Advertisement

A systematic review of climate migration research: gaps in existing literature

- Review Paper

- Open access

- Published: 16 April 2022

- Volume 2 , article number 47 , ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Rajan Chandra Ghosh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9027-6649 1 , 2 &

- Caroline Orchiston ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3171-2006 1

10k Accesses

9 Citations

12 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Climatic disasters are displacing millions of people every year across the world. Growing academic attention in recent decades has addressed different dimensions of the nexus between climatic events and human migration. Based on a systematic review approach, this study investigates how climate-induced migration studies are framed in the published literature and identifies key gaps in existing studies. 161 journal articles were systematically selected and reviewed (published between 1990 and 2019). Result shows diverse academic discourses on policies, climate vulnerabilities, adaptation, resilience, conflict, security, and environmental issues across a range of disciplines. It identifies Asia as the most studied area followed by Oceania, illustrating that the greatest focus of research to date has been tropical and subtropical climatic regions. Moreover, this study identifies the impact of climate-induced migration on livelihoods, socio-economic conditions, culture, security, and health of climate-induced migrants. Specifically, this review demonstrates that very little is known about the livelihood outcomes of climate migrants in their international destination and their impacts on host communities. The study offers a research agenda to guide academic endeavors toward addressing current gaps in knowledge, including a pressing need for global and national policies to address climate migration as a significant global challenge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Climate-Conflict-Migration Nexus: An Assessment of Research Trends Based on a Bibliometric Analysis

Scales and sensitivities in climate vulnerability, displacement, and health

Climate change-induced migration: a bibliometric review

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Population displacement can be driven by climatic hazards such as floods, droughts (hydrologic), and storms (atmospheric), and geophysical hazards such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and tsunami (Smith and Smith 2013 ). The interactions between natural hazard events, and social, political, and human factors, frequently act to intensify the negative effects of climatic and geophysical hazards, leading to political and social unrest, increased social vulnerability, and human suffering. As a consequence of these adverse effects, people migrate from their native land, causing stress, uncertainty, and loss of lives and properties. However, such migration can also have positive impacts on migrants’ lives. For example, migrants may be able to diversify their livelihood and have greater access to education or healthcare.

In 2020, 30.7 million people from 149 countries and territories were displaced due to different natural disasters. Among them, climatic disasters were solely responsible for displacing 30 million people within their own country, with the highest recorded displacement occurring in 2010 when 38.3 million people were displaced (IDMC 2021a ; IOM 2021 ). It is difficult to estimate the actual number of people that moved due to the impacts of climate change (Mcleman 2019 ), because peoples’ migration decisions are triggered by a range of contextual factors (de Haas 2021 ). Nevertheless, the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) states that approximately 283.4 million people were displaced internally between the years 2008 and 2020 because of climatic disasters across the globe (Table 1 ). This number represents almost 89% of the total disaster-induced displacement that occurred during this timeframe (IDMC 2021a ).

People who move from their homes due to climate-driven hazards are described in a range of ways, including climate migrants, environmental migrants, climate refugees, environmental refugees, and so on (Perkiss and Moerman 2018 ). The process of migration related to climate-driven hazards is variously described as environmental migration, environmental displacement, climate-induced migration or climigration (Bronen 2008 ).

In this research, we focus on climate-induced migration more specifically induced by slow-onset climatic disasters (sea-level rise, drought, salinity etc.), rapid onset extreme climatic events (storms, floods etc.), or both (precipitation, erosion etc.). This study investigates how climate change-induced migration studies are framed in the existing literature and identifies key gaps in the published literature.

There is a significant ongoing debate about the links between climate change and human migration in the academic literature. Some researchers strongly believe that climate change directly causes people to move, whereas the others argue that climate change is just one of the contextual factors in peoples’ migration decisions (Laczko and Aghazarm 2009 ). Although there are scholarly opinions that call into question climate change as a primary cause of migration (Black 2001 ; Black et al. 2011 ; McLeman 2014 ), there is also evidence that climate change causes severe environmental effects and exacerbates the vulnerabilities of people that force them to leave their place of living (Bronen and Chapin 2013 ; Laczko and Aghazarm 2009 ; McLeman 2014 ).

Moreover, the relationship between the adverse effects of climate change and different types of human mobility (migration, displacement, or planned relocation) has become increasingly recognized in recent years (Kälin and Cantor 2017 ). It is assumed in general that the number of climate displaced people is likely to increase in future (Mcleman 2019 ; Wilkinson et al. 2016 ), and climate change could permanently displace an estimated 150 million to nearly 1 billion people as a critical driver by 2050 (Held 2016 ; Perkiss and Moerman 2018 ). As the number of climate migrants increases rapidly in some areas of the world (IDMC 2017 ), it is now confirmed as a significant global challenge (Apap 2019 ) and recognized as a considerable threat to human populations (Ionesco et al. 2017 ).

Climate migration has multifaceted impacts on peoples’ livelihoods. Being displaced from their home, people migrate within their own country, described as internal migration, or across borders to other countries known as international migration. Internal movements of climate migrants occur mostly to nearby major cities or large urban centers (Poncelet et al. 2010 ). Climate migrants who try to move internationally are significantly challenged by two different security problems. Firstly, they cannot live in their own homeland because of worsening climatic impacts and are forced to leave their ancestral land. Secondly, they cannot move to other countries quickly to find a safer place because, according to international law, climate migrants are not refugees and they are not supported by the UN Refugee Convention or any international formal protection policies (Apap 2019 ; Mcleman 2019 ). In this situation, they live with significant livelihood uncertainty. The United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (SFDRR) recognize them as a key group that is highly exposed and vulnerable because of their circumstances (Ionesco et al. 2017 ). Hence, policy development to address complex climate migration issues has become an emerging priority around the globe (Apap 2019 ).

In order to address this global challenge, there has been growing academic and policy attention focused on regional (Kampala Convention-2009 by African Union), national (Nansen Initiative—2012 by Norway and Switzerland), and international (Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration- 2018 by United Nations) levels of climate-induced migration in recent years. Myers’s ( 2002 ) seminal article signposted environmentally driven migration as one of the most significant challenges of the twenty-first century, and later, similar assumptions were made by Christian Aid (Baird et al. 2007 ), IOM (Brown 2008 ), and Care International (Warner et al. 2009 ). Such predictions led to a proliferation of the academic discourse on migration, focused on national and international security, policy frameworks, and human rights (Boncour and Burson 2009 ). Other studies have focused on vulnerability assessment, risk reduction, adaptation, resettlement, relocation, sustainability, and resilience, considering pre-, during and post-disaster circumstances of climate migration (Bronen 2011 ; Bronen and Chapin 2013 ; IDMC 2019 ; IOM 2021 ; King et al. 2014 ).

This research contributes to the discourse by identifying the gaps in the published literature regarding climate migration. A systematic literature review was undertaken to shed light on the current extent of academic literature, including gaps in knowledge to develop a climate migration research agenda. Two notable review papers provided a solid foundation for this endeavor. First, Piguet et al. ( 2018 ) developed a comprehensive review of publications on environment-induced migration from a global perspective based on a bibliographic database—CliMig. Their detailed mapping of environmentally induced migration research focused on five categories of climatic hazards (droughts, floods, hurricanes, sea-level rise, and rainfall); however, it did not include salinity and erosion which are also climate-driven and has direct effects on internal and international migration (Chen and Mueller 2018 ; Mallick and Sultana 2017 ; Rahman and Gain 2020 ).

The second key review paper was by Obokata et al. ( 2014 ), which provided an evidence-based explanation of the environmental factors leading to migration, and the non-environmental factors that influence the migration behaviors of people. Their scope of analysis was limited to international migration and excluded other types of migration, such as internal climate-induced migration.

Although migration, or more specifically environmental migration, was occurring over many decades of the twentieth century, the IPCC First Assessment report was released in 1990, which presented the first indications of the risks of climate change-induced human movement (IPCC 1990 ). This milestone report then stimulated the academic discourse, and consequently, a rapid increase in climate migration publication resulted. For this reason, the current study undertook a systematic review of literature across three decades beginning in 1990 and ending in 2019. This study aims to understand how the published literature has framed the climate-induced migration discourse. This paper identifies the key gaps in existing scholarship in this field and proposes a research agenda for future consideration on current and emerging climate migration issues.

In the following section, we outline the systematic review method and identify how journal articles were searched, selected, reviewed, and analyzed. In the next section, we present the results of this study. Results are organized into four subsections that illustrate the reviewed literature in the following ways—spatial and temporal trends, disciplinary foci, triggering forces of migration, and other key issues. Finally, we conclude by identifying research gaps, addressing the limitations of this study, and presenting a research agenda.

Methodology

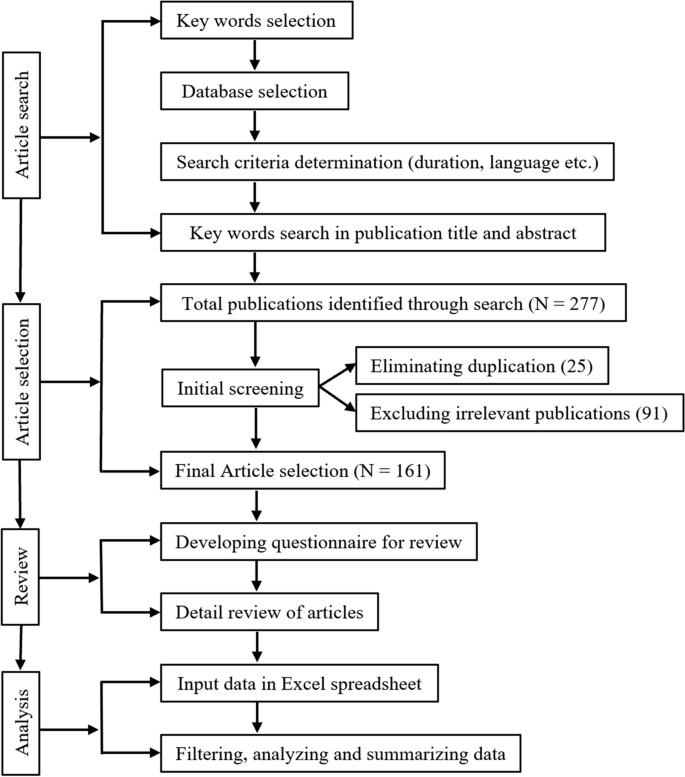

We have adopted a systematic review methodology for this study because it provides an …overall picture of the evidence in a topic area which is needed to direct future research efforts (Petticrew and Robert 2006 ). Systematic reviews reduce the bias of a traditional narrative review, although it is challenging to eliminate researcher bias while interpreting and synthesizing results (Doyle et al. 2019 ). It also limits systematic bias by identifying, evaluating, and synthesizing all relevant studies to answer specific questions or sets of questions, and produces a scientific summary of the evidence in any research area (Petticrew and Robert 2006 ). Moreover, systematic reviews effectively address the research question and identify knowledge gaps and future research priorities (Mallett et al. 2012 ). We have adopted this approach following the methodology developed by Berrang-Ford et al. ( 2011 ) which was tested in the field of environmental and climate change studies, with measurable outcomes. We have conducted the review following these four steps—article search, selection, review, and analysis (Fig. 1 ).

Systematic review flowchart

Article search

We conducted a comprehensive literature search to identify the published academic literature on climate-induced migration to develop a clear understanding of this field of study. We identified sixteen commonly used keywords to search for articles that are predominantly used in the literature. ProQuest central database was selected and used in consultation with a skilled subject librarian to search for the relevant articles for this study. We conducted this literature search in July 2019 using the key thesaurus terms, presented in Table 2 . All keywords were then searched individually in the publication’s title and abstract. We only considered English language peer-reviewed articles for this study, published between the years 1990 and 2019 (up to June).

Article selection

The main purpose of this process was to ensure the selection of appropriate literatures for further analysis. We approached the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA), a systematic evaluation tool, which was also used by Huq et al. ( 2021 ). In stage one of the selection process, 277 articles were counted based on our search criteria. In stage two, we excluded 25 duplicates, and 252 articles remained for further assessment. In the third and final stage of the detailed assessment of each paper, we identified a further 91 publications that were not relevant to our study but appeared in our searched list because search terms were briefly mentioned in their title and/or abstract without being described in further detail. As these articles did not fit with the aim and content of this research, we excluded those 91 and selected a final 161 articles for this study.

Article review

All the selected articles were then considered for detailed review in order to achieve the purpose of the study. A questionnaire (Online Attachment—A) was developed partially following Berrang-Ford et al. ( 2011 ); Obokata et al. ( 2014 ) and Piguet et al. ( 2018 ) to investigate how climate migration studies are framed in the published literature. Then each article was reviewed in detail in response to the individual parameters of the questionnaire such as general information ( article title, authors name, publication year, journal, discipline, content ), methodological approach ( qualitative, quantitative, mixed ), focused study areas ( country, climatic zones ), source of migrants ( rural, urban ), migration types ( internal, international ), impacts of climate migration ( social, economic, political, health, cultural, environmental, security ), causes of migration ( climatic: flood, sea-level rise, drought etc ., other: socio-economic, political, cultural ), target communities ( displaced community, receiving community ), and livelihoods ( housing, income, employment, etc . ) of climate migrants described in the publications.

Article analysis

All the data were recorded in Microsoft Office Excel spreadsheets. Relevant data for each parameter were filtered, analyzed, and summarized using the necessary Excel tools. Referencing was compiled through Mendeley Desktop.

Spatial and temporal trend

General information.

In this section, the publication date of the reviewed articles was used in order to identify the development of the academic discourse in climate migration studies over the last three decades (1990–2019). Results show the increasing focus of academic attention on this area of research over that timeframe. The study found only four publications between the years 1990 and 1999. During 2000–2009, an additional 16 articles were published, which was followed by an almost 90 percent (141 publications) increase in reviewed articles over the period of 2010–2019 (Table 3 ).

Reviewed study areas

In 84 reviewed articles, the study reported research focused on a particular location, and in some cases, they considered two or more areas for their research. Therefore, multiple counting for each study has been considered, which represents all the continents except Antarctica. The analysis shows that Asia (38%) is the continent with the greatest number of climate migration studies, followed by Oceania (20%), North America (17%), and Africa (14%). In contrast, Europe and South America have received less attention, with 7% and 5%, respectively. Table 4 presents the distribution of study areas by continent focused on the reviewed papers.

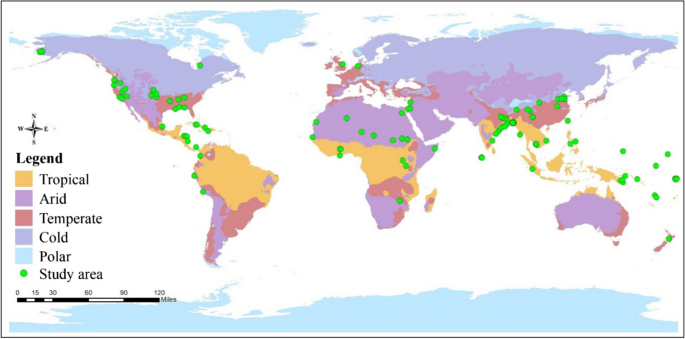

Climatic zones of the reviewed studies

This study identified the climatic zones of the study areas in order to find out which zones are most commonly studied among the reviewed studies. We adopted the climatic zones of the world from Peel et al. ( 2007 ), which is the updated version of Koppen’s climate classification, and categorizes the world climate into five major zones, i.e., (i) tropical, (ii) arid, (iii) temperate, (iv) cold, and (v) polar. This review shows that 86 publications mentioned their study areas, equating to 54% of the total reviewed papers. Among them, 81% referred to a specific region as their study area. The study areas were then classified into the above-mentioned climatic zones with one reference offered randomly for each country as an example of the range of research that has been conducted.

This study reveals that 49% of this group (among 81%) focused on tropical climatic areas such as Bangladesh (Islam et al. 2014 ), Cambodia (Jacobson et al. 2019 ), Kiribati (Bedford et al. 2016 ), Papua New Guinea (Connell and Lutkehaus 2017 ), Philippines (Tanyag 2018 ), Tuvalu (Locke 2009 ), and Vanuatu (Perumal 2018 ) among others, and 16% focused on arid climatic zones such as African Sahel (McLeman and Hunter 2010 ), Israel (Weinthal et al. 2015 ), Peru (Scheffran 2008 ), and Senegal (Nawrotzki et al. 2016a , b ). In addition to these, 13% of authors focused on temperate regions, i.e., Mexico (Nawrotzki et al. 2016a , b ), Nepal (Chapagain and Gentle 2015 ), Taiwan (Kang 2013 ), UK (Abel et al. 2013 ), and the USA (Rice et al. 2015 ) for their study and 3% focused on cold climatic areas, i.e., Alaska: USA (Marino and Lazrus 2015 ), Canada (Omeziri and Gore 2014 ), and northern parts of China (Ye et al. 2012 ). No studies were found based on polar regions (Fig. 2 ). Some studies did not specify a region or country of study but instead focused on broader regions such as Africa (White 2012 ), Asia–Pacific (Mayer 2013 ), Europe (Werz and Hoffman 2016 ), Latin America (Wiegel 2017 ), and Pacific (Hingley 2017 ).

Climatic zones of the reviewed study areas-adopted from Peel (2007)

Migration types and sources of climate migrants

Migration types here refer to whether migration was internal (within a country or region) or international (across borders), and sources of climate migrants refer to people from rural or urban source regions. Most authors (73%) mentioned nothing regarding migration types, but a quarter (27%) explicitly discussed internal or international migration. Among them, 11% described climate migration within countries and 10% investigated cross-border migration. Some authors (6%) were concerned with both internal and international climate migration. Source regions for climate migrants were not often considered, with only 19 publications mentioning the origin of migrants. Among these, 11 articles stated that migration occurred from rural areas, and two publications discussed migration from urban areas. Also, six articles described climate migration from both rural and urban areas.

Disciplinary foci

Research discipline.

This study reveals that climate migration studies are becoming more focal issues in different research disciplines that include more than 40 subject areas. Hence, we developed a typology for the reviewed articles based on the relevant research themes. The typology consists of six research disciplines, each of which includes different subjects, as follows.

Social sciences: Social sciences, Sociology, Political Science, International Relations, Comprehensive Works, Population Studies, Anthropology, Social Services and Welfare, History, Philosophy, Ethnic Interests, Civil Rights, Women's Studies

Geography and environment: Meteorology, Environmental Studies, Energy, Conservation, Earth Sciences, Geography, Agriculture, Geology, Biology, Archaeology, Pollution

Business studies and development: Management, Business and Economics, International Commerce, International Development and Assistance, Economics, Insurance, Investments, Accounting

Law, policy, and planning: Law, Military, Civil Defense, Criminology and Security, Environmental policy

Health and medical science: Public Health, Psychology, Medical Sciences, Physical Fitness, and Hygiene

Other: Literature, Library and Information Sciences, Physics, Technology

Among the reviewed publications, some articles were discussed from the perspective of one particular discipline, while others came from two or more disciplines. Therefore, multiple counting for each discipline was considered during the analysis. The study reveals that Social Science covers the highest percentage of publications (41%), followed by Geography and Environment (30%), Business Studies and development (10%), Law, policy and planning (9%), and Health and medical science (7%). Only 2% of publications are not covered by any of these disciplines.

Primary research themes

The authors discussed a diverse range of themes in the reviewed articles. Key themes have been classified into eight categories based on their topics and focusing subjects. Some of the publications focused on multiple themes, which were counted separately under each theme. Most of the authors (27%) focused on Politics and policy issues, and almost a fifth (18%) of total articles focused on the themes of population, health, and development issues. Human rights, conflicts, and security issues were discussed in 16% of papers, and climate, vulnerability, adaptation, and resilience topics were the focus of 12% of publications. In 11% of publications, the authors focused on identity and cultural issues, and socio-economic topics comprised a further 9% of the total. Environmental issues were discussed by 4% of reviewed articles and 3% of publications did not fit into any of the above categories and are described as Other.

Methodological approaches

This review identified that researchers applied both qualitative and quantitative methods in climate migration research. A total of 82% of the reviewed articles used qualitative methodologies, and 9% quantitative. In addition to these, 9% of articles used mixed methods in climate migration research. Of those who used qualitative studies, most were review-based (86%), comprising systematic review, empirical evidence-based review, critical synthesis review, critical discourse review, and policy review. Only 14% of qualitative studies used interview methods (7%), case studies (6%), and focus group discussion (1%). Data sources reported in the reviewed literature for the quantitative research included secondary data (73%), historical data (13%), remote sensing data (7%), and survey data (7%).

Triggering forces of migration

Climatic causes of migration.

The reviewed publications outlined a range of different causes of climate migration. This study reveals nineteen climate-related causes of migration. We merged these causes into eight categories, defined as (i) climate change (climate change, global warming, temperature, environmental change, climate-induced natural disaster, meteorological events, extreme weather, heatwave), (ii) flood, (iii) sea-level rise (sea-level rise, melting glacier), (iv) drought (drought, desertification), (v) storm (storm, cyclone, hurricane, typhoon), (vi) salinity (salinity, tidal surge), (vii) precipitation-induced landslide, and (viii) erosion (coastal erosion, river erosion). “Climate change” is defined as a separate category because some publications named climate change as an overarching driver of migration, rather than specifying any particular hazard. In 70 publications, authors mentioned particular climatic events that were solely responsible for human migration, and 53 of these articles predominantly identified climate change as the main driver of migration, followed by sea-level rise (6), drought (4), flood (3), storm (2), and precipitation-induced landslide (2). In the remaining articles, scholars identified two or more climatic events that were collectively responsible for human displacement. Based on these articles, multiple counting for each climatic event was considered and the results show that climate change was the most commonly cited cause in 126 articles, along with other climatic causes. The authors also identified sea-level rise, drought, flood, and storms as the significant drivers of peoples’ migration along with other climatic drivers, which were mentioned in 51, 46, 44, and 43 articles, respectively. Precipitation-induced landslide and erosion were recognized in 17 and 12 articles, respectively, as the causes of human displacement, whereas eight articles identified salinity as the main reason.

Influencing causes of migration

Although this review was focused on identifying the climatic causes of human displacement, some other causes emerged during the analysis that also influence migration. In 68 publications, economic, social, environmental, political, cultural, and psychological causes were stated as drivers of migration, in addition to the climatic causes. Among these, economic causes (32%) have been identified as the most common driver, followed by social (25%) and environmental (22%) causes. Some articles described political causes (16%), and the remainder mentioned cultural (3%) and psychological (1%) drivers of migration.

Other key issues

- Impacts of climate migration

One of the key findings of this review concerns the impacts of climate migration. In 48 publications, authors described a range of different impacts caused by climate migration, such as social, economic, political, health, cultural, environmental, and security. All the impacts were identified based on the location of climate migrants which are classified into the following three categories: (i) impacts on the place of origin, (ii) impacts on the place of destination, and (iii) impacts on both origin and destination. The review demonstrates that the impacts of climate migration were more frequently identified for the place of origin rather than for the destination. In the place of origin, authors discussed the economic, social, and cultural impacts, compared to political, security, health, and environmental impacts. In contrast, in the destination, scholars were more focused on security and cultural impacts. Overall, security, cultural and economic impacts were the most frequently discussed themes by the authors of reviewed literature in comparison with other impacts (Table 5 ).

Discussed communities

More than half of the reviewed articles ( N = 81) described climate migrants and/or their receiving communities. In most of the discussions, authors talked about both displaced and host communities together (57%). In more than two-fifths of articles, they considered only displaced communities (42%). In contrast, none of the authors of the reviewed literature discussed host communities in detail in their publications, except Dorent ( 2011 ). Only a few authors briefly mentioned host communities during the discussion of climate migration impacts.

Livelihoods of climate migrants

This review demonstrates that the overall livelihood of climate migrants has not been a key focus in any of the reviewed literature. However, a few separate parameters of livelihoods, including housing, income and employment, health, access to resources, and education were mentioned in 23 articles. The analysis shows that the livelihoods of migrants in their place of origin (71%) were more likely to be considered compared to their destination (11%). In some articles (18%), authors addressed the livelihoods of climate migrants considering both their place of origin and destination. In total, all the articles which considered livelihoods had a specific focus on internal migration, and none mentioned the livelihoods of climate migrants in terms of international migration.

Discussion and research gaps

Climate change-induced migration is neither new (Nagra 2017 ), nor a future hypothetical phenomenon—it is a current reality (Coughlin 2018 ). This review provides a comprehensive analysis of how this field of study is framed in the existing literature. The academic discourse on human migration due to climate change is suggestive of a long-standing causal connection, which is hard to dissociate (Milán-García et al. 2021 ; Parrish et al. 2020 ; Piguet et al. 2011 ).

The review of spatial and temporal trends of climate-induced migration studies illustrates the growth in the field since the release of 1st IPCC report in 1990. In addition, this review has explored some basic questions that are useful to guide future research in this field of study, for instance, which study areas have received greater or lesser focus? Where are these study areas located in relation to global climatic zones? How are people migrating, i.e., internally, or internationally? What are the spatial sources of climate-induced migrants, i.e., rural, or urban environments?

This review also demonstrates that the expansion of climate migration research increased rapidly after 2000, although the studies in this field began before 2000 (Table 3 ). It denotes that the global academia and policymakers have emphasized their focus on this topic in recent decades (Milán-García et al. 2021 ; Piguet et al. 2011 ). Moreover, this review identifies the Asia–Pacific region as the global ‘hotspot’ of climate migration research (Table 4 ). This reflects the IDMC ( 2019 ) report that states more than 80% of the total displacement between 2008 and 2018 occurred within this region. Moreover, a significant proportion of global environmental displacement will continue to occur in the Asia–Pacific region (Mayer, 2013 ). Therefore, this region could be considered as a critical ‘living laboratory’ for future climate migration research.

Climate migration is mostly occurring internally (IDMC 2021a ; Laczko and Aghazarm 2009 ), and in recent years, it has been widely acknowledged in the policy areas (Fussell et al. 2014 ; The World Bank 2018 ). Nevertheless, this study reveals that only a quarter of the reviewed studies for example, Chapagain and Gentle ( 2015 ), Islam et al. ( 2014 ), and Prasain ( 2018 ) have considered the migration types (internal or international) and sources (rural or urban) of climate migrants in their research. Thus, this review identifies the gap and need for contributions to the academic discourse that investigate migration types, the origin of migrants, and their patterns of migration.

The review of the disciplinary foci of climate-induced migration literature reveals that a broader range of disciplines are now focusing on this research topic, which suggests that greater interdisciplinarity is developing in the discourse. IDMC ( 2021b ) data presented in Table 1 show that climate-induced disasters are displacing millions of people every year, but surprisingly none of the reviewed publications appeared under the subject category of disaster management in the database. This reflects the emergent nature of the academic discourse on climate migration and disaster management, which includes recent studies by Ye et al. ( 2012 ), Tanyag ( 2018 ), and Hamza et al. ( 2017 ). In addition, politics and policy issues regarding climate migration were discussed by scholars; however, no country-specific policies were found during the review that considered both the origin and host communities of climate migrants.

Campbell ( 2014 ) argues that there is insufficient empirical evidence within climate migration research. However, this review reveals that research in this area has been undertaken using a range of methodologies, from qualitative (review, case study, interview, focus group discussion etc.) to quantitative (based on survey data, secondary data, historical data, and remote sensing data), which has produced a strong foundation of work to guide future pathways for interdisciplinary climate migration research. A significant proportion of the research to date has been review-based. Also, there is a lack of empirical studies in this research field that consider the application of geographic information system and remote sensing.

It is clear from reviewing the triggering forces of climate-induced migration literature that climatic events are dominantly responsible for climate migration, which is supported by Rahman and Gain ( 2020 ), Connell and Lutkehaus ( 2017 ), Gemenne ( 2015 ), and Kniveton et al. ( 2012 ). Despite this, there are some other influencing push and/or pull factors such as socio-economic, political, cultural, etc., which are likely to compound (or be compounded by) climate impacts, to trigger the migration process (Black et al. 2011 ; de Haas 2011 , 2021 ; Fussell et al. 2014 ). While there remains ample anecdotal evidence of the relationship between climate change impacts and migration, the specific reasons for people to decide to migrate are interwoven with indirect pressures, such as livelihood disruption, poverty, war, or disaster (Werz and Hoffman 2016 ). Moreover, why people choose to stay at their places is also essential in the context of creeping environmental and climate-induced migration (Mallick and Schanze 2020 ).

One of the other key issues reviewed in this study is that the literature to date fails to build an understanding of the impacts of climate migration on both the origin (source regions) and destination of the climate migrants. There are very few studies such as Comstock and Cook ( 2018 ), Maurel and Tuccio ( 2016 ), Pryce and Chen ( 2011 ), Rahaman et al. ( 2018 ), Rice et al. ( 2015 ), and Schwan and Yu ( 2017 ) that investigate different aspects of socio-economic impacts (housing, health, social, economic, etc.) of climate migration in the destination region, and this presents a clear gap in knowledge that requires further study. Also, no current research has been identified during the review that focused on the environmental impacts of climate migration.

In addition, this review identifies that there was less attention paid to the impacts of climate migration on host communities compared to displaced populations in their new locations. Given that migration will continue to increase globally, there is likely to be a growing need to understand the range of potential impacts on host communities. Although some countries and regions are developing policies to manage internal migration, there are no formal protection policies for cross-border climate migration (Nishimura 2015 ; OHCHR 2018 ; Olsson 2015 ; Zaman 2021 ). Therefore, policy arrangements for managing the needs of climate displaced people in their new communities need to be developed to account for issues related to impacts, livelihoods, community cohesion, and cultural diversity and values. Future research should address the significant gap in understanding the livelihoods of climate migrants in their cross border or international destination. More specifically, in developed countries where the employment sector is more formalized, there is less room for informal economic practices that are common in developing contexts. More formal employment arrangements make it challenging for migrants to establish new livelihoods, alongside other challenges such as language barriers, and other financial, social, cultural and well-being issues.

Limitations and future research scope

Limitations of this study.

There are some limitations to this systematic review; firstly, this review used ProQuest as the sole database for the analysis, and future work could extend the scope to include other major databases. Secondly, this study only considered English language literature, and there are likely to be significant publications in other languages relating to climate migration that were not included in this analysis. Thirdly, looking at pre-1990 or post-2019 literature could add more exciting findings to the search list, which would provide more informative literature. Finally, the outputs of this review are limited to the nature of the search terms, and thus, if other words or texts such as climate-induced relocation or mobility were used, it might extend the range of the review.

Toward a research agenda for climate migration

This review has highlighted several exciting future research opportunities that will build on the strong foundation of work over the past decades in the field of climate migration studies. These include the following research themes; (i) a richer understanding of the full range of impacts (such as social, economic, environmental, and cultural) of climate migration on host communities; (ii) in-depth analysis of the livelihoods of climate-induced migrants in their new destination; (iii) evidence-based research on internal and international climate migration with their sources; (iv) long-term migration policy development at national, regional, or international levels considering both climate migrants and host communities; (v) scope and application of geographic information systems and remote sensing in this area of research, and (vi) developing sustainable livelihood frameworks for climate migrants. The authors believe that academic contributions to these research themes will drive climate migration challenges toward long-term solutions, particularly in those countries that are going to be hosting increasing numbers of climate migrants in future.

This study aimed to understand the past three decades of academic endeavor on climate migration and to identify the gaps in the existing literature in order to inform a research agenda for future research. Climate change, climate-induced migration, and climate migrants are now considered significant global challenges. Climate migrants are identified as a vulnerable group, and a consideration of issues for this group is essential in addressing the goals of the SDGs and SFDRRR. There is a growing body of knowledge that reflects the global relevance of climate migration as a major current and future challenge (Boncour and Burson 2009 ). Addressing the issues and challenges of this form of migration will improve the survival and certain resettlement rights of climate migrants (Miller 2017 ). Therefore, this review contributes a research agenda for future climate migration studies. This study has revealed a critical need to establish a universally agreed definition of ‘climate-induced migrants’ and ‘climate-induced migration,’ which remains unclear to date. Lack of clarity only acts to reduce the visibility of issues related to climate-induced migration. In addition, there is a crucial need to improve the evidence base for climate-induced migration by improving current global datasets, to inform local, regional, and global policy development. Policies need to be future-looking in preparation for a rapid and significant increase in climate-related migration across the globe, within and across national borders. For instance, it is important for receiving countries to anticipate an upsurge in migration by developing appropriate policies to support new migrants, particularly regarding visa and immigration arrangements. Addressing current gaps in knowledge will lead to improved pathways to manage this global migration challenge, which is now a critical need if we are to achieve a sustainable future in a climate-challenged world.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abel G, Bijak J, Findlay A, Mccollum D, Winiowski A (2013) Forecasting environmental migration to the United Kingdom: an exploration using Bayesian models. Popul Environ 35(2):183–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-013-0186-8

Article Google Scholar

Apap J (2019) The concept of ‘climate refugee’: towards a possible definition. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/621893/EPRS_BRI(2018)621893_EN.pdf . Accessed 26 Aug 2021

Baird R, Migiro K, Nutt D, Kwatra A, Wilson S, Melby J, Pendleton A, Rodgers M, Davison J (2007) Human tide: the real migration crisis. https://www.christianaid.org.uk/sites/default/files/2017-08/human-tide-the-real-migration-crisis-may-2007.pdf . Accessed 11 Sep 2021

Bedford R, Bedford C, Corcoran J, Didham R (2016) Population change and migration in Kiribati and Tuvalu, 2015–2050: Hypothetical scenarios in a context of climate change. N Z Popul Rev 42:103–134

Google Scholar

Berrang-Ford L, Ford J, Paterson J (2011) Are we adapting to climate change? Glob Environ Change 21(1):25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.09.012

Black R (2001) Environmental refugees: myth or reality? In: UNHCR: New Issues in Refugee Research (No. 34). https://www.unhcr.org/research/working/3ae6a0d00/environmental-refugees-myth-reality-richard-black.html . Accessed 04 Sep 2021

Black R, Adger WN, Arnell NW, Dercon S, Geddes A, Thomas D (2011) The effect of environmental change on human migration. Glob Environ Change 21(SUPPL. 1):S3–S11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.10.001

Boncour P, Burson B (2009) Climate change and migration in the South Pacific region: policy perspectives. Policy Q 5(4):13–20. https://doi.org/10.26686/pq.v5i4.4312

Bronen R (2008) Alaskan communities’ rights and resilience. Forced Migr Rev 31:30–32

Bronen R (2011) Climate-induced community relocations: creating an adaptive governance framework based in human rights doctrine. N Y Univ Rev Law Soc Change 35(2):357–407

Bronen R, Chapin FS (2013) Adaptive governance and institutional strategies for climate-induced community relocations in Alaska. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110(23):9320–9325. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1210508110

Brown O (2008) Migration and climate change. In: IOM Migration Research Series (No. 31). https://publications.iom.int/books/mrs-no-31-migration-and-climate-change . Accessed 11 Sep 2021

Campbell JR (2014) Climate-change migration in the Pacific. Contemp Pac 26(1):1–28. https://doi.org/10.1353/cp.2014.0023

Chapagain B, Gentle P (2015) Withdrawing from agrarian livelihoods: environmental migration in Nepal. J Mt Sci 12(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-014-3017-1

Chen J, Mueller V (2018) Coastal climate change, soil salinity and human migration in Bangladesh. Nat Clim Change 8(11):981–985. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0313-8

Comstock AR, Cook RA (2018) Climate change and migration along a Mississippian periphery: a fort ancient example. Am Antiq 83(1):91–108. https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2017.50

Connell J, Lutkehaus N (2017) Environmental refugees? A tale of two resettlement projects in coastal Papua New Guinea. Aust Geogr 48(1):79–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2016.1267603

Coughlin J (2018) The Figure of the “Climate Refugee” in Inger Elisabeth Hansen’s Å resirkulere lengselen: avrenning foregår (2015). Scand Can Stud 25:68–90

de Haas H (2011) The determinants of international migration: conceptualising policy, origin and destination effects. IMI Working Pap Ser 32(2011):35

de Haas H (2021) A theory of migration: the aspirations-capabilities framework. Comp Migr Stud 9(1):1–35. https://doi.org/10.1186/S40878-020-00210-4

Dorent N (2011) Transitory cities: emergency architecture and the challenge of climate change. Development 54(3):345–351. https://doi.org/10.1057/dev.2011.60

Doyle EEH, Johnston DM, Smith R, Paton D (2019) Communicating model uncertainty for natural hazards: a qualitative systematic thematic review. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 33:449–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.10.023

Fussell E, Hunter LM, Gray CL (2014) Measuring the environmental dimensions of human migration: the demographer’s toolkit. Glob Environ Change 28(1):182–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GLOENVCHA.2014.07.001

Gemenne F (2015) One good reason to speak of “climate refugees.” Forced Migr Rev 49:70–71

Hamza M, Koch I, Plewa M (2017) Disaster-induced displacement in the Caribbean and the Pacific. Forced Migr Rev 56:62–64

Held D (2016) Climate change, migration and the cosmopolitan dilemma. Global Pol 7(2):237–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12309

Hingley R (2017) “Climate refugees”: an oceanic perspective. Asia Pac Policy Stud 4(1):158–165. https://doi.org/10.1002/app5.163

Huq ME, Sarker MNI, Prasad R, Hossain MA, Rahman MM, Al-Dughairi AA (2021) Resilience for disaster management: opportunities and challenges. In: Alam GMM, Erdiaw-Kwasie MO, Nagy GJ, Filho WL (eds) Climate vulnerability and resilience in the global south : human adaptations for sustainable futures, 1st edn. Springer, Cham, pp 425–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77259-8_22

Chapter Google Scholar

IDMC (2017) Global Disaster Displacement Risk: A Baseline for Future Work. https://www.internal-displacement.org/publications/global-disaster-displacement-risk-a-baseline-for-future-work . Accessed 09 Sep 2021

IDMC (2019) Disaster displacement: a global review 2008–2018. https://environmentalmigration.iom.int/disaster-displacement-global-review-2008-2018 . Accessed 08 Sep 2021

IDMC (2021a) GRID 2021a: Internal displacement in a changing climate. Global Report on Internal Displacement, Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. https://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2021/ . Accessed 14 June 2021

IDMC (2021b) IDMC Query Tool—Disaster. Global Internal Displacement Database. https://www.internal-displacement.org/database/displacement-data . Accessed 09 Dec 2021

IOM (2021) Environmental Migration: Recent Trends. Migration Data Portal, International Organization for Migration. https://migrationdataportal.org/themes/environmental_migration_and_statistics . Accessed 31 Aug 2021

Ionesco D, Mokhnacheva D, Gemenne F (2017) The atlas of environmental migration, 1st edn. Routledge, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315777313

Book Google Scholar

IPCC (1990) IPCC First Assessment Report Overview. https://www.ipcc.ch/assessment-report/ar1/ . Accessed 10 Sep 2021

Islam MM, Sallu S, Hubacek K, Paavola J (2014) Migrating to tackle climate variability and change? Insights from coastal fishing communities in Bangladesh. Clim Change 124:733–746. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1135-y

Jacobson C, Crevello S, Chea C, Jarihani B (2019) When is migration a maladaptive response to climate change? Reg Environ Change 19(1):101–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-018-1387-6

Kälin W, Cantor D (2017) The RCM Guide: a novel protection tool for cross-border disaster-induced displacement in the Americas. Forced Migr Rev 56:58–61

Kang MJ (2013) From original homeland to “permanent housing” and back: the post-disaster exodus and reconstruction of south Taiwan’s indigenous communities. Soc Sci Dir 2(4):85–105. https://doi.org/10.7563/SSD_02_04_08

King D, Bird D, Haynes K, Boon H, Cottrell A, Millar J, Okada T, Box P, Keogh D, Thomas M (2014) Voluntary relocation as an adaptation strategy to extreme weather events. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 8:83–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2014.02.006

Kniveton DR, Smith CD, Black R (2012) Emerging migration flows in a changing climate in dryland Africa. Nat Clim Change. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1447

Laczko F, Aghazarm C (2009) Introduction and overview: enhancing the knowledge base. In: Laczko F, Aghazarm C (eds) Migration, environment and climate change: assessing the evidence. International Organization for Migration, Le Grand-Saconnex, pp 7–40

Locke JT (2009) Climate change-induced migration in the Pacific Region: sudden crisis and long-term developments. Geogr J 175(3):171–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4959.2009.00317.x

Mallett R, Hagen-Zanker J, Slater R, Duvendack M (2012) The benefits and challenges of using systematic reviews in international development research. J Dev Eff 4(3):445–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2012.711342

Mallick B, Schanze J (2020) Trapped or voluntary? Non-migration despite climate risks. Sustainability 12(11):1–6. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114718

Mallick B, Sultana Z (2017) Livelihood after relocation-evidences of Guchchagram project in Bangladesh. Soc Sci 6(3):1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6030076

Marino E, Lazrus H (2015) Migration or forced displacement? The complex choices of climate change and disaster migrants in Shishmaref, Alaska and Nanumea, Tuvalu. Hum Organ 74(4):341–350. https://doi.org/10.17730/0018-7259-74.4.341

Maurel M, Tuccio M (2016) Climate instability, urbanisation and international migration. J Dev Stud 52(5):735–752. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2015.1121240

Mayer B (2013) Environmental migration in the Asia-Pacific region: could we hang out sometime? Asian J Int Law 3(1):101–135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S204425131200029X

Mcleman R (2019) International migration and climate adaptation in an era of hardening borders. Nat Clim Change 9(12):911–918. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0634-2

McLeman RA (2014) Climate and human migration: past experiences, future challenges. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139136938

McLeman RA, Hunter LM (2010) Migration in the context of vulnerability and adaptation to climate change: insights from analogues. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Change 1(3):450–461. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.51

Milán-García J, Caparrós-Martínez JL, Rueda-López N, de Pablo Valenciano J (2021) Climate change-induced migration: a bibliometric review. Glob Health 17(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12992-021-00722-3

Miller DS (2017) Climate refugees and the human cost of global climate change. Environ Justice 10(4):89–92. https://doi.org/10.1089/env.2017.29027.dm

Myers N (2002) Environmental refugees: a growing phenomenon of the 21st century. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 357(1420):609–613. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2001.0953

Nagra S (2017) The Oslo principles and climate change displacement: missed opportunity or misplaced expectations? Carbon Clim Law Rev CCLR 11(2):120–135. https://doi.org/10.21552/cclr/2017/2/8

Nawrotzki RJ, Runfola DM, Hunter LM, Riosmena F (2016a) Domestic and International Climate Migration from Rural Mexico. Hum Ecol 44(6):687–699. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-016-9859-0

Nawrotzki RJ, Schlak AM, Kugler TA (2016b) Climate, migration, and the local food security context: introducing Terra Populus. Popul Environ 38(2):164–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-016-0260-0

Nishimura L (2015) ‘Climate change migrants’: impediments to a protection framework and the need to incorporate migration into climate change adaptation strategies. Int J Refug Law 27(1):107–134. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijrl/eev002

Obokata R, Veronis L, McLeman R (2014) Empirical research on international environmental migration: a systematic review. Popul Environ 36(1):111–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-014-0210-7

OHCHR (2018) The slow onset effects of climate change and human rights protection for cross-border migrants. https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Migration/OHCHR_slow_onset_of_Climate_Change_EN.pdf . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Olsson L (2015) Environmental migrants in international law: An assessment of protection gaps and solutions. Environmental Migration Portal: Climate Change, Displacement. https://environmentalmigration.iom.int/environmental-migrants-international-law-assessment-protection-gaps-and-solutions . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Omeziri E, Gore C (2014) Temporary measures: Canadian refugee policy and environmental migration. Refuge 29(2):43–53. https://doi.org/10.25071/1920-7336.38166

Parrish R, Colbourn T, Lauriola P, Leonardi G, Hajat S, Zeka A (2020) A critical analysis of the drivers of human migration patterns in the presence of climate change: a new conceptual model. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(17):1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176036

Peel MC, Finlayson BL, Mcmahon TA (2007) Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 11(5):1633–1644. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007

Perkiss S, Moerman L (2018) A dispute in the making. Account Audit Account J 31(1):166–192. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-06-2016-2582

Perumal N (2018) The place where I live is where I belong: community perspectives on climate change and climate-related migration in the Pacific island nation of Vanuatu. Island Stud J 13(1):45–64. https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.50

Petticrew M, Robert H (2006) Systematic reviews in the social sciences: a practical guide. Blackwell Publishing, Hoboken. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470754887

Piguet E, Pécoud A, de Guchteneire P (2011) Migration and climate change: an overview. Refug Surv Q 30(3):1–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/rsq/hdr006

Piguet E, Kaenzig R, Guélat J (2018) The uneven geography of research on “environmental migration.” Popul Environ 39(4):357–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-018-0296-4

Poncelet A, Gemenne F, Martiniello M, Bousetta H (2010) A country made for disasters: environmental vulnerability and forced migration in Bangladesh. In: Afifi T, Jäger J (eds) Environment, forced migration and social vulnerability. Springer, Berlin, pp 211–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-12416-7

Prasain S (2018) Climate change adaptation measure on agricultural communities of Dhye in Upper Mustang, Nepal. Clim Change 148:279–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2187-1

Pryce G, Chen Y (2011) Flood risk and the consequences for housing of a changing climate: an international perspective. Risk Manage 13(4):228–246. https://doi.org/10.1057/rm.2011.13

Rahaman MA, Rahman MM, Bahauddin KM, Khan S, Hassan S (2018) Health disorder of climate migrants in Khulna City: an urban slum perspective. Int Migr. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12460

Rahman MS, Gain A (2020) Adaptation to river bank erosion induced displacement in Koyra Upazila of Bangladesh. Prog Disaster Sci 5:1000552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2019.100055

Rice JL, Burke BJ, Heynen N (2015) Knowing climate change, embodying climate praxis: experiential knowledge in Southern Appalachi. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 105(2):253–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2014.985628

Scheffran J (2008) Climate change and security. Bull Atom Sci 64(2):19–25. https://doi.org/10.2968/064002007

Schwan S, Yu X (2017) Social protection as a strategy to address climate-induced migration. Int J Clim Change Strateg Manage 10(1):43–64. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-01-2017-0019

Smith K, Smith K (2013) Environmental hazards: assessing risk and reducing disaster, 6th edn. Routledge, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203805305

Tanyag M (2018) Resilience, female altruism, and bodily autonomy: disaster-induced displacement in Post-Haiyan Philippines. Signs J Women Cult Soc 43(3):563–585. https://doi.org/10.1086/695318

The World Bank (2018) Groundswell: preparing for internal climate migration. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/infographic/2018/03/19/groundswell---preparing-for-internal-climate-migration . Accessed 29 June 2021

Warner K, Ehrhart C, de Sherbinin A, Adamo S, Chai-Onn T (2009) In search of shelter: mapping the effects of climate change on human migration and displacement. https://www.care.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/CC-2009-CARE_In_Search_of_Shelter.pdf . Accessed 11 Sept 2021

Weinthal E, Zawahri N, Sowers J (2015) Securitizing water, climate, and migration in Israel, Jordan, and Syria. Int Environ Agreem Polit Law Econ 15(3):293–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-015-9279-4

Werz M, Hoffman M (2016) Europe’s twenty-first century challenge: climate change, migration and security. Eur View 15(1):145–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12290-016-0385-7

White G (2012) Climate change and migration: security and borders in a warming world. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199794829.001.0001

Wiegel H (2017) Refugees of rising seas. Science 357(6346):41. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan5667

Wilkinson E, Kirbyshire A, Mayhew L, Batra P, Milan A (2016) Climate-induced migration and displacement: closing the policy gap. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/10996.pdf . Accessed 12 March 2021

Ye Y, Fang X, Khan MAU (2012) Migration and reclamation in Northeast China in response to climatic disasters in North China over the past 300 years. Reg Environ Change 12(1):193–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-011-0245-6

Zaman ST (2021) Legal protection for the cross-border climate-induced population movement in south asia: exploring a durable solution. J Environ Law Litig 36:187–235

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Douglas Hill, Dr Ashraful Alam and Dr Bishawjit Mallick for their feedback on the initial draft of this article.

This research has been supported by a University of Otago Doctoral Scholarship. Open Access funding is enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Sustainability, School of Geography, University of Otago, Dunedin, 9016, New Zealand

Rajan Chandra Ghosh & Caroline Orchiston

Department of Emergency Management, Faculty of Environmental Science and Disaster Management, Patuakhali Science and Technology University, Patuakhali, 8602, Bangladesh

Rajan Chandra Ghosh

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Both authors have contributed to the study conception and design. RCG performed the literature search, collected and analyzed the data, and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. CO critically reviewed the manuscript. Both authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rajan Chandra Ghosh .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors have no financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Ghosh, R.C., Orchiston, C. A systematic review of climate migration research: gaps in existing literature. SN Soc Sci 2 , 47 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00341-8

Download citation

Received : 23 September 2021

Accepted : 28 March 2022

Published : 16 April 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00341-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Climate-induced migration

- Climate-induced migrants

- Livelihoods

- Systematic review

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

International Student Migration - An Annotated Review of the Literature

2016, International Student Migration

This article offers a foundation for gaining a comprehensive understanding of ISM and identifying research gaps. It proposes classifying the scientific literature according to six main questions: (1) How to theorize ISM? (2) What are the directions and patterns of student flows? (3) What are the students’ reasons for moving, and what are their subsequent experiences abroad? 4) What are the regulations, policies, and strategies of supranational bodies, national governments, and universities regarding ISM? (5) What are the outcomes and effects of ISM? (6) What are the students’ plans for future mobility, and what are their experiences upon return?

Related Papers

Population Space and Place

Parvati Raghuram

Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences

Oxford Bibliographies Online Datasets

Yvonne Riaño

Suzanne E Beech

Greater interconnectivity has led to a growth in the number of students enrolling at universities outside of their home country. This chapter offers a review of the changing policies that have led to greater competition between both countries and universities for international students and the development of education as a key export industry in many industrialized societies. It analyses the complex and multifaceted issues that play a part in student decision making. In particular it assesses how greater consumerism and the marketization of higher education has led to an interest in these decision making processes and led to a dramatic expansion in the literature detailing student mobility. This chapter systematically analyses this information, detailing how students choose an international education on the basis of economically focused factors (such as the improved job prospects that potentially come with international mobility) and how these go hand-in-hand with the sociocultural aspects of overseas study (such as the improved intercultural communication skills), to offer an overview of the complexity of overseas students' decision making practices. To conclude it suggests some key areas for consideration in emerging research and how this is advancing our current understandings of student mobility further – such as work by Carlson (2013), who suggested that a greater understanding of mobility as 'processional', rather than at a single point in time was critical as we move forward.

Journal of Studies in International Education

Among the increasing number of academic publications in the field of higher education, studies focusing on internationalization of higher education are on the exponential phase in the last couple of decades. In these efforts, the research on international student mobility (ISM) has been a priority. This current review research uses science mapping tools to examine Web of Science (WoS)–indexed journal publications focusing on ISM. The purpose of the review is to demonstrate the development of ISM research in the last three decades. The findings, revealed from an examination of 2,064 publications, suggest that ISM research has significantly expanded since 2005. Findings also reveal crucial information regarding the authors’ country of origin as well as country collaborations and the most influential scholars in the field by demonstrating networks around the world. Topical foci analysis is also included in the study to show current patterns in ISM research. Discussions and suggestions ...

Rahul Choudaha

This article analyses the changes in international student mobility from the lens of three overlapping waves spread over seven years between 1999 and 2020. Here a wave is defined by the key events and trends impacting international student mobility within temporal periods. Wave I was shaped by the terrorist attacks of 2001 and enrolment of international students at institutions seeking to build research excellence. Wave II was shaped by the global financial recession which triggered financial motivations for recruiting international students. Wave III is being shaped by the slowdown in the Chinese economy, UK’s referendum to leave the European Union and American Presidential elections. The trends for Wave III show increasing competition among new and traditional destinations to attract international students. The underlying drivers and characteristics of the three waves suggest that institutions are under increasing financial and competitive pressure to attract and retain international students. Going forward, institutions must innovate not only to grow international student enrolment but also balance it with corresponding support services that advance student success including expectations of career and employability outcomes.

Journal of Higher Education Policy And Leadership Studies

Neeta Inamdar

Findlay, A., Stam, A., King, R. and Ruiz-Gelices, E. (2005) 'International opportunities: searching for the meaning of student migration.' Geographica Helvetica, 60(3): 192-200.

Enric Ruiz-Gelices

This paper explores aspects of the geography of international Student migration. By listening to the voices of British students we make a methodological contribution in terms of extending understanding of the intentions and values of Student migrants as developed over their life course. On the one hand, students stressed the social and cultural embeddedness of their actions, while on the other hand interviews with university staff and mobility managers pointed to the existence of other social structures that shape the networks of mobility that are available to students. Policy makers seeking to re-shape the geography of international Student mobility need to address the deeper socio-cultural forces that selectively inhibit movement although European integration processes have long paved the way for international living and work experience. --- La présente contribution aborde différentes facettes d'un mouvement peu étudie, la migration internationale estudiantine. En donnant la parole à des étudiants britanniques, I'enquête menée cherche à élargir la connaissance des motivations et échelles de valeurs développées par les étudiants migrants au cours de leur trajectoire. Les étudiants ont démontré que leurs actions s'inscrivent dans leurs valeurs sociales et culturelles. Quant aux interviews conduites auprès d'enseignants et co-ordinateurs de mobilité, elles ont permis de relever d'autres structures sociales qui influencent le comportement des étudiants. Les personnalités politiques qui entendent promouvoir l'expérience internationale de leurs élites formatrices en matière d'études et professionnelle, doivent prendre notamment en considération les influences socio-culturelles qui réduisent la mobilité, des influences qui persistent encore, en dépit du fait que les processus européens d'intégration ne cessent de faciliter les échanges internationaux. --- Dieser Artikel setzt sich mit verschiedenen Gesichtspunkten der internationalen Studierendenmigration, einer noch wenig untersuchten Bewegung, auseinander. Es soll ein methodischer Beitrag dazu geleistet werden, die Erwartungen und Wertvorstellungen britischer Studierender herauszuarbeiten, wie sie sich im Laufe ihres Lebens entwickeln. Die Studierenden zeigen einerseits, dass ihr Verhalten ihren sozialen und kulturellen Kontext widerspiegelt. Andererseits ergeben Interviews mit Dozierenden und Austausch-Koordinatoren an Universitäten, dass andere soziale Strukturen und Einflüsse das Studierenden-Verhalten bestimmen. Politiker, welche die internationale Studien- und Arbeitserfahrung ihrer Bildungselite fördern wollen, müssen gerade die soziokulturellen Einflüsse, welche die Mobilität reduzieren, berücksichtigen, Einflüsse, die noch bestehen, obwohl europäische Integrationsprozesse den internationalen Austausch laufend erleichtern.

A new environment of budgetary cuts and increasing competition is forcing many institutions to become strategic and deliberate in their recruitment efforts. Effective international recruitment practices are dependent more than ever on a deep understanding of student mobility patterns and decision-making processes. The purpose of this research is to provide an in-depth understanding of the trends and issues related to international student enrollment and to help institutional leaders and administrators make informed decisions and effectively set priorities.

Of late there has been considerable interest in understanding international student mobility, and this has tended to focus on the perspective of the students who take part in this mobility. However, international students are part of a considerable migration industry comprised of international student recruitment teams, international education agents and other institutions selling an education overseas (such as the British Council in a UK context) and as yet there is little research which analyses these relationships. This paper investigates a series of interviews with international office staff to examine the methods they use to recruit international students, and in particular the relationship that they have with international education agents who work with them on a commission basis. It focuses on recent changes to the UK visa system which have led to a decline in the numbers of Indian students choosing to study towards a UK higher education. However, it also reveals that some universities have managed to avoid this trend. This paper investigates why this is the case, demonstrating that there is a need to think about the intersections between migration industries, visa regulations and international student mobility.

RELATED PAPERS

Gastroenterology

Kathryn Peterson

JURNAL EKONOMI DAN KEBIJAKAN PEMBANGUNAN

Wiwiek Rindayati

Sam Lanfranco

Romanian Statistical Review Supplement

Georgiana Nita

Jurnal Teknik Sipil

Partogi Simatupang

Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology

Conleth Feighery

Andrea Caprara

Physical Review B

Hyun-Tak Kim

Revista M. Estudos sobre a morte, os mortos e o morrer

Karen Scavacini

مجلة کلیة السیاحة والفنادق. جامعة المنصورة

Mohamed AbdElFattah Zohry

Takzim : Jurnal Pengabdian Masyarakat

riawani elyta

JURNAL GEOLOGI KELAUTAN

Nazar Nurdin

Acta Palaeontologica Polonica

Graciela Piñeiro

Extending the Standard Model in Hyper-Dimensional Mechanics

En La Calle Revista Sobre Situaciones De Riesgo Social

Noelia Martinez

Urology Case Reports

Journal of Leukocyte Biology

Elizabeth Soilleux

European Journal of Phycology

Böddi Béla

Silvana Mendes Lima

Studies in Business and Economics

Ilie Rotariu

Beth Staples

Revista Portuguesa de Musicologia

Gerhard Doderer

Biochemistry

Nguyên Bảo Lê

The British journal of nutrition

Christophe Dupont

Journal of KIISE:Computer Systems and Theory

Jung-Heum Park

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

20 Jul 2020

The Future of Migration to Europe: A systematic review of the literature on migration scenarios and forecasts

Effective migration management requires some degree of anticipation of the magnitude and nature of future flows. In response to these needs, two types of approaches have emerged in the literature in recent years: (a) migration forecasts, which provide quantitative estimates of future migration, and (b) migration scenarios, which develop different storylines and thereby emphasize flexibility of thought on future migration. This report presents the results of a systematic literature review of migration forecasts and scenarios. It presents key definitions, methods and common lessons from the available evidence in this field. Over 200 relevant publications were screened to retrieve not only the results of the studies, but also information about the context in which the studies were produced (i.e. research metadata). This comprehensive overview will be of interest to both scientists and practitioners who wish to navigate this growing field.

- Acknowledgements

- List of tables and figures

- Executive summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Definitions

- 3. Methodology

- 4.1. Why now?

- 4.2. Who develops migration scenarios?

- 4.3. What are the time horizons of migration scenarios?

- 4.4. What types of migration scenarios exist?

- 4.5. Migration drivers in scenarios and forecasts

- 4.6.1. International cooperation and European Union integration

- 4.6.2. Economic development

- 4.6.3. Environment

- 4.6.4. Social development

- 4.6.5. Public opinion

- 4.6.6. Migration policy

- 4.7.1. Participatory, discursive approaches to migration scenarios

- 4.7.2. Adaptation of existing scenarios

- 4.7.3. Large-scale, mixed studies

- 4.7.4. The Delphi method

- 4.7.5. Other approaches

- 5. Interim conclusion: Migration scenarios

- 6.1. Who produces migration forecasts?

- 6.2. Where are migration forecasts published?

- 6.3. Which data sources are used?

- 6.4. What types of migration are forecast?

- 6.5. Migration drivers in forecasts

- 6.6.1. Econometric models

- 6.6.2. Migration intention surveys

- 6.6.3. Argument-based forecasts

- 6.6.4. Time series extrapolations

- 6.7. How accurate are migration forecasts?

- 7. Conclusions

- Annex I. Methodology of the systematic literature review

- Annex II. List of reviewed migration scenario publications

- Annex III: List of reviewed migration forecast publications

- Open access

- Published: 25 April 2024

A scoping review of academic and grey literature on migrant health research conducted in Scotland

- G. Petrie 1 ,

- K. Angus 2 &

- R. O’Donnell 2

BMC Public Health volume 24 , Article number: 1156 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

73 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Migration to Scotland has increased since 2002 with an increase in European residents and participation in the Asylum dispersal scheme. Scotland has become more ethnically diverse, and 10% of the current population were born abroad. Migration and ethnicity are determinants of health, and information on the health status of migrants to Scotland and their access to and barriers to care facilitates the planning and delivery of equitable health services. This study aimed to scope existing peer-reviewed research and grey literature to identify gaps in evidence regarding the health of migrants in Scotland.

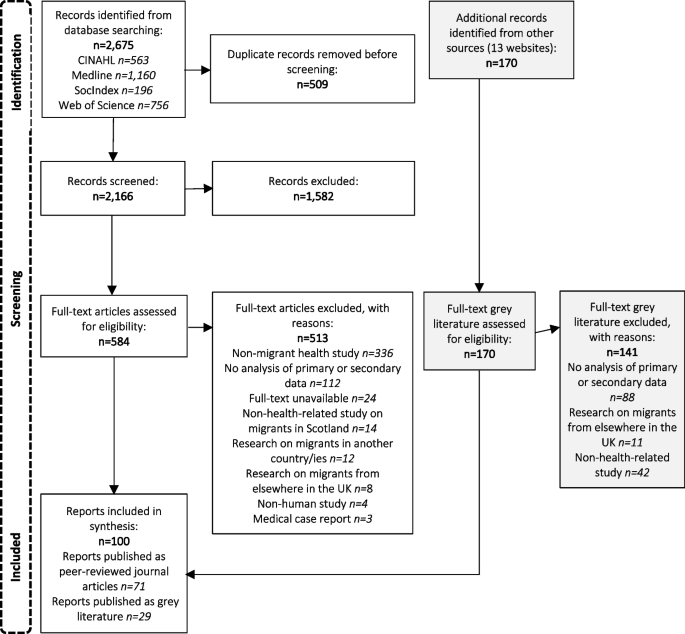

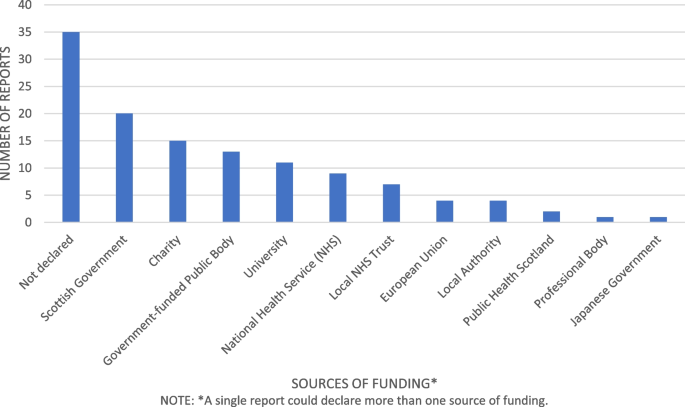

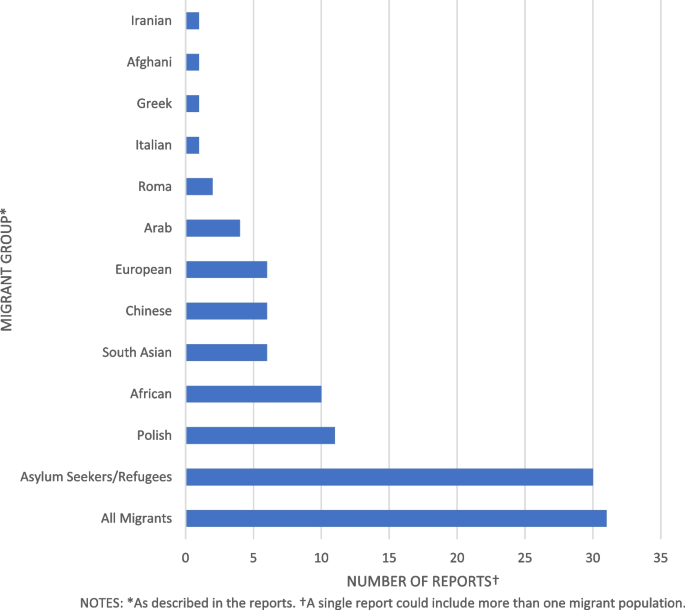

A scoping review on the health of migrants in Scotland was carried out for dates January 2002 to March 2023, inclusive of peer-reviewed journals and grey literature. CINAHL/ Web of Science/SocIndex and Medline databases were systematically searched along with government and third-sector websites. The searches identified 2166 journal articles and 170 grey literature documents for screening. Included articles were categorised according to the World Health Organisation’s 2016 Strategy and Action Plan for Refugee and Migrant Health in the European region. This approach builds on a previously published literature review on Migrant Health in the Republic of Ireland.

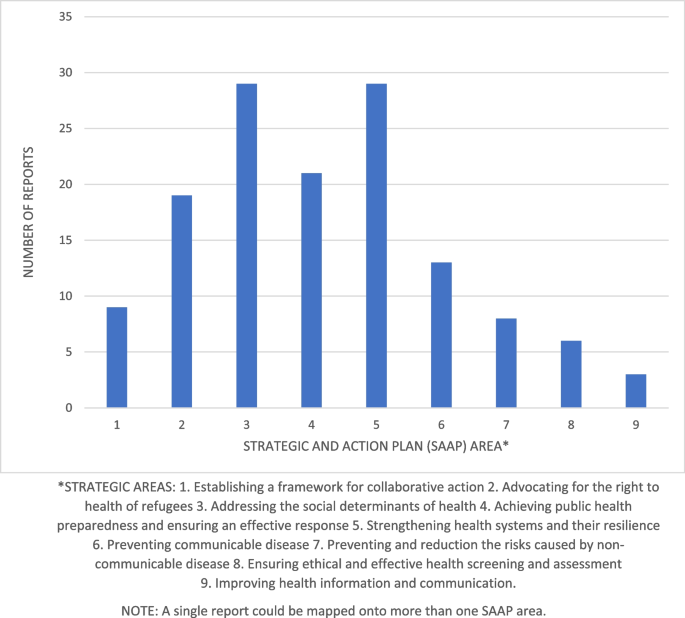

Seventy-one peer reviewed journal articles and 29 grey literature documents were included in the review. 66% were carried out from 2013 onwards and the majority focused on asylum seekers or unspecified migrant groups. Most research identified was on the World Health Organisation’s strategic areas of right to health of refugees, social determinants of health and public health planning and strengthening health systems. There were fewer studies on the strategic areas of frameworks for collaborative action, preventing communicable disease, preventing non-communicable disease, health screening and assessment and improving health information and communication.

While research on migrant health in Scotland has increased in recent years significant gaps remain. Future priorities should include studies of undocumented migrants, migrant workers, and additional research is required on the issue of improving health information and communication.

Peer Review reports

The term migrant is defined by the International Organisation for Migration as “ a person who moves away from his or her place of usual residence, whether within a country or across an international border, temporarily or permanently, and for a variety of reasons. The term includes several well-defined legal categories of people, including migrant workers; persons whose particular types of movements are legally-defined, such as smuggled migrants; as well as those whose status are not specifically defined under international law, such as international students.” [ 1 ] Internationally there are an estimated 281 million migrants – 3.6% of the world population, including 26.4 million refugees and 4.1 million asylum seekers – the highest number ever recorded [ 2 ]. The UN Refugee Society defines the term refugee as “ someone who has been forced to flee his or her country because of persecution, war or violence…most likely, they cannot return home or are afraid to do so .” The term asylum-seeker is defined as “someone whose request for sanctuary has yet to be processed.” [ 3 ].