WRITER'S CATAPULT

Poetry as Parachute, Wand & Scalpel for the Savvy, Kick-Ass Communicator

ROUGH DRAFT RUBRIC & REVISION RECIPE

THE ROUGH DRAFT RUBRIC

1. Techniques (5 points) ___Specific details/furniture, use of at least one allusion 1 ___Image-sensory based, concrete not abstract, show don’t tell 1 ___Language: diction, dialogue, fluid, syntax, no chopped prose 1 ___Figurative Language: metaphor, symbol, personification, simile 1 ___Sound/music: anaphora, rhyme, alliteration, assonance, tone matches .5 ___Voice: author in control of subject and tone .5 ___TOTAL (5) 2. Mechanics: (2 points) Punctuation, sentence errors, spelling, line breaks, usage, tense or POV changes,

pronouns, agreement, usage, epigraphs punctuated, present tense active verbs! ___TOTAL (2) 3. Coherence: Clear focus, title, content & format reinforce one another ___TOTAL (1) 4. Style: Plain, sentence variety, parallel structure, concise, panache ___TOTAL (1) 5. Manuscript Style: No bold or centering, 12 pt. fonts, Times New Roman, spacing 1.5 poetry & 2 for prose, CAPS for titles, margins left, no auto caps ___TOTAL (1) ___Epigraphs: extra credit + 2 out of 100 ___GRAND TOTAL (10)

GRADE A, FIRST-CLASS, TOP-NOTCH, SURE-FIRE, REVISION RECIPE

___1. Check off or add an epigraph or weave quotation into the text.

___2. Use allusion: literary, artistic, historical or scientific references.

___3. Figurative language: add one more metaphor, personification or paradox.

___4. Upgrade vocabulary of three words. Use a thesaurus but don’t overdo!

Proofread to avoid verbs of being. (is & am) Use action verbs.

___5. Use two lists for music and momentum.

___6. Use an auditory image, add an additional image, one should not be visual.

___7. Read aloud. Listen for sound. Consider euphony, cacophony, refrains.

___8. Parallel structure: I came. I saw. I conquered . Or Of the people, by the….

___9. Conciseness: trim extra words. Avoid redundancy.

___10. Use sentence variety. Vary short sentences or frags. Then combine

to achieve more complex expressions.

Ask the “so what?” & “who cares?” questions.

Does your work startle our delight? If not try again.

Use synesthesia.

Proofread for unity, logic & coherence. Check facts. Research.

Volunteer to give & get help from a peer editor.

- ← THE SEVEN DEADLY SINS

- THE CREATIVE PROCESS →

- Units and Programs

Make a Gift

Rubrics & Checklists

Grading criteria can be very simple or complex. They can analyze discrete elements of performance or describe general traits that define papers in a given grade range. You can use them to set up a scoring sheet for grading final drafts, and to create revision-oriented checklists to speed up commenting on early drafts of projects. By far the best way to clarify grading criteria is to look at one or more sample pieces of writing, asking students to apply the criteria, and discussing their judgments as a class.

Analytical approaches to grading

Analytical rubrics assign a specific point value to each attribute of a project (for example: thesis, evidence, logic, discussion, development, grammar, spelling, and formatting). They may be arranged graphically as grids, sliding scales, or checklists. You can weight categories to reflect issues of more or less concern, such as stressing the quality of a student’s thesis more than spelling skills. Analytical grade scales allow very detailed assessment of multi-faceted projects, but the more detailed they are, the longer they take to develop, fine-tune, and use. They also are more likely to elicit “bean-counting” responses from students, who want to know why they “lost” five points for comma splices when a fellow student was only penalized three points for spelling errors. Some instructors and students dislike what can feel like a lack of flexibility in analytical assessment.

Holistic approaches to grading

Holistic grading rubrics typically focus on larger skill sets demonstrated in the writing. They can be as detailed or as general as you like. Ideally, the descriptions will use specific language, but not overload students with information. Assigning holistic grades often speeds up the grading process, and many instructors feel holistic grades best reflect the inseparability of mechanics and ideas. But without good performance level descriptions, holistic grades can frustrate students, because they don’t convey a lot of information.

Creating your own criteria

Analytical and holistic elements can be combined in a single set of grading criteria. Use the arrangement that best fits the way you think as you are grading, and makes the most sense in terms of the particular assignment you are creating.

Also, when writing the criteria, use language that reflects your strengths and the way you grade. If you don’t have an encyclopedic knowledge of grammar errors, judge a paper’s “coherence and readability” rather than “number of sentence boundary errors.”

Here we have collected samples of grading criteria, checklists, and rubrics developed by writing instructors in different fields. We will be adding to this list fairly regularly, but of there is a specific type of rubric you would like to see that we have not yet added, please contact our office.

Rough Draft Revision Checklist This checklist for providing comments on students’ early drafts of writing projects was designed for a causal analysis paper in a freshman-level composition course. It analyzes the draft across four performance areas: Claim or thesis, logic and reasoning, support and development, and organization and mechanics. The weaknesses most commonly seen in causal draft papers are described, with additional space left for comments in each section (the additional spaces are ideal for noting a draft’s strengths).

Holistic Grading Criteria These criteria were developed by Dr. David Barndollar for a sophomore-level English course. Here, the descriptions are grouped by grade performance level (A, B, C, D, and F) with the same five concerns addressed at each level: quality of ideas, development and organization, language and word choice, mechanics, and style.

Analytical Grading Outline This grade sheet is adapted from one devised by Dr. Ruth Franks for a long research paper in her Biology 325L class. This highly-detailed rubric apportions 300 points for various performance categories. Dr. Franks was the winner of the 2003-3004 SWC Award for Writing Instruction.

Scaled Analytical Rubric This very simple grade sheet was used by Dr. Susan Schorn for giving final grades on short papers in a rhetoric class. General performance descriptors are scaled to the point range for each criterion. The criteria on this grade sheet are not described here, but they map to more extensive criteria students received in the course syllabus and paper assignment. Note that space is left under each criterion for instructor comments.

Grading Grid Dr. Joanna Migrock devised a criteria grid or table for assessing all assignments in a first-year composition class. Five performance areas are delineated: Purpose, Content, Audience, Organization, and Mechanics. Four performance levels are then described for each area. This grid could be used as is to give revision-oriented feedback on drafts; with the addition of grade weightings at each performance level, it could also be used to grade final drafts.

- Forgot your Password?

First, please create an account

Making the grade: create your own writing rubric, acknowledgements:.

A required course in the University's general education program, UK Core , C&C I students are expected to demonstrate competent written, oral, and visual communication skills both as producers and consumers of information. Emphasizing critical inquiry and research, C&C instructors at UK encourage students to explore their place in the broader community and take a stance on issues of public concern—that is, to view themselves as engaged citizens. Students work independently, with a partner, or with a small group of classmates to investigate, share findings, and compose presentations through appropriate media, as well as to practice and evaluate interpersonal and team dynamics in action. Download the area description that provides more information about the goals and purposes of the UK’s C&C courses at the UK Core website .

Step 1: Introduction to Rubrics

A rubric is a way to communicate the way a piece of writing or digital media should look like in its final form, and then evaluate the resulting work. It is basically a description of the task that is laid out on a grid. A good rubric divides up a writing assignment into its different components and gives a detailed description of what are acceptable (or unacceptable) levels of performance for each.

If you agree with at least one of the following statements, you need to start using rubrics for your writing assignments:

- I often don’t understand why I get the grades I do on my papers in school.

- Many times, people who read my papers or watch my videos don’t get what I was trying to say.

- When I submit a draft of my research paper, the teacher gives me comments that have nothing to do with the problems I think I’m having with the assignment.

A rubric has four basic parts:

- A description of the task based on major categories important to the kind of writing to be done

- Dimensions of the task laid out in each category

- Descriptions of each of those dimensions

- Descriptions of the levels of performance by a scale

There are rubrics that work well in all different kinds of disciplines. Check out the rubrics showcased by the different subjects at Rubistar , an online rubric maker. Creating your own rubric based on categories you see in a writing assignment (including assignments resulting in digital media), will help you at both the rough draft and final draft stages.

A Good Rubric Looks Like This One

This rubric is used for assessing the UK Core Program required area in Composition and Communications - faculty are given anonymous versions of randomly selected submissions from students from the UK's Composition & Communication courses.

Source: UK Core Program Assessment, Evaluation Rubrics: http://www.uky.edu/ukcore/Evaluation_Rubrics

Step 2: Practice Using a Rubric

A good way to understand how a rubric works is to try it out yourself on a sample student essay. Practice on a sample of a draft of a college student’s response to an assignment to write a 500 word narrative essay. The assignment included these directions:

The essay will show one aspect of your ethics or belief system. The essay should include:

- An interesting introduction with a definition of a moral concept and a thesis statement

- A discussion of who (or what) influenced your personal development in that particular belief system with some concrete details appropriate to the readers of your paper

- A coherent narrative describing an experience highlighting a turning point in your life related to that moral concept

- Explain how the moral decision you faced affected you thereafter

- Restate the important points in the narrative and provide a conclusion

Now read the Student Essay, “Empathy, by Julie Smith” at http://web.gccaz.edu/~mdinchak/101online_new/ethics_example_essay1.htm

Use this rubric to assess the writing and determine how many points you would give it: http://web.gccaz.edu/~mdinchak/101online_new/rubric_narrativeessay.htm

Concentrate on the most important ways the draft could be improved – be sure and keep to the rubric. Now start writing up your own comments about the student’s draft essay with some productive comments. Write down more than what’s on the rubric to include your own ideas about how the sample essay matches a particular dimension of a category (or not). Develop a paragraph of constructive comments you would want to share with that fellow student. First of all, explain what rubric categories the essay satisfies and then, secondly, the categories that don’t seem to be addressed. It helps you be more clear in your own thinking to write with specifics about what you don't understand in the essay or what you suggest for revision -- what is the main point, what's missing, what needs more, what can be cut -- and why.

Step 3: Creating Your Own Rubric

Creating your own rubric is connected to learning how to analyze, interpret and evaluate messages that are conveyed in a variety of communication contexts: written, oral and visual. Give it a try. Create a rubric that works well for this assignment on writing a whitepaper - download the Word doc for the assignment available on the University of Kentucky's WRD website: https://wrd.as.uky.edu/writing-whitepaper.

Here are the categories that you should use for your rubric: thesis , content , organization , mechanics and diction , documentation and sources . What are the characteristics for each of the dimensions associated with those categories? For example if you had only 3 dimensions, how would you describe an “excellent” thesis – as opposed to an “average” one or a “poor” one?

Below you will find a partially completed rubric using the above categories required for you to write the assigned whitepaper. You will need to write on the rubric the following:

- Along the left-hand column, add in your own words the descriptions for each of the categories that best matches the directions for the assignment.

- Along the top row, fill out the percentages for each of the levels of achievement.

- Now explain in each cell what’s the most important part of each category to match the particular dimension or level of achievement. Some of the cells have been filled out for you already. These are suggestions only though they are derived from an actual rubric used to assess the above assignment used in a University of Kentucky Composition and Communication I class.

A Rubric Of Your Own

This partial rubric matches well with the WRD 110 whitepaper assignment.

Source: Abridged from the rubric developed by Jessica Holland, "All Purpose Grading Rubric," Writing, Rhetoric & Digital Media, College of Arts & Sciences, University of Kentucky ( https://wrd.as.uky.edu/all-purpose-grading-rubric )

Some Concluding Thoughts:

The purpose of this exercise is to consider ways to improve future projects in writing and creating digital media projects. Take a few minutes to reflect on the rubric you created:

- What would you say were your rubric’s real strengths? Are there any categories you would work on more if you had time?

- What would you do differently with your rubric if you could? What might you do differently in the future?

- Based on your research so far, what would you like to learn more about?

By completing this exercise, you have discovered that writing can be assessed fairly and that you can contribute to conversations that constructively resolve differing viewpoints. Ultimately, you should be able to produce better writing.

Additional Resources:

Elbow, Peter. "Ranking, evaluating, and liking: Sorting out three forms of judgment." College English (February 1993) 55, no. 2: 187-207.

Liu, Jianguo, D.T. Pysarchik, and W.W. Taylor. 2002. "Peer Review in the Classroom." Bioscience 52(9): 824-829.

Pearlman, Steven J. Reconciling Writing Assessment: Why Students Should Grade Students . Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2010.

RubiStar. ALTEC at University of Kansas. http://rubistar.4teachers.org/ .

“Rubric Examples.” California State University Bakersfield. http://www.csub.edu/TLC/options/resources/handouts/Rubric_Packet_Jan06.pdf

“Sample Writing Rubrics.” Farnham Writers’ Center Online. Colby College. http://web.colby.edu/farnham-writerscenter/sample-writing/

Topping, Keith. "Peer assessment between students in colleges and universities." Review of Educational Research (Fall 1998) 68, no. 3: 249-276.

VanDeWeghe, Rick. "'Awesome, Dude! responding helpfully to peer writing." Research Matters. English Journal (September 2004) 94, no. 1: 95-99.

Wilson, Maja. "The view from somewhere." Educational Leadership: Informative Assessment (December 2007/January 2008) 65, no. 4: 76-80. http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/dec07/vol65/num04/The-View-from-Somewhere.aspx

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

© 2024 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC.

The Research Paper: A Manual for Monty Tech: Rough Draft and Revision

- Topic Selection

- Research Question & Background Information

- Scholarly vs. Background

- Website Evaluation

- Research Databases Website

- Which Database Do I Use?

- Notes Sheet

- MLA Style Works Cited

- APA References Page

- Rough Draft and Revision

- Parenthetical Citations

- Sample MLA 8 Paper

- Sample APA Paper

Rough Draft Checklist

My Introduction has:

__ an attention grabber. __ an overview of my topic. __ my thesis statement at the end.

My Body paragraphs:

__ begin with a topic sentence that presents the subtopic. __ give strong evidence to support the subtopic. __ have a sentence which transitions to the next paragraph.

My Conclusion:

__ restates my thesis in different words or a different way. __ Briefly summarizes each subtopic. __ Ends with a strong clincher: a meaningful final sentence that usually refers back to the attention grabber.

Sample Papers

Sample MLA style paper

Sample APA style paper

Rough Draft

There are many manuals available in print and online on how to write. This isn’t one of them! However, there are some guidelines that you can follow that will make your writing better and the rough draft less painful.

· Read the assignment again if necessary. · This is your last chance to get more information, but don’t go overboard. You don’t have time to redo your research. There’s always one more stat, one more quote… · Read over your outline and check your introductory paragraph. Make sure that they match! · Have your notes sorted and visible. · Use your outline. · Make sure that your quotations are worth using. They must use language that is either difficult to paraphrase, or is so well-written that nothing you write could possibly do it justice. Sometimes quotes are exactly what you need to prove your argument. Direct quotes from important people in your subject area can also be beneficial. · Refer often to your rubric. This is how you will be graded! If you find that you will be marked down drastically for spelling and grammatical errors, pay special attention to these details.

When crafting body paragraphs, follow this structure: Begin with a topic sentence that presents a subtopic. Then give strong evidence in as many paragraphs as necessary to support this subtopic. Then have a sentence which transitions to your next paragraph. At times, this sentence can be a challenge to write. If you can’t think of a clever way to segue one paragraph to another, leave it alone and revisit the paragraph later.

Give yourself a break! Take several short breaks while writing. If this means stepping away from your desk and skipping around your house, do it. Talk to your parent. Pet your dog. Put away your laundry. Do not, however, go to Facebook or other time-eaters on the Internet. Do not text a friend or watch a movie. You need a break from technology of all kinds. Don’t do something that you know will turn into a long time commitment. Get a little bit of exercise, even if it means a couple sets of jumping jacks. Leave for some fresh air and then read what you have written down. You may be surprised at how good (or bad) it really is. The break will also give your brain time to digest some ideas. You may even have a “eureka” moment and discover a good sentence for your introduction or conclusion.

The conclusion should be written at the end. It should restate your thesis in different words or in a different way. You should briefly summarize each subtopic. End it with a strong clincher for a meaningful final sentence. This can be the hardest sentence to write, especially if you are in a rush. If, during your writing, you think of a clincher, write it down somewhere immediately!

Final Draft

Take some time to reflect on your rough draft. Put it away for a day or so and then reread it and make corrections. This is also the time to, once again, read the assignment sheet and rubric to make sure that you will maximize your chances of a better grade. Correct any grammatical and spelling errors. Double-check your Works Cited or References page and your parenthetical citations.

Examine the flow of your writing. Read it out loud. Does it sound good? Do the sentences transition easily from one to the next? If you wrote this paper all by yourself, you will have a certain style or “voice” to your writing that can be identified by your teacher. Is this voice consistent? Or do you sound alternately like a college professor? Be yourself. No one wants to read something that sounds like a piece of legal writing or literary criticism from the 18 th century.

On that note, remember that your teacher may have 30 of these to read. Make your writing interesting. If it reads like a bore in an attempt to sound professorial, it’s not going to help you.

If possible, present your rough draft to your teacher a week before the due date. If your teacher allows or requires a rough draft, they will make corrections on it. Make sure you follow these suggestions.

Subject Guide

- << Previous: Outline

- Next: Parenthetical Citations >>

- Last Updated: Mar 10, 2024 12:19 PM

- URL: https://montytech.libguides.com/researchprocess

ESL004: Advanced English as a Second Language

Synthesis essay example and rubric.

In the next section, you will write a synthesis essay in which you will include your ideas on a topic. Here, you will find a sample synthesis essay that will guide you and the rubric that will point out the elements considered in assessing your essay. Carefully examine the information on this page prior to writing your essay.

This essay example discusses the topic: "Is The Future Paperless?". It synthesizes a variety of viewpoints into a coherent, well-written essay. Notice how the author includes his/her own point of view in paragraph 2? Use this example as a guide to writing a good synthesis essay of your own. Remind yourself that a synthesis is NOT a summary.

Is going paperless the future? For schools, the answer is likely no, or not for some time. Paper documentation is still critical in the school environment, especially in administration. Student records contain sensitive information, and if online, in a paperless system, these records can be vulnerable to hacking. And while the idea of a school's records being hacked might seem alarmist, recall the recent hack of the United States Office of Personnel Management's hack. Schools might contain similar identifying information and might therefore be tempting to hackers.

Besides hacking, paper documents continue to have an advantage in established workplaces like schools. There, workflows already incorporate paper documents, and online systems operate only with significant investment in retraining. Students, too, rely on paper. For me, it is easier to get the full picture of an assignment from reading text written on a piece of paper rather than looking at a screen. True that some schools have initiatives in getting iPads and laptops for their students, but these expensive technologies are not as customizable by teachers as paper handouts, so their use is limited. Also, most people would like to have a paper backup in case something happens to their digital device. Paper and document technology are crucial to the current school environment, both in administration and students' own lives. As a company, H.G. Bissinger Office Technology is especially attuned to the significance of paper for education. They recently promoted one of their customer service managers to a new task force on meeting the document technology needs for education. That manager, Lyla Garrity, had created a uniquely strong collaborative relationship with Permian College. Through their work together, she realized that educational document services are an area that specialists could greatly improve, compared to unspecialized, general service that most schools suffer through. H.G. Bissinger Office Technology leases 10 copiers to the Northwest Local School District, along with technical support and copier supplies, excluding paper. For a school, the large investment in a machine is shadowed by the uncertainty of how far from obsolescence a machine might be. Also, purchasing a copier outright will leave the school or business to handle service on its own. Additionally, in these financially limited times, the initial investment of a large sum can be difficult to justify or approve. For schools, uncertainty over future budgets often makes a lease a more flexible option. Most copier leases deal with equipment costs by including provisions in which the client must purchase the machine at the end of the lease. More recently, lease companies like H.G. Bissinger Office Technology are offering leases that are more like rentals. After the monthly fee is paid, the company will take the machine back.

Each of the five items below is worth from 2 to 8 points. To calculate your composite score for your rough draft, add together your scores for all five rubric items below. The maximum score for your final draft is 40 points.

1. Evidential Support

- Excellent (8 points): I have clearly synthesized the content from the article, paraphrasing the ideas and connecting them to opinions to demonstrate comprehension. All of the main claims in my essay are supported by reasons based on accurate factual evidence derived from the article or a properly-formatted quotation, paraphrase, and/or summary of the assigned text.

- Proficient (6 points): I have clearly synthesized the content from the article, paraphrasing the ideas and related topics to demonstrate comprehension; however, my essay does not clearly reflect my opinion on the topic. The majority of the main claims in my essay are backed up by specific factual evidence, although a small number of my claims may be unsubstantiated statements or broad generalizations. When quoting or paraphrasing the assigned reading, I may occasionally misrepresent it or take it out of context.

- Adequate (4 points): I have synthesized the content from the article, paraphrasing the ideas and related topics to demonstrate comprehension, but my essay does not mention my point of view on the topic. At least half of the main claims in my essay are based on factual evidence or properly cited passages from the assigned reading. The other half of my claims may be unreasonable, lack quoted or factual support, may be based on misinformation or misreading, may consist of broad generalizations, or may distort and incorrectly format the assigned text.

- Not Yet Adequate (2 points): I have synthesized some of the content from the article, but my paraphrasing demonstrates limited comprehension of the topic, and my opinion on the topic is not addressed. On balance, most of the claims in my essay are unsubstantiated or based on distortions (or misreadings) of the assigned text.

- No Points Awarded (0 points): I have demonstrated minimal synthesis of the topic. My essay does not support its claims with evidence of any kind; my essay does not make claims in response to the prompt.

2. Persuasive Appeals

- Excellent (8 points): My essay uses a variety of persuasive appeals (emotion, logic, and credibility) to support its claims.

- Proficient (6 points): My essay uses some of the strategies effectively (as above) some of the time.

- Adequate (4 points): My essay uses at least one persuasive appeal correctly, but may sometimes use them unfairly or unconvincingly.

- Not Yet Adequate (2 points): If my essay uses persuasive appeals at all, it does so unfairly or unconvincingly.

- No Points Awarded (0 points): My essay uses none of the standard persuasive appeals discussed in this course.

3. Rhetorical Strategies

- Comparison and Contrast

- Definition of Terms

- Cause and Effect Analysis

- Proficient (6 points): My essay uses some of the rhetorical strategies employed by an excellent essay (above); my essay usually uses these strategies with a clear purpose, but may sometimes (for example) define a term without putting it to use, or draw a contrast without showing what it signifies.

- Adequate (4 points): My essay makes little use of the rhetorical strategies employed by an excellent essay, and may often do so without clear purpose and without using these techniques to persuade my reader; my essay may sometimes use these techniques incorrectly (for example, by providing inaccurate definitions of terms, or by confusing cause and effect).

- Not Yet Adequate (2 points): My essay incorporates few or no rhetorical appeals, and when it does, it does not use them correctly or persuasively.

- No Score Awarded (0 points): My essay does not use any of the rhetorical appeals used by an excellent essay (listed above).

- Excellent (8 points): The grammar errors on the list below, singly or in combination, occur no more than once per 250 words; no persistent patterns of grammar errors are present in the paper; errors do not distract the reader.

- Proficient (6 points): The errors on the list below, singly or in combination, occur no more than two times per 250 words; single errors from the list below may begin to recur and form a pattern of error; grammar errors are occasionally distracting to the reader.

- Close to Proficient (4 points): The errors on the list below, singly or in combination, occur on average three times per 250 words; single errors from the list below may recur and form a distinct pattern of error; errors of haste or lack of proofreading are present; grammar errors are persistently distracting to the reader.

- Not Yet Adequate (2 points): Grammar errors are numerous and impede the reader's comprehension of my essay; my essay reflects a lack of proofreading.

Common Grammatical Errors:

Each error type you have studied is shown next to an example of the error.

- Inappropriate Punctuation

- Faulty Parallel Structure

- Excessive or Inappropriate Use of the Passive Voice

- Use of weak "to be" verbs rather than strong, active verbs

- Failure to maintain a formal, rational, objective, unbiased, and academic tone that is directed at an educated audience

- Proficient (6 points): My essay reads clearly, but may occasionally exhibit one or two of the stylistic errors avoided by an excellent essay (above).

- Adequate (4 points): Not always, but distractingly often, my essay does not read smoothly because it repeats singly or in combination with the stylistic errors listed above.

- Not Yet Adequate (2 points): My essay exhibits the stylistic errors above so frequently that it is very difficult to read.

Use this checklist to review each of your sentences for errors:

- Read each sentence out loud. Do they sound correct? Is anything missing? You can add to your sentences if you want to explain more about your topic.

- Spelling – Is every word spelled correctly?

- Correct words – Did you use the right word? Many words in English look similar but have different meanings (for example, like and lick). Check each word to make sure it's the right one.

- Timeline order – Are your events in the correct order? Make sure your sentences don't jump around.

- Past tense – Are the verbs in each sentence conjugated in past tense? Go back and review verb endings if you're not sure.

- Describing words – Do each of your sentences include at least one adjective or one adverb?

- Capitalization – The first word in every sentence should be capitalized. After the first word, only proper nouns (like people's names) should be capitalized. Everything else should be lower case.

- Punctuation – Does each sentence end with a period? Questions may end with a question mark (?), and exclamations may end with an exclamation mark (!), but most of your sentences should end with a period (.).

Rough Drafts

In this section of the Excelsior OWL, you have been learning about traditional structures for expository essays (essays that are thesis-based and offer a point-by-point body), but no matter what type of essay you’re writing, the rough draft is going to be an important part of your writing process. It’s important to remember that your rough draft is a long way from your final draft, and you will engage in revision and editing before you have a draft that is ready to submit.

Sometimes, keeping this in mind can help you as you draft. When you draft, you don’t want to feel like “this has to be perfect.” If you put that much pressure on yourself, it can be really difficult to get your ideas down.

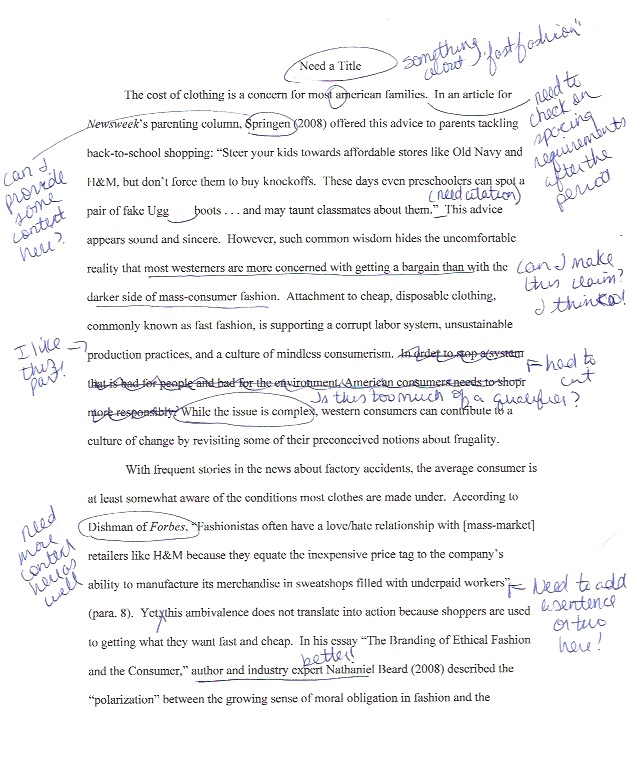

The sample rough draft below shows you an example of just how much more work a rough draft can need, even a really solid first draft. Take a look at this example with notes a student wrote on her rough draft. Once you complete your own rough draft, you will want to engage in a revision and editing process that involves feedback, time, and diligence on your part. The steps that follow in this section of the Excelsior OWL will help!

Rough Draft Example

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

Excelsior Online Writing Lab (OWL). Located at: https://owl.excelsior.edu/ . This site is licensed under a https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

ENG102 Contextualized for Health Sciences - OpenSkill Fellowship Copyright © 2022 by Compiled by Lori Walk. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Fiction Writing

- Writing Novels

How to Write a Rough Draft

Last Updated: February 6, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Michelle Golden, PhD . Michelle Golden is an English teacher in Athens, Georgia. She received her MA in Language Arts Teacher Education in 2008 and received her PhD in English from Georgia State University in 2015. There are 10 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 294,539 times.

Writing a rough draft is an essential part of the writing process, an opportunity to get your initial ideas and thoughts down on paper. It might be difficult to dive right into a rough draft of an essay or a creative piece, such as a novel or a short story. You should start by brainstorming ideas for the draft to get your creative juices flowing and take the time to outline your draft. You will then be better prepared to sit down and write your rough draft.

Brainstorming Ideas for the Draft

- Freewrites often work best if you give yourself a time limit, such as five minutes or ten minutes. You should then try to not take your pen off the page as you write so you are forced to keep writing about the subject or topic for the set period of time.

- For example, if you were writing an essay about the death penalty, you may use the prompt: “What are the possible issues or problems with the death penalty?” and write about it freely for ten minutes.

- Often, freewrites are also a good way to generate content that you can use later in your rough draft. You may surprised at what you realize as you write freely about the topic.

- To use the clustering method, you will place a word that describes your topic or subject in the center of your paper. You will then write keywords and thoughts around the center word. Circle the center word and draw lines away from the center to other keywords and ideas. Then, circle each word as you group them around the central word.

- For example, if you were trying to write a short story around a theme like “anger”, you will write “anger” in the middle of the page. You may then write keywords around “anger”, like “volcano”, “heat”, “my mother”, and “rage”.

- If you are writing a creative piece, you may look for texts written about a certain idea or theme that you want to explore in your own writing. You could look up texts by subject matter and read through several texts to get ideas for your story.

- You might have favorite writers that you return to often for inspiration or search for new writers who are doing interesting things with the topic. You could then borrow elements of the writer’s approach and use it in your own rough draft.

- You can find additional resources and texts online and at your local library. Speak to the reference librarian at your local library for more information on resources and texts.

Outlining Your Draft

- You may use the snowflake method to create the plot outline. In this method, you will write a one line summary of your story, followed by a one paragraph summary, and then character synopses. You will also create a spreadsheet of scenes.

- Alternatively, you can use a plot diagram. In this method, you will have six sections: the set up, the inciting incident, the rising action, the climax, the falling action, and the resolution.

- No matter which option you chose, you should make sure your outline contains at least the inciting incident, the climax, and the resolution. Having these three elements set in your mind will make writing your rough draft much easier.

- Act 1: In Act 1, your protagonist meets the other characters in the story. The central conflict of the story is also revealed. Your protagonist should also have a specific goal that will cause them to make a decision. For example, in Act 1, you may have your main character get bitten by a vampire after a one night stand. She may then go into hiding once she discovers she has become a vampire.

- Act 2: In Act 2, you introduce a complication that makes the central conflict even more of an issue. The complication can also make it more difficult for your protagonist to achieve their goal. For example, in Act 2, you may have your main character realize she has a wedding to go to next week for her best friend, despite the fact she has now become a vampire. The best friend may also call to confirm she is coming, making it more difficult for your protagonist to stay in hiding.

- Act 3: In Act 3, you present a resolution to the central conflict of the story. The resolution may have your protagonist achieve their goal or fail to achieve their goal. For example, in Act 3, you may have your protagonist show up to the wedding and try to pretend to not be a vampire. The best friend may then find out and accept your protagonist anyway. You may end your story by having your protagonist bite the groom, turning him into her vampire lover.

- Section 1: Introduction, including a hook opening line, a thesis statement , and three main discussion points. Most academic essays contain at least three key discussion points.

- Section 2: Body paragraphs, including a discussion of your three main points. You should also have supporting evidence for each main point, from outside sources and your own perspective.

- Section 3: Conclusion, including a summary of your three main points, a restatement of your thesis, and concluding statements or thoughts.

- For example, maybe you are creating a rough draft for a paper on gluten-intolerance. A weak thesis statement for this paper would be, “There are some positives and negatives to gluten, and some people develop gluten-intolerance.” This thesis statement is vague and does not assert an argument for the paper.

- A stronger thesis statement for the paper would be, “Due to the use of GMO wheat in food sold in North America, a rising number of Americans are experiencing gluten-intolerance and gluten-related issues.” This thesis statement is specific and presents an argument that will be discussed in the paper.

- Your professor or teacher may require you to create a bibliography using MLA style or APA style. You will need to organize your sources based on either style.

Writing the Rough Draft

- You may also make sure the room is set to an ideal temperature for sitting down and writing. You may also put on some classical or jazz music in the background to set the scene and bring a snack to your writing area so you have something to munch on as you write.

- You may also write the ending of the essay or story before you write the beginning. Many writing guides advise writing your introductory paragraph last, as you will then be able to create a great introduction based on the piece as a whole.

- You should also try not to read over what you are writing as you get into the flow. Do not examine every word before moving on to the next word or edit as you go. Instead, focus on moving forward with the rough draft and getting your ideas down on the page.

- For example, rather than write, “It was decided by my mother that I would learn violin when I was two,” go for the active voice by placing the subject of the sentence in front of the verb, “My mother decided I would learn violin when I turned two.”

- You should also avoid using the verb “to be” in your writing, as this is often a sign of passive voice. Removing “to be” and focusing on the active voice will ensure your writing is clear and effective.

- You may also review the brainstorming materials you created before you sat down to write, such as your clustering exercise or your freewrite. Reviewing these materials could help to guide you as you write and help you focus on finishing the rough draft.

- You may want to take breaks if you find you are getting writer’s block. Going for a walk, taking a nap, or even doing the dishes can help you focus on something else and give your brain a rest. You can then start writing again with a fresh approach after your break.

- You should also read the rough draft out loud to yourself. Listen for any sentences that sound unclear or confusing. Highlight or underline them so you know they need to be revised. Do not be afraid to revise whole sections or lines of the rough draft. It is a draft, after all, and will only improve with revision.

- You can also read the rough draft out loud to someone else. Be willing to accept feedback and constructive criticism on the draft from the person. Getting a different perspective on your writing will often make it that much better.

Community Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://www.umgc.edu/current-students/learning-resources/writing-center/online-guide-to-writing/tutorial/chapter2/ch2-13

- ↑ https://writing.ku.edu/prewriting-strategies

- ↑ https://academicguides.waldenu.edu/writingcenter/writingprocess/outlining

- ↑ http://www.writerswrite.com/screenwriting/cannell/lecture4/

- ↑ https://www.grammarly.com/blog/essay-outline/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/thesis-statements/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/editing-and-proofreading/

- ↑ https://www.grammarly.com/blog/rough-draft/

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/style/ccs_activevoice/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/revising-drafts/

About This Article

To write a rough draft, don't worry if you make minor mistakes or write sentences that aren't perfect. You can revise them later! Also, try not to read over what you're writing as you go, which will slow you down and mess up your flow. Instead, focus on getting all of your thoughts and ideas down on paper, even if you're not sure you'll keep them in the final draft. If you get stuck, refer to your outline or sources to help you come up with new ideas. For tips on brainstorming and outlining for a rough draft, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Oct 10, 2023

Did this article help you?

Eswaran Eswaran

Aug 24, 2016

Rishabh Nag

Aug 21, 2016

Oct 3, 2016

Mabel McDowell

Nov 17, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

CRWP Teachers as Writers

Ideas and Updates from Teachers Affiliated with the Chippewa River Writing Project

To Grade Rough Drafts or Not to Grade Them: One Teacher’s Journey

To grade rough drafts or not to grade them: that is the question I’ve wrestled with recently in my English teaching. Writing takes so much time to assess, especially when teaching the writing process and requesting that students revise multiple drafts of the same piece of writing. Moreover, I’ve learned over the years that students are more likely to take the writing process seriously if they are graded along the way. My own approach has been to grade first, second, and sometimes third drafts, and then record solely the final grade, but I know other teachers who opt to average the three (the better to keep students motivated in the early and middle stages of the drafting process).

I began to confront this ongoing inner wrestling when I attended the National Writing Project Midwest Conference at the University of Wisconsin – Madison, August 3rd through 5th. Jen Doucette , from the Greater Madison Writing Project, presented a workshop on assessing student writing. She teaches creative writing classes and she has eliminated assessments on writing assignments – no points, no percentages, no grades. This approach to teaching writing seemed wonderful to me at first glance, but I realized there was a distinct difference between her assessment situation and mine. She teaches an elective course in creating writing while my writing instruction takes place in ELA core classes. However, I agreed with much of her rationale for eliminating grades on writing assignments.

What do I value in student writing? I quickly scribbled a list that included the following: passion for a self-chosen topic, a clear voice that projected said passion, writing growth from first draft through final product, a nuanced understanding of the pros and cons of the topic, a well thought-out stance that included risk-taking in argument writing, solid supporting evidence, and an honest attempt to address and refute a counter-argument. Then I highlighted those areas I thought were most important. At the top of my list were passion about the topic, risk-taking, and writing growth.

Then I thought about my assessment rubric. My most valued areas weren’t anywhere on the rubric! And, ironically, my rubric encouraged writing conformity, not the risk-taking I said I wanted. Yes, the grading rubric saved feedback time, but I really couldn’t justify its use when what I emphasized in class wasn’t being assessed. While I knew that I couldn’t totally eliminate writing assessments, could I only grade final drafts, while only giving feedback on revisions? I also wondered how my students would react to working on a rough draft but receiving feedback without a grade. Would they see this as an opportunity to take a writing risk, or as a chance to procrastinate or ignore the assignment altogether? Would eliminating grades allow more learning during the process? I determined to try it, to see if I liked it as much as I thought I would.

Since I already knew that the vast majority of my students appreciate my use of essays rather than tests as summative assessments, I approached the subject of non-graded rough drafts with them confidently. I was surprised by their responses.

- They liked the rubric.

- They wrote to the rubric.

- They wrote for the grade.

- They didn’t like to revise.

- “One and done” was good enough.

I realized that I needed to shift their mindset. I knew that talking to them about preparing for college writing was a moot point for many of them since college was not in their future plans. So, I completed some quick research on the amount of clear writing needed for different careers in which they were interested: law enforcement; medical technician; entrepreneurship (beekeeping, lawn mowing/snow plowing, Etsy artist); diesel mechanic; forest ranger; prison guard; organic farmer. I spent 10 minutes talking about career options that need writing skills, but then I spent 20 minutes discussing with them how good they would feel about their writing if they honed this life skill, and could pass it on to their children. The 20-minute discussion sold them, at least the juniors and seniors, and they promised to give “no grades on rough drafts” a try. On my end, I promised lots of written feedback on drafts via Google Docs, along with even more individual conferencing.

The first assignment began in the third week of September. Students were reading The Hound of the Baskervilles , and the assignment was to use examples from Hound to support the rules of the murder mystery genre. For example, one “rule” of mysteries is that the criminal must be mentioned in the early part of the story, but must not be anyone whose thoughts the reader has been allowed to follow. Hound follows this rule because, while the criminal, Stapleton, is mentioned as a neighbor of the Baskervilles, there is no obvious motive, and Sherlock Holmes must first prove that the ghost hound is actually a living creature. Since we already had discussed the rules, and students had enthusiastically watched their choice of murder mystery on television and reported the results of the TV genre, from NCIS , Law and Order , and FBI , to TV classics such as Murder She Wrote , Bones and Elementary , they were ready to tackle the rules as found in the written texts. I supplied daily feedback by conferencing, and I spent a lovely September weekend in my sunroom writing feedback in the form of questions on their google docs rough drafts. Student response to my feedback was overwhelmingly positive.

- Since I didn’t need to worry about the grade, I could think more about the story and how it connected to the [genre] rules.

- Since there’s no grade for grammar or spelling, my thoughts could flow onto the paper easier.

- Your questions helped me to see my unclear writing spots easier.

- I think my introduction improved a lot and I felt like I could be more creative.

- Do you think, “The murderer can’t be a Chinaman” is really a murder mystery rule? (Sorry, I couldn’t resist that comment.)

- Your individual time with me helped me organize my writing better.

- Since I couldn’t follow a rubric, I had to use my brains more, to think what I wanted to prove.

Since this initial experiment at the beginning of the year, my students have written two more essays. At this point, I can report that my students have become comfortable with writing a rough draft that reveals their thinking, and that they plan to improve it as they revise it. This validates my purpose in eliminating grades on rough drafts. The students’ final products are more creative in word choice and content ideas, longer, and the students seem to be taking more pride in what they have written. And, all of them are revising more, and are willing to polish their writing more. Ended is the practice of “one and done.” I credit this change in mindset to a focus on the content and craft by the student, instead of a focus on the grade. And I am able to focus on teaching the writing practices that are most important to me: student passion about the topic, risk-taking, and writing growth. I’ve learned ‘tis nobler to focus on the feedback rather than the grade.

Deborah Meister

- Deborah Meister #molongui-disabled-link An NCTE Conference Recap

- Deborah Meister #molongui-disabled-link "Show and Tell" Using Peer Templates to Teach an Argument Move

- Deborah Meister #molongui-disabled-link From the College, Career, and Community Writers Program to the SAT Essay: A Simple Step

- Deborah Meister #molongui-disabled-link Spring Break: The Teacher’s Big Sigh

1 thought on “ To Grade Rough Drafts or Not to Grade Them: One Teacher’s Journey ”

Thank you for posting this! So helpful to read about how your students are now bigger risk takers.. and to hear about your process. Sounds like there has been growth on all fronts. Will take what you learned and put this into action with my students who are writing about landscape design history. 🙂

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Related Posts

Spring break: the teacher’s big sigh, naming the elephant: an announcement, the teachers’ kid.

Rough Drafting: Writing

- Embrace the Chaos

- Get Words Down

- Delegate to Future You

- Know Your Goal Style

- Pick Your Medium

- Set the Scene

Overview of rough drafting

The first draft of an essay or other written assessment is often referred to as the rough draft. We call it rough for a reason: it's normal for the earliest version of an essay to be disjointed, underdeveloped, or otherwise messy.

We argue that the messiness isn't just normal: it's a good thing. When you embrace the rough drafting stage as a time to explore content, test out structural options, inventory your ideas, and play with the writing, it can lead to insights you might not discover otherwise.

Guide contents

The tabs of this guide will support you in completing rough drafts of assignments and understanding how you work best as a writer. The sections are organised as follows:

- Get Words Down - Explore practical methods and suggestions to begin producing content.

- Delegate to Future You - Learn vital strategies to maintain your momentum now and simplify your editing later.

- Know Your Goal Style - Discover what makes a writing goal effective and how to follow through.

- Pick Your Medium - Reflect on the benefits and limitations of writing by hand, voice dictation, apps, and more.

- Set the Scene - Experiment with environmental factors such as company and space for maximum drafting efficiency.

Let's get started

Embracing the chaos of an imperfect rough draft can benefit your writing. Accepting this premise in theory is a start, but putting it into practice is trickier – to help you out, in this section, we will cover practical tips and approaches to get started on a rough draft.

The priority: make words happen

Many students feel self-conscious or even ashamed when their work is in a rough state. They want their writing to be engaging, logically structured, and well-supported from the very first attempt. That's a nice fantasy, but in reality, those unrealistic expectations can lead to procrastination and writing anxiety.

'Whether it's a vignette of a single page or an epic trilogy like The Lord of the Rings , the work is always accomplished one word at a time.' – Stephen King ¹

To state it rather unacademically, when we produce a first draft, our goal is to make words happen. That's it. Our goals shift as we get deeper into the process: as we transform that first draft into a second draft or the second into a third, we begin to make structural changes, refine our arguments, incorporate additional evidence, and more.

The rough draft, though? Again, this is simply where you make words happen.

Find your bearings

For most people, the writing process begins with activities like research/reading, invention, planning, and just plain thinking . Amidst all those activities, writers sometimes lose track of the assignment's specific aims. Therefore, when you sit down to begin your draft, carefully re-read the assignment prompt , first.

- Do your rough plans and ideas align with the stated goals?

- Do you understand the key content/literature well enough to begin writing? (You don't need to be 100% finished with your research – focus on whether you know enough to make a meaningful start.)

Next, study any invention or planning items you have completed (e.g. mind maps, outlines , bulleted lists, and so on). Even writers who prefer to dive right in might benefit from jotting down a few important moves they plan to make in the draft (i.e., 'Define theory of XYZ'; 'Analyse the two case studies'; 'Explain method used').

Finally, choose a general starting point for your drafting: it does not have to be the beginning! You might find it easiest to begin with the introduction , but many people prefer to draft the body of the essay first.

Draft in a natural voice

You might struggle to start drafting because you fear your words aren't good enough or 'academic' enough. It's true that academic writing should aspire to clarity, precision and accuracy; however, those qualities rarely come to fruition in the first draft. Instead, you achieve clarity, precision and accuracy as you edit subsequent drafts of the work.

Therefore, we recommend giving yourself permission to write in a natural voice while producing your first draft. This frees you to focus on what you want to say and why , rather than fretting over exactly how you will say it.

The table below identifies and illustrates some common qualities of writing in a natural voice. It then shows how the voice can be changed later with editing. [ NOTE: Some disciplines accept the use of first-person pronouns, so the first example applies only to fields where 'I', 'my', etc. are discouraged.]

If you tend to pick away at your sentences, struggling to make each one sound just right before you move to the next, you might find it challenging to adopt this freer method of drafting. We encourage you to give it a try, though. When you truly accept rough drafts as works-in-progress – subject to all manner of changes and edits, later – the focus can shift to ideas and content rather than superficial phrasing concerns.

Freewriting and freespeaking

Freewriting techniques help produce raw material for essays, and they can also kickstart your writing if the work has lost momentum. Most simply, freewriting refers to writing without stopping for a set period of time (often ten minutes). No pausing to think, no backspacing, no editing: you have to move forward and keep writing until the timer goes off.

Freespeaking follows the same premise, but you speak aloud instead of writing silently. The 'Pick Your Medium' tab of this guide shares some practical techniques for using dictation/voice methods if you wish to try this.

- Remember that the goal of drafting is to produce content, discover ideas, and make connections.

- Before you start drafting, revisit the assignment prompt and your planning/invention materials.

- Give yourself permission to write the first draft in your most natural voice.

- Consider gamifying your drafting process with some freewriting or freespeaking exercises.

An overview of placeholders

A placeholder, as the name implies, stands in place of something else within the rough draft. Using placeholders – or related techniques such as colour-coding and notes to self – not only eases the rough drafting process, but streamlines the writing activities that follow.

How placeholders work

Simply put, you can use a placeholder when you want to keep drafting for now, but know you need to return to a specific issue, later. Using a placeholder in your rough draft can help in two main ways:

- It encourages you to keep writing rather than going down a rabbit hole (i.e., getting distracted or diverted) every time an obstacle or question arises.

- It makes other writing activities like research and editing easier because you can sort your placeholders, like with like, and work systematically.

In practice, this means that you avoid disruption and draft more continuously. When you would normally be tempted to stop and make something 'perfect' (no such thing), you instead deploy a placeholder technique and keep going.

Forms and categories of placeholders

We will first explore the literal forms that placeholders can take. We will then cover common categories of use (i.e., 'stuff you flag' via a placeholder).

Typical forms

Placeholders and notes to self can take whatever form makes sense to you. Here are some good options:

- Bracketed words or abbreviations – As you're rough drafting, add a keyword or abbreviation in brackets [[LIKE THIS]] . Boldface helps it stand out. You can CTRL+F to find the brackets '[[' anywhere in your document, so it's easy to jump from one to the next as you edit later.

- Colour highlighting – You can highlight sentences/words that you definitely want to revisit. Develop a manageable coding system (i.e., yellow = 'wow that sentence is way too long,' blue = 'find a better word to use there,' etc.).

- Comments or tags – You can use the 'Comment' feature in Word to leave keywords or notes to self throughout the draft. Viewing all your comments together in the editing pane makes it easy to work through them systematically, later.

- Bullet points – You can insert a bullet point or two to mark a spot in the rough draft that needs development or additional ideas, quickly summarising what's needed alongside the bullet(s).

Common categories

As we look at some common categories of placeholders, we will use the bracketed keyword technique to illustrate them. However, you could use other methods like Word comments or highlighting to indicate the same ideas.

- Expand/develop – This is a good one to use if you have started to present a promising idea in your rough draft, but you need to reflect a while or do more research to fully develop it [[DEV. FURTHER]] .

- Fact check – A placeholder like [[FACT CHECK]] or [[ACCURATE?]] is helpful when you must return to the literature to verify something. This lets you keep drafting while guaranteeing you will remember to double-check.

- Add evidence – Use placeholders like this to mark claims you plan to strengthen by introducing evidence from the literature [[ADD LIT]] or a data set [[DATA NEEDED]] .

- Citation missing – Don't assume you will remember to add all your citations later. If a fact, idea, or data point in your draft requires attribution, leave a [[CITATION]] placeholder. Your future self will thank you!

- Move 'missing' – This one reminds you to go back and add anything you skip over in the rough draft, such as transition sentences [[MISSING transit]] , takeaway points, definitions of key terms, etc.

- Phrasing and word choices – Remember, your rough draft will be full of clunky, weird sentences: that's 100% okay, so don't try to mark every sentence with a potential issue. But if a particular sentence or word is bothering you so much that you can't move on, try adding a placeholder like [[AWK]] (for 'awkward'), [[SMOOTH]] (for 'smooth out this cumbersome phrasing'), or [[W.C.]] (for 'word choice'). Flagging it will let you feel secure enough to continue drafting.

Making it work for you

The key thing to remember is that placeholders should make your writing life easier , not harder. With that in mind, here are some questions to consider as you develop your own placeholder techniques:

Is the method logical to you ?

- Don't work against your own instincts. For example, if using different colours to mark issues feels strange and difficult to track, that isn't your method!

Is the method manageable ?

- Aim for clarity and simplicity. Creating twenty different keyword codes is comprehensive, sure, but that system will be tough to memorise and stick to. Keep it simple and consistent.

Can you easily see or find your placeholders?

- You shouldn't need to squint, zoom in, etc. Use abbreviations/punctuation you can 'find' via the CTRL+F shortcut, such as the double brackets in our earlier examples. If highlighting, colour enough text for it to stand out.

- Don't make placeholders out of words or acronyms that you use frequently in the actual writing. That will complicate any 'find' searches you do.

Does your system let you group 'like with like' and form a game plan?

- Make sure you can logically group your placeholders to simplify the next writing activities you do.

Editing's best friend

Let's say your first draft of an essay is complete. The rough draft is very rough, but that's okay: editing, supplementary research, and proofreading will whip the essay into shape. Great! But...where do you start? What needs to be done?

While drafting, we give our memories more credit than we should. Problems feel obvious to us in the moment , so we assume they will be just as obvious later on. (Spoiler: they won't be.)

This is where placeholders come to the rescue, providing a great starting point to address editorial concerns like these:

- Which claims in your draft still require data/literature to back them up?

- Have you incorporated any attributable information that still needs to be cited?

- What ideas or moves are missing from the draft (e.g. definitions, transitions, topic sentences, counterarguments...)?

- Did you feel particularly unsure about any words or phrases you used in the rough draft?

You will make changes, additions, and cuts unrelated to your placeholders, of course, but reviewing and grouping your placeholders can help you form a re-drafting and editing game plan (i.e., first, I'll do supplementary research on ABC and XYZ; next, I'll synthesize that new info into the draft; then, I'll fact-check...).

Placeholders in practice

Placeholders can be used in many writing contexts beyond academic essays: CVs, personal statements, business presentations, job performance reviews, email newsletters, wedding speeches, you name it.

In fact, we used placeholder strategies while writing the online guide you're currently reading! As shown in the below snip of the guide's overview tab, our strategies included...

- Keywords – We used a small selection of keyword tags including 'missing', 'image here', and 'example needed' to flag areas where copy or content still needed to be developed.

- Emphasis – We used brackets and caps-lock to distinguish our keyword tags from the surrounding text, with blue highlighting for further emphasis.

- Coding – We kept our coding simple, but with enough options to suit the project. Blue was only used to indicate gaps (e.g. missing text, examples, or images), for example, whereas yellow meant phrasing edits might be required.

These techniques allowed us to keep the rough draft of the webpage moving along. Rather than staring at a wall for 30 minutes agonising over what might make a good example of some idea, we typed ' [EXAMPLE NEEDED] ' and continued working on the next passage. When a good example dawned on us later, the placeholder made it quick and easy to pick back up in the correct spot.

Same draft, two approaches

If you are having trouble picturing how placeholders can ease the drafting process, let's have a look at one writer, 'Maria,' as she works on her dissertation two different ways. Click below to expand the first scenario:

Scenario #1

Maria has started drafting her dissertation but isn't getting much written so far. She has two hours to write this afternoon. She types one sentence, then types another: 'I will use an intersectional and mixed-methods approach to insure the data is fair.' She re-reads it: insure? Is that right? She pulls up Google and searches 'insure or ensure.' The first hit adds 'assure' to the mix, too! Ugh. She reads the article and decides 'ensure' is correct – but the article is on an American site, maybe it's different in the UK? She finds a UK website and, yes, it's supposed to be 'ensure.'

But now she's worried about a bigger problem: isn't 'intersectional' related more to theories she's using, whereas 'mixed-methods approach' is about her data analysis? Is she supposed to talk about those in the same sentence? Well, last week she read a study that used mixed methods, so maybe she can read that and see how they framed it. She opens EndNote...nope, not that article...not that article...not that article...okay, there it is. Except the article doesn't say anything about theories in the introduction: is Maria doing this totally wrong?

She also wrote ' I will use,' and she can't remember if her supervisor said she should or shouldn't use the first-person for her dissertation, so she pulls up Blackboard and starts digging through folders to see if there's a handbook or something. Eventually she remembers that information was shared via email, not Blackboard, so she opens Outlook. Before she can find the email from her supervisor, Maria sees an email she sent to herself yesterday, with an article attached that she thought could be relevant to her dissertation. She opens the article and starts reading it...then keeps reading it...then remembers to search for that supervisor email...but nope, she can't find it. Forget it. She pulls up Word again and deletes the whole sentence.

At the end of Maria's two-hour 'rough drafting' session, she has written precisely... one sentence.

Maria probably doesn't feel great about that writing session. She bounced between many discrete activities in the writing process: rough drafting, proofreading, researching, analyzing assignment parameters, more researching, etc.

Some writers can get the work done while bouncing around in this way, but for many of us, it's more efficient to identify the nature of each writing session and stick to it. For example: 11:00-12:00 is rough drafting; 12:00-13:00 is lunch; 13:00-14:30 is research time; break; 15:00-16:00 is rough drafting.

What if Maria were to use some placeholder techniques? Click below to see how that might work.

Scenario #2

Maria has started drafting her dissertation but isn't getting much written so far. She has two hours to write this afternoon. She types one sentence, then types another: ' I will use an intersectional and mixed-methods approach to insure [W.C.] the data is fair.' Maria can't remember if first-person pronouns are permitted, so she highlights that phrasing. She always mixes up insure and ensure , so she adds 'W.C.' for 'word choice.' She will check on those things later.

She knows she needs to expand on those ideas, so she continues typing, 'In terms of the project, intersectional refers to the theoretical lenses I am applying. I will analyse the interviews through not only a feminist lens [SPEC?] but the social model of disability, too, which posits that [QUOTATION/CITATION]. ' The 'SPEC' note is a placeholder because Maria is deciding between two particular theorists: she'll get more 'SPECIFIC', later. She remembers circling a short but helpful definition of the social model of disability in an article, but she doesn't want to get distracted pawing through EndNote, so she adds a placeholder and keeps writing...and keeps writing...

At the end of Maria's two-hour rough drafting session, she has written five paragraphs.

Maria should feel great about this writing session! She will need to revisit those five paragraphs and do considerable editing, later, but the point to remember is that you can't improve what doesn't yet exist.

Moreover, the placeholder and colour-coding techniques that Maria has deployed will make it easier to coordinate her approach to editing. She can group related placeholders (e.g. notes to cite some literature; notes to check word choice; etc.) and focus on one similar set of actions at a time, making the process efficient.

- Placeholders can help you push forward with a rough draft instead of letting perfectionism or worry win out.

- There are different ways to use placeholders and notes to self: play around to build a system that works for you.

- These techniques are valuable not only for producing the rough draft, but for the re-drafting and editing processes .

The power of mini-goals

With written assignments, don't think in terms of one big goal, i.e., 'Finish and submit essay by 15th January.' Instead, use mini-goals to ensure you are making enough progress to hit incremental or staggered deadlines.

Mini-goals when rough drafting are generally quantity-based, time-based, or content-based. On this page, we'll explore how those goal setting options work, including the potential benefits and drawbacks; then we will cover ways to hold yourself accountable to goals.

Quantity-based goals

With this approach, you aim to draft a certain number of words, lines/sentences, paragraphs, or pages per writing session or per day. If a 1,500-word essay is due in a few weeks, for example, you could research during the first week, then draft 300 words per day (Monday to Friday) in the second week. This would give you a 1,500-word rough draft, with one more week remaining to re-draft and edit.

If typing your rough draft, you can use 'word count' features to track your progress. If writing by hand, a paragraph or page target will be easier to follow.

- PROS – Quantity goals compel you to actually write rather than sitting there overthinking. Breaking a big project like a 10,000-word dissertation into little 'chunks' (draft two paragraphs today; draft 150 words tomorrow; etc.) keeps you on track and makes the work feel more manageable.

- CAUTION – Shift gears if too many writing sessions lead only to 'fluff' or filler material while using quantity-based goals. This might signal the need to try a different goal method; it could also mean you need to engage in more invention activities or research before rough drafting.

Time-based goals

With this approach, you aim to rough draft for specific amounts of time. Plan your week in advance, setting realistic goals for each day by considering your other obligations, where you will be, anticipated energy levels, etc.

If you will be drafting for an hour or more, use a Pomodoro timer to break the time goal into shorter chunks with breaks between. For example, 'two hours of drafting' could be reframed as 'four 25-minute Pomodoro cycles.' See the quick video below for an explainer on this technique.

- PROS – Time-based goals help you integrate drafting practices into your daily and weekly routine, which can gradually transform writing from 'random, stress-spiking intrusion' to 'normal habit.' Scheduling the decided goal into your calendar ups the odds that you will sit down to write during the blocked-out time.

- CAUTION – Shift gears if you are leaving too many so-called 'writing sessions' without having written (i.e., you 'wrote for two hours' yesterday and 'wrote for three hours' today, but have four sentences to show for it). Try combining a quantity-based or content-based goal with your time goal to remind yourself to make words happen .

Content-based goals

Students can use content-based goals for any assignment, but this method becomes crucial with extended writing at the postgraduate level . Why? Simply put, the bigger a writing project is, the more likely you are to stare at the blank page and say, 'I have no idea what to write today.'

It's important to develop a solid outline or mind map for this method because you build your mini-goals around achieving specific 'moves' or tackling specific content/ideas . That word 'specific' is key, as you can see in the examples below:

BAD content-based goal: In today's writing session, I will work on my literature review.

GOOD content-based goal: In today's writing session, I will synthesize three different scholars' definitions of the term 'viral marketing.'

Just reading the first goal feels overwhelming: 'work on' is vague, and 'literature review' is far too broad to provide meaningful direction. The revised goal specifies the move the writer will make: synthesis (i.e., critically weaving together multiple sources). Additionally, it specifies the content/idea the writer will cover: the definition of 'viral marketing.'

To reiterate, content-based goals won't work unless you have some idea where the writing is headed, so invest time in invention and organisation activities.

- PROS – Building your mini-goals around writing moves and content/ideas helps keep your rough drafting relevant, making this a good choice for writers who tend to stray from the assessment brief. You enter each drafting session with a clear idea of what you need to accomplish.

- CAUTION – An overly rigid approach to content-based goals can prevent exploration of important insights that arise when you are rough drafting, so take time to reflect between each goal in case your plan needs to evolve.

But I don't wanna... (i.e., accountability)

If you are one of those magical people with a magically healthy sense of magical self-motivation...well, good for you! Skip this section. For the rest of us mere mortals, sticking to our writing goals can be a challenge. Here are some ideas to help:

Get it in your calendar as a real thing