clearly the case with Hurricane Katrina, where low-income communities of color were more vulnerable to its impact (Adeloa, 2008). Most high- and medium-income families evacuated in advance of the storm and secured places to stay in hotels, or with family and friends in other cities. Low-income families, in contrast, were disproportionately stranded in the city or in shelters after the storm, increasing the chance that they experienced deprivation, stress and fear ( Elliot & Pais, 2006 ; Lavelle & Feagin, 2006 ; Spence, Lachlan, & Griffin, 2007 ). Brodie et al. (2006) found that, among survivors who did not evacuate New Orleans, more than a third lacked a means of transportation. Others have noted that those with fewer economic resources are more likely to live in housing that is unable to withstand natural disasters ( Ruscher, 2006 ; Weems et al., 2007 ). Moreover, those who are poor tend to receive and heed fewer evacuation warnings, heightening their risk for exposure ( Dyson, 2006 ; Lieberman, 2006 ; Stephens et al., 2009 ).

Current Study

The current study examines the consequences of Hurricane Katrina on the physical and mental health of a particularly vulnerable group of survivors—low-income, predominantly African American, single mothers. Using a unique panel dataset that follows individuals from more than a year before the hurricane to approximately 18 months afterwards, we document changes in the physical and mental health of study participants and examine how the degree of exposure to hurricane-related stressors experienced during the hurricane is related to their post-Katrina well-being. The existence of pre-hurricane data permits us to examine whether pre-hurricane resources—including economic, social, and health resources—had protective effects on post-hurricane health outcomes. In particular, we examine the extent to which exposure to hurricane-related stressors, level of property damage, and water depth affected mental and physical health outcomes after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita after controlling for demographic and pre-hurricane mental and physical health. Given the extent to which mental health can affect perceptions of difficulties, we expected that objective measures of damage—such as flood depths obtained via geo-coding—would be less strongly related to pre-hurricane mental health than more subjective measures of perceived stressors and loss.

We also examine the protective role of resources that were available prior to Hurricane Katrina. Although previous studies have examined retrospective accounts of pre-disaster resources (or the buffering role of post-disaster resources), pre-Katrina data permit an examination of whether the social and material resources that the predominantly low-income, African American mothers had at their disposal prior to the natural disaster affected the severity of their exposure to the disaster.

Data Collection and Sample Characteristics

Participants were initially part of a study of low-income parents who had enrolled in two community colleges in the city of New Orleans in 2004-2005. The purpose of the study was to examine whether performance-based scholarships affect academic achievement and therefore also health and well-being ( Brock & Richburg-Hayes, 2006 ). Baseline demographic and health information was collected for all of the 1,019 participants in the study. By the time Hurricane Katrina struck, 492 participants had been enrolled in the program long enough to complete a 12-month follow-up survey, which included information on participants’ economic status, social support, and physical and mental health. After Hurricane Katrina, between May 2006 and March 2007, 402 (81.7%) of those participants who had completed the 12-month survey were successfully located by a survey research firm and surveyed over the telephone. The post-disaster surveys, which were administered over the phone by trained interviewers, included the same questions as the pre-disaster 12-month follow-up survey, as well as a measure of PTSD and module that collected detailed information about hurricane experiences. Below, we refer to information from the baseline and 12-month surveys as “pre-Katrina” data, and information from the more recent survey as “post-Katrina” data. The analyses in this paper draw on a sample of 392 respondents who reported living in an area affected by Hurricane Katrina at the time the hurricane struck.

All the participants experienced the hurricane and most (98.0%) evacuated, however, their trajectories varied: 85.4% departed before the storm struck, while 4.9% left during the storm, and 9.6% left in the week of, or after, Katrina. The participants had moved an average of 2.5 times ( SD = .4). At the time of the post-Katrina follow-up survey, 47.7% were living in the New Orleans MSA, 12.5% were living elsewhere in Louisiana, 24.9% were in Texas, 4.7 were in Georgia, and the remaining 10.2% were in other states.

Table 1 presents demographic information for the participants. The average age at the time of Hurricane Katrina was 26.6 years ( SD = 4.5). The majority was female (95.9%). The majority was African-American (84.2%), reflecting the demographics of the City of New Orleans in which 67.7% of the population was African-American in 2004 (see Jones-DeWeever, 2008 ). Most were neither married nor co-habiting with a romantic partner (64.0%). More than two-thirds (64.3%) received public assistance in the month prior to the pre-Katrina survey. Nearly three quarters (72.9%) owned a working car prior to the Hurricane.

Baseline Characteristics of the Sample

Economic status

We used three measures of pre-Katrina economic status: the logarithm of total household income in the previous month; an indicator of the number of received public benefits in the past month including unemployment insurance, Supplemental Security Income, welfare and food stamps; and a measure of car ownership prior to Katrina. Car ownership is important both as a measure of wealth as well as a form of transportation that may have made it easier to evacuate in advance of the hurricane.

Social support

Perceptions of social support were assessed at Times 1 and 2 using eight items from the Social Provisions Scale ( Cutrona & Russell, 1987 ). These items assess the extent to which participants perceive that they have people in their lives who value them and on whom they can rely. Items are rated using a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 ( strongly disagree ) to 4 ( strongly agree ). Cronbach’s alpha of this scale in this study was .84 for Time 1 and .81 for Time 2.

Hurricane experiences

We used three measures of hurricane experiences, two of which were based on individuals’ survey responses. The first measure was a one-item question on respondents’ assessments of the extent of damage to their personal property, rate on a four-point scale ranging from 0 ( minimal ) to 3 ( enormous ). The second measure of hurricane experiences was a scale of the number of hurricane-related stressors experienced. The 17 questions, which assessed stressors experienced in the immediate aftermath of the storm, duplicated those used in a larger survey of the demographic and health characteristics, evacuation and hurricane experiences, and future plans of Hurricane Katrina evacuees. The scale was jointly designed by the Washington Post , the Kaiser Family Foundation, and the Harvard School of Public Health ( Brodie, Weltzien, Altman, Blendon, & Benson, 2006 ). Participants were asked to indicate whether they had experienced any of the following conditions: (1) no fresh water to drink, (2) no food to eat, (3) felt their life was in danger, (4) lacked necessary medicine, (5) lacked necessary medical care, (6) had a family member who lacked necessary medical care, v7) lacked knowledge of safety of their children, and (8) lacked knowledge of safety of their other families members. These questions were asked about both Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita. In addition, participants indicated whether a close friend or family member had lost their life due to the hurricane and its aftermath. A composite score (labeled as “hurricane-related stressors”) was created with the count of affirmative responses to these seventeen items. Inter-item reliability (KR-20) of the exposure scale was .84. The third measure gauges hurricane damage to the respondent’s pre-Katrina home with the flood depth information for each address on September 2, 2005. This provides an objective measure of whether respondents lived in hard-hit areas. We were able to geo-code 372 of the 392 addresses; the remaining respondents used post-office boxes which could not be matched with flood data.

Psychological distress

The K6 scale of nonspecific psychological distress ( Kessler et al., 2002 ) was used to assess DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders within the previous 30 days. The K6 scale has been shown to have good psychometric properties ( Furukawa, Kessler, Slade, & Andrews, 2003 ), and has been used in previous research on the psychological functioning of Hurricane Katrina survivors (e.g., Galea et al., 2007 ; Wang et al., 2007 ). It includes items such as “During the past 30 days, about how often did you feel so depressed that nothing could cheer you up?” Respondents answered on a 5-point rating scale ranging from 0 ( none of the time ) to 4 ( all the time ). Scale scores range from 0 to 24. A previous validation study ( Kessler et al., 2003 ) suggests that a scale score of 0 to 7 can be considered as probable absence of mental illness, a score of 8 to 12 can be considered as probable mild or moderate mental illness (MMI) and a score of 13 or greater can be considered as probable serious mental illness (SMI). Cronbach’s alpha of the K6 scale in this study was .72 for T1 and .80 for T2. Our use of the K6 permits direct comparisons with results in the Kessler et al. study (2006) of mental illness after Hurricane Katrina.

PTSD symptoms

The Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R), a 22-item self-report inventory of symptoms of PTSD ( Weiss & Marmar, 1997 ) with good psychometric properties (e.g., Creamer, Bell, & Failla, 2003 ), was used to measure PTSD symptoms as a result of hurricane experiences. The total score for this scale ranges from 0 to 88. Unlike the other mental health measures we used, this measure was specific to the respondent’s hurricane experiences and was included only in the post-Katrina survey. Participants were asked how often, over the prior week, they were distressed or bothered by experiences related to the hurricane, with sample items including “Any reminders brought back feelings about it,” “Pictures about it popped into my mind,” and “I was jumpy and easily startled.” The scale was rated in a 5-point scale, ranging from 0 ( Not at all ) to 4 ( Extremely ). Cronbach’s alpha reliability for the IES-R scale in this study was .95.

Perceived Stress

The Perceived Stress Scale, or the PSS4 ( Cohen, Karmarck, & Mermelstein, 1983 ; Cohen & Williamson, 1991 ), was used to measure perceptions of stress. This four-item scale, which measures the degree to which events in one’s life are perceived to be stressful, has been widely used in studies of the role of stress in the development of health problems. Participants answered on a 5-point ratingscale ranging from 0 ( never ) to 4 ( very often ). Cronbach’s alpha of the PSS4 scale in this study was .73 for T1 and .75 for T2.

Physical Health

We assessed physical health using three measures. Respondents rated their health on a five-point scale ranging from 1 ( excellent ) to 5 ( poor ). Respondent’s body mass index (BMI) was calculated using a baseline report on height and pre- and post-hurricane reported weight. Finally, we included a count of the number of diagnosed medical conditions, including diabetes, asthma, hypertension, and other conditions.

Missing Data

Although the missing variables were not missing completely at random (MCAR), the missing rate on each item was generally low, under 10%. Missing data was handled with multiple imputation: From the original data, five complete datasets with no missing variables were rendered using Amelia II ( Honaker, King, & Blackwell, 2008 ) in R program. Each analysis was conducted independently across the five datasets. Each result presented below represents an average of the five separate analyses. When appropriate, Rubin’s correction (1987) was performed to derive the standard errors.

All but 8 individuals left their homes for at least one night due to Hurricane Katrina or Rita. Half (50.2%) of the sample reported “enormous” property damage associated with the storm. They experienced, on average, 4.08 hurricane-related stressors ( SD = 3.50). The most common stressor reported was “didn’t know if other family members were safe after Hurricane Katrina” (76.9%), which is consistent with the mass exodus of people from the area at the time of the storm. Substantial numbers also reported experiencing serious deprivation during Hurricane Katrina, including inadequate drinking water (26.0%), inadequate food (34.9%) or feeling that their lives were in danger (32.3%). In addition, 28.6% reported the death of a family member or close friend.

Health and Mental Health Outcomes

Mental health outcomes, as measured by the K6, worsened significantly over the period from before to after the hurricane ( Table 2 ). Based on established cutoffs ( Kessler et al., 2003 ), the prevalence of mild-moderate or serious mental illness (MMI/SMI) rose from 23.5% to 37.5% (McNemar test p < .001), and that of probable serious mental illness (SMI) doubled (6.9% to 14.3%, p < .001). The prevalence of high perceived stress (scale score > 7) rose from 20.2% to 30.9% ( p < .001). All physical health outcomes also experienced statistically significant increases in prevalence (see Table 2 ). PTSD symptoms were not assessed prior to the hurricane. At the time of the post-Katrina survey, 47.7% of participants were classified as having probable PTSD (average IES-R item score > 1.5) ( Weiss & Marmar, 1997 ).

Prevalence of Physical Health and Mental Health Outcomes Before and After Hurricane Katrina

Note . P-value is from a t -test of the hypothesis that the change is equal to 0. CI = confidence interval; IES-R = Impact of Event Scale-Revised; ND = not determined; NA = not applicable.

Hurricane-Related Stressors and Property Damage as Predictors of Mental Health Outcomes

Sequential regression was used to determine if number of hurricane-related stressors, level of property damage, and the flood depth at participant’s pre-Katrina addresses were predictive of post-hurricane mental health outcome variables (i.e., K6, PSS4, and IES-R) and whether the relationship holds after pre-hurricane socio-demographic variables and physical and mental health are taken into account. Controls for socio-demographic characteristics at the time of the hurricane included the respondents’ age, indicators for ethnicity, the number of children, an indicator for whether she or he was single, the logarithm of monthly income, an indicator for the number of forms of received public assistance (i.e., welfare, food stamps, unemployment insurance, or Supplemental Security Income), ownership of working car, and, in addition, the number of months since the hurricane that the follow-up survey took place. Controls for pre-Katrina health measures included each of the five physical and mental health measures obtained prior to the hurricane: K6, PSS4, BMI, number of diagnosable physical health problems, self-reported health, as well as social support. Number of stressors, level of property damage, and flood depth were entered in step 1, demographic variables were entered in step 2, and pre-hurricane physical and mental health problems as well as social support were entered in step 3. Bonferroni type adjustment was made for inflated Type I error; all alphas in model statistics (e.g., R ) were set at .05/6 = .008.

Table 3 shows the results of the six univariate sequential regressions of the mental health and physical health outcomes on the measure of reported property damage, the number of reported hurricane-related stressors, and flood depth on September 2, 2005. When no additional controls were included (step 1), there were large and significant associations between the number of hurricane stressors and all mental health outcomes, while the level of property damage was only predictive of PTSD. Flood depth was not predictive of any mental health outcomes. These associations between loss or stressors and mental health outcomes held even after adjusting for pre-Katrina socio-demographic characteristics, although they generally declined in magnitude ( Table 3 , step 2). The results in the second step may still be biased if loss or number of hurricane-related stressors are associated with pre-Katrina health status, i.e., those with poor baseline health may have been less able to avoid stressors or protect their property against loss. Results in the third step of Table 3 controlled for pre-Katrina physical and mental health status in addition to socio-demographic characteristics, which reduced the parameter estimates for the number of hurricane-related stressors and loss relative to those in the second step. Even controlling for pre-disaster health status, there were large and usually statistically significant adverse effects of loss and stressors on mental health. Notably, many of the pre-Katrina mental and physical health measures are predictive of post-hurricane mental health, showing that the parameter estimates for stressors are biased by their associations with pre-Katrina mental health.

Sequential Regression of Hurricane, Demographic, and Pre-Hurricane Health Variables on Post-Hurricane Health Outcomes

Hurricane-Related Stressors and Property Damage as Predictors of Physical Health Outcomes

There were smaller but still significant associations between stressors and physical health outcomes (see Table 3 ). Even with additional socio-demographic and pre-hurricane physical and mental controls, the number of hurricane-related stressors was strongly associated with the number of diagnosed medical conditions. It was also predictive of BMI and general health rating before any of the additional variables were included. Once they were entered into the equation, however, the associations between number of stressors and BMI and general health rating were no longer significant at p < .05 level. Pre-hurricane physical health measures are strongly associated with post-hurricane physical health.

Pre-Katrina Resources as Predictors of Exposure to Hurricane-Related Stressors

Given that exposure to a greater number of hurricane-related stressor was predictive of worse mental and physical health outcomes, we examined the extent to which pre-Katrina resources predicted the level of exposure. Higher-resource individuals may have been more able to avoid hurricane-related stressors and loss. In addition, resources may have buffered individuals from the adverse effects of stressors and property damage. To examine these hypotheses, we performed a standard multiple regression, with nine indicators of pre-Katrina resources: (1) number of received public benefits in the past month (e.g., welfare benefits, food stamps, unemployment insurance); (2) household income (log transformed); (3) ownership of a working car; (4) level of perceived social support; (5) mental health as measured with K6; (6) level of stress as measured with PSS4; (7) physical health as measured with BMI; (8) number of diagnosed medical condition; and (9) general health rating. We examined whether these pre-hurricane variables predicted fewer stressors and losses. Results (not shown in Table) indicate that owning a car prior to the hurricane ( B = −.82, SE = .039, p < .05), a higher pre-hurricane household income ( B = −.35, SE = .12, p < .01), and a higher level of pre-hurricane perceived social support ( B = −.09, SE = .05, p < .05) were predictive of fewer number of stressors experienced. No other significant relationships were found. Apparently, these resources minimized exposure to stressors.

To test whether these resources buffered the impact of exposure to stressors, we estimated each of the six health and mental health outcome variables, using the nine pre-Katrina resource variables and the number of hurricane-related stressors experienced (first block), as well as the interaction terms between the resource variables and measures of stressors as predictors (second block). Bonferroni correction ( p < .008) was used and continuous predictors were centered prior to analysis. Two significant interaction effects were found: exposure to disaster stressors × car ownership on BMI ( B = 2.99, SE = .10, p < .008) and exposure to disaster stressors × pre-disaster K6 on post-disaster general health rating ( B = −.012, SE = .004, p < .008). We found no other evidence that the effects of exposure to stressors were smaller for those with higher pre-hurricane resources. Although resources may have reduced trauma exposure, they did not appear to have buffered individuals from the mental health effects, and to a lesser extent physical health, of trauma and loss.

Rates of mental and physical illness rose sharply among participants in this study and remained elevated for at least one year following Hurricane Katrina. Fully 13.8% of the sample had probable serious mental illness, up from 6.9% before the hurricane. Moreover, nearly half (47.7%) had probable PTSD, which is higher than rates reported in previous studies of Hurricane Katrina survivors ( Galea et al., 2007 ; Galea et al., 2008 ; Kessler et al., 2008 ) and speaks the particular vulnerabilities of the mostly young, low-income, African American mothers in our study. Indeed, recent studies have revealed higher rates of mental illness among Hurricane Katrina survivors who were single, African American, low-income, Hurricane-exposed, female, or between the ages of 18 and 34 ( Galea et al., 2007 ; Kessler et al., 2008 ). When combined with the additional stressor of having small children, these risk factors conspire to create a high prevalence of PTSD. More generally, these findings are consistent with previous research, which has highlighted the particular burden of disasters that is carried by women of color and the poor ( Adeola, 2009 ; Norris et al., 2002 ).

There were also significant increases in reported fair or poor health, the presence of at least one diagnosed medical condition, and the proportion of our sample that was overweight. Although most previous disaster research has focused on the mental health consequences, these findings suggest that survivors also bear a significant toll to their physical health. Moreover, most earlier studies of both mental and physical health have relied solely on post-Katrina samples or compared separate samples drawn from before and after the hurricane. By taking into account pre-hurricane assessments of both mental and physical health, our findings provide more definitive evidence that mental and physical health declines were coincident with the hurricane.

There were strong adverse effects of hurricane-associated stressors and loss on mental health outcomes: individuals who experienced more stressors and property damage were more likely to experience symptoms of mental illness, PTSD, and marginally higher levels of perceived stress. This is consistent with a previous study in which severe housing damage predicted psychological distress among Hurricane Katrina survivors one year after the storm ( Sastry & Vanlandingham, 2009 ). The effects of loss and stressors on physical health were more muted, although more stressors predicted more diagnosed medical conditions.

Although research indicates that individuals with higher resources experience less loss and fewer stressors as the result of disaster ( Adeola, 2009 ; Sattler et al., 2002 ), we found only mixed support for this pattern. Higher personal income, more perceived social support, and ownership of a car predicted fewer hurricane-related stressors, but other resources, such as receipt of public benefits and mental and physical health, did not. In the case of Hurricane Katrina, the degree of loss was geographically widespread and devastating, producing relatively egalitarian storm damage. These findings are consistent with those of a study of Thai survivors of the 2004 tsunami, which showed that those who were displaced by the tsunami had similar pre-tsunami levels of income and education as those who were not displaced ( Frankenberg, et al., 2008 ; van Griensven et al., 2006 ).

We found very little evidence that baseline economic, social and health resources buffered the adverse effects of hurricane-related stressors and loss on health. The lack of buffering effect is surprising, particularly since the resource variables include a measure of social support, which has a well-documented, positive association with disaster recovery ( Kaniasty & Norris, 1993 ). Weems et al. (2007) found a relatively low association between post-Katrina social support and PSTD symptoms suggesting that social support systems were overwhelmed and had not sufficiently mobilized to mitigate distress. Indeed, in contrast to more circumscribed events, the “collective trauma” of Katrina disrupted some of the very resources that might have been marshaled, with potential support providers either scattered around the country or too burdened themselves to provide ample help to network members ( Fussell, in press ; Galea et al., 2007 ; Weisler et al., 2006 ). Moreover, even in intact networks, an initial mobilization of help is often followed by a deterioration of perceived social support ( Arata, Picou, Johnson, & McNally, 2000 ; Erickson, 1976 ; Kaniasty & Norris, 1993 ; Norris & Kaniasty, 1996 ).

Limitations

In interpreting the results of this study, several limitations should be kept in mind. First, this study relied largely on self-report measures, which are susceptible to subjective biases. Our reliance on a screening tool of nonspecific distress further limits the scope of the study. An analysis of the effects of resources on specific psychiatric problems commonly observed in the aftermath of a disaster (e.g., PTSD, depression, grief) could reveal differential associations informative to the planning of therapeutic interventions for disaster survivors. Moreover, clinical interviews would have been preferable to screening scales of mental disorders, as the latter provide less precise and more conservative estimates ( Kessler et al., 2008 ).

Additionally, our index of social support did not distinguish among types of perceived social support (e.g., emotional, informational, tangible), limiting our ability to discern whether specific forms of support led to fewer hurricane-related stressors. It would have also been helpful to obtain additional descriptive information about the composition of the participants’ social networks, a factor that was shown to influence depressive symptomatology among Hurricane Andrew survivors (Haines, Beggs, & Hurlbert, 2008). Data on the support provided by participants to others in the aftermath of disaster would also be beneficial in future research, as social demands, particularly on women, can increase stress and influence psychological outcomes ( Jones-DeWeever, 2008 ).

Although we were fortunate to locate over 80% of our pre-Katrina sample, those who were not located may have been more marginalized and have suffered even higher levels of psychopathology, potentially rendering our prevalence estimates conservative. Finally, participants in this study are not representative of the entire population affected by the hurricanes, reducing the generalizability of the findings. Nonetheless, by highlighting the experience of poor, predominately African American, single mothers—a population that is faced with multiple stressors and of higher-risk of adverse outcomes—our findings shed light on to a particularly vulnerable, underserved, understudied group.

Implications for Research

In earlier research on Hurricane Katrina, Galea et al. (2007) pointed out that the absence of baseline information limits the ability to draw causal inferences about the effects of hurricane-related stressors on mental health. More generally, baseline information is often lacking in studies on the health and mental health effects of disasters. Our results indicate that controlling for baseline socio-demographic measures, mental health, and physical health results in a modest reduction in estimates of the effects of stressors and loss. Although our broad conclusion is consistent with previous research demonstrating that disaster-related stressors and loss produce significant adverse health and mental health effects, our results suggest that estimates of the mental and physical health consequences of disasters are likely to be upwardly biased, but not so much as to eliminate the effect of the disaster.

Future research should consider the longer-term trajectories of recovery and symptoms. Our findings document increases in mental and physical health problems associated with the hurricanes, which raises questions about the persistence of mental illness over time. Comparisons with other surveys are informative. Galea et al. (2007) found that, five to seven months after the hurricane, the rates of moderate to severe mental illness (MMI/SMI) and severe mental illness (SMI) in their metropolitan New Orleans sample were 32.0% and 17.0%, which are comparable to our rates of 37.2% and 13.8%, respectively, approximately one year post-Katrina. Yet Kessler et al. (2008) reported significant increases in rates of PTSD and SMI from the time period of five to eight months after the hurricane to approximately a year later. It may be the case that, left untreated, PTSD and severe mental illness become more entrenched over time, while more moderate symptoms attenuate. Indeed, in models estimating the population distribution of untreated mental health problems resulting from Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, Schoenbaum et al. (2009) determined that the prevalence of moderate symptoms peaked at between seven and 12 months post-Katrina, while severe symptoms continued to climb over the first year, persisting for 25 to 30 months after the storm. Future research should employ additional waves of post-disaster data to determine the longer-term trajectories and mediators of functioning. Growth curve modeling of change would permit researchers to explore whether the associations between pre-Hurricane resources and symptoms persist over time.

Implications for Intervention

The findings also have important implications for the planning of post-disaster psychological care services. Efforts to identify and provide timely, evidence-based services to those with pre-existing psychological vulnerabilities could potentially prevent or attenuate adverse post-disaster outcomes and the progression into more serious mental illness ( Schoenbaum et al., 2009 ). The persistence of negative mental and physical health symptoms one year after the disaster indicates that long-term treatment is needed. Regrettably, however, many of those in need of care in the months after the hurricane do not receive it ( Chan, Lowe, Zwiebach, & Rhodes, 2008 ; Schoenbaum, 2009 ; Wang et al., 2008 ). This is not unusual—even under normal circumstances the majority of low-income adults in the United States with health problems and serious mental illness do not receive adequate care ( Wang, Demler, & Kessler, 2002 ; Young, Klap, Sherbourne, & Wells, 2001 ). Nonetheless, because survivors of disasters are known to have a higher risk of health and mental health problems, there is compelling reason to target services to members of this group. Most of the participants were single mothers, suggesting that timely intervention could offset problems in younger generations as well. Furthermore, since many survivors of disasters come into contact with service agencies after a disaster, there may be unique opportunities to offer or refer to treatment. The high rates of health and mental health problems among low-income survivors of Hurricane Katrina, coupled with the low rates of care, indicate that this was not successfully accomplished in the case of this natural disaster.

Policy Implications

In addition to health and mental health services, women of color, particularly those with young children, should be provided with additional economic and educational resources throughout the difficult recovery process. Affordable housing would help to promote the immediate safety as well as the long-term stability of fragile young families that are represented in this study. Likewise, the inclusion of women in the post-Katrina work force, both through the skills-training and enforcement of anti-discrimination laws, will help the survivors benefit from the influx of economic resources into the region ( Jones-DeWeever, 2008 ). Finally, educational resources and assistance are vitally needed to ensure that survivors can return to their educational goals with a renewed sense of hope and strength.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by NIH grant R01HD046162, the National Science Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, and the Princeton Center for Economic Policy Studies. We thank Thomas Brock and MDRC.

Jean Rhodes, Department of Psychology, University of Massachusetts; Christian Chan, Department of Psychology, University of Massachusetts; Christina Paxson, Department of Economics, Princeton University; Cecilia Elena Rouse, Department of Economics, Princeton University; Mary Waters, Department of Sociology, Harvard University; Elizabeth Fussell, Department of Sociology, Washington State University.

- Abramson D, Garfield R. On the edge: children and families displaced by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita face a looming medical and mental health crisis. Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health; New York, NY: [Retrieved May 26, 2008]. 2006. from: http://www.ncdp.mailman.columbia.edu/files/On%20the%20Edge%20L-CAFH%20Final%20Report_Columbia%20University.pdf . [ Google Scholar ]

- Adeola FO. Katrina cataclysm: Does duration of residency and prior experience affect impacts, evacuation, and adaptation behavior among survivors? Environment and Behavior. 2009; 41 :459–489. [ Google Scholar ]

- Aptekar L. Environmental Disasters in Global Perspective. GK Hall/ Macmillan; New York: 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- Arata CM, Picou JS, Johnson GD, McNally TS. Coping with technological disaster: An application of the Conservation of Resources model to the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2000; 13 :23–39. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bolin R, Bolton P. Race, Religion, and Ethnicity in Disaster Recovery. University of Colorado, Institute of Behavioral Science; Boulder, CO: 1986. (Monograph No. 42). [ Google Scholar ]