How to Write the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay (With Example)

November 27, 2023

Feeling intimidated by the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay? We’re here to help demystify. Whether you’re cramming for the AP Lang exam right now or planning to take the test down the road, we’ve got crucial rubric information, helpful tips, and an essay example to prepare you for the big day. This post will cover 1) What is the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay? 2) AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Rubric 3) AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis: Sample Prompt 4) AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example 5)AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example: Why It Works

What is the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay?

The AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay is one of three essays included in the written portion of the AP English Exam. The full AP English Exam is 3 hours and 15 minutes long, with the first 60 minutes dedicated to multiple-choice questions. Once you complete the multiple-choice section, you move on to three equally weighted essays that ask you to synthesize, analyze, and interpret texts and develop well-reasoned arguments. The three essays include:

Synthesis essay: You’ll review various pieces of evidence and then write an essay that synthesizes (aka combines and interprets) the evidence and presents a clear argument. Read our write up on How to Write the AP Lang Synthesis Essay here.

Argumentative essay: You’ll take a stance on a specific topic and argue your case.

Rhetorical essay: You’ll read a provided passage, then analyze the author’s rhetorical choices and develop an argument that explains why the author made those rhetorical choices.

AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Rubric

The AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay is graded on just 3 rubric categories: Thesis, Evidence and Commentary, and Sophistication . At a glance, the rubric categories may seem vague, but AP exam graders are actually looking for very particular things in each category. We’ll break it down with dos and don’ts for each rubric category:

Thesis (0-1 point)

There’s nothing nebulous when it comes to grading AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay thesis. You either have one or you don’t. Including a thesis gets you one point closer to a high score and leaving it out means you miss out on one crucial point. So, what makes a thesis that counts?

- Make sure your thesis argues something about the author’s rhetorical choices. Making an argument means taking a risk and offering your own interpretation of the provided text. This is an argument that someone else might disagree with.

- A good test to see if you have a thesis that makes an argument. In your head, add the phrase “I think that…” to the beginning of your thesis. If what follows doesn’t logically flow after that phrase (aka if what follows isn’t something you and only you think), it’s likely you’re not making an argument.

- Avoid a thesis that merely restates the prompt.

- Avoid a thesis that summarizes the text but does not make an argument.

Evidence and Commentary (0-4 points)

This rubric category is graded on a scale of 0-4 where 4 is the highest grade. Per the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis rubric, to get a 4, you’ll want to:

- Include lots of specific evidence from the text. There is no set golden number of quotes to include, but you’ll want to make sure you’re incorporating more than a couple pieces of evidence that support your argument about the author’s rhetorical choices.

- Make sure you include more than one type of evidence, too. Let’s say you’re working on your essay and have gathered examples of alliteration to include as supporting evidence. That’s just one type of rhetorical choice, and it’s hard to make a credible argument if you’re only looking at one type of evidence. To fix that issue, reread the text again looking for patterns in word choice and syntax, meaningful figurative language and imagery, literary devices, and other rhetorical choices, looking for additional types of evidence to support your argument.

- After you include evidence, offer your own interpretation and explain how this evidence proves the point you make in your thesis.

- Don’t summarize or speak generally about the author and the text. Everything you write must be backed up with evidence.

- Don’t let quotes speak for themselves. After every piece of evidence you include, make sure to explain your interpretation. Also, connect the evidence to your overarching argument.

Sophistication (0-1 point)

In this case, sophistication isn’t about how many fancy vocabulary words or how many semicolons you use. According to College Board , one point can be awarded to AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis essays that “demonstrate sophistication of thought and/or a complex understanding of the rhetorical situation” in any of these three ways:

- Explaining the significance or relevance of the writer’s rhetorical choices.

- Explaining the purpose or function of the passage’s complexities or tensions.

- Employing a style that is consistently vivid and persuasive.

Note that you don’t have to achieve all three to earn your sophistication point. A good way to think of this rubric category is to consider it a bonus point that you can earn for going above and beyond in depth of analysis or by writing an especially persuasive, clear, and well-structured essay. In order to earn this point, you’ll need to first do a good job with your thesis, evidence, and commentary.

- Focus on nailing an argumentative thesis and multiple types of evidence. Getting these fundamentals of your essay right will set you up for achieving depth of analysis.

- Explain how each piece of evidence connects to your thesis.

- Spend a minute outlining your essay before you begin to ensure your essay flows in a clear and cohesive way.

- Steer clear of generalizations about the author or text.

- Don’t include arguments you can’t prove with evidence from the text.

- Avoid complex sentences and fancy vocabulary words unless you use them often. Long, clunky sentences with imprecisely used words are hard to follow.

AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis: Sample Prompt

The sample prompt below is published online by College Board and is a real example from the 2021 AP Exam. The prompt provides background context, essay instructions, and the text you need to analyze. For sake of space, we’ve included the text as an image you can click to read. After the prompt, we provide a sample high scoring essay and then explain why this AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis essay example works.

Suggested time—40 minutes.

(This question counts as one-third of the total essay section score.)

On February 27, 2013, while in office, former president Barack Obama delivered the following address dedicating the Rosa Parks statue in the National Statuary Hall of the United States Capitol building. Rosa Parks was an African American civil rights activist who was arrested in 1955 for refusing to give up her seat on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Read the passage carefully. Write an essay that analyzes the rhetorical choices Obama makes to convey his message.

In your response you should do the following:

- Respond to the prompt with a thesis that analyzes the writer’s rhetorical choices.

- Select and use evidence to support your line of reasoning.

- Explain how the evidence supports your line of reasoning.

- Demonstrate an understanding of the rhetorical situation.

- Use appropriate grammar and punctuation in communicating your argument.

AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example

In his speech delivered in 2013 at the dedication of Rosa Park’s statue, President Barack Obama acknowledges everything that Parks’ activism made possible in the United States. Telling the story of Parks’ life and achievements, Obama highlights the fact that Parks was a regular person whose actions accomplished enormous change during the civil rights era. Through the use of diction that portrays Parks as quiet and demure, long lists that emphasize the extent of her impacts, and Biblical references, Obama suggests that all of us are capable of achieving greater good, just as Parks did.

Although it might be a surprising way to start to his dedication, Obama begins his speech by telling us who Parks was not: “Rosa Parks held no elected office. She possessed no fortune” he explains in lines 1-2. Later, when he tells the story of the bus driver who threatened to have Parks arrested when she refused to get off the bus, he explains that Parks “simply replied, ‘You may do that’” (lines 22-23). Right away, he establishes that Parks was a regular person who did not hold a seat of power. Her protest on the bus was not part of a larger plan, it was a simple response. By emphasizing that Parks was not powerful, wealthy, or loud spoken, he implies that Parks’ style of activism is an everyday practice that all of us can aspire to.

AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example (Continued)

Even though Obama portrays Parks as a demure person whose protest came “simply” and naturally, he shows the importance of her activism through long lists of ripple effects. When Parks challenged her arrest, Obama explains, Martin Luther King, Jr. stood with her and “so did thousands of Montgomery, Alabama commuters” (lines 27-28). They began a boycott that included “teachers and laborers, clergy and domestics, through rain and cold and sweltering heat, day after day, week after week, month after month, walking miles if they had to…” (lines 28-31). In this section of the speech, Obama’s sentences grow longer and he uses lists to show that Parks’ small action impacted and inspired many others to fight for change. Further, listing out how many days, weeks, and months the boycott lasted shows how Parks’ single act of protest sparked a much longer push for change.

To further illustrate Parks’ impact, Obama incorporates Biblical references that emphasize the importance of “that single moment on the bus” (lines 57-58). In lines 33-35, Obama explains that Parks and the other protestors are “driven by a solemn determination to affirm their God-given dignity” and he also compares their victory to the fall the “ancient walls of Jericho” (line 43). By of including these Biblical references, Obama suggests that Parks’ action on the bus did more than correct personal or political wrongs; it also corrected moral and spiritual wrongs. Although Parks had no political power or fortune, she was able to restore a moral balance in our world.

Toward the end of the speech, Obama states that change happens “not mainly through the exploits of the famous and the powerful, but through the countless acts of often anonymous courage and kindness” (lines 78-81). Through carefully chosen diction that portrays her as a quiet, regular person and through lists and Biblical references that highlight the huge impacts of her action, Obama illustrates exactly this point. He wants us to see that, just like Parks, the small and meek can change the world for the better.

AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example: Why It Works

We would give the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis essay above a score of 6 out of 6 because it fully satisfies the essay’s 3 rubric categories: Thesis, Evidence and Commentary, and Sophistication . Let’s break down what this student did:

The thesis of this essay appears in the last line of the first paragraph:

“ Through the use of diction that portrays Parks as quiet and demure, long lists that emphasize the extent of her impacts, and Biblical references, Obama suggests that all of us are capable of achieving greater good, just as Parks did .”

This student’s thesis works because they make a clear argument about Obama’s rhetorical choices. They 1) list the rhetorical choices that will be analyzed in the rest of the essay (the italicized text above) and 2) include an argument someone else might disagree with (the bolded text above).

Evidence and Commentary:

This student includes substantial evidence and commentary. Things they do right, per the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis rubric:

- They include lots of specific evidence from the text in the form of quotes.

- They incorporate 3 different types of evidence (diction, long lists, Biblical references).

- After including evidence, they offer an interpretation of what the evidence means and explain how the evidence contributes to their overarching argument (aka their thesis).

Sophistication

This essay achieves sophistication according to the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis essay rubric in a few key ways:

- This student provides an introduction that flows naturally into the topic their essay will discuss. Before they get to their thesis, they tell us that Obama portrays Parks as a “regular person” setting up their main argument: Obama wants all regular people to aspire to do good in the world just as Rosa Parks did.

- They organize evidence and commentary in a clear and cohesive way. Each body paragraph focuses on just one type of evidence.

- They explain how their evidence is significant. In the final sentence of each body paragraph, they draw a connection back to the overarching argument presented in the thesis.

- All their evidence supports the argument presented in their thesis. There is no extraneous evidence or misleading detail.

- They consider nuances in the text. Rather than taking the text at face value, they consider what Obama’s rhetorical choices imply and offer their own unique interpretation of those implications.

- In their final paragraph, they come full circle, reiterate their thesis, and explain what Obama’s rhetorical choices communicate to readers.

- Their sentences are clear and easy to read. There are no grammar errors or misused words.

AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay—More Resources

Looking for more tips to help your master your AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay? Brush up on 20 Rhetorical Devices High School Students Should Know and read our Tips for Improving Reading Comprehension . If you’re ready to start studying for another part of the AP English Exam, find more expert tips in our How to Write the AP Lang Synthesis blog post.

Considering what other AP classes to take? Read up on the Hardest AP Classes .

- High School Success

Christina Wood

Christina Wood holds a BA in Literature & Writing from UC San Diego, an MFA in Creative Writing from Washington University in St. Louis, and is currently a Doctoral Candidate in English at the University of Georgia, where she teaches creative writing and first-year composition courses. Christina has published fiction and nonfiction in numerous publications, including The Paris Review , McSweeney’s , Granta , Virginia Quarterly Review , The Sewanee Review , Mississippi Review , and Puerto del Sol , among others. Her story “The Astronaut” won the 2018 Shirley Jackson Award for short fiction and received a “Distinguished Stories” mention in the 2019 Best American Short Stories anthology.

- 2-Year Colleges

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Best Colleges by State

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Essay

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High Schools

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Private High School Spotlight

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

I am a... Student Student Parent Counselor Educator Other First Name Last Name Email Address Zip Code Area of Interest Business Computer Science Engineering Fine/Performing Arts Humanities Mathematics STEM Pre-Med Psychology Social Studies/Sciences Submit

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Using Rhetorical Strategies for Persuasion

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

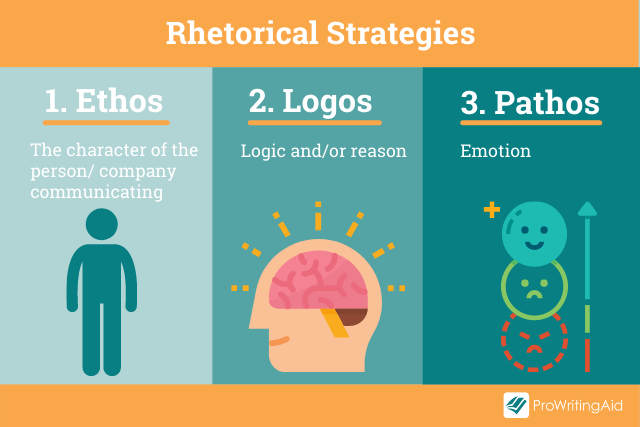

There are three types of rhetorical appeals, or persuasive strategies, used in arguments to support claims and respond to opposing arguments. A good argument will generally use a combination of all three appeals to make its case.

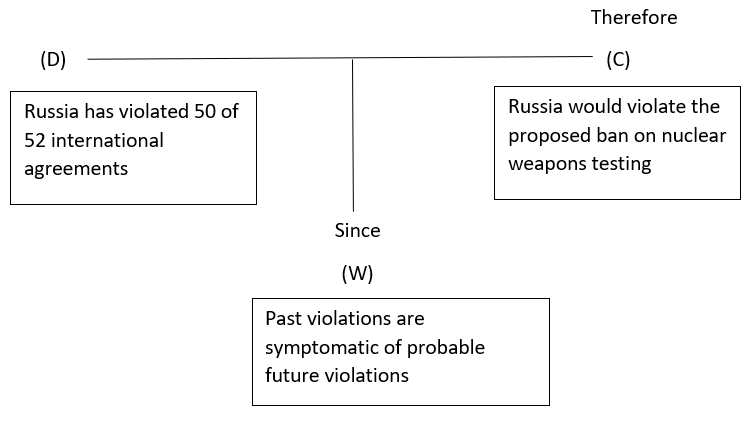

Logos or the appeal to reason relies on logic or reason. Logos often depends on the use of inductive or deductive reasoning.

Inductive reasoning takes a specific representative case or facts and then draws generalizations or conclusions from them. Inductive reasoning must be based on a sufficient amount of reliable evidence. In other words, the facts you draw on must fairly represent the larger situation or population. Example:

In this example the specific case of fair trade agreements with coffee producers is being used as the starting point for the claim. Because these agreements have worked the author concludes that it could work for other farmers as well.

Deductive reasoning begins with a generalization and then applies it to a specific case. The generalization you start with must have been based on a sufficient amount of reliable evidence.Example:

In this example the author starts with a large claim, that genetically modified seeds have been problematic everywhere, and from this draws the more localized or specific conclusion that Mexico will be affected in the same way.

Avoid Logical Fallacies

These are some common errors in reasoning that will undermine the logic of your argument. Also, watch out for these slips in other people's arguments.

Slippery slope: This is a conclusion based on the premise that if A happens, then eventually through a series of small steps, through B, C,..., X, Y, Z will happen, too, basically equating A and Z. So, if we don't want Z to occur A must not be allowed to occur either. Example:

In this example the author is equating banning Hummers with banning all cars, which is not the same thing.

Hasty Generalization: This is a conclusion based on insufficient or biased evidence. In other words, you are rushing to a conclusion before you have all the relevant facts. Example:

In this example the author is basing their evaluation of the entire course on only one class, and on the first day which is notoriously boring and full of housekeeping tasks for most courses. To make a fair and reasonable evaluation the author must attend several classes, and possibly even examine the textbook, talk to the professor, or talk to others who have previously finished the course in order to have sufficient evidence to base a conclusion on.

Post hoc ergo propter hoc: This is a conclusion that assumes that if 'A' occurred after 'B' then 'B' must have caused 'A.' Example:

In this example the author assumes that if one event chronologically follows another the first event must have caused the second. But the illness could have been caused by the burrito the night before, a flu bug that had been working on the body for days, or a chemical spill across campus. There is no reason, without more evidence, to assume the water caused the person to be sick.

Genetic Fallacy: A conclusion is based on an argument that the origins of a person, idea, institute, or theory determine its character, nature, or worth. Example:

In this example the author is equating the character of a car with the character of the people who built the car.

Begging the Claim: The conclusion that the writer should prove is validated within the claim. Example:

Arguing that coal pollutes the earth and thus should be banned would be logical. But the very conclusion that should be proved, that coal causes enough pollution to warrant banning its use, is already assumed in the claim by referring to it as "filthy and polluting."

Circular Argument: This restates the argument rather than actually proving it. Example:

In this example the conclusion that Bush is a "good communicator" and the evidence used to prove it "he speaks effectively" are basically the same idea. Specific evidence such as using everyday language, breaking down complex problems, or illustrating his points with humorous stories would be needed to prove either half of the sentence.

Either/or: This is a conclusion that oversimplifies the argument by reducing it to only two sides or choices. Example:

In this example where two choices are presented as the only options, yet the author ignores a range of choices in between such as developing cleaner technology, car sharing systems for necessities and emergencies, or better community planning to discourage daily driving.

Ad hominem: This is an attack on the character of a person rather than their opinions or arguments. Example:

In this example the author doesn't even name particular strategies Green Peace has suggested, much less evaluate those strategies on their merits. Instead, the author attacks the characters of the individuals in the group.

Ad populum: This is an emotional appeal that speaks to positive (such as patriotism, religion, democracy) or negative (such as terrorism or fascism) concepts rather than the real issue at hand. Example:

In this example the author equates being a "true American," a concept that people want to be associated with, particularly in a time of war, with allowing people to buy any vehicle they want even though there is no inherent connection between the two.

Red Herring: This is a diversionary tactic that avoids the key issues, often by avoiding opposing arguments rather than addressing them. Example:

In this example the author switches the discussion away from the safety of the food and talks instead about an economic issue, the livelihood of those catching fish. While one issue may affect the other, it does not mean we should ignore possible safety issues because of possible economic consequences to a few individuals.

Ethos or the ethical appeal is based on the character, credibility, or reliability of the writer. There are many ways to establish good character and credibility as an author:

- Use only credible, reliable sources to build your argument and cite those sources properly.

- Respect the reader by stating the opposing position accurately.

- Establish common ground with your audience. Most of the time, this can be done by acknowledging values and beliefs shared by those on both sides of the argument.

- If appropriate for the assignment, disclose why you are interested in this topic or what personal experiences you have had with the topic.

- Organize your argument in a logical, easy to follow manner. You can use the Toulmin method of logic or a simple pattern such as chronological order, most general to most detailed example, earliest to most recent example, etc.

- Proofread the argument. Too many careless grammar mistakes cast doubt on your character as a writer.

Pathos , or emotional appeal, appeals to an audience's needs, values, and emotional sensibilities. Pathos can also be understood as an appeal to audience's disposition to a topic, evidence, or argument (especially appropriate to academic discourse).

Argument emphasizes reason, but used properly there is often a place for emotion as well. Emotional appeals can use sources such as interviews and individual stories to paint a more legitimate and moving picture of reality or illuminate the truth. For example, telling the story of a single child who has been abused may make for a more persuasive argument than simply the number of children abused each year because it would give a human face to the numbers. Academic arguments in particular benefit from understanding pathos as appealing to an audience's academic disposition.

Only use an emotional appeal if it truly supports the claim you are making, not as a way to distract from the real issues of debate. An argument should never use emotion to misrepresent the topic or frighten people.

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

What Is a Rhetorical Analysis and How to Write a Great One

Helly Douglas

Do you have to write a rhetorical analysis essay? Fear not! We’re here to explain exactly what rhetorical analysis means, how you should structure your essay, and give you some essential “dos and don’ts.”

What is a Rhetorical Analysis Essay?

How do you write a rhetorical analysis, what are the three rhetorical strategies, what are the five rhetorical situations, how to plan a rhetorical analysis essay, creating a rhetorical analysis essay, examples of great rhetorical analysis essays, final thoughts.

A rhetorical analysis essay studies how writers and speakers have used words to influence their audience. Think less about the words the author has used and more about the techniques they employ, their goals, and the effect this has on the audience.

In your analysis essay, you break a piece of text (including cartoons, adverts, and speeches) into sections and explain how each part works to persuade, inform, or entertain. You’ll explore the effectiveness of the techniques used, how the argument has been constructed, and give examples from the text.

A strong rhetorical analysis evaluates a text rather than just describes the techniques used. You don’t include whether you personally agree or disagree with the argument.

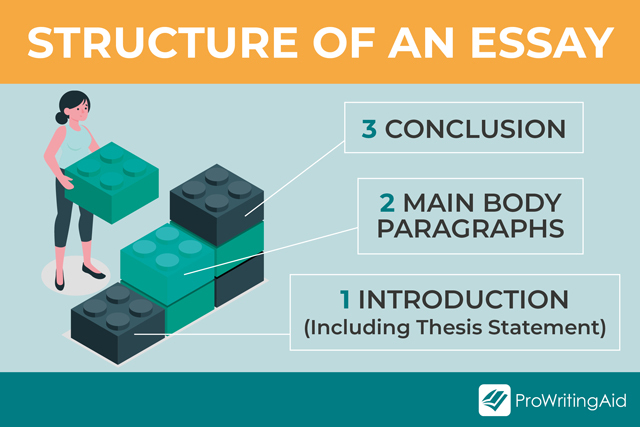

Structure a rhetorical analysis in the same way as most other types of academic essays . You’ll have an introduction to present your thesis, a main body where you analyze the text, which then leads to a conclusion.

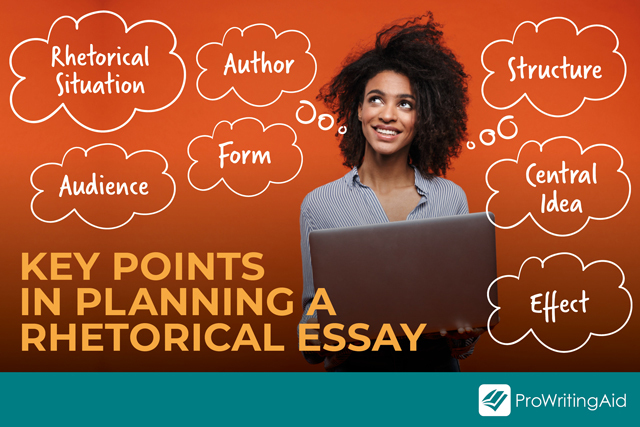

Think about how the writer (also known as a rhetor) considers the situation that frames their communication:

- Topic: the overall purpose of the rhetoric

- Audience: this includes primary, secondary, and tertiary audiences

- Purpose: there are often more than one to consider

- Context and culture: the wider situation within which the rhetoric is placed

Back in the 4th century BC, Aristotle was talking about how language can be used as a means of persuasion. He described three principal forms —Ethos, Logos, and Pathos—often referred to as the Rhetorical Triangle . These persuasive techniques are still used today.

Rhetorical Strategy 1: Ethos

Are you more likely to buy a car from an established company that’s been an important part of your community for 50 years, or someone new who just started their business?

Reputation matters. Ethos explores how the character, disposition, and fundamental values of the author create appeal, along with their expertise and knowledge in the subject area.

Aristotle breaks ethos down into three further categories:

- Phronesis: skills and practical wisdom

- Arete: virtue

- Eunoia: goodwill towards the audience

Ethos-driven speeches and text rely on the reputation of the author. In your analysis, you can look at how the writer establishes ethos through both direct and indirect means.

Rhetorical Strategy 2: Pathos

Pathos-driven rhetoric hooks into our emotions. You’ll often see it used in advertisements, particularly by charities wanting you to donate money towards an appeal.

Common use of pathos includes:

- Vivid description so the reader can imagine themselves in the situation

- Personal stories to create feelings of empathy

- Emotional vocabulary that evokes a response

By using pathos to make the audience feel a particular emotion, the author can persuade them that the argument they’re making is compelling.

Rhetorical Strategy 3: Logos

Logos uses logic or reason. It’s commonly used in academic writing when arguments are created using evidence and reasoning rather than an emotional response. It’s constructed in a step-by-step approach that builds methodically to create a powerful effect upon the reader.

Rhetoric can use any one of these three techniques, but effective arguments often appeal to all three elements.

The rhetorical situation explains the circumstances behind and around a piece of rhetoric. It helps you think about why a text exists, its purpose, and how it’s carried out.

The rhetorical situations are:

- 1) Purpose: Why is this being written? (It could be trying to inform, persuade, instruct, or entertain.)

- 2) Audience: Which groups or individuals will read and take action (or have done so in the past)?

- 3) Genre: What type of writing is this?

- 4) Stance: What is the tone of the text? What position are they taking?

- 5) Media/Visuals: What means of communication are used?

Understanding and analyzing the rhetorical situation is essential for building a strong essay. Also think about any rhetoric restraints on the text, such as beliefs, attitudes, and traditions that could affect the author's decisions.

Before leaping into your essay, it’s worth taking time to explore the text at a deeper level and considering the rhetorical situations we looked at before. Throw away your assumptions and use these simple questions to help you unpick how and why the text is having an effect on the audience.

1: What is the Rhetorical Situation?

- Why is there a need or opportunity for persuasion?

- How do words and references help you identify the time and location?

- What are the rhetoric restraints?

- What historical occasions would lead to this text being created?

2: Who is the Author?

- How do they position themselves as an expert worth listening to?

- What is their ethos?

- Do they have a reputation that gives them authority?

- What is their intention?

- What values or customs do they have?

3: Who is it Written For?

- Who is the intended audience?

- How is this appealing to this particular audience?

- Who are the possible secondary and tertiary audiences?

4: What is the Central Idea?

- Can you summarize the key point of this rhetoric?

- What arguments are used?

- How has it developed a line of reasoning?

5: How is it Structured?

- What structure is used?

- How is the content arranged within the structure?

6: What Form is Used?

- Does this follow a specific literary genre?

- What type of style and tone is used, and why is this?

- Does the form used complement the content?

- What effect could this form have on the audience?

7: Is the Rhetoric Effective?

- Does the content fulfil the author’s intentions?

- Does the message effectively fit the audience, location, and time period?

Once you’ve fully explored the text, you’ll have a better understanding of the impact it’s having on the audience and feel more confident about writing your essay outline.

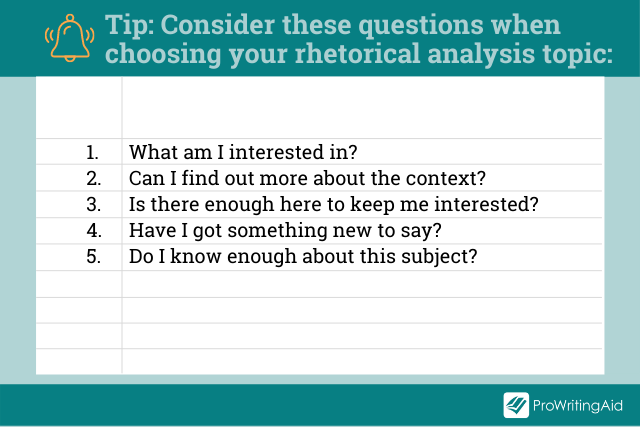

A great essay starts with an interesting topic. Choose carefully so you’re personally invested in the subject and familiar with it rather than just following trending topics. There are lots of great ideas on this blog post by My Perfect Words if you need some inspiration. Take some time to do background research to ensure your topic offers good analysis opportunities.

Remember to check the information given to you by your professor so you follow their preferred style guidelines. This outline example gives you a general idea of a format to follow, but there will likely be specific requests about layout and content in your course handbook. It’s always worth asking your institution if you’re unsure.

Make notes for each section of your essay before you write. This makes it easy for you to write a well-structured text that flows naturally to a conclusion. You will develop each note into a paragraph. Look at this example by College Essay for useful ideas about the structure.

1: Introduction

This is a short, informative section that shows you understand the purpose of the text. It tempts the reader to find out more by mentioning what will come in the main body of your essay.

- Name the author of the text and the title of their work followed by the date in parentheses

- Use a verb to describe what the author does, e.g. “implies,” “asserts,” or “claims”

- Briefly summarize the text in your own words

- Mention the persuasive techniques used by the rhetor and its effect

Create a thesis statement to come at the end of your introduction.

After your introduction, move on to your critical analysis. This is the principal part of your essay.

- Explain the methods used by the author to inform, entertain, and/or persuade the audience using Aristotle's rhetorical triangle

- Use quotations to prove the statements you make

- Explain why the writer used this approach and how successful it is

- Consider how it makes the audience feel and react

Make each strategy a new paragraph rather than cramming them together, and always use proper citations. Check back to your course handbook if you’re unsure which citation style is preferred.

3: Conclusion

Your conclusion should summarize the points you’ve made in the main body of your essay. While you will draw the points together, this is not the place to introduce new information you’ve not previously mentioned.

Use your last sentence to share a powerful concluding statement that talks about the impact the text has on the audience(s) and wider society. How have its strategies helped to shape history?

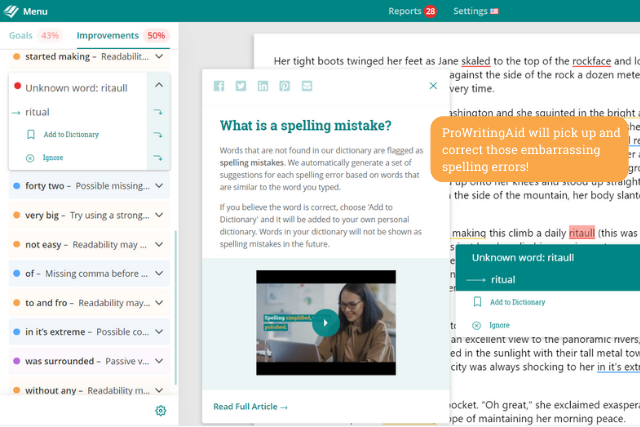

Before You Submit

Poor spelling and grammatical errors ruin a great essay. Use ProWritingAid to check through your finished essay before you submit. It will pick up all the minor errors you’ve missed and help you give your essay a final polish. Look at this useful ProWritingAid webinar for further ideas to help you significantly improve your essays. Sign up for a free trial today and start editing your essays!

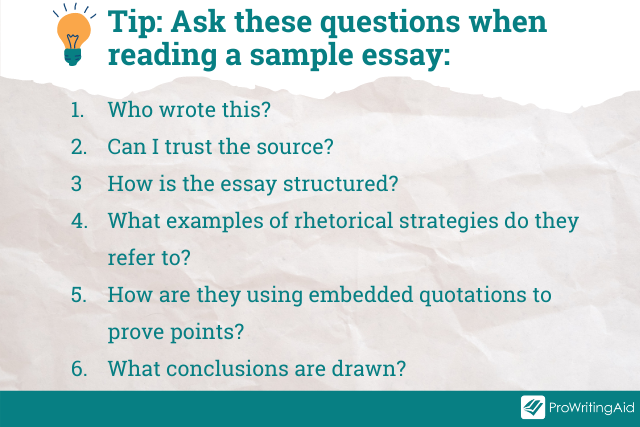

You’ll find countless examples of rhetorical analysis online, but they range widely in quality. Your institution may have example essays they can share with you to show you exactly what they’re looking for.

The following links should give you a good starting point if you’re looking for ideas:

Pearson Canada has a range of good examples. Look at how embedded quotations are used to prove the points being made. The end questions help you unpick how successful each essay is.

Excelsior College has an excellent sample essay complete with useful comments highlighting the techniques used.

Brighton Online has a selection of interesting essays to look at. In this specific example, consider how wider reading has deepened the exploration of the text.

Writing a rhetorical analysis essay can seem daunting, but spending significant time deeply analyzing the text before you write will make it far more achievable and result in a better-quality essay overall.

It can take some time to write a good essay. Aim to complete it well before the deadline so you don’t feel rushed. Use ProWritingAid’s comprehensive checks to find any errors and make changes to improve readability. Then you’ll be ready to submit your finished essay, knowing it’s as good as you can possibly make it.

Try ProWritingAid's Editor for Yourself

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Helly Douglas is a UK writer and teacher, specialising in education, children, and parenting. She loves making the complex seem simple through blogs, articles, and curriculum content. You can check out her work at hellydouglas.com or connect on Twitter @hellydouglas. When she’s not writing, you will find her in a classroom, being a mum or battling against the wilderness of her garden—the garden is winning!

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a rhetorical analysis

What is a rhetorical analysis?

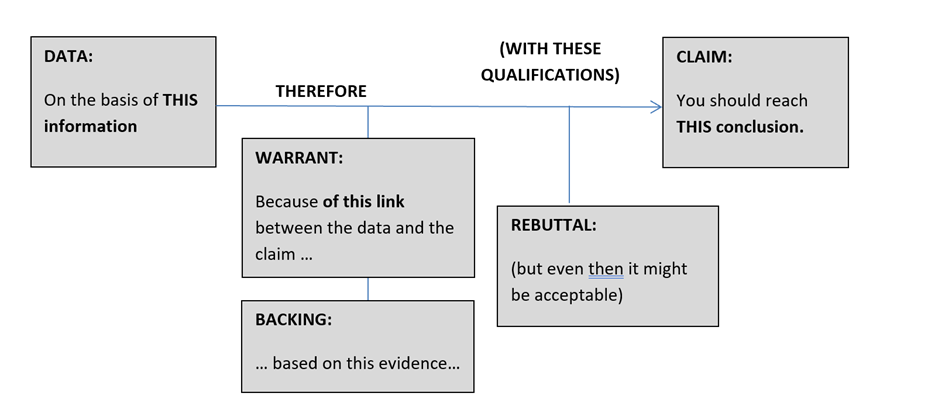

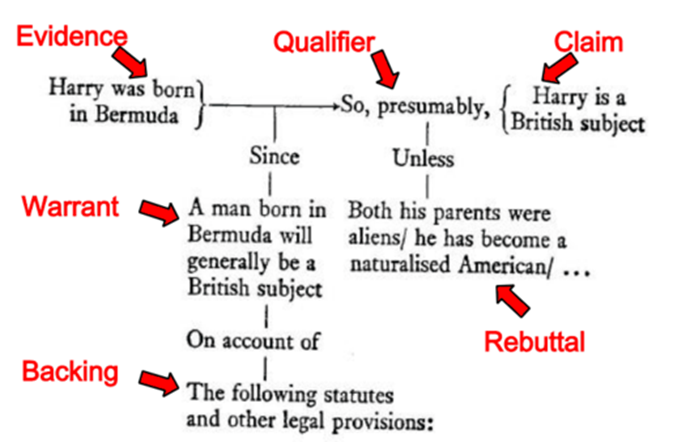

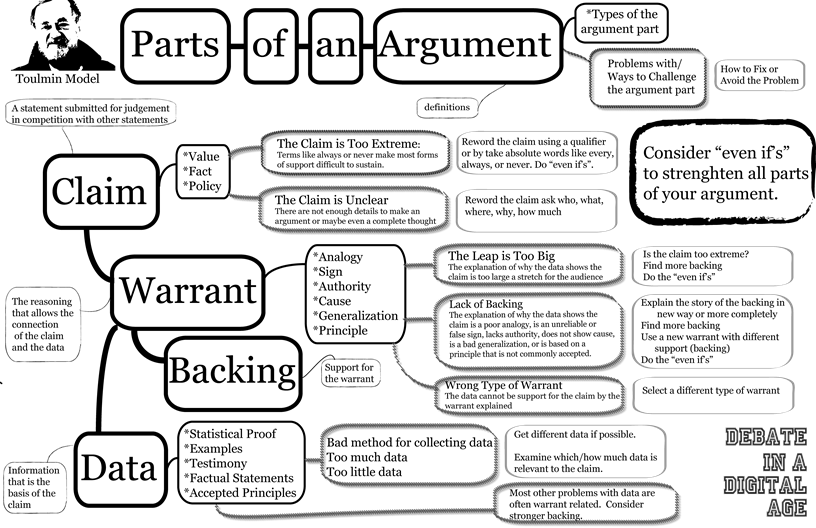

What are the key concepts of a rhetorical analysis, rhetorical situation, claims, supports, and warrants.

- Step 1: Plan and prepare

- Step 2: Write your introduction

- Step 3: Write the body

- Step 4: Write your conclusion

Frequently Asked Questions about rhetorical analysis

Related articles.

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion and aims to study writers’ or speakers' techniques to inform, persuade, or motivate their audience. Thus, a rhetorical analysis aims to explore the goals and motivations of an author, the techniques they’ve used to reach their audience, and how successful these techniques were.

This will generally involve analyzing a specific text and considering the following aspects to connect the rhetorical situation to the text:

- Does the author successfully support the thesis or claims made in the text? Here, you’ll analyze whether the author holds to their argument consistently throughout the text or whether they wander off-topic at some point.

- Does the author use evidence effectively considering the text’s intended audience? Here, you’ll consider the evidence used by the author to support their claims and whether the evidence resonates with the intended audience.

- What rhetorical strategies the author uses to achieve their goals. Here, you’ll consider the word choices by the author and whether these word choices align with their agenda for the text.

- The tone of the piece. Here, you’ll consider the tone used by the author in writing the piece by looking at specific words and aspects that set the tone.

- Whether the author is objective or trying to convince the audience of a particular viewpoint. When it comes to objectivity, you’ll consider whether the author is objective or holds a particular viewpoint they want to convince the audience of. If they are, you’ll also consider whether their persuasion interferes with how the text is read and understood.

- Does the author correctly identify the intended audience? It’s important to consider whether the author correctly writes the text for the intended audience and what assumptions the author makes about the audience.

- Does the text make sense? Here, you’ll consider whether the author effectively reasons, based on the evidence, to arrive at the text’s conclusion.

- Does the author try to appeal to the audience’s emotions? You’ll need to consider whether the author uses any words, ideas, or techniques to appeal to the audience’s emotions.

- Can the author be believed? Finally, you’ll consider whether the audience will accept the arguments and ideas of the author and why.

Summing up, unlike summaries that focus on what an author said, a rhetorical analysis focuses on how it’s said, and it doesn’t rely on an analysis of whether the author was right or wrong but rather how they made their case to arrive at their conclusions.

Although rhetorical analysis is most used by academics as part of scholarly work, it can be used to analyze any text including speeches, novels, television shows or films, advertisements, or cartoons.

Now that we’ve seen what rhetorical analysis is, let’s consider some of its key concepts .

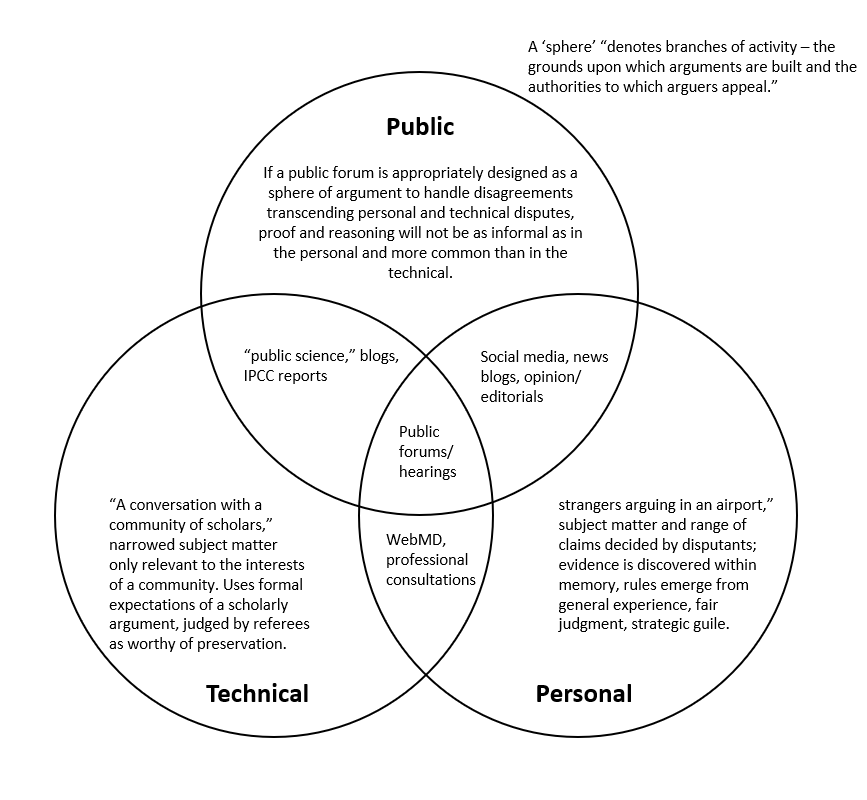

Any rhetorical analysis starts with the rhetorical situation which identifies the relationships between the different elements of the text. These elements include the audience, author or writer, the author’s purpose, the delivery method or medium, and the content:

- Audience: The audience is simply the readers of a specific piece of text or content or printed material. For speeches or other mediums like film and video, the audience would be the listeners or viewers. Depending on the specific piece of text or the author’s perception, the audience might be real, imagined, or invoked. With a real audience, the author writes to the people actually reading or listening to the content while, for an imaginary audience, the author writes to an audience they imagine would read the content. Similarly, for an invoked audience, the author writes explicitly to a specific audience.

- Author or writer: The author or writer, also commonly referred to as the rhetor in the context of rhetorical analysis, is the person or the group of persons who authored the text or content.

- The author’s purpose: The author’s purpose is the author’s reason for communicating to the audience. In other words, the author’s purpose encompasses what the author expects or intends to achieve with the text or content.

- Alphabetic text includes essays, editorials, articles, speeches, and other written pieces.

- Imaging includes website and magazine advertisements, TV commercials, and the like.

- Audio includes speeches, website advertisements, radio or tv commercials, or podcasts.

- Context: The context of the text or content considers the time, place, and circumstances surrounding the delivery of the text to its audience. With respect to context, it might often also be helpful to analyze the text in a different context to determine its impact on a different audience and in different circumstances.

An author will use claims, supports, and warrants to build the case around their argument, irrespective of whether the argument is logical and clearly defined or needs to be inferred by the audience:

- Claim: The claim is the main idea or opinion of an argument that the author must prove to the intended audience. In other words, the claim is the fact or facts the author wants to convince the audience of. Claims are usually explicitly stated but can, depending on the specific piece of content or text, be implied from the content. Although these claims could be anything and an argument may be based on a single or several claims, the key is that these claims should be debatable.

- Support: The supports are used by the author to back up the claims they make in their argument. These supports can include anything from fact-based, objective evidence to subjective emotional appeals and personal experiences used by the author to convince the audience of a specific claim. Either way, the stronger and more reliable the supports, the more likely the audience will be to accept the claim.

- Warrant: The warrants are the logic and assumptions that connect the supports to the claims. In other words, they’re the assumptions that make the initial claim possible. The warrant is often unstated, and the author assumes that the audience will be able to understand the connection between the claims and supports. In turn, this is based on the author’s assumption that they share a set of values and beliefs with the audience that will make them understand the connection mentioned above. Conversely, if the audience doesn’t share these beliefs and values with the author, the argument will not be that effective.

Appeals are used by authors to convince their audience and, as such, are an integral part of the rhetoric and are often referred to as the rhetorical triangle. As a result, an author may combine all three appeals to convince their audience:

- Ethos: Ethos represents the authority or credibility of the author. To be successful, the author needs to convince the audience of their authority or credibility through the language and delivery techniques they use. This will, for example, be the case where an author writing on a technical subject positions themselves as an expert or authority by referring to their qualifications or experience.

- Logos: Logos refers to the reasoned argument the author uses to persuade their audience. In other words, it refers to the reasons or evidence the author proffers in substantiation of their claims and can include facts, statistics, and other forms of evidence. For this reason, logos is also the dominant approach in academic writing where authors present and build up arguments using reasoning and evidence.

- Pathos: Through pathos, also referred to as the pathetic appeal, the author attempts to evoke the audience’s emotions through the use of, for instance, passionate language, vivid imagery, anger, sympathy, or any other emotional response.

To write a rhetorical analysis, you need to follow the steps below:

With a rhetorical analysis, you don’t choose concepts in advance and apply them to a specific text or piece of content. Rather, you’ll have to analyze the text to identify the separate components and plan and prepare your analysis accordingly.

Here, it might be helpful to use the SOAPSTone technique to identify the components of the work. SOAPSTone is a common acronym in analysis and represents the:

- Speaker . Here, you’ll identify the author or the narrator delivering the content to the audience.

- Occasion . With the occasion, you’ll identify when and where the story takes place and what the surrounding context is.

- Audience . Here, you’ll identify who the audience or intended audience is.

- Purpose . With the purpose, you’ll need to identify the reason behind the text or what the author wants to achieve with their writing.

- Subject . You’ll also need to identify the subject matter or topic of the text.

- Tone . The tone identifies the author’s feelings towards the subject matter or topic.

Apart from gathering the information and analyzing the components mentioned above, you’ll also need to examine the appeals the author uses in writing the text and attempting to persuade the audience of their argument. Moreover, you’ll need to identify elements like word choice, word order, repetition, analogies, and imagery the writer uses to get a reaction from the audience.

Once you’ve gathered the information and examined the appeals and strategies used by the author as mentioned above, you’ll need to answer some questions relating to the information you’ve collected from the text. The answers to these questions will help you determine the reasons for the choices the author made and how well these choices support the overall argument.

Here, some of the questions you’ll ask include:

- What was the author’s intention?

- Who was the intended audience?

- What is the author’s argument?

- What strategies does the author use to build their argument and why do they use those strategies?

- What appeals the author uses to convince and persuade the audience?

- What effect the text has on the audience?

Keep in mind that these are just some of the questions you’ll ask, and depending on the specific text, there might be others.

Once you’ve done your preparation, you can start writing the rhetorical analysis. It will start off with an introduction which is a clear and concise paragraph that shows you understand the purpose of the text and gives more information about the author and the relevance of the text.

The introduction also summarizes the text and the main ideas you’ll discuss in your analysis. Most importantly, however, is your thesis statement . This statement should be one sentence at the end of the introduction that summarizes your argument and tempts your audience to read on and find out more about it.

After your introduction, you can proceed with the body of your analysis. Here, you’ll write at least three paragraphs that explain the strategies and techniques used by the author to convince and persuade the audience, the reasons why the writer used this approach, and why it’s either successful or unsuccessful.

You can structure the body of your analysis in several ways. For example, you can deal with every strategy the author uses in a new paragraph, but you can also structure the body around the specific appeals the author used or chronologically.

No matter how you structure the body and your paragraphs, it’s important to remember that you support each one of your arguments with facts, data, examples, or quotes and that, at the end of every paragraph, you tie the topic back to your original thesis.

Finally, you’ll write the conclusion of your rhetorical analysis. Here, you’ll repeat your thesis statement and summarize the points you’ve made in the body of your analysis. Ultimately, the goal of the conclusion is to pull the points of your analysis together so you should be careful to not raise any new issues in your conclusion.

After you’ve finished your conclusion, you’ll end your analysis with a powerful concluding statement of why your argument matters and an invitation to conduct more research if needed.

A rhetorical analysis aims to explore the goals and motivations of an author, the techniques they’ve used to reach their audience, and how successful these techniques were. Although rhetorical analysis is most used by academics as part of scholarly work, it can be used to analyze any text including speeches, novels, television shows or films, advertisements, or cartoons.

The steps to write a rhetorical analysis include:

Your rhetorical analysis introduction is a clear and concise paragraph that shows you understand the purpose of the text and gives more information about the author and the relevance of the text. The introduction also summarizes the text and the main ideas you’ll discuss in your analysis.

Ethos represents the authority or credibility of the author. To be successful, the author needs to convince the audience of their authority or credibility through the language and delivery techniques they use. This will, for example, be the case where an author writing on a technical subject positions themselves as an expert or authority by referring to their qualifications or experience.

Appeals are used by authors to convince their audience and, as such, are an integral part of the rhetoric and are often referred to as the rhetorical triangle. The 3 types of appeals are ethos, logos, and pathos.

- Writing Center

- Current Students

- Online Only Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Parents & Family

- Alumni & Friends

- Community & Business

- Student Life

- Video Introduction

- Become a Writing Assistant

- All Writers

- Graduate Students

- ELL Students

- Campus and Community

- Testimonials

- Encouraging Writing Center Use

- Incentives and Requirements

- Open Educational Resources

- How We Help

- Get to Know Us

- Conversation Partners Program

- Workshop Series

- Professors Talk Writing

- Computer Lab

- Starting a Writing Center

- A Note to Instructors

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review

- Research Proposal

- Argument Essay

Rhetorical Analysis

Almost every text makes an argument. Rhetorical analysis is the process of evaluating elements of a text and determining how those elements impact the success or failure of that argument. Often rhetorical analyses address written arguments, but visual, oral, or other kinds of “texts” can also be analyzed.

Rhetorical Features—What to Analyze

Asking the right questions about how a text is constructed will help you determine the focus of your rhetorical analysis. A good rhetorical analysis does not try to address every element of a text; discuss just those aspects with the greatest [positive or negative] impact on the text’s effectiveness.

The Rhetorical Situation

Remember that no text exists in a vacuum. The rhetorical situation of a text refers to the context in which it is written and read, the audience to whom it is directed, and the purpose of the writer.

The Rhetorical Appeals

A writer makes many strategic decisions when attempting to persuade an audience. Considering the following rhetorical appeals will help you understand some of these strategies and their effect on an argument. Generally, writers should incorporate a variety of different rhetorical appeals rather than relying on only one kind.

Ethos (appeal to the writer’s credibility)

- What is the writer’s purpose (to argue, explain, teach, defend, call to action, etc.)?

- Do you trust the writer? Why?

- Is the writer an authority on the subject? What credentials does the writer have?

- Does the writer address other viewpoints?

- How does the writer’s word choice or tone affect how you view the writer?

Pathos (appeal to emotion or to an audience’s values or beliefs)

- Who is the target audience for the argument?

- How is the writer trying to make the audience feel (i.e., sad, happy, angry, guilty)?

- Is the writer making any assumptions about the background, knowledge, values, etc. of the audience?

Logos (appeal to logic)

- Is the writer’s evidence relevant to the purpose of the argument? Is the evidence current (if applicable)? Does the writer use a variety of sources to support the argument?

- What kind of evidence is used (i.e., expert testimony, statistics, proven facts)?

- Do the writer’s points build logically upon each other?

- Where in the text is the main argument stated? How does that placement affect the success of the argument?

- Does the writer’s thesis make that purpose clear?

Kairos (appeal to timeliness)

- When was the argument originally presented?

- Where was the argument originally presented?

- What circumstances may have motivated the argument?

- Does the particular time or situation in which this text is written make it more compelling or persuasive?

- What would an audience at this particular time understand about this argument?

Writing a Rhetorical Analysis Essay

No matter the kind of text you are analyzing, remember that the text’s subject matter is never the focus of a rhetorical analysis. The most common error writers make when writing rhetorical analyses is to address the topic or opinion expressed by an author instead of focusing on how that author constructs an argument.

You must read and study a text critically in order to distinguish its rhetorical elements and strategies from its content or message. By identifying and understanding how audiences are persuaded, you become more proficient at constructing your own arguments and in resisting faulty arguments made by others.

A thesis for a rhetorical analysis does not address the content of the writer’s argument. Instead, the thesis should be a statement about specific rhetorical strategies the writer uses and whether or not they make a convincing argument.

Incorrect: Smith’s editorial promotes the establishment of more green space in the Atlanta area through the planting of more trees along major roads.

This statement is summarizing the meaning and purpose of Smith’s writing rather than making an argument about how – and how effectively – Smith presents and defends his position.

Correct: Through the use of vivid description and testimony from affected citizens, Smith makes a powerful argument for establishing more green space in the Atlanta area.

Correct: Although Smith’s editorial includes vivid descriptions of the destruction of green space in the Atlanta area, his argument will not convince his readers because his claim is not backed up with factual evidence.

These statements are both focused on how Smith argues, and both make a claim about the effectiveness of his argument that can be defended throughout the paper with examples from Smith’s text.

Introduction

The introduction should name the author and the title of the work you are analyzing. Providing any relevant background information about the text and state your thesis (see above). Resist the urge to delve into the topic of the text and stay focused on the rhetorical strategies being used.

Summary of argument

Include a short summary of the argument you are analyzing so readers not familiar with the text can understand your claims and have context for the examples you provide.

The body of your essay discusses and evaluates the rhetorical strategies (elements of the rhetorical situation and rhetorical appeals – see above) that make the argument effective or not. Be certain to provide specific examples from the text for each strategy you discuss and focus on those strategies that are most important to the text you are analyzing. Your essay should follow a logical organization plan that your reader can easily follow.

Go beyond restating your thesis; comment on the effect or significance of the entire essay. Make a statement about how important rhetorical strategies are in determining the effectiveness of an argument or text.

Analyzing Visual Arguments

The same rhetorical elements and appeals used to analyze written texts also apply to visual arguments. Additionally, analyzing a visual text requires an understanding of how design elements work together to create certain persuasive effects (or not). Consider how elements such as image selection, color, use of space, graphics, layout, or typeface influence an audience’s reaction to the argument that the visual was designed to convey.

This material was developed by the KSU Writing Center and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License . All materials created by the KSU Writing Center are free to use and can be adopted, remixed, and shared at will as long as the materials are attributed. Please keep this information on materials you adapt or adopt for attribution purposes.

Contact Info

Kennesaw Campus 1000 Chastain Road Kennesaw, GA 30144

Marietta Campus 1100 South Marietta Pkwy Marietta, GA 30060

Campus Maps

Phone 470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

kennesaw.edu/info

Media Resources

Resources For

Related Links

- Financial Aid

- Degrees, Majors & Programs

- Job Opportunities

- Campus Security

- Global Education

- Sustainability

- Accessibility

470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

© 2024 Kennesaw State University. All Rights Reserved.

- Privacy Statement

- Accreditation

- Emergency Information

- Report a Concern

- Open Records

- Human Trafficking Notice

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

III. Rhetorical Situation

3.7 Rhetorical Modes of Writing

Kathryn Crowther; Lauren Curtright; Nancy Gilbert; Barbara Hall; Tracienne Ravita; Kirk Swenson; Ann Inoshita; Karyl Garland; Kate Sims; Jeanne K. Tsutsui Keuma; Tasha Williams; Susan Wood; and Terri Pantuso

Rhetorical modes simply mean the ways we can effectively communicate through language. Each day people interact with others to tell a story about a new pet, describe a transportation problem, explain a solution to a science experiment, evaluate the quality of an information source, persuade a customer that a brand is the best, or even reveal what has caused a particular medical issue. We speak in a manner that is purposeful to each situation, and writing is no different. While rhetorical modes can refer to both speaking and writing, in this section we discuss the ways in which we shape our writing according to our purpose or intent. Your purpose for writing determines the mode you choose.

Typically speaking, the four major categories of rhetorical modes are narration, description, exposition, and persuasion.

- The narrative essay tells a relevant story or relates an event.

- The descriptive essay uses vivid, sensory details to draw a picture in words.

- The writer’s purpose in expository writing is to explain or inform. Oftentimes, exposition is subdivided into other modes: classification, evaluation, process, definition, comparison/contrast, and cause/effect.

- In the persuasive essay, the writer’s purpose is to persuade or convince the reader by presenting one idea against another and clearly taking a stand on one side of the issue. We often use several of these modes in everyday and professional writing situations, so we will also consider special examples of these modes such as personal statements and other common academic writing assignments.

Whether you are asked to write a cause/effect essay in a history class, a comparison/contrast report in biology, or a narrative email recounting the events in a situation on the job, you will be equipped to express yourself precisely and communicate your message clearly. Learning these rhetorical modes will also help you to become a more effective writer.

Narration means the art of storytelling, and the purpose of narrative writing is to tell stories. Any time you tell a story to a friend or family member about an event or incident in your day, you engage in a form of narration. A narrative can be factual or fictional. A factual story is one that is based on, and tries to be faithful to, actual events as they unfolded in real life. A fictional story is a made-up, or imagined, story. When writing a fictional story, we can create characters and events to best fit our story.

The big distinction between factual and fictional narratives is determined by a writer’s purpose. The writers of factual stories try to recount events as they actually happened, but writers of fictional stories can depart from real people and events because their intentions are not to retell a real-life event. Biographies and memoirs are examples of factual stories, whereas novels and short stories are examples of fictional stories.

Because the line between fact and fiction can often blur, it is helpful to understand what your purpose is from the beginning. Is it important that you recount history, either your own or someone else’s? Or does your interest lie in reshaping the world in your own image—either how you would like to see it or how you imagine it could be? Your answers will go a long way in shaping the stories you tell.

Ultimately, whether the story is fact or fiction, narrative writing tries to relay a series of events in an emotionally engaging way. You want your audience to be moved by your story, which could mean through laughter, sympathy, fear, anger, and so on. The more clearly you tell your story, the more emotionally engaged your audience is likely to be.

The Structure of a Narrative Essay

Major narrative events are most often conveyed in chronological order, the order in which events unfold from first to last. Stories typically have a beginning, a middle, and an end, and these events are typically organized by time. However, sometimes it can be effective to begin with an exciting moment from the climax of the story (“flash-forward”) or a pivotal event from the past (“flash-back”) before returning to a chronological narration. Certain transitional words and phrases aid in keeping the reader oriented in the sequencing of a story.

The following are the other basic components of a narrative:

- Plot: The events as they unfold in sequence.

- Characters: The people who inhabit the story and move it forward. Typically, there are minor characters and main characters. The minor characters generally play supporting roles to the main character, or the protagonist.

- Conflict: The primary problem or obstacle that unfolds in the plot that the protagonist must solve or overcome by the end of the narrative. The way in which the protagonist resolves the conflict of the plot results in the theme of the narrative.

- Theme: The ultimate message the narrative is trying to express; it can be either explicit or implicit.

- Write the narrative of a typical Saturday in your life.

- Write a narrative of your favorite movie.

Description

Writers use description in writing to make sure that their audience is fully immersed in the words on the page. This requires a concerted effort by the writer to describe the world through the use of sensory details.

As mentioned earlier, sensory details are descriptions that appeal to our sense of sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch. The use of sensory details provides you the greatest possibility of relating to your audience and thus engaging them in your writing, making descriptive writing important not only during your education but also during everyday situations. To make your writing vivid and appealing, avoid empty descriptors if possible. Empty descriptors are adjectives that can mean different things to different people. Good, beautiful, terrific, and nice are examples. The use of such words in descriptions can lead to misreads and confusion. A good day, for instance, can mean far different things depending on one’s age, personality, or tastes.

The Structure of a Description Essay

Description essays typically describe a person, a place, or an object using sensory details. The structure of a descriptive essay is more flexible than in some of the other rhetorical modes. The introduction of a description essay should set up the tone and focus of the essay. The thesis should convey the writer’s overall impression of the person, place, or object described in the body paragraphs.

The organization of the essay may best follow spatial order, which means an arrangement of ideas according to physical characteristics or appearance. Depending on what the writer describes, the organization could move from top to bottom, left to right, near to far, warm to cold, frightening to inviting, and so on. For example, if the subject were a client’s kitchen in the midst of renovation, you might start at one side of the room and move slowly across to the other end, describing appliances, cabinetry, and so on. Or you might choose to start with older remnants of the kitchen and progress to the new installations. Or maybe start with the floor and move up toward the ceiling.

- Describe various objects found in your room.

- Describe an analog clock.

Classification

The purpose of classification is to break down broad subjects into smaller, more manageable, more specific parts. We classify things in our daily lives all the time, often without even thinking about it. For example, cars can be classified by type (convertible, sedan, station-wagon, or SUV) or by the fuel they use (diesel, petrol, electric, or hybrid). Smaller categories, and the way in which these categories are created, help us make sense of the world. Keep both of these elements in mind when writing a classification essay. It’s best to choose topics that you know well when writing classification essays. The more you know about a topic, the more you can break it into smaller, more interesting parts. Adding interest and insight will enhance your classification essays.

The Structure of a Classification Essay

The classification essay opens with a paragraph that introduces the broader topic. The thesis should then explain how that topic is divided into subgroups and why. Take the following introductory paragraph, for example:

When people think of New York, they often think of only New York City. But New York is actually a diverse state with a full range of activities to do, sights to see, and cultures to explore. In order to better understand the diversity of New York State, it is helpful to break it into these five separate regions: Long Island, New York City, Western New York, Central New York, and Northern New York.

The underlined thesis explains not only the category and subcategory, but also the rationale for breaking the topic into those categories. Through this classification essay, the writer hopes to show the readers a different way of considering the state of New York.

Each body paragraph of a classification essay is dedicated to fully illustrating each of the subcategories. In the previous example, then, each region of New York would have its own paragraph. To avoid settling for an overly simplistic classification, make sure you break down any given topic at least three different ways. This will help you think outside the box and perhaps even learn something entirely new about a subject.

The conclusion should bring all of the categories and subcategories back together again to show the reader the big picture. In the previous example, the conclusion might explain how the various sights and activities of each region of New York add to its diversity and complexity.

- Classify your college by majors (i.e. biology, chemistry, physics, etc.).

- Classify the variety of fast food places available to you by types of foods sold in each location.

Writers evaluate arguments in order to present an informed and well-reasoned judgment about a subject. While the evaluation will be based on their opinion, it should not seem opinionated. Instead, it should aim to be reasonable and unbiased. This is achieved through developing a solid judgment, selecting appropriate criteria to evaluate the subject, and providing clear evidence to support the criteria.

Evaluation is a type of writing that has many real-world applications. Anything can be evaluated. For example, evaluations of movies, restaurants, books, and technology ourselves are all real-world evaluations.

The Structure of an Evaluation Essay

Evaluation essays are typically structured as follows.

Subject : First, the essay will present the subject. What is being evaluated? Why? The essay begins with the writer giving any details needed about the subject.

Judgement : Next, the essay needs to provide a judgment about a subject. This is the thesis of the essay, and it states whether the subject is good or bad based on how it meets the stated criteria.

Criteria : The body of the essay will contain the criteria used to evaluate the subject. In an evaluation essay, the criteria must be appropriate for evaluating the subject under consideration. Appropriate criteria will help to keep the essay from seeming biased or unreasonable. If authors evaluated the quality of a movie based on the snacks sold at the snack bar, that would make them seem unreasonable, and their evaluation may be disregarded because of it.

Evidence : The evidence of an evaluation essay consists of the supporting details authors provide based on their judgment of the criteria. For example, if the subject of an evaluation is a restaurant, a judgment could be “Kay’s Bistro provides an unrivaled experience in fine dining.” Some authors evaluate fine dining restaurants by identifying appropriate criteria in order to rate the establishment’s food quality, service, and atmosphere. The examples are the evidence.

Another example of evaluation is literary analysis; judgments may be made about a character in the story based on the character’s actions, characteristics, and past history within the story. The scenes in the story are evidence for why readers have a certain opinion of the character.

Job applications and interviews are more examples of evaluations. Based on certain criteria, management and hiring committees determine which applicants will be considered for an interview and which applicant will be hired.

- Evaluate a restaurant. What do you expect in a good restaurant? What criteria determines whether a restaurant is good?

- List three criteria that you will use to evaluate a restaurant. Then dine there. Afterwards, explain whether or not the restaurant meets each criteria, and include evidence (qualities from the restaurant) that backs your evaluation.

- Give the restaurant a star rating. (5 Stars: Excellent, 4 Stars: Very Good, 3 Stars: Good, 2 Stars: Fair, 1 Star: Poor). Explain why the restaurant earned this star rating.

The purpose of a process essay is to explain how to do something (directional) or how something works (informative). In either case, the formula for a process essay remains the same. The process is articulated into clear, definitive steps.

Almost everything we do involves following a step-by-step process. From learning to ride a bike as a child to starting a new job as an adult, we initially needed instructions to effectively execute the task. Likewise, we have likely had to instruct others, so we know how important good directions are—and how frustrating it is when they are poorly put together.

The Structure of a Process Essay

The process essay opens with a discussion of the process and a thesis statement that states the goal of the process. The organization of a process essay typically follows chronological order. The steps of the process are conveyed in the order in which they usually occur, and so your body paragraphs will be constructed based on these steps. If a particular step is complicated and needs a lot of explaining, then it will likely take up a paragraph on its own. But if a series of simple steps is easy to understand, then the steps can be grouped into a single paragraph. Words such as first, second, third, next, and finally are cues to orient readers and organize the content of the essay.

Finally, it’s a good idea to always have someone else read your process analysis to make sure it makes sense. Once we get too close to a subject, it is difficult to determine how clearly an idea is coming across. Having a peer read over your analysis will serve as a good way to troubleshoot any confusing spots.

- Describe the process for applying to college.

- Describe the process of your favorite game (board, card, video, etc.).

The purpose of a definition essay may seem self-explanatory: to write an extended definition of a word or term. But defining terms in writing is often more complicated than just consulting a dictionary. In fact, the way we define terms can have far-reaching consequences for individuals as well as collective groups. Take, for example, a word like alcoholism. The way in which one defines alcoholism depends on its legal, moral, and medical contexts. Lawyers may define alcoholism in terms of its legality; parents may define alcoholism in terms of its morality; and doctors will define alcoholism in terms of symptoms and diagnostic criteria. Think also of terms that people tend to debate in our broader culture. How we define words, such as marriage and climate change, has an enormous impact on policy decisions and even on daily decisions. Debating the definition of a word or term might have an impact on your relationship or your job, or it might simply be a way to understand an unfamiliar phrase in popular culture or a technical term in a new profession.

Defining terms within a relationship, or any other context, can be difficult at first, but once a definition is established between two people or a group of people, it is easier to have productive dialogues. Definitions, then, establish the way in which people communicate ideas. They set parameters for a given discourse, which is why they are so important.

When writing definition essays, avoid terms that are too simple, that lack complexity. Think in terms of concepts, such as hero, immigration, or loyalty, rather than physical objects. Definitions of concepts, rather than objects, are often fluid and contentious, making for a more effective definition essay. For definition essays, try to think of concepts in which you have a personal stake. You are more likely to write a more engaging definition essay if you are writing about an idea that has value and importance to you.

The Structure of a Definition Essay

The definition essay opens with a general discussion of the term to be defined. You then state your definition of the term as your thesis. The rest of the essay should explain the rationale for your definition. Remember that a dictionary’s definition is limiting, so you should not rely strictly on the dictionary entry. Indeed, unless you are specifically addressing an element of the dictionary definition (perhaps to dispute or expand it), it is best to avoid quoting the dictionary in your paper. Instead, consider the context in which you are using the word. Context identifies the circumstances, conditions, or setting in which something exists or occurs. Often words take on different meanings depending on the context in which they are used. For example, the ideal leader in a battlefield setting could likely be very different from a leader in an elementary school setting. If a context is missing from the essay, the essay may be too short or the main points could be vague and confusing.

The remainder of the essay should explain different aspects of the term’s definition. For example, if you were defining a good leader in an elementary classroom setting, you might define such a leader according to personality traits: patience, consistency, and flexibility. Each attribute would be explained in its own paragraph. Be specific and detailed: flesh out each paragraph with examples and connections to the larger context.

- Define what is meant by the word local.

- Define what is meant by the word community.

Comparison and Contrast

Comparison in writing discusses elements that are similar, while contrast in writing discusses elements that are different. A compare-and-contrast essay, then, analyzes two subjects by examining them closely and comparing them, contrasting them, or both. The key to a good compare-and-contrast essay is to choose two or more subjects that connect in a meaningful way. The purpose of conducting the comparison or contrast is not to state the obvious but rather to illuminate subtle differences or unexpected similarities. For example, if you wanted to focus on contrasting two subjects you would not pick apples and oranges; rather, you might choose to compare and contrast two types of oranges or two types of apples to highlight subtle differences. For example, Red Delicious apples are sweet, while Granny Smiths are tart and acidic. Drawing distinctions between elements in a similar category will increase the audience’s understanding of that category, which is the purpose of the compare-and-contrast essay.