The Sheridan Libraries

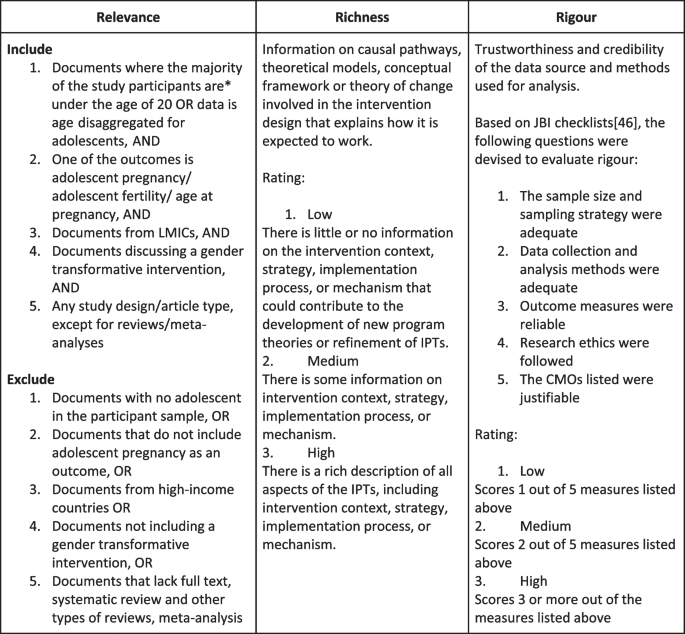

- Write a Literature Review

- Sheridan Libraries

- Find This link opens in a new window

- Evaluate This link opens in a new window

Get Organized

- Lit Review Prep Use this template to help you evaluate your sources, create article summaries for an annotated bibliography, and a synthesis matrix for your lit review outline.

Synthesize your Information

Synthesize: combine separate elements to form a whole.

Synthesis Matrix

A synthesis matrix helps you record the main points of each source and document how sources relate to each other.

After summarizing and evaluating your sources, arrange them in a matrix or use a citation manager to help you see how they relate to each other and apply to each of your themes or variables.

By arranging your sources by theme or variable, you can see how your sources relate to each other, and can start thinking about how you weave them together to create a narrative.

- Step-by-Step Approach

- Example Matrix from NSCU

- Matrix Template

- << Previous: Summarize

- Next: Integrate >>

- Last Updated: Sep 26, 2023 10:25 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.jhu.edu/lit-review

- University of Oregon Libraries

- Research Guides

How to Write a Literature Review

- 6. Synthesize

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Reading Journal Articles

- Does it Describe a Literature Review?

- 1. Identify the Question

- 2. Review Discipline Styles

- Searching Article Databases

- Finding Full-Text of an Article

- Citation Chaining

- When to Stop Searching

- 4. Manage Your References

- 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

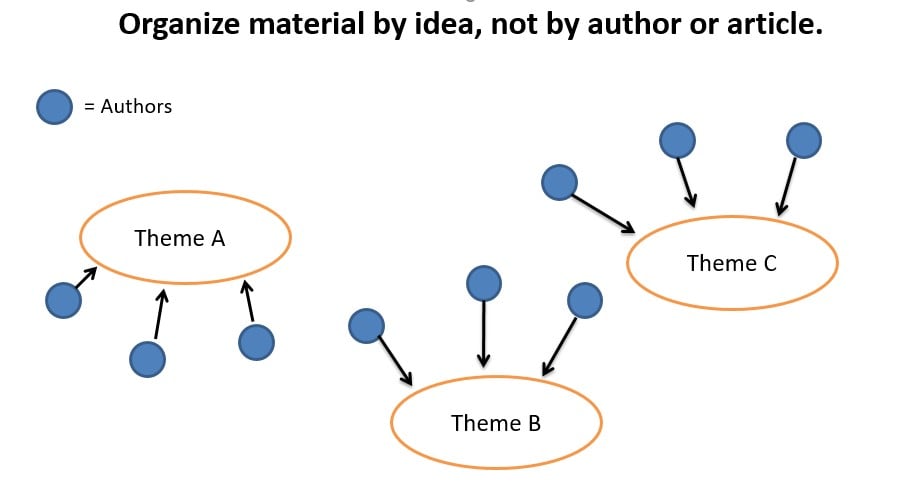

Synthesis Visualization

Synthesis matrix example.

- 7. Write a Literature Review

- Synthesis Worksheet

About Synthesis

Approaches to synthesis.

You can sort the literature in various ways, for example:

How to Begin?

Read your sources carefully and find the main idea(s) of each source

Look for similarities in your sources – which sources are talking about the same main ideas? (for example, sources that discuss the historical background on your topic)

Use the worksheet (above) or synthesis matrix (below) to get organized

This work can be messy. Don't worry if you have to go through a few iterations of the worksheet or matrix as you work on your lit review!

Four Examples of Student Writing

In the four examples below, only ONE shows a good example of synthesis: the fourth column, or Student D . For a web accessible version, click the link below the image.

Long description of "Four Examples of Student Writing" for web accessibility

- Download a copy of the "Four Examples of Student Writing" chart

Click on the example to view the pdf.

From Jennifer Lim

- << Previous: 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

- Next: 7. Write a Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Jan 10, 2024 4:46 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.uoregon.edu/litreview

Contact Us Library Accessibility UO Libraries Privacy Notices and Procedures

1501 Kincaid Street Eugene, OR 97403 P: 541-346-3053 F: 541-346-3485

- Visit us on Facebook

- Visit us on Twitter

- Visit us on Youtube

- Visit us on Instagram

- Report a Concern

- Nondiscrimination and Title IX

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Find People

Literature Syntheis 101

How To Synthesise The Existing Research (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | August 2023

One of the most common mistakes that students make when writing a literature review is that they err on the side of describing the existing literature rather than providing a critical synthesis of it. In this post, we’ll unpack what exactly synthesis means and show you how to craft a strong literature synthesis using practical examples.

This post is based on our popular online course, Literature Review Bootcamp . In the course, we walk you through the full process of developing a literature review, step by step. If it’s your first time writing a literature review, you definitely want to use this link to get 50% off the course (limited-time offer).

Overview: Literature Synthesis

- What exactly does “synthesis” mean?

- Aspect 1: Agreement

- Aspect 2: Disagreement

- Aspect 3: Key theories

- Aspect 4: Contexts

- Aspect 5: Methodologies

- Bringing it all together

What does “synthesis” actually mean?

As a starting point, let’s quickly define what exactly we mean when we use the term “synthesis” within the context of a literature review.

Simply put, literature synthesis means going beyond just describing what everyone has said and found. Instead, synthesis is about bringing together all the information from various sources to present a cohesive assessment of the current state of knowledge in relation to your study’s research aims and questions .

Put another way, a good synthesis tells the reader exactly where the current research is “at” in terms of the topic you’re interested in – specifically, what’s known , what’s not , and where there’s a need for more research .

So, how do you go about doing this?

Well, there’s no “one right way” when it comes to literature synthesis, but we’ve found that it’s particularly useful to ask yourself five key questions when you’re working on your literature review. Having done so, you can then address them more articulately within your actual write up. So, let’s take a look at each of these questions.

1. Points Of Agreement

The first question that you need to ask yourself is: “Overall, what things seem to be agreed upon by the vast majority of the literature?”

For example, if your research aim is to identify which factors contribute toward job satisfaction, you’ll need to identify which factors are broadly agreed upon and “settled” within the literature. Naturally, there may at times be some lone contrarian that has a radical viewpoint , but, provided that the vast majority of researchers are in agreement, you can put these random outliers to the side. That is, of course, unless your research aims to explore a contrarian viewpoint and there’s a clear justification for doing so.

Identifying what’s broadly agreed upon is an essential starting point for synthesising the literature, because you generally don’t want (or need) to reinvent the wheel or run down a road investigating something that is already well established . So, addressing this question first lays a foundation of “settled” knowledge.

Need a helping hand?

2. Points Of Disagreement

Related to the previous point, but on the other end of the spectrum, is the equally important question: “Where do the disagreements lie?” .

In other words, which things are not well agreed upon by current researchers? It’s important to clarify here that by disagreement, we don’t mean that researchers are (necessarily) fighting over it – just that there are relatively mixed findings within the empirical research , with no firm consensus amongst researchers.

This is a really important question to address as these “disagreements” will often set the stage for the research gap(s). In other words, they provide clues regarding potential opportunities for further research, which your study can then (hopefully) contribute toward filling. If you’re not familiar with the concept of a research gap, be sure to check out our explainer video covering exactly that .

3. Key Theories

The next question you need to ask yourself is: “Which key theories seem to be coming up repeatedly?” .

Within most research spaces, you’ll find that you keep running into a handful of key theories that are referred to over and over again. Apart from identifying these theories, you’ll also need to think about how they’re connected to each other. Specifically, you need to ask yourself:

- Are they all covering the same ground or do they have different focal points or underlying assumptions ?

- Do some of them feed into each other and if so, is there an opportunity to integrate them into a more cohesive theory?

- Do some of them pull in different directions ? If so, why might this be?

- Do all of the theories define the key concepts and variables in the same way, or is there some disconnect? If so, what’s the impact of this ?

Simply put, you’ll need to pay careful attention to the key theories in your research area, as they will need to feature within your theoretical framework , which will form a critical component within your final literature review. This will set the foundation for your entire study, so it’s essential that you be critical in this area of your literature synthesis.

If this sounds a bit fluffy, don’t worry. We deep dive into the theoretical framework (as well as the conceptual framework) and look at practical examples in Literature Review Bootcamp . If you’d like to learn more, take advantage of our limited-time offer to get 60% off the standard price.

4. Contexts

The next question that you need to address in your literature synthesis is an important one, and that is: “Which contexts have (and have not) been covered by the existing research?” .

For example, sticking with our earlier hypothetical topic (factors that impact job satisfaction), you may find that most of the research has focused on white-collar , management-level staff within a primarily Western context, but little has been done on blue-collar workers in an Eastern context. Given the significant socio-cultural differences between these two groups, this is an important observation, as it could present a contextual research gap .

In practical terms, this means that you’ll need to carefully assess the context of each piece of literature that you’re engaging with, especially the empirical research (i.e., studies that have collected and analysed real-world data). Ideally, you should keep notes regarding the context of each study in some sort of catalogue or sheet, so that you can easily make sense of this before you start the writing phase. If you’d like, our free literature catalogue worksheet is a great tool for this task.

5. Methodological Approaches

Last but certainly not least, you need to ask yourself the question: “What types of research methodologies have (and haven’t) been used?”

For example, you might find that most studies have approached the topic using qualitative methods such as interviews and thematic analysis. Alternatively, you might find that most studies have used quantitative methods such as online surveys and statistical analysis.

But why does this matter?

Well, it can run in one of two potential directions . If you find that the vast majority of studies use a specific methodological approach, this could provide you with a firm foundation on which to base your own study’s methodology . In other words, you can use the methodologies of similar studies to inform (and justify) your own study’s research design .

On the other hand, you might argue that the lack of diverse methodological approaches presents a research gap , and therefore your study could contribute toward filling that gap by taking a different approach. For example, taking a qualitative approach to a research area that is typically approached quantitatively. Of course, if you’re going to go against the methodological grain, you’ll need to provide a strong justification for why your proposed approach makes sense. Nevertheless, it is something worth at least considering.

Regardless of which route you opt for, you need to pay careful attention to the methodologies used in the relevant studies and provide at least some discussion about this in your write-up. Again, it’s useful to keep track of this on some sort of spreadsheet or catalogue as you digest each article, so consider grabbing a copy of our free literature catalogue if you don’t have anything in place.

Bringing It All Together

Alright, so we’ve looked at five important questions that you need to ask (and answer) to help you develop a strong synthesis within your literature review. To recap, these are:

- Which things are broadly agreed upon within the current research?

- Which things are the subject of disagreement (or at least, present mixed findings)?

- Which theories seem to be central to your research topic and how do they relate or compare to each other?

- Which contexts have (and haven’t) been covered?

- Which methodological approaches are most common?

Importantly, you’re not just asking yourself these questions for the sake of asking them – they’re not just a reflection exercise. You need to weave your answers to them into your actual literature review when you write it up. How exactly you do this will vary from project to project depending on the structure you opt for, but you’ll still need to address them within your literature review, whichever route you go.

The best approach is to spend some time actually writing out your answers to these questions, as opposed to just thinking about them in your head. Putting your thoughts onto paper really helps you flesh out your thinking . As you do this, don’t just write down the answers – instead, think about what they mean in terms of the research gap you’ll present , as well as the methodological approach you’ll take . Your literature synthesis needs to lay the groundwork for these two things, so it’s essential that you link all of it together in your mind, and of course, on paper.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling Udemy Course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

excellent , thank you

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

How to Synthesize Written Information from Multiple Sources

Shona McCombes

Content Manager

B.A., English Literature, University of Glasgow

Shona McCombes is the content manager at Scribbr, Netherlands.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

When you write a literature review or essay, you have to go beyond just summarizing the articles you’ve read – you need to synthesize the literature to show how it all fits together (and how your own research fits in).

Synthesizing simply means combining. Instead of summarizing the main points of each source in turn, you put together the ideas and findings of multiple sources in order to make an overall point.

At the most basic level, this involves looking for similarities and differences between your sources. Your synthesis should show the reader where the sources overlap and where they diverge.

Unsynthesized Example

Franz (2008) studied undergraduate online students. He looked at 17 females and 18 males and found that none of them liked APA. According to Franz, the evidence suggested that all students are reluctant to learn citations style. Perez (2010) also studies undergraduate students. She looked at 42 females and 50 males and found that males were significantly more inclined to use citation software ( p < .05). Findings suggest that females might graduate sooner. Goldstein (2012) looked at British undergraduates. Among a sample of 50, all females, all confident in their abilities to cite and were eager to write their dissertations.

Synthesized Example

Studies of undergraduate students reveal conflicting conclusions regarding relationships between advanced scholarly study and citation efficacy. Although Franz (2008) found that no participants enjoyed learning citation style, Goldstein (2012) determined in a larger study that all participants watched felt comfortable citing sources, suggesting that variables among participant and control group populations must be examined more closely. Although Perez (2010) expanded on Franz’s original study with a larger, more diverse sample…

Step 1: Organize your sources

After collecting the relevant literature, you’ve got a lot of information to work through, and no clear idea of how it all fits together.

Before you can start writing, you need to organize your notes in a way that allows you to see the relationships between sources.

One way to begin synthesizing the literature is to put your notes into a table. Depending on your topic and the type of literature you’re dealing with, there are a couple of different ways you can organize this.

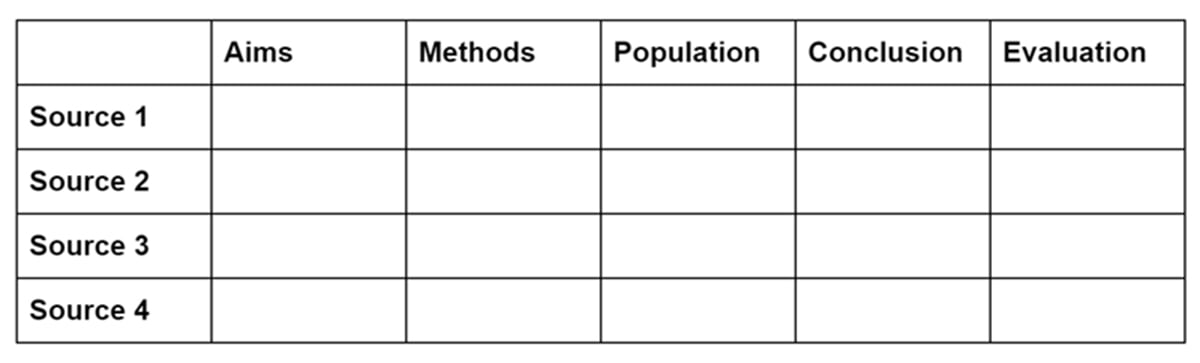

Summary table

A summary table collates the key points of each source under consistent headings. This is a good approach if your sources tend to have a similar structure – for instance, if they’re all empirical papers.

Each row in the table lists one source, and each column identifies a specific part of the source. You can decide which headings to include based on what’s most relevant to the literature you’re dealing with.

For example, you might include columns for things like aims, methods, variables, population, sample size, and conclusion.

For each study, you briefly summarize each of these aspects. You can also include columns for your own evaluation and analysis.

The summary table gives you a quick overview of the key points of each source. This allows you to group sources by relevant similarities, as well as noticing important differences or contradictions in their findings.

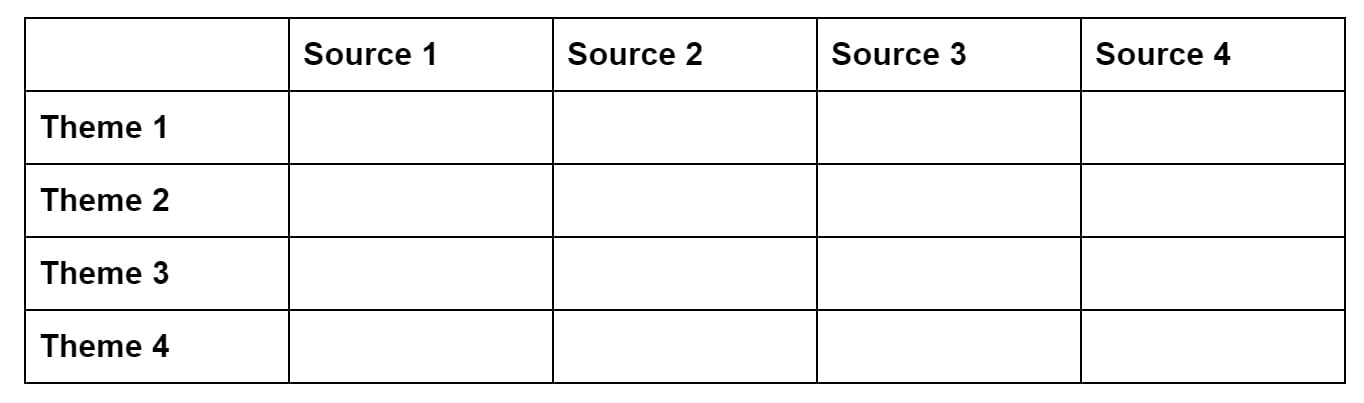

Synthesis matrix

A synthesis matrix is useful when your sources are more varied in their purpose and structure – for example, when you’re dealing with books and essays making various different arguments about a topic.

Each column in the table lists one source. Each row is labeled with a specific concept, topic or theme that recurs across all or most of the sources.

Then, for each source, you summarize the main points or arguments related to the theme.

The purposes of the table is to identify the common points that connect the sources, as well as identifying points where they diverge or disagree.

Step 2: Outline your structure

Now you should have a clear overview of the main connections and differences between the sources you’ve read. Next, you need to decide how you’ll group them together and the order in which you’ll discuss them.

For shorter papers, your outline can just identify the focus of each paragraph; for longer papers, you might want to divide it into sections with headings.

There are a few different approaches you can take to help you structure your synthesis.

If your sources cover a broad time period, and you found patterns in how researchers approached the topic over time, you can organize your discussion chronologically .

That doesn’t mean you just summarize each paper in chronological order; instead, you should group articles into time periods and identify what they have in common, as well as signalling important turning points or developments in the literature.

If the literature covers various different topics, you can organize it thematically .

That means that each paragraph or section focuses on a specific theme and explains how that theme is approached in the literature.

Source Used with Permission: The Chicago School

If you’re drawing on literature from various different fields or they use a wide variety of research methods, you can organize your sources methodologically .

That means grouping together studies based on the type of research they did and discussing the findings that emerged from each method.

If your topic involves a debate between different schools of thought, you can organize it theoretically .

That means comparing the different theories that have been developed and grouping together papers based on the position or perspective they take on the topic, as well as evaluating which arguments are most convincing.

Step 3: Write paragraphs with topic sentences

What sets a synthesis apart from a summary is that it combines various sources. The easiest way to think about this is that each paragraph should discuss a few different sources, and you should be able to condense the overall point of the paragraph into one sentence.

This is called a topic sentence , and it usually appears at the start of the paragraph. The topic sentence signals what the whole paragraph is about; every sentence in the paragraph should be clearly related to it.

A topic sentence can be a simple summary of the paragraph’s content:

“Early research on [x] focused heavily on [y].”

For an effective synthesis, you can use topic sentences to link back to the previous paragraph, highlighting a point of debate or critique:

“Several scholars have pointed out the flaws in this approach.” “While recent research has attempted to address the problem, many of these studies have methodological flaws that limit their validity.”

By using topic sentences, you can ensure that your paragraphs are coherent and clearly show the connections between the articles you are discussing.

As you write your paragraphs, avoid quoting directly from sources: use your own words to explain the commonalities and differences that you found in the literature.

Don’t try to cover every single point from every single source – the key to synthesizing is to extract the most important and relevant information and combine it to give your reader an overall picture of the state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 4: Revise, edit and proofread

Like any other piece of academic writing, synthesizing literature doesn’t happen all in one go – it involves redrafting, revising, editing and proofreading your work.

Checklist for Synthesis

- Do I introduce the paragraph with a clear, focused topic sentence?

- Do I discuss more than one source in the paragraph?

- Do I mention only the most relevant findings, rather than describing every part of the studies?

- Do I discuss the similarities or differences between the sources, rather than summarizing each source in turn?

- Do I put the findings or arguments of the sources in my own words?

- Is the paragraph organized around a single idea?

- Is the paragraph directly relevant to my research question or topic?

- Is there a logical transition from this paragraph to the next one?

Further Information

How to Synthesise: a Step-by-Step Approach

Help…I”ve Been Asked to Synthesize!

Learn how to Synthesise (combine information from sources)

How to write a Psychology Essay

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

Library Guides

Literature reviews: synthesis.

- Criticality

Synthesise Information

So, how can you create paragraphs within your literature review that demonstrates your knowledge of the scholarship that has been done in your field of study?

You will need to present a synthesis of the texts you read.

Doug Specht, Senior Lecturer at the Westminster School of Media and Communication, explains synthesis for us in the following video:

Synthesising Texts

What is synthesis?

Synthesis is an important element of academic writing, demonstrating comprehension, analysis, evaluation and original creation.

With synthesis you extract content from different sources to create an original text. While paraphrase and summary maintain the structure of the given source(s), with synthesis you create a new structure.

The sources will provide different perspectives and evidence on a topic. They will be put together when agreeing, contrasted when disagreeing. The sources must be referenced.

Perfect your synthesis by showing the flow of your reasoning, expressing critical evaluation of the sources and drawing conclusions.

When you synthesise think of "using strategic thinking to resolve a problem requiring the integration of diverse pieces of information around a structuring theme" (Mateos and Sole 2009, p448).

Synthesis is a complex activity, which requires a high degree of comprehension and active engagement with the subject. As you progress in higher education, so increase the expectations on your abilities to synthesise.

How to synthesise in a literature review:

Identify themes/issues you'd like to discuss in the literature review. Think of an outline.

Read the literature and identify these themes/issues.

Critically analyse the texts asking: how does the text I'm reading relate to the other texts I've read on the same topic? Is it in agreement? Does it differ in its perspective? Is it stronger or weaker? How does it differ (could be scope, methods, year of publication etc.). Draw your conclusions on the state of the literature on the topic.

Start writing your literature review, structuring it according to the outline you planned.

Put together sources stating the same point; contrast sources presenting counter-arguments or different points.

Present your critical analysis.

Always provide the references.

The best synthesis requires a "recursive process" whereby you read the source texts, identify relevant parts, take notes, produce drafts, re-read the source texts, revise your text, re-write... (Mateos and Sole, 2009).

What is good synthesis?

The quality of your synthesis can be assessed considering the following (Mateos and Sole, 2009, p439):

Integration and connection of the information from the source texts around a structuring theme.

Selection of ideas necessary for producing the synthesis.

Appropriateness of the interpretation.

Elaboration of the content.

Example of Synthesis

Original texts (fictitious):

Synthesis:

Animal experimentation is a subject of heated debate. Some argue that painful experiments should be banned. Indeed it has been demonstrated that such experiments make animals suffer physically and psychologically (Chowdhury 2012; Panatta and Hudson 2016). On the other hand, it has been argued that animal experimentation can save human lives and reduce harm on humans (Smith 2008). This argument is only valid for toxicological testing, not for tests that, for example, merely improve the efficacy of a cosmetic (Turner 2015). It can be suggested that animal experimentation should be regulated to only allow toxicological risk assessment, and the suffering to the animals should be minimised.

Bibliography

Mateos, M. and Sole, I. (2009). Synthesising Information from various texts: A Study of Procedures and Products at Different Educational Levels. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 24 (4), 435-451. Available from https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03178760 [Accessed 29 June 2021].

- << Previous: Structure

- Next: Criticality >>

- Last Updated: Nov 18, 2023 10:56 PM

- URL: https://libguides.westminster.ac.uk/literature-reviews

CONNECT WITH US

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved March 20, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Literature Review How To

- Things To Consider

- Synthesizing Sources

- Video Tutorials

- Books On Literature Reviews

What is Synthesis

What is Synthesis? Synthesis writing is a form of analysis related to comparison and contrast, classification and division. On a basic level, synthesis requires the writer to pull together two or more summaries, looking for themes in each text. In synthesis, you search for the links between various materials in order to make your point. Most advanced academic writing, including literature reviews, relies heavily on synthesis. (Temple University Writing Center)

How To Synthesize Sources in a Literature Review

Literature reviews synthesize large amounts of information and present it in a coherent, organized fashion. In a literature review you will be combining material from several texts to create a new text – your literature review.

You will use common points among the sources you have gathered to help you synthesize the material. This will help ensure that your literature review is organized by subtopic, not by source. This means various authors' names can appear and reappear throughout the literature review, and each paragraph will mention several different authors.

When you shift from writing summaries of the content of a source to synthesizing content from sources, there is a number things you must keep in mind:

- Look for specific connections and or links between your sources and how those relate to your thesis or question.

- When writing and organizing your literature review be aware that your readers need to understand how and why the information from the different sources overlap.

- Organize your literature review by the themes you find within your sources or themes you have identified.

- << Previous: Things To Consider

- Next: Video Tutorials >>

- Last Updated: Nov 30, 2018 4:51 PM

- URL: https://libguides.csun.edu/literature-review

Report ADA Problems with Library Services and Resources

- Herron School of Art

- Ruth Lilly Law

- Ruth Lilly Medical

- School of Dentistry

Literature Review - A Self-Guided Tutorial

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Reading Journal Articles

- Does it describe a Literature Review?

- 1. Identify the question

- 2. Review discipline styles

- Searching article databases - video

- Finding the article full-text

- Citation chaining

- When to stop searching

- 4. Manage your references

- 5. Critically analyze and evaluate

- 6. Synthesize

- 7. Write literature review

Who's My Librarian?

Locate your University Library's subject librarian for personalized assistance.

Students doing research in specific areas may also request assistance at other IUPUI libraries:

- IU School of Dentistry Library

- Ruth Lilly Law Library

- Ruth Lilly Medical Library

You can sort the literature in various ways, for example:

Synthesis Matrix Example

From Jennifer Lim

- << Previous: 5. Critically analyze and evaluate

- Next: 7. Write literature review >>

- Last Updated: Jun 15, 2023 8:24 AM

- URL: https://iupui.libguides.com/literaturereview

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 7: Synthesizing Sources

Learning objectives.

At the conclusion of this chapter, you will be able to:

- synthesize key sources connecting them with the research question and topic area.

7.1 Overview of synthesizing

7.1.1 putting the pieces together.

Combining separate elements into a whole is the dictionary definition of synthesis. It is a way to make connections among and between numerous and varied source materials. A literature review is not an annotated bibliography, organized by title, author, or date of publication. Rather, it is grouped by topic to create a whole view of the literature relevant to your research question.

Your synthesis must demonstrate a critical analysis of the papers you collected as well as your ability to integrate the results of your analysis into your own literature review. Each paper collected should be critically evaluated and weighed for “adequacy, appropriateness, and thoroughness” ( Garrard, 2017 ) before inclusion in your own review. Papers that do not meet this criteria likely should not be included in your literature review.

Begin the synthesis process by creating a grid, table, or an outline where you will summarize, using common themes you have identified and the sources you have found. The summary grid or outline will help you compare and contrast the themes so you can see the relationships among them as well as areas where you may need to do more searching. Whichever method you choose, this type of organization will help you to both understand the information you find and structure the writing of your review. Remember, although “the means of summarizing can vary, the key at this point is to make sure you understand what you’ve found and how it relates to your topic and research question” ( Bennard et al., 2014 ).

As you read through the material you gather, look for common themes as they may provide the structure for your literature review. And, remember, research is an iterative process: it is not unusual to go back and search information sources for more material.

At one extreme, if you are claiming, ‘There are no prior publications on this topic,’ it is more likely that you have not found them yet and may need to broaden your search. At another extreme, writing a complete literature review can be difficult with a well-trod topic. Do not cite it all; instead cite what is most relevant. If that still leaves too much to include, be sure to reference influential sources…as well as high-quality work that clearly connects to the points you make. ( Klingner, Scanlon, & Pressley, 2005 ).

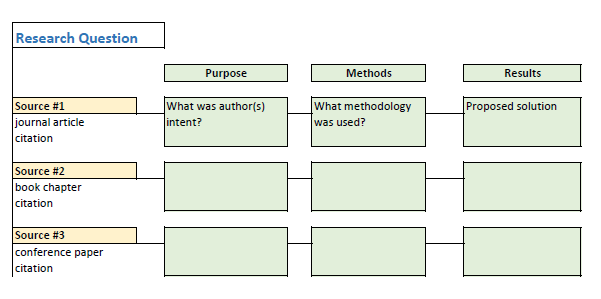

7.2 Creating a summary table

Literature reviews can be organized sequentially or by topic, theme, method, results, theory, or argument. It’s important to develop categories that are meaningful and relevant to your research question. Take detailed notes on each article and use a consistent format for capturing all the information each article provides. These notes and the summary table can be done manually, using note cards. However, given the amount of information you will be recording, an electronic file created in a word processing or spreadsheet is more manageable. Examples of fields you may want to capture in your notes include:

- Authors’ names

- Article title

- Publication year

- Main purpose of the article

- Methodology or research design

- Participants

- Measurement

- Conclusions

Other fields that will be useful when you begin to synthesize the sum total of your research:

- Specific details of the article or research that are especially relevant to your study

- Key terms and definitions

- Strengths or weaknesses in research design

- Relationships to other studies

- Possible gaps in the research or literature (for example, many research articles conclude with the statement “more research is needed in this area”)

- Finally, note how closely each article relates to your topic. You may want to rank these as high, medium, or low relevance. For papers that you decide not to include, you may want to note your reasoning for exclusion, such as ‘small sample size’, ‘local case study,’ or ‘lacks evidence to support assertion.’

This short video demonstrates how a nursing researcher might create a summary table.

7.2.1 Creating a Summary Table

Summary tables can be organized by author or by theme, for example:

For a summary table template, see http://blogs.monm.edu/writingatmc/files/2013/04/Synthesis-Matrix-Template.pdf

7.3 Creating a summary outline

An alternate way to organize your articles for synthesis it to create an outline. After you have collected the articles you intend to use (and have put aside the ones you won’t be using), it’s time to identify the conclusions that can be drawn from the articles as a group.

Based on your review of the collected articles, group them by categories. You may wish to further organize them by topic and then chronologically or alphabetically by author. For each topic or subtopic you identified during your critical analysis of the paper, determine what those papers have in common. Likewise, determine which ones in the group differ. If there are contradictory findings, you may be able to identify methodological or theoretical differences that could account for the contradiction (for example, differences in population demographics). Determine what general conclusions you can report about the topic or subtopic as the entire group of studies relate to it. For example, you may have several studies that agree on outcome, such as ‘hands on learning is best for science in elementary school’ or that ‘continuing education is the best method for updating nursing certification.’ In that case, you may want to organize by methodology used in the studies rather than by outcome.

Organize your outline in a logical order and prepare to write the first draft of your literature review. That order might be from broad to more specific, or it may be sequential or chronological, going from foundational literature to more current. Remember, “an effective literature review need not denote the entire historical record, but rather establish the raison d’etre for the current study and in doing so cite that literature distinctly pertinent for theoretical, methodological, or empirical reasons.” ( Milardo, 2015, p. 22 ).

As you organize the summarized documents into a logical structure, you are also appraising and synthesizing complex information from multiple sources. Your literature review is the result of your research that synthesizes new and old information and creates new knowledge.

7.4 Additional resources:

Literature Reviews: Using a Matrix to Organize Research / Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota

Literature Review: Synthesizing Multiple Sources / Indiana University

Writing a Literature Review and Using a Synthesis Matrix / Florida International University

Sample Literature Reviews Grid / Complied by Lindsay Roberts

Select three or four articles on a single topic of interest to you. Then enter them into an outline or table in the categories you feel are important to a research question. Try both the grid and the outline if you can to see which suits you better. The attached grid contains the fields suggested in the video .

Literature Review Table

Test yourself.

- Select two articles from your own summary table or outline and write a paragraph explaining how and why the sources relate to each other and your review of the literature.

- In your literature review, under what topic or subtopic will you place the paragraph you just wrote?

Image attribution

Literature Reviews for Education and Nursing Graduate Students Copyright © by Linda Frederiksen is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Writing in the Health and Social Sciences: Literature Reviews and Synthesis Tools

- Journal Publishing

- Style and Writing Guides

- Readings about Writing

- Citing in APA Style This link opens in a new window

- Resources for Dissertation Authors

- Citation Management and Formatting Tools

- What are Literature Reviews?

- Conducting & Reporting Systematic Reviews

- Finding Systematic Reviews

- Tutorials & Tools for Literature Reviews

Systematic Literature Reviews: Steps & Resources

These steps for conducting a systematic literature review are listed below .

Also see subpages for more information about:

- The different types of literature reviews, including systematic reviews and other evidence synthesis methods

- Tools & Tutorials

Literature Review & Systematic Review Steps

- Develop a Focused Question

- Scope the Literature (Initial Search)

- Refine & Expand the Search

- Limit the Results

- Download Citations

- Abstract & Analyze

- Create Flow Diagram

- Synthesize & Report Results

1. Develop a Focused Question

Consider the PICO Format: Population/Problem, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome

Focus on defining the Population or Problem and Intervention (don't narrow by Comparison or Outcome just yet!)

"What are the effects of the Pilates method for patients with low back pain?"

Tools & Additional Resources:

- PICO Question Help

- Stillwell, Susan B., DNP, RN, CNE; Fineout-Overholt, Ellen, PhD, RN, FNAP, FAAN; Melnyk, Bernadette Mazurek, PhD, RN, CPNP/PMHNP, FNAP, FAAN; Williamson, Kathleen M., PhD, RN Evidence-Based Practice, Step by Step: Asking the Clinical Question, AJN The American Journal of Nursing : March 2010 - Volume 110 - Issue 3 - p 58-61 doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000368959.11129.79

2. Scope the Literature

A "scoping search" investigates the breadth and/or depth of the initial question or may identify a gap in the literature.

Eligible studies may be located by searching in:

- Background sources (books, point-of-care tools)

- Article databases

- Trial registries

- Grey literature

- Cited references

- Reference lists

When searching, if possible, translate terms to controlled vocabulary of the database. Use text word searching when necessary.

Use Boolean operators to connect search terms:

- Combine separate concepts with AND (resulting in a narrower search)

- Connecting synonyms with OR (resulting in an expanded search)

Search: pilates AND ("low back pain" OR backache )

Video Tutorials - Translating PICO Questions into Search Queries

- Translate Your PICO Into a Search in PubMed (YouTube, Carrie Price, 5:11)

- Translate Your PICO Into a Search in CINAHL (YouTube, Carrie Price, 4:56)

3. Refine & Expand Your Search

Expand your search strategy with synonymous search terms harvested from:

- database thesauri

- reference lists

- relevant studies

Example:

(pilates OR exercise movement techniques) AND ("low back pain" OR backache* OR sciatica OR lumbago OR spondylosis)

As you develop a final, reproducible strategy for each database, save your strategies in a:

- a personal database account (e.g., MyNCBI for PubMed)

- Log in with your NYU credentials

- Open and "Make a Copy" to create your own tracker for your literature search strategies

4. Limit Your Results

Use database filters to limit your results based on your defined inclusion/exclusion criteria. In addition to relying on the databases' categorical filters, you may also need to manually screen results.

- Limit to Article type, e.g.,: "randomized controlled trial" OR multicenter study

- Limit by publication years, age groups, language, etc.

NOTE: Many databases allow you to filter to "Full Text Only". This filter is not recommended . It excludes articles if their full text is not available in that particular database (CINAHL, PubMed, etc), but if the article is relevant, it is important that you are able to read its title and abstract, regardless of 'full text' status. The full text is likely to be accessible through another source (a different database, or Interlibrary Loan).

- Filters in PubMed

- CINAHL Advanced Searching Tutorial

5. Download Citations

Selected citations and/or entire sets of search results can be downloaded from the database into a citation management tool. If you are conducting a systematic review that will require reporting according to PRISMA standards, a citation manager can help you keep track of the number of articles that came from each database, as well as the number of duplicate records.

In Zotero, you can create a Collection for the combined results set, and sub-collections for the results from each database you search. You can then use Zotero's 'Duplicate Items" function to find and merge duplicate records.

- Citation Managers - General Guide

6. Abstract and Analyze

- Migrate citations to data collection/extraction tool

- Screen Title/Abstracts for inclusion/exclusion

- Screen and appraise full text for relevance, methods,

- Resolve disagreements by consensus

Covidence is a web-based tool that enables you to work with a team to screen titles/abstracts and full text for inclusion in your review, as well as extract data from the included studies.

- Covidence Support

- Critical Appraisal Tools

- Data Extraction Tools

7. Create Flow Diagram

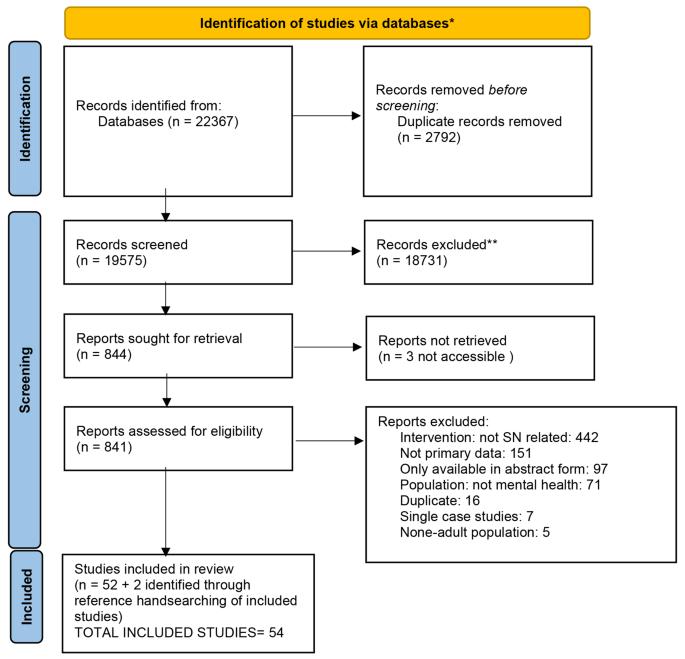

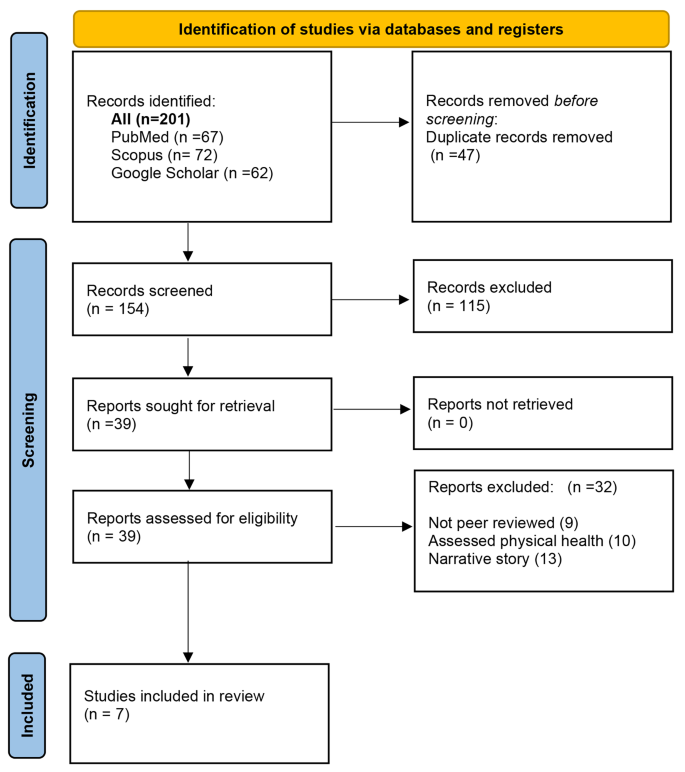

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram is a visual representation of the flow of records through different phases of a systematic review. It depicts the number of records identified, included and excluded. It is best used in conjunction with the PRISMA checklist .

Example from: Stotz, S. A., McNealy, K., Begay, R. L., DeSanto, K., Manson, S. M., & Moore, K. R. (2021). Multi-level diabetes prevention and treatment interventions for Native people in the USA and Canada: A scoping review. Current Diabetes Reports, 2 (11), 46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-021-01414-3

- PRISMA Flow Diagram Generator (ShinyApp.io, Haddaway et al. )

- PRISMA Diagram Templates (Word and PDF)

- Make a copy of the file to fill out the template

- Image can be downloaded as PDF, PNG, JPG, or SVG

- Covidence generates a PRISMA diagram that is automatically updated as records move through the review phases

8. Synthesize & Report Results

There are a number of reporting guideline available to guide the synthesis and reporting of results in systematic literature reviews.

It is common to organize findings in a matrix, also known as a Table of Evidence (ToE).

- Reporting Guidelines for Systematic Reviews

- Download a sample template of a health sciences review matrix (GoogleSheets)

Steps modified from:

Cook, D. A., & West, C. P. (2012). Conducting systematic reviews in medical education: a stepwise approach. Medical Education , 46 (10), 943–952.

- << Previous: Citation Management and Formatting Tools

- Next: What are Literature Reviews? >>

- Last Updated: Mar 19, 2024 11:31 AM

- URL: https://guides.nyu.edu/healthwriting

Synthesis and Literature Reviews

Why do we seek to understand the ways that authors or sources “converse” with one another?

So that we can synthesize various perspectives on a topic to more deeply understand it .

In academic writing, this understanding of the “conversation” may become the content of an explanatory synthesis paper – a paper in which you, the writer, point out various various themes or key points from a conversation on a particular topic.

Or, another assignment that you may complete in college is a literature review , which applies your synthesis skills. Literature reviews are often found in the beginning of scholarly journal articles. Literature reviews synthesize previous research that has been done on a particular topic, summarizing important works in the history of research on that topic.

- Literature reviews can be arranged by topic or theme , much like a traditional explanatory synthesis paper.

- Literature reviews can also be arranged chronologically , according to various time periods of research on a topic (i.e., what was published ten years ago, five years ago, and within the last year, for example).

- Finally, literature reviews can be arranged by discipline or field (i.e., what is the current research being done by biologists on this topic? What is the current research being done by psychologists on this topic? What is the current research being done by [insert academic discipline] on this topic?).

Just like in an explanatory synthesis paper, a Literature Review offers only a report on what others have already written about. The Literature Review does not reflect the author’s own argument or contributions to the field of research. Instead, it indicates that the author has read others’ important contributions and understands what has come before him or her.

The Literature Review provides context for the author’s own new research. It is the basis and background out of which the author’s research grows. Context = credibility in academic writing. When authors have broad Literature Review, they demonstrate their credibility as researchers.

English 102: Reading, Research, and Writing by Emilie Zickel is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Langson Library

- Science Library

- Grunigen Medical Library

- Law Library

- Connect From Off-Campus

- Accessibility

- Gateway Study Center

Email this link

Systematic reviews & evidence synthesis methods.

- Schedule a Consultation / Meet our Team

- What is Evidence Synthesis?

- Types of Evidence Synthesis

- Evidence Synthesis Across Disciplines

- Finding and Appraising Existing Systematic Reviews

- 0. Develop a Protocol

- 1. Draft your Research Question

- 2. Select Databases

- 3. Select Grey Literature Sources

- 4. Write a Search Strategy

- 5. Register a Protocol

- 6. Translate Search Strategies

- 7. Citation Management

- 8. Article Screening

- 9. Risk of Bias Assessment

- 10. Data Extraction

- 11. Synthesize, Map, or Describe the Results

- Open Access Evidence Synthesis Resources

What are Evidence Syntheses?

According to the Royal Society, 'evidence synthesis' refers to the process of bringing together information from a range of sources and disciplines to inform debates and decisions on specific issues. They generally include a methodical and comprehensive literature synthesis focused on a well-formulated research question. Their aim is to identify and synthesize all of the scholarly research on a particular topic, including both published and unpublished studies. Evidence syntheses are conducted in an unbiased, reproducible way to provide evidence for practice and policy-making, as well as to identify gaps in the research. Evidence syntheses may also include a meta-analysis, a more quantitative process of synthesizing and visualizing data retrieved from various studies.

Evidence syntheses are much more time-intensive than traditional literature reviews and require a multi-person research team. See this PredicTER tool to get a sense of a systematic review timeline (one type of evidence synthesis). Before embarking on an evidence synthesis, it's important to clearly identify your reasons for conducting one. For a list of types of evidence synthesis projects, see the Types of Evidence Synthesis tab.

How Does a Traditional Literature Review Differ From an Evidence Synthesis?

One commonly used form of evidence synthesis is a systematic review. This table compares a traditional literature review with a systematic review.

Video: Reproducibility and transparent methods (Video 3:25)

Reporting Standards

There are some reporting standards for evidence syntheses. These can serve as guidelines for protocol and manuscript preparation and journals may require that these standards are followed for the review type that is being employed (e.g. systematic review, scoping review, etc).

- PRISMA checklist Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

- PRISMA-P Standards An updated version of the original PRISMA standards for protocol development.

- PRISMA - ScR Reporting guidelines for scoping reviews and evidence maps

- PRISMA-IPD Standards Extension of the original PRISMA standards for systematic reviews and meta-analyses of individual participant data.

- EQUATOR Network The EQUATOR (Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research) Network is an international initiative that seeks to improve the reliability and value of published health research literature by promoting transparent and accurate reporting and wider use of robust reporting guidelines. They provide a list of various standards for reporting in systematic reviews.

Video: Guidelines and reporting standards

PRISMA Flow Diagram

The PRISMA flow diagram depicts the flow of information through the different phases of an evidence synthesis. It maps the search (number of records identified), screening (number of records included and excluded), and selection (reasons for exclusion). Many evidence syntheses include a PRISMA flow diagram in the published manuscript.

See below for resources to help you generate your own PRISMA flow diagram.

- PRISMA Flow Diagram Tool

- PRISMA Flow Diagram Word Template

- << Previous: Schedule a Consultation / Meet our Team

- Next: Types of Evidence Synthesis >>

- Last Updated: Feb 14, 2024 4:20 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uci.edu/evidence-synthesis

Off-campus? Please use the Software VPN and choose the group UCIFull to access licensed content. For more information, please Click here

Software VPN is not available for guests, so they may not have access to some content when connecting from off-campus.

Writing the Literature Review

- Getting Started

- Step 1: Choose A Topic

- Step 2: Find Information

- Step 3: Evaluate

- Step 4: Take Notes

- Step 5: Synthesize

- Step 6: Stay Organized

- Write the Review

Synthesizing

What is "Synthesis"?

Synthesis?

Synthesis refers to combining separate elements to create a whole. When reading through your sources (peer reviewed journal articles, books, research studies, white papers etc.) you will pay attention to relationships between the studies, between groups in the studies, and look for any pattterns, similarities or differences. Pay attention to methodologies, unexplored themes, and things that may represent a "gap" in the literature. These "gaps" will be things you will want to be sure to identify in your literature review.

- Using a Synthesis Matrix to Plan a Literature Review Introduction to synthesis matrices, and explanation of the difference between synthesis and analysis. (Geared towards Health Science/ Nursing but applicable for other literature reviews) ***Includes a synthesis matrix example***

- Using a Spider Diagram Organize your thoughts with a spider diagram

Ready, Set...Synthesize

- Create an outline that puts your topics (and subtopics) into a logical order

- Look at each subtopic that you have identified and determine what the articles in that group have in common with each other

- Look at the articles in those subtopics that you have identified and look for areas where they differ.

- If you spot findings that are contradictory, what differences do you think could account for those contradictions?

- Determine what general conclusions can be reported about that subtopic, and how it relates to the group of studies that you are discussing

- As you write, remember to follow your outline, and use transitions as you move between topics