The Interpreter Foundation

Supporting the church of jesus christ of latter-day saints through scholarship.

The Role and Purpose of Synagogues in the Days of Jesus and Paul

- Article Formats:

[Page 41] Abstract: This article explores why Jesus so often healed in synagogues. By comparing the uses and purposes of Diaspora and Palestinian synagogues, this article argues that synagogues functioned as a hostel or community center of sorts in ancient Jewish society. That is, those needing healing would seek out such services and resources at the synagogue.

What were synagogues like in Palestine 1 during the time of Jesus? What were synagogues like in the Roman world during the time of Paul? Why is the synagogue a place where people can be healed? Why does Jesus do so much healing at the synagogue? Why not do the healings elsewhere? This article explores why Jesus so often healed in synagogues.

A careful reading of the New Testament suggests that synagogues played an important role in the ministries of Jesus and Paul. Synagogues provided the contextual backdrop for Jesus’s stunning Messianic announcement and his acts of healing and teaching. For Paul, synagogues constituted a staging ground for preaching the gospel message and may have been a place of lodging when first arriving to town. Hence, understanding more fully the physical configuration and social purpose of ancient Palestinian and Diaspora synagogues will provide contextual meaning of synagogical references in the New Testament, specifically why Jesus healed at synagogues.

[Page 42] Jesus and Palestinian Synagogues

When we think of Judaism, synagogues are a natural component. Though we may have a general familiarity with these Jewish houses of worship as they exist in our own day, the picture in Jesus’s day was quite different. 2

Throughout the Gospels we hear stories of Jesus entering into synagogues to read scriptures, to teach, and to heal. Indeed, the Gospel of Mark records that Jesus’s first act after making the announcement of his missionary purpose 3 was to go to the synagogue to teach and to heal (see Mark 1:21-27). Similarly, the Gospel of Luke teaches that Jesus first revealed his divine mission while at a synagogue after reading a passage from Isaiah. Because the synagogues were central to Jewish community life during the time of Jesus and during the time of the synoptic writers, we see the gospel writers share a variety of crucial stories about Jesus that are situated at the synagogue. Given the prominence of synagogues in the world of Jesus, we would do well to learn more about them.

Studying synagogues in first century Palestine (or in the first century Diaspora, for that matter) is not a simple and straightforward undertaking. Though the institution today is synonymous with Judaism and has been for more than 1800 years, the available evidence on first century Palestinian synagogues is not abundant. Nevertheless, we do have sufficient evidence about ancient synagogues to paint an intriguing and valuable contextual picture through which we can enhance our understanding of Jesus’s activities associated with them. Even though the temple was the focal point of Jewish religious life during the time of Jesus, synagogues played an essential role in Jewish communities and an important role in the lives of Jews who lived in gentile communities.

Before we turn our eyes to the first century evidence on synagogues, it may be helpful to consider what we know about the origins of synagogues prior to the time of Jesus. 4 This question entails a definition of the word [Page 43] synagogue. “Synagogue” is formed from the Greek word ago (to lead, bring along) and the preposition sun- (together). When these two words are combined, they create the word “synagogue,” which in its technical sense means “to gather in, collect, assemble.” In Greek literature, “synagogue” refers to a gathering of things (e.g., boats, produce, ideas, etc.) or people (e.g., an assembly or meeting). What is important to recognize here is that “synagogue” in its earliest usages did not refer to a physical location, especially not to a building. In fact, it was as a result of the gathering of Jews into assemblies, for which purposes they only later built structures, that the word “synagogue” eventually evolved from indicating the act of gathering together to referencing the physical location or building where the gathering took place. 5 Though the Jerusalem temple, before the Romans destroyed it, was the major focal point of Jewish religious life, synagogues functioned as community centers that could support the spiritual and physical needs of those in the community.

The earliest evidence we have of synagogues is from inscriptional references in Egypt from the second and third century BCE. 6 Now, these assemblies were not always necessarily for religious purposes. In fact, at this early period, the term synagogue referred to a gathering for the purpose of conducting community or public affairs. Centuries later the primary purpose of synagogues centered on religious activities. Originally, synagogues were multi-purpose public community gatherings. 7

[Page 44] Fortuitously, physical evidence of Palestinian synagogues near the time of Jesus exists. 8 Four locations in Palestine present unmistakable archaeological evidence that they once contained a first century Jewish synagogue: Jerusalem, Gamla (in the Galilee), Masada (the Herodian fortress near the Dead Sea), and Herodium (another Herodian fortress about 7.5 miles south of Jerusalem). 9 Though other archaeological sites suggest the existence of first century Palestinian synagogues, the evidence is not as certain. 10

What do the archaeological reports tell us about each of these sites? Architecturally, they have shared features. First, these sites are built in rectangular fashion with seats lining the walls so everyone is essentially facing the center of the synagogue. This configuration enables the congregants to clearly see anyone who stands to read or speak and have immediate visual access to all other congregants. Second, the door of the synagogue is oriented toward Jerusalem, so as worshippers leave the synagogue, they do so as if embarking upon a pilgrimage to the Holy Temple in Jerusalem. Third, these sites have Mikvaot (ritual washing areas) associated with the synagogue building. And fourth, rudimentary genizahs, which are repositories for old and worn-out scriptures, have been found at these sites. 11

[Page 45] What do we know of the activities that occurred in the synagogues? The Theodotos inscription, which likely predates 70 CE, discovered in a 1913–1914 archaeological dig of the City of David (just south of the Jerusalem Temple Mount), offers an interesting list of purposes and activities provided at the synagogue. According to that list, activities in synagogues included reading the law and instructing, and the structure provided lodging for strangers, facilities for dining and water, and hostel services. 12 The first two activities are unremarkable to us as they relate to what we commonly imagine Jesus doing in the synagogues. I already noted that Jesus instructs the crowd gathered at the synagogue concerning his mission after reading from the scriptures (see Luke 4:15–21).

What is remarkable about this inscription is the other activities listed, which are seldom if ever associated in our minds with the synagogue, namely the stranger’s lodgings, hostel services, and dining and water facilities. Jesus’s work of healing and miracles at synagogues becomes unquestionably clear and expected if we listen to the words of the Theodotos inscription. 13 A study of the Gospels indicates that on several occasions Jesus heals people at the synagogue. 14 No one disputes that healing in the synagogue is an appropriate and legitimate activity. Notice that no one gets upset with Jesus for where he heals, such as the synagogue. However, when Jesus conducts his healings is a matter of dispute. Healing on the Sabbath is a sacrilege according to some (see John 5:1–18). Similarly, in the Gospel of Luke the ruler of the synagogue angrily told the people to return to the synagogue on a day other than the Sabbath to be healed, “And the ruler of the synagogue answered with indignation, because that Jesus had healed on the sabbath day, and said [Page 46] unto the people, There are six days in which men ought to work: in them therefore come and be healed, and not on the sabbath day” (Luke 13:14).

Why would people in need be at the synagogue? What better location to receive food, water, and lodging? Hospitals and care hospices as we know them did not exist in the ancient world. However, rudimentary hospitals (edifices dedicated to Asclepius), hospices, and ancient inns did exist throughout the Mediterranean world where people could receive such services. In ancient Jewish communities it may be that synagogues served as a gathering place not just for community purposes, but also for the community to care for those who required special assistance. What better location for Jesus to find the sick, the afflicted, the lame, and the downtrodden than at the ancient community center? Note, however, that Jesus also found and healed the sick, the afflicted, the lame, and the downtrodden at the Jerusalem temple. The temple of Jerusalem and the synagogues scattered throughout the land of Israel both seem to have attracted the needy in their respective communities. This may suggest why the Gospel writers often locate Jesus healing at a synagogue when he was not in Jerusalem, but when he was in Jerusalem, he healed at or near the temple instead of the synagogue.

Additionally, if ancient synagogues did function in part as a place for the needy, physically afflicted, and foreigners to gather for wellbeing, Jesus’s announcement of his mission in Luke 4:16–21 becomes all the more remarkable. 15

And he came to Nazareth, where he had been brought up: and, as his custom was, he went into the synagogue on the sabbath day, and stood up for to read. And there was delivered unto him the book of the prophet Esaias. And when he had opened the book, he found the place where it was written, The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he hath anointed me to preach the gospel to the poor; he hath sent me to heal the brokenhearted, to preach deliverance to the captives, and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty them that are bruised, To preach the acceptable year of the Lord. And he closed the book, and he gave it again to the minister, and sat down. And the eyes of all them that were in the synagogue were fastened on him. And he began to say unto them, This day is this scripture fulfilled in your ears. (Luke 4:16–21)

[Page 47] Of significance is that Jesus’s mission is to “preach the gospel to the poor” and to “heal the brokenhearted, to preach deliverance to the captives, and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty them that are bruised.” Jesus’s healing miracles at the synagogue fulfill this mission statement. Again, if anciently, synagogues played a role as a gathering place for the needy, both spiritually and physically, it is therefore perfectly appropriate contextually that Jesus first proclaims his mission to the needy at the synagogue and performs many of his acts of compassions on behalf of the needy at the synagogue — the ancient Jewish community center.

A few final notes on ancient Palestinian synagogues as physical structures provide intriguing possibilities. Recently, it has been proposed that synagogues, in addition to the other purposes highlighted above, were built as a geographical and symbolic extension of the Jerusalem temple. 16 The temple was rectangular in shape; so too were the synagogues. The outer walls of the temple enclosure (not the temple itself) contained step seating; so too did the synagogues. The temple was ringed by columns through which a worshipper could observe the procession of the sacrifice he had handed over to the temple priest; so too in the synagogues, congregants viewed the proceedings from between the columns that ringed the synagogue. Finally, the location within the synagogue where individuals read from the scriptures may have been physically analogous to the location of the altar at the temple. Just as one found communion with God in the temple at the altar of worshipful sacrifice, so too, reading the word of God was an act of worship that brought communion with Him.

In summary, the physical presence of a building for the Jewish community to gather served important purposes in the ministry of Jesus. It was at the synagogue that Jesus found an immediate audience accustomed to the procedures of public scripture reading and exposition. But even more surprisingly to us, perhaps, it was at the synagogue that Jesus found those in great need through whom he could publicly display with miracles that the Kingdom of God had indeed arrived.

Paul and Diaspora Synagogues

Similar to the evidentiary challenges we face when trying to reconstruct knowledge concerning first century Palestinian synagogues, so too is our experience when we cast our attention to first century Diaspora [Page 48] synagogues. Despite meager evidence, we do have sufficient to build a case for what Diaspora synagogues looked like and how they were used. 17

We can produce our summary from the two most ancient Diaspora Jewish synagogues for which we have physical evidence. They are located first on the Greek island of Delos 18 and second at ancient Ostia, 19 on the Tyrrhenian coast of Italy, not far from Rome’s modern day Leonardo da Vinci-Fiumicino International Airport. 20 Some of the remarkable physical features of the earliest Diaspora synagogues are the stepped seating built into three of the four walls and the Jerusalem- oriented entrance. Though a universal architectural plan for ancient synagogues never existed, the synagogues at Ostia and Delos share striking resemblance to synagogues in Palestine. Therefore, what we learned from first century synagogues in Palestine applies to Diaspora synagogues as well. The seating arrangement provided everyone unobstructed visual access to each other, truly creating a sense of community and brotherhood. Additionally, the entrance facing toward Jerusalem served as a constant reminder that the synagogue represented a geographical and symbolic extension of the holy temple in Jerusalem, similar to the first century Palestinian synagogues.

In addition to sharing physical features, Diaspora synagogues shared purposes similar to their counterparts in first century Palestine: ritual bathing, scripture reading and exposition, prayer, festivals, holy-day and communal dining, treasury, museum, documentary archive and school, refuge, manumission, council hall, court, and society house. 21 Notice that only a small portion of the synagogue’s purposes constituted what we would consider to be religious activities. As a friend helpfully reminded me as I wrote this, in the ancient world there was no distinction between [Page 49] the secular and religious. Everything was on a continuum of a religious spectrum. Therefore, these synagogue buildings, like their Palestinian counterparts, truly were multi-purpose community centers.

In our day it would strike us as strange to have an itinerant preacher from a different religious sect show up at one of our religious meetings and there be granted carte blanche to speak. When we recognize the centrality of the synagogue in Jewish Diaspora community life, it is only natural that we find Paul and other early Christian missionaries integrating themselves among established Jewish communities by means of the public synagogue. 22 As a community center, it may be possible that Paul and others made use of the synagogue’s lodging services when they first arrived at the town as they sought to establish more permanent housing and income. 23

That synagogues were more community centers than religious centers helps us also to understand why non-Jewish Greeks are in the audience when Paul preaches in the Jewish synagogue at Iconium (see Acts 14:1– 5). Additional evidence unearthed by archaeologists reveals dedicatory inscriptions for synagogues made on behalf of “God-fearing” gentiles, non-Jews who believed and worshiped God as did the Jews but never fully converted to the practices of Judaism (such as being circumcised). Though it may sound strange to our ears that a non-member would provide the monetary means to build and support a church building, synagogues were esteemed as community cultural centers, and so it was a badge of pride to be named as patron of such an important community institution, regardless of one’s religious sentiments. 24

There is one final feature characteristic of some early Jewish Diaspora synagogues that needs to be considered — they were built or modified from pre-existing non-public structures or private homes. 25 A similar [Page 50] phenomenon occurred as Christianity spread throughout the Roman Empire. Early church members first met in private homes, often of a wealthy member or patron who may have also served in a leadership position. Over time as the Christian population grew, as meetings became more formal, and as church institutional structure became more pronounced, Christians began converting private homes into formal meeting places. I mention this phenomenon of early Christianity as a reference point to share that Diaspora Judaism followed a similar trajectory in many instances. As Jews settled throughout the Roman Empire, they would initially gather in private homes for community or religious activities. Then, as their population grew and their wealth increased, they would modify the existing private home used for meetings into a more formal community structure — the synagogue. 26 That Paul established Christian house-churches in various cities may simply be indicative of practices common in his day, especially among his Jewish contemporaries.

Though ancient Jewish synagogues scattered across the Roman Empire did play a religious role for community gatherings in the time of Jesus and Paul, perhaps similar to the way modern members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints view their meeting houses, ancient synagogues had multiple purposes and functions serving as a community center for local Jewish groups. In addition to their spiritual role of providing a location to pray and read and interpret scriptures, ancient synagogues also provided services to meet the physical needs of people, offering them shelter and food while traveling, a place to gather for social events, and a place to receive healing. Recognizing the [Page 51] multi-purpose nature of these buildings helps to provide a compelling context for New Testament passages depicting Jesus and Paul conducting their ministry activities. Synagogues, then, would have been the perfect place to fulfill Isaiah’s Messianic prophecy, quoted when Jesus announced his Messianic mission, “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he hath anointed me to preach the gospel to the poor; he hath sent me to heal the brokenhearted, to preach deliverance to the captives, and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty them that are bruised, To preach the acceptable year of the Lord” (Luke 4:18– 19; see also Isaiah 61:1–2).

New Testament references to synagogues:

Matthew 4:23; 6:2, 5; 9:35; 10:17; 12:9; 13:54; 23:6, 34. Mark 1:21, 23, 29, 39; 3:1; 5:22, 35-36, 38; 6:2; 12:39; 13:9. Luke 4:15–16, 20, 28, 33, 38, 44; 6:6; 7:5; 8:41, 49; 11:43; 12:11; 13:10, 14; 20:46; 21:12. John 6:59; 9:22; 12:42; 16:2, 18:20. Acts 6:9; 9:2, 20; 13:5, 14–15, 42; 14:1; 15:21; 17:1, 10, 17; 18:4, 7-8, 17, 19, 26; 19:8; 22:19; 24:12; 26:11. Revelation 2:9; 3:9.

Go here to see the 4 thoughts on “ “The Role and Purpose of Synagogues in the Days of Jesus and Paul” ” or to comment on it.

Pin it on pinterest.

Jews Behavior in Synagogue Essay

Culture and religion are social factors that have significant influence on how individuals behave in the society. Analysis of various cultures and religions indicates that they have unique beliefs and traditions. The existence of varied traditions and beliefs affects intercultural communication among people from diverse cultural and religious backgrounds.

People from diverse cultural and religious backgrounds find it hard to communicate, interact, or worship together because they do not share the same language, traditions, and beliefs. Therefore, this essay examines how Jews behave in their synagogues relative to other cultures and religions.

To examine Jewish culture and religion, my friend and I visited an Orthodox synagogue during the time of worship, which is usually on Saturday ( Shabbat ). We stayed in the synagogue during the time of worship, from 8am to 12pm. The experience of attending a church service in a synagogue enriched us because we learned about Judaic beliefs, Jewish culture, and behaviors of Jews during worship. What surprised us was the separation of men and women in the synagogue.

Men and women entered into the synagogue through different doors and sat in their respective sections. The reason for separating women and men in the synagogue is to enhance their focus on worship and avoid discrimination based on marital status (Moss, 2013). Before visiting the synagogue, I did not know that Jews separate men and women as in the case of Muslims in their mosques. In this view, I noted that Jews and Muslims share the aspect of gender separation.

Since men and women were in separate sections of the synagogue, they were interacting with each other. Judaic beliefs prohibit congregation from turning the Shabbat, the day of worship, into a social event. Thus, the congregation kept quiet as it listened to the sermon of the day. In the synagogue, Judaic beliefs prohibit applause, use of cell phones, and cameras because they cause disturbances in the holy sanctuary.

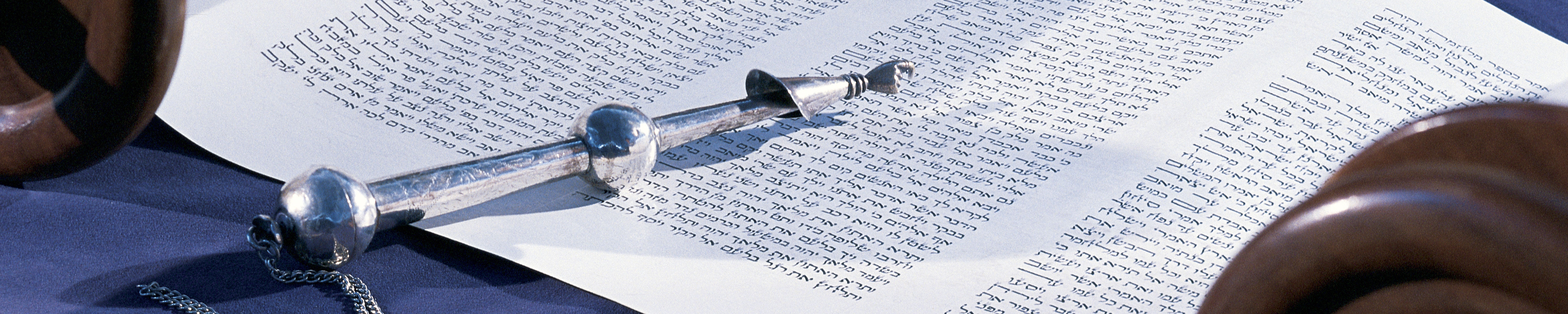

When sermon started, the congregation bowed towards the Ark to honor the removal of holy book, the Torah . Additionally, no one was allowed to enter into or go out of the synagogue when the Ark was opened and the Torah removed. Such beliefs make synagogues to be unique places of worship, since people are not at liberty to perform activities that they want. After the sermon, people interacted freely because restrictions were only applicable in the synagogue.

Dressing code in the synagogue was a unique thing that I noticed in the synagogue. Given that the synagogue is a holy place, I noted that men wore suits while women wore dresses, which made them to appear decent. According to Strassfeld and Strassfeld (2012), men should wear a kippah on their head, while women should cover their hair with a headscarf.

The covering of the head signifies humility and acceptance of God as the head of the synagogue. Thus, I observed that all the people in the synagogue dressed well and covered their heads according to Jewish and Judaic beliefs.

The experience of visiting the synagogue on Shabbat enhanced my knowledge about Jewish culture and religion. Gender separation, covering of heads and decent dressing code are some of the Judaic practices in synagogues that are similar to Islamic practices in mosques.

The experience of the synagogue stretched my comfort zone since I thought that Islam and Judaism are distinct religions that do not have anything in common. Therefore, the experience gained and observations made in the synagogue have enhanced my intercultural knowledge, and thus have promoted my intercultural communication.

Moss, A. (2013). Separation in the Synagogue . Retrieved from https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/160962/jewish/Separation-in-the-Synagogue.htm

Strassfeld, R., & Strassfeld, S. (2012). Entering a Synagogue . Retrieved from https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/entering-a-synagogue/

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, March 31). Jews Behavior in Synagogue. https://ivypanda.com/essays/jews-and-synagogue/

"Jews Behavior in Synagogue." IvyPanda , 31 Mar. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/jews-and-synagogue/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Jews Behavior in Synagogue'. 31 March.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Jews Behavior in Synagogue." March 31, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/jews-and-synagogue/.

1. IvyPanda . "Jews Behavior in Synagogue." March 31, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/jews-and-synagogue/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Jews Behavior in Synagogue." March 31, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/jews-and-synagogue/.

- Jewish Synagogue Experience

- The Dura Europos Synagogue

- What Is Shabbat (Jewish Sabbath)?

- Judaism as an American Religion

- Comparing World Religions Through Observation

- Jewish Religious Worship Features

- History of Judaism Religion

- World Religions: Judaism, Shintoism, and Islam

- Judaism and Taoism: Comparison and Contrast

- Pope John Paul II and the Jewish People

- The Bhagavad Gita: The Role of Religion in Relation to the Hindu Culture

- The Importance of the clothing in Different Religious Groups

- Summary of the Eucharist by Robert Barron

- Idolatry of Christianity

- Christian Theological Entities

What Is the Purpose of the Synagogue?

D'Var Torah By: Rabbi Jonathan E. Blake

The Hebrew term for synagogue is beit k'neset. It means "house of assembly" and thus approximates the Greek word ' synagoge' which also means "assembly." For centuries, the synagogue functioned primarily as the ancient world's idea of a "JCC," a place for Jews to assemble. These institutions dotted the Jewish landscape even while the Second Temple-shrine of our ancient worship-stood. The synagogue of antiquity might have struck us as surprisingly "secular" in orientation. Originally, people may not have come to the synagogue primarily to pray or study. They conducted local business in the synagogue, promoting the general welfare of the Jewish community. Accelerated by the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE, synagogues evolved to absorb many of the ritual and religious observances of an emergent Rabbinic Judaism. Over time the beit k'neset also became a beit t'filah , a "house of worship," and often a beit midrash, a "house of study," too.

The archetype of the synagogue, the Tabernacle that constitutes the focal point of the wandering wilderness community, completes construction in Parashat P'kudei. " In the first month of the second year, on the first of the month, the Tabernacle was set up" (Exodus 40:17). The text credits Moses with erecting the completed structure and arranging all of its fixtures, beginning with its planks and posts, and concluding with the screen covering the outermost gate. "When Moses had finished the work, the cloud covered the Tent of Meeting, and the Presence of the Eternal filled the Tabernacle" (Exodus 40:33-34). The Tabernacle, spiritual antecedent of the synagogue, is complete. The text signals God's satisfaction with the work when God's Presence enters the structure. Over the Tabernacle a cloud rested by day, and fire would appear in it by night, as a constant, visible reminder of God's nearness and as a guiding presence for the Israelites' journeys (Exodus 40:36-38).

That human beings have successfully brought God into their midst through the construction of a sacred sanctuary marks a dramatic shift in ancient Near Eastern mythology. The Mesopotamian Epic of Creation is typical in its depiction of the gods creating their own dwelling place on earth, here to be named Babylon:

The Anunnaki [Babylonian deities] began shoveling. For a whole year they made bricks for it.When the second year arrived, . . . they had built a high ziggurat for the Apsu [other deities]. (Tablet VI, from Myths from Mesopotamia, trans. Stephanie Dalley [New York: Oxford University Press, 1989], p. 262)

The Torah, in contrast, imagines human beings teaming up to fashion earthly materials (precious woods, metals, fabrics) into a place where God's Presence will abide. The inversion is poetic and brings God's work of creation full circle. In the first chapter of Genesis, God creates a home for human beings to inhabit. In the last chapter of Exodus, human beings, Israelites charged with a holy purpose, create a home for God to inhabit.

This image invites us to return to our original question: "What is the purpose of a synagogue?" Ultimately the answer is, "To make God's Presence noticeable."

Sometimes the architecture itself can achieve this. Certain synagogues through purely physical means can elicit spiritual inspiration. Some sanctuaries through their sheer magnitude can inspire a feeling of awe; others achieve this effect through opulent materials, beautiful art, and carefully designed lighting and sound. Other spaces strive for intimacy or warmth. Natural light and windows that open to the world provide a different kind of inspiration than representational art or stained glass. Still other synagogues evoke the glory of Jewish history or images from the Bible and thus may both instruct and inspire. Many people report that a synagogue's architecture helps them feel God's Presence.

However, the synagogue must also make God's Presence noticeable through other means. A famous midrash proposes that it was only through the meritorious behavior of humanity, culminating in the deeds of Moses, that God--long since alienated from the human realm by our transgressions--could return to earth and dwell among us ( P'sikta D'Rav Kahana, Piska 1:1).

God migrates to and from the world of human affairs in accordance with our ethical attentiveness or inattentiveness. Behavior matters more than a building. Indeed, the fulfillment of mitzvot on behalf of others, compassionate action for people in pain, and tzedakah for people in need can all make God's Presence more noticeable in the world. And the synagogue is the primary Jewish engine for organizing people into communities of caring.

Study, prayer, ritual observance, community building, tzedakah , concern for the welfare of all Jews and all humanity--these constitute the pillars of a thriving, inspirational synagogue. Every time I see our congregation reach out with a loving embrace, with hot meals and gentle words, to a family walking in the valley of the shadow of death, I see the synagogue making God's Presence noticeable. Every time I see congregants awaken to a new insight during Torah study, I see how the synagogue has helped make God's Presence noticeable. When youths and adults felt inspired a few weeks ago to travel on a local Jewish relief mission to New Orleans, I saw our synagogue making God's Presence noticeable. When we sing our Kabbalat Shabbat service on Friday night and even the people struggling with Hebrew are moved to sing along for L'chah Dodi , I see the synagogue making God noticeable.

Jewish mystical tradition claims that God is everywhere and in all things, if only our vision permits us to see. The shattering daily news makes it too easy to conclude that we live in a godless world. Our parashah endorses the vital role of the synagogue in restoring our faith in a world in which God's Presence abides. The synagogue functions as a spiritual magnifying glass. It helps us to see what has been there all along.

Rabbi Jonathan E. Blake is senior rabbi of Westchester Reform Temple in Scarsdale, New York.

Daver Acher By: Helene Ferris

Rabbi Blake so poetically describes the purpose of our present-day synagogue and mentions Moses's critical role in building its prototype, the Tabernacle, in the wilderness. But how was Moses able to accomplish such a prodigious task? Although Moses did not grow up in an Israelite culture, he was able to duplicate the strengths of the patriarchs on his own.

Moses learned his passion for justice from Abraham. Abraham pleaded with God in defense of the innocent of Sodom and Gomorrah (Genesis 18:20-33); Moses defends the innocent Hebrew slaves, killing the Egyptian taskmaster (Exodus 2:11-12). And seeing two Hebrews fighting, he upbraids the wicked one (Exodus 2:13).

With his life at stake Moses flees into the wilderness, as Jacob had fled from Esau (Genesis 28:5, 10). His adventures parallel those of Jacob. As Jacob met his beloved Rachel at a well (Genesis 29:9-11), Moses meets Zipporah (Exodus 2:16-17). Moses works for his father-in-law and becomes, like Jacob (Genesis 29:20, 30), a stranger in a strange land with the strength to endure and prosper as an outsider.

Moses also has a link to Isaac. Isaac and Moses each have only one wife, one love; and both, though in different ways, resign themselves to a higher cause.

Only after Moses has internalized the life experiences of the patriarchs does God hear the groaning of the Children of Israel and reenter Jewish history, remembering the covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (Exodus 3:6-7). Moses is the agent through which the covenant is carried forward. To lead God's people from Egypt to Sinai and back to the Promised Land-to transform a tribe of slaves into a free people possessing a covenant with God and building a sanctuary to remind them of that covenant-required a leader with the moral stance of Abraham, the self-sacrificing resignation of Isaac, and the wily heroism of Jacob.

But for me the greatness of Moses lies beyond his embodiment of the best of our patriarchs-even beyond his faith and patience and the willingness of the people to believe in him. His greatness lies in his ability to believe in the people. If a leader does not believe in the potential greatness of those he or she is leading, then true greatness will never be realized. Moses believed in the people Israel; therein lay his prodigious greatness.

Rabbi Helene Ferris is rabbi emerita of Temple Israel of Northern Westchester in Croton-on-Hudson, New York.

" P’kudei , Exodus 38:21-40:38 The Torah: A Modern Commentary , pp. 680-690; Revised Edition, pp. 627-636; The Torah: A Women's Commentary , pp. 545-566"

- P'kudei

When do we read P'kudei

D'var torah author.

Rabbi Jonathan Blake (he/his/him) is the senior rabbi of Westchester Reform Temple in Scarsdale, New York.

Daver Acher Author

P'kudei commentaries, related podcasts.

- On the Other Hand: Ten Minutes of Torah -- P'kudei: Spirituality and Art

- English Translation of P'kudei

Make a Special Passover Gift

Together, we will champion the lessons of Passover by bringing greater wholeness, justice, and belonging to our world.

Trending Topics:

- Say Kaddish Daily

- Passover 2024

What To Expect At Synagogue Services on Saturday Morning

A guide for bar/bat mitzvah guests and other newcomers to Sabbath worship.

By Rabbi Daniel Kohn

Knowing what to expect ahead of time will ensure that your experience is a comfortable and positive one. While this article focuses on what to wear and do — and some of the people you will see — we recommend you also consult our Guided Tour of the Synagogue and Highlights of Shabbat Morning Worship .

Keep in mind that services (and service lengths) vary widely from congregation to congregation, depending on a synagogue’s denomination (Orthodox, Conservative, Reform etc.), its leadership and its unique customs or traditions. Dress codes — and attitudes about small children and whether or not it is acceptable to whisper with your neighbor — also vary widely. To learn more about the particular synagogue you will attend, you may want to consult its website or speak to a friend who is a member or has been there recently.

General Expectations for Synagogue Behavior

1. Dress : Guests at a bar/bat mitzvah celebration generally wear dressy clothes — for men, either a suit or slacks, tie, and jacket, and for women, a dress or formal pantsuit. In more traditional communities, clothing tends to be dressier; women wear hats and are discouraged from wearing pants.

2. Arrival time: The time listed on the bar/bat mitzvah invitation is usually the official starting time for the weekly Shabbat , or Sabbath, service. Family and invited guests try to arrive at the beginning, even though the bar/bat mitzvah activities occur somewhat later in the service; however, both guests and regular congregants often arrive late, well after services have begun.

3. Prayer shawl: The tallit (tall-EET or TALL-is) , or prayer shawl, is traditionally worn by Jewish males and, in liberal congregations, by Jewish women as well. Because the braided fringes at the four corners of the tallit remind its wearer to observe the commandments of Judaism, wearing a tallit is reserved for Jews. Although an usher may offer you a tallit at the door, you may decline it if you are not Jewish or are simply uncomfortable wearing such a garment.

WATCH: How to Put on a Tallit

4. Kippah, or yarmulke : A kippah (KEEP-ah) or head covering (called a yarmulke in Yiddish ), is traditionally worn by males during the service and also by women in more liberal synagogues. Wearing a kippah is not a symbol of religious identification like the tallit, but is rather an act of respect to God and the sacredness of the worship space. Just as men and women may be asked to remove their hats in the church, or remove their shoes before entering a mosque , wearing a head covering is a non-denominational act of showing respect. In some synagogues, women may wear hats or a lace head covering.

5. Maintaining sanctity: All guests and participants are expected to respect the sanctity of the prayer service and Shabbat by:

- Setting your cell phone or beeper to vibrate or turning it off.

- Not taking pictures. Many families hire photographers or videographers and would be pleased to take your order for a photo or video memento. In traditional settings, photography is strictly forbidden on Shabbat .

- Not smoking in the sanctuary, inside the building, or even on the synagogue grounds.

- Not writing.

- Not speaking during services. While you may see others around you chatting quietly–or even loudly–be aware that some synagogues consider this a breach of decorum.

6. Sitting and standing : Jewish worship services can be very athletic, filled with frequent directions to stand for particular prayers and sit for others. Take your cue from the other worshippers or the rabbi’s instructions. Unlike kneeling in a Catholic worship service–which is a unique prayer posture filled with religious significance–standing and sitting in a Jewish service does not constitute any affirmation of religious belief, it is merely a sign of respect. There may also be instructions to bow at certain parts of the service, and because a bow or prostration is a religiously significant act, feel free to remain standing or sitting as you wish at that point.

7. Following along in the prayerbook: Try to follow the service in the siddur , or prayerbook, and the chumash , or Bible, both of which are usually printed in Hebrew and English. Guests and congregants are encouraged to hum along during congregational melodies and to participate in the service to the extent that they feel comfortable. If you lose the page, you may quietly ask a neighbor for help (although it is better not to interrupt someone in the middle of a prayer). During the Torah service , the entire congregation is encouraged to follow the reading of the weekly Torah portion in English or Hebrew.

Who Participates in the Service

“Rabbi” means teacher. The major function of a rabbi is to instruct and guide in the study and practice of Judaism. A rabbi’s authority is based solely on learning.

A cantor has undergone years of study and training in liturgy and sacred music. The cantor leads the congregation in Hebrew prayer.

The “Emissary of the Congregation” (Shaliach Tzibbur)

The shaliach tzibbur is the leader of congregational prayers, be it the cantor or another congregant. Every Jewish prayer service, whether on a weekday, Shabbat, or festival, is chanted in a special musical mode and pattern. The shaliach tzibbur must be skilled in these traditional musical modes and familiar with the prayers. Any member of the congregation above the age of bar/bat mitzvah who is familiar with the prayers and melodies may serve as shaliach tzibbur.

The gabbai , or sexton, attends to the details of organizing the worship service. The gabbai finds a shaliach tzibbur, assigns aliyot, and ensures that the Torah is read correctly.

The Lay Leaders

Members of the congregation may participate in all synagogue functions and leadership roles. Any knowledgeable Jew is permitted and encouraged to lead the prayers, be called up to say a blessing over the Torah (called “ receiving an aliyah “), read from the Torah, and chant the Haftarah .

Bar/Bat Mitzvah and Family

If a bar or bat mitzvah is taking place at services, the bar/bat mitzvah child will participate in a variety of ways, depending on the congregation’s customs. The bar/bat mitzvah may do some or all of the following: lead services, read (often chanting) from the Torah and/or Haftarah, deliver a dvar Torah — a speech about the Torah portion read that day. Family members are usually honored by being called up to say a blessing over (or read from) the Torah, and the bar/bat mitzvah child’s parents often deliver a speech.

Sign up for My Jewish Learning’s RECHARGE , a weekly email with a collection of Shabbat readings and more to enhance your day of rest experience.

Pronounced: a-LEE-yuh for synagogue use, ah-lee-YAH for immigration to Israel, Origin: Hebrew, literally, “to go up.” This can mean the honor of saying a blessing before and after the Torah reading during a worship service, or immigrating to Israel.

bat mitzvah

Pronounced: baht MITZ-vuh, also bahs MITZ-vuh and baht meetz-VAH, Origin: Hebrew, Jewish rite of passage for a girl, observed at age 12 or 13.

Pronounced: GAH-bye, Origin: Aramaic, literally “tax collector,” but today means someone who assists with the Torah reading in synagogue.The gabbai usually determines who will be called up to the Torah for an aliyah and also assists with other aspects of coordinating worship.

Pronounced: KEE-pah or kee-PAH, Origin: Hebrew, a small hat or head covering that Orthodox Jewish men wear every day, and that other Jews wear when studying, praying or entering a sacred space. Also known as a yarmulke.

Pronounced: MITZ-vuh or meetz-VAH, Origin: Hebrew, commandment, also used to mean good deed.

Pronounced: shuh-BAHT or shah-BAHT, Origin: Hebrew, the Sabbath, from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday.

Pronounced: shuh-LEE-yakh, Origin: Hebrew, emissary — often used to describe Chabad-Lubavitch emissaries in a community or officials sent by the Israeli government to promote aliyah and Israel programming in a Diaspora community.

Pronounced: tah-LEET or TAH-liss, Origin: Hebrew, prayer shawl.

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.

Join Our Newsletter

Empower your Jewish discovery, daily

Discover More

Shacharit: The Jewish Morning Prayer Service

An outline of the prayers recited by Jews all over the world every morning.

Can Non-Jews Receive Synagogue Honors?

Being called to the Torah for an aliyah and leading certain prayers are, among other synagogue rituals, generally reserved for Jews.

Modern Israel

Modern Israel at a Glance

An overview of the Jewish state and its many accomplishments and challenges.

- Navigate to any page of this site.

- In the menu, scroll to Add to Home Screen and tap it.

- In the menu, scroll past any icons and tap Add to Home Screen .

The Temple in Antiquity

Ancient records and modern perspectives, truman g. madsen , editor, the temple and the synagogue, shaye j. d. cohen.

Shaye J. D. Cohen, “The Temple and the Synagogue,” in The Temple in Antiquity: Ancient Records and Modern Perspectives , ed. Truman G. Madsen (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1984), 151–74.

It is sometimes taught that the synagogue in Jewish architecture and ritual is a surrogate temple. In this paper Shaye Cohen draws important contrasts between the two structures, and between the two Jerusalem temples. He also shows that the synagogue has provided a democratization of the priestly functions formerly reserved for the temple. In this spirit, one interpretation congenial to the Restoration movement would be that the eventual messianic temple, while making available again the full spectrum of the priestly functions (including sacrifices by the “Sons of Levi”), will also open up to every worthy person, male or female, the privileges, rights (and rites), and ceremonial enactments which in ancient days were performed, in effect, by proxy only, by the one high priest on Yom Kippur; and that eventually the same privileges will be made available to the whole human family, and on the same principle: by proxy.

My topic was suggested to me unknowingly by Truman Madsen, who in the letter of invitation sent along copies of two articles by Professor Nibley. They are “Christian Envy of the Temple” [1] and “What Is a Temple?” [2] It was while reading those two articles that I began to ponder the relationship of the synagogue to the temple. Although I do not fully accept Professor Nibley’s conclusions, his work stimulated me to prepare my article.

One of the developments which characterize post-biblical Judaism and distinguish it from the religion of biblical Israel is the growth of the synagogue. Biblical Israel had a temple, a priestly caste, and a sacrificial cult like those of its Near Eastern neighbors. Post-biblical Judaism maintained these institutions while it invented and perfected a different institution. The synagogue, unlike the temple, is a Jewish invention, a contribution of inestimable importance to the subsequent history of Jewish, Christian, and Islamic people.

However, the origin of the synagogue is unknown and, unless we are graced by some new discoveries equal in magnitude to the Dead Sea Scrolls, unknowable. The widely accepted theory that the synagogue originated during the Babylonian exile as a replacement for the Jerusalem temple which had been destroyed in 587 B.C.E. is, I admit, plausible and attractive, but it is also unsubstantiated and overly simplistic. It is unsubstantiated because it is supported by nothing whatsoever, not a bit of evidence. The only thing supporting it is its inherent plausibility, but plausibility alone is inadequate support. The theory is also simplistic because it assigns to a single time and place the origin of a most complex institution. Our earliest bona fide reference to a synagogue is from upper Egypt in the third century B.C.E., where it is called a proseuchē in Greek. Proseuchē means prayer. Presumably “prayer (house)” should be understood. Our earliest Judean synagogue is the Jerusalem synagogue of Theodotus, which was erected “for the reading of the law and the teaching of the commandments” (first century B.C.E.). Reading of the law, teaching of the commandments-no reference at all to prayer. We know, too, that synagogues often served as assembly halls or community centers, much as the temple itself occasionally did. Hence the synagogue is an amalgamation of three separate institutions: a prayer house, a study hall or school, and a community center. The time and place in which this amalgamation was effected are as unknown to us as are the origins of each of the three separate institutions which this amalgamation was effected are as unknown to us as are the origins of each of the three separate institutions which comprise the whole. [3] Even after the destruction of the second temple in the year 70 C.E., the amalgamation was not always complete. The Rabbis regularly distinguish synagogues, batē kenēsiyot , from schools, batē midrashōt , although they occasionally study in the former and pray in the latter. Hence, as I said, the origin of the synagogue is really unknown and unknowable.

However, my interest here is not the history of institutions but the history of ideology. I shall attempt here to answer two sets of questions. First: How did the Jews of antiquity see the synagogue? How did they assess its relationship with the Jerusalem temple? What kind of sanctity did they ascribe to it? In sum, was the synagogue considered a second-best institution, a poor replacement of, or addition to, the temple, totally dependent upon it and its cult for its sanctity and legitimacy? Or, was it regarded as something independent, as an autonomous institution endowed with its own importance and worth?

The second set of questions I hope to discuss: Did synagogue practice, that is, prayer and Torah study, affect Jewish attitudes toward the temple? Did the temple lose any of its centrality or importance as a result of “competition” with the synagogue?

Having posed these two sets of questions, I confess immediately that I cannot answer them, or at least I cannot answer them satisfactorily. Why? To do so would necessitate a study not only of the contrast between the temple and the synagogue, but also of the contrasts between prayer and sacrifice and between Torah study and sacrifice. We would have to look at literary texts as well as archaeological data, especially inscriptions and synagogue art. We would have to distinguish pre-70 C.E. evidence, that is, evidence from the time of the second temple, from post-70 C.E. evidence. We would have to distinguish Babylonian from Palestinian from “Hellenistic.” We would have to distinguish Tanaitic from Amoraic, Rabbinic from non-Rabbinic, and so forth. The ideology of the synagogue has not yet been studied on this basis, and I am not about to attempt such a study here. What I would like to do is to propose answers to these two sets of questions, all the while admitting that everything I am going to say is susceptible to amplification and, I’m sorry to report, correction.

A synagogue differs from the temple in three crucial areas: place, cult, and personnel. Let us look at each of these separately. We will first consider the differences in place. According to Deuteronomy, profane slaughter was permitted anywhere in the land of Israel, while sacred slaughter could be performed only at one unnamed place, which the Lord had chosen and in which He had placed His name. [4] For Deuteronomic thinkers this site was the sacred center not only for sacrifices but for prayer as well, since God would surely hearken to the prayers of both Israelites and Gentiles when offered toward or at that place. For example, in 1 Kings 8, after building an ornate slaughterhouse, King Solomon offers a long invocatory prayer which speaks only about prayer toward or at the temple and says nothing about the sacrificial cult. During the second temple period, all Jews regarded Jerusalem as this holy center, as the mother city of the Jewish people, and regarded the temple as the center of the center, as the navel of the earth, and as God’s throne, the very symbol of the entire cosmos. [5] Later, although the Deuteronomic restrictions did not apply outside the land of Israel, the Diaspora Jews apparently refrained from building temples, according instead a sole respect to the temple in Jerusalem. In contrast to all this, of course, is the synagogue, which was not hampered by Deuteronomic theology. Synagogues were built throughout the Greco-Roman world in both Palestine and the Diaspora, both before the destruction of the temple and after it. Synagogues were not built in holy places. They were built anywhere and everywhere: even a private home could be converted into a synagogue. Surely these humble structures were not cosmic centers in any sense of the term.

The second distinction is that of cult. The cult of the temple was sacrifice. What does that mean? The slaughter, roasting, and eating of animals. It was a very bloody affair; as the Rabbis state, “It is a glory for the sons of Aaron that they walk in blood up to their ankles.” [6] Prayer had no official place in this cult. Neither Leviticus nor Numbers nor Deuteronomy nor Ezekiel nor the Temple Scroll nor Philo nor Josephus nor anyone else, as far as I can determine, mentions prayer as an integral and statutory part of the sacrificial cult. The cult is silent, except for the squeals of the animals. Of course, in times of need people prayed, and where else would they pray if not at the central shrine? But these prayers were private petitions, not parts of the sacrificial cult. Similarly the hymns of praise to God sung by the Levites always remained in the background. [7] In contrast, the synagogue cult is bloodless (those who attend modern synagogues might say it’s lifeless, but I won’t discuss that), consisting of Torah study and prayer.

We now turn to personnel, my third distinction. The sacrificial cult was carried out on behalf of the Jews by the priests. The actual administrations, that is, the slaughter, the roasting, and much of the eating, were performed only by the priests. Lay Israelites were not allowed even to enter the sacred precincts, let alone to minister before the Lord. The welfare of Israel thus depended upon the piety and punctiliousness of the priesthood, a hereditary aristocracy. The synagogue, in contrast, was a lay institution par excellence . Torah study and prayer were virtues to be cultivated by every Israelite (i.e., every male Israelite). No clergy mediated between the people and their God. “Teachers” and “heads of synagogues” were titles and professions open to all (including women).

Let us now conceptualize these three differences between the temple and the synagogue. If we focus on the first difference, place, we would conclude that the crucial tension between the temple and the synagogue is the tension between the one and the many, between monism and pluralism, one sacred place versus any place. If we focus on the second and third differences, cult and personnel, we would conclude that the crucial tension between the temple and the synagogue is the tension between aristocracy and democracy, between elitism and populism. Is it a cult by the people or for the people? Do the people perform the cult, or is it performed for them? Is there mediation by a pedigreed elite or not? These tensions, that is, monism versus pluralism and democracy versus aristocracy, are closely related but are not identical. The struggle between the central shrine and the local altars (outlined by the book of Kings), those bamot which are always said not to have disappeared from the land, was a struggle between monism and pluralism, not between elitism and populism. Even bamot had priests. The prophetic tirades against the sacrificial cult and on behalf of personal morality and piety can be interpreted as attempts to democratize Israelite religion, although the prophets were certainly not in favor of local shrines. It was possible, too, for one to believe in the uniqueness of the sacred center, the sole place where heaven and earth meet, while also supporting an unmediated cult of mass participation. There is no inherent contradiction. Deuteronomy, the book which enjoins the centralization of the cult, is also the book which enjoins upon every Israelite the constant study of the words of God. This Deuteronomic ideal was to be one of the powerful forces which democratized Israelite religion and helped it to become post-biblical Judaism. The author of Deuteronomy, not appreciating the full impact of his injunction, still supported a sacrificial cult. Hence in Deuteronomy we have centralization of the cult (monism) combined with individual study (incipient democratization). The book of Lamentations bemoans the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple in 587 B.C.E. The author is distraught over the loss of the symbol of God’s divine protection and love for Israel. He is not, however, perturbed by the loss of the sacrificial cult. Not once does he ask how he will atone for his sins without the blood of rams. Not once does he cry out that he cannot find favor in God’s eyes because the altar is no longer. Here is a man for whom the sacred center was essential, while the sacrificial cult apparently was not. I shall argue shortly that ambivalence of this sort characterizes large segments of both second temple and Rabbinic Jewry.

During the second temple period it was easy to entertain ambivalent ideas on the centrality of the temple and its cult. The beginnings of the second temple were most inauspicious. Jeremiah had predicted that the return from Babylon to Israel would be more magnificent than the exodus from Egypt; the new redemption would completely eclipse the old one. [8] But this did not come to pass. Instead, a pagan king issued an edict allowing the Jews to return to their homeland and to rebuild their temple. No Davidic king, no miracles, no glory, no political freedom, just an edict issued by the Persian bureaucracy in the name of Cyrus the Great. Was this the return promised by the Lord? Many Jews objected. An anonymous prophet whom we call II Isaiah (whom some people call I Isaiah) scolded them.

Shame on him who argues with his maker. Though naught but a potsherd of earth. Shall the clay say to the potter, “what are you begetting?” or a woman, “what are you bearing?” Thus said the Lord, Israel’s holy one and maker. Will you question me on the destiny of my children? Will you instruct me about the work of my hands? It was I who made the earth and created man upon it. My own hands stretched out of the heavens and I marshalled all their host. It was I who roused him (Cyrus the Great) for victory, and who level all roads for him. He shall rebuild my city and let my exiled people go. [9]

God, the creator of the world, is the boss. He does with his creation as he sees fit. Once upon a time, as Jeremiah said, he appointed his servant or vassal ( ebed ) Nebuchadnezzar to destroy the temple. [10] Now, Isaiah says, God has appointed Cyrus an anointed one, [11] a step above a vassal, to rebuild the temple. Can the Jews argue with their maker? Of course not. Let the Jews accept the divine decree. Similarly, the author of the book of Ezra insists that Cyrus’ kindness to the Jews was motivated not by any selfish or personal desires, but by inspiration from God, thereby fulfilling Jeremiah’s prophecy of redemption. [12]

But these attempts convinced few. Since fire did not descend from heaven upon the newly reconstructed altar, how could the Jews be sure the new temple and its cult found favor before the Lord? [13] The old men who had seen the majesty and the glory of the first temple shed tears at the dedication of the second-not tears of joy, but tears of sadness. [14]

Matters soon became worse. Prophecy ceased. The Urim and Thummim fell into disuse. Later, corruption spread among the priesthood. A pagan king entered the holy precincts, plundered the treasury, and sacrificed swine on the altar and established idols in the temple, all the while persecuting the Jews and proscribing Judaism. Never before had such atrocities occurred. Was this God’s holy temple? Ultimately the temple was regained and the altar was rebuilt, but still no fire from heaven, no miracles, no explicit sign that God approved the doings of men, and no Davidic king. Even the high priests were no longer legitimate high priests; they were regular priests who usurped the leadership (the Maccabees). Less than a century before its destruction, the temple suffered the ignominy of being rebuilt by Herod the Great, a half-Jew and a complete madman, who incorporated pagan decorations in the structure.

The Rabbis summed this up very nicely when they said, “The second temple had five things less than the first temple.” That is, the first temple had five things more than the second temple. What were they? “The sacred fire, the ark, the urim and thummim, the oil for anointment, and the Holy Spirit (prophecy).” [15]

Yet, in spite of all this, many Jews of the second temple period were content with the cult and the priesthood. After all, the temple was still the temple. The priests were the priests. Nor was this attitude restricted to the temple clergy itself. For how else can we explain the multitudes of the faithful who journeyed to Jerusalem every year at each of the three pilgrim festivals? How else can we explain the prominence accorded to the sacrificial cult by such diverse writers as Philo, Josephus (who, I admit, was a priest), and the authors of the Sibylline Oracles ? [16] These Jews supplemented the sacrificial cult with other modes of piety. But these other modes were supplements, not replacements. Josephus, for example, boasts that all Jews are learned in the law and declares that Jews regularly pray to God to acknowledge all the bounteous gifts of the divine. [17] But at no point does he even hint that either Torah study or prayer are replacements for, or subservient to, the sacrificial cult. They exist alongside each other. Philo, too, has the same attitude. [18]

For many Jews, however, the temple was too blemished for such unquestioning allegiance. A few radical Jews, inspired either by one strand of biblical thought (viz., that God cannot be contained by the heavens, let alone by a temple) or by Greek philosophy (Zeno believed that no temple could ever be sacred since no man-made building could be worthy of the gods), or by a combination of the two, argued that God does not require a temple at all-that the entire cosmos is God’s throne. [19] A more common attitude was condemnation of the current temple and cult combined with a hope, which I assume was shared even by those who supported the cult, for the restoration of a new and perfect temple in the future. The condemnation and the hope were expressed in different ways and had different implications among the various Jewish groups. For some the second temple was impure from its very inception; even the sacrifices of Zerubbabel and Joshua the High Priest were profane. [20] For others, the profanation of the temple was of more recent vintage, since the time of the Maccabees and Antiochus Epiphanes. Some, like the Essenes, concluded that the temple was much too impure for their participation in its cult, while others, like some of the early Christians, felt that the impurity was not as great as that. (According to Acts many Christians spent their day sitting in the temple; and Paul, after returning from Asia Minor, showed his loyalty to the law by sacrificing at the temple.) For the future, some groups could imagine nothing more glorious than a new temple, a new priesthood, and the proper observance of the sacrifices and the festivals. Such was the intention of the Temple Scroll, which gives elaborate instructions for the performance of the festival sacrifices. I assume, as Professor Milgrom does, that this scroll is a blueprint for the ideal future, and the ideal future is a world based on the temple cult. Most visionaries, however, spoke more generally about a new temple which would descend from heaven in a future era; they did not specify or stress the nature of the cult in that temple. Some spoke of a New Jerusalem rather than a new temple, [21] and one wonders whether the New Jerusalem necessarily had at its center a temple with a sacrificial cult. At least one visionary proclaimed explicitly, “And I did not see a temple in her (the heavenly Jerusalem descending from heaven to earth) for the Lord God, the ruler of all is her temple.” [22]

In the meantime, before the descent of the heavenly Jerusalem and/ or the heavenly temple, what was one to do? Given the fact that the temple and the sacrificial cult were presently imperfect, how could one find favor with God? Various attempts were made to find substitutes for the sacrificial cult. Some said that contrition and humility were worthy substitutes. “We have at this time no prince, prophet, leader, burnt offering, sacrifice, oblations, incense, no place to make an offering before thee or to find mercy. Yet, with a contrite heart and humble spirit may we be accepted as though it were with burnt offerings of rams and bulls and tens of thousands of fat lambs.” [23] These words are placed in the mouth of someone who supposedly lived after the destruction of the first temple and before the construction of the second, but presumably this text reflects an ideology current in the author’s own day (second century B.C.E.?), when the second temple was standing quite soundly on its foundation. Similarly, in good prophetic fashion, other authors argued that fear of the Lord, charity, and performance of the commandments were replacements for the cult. [24] However, I know of no text from the second temple period which declares either Torah study or prayer to be the equivalent of, or the replacements for, the sacrificial cult. Psalm 119 elevates Torah study to an ideal, but does not compare it to the sacrifices. Deuteronomy enjoins the study of the law so that the Israelite would know how to fulfill the commandments. In Psalm 119 Torah study is not a means but an end. The study of the law is a mode of worship. One finds favor with God by immersing himself in the words of the Torah. Does that replace the sacrificial cult? Not a hint, not a hint. Various texts refer to the practice of coordinating prayer with the times of the sacrifices, [25] but it is unclear to me whether this indicates a conception of prayer as a surrogate for sacrifice, or rather the idea that the times ordained by God for sacrifice were also propitious for prayer. In any case, surrogates were found for the sacrificial cult: humility, contrition, charity, or fear of the Lord, if not Torah study and prayer.

And if surrogates could be found for the cult, could they not be found for the temple as well? It is likely that both sects and synagogues, whose interrelationship remains unexplored, were regarded by their adherents as replacements for the polluted and imperfect temple. Many sects, notably Christians, Essenes, and Pharisees, transferred to themselves-each sect in its own distinctive way-at least some of the laws and ideology of the temple. The corporate brotherhood, the encampment of the sectarians or the table of the group, became the new temple and the new altar. Were synagogues, too, regarded as replacements for the temple? An affirmative answer is almost inevitable, although no text of the second temple period equates Torah study and prayer with the temple cult, or the synagogue with the temple. In fact, few second temple sources even speak about synagogues. Both Philo and Josephus mention the synagogue, but neither attempts to give its history or its ideology. Their praise of prayer and study does not extend to the institution in which these practices took place. Few works of the so-called Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha even mention the synagogue, and not a single work of the Dead Sea Scrolls. [26] This reticence concerning the synagogue allows me to return to my theme and to put these pieces together.

During the second temple period the Israelitic religion was democratized. Professor Milgrom spoke about that not too long ago. Torah study, prayer and performance of the commandments by the individual Jew became the distinguishing characteristics of Judaism. Reward and punishment, life after death, immortality of the soul, final judgment-all these beliefs were individualized as the individual Jew became more distinct from the corporate body of Israel. Sect and synagogue ministered to this need for individual self-expression and self-fulfillment. These ideas are the wave of the present and the future. Against all this stood the temple and the sacrificial cult, both based on the idea that the few perform the religion on behalf of the many. Not only were these the waves of the past, but they were, even on their own terms, imperfect and blemished. Hence for many Jews, new ways of serving God supplemented and/ or replaced the old ways of the temple and the sacrificial cult, so much so that we cannot assume that all eschatological visions included a place for the sacrificial cult. In fact, few such visions emphasize or describe in detail the sacrificial cults of the future. (The temple scroll is a notable exception.)

However, the temple had one great advantage which neither the synagogue nor the school nor the sect nor prayer nor humility nor anything else could ever hope to duplicate. The temple was located on the one sacred place on Mount Moriah, where Abraham nearly sacrificed Isaac, where Jacob saw a ladder reaching into heaven, and where the angel of the Lord commanded David to build an altar. [27] It was the meeting place of heaven and earth, the center of the cosmos, the symbol of the cosmos, the visible presence of God’s oneness. As Josephus says in a rhyme which I assume he learned in the Sunday School of his time, “One temple for the one God.” [28] Any institution which upset this unity and which was not established on this sacred center was not part of the Jewish ideal. Hence synagogues and sects, by their very nature, are impermanent and imperfect institutions which have no share in the world to come. According to many texts of the second temple period, God has in the heavens a temple and/ or a Jerusalem prepared for the delectation of his faithful, but he does not have a heavenly synagogue or a heavenly sect. Synagogues and sects represent the breakdown of unity and the departure from unanimity, yet monism and unanimity are the proofs of Judaism’s truth. [29] Hence in the ideology of second temple Judaism, the sacrificial cult could be supplemented or replaced by democratic alternatives, but the temple could never be replaced. As a result, no one cared to talk much about sects or synagogues.

The Rabbis inherited these ideas as part of their legacy from second temple Judaism, and they, too, maintained an ambivalent and complex attitude toward the sacrificial cult and the temple, both of which were destroyed in 70 C.E. The entire Rabbinic enterprise is predicated on the democratic assumptions mentioned earlier which are diametrically opposed to those of the sacrificial cult. Rabbinic Jews find God through prayer, Torah study, mystical speculation, and the continuous performance of the commandments, notably the commandments of Shabbat and festivals, purity, tithing, food laws, and ethical behavior. All of these are personal and unmediated, and all of them (except mystical speculation) were incumbent upon every male Jew. The relationship of this Rabbinic piety to the sacrificial cult, which most Rabbis believed would be restored in the Messianic era, was never worked out systematically. [30] After all, the Rabbis never worked out anything systematically. Nonetheless, they always held that Torah study was at least equal, if not superior, to the sacrificial cult. Prayer, however, is in a different category, and here we find three attitudes:

- Prayer is a religious obligation which exists independently of the sacrificial cult. The presence or absence of the cult does not affect it.

- Prayer is a second-rate replacement for the sacrificial cult. Without the cult, Israel has difficulty finding atonement for its sins. Hence it yearns for the restoration of the cult, which will bring it normalcy and security.

- Prayer is a first-rate replacement for the sacrificial cult, perhaps even better than the original. The logical outgrowth of this position is the idea that the temple of the age to come does not necessarily have to have a sacrificial cult.

We see in these three attitudes echoes of the views held by the Jews of the second temple period. The sole Rabbinic innovation, as far as I can see, was the elevation of Torah study and prayer to that prophetic list of equivalents or replacements for the sacrificial cult. Just like their ancestors, the Rabbis did not endow the synagogue with an independent existence. They, too, regarded it as a poor surrogate for the temple and accorded it no role in the world to come. For the Rabbis, prayer versus sacrifice and Torah study versus sacrifice were real issues. Synagogue versus temple was not.

Having presented a summary of the Rabbinic position, I would like now to elaborate upon it briefly. It is often said that Judaism’s will and spirit were devastated by the destruction of the temple, particularly by the cessation of the sacrificial cult. This view is usually supported by the following two Rabbinic stories.

Once as Rabban Johanan ben Zokkai was coming forth from Jerusalem, Rabbi Joshua followed after him and beheld the temple in ruins. “Wo unto us,” Rabbi Joshua cried, “that this, the place where the iniquities of Israel were atoned, is laid waste!” “My son,” Rabban Johanan said to him, “be not grieved; we have another atonement as effective as this.” “And what is it?” “It is acts of loving kindness. As it is said, ‘for I desire mercy and not sacrifice.’” [31]

After the destruction of the temple, perushim (ascetics or separatists) who would neither eat meat nor drink wine became numerous in Israel. Rabbi Joshua met them and inquired, “My sons, why don’t you eat meat?” They replied, “Shall we eat meat when the continual sacrifice, which used to be offered every day on the altar, is no longer?” He then asked, “Why don’t you drink wine?” They responded, “Shall we drink wine, which used to be poured on the altar as a libation, and is no longer?” He said to them, “Even figs and grapes we should not eat because from them they used to bring the first fruits on the Azereth [Pentecost]; bread we should not eat, because they used to bring two loaves and the bread of the presence, water we should not drink because they used to pour libations at Sukkoth [Tabernacles].” The perushim were silent. Rabbi Joshua said to them, “Not to mourn at all [for the destruction of the temple] is impossible. To mourn excessively is impossible. But thus the sages have said, ‘A man plasters his house, but leaves a little bit unplastered as a memorial for Jerusalem.’” [32] In other words, just as Jeremiah wrote to the Jews in Babylonia, normalcy must be maintained, but we must never forget what happened.

The historicity of these stories I do not wish to judge here. But even if they are historical as written, they do not indicate a widespread belief among the Jews of the time that they were at a loss how to proceed after the sacrificial cult had been removed. The second story is said explicitly to concern only the perushim , a small group separate from the main religious body of Israel. Furthermore, their asceticism was prompted, not by their inability to obtain atonement, but by their feeling that it was not right for man to sup upon meat and wine while the Lord’s table, the altar, was destroyed. The first story is more germane to our discussion, but more striking than the anguished cry of Rabbi Joshua (the same Rabbi Joshua who knew very well how to handle the separatists) is Rabban Johanan’s hackneyed response. The Master merely paraphrases Hosea: deeds of loving-kindness replace the sacrifices. Indeed, if Rabbi Joshua was satisfied with this reply, the wonder is that he didn’t think of it on his own. Rabban Johanan’s statement is just another in the long chain of statements, beginning with the prophets and the book of Psalms, which declare some virtue or other to be equal or superior to the sacrifices. Rabban Johanan leaves out the truly revolutionary Rabbinic response to the catastrophe of 70 C.E.-the elevation of Torah study and prayer. Hence this isolated exchange is not real evidence for a deep-seated religious crisis among Rabbinic Jews after the destruction of the second temple.

Indeed, like the author of Lamentations, the Rabbis of the Tannaitic period [33] and the authors of the Syriac Apocalypse of Baruch and IV Ezra were distressed more by the loss of Jerusalem and the loss of the temple, the visible signs of God’s presence in Israel, than by the loss of the sacrificial cult.

Presumably, the sacrificial cult had been supplemented or replaced for so long that its loss was not as devastating as it might have been. The Rabbis of the Tannaitic period, of course, hoped and expected that the sacrificial cult would be restored-indeed, one-sixth of the Mishnah is devoted to the laws of the sacrificial cult-but they did not sense a need to find an immediate replacement for the cult. Life could go on without sacrifices. It is even questionable whether the petition for the restoration of the sacrifices figures as prominently in the prayers of the Tannaim as it does in the liturgy of the following generation. [34] As I have already indicated, the real Rabbinic response to 70 C.E. is not the hackneyed declaration of Rabban Johanan but the affirmation that prayer and Torah study have as great a worth as the sacrifices of old, not as their replacement but as their equivalent or supplement . The classic statement of this view is in the Tannaitic commentary to Deuteronomy 11:13. “ To love the Lord your God and to serve Him . This is Torah study. . . . Just as the sacrificial cult is called ‘service’ ( Abodah ), so too is Torah study called ‘service’ ( Abodah ). Another opinion: ‘to serve Him’ is prayer. . . . Just as the sacrificial cult is called ‘service’ ( Abodah ), so too prayer is called ‘service’ ( Abodah ).” [35] Presumably, these Rabbis believed that the Messianic future held in store a sacrificial cult, combined in some mysterious way with prayer and Torah study, since all three are means of serving the Lord.