Advertisement

Enhancing Critical Thinking Skills through Decision-Based Learning

- Published: 09 March 2022

- Volume 47 , pages 711–734, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Kenneth J. Plummer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8946-4140 1 ,

- Mansureh Kebritchi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4074-2546 2 ,

- Heather M. Leary ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2487-578X 3 &

- Denise M. Halverson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5825-2217 4

1902 Accesses

6 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

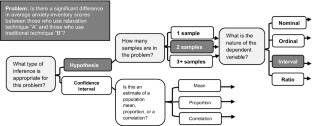

One of the major issues related to critical thinking in higher education consists of how educators teach and inspire students to develop greater critical thinking. skills. The current study was conducted to explore whether Decision-based Learning (DBL), an innovative teaching method, can enhance students’ critical thinking skills. This mixed methods ex-post facto study aimed to identify the areas of overlap between DBL and critical thinking components based on an empirically tested framework. The study was conducted at a large, private university in the western United States with two instructors and 89 undergraduate students. Data were collected via DBL publications, course midterm exam scores, and instructor interviews. Since this was an ex post facto study, the exam items were not initially written to target critical thinking skills as defined by the critical thinking framework we chose. An analysis was done on the cognitive processes elicited by the exam items after the fact, and it was found that they elicited three of the six skills described in this framework. In addition, participation in DBL activities related to statistically significant higher exam scores on these items after controlling for a standardized pre-test taken by both treatment and control groups prior to beginning the course. The effect size was large in favor of the DBL courses. In addition, two instructors reported their perspectives on the critical thinking skills exhibited by their students using DBL. The evidence collected across these three sources of information supports a connection between DBL and four of the six critical thinking components within the framework we selected.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

From digital literacy to digital competence: the teacher digital competency (TDC) framework

Garry Falloon

A literature review: efficacy of online learning courses for higher education institution using meta-analysis

Mayleen Dorcas B. Castro & Gilbert M. Tumibay

Study smart – impact of a learning strategy training on students’ study behavior and academic performance

Felicitas Biwer, Anique de Bruin & Adam Persky

Data Availability

Data for this project are available at: https://www.openicpsr.org/openicpsr/workspace?goToPath=/openicpsr/145921&goToLevel=project

Code Availability

No code was generated as a result of this study.

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives . Longman.

Google Scholar

Bensinger, H. (2015). Critical-thinking challenge games and teaching outside of the box. Nurse Educator, 40 (2), 57–58.

Article Google Scholar

Bezanilla, M. J., Fernández-Nogueira, D., Poblete, M., & Galindo-Domínguez, H. (2019). Methodologies for teaching-learning critical thinking in higher education: The teacher’s view. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 4, 33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2019.100584 .

Biggs, J. B. (2011). Teaching for quality learning at university: What the student does . McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (2000). How people learn (11th ed.). National academy press.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2010). Occupational Outlook Handbook , 2010–2011 edition. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/careeroutlook/2010/spring/spring2010ooq.pdf

Butler, H. A. (2012). Halpern critical thinking assessment predicts real-world outcomes of critical thinking. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 26 (5), 721–729.

Cardenas, C., West, R., Swan, R., & Plummer, K. (2020). Modeling expertise through decision-based learning: Theory, practice, and technology applications. Revista de Educación a Distancia (RED), 20 (64).

Clarke, L. E., & Gabert, T. E. (2004). Faculty issues related to adult degree programs. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 10, 31–40.

Cohen, J. (1992). Quantitative methods in psychology: A power primer. Psychological Bulletin Journal, 112, 1155–1159.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Sage.

Doo, M. Y., Bonk, C., & Heo, H. (2020). A meta-analysis of scaffolding effects in online learning in higher education. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 21 (3), 60–80.

El Soufi, N., & See, B. H. (2019). Does explicit teaching of critical thinking improve critical thinking skills of English language learners in higher education? A critical review of causal evidence. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 60 (1), 140–162.

Ennis, R. H., & Weir, E. (1985). The Ennis–Weir critical thinking essay test. Midwest Publications .

Facione, P. A. (1990). Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instructions. Research findings and recommendations . California Academic Press.

Facione, P. A. (2020). Critical thinking: What it is and why it counts. Insight Assessment , 1–28. Retrieved from https://www.insightassessment.com/wp-content/uploads/ia/pdf/whatwhy.pdf

Facione, P. A., Facione, N. C., & Gittens, C. A. (2020). What the data tell us about human reasoning. In D. Fasko & F. Fair (Eds.), Critical thinking and reasoning: Theory, development, instruction, and assessment (pp. 272–297). Brill Sense.

Fahim, M., & Masouleh, N. S. (2012). Critical thinking in higher education: A pedagogical look. Theory & Practice In Language Studies, 2 (7), 1370–1375. https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.2.7.1370-1375 .

Felten, P., & Finley, A. (2019). Transparent design in higher education teaching and leadership: A guide to implementing the transparency framework institution-wide to improve learning and retention . Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Fischer, L., Plummer, K. J., Vogeler, H. A., & Moulton, S. (2021). I am not a real statistician; I just play one on TV. In N. Wentworth, K. J. Plummer, & R. H. Swan (Eds.), Decision-based learning: An innovative pedagogy that unpacks expert knowledge for the novice learner (pp. 19–30). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Chapter Google Scholar

van Gelder, T. (2005). Teaching critical thinking: Some lessons from cognitive science. College Teaching, 53 (1), 41–46.

Halpern, D. F. (1998). Teaching critical thinking for transfer across domains. Dispositions, skills, structure training, and metacognitive monitoring. The American Psychologist, 53 (4), 449–455. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.53.4.449 .

Halpern, D. F. (1999). Teaching for critical thinking: Helping college students develop the skills and dispositions of a critical thinker. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 80, 69–74.

Halx, M. D., & Reybold, L. E. (2006). A pedagogy of force: Faculty perspectives of critical thinking capacity in undergraduate students. The Journal of General Education, 54 (4), 293–315. https://doi.org/10.1353/jge.2006.0009 .

Hutton, R. J., & Klein, G. (1999). Expert decision making. Systems Engineering, 2 (1), 32–45.

Kebritchi, M., Nunn, S., & Fedock, B. (2016). Examining critical thinking strategies, components, and challenges in higher education: A systematic literature review . Concurrent session presented at the Association for Educational Communications and Technology (AECT).

Kemper, E., Stringfield, S., & Teddlie, C. (2003). Mixed methods sampling strategies in social science research. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in the social and behaviorals (pp. 273–296). Sage.

Kettles, D. (2021). Decision-based learning in an information systems course. In N. Wentworth, K. J. Plummer, & R. H. Swan (Eds.), Decision-based learning: An innovative pedagogy that unpacks expert knowledge for the novice learner (pp. 67–78). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Kim, N. J., Belland, B. R., & Axelrod, D. (2018). Scaffolding for optimal challenge in K–12 problem-based learning. The interdisciplinary journal of problem-based . Learning, 13 (1), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1712 .

Ku, K. Y. L. (2009). Assessing students’ critical thinking performance: Urging for measurements using multi-response format. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 4 (1), 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2009.02.001 .

Kuhn, D., & Dean, D., Jr. (2004). Metacognition: A bridge between cognitive psychology and educational practice. Theory Into Practice, 43 (4), 268–273.

Kyngäs H., & Kaakinen P. (2020) Deductive content analysis. In: H. Kyngäs, K. Mikkonen, & M. Kääriäinen (Eds.) T he application of content analysis in nursing science research (pp. 23-30). Springer Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-30199-6_3

Larsson, K. (2017). Understanding and teaching critical thinking—A new approach. International Journal of Educational Research, 84, 32–42.

Lipman, M. (1998). Teaching students to think reasonably; some findings of the philosophy for children program. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational strategies, Issues and Ideas, 71 (5), 277–280.

Lorch, R. F., Lorch, E. P., & Klusewitz, M. A. (1993). College students’ conditional knowledge about reading. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85 (2), 239.

Marin, L., & Halpern, D. F. (2011). Pedagogy for developing critical thinking in adolescents: Explicit instruction produces greatest gains. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 6, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2010.08.002 .

Mbato, C. L. (2019). Indonesian EFL learners’ critical thinking in reading: Bridging the gap between declarative, procedural and conditional knowledge. Humaniora, 31 (1), 92.

Nelson, T. G. (2021). Exploring decision-based learning in an engineering context. In N. Wentworth, K. J. Plummer, & R. H. Swan (Eds.), Decision-based learning: An innovative pedagogy that unpacks expert knowledge for the novice learner (pp. 55–66). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Nicholas, M. C., & Raider-Roth, M. (2016). A hopeful pedagogy to critical thinking. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 10 (2), 1–10 .

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). An overview of psychological measurement. In B. B. Wolman (Ed.), Clinical diagnosis of mental disorders . Springer.

Owens, M. A., & Mills, E. R. (2021). Using decision-based learning to teach qualitative research evaluation. In N. N. Wentworth, K. J. Plummer, & R. H. Swan (Eds.), Decision-based learning: An innovative pedagogy that unpacks expert knowledge for the novice learner (pp. 93–102). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Paris, S. G., Lipson, M. Y., & Wixson, K. K. (1983). Becoming a strategic reader. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8 (3), 293–316.

Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (2005). How college affects students: A third decade of research (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Pixton, D. (2021). Information literacy and decision-based learning. In N. Wentworth, K. J. Plummer, & R. H. Swan (Eds.), Decision-based learning: An innovative pedagogy that unpacks expert knowledge for the novice learner (pp. 133–146). Emerald.

Plummer, K., Swan, R., & Lush, N. (2017). Introduction to decision based learning. In IATED (pp. 2629–2638). Proceedings of 11th International Technology, Education and Development Conference.

Plummer, K., Taeger, S., & Burton, M. (2020). Decision-based learning in religious education. Teaching Theology and Religion, 23 (2), 110–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/teth.12538 .

Reinking, D., Mealey, D., & Ridgeway, V. G. (1993). Developing preservice teachers’ conditional knowledge of content area reading strategies. Journal of Reading, 36 (6), 458–469.

Richardson, J. T. (2011). Eta squared and partial eta squared as measures of effect size in educational research. Educational Research Review, 6 (2), 135–147.

Sansom, R. L., Suh, E., & Plummer, K. J. (2019). Decision-based learning:″if I just knew which equation to use, I know I could solve this problem!″ Journal of Chemical Education, 96 (3), 445–454.

Snyder, L. G., & Snyder, M. J. (2008). Teaching critical thinking and problem solving skills. The Journal of Research in Business Education, 50 (2), 90.

Swan, R. H. (2021). Why decision-based learning is different. In N. Wentworth, K. J. Plummer, & R. H. Swan (Eds.), Decision-based learning: An innovative pedagogy that unpacks expert knowledge for the novice learner (pp. 1–9). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80043-202-420211001 .

Swan, R.H., Plummer, K.J. & West, R.E. (2020). Toward functional expertise through formal education: Identifying an opportunity for higher education. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68 (5), 2551–2568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09778-1

Turns, S. R., & Van Meter, P. N. (2011). Applying knowledge from educational psychology and cognitive science to a first course in thermodynamics. In Proceedings of the ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition .

Zheng, Y., Shekhar, S., Jose, A. A., & Rai, S. K. (2019). Integrating context-awareness and multi-criteria decision making in educational learning. In Proceedings of the 34th ACM/SIGAPP Symposium on Applied Computing (2453–2460).

Download references

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Center for Teaching and Learning, Brigham Young University, 3830E HBLL, Provo, UT, 84602, USA

Kenneth J. Plummer

Center for Educational and Instructional Technology Research, University of Phoenix, Arizona, USA

Mansureh Kebritchi

Department of Instructional Psychology & Technology, Brigham Young University, Provo, USA

Heather M. Leary

Department of Mathematics, Brigham Young University, Provo, USA

Denise M. Halverson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Kenneth J. Plummer, Heather M. Leary, and Denise M. Halverson. The literature review, abstract, introduction, discussion sections were prepared by Mansureh Kebritchi and Ken Plummer. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kenneth J. Plummer .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): The First Author is a founding partner in Conate Incorporated, a company developing software to support decision-based learning pedagogy.

Consent to Publish

The two instructors who were interviewed signed an Internal Review Board consent form in which they gave their consent to be research subjects.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 54 kb)

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Plummer, K.J., Kebritchi, M., Leary, H.M. et al. Enhancing Critical Thinking Skills through Decision-Based Learning. Innov High Educ 47 , 711–734 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-022-09595-9

Download citation

Accepted : 31 January 2022

Published : 09 March 2022

Issue Date : August 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-022-09595-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Decision-based learning

- Critical thinking

- Innovative teaching

- Conditional knowledge

- schema building

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 19 March 2024

Interventions, methods and outcome measures used in teaching evidence-based practice to healthcare students: an overview of systematic reviews

- Lea D. Nielsen 1 ,

- Mette M. Løwe 2 ,

- Francisco Mansilla 3 ,

- Rene B. Jørgensen 4 ,

- Asviny Ramachandran 5 ,

- Bodil B. Noe 6 &

- Heidi K. Egebæk 7

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 306 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

218 Accesses

Metrics details

To fully implement the internationally acknowledged requirements for teaching in evidence-based practice, and support the student’s development of core competencies in evidence-based practice, educators at professional bachelor degree programs in healthcare need a systematic overview of evidence-based teaching and learning interventions. The purpose of this overview of systematic reviews was to summarize and synthesize the current evidence from systematic reviews on educational interventions being used by educators to teach evidence-based practice to professional bachelor-degree healthcare students and to identify the evidence-based practice-related learning outcomes used.

An overview of systematic reviews. Four databases (PubMed/Medline, CINAHL, ERIC and the Cochrane library) were searched from May 2013 to January 25th, 2024. Additional sources were checked for unpublished or ongoing systematic reviews. Eligibility criteria included systematic reviews of studies among undergraduate nursing, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, midwife, nutrition and health, and biomedical laboratory science students, evaluating educational interventions aimed at teaching evidence-based practice in classroom or clinical practice setting, or a combination. Two authors independently performed initial eligibility screening of title/abstracts. Four authors independently performed full-text screening and assessed the quality of selected systematic reviews using standardized instruments. Data was extracted and synthesized using a narrative approach.

A total of 524 references were retrieved, and 6 systematic reviews (with a total of 39 primary studies) were included. Overlap between the systematic reviews was minimal. All the systematic reviews were of low methodological quality. Synthesis and analysis revealed a variety of teaching modalities and approaches. The outcomes were to some extent assessed in accordance with the Sicily group`s categories; “skills”, “attitude” and “knowledge”. Whereas “behaviors”, “reaction to educational experience”, “self-efficacy” and “benefits for the patient” were rarely used.

Conclusions

Teaching evidence-based practice is widely used in undergraduate healthcare students and a variety of interventions are used and recognized. Not all categories of outcomes suggested by the Sicily group are used to evaluate outcomes of evidence-based practice teaching. There is a need for studies measuring the effect on outcomes in all the Sicily group categories, to enhance sustainability and transition of evidence-based practice competencies to the context of healthcare practice.

Peer Review reports

Evidence-based practice (EBP) enhances the quality of healthcare, reduces the cost, improves patient outcomes, empowers clinicians, and is recognized as a problem-solving approach [ 1 ] that integrates the best available evidence with clinical expertise and patient preferences and values [ 2 ]. A recent scoping review of EBP and patient outcomes indicates that EBPs improve patient outcomes and yield a positive return of investment for hospitals and healthcare systems. The top outcomes measured were length of stay, mortality, patient compliance/adherence, readmissions, pneumonia and other infections, falls, morbidity, patient satisfaction, patient anxiety/ depression, patient complications and pain. The authors conclude that healthcare professionals have a professional and ethical responsibility to provide expert care which requires an evidence-based approach. Furthermore, educators must become competent in EBP methodology [ 3 ].

According to the Sicily statement group, teaching and practicing EBP requires a 5-step approach: 1) pose an answerable clinical question (Ask), 2) search and retrieve relevant evidence (Search), 3) critically appraise the evidence for validity and clinical importance (Appraise), 4) applicate the results in practice by integrating the evidence with clinical expertise, patient preferences and values to make a clinical decision (Integrate), and 5) evaluate the change or outcome (Evaluate /Assess) [ 4 , 5 ]. Thus, according to the World Health Organization, educators, e.g., within undergraduate healthcare education, play a vital role by “integrating evidence-based teaching and learning processes, and helping learners interpret and apply evidence in their clinical learning experiences” [ 6 ].

A scoping review by Larsen et al. of 81 studies on interventions for teaching EBP within Professional bachelor-degree healthcare programs (PBHP) (in English undergraduate/ bachelor) shows that the majority of EBP teaching interventions include the first four steps, but the fifth step “evaluate/assess” is less often applied [ 5 ]. PBHP include bachelor-degree programs characterized by combined theoretical education and clinical training within nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, radiography, and biomedical laboratory students., Furthermore, an overview of systematic reviews focusing on practicing healthcare professionals EBP competencies testifies that although graduates may have moderate to high level of self-reported EBP knowledge, skills, attitudes, and beliefs, this does not translate into their subsequent EBP implementation [ 7 ]. Although this cannot be seen as direct evidence of inadequate EBP teaching during undergraduate education, it is irrefutable that insufficient EBP competencies among clinicians across healthcare disciplines impedes their efforts to attain highest care quality and improved patient outcomes in clinical practice after graduation.

Research shows that teaching about EBP includes different types of modalities. An overview of systematic reviews, published by Young et al. in 2014 [ 8 ] and updated by Bala et al. in 2021 [ 9 ], synthesizes the effects of EBP teaching interventions including under- and post graduate health care professionals, the majority being medical students. They find that multifaceted interventions with a combination of lectures, computer lab sessions, small group discussion, journal clubs, use of current clinical issues, portfolios and assignments lead to improvement in students’ EBP knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors compared to single interventions or no interventions [ 8 , 9 ]. Larsen et al. find that within PBHP, collaboration with clinical practice is the second most frequently used intervention for teaching EBP and most often involves four or all five steps of the EBP teaching approach [ 5 ]. The use of clinically integrated teaching in EBP is only sparsely identified in the overviews by Young et al. and Bala et al. [ 8 , 9 ]. Therefore, the evidence obtained within Bachelor of Medicine which is a theoretical education [ 10 ], may not be directly transferable for use in PBHP which combines theoretical and mandatory clinical education [ 11 ].

Since the overview by Young et al. [ 8 ], several reviews of interventions for teaching EBP used within PBHP have been published [ 5 , 12 , 13 , 14 ].

We therefore wanted to explore the newest evidence for teaching EBP focusing on PBHP as these programs are characterized by a large proportion of clinical teaching. These healthcare professions are certified through a PBHP at a level corresponding to a University Bachelor Degree, but with strong focus on professional practice by combining theoretical studies with mandatory clinical teaching. In Denmark, almost half of PBHP take place in clinical practice. These applied science programs qualify “the students to independently analyze, evaluate and reflect on problems in order to carry out practice-based, complex, and development-oriented job functions" [ 11 ]. Thus, both the purpose of these PBHP and the amount of clinical practice included in the educations contrast with for example medicine.

Thus, this overview, identifies the newest evidence for teaching EBP specifically within PBHP and by including reviews using quantitative and/or qualitative methods.

We believe that such an overview is important knowledge for educators to be able to take the EBP teaching for healthcare professions to a higher level. Also reviewing and describing EBP-related learning outcomes, categorizing them according to the seven assessment categories developed by the Sicily group [ 2 ], will be useful knowledge to educators in healthcare professions. These seven assessment categories for EBP learning including: Reaction to the educational experience, attitudes, self-efficacy, knowledge, skills, behaviors and benefits to patients, can be linked to the five-step EBP approach. E.g., reactions to the educational experience: did the educators teaching style enhance learners’ enthusiasm for asking questions? (Ask), self-efficacy: how well do learners think they critically appraise evidence? (Appraise), skills: can learners come to a reasonable interpretation of how to apply the evidence? (Integrate) [ 2 ]. Thus, this set of categories can be seen as a basic set of EBP-related learning outcomes to classify the impact from EBP educational interventions.

Purpose and review questions

A systematic overview of which evidence-based teaching interventions and which EBP-related learning outcomes that are used will give teachers access to important knowledge on what to implement and how to evaluate EBP teaching.

Thus, the purpose of this overview is to synthesize the latest evidence from systematic reviews about EBP teaching interventions in PBHP. This overview adds to the existing evidence by focusing on systematic reviews that a) include qualitative and/ or quantitative studies regardless of design, b) are conducted among PBHP within nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, midwifery, nutrition and health and biomedical laboratory science, and c) incorporate the Sicily group's 5-step approach and seven assessment categories when analyzing the EBP teaching interventions and EBP-related learning outcomes.

The questions of this overview of systematic reviews are:

Which educational interventions are described and used by educators to teach EBP to Professional Bachelor-degree healthcare students?

What EBP-related learning outcomes have been used to evaluate teaching interventions?

The study protocol was guided by the Cochrane Handbook on Overviews of Reviews [ 15 ] and the review process was reported in accordance with The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement [ 16 ] when this was consistent with the Cochrane Handbook.

Inclusion criteria

Eligible reviews fulfilled the inclusion criteria for publication type, population, intervention, and context (see Table 1 ). Failing a single inclusion criterion implied exclusion.

Search strategy

On January 25th 2024 a systematic search was conducted in; PubMed/Medline, CINAHL (EBSCOhost), ERIC (EBSCOhost) and the Cochrane library from May 2013 to January 25th, 2024 to identify systematic reviews published after the overview by Young et al. [ 8 ]. In collaboration with a research librarian, a search strategy of controlled vocabulary and free text terms related to systematic reviews, the student population, teaching interventions, teaching context, and evidence-based practice was developed (see Additional file 1 ). For each database, the search strategy was peer reviewed, revised, modified and subsequently pilot tested. No language restrictions were imposed.

To identify further eligible reviews, the following methods were used: Setting email alerts from the databases to provide weekly updates on new publications; backward and forward citation searching based on the included reviews by screening of reference lists and using the “cited by” and “similar results” function in PubMed and CINAHL; broad searching in Google Scholar (Advanced search), Prospero, JBI Evidence Synthesis and the OPEN Grey database; contacting experts in the field via email to first authors of included reviews, and by making queries via Twitter and Research Gate on any information on unpublished or ongoing reviews of relevance.

Selection and quality appraisal process

Database search results were merged, duplicate records were removed, and title/abstract were initially screened via Covidence [ 17 ]. The assessment process was pilot tested by four authors independently assessing eligibility and methodological quality of one potential review followed by joint discussion to reach a common understanding of the criteria used. Two authors independently screened each title/abstract for compliance with the predefined eligibility criteria. Disagreements were resolved by a third author. Four authors were paired for full text screening, and each pair assessed independently 50% of the potentially relevant reviews for eligibility and methodological quality.

For quality appraisal, two independent authors used the AMSTAR-2 (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews) for reviews including intervention studies [ 18 ] and the Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist for systematic reviews and research Synthesis (JBI checklist) [ 19 ] for reviews including both quantitative and qualitative or only qualitative studies. Uncertainties in assessments were resolved by requesting clarifying information from first authors of reviews and/or discussion with co-author to the present overview.

Overall methodological quality for included reviews was assessed using the overall confidence criteria of AMSTAR 2 based on scorings in seven critical domains [ 18 ] appraised as high (none or one non-critical flaw), moderate (more than one non-critical flaw), low (one critical weakness) or critically low (more than one critical weakness) [ 18 ]. For systematic reviews of qualitative studies [ 13 , 20 , 21 ] the critical domains of the AMSTAR 2, not specified in the JBI checklist, were added.

Data extraction and synthesis process

Data were initially extracted by the first author, confirmed or rejected by the last author and finally discussed with the whole author group until consensus was reached.

Data extraction included 1) Information about the search and selection process according to the PRISMA statement [ 16 , 22 ], 2) Characteristics of the systematic reviews inspired by a standard in the Cochrane Handbook (15), 3) A citation index inspired by Young et al. [ 8 ] used to illustrate overlap of primary studies in the included systematic reviews, and to ensure that data from each primary study were extracted only once [ 15 ], 4) Data on EBP teaching interventions and EBP-related outcomes. These data were extracted, reformatted (categorized inductively into two categories: “Collaboration interventions” and “ Educational interventions ”) and presented as narrative summaries [ 15 ]. Data on outcome were categorized according to the seven assessment categories, defined by the Sicily group, to classify the impact from EBP educational interventions: Reaction to the educational experience, attitudes, self-efficacy, knowledge, skills, behaviors and benefits to patients [ 2 ]. When information under points 3 and 4 was missing, data from the abstracts of the primary study articles were reviewed.

Results of the search

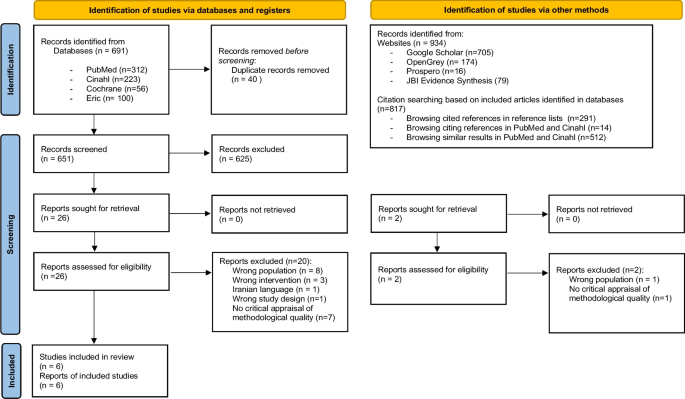

The database search yielded 691 references after duplicates were removed. Title and abstract screening deemed 525 references irrelevant. Searching via other methods yielded two additional references. Out of 28 study reports assessed for eligibility 22 were excluded, leaving a total of six systematic reviews. Screening resulted in 100% agreement among the authors. Figure 1 details the search and selection process. Reviews that might seem relevant but did not meet the eligibility criteria [ 15 ], are listed in Additional file 2 . One protocol for a potentially relevant review was identified as ongoing [ 23 ].

PRISMA flow diagram on search and selection of systematic reviews

Characteristics of included systematic reviews and overlap between them

The six systematic reviews originated from the Middle East, Asia, North America, Europe, Scandinavia, and Australia. Two out of six reviews did not identify themselves as systematic reviews but did fulfill this eligibility criteria [ 12 , 20 ]. All six represented a total of 64 primary studies and a total population of 6649 students (see Table 2 ). However, five of the six systematic reviews contained a total of 17 primary studies not eligible to our overview focus (e.g., postgraduate students) (see Additional file 3 ). Results from these primary studies were not extracted. Of the remaining primary studies, six were included in two, and one was included in three systematic reviews. Data from these studies were extracted only once to avoid double-counting. Thus, the six systematic reviews represented a total of 39 primary studies and a total population of 3394 students. Nursing students represented 3280 of these. One sample of 58 nutrition and health students and one sample of 56 mixed nursing and midwife students were included but none from physiotherapy, occupational therapy, or biomedical laboratory scientists. The majority ( n = 28) of the 39 primary studies had a quantitative design whereof 18 were quasi-experimental (see Additional file 4 ).

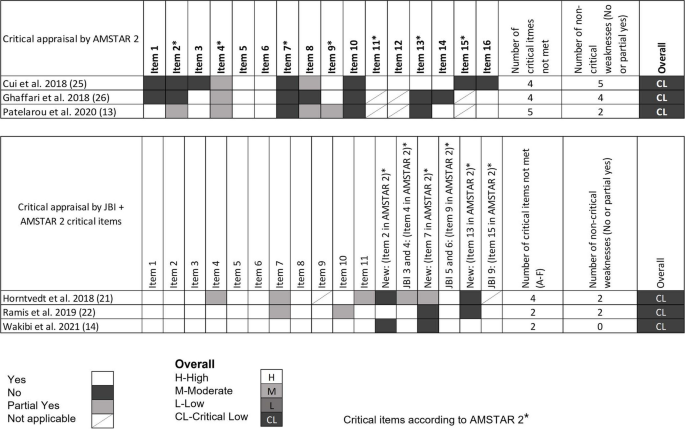

Quality of systematic review

All the included systematic reviews were assessed as having critically low quality with 100% concordance between the two designed authors (see Fig. 2 ) [ 18 ]. The main reasons for the low quality of the reviews were a) not demonstrating a registered protocol prior to the review [ 13 , 20 , 24 , 25 ], b) not providing a list of excluded studies with justification for exclusion [ 12 , 13 , 21 , 24 , 25 ] and c) not accounting for the quality of the individual studies when interpreting the result of the review [ 12 , 20 , 21 , 25 ].

Overall methodological quality assessment for systematic reviews. Quantitative studies [ 12 , 24 , 25 ] were assessed following the AMSTAR 2 critical domain guidelines. Qualitative studies [ 13 , 20 , 21 ] were assessed following the JBI checklist. For overall classification, qualitative studies were also assessed with the following critical AMSTAR 2 domains not specified in the JBI checklist (item 2. is the protocol registered before commencement of the review, item 7. justification for excluding individual studies and item 13. consideration of risk of bias when interpreting the results of the review)

Missing reporting of sources of funding for primary studies and not describing the included studies in adequate detail were, most often, the two non-critical items of the AMSTAR 2 and the JBI checklist, not met.

Most of the included reviews did report research questions including components of PICO, performed study selection and data extraction in duplicate, used appropriate methods for combining studies and used satisfactory techniques for assessing risk of bias (see Fig. 2 ).

Main findings from the systematic reviews

As illustrated in Table 2 , this overview synthesizes evidence on a variety of approaches to promote EBP teaching in both classroom and clinical settings. The systematic reviews describe various interventions used for teaching in EBP, which can be summarized into two themes: Collaboration Interventions and Educational Interventions.

Collaboration interventions to teach EBP

In general, the reviews point that interdisciplinary collaboration among health professionals and/or others e.g., librarian and professionals within information technologies is relevant when planning and teaching in EBP [ 13 , 20 ].

Interdisciplinary collaboration was described as relevant when planning teaching in EBP [ 13 , 20 ]. Specifically, regarding literature search Wakibi et al. found that collaboration between librarians, computer laboratory technicians and nurse educators enhanced students’ skills [ 13 ]. Also, in terms of creating transfer between EBP teaching and clinical practice, collaboration between faculty, library, clinical institutions, and teaching institutions was used [ 13 , 20 ].

Regarding collaboration with clinical practice, Ghaffari et al. found that teaching EBP integrated in clinical education could promote students’ knowledge and skills [ 25 ]. Horntvedt et al. found that during a six-week course in clinical practice, students obtained better skills in reading research articles and orally presenting the findings to staff and fellow students [ 20 ]. Participation in clinical research projects combined with instructions in analyzing and discussing research findings also “led to a positive approach and EBP knowledge” [ 20 ]. Moreover, reading research articles during the clinical practice period enhances the students critical thinking skills. Furthermore, Horntvedt et al. mention, that students found it meaningful to conduct a “mini” – research project in clinical settings, as the identified evidence became relevant [ 20 ].

Educational interventions

Educational interventions can be described as “Framing Interventions” understood as different ways to set up a framework for teaching EBP, and “ Teaching methods ” understood as specific methods used when teaching EBP.

Various educational interventions were described in most reviews [ 12 , 13 , 20 , 21 ]. According to Patelarou et al., no specific educational intervention regardless of framing and methods was in favor to “ increase knowledge, skills and competency as well as improve the beliefs, attitudes and behaviors of nursing students” [ 12 ].

Framing interventions

The approaches used to set up a framework for teaching EBP were labelled in different ways: programs, interactive teaching strategies, educational programs, courses etc. Approaches of various durations from hours to months were described as well as stepwise interventions [ 12 , 13 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 25 ].

Some frameworks [ 13 , 20 , 21 , 24 ] were based on the assessments categories described by the Sicily group [ 2 ] or based on theory [ 21 ] or as mentioned above clinically integrated [ 20 ]. Wakibi et al. identified interventions used to foster a spirit of inquiry and EBP culture reflecting the “5-step approach” of the Sicily group [ 4 ], asking PICOT questions, searching for best evidence, critical appraisal, integrating evidence with clinical expertise and patient preferences to make clinical decisions, evaluating outcomes of EBP practice, and disseminating outcomes useful [ 13 ]. Ramis et al. found that teaching interventions based on theory like Banduras self-efficacy or Roger’s theory of diffusion led to positive effects on students EBP knowledge and attitudes [ 21 ].

Teaching methods

A variety of teaching methods were used such as, lectures [ 12 , 13 , 20 ], problem-based learning [ 12 , 20 , 25 ], group work, discussions [ 12 , 13 ], and presentations [ 20 ] (see Table 2 ). The most effective method to achieve the skills required to practice EBP as described in the “5-step approach” by the Sicely group is a combination of different teaching methods like lectures, assignments, discussions, group works, and exams/tests.

Four systematic reviews identified such combinations or multifaceted approaches [ 12 , 13 , 20 , 21 ]. Patelarou et al. states that “EBP education approaches should be blended” [ 12 ]. Thus, combining the use of video, voice-over, PowerPoint, problem-based learning, lectures, team-based learning, projects, and small groups were found in different studies. This combination had shown “to be effective” [ 12 ]. Similarly, Horntvedt et al. found that nursing students reported that various teaching methods improved their EBP knowledge and skills [ 20 ].

According to Ghaffari et al., including problem-based learning in teaching plans “improved the clinical care and performance of the students”, while the problem-solving approach “promoted student knowledge” [ 25 ]. Other teaching methods identified, e.g., flipped classroom [ 20 ] and virtual simulation [ 12 , 20 ] were also characterized as useful interactive teaching interventions. Furthermore, face-to-face approaches seem “more effective” than online teaching interventions to enhance students’ research and appraisal skills and journal clubs enhance the students critically appraisal-skills [ 12 ].

As the reviews included in this overview primarily are based on qualitative, mixed methods as well as quasi-experimental studies and to a minor extent on randomized controlled trials (see Table 2 ) it is not possible to conclude of the most effective methods. However, a combination of methods and an innovative collaboration between librarians, information technology professionals and healthcare professionals seem the most effective approach to achieve EBP required skills.

EBP-related outcomes

Most of the systematic reviews presented a wide array of outcome assessments applied in EBP research (See Table 3 ). Analyzing the outcomes according to the Sicily group’s assessment categories revealed that assessing “knowledge” (used in 19 out of 39 primary studies), “skills” (used in 18 out of 39 primary studies) and “attitude” (used in 17 out of 39) were by far the most frequently used assessment categories, whereas outcomes within the category of “behaviors” (used in eight studies) “reaction to educational experience” (in five studies), “self-efficacy” (in two studies), and “benefits for the patient” (in one study), were used to a far lesser extent. Additionally, outcomes, that we were not able to categorize within the seven assessment categories, were “future use” and “Global EBP competence”.

The purpose of this overview of systematic reviews was to collect and summarize evidence of the diversity of EBP teaching interventions and outcomes measured among professional bachelor- degree healthcare students.

Our results give an overview of “the state of the art” of using and measuring EBP in PBHP education. However, the quality of included systematic reviews was rated critically low. Thus, the result cannot support guidelines of best practice.

The analysis of the interventions and outcomes described in the 39 primary studies included in this overview, reveals a wide variety of teaching methods and interventions being used and described in the scientific literature on EBP teaching of PBHP students. The results show some evidence of the five step EBP approach in accordance with the inclusion criteria “interventions aimed at teaching one or more of the five EBP steps; Ask, Search, Appraise, Integrate, Assess/evaluate”. Most authors state, that the students´ EBP skills, attitudes and knowledge improved by almost any of the described methods and interventions. However, descriptions of how the improvements were measured were less frequent.

We evaluated the described outcome measures and assessments according to the seven categories proposed by the Sicily group and found that most assessments were on “attitudes”, “skills” and “knowledge”, sometimes on “behaviors” and very seldom on” reaction to educational experience”, “self-efficacy” and “benefits to the patients”. To our knowledge no systematic review or overview has made this evaluation on outcome categories before, but Bala et al. [ 9 ] also stated that knowledge, skills, and attitudes are the most common evaluated effects.

Comparing the outcomes measured between mainly medical [ 9 ] and nursing students, the most prevalent outcomes in both groups are knowledge, skills and attitudes around EBP. In contrast, measuring on the students´ patient care or on the impact of the EBP teaching on benefits for the patients is less prevalent. In contrast Wu et al.’s systematic review shows that among clinical nurses, educational interventions supporting implementation of EBP projects can change patient outcomes positively. However, they also conclude that direct causal evidence of the educational interventions is difficult to measure because of the diversity of EBP projects implemented [ 26 ]. Regarding EBP behavior the Sicily group recommend this category to be assessed by monitoring the frequency of the five step EBP approach, e.g., ASK questions about patients, APPRAISE evidence related to patient care, EVALUATE their EBP behavior and identified areas for improvement [ 2 ]. The results also showed evidence of student-clinician transition. “Future use” was identified in two systematic reviews [ 12 , 13 ] and categorized as “others”. This outcome is not included in the seven Sicily categories. However, a systematic review of predictive modelling studies shows, that future use or the intention to use EBP after graduation are influenced by the students EBP familiarity, EBP capability beliefs, EBP attitudes and academic and clinical support [ 27 ].

Teaching and evaluating EBP needs to move beyond aiming at changes in knowledge, skills, and attitudes, but also start focusing on changing and assessing behavior, self-efficacy and benefit to the patients. We recommend doing this using validated tools for the assessment of outcomes and in prospective studies with longer follow-up periods, preferably evaluating the adoption of EBP in clinical settings bearing in mind, that best teaching practice happens across sectors and settings supported and supervised by multiple professions.

Based on a systematic review and international Delphi survey, a set of interprofessional EBP core competencies that details the competence content of each of the five steps has been published to inform curriculum development and benchmark EBP standards [ 28 ]. This consensus statement may be used by educators as a reference for both learning objectives and EBP content descriptions in future intervention research. The collaboration with clinical institutions and integration of EBP teaching components such as EBP assignments or participating in clinical research projects are important results. Specifically, in the light of the dialectic between theoretical and clinical education as a core characteristic of Professional bachelor-degree healthcare educations.

Our study has some limitations that need consideration when interpreting the results. A search in the EMBASE and Scopus databases was not added in the search strategy, although it might have been able to bring additional sources. Most of the 22 excluded reviews included primary studies among other levels/ healthcare groups of students or had not critically appraised their primary studies. This constitutes insufficient adherence to methodological guidelines for systematic reviews and limits the completeness of the reviews identified. Often, the result sections of the included reviews were poorly reported and made it necessary to extract some, but not always sufficient, information from the primary study abstracts. As the present study is an overview and not a new systematic review, we did not extract information from the result section in the primary studies. Thus, the comprehensiveness and applicability of the results of this overview are limited by the methodological limitations in the six included systematic reviews.

The existing evidence is based on different types of study designs. This heterogeneity is seen in all the included reviews. Thus, the present overview only conveys trends around the comparative effectiveness of the different ways to frame, or the methods used for teaching EBP. This can be seen as a weakness for the clarity and applicability of the overview results. Also, our protocol is unpublished, which may weaken the transparency of the overview approach, however our search strategies are available as additional material (see Additional file 1 ). In addition, the validity of data extraction can be discussed. We extracted data consecutively by the first and last author and if needed consensus was reached by discussion with the entire research group. This method might have been strengthened by using two blinded reviewers to extract data and present data with supporting kappa values.

The generalizability of the results of this overview is limited to undergraduate nursing students. Although, we consider it a strength that the results represent a broad international perspective on framing EBP teaching, as well as teaching methods and outcomes used among educators in EBP. Primary studies exist among occupational therapy and physiotherapy students [ 5 , 29 ] but have not been systematically synthesized. However, the evidence is almost non-existent among midwife, nutrition and health and biomedical laboratory science students. This has implications for further research efforts because evidence from within these student populations is paramount for future proofing the quality assurance of clinical evidence-based healthcare practice.

Another implication is the need to compare how to frame the EBP teaching, and the methods used both inter-and mono professionally among these professional bachelor-degree students. Lastly, we support the recommendations of Bala et al. of using validated tools to increase the focus on measuring behavior change in clinical practice and patient outcomes, and to report in accordance with the GREET guidelines for educational intervention studies [ 9 ].

This overview demonstrates a variety of approaches to promote EBP teaching among professional bachelor-degree healthcare students. Teaching EBP is based on collaboration with clinical practice and the use of different approaches to frame the teaching as well as different teaching methods. Furthermore, this overview has elucidated, that interventions often are evaluated according to changes in the student’s skills, knowledge and attitudes towards EBP, but very rarely on self-efficacy, behaviors, benefits to the patients or reaction to the educational experience as suggested by the Sicily group. This might indicate that educators need to move on to measure the effect of EBP on outcomes comprising all categories, which are important to enhance sustainable behavior and transition of knowledge into the context of practices where better healthcare education should have an impact. In our perspective these gaps in the EBP teaching are best met by focusing on more collaboration with clinical practice which is the context where the final endpoint of teaching EBP should be anchored and evaluated.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used an/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Evidence-Based Practice

Professional bachelor-degree healthcare programs

Mazurek Melnyk B, Fineout-Overholt E. Making the Case for Evidence-Based Practice and Cultivalting a Spirit of Inquiry. I: Mazurek Melnyk B, Fineout-Overholt E, redaktører. Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare A Guide to Best Practice. 4. ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2019. p. 7–32.

Tilson JK, Kaplan SL, Harris JL, Hutchinson A, Ilic D, Niederman R, et al. Sicily statement on classification and development of evidence-based practice learning assessment tools. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(78):1–10.

Google Scholar

Connor L, Dean J, McNett M, Tydings DM, Shrout A, Gorsuch PF, et al. Evidence-based practice improves patient outcomes and healthcare system return on investment: Findings from a scoping review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2023;20(1):6–15.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Dawes M, Summerskill W, Glasziou P, Cartabellotta N, Martin J, Hopayian K, et al. Sicily statement on evidence-based practice. BMC Med Educ. 2005;5(1):1–7.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Larsen CM, Terkelsen AS, Carlsen AF, Kristensen HK. Methods for teaching evidence-based practice: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):1–33.

Article CAS Google Scholar

World Health Organization. Nurse educator core competencies. 2016 https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/258713 Accessed 21 Mar 2023.

Saunders H, Gallagher-Ford L, Kvist T, Vehviläinen-Julkunen K. Practicing healthcare professionals’ evidence-based practice competencies: an overview of systematic reviews. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2019;16(3):176–85.

Young T, Rohwer A, Volmink J, Clarke M. What Are the Effects of Teaching Evidence-Based Health Care (EBHC)? Overview of Systematic Reviews PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):1–13.

Bala MM, Poklepović Peričić T, Zajac J, Rohwer A, Klugarova J, Välimäki M, et al. What are the effects of teaching Evidence-Based Health Care (EBHC) at different levels of health professions education? An updated overview of systematic reviews. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(7):1–28.

Article Google Scholar

Copenhagen University. Bachelor in medicine. 2024 https://studier.ku.dk/bachelor/medicin/undervisning-og-opbygning/ Accessed 31 Jan 2024.

Ministery of Higher Education and Science. Professional bachelor programmes. 2022 https://ufm.dk/en/education/higher-education/university-colleges/university-college-educations Accessed 31 Jan 2024.

Patelarou AE, Mechili EA, Ruzafa-Martinez M, Dolezel J, Gotlib J, Skela-Savič B, et al. Educational Interventions for Teaching Evidence-Based Practice to Undergraduate Nursing Students: A Scoping Review. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2020;17(17):1–24.

Wakibi S, Ferguson L, Berry L, Leidl D, Belton S. Teaching evidence-based nursing practice: a systematic review and convergent qualitative synthesis. J Prof Nurs. 2021;37(1):135–48.

Fiset VJ, Graham ID, Davies BL. Evidence-Based Practice in Clinical Nursing Education: A Scoping Review. J Nurs Educ. 2017;56(9):534–41.

Pollock M, Fernandes R, Becker L, Pieper D, Hartling L. Chapter V: Overviews of Reviews. I: Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M, et al., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 62. 2021 https://training.cochrane.org/handbook Accessed 31 Jan 2024.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, m.fl. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:1-9

Covidence. Covidence - Better systematic review management. https://www.covidence.org/ Accessed 31 Jan 2024.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;21(358):1–9.

Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical Appraisal Tools. https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools Accessed 31 Jan 2024.

Horntvedt MT, Nordsteien A, Fermann T, Severinsson E. Strategies for teaching evidence-based practice in nursing education: a thematic literature review. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):1–11.

Ramis M-A, Chang A, Conway A, Lim D, Munday J, Nissen L. Theory-based strategies for teaching evidence-based practice to undergraduate health students: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):1–13.

Rethlefsen ML, Kirtley S, Waffenschmidt S, Ayala AP, Moher D, Page MJ, et al. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):1–19.

Song CE, Jang A. Simulation design for improvement of undergraduate nursing students’ experience of evidence-based practice: a scoping-review protocol. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(11):1–6.

Cui C, Li Y, Geng D, Zhang H, Jin C. The effectiveness of evidence-based nursing on development of nursing students’ critical thinking: A meta-analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;65:46–53.

Ghaffari R, Shapoori S, Binazir MB, Heidari F, Behshid M. Effectiveness of teaching evidence-based nursing to undergraduate nursing students in Iran: a systematic review. Res Dev Med Educ. 2018;7(1):8–13.

Wu Y, Brettle A, Zhou C, Ou J, Wang Y, Wang S. Do educational interventions aimed at nurses to support the implementation of evidence-based practice improve patient outcomes? A systematic review. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;70:109–14.

Ramis MA, Chang A, Nissen L. Undergraduate health students’ intention to use evidence-based practice after graduation: a systematic review of predictive modeling studies. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2018;15(2):140–8.

Albarqouni L, Hoffmann T, Straus S, Olsen NR, Young T, Ilic D, et al. Core competencies in evidence-based practice for health professionals: consensus statement based on a systematic review and Delphi survey. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(2):1–12.

Hitch D, Nicola-Richmond K. Instructional practices for evidence-based practice with pre-registration allied health students: a review of recent research and developments. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pr. 2017;22(4):1031–45.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge research librarian Rasmus Sand for competent support in the development of literature search strategies.

This work was supported by the University College of South Denmark, which was not involved in the conduct of this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Nursing Education & Department for Applied Health Science, University College South Denmark, Degnevej 17, 6705, Esbjerg Ø, Denmark

Lea D. Nielsen

Department of Oncology, Hospital of Lillebaelt, Beriderbakken 4, 7100, Vejle, Denmark

Mette M. Løwe

Biomedical Laboratory Science & Department for Applied Health Science, University College South Denmark, Degnevej 17, 6705, Esbjerg Ø, Denmark

Francisco Mansilla

Physiotherapy Education & Department for Applied Health Science, University College South Denmark, Degnevej 17, 6705, Esbjerg Ø, Denmark

Rene B. Jørgensen

Occupational Therapy Education & Department for Applied Health Science, University College South Denmark, Degnevej 17, 6705, Esbjerg Ø, Denmark

Asviny Ramachandran

Department for Applied Health Science, University College South Denmark, Degnevej 17, 6705, Esbjerg Ø, Denmark

Bodil B. Noe

Centre for Clinical Research and Prevention, Section for Health Promotion and Prevention, Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg Hospital, Nordre Fasanvej 57, 2000, Frederiksberg, Denmark

Heidi K. Egebæk

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing the main manuscript, preparing figures and tables and revising the manuscripts.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lea D. Nielsen .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary material 1., supplementary material 2., supplementary material 3., supplementary material 4., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Nielsen, L.D., Løwe, M.M., Mansilla, F. et al. Interventions, methods and outcome measures used in teaching evidence-based practice to healthcare students: an overview of systematic reviews. BMC Med Educ 24 , 306 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05259-8

Download citation

Received : 29 May 2023

Accepted : 04 March 2024

Published : 19 March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05259-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- MH "Students, Health occupations+"

- MH "Students, occupational therapy"

- MH "Students, physical therapy"

- MH "Students, Midwifery"

- “Students, Nursing"[Mesh]

- “Teaching"[Mesh]

- MH "Teaching methods+"

- "Evidence-based practice"[Mesh]

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Working with sources

- What Is Critical Thinking? | Definition & Examples

What Is Critical Thinking? | Definition & Examples

Published on May 30, 2022 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on May 31, 2023.

Critical thinking is the ability to effectively analyze information and form a judgment .

To think critically, you must be aware of your own biases and assumptions when encountering information, and apply consistent standards when evaluating sources .

Critical thinking skills help you to:

- Identify credible sources

- Evaluate and respond to arguments

- Assess alternative viewpoints

- Test hypotheses against relevant criteria

Table of contents

Why is critical thinking important, critical thinking examples, how to think critically, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about critical thinking.

Critical thinking is important for making judgments about sources of information and forming your own arguments. It emphasizes a rational, objective, and self-aware approach that can help you to identify credible sources and strengthen your conclusions.

Critical thinking is important in all disciplines and throughout all stages of the research process . The types of evidence used in the sciences and in the humanities may differ, but critical thinking skills are relevant to both.

In academic writing , critical thinking can help you to determine whether a source:

- Is free from research bias

- Provides evidence to support its research findings

- Considers alternative viewpoints

Outside of academia, critical thinking goes hand in hand with information literacy to help you form opinions rationally and engage independently and critically with popular media.

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

Critical thinking can help you to identify reliable sources of information that you can cite in your research paper . It can also guide your own research methods and inform your own arguments.

Outside of academia, critical thinking can help you to be aware of both your own and others’ biases and assumptions.

Academic examples

However, when you compare the findings of the study with other current research, you determine that the results seem improbable. You analyze the paper again, consulting the sources it cites.

You notice that the research was funded by the pharmaceutical company that created the treatment. Because of this, you view its results skeptically and determine that more independent research is necessary to confirm or refute them. Example: Poor critical thinking in an academic context You’re researching a paper on the impact wireless technology has had on developing countries that previously did not have large-scale communications infrastructure. You read an article that seems to confirm your hypothesis: the impact is mainly positive. Rather than evaluating the research methodology, you accept the findings uncritically.

Nonacademic examples

However, you decide to compare this review article with consumer reviews on a different site. You find that these reviews are not as positive. Some customers have had problems installing the alarm, and some have noted that it activates for no apparent reason.

You revisit the original review article. You notice that the words “sponsored content” appear in small print under the article title. Based on this, you conclude that the review is advertising and is therefore not an unbiased source. Example: Poor critical thinking in a nonacademic context You support a candidate in an upcoming election. You visit an online news site affiliated with their political party and read an article that criticizes their opponent. The article claims that the opponent is inexperienced in politics. You accept this without evidence, because it fits your preconceptions about the opponent.

There is no single way to think critically. How you engage with information will depend on the type of source you’re using and the information you need.

However, you can engage with sources in a systematic and critical way by asking certain questions when you encounter information. Like the CRAAP test , these questions focus on the currency , relevance , authority , accuracy , and purpose of a source of information.

When encountering information, ask:

- Who is the author? Are they an expert in their field?

- What do they say? Is their argument clear? Can you summarize it?

- When did they say this? Is the source current?

- Where is the information published? Is it an academic article? Is it peer-reviewed ?

- Why did the author publish it? What is their motivation?

- How do they make their argument? Is it backed up by evidence? Does it rely on opinion, speculation, or appeals to emotion ? Do they address alternative arguments?

Critical thinking also involves being aware of your own biases, not only those of others. When you make an argument or draw your own conclusions, you can ask similar questions about your own writing:

- Am I only considering evidence that supports my preconceptions?

- Is my argument expressed clearly and backed up with credible sources?

- Would I be convinced by this argument coming from someone else?

If you want to know more about ChatGPT, AI tools , citation , and plagiarism , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- ChatGPT vs human editor

- ChatGPT citations

- Is ChatGPT trustworthy?

- Using ChatGPT for your studies

- What is ChatGPT?

- Chicago style

- Paraphrasing

Plagiarism

- Types of plagiarism

- Self-plagiarism

- Avoiding plagiarism

- Academic integrity

- Consequences of plagiarism

- Common knowledge

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

Critical thinking skills include the ability to:

You can assess information and arguments critically by asking certain questions about the source. You can use the CRAAP test , focusing on the currency , relevance , authority , accuracy , and purpose of a source of information.

Ask questions such as:

- Who is the author? Are they an expert?

- How do they make their argument? Is it backed up by evidence?

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

Information literacy refers to a broad range of skills, including the ability to find, evaluate, and use sources of information effectively.

Being information literate means that you:

- Know how to find credible sources

- Use relevant sources to inform your research

- Understand what constitutes plagiarism

- Know how to cite your sources correctly

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search, interpret, and recall information in a way that aligns with our pre-existing values, opinions, or beliefs. It refers to the ability to recollect information best when it amplifies what we already believe. Relatedly, we tend to forget information that contradicts our opinions.

Although selective recall is a component of confirmation bias, it should not be confused with recall bias.

On the other hand, recall bias refers to the differences in the ability between study participants to recall past events when self-reporting is used. This difference in accuracy or completeness of recollection is not related to beliefs or opinions. Rather, recall bias relates to other factors, such as the length of the recall period, age, and the characteristics of the disease under investigation.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Ryan, E. (2023, May 31). What Is Critical Thinking? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 20, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/working-with-sources/critical-thinking/

Is this article helpful?

Eoghan Ryan

Other students also liked, student guide: information literacy | meaning & examples, what are credible sources & how to spot them | examples, applying the craap test & evaluating sources, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- How to apply critical thinking in learning

Sometimes your university classes might feel like a maze of information. Consider critical thinking skills like a map that can lead the way.

Why do we need critical thinking?

Critical thinking is a type of thinking that requires continuous questioning, exploring answers, and making judgments. Critical thinking can help you:

- analyze information to comprehend more thoroughly

- approach problems systematically, identify root causes, and explore potential solutions

- make informed decisions by weighing various perspectives

- promote intellectual curiosity and self-reflection, leading to continuous learning, innovation, and personal development

What is the process of critical thinking?

1. understand .

Critical thinking starts with understanding the content that you are learning.

This step involves clarifying the logic and interrelations of the content by actively engaging with the materials (e.g., text, articles, and research papers). You can take notes, highlight key points, and make connections with prior knowledge to help you engage.

Ask yourself these questions to help you build your understanding:

- What is the structure?

- What is the main idea of the content?

- What is the evidence that supports any arguments?

- What is the conclusion?

2. Analyze

You need to assess the credibility, validity, and relevance of the information presented in the content. Consider the authors’ biases and potential limitations in the evidence.

Ask yourself questions in terms of why and how:

- What is the supporting evidence?

- Why do they use it as evidence?

- How does the data present support the conclusions?

- What method was used? Was it appropriate?

3. Evaluate

After analyzing the data and evidence you collected, make your evaluation of the evidence, results, and conclusions made in the content.

Consider the weaknesses and strengths of the ideas presented in the content to make informed decisions or suggest alternative solutions:

- What is the gap between the evidence and the conclusion?

- What is my position on the subject?

- What other approaches can I use?

When do you apply critical thinking and how can you improve these skills?

1. reading academic texts, articles, and research papers.

- analyze arguments

- assess the credibility and validity of evidence

- consider potential biases presented

- question the assumptions, methodologies, and the way they generate conclusions

2. Writing essays and theses

- demonstrate your understanding of the information, logic of evidence, and position on the topic

- include evidence or examples to support your ideas

- make your standing points clear by presenting information and providing reasons to support your arguments

- address potential counterarguments or opposing viewpoints

- explain why your perspective is more compelling than the opposing viewpoints

3. Attending lectures

- understand the content by previewing, active listening , and taking notes

- analyze your lecturer’s viewpoints by seeking whether sufficient data and resources are provided

- think about whether the ideas presented by the lecturer align with your values and beliefs

- talk about other perspectives with peers in discussions

Related blog posts

- A beginner's guide to successful labs

- A beginner's guide to note-taking

- 5 steps to get the most out of your next reading

- How do you create effective study questions?

- An epic approach to problem-based test questions

Recent blog posts

Blog topics.

- assignments (1)

- Graduate (2)

- Learning support (25)

- note-taking and reading (6)

- organizations (1)

- tests and exams (8)

- time management (3)

- Tips from students (6)

- undergraduate (27)

- university learning (10)

Blog posts by audience

- Current undergraduate students (27)

- Current graduate students (3)

- Future undergraduate students (9)

- Future graduate students (1)

Blog posts archive

- December (1)

- November (6)

- October (8)

- August (10)

Contact the Student Success Office

South Campus Hall, second floor University of Waterloo 519-888-4567 ext. 84410

Immigration Consulting

Book a same-day appointment on Portal or submit an online inquiry to receive immigration support.

Request an authorized leave from studies for immigration purposes.

Quick links

Current student resources

SSO staff links

Employment and volunteer opportunities

- Contact Waterloo

- Maps & Directions

- Accessibility

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations .

Academic Skills

- Academic Skills Home

- Learning Preference

- Identifying and Leveraging your Support Systems

- Critical Thinking Skills

Defining Critical Thinking

Blooms taxonomy, student experience feedback buttons.

- Professional Communication

- Achieving Balance: Structure and schedule

- Time Management

- Overcoming Coursework Challenges

- Taking Ownership of your Success

- Success Tips from your AFA

- Utilizing Faculty Feedback

- ASC Writing Resources Guide This link opens in a new window

- Academic Integrity Basics

- Academic Integrity Violation (AIV) and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Self Plagiarism

- Academic Integrity Checklist

- Turnitin and Draft Coach

- Organization and Format

- Reviewing, Revising, Proofreading and Editing

- NU Library Research Process Guide This link opens in a new window

“Critical thinking relies on content, because you can't navigate masses of information if you have nothing to navigate to.” -Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Professor of Psychology, Temple University