A hierarchy of evidence for assessing qualitative health research

Affiliation.

- 1 Mother and Child Health Research, La Trobe University, Carlton, VIC, Australia.

- PMID: 17161753

- DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.014

Objective: The objective of this study is to outline explicit criteria for assessing the contribution of qualitative empirical studies in health and medicine, leading to a hierarchy of evidence specific to qualitative methods.

Study design and setting: This paper arose from a series of critical appraisal exercises based on recent qualitative research studies in the health literature. We focused on the central methodological procedures of qualitative method (defining a research framework, sampling and data collection, data analysis, and drawing research conclusions) to devise a hierarchy of qualitative research designs, reflecting the reliability of study conclusions for decisions made in health practice and policy.

Results: We describe four levels of a qualitative hierarchy of evidence-for-practice. The least likely studies to produce good evidence-for-practice are single case studies, followed by descriptive studies that may provide helpful lists of quotations but do not offer detailed analysis. More weight is given to conceptual studies that analyze all data according to conceptual themes but may be limited by a lack of diversity in the sample. Generalizable studies using conceptual frameworks to derive an appropriately diversified sample with analysis accounting for all data are considered to provide the best evidence-for-practice. Explicit criteria and illustrative examples are described for each level.

Conclusion: A hierarchy of evidence-for-practice specific to qualitative methods provides a useful guide for the critical appraisal of papers using these methods and for defining the strength of evidence as a basis for decision making and policy generation.

Publication types

- Evidence-Based Medicine / methods*

- Evidence-Based Medicine / standards

- Health Services Research / methods*

- Health Services Research / standards

- Qualitative Research*

- Quality Indicators, Health Care

- Research Design

A hierarchy of evidence for assessing qualitative health research

- Population and Public Health

- UWA Medical School

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review

This output contributes to the following UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Access to Document

- 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.014

Other files and links

- http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp= 84947648720&partnerID=8YFLogxK

Fingerprint

- Qualitative Method Psychology 100%

- Critical Appraisal Nursing and Health Professions 100%

- Qualitative Research Psychology 66%

- Case Study Psychology 33%

- Study Design Psychology 33%

- Conceptual Framework Psychology 33%

- Decision Making Psychology 33%

- Conceptual Study Psychology 33%

T1 - A hierarchy of evidence for assessing qualitative health research

AU - Daly, J.

AU - Willis, K.

AU - Small, R.

AU - Green, J.

AU - Welsh, N.

AU - Kealy, M.

AU - Hughes, Emma

N2 - Objective:The objective of this study is to outline explicit criteria for assessing the contribution of qualitative empirical studies in health and medicine, leading to a hierarchy of evidence specific to qualitative methods. Study Design and Setting: This paper arose from a series of critical appraisal exercises based on recent qualitative research studies in the health literature. We focused on the central methodological procedures of qualitative method (defining a research framework, sampling and data collection, data analysis, and drawing research conclusions) to devise a hierarchy of qualitative research designs, reflecting the reliability of study conclusions for decisions made in health practice and policy.Results:We describe four levels of a qualitative hierarchy of evidence-for-practice. The least likely studies to produce good evidence-for-practice are single case studies, followed by descriptive studies that may provide helpful lists of quotations but do not offer detailed analysis. More weight is given to conceptual studies that analyze all data according to conceptual themes but may be limited by a lack of diversity in the sample. Generalizable studies using conceptual frameworks to derive an appropriately diversified sample with analysis accounting for all data are considered to provide the best evidence-for-practice. Explicit criteria and illustrative examples are described for each level. Conclusion: A hierarchy of evidence-for-practice specific to qualitative methods provides a useful guide for the critical appraisal of papers using these methods and for defining the strength of evidence as a basis for decision making and policy generation.

AB - Objective:The objective of this study is to outline explicit criteria for assessing the contribution of qualitative empirical studies in health and medicine, leading to a hierarchy of evidence specific to qualitative methods. Study Design and Setting: This paper arose from a series of critical appraisal exercises based on recent qualitative research studies in the health literature. We focused on the central methodological procedures of qualitative method (defining a research framework, sampling and data collection, data analysis, and drawing research conclusions) to devise a hierarchy of qualitative research designs, reflecting the reliability of study conclusions for decisions made in health practice and policy.Results:We describe four levels of a qualitative hierarchy of evidence-for-practice. The least likely studies to produce good evidence-for-practice are single case studies, followed by descriptive studies that may provide helpful lists of quotations but do not offer detailed analysis. More weight is given to conceptual studies that analyze all data according to conceptual themes but may be limited by a lack of diversity in the sample. Generalizable studies using conceptual frameworks to derive an appropriately diversified sample with analysis accounting for all data are considered to provide the best evidence-for-practice. Explicit criteria and illustrative examples are described for each level. Conclusion: A hierarchy of evidence-for-practice specific to qualitative methods provides a useful guide for the critical appraisal of papers using these methods and for defining the strength of evidence as a basis for decision making and policy generation.

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp= 84947648720&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.014

DO - 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.014

M3 - Article

C2 - 17161753

SN - 0895-4356

JO - Journal of Clinical Epidemiology

JF - Journal of Clinical Epidemiology

- Advanced search

- Peer review

- Record : found

- Abstract : found

- Article : not found

A hierarchy of evidence for assessing qualitative health research.

Read this article at.

- open (via free pdf)

- Review article

- Invite someone to review

Abstract

Author and article information , comment on this article.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 21, Issue 4

- New evidence pyramid

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- M Hassan Murad ,

- Mouaz Alsawas ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5481-696X Fares Alahdab

- Rochester, Minnesota , USA

- Correspondence to : Dr M Hassan Murad, Evidence-based Practice Center, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN 55905, USA; murad.mohammad{at}mayo.edu

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmed-2016-110401

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

- EDUCATION & TRAINING (see Medical Education & Training)

- EPIDEMIOLOGY

- GENERAL MEDICINE (see Internal Medicine)

The first and earliest principle of evidence-based medicine indicated that a hierarchy of evidence exists. Not all evidence is the same. This principle became well known in the early 1990s as practising physicians learnt basic clinical epidemiology skills and started to appraise and apply evidence to their practice. Since evidence was described as a hierarchy, a compelling rationale for a pyramid was made. Evidence-based healthcare practitioners became familiar with this pyramid when reading the literature, applying evidence or teaching students.

Various versions of the evidence pyramid have been described, but all of them focused on showing weaker study designs in the bottom (basic science and case series), followed by case–control and cohort studies in the middle, then randomised controlled trials (RCTs), and at the very top, systematic reviews and meta-analysis. This description is intuitive and likely correct in many instances. The placement of systematic reviews at the top had undergone several alterations in interpretations, but was still thought of as an item in a hierarchy. 1 Most versions of the pyramid clearly represented a hierarchy of internal validity (risk of bias). Some versions incorporated external validity (applicability) in the pyramid by either placing N-1 trials above RCTs (because their results are most applicable to individual patients 2 ) or by separating internal and external validity. 3

Another version (the 6S pyramid) was also developed to describe the sources of evidence that can be used by evidence-based medicine (EBM) practitioners for answering foreground questions, showing a hierarchy ranging from studies, synopses, synthesis, synopses of synthesis, summaries and systems. 4 This hierarchy may imply some sort of increasing validity and applicability although its main purpose is to emphasise that the lower sources of evidence in the hierarchy are least preferred in practice because they require more expertise and time to identify, appraise and apply.

The traditional pyramid was deemed too simplistic at times, thus the importance of leaving room for argument and counterargument for the methodological merit of different designs has been emphasised. 5 Other barriers challenged the placement of systematic reviews and meta-analyses at the top of the pyramid. For instance, heterogeneity (clinical, methodological or statistical) is an inherent limitation of meta-analyses that can be minimised or explained but never eliminated. 6 The methodological intricacies and dilemmas of systematic reviews could potentially result in uncertainty and error. 7 One evaluation of 163 meta-analyses demonstrated that the estimation of treatment outcomes differed substantially depending on the analytical strategy being used. 7 Therefore, we suggest, in this perspective, two visual modifications to the pyramid to illustrate two contemporary methodological principles ( figure 1 ). We provide the rationale and an example for each modification.

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

The proposed new evidence-based medicine pyramid. (A) The traditional pyramid. (B) Revising the pyramid: (1) lines separating the study designs become wavy (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation), (2) systematic reviews are ‘chopped off’ the pyramid. (C) The revised pyramid: systematic reviews are a lens through which evidence is viewed (applied).

Rationale for modification 1

In the early 2000s, the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group developed a framework in which the certainty in evidence was based on numerous factors and not solely on study design which challenges the pyramid concept. 8 Study design alone appears to be insufficient on its own as a surrogate for risk of bias. Certain methodological limitations of a study, imprecision, inconsistency and indirectness, were factors independent from study design and can affect the quality of evidence derived from any study design. For example, a meta-analysis of RCTs evaluating intensive glycaemic control in non-critically ill hospitalised patients showed a non-significant reduction in mortality (relative risk of 0.95 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.25) 9 ). Allocation concealment and blinding were not adequate in most trials. The quality of this evidence is rated down due to the methodological imitations of the trials and imprecision (wide CI that includes substantial benefit and harm). Hence, despite the fact of having five RCTs, such evidence should not be rated high in any pyramid. The quality of evidence can also be rated up. For example, we are quite certain about the benefits of hip replacement in a patient with disabling hip osteoarthritis. Although not tested in RCTs, the quality of this evidence is rated up despite the study design (non-randomised observational studies). 10

Rationale for modification 2

Another challenge to the notion of having systematic reviews on the top of the evidence pyramid relates to the framework presented in the Journal of the American Medical Association User's Guide on systematic reviews and meta-analysis. The Guide presented a two-step approach in which the credibility of the process of a systematic review is evaluated first (comprehensive literature search, rigorous study selection process, etc). If the systematic review was deemed sufficiently credible, then a second step takes place in which we evaluate the certainty in evidence based on the GRADE approach. 11 In other words, a meta-analysis of well-conducted RCTs at low risk of bias cannot be equated with a meta-analysis of observational studies at higher risk of bias. For example, a meta-analysis of 112 surgical case series showed that in patients with thoracic aortic transection, the mortality rate was significantly lower in patients who underwent endovascular repair, followed by open repair and non-operative management (9%, 19% and 46%, respectively, p<0.01). Clearly, this meta-analysis should not be on top of the pyramid similar to a meta-analysis of RCTs. After all, the evidence remains consistent of non-randomised studies and likely subject to numerous confounders.

Therefore, the second modification to the pyramid is to remove systematic reviews from the top of the pyramid and use them as a lens through which other types of studies should be seen (ie, appraised and applied). The systematic review (the process of selecting the studies) and meta-analysis (the statistical aggregation that produces a single effect size) are tools to consume and apply the evidence by stakeholders.

Implications and limitations

Changing how systematic reviews and meta-analyses are perceived by stakeholders (patients, clinicians and stakeholders) has important implications. For example, the American Heart Association considers evidence derived from meta-analyses to have a level ‘A’ (ie, warrants the most confidence). Re-evaluation of evidence using GRADE shows that level ‘A’ evidence could have been high, moderate, low or of very low quality. 12 The quality of evidence drives the strength of recommendation, which is one of the last translational steps of research, most proximal to patient care.

One of the limitations of all ‘pyramids’ and depictions of evidence hierarchy relates to the underpinning of such schemas. The construct of internal validity may have varying definitions, or be understood differently among evidence consumers. A limitation of considering systematic review and meta-analyses as tools to consume evidence may undermine their role in new discovery (eg, identifying a new side effect that was not demonstrated in individual studies 13 ).

This pyramid can be also used as a teaching tool. EBM teachers can compare it to the existing pyramids to explain how certainty in the evidence (also called quality of evidence) is evaluated. It can be used to teach how evidence-based practitioners can appraise and apply systematic reviews in practice, and to demonstrate the evolution in EBM thinking and the modern understanding of certainty in evidence.

- Leibovici L

- Agoritsas T ,

- Vandvik P ,

- Neumann I , et al

- ↵ Resources for Evidence-Based Practice: The 6S Pyramid. Secondary Resources for Evidence-Based Practice: The 6S Pyramid Feb 18, 2016 4:58 PM. http://hsl.mcmaster.libguides.com/ebm

- Vandenbroucke JP

- Berlin JA ,

- Dechartres A ,

- Altman DG ,

- Trinquart L , et al

- Guyatt GH ,

- Vist GE , et al

- Coburn JA ,

- Coto-Yglesias F , et al

- Sultan S , et al

- Montori VM ,

- Ioannidis JP , et al

- Altayar O ,

- Bennett M , et al

- Nissen SE ,

Contributors MHM conceived the idea and drafted the manuscript. FA helped draft the manuscript and designed the new pyramid. MA and NA helped draft the manuscript.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Linked Articles

- Editorial Pyramids are guides not rules: the evolution of the evidence pyramid Terrence Shaneyfelt BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine 2016; 21 121-122 Published Online First: 12 Jul 2016. doi: 10.1136/ebmed-2016-110498

- Perspective EBHC pyramid 5.0 for accessing preappraised evidence and guidance Brian S Alper R Brian Haynes BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine 2016; 21 123-125 Published Online First: 20 Jun 2016. doi: 10.1136/ebmed-2016-110447

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Jump to navigation

Cochrane Methods Methodology Register

The Cochrane Methodology Register (CMR) is a bibliography of publications that report on methods used in the conduct of controlled trials. It includes journal articles, books, and conference proceedings, and the content is sourced from MEDLINE and hand searches. CMR contains studies of methods used in reviews and more general methodological studies that could be relevant to anyone preparing systematic reviews. CMR records contain the title of the article, information on where it was published (bibliographic details), and, in some cases, a summary of the article. They do not contain the full text of the article.

The CMR was produced by the Cochrane UK , until 31 st May 2012. There are currently no plans to reinstate the CMR and it is not receiving updates.* If you have any queries, please contact the Cochrane Community Service Team ( [email protected] ).

The Publishers, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, thanks Update Software for the continued use of their data formats in the Cochrane Methodology Register (CMR).

*Last update in January 2019.

Evidence-Based Practice in Health

- Introduction

- PICO Framework and the Question Statement

- Types of Clinical Question

- Hierarchy of Evidence

The Evidence Hierarchy: What is the "Best Evidence"?

Systematic reviews versus primary studies: what's best, systematic reviews and narrative reviews: what's the difference, filtered versus unfiltered information, the cochrane library.

- Selecting a Resource

- Searching PubMed

- Module 3: Appraise

- Module 4: Apply

- Module 5: Audit

- Reference Shelf

What is "the best available evidence"? The hierarchy of evidence is a core principal of Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) and attempts to address this question. The evidence higherarchy allows you to take a top-down approach to locating the best evidence whereby you first search for a recent well-conducted systematic review and if that is not available, then move down to the next level of evidence to answer your question.

EBP hierarchies rank study types based on the rigour (strength and precision) of their research methods. Different hierarchies exist for different question types, and even experts may disagree on the exact rank of information in the evidence hierarchies. The following image represents the hierarchy of evidence provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). 1

Most experts agree that the higher up the hierarchy the study design is positioned, the more rigorous the methodology and hence the more likely it is that the study design can minimise the effect of bias on the results of the study. In most evidence hierachies current, well designed systematic reviews and meta-analyses are at the top of the pyramid, and expert opinion and anecdotal experience are at the bottom. 2

Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses

Well done systematic reviews, with or without an included meta-analysis, are generally considered to provide the best evidence for all question types as they are based on the findings of multiple studies that were identified in comprehensive, systematic literature searches. However, the position of systematic reviews at the top of the evidence hierarchy is not an absolute. For example:

- The process of a rigorous systematic review can take years to complete and findings can therefore be superseded by more recent evidence.

- The methodological rigor and strength of findings must be appraised by the reader before being applied to patients.

- A large, well conducted Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) may provide more convincing evidence than a systematic review of smaller RCTs. 4

Primary Studies

If a current, well designed systematic review is not available, go to primary studies to answer your question. The best research designs for a primary study varies depending on the question type. The table below lists optimal study methodologies for the main types of questions.

Note that the Clinical Queries filter available in some databases such as PubMed and CINAHL matches the question type to studies with appropriate research designs. When searching primary literature, look first for reports of clinical trials that used the best research designs. Remember as you search, though, that the best available evidence may not come from the optimal study type. For example, if treatment effects found in well designed cohort studies are sufficiently large and consistent, those cohort studies may provide more convincing evidence than the findings of a weaker RCT.

What is a Systematic Review?

A systematic review synthesises the results from all available studies in a particular area, and provides a thorough analysis of the results, strengths and weaknesses of the collated studies. A systematic review has several qualities:

- It addresses a focused, clearly formulated question.

- It uses systematic and explicit methods:

a. to identify, select and critically appraise relevant research, and b. to collect and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review

Systematic reviews may or may not include a meta-analysis used to summarise and analyse the statistical results of included studies. This requires the studies to have the same outcome measure.

What is a Narrative Review?

Narrative reviews (often just called Reviews) are opinion with selective illustrations from the literature. They do not qualify as adequate evidence to answer clinical questions. Rather than answering a specific clinical question, they provide an overview of the research landscape on a given topic and so maybe useful for background information. Narrative reviews usually lack systematic search protocols or explicit criteria for selecting and appraising evidence and are threfore very prone to bias. 5

Filtered information appraises the quality of a study and recommend its application in practice. The critical appraisal of the individual articles has already been done for you—which is a great time saver. Because the critical appraisal has been completed, filtered literature is appropriate to use for clinical decision-making at the point-of-care. In addition to saving time, filtered literature will often provide a more definitive answer than individual research reports. Examples of filtered resources include, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , BMJ Clincial Evidence , and ACP Journal Club .

Unfiltered information are original research studies that have not yet been synthesized or aggregated. As such, they are the more difficult to read, interpret, and apply to practice. Examples of unfiltered resources include, CINAHL , EMBASE , Medline , and PubMe d . 3

The Cochrane Collaboration is an international voluntary organization that prepares, maintains and promotes the accessibility of systematic reviews of the effects of healthcare.

The Cochrane Library is a database from the Cochrane Collaboration that allows simultaneous searching of six EBP databases. Cochrane Reviews are systematic reviews authored by members of the Cochrane Collaboration and available via The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . They are widely recognised as the gold standard in systematic reviews due to the rigorous methodology used.

Abstracts of completed Cochrane Reviews are freely available through PubMed and Meta-Search engines such as TRIP database.

National access to the Cochrane Library is provided by the Australian Government via the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC).

1. National Health and Medical Research Council. (2009). [Hierarchy of Evidence] . Retrieved 2 July, 2014 from: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/

2. Hoffman, T., Bennett, S., & Del Mar, C. (2013). Evidence-Based Practice: Across the Health Professions (2nd ed.). Chatswood, NSW: Elsevier.

3. Kendall, S. (2008). Evidence-based resources simplified. Canadian Family Physician , 54, 241-243

4. Davidson, M., & Iles, R. (2013). Evidence-based practice in therapeutic health care. In, Liamputtong, P. (ed.). Research Methods in Health: Foundations for Evidence-Based Practice (2nd ed.). South Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

5. Cook, D., Mulrow, C., & Haynes, R. (1997). Systematic reviews: synthesis of best evidence for clinical decisions. Annals of Internal Medicine , 126, 376–80.

- << Previous: Types of Clinical Question

- Next: Module 2: Acquire >>

- Last Updated: Jul 24, 2023 4:08 PM

- URL: https://canberra.libguides.com/evidence

- Library databases

- Library website

Evidence-Based Research: Levels of Evidence Pyramid

Introduction.

One way to organize the different types of evidence involved in evidence-based practice research is the levels of evidence pyramid. The pyramid includes a variety of evidence types and levels.

- systematic reviews

- critically-appraised topics

- critically-appraised individual articles

- randomized controlled trials

- cohort studies

- case-controlled studies, case series, and case reports

- Background information, expert opinion

Levels of evidence pyramid

The levels of evidence pyramid provides a way to visualize both the quality of evidence and the amount of evidence available. For example, systematic reviews are at the top of the pyramid, meaning they are both the highest level of evidence and the least common. As you go down the pyramid, the amount of evidence will increase as the quality of the evidence decreases.

Text alternative for Levels of Evidence Pyramid diagram

EBM Pyramid and EBM Page Generator, copyright 2006 Trustees of Dartmouth College and Yale University. All Rights Reserved. Produced by Jan Glover, David Izzo, Karen Odato and Lei Wang.

Filtered Resources

Filtered resources appraise the quality of studies and often make recommendations for practice. The main types of filtered resources in evidence-based practice are:

Scroll down the page to the Systematic reviews , Critically-appraised topics , and Critically-appraised individual articles sections for links to resources where you can find each of these types of filtered information.

Systematic reviews

Authors of a systematic review ask a specific clinical question, perform a comprehensive literature review, eliminate the poorly done studies, and attempt to make practice recommendations based on the well-done studies. Systematic reviews include only experimental, or quantitative, studies, and often include only randomized controlled trials.

You can find systematic reviews in these filtered databases :

- Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Cochrane systematic reviews are considered the gold standard for systematic reviews. This database contains both systematic reviews and review protocols. To find only systematic reviews, select Cochrane Reviews in the Document Type box.

- JBI EBP Database (formerly Joanna Briggs Institute EBP Database) This database includes systematic reviews, evidence summaries, and best practice information sheets. To find only systematic reviews, click on Limits and then select Systematic Reviews in the Publication Types box. To see how to use the limit and find full text, please see our Joanna Briggs Institute Search Help page .

You can also find systematic reviews in this unfiltered database :

To learn more about finding systematic reviews, please see our guide:

- Filtered Resources: Systematic Reviews

Critically-appraised topics

Authors of critically-appraised topics evaluate and synthesize multiple research studies. Critically-appraised topics are like short systematic reviews focused on a particular topic.

You can find critically-appraised topics in these resources:

- Annual Reviews This collection offers comprehensive, timely collections of critical reviews written by leading scientists. To find reviews on your topic, use the search box in the upper-right corner.

- Guideline Central This free database offers quick-reference guideline summaries organized by a new non-profit initiative which will aim to fill the gap left by the sudden closure of AHRQ’s National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC).

- JBI EBP Database (formerly Joanna Briggs Institute EBP Database) To find critically-appraised topics in JBI, click on Limits and then select Evidence Summaries from the Publication Types box. To see how to use the limit and find full text, please see our Joanna Briggs Institute Search Help page .

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Evidence-based recommendations for health and care in England.

- Filtered Resources: Critically-Appraised Topics

Critically-appraised individual articles

Authors of critically-appraised individual articles evaluate and synopsize individual research studies.

You can find critically-appraised individual articles in these resources:

- EvidenceAlerts Quality articles from over 120 clinical journals are selected by research staff and then rated for clinical relevance and interest by an international group of physicians. Note: You must create a free account to search EvidenceAlerts.

- ACP Journal Club This journal publishes reviews of research on the care of adults and adolescents. You can either browse this journal or use the Search within this publication feature.

- Evidence-Based Nursing This journal reviews research studies that are relevant to best nursing practice. You can either browse individual issues or use the search box in the upper-right corner.

To learn more about finding critically-appraised individual articles, please see our guide:

- Filtered Resources: Critically-Appraised Individual Articles

Unfiltered resources

You may not always be able to find information on your topic in the filtered literature. When this happens, you'll need to search the primary or unfiltered literature. Keep in mind that with unfiltered resources, you take on the role of reviewing what you find to make sure it is valid and reliable.

Note: You can also find systematic reviews and other filtered resources in these unfiltered databases.

The Levels of Evidence Pyramid includes unfiltered study types in this order of evidence from higher to lower:

You can search for each of these types of evidence in the following databases:

TRIP database

Background information & expert opinion.

Background information and expert opinions are not necessarily backed by research studies. They include point-of-care resources, textbooks, conference proceedings, etc.

- Family Physicians Inquiries Network: Clinical Inquiries Provide the ideal answers to clinical questions using a structured search, critical appraisal, authoritative recommendations, clinical perspective, and rigorous peer review. Clinical Inquiries deliver best evidence for point-of-care use.

- Harrison, T. R., & Fauci, A. S. (2009). Harrison's Manual of Medicine . New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. Contains the clinical portions of Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine .

- Lippincott manual of nursing practice (8th ed.). (2006). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Provides background information on clinical nursing practice.

- Medscape: Drugs & Diseases An open-access, point-of-care medical reference that includes clinical information from top physicians and pharmacists in the United States and worldwide.

- Virginia Henderson Global Nursing e-Repository An open-access repository that contains works by nurses and is sponsored by Sigma Theta Tau International, the Honor Society of Nursing. Note: This resource contains both expert opinion and evidence-based practice articles.

- Previous Page: Phrasing Research Questions

- Next Page: Evidence Types

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Darrell W. Krueger Library Krueger Library

Evidence based practice toolkit.

- What is EBP?

- Asking Your Question

Levels of Evidence / Evidence Hierarchy

Evidence pyramid (levels of evidence), definitions, research designs in the hierarchy, clinical questions --- research designs.

- Evidence Appraisal

- Find Research

- Standards of Practice

Levels of evidence (sometimes called hierarchy of evidence) are assigned to studies based on the research design, quality of the study, and applicability to patient care. Higher levels of evidence have less risk of bias .

Levels of Evidence (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt 2023)

*Adapted from: Melnyk, & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2023). Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice (Fifth edition.). Wolters Kluwer.

Levels of Evidence (LoBiondo-Wood & Haber 2022)

Adapted from LoBiondo-Wood, G. & Haber, J. (2022). Nursing research: Methods and critical appraisal for evidence-based practice (10th ed.). Elsevier.

" Evidence Pyramid " is a product of Tufts University and is licensed under BY-NC-SA license 4.0

Tufts' "Evidence Pyramid" is based in part on the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine: Levels of Evidence (2009)

- Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine Glossary

Different types of clinical questions are best answered by different types of research studies. You might not always find the highest level of evidence (i.e., systematic review or meta-analysis) to answer your question. When this happens, work your way down to the next highest level of evidence.

This table suggests study designs best suited to answer each type of clinical question.

- << Previous: Asking Your Question

- Next: Evidence Appraisal >>

- Last Updated: Apr 2, 2024 7:02 PM

- URL: https://libguides.winona.edu/ebptoolkit

- Research Process

Levels of evidence in research

- 5 minute read

- 97.7K views

Table of Contents

Level of evidence hierarchy

When carrying out a project you might have noticed that while searching for information, there seems to be different levels of credibility given to different types of scientific results. For example, it is not the same to use a systematic review or an expert opinion as a basis for an argument. It’s almost common sense that the first will demonstrate more accurate results than the latter, which ultimately derives from a personal opinion.

In the medical and health care area, for example, it is very important that professionals not only have access to information but also have instruments to determine which evidence is stronger and more trustworthy, building up the confidence to diagnose and treat their patients.

5 levels of evidence

With the increasing need from physicians – as well as scientists of different fields of study-, to know from which kind of research they can expect the best clinical evidence, experts decided to rank this evidence to help them identify the best sources of information to answer their questions. The criteria for ranking evidence is based on the design, methodology, validity and applicability of the different types of studies. The outcome is called “levels of evidence” or “levels of evidence hierarchy”. By organizing a well-defined hierarchy of evidence, academia experts were aiming to help scientists feel confident in using findings from high-ranked evidence in their own work or practice. For Physicians, whose daily activity depends on available clinical evidence to support decision-making, this really helps them to know which evidence to trust the most.

So, by now you know that research can be graded according to the evidential strength determined by different study designs. But how many grades are there? Which evidence should be high-ranked and low-ranked?

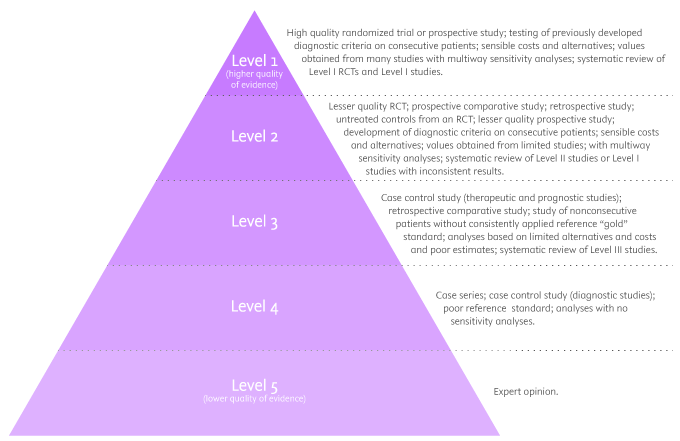

There are five levels of evidence in the hierarchy of evidence – being 1 (or in some cases A) for strong and high-quality evidence and 5 (or E) for evidence with effectiveness not established, as you can see in the pyramidal scheme below:

Level 1: (higher quality of evidence) – High-quality randomized trial or prospective study; testing of previously developed diagnostic criteria on consecutive patients; sensible costs and alternatives; values obtained from many studies with multiway sensitivity analyses; systematic review of Level I RCTs and Level I studies.

Level 2: Lesser quality RCT; prospective comparative study; retrospective study; untreated controls from an RCT; lesser quality prospective study; development of diagnostic criteria on consecutive patients; sensible costs and alternatives; values obtained from limited stud- ies; with multiway sensitivity analyses; systematic review of Level II studies or Level I studies with inconsistent results.

Level 3: Case-control study (therapeutic and prognostic studies); retrospective comparative study; study of nonconsecutive patients without consistently applied reference “gold” standard; analyses based on limited alternatives and costs and poor estimates; systematic review of Level III studies.

Level 4: Case series; case-control study (diagnostic studies); poor reference standard; analyses with no sensitivity analyses.

Level 5: (lower quality of evidence) – Expert opinion.

By looking at the pyramid, you can roughly distinguish what type of research gives you the highest quality of evidence and which gives you the lowest. Basically, level 1 and level 2 are filtered information – that means an author has gathered evidence from well-designed studies, with credible results, and has produced findings and conclusions appraised by renowned experts, who consider them valid and strong enough to serve researchers and scientists. Levels 3, 4 and 5 include evidence coming from unfiltered information. Because this evidence hasn’t been appraised by experts, it might be questionable, but not necessarily false or wrong.

Examples of levels of evidence

As you move up the pyramid, you will surely find higher-quality evidence. However, you will notice there is also less research available. So, if there are no resources for you available at the top, you may have to start moving down in order to find the answers you are looking for.

- Systematic Reviews: -Exhaustive summaries of all the existent literature about a certain topic. When drafting a systematic review, authors are expected to deliver a critical assessment and evaluation of all this literature rather than a simple list. Researchers that produce systematic reviews have their own criteria to locate, assemble and evaluate a body of literature.

- Meta-Analysis: Uses quantitative methods to synthesize a combination of results from independent studies. Normally, they function as an overview of clinical trials. Read more: Systematic review vs meta-analysis .

- Critically Appraised Topic: Evaluation of several research studies.

- Critically Appraised Article: Evaluation of individual research studies.

- Randomized Controlled Trial: a clinical trial in which participants or subjects (people that agree to participate in the trial) are randomly divided into groups. Placebo (control) is given to one of the groups whereas the other is treated with medication. This kind of research is key to learning about a treatment’s effectiveness.

- Cohort studies: A longitudinal study design, in which one or more samples called cohorts (individuals sharing a defining characteristic, like a disease) are exposed to an event and monitored prospectively and evaluated in predefined time intervals. They are commonly used to correlate diseases with risk factors and health outcomes.

- Case-Control Study: Selects patients with an outcome of interest (cases) and looks for an exposure factor of interest.

- Background Information/Expert Opinion: Information you can find in encyclopedias, textbooks and handbooks. This kind of evidence just serves as a good foundation for further research – or clinical practice – for it is usually too generalized.

Of course, it is recommended to use level A and/or 1 evidence for more accurate results but that doesn’t mean that all other study designs are unhelpful or useless. It all depends on your research question. Focusing once more on the healthcare and medical field, see how different study designs fit into particular questions, that are not necessarily located at the tip of the pyramid:

- Questions concerning therapy: “Which is the most efficient treatment for my patient?” >> RCT | Cohort studies | Case-Control | Case Studies

- Questions concerning diagnosis: “Which diagnose method should I use?” >> Prospective blind comparison

- Questions concerning prognosis: “How will the patient’s disease will develop over time?” >> Cohort Studies | Case Studies

- Questions concerning etiology: “What are the causes for this disease?” >> RCT | Cohort Studies | Case Studies

- Questions concerning costs: “What is the most cost-effective but safe option for my patient?” >> Economic evaluation

- Questions concerning meaning/quality of life: “What’s the quality of life of my patient going to be like?” >> Qualitative study

Find more about Levels of evidence in research on Pinterest:

17 March 2021 – Elsevier’s Mini Program Launched on WeChat Brings Quality Editing Straight to your Smartphone

- Manuscript Review

Professor Anselmo Paiva: Using Computer Vision to Tackle Medical Issues with a Little Help from Elsevier Author Services

You may also like.

Descriptive Research Design and Its Myriad Uses

Five Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Biomedical Research Paper

Making Technical Writing in Environmental Engineering Accessible

To Err is Not Human: The Dangers of AI-assisted Academic Writing

When Data Speak, Listen: Importance of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Choosing the Right Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers

Why is data validation important in research?

Writing a good review article

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Abstract. Objective: The objective of this study is to outline explicit criteria for assessing the contribution of qualitative empirical studies in health and medicine, leading to a hierarchy of evidence specific to qualitative methods. Study design and setting: This paper arose from a series of critical appraisal exercises based on recent ...

A hierarchy of evidence-for-practice specific to qualitative methods provides a useful guide for the critical appraisal of papers using these methods and for defining the strength of evidence as a basis for decision making and policy generation. 1. Introduction. In the medical and health literature, there has been a steady rise in the number of ...

A qualitative hierarchy of evidence-for-practice. The hierarchy we are proposing is summarized in Fig. 1 and Table 1. The emphasis in this hierarchy is on the capacity of reported research to provide evidence-for-practice or policy. In common with the quantitative hierarchies of method, research using methods lower in the hierarchy can be well ...

By assigning levels of evidence to qualitative studies, JBI addresses one of the most difficult problems in qualitative research, that of defining clear criteria for selecting high-quality qualitative studies.(p.43)3 [ This is an area where the JBI levels of evidence differ in comparison to many other

With this multidisciplinary basis for clinical knowledge comes "qualitative" research, an empirical method seemingly at odds with traditional rules of evidence and with the hierarchy of research designs propounded by evidence-based medicine. 1, 2 The philosophy of evidence-based medicine suggests that as ways of knowing, induction is ...

The hierarchy provides a guide that helps the determine best evidence; however, factors such as research quality will also exert an influence on the value of the available evidence. Finally, for an intervention to be fully evaluated, evidence on its effectiveness, appropriateness and feasibility will be required.

We describe four levels of a qualitative hierarchy of evidence-for-practice. The least likely studies to produce good evidence-for-practice are single case studies, followed by descriptive studies that may provide helpful lists of quotations but do not offer detailed analysis. ... to devise a hierarchy of qualitative research designs ...

A hierarchy of evidence-for-practice specific to qualitative methods provides a useful guide for the critical appraisal of papers using these methods and for defining the strength of evidence as a basis for decision making and policy generation. Author and article information. Journal. PubMed ID:: 17161753. DOI:: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.014.

The proposed new evidence-based medicine pyramid. (A) The traditional pyramid. (B) Revising the pyramid: (1) lines separating the study designs become wavy (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation), (2) systematic reviews are 'chopped off' the pyramid. (C) The revised pyramid: systematic reviews are a lens through ...

Hierarchy of Evidence: Quantitative Research Design. Quantitative hierarchies of evidence are a standard way of judging the "levels of evidence" for clinical practices in medicine. Based on ...

A hierarchy of evidence for assessing qualitative health research. OBJECTIVE: The objective of this study is to outline explicit criteria for assessing the contribution of qualitative empirical studies in health and medicine, leading to a hierarchy of evidence specific to qualitative methods. STUDY DESIGN AND SETTING: This paper arose from a ...

The following image represents the hierarchy of evidence provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). 1 Most experts agree that the higher up the hierarchy the study design is positioned, the more rigorous the methodology and hence the more likely it is that the study design can minimise the effect of bias on the ...

My approach to this is first to establish two statements: 1) All research that is considered scientific must relate to the claim of evidence; 2) Qualitative research cannot build upon a foundation designed for a radically different kind of research. The first statement is easy, because if evidence is not at all involved, it is not about science ...

The pyramid includes a variety of evidence types and levels. Filtered resources: pre-evaluated in some way. systematic reviews. critically-appraised topics. critically-appraised individual articles. Unfiltered resources: typically original research and first-person accounts. randomized controlled trials. cohort studies.

Furthermore, evidence‐based practice and reflection are both processes that share very similar aims and procedures. Therefore, to enable the implementation of best evidence in practice, the hierarchy of evidence might need to be abandoned and reflection to become a core component of the evidence‐based practice movement.

Evidence from well-designed case-control or cohort studies. Level 5. Evidence from systematic reviews of descriptive and qualitative studies (meta-synthesis) Level 6. Evidence from a single descriptive or qualitative study, EBP, EBQI and QI projects. Level 7. Evidence from the opinion of authorities and/or reports of expert committees, reports ...

An eight-level hierarchy of evidence for healthcare design research is proposed that is expected to improve upon previous hierarchies in three major ways: (a) including research methods that are more relevant to healthcare design research, (b) enhancing evaluation accuracy and reliability by providing a clearer definition of studies based on their key components rather than using study labels ...

Basically, level 1 and level 2 are filtered information - that means an author has gathered evidence from well-designed studies, with credible results, and has produced findings and conclusions appraised by renowned experts, who consider them valid and strong enough to serve researchers and scientists. Levels 3, 4 and 5 include evidence ...