Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

What Is a Theoretical Framework? | Guide to Organizing

Published on October 14, 2022 by Sarah Vinz . Revised on November 20, 2023 by Tegan George.

A theoretical framework is a foundational review of existing theories that serves as a roadmap for developing the arguments you will use in your own work.

Theories are developed by researchers to explain phenomena, draw connections, and make predictions. In a theoretical framework, you explain the existing theories that support your research, showing that your paper or dissertation topic is relevant and grounded in established ideas.

In other words, your theoretical framework justifies and contextualizes your later research, and it’s a crucial first step for your research paper , thesis , or dissertation . A well-rounded theoretical framework sets you up for success later on in your research and writing process.

Table of contents

Why do you need a theoretical framework, how to write a theoretical framework, structuring your theoretical framework, example of a theoretical framework, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about theoretical frameworks.

Before you start your own research, it’s crucial to familiarize yourself with the theories and models that other researchers have already developed. Your theoretical framework is your opportunity to present and explain what you’ve learned, situated within your future research topic.

There’s a good chance that many different theories about your topic already exist, especially if the topic is broad. In your theoretical framework, you will evaluate, compare, and select the most relevant ones.

By “framing” your research within a clearly defined field, you make the reader aware of the assumptions that inform your approach, showing the rationale behind your choices for later sections, like methodology and discussion . This part of your dissertation lays the foundations that will support your analysis, helping you interpret your results and make broader generalizations .

- In literature , a scholar using postmodernist literary theory would analyze The Great Gatsby differently than a scholar using Marxist literary theory.

- In psychology , a behaviorist approach to depression would involve different research methods and assumptions than a psychoanalytic approach.

- In economics , wealth inequality would be explained and interpreted differently based on a classical economics approach than based on a Keynesian economics one.

To create your own theoretical framework, you can follow these three steps:

- Identifying your key concepts

- Evaluating and explaining relevant theories

- Showing how your research fits into existing research

1. Identify your key concepts

The first step is to pick out the key terms from your problem statement and research questions . Concepts often have multiple definitions, so your theoretical framework should also clearly define what you mean by each term.

To investigate this problem, you have identified and plan to focus on the following problem statement, objective, and research questions:

Problem : Many online customers do not return to make subsequent purchases.

Objective : To increase the quantity of return customers.

Research question : How can the satisfaction of company X’s online customers be improved in order to increase the quantity of return customers?

2. Evaluate and explain relevant theories

By conducting a thorough literature review , you can determine how other researchers have defined these key concepts and drawn connections between them. As you write your theoretical framework, your aim is to compare and critically evaluate the approaches that different authors have taken.

After discussing different models and theories, you can establish the definitions that best fit your research and justify why. You can even combine theories from different fields to build your own unique framework if this better suits your topic.

Make sure to at least briefly mention each of the most important theories related to your key concepts. If there is a well-established theory that you don’t want to apply to your own research, explain why it isn’t suitable for your purposes.

3. Show how your research fits into existing research

Apart from summarizing and discussing existing theories, your theoretical framework should show how your project will make use of these ideas and take them a step further.

You might aim to do one or more of the following:

- Test whether a theory holds in a specific, previously unexamined context

- Use an existing theory as a basis for interpreting your results

- Critique or challenge a theory

- Combine different theories in a new or unique way

A theoretical framework can sometimes be integrated into a literature review chapter , but it can also be included as its own chapter or section in your dissertation. As a rule of thumb, if your research involves dealing with a lot of complex theories, it’s a good idea to include a separate theoretical framework chapter.

There are no fixed rules for structuring your theoretical framework, but it’s best to double-check with your department or institution to make sure they don’t have any formatting guidelines. The most important thing is to create a clear, logical structure. There are a few ways to do this:

- Draw on your research questions, structuring each section around a question or key concept

- Organize by theory cluster

- Organize by date

It’s important that the information in your theoretical framework is clear for your reader. Make sure to ask a friend to read this section for you, or use a professional proofreading service .

As in all other parts of your research paper , thesis , or dissertation , make sure to properly cite your sources to avoid plagiarism .

To get a sense of what this part of your thesis or dissertation might look like, take a look at our full example .

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Survivorship bias

- Self-serving bias

- Availability heuristic

- Halo effect

- Hindsight bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

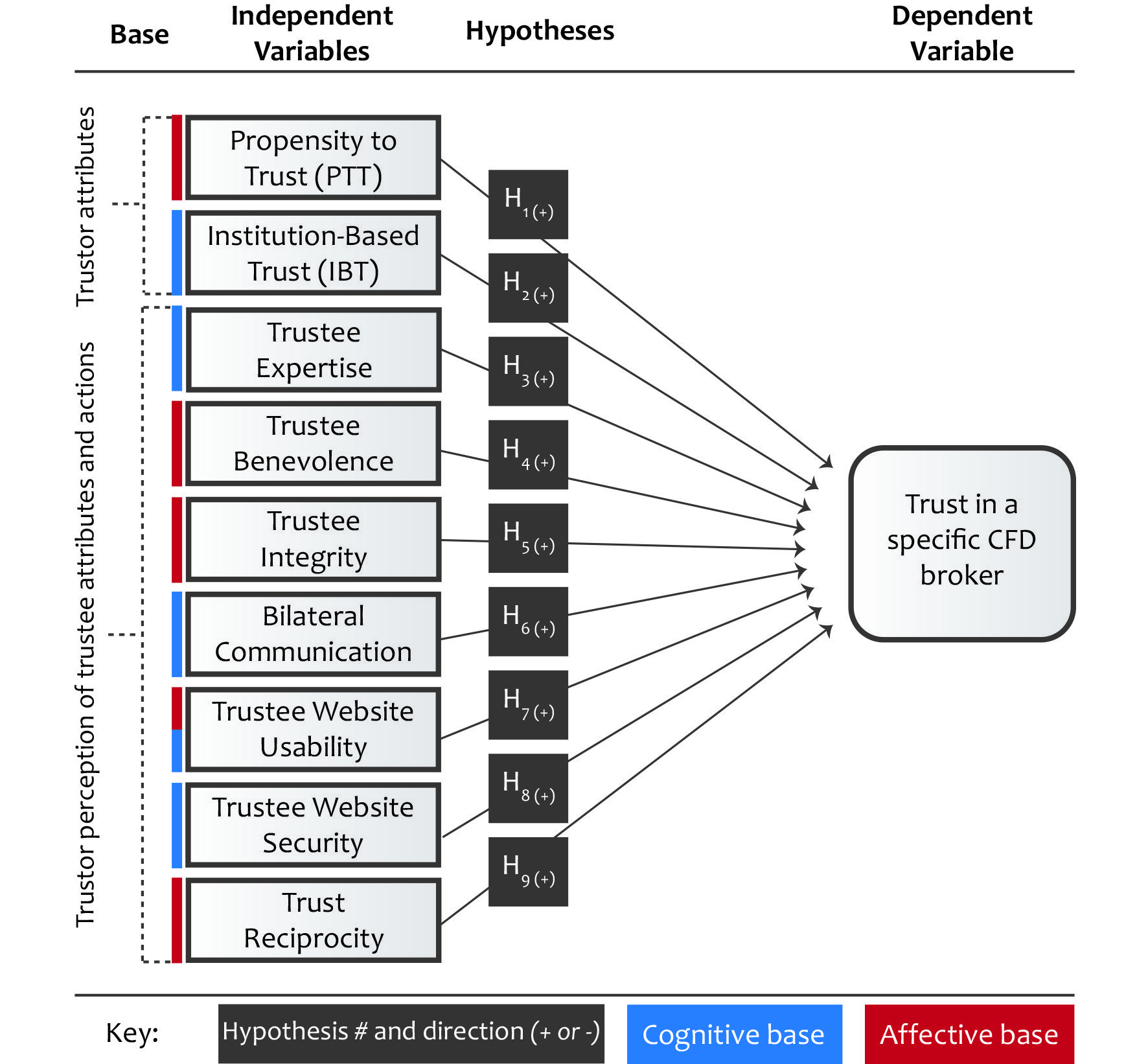

While a theoretical framework describes the theoretical underpinnings of your work based on existing research, a conceptual framework allows you to draw your own conclusions, mapping out the variables you may use in your study and the interplay between them.

A literature review and a theoretical framework are not the same thing and cannot be used interchangeably. While a theoretical framework describes the theoretical underpinnings of your work, a literature review critically evaluates existing research relating to your topic. You’ll likely need both in your dissertation .

A theoretical framework can sometimes be integrated into a literature review chapter , but it can also be included as its own chapter or section in your dissertation . As a rule of thumb, if your research involves dealing with a lot of complex theories, it’s a good idea to include a separate theoretical framework chapter.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Vinz, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Theoretical Framework? | Guide to Organizing. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/theoretical-framework/

Is this article helpful?

Sarah's academic background includes a Master of Arts in English, a Master of International Affairs degree, and a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science. She loves the challenge of finding the perfect formulation or wording and derives much satisfaction from helping students take their academic writing up a notch.

Other students also liked

What is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Theoretical Framework

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Theories are formulated to explain, predict, and understand phenomena and, in many cases, to challenge and extend existing knowledge within the limits of critical bounded assumptions or predictions of behavior. The theoretical framework is the structure that can hold or support a theory of a research study. The theoretical framework encompasses not just the theory, but the narrative explanation about how the researcher engages in using the theory and its underlying assumptions to investigate the research problem. It is the structure of your paper that summarizes concepts, ideas, and theories derived from prior research studies and which was synthesized in order to form a conceptual basis for your analysis and interpretation of meaning found within your research.

Abend, Gabriel. "The Meaning of Theory." Sociological Theory 26 (June 2008): 173–199; Kivunja, Charles. "Distinguishing between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework: A Systematic Review of Lessons from the Field." International Journal of Higher Education 7 (December 2018): 44-53; Swanson, Richard A. Theory Building in Applied Disciplines . San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers 2013; Varpio, Lara, Elise Paradis, Sebastian Uijtdehaage, and Meredith Young. "The Distinctions between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework." Academic Medicine 95 (July 2020): 989-994.

Importance of Theory and a Theoretical Framework

Theories can be unfamiliar to the beginning researcher because they are rarely applied in high school social studies curriculum and, as a result, can come across as unfamiliar and imprecise when first introduced as part of a writing assignment. However, in their most simplified form, a theory is simply a set of assumptions or predictions about something you think will happen based on existing evidence and that can be tested to see if those outcomes turn out to be true. Of course, it is slightly more deliberate than that, therefore, summarized from Kivunja (2018, p. 46), here are the essential characteristics of a theory.

- It is logical and coherent

- It has clear definitions of terms or variables, and has boundary conditions [i.e., it is not an open-ended statement]

- It has a domain where it applies

- It has clearly described relationships among variables

- It describes, explains, and makes specific predictions

- It comprises of concepts, themes, principles, and constructs

- It must have been based on empirical data [i.e., it is not a guess]

- It must have made claims that are subject to testing, been tested and verified

- It must be clear and concise

- Its assertions or predictions must be different and better than those in existing theories

- Its predictions must be general enough to be applicable to and understood within multiple contexts

- Its assertions or predictions are relevant, and if applied as predicted, will result in the predicted outcome

- The assertions and predictions are not immutable, but subject to revision and improvement as researchers use the theory to make sense of phenomena

- Its concepts and principles explain what is going on and why

- Its concepts and principles are substantive enough to enable us to predict a future

Given these characteristics, a theory can best be understood as the foundation from which you investigate assumptions or predictions derived from previous studies about the research problem, but in a way that leads to new knowledge and understanding as well as, in some cases, discovering how to improve the relevance of the theory itself or to argue that the theory is outdated and a new theory needs to be formulated based on new evidence.

A theoretical framework consists of concepts and, together with their definitions and reference to relevant scholarly literature, existing theory that is used for your particular study. The theoretical framework must demonstrate an understanding of theories and concepts that are relevant to the topic of your research paper and that relate to the broader areas of knowledge being considered.

The theoretical framework is most often not something readily found within the literature . You must review course readings and pertinent research studies for theories and analytic models that are relevant to the research problem you are investigating. The selection of a theory should depend on its appropriateness, ease of application, and explanatory power.

The theoretical framework strengthens the study in the following ways :

- An explicit statement of theoretical assumptions permits the reader to evaluate them critically.

- The theoretical framework connects the researcher to existing knowledge. Guided by a relevant theory, you are given a basis for your hypotheses and choice of research methods.

- Articulating the theoretical assumptions of a research study forces you to address questions of why and how. It permits you to intellectually transition from simply describing a phenomenon you have observed to generalizing about various aspects of that phenomenon.

- Having a theory helps you identify the limits to those generalizations. A theoretical framework specifies which key variables influence a phenomenon of interest and highlights the need to examine how those key variables might differ and under what circumstances.

- The theoretical framework adds context around the theory itself based on how scholars had previously tested the theory in relation their overall research design [i.e., purpose of the study, methods of collecting data or information, methods of analysis, the time frame in which information is collected, study setting, and the methodological strategy used to conduct the research].

By virtue of its applicative nature, good theory in the social sciences is of value precisely because it fulfills one primary purpose: to explain the meaning, nature, and challenges associated with a phenomenon, often experienced but unexplained in the world in which we live, so that we may use that knowledge and understanding to act in more informed and effective ways.

The Conceptual Framework. College of Education. Alabama State University; Corvellec, Hervé, ed. What is Theory?: Answers from the Social and Cultural Sciences . Stockholm: Copenhagen Business School Press, 2013; Asher, Herbert B. Theory-Building and Data Analysis in the Social Sciences . Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1984; Drafting an Argument. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Kivunja, Charles. "Distinguishing between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework: A Systematic Review of Lessons from the Field." International Journal of Higher Education 7 (2018): 44-53; Omodan, Bunmi Isaiah. "A Model for Selecting Theoretical Framework through Epistemology of Research Paradigms." African Journal of Inter/Multidisciplinary Studies 4 (2022): 275-285; Ravitch, Sharon M. and Matthew Riggan. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2017; Trochim, William M.K. Philosophy of Research. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Jarvis, Peter. The Practitioner-Researcher. Developing Theory from Practice . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1999.

Strategies for Developing the Theoretical Framework

I. Developing the Framework

Here are some strategies to develop of an effective theoretical framework:

- Examine your thesis title and research problem . The research problem anchors your entire study and forms the basis from which you construct your theoretical framework.

- Brainstorm about what you consider to be the key variables in your research . Answer the question, "What factors contribute to the presumed effect?"

- Review related literature to find how scholars have addressed your research problem. Identify the assumptions from which the author(s) addressed the problem.

- List the constructs and variables that might be relevant to your study. Group these variables into independent and dependent categories.

- Review key social science theories that are introduced to you in your course readings and choose the theory that can best explain the relationships between the key variables in your study [note the Writing Tip on this page].

- Discuss the assumptions or propositions of this theory and point out their relevance to your research.

A theoretical framework is used to limit the scope of the relevant data by focusing on specific variables and defining the specific viewpoint [framework] that the researcher will take in analyzing and interpreting the data to be gathered. It also facilitates the understanding of concepts and variables according to given definitions and builds new knowledge by validating or challenging theoretical assumptions.

II. Purpose

Think of theories as the conceptual basis for understanding, analyzing, and designing ways to investigate relationships within social systems. To that end, the following roles served by a theory can help guide the development of your framework.

- Means by which new research data can be interpreted and coded for future use,

- Response to new problems that have no previously identified solutions strategy,

- Means for identifying and defining research problems,

- Means for prescribing or evaluating solutions to research problems,

- Ways of discerning certain facts among the accumulated knowledge that are important and which facts are not,

- Means of giving old data new interpretations and new meaning,

- Means by which to identify important new issues and prescribe the most critical research questions that need to be answered to maximize understanding of the issue,

- Means of providing members of a professional discipline with a common language and a frame of reference for defining the boundaries of their profession, and

- Means to guide and inform research so that it can, in turn, guide research efforts and improve professional practice.

Adapted from: Torraco, R. J. “Theory-Building Research Methods.” In Swanson R. A. and E. F. Holton III , editors. Human Resource Development Handbook: Linking Research and Practice . (San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler, 1997): pp. 114-137; Jacard, James and Jacob Jacoby. Theory Construction and Model-Building Skills: A Practical Guide for Social Scientists . New York: Guilford, 2010; Ravitch, Sharon M. and Matthew Riggan. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2017; Sutton, Robert I. and Barry M. Staw. “What Theory is Not.” Administrative Science Quarterly 40 (September 1995): 371-384.

Structure and Writing Style

The theoretical framework may be rooted in a specific theory , in which case, your work is expected to test the validity of that existing theory in relation to specific events, issues, or phenomena. Many social science research papers fit into this rubric. For example, Peripheral Realism Theory, which categorizes perceived differences among nation-states as those that give orders, those that obey, and those that rebel, could be used as a means for understanding conflicted relationships among countries in Africa. A test of this theory could be the following: Does Peripheral Realism Theory help explain intra-state actions, such as, the disputed split between southern and northern Sudan that led to the creation of two nations?

However, you may not always be asked by your professor to test a specific theory in your paper, but to develop your own framework from which your analysis of the research problem is derived . Based upon the above example, it is perhaps easiest to understand the nature and function of a theoretical framework if it is viewed as an answer to two basic questions:

- What is the research problem/question? [e.g., "How should the individual and the state relate during periods of conflict?"]

- Why is your approach a feasible solution? [i.e., justify the application of your choice of a particular theory and explain why alternative constructs were rejected. I could choose instead to test Instrumentalist or Circumstantialists models developed among ethnic conflict theorists that rely upon socio-economic-political factors to explain individual-state relations and to apply this theoretical model to periods of war between nations].

The answers to these questions come from a thorough review of the literature and your course readings [summarized and analyzed in the next section of your paper] and the gaps in the research that emerge from the review process. With this in mind, a complete theoretical framework will likely not emerge until after you have completed a thorough review of the literature .

Just as a research problem in your paper requires contextualization and background information, a theory requires a framework for understanding its application to the topic being investigated. When writing and revising this part of your research paper, keep in mind the following:

- Clearly describe the framework, concepts, models, or specific theories that underpin your study . This includes noting who the key theorists are in the field who have conducted research on the problem you are investigating and, when necessary, the historical context that supports the formulation of that theory. This latter element is particularly important if the theory is relatively unknown or it is borrowed from another discipline.

- Position your theoretical framework within a broader context of related frameworks, concepts, models, or theories . As noted in the example above, there will likely be several concepts, theories, or models that can be used to help develop a framework for understanding the research problem. Therefore, note why the theory you've chosen is the appropriate one.

- The present tense is used when writing about theory. Although the past tense can be used to describe the history of a theory or the role of key theorists, the construction of your theoretical framework is happening now.

- You should make your theoretical assumptions as explicit as possible . Later, your discussion of methodology should be linked back to this theoretical framework.

- Don’t just take what the theory says as a given! Reality is never accurately represented in such a simplistic way; if you imply that it can be, you fundamentally distort a reader's ability to understand the findings that emerge. Given this, always note the limitations of the theoretical framework you've chosen [i.e., what parts of the research problem require further investigation because the theory inadequately explains a certain phenomena].

The Conceptual Framework. College of Education. Alabama State University; Conceptual Framework: What Do You Think is Going On? College of Engineering. University of Michigan; Drafting an Argument. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Lynham, Susan A. “The General Method of Theory-Building Research in Applied Disciplines.” Advances in Developing Human Resources 4 (August 2002): 221-241; Tavallaei, Mehdi and Mansor Abu Talib. "A General Perspective on the Role of Theory in Qualitative Research." Journal of International Social Research 3 (Spring 2010); Ravitch, Sharon M. and Matthew Riggan. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2017; Reyes, Victoria. Demystifying the Journal Article. Inside Higher Education; Trochim, William M.K. Philosophy of Research. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Weick, Karl E. “The Work of Theorizing.” In Theorizing in Social Science: The Context of Discovery . Richard Swedberg, editor. (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014), pp. 177-194.

Writing Tip

Borrowing Theoretical Constructs from Other Disciplines

An increasingly important trend in the social and behavioral sciences is to think about and attempt to understand research problems from an interdisciplinary perspective. One way to do this is to not rely exclusively on the theories developed within your particular discipline, but to think about how an issue might be informed by theories developed in other disciplines. For example, if you are a political science student studying the rhetorical strategies used by female incumbents in state legislature campaigns, theories about the use of language could be derived, not only from political science, but linguistics, communication studies, philosophy, psychology, and, in this particular case, feminist studies. Building theoretical frameworks based on the postulates and hypotheses developed in other disciplinary contexts can be both enlightening and an effective way to be more engaged in the research topic.

CohenMiller, A. S. and P. Elizabeth Pate. "A Model for Developing Interdisciplinary Research Theoretical Frameworks." The Qualitative Researcher 24 (2019): 1211-1226; Frodeman, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity . New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Undertheorize!

Do not leave the theory hanging out there in the introduction never to be mentioned again. Undertheorizing weakens your paper. The theoretical framework you describe should guide your study throughout the paper. Be sure to always connect theory to the review of pertinent literature and to explain in the discussion part of your paper how the theoretical framework you chose supports analysis of the research problem or, if appropriate, how the theoretical framework was found to be inadequate in explaining the phenomenon you were investigating. In that case, don't be afraid to propose your own theory based on your findings.

Yet Another Writing Tip

What's a Theory? What's a Hypothesis?

The terms theory and hypothesis are often used interchangeably in newspapers and popular magazines and in non-academic settings. However, the difference between theory and hypothesis in scholarly research is important, particularly when using an experimental design. A theory is a well-established principle that has been developed to explain some aspect of the natural world. Theories arise from repeated observation and testing and incorporates facts, laws, predictions, and tested assumptions that are widely accepted [e.g., rational choice theory; grounded theory; critical race theory].

A hypothesis is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in your study. For example, an experiment designed to look at the relationship between study habits and test anxiety might have a hypothesis that states, "We predict that students with better study habits will suffer less test anxiety." Unless your study is exploratory in nature, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen during the course of your research.

The key distinctions are:

- A theory predicts events in a broad, general context; a hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a specified set of circumstances.

- A theory has been extensively tested and is generally accepted among a set of scholars; a hypothesis is a speculative guess that has yet to be tested.

Cherry, Kendra. Introduction to Research Methods: Theory and Hypothesis. About.com Psychology; Gezae, Michael et al. Welcome Presentation on Hypothesis. Slideshare presentation.

Still Yet Another Writing Tip

Be Prepared to Challenge the Validity of an Existing Theory

Theories are meant to be tested and their underlying assumptions challenged; they are not rigid or intransigent, but are meant to set forth general principles for explaining phenomena or predicting outcomes. Given this, testing theoretical assumptions is an important way that knowledge in any discipline develops and grows. If you're asked to apply an existing theory to a research problem, the analysis will likely include the expectation by your professor that you should offer modifications to the theory based on your research findings.

Indications that theoretical assumptions may need to be modified can include the following:

- Your findings suggest that the theory does not explain or account for current conditions or circumstances or the passage of time,

- The study reveals a finding that is incompatible with what the theory attempts to explain or predict, or

- Your analysis reveals that the theory overly generalizes behaviors or actions without taking into consideration specific factors revealed from your analysis [e.g., factors related to culture, nationality, history, gender, ethnicity, age, geographic location, legal norms or customs , religion, social class, socioeconomic status, etc.].

Philipsen, Kristian. "Theory Building: Using Abductive Search Strategies." In Collaborative Research Design: Working with Business for Meaningful Findings . Per Vagn Freytag and Louise Young, editors. (Singapore: Springer Nature, 2018), pp. 45-71; Shepherd, Dean A. and Roy Suddaby. "Theory Building: A Review and Integration." Journal of Management 43 (2017): 59-86.

- << Previous: The Research Problem/Question

- Next: 5. The Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 1:27 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Theoretical Framework – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Theoretical Framework – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Theoretical Framework

Definition:

Theoretical framework refers to a set of concepts, theories, ideas , and assumptions that serve as a foundation for understanding a particular phenomenon or problem. It provides a conceptual framework that helps researchers to design and conduct their research, as well as to analyze and interpret their findings.

In research, a theoretical framework explains the relationship between various variables, identifies gaps in existing knowledge, and guides the development of research questions, hypotheses, and methodologies. It also helps to contextualize the research within a broader theoretical perspective, and can be used to guide the interpretation of results and the formulation of recommendations.

Types of Theoretical Framework

Types of Types of Theoretical Framework are as follows:

Conceptual Framework

This type of framework defines the key concepts and relationships between them. It helps to provide a theoretical foundation for a study or research project .

Deductive Framework

This type of framework starts with a general theory or hypothesis and then uses data to test and refine it. It is often used in quantitative research .

Inductive Framework

This type of framework starts with data and then develops a theory or hypothesis based on the patterns and themes that emerge from the data. It is often used in qualitative research .

Empirical Framework

This type of framework focuses on the collection and analysis of empirical data, such as surveys or experiments. It is often used in scientific research .

Normative Framework

This type of framework defines a set of norms or values that guide behavior or decision-making. It is often used in ethics and social sciences.

Explanatory Framework

This type of framework seeks to explain the underlying mechanisms or causes of a particular phenomenon or behavior. It is often used in psychology and social sciences.

Components of Theoretical Framework

The components of a theoretical framework include:

- Concepts : The basic building blocks of a theoretical framework. Concepts are abstract ideas or generalizations that represent objects, events, or phenomena.

- Variables : These are measurable and observable aspects of a concept. In a research context, variables can be manipulated or measured to test hypotheses.

- Assumptions : These are beliefs or statements that are taken for granted and are not tested in a study. They provide a starting point for developing hypotheses.

- Propositions : These are statements that explain the relationships between concepts and variables in a theoretical framework.

- Hypotheses : These are testable predictions that are derived from the theoretical framework. Hypotheses are used to guide data collection and analysis.

- Constructs : These are abstract concepts that cannot be directly measured but are inferred from observable variables. Constructs provide a way to understand complex phenomena.

- Models : These are simplified representations of reality that are used to explain, predict, or control a phenomenon.

How to Write Theoretical Framework

A theoretical framework is an essential part of any research study or paper, as it helps to provide a theoretical basis for the research and guide the analysis and interpretation of the data. Here are some steps to help you write a theoretical framework:

- Identify the key concepts and variables : Start by identifying the main concepts and variables that your research is exploring. These could include things like motivation, behavior, attitudes, or any other relevant concepts.

- Review relevant literature: Conduct a thorough review of the existing literature in your field to identify key theories and ideas that relate to your research. This will help you to understand the existing knowledge and theories that are relevant to your research and provide a basis for your theoretical framework.

- Develop a conceptual framework : Based on your literature review, develop a conceptual framework that outlines the key concepts and their relationships. This framework should provide a clear and concise overview of the theoretical perspective that underpins your research.

- Identify hypotheses and research questions: Based on your conceptual framework, identify the hypotheses and research questions that you want to test or explore in your research.

- Test your theoretical framework: Once you have developed your theoretical framework, test it by applying it to your research data. This will help you to identify any gaps or weaknesses in your framework and refine it as necessary.

- Write up your theoretical framework: Finally, write up your theoretical framework in a clear and concise manner, using appropriate terminology and referencing the relevant literature to support your arguments.

Theoretical Framework Examples

Here are some examples of theoretical frameworks:

- Social Learning Theory : This framework, developed by Albert Bandura, suggests that people learn from their environment, including the behaviors of others, and that behavior is influenced by both external and internal factors.

- Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs : Abraham Maslow proposed that human needs are arranged in a hierarchy, with basic physiological needs at the bottom, followed by safety, love and belonging, esteem, and self-actualization at the top. This framework has been used in various fields, including psychology and education.

- Ecological Systems Theory : This framework, developed by Urie Bronfenbrenner, suggests that a person’s development is influenced by the interaction between the individual and the various environments in which they live, such as family, school, and community.

- Feminist Theory: This framework examines how gender and power intersect to influence social, cultural, and political issues. It emphasizes the importance of understanding and challenging systems of oppression.

- Cognitive Behavioral Theory: This framework suggests that our thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes influence our behavior, and that changing our thought patterns can lead to changes in behavior and emotional responses.

- Attachment Theory: This framework examines the ways in which early relationships with caregivers shape our later relationships and attachment styles.

- Critical Race Theory : This framework examines how race intersects with other forms of social stratification and oppression to perpetuate inequality and discrimination.

When to Have A Theoretical Framework

Following are some situations When to Have A Theoretical Framework:

- A theoretical framework should be developed when conducting research in any discipline, as it provides a foundation for understanding the research problem and guiding the research process.

- A theoretical framework is essential when conducting research on complex phenomena, as it helps to organize and structure the research questions, hypotheses, and findings.

- A theoretical framework should be developed when the research problem requires a deeper understanding of the underlying concepts and principles that govern the phenomenon being studied.

- A theoretical framework is particularly important when conducting research in social sciences, as it helps to explain the relationships between variables and provides a framework for testing hypotheses.

- A theoretical framework should be developed when conducting research in applied fields, such as engineering or medicine, as it helps to provide a theoretical basis for the development of new technologies or treatments.

- A theoretical framework should be developed when conducting research that seeks to address a specific gap in knowledge, as it helps to define the problem and identify potential solutions.

- A theoretical framework is also important when conducting research that involves the analysis of existing theories or concepts, as it helps to provide a framework for comparing and contrasting different theories and concepts.

- A theoretical framework should be developed when conducting research that seeks to make predictions or develop generalizations about a particular phenomenon, as it helps to provide a basis for evaluating the accuracy of these predictions or generalizations.

- Finally, a theoretical framework should be developed when conducting research that seeks to make a contribution to the field, as it helps to situate the research within the broader context of the discipline and identify its significance.

Purpose of Theoretical Framework

The purposes of a theoretical framework include:

- Providing a conceptual framework for the study: A theoretical framework helps researchers to define and clarify the concepts and variables of interest in their research. It enables researchers to develop a clear and concise definition of the problem, which in turn helps to guide the research process.

- Guiding the research design: A theoretical framework can guide the selection of research methods, data collection techniques, and data analysis procedures. By outlining the key concepts and assumptions underlying the research questions, the theoretical framework can help researchers to identify the most appropriate research design for their study.

- Supporting the interpretation of research findings: A theoretical framework provides a framework for interpreting the research findings by helping researchers to make connections between their findings and existing theory. It enables researchers to identify the implications of their findings for theory development and to assess the generalizability of their findings.

- Enhancing the credibility of the research: A well-developed theoretical framework can enhance the credibility of the research by providing a strong theoretical foundation for the study. It demonstrates that the research is based on a solid understanding of the relevant theory and that the research questions are grounded in a clear conceptual framework.

- Facilitating communication and collaboration: A theoretical framework provides a common language and conceptual framework for researchers, enabling them to communicate and collaborate more effectively. It helps to ensure that everyone involved in the research is working towards the same goals and is using the same concepts and definitions.

Characteristics of Theoretical Framework

Some of the characteristics of a theoretical framework include:

- Conceptual clarity: The concepts used in the theoretical framework should be clearly defined and understood by all stakeholders.

- Logical coherence : The framework should be internally consistent, with each concept and assumption logically connected to the others.

- Empirical relevance: The framework should be based on empirical evidence and research findings.

- Parsimony : The framework should be as simple as possible, without sacrificing its ability to explain the phenomenon in question.

- Flexibility : The framework should be adaptable to new findings and insights.

- Testability : The framework should be testable through research, with clear hypotheses that can be falsified or supported by data.

- Applicability : The framework should be useful for practical applications, such as designing interventions or policies.

Advantages of Theoretical Framework

Here are some of the advantages of having a theoretical framework:

- Provides a clear direction : A theoretical framework helps researchers to identify the key concepts and variables they need to study and the relationships between them. This provides a clear direction for the research and helps researchers to focus their efforts and resources.

- Increases the validity of the research: A theoretical framework helps to ensure that the research is based on sound theoretical principles and concepts. This increases the validity of the research by ensuring that it is grounded in established knowledge and is not based on arbitrary assumptions.

- Enables comparisons between studies : A theoretical framework provides a common language and set of concepts that researchers can use to compare and contrast their findings. This helps to build a cumulative body of knowledge and allows researchers to identify patterns and trends across different studies.

- Helps to generate hypotheses: A theoretical framework provides a basis for generating hypotheses about the relationships between different concepts and variables. This can help to guide the research process and identify areas that require further investigation.

- Facilitates communication: A theoretical framework provides a common language and set of concepts that researchers can use to communicate their findings to other researchers and to the wider community. This makes it easier for others to understand the research and its implications.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

What is a Theoretical Framework? | A Step-by-Step Guide

Published on 14 February 2020 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 10 October 2022.

A theoretical framework is a foundational review of existing theories that serves as a roadmap for developing the arguments you will use in your own work.

Theories are developed by researchers to explain phenomena, draw connections, and make predictions. In a theoretical framework, you explain the existing theories that support your research, showing that your work is grounded in established ideas.

In other words, your theoretical framework justifies and contextualises your later research, and it’s a crucial first step for your research paper , thesis, or dissertation . A well-rounded theoretical framework sets you up for success later on in your research and writing process.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why do you need a theoretical framework, how to write a theoretical framework, structuring your theoretical framework, example of a theoretical framework, frequently asked questions about theoretical frameworks.

Before you start your own research, it’s crucial to familiarise yourself with the theories and models that other researchers have already developed. Your theoretical framework is your opportunity to present and explain what you’ve learned, situated within your future research topic.

There’s a good chance that many different theories about your topic already exist, especially if the topic is broad. In your theoretical framework, you will evaluate, compare, and select the most relevant ones.

By “framing” your research within a clearly defined field, you make the reader aware of the assumptions that inform your approach, showing the rationale behind your choices for later sections, like methodology and discussion . This part of your dissertation lays the foundations that will support your analysis, helping you interpret your results and make broader generalisations .

- In literature , a scholar using postmodernist literary theory would analyse The Great Gatsby differently than a scholar using Marxist literary theory.

- In psychology , a behaviourist approach to depression would involve different research methods and assumptions than a psychoanalytic approach.

- In economics , wealth inequality would be explained and interpreted differently based on a classical economics approach than based on a Keynesian economics one.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

To create your own theoretical framework, you can follow these three steps:

- Identifying your key concepts

- Evaluating and explaining relevant theories

- Showing how your research fits into existing research

1. Identify your key concepts

The first step is to pick out the key terms from your problem statement and research questions . Concepts often have multiple definitions, so your theoretical framework should also clearly define what you mean by each term.

To investigate this problem, you have identified and plan to focus on the following problem statement, objective, and research questions:

Problem : Many online customers do not return to make subsequent purchases.

Objective : To increase the quantity of return customers.

Research question : How can the satisfaction of company X’s online customers be improved in order to increase the quantity of return customers?

2. Evaluate and explain relevant theories

By conducting a thorough literature review , you can determine how other researchers have defined these key concepts and drawn connections between them. As you write your theoretical framework, your aim is to compare and critically evaluate the approaches that different authors have taken.

After discussing different models and theories, you can establish the definitions that best fit your research and justify why. You can even combine theories from different fields to build your own unique framework if this better suits your topic.

Make sure to at least briefly mention each of the most important theories related to your key concepts. If there is a well-established theory that you don’t want to apply to your own research, explain why it isn’t suitable for your purposes.

3. Show how your research fits into existing research

Apart from summarising and discussing existing theories, your theoretical framework should show how your project will make use of these ideas and take them a step further.

You might aim to do one or more of the following:

- Test whether a theory holds in a specific, previously unexamined context

- Use an existing theory as a basis for interpreting your results

- Critique or challenge a theory

- Combine different theories in a new or unique way

A theoretical framework can sometimes be integrated into a literature review chapter , but it can also be included as its own chapter or section in your dissertation. As a rule of thumb, if your research involves dealing with a lot of complex theories, it’s a good idea to include a separate theoretical framework chapter.

There are no fixed rules for structuring your theoretical framework, but it’s best to double-check with your department or institution to make sure they don’t have any formatting guidelines. The most important thing is to create a clear, logical structure. There are a few ways to do this:

- Draw on your research questions, structuring each section around a question or key concept

- Organise by theory cluster

- Organise by date

As in all other parts of your research paper , thesis, or dissertation , make sure to properly cite your sources to avoid plagiarism .

To get a sense of what this part of your thesis or dissertation might look like, take a look at our full example .

While a theoretical framework describes the theoretical underpinnings of your work based on existing research, a conceptual framework allows you to draw your own conclusions, mapping out the variables you may use in your study and the interplay between them.

A literature review and a theoretical framework are not the same thing and cannot be used interchangeably. While a theoretical framework describes the theoretical underpinnings of your work, a literature review critically evaluates existing research relating to your topic. You’ll likely need both in your dissertation .

A theoretical framework can sometimes be integrated into a literature review chapter , but it can also be included as its own chapter or section in your dissertation . As a rule of thumb, if your research involves dealing with a lot of complex theories, it’s a good idea to include a separate theoretical framework chapter.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, October 10). What is a Theoretical Framework? | A Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved 9 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/the-theoretical-framework/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples, how to write a results section | tips & examples, how to write a discussion section | tips & examples.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

5.5 Developing a theoretical framework

Social work researchers develop theoretical frameworks based on social science theories and empirical literature. A study’s theory describes the theoretical foundations of the research and consists of the big-T theory(ies) that guide the investigation. It provides overarching perspectives, explanations, and predictions about the social problem and research topic.

In deductive research (e.g., quantitative research), researchers create a theoretical framework to explain the thought process behind the study’s research questions and hypotheses. The theoretical framework includes the constructs of interest in the study and the associations the researchers expect to find. These constructs and their relations are based on the broader theory, but likely do not entail all the components of the theory. The theoretical framework is specific to a particular study or analysis and provides the rationale for the research question(s). In inductive studies such as grounded theory, a theoretical framework can be the final result of the research. In this case, the theoretical framework is also a combination of concepts and their associations, but it is derived from the data collected during the research. This contrasts to theoretical frameworks in deductive research, which are created before collecting data and derive from theories and other empirical findings.

In Chapter 8, we will develop your quantitative theoretical framework further, identifying associations or causal relations in a research question. Developing a quantitative theoretical framework is also instructive for revising and clarifying your working research question and identifying concepts that serve as keywords for additional literature searching. But first, we will consider identifying your theory. The greater clarity you have with your theoretical perspective, the easier each subsequent step in the research process will be. Getting acquainted with the important theoretical concepts in a new area can be challenging. While social work education provides a broad overview of social theory, you will find much greater fulfillment out of reading about the theories related to your topic area. We discussed some strategies for finding theoretical information in Chapter 3 as part of literature searching. To extend that conversation a bit, some strategies for searching for theories in the literature include:

- Consider searching for these keywords in the title or abstract, specifically

- Looking at the references and cited by links within theoretical articles and textbooks

- Looking at books, edited volumes, and textbooks that discuss theory

- Talking with a scholar on your topic, or asking a professor if they can help connect you to someone

- It is helpful when authors are clear about how they use theory to inform their research project, usually in the introduction and discussion section.

- For example, from the broad umbrella of systems theory, you might pick out family systems theory if you want to understand the effectiveness of a family counseling program.

It’s important to remember that knowledge arises within disciplines, and that disciplines have different theoretical frameworks for explaining the same topic. While it is certainly important for the social work perspective to be a part of your analysis, social workers benefit from searching across disciplines to come to a more comprehensive understanding of the topic. Reaching across disciplines can provide uncommon insights during conceptualization, and once the study is completed, a multidisciplinary researcher will be able to share results in a way that speaks to a variety of audiences. A study by An and colleagues (2015) [1] uses game theory from the discipline of economics to understand problems in the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. In order to receive TANF benefits, mothers must cooperate with paternity and child support requirements unless they have “good cause,” as in cases of domestic violence, in which providing that information would put the mother at greater risk of violence. Game theory can help us understand how TANF recipients and caseworkers respond to the incentives in their environment, and highlight why the design of the “good cause” waiver program may not achieve its intended outcome of increasing access to benefits for survivors of family abuse.

Of course, there are natural limits on the depth with which student researchers can and should engage in a search for theory about their topic. At minimum, you should be able to draw connections across studies and be able to assess the relative importance of each theory within the literature. Just because you found one article applying your theory (like game theory, in our example above) does not mean it is important or often used in the domestic violence literature. Indeed, it would be much more common in the family violence literature to find psychological theories of trauma, feminist theories of power and control, and similar theoretical perspectives used to inform research projects rather than game theory, which is equally applicable to survivors of family violence as workers and bosses at a corporation. Consider using the Cited By feature to identify articles, books, and other sources of theoretical information that are seminal or well-cited in the literature. Similarly, by using the name of a theory in the keywords of a search query (along with keywords related to your topic), you can get a sense of how often the theory is used in your topic area. You should have a sense of what theories are commonly used to analyze your topic, even if you end up choosing a different one to inform your project.

Theories that are not cited or used as often are still immensely valuable. As we saw before with TANF and “good cause” waivers, using theories from other disciplines can produce uncommon insights and help you make a new contribution to the social work literature. Given the privileged position that the social work curriculum places on theories developed by white men, students may want to explore Afrocentricity as a social work practice theory (Pellebon, 2007) [2] or abolitionist social work (Jacobs et al., 2021) [3] when deciding on a theoretical framework for their research project that addresses concepts of racial justice. Start with your working question, and explain how each theory helps you answer your question. Some explanations are going to feel right, and some concepts will feel more salient to you than others. Keep in mind that this is an iterative process. Your theoretical framework will likely change as you continue to conceptualize your research project, revise your research question, and design your study.

By trying on many different theoretical explanations for your topic area, you can better clarify your own theoretical framework. Some of you may be fortunate enough to find theories that match perfectly with how you think about your topic, are used often in the literature, and are therefore relatively straightforward to apply. However, many of you may find that a combination of theoretical perspectives is most helpful for you to investigate your project. For example, maybe the group counseling program for which you are evaluating client outcomes draws from both motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy. In order to understand the change happening in the client population, you would need to know each theory separately as well as how they work in tandem with one another. Because theoretical explanations and even the definitions of concepts are debated by scientists, it may be helpful to find a specific social scientist or group of scientists whose perspective on the topic you find matches with your understanding of the topic. Of course, it is also perfectly acceptable to develop your own theoretical framework, though you should be able to articulate how your framework fills a gap within the literature.

Much like paradigm, theory plays a supporting role for the conceptualization of your research project. Recall the ice float from Figure 5.1. Theoretical explanations support the design and methods you use to answer your research question. In projects that lack a theoretical framework, you may see the biases and errors in reasoning that we discussed in Chapter 1 that get in the way of good social science. That’s because theories mark which concepts are important, provide a framework for understanding them, and measure their interrelationships. If research is missing this foundation, it may instead operate on informal observation, messages from authority, and other forms of unsystematic and unscientific thinking we reviewed in Chapter 1.

Theory-informed inquiry is incredibly helpful for identifying key concepts and how to measure them in your research project, but there is a risk in aligning research too closely with theory. The theory-ladenness of facts and observations produced by social science research means that we may be making our ideas real through research. This is a potential source of confirmation bias in social science. Moreover, as Tan (2016) [4] demonstrates, social science often proceeds by adopting as true the perspective of Western and Global North countries, and cross-cultural research is often when ethnocentric and biased ideas are most visible . In her example, a researcher from the West studying teacher-centric classrooms in China that rely partially on rote memorization may view them as less advanced than student-centered classrooms developed in a Western country simply because of Western philosophical assumptions about the importance of individualism and self-determination. Developing a clear theoretical framework is a way to guard against biased research, and it will establish a firm foundation on which you will develop the design and methods for your study.

Key Takeaways

- Just as empirical evidence is important for conceptualizing a research project, so too are the key concepts and relationships identified by social work theory.

- Using theory your theory textbook will provide you with a sense of the broad theoretical perspectives in social work that might be relevant to your project.

- Try to find small-t theories that are more specific to your topic area and relevant to your working question.

TRACK 1 (IF YOU ARE CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

In Chapter 2, you developed a concept map for your proposal.

- Take a moment to revisit your concept map now as your theoretical framework is taking shape. Make any updates to the key concepts and relationships in your concept map.

If you need a refresher, we have embedded a short how-to video from the University of Guelph Library (CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0) that we also used in Chapter 2.

TRACK 2 (IF YOU AREN’T CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

You are interested in researching bullying among school-aged children, and how this impacts students’ academic success.

- Find two theoretical frameworks that have been used in published articles on this topic. Identify similarities and differences between the frameworks.

5.6 Designing your project using theory and paradigm

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Apply the assumptions of each paradigm to your project

- Summarize what aspects of your project stem from positivist, constructivist, or critical assumptions

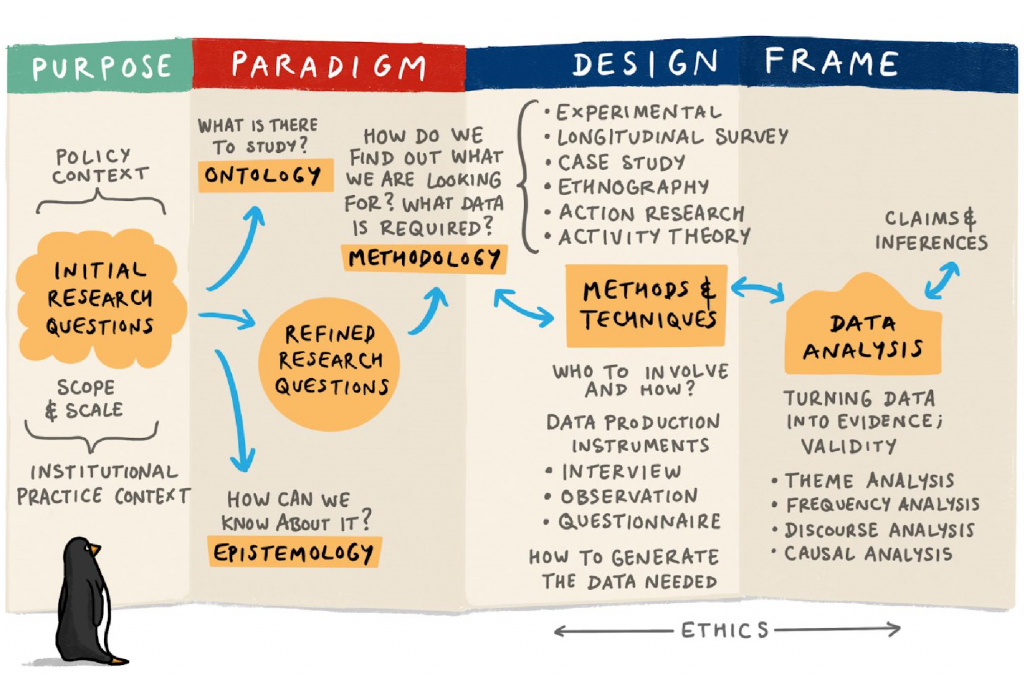

In the previous sections, we reviewed the major paradigms and theories in social work research. In this section, we will provide an example of how to apply theory and paradigm in research. This process is depicted in Figure 5.2 below with some quick summary questions for each stage. Some questions in the figure below have example answers like designs (i.e., experimental, survey) and data analysis approaches (i.e., discourse analysis). These examples are arbitrary. There are a lot of options that are not listed. So, don’t feel like you have to memorize them or use them in your study.

This diagram (taken from an archived Open University (UK) course entitled E89 - Educational Inquiry ) shows one way to visualize the research design process. While research is far from linear, in general, this is how research projects progress sequentially. Researchers begin with a working question, and through engaging with the literature, develop and refine those questions into research questions (a process we will finalize in Chapter 9). But in order to get to the part where you gather your sample, measure your participants, and analyze your data, you need to start with paradigm. Based on your work in section 5.3, you should have a sense of which paradigm or paradigms are best suited to answering your question. The approach taken will often reflect the nature of the research question; the kind of data it is possible to collect; and work previously done in the area under consideration. When evaluating paradigm and theory, it is important to look at what other authors have done previously and the framework used by studies that are similar to the one you are thinking of conducting.

Once you situate your project in a research paradigm, it becomes possible to start making concrete choices about methods. Depending on the project, this will involve choices about things like:

- What is my final research question?

- What are the key variables and concepts under investigation, and how will I measure them?

- How do I find a representative sample of people who experience the topic I’m studying?

- What design is most appropriate for my research question?

- How will I collect and analyze data?

- How do I determine whether my results describe real patterns in the world or are the result of bias or error?

The data collection phase can begin once these decisions are made. It can be very tempting to start collecting data as soon as possible in the research process as this gives a sense of progress. However, it is usually worth getting things exactly right before collecting data as an error found in your approach further down the line can be harder to correct or recalibrate around.

Designing a study using paradigm and theory: An example

Paradigm and theory have the potential to turn some people off since there is a lot of abstract terminology and thinking about real-world social work practice contexts. In this section, I’ll use an example from my own research, and I hope it will illustrate a few things. First, it will show that paradigms are really just philosophical statements about things you already understand and think about normally. It will also show that no project neatly sits in one paradigm and that a social work researcher should use whichever paradigm or combination of paradigms suit their question the best. Finally, I hope it is one example of how to be a pragmatist and strategically use the strengths of different theories and paradigms to answering a research question. We will pick up the discussion of mixed methods in the next chapter.

Thinking as an expert: Positivism

In my undergraduate research methods class, I used an open textbook much like this one and wanted to study whether it improved student learning. You can read a copy of the article we wrote on based on our study . We’ll learn more about the specifics of experiments and evaluation research in Chapter 13, but you know enough to understand what evaluating an intervention might look like. My first thought was to conduct an experiment, which placed me firmly within the positivist or “expert” paradigm.

Experiments focus on isolating the relationship between cause and effect. For my study, this meant studying an open textbook (the cause, or intervention) and final grades (the effect, or outcome). Notice that my position as “expert” lets me assume many things in this process. First, it assumes that I can distill the many dimensions of student learning into one number—the final grade. Second, as the “expert,” I’ve determined what the intervention is: indeed, I created the book I was studying, and applied a theory from experts in the field that explains how and why it should impact student learning.

Theory is part of applying all paradigms, but I’ll discuss its impact within positivism first. Theories grounded in positivism help explain why one thing causes another. More specifically, these theories isolate a causal relationship between two (or more) concepts while holding constant the effects of other variables that might confound the relationship between the key variables. That is why experimental design is so common in positivist research. The researcher isolates the environment from anything that might impact or bias the cause and effect relationship they want to investigate.

But in order for one thing to lead to change in something else, there must be some logical, rational reason why it would do so. In open education, there are a few hypotheses (though no full-fledged theories) on why students might perform better using open textbooks. The most common is the access hypothesis , which states that students who cannot afford expensive textbooks or wouldn’t buy them anyway can access open textbooks because they are free, which will improve their grades. It’s important to note that I held this theory prior to starting the experiment, as in positivist research you spell out your hypotheses in advance and design an experiment to support or refute that hypothesis.

Notice that the hypothesis here applies not only to the people in my experiment, but to any student in higher education. Positivism seeks generalizable truth, or what is true for everyone. The results of my study should provide evidence that anyone who uses an open textbook would achieve similar outcomes. Of course, there were a number of limitations as it was difficult to tightly control the study. I could not randomly assign students or prevent them from sharing resources with one another, for example. So, while this study had many positivist elements, it was far from a perfect positivist study because I was forced to adapt to the pragmatic limitations of my research context (e.g., I cannot randomly assign students to classes) that made it difficult to establish an objective, generalizable truth.

Thinking like an empathizer: constructivism

One of the things that did not sit right with me about the study was the reliance on final grades to signify everything that was going on with students. I added another quantitative measure that measured research knowledge, but this was still too simplistic. I wanted to understand how students used the book and what they thought about it. I could create survey questions that ask about these things, but to get at the subjective truths here, I thought it best to use focus groups in which students would talk to one another with a researcher moderating the discussion and guiding it using predetermined questions. You will learn more about focus groups in Chapter 18.

Researchers spoke with small groups of students during the last class of the semester. They prompted people to talk about aspects of the textbook they liked and didn’t like, compare it to textbooks from other classes, describe how they used it, and so forth. It was this focus on understanding and subjective experience that brought us into the constructivist paradigm. Alongside other researchers, I created the focus group questions but encouraged researchers who moderated the focus groups to allow the conversation to flow organically.

We originally started out with the assumption, for which there is support in the literature, that students would be angry with the high-cost textbook that we used prior to the free one, and this cost shock might play a role in students’ negative attitudes about research. But unlike the hypotheses in positivism, these are merely a place to start and are open to revision throughout the research process. This is because the researchers are not the experts, the participants are! Just like your clients are the experts on their lives, so were the students in my study. Our job as researchers was to create a group in which they would reveal their informed thoughts about the issue, coming to consensus around a few key themes.

When we initially analyzed the focus groups, we uncovered themes that seemed to fit the data. But the overall picture was murky. How were themes related to each other? And how could we distill these themes and relationships into something meaningful? We went back to the data again. We could do this because there isn’t one truth, as in positivism, but multiple truths and multiple ways of interpreting the data. When we looked again, we focused on some of the effects of having a textbook customized to the course. It was that customization process that helped make the language more approachable, engaging, and relevant to social work practice.

Ultimately, our data revealed differences in how students perceived a free textbook versus a free textbook that is customized to the class. When we went to interpret this finding, the remix hypothesis of open textbook was helpful in understanding that relationship. It states that the more faculty incorporate editing and creating into the course, the better student learning will be. Our study helped flesh out that theory by discussing the customization process and how students made sense of a customized resource.

In this way, theoretical analysis operates differently in constructivist research. While positivist research tests existing theories, constructivist research creates theories based on the stories of research participants. However, it is difficult to say if this theory was totally emergent in the dataset or if my prior knowledge of the remix hypothesis influenced my thinking about the data. Constructivist researchers are encouraged to put a box around their previous experiences and beliefs, acknowledging them, but trying to approach the data with fresh eyes. Constructivists know that this is never perfectly possible, though, as we are always influenced by our previous experiences when interpreting data and conducting scientific research projects.

Thinking like an activist: Critical

Although adding focus groups helped ease my concern about reducing student learning down to just final grades by providing a more rich set of conversations to analyze. However, my role as researcher and “expert” was still an important part of the analysis. As someone who has been out of school for a while, and indeed has taught this course for years, I have lost touch with what it is like to be a student taking research methods for the first time. How could I accurately interpret or understand what students were saying? Perhaps I would overlook things that reflected poorly on my teaching or my book. I brought other faculty researchers on board to help me analyze the data, but this still didn’t feel like enough.

By luck, an undergraduate student approached me about wanting to work together on a research project. I asked her if she would like to collaborate on evaluating the textbook with me. Over the next year, she assisted me with conceptualizing the project, creating research questions, as well as conducting and analyzing the focus groups. Not only would she provide an “insider” perspective on coding the data, steeped in her lived experience as a student, but she would serve as a check on my power through the process.

Including people from the group you are measuring as part of your research team is a common component of critical research. Ultimately, critical theorists would find my study to be inadequate in many ways. I still developed the research question, created the intervention, and wrote up the results for publication, which privileges my voice and role as “expert.” Instead, critical theorists would emphasize the role of students (community members) in identifying research questions, choosing the best intervention to used, and so forth. But collaborating with students as part of a research team did address some of the power imbalances in the research process.

Critical research projects also aim to have an impact on the people and systems involved in research. No students or researchers had profound personal realizations as a result of my study, nor did it lessen the impact of oppressive structures in society. I can claim some small victory that my department switched to using my textbook after the study was complete (changing a system), though this was likely the result of factors other than the study (my advocacy for open textbooks).

Social work research is almost always designed to create change for people or systems. To that end, every social work project is at least somewhat critical. However, the additional steps of conducting research with people rather than on people reveal a depth to the critical paradigm. By bringing students on board the research team, study had student perspectives represented in conceptualization, data collection, and analysis. That said, there was much to critique about this study from a critical perspective. I retained a lot of the power in the research process, and students did not have the ability to determine the research question or purpose of the project. For example, students might likely have said that textbook costs and the quality of their research methods textbook were less important than student debt, racism, or other potential issues experienced by students in my class. Instead of a ground-up research process based in community engagement, my research included some important participation by students on project created and led by faculty.

Designing research is an iterative process