Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- April 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 4 CURRENT ISSUE pp.255-346

- March 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 3 pp.171-254

- February 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 2 pp.83-170

- January 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 1 pp.1-82

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Substance Use Disorders and Addiction: Mechanisms, Trends, and Treatment Implications

- Ned H. Kalin , M.D.

Search for more papers by this author

The numbers for substance use disorders are large, and we need to pay attention to them. Data from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health ( 1 ) suggest that, over the preceding year, 20.3 million people age 12 or older had substance use disorders, and 14.8 million of these cases were attributed to alcohol. When considering other substances, the report estimated that 4.4 million individuals had a marijuana use disorder and that 2 million people suffered from an opiate use disorder. It is well known that stress is associated with an increase in the use of alcohol and other substances, and this is particularly relevant today in relation to the chronic uncertainty and distress associated with the COVID-19 pandemic along with the traumatic effects of racism and social injustice. In part related to stress, substance use disorders are highly comorbid with other psychiatric illnesses: 9.2 million adults were estimated to have a 1-year prevalence of both a mental illness and at least one substance use disorder. Although they may not necessarily meet criteria for a substance use disorder, it is well known that psychiatric patients have increased usage of alcohol, cigarettes, and other illicit substances. As an example, the survey estimated that over the preceding month, 37.2% of individuals with serious mental illnesses were cigarette smokers, compared with 16.3% of individuals without mental illnesses. Substance use frequently accompanies suicide and suicide attempts, and substance use disorders are associated with a long-term increased risk of suicide.

Addiction is the key process that underlies substance use disorders, and research using animal models and humans has revealed important insights into the neural circuits and molecules that mediate addiction. More specifically, research has shed light onto mechanisms underlying the critical components of addiction and relapse: reinforcement and reward, tolerance, withdrawal, negative affect, craving, and stress sensitization. In addition, clinical research has been instrumental in developing an evidence base for the use of pharmacological agents in the treatment of substance use disorders, which, in combination with psychosocial approaches, can provide effective treatments. However, despite the existence of therapeutic tools, relapse is common, and substance use disorders remain grossly undertreated. For example, whether at an inpatient hospital treatment facility or at a drug or alcohol rehabilitation program, it was estimated that only 11% of individuals needing treatment for substance use received appropriate care in 2018. Additionally, it is worth emphasizing that current practice frequently does not effectively integrate dual diagnosis treatment approaches, which is important because psychiatric and substance use disorders are highly comorbid. The barriers to receiving treatment are numerous and directly interact with existing health care inequities. It is imperative that as a field we overcome the obstacles to treatment, including the lack of resources at the individual level, a dearth of trained providers and appropriate treatment facilities, racial biases, and the marked stigmatization that is focused on individuals with addictions.

This issue of the Journal is focused on understanding factors contributing to substance use disorders and their comorbidity with psychiatric disorders, the effects of prenatal alcohol use on preadolescents, and brain mechanisms that are associated with addiction and relapse. An important theme that emerges from this issue is the necessity for understanding maladaptive substance use and its treatment in relation to health care inequities. This highlights the imperative to focus resources and treatment efforts on underprivileged and marginalized populations. The centerpiece of this issue is an overview on addiction written by Dr. George Koob, the director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), and coauthors Drs. Patricia Powell (NIAAA deputy director) and Aaron White ( 2 ). This outstanding article will serve as a foundational knowledge base for those interested in understanding the complex factors that mediate drug addiction. Of particular interest to the practice of psychiatry is the emphasis on the negative affect state “hyperkatifeia” as a major driver of addictive behavior and relapse. This places the dysphoria and psychological distress that are associated with prolonged withdrawal at the heart of treatment and underscores the importance of treating not only maladaptive drug-related behaviors but also the prolonged dysphoria and negative affect associated with addiction. It also speaks to why it is crucial to concurrently treat psychiatric comorbidities that commonly accompany substance use disorders.

Insights Into Mechanisms Related to Cocaine Addiction Using a Novel Imaging Method for Dopamine Neurons

Cassidy et al. ( 3 ) introduce a relatively new imaging technique that allows for an estimation of dopamine integrity and function in the substantia nigra, the site of origin of dopamine neurons that project to the striatum. Capitalizing on the high levels of neuromelanin that are found in substantia nigra dopamine neurons and the interaction between neuromelanin and intracellular iron, this MRI technique, termed neuromelanin-sensitive MRI (NM-MRI), shows promise in studying the involvement of substantia nigra dopamine neurons in neurodegenerative diseases and psychiatric illnesses. The authors used this technique to assess dopamine function in active cocaine users with the aim of exploring the hypothesis that cocaine use disorder is associated with blunted presynaptic striatal dopamine function that would be reflected in decreased “integrity” of the substantia nigra dopamine system. Surprisingly, NM-MRI revealed evidence for increased dopamine in the substantia nigra of individuals using cocaine. The authors suggest that this finding, in conjunction with prior work suggesting a blunted dopamine response, points to the possibility that cocaine use is associated with an altered intracellular distribution of dopamine. Specifically, the idea is that dopamine is shifted from being concentrated in releasable, functional vesicles at the synapse to a nonreleasable cytosolic pool. In addition to providing an intriguing alternative hypothesis underlying the cocaine-related alterations observed in substantia nigra dopamine function, this article highlights an innovative imaging method that can be used in further investigations involving the role of substantia nigra dopamine systems in neuropsychiatric disorders. Dr. Charles Bradberry, chief of the Preclinical Pharmacology Section at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, contributes an editorial that further explains the use of NM-MRI and discusses the theoretical implications of these unexpected findings in relation to cocaine use ( 4 ).

Treatment Implications of Understanding Brain Function During Early Abstinence in Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder

Developing a better understanding of the neural processes that are associated with substance use disorders is critical for conceptualizing improved treatment approaches. Blaine et al. ( 5 ) present neuroimaging data collected during early abstinence in patients with alcohol use disorder and link these data to relapses occurring during treatment. Of note, the findings from this study dovetail with the neural circuit schema Koob et al. provide in this issue’s overview on addiction ( 2 ). The first study in the Blaine et al. article uses 44 patients and 43 control subjects to demonstrate that patients with alcohol use disorder have a blunted neural response to the presentation of stress- and alcohol-related cues. This blunting was observed mainly in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, a key prefrontal regulatory region, as well as in subcortical regions associated with reward processing, specifically the ventral striatum. Importantly, this finding was replicated in a second study in which 69 patients were studied in relation to their length of abstinence prior to treatment and treatment outcomes. The results demonstrated that individuals with the shortest abstinence times had greater alterations in neural responses to stress and alcohol cues. The authors also found that an individual’s length of abstinence prior to treatment, independent of the number of days of abstinence, was a predictor of relapse and that the magnitude of an individual’s neural alterations predicted the amount of heavy drinking occurring early in treatment. Although relapse is an all too common outcome in patients with substance use disorders, this study highlights an approach that has the potential to refine and develop new treatments that are based on addiction- and abstinence-related brain changes. In her thoughtful editorial, Dr. Edith Sullivan from Stanford University comments on the details of the study, the value of studying patients during early abstinence, and the implications of these findings for new treatment development ( 6 ).

Relatively Low Amounts of Alcohol Intake During Pregnancy Are Associated With Subtle Neurodevelopmental Effects in Preadolescent Offspring

Excessive substance use not only affects the user and their immediate family but also has transgenerational effects that can be mediated in utero. Lees et al. ( 7 ) present data suggesting that even the consumption of relatively low amounts of alcohol by expectant mothers can affect brain development, cognition, and emotion in their offspring. The researchers used data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study, a large national community-based study, which allowed them to assess brain structure and function as well as behavioral, cognitive, and psychological outcomes in 9,719 preadolescents. The mothers of 2,518 of the subjects in this study reported some alcohol use during pregnancy, albeit at relatively low levels (0 to 80 drinks throughout pregnancy). Interestingly, and opposite of that expected in relation to data from individuals with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, increases in brain volume and surface area were found in offspring of mothers who consumed the relatively low amounts of alcohol. Notably, any prenatal alcohol exposure was associated with small but significant increases in psychological problems that included increases in separation anxiety disorder and oppositional defiant disorder. Additionally, a dose-response effect was found for internalizing psychopathology, somatic complaints, and attentional deficits. While subtle, these findings point to neurodevelopmental alterations that may be mediated by even small amounts of prenatal alcohol consumption. Drs. Clare McCormack and Catherine Monk from Columbia University contribute an editorial that provides an in-depth assessment of these findings in relation to other studies, including those assessing severe deficits in individuals with fetal alcohol syndrome ( 8 ). McCormack and Monk emphasize that the behavioral and psychological effects reported in the Lees et al. article would not be clinically meaningful. However, it is feasible that the influences of these low amounts of alcohol could interact with other predisposing factors that might lead to more substantial negative outcomes.

Increased Comorbidity Between Substance Use and Psychiatric Disorders in Sexual Identity Minorities

There is no question that victims of societal marginalization experience disproportionate adversity and stress. Evans-Polce et al. ( 9 ) focus on this concern in relation to individuals who identify as sexual minorities by comparing their incidence of comorbid substance use and psychiatric disorders with that of individuals who identify as heterosexual. By using 2012−2013 data from 36,309 participants in the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III, the authors examine the incidence of comorbid alcohol and tobacco use disorders with anxiety, mood disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The findings demonstrate increased incidences of substance use and psychiatric disorders in individuals who identified as bisexual or as gay or lesbian compared with those who identified as heterosexual. For example, a fourfold increase in the prevalence of PTSD was found in bisexual individuals compared with heterosexual individuals. In addition, the authors found an increased prevalence of substance use and psychiatric comorbidities in individuals who identified as bisexual and as gay or lesbian compared with individuals who identified as heterosexual. This was most prominent in women who identified as bisexual. For example, of the bisexual women who had an alcohol use disorder, 60.5% also had a psychiatric comorbidity, compared with 44.6% of heterosexual women. Additionally, the amount of reported sexual orientation discrimination and number of lifetime stressful events were associated with a greater likelihood of having comorbid substance use and psychiatric disorders. These findings are important but not surprising, as sexual minority individuals have a history of increased early-life trauma and throughout their lives may experience the painful and unwarranted consequences of bias and denigration. Nonetheless, these findings underscore the strong negative societal impacts experienced by minority groups and should sensitize providers to the additional needs of these individuals.

Trends in Nicotine Use and Dependence From 2001–2002 to 2012–2013

Although considerable efforts over earlier years have curbed the use of tobacco and nicotine, the use of these substances continues to be a significant public health problem. As noted above, individuals with psychiatric disorders are particularly vulnerable. Grant et al. ( 10 ) use data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions collected from a very large cohort to characterize trends in nicotine use and dependence over time. Results from their analysis support the so-called hardening hypothesis, which posits that although intervention-related reductions in nicotine use may have occurred over time, the impact of these interventions is less potent in individuals with more severe addictive behavior (i.e., nicotine dependence). When adjusted for sociodemographic factors, the results demonstrated a small but significant increase in nicotine use from 2001–2002 to 2012–2013. However, a much greater increase in nicotine dependence (46.1% to 52%) was observed over this time frame in individuals who had used nicotine during the preceding 12 months. The increases in nicotine use and dependence were associated with factors related to socioeconomic status, such as lower income and lower educational attainment. The authors interpret these findings as evidence for the hardening hypothesis, suggesting that despite the impression that nicotine use has plateaued, there is a growing number of highly dependent nicotine users who would benefit from nicotine dependence intervention programs. Dr. Kathleen Brady, from the Medical University of South Carolina, provides an editorial ( 11 ) that reviews the consequences of tobacco use and the history of the public measures that were initially taken to combat its use. Importantly, her editorial emphasizes the need to address health care inequity issues that affect individuals of lower socioeconomic status by devoting resources to develop and deploy effective smoking cessation interventions for at-risk and underresourced populations.

Conclusions

Maladaptive substance use and substance use disorders are highly prevalent and are among the most significant public health problems. Substance use is commonly comorbid with psychiatric disorders, and treatment efforts need to concurrently address both. The papers in this issue highlight new findings that are directly relevant to understanding, treating, and developing policies to better serve those afflicted with addictions. While treatments exist, the need for more effective treatments is clear, especially those focused on decreasing relapse rates. The negative affective state, hyperkatifeia, that accompanies longer-term abstinence is an important treatment target that should be emphasized in current practice as well as in new treatment development. In addition to developing a better understanding of the neurobiology of addictions and abstinence, it is necessary to ensure that there is equitable access to currently available treatments and treatment programs. Additional resources must be allocated to this cause. This depends on the recognition that health care inequities and societal barriers are major contributors to the continued high prevalence of substance use disorders, the individual suffering they inflict, and the huge toll that they incur at a societal level.

Disclosures of Editors’ financial relationships appear in the April 2020 issue of the Journal .

1 US Department of Health and Human Services: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality: National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2018. Rockville, Md, SAMHSA, 2019 ( https://www.samhsa.gov/data/nsduh/reports-detailed-tables-2018-NSDUH ) Google Scholar

2 Koob GF, Powell P, White A : Addiction as a coping response: hyperkatifeia, deaths of despair, and COVID-19 . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1031–1037 Link , Google Scholar

3 Cassidy CM, Carpenter KM, Konova AB, et al. : Evidence for dopamine abnormalities in the substantia nigra in cocaine addiction revealed by neuromelanin-sensitive MRI . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1038–1047 Link , Google Scholar

4 Bradberry CW : Neuromelanin MRI: dark substance shines a light on dopamine dysfunction and cocaine use (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1019–1021 Abstract , Google Scholar

5 Blaine SK, Wemm S, Fogelman N, et al. : Association of prefrontal-striatal functional pathology with alcohol abstinence days at treatment initiation and heavy drinking after treatment initiation . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1048–1059 Link , Google Scholar

6 Sullivan EV : Why timing matters in alcohol use disorder recovery (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1022–1024 Abstract , Google Scholar

7 Lees B, Mewton L, Jacobus J, et al. : Association of prenatal alcohol exposure with psychological, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental outcomes in children from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1060–1072 Link , Google Scholar

8 McCormack C, Monk C : Considering prenatal alcohol exposure in a developmental origins of health and disease framework (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1025–1028 Abstract , Google Scholar

9 Evans-Polce RJ, Kcomt L, Veliz PT, et al. : Alcohol, tobacco, and comorbid psychiatric disorders and associations with sexual identity and stress-related correlates . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1073–1081 Abstract , Google Scholar

10 Grant BF, Shmulewitz D, Compton WM : Nicotine use and DSM-IV nicotine dependence in the United States, 2001–2002 and 2012–2013 . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1082–1090 Link , Google Scholar

11 Brady KT : Social determinants of health and smoking cessation: a challenge (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1029–1030 Abstract , Google Scholar

- Cited by None

- Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders

- Addiction Psychiatry

- Transgender (LGBT) Issues

- Open access

- Published: 21 June 2021

A review of research-supported group treatments for drug use disorders

- Gabriela López 1 ,

- Lindsay M. Orchowski ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9048-3576 2 ,

- Madhavi K. Reddy 3 ,

- Jessica Nargiso 4 &

- Jennifer E. Johnson 5

Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy volume 16 , Article number: 51 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

27k Accesses

7 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

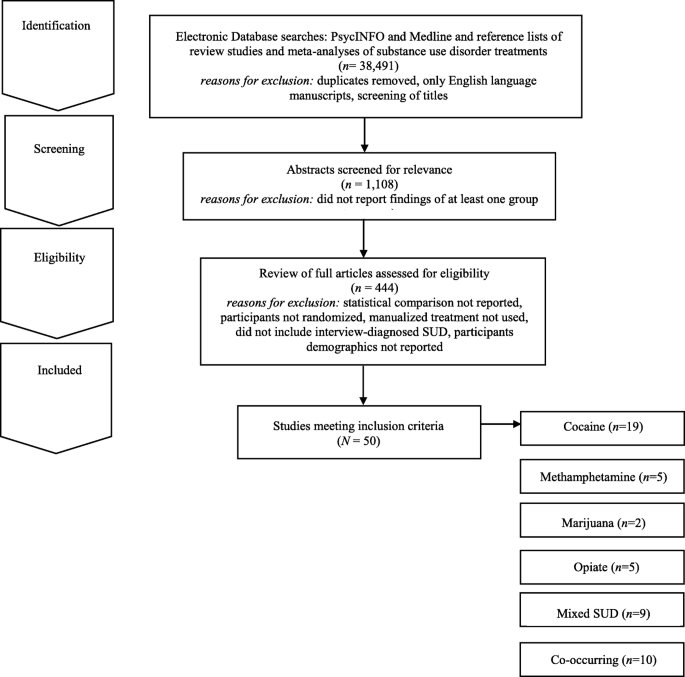

This paper reviews methodologically rigorous studies examining group treatments for interview-diagnosed drug use disorders. A total of 50 studies reporting on the efficacy of group drug use disorder treatments for adults met inclusion criteria. Studies examining group treatment for cocaine, methamphetamine, marijuana, opioid, mixed substance, and substance use disorder with co-occurring psychiatric conditions are discussed. The current review showed that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) group therapy and contingency management (CM) groups appear to be more effective at reducing cocaine use than treatment as usual (TAU) groups. CM also appeared to be effective at reducing methamphetamine use relative to standard group treatment. Relapse prevention support groups, motivational interviewing, and social support groups were all effective at reducing marijuana use relative to a delayed treatment control. Group therapy or group CBT plus pharmacotherapy are more effective at decreasing opioid use than pharmacotherapy alone. An HIV harm reduction program has also been shown to be effective for reducing illicit opioid use. Effective treatments for mixed substance use disorder include group CBT, CM, and women’s recovery group. Behavioral skills group, group behavioral therapy plus CM, Seeking Safety, Dialectical behavior therapy groups, and CM were more effective at decreasing substance use and psychiatric symptoms relative to TAU, but group psychoeducation and group CBT were not. Given how often group formats are utilized to treat drug use disorders, the present review underscores the need to understand the extent to which evidence-based group therapies for drug use disorders are applied in treatment settings.

Drug use disorders are a significant public health concern in the United States. According to the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions-III, the lifetime prevalence rate of DSM-5 drug use disorders is 9.9%, which includes amphetamine, cannabis, club drug, cocaine, hallucinogen, heroin, opioid, sedative/tranquilizer, and solvent/inhalant use disorders [ 1 ]. Drug use disorders are defined in terms of eleven criteria including physiological, behavioral and cognitive symptoms, as well as consequences of criteria, any two of which qualify for a diagnosis [ 2 , 3 ]. The individual and community costs of drug use are estimated at over $193 billion [ 4 , 5 ] and approximately $78.5 billion [ 6 ] for opioids alone. Consequences include overdose [ 7 ], mental health problems [ 8 ], and a range of medical consequences such as human immunodeficiency virus [ 9 , 10 ], hepatitis C virus [ 9 ], and other viral and bacterial infections [ 11 ].

Evidence-based practice was formally defined by Sackett et al. [ 12 ] in 1996 to refer to the “conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients” (p. 71). In 2006, the American Psychological Association [ 13 ] developed a policy on evidence-based practice (EBP) of psychotherapy, which emphasized the integration of best research evidence (i.e., data from meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, effectiveness trials, and other forms of systematic case studies and reviews) with clinical expertise and judgment to deliver treatment in the context of a patient’s individual needs, preferences and culture. The shift towards EBP for substance use disorders has multiple benefits for practitioners and patients, including an increased focus on the implementation of treatments that are safe and cost-effective [ 14 ]. A recent survey of clinicians’ practices with substance use treatment found that clinicians often conducted therapy in groups [ 15 ]. While most clinicians who completed the survey reported use of evidence-based treatment practices (EBT) some also reported the use of non-EBT practices [ 15 ]. Ensuring that clinicians can readily access information regarding the current state of evidence regarding group-based therapies for substance use disorders is critical for fostering increased use of EBTs.

Although any effort to summarize a literature as large and complex as the psychological treatment literature is useful, there are several limitations. With few exceptions, research-supported treatment lists categorize treatments by formal change theory (e.g., cognitive-behavioral, interpersonal) and describe little about the context, format, or setting in which treatments were conducted and tested [ 16 ]. As a result, it is often difficult to ascertain from existing resources whether research supported treatments were conducted in group or individual format. A group format is often used in substance use treatment [ 17 ] and aftercare programs [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ] . The discrepancy between the wide-spread use of group therapy in clinical practice and the relative paucity of research on the efficacy of group treatments has been noted by treatment researchers [ 23 ] and clinicians [ 24 ]. According to Lundahl’s [ 25 ] 2010 meta-analysis of studies evaluating the efficacy of motivational interviewing (MI), a commonly used treatment for substance use disorders, examination of the 119 studies concluded that studies of MI in a group format were too rare to draw solid conclusions about the efficacy of group MI. Also, it is possible that efficacy of treatments developed for individual delivery will be altered when delivered in a group format and vice versa. Given the limited empirical inquiry on group treatments for substance use, a framework organizing the literature on the efficacy of group therapy to treat substance use disorders would be useful. There is also a need for a more recent rigorous review of the empirical evidence to support group-based treatments for substance use disorders. Over 15 years ago, Weiss and colleagues conducted a review of 24 treatment outcome studies within the substance use disorder intervention literature comparing group therapy to other treatments conditions (i.e., no group therapy, individual therapy, group therapy plus individual therapy), and found no differences between group and individual therapy [ 26 ].

Given the importance of understanding the current evidence base for group-delivered treatments for substance use disorders, the present review sought to provide a summary of the literature on the benefits of group treatments for drug use disorders. Group treatments are potentially cost-effective, widely disseminable, and adaptable to a variety of populations but are lagging individual treatments in terms of research attention. Thus, highlighting characteristics of group treatments that are potentially efficacious is of import to stimulate further empirical inquiry. The review is organized by drug type (cocaine, methamphetamine, marijuana, opiate, mixed substance use disorders; SUD) and co-occurring SUD and psychiatric problems. We excluded studies focused on alcohol use disorder alone as this literature is summarized elsewhere (see Orchowski & Johnson, 2012). Given research suggesting that several factors impact outcomes of group treatments, including formal change theory driving the treatment approach (i.e., cognitive-behavioral, motivational interviewing), as well as patient factors [ 27 ], the review begins by first reviewing each theory of change (i.e., type of treatment), and then concludes by summarizing the research examining the extent to which patient factors influence the efficacy of group treatments for SUD.

To locate studies that evaluated a group treatment for SUD that met review inclusion criteria, the authors conducted a comprehensive literature search of PsycINFO and MedLine through 2020. Three individuals then examined abstracts of the articles for relevance. In addition, the authors utilized the reference lists of review studies and meta-analyses of SUD- treatments to locate additional studies that might meet the review inclusion criteria. The authors and a research assistant then reviewed full articles with relevance to the current study and excluded any studies that did not meet the review inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1 ).

Electronic Search Strategy Flowchart

For inclusion in the review, studies needed to meet the following criteria: 1) report the findings of at least one group treatment; 2) provide at least one statistical comparison between the group treatment and a control condition; 3) randomize participants between the group treatment and control condition; 4) utilize a manualized treatment; 5) include patients with an interview-diagnosed SUD; and 6) provide information regarding the demographic characteristics of the participants in the study. Studies’ methods and results were used for data extraction. Studies which maintained a primary focus on the treatment of SUD, but also included treatment of a co-occurring psychiatric condition, were included in the review. Studies which included alcohol use as a comorbid diagnosis along another substance use were included. Studies examining the efficacy of group treatment for only alcohol use were excluded. The final set of articles included were 50 research studies that utilized a group treatment modality for the treatment of SUD, including separately examining cocaine, methamphetamine, marijuana, opioid, mixed substance, or SUD with comorbid psychiatric problems in adults.

It should be noted that several studies that met inclusion criteria were not reported in the present review because they did not report the use of a specific screening instrument for SUD as a part of the study inclusion/exclusion criteria. These studies are as follows and include these comparisons: group-based relational therapy [ 28 ] two studies by Guydish et al. [ 29 , 30 ] comparing a day treatment program to residential treatment (RT) program, a day treatment program to a coping skills group [ 31 ], standard care to a harm reduction group [ 32 ], 12 step group to a CBT group [ 33 ], medical management treatment (MMT) with CBT group to an MMT plus treatment reinforcement plan [ 34 ], treatment as usual to contingency management (CM) [ 35 ], professionally led recovery training group to treatment as usual (TAU) [ 36 ], two 4 month residential treatment programs [ 37 ], varying lengths of therapeutic community program (TPC) with and without relapse prevention [ 38 ], and Information and Referral plus peer advocacy to a Motivational group with CBT group [ 39 ].

Review of evidence-based theories of change

The 50 research studies meeting inclusion criteria tested the following group treatment modalities: contingency management (CM), motivational interviewing (MI), relapse prevention (RP), social support (SS), cognitive-behavioral (CBT), coping skills (CS), harm reduction (HR), cognitive therapy (CT), drug counseling (DC), recovery training (RT), standard group therapy (SGT), family therapy (FT), intensive group therapy (IGT), 12 step facilitation group therapy (12SG), relational psychotherapy mothers’ group (RPMG), psychoeducational therapy group (PET), behavioral skills (BS), and seeking safety (SS). Below, we briefly review the theory of change that drives each of these treatments.

Several treatment approaches are grounded in behavioral therapies and/or cognitive therapies. Broadly, cognitive therapy is an approach that focuses exclusively on targeting thoughts that are identified as part of a diagnosis or behavioral problem [ 28 ]. Cognitive-behavioral (CBT) therapy is an approach that targets specific symptoms, thoughts, and behaviors that are identified as part of a diagnosis or presenting problem [ 28 ]. Under the umbrella of CBT several other treatment modalities exist. For example, relapse prevention is a CBT treatment that hypothesizes that there are cognitive, behavioral, and affective mechanism that underlie the process of relapse [ 40 ]. Recovery training is a more specific form of relapse prevention, including education on addiction and recovery and reinforcing relapse prevention skills (e.g., understanding triggers, coping with cravings etc.) [ 41 , 42 ]. Other treatments focus on coping skills more broadly. For example, coping skills treatments include a focus on components of adaptability in interpersonal relationships, thinking and feeling, as well as approaches to self and life [ 28 ]. Some treatment approaches also recognize that individuals may not be ready to change their substance use. For example, motivational interviewing is often described as a therapy guiding technique in which the therapist is a helper in the behavior change process and expressed acceptance of the patient [ 43 ]. Standard group therapy includes 90 min sessions approximately twice a week in a group setting, [ 44 ] whereas intensive group therapy is a heavier dose of standard group therapy that includes 120-min sessions up to five times a week [ 44 ]. Psychoeducational therapy group focused on providing information on the immediate and delayed problems of substance use disorders to patients [ 45 ]. Lastly, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is a type of CBT therapy that focuses on helping regulate intense emotional states and provides skills to reduce arousal levels, and increase mindfulness, emotional regulation, and interpersonal skills [ 46 ].

Grounded within behavioral therapies, are behavioral skills training which focused on developing behaviors that are adaptive [ 28 ]. Contingency management is a type of behavioral therapy in which patients are reinforced or rewarded for positive behavioral change [ 47 ]. Harm reduction is a term for interventions aiming to reduce the problematic effects of behaviors [ 48 ]. Several treatment approaches also focus on interpersonal networks and building interpersonal skills. For example, social support is any psychological resources provided by a social network to help patients cope with stress [ 49 ]. Twelve-step facilitation group therapy is a more specific form of social support, which focuses on introducing patients to the 12 steps of alcoholics anonymous or related groups (i.e., cocaine or narcotics anonymous) to encourage 12-step meeting attendance in their community [ 33 , 50 ]. Seeking Safety is a present-focused and empowerment-based intervention focused on coping skills that emphasizes the importance of safety within interpersonal relationships [ 51 ]. Drug counseling describes treatment that aims to facilitate abstinence, encourage mutual support, and provide coping skills [ 52 ]. Finally, family therapy is a family-based intervention that aims to change, parenting behaviors and family interactions [ 53 ]. Overall, there are many overlapping components and skill sets in the models discussed above (See Table 1 ).

Group-based cocaine use treatments for adults

Nineteen studies were identified that targeted cocaine use and utilized some form of group therapy, the most of any drug in this review (see Table 2 ). Overall, the studies showed that all of the group therapy modalities included in this review generally reduced cocaine use when compared to treatment as usual (TAU), including day hospital groups [ 54 ]. Two studies, Magura et al. (1994) and Magura et al. (2002) did not find group differences between 8 months CBT and 8 months of TAU that consisted of methadone maintenance therapy among 141 patients with cocaine disorder [ 60 , 69 ]. When compared directly, individuals in CBT groups achieved longer abstinence than individuals in 12 step facilitation groups [ 33 ] or low intensity groups [ 64 , 65 ]. However, in another study, individuals with cocaine dependence receiving 12-step based Group Drug Counseling (GDC; similar to 12-step facilitation) had similar cocaine abstinence outcomes with or without additional individual CBT [ 41 ]. This may suggest that group 12-step facilitation is an effective intervention for cocaine dependence. Two studies demonstrated the superiority of CM groups for reducing cocaine use as compared to CBT [ 62 ] or TAU groups [ 61 , 62 ] at 12 weeks [ 54 ], 17 weeks [ 53 ], 26 weeks [ 53 ] and 52 weeks follow up [ 51 ]. Therefore, CBT group therapy and contingency management groups appear to be more effective at reducing cocaine use than TAU groups.

Group-based methamphetamine use treatments for adults

Only five treatment studies were identified that examined group treatments for methamphetamine use (see Table 3 ). Three studies found longer periods of abstinence for the group treatment (CM or drug+CM) than for TAU or non-CM conditions. The first study conducted by Rawson and colleagues compared matrix model (MM) with TAU in eight community outpatient settings [ 71 ]. The MM consisted of CBT groups, family education groups, social support groups, and individual counseling sessions along with weekly urine screens for 16 weeks. Participants in the MM condition attended more sessions, stayed in treatment longer, had more than twice as many contacts, evidence longer abstinence and greater self-reported psychosocial functioning relative to the TAU group. However, these significant differences did not persist 6 months later at follow-up.

Shoptaw et al. (2006) [ 73 ] compared four groups for treating methamphetamine dependence sertraline + CM, sertraline only, placebo + CM, and placebo [ 73 ]. Additionally, all participants attended a relapse prevention group conducted three times a week over a 14-week period. Findings provided support for the efficacy of CM for amphetamine use disorders. Group treatment (CM or drug + CM) was more effective for sustaining longer periods of abstinence relative to TAU or non-CM conditions. Roll et al. [ 72 ] found that effects of CM relative to TAU became larger as the duration of CM increased. Jaffe et al. [ 70 ] evaluated a culturally tailored intervention for 145 methamphetamine dependent gay and bisexual males. Participants in the Gay Specific CBT condition reported the most rapid decline in levels of methamphetamine use relative to standard CBT, CBT + CM, suggesting benefits for culturally appropriate group methamphetamine interventions.

Group-based marijuana use treatments for adults

Two studies examining group treatments for adults with marijuana use disorders were identified (see Table 4 ). Both studies were conducted by the same research group, utilizing the same inclusion criteria for marijuana use (50 times in 90 days). The studies examined group relapse prevention (RP) [ 76 ], specifically designed for adult marijuana users. The first trial [ 75 ] ( n = 212) comparing relapse prevention to a social support group found participants in both group treatment conditions did well overall, with two-thirds (65%) reporting abstinence of marijuana use for 2 weeks after session 4 or the quit date and 63% reporting abstinence during the last 2 weeks of treatment. Gender differences emerged; no differences between group treatments were found for women, but men in the relapse prevention group reported reduced marijuana use at the 3-month follow-up compared to men in the social support group.

A second trial [ 74 ] randomized participants to 14 sessions of group RP enhanced with cognitive behavioral skills training, two sessions of motivational interviewing (MI) with feedback and advice on cognitive behavioral skills (modeled after the Drinkers Check-up) [ 77 ], or a 4-month delayed treatment control (DTC) group which consisted of the RP group or individual MI treatment of the participants choosing. Compared to individuals randomly assigned to the DTC condition, participants in the group RP and individual MI conditions evidenced a significantly greater reduction in marijuana use and related problems over 16-month follow-up. However, examination of participants’ reactions to DTC assignment indicated that participants who felt that changing their marijuana use was their own responsibility were more likely than those who did not to change their use patterns without treatment engagement.

Group-based opiate use treatments for adults

Five group treatment studies for opioid use were identified (see Table 5 ). Two studies compared the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy plus group therapies [ 79 , 80 , 81 ] to pharmacotherapy alone in samples of opioid dependent persons, and both found that adding group treatment improved outcomes. The first study compared Naltrexone with monthly medical monitoring visits to an enhanced group condition (EN) consisting of Naltrexone plus a Matrix Method (MM) [ 79 ]. MM consisted of hourly individual sessions, 90-min CBT group, and 60 min of cue-exposure weekly for weeks 1–12; hourly individual sessions and CBT group sessions for weeks 13–26; and 90-min social support group sessions for weeks 27–52. Results found that EN participants took more study medication, were retained in treatment longer, used less opioids while in treatment, and showed greater improvement on psychological and affective dimensions than Naltrexone only participants. No difference by treatment condition was found at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. Similarly, Scherbaum et al. [ 80 ] compared routine Methadone Maintenance Therapy (MMT) with routine MMT plus group CBT psychotherapy (20 90-min sessions for 20 weeks). MMT plus group CBT participants showed less drug use than participants in the MMT group (i.e., control group). In contrast, a higher dose of group therapy provided without methadone maintenance was less effective for heroin use than was a lower dose of group therapy with methadone maintenance (Sees et al. [ 81 ]. This suggests that the combination of pharmacotherapy and group therapy for opioid use is optimal.

Shaffer et al. [ 22 ] compared psychodynamic group therapy with a hatha yoga group. All participants received methadone maintenance and individual therapy. No differences between two treatment conditions were found. For all participants, longer participation in treatment was associated with reduction in drug use and criminal activity. Lastly, Des Jarlais et al. [ 78 ] compared a group social learning AIDS/drug injection treatment program (4 sessions, 60–90 min, over 2 weeks) to a control condition. All participants received information about AIDS and HIV antibody test counseling. Compared to control participants, intervention participants reported lower rates of drug injection over time.

Group treatments for mixed SUD for adults

Nine treatment studies were identified that targeted mixed substance use with group treatments (see Table 6 ). Three involved CBT. Downey et al. [ 82 ] compared group CBT plus individual CBT to group CBT plus vouchers in a sample of 14 polysubstance users (cocaine and heroin) maintained on buprenorphine. The study was significantly underpowered and they found no significant differences on treatment outcomes. Marques and Formiogioni [ 84 ] compared individual CBT to group CBT in a sample of 155 participants with alcohol and/or drug dependence. They found that both formats resulted in similar outcomes, with higher compliance in the group CBT participants (66.7% compliance with treatment). Rawson et al. [ 87 ] compared three 16-week treatments: CM, group CBT, and CM plus group CBT, among 171 participants with cocaine disorder or methamphetamine abuse. They found that CM produced better retention and lower rates of stimulant use than CBT during treatment, but CBT produced comparable longer-term outcomes.

Two studies involved Group Drug Counseling (GDC). Greenfield et al. [ 52 ] compared a group drug counseling (GDC) (mixed gender) to a women’s recovery group (WRG) that both met weekly, for 12 weeks, for 90-min sessions among 44 participants that had a substance use disorder other than nicotine. WRG evidenced significantly greater reductions in drug and alcohol use over the follow up compared with GDC. Schottenfeld et al. [ 88 ] compared GDC (weekly, 1-h group sessions) to a community reinforcement approach (CRA; twice weekly sessions for the first 12 weeks and then weekly the following 12 weeks) among 117 patients with an opioid and cocaine use disorder. There were no differences in retention or drug use.

Remaining studies examined other interventions. Margolin et al. [ 83 ] compared an HIV Harm reduction program (HHRP) that met twice weekly for 2 h to an active control group that met six times in a sample of 90 HIV-seropositive methadone-maintained injection drug users with opioid dependence, and abuse or dependence on cocaine. At follow up, they had lower addiction severity scores and were less likely to have engaged in high risk behaviors compared to control. McKay et al. [ 85 ] compared weekly phone monitoring and counseling plus a support group in the first 4 weeks (TEL), twice-weekly individualized relapse prevention, and twice-weekly standard group counseling (STND) among 259 referred participants with alcohol use disorder or cocaine disorder. STND resulted in more days abstinent than TEL. Nemes et al. [ 86 ] compared a 12-month group program (10 months inpatient and 2 months outpatient) to an abbreviated group program (6 months inpatient, 6 months outpatient) among 412 patients with multiple drug/alcohol use disorders. Results indicated that both groups had reduction in arrests and drug use. There were no significant difference between groups. Lastly, Smith et al. [ 89 ] compared a standard treatment program (STP, daily group counseling, family outreach, 12-step program introduction, four 2 h sessions for family) to an enhanced treatment program (ETP; twice weekly group on relapse prevention and interpersonal violence in additional to all STP components) among 383 inpatient veterans meeting for an alcohol, cocaine, or amphetamine use disorder. Results indicated that ETP had enhanced abstinence rates at 3-month and 12-month follow up compared to STP, regardless of type of drug use.

Group Treatments for SUD and Co-Occurring Psychiatric Problems

Individuals with psychiatric distress are at high risk for comorbid SUD [ 90 ]. Ten randomized controlled studies meeting our inclusion criteria examined the efficacy of group therapy for SUD and co-occurring psychiatric problems (see Table 7 ). Three studies described group treatment of SUD and co-occurring DSM-IV Axis II disorders [ 18 , 91 , 96 ], three studies examined group treatment of drug abuse and co-occurring DSM-IV classified Axis I disorders [ 92 , 93 , 99 ], one study explored group drug abuse treatment and co-occurring psychiatric problems among homeless individuals without limiting to DSM-IV Axis I or Axis II diagnoses [ 97 ], and one study focused on group drug treatment among individuals testing positive for HIV [ 98 ]. Within this diverse set of RCTs, participants generally included individuals diagnosed with any form of SUD; however, some studies focused specifically on individuals using cocaine [ 91 , 97 ] or cocaine/opioids [ 98 ].

A range of group treatment approaches are represented, including group psychoeducational therapy, group CBT approaches, group DBT, Seeking Safety and CM. DiNitto and colleagues [ 92 ] evaluated the efficacy of adding a group-based psychoeducational program entitled “Good Chemistry Groups” to standard inpatient SUD treatment services among 97 individuals with a dual diagnosis of SUD and a DSM-IV Axis I psychological disorder. The nine 60-min Good Chemistry Group sessions were offered 3 times per week for 3 weeks. When compared to standard inpatient treatment, the addition of the psychoeducational group was not associated with any changes in medical, legal, alcohol, drug, psychiatric or family/social problems among participants.

The efficacy of adding a psychoeducational group treatment to standard individual therapy to address HIV risk among cocaine users has also been examined [ 91 ]. Participants were randomly assigned to complete the following: 1) individually-administered Standard Intervention developed by the NIDA Cooperative Agreement Final Cohort sites [ 100 ] including HIV testing, and pre- and post-HIV testing counseling on risks relating to cocaine use, transmission of STDs/HIV, condom use, cleaning injection equipment, and the benefits of treatment; or) Standard Intervention plus four 2-h peer-delivered psychoeducational groups addressing stress management, drug awareness, risk reduction strategies, HIV education and AIDS. Among the sample of 966 individuals completing the 3-month follow-up, the group psychoeducational treatment was not differentially effective in reducing drug use and HIV risk behavior in comparison to standard treatment alone at 3-months post-baseline, regardless of treatment type, individuals with antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) demonstrated less improvement in crack cocaine use compared to individuals without ASPD or depression.

The following types of group CBT have sustained research evaluation meeting our inclusion criteria to address co-occurring SUD and Axis I or Axis II disorders: 1) group behavioral skills training; 2) group cognitive behavioral therapy; 3) group-based Seeking Safety [ 51 ], and 4) group dialectical behavioral therapy. Specifically, Jerrell and Ridgely [ 93 ] examined the efficacy of group behavioral skills (BS) training, group-based 12-step facilitation (TS) treatment, and intensive case management among 132 individuals with a dual diagnosis of SUD and another Axis I psychiatric problem over the course of 24-months. Based on the Social and Independent Living Skills program [ 101 ], the BS group included one group per week addressing self-management skills designed to enhance abstinence, including medication management, relapse prevention, social skills, leisure activities and symptom monitoring. Relative to participants in TS groups, participants in the BS groups evidenced increased psychosocial functioning and decreased psychiatric symptoms (i.e., schizophrenia, depressive symptoms, mania, drug use and alcohol use) across the 6-, 12- and 18-month follow-up assessments after treatment entry.

Lehman and colleagues’ [ 95 ] examination of the efficacy of group CBT for substance abuse compared to TAU among 54 individuals with SUD and either schizophrenia or a major affective disorder revealed no differences between treatment groups over the course of a 1-year follow-up period. More promising findings were reported in Fisher and Bentley’s [ 18 ] evaluation of a group CBT and group therapy based in the disease and recovery model (DRM) among 38 individuals with dual diagnosis of SUD and a personality disorder. Groups met three times per week for 12 weeks and were compared to TAU. Individuals in group CBT and group DRM indicated improved social and family functioning compared to TAU, and among those who completed the group in an outpatient setting, CBT was more effective in reducing alcohol use, enhancing psychological functioning and improving social and family functioning compared to DRM and TAU.

Group behavioral therapy plus abstinence contingent housing and work administered in the context of a day treatment program was compared to behavioral group treatment alone among individuals with cocaine abuse/dependence, non-psychotic psychiatric conditions, and homelessness [ 97 , 102 ]. The group behavioral therapy included 8 weeks of daily treatment (4 h and 50 min per day) of groups addressing relapse prevention training, assertiveness training, AIDS education, 12-step facilitation, relaxation, recreation development, goal setting, and goal planning. Participants also engaged in a process-oriented group as well as individual counseling and urine monitoring and engaged in a weekly 90 min psychoeducational group therapy during months 3–6 following treatment enrollment. Individuals who received contingency-based work and housing were provided with rent-free housing and employment in construction or food service industries after 2 consecutive weeks of abstinence [ 103 ]. Relative to BS groups alone, group behavioral day treatment plus contingency management was associated with greater abstinence at 2- and 6-month follow-ups [ 102 ] and were less likely to relapse [ 97 ], although gains were not maintained at 12-months [ 104 ]. Both groups evidenced positive changes in drug use overtime compared to baseline [ 104 ].

Zlotnick, Johnston and Najavits [ 99 ] evaluated the efficacy of Seeking Safety (SS), in comparison to treatment as usual (TAU) among 49 incarcerated women with substance use disorder (SUD) and full or subthreshold posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). SS aims to decrease PTSD and SUD through psychoeducational and present-focused and empowerment-based instruction on coping skills that emphasize abstinence and safety [ 51 ]. The SS group treatment included 90-min group sessions held three times per week, that were completed in addition to the 180 to 240 h of group and individual therapy provided in TAU. All participants showed similar improvement on assessments of PSTD, SUD, legal problems and other psychiatric concerns at 12-week, 3- and 6-month follow-ups following prison release. Nonetheless, there was a trend for improved PTSD and continued improvements in psychiatric symptoms at follow-up among participants completing SS compared to TAU. Greater completion of SS sessions was associated with increased improvement in PTSD as well as drug use among women [ 99 ].

Dialectical behavioral group therapy (DBT), a CBT-focused treatment for individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD), has also been evaluated in comparison to TAU among individuals with BPD and co-occurring SUD [ 96 ]. Core elements of DBT are manualized [ 105 ], and have been evaluated in prior research [ 106 , 107 , 108 ]. Techniques center on providing the participant with acceptance and validation while maintaining a continual focus on behavior change, and include the following: mindfulness skills training, behavioral analysis of dysfunctional behavior, cognitive restructuring, coping skills training, exposure-based strategies addressing maladaptive emotions, and behavioral management skills training. DBT was administered through 2 ¼ hour weekly group sessions administered in combination with 60 min of weekly individual therapy and the opportunity for skills-coaching phone calls. Relative to TAU, participants randomly assigned to DBT demonstrated greater reductions in drug use during the 12-month treatment and at the 16-month follow-up assessment, as well as greater gains in adjustment at the 16-month follow-up assessment.

Although contingency management is commonly administered individually, Petry and colleagues [ 98 ] examined the efficacy of weekly 60-min group-based contingency management (CM) for reinforcing health behaviors and HIV-positive individuals with cocaine or opioid disorders ( N = 170) in comparison to 12-step facilitation (TS) over the course of a 24-week period. Overall, participants in CM were more likely than those in TS to submit consecutive drug-free urine specimens, although the overall proportion of drug-free specimens did not vary between groups during treatment or over the follow-up period. Notably, during treatment, group CM was associated with greater reductions in HIV-risk behaviors as well as overall viral load compared to TS; although effects were not maintained over the follow-up period.

Across these studies, many trials showed positive gains for both group treatments examined [ 18 , 97 , 98 ], or no difference between groups when examining the benefit of adding group treatment to existing TAU [ 91 , 92 , 95 , 99 ]. However, one study demonstrated greater reductions in drug use among individuals with BPD and SUD who completed group DBT in comparison to TAU [ 96 ]. Further, BS groups were more effective than TS groups in improving psychosocial functioning and decreasing substance use [ 93 ]. Finally, CBT was more effective than DRM in reducing alcohol use, enhancing psychological functioning and improving social and family functioning compared to DRM and TAU among individuals dually diagnosed with SUD and a personality disorder [ 18 ].

Factors associated with treatment efficacy

Gender and treatment efficacy.

Five of the studies included in the present review examined whether treatment was differentially effective for men and women. Although Jarrell and Ridgely’s [ 93 ] evaluation of group BS, group TS and individual case management for individuals with SUD and co-occurring Axis I disorders did not examine whether group treatment types were differentially effective for men and women, data indicated that women—regardless of treatment group—reported higher role functioning (i.e.., independent living, work productivity, as well as immediate and extended social relationships), increased psychiatric symptomatology (depression, mania, drug use, alcohol use) across the follow-up periods compared to men.

Race and ethnicity and treatment efficacy

Among the studies included in the present review, only three examined whether treatment efficacy varied as a function of race and ethnicity. A secondary examination of the efficacy of group BS in comparison to group TS and individual case management [ 93 ] suggested that outcomes in each group treatment among ethnic and racial minority clients were equivalent to White participants during the 6-month follow [ 94 ]. The initial evaluation indicated that—regardless of group treatment type—racial/ethnic minority participants reported lower scores in personal well-being, lower life satisfaction (i.e., satisfaction with living), worse role functioning (i.e., independent living, work productivity, immediate and extended social relationships) over the follow-up periods compared to White participants [ 93 ].

Conclusions

In general, participants in group treatment for drug use disorders exhibit more improvement on typical measures of outcome (e.g., abstinence & use rates, objective measures, urinalysis) when compared to standard care without group [ 18 , 109 ] and those who refuse or drop out of treatment [ 110 ]. Specifically, CBT and CM appear to be more effective at reducing cocaine use than TAU groups. CM is effective in increasing periods of abstinence among users of methamphetamine. Both relapse prevention and social support group therapy were effective for marijuana use although relapse prevention was more helpful for men than for women. Brief MI and relapse prevention were both effective at reducing marijuana use. CBT and CBT-related treatments (including the matrix model) when added to pharmacotherapy were more effective for opioid use disorder than pharmacotherapy alone. Effective treatments for Mixed SUD include group CBT, CM, and women’s recovery group. Longer relapse prevention periods appear to be more helpful in reducing mixed SUD. Behavioral skills and behavioral skills plus contingency management helped decreased psychiatric symptoms and drug use behaviors. Psychoeducation groups alone, a commonly used intervention, were not effective at addressing SUD and co-occurring psychiatric problems. Additionally, it is important to note that there is potential for risk of bias in the studies included across four domains: participants, predictors, outcome, and analysis [ 111 ]. The current study did not comprehensively assess for risk of bias and this is a study limitation. Future research could assess for risk of bias by following the guidelines suggested by the Cochrane Handbook [ 112 ].

The current literature offers a wide variety of group treatments with varying goals and based on varying formal change theories. Overall, studies that reported between-group effect size ( n = 7) reported small to medium effect sizes potentially suggesting differences were moderate but of potential theoretical interest. Of those seven studies, only two studies reported large effect sizes (both comparing an active treatment to a delayed treatment/untreated condition). In order to better characterize magnitude of intervention effects, future studies should report effect sizes and their confidence intervals [ 113 , 114 ]. Moreover, groups based on cognitive-behavioral theory [ 35 ], motivational enhancement theory [ 43 ], stages of change theory [ 115 ], 12-step theory [ 41 ] and psychoeducational group models [ 116 ] have all been the subject of recent studies. Steps of treatment have also been used to classify groups for acutely ill individuals with SUD versus middle stage (recovering) or after care groups, with the latter mainly focusing on relapse prevention. Group therapy is provided – at least as an augment to multimodal interventions – in most of the outpatient and inpatient programs in English speaking and European countries [ 17 , 117 ]. Therefore, continued efforts to implement and scale up group-based treatments for SUD known to be effective are needed. CM appears to be effective at addressing various drug use problems and further research should evaluate whether it would also be useful for marijuana use.

Future Research Questions

Studies of other group treatments for SUD that use rigorous, interview-based diagnosis, use control groups, randomly assign participants to condition, report the ethnic and racial composition of the sample, are adequately powered, implement a treatment manual, and compare outcomes to individual treatment as well are necessary.

Little is known regarding the possible mediators and moderators of treatment outcome in group interventions for SUD

Key Learning Objectives

Group treatment approaches are widely utilized and are often less costly to implement than individual treatments, currently we know very little whether one group approach is superior to another in the treatment of SUD.

Group treatment approaches seem to be more effective at improving positive outcomes (e.g., abstinence, use rates, objective measures, urinalysis) when compared to standard care without group [ 18 , 109 ], and those who refuse and drop out of treatment

More thorough randomized controlled trials of group SUD treatments are needed [ 110 ].

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable. The present study does not include original data. However, the authors of the study have listed all articles reviewed in this study in the reference section.

Abbreviations

Twelve Step Facilitation Group Therapy

Alcohol Dependence

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

Addiction Severity Index

Antisocial Personality Disorder

Abbreviated Program

Behavioral Skills

Borderline Personality Disorder

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Cocaine Dependence

Composite Diagnostic Interview Schedule

Contingency Management

Community Reinforcement Approach

Coping Skills

Cognitive Therapy

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy

Day Treatment

Drug Counseling

Diagnostic Interview Schedule

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

Disease and Recovery Model

Delayed to Control

Evidence-Based Practice

Evidence-Based Treatment Practice

Enhanced Group Condition

Enhanced Treatment Program

Family Therapy

Group Drug Counseling

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

HIV Harm Reduction

Harm Reduction

Intensive Group Therapy

Individual Therapy

Motivational Interviewing

Matrix Model

Methadone Maintenance Therapy

National Institute of Drug Abuse

Psychoeducational Therapy Group

Pre-Post with Comparison Group (matched or otherwise)

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

Random Assignment with Control

Relapse Prevention

Recovery Training

Random Assignment to Active Treatment

Relational Psychotherapy Mothers’ Group

Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnosis

Social Support

Standard Group Therapy

Substance Use Disorder

Seeking Safety

Standard Group Counseling

Standard Treatment Program

Treatment as Usual

Phone Monitoring and Counseling, with Support Group

Therapeutic Community Program

Twelve Step

Women’s Recovery Group

Grant BF, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Jung J, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions-III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(1):39–47.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Edition F. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™. 5th ed; 2013.

Google Scholar

Rehm J, Marmet S, Anderson P, Gual A, Kraus L, Nutt DJ, et al. Defining substance use disorders: do we really need more than heavy use? Alcohol Alcohol. 2013;48(6):633–40.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Birnbaum HG, White AG, Schiller M, Waldman T, Cleveland JM, Roland CL. Societal costs of prescription opioid abuse, dependence, and misuse in the United States. Pain Med. 2011;12(4):657–67.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Center NDI. National Drug Threat Assessment. Washington: United States Department of Justice; 2011.

Florence CS, Zhou C, Luo F, Xu L. The economic burden of prescription opioid overdose, abuse, and dependence in the United States, 2013. Med Care. 2016;54(10):901–6.

Kamal R, Cox C, Rousseau D, Foundation ftKF. Costs and outcomes of mental health and substance use disorders in the US. JAMA. 2017;318(5):415.

Hall WD, Patton G, Stockings E, Weier M, Lynskey M, Morley KI, et al. Why young people's substance use matters for global health. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(3):265–79.

Khalsa JH, Treisman G, McCance-Katz E, Tedaldi E. Medical consequences of drug abuse and co-occurring infections: research at the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Subst Abus. 2008;29(3):5–16.

McCoy CB, Lai S, Metsch LR, Messiah SE, Zhao W. Injection drug use and crack cocaine smoking: independent and dual risk behaviors for HIV infection. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14(8):535–42.

Contoreggi, md C, Rexroad, rph VE, Lange, md, et al. Current Management of Infectious Complications in the injecting drug user. J Subst Abus Treat. 1998;15(2):95–106.

Article Google Scholar

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JAM, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71–2.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

American Psychological Association PTFoE-BP. Evidence-based practice in psychology. Am Psychol. 2006;61:271–85.

Pope C. Resisting evidence: the study of evidence-based medicine as a contemporary social movement. Health. 2003;7(3):267–82.

Wendt D. Group therapy for substance use disorders: a survey of clinician practices. J Groups Addict Recover. 2017;12(4):243 EOA.

Johnson J. Using research-supported group treatments. J Clin Psychol In Session. 2008;64(11):1206–24.

Stinchfield RD, Owen P, Winters K. Group therapy for substance abuse: A review of the empirical research. In: Burlingame AFG, editor. Handbook of group psychotherapy. New York: Wiley; 1994. p. 458–88.

Fisher MS Sr, Bentley KJ. Two group therapy models for clients with a dual diagnosis of substance abuse and personality disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47(11):1244–50.

Kaminer Y, Burleson JA, Blitz C, Sussman J, Rounsaville BJ. Psychotherapies for adolescent substance abusers: a pilot study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186(11):684–90.

McKay JR, Alterman AI, Cacciola JS, O'Brien CP, Koppenhaver JM, Shepard DS. Continuing care for cocaine dependence: comprehensive 2-year outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(3):420–7.

McKay JR, Alterman AI, Cacciola JS, Rutherford MJ, O'Brien CP, Koppenhaver J. Group counseling versus individualized relapse prevention aftercare following intensive outpatient treatment for cocaine dependence: initial results. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65(5):778–88.

Shaffer HJ, LaSalvia TA, Stein JP. Comparing hatha yoga with dynamic group psychotherapy for enhancing methadone maintenance treatment: a randomized clinical trial. Altern Ther Health Med. 1997;3(4):57–66.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Morgan-Lopez AA, Fals-Stewart W. Analytic methods for modeling longitudinal data from rolling therapy groups with membership turnover. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(4):580–93.

Weiss RD. Treating patients with bipolar disorder and substance dependence: lessons learned. J Subst Abus Treat. 2004;27(4):307–12.

Lundahl BW, Kunz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, Burke BL. A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: twenty-five years of empirical studies. Res Soc Work Pract. 2010;20(2):137–60.

Weiss RD, Jaffee WB, de Menil VP, Cogley CB. Group therapy for substance use disorders: what do we know? Harvard Rev Psychiatry. 2004;12(6):339–50.

Burlingame GM, MacKenzie KR, Strauss B. Bergin & Garfields Handbook Of Psychotherapy And Behavior Change. Small group treatment: Evidence for effectiveness and mechanisms of change. In: Lambert M, editor. Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change. 5th ed. New York: Wiley; 2003. p. 647–96.

Beck AT. Cognitive therapy: nature and relation to behavior therapy. Behav Ther. 1970;1(2):184–200.

Guydish J, Sorensen JL, Chan M, Werdegar D, Bostrom A, Acampora A. A randomized trial comparing day and residential drug abuse treatment: 18-month outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(3):428–34.

Guydish J, Werdegar D, Sorensen JL, Clark W, Acampora A. Drug abuse day treatment: a randomized clinical trial comparing day and residential treatment programs. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66(2):280–9.

Avants SK, Margolin A, Sindelar JL, Rounsaville BJ, Schottenfeld R, Stine S, et al. Day treatment versus enhanced standard methadone services for opioid-dependent patients: a comparison of clinical efficacy and cost. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(1):27–33.

Avants SK, Margolin A, Usubiaga MH, Doebrick C. Targeting HIV-related outcomes with intravenous drug users maintained on methadone: a randomized clinical trial of a harm reduction group therapy. J Subst Abus Treat. 2004;26(2):67–78.

Maude-Griffin PM, Hohenstein JM, Humfleet GL, Reilly PM, Tusel DJ, Hall SM. Superior efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for urban crack cocaine abusers: main and matching effects. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66(5):832–7.

Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Martin RA, Michalec E, Abrams DB. Brief coping skills treatment for cocaine abuse: 12-month substance use outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(3):515–20.

Beck ATW, F. D.; Newman, C. F.; Liese, B. S. Cognitive therapy of substance abuse. New York: Guilford; 1993.

McAuliffe WE. A randomized controlled trial of recovery training and self-help for opioid addicts in New England and Hong Kong. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1990;22(2):197–209.

Czuchry M, Dansereau DF. Node-link mapping and psychological problems. Perceptions of a residential drug abuse treatment program for probationers. J Subst Abus Treat. 1999;17(4):321–9.

Article CAS Google Scholar

McCusker J, Bigelow C, Frost R, Garfield F, Hindin R, Vickers-Lahti M, et al. The effects of planned duration of residential drug abuse treatment on recovery and HIV risk behavior. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(10):1637–44.

Rosenblum A, Magura S, Kayman DJ, Fong C. Motivationally enhanced group counseling for substance users in a soup kitchen: a randomized clinical trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;80(1):91–103.

Marlatt GA, Donovan DM. Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2005. p. xiv, 416-xiv

Crits-Christoph P, Siqueland L, Blaine J, Frank A, Luborsky L, Onken LS, et al. Psychosocial treatments for cocaine dependence: National Institute on Drug Abuse collaborative cocaine treatment study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(6):493–502.

Luthar SSS, N.E.; Altomare, M. Relational psychotherapy Mother’s group: A randomized clinical trial for substance abusing mothers. Dev Psychopathol. 2007;19:243–61.

Miller WRR, S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 1991.

Hoffman JA, Caudill BD, Koman JJ 3rd, Luckey JW, Flynn PM, Mayo DW. Psychosocial treatments for cocaine abuse. 12-month treatment outcomes. J Subst Abus Treat. 1996;13(1):3–11.

Kaminer Y, Burleson JA, Goldberger R. Cognitive-behavioral coping skills and psychoeducation therapies for adolescent substance abuse. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190(11):737–45.

Linehan M. DBT skills training manual. 2nd ed. London: The Guilford Press; 2015.

Petry NM. Contingency management: what it is and why psychiatrists should want to use it. Psychiatrist. 2011;35(5):161–3.

Logan DE, Marlatt GA. Harm reduction therapy: a practice-friendly review of research. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66(2):201–14.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ellis B, Bernichon T, Yu P, Roberts T, Herrell JM. Effect of social support on substance abuse relapse in a residential treatment setting for women. Eval Program Plan. 2004;27(2):213–21.

Nowinski J, Baker S. The twelve-step facilitation handbook: A systematic approach to early recovery from alcoholism and addiction. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1992. p. xxii. 215-xxii

Najavits LM. Seeking safety: a treatment manual for PTSD and substance abuse. New York: Guilford; 2002.

Greenfield SF, Trucco EM, McHugh RK, Lincoln M, Gallop RJ. The Women's recovery group study: a stage I trial of women-focused group therapy for substance use disorders versus mixed-gender group drug counseling. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90(1):39–47.

Liddle HA, Dakof GA, Parker K, Diamond GS, Barrett K, Tejeda M. Multidimensional family therapy for adolescent drug abuse: results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2001;27(4):651–88.

Coviello DM, Alterman AI, Rutherford MJ, Cacciola JS, McKay JR, Zanis DA. The effectiveness of two intensities of psychosocial treatment for cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;61(2):145–54.

Crits-Christoph P, Siqueland L, McCalmont E, Weiss RD, Gastfriend DR, Frank A, et al. Impact of psychosocial treatments on associated problems of cocaine-dependent patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(5):825–30.

Siqueland L, Crits-Christoph P, Gallop R, Barber JP, Griffin ML, Thase ME, et al. Retention in psychosocial treatment of cocaine dependence: predictors and impact on outcome. Am J Addict. 2002;11(1):24–40.

Mercer D, Carpenter G, Daley D. The adherence and competence scale for group addiction counseling for TCACS: Center for Psychotherapy Research, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania Medical School; 1994.

Luborsky L. Principles of psychoanalytic psychotherapy a manual for supportive-expressive treatment; 1984.

Epstein DH, Hawkins WE, Covi L, Umbricht A, Preston KL. Cognitive-behavioral therapy plus contingency management for cocaine use: findings during treatment and across 12-month follow-up. Psychol Addict Behav. 2003;17(1):73–82.

Magura S, Rosenblum A, Lovejoy M, Handelsman L, Foote J, Stimmel B. Neurobehavioral treatment for cocaine-using methadone patients: a preliminary report. J Addict Dis. 1994;13(4):143–60.

Petry NM, Alessi SM, Hanson T. Contingency management improves abstinence and quality of life in cocaine abusers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(2):307–15.

Rawson RA, Huber A, McCann M, Shoptaw S, Farabee D, Reiber C, et al. A comparison of contingency management and cognitive-behavioral approaches during methadone maintenance treatment for cocaine dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(9):817–24.

Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Rubonis AV, Gulliver SB, Colby SM, Binkoff JA, et al. Cue exposure with coping skills training and communication skills training for alcohol dependence: 6- and 12-month outcomes. Addiction. 2001;96(8):1161–74.

Rosenblum A, Magura S, Foote J, Palij M, Handelsman L, Lovejoy M, et al. Treatment intensity and reduction in drug use for cocaine-dependent methadone patients: a dose-response relationship. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1995;27(2):151–9.

Rosenblum A, Magura S, Palij M, Foote J, Handelsman L, Stimmel B. Enhanced treatment outcomes for cocaine-using methadone patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;54(3):207–18.

Volpicelli JR, Markman I, Monterosso J, Filing J, O'Brien CP. Psychosocially enhanced treatment for cocaine-dependent mothers: evidence of efficacy. J Subst Abus Treat. 2000;18(1):41–9.

Weinstein SP, Gottheil E, Sterling RC. Randomized comparison of intensive outpatient vs. individual therapy for cocaine abusers. J Addict Dis. 1997;16(2):41–56.

Gottheil E, Weinstein SP, Sterling RC, Lundy A, Serota RD. A randomized controlled study of the effectiveness of intensive outpatient treatment for cocaine dependence. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(6):782–7.

Magura S, Rosenblum A, Fong C, Villano C, Richman B. Treating cocaine-using methadone patients: predictors of outcomes in a psychosocial clinical trial. Subst Use Misuse. 2002;37(14):1927–55.

Jaffe A, Shoptaw S, Stein J, Reback CJ, Rotheram-Fuller E. Depression ratings, reported sexual risk behaviors, and methamphetamine use: latent growth curve models of positive change among gay and bisexual men in an outpatient treatment program. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15(3):301–7.

Rawson RA, Marinelli-Casey P, Anglin MD, Dickow A, Frazier Y, Gallagher C, et al. A multi-site comparison of psychosocial approaches for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Addiction. 2004;99(6):708–17.

Roll JM, Chudzynski J, Cameron JM, Howell DN, McPherson S. Duration effects in contingency management treatment of methamphetamine disorders. Addict Behav. 2013;38(9):2455–62.