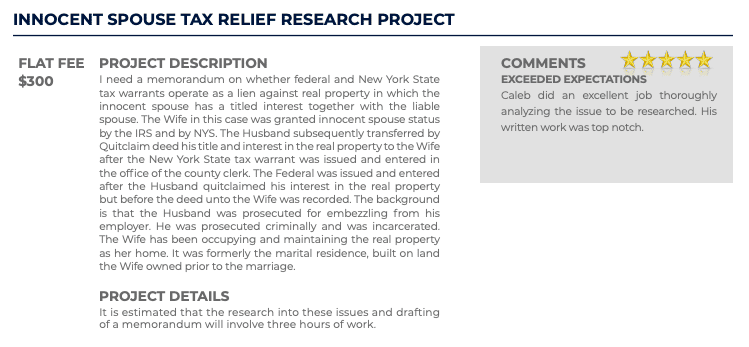

Research Projects

Filter results by.

Legal Research Strategy

Preliminary analysis, organization, secondary sources, primary sources, updating research, identifying an end point, getting help, about this guide.

This guide will walk a beginning researcher though the legal research process step-by-step. These materials are created with the 1L Legal Research & Writing course in mind. However, these resources will also assist upper-level students engaged in any legal research project.

How to Strategize

Legal research must be comprehensive and precise. One contrary source that you miss may invalidate other sources you plan to rely on. Sticking to a strategy will save you time, ensure completeness, and improve your work product.

Follow These Steps

Running Time: 3 minutes, 13 seconds.

Make sure that you don't miss any steps by using our:

- Legal Research Strategy Checklist

If you get stuck at any time during the process, check this out:

- Ten Tips for Moving Beyond the Brick Wall in the Legal Research Process, by Marsha L. Baum

Understanding the Legal Questions

A legal question often originates as a problem or story about a series of events. In law school, these stories are called fact patterns. In practice, facts may arise from a manager or an interview with a potential client. Start by doing the following:

- Read anything you have been given

- Analyze the facts and frame the legal issues

- Assess what you know and need to learn

- Note the jurisdiction and any primary law you have been given

- Generate potential search terms

Jurisdiction

Legal rules will vary depending on where geographically your legal question will be answered. You must determine the jurisdiction in which your claim will be heard. These resources can help you learn more about jurisdiction and how it is determined:

- Legal Treatises on Jurisdiction

- LII Wex Entry on Jurisdiction

This map indicates which states are in each federal appellate circuit:

Getting Started

Once you have begun your research, you will need to keep track of your work. Logging your research will help you to avoid missing sources and explain your research strategy. You will likely be asked to explain your research process when in practice. Researchers can keep paper logs, folders on Westlaw or Lexis, or online citation management platforms.

Organizational Methods

Tracking with paper or excel.

Many researchers create their own tracking charts. Be sure to include:

- Search Date

- Topics/Keywords/Search Strategy

- Citation to Relevant Source Found

- Save Locations

- Follow Up Needed

Consider using the following research log as a starting place:

- Sample Research Log

Tracking with Folders

Westlaw and Lexis offer options to create folders, then save and organize your materials there.

- Lexis Advance Folders

- Westlaw Edge Folders

Tracking with Citation Management Software

For long term projects, platforms such as Zotero, EndNote, Mendeley, or Refworks might be useful. These are good tools to keep your research well organized. Note, however, that none of these platforms substitute for doing your own proper Bluebook citations. Learn more about citation management software on our other research guides:

- Guide to Zotero for Harvard Law Students by Harvard Law School Library Research Services Last Updated Sep 12, 2023 225 views this year

Types of Sources

There are three different types of sources: Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary. When doing legal research you will be using mostly primary and secondary sources. We will explore these different types of sources in the sections below.

Secondary sources often explain legal principles more thoroughly than a single case or statute. Starting with them can help you save time.

Secondary sources are particularly useful for:

- Learning the basics of a particular area of law

- Understanding key terms of art in an area

- Identifying essential cases and statutes

Consider the following when deciding which type of secondary source is right for you:

- Scope/Breadth

- Depth of Treatment

- Currentness/Reliability

For a deep dive into secondary sources visit:

- Secondary Sources: ALRs, Encyclopedias, Law Reviews, Restatements, & Treatises by Catherine Biondo Last Updated Apr 12, 2024 3804 views this year

Legal Dictionaries & Encyclopedias

Legal dictionaries.

Legal dictionaries are similar to other dictionaries that you have likely used before.

- Black's Law Dictionary

- Ballentine's Law Dictionary

Legal Encyclopedias

Legal encyclopedias contain brief, broad summaries of legal topics, providing introductions and explaining terms of art. They also provide citations to primary law and relevant major law review articles.

Here are the two major national encyclopedias:

- American Jurisprudence (AmJur) This resource is also available in Westlaw & Lexis .

- Corpus Juris Secundum (CJS)

Treatises are books on legal topics. These books are a good place to begin your research. They provide explanation, analysis, and citations to the most relevant primary sources. Treatises range from single subject overviews to deep treatments of broad subject areas.

It is important to check the date when the treatise was published. Many are either not updated, or are updated through the release of newer editions.

To find a relevant treatise explore:

- Legal Treatises by Subject by Catherine Biondo Last Updated Apr 12, 2024 2741 views this year

American Law Reports (ALR)

American Law Reports (ALR) contains in-depth articles on narrow topics of the law. ALR articles, are often called annotations. They provide background, analysis, and citations to relevant cases, statutes, articles, and other annotations. ALR annotations are invaluable tools to quickly find primary law on narrow legal questions.

This resource is available in both Westlaw and Lexis:

- American Law Reports on Westlaw (includes index)

- American Law Reports on Lexis

Law Reviews & Journals

Law reviews are scholarly publications, usually edited by law students in conjunction with faculty members. They contain both lengthy articles and shorter essays by professors and lawyers. They also contain comments, notes, or developments in the law written by law students. Articles often focus on new or emerging areas of law and may offer critical commentary. Some law reviews are dedicated to a particular topic while others are general. Occasionally, law reviews will include issues devoted to proceedings of panels and symposia.

Law review and journal articles are extremely narrow and deep with extensive references.

To find law review articles visit:

- Law Journal Library on HeinOnline

- Law Reviews & Journals on LexisNexis

- Law Reviews & Journals on Westlaw

Restatements

Restatements are highly regarded distillations of common law, prepared by the American Law Institute (ALI). ALI is a prestigious organization comprised of judges, professors, and lawyers. They distill the "black letter law" from cases to indicate trends in common law. Resulting in a “restatement” of existing common law into a series of principles or rules. Occasionally, they make recommendations on what a rule of law should be.

Restatements are not primary law. However, they are considered persuasive authority by many courts.

Restatements are organized into chapters, titles, and sections. Sections contain the following:

- a concisely stated rule of law,

- comments to clarify the rule,

- hypothetical examples,

- explanation of purpose, and

- exceptions to the rule

To access restatements visit:

- American Law Institute Library on HeinOnline

- Restatements & Principles of the Law on LexisNexis

- Restatements & Principles of Law on Westlaw

Primary Authority

Primary authority is "authority that issues directly from a law-making body." Authority , Black's Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019). Sources of primary authority include:

- Constitutions

- Statutes

Regulations

Access to primary legal sources is available through:

- Bloomberg Law

- Free & Low Cost Alternatives

Statutes (also called legislation) are "laws enacted by legislative bodies", such as Congress and state legislatures. Statute , Black's Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019).

We typically start primary law research here. If there is a controlling statute, cases you look for later will interpret that law. There are two types of statutes, annotated and unannotated.

Annotated codes are a great place to start your research. They combine statutory language with citations to cases, regulations, secondary sources, and other relevant statutes. This can quickly connect you to the most relevant cases related to a particular law. Unannotated Codes provide only the text of the statute without editorial additions. Unannotated codes, however, are more often considered official and used for citation purposes.

For a deep dive on federal and state statutes, visit:

- Statutes: US and State Codes by Mindy Kent Last Updated Apr 12, 2024 2236 views this year

- 50 State Surveys

Want to learn more about the history or legislative intent of a law? Learn how to get started here:

- Legislative History Get an introduction to legislative histories in less than 5 minutes.

- Federal Legislative History Research Guide

Regulations are rules made by executive departments and agencies. Not every legal question will require you to search regulations. However, many areas of law are affected by regulations. So make sure not to skip this step if they are relevant to your question.

To learn more about working with regulations, visit:

- Administrative Law Research by AJ Blechner Last Updated Apr 12, 2024 461 views this year

Case Basics

In many areas, finding relevant caselaw will comprise a significant part of your research. This Is particularly true in legal areas that rely heavily on common law principles.

Running Time: 3 minutes, 10 seconds.

Unpublished Cases

Up to 86% of federal case opinions are unpublished. You must determine whether your jurisdiction will consider these unpublished cases as persuasive authority. The Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure have an overarching rule, Rule 32.1 Each circuit also has local rules regarding citations to unpublished opinions. You must understand both the Federal Rule and the rule in your jurisdiction.

- Federal and Local Rules of Appellate Procedure 32.1 (Dec. 2021).

- Type of Opinion or Order Filed in Cases Terminated on the Merits, by Circuit (Sept. 2021).

Each state also has its own local rules which can often be accessed through:

- State Bar Associations

- State Courts Websites

First Circuit

- First Circuit Court Rule 32.1.0

Second Circuit

- Second Circuit Court Rule 32.1.1

Third Circuit

- Third Circuit Court Rule 5.7

Fourth Circuit

- Fourth Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Fifth Circuit

- Fifth Circuit Court Rule 47.5

Sixth Circuit

- Sixth Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Seventh Circuit

- Seventh Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Eighth Circuit

- Eighth Circuit Court Rule 32.1A

Ninth Circuit

- Ninth Circuit Court Rule 36-3

Tenth Circuit

- Tenth Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Eleventh Circuit

- Eleventh Circuit Court Rule 32.1

D.C. Circuit

- D.C. Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Federal Circuit

- Federal Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Finding Cases

Headnotes show the key legal points in a case. Legal databases use these headnotes to guide researchers to other cases on the same topic. They also use them to organize concepts explored in cases by subject. Publishers, like Westlaw and Lexis, create headnotes, so they are not consistent across databases.

Headnotes are organized by subject into an outline that allows you to search by subject. This outline is known as a "digest of cases." By browsing or searching the digest you can retrieve all headnotes covering a particular topic. This can help you identify particularly important cases on the relevant subject.

Running Time: 4 minutes, 43 seconds.

Each major legal database has its own digest:

- Topic Navigator (Lexis)

- Key Digest System (Westlaw)

Start by identifying a relevant topic in a digest. Then you can limit those results to your jurisdiction for more relevant results. Sometimes, you can keyword search within only the results on your topic in your jurisdiction. This is a particularly powerful research method.

One Good Case Method

After following the steps above, you will have identified some relevant cases on your topic. You can use good cases you find to locate other cases addressing the same topic. These other cases often apply similar rules to a range of diverse fact patterns.

- in Lexis click "More Like This Headnote"

- in Westlaw click "Cases that Cite This Headnote"

to focus on the terms of art or key words in a particular headnote. You can use this feature to find more cases with similar language and concepts.

Ways to Use Citators

A citator is "a catalogued list of cases, statutes, and other legal sources showing the subsequent history and current precedential value of those sources. Citators allow researchers to verify the authority of a precedent and to find additional sources relating to a given subject." Citator , Black's Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019).

Each major legal database has its own citator. The two most popular are Keycite on Westlaw and Shepard's on Lexis.

- Keycite Information Page

- Shepard's Information Page

Making Sure Your Case is Still Good Law

This video answers common questions about citators:

For step-by-step instructions on how to use Keycite and Shepard's see the following:

- Shepard's Video Tutorial

- Shepard's Handout

- Shepard's Editorial Phrase Dictionary

- KeyCite Video Tutorial

- KeyCite Handout

- KeyCite Editorial Phrase Dictionary

Using Citators For

Citators serve three purposes: (1) case validation, (2) better understanding, and (3) additional research.

Case Validation

Is my case or statute good law?

- Parallel citations

- Prior and subsequent history

- Negative treatment suggesting you should no longer cite to holding.

Better Understanding

Has the law in this area changed?

- Later cases on the same point of law

- Positive treatment, explaining or expanding the law.

- Negative Treatment, narrowing or distinguishing the law.

Track Research

Who is citing and writing about my case or statute?

- Secondary sources that discuss your case or statute.

- Cases in other jurisdictions that discuss your case or statute.

Knowing When to Start Writing

For more guidance on when to stop your research see:

- Terminating Research, by Christina L. Kunz

Automated Services

Automated services can check your work and ensure that you are not missing important resources. You can learn more about several automated brief check services. However, these services are not a replacement for conducting your own diligent research .

- Automated Brief Check Instructional Video

Contact Us!

Ask Us! Submit a question or search our knowledge base.

Chat with us! Chat with a librarian (HLS only)

Email: [email protected]

Contact Historical & Special Collections at [email protected]

Meet with Us Schedule an online consult with a Librarian

Hours Library Hours

Classes View Training Calendar or Request an Insta-Class

Text Ask a Librarian, 617-702-2728

Call Reference & Research Services, 617-495-4516

This guide is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License .

You may reproduce any part of it for noncommercial purposes as long as credit is included and it is shared in the same manner.

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2023 2:56 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/law/researchstrategy

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

Business development

- Billing management software

- Court management software

- Legal calendaring solutions

Practice management & growth

- Project & knowledge management

- Workflow automation software

Corporate & business organization

- Business practice & procedure

Legal forms

- Legal form-building software

Legal data & document management

- Data management

- Data-driven insights

- Document management

- Document storage & retrieval

Drafting software, service & guidance

- Contract services

- Drafting software

- Electronic evidence

Financial management

- Outside counsel spend

Law firm marketing

- Attracting & retaining clients

- Custom legal marketing services

Legal research & guidance

- Anywhere access to reference books

- Due diligence

- Legal research technology

Trial readiness, process & case guidance

- Case management software

- Matter management

Recommended Products

Conduct legal research efficiently and confidently using trusted content, proprietary editorial enhancements, and advanced technology.

Fast track case onboarding and practice with confidence. Tap into a team of experts who create and maintain timely, reliable, and accurate resources so you can jumpstart your work.

A business management tool for legal professionals that automates workflow. Simplify project management, increase profits, and improve client satisfaction.

- All products

Tax & Accounting

Audit & accounting.

- Accounting & financial management

- Audit workflow

- Engagement compilation & review

- Guidance & standards

- Internal audit & controls

- Quality control

Data & document management

- Certificate management

- Data management & mining

- Document storage & organization

Estate planning

- Estate planning & taxation

- Wealth management

Financial planning & analysis

- Financial reporting

Payroll, compensation, pension & benefits

- Payroll & workforce management services

- Healthcare plans

- Billing management

- Client management

- Cost management

- Practice management

- Workflow management

Professional development & education

- Product training & education

- Professional development

Tax planning & preparation

- Financial close

- Income tax compliance

- Tax automation

- Tax compliance

- Tax planning

- Tax preparation

- Sales & use tax

- Transfer pricing

- Fixed asset depreciation

Tax research & guidance

- Federal tax

- State & local tax

- International tax

- Tax laws & regulations

- Partnership taxation

- Research powered by AI

- Specialized industry taxation

- Credits & incentives

- Uncertain tax positions

A powerful tax and accounting research tool. Get more accurate and efficient results with the power of AI, cognitive computing, and machine learning.

Provides a full line of federal, state, and local programs. Save time with tax planning, preparation, and compliance.

Automate workpaper preparation and eliminate data entry

Trade & Supply

Customs & duties management.

- Customs law compliance & administration

Global trade compliance & management

- Global export compliance & management

- Global trade analysis

- Denied party screening

Product & service classification

- Harmonized Tariff System classification

Supply chain & procurement technology

- Foreign-trade zone (FTZ) management

- Supply chain compliance

Software that keeps supply chain data in one central location. Optimize operations, connect with external partners, create reports and keep inventory accurate.

Automate sales and use tax, GST, and VAT compliance. Consolidate multiple country-specific spreadsheets into a single, customizable solution and improve tax filing and return accuracy.

Risk & Fraud

Risk & compliance management.

- Regulatory compliance management

Fraud prevention, detection & investigations

- Fraud prevention technology

Risk management & investigations

- Investigation technology

- Document retrieval & due diligence services

Search volumes of data with intuitive navigation and simple filtering parameters. Prevent, detect, and investigate crime.

Identify patterns of potentially fraudulent behavior with actionable analytics and protect resources and program integrity.

Analyze data to detect, prevent, and mitigate fraud. Focus investigation resources on the highest risks and protect programs by reducing improper payments.

News & Media

Who we serve.

- Broadcasters

- Governments

- Marketers & Advertisers

- Professionals

- Sports Media

- Corporate Communications

- Health & Pharma

- Machine Learning & AI

Content Types

- All Content Types

- Human Interest

- Business & Finance

- Entertainment & Lifestyle

- Reuters Community

- Reuters Plus - Content Studio

- Advertising Solutions

- Sponsorship

- Verification Services

- Action Images

- Reuters Connect

- World News Express

- Reuters Pictures Platform

- API & Feeds

- Reuters.com Platform

Media Solutions

- User Generated Content

- Reuters Ready

- Ready-to-Publish

- Case studies

- Reuters Partners

- Standards & values

- Leadership team

- Reuters Best

- Webinars & online events

Around the globe, with unmatched speed and scale, Reuters Connect gives you the power to serve your audiences in a whole new way.

Reuters Plus, the commercial content studio at the heart of Reuters, builds campaign content that helps you to connect with your audiences in meaningful and hyper-targeted ways.

Reuters.com provides readers with a rich, immersive multimedia experience when accessing the latest fast-moving global news and in-depth reporting.

- Reuters Media Center

- Jurisdiction

- Practice area

- View all legal

- Organization

- View all tax

Featured Products

- Blacks Law Dictionary

- Thomson Reuters ProView

- Recently updated products

- New products

Shop our latest titles

ProView Quickfinder favorite libraries

- Visit legal store

- Visit tax store

APIs by industry

- Risk & Fraud APIs

- Tax & Accounting APIs

- Trade & Supply APIs

Use case library

- Legal API use cases

- Risk & Fraud API use cases

- Tax & Accounting API use cases

- Trade & Supply API use cases

Related sites

United states support.

- Account help & support

- Communities

- Product help & support

- Product training

International support

- Legal UK, Ireland & Europe support

New releases

- Westlaw Precision

- 1040 Quickfinder Handbook

Join a TR community

- ONESOURCE community login

- Checkpoint community login

- CS community login

- TR Community

Free trials & demos

- Westlaw Edge

- Practical Law

- Checkpoint Edge

- Onvio Firm Management

- Proview eReader

How to do legal research in 3 steps

Knowing where to start a difficult legal research project can be a challenge. But if you already understand the basics of legal research, the process can be significantly easier — not to mention quicker.

Solid research skills are crucial to crafting a winning argument. So, whether you are a law school student or a seasoned attorney with years of experience, knowing how to perform legal research is important — including where to start and the steps to follow.

What is legal research, and where do I start?

Black's Law Dictionary defines legal research as “[t]he finding and assembling of authorities that bear on a question of law." But what does that actually mean? It means that legal research is the process you use to identify and find the laws — including statutes, regulations, and court opinions — that apply to the facts of your case.

In most instances, the purpose of legal research is to find support for a specific legal issue or decision. For example, attorneys must conduct legal research if they need court opinions — that is, case law — to back up a legal argument they are making in a motion or brief filed with the court.

Alternatively, lawyers may need legal research to provide clients with accurate legal guidance . In the case of law students, they often use legal research to complete memos and briefs for class. But these are just a few situations in which legal research is necessary.

Why is legal research hard?

Each step — from defining research questions to synthesizing findings — demands critical thinking and rigorous analysis.

1. Identifying the legal issue is not so straightforward. Legal research involves interpreting many legal precedents and theories to justify your questions. Finding the right issue takes time and patience.

2. There's too much to research. Attorneys now face a great deal of case law and statutory material. The sheer volume forces the researcher to be efficient by following a methodology based on a solid foundation of legal knowledge and principles.

3. The law is a fluid doctrine. It changes with time, and staying updated with the latest legal codes, precedents, and statutes means the most resourceful lawyer needs to assess the relevance and importance of new decisions.

Legal research can pose quite a challenge, but professionals can improve it at every stage of the process .

Step 1: Key questions to ask yourself when starting legal research

Before you begin looking for laws and court opinions, you first need to define the scope of your legal research project. There are several key questions you can use to help do this.

What are the facts?

Always gather the essential facts so you know the “who, what, why, when, where, and how” of your case. Take the time to write everything down, especially since you will likely need to include a statement of facts in an eventual filing or brief anyway. Even if you don't think a fact may be relevant now, write it down because it may be relevant later. These facts will also be helpful when identifying your legal issue.

What is the actual legal issue?

You will never know what to research if you don't know what your legal issue is. Does your client need help collecting money from an insurance company following a car accident involving a negligent driver? How about a criminal case involving excluding evidence found during an alleged illegal stop?

No matter the legal research project, you must identify the relevant legal problem and the outcome or relief sought. This information will guide your research so you can stay focused and on topic.

What is the relevant jurisdiction?

Don't cast your net too wide regarding legal research; you should focus on the relevant jurisdiction. For example, does your case deal with federal or state law? If it is state law, which state? You may find a case in California state court that is precisely on point, but it won't be beneficial if your legal project involves New York law.

Where to start legal research: The library, online, or even AI?

In years past, future attorneys were trained in law school to perform research in the library. But now, you can find almost everything from the library — and more — online. While you can certainly still use the library if you want, you will probably be costing yourself valuable time if you do.

When it comes to online research, some people start with free legal research options , including search engines like Google or Bing. But to ensure your legal research is comprehensive, you will want to use an online research service designed specifically for the law, such as Westlaw . Not only do online solutions like Westlaw have all the legal sources you need, but they also include artificial intelligence research features that help make quick work of your research

Step 2: How to find relevant case law and other primary sources of law

Now that you have gathered the facts and know your legal issue, the next step is knowing what to look for. After all, you will need the law to support your legal argument, whether providing guidance to a client or writing an internal memo, brief, or some other legal document.

But what type of law do you need? The answer: primary sources of law. Some of the more important types of primary law include:

- Case law, which are court opinions or decisions issued by federal or state courts

- Statutes, including legislation passed by both the U.S. Congress and state lawmakers

- Regulations, including those issued by either federal or state agencies

- Constitutions, both federal and state

Searching for primary sources of law

So, if it's primary law you want, it makes sense to begin searching there first, right? Not so fast. While you will need primary sources of law to support your case, in many instances, it is much easier — and a more efficient use of your time — to begin your search with secondary sources such as practice guides, treatises, and legal articles.

Why? Because secondary sources provide a thorough overview of legal topics, meaning you don't have to start your research from scratch. After secondary sources, you can move on to primary sources of law.

For example, while no two legal research projects are the same, the order in which you will want to search different types of sources may look something like this:

- Secondary sources . If you are researching a new legal principle or an unfamiliar area of the law, the best place to start is secondary sources, including law journals, practice guides , legal encyclopedias, and treatises. They are a good jumping-off point for legal research since they've already done the work for you. As an added bonus, they can save you additional time since they often identify and cite important statutes and seminal cases.

- Case law . If you have already found some case law in secondary sources, great, you have something to work with. But if not, don't fret. You can still search for relevant case law in a variety of ways, including running a search in a case law research tool.

Once you find a helpful case, you can use it to find others. For example, in Westlaw, most cases contain headnotes that summarize each of the case's important legal issues. These headnotes are also assigned a Key Number based on the topic associated with that legal issue. So, once you find a good case, you can use the headnotes and Key Numbers within it to quickly find more relevant case law.

- Statutes and regulations . In many instances, secondary sources and case law list the statutes and regulations relevant to your legal issue. But if you haven't found anything yet, you can still search for statutes and regs online like you do with cases.

Once you know which statute or reg is pertinent to your case, pull up the annotated version on Westlaw. Why the annotated version? Because the annotations will include vital information, such as a list of important cases that cite your statute or reg. Sometimes, these cases are even organized by topic — just one more way to find the case law you need to support your legal argument.

Keep in mind, though, that legal research isn't always a linear process. You may start out going from source to source as outlined above and then find yourself needing to go back to secondary sources once you have a better grasp of the legal issue. In other instances, you may even find the answer you are looking for in a source not listed above, like a sample brief filed with the court by another attorney. Ultimately, you need to go where the information takes you.

Step 3: Make sure you are using ‘good’ law

One of the most important steps with every legal research project is to verify that you are using “good" law — meaning a court hasn't invalidated it or struck it down in some way. After all, it probably won't look good to a judge if you cite a case that has been overruled or use a statute deemed unconstitutional. It doesn't necessarily mean you can never cite these sources; you just need to take a closer look before you do.

The simplest way to find out if something is still good law is to use a legal tool known as a citator, which will show you subsequent cases that have cited your source as well as any negative history, including if it has been overruled, reversed, questioned, or merely differentiated.

For instance, if a case, statute, or regulation has any negative history — and therefore may no longer be good law — KeyCite, the citator on Westlaw, will warn you. Specifically, KeyCite will show a flag or icon at the top of the document, along with a little blurb about the negative history. This alert system allows you to quickly know if there may be anything you need to worry about.

Some examples of these flags and icons include:

- A red flag on a case warns you it is no longer good for at least one point of law, meaning it may have been overruled or reversed on appeal.

- A yellow flag on a case warns that it has some negative history but is not expressly overruled or reversed, meaning another court may have criticized it or pointed out the holding was limited to a specific fact pattern.

- A blue-striped flag on a case warns you that it has been appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court or the U.S. Court of Appeals.

- The KeyCite Overruling Risk icon on a case warns you that the case may be implicitly undermined because it relies on another case that has been overruled.

Another bonus of using a citator like KeyCite is that it also provides a list of other cases that merely cite your source — it can lead to additional sources you previously didn't know about.

Perseverance is vital when it comes to legal research

Given that legal research is a complex process, it will likely come as no surprise that this guide cannot provide everything you need to know.

There is a reason why there are entire law school courses and countless books focused solely on legal research methodology. In fact, many attorneys will spend their entire careers honing their research skills — and even then, they may not have perfected the process.

So, if you are just beginning, don't get discouraged if you find legal research difficult — almost everyone does at first. With enough time, patience, and dedication, you can master the art of legal research.

Thomson Reuters originally published this article on November 10, 2020.

Related insights

Westlaw tip of the week: Checking cases with KeyCite

Why legislative history matters when crafting a winning argument

Case law research tools: The most useful free and paid offerings

Request a trial and experience the fastest way to find what you need

- Smokeball Legal Community

- CLEs, Webinars & Events

- E-Books, Guides & Case Studies

- Smokeball ROI Calculator

- Hacking Law Firm Success

- Why Smokeball

- Referral Program

- Diversity and Inclusion

Client Login

Legal Research 101: A Step-by-Step Guide

Legal Tech Stack

Rebecca Spiegel

March 20, 2023

Legal research is crucial for lawyers, paralegals, and law students. And it can be a struggle for even the most experienced legal professionals—but it can be overwhelming for beginners.

In this blog post, we’ll cover the basics of legal research, including primary and secondary sources, case law, statutes, regulations, and more. Whether just starting your legal career or looking to refresh your knowledge, this guide will provide a solid foundation for effective legal research. Let’s dive in!

What is legal research?

Legal research is the process of identifying and analyzing legal information to support a legal argument or decision. It involves searching for and analyzing primary and secondary sources, such as case law, statutes, regulations, legal dictionaries, treatises, and law review articles.

There are many reasons you might conduct legal research, including:

- Looking for case law that backs up your motion or brief

- Identifying case law that refutes an opposing argument

- Supporting the general narrative of your case

- Providing legal counsel to clients

- Putting together a memo or brief for law school

Effective legal research can make all the difference in the success of a legal case or argument. Legal research is essential for lawyers, judges, law students, paralegals, and anyone involved in the legal industry. It requires critical thinking, analytical skills, and attention to detail to ensure that legal information is accurate, relevant, and up to date.

How to do legal research

Legal research can be overwhelming and takes many forms depending on your goals. Here are some general steps you’ll likely take in any given legal research project.

Step 1: Gather and understand the key facts of your legal case

A solid legal case starts with strong legal research. So before scouring case laws and court opinions for data, stepping back and setting a few goals is important. What are you hoping to accomplish with this case, and what key facts will support your argument?

Once you understand the information you’re looking for, ask yourself these questions to start your research on the right foot.

Key questions to ask yourself before starting legal research

What are the basics.

Whether working with a client or writing a law brief for school, always start with the basics. What’s the “who, what, why, when, where, and how?”

Write a quick summary, especially since you’ll likely need it for a statement of facts in a filing or legal brief. You never know what facts might be helpful later! Even if details you think may not be relevant now, include them on your list.

Pro tip: Record your essential facts in a case management tool . While it may be tempting to skip this step, a case management tool will help you streamline your legal process, reduce human error, and save you time in the long run as you juggle multiple clients.

What's the legal issue?

Next, identify the actual legal issue you’re hoping to solve. Does your client need help to settle a property ownership dispute? Or are they pursuing worker’s compensation for an accident that happened on the clock?

No matter the legal research project, having a clear sense of the legal problem is crucial to determining your desired outcome. A clear end goal will help you stay focused and on topic throughout your casework.

What jurisdiction are you operating in?

When it comes to legal research, casting a wide net can be a bad thing. There are endless amounts of court opinions and legal databases that you could sort through. But your research will have been for naught if they’re irrelevant to your case.

That’s why it’s necessary to identify the relevant jurisdiction for your case. Does it deal with federal or state law? If a state, which one? You might find applicable case law from a Washington state supreme court that supports your argument, but it won’t hold up with opposing counsel if you’re operating in Montana.

Create a research plan

Now, it’s time to think about where you’ll go to perform legal research. While Google might be a good start for some of the basic facts you need, it’s probably not enough. Legal encyclopedias and law journals have traditionally supported lawyers as they’ve conducted research, but technology has also made the process a lot easier now. Law firms might invest in an online legal research service to comb through relevant statutes legal topics.

Step 2: Gather sources of law

The next step as you conduct legal research is to gather relevant law sources.

There are two different kinds of sources: primary law and secondary law. As you start your research, it's important to note that you should start with secondary law materials.

Why? Because these sources will help you understand what experts have to say about a legal topic before you start your case and investigate primary materials. Think of it as building a knowledgeable foundation for your argument: you'll sound smarter (and win your case) if you know what experts are saying about the legal topic you're researching.

What are secondary legal sources?

Secondary legal sources are publications that analyze, interpret, or explain primary legal sources. They are not the law itself, but rather resources that provide commentary, context, or background information on the law. Examples of secondary legal sources include:

- legal encyclopedias and dictionaries

- law review articles

- legal treatises

- practice guides

- annotated codes

- Law journals

- Legal news

- Jury instructions

Secondary sources can be helpful for several reasons, including providing a deeper understanding of legal concepts, identifying key issues and arguments, and finding additional primary sources. They can also help determine the law's current state and identify any changes or developments in legal trends or interpretations.

It is important to note that secondary legal sources are not authoritative sources of law and should not be relied upon as legal precedent. Instead, they can be used to support and supplement primary legal sources in legal research and analysis.

What are primary legal sources?

Primary legal sources establish legal rules and principles. The existing laws, regulations, and judicial decisions create, interpret, and enforce legal principles and rules. Examples of primary legal sources include:

- Statutes: Written laws enacted by legislative bodies at the federal, state, or local level.

- Case law: Decisions made by courts in the course of resolving disputes.

- Regulations: Rules and standards issued by administrative agencies to implement and interpret statutes.

- Constitutions: Written documents that establish the basic principles and structure of a government.

Primary legal sources are considered the most authoritative sources of law and are relied upon to determine legal rights and obligations. They are often used in legal research and analysis to interpret and apply the law to specific cases or situations. It is important to note that primary legal sources can be complex and require careful analysis and interpretation to determine their meaning and scope.

Step 3: Make sure you’re using “good” law

Another important step in the legal research process is to verify that any cases and statutes you use are still "good law" — in other words, that they're still valid and relevant. Overruled or unconstitutional statutes won't help you win any cases.

Can older cases still be considered "good?"

Whenever possible, it's a good idea to use the most recent cases possible. They're more likely to be relevant to your case and are less likely to have been rendered obsolete. That said, recency isn't mandatory.

A case that's 30 years old could still be considered "good law" if it hasn't been overruled or otherwise made irrelevant. If it fits with the facts of your case and falls within your jurisdiction, it could still be helpful for your argument!

Use a citator

A citator can help you check to see if your research contains "good" law. Citators verify legal authority by providing the history and precedent for any cases, statutes, and legal sources you use.

Most legal databases have their own citator tools, which flag negative materials and can help you evaluate whether a case is "good" law. Citator tools can also help you find other relevant cases that cite the opinion in question.

Step 4: Sum up results and look for gaps

Once your initial legal research process is complete, compile it into a legal memorandum. This will help you identify any gaps in the facts you've collected and anticipate any additional information you might need.

A good legal memorandum:

- States the facts of the case

- Identifies the issue

- Applies “good” law to the facts

- Predicts any counterpoints

- Assesses the outcome of the case

The best tips and strategies for conducting legal research

Conducting legal research can be a challenging task, requiring both expertise and a strategic approach. Here are our best tips and strategies for conducting effective legal research, to help you to navigate the complexities of the legal system with confidence.

Think about the opposing counsel’s arguments

Consider your case from all angles. What will your opposition's arguments look like? Think competitively as you perform legal research, and search for facts that will refute any legal basis the opposing party may claim.

Don't stop researching

Your research isn't over until your assignment is submitted or your case is closed. Don't cut corners and use all of the time you have available to you. You never know when you're going to find a vital piece of research that could positively impact your case.

Take advantage of legal research tools

In recent years, legal research technology has transformed the way lawyers and legal professionals conduct research. With the help of advanced search algorithms, machine learning, and natural language processing, legal research technology can help to streamline the research process, increase efficiency, and provide more accurate and comprehensive results.

Here are a few tools that help streamline the legal research process:

- ROSS Intelligence is a legal research platform that's driven by AI. ROSS lets you highlight statements in your memorandums and briefs to instantly search for cases and statutes that cover similar laws. You can also use ROSS to look for negative case treatment in your pleadings and law briefs.

- Casetext’s CARA AI search technology and automated review tools help lawyers speed up their legal searches. You can use Casetext to start your research with a complaint or legal brief, and find highly relevant, tailored search results and resources. Not only does Casetext find facts and legal issues, but it will filter results to the jurisdiction you're looking for. Casetext’s citator also makes it easier to check and flag any bad law.

Document your research with law practice management software

A poor documentation system can ruin your entire legal research process. Law practice management software can help you record your research in an efficient, streamlined, and automated way—so that no detail ever falls through the cracks.

Smokeball's legal case management software keeps your entire law firm organized by helping you collect details during client intake, saving them to the correct case matter and auto-populating the documents you need with the correct information. And our Client Portal helps you communicate with clients, request more details when you need it, and share research results.

Download Now: Getting Automated: An End-to-End Guide to Law Firm Automation

In conclusion, legal research is an essential skill for lawyers, law students, and other legal professionals. By mastering the basics of legal research, including identifying primary and secondary legal sources, using legal research tools effectively, and developing a strategic approach to research, legal professionals can improve the quality of their work and provide better outcomes for their clients.

With the help of Smokeball's legal practice management software, legal research can become a more efficient, and effective process. We're here to support your law firm from the initial research stage to client communication to i nvoicing and billing when your case is closed.

FAQs about legal research

What is shepardizing in legal research.

Shepardizing is a process used in legal research to determine whether a particular case or statute is still good law. It involves checking the history and subsequent treatment of the case or statute to ensure that it has not been overruled, superseded, or otherwise invalidated. Shepardizing is an important step in legal research to ensure the accuracy and relevance of the sources being used.

Can I use Google for legal research?

Yes, Google can be a great first step to find basic details for your case. Google Scholar is also a good resource for lawyers conducting legal research. It contains an extensive database of state and federal cases, with superior search functionality.

However, Google is clear that the resources they provide are not vetted or approved by a legal professional:

“Legal opinions in Google Scholar are provided for informational purposes only and should not be relied on as a substitute for legal advice from a licensed lawyer. Google™ does not warrant that the information is complete or accurate.”

So it's important to verify that any of the sources you pull from Google Scholar are accurate, and are considered "good" law.

How to do legal research as a paralegal?

A good paralegal will follow the steps of D.I.S.P.U.T.E . to define the legal issues of the case and find relevant case law.

- D id you identify all of the relevant parties involved in the case?

- I s the location important?

- S ome items or objects may be important to the case.

- P ut the events in chronological order.

- U nderstanding the events will give you the basis of action or the issues that are involved in the case.

- T ake into consideration the opposing counsel’s arguments in the case.

- E valuate the legal remedy or the relief sought in the case.

Building Your Legal Tech Stack: A Legal Technology Starter Guide

Learn more about smokeball.

- Schedule your personalized demo

- Get your free trial of Smokeball Start

- Explore our features

- Meet our team

- View pricing

Related Product Content

Learn more about smokeball document management for law firms, book your free demo.

Ready to see how Smokeball client intake software helps you Run Your Best Firm? Schedule your free demo!

This field is required.

Your personal data will be kept confidential. For more information about how we collect, store, and use your personal data, please read our Privacy Policy and Terms and Conditions .

Share this legal blog on social media.

Director of Content & Social

More from the Smokeball blog

What Is an Attorney Trust Account?

Attorney trust accounts are critical to making sure that money given to lawyers by clients or third-parties is kept safe and isn’t comingled with law firm funds or used incorrectly. Click to learn about trust fund lawyers, IOLTA account rules and what an attorney trust account is.

.png)

Law firms are entering a new era, and their ethics are shifting. Here’s how legal ethics are changing in 2023. Law firms, small and large, are building their legal tech stack. But what’s the most important legal technology to know about? Here’s a guide to get you started.

Bill Better From Anywhere: How Legal Billing Software Boosts Your Profitability

Thankfully, legal billing technology can manage most of the manual tasks and heavy lifting. Your firm can bill from anywhere and get paid at any time, no matter where your team (or clients) are located.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get regular updates, webinar invites and helpful content, delivered directly to your inbox!

- Platform Overview All-in-one legal research and workflow software

- Legal Research Unmetered access to primary and secondary sources

- Workflow Tools AI-powered tools for smarter workflows

- News & Analysis Paywall-free premium Bloomberg news and coverage

- Practical Guidance Ready-to-use guidance for any legal task

- Contract Solutions New: Streamlined contract workflow platform

- Introducing Contract Solutions Experience contract simplicity

- Watch product demo

- Law Firms Find everything you need to serve your clients

- In-House Counsel Expand expertise, reduce cost, and save time

- Government Get unlimited access to state and federal coverage

- Law Schools Succeed in school and prepare for practice

- Customer Cost Savings and Benefits See why GCs and CLOs choose Bloomberg Law

- Getting Started Experience one platform, one price, and continuous innovation

- Our Initiatives Empower the next generation of lawyers

- Careers Explore alternative law careers and join our team

- Press Releases See our latest news and product updates

- DEI Framework Raising the bar for law firms

- Request Pricing

- Legal Solutions

How to Conduct Legal Research

September 21, 2021

Conducting legal research can challenge even the most skilled law practitioners.

As laws evolve across jurisdictions, it can be a difficult to keep pace with every legal development. Equally daunting is the ability to track and glean insights into stakeholder strategies and legal responses. Without quick and easy access to the right tools, the legal research upon which case strategy hinges may face cost, personnel, and litigation outcome challenges.

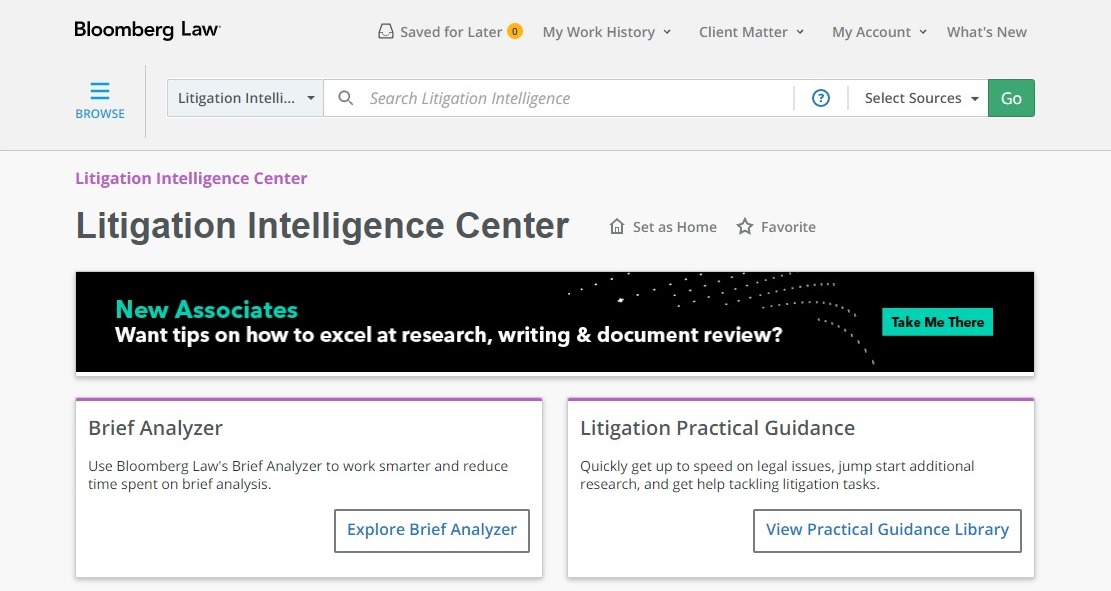

Bloomberg Law’s artificial intelligence-driven tools drastically reduce the time to perform legal research. Whether you seek quick answers to legal research definitions, or general guidance on the legal research process, Bloomberg Law’s Core Litigation Skills Toolkit has you covered.

What is legal research?

Legal research is the process of uncovering and understanding all of the legal precedents, laws, regulations, and other legal authorities that apply in a case and inform an attorney’s course of action.

Legal research often involves case law research, which is the practice of identifying and interpreting the most relevant cases concerning the topic at issue. Legal research can also involve a deep dive into a judge’s past rulings or opposing counsel’s record of success.

Research is not a process that has a finite start and end, but remains ongoing throughout every phase of a legal matter. It is a cornerstone of a litigator’s skills.

[Learn how our integrated, time-saving litigation research tools allow litigators to streamline their work and get answers quickly.]

Where do I begin my legal research?

Beginning your legal research will look different for each assignment. At the outset, ensure that you understand your goal by asking questions and taking careful notes. Ask about background case information, logistical issues such as filing deadlines, the client/matter number, and billing instructions.

It’s also important to consider how your legal research will be used. Is the research to be used for a pending motion? If you are helping with a motion for summary judgment, for example, your goal is to find cases that are in the same procedural posture as yours and come out favorably for your side (i.e., if your client is the one filing the motion, try to find cases where a motion for summary judgment was granted, not denied). Keep in mind the burden of proof for different kinds of motions.

Finally, but no less important, assess the key facts of the case. Who are the relevant parties? Where is the jurisdiction? Who is the judge? Note all case details that come to mind.

What if I’m new to the practice area or specific legal issue?

While conducting legal research, it is easy to go down rabbit holes. Resist the urge to start by reviewing individual cases, which may prove irrelevant. Start instead with secondary sources, which often provide a prevailing statement of the law for a specific topic. These sources will save time and orient you to the area of the law and key issues.

Litigation Practical Guidance provides the essentials including step-by-step guidance, expert legal analysis, and a preview of next steps. Source citations are included in all Practical Guidance, and you can filter Points of Law, Smart Code®, and court opinions searches to get the jurisdiction-specific cases or statutes you need.

Searching across Points of Law will help to get your bearings on an issue before diving into reading the cases in full. Points of Law uses machine learning to identify key legal principles expressed in court opinions, which are easily searchable by keyword and jurisdiction. This tool helps you quickly find other cases that have expressed the same Point of Law, and directs you to related Points of Law that might be relevant to your research. It is automatically updated with the most recent opinions, saving you time and helping you quickly drill down to the relevant cases.

How do I respond to the opposing side’s brief?

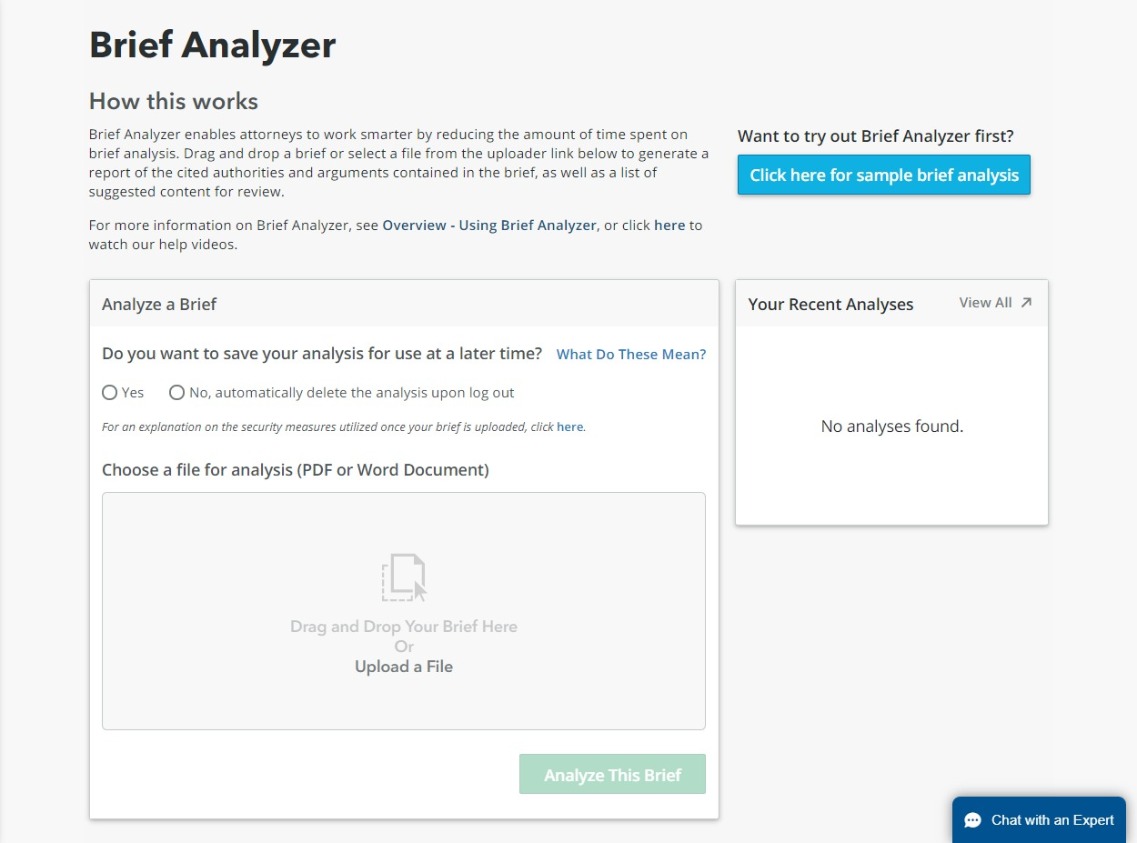

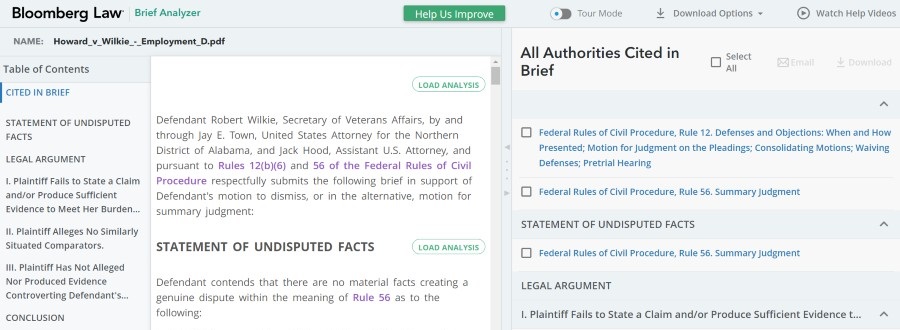

Whether a brief is yours or that of the opposing party, Bloomberg Law’s Brief Analyzer is an essential component in the legal research process. It reduces the time spent analyzing a brief, identifying relevant authorities, and preparing a solid response.

To start, navigate to Brief Analyzer available from the Bloomberg Law homepage, within the Litigation Intelligence Center , or from Docket Key search results for briefs.

Simply upload the opposing side’s brief into the tool, and Brief Analyzer will generate a report of the cited authorities and arguments contained in the brief.

You can easily view a comparison with the brief and analysis side by side. It will also point you directly to relevant cases, Points of Law, and Practical Guidance to jump start your research.

[ How to Write a Legal Brief – Learn how to shorten the legal research cycle and give your legal brief a competitive advantage.]

How to optimize your search.

Crafting searches is a critical skill when it comes to legal research. Although many legal research platforms, including Bloomberg Law, offer natural language searching, terms and connectors (also called Boolean) searching is still a vital legal research skill and should be used when searching across court opinions, dockets, Points of Law, and other primary and secondary sources.

When you conduct a natural language search, the search engine applies algorithms to rank your results. Why a certain case is ranked as it is may not be obvious. This makes it harder to interpret whether the search is giving you everything you need. It is also harder to efficiently and effectively manipulate your search terms to zero in on the results you want. Using Boolean searching gives you better control over your search and greater confidence in your results.

The good news? Bloomberg Law does not charge by the search for court opinion searches. If your initial search was much too broad or much too narrow, you do not have to worry about immediately running a new and improved search.

Follow these tips when beginning a search to ensure that you do not miss relevant materials:

- Make sure you do not have typos in your search string.

- Search the appropriate source or section of the research platform. It is possible to search only within a practice area, jurisdiction, secondary resource, or other grouping of materials.

- Make sure you know which terms and connectors are utilized by the platform you are working on and what they mean – there is no uniform standard set of terms of connectors utilized by all platforms.

- Include in your search all possible terms the court might use, or alternate ways the court may address an issue. It is best to group the alternatives together within a parenthetical, connected by OR between each term.

- Consider including single and multiple character wildcards when relevant. Using a single character wildcard (an asterisk) and/or a multiple character wildcard (an exclamation point) helps you capture all word variations – even those you might not have envisioned.

- Try using a tool that helps you find additional relevant case law. When you find relevant authority, use BCITE on Bloomberg Law to find all other cases and/or sources that cite back to that case. When in BCITE, click on the Citing Documents tab, and search by keyword to narrow the results. Alternatively, you can use the court’s language or ruling to search Points of Law and find other cases that addressed the same issue or reached the same ruling.

[Bloomberg Law subscribers can access a complete checklist of search term best practices . Not a subscriber? Request a Demo .]

How can legal research help with drafting or strategy?

Before drafting a motion or brief, search for examples of what firm lawyers filed with the court in similar cases. You can likely find recent examples in your firm’s internal document system or search Bloomberg Law’s dockets. If possible, look for things filed before the same judge so you can get a quick check on rules/procedures to be followed (and by the same partner when possible so you can get an idea of their style preferences).

Careful docket search provides a wealth of information about relevant cases, jurisdictions, judges, and opposing counsel. On Bloomberg Law, type “Dockets Search” in the Go bar or find the dockets search box in the Litigation Intelligence Center .

If you do not know the specific docket number and/or court, use the docket search functionality Docket Key . Select from any of 20 categories, including motions, briefs, and orders, across all 94 federal district courts, to pinpoint the exact filing of choice.

Dockets can also help you access lots of information to guide your case strategy. For example, if you are considering filing a particular type of motion, such as a sanctions motion, you can use dockets to help determine how frequently your judge grants sanctions motions. You can also use dockets to see how similar cases before your judge proceeded through discovery.

If you are researching expert witnesses, you can use dockets to help determine if the expert has been recently excluded from a case, or whether their opinion has been limited. If so, this will help you determine whether the expert is a good fit for your case.

Dockets are a powerful research tool that allow you to search across filings to support your argument. Stay apprised of docket updates with the “Create Alert” option on Bloomberg Law.

Dive deeper into competitive research.

For even more competitive research insights, dive into Bloomberg Law’s Litigation Analytics – this is available in the Litigation tab on the homepage. Data here helps attorneys develop litigation strategy, predict possible outcomes, and better advise clients.

To start, under Litigation Analytics , leverage the Attorney tab to view case history and preview legal strategies the opposition may practice against you. Also, within Litigation Analytics, use the Court tab to get aggregate motion and appeal outcome rates across all federal courts, with the option to run comparisons across jurisdictions, and filter by company, law firm, and attorney.

Use the Judge tab to glean insights from cited opinions, and past and current decisions by motion and appeal outcomes. Also view litigation analytics in the right rail of court opinions.

Docket search can also offer intel on your opponent. Has your opponent filed similar lawsuits or made similar arguments before? How did those cases pan out? You can learn a lot about an opponent from past appearances in court.

How do I validate case law citations?

Checking the status of case law is essential in legal research. Rely on Bloomberg Law’s proprietary citator, BCITE. This time-saving tool lets you know if a case is still good law.

Under each court opinion, simply look to the right rail. There, you will see a thumbnail icon for “BCITE Analysis.” Click on the icon, and you will be provided quick links to direct history (opinions that affect or are affected by the outcome of the case at issue); case analysis (citing cases, with filter and search options), table of authorities, and citing documents.

How should I use technology to improve my legal research?

A significant benefit of digital research platforms and analytics is increased efficiency. Modern legal research technology helps attorneys sift through thousands of cases quickly and comprehensively. These products can also help aggregate or summarize data in a way that is more useful and make associations instantaneously.

For example, before litigation analytics were common, a partner may have asked a junior associate to find all summary judgment motions ruled on by a specific judge to determine how often that judge grants or denies them. The attorney could have done so by manually searching over PACER and/or by searching through court opinions, but that would take a long time. Now, Litigation Analytics can aggregate that data and provide an answer in seconds. Understanding that such products exist can be a game changer. Automating parts of the research process frees up time and effort for other activities that benefit the client and makes legal research and writing more efficient.

[Read our article: Six ways legal technology aids your litigation workflow .]

Tools like Points of Law , dockets and Brief Analyzer can also increase efficiency, especially when narrowing your research to confirm that you found everything on point. In the past, attorneys had to spend many hours (and lots of money) running multiple court opinion searches to ensure they did not miss a case on point. Now, there are tools that can dramatically speed up that process. For example, running a search over Points of Law can immediately direct you to other cases that discuss that same legal principle.

However, it’s important to remember that digital research and analytical tools should be seen as enhancing the legal research experience, not displacing the review, analysis, and judgment of an attorney. An attorney uses his or her knowledge of their client, the facts, the precedent, expert opinions, and his or her own experiences to predict the likely result in a given matter. Digital research products enhance this process by providing more data on a wider array of variables so that an attorney can take even more information into consideration.

[Get all your questions answered, request a Bloomberg Law demo , and more.]

Recommended for you

See bloomberg law in action.

From live events to in-depth reports, discover singular thought leadership from Bloomberg Law. Our network of expert analysts is always on the case – so you can make yours. Request a demo to see it for yourself.

Harvard Empirical Legal Studies Series

5005 Wasserstein Hall (WCC) 1585 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA02138

Contact the Graduate Program

The Harvard Empirical Legal Studies (HELS) Series explores a range of empirical methods, both qualitative and quantitative, and their application in legal scholarship in different areas of the law. It is a platform for engaging with current empirical research, hearing from leading scholars working in a variety of fields, and developing ideas and empirical projects.

HELS is open to all students and scholars with an interest in empirical research. No prior background in empirical legal research is necessary. If you would like to join HELS and receive information about our sessions, please subscribe to our mailing list by completing the HELS mailing list form .

If you have any questions, do not hesitate to contact the current HELS coordinator, Tiran Bajgiran.

All times are provided in U.S. Eastern Time (UTC/GMT-0400).

Spring 2024 Sessions

Empire and the shaping of american constitutional law.

Aziz Rana, BC Law

Monday, Mar. 25, 12:15 PM Lewis 202

This talk will explore how US imperial practice has influenced the methods and boundaries of American constitutional study.

Historical Approaches to Neoliberal Legality

Quinn Slobodian, Boston University

Thursday, Mar. 28, 12:15 PM Lewis 202

Fall 2023 Sessions

On critical quantitative methods.

Hendrik Theine , WU, Vienna/Univ. of Pennsylvania Monday, Nov. 6, 12:30 PM Lewis 202

Economic inequality is a profound challenge in the United States. Both income and wealth inequality increased remarkably since the 1980s. This growing concentration of economic inequality creates real-world political and societal problems which are increasingly reflected by social science scholarship. Among those detriments is for instance the increasing economic and political power of the super-rich. The research at hand takes a new radical look at media discourses of economic inequality over four decades in various elite US newspapers by way of quantitative critical discourse analysis. It shows that up until recently, there was minimal media coverage of economic inequality, but interest has steadily increased since then. Initially, the focus was primarily on income inequality, but over time, it has expanded to encompass broader issues of inequality. Notably, the discourse on economic inequality is significantly influenced by party politics and elections. The study also highlights certain limitations in the discourse. Critiques of inequality tend to remain at a general level, discussing concepts like capitalist and racial inequality. There is relatively less focus on policy-related discussions, such as tax reform, or discussions centered around specific actors, like the wealthy and their charitable contributions.

Spring 2023 Sessions

How to conduct qualitative empirical legal scholarship.

Jessica Silbey , Professor of Law at Boston University Yanakakis Faculty Research Scholar

Friday, March 31, 12:30 PM WCC 3034

This session explores the benefits and some limitations of qualitative research methods to study intellectual property law. It compares quantitative research methods and the economic analysis of law in the same field as other kinds of empirical inquiry that are helpful in collaboration but limited in isolation. Creativity and innovation, the practices intellectual property law purports to regulate, are not amenable to quantification without identifying qualitative variables. The lessons from this session apply across fields of legal research.

Fall 2022 Sessions

How to read quantitative empirical legal scholarship.

Holger Spamann , Lawrence R. Grove Professor of Law

Friday, September 13, 12:30 PM WCC 3007

As legal scholars, what tools do we need to read critically and engage productively with quantitative empirical scholarship? In the first session of the 2022-2023 Harvard Empirical Legal Studies Series, Harvard Law School Professor Holger Spamann will compare and discuss different quantitative studies. This session will be a first approximation to be able to understand and eventually produce empirical legal scholarship. All students and scholars interested in empirical research are welcome and encouraged to attend.

How do People Learn from Not Being Caught? An Experimental Investigation of a “Non-Occurrence Bias”

Tom Zur , John M. Olin Fellow and SJD candidate, HLS

Friday, November 4, 2:00 PM WCC 3007

The law and economics literature on specific deterrence has long theorized that offenders rationally learn from being caught and sanctioned. This paper presents evidence from a randomized controlled trial showing that offenders learn differently when not being caught as compared to being caught, which we call a “non-occurrence bias.” This implies that the socially optimal level of investment in law enforcement should be lower than stipulated by rational choice theory, even on grounds of deterrence alone.

Empirical Legal Research: Using Data and Methodology to Craft a Research Agenda

Florencia Marotta-Wurgler , NYU Boxer Family Professor of Law Faculty Director, NYU Law in Buenos Aires

Monday, November 14, 12:30 PM Lewis 202

Using a series of examples, this discussion will focus on strategies to conduct empirical legal research and develop a robust research agenda. Topics will include creating a data set and leveraging to answer unexplored questions, developing meaningful methodologies to address legal questions, building on existing work to develop a robust research agenda, and engaging the process of automation and scaling up to develop large scale data sets using machine learning approaches.

Resources for Empirical Research

- HLS Library Empirical Research Service

- Harvard Institute for Quantitative Social Research (IQSS)

- Harvard Committee on the Use of Human Subjects

- Qualtrics Harvard

- Harvard Kennedy School Behavioral Insights Group

Past HELS Sessions

Holger Spamann (Lawrence R. Grove Professor of Law) – How to Read Quantitative Empirical Legal Scholarship?

Katerina Linos (Professor of Law at UC Berkeley School of Law) – Qualitative Methods for Law Review Writing

Aziza Ahmed (Professor of Law at UC Irvine School of Law) – Risk and Rage: How Feminists Transformed the Law and Science of AIDS

Amy Kapczynski and Yochai Benkler –(Professor of Law at Yale; Professor of Law at Harvard) Law & Political Economy and the Question of Method

Jessica Silbey – (Boston University School of Law) Ethnography in Legal Scholarship

Roberto Tallarita – (Lecturer on Law, and Associate Director of the Program on Corporate Governance at Harvard) The Limits of Portfolio Primacy

Susan S. Silbey – (Leon and Anne Goldberg Professor of Humanities, Sociology and Anthropology at MIT) HELS with Susan Silbey: Analyzing Ethnographic Data and Producting New Theory

Cass R. Sunstein (University Professor at Harvard) – Optimal Sludge? The Price of Program Integrity

Scott L. Cummings (Professor of Legal Ethics and Professor of Law at UCLA School of Law) – The Making of Public Interest Lawyers

Elliot Ash (Assistant Professor of Law, Economics, and Data Science at ETH Zürich) – Gender Attitudes in the Judiciary: Evidence from U.S. Circuit Courts

Kathleen Thelen (Ford Professor of Political Science at MIT) – Employer Organization in the United States: Historical Legacies and the Long Shadow of the American Courts

Omer Kimhi (Associate Professor at Haifa University Law School) – Caught In a Circle of Debt – Consumer Bankruptcy Discharge and Its Aftereffects

Suresh Naidu (Professor in Economics and International and Public Affairs, Columbia School of International and Public Affairs) – Ideas Have Consequences: The Impact of Law and Economics on American Justice

Vardit Ravitsky (Full Professor at the Bioethics Program, School of Public Health, University of Montreal) – Empirical Bioethics: The Example of Research on Prenatal Testing

Johnnie Lotesta (Postdoctoral Democracy Fellow at the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at the Harvard Kennedy School) – Opinion Crafting and the Making of U.S. Labor Law in the States

David Hagmann (Harvard Kennedy School) – The Agent-Selection Dilemma in Distributive Bargaining

Cass R. Sunstein (Harvard Law School) – Rear Visibility and Some Problems for Economic Analysis (with Particular Reference to Experience Goods)

Talia Gillis (Ph.D. Candidate and S.J.D. Candidate, Harvard Business School and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and Harvard Law School) – False Dreams of Algorithmic Fairness: The Case of Credit Pricing

Tzachi Raz (Ph.D. Candidate in Economics at Harvard University) – There’s No Such Thing as Free Land: The Homestead Act and Economic Development

Crystal Yang (Harvard Law School) – Fear and the Safety Net: Evidence from Secure Communities

Adaner Usmani (Harvard Sociology) – The Origins of Mass Incarceration

Jim Greiner (Harvard Law School) – Randomized Control Trials in the Legal Profession

Talia Shiff (Postdoctoral Fellow, Weatherhead Center for International Affairs and Department of Sociology, Harvard University) – Legal Standards and Moral Worth in Frontline Decision-Making: Evaluations of Victimization in US Asylum Determinations

Francesca Gino (Harvard Business School) – Rebel Talent

Joscha Legewie (Department of Sociology, Harvard University) – The Effects of Policing on Educational Outcomes and Health of Minority Youth

Ryan D. Enos (Department of Government, Harvard University) – The Space Between Us: Social Geography and Politics

Katerina Linos (Berkeley Law, University of California) – How Technology Transforms Refugee Law

Roie Hauser (Visiting Researcher at the Program on Corporate Governance, Harvard Law School) – Term Length and the Role of Independent Directors in Acquisitions

Anina Schwarzenbach (Fellow, National Security Program, the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School) – A Challenge to Legitimacy: Effects of Stop-and-Search Police Contacts on Young People’s Relations with the Police

Cass R. Sunstein (Harvard Law School) – Willingness to Pay to Use Facebook, Twitter, Youtube, Instagram, Snapchat, and More: A National Survey

Netta Barak-Corren (Hebrew University of Jerusalem) – The War Within

James Greiner & Holger Spamann (Harvard Law School) – Panel: Why Does the Legal Profession Resist Rigorous Empiricism?

Mila Versteeg (University of Virginia School of Law) (with Adam Chilton) – Do Constitutional Rights Make a Difference?

Susan S. Silbey (MIT Department of Anthropology) (with Patricia Ewick) – The Common Place of Law

Holger Spamann (Harvard Law School) – Empirical Legal Studies: What They Are and How NOT to Do Them

Arevik Avedian (Harvard Law School) – How to Read an Empirical Paper in Law

James Greiner (Harvard Law School) – Randomized Experiments in the Law

Robert MacCoun (Stanford Law School) – Coping with Rapidly Changing Standards and Practices in the Empirical Sciences (including ELS)

Mario Small (Harvard Department of Sociology) – Qualitative Research in the Big Data Era