Movie Reviews

Tv/streaming, collections, great movies, chaz's journal, contributors.

Now streaming on:

"Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted , shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction." –Thirteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution

When the 13 th amendment was ratified in 1865, its drafters left themselves a large, very exploitable loophole in the guise of an easily missed clause in its definition. That clause, which converts slavery from a legal business model to an equally legal method of punishment for criminals, is the subject of the Netflix documentary “13th.” Premiering tonight at the New York Film Festival, “13th” is the first documentary to open the festival in its 54 year history. Director Ava DuVernay ’s takes an unflinching, well-informed and thoroughly researched look at the American system of incarceration, specifically how the prison industrial complex affects people of color. Her analysis could not be more timely nor more infuriating. The film builds its case piece by shattering piece, inspiring levels of shock and outrage that stun the viewer, leaving one shaken and disturbed before closing out on a visual note of hope designed to keep us on the hook as advocates for change.

“13th” begins with an alarming statistic: One out of four African-American males will serve prison time at one point or another in their lives. Our journey begins from there, with a slew of familiar and occasionally surprising talking heads filling the frame and providing information. DuVernay not only interviews liberal scholars and activists for the cause like Angela Davis , Henry Louis Gates and Van Jones, she also devotes screen time to conservatives such as Newt Gingrich and Grover Norquist. Each interviewee is shot in a location that evokes an industrial setting, which visually supports the theme of prison as a factory churning out the free labor that the 13th Amendment supposedly dismantled when it abolished slavery.

We’re told that, after the Civil War, the economy of the former Confederate States of America was decimated. Their primary source of income, slaves, were no longer obligated to line Southerners’ pockets with their blood, sweat and tears. Unless, of course, they were criminals. “Except as punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted” reads the loophole in the law. In the first iteration of a “Southern strategy,” hundreds of newly emancipated slaves were re-enlisted into free, legal servitude courtesy of minor or trumped-up charges. The duly convicted part may have been questionable, but by no means did it need to be justifiably proven.

So begins a cycle that DuVernay examines in each of its evolving iterations; when one method of subservience-based terror falls out of favor, another takes its place. The list feels endless and includes lynching, Jim Crow, Nixon’s presidential campaign, Reagan’s War on Drugs, Bill Clinton ’s Three Strikes and mandatory sentencing laws and the current cash-for-prisoners model that generates millions for private bail and incarceration firms.

That last item is a major point of discussion in “13th”, with an onscreen graphic keeping tally of the number of prisoners in the system as the years pass. Starting in the 1940’s, the curve of the prisoner count graph begins rising slowly though steeply. A meteoric rise began during the Civil Rights movement and continued into the current day. As this statistic rises, so does the level of decimation of families of color. The stronger the protest for rights, the harder the system fights back against it with means of incarceration. Profit becomes the major by-product of this cycle, with an organization called ALEC providing a scary, sinister influence on building laws that make its corporate members richer.

Several times throughout “13th” there is a shock cut to the word CRIMINAL, which stands alone against a black background and is centered on the huge movie screen. It serves as a reminder that far too often, people of color are seen as simply that, regardless of who they are. Starting with D.W. Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation”, DuVernay traces the myth of the scary Black felon with supernatural levels of strength and deviant sexual potency, a myth designed to terrify the majority into believing that only White people were truly human and deserving of proper treatment. This dehumanization allowed for the acceptance of laws and ideas that had more than a hint of bias. We see higher sentences given for crack vs. cocaine possession and plea bargains accepted by innocent people too terrified to go to trial. We also learn that a troubling percentage of people remain in jail because they’re too poor to post their own bail. And regardless of your color, if you’re a felon, you can no longer vote to change the laws that may have unfairly prosecuted you. You lose a primary right all Americans have.

“13th” covers a lot of ground as it works its way to the current days of Black Lives Matter and the terrifying videos of the endless list of African-Americans being shot by police or folks who supposedly “stood their ground.” On her journey to this point, DuVernay doesn’t let either political party off the hook, nor does she ignore the fact that many people of color bought into the “law and order” philosophies that led to the current situation. We see Hillary Clinton talking about “super-predators” and Donald Trump ’s full-page ad advocating the death penalty for the Central Park Five (who, as a reminder, were all innocent). We also see people like African-American congressman Charlie Rangel, who originally was on board with the tough on crime laws President Clinton signed into law.

By the time we get to the montage of the deaths of Philando Castile, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner and others (not to mention the huge, screen-covering graphic of names of African-Americans shot by law enforcement), “13th” has already proven its thesis on how such events can not only occur, but can also seem sadly like “business as usual.” It’s a devastating finale to the film, one that follows an onscreen discussion about whether or not the destruction of Black bodies should be run ad nauseum on cable news programs. DuVernay opts to show the footage, with an onscreen disclaimer that it’s being shown with permission by the families of the victims, something she did not need to seek but did so out of respect.

Between the lines, “13th” boldly asks the question if African-Americans were actually ever truly “free” in this country. We are freer, as this generation has it a lot easier than our ancestors who were enslaved, but the question of being as completely “free” as our White compatriots hangs in the air. If not, will the day come when all things will be equal? The final takeaway of “13th” is that change must come not from politicians, but from the hearts and minds of the American people.

Despite the heavy subject matter, DuVernay ends the film with joyful scenes of children and adults of color enjoying themselves in a variety of activities. It reminds us, as she said in her Q&A with NYFF director Kent Jones , that “Black trauma is not our entire lives. There is also Black joy.” That inspiring message, and all the important, educational information provided by this excellent documentary, make “13th” a must-see.

"13th" is currently streaming on Netflix.

Odie Henderson

Odie "Odienator" Henderson has spent over 33 years working in Information Technology. He runs the blogs Big Media Vandalism and Tales of Odienary Madness. Read his answers to our Movie Love Questionnaire here .

Now playing

Don't Tell Mom the Babysitter's Dead

Peyton robinson.

Brian Tallerico

Steve! (Martin): A Documentary in Two Pieces

Girls State

Riddle of Fire

Robert daniels, film credits.

13th (2016)

100 minutes

- Ava DuVernay

Latest blog posts

Sonic the Hedgehog Franchise Moves to Streaming with Entertaining Knuckles

San Francisco Silent Film Festival Highlights Unearthed Treasures of Film History

Ebertfest Film Festival Over the Years

The 2024 Chicago Palestine Film Festival Highlights

Themes in Ava DuVernay’s “13th” Essay (Movie Review)

Although slavery was abolished in the United States many years ago, the American society has indicators of a modern form of hidden slavery that was legalized according to the Thirteenth Amendment. This controversial topic is discussed in 13th , a documentary that was directed by Ava DuVernay and released by Netflix in 2016 (Netflix, 2016). The other important themes accentuated in the film include mass incarceration, racism, social bias, the gender issue, the impact on the environment, the social impact, the ineffectiveness of a prison system, and education. The purpose of this paper is to analyze 13th in the context of addressing the listed themes and discuss its relevance for being used in educational settings.

In her documentary, DuVernay presents the issue of mass incarceration of black male persons as an American variant of modern slavery. In this context, the following topics should be discussed in their connection to each other: mass imprisoning, racism, the gender issue, and social bias. According to DuVernay’s message, American society is inclined to refer to slavery for profit, and mass incarceration of African American males contributes to this economic goal (Netflix, 2016).

Furthermore, this tradition has its origins in Jim Crow laws and provocative positions of Richard Nixon, Bill Clinton, Hillary Clinton, and Donald Trump discussed in the film. The problem is that racial and social prejudice is reflected in the U.S. Constitution in the form of the Thirteenth Amendment that allows choosing some kind of slavery for punishment.

It seems to be typical of American society to shift the visions used in the 18th-19th centuries regarding African American people that are closely based on racism and social bias to the 20th-21st centuries. In addition, there is also a gender issue as African American males represent a significant portion of the imprisoned population in the United States. Thus, more than 35 percents of the imprisoned population are made up by African Americans (Netflix, 2016).

According to the behaviorism-related theory by John B. Watson, children’s views, reactions, and actions are formed by their environments and parents’ ideas. The similar idea is proposed by Albert Bandura and his concept of social learning (Shaffer & Kipp, 2014). From this perspective, DuVernay’s documentary represents how the ideas about the possibility of slavery and racism are shared between Americans from one generation to another. As a result, there is a question about what can be changed in society and education, as well as public’s perceptions of people of color, in order to alter this tendency.

Other issues that need to be discussed with reference to the film include the impact of mass incarceration on the environment and adverse effects of the environment on this phenomenon, as well as social impacts. The problem is that the number of prisoners tends to increase each year, as it is stated in the documentary. Thus, in the 1970s, almost 200,000 people were in US prisons, and today this number is more than 2 million people (Netflix, 2016).

There can be several causes of this situation, including the environmental factor. According to Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory, an individual develops under the impact of different environmental impacts, including the family, school, friends, neighbors, mass media, and community (Shaffer & Kipp, 2014). As a result, these subjects influence what choices will be made by persons when they are adults. Under the community’s impact, African American males can choose a criminal path, and under the media’s impact, white people can regard black males as potential criminals.

One more important issue to discuss in the context of 13th is the ineffectiveness of a prison system in the United States. Thus, prisons in the country are overcrowded, minorities who represent more than 60% of the overall imprisoned population are discriminated and usually abused, and black males are used as the extremely cheap labor force (Netflix, 2016). As a result, prisoners just work to address the needs of corporations to generate more profits without opportunities to develop their potential and transform to become the part of American society in the future.

From this perspective, prison does not work as a correctional facility, and the problem is that these people used as slaves can become even more traumatized because of their experience in prison. Referring to DuVernay’s message in the documentary, it is possible to state that the overall prison system in the United States is developed to address economic and political needs and interests. Thus, its social correctional effect seems to be limited (Stierman, 2017).

The situation of overcrowding in prisons of the United States cannot contribute to helping prisoners, African American males or representatives of other gender and race, to develop their personal potential and realize an effective social role.

It is also important to discuss the ideas presented in DuVernay’s 13th with the focus on modern education in the United States. Taking into account B. F. Skinner’s ideas regarding reinforcers and punishers to form people’s behavior, it is possible to state that the fear of being imprisoned can work as a punisher for preventing criminal actions. However, the problem is that, according to DuVernay, this aspect does not contribute to reducing the number of prisoners (Lopez-Littleton & Woodley, 2018). There are other sources of mass incarceration, and they are closely associated with racial and economic factors. Therefore, today young persons often do not understand what particular actions can lead to imprisoning, especially for people of color.

For a pre-service teacher, DuVernay’s 13th can provide a range of topics to think over while discussing the role of school and society in forming the personality. From this perspective, it is important to answer the questions about the potential impact of education on decreases in rates of crimes and on social stability in minorities’ communities. African Americans men are often arrested and incarcerated because they not only act like criminals, but they are also assumed to act like criminals. Therefore, a pre-service teacher should think over about the role of a class environment in forming this prejudice.

After watching 13th , it is possible to adapt some of the ideas presented in the film to discussing with high school students. Firstly, it is necessary to discuss this film while explaining the nature of the Thirteenth Amendment, as well as the Sixth Amendment that guarantees criminal defendants’ right to impartial jury among other rights . Secondly, it is important to analyze this film in the context of discussing the problem of racism in modern American society. It is important to demonstrate how hidden racism can become real while speaking about the prison system and criminal justice bias in the United States.

DuVernay’s 13th is the documentary that makes the viewer reconsider his or her vision of American society today in terms of the problem of mass incarceration. This film should be analyzed by educators in order to use some of its parts in their discussions of racism and slavery. Furthermore, the film can be recommended for high school students in order to discuss not only the phenomenon of modern slavery but also the impact of social prejudice and environments on individuals and their life path.

Lopez-Littleton, V., & Woodley, A. (2018). Movie review of 13th by Ava Duvernay: Administrative evil and the prison industrial complex. Public Integrity , 20 (4), 415-418.

Netflix. (2016). 13th . Web.

Shaffer, D. R., & Kipp, K. (2014). Developmental psychology: Childhood and adolescence (9th ed.). New York, NY: Cengage Learning.

Stierman, V. (2017). When the hidden injustices are brought to light: A review of 13th. Tapestries: Interwoven Voices of Local and Global Identities , 6 (1), 1-3.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 31). Themes in Ava DuVernay’s "13th". https://ivypanda.com/essays/ava-duvernays-13th/

"Themes in Ava DuVernay’s "13th"." IvyPanda , 31 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/ava-duvernays-13th/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Themes in Ava DuVernay’s "13th"'. 31 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Themes in Ava DuVernay’s "13th"." October 31, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ava-duvernays-13th/.

1. IvyPanda . "Themes in Ava DuVernay’s "13th"." October 31, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ava-duvernays-13th/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Themes in Ava DuVernay’s "13th"." October 31, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ava-duvernays-13th/.

- "The 13th" Documentary Directed by Ava DuVernay

- Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution Review

- The 13th Documentary Film on Police Brutality

- “Ava’s Man” by Rick Bragg

- Dialysis With PVC or AVA in End-Stage Renal Failure

- The Ex Machina Film by Alex Garland

- Should the Draft System Be Re-Introduced?

- Target Corporation's Finances and Market in 2011-15

- Women’s Liberation Movement in the Arts

- Ballot Initiative in the 13th Amendment

- "The Civil War" Documentary: Strengths and Weaknesses

- "Japan: Memoirs of a Secret Empire" Documentary

- Nuclear Weapons in the "Iranium" Documentary

- Senses in "Manakamana" Film by Spray and Velez

- "The People's Republic of Capitalism" Documentary

Advertisement

Supported by

Review: ‘13TH,’ the Journey From Shackles to Prison Bars

- Share full article

By Manohla Dargis

- Sept. 29, 2016

Powerful, infuriating and at times overwhelming, Ava DuVernay’s documentary “13TH” will get your blood boiling and tear ducts leaking. It shakes you up, but it also challenges your ideas about the intersection of race, justice and mass incarceration in the United States, subject matter that could not sound less cinematic. Yet Ms. DuVernay — best known for “Selma,” and a filmmaker whose art has become increasingly inseparable from her activism — has made a movie that’s as timely as the latest Black Lives Matter protest and the approaching presidential election.

The movie hinges on the 13th Amendment, as the title indicates, in ways that may be surprising, though less so for those familiar with Michelle Alexander’s 2010 best seller, “ The New Jim Crow : Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness.” Ratified in 1865, the amendment states in full: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” As Ms. Alexander underscores, slavery was abolished for everyone except criminals. (“13TH” opens the New York Film Festival on Friday; it will be in theaters and on Netflix beginning on Oct. 7 .)

In her book, Ms. Alexander (the most charismatic of the movie’s interviewees) argues that mass incarceration exists on a continuum with slavery and Jim Crow. As one of “the three major racialized systems of control adopted in the United States to date,” it ensures “the subordinate status of a group defined largely by race.” Under the old Jim Crow, state laws instituted different rules for blacks and whites, segregating them under the doctrine of separate but equal . Now, with the United States having 25 percent of the world’s prisoners, a disproportionate number of whom are black, mass incarceration has become “metaphorically, the new Jim Crow.”

Written by Ms. DuVernay and Spencer Averick , “13TH” picks up Ms. Alexander’s baton and sprints through the history of American race and incarceration with seamless economy. (Mr. Averick also edited the movie.) In its first 30 minutes, the documentary touches on chattel slavery; D. W. Griffith’s film “The Birth of a Nation”; Emmett Till ; the civil rights movement; the Civil Rights Act of 1964; Richard M. Nixon; and Ronald Reagan’s declaration of the war on drugs. By the time her movie ends, Ms. DuVernay has delivered a stirring treatise on the prison industrial complex through a nexus of racism, capitalism, policies and politics. It sounds exhausting, but it’s electrifying.

Speed is one reason — you’re racing through history witness by witness, ghastly statistic by statistic — but you’re also charged up by how the movie’s voices rise and converge. It’s like being in a room with the smartest people around, all intent on rocking your world. Ms. DuVernay is working within a familiar documentary idiom that weaves original, handsomely shot talking-head interviews with well-researched, occasionally surprising and gravely disturbing archival material. All these sources, in turn, have been shaped into discrete sections that are introduced with music and animation. Every so often, the animation underscores an interviewee’s point, as in one sequence in which the word “freedom” morphs into flying birds and then the Stars and Stripes and then a slave ship.

With few exceptions, the movie’s voices — including most of its several dozen interviewees — speak in concert. Some (like a galvanizing Angela Davis) are more effective and persuasive than others; at least one — Newt Gingrich, speaking startling truth to power — is a jaw-dropper. Even with its surprise guests, the movie isn’t especially dialectical; it also isn’t mainstream journalism. Ms. DuVernay presents both sides of the story, as it were (racism versus civil rights). Yet she doesn’t call on, say, politicians who have voted against civil rights measures for their thoughts on the history of race in the United States. She begins from the premise that white supremacy has already had its say for centuries.

Ms. Alexander has been criticized for oversimplifying the origins of mass incarceration in “The New Jim Crow.” This may account for why Ms. DuVernay, in perhaps a bid to pre-empt similar criticism, does include a few divergent voices, including the conservative lobbyist Grover Norquist , who frankly comes off as an exemplar of blinkered power and racial myopia. He pops up in a section on the rise off mass incarceration during the 1980s that’s tied to crack cocaine and the racial gap in arrests and sentencing. Mr. Norquist puts the onus for this disparity on politicians (calling out United States Representative Charles B. Rangel, another interviewee), stating that it had nothing to do with — as he puts it — “mean white people.”

The documentary might have benefited from more articulate jaggedly discordant voices than Mr. Norquist’s to enrich the dialogue and as a reminder of the other views on race, history and the criminal justice system, including those in the mainstream. One popular textbook, “The American System of Criminal Justice,” states that the 13th Amendment “had little impact on criminal justice.” And a booklet on the Constitution, “ Know Your Rights ,” available through the Justice Department, reads: “The 13th Amendment protects every person in America — all races and creeds, citizens and noncitizens, children and adults — from the bondage of slavery. It is unconstitutional for slavery to exist in any form or by any name.”

Ms. DuVernay forcefully and sorrowfully challenges that confident assertion, tracing the history of systems of racial control from the years after the abolition of slavery all the way to George Zimmerman’s speaking to a police dispatcher about the 17-year-old Trayvon Martin. “He’s got his hand in his waistband,” we hear Mr. Zimmerman say shortly before fatally shooting Mr. Martin. “And he’s a black male.” When this documentary reaches its culmination, which features graphic videos of one after another black man being shot by police, Ms. DuVernay’s rigorously controlled deconstruction of crime, punishment and race in the United States has become a piercing, keening cry.

Ms. DuVernay isn’t the only American director to take on race and the prison industrial complex (Eugene Jarecki’s “ The House I Live In ” charts adjacent terrain), but hers is a powerful cinematic call to conscience, partly because of how she lays bare the soul of our country. Because, as she sifts through American history, you grasp the larger implications of her argument: The United States did not just criminalize a select group of black people. It criminalized black people as a whole, a process that, in addition to destroying untold lives, effectively transferred the guilt for slavery from the people who perpetuated it to the very people who suffered through it.

“13TH” is not rated. Running time: 1 hour 40 minutes.

Explore More in TV and Movies

Not sure what to watch next we can help..

As “Sex and the City” became more widely available on Netflix, younger viewers have watched it with a critical eye . But its longtime millennial and Gen X fans can’t quit.

Hoa Xuande had only one Hollywood credit when he was chosen to lead “The Sympathizer,” the starry HBO adaptation of a prize-winning novel. He needed all the encouragement he could get .

Even before his new film “Civil War” was released, the writer-director Alex Garland faced controversy over his vision of a divided America with Texas and California as allies.

Theda Hammel’s directorial debut, “Stress Positions,” a comedy about millennials weathering the early days of the pandemic , will ask audiences to return to a time that many people would rather forget.

If you are overwhelmed by the endless options, don’t despair — we put together the best offerings on Netflix , Max , Disney+ , Amazon Prime and Hulu to make choosing your next binge a little easier.

Sign up for our Watching newsletter to get recommendations on the best films and TV shows to stream and watch, delivered to your inbox.

13th: Documentary Review and Analysis of Themes

Analysis of themes.

The documentary 13th is a gripping account of how the law that abolished slavery created an exploitable loophole for this inhumane behavior to continue, albeit subtly, under the guise of legality. The 13th Amendment of the US Constitution states, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, nor any place subject to their jurisdiction.” Under the provision that slavery would be used as a form of punishment for crime, thralldom evolved from a business model to a legal way of sanctioning criminals. This section discusses the two themes (i) mass incarceration as replacement of slavery and (ii) how corporate interests shape prison populations, as portrayed in the documentary 13th .

Mass Incarceration as Replacement of Slavery

Immediately after the abolishment of slavery in the US, racist legislation and practices were put in place as systems of racial control and profiteering. When the Civil War ended, the former Confederate States were economically crippled because their main source of wealth, slaves, were not available anymore to be used for moneymaking. However, the 13th Amendment had a provision that could reintroduce slavery legally, and this loophole was exploited to the maximum. In the South, minor offenses were criminalized, and the majority of freed slaves were arrested on trumped-up charges. Given that the victims of this conniving strategy were unemployed, they could not pay the associated fines, and thus they became legal slaves under the new law.

Convict leasing created the need for free labor because private entities, such as corporations and plantations, would contract services of prisoners without paying anything apart from feeding, clothing, and housing the workers. The institutionalization of slavery under the 13th Amendment was a motivation for the criminalization of more behaviors. The Jim Crow era followed closely, and it created more legal grounds for the incarceration of minority groups. This approach to mass incarceration has evolved with time, and currently, it focuses on the war on drugs. Ultimately, slavery returned to the US, but this time, it was legal and thus last.

Corporate Interests Shape Prison Populations

Corporate interests as key determinants of prison populations infiltrated the system under the convict leasing provision. As mentioned earlier, private entities, including plantations and corporations, would contract services of prisoners at minimal costs. Given that the former Confederate States of America had to rebuild the decimated economy after the Civil War, the demand for free labor from prisoners was high, hence the need to imprison more freed slaves. Besides, after the abolishment of slavery, black people have continuously fought the system that dehumanizes them through legal provisions. However, the more they fight, the more the system responds violently through mass incarcerations.

Therefore, the demand to have private-run prisons was created out of this scenario. Such correctional institutions are run with the aim of profiteering, and thus the involved parties formed the controversial American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC). According to the documentary, corporations sponsor this body to convince legislators about the need for having laws that create more prisoners. Currently, over 25 percent of US legislators have ties to ALEC. Some legislators have even introduced bills with ALEC branding to be passed as laws. As such, corporations under the guise of ALEC determine the number of people that should be imprisoned by influencing policymaking.

Analysis of Topics

From the many topics that have been studied in class, two of them, sentencing offenders and the war on drugs, are related to the contents of the documentary, as discussed in this section.

War on Drugs

According to the class notes, the war on drugs started in 1784 under the guidance of Dr. Benjamin Rush, and it continues in modern-day America. However, some of the approaches that have been used to fight drug abuse and usage intersect with the contents of the documentary 13th . The laws that are applied to criminalize the use of drugs meant that blacks would be affected disproportionately. According to the class notes, the war on drugs is the main source of racial disproportionality, along with the belief that incarceration is the correct penalty for drug offenses. Similarly, the 13th Amendment ensured that blacks, as freed slaves, would be highly affected by the provision to imprison people for minor offenses. Additionally, in the documentary, blacks are likely to be incarcerated because they are segregated.

Without proper means and systems of creating wealth, they are bound to break the rules and commit punishable offenses. In other words, the law is punitive, and it does not focus on creating an environment for blacks to thrive. Similarly, in the war against drugs, President Reagan welcomed an era of punitive drug law enforcement. While the federal budget for law enforcement increased significantly, that of drug treatment and research decreased. Therefore, drug offenders are imprisoned without receiving proper healthcare help to address the problem. Once freed, such offenders are likely to be rearrested for the same offenses, thus making it a vicious cycle that punishes blacks just as the 13th Amendment legalized slavery.

Sentencing Offenders

Under the discrimination continuum studied in class, policies contribute significantly to different forms of discrimination. Additionally, under direct discrimination, the severity of the sentence for a crime is based on race, ethnicity, or gender. In the documentary, the 13th Amendment discriminated against blacks albeit subtly. For instance, people convicted of minor offenses without the capacity to pay the associated fines would be imprisoned and work as slaves. Freed slaves were highly likely to commit minor offenses, and they did not have the means to pay for the fines. In addition, under the Jim Crow legislation, blacks were segregated, and they would be jailed for crossing certain lines. The laws that were being used during this period were discriminatory in nature, and thus blacks were affected disproportionately.

According to the class notes, blacks are more likely to receive harsher sentences as compared to whites for drug offenses, which is a form of subtle discrimination. In other words, any form of discrimination happens when justice is not applied evenly, which has been the case of sentencing offenders in the United States. According to the documentary, the loophole in the13th Amendment was created deliberately to discriminate against freed slaves. In the documentary, President Clinton is shown taking a hard stance on the war against drugs by signing into law harsh penalties on such crimes. This approach to the war against drugs is similar to that applied by President Reagan as studied in class. As such, the topics studied in the class carry almost the same themes as those highlighted in the documentary.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2021, July 23). 13th: Documentary Review and Analysis of Themes. https://studycorgi.com/13th-documentary-analysis/

"13th: Documentary Review and Analysis of Themes." StudyCorgi , 23 July 2021, studycorgi.com/13th-documentary-analysis/.

StudyCorgi . (2021) '13th: Documentary Review and Analysis of Themes'. 23 July.

1. StudyCorgi . "13th: Documentary Review and Analysis of Themes." July 23, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/13th-documentary-analysis/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "13th: Documentary Review and Analysis of Themes." July 23, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/13th-documentary-analysis/.

StudyCorgi . 2021. "13th: Documentary Review and Analysis of Themes." July 23, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/13th-documentary-analysis/.

This paper, “13th: Documentary Review and Analysis of Themes”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: March 19, 2022 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

13th review – fiercely intelligent prison documentary

Ava DuVernay’s lucid study of the links between slavery and the US penal system is packed with ideas and information

T here is something bracing, even exciting, about the intellectual rigour that Ava DuVernay brings to this documentary about the prison system and the economic forces behind racism in America. The film takes its title from the 13th amendment, which outlawed slavery but left a significant loophole. This clause, which allowed that involuntary servitude could be used as a punishment for crime, was exploited immediately in the aftermath of the civil war and, DuVernay argues, continues to be abused to this day.

There is an understandable anger to this film-making, but DuVernay, who is best known as the director of Selma , but cut her teeth as a documentarian, never allows it to cloud the clarity of her message. It’s an approach that reminded me of the fierce intelligence of Charles Ferguson’s No End in Sight and Inside Job . Leaning on eloquent talking-head interviews and well-sourced archive material, she draws a defined through-line from the abolition of slavery, through the chain gang labour that replaced it, through segregation and “the mythology of black criminality”, to the war on crime and the war on drugs to the rise in mass incarceration and the big business of prisons. The words are so piercing and acute that we hardly need the stirring score that swirls in the background. The ever-present music is the one poorly judged element of the film. It clutters up a picture that is already densely packed with ideas and information.

More effective is the use of text: salient facts and figures are branded across the frame, searing them into our memory. And there is some memorable information imparted. That the US has less than 5% of the world’s population and almost 25% of the world’s prisoners is something that shouldn’t be forgotten.

- Documentary films

- The Observer

- Ava DuVernay

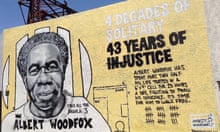

Albert Woodfox: ‘I choose to use my anger as a means for changing things’

Obama administration urges states to curb use of solitary confinement

Before solitary: a young man's journey in the US prison system – video

Angela Davis: ‘There is an unbroken line of police violence in the US that takes us all the way back to the days of slavery’

I was alone in a room for three years. Solitary confinement is torture – video

What is solitary confinement?

Welcome to your virtual cell: could you survive solitary confinement?

Comments (…), most viewed.

New York Film Festival Review: ‘13TH’

Ava DuVernay's documentary on the era of mass incarceration opens the New York Film Festival on a note of spectacular truth.

By Owen Gleiberman

Owen Gleiberman

Chief Film Critic

- ‘Rebel Moon — Part Two: The Scargiver’ Review: An Even More Rote Story, but a Bigger and Better Battle 4 days ago

- ‘Abigail’ Review: A Remake of ‘Dracula’s Daughter’ Turns Into a Brutally Monotonous Genre Mashup 5 days ago

- Why I Wasn’t Scared by ‘Civil War’ 1 week ago

Ava DuVernay ’s “ 13TH ” is the first documentary ever to be selected as the opening-night film of The New York Film Festival. (It premieres at Lincoln Center on Sept. 30.) That lends a momentous aura to what is already, each year, a momentous event. In this case, the precedent feels spiritually right. Movies, as both a business and an entertainment form, are struggling to define themselves in the 21st century, but there’s no doubt that we’re in the high renaissance era of documentary. Each week, every day, in theaters and on VOD, on cable channels and networks and streaming services, you can see movies that dive into topical issues with the investigative fury we once expected from newspapers. You can see movies that conjure (as maybe only movies can) the ghosts and artifacts and living semiotics of history, and that hold you in their grip with a force and excitement that match that of any dramatic feature. “13TH” is a movie that does all those things at once. More than just another documentary, it’s a crucial and stirring document — of racism and injustice, of politics and the big-picture design of America — that, I think, will be watched and referenced for years to come.

DuVernay, the brilliant director of “Selma,” has made a film that possesses a piercing relevance in the age of Black Lives Matter and the unspeakable horror and tragedy of escalated police shootings. “13TH” looks at the current American state of “mass incarceration,” a phrase that has quickly grown numbing with repetition; DuVernay puts the (disturbing) feeling back into it. She takes off from an era in which our nation — as President Obama observes in the film’s opening moments — contains just 5% of the world’s population and 25% of its prisoners. DuVernay’s chronicle of this crisis is heartrending and enraging; if that’s all the movie did, it would be invaluable. Yet “13TH” also travels deep into history, connecting every link in the chain to reveal how we got here. The metaphor is intentional: DuVernay’s message is that the psychodynamics of slavery, and the economic logistics of it, have never gone away. Instead, they went underground, mutating into different forms (Reconstruction, Jim Crow, the “war on drugs”) as the decades rolled on.

Popular on Variety

That’s a bold thesis, one you might imagine will put certain audiences on the defensive. DuVernay, though, works with a slow, sure hand that never risks oversimplifying the past. On the contrary, she brings the psychological history of what has gone on in this country to life in a way that few mainstream investigations or (God help us) liberal message movies have done. When you watch “13TH,” you feel that you’re seeing an essential dimension of America with new vision. That’s what a cathartically clear-eyed work of documentary art can do.

DuVernay, of course, is far from the first social critic to observe that slavery, for all practical purposes, didn’t end in 1865. Yet she examines its legacy with freshly devastating insight. In recent years, “The Birth of a Nation,” the 1915 D.W. Griffith landmark that essentially invented feature filmmaking as we know it, has been treated as such a racist pariah of a movie that its very existence has, to a degree, been shunned. The film’s racism (more than racism; let’s call it what it was — an exhortation to terrorism and racist violence) is undeniable, a stain on our country and the DNA of its popular culture. Yet Griffith’s power as a filmmaker is relevant as well, and DuVernay explores the movie in all its contradictions. The African-American Studies scholar Jelani Cobb unpacks “The Birth of a Nation” with blistering eloquence, describing how Griffith, in his portrayal of the second coming of the Ku Klux Klan, invented the image of the burning cross, and how the film offered “a tremendously accurate prediction of how race would operate in the United States.” Yet where does the escalation of that oppression turn into the rise of prison culture?

“13TH” traces the connection back to the end of the Civil War, and — in a grand horrific irony — to the passage of the 13th Amendment itself, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” This meant that once the war was over, former slaves could be arrested on trivial charges like vagrancy and loitering and turned into prisoners, and just like that…they were slaves again. Hence the image of men singing spirituals on the chain gang: a kind of legalized slavery. The link to “The Birth of a Nation” is that Griffith, working with actors in blackface, took the image of the “black criminal” and turned it into a demonic mythology that undergirded the 20th century. The “black criminal” became a monster to be feared and repressed, resulting in a vicious cycle that continues to this day: the presumption of black guilt in crime, leading to conviction, leading to incarceration, leading to a de facto systemization of imprisonment that is really the ethos of slavery in disguise.

In “13TH,” this narrative of racial tyranny is told with a nimble cinematic power that awakens your senses even as it sickens your moral center. Yet the film doesn’t become revelatory until it reaches the Civil Rights era, a moment when a lot of people (i.e., white liberals) began to congratulate themselves for having finally confronted the great American race problem and taken the big steps to “solve” it. Even if you acknowledged that we still had miles to go, no one denied that the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act — and the slow prying apart of cultural barriers that had begun to take place in the ’60s — amounted to the stirrings of a revolution. What DuVernay homes in on is the calculated counterattack waged by the establishment.

We all know about the rise, within the Republican Party, of the Southern strategy, though DuVernay features an extraordinary audio recording of Lee Atwater articulating it that puts a chill in your bones. And we know about the cataclysm of the assassinations, from Malcolm to Martin to Fred Hampton — though Van Jones testifies, with furious insight, about how terrifyingly it damaged the black community to have an entire generation of leaders stripped away. But the leap of perception made by “13TH” is to demonstrate how the Civil Rights movement, in spelling the end of the Jim Crow era, caused the white power structure to ask: What can we put in its place? How can we continue to segregate? The answer was the “war on crime” and the “war on drugs.” They were born together in the Nixon era, and they were always code for “Let’s put them behind bars.” DuVernay plays astonishing recorded testimony from John Ehrlichman, the Assistant to the President for Domestic Affairs, in which he admits that the government created a crackdown that targeted left-wing dissidents…and black people. But always with the excuse of fighting the drug scourge. “Did we know we were lying about the drugs?” asks Ehrlichman. “Of course we did.”

The “war on drugs” is, of course, far more associated with President Reagan, who launched his version in 1982 (with Nancy shouting “Just say no!” like a cheerleader from the sidelines). Many people reflexively went along with it, precisely because defending serious drug use never seemed like a viable alternative position. What happened, though, was that a health issue got turned into a crime issue. And selectively, hypocritically so. Think about it: If you learned today that a family member, or friend, or work colleague was a heroin addict, would you react by calling the police and having that person arrested? That would seem insane — but that’s what we did as a culture to thousands of inner-city drug abusers. In recent years, there has been much liberal criticism of the war on drugs as an epic waste of money and resources, but “13TH” — rightly — recontextualizes the war on drugs as a race war.

DuVernay keeps flashing a time-clock of the rising prison population. In 1970, it was 357,292, and by 1980 it had risen it 513,900. In 1990, it was 1,179,200, and it is currently 2.3 million. (Forty percent of those prisoners are African-American.) It’s the biggest U.S. growth industry! The terrible thing is, I’m not joking. DuVernay anatomizes the racist and capitalist underpinnings of the era of mass incarceration in a way that makes “13TH” an indelible act of social-political inquiry. The movie fills in each level of how it works, starting with the rise of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), the lobbying club on steroids that unites corporate leaders and politicians, so that the corporate leaders can write big checks and craft the legislation that is then “recommended” to Congress. As the film reveals, it was ALEC that came up with the cornerstones of President Clinton’s 1994 crime bill: the mandatory sentencing, the “three strikes” clause, and so on.

The conflict of interest is stunning. For a long time, the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), the nation’s largest private prison company, was a member of ALEC, and so was Wal-Mart, which had a vested interested in playing up “stand your ground” laws because the result of those laws is that gun sales shot up (and Wal-Mart is a major merchandiser of firearms). The very notion that the American prison system is now being run by private corporations, with a profiteering interest in maintaining a large prison population, represents a fundamental — and indefensible — transfer of power in our society. The entire prison system has become a racket. The word for that situation is…well, I’m a film critic, not an editorial writer, so I won’t say the word. What I will say is: Watch “13TH” and draw your own conclusion.

There are some who may carp at the powerful case Ava DuVernay makes in “13TH.” Because her take on these issues is complex, she can’t point every time to a smoking gun (though her film has several holsters’ worth of them). Yet one of the staggering things this movie captures is how racism could be the driving force behind something as seismic as the rise of mass incarceration in America, yet that racism could remain in many ways “invisible.” So some people will be driven to say the racism isn’t there. But what they’re really saying is: It’s not a white people problem. A film as starkly humane as “13TH” makes you realize that it’s everyone’s problem.

Reviewed online, Sept. 29, 2016. Running time: 100 MIN.

- Production: A Netflix release. Producers: Ava DuVernay, Howard Barish. Executive producers: Lisa Nishimura, Ben Cotner, Adam Del Deo, Angus Wall, Jason Sterman.

- Crew: Director: Ava DuVernay. Screenplay: DuVernay, Spencer Averick. Camera (color, widescreen): Hans Charles, Kira Kelly. Editor: Spencer Averick.

- With: Melina Abdullah, Michelle Alexander, Cory Booker, Dolores Canales, Gina Clayton, Jelani Cobb, Malkia Cyril, Angela Davis, Craig DeRoche, David Dinkins, Baz Dreisinger, Kevin Gannon, Henry Louis Gates Jr., Newt Gingrich, Lisa Graves, Van Jones.

More From Our Brands

Jon stewart mocks media for covering trump’s courtroom commute, sketch artist interviews, shaun white lists his midcentury modern hideaway in the hollywood hills for $5 million, alexis ohanian’s 776 foundation invests in women’s sports bar, be tough on dirt but gentle on your body with the best soaps for sensitive skin, all american gets extra season 6 episodes, eyes a wave of new cast members if renewed (report), verify it's you, please log in.

Log in or sign up for Rotten Tomatoes

Trouble logging in?

By continuing, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes.

Email not verified

Let's keep in touch.

Sign up for the Rotten Tomatoes newsletter to get weekly updates on:

- Upcoming Movies and TV shows

- Trivia & Rotten Tomatoes Podcast

- Media News + More

By clicking "Sign Me Up," you are agreeing to receive occasional emails and communications from Fandango Media (Fandango, Vudu, and Rotten Tomatoes) and consenting to Fandango's Privacy Policy and Terms and Policies . Please allow 10 business days for your account to reflect your preferences.

OK, got it!

Movies / TV

No results found.

- What's the Tomatometer®?

- Login/signup

Movies in theaters

- Opening this week

- Top box office

- Coming soon to theaters

- Certified fresh movies

Movies at home

- Fandango at Home

- Netflix streaming

- Prime Video

- Most popular streaming movies

- What to Watch New

Certified fresh picks

- Challengers Link to Challengers

- Abigail Link to Abigail

- Arcadian Link to Arcadian

New TV Tonight

- The Jinx: Season 2

- Knuckles: Season 1

- THEM: The Scare: Season 2

- Velma: Season 2

- The Big Door Prize: Season 2

- Secrets of the Octopus: Season 1

- Dead Boy Detectives: Season 1

- Thank You, Goodnight: The Bon Jovi Story: Season 1

- We're Here: Season 4

Most Popular TV on RT

- Baby Reindeer: Season 1

- Fallout: Season 1

- The Sympathizer: Season 1

- Ripley: Season 1

- Shōgun: Season 1

- 3 Body Problem: Season 1

- Under the Bridge: Season 1

- Sugar: Season 1

- A Gentleman in Moscow: Season 1

- Parasyte: The Grey: Season 1

- Best TV Shows

- Most Popular TV

- TV & Streaming News

Certified fresh pick

- Under the Bridge Link to Under the Bridge

- All-Time Lists

- Binge Guide

- Comics on TV

- Five Favorite Films

- Video Interviews

- Weekend Box Office

- Weekly Ketchup

- What to Watch

The Best TV Seasons Certified Fresh at 100%

Best TV Shows of 2024: Best New Series to Watch Now

What to Watch: In Theaters and On Streaming

Awards Tour

Weekend Box Office Results: Civil War Earns Second Victory in a Row

Deadpool & Wolverine : Release Date, Trailer, Cast & More

- Trending on RT

- Rebel Moon: Part Two - The Scargiver

- The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare

- Play Movie Trivia

Where to Watch

Watch 13TH with a subscription on Netflix.

What to Know

13th strikes at the heart of America's tangled racial history, offering observations as incendiary as they are calmly controlled.

Audience Reviews

Cast & crew.

Ava DuVernay

Michelle Alexander

Bryan Stevenson

Newt Gingrich

Grover Norquist

Best Movies to Stream at Home

Movie news & guides, this movie is featured in the following articles., critics reviews.

Common Sense Media

Movie & TV reviews for parents

- For Parents

- For Educators

- Our Work and Impact

Or browse by category:

- Get the app

- Movie Reviews

- Best Movie Lists

- Best Movies on Netflix, Disney+, and More

Common Sense Selections for Movies

50 Modern Movies All Kids Should Watch Before They're 12

- Best TV Lists

- Best TV Shows on Netflix, Disney+, and More

- Common Sense Selections for TV

- Video Reviews of TV Shows

Best Kids' Shows on Disney+

Best Kids' TV Shows on Netflix

- Book Reviews

- Best Book Lists

- Common Sense Selections for Books

8 Tips for Getting Kids Hooked on Books

50 Books All Kids Should Read Before They're 12

- Game Reviews

- Best Game Lists

Common Sense Selections for Games

- Video Reviews of Games

Nintendo Switch Games for Family Fun

- Podcast Reviews

- Best Podcast Lists

Common Sense Selections for Podcasts

Parents' Guide to Podcasts

- App Reviews

- Best App Lists

Social Networking for Teens

Gun-Free Action Game Apps

Reviews for AI Apps and Tools

- YouTube Channel Reviews

- YouTube Kids Channels by Topic

Parents' Ultimate Guide to YouTube Kids

YouTube Kids Channels for Gamers

- Preschoolers (2-4)

- Little Kids (5-7)

- Big Kids (8-9)

- Pre-Teens (10-12)

- Teens (13+)

- Screen Time

- Social Media

- Online Safety

- Identity and Community

Explaining the News to Our Kids

- Family Tech Planners

- Digital Skills

- All Articles

- Latino Culture

- Black Voices

- Asian Stories

- Native Narratives

- LGBTQ+ Pride

- Best of Diverse Representation List

Celebrating Black History Month

Movies and TV Shows with Arab Leads

Celebrate Hip-Hop's 50th Anniversary

Common sense media reviewers.

Searing docu decries racial bias; intense violence, cursing.

A Lot or a Little?

What you will—and won't—find in this movie.

Among the many messages, raises important issues a

For the most part, the interviewees have strong co

Violence is harsh, frequent, and REAL. Newsreel an

Two men are naked as they are dragged by police of

Infrequent but prominent: the "N" word, "f--k," "a

Parents need to know that 13th is a powerful documentary that addresses racial issues confronting America in 2016. In a time of polarized attitudes about mass incarceration, brutality, and the explosion of for-profit prisons and their affiliates, director Ava DuVernay interviews social activists, academics,…

Positive Messages

Among the many messages, raises important issues about the economic and personal exploitation of African Americans and other people of color in the U.S., with the intent of motivating citizen action to right terrible wrongs. Asserts that cheap ("slave") labor is an underlying cause of the distortion in America's justice system. Discredits "law and order" as a viable concept, instead sees the term as a code for arrest and prosecution of persons of color. Advocates sincere reform and separating the criminal justice system from any for-profit organizations.

Positive Role Models

For the most part, the interviewees have strong convictions, are highly motivated, and well-informed. Many of them are actively involved in efforts to reform a broken system. In an effort to balance assertions and correctly assign "blame," DuVernay places responsibility for current situation on both Democratic and Republican leaders.

Violence & Scariness

Violence is harsh, frequent, and REAL. Newsreel and videocam footage includes: rioting, beatings, lynching, brutality, recent killings (up-close) of African Americans by police, and people being tormented, intimidated, and threatened by law enforcement and fellow citizens. Men are kicked, dragged, stripped, caged, menaced by dogs. Scenes from earlier films depict attempted rapes and sexual assaults.

Did you know you can flag iffy content? Adjust limits for Violence & Scariness in your kid's entertainment guide.

Sex, Romance & Nudity

Two men are naked as they are dragged by police officers.

Did you know you can flag iffy content? Adjust limits for Sex, Romance & Nudity in your kid's entertainment guide.

Infrequent but prominent: the "N" word, "f--k," "a--hole."

Did you know you can flag iffy content? Adjust limits for Language in your kid's entertainment guide.

Parents Need to Know

Parents need to know that 13th is a powerful documentary that addresses racial issues confronting America in 2016. In a time of polarized attitudes about mass incarceration, brutality, and the explosion of for-profit prisons and their affiliates, director Ava DuVernay interviews social activists, academics, journalists, and political figures to make the case that today's prisons, which house millions of persons of color, are simply the next incarnation of the centuries-old U.S. exploitation of those who have been deemed "lesser personages." Using archival footage and a clearly developed historical narration to bolster her contention, DuVernay's epic film is not for the faint of heart. The violence onscreen is not "re-created"; it gives prominence to actual beatings, murders, deaths from point-blank gunshots, lynching, and the profound intimidation and caging of both individuals and large groups of African Americans. Incendiary language (visual and audio uses of the "N" word, "f--k," "a--hole") as well as discussions of rape and sexual assault add to the impact of the story. Two men are naked as they are dragged by police officers. Provocative and heartbreakingly real, this documentary is recommended for mature teens and up. To stay in the loop on more movies like this, you can sign up for weekly Family Movie Night emails .

Where to Watch

Videos and photos.

Community Reviews

- Parents say (11)

- Kids say (7)

Based on 11 parent reviews

Succinct and powerful documentary about a complex and multifaceted topic

Amazing and inspiring, what's the story.

A reading of one sentence in the 13th Amendment to our Constitution is the foundation of Ava DuVernay's documentary, 13TH. "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction." And, the "except as a punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted" are the words that form the basis of her well-executed thesis. First, summing up the history of African Americans in the U.S., accompanied by the archival footage, newsreels, documents, and filmed speeches of past leaders, DuVernay declares that today's modern racial injustice is simply an extension of America's past racial behavior... from slavery to convict-leasing to Jim Crow and forward. Then, intercut with the footage, are in-depth conversations with prominent, effective leaders from both the African-American and white communities (academics, social activists, journalists, politicians). Organizing her material into concise, relevant sections, divided by animated titles with rap music on the soundtrack, the director and her team cover every aspect of the current controversial racial issues: moral, sociological, and economic. The film is a fiery indictment of the status quo, and an undisguised appeal to change it.

Is It Any Good?

In this fierce call to action, director Ava DuVernay effectively doubles down on both educating her viewers and inspiring them to take a stand against racial injustice in 2016 America. Hoping to provide a semblance of political balance to her efforts in 13th , DuVernay asserts that both Democratic and Republican administrations are responsible for burgeoning prison populations and the devastating effect of past policies on an entire minority population. Additionally, she interviews well-known conservatives, like Newt Gingrich and Grover Norquist. However, given the evidence on screen, it's difficult to provide an "other side" of the film's arguments. Particularly compelling are sequences in which she identifies some of the most noxious corporations and/or organizations (Correction Corporation of America, National Correction Industries Association, American Legislation Exchange Council) that profit from and depend upon the rounding up of as many able-bodied men as possible. And she unabashedly includes the chilling footage from a number of recent police shootings of unarmed African-American men and boys. Challenging, disturbing, and confrontational, this film is must-see viewing for mature and concerned Americans.

Talk to Your Kids About ...

Families can talk about the purpose of 13th . Documentaries always have specific aims: to entertain, inform, persuade, or inspire. How many of these categories are relevant to this film? Do you think director Ava DuVernay successfully accomplished these goals?

If this movie inspired you, what might you and/or your family and friends do to take action to change this situation? Some possibilities might be: actively working to elect like-minded individuals; recommending this film to others; joining and working with specific organizations that have influence in your community or on the internet.

What surprised you most about our country's treatment of African-American citizens over its long history? By the film's end, did DuVernay convince you that today's mass incarceration of Americans of color is an extension of slavery? Why or why not?

Movie Details

- On DVD or streaming : October 7, 2016

- Cast : Van Jones , Michelle Alexander , Cory Booker

- Director : Ava DuVernay

- Inclusion Information : Female directors, Black directors, Black actors

- Studio : Netflix

- Genre : Documentary

- Run time : 100 minutes

- MPAA rating : NR

- Last updated : February 18, 2023

Did we miss something on diversity?

Research shows a connection between kids' healthy self-esteem and positive portrayals in media. That's why we've added a new "Diverse Representations" section to our reviews that will be rolling out on an ongoing basis. You can help us help kids by suggesting a diversity update.

Suggest an Update

Our editors recommend.

The Hate U Give

When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts

Eyes on the Prize

The Black List: Vol. 1

Great Movies with Black Characters

Graphic novels that teach history.

Common Sense Media's unbiased ratings are created by expert reviewers and aren't influenced by the product's creators or by any of our funders, affiliates, or partners.

13th (2016) | Transcript

- October 25, 2023

13th is a 2016 American documentary film directed by Ava DuVernay. The film explores the intersection of race, justice, and mass incarceration in the United States. The title refers to the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which abolished slavery throughout the United States and ended involuntary servitude except as a punishment for conviction of a crime. The documentary argues that slavery has continued in the United States by criminalizing certain behavior, convict-leasing, suppressing African Americans, the war on drugs, and mass incarceration. The film features interviews with activists, politicians, scholars, and formerly incarcerated individuals. It was released on Netflix on October 7, 2016.

[Barack Obama] So let’s look at the statistics.

The United States is home to 5% of the world’s population… but 25% of the world’s prisoners.

Think about that.

[Van Jones] A little country with 5% of the world’s population having 25% of the world’s prisoners?

One out of four?

One out of four human beings with their hands on bars, shackled, in the world are locked up here, in the land of the free.

We had a prison population of 300,000 in 1972.

Today, we have a prison population of 2.3 million.

The United States now has the highest rate of incarceration in the world.

So, you see, now suddenly they’re in an awakening that, “Oh, perhaps we need to downsize our prison system. It’s gotten too expensive. It’s gotten out of hand.”

Um, but the very folks who often express so much concern, uh, about the cost and the expanse of the system are often very unwilling to talk in any serious way about remedying the harm that has been done.

History is not just stuff that happens by accident.

We are the products of the history that our ancestors chose, if we’re white.

If we are black, we are products of the history that our ancestors most likely did not choose.

Yet here we all are together, the products of that set of choices.

And we have to understand that in order to escape from it.

The 13th Amendment to the Constitution makes it unconstitutional for someone to be held as a slave.

In other words, it grants freedom… to all Americans.

There are exceptions, including criminals.

[Khalil G. Muhammad] There’s a clause, a loophole.

[Kevin Gannon] If you have that in the structure, in this constitutional language, then it’s there to be used as a tool for whichever purposes one wants to use it.

[Cobb] One of the things to bear in mind is that when we think about slavery, it was an economic system.

And the demise of slavery at the end of the Civil War left the Southern economy in tatters. Uh, and so this presented a big question.

There are four million people who were formerly property, and they were formerly kind of the integral part of the economic production system in the South.

And now those people are free.

And so what do you do with these people?

How do you rebuild your economy?

The 13th Amendment loophole was immediately exploited.

After the Civil War, African Americans were arrested en masse.

It was our nation’s first prison boom.

[Gannon] You were basically a slave again. The 13th Amendment says that “Except for criminals, everybody else is free.”

Well, now if you’re criminalized, that doesn’t apply to you.

[Michelle Alexander] They were arrested for extremely minor crimes, like loitering or vagrancy.

And they had to provide labor to rebuild the economy of the South after the Civil War.

[Cobb] What you got after that was a rapid transition to a kind of mythology of black criminality.

Go back and, you know, read the rhetoric that people used then.

They would say that the Negro was out of control, that there’s a threat of violence to white women.

So the same sort of image that we had of Uncle Remus and these genial, kind of, black figures was replaced by this rapacious, uh, menacing, Negro male evil that had to be banished.

[Gannon] Birth of a Nation was just a profoundly important cultural event.

[Muhammad] It’s the first major blockbuster film, hailed for both its artistic achievement and for its political commentary.

And when it was released, it had this rapturous response.

You know, there were lines everywhere that it was being shown.

Birth of a Nation confirmed the story that many whites wanted to tell about the Civil War and its aftermath.

To erase defeat and to take out of it sort of a martyrdom.

Woodrow Wilson, the sitting president, had a private screening of it in the White House. He calls it, “History written with lightning.”

And every image you see of a black person is a demeaned, animal-like image.

Cannibalistic, animalistic.

The image of the African American male.

[Cobb] There’s a famous scene where a woman throws herself off a cliff rather than be raped by a black male criminal.

In the film, you see black people being a threat to white women.

All the myths of black men as rapists was ultimately stemmed by the reality that the white political elite and the business establishment needed black bodies working.

[Cobb] What we overlook about Birth of a Nation is that it was also a tremendously accurate prediction of the way in which race would operate in the United States.

[Cobb] Birth of a Nation was almost directly responsible for the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan.

It had received this romantic, glowing, heroic portrait.

The Klan never had the ritual of burning the cross.

That was something that D.W. Griffith came up with because he thought that it was a great cinematic image.

So it was literally an instance of life imitating art.

The ripples emanate far out from just the simple fact that it’s a movie in the early motion picture age.

[Cobb] With the tremendous burst of popularity that the Ku Klux Klan had as a result of Birth of a Nation came another wave of terrorism.

[Stevenson] We had lynchings between Reconstruction and World War II.

Thousands of African Americans murdered by mobs under the idea that they had done something criminal.

[reporter] At the National Democratic Convention in New York in 1924, it is estimated that at least 350 delegates were Klansmen.

[Stevenson] The demographic geography of this country was shaped by that era.

Now we have African Americans in Los Angeles, in Oakland, and Chicago, and Cleveland, Detroit, Boston, New York.

And very few people appreciate that the African Americans in those communities did not go there as immigrants looking for new economic opportunities.

They went there as refugees from terror.

We didn’t just land in Oakland, in LA, in Compton, in Harlem, in Brownsville in 2015.

This is generational… generational trauma.

[reporter] The letters “KKK” were carved with a penknife on the chest and stomach of this man in Houston, Texas, after he had been hanged by his knees from an oak tree and flogged with a chain.

The Chicago Negro boy, Emmett Till, is alleged to have paid unwelcome attention to Roy Bryant’s most attractive wife.

[Stevenson] And then when it became unacceptable to engage in that kind of open terrorism, then it shifted to something more legal.

Segregation. Jim Crow.

[Alexander] Laws were passed that relegated African Americans to a permanent second-class status.

These things really begin to live out the prophecy that Griffith was making about the way that race operates.

And this fear of crime is central to all of this.

Every time you saw a sign that said “white and colored,” every time you had to deal with the indignation of being told you can’t go through the front door.

Every day you weren’t allowed to vote, weren’t allowed to go to school, you were bearing a burden that was injurious.

[Alexander] Civil rights activists began to see the necessity of building not just a civil rights movement, but a human rights movement.

[Martin Luther King Jr.] And I think we should start now preparing for the inevitable.

[crowd] Yeah!

[King] And let us, when that moment comes… go into the situations that we confront with a great deal of dignity, sanity and reasonableness.

[KKK member] They want to throw white children and colored children into the melting pot of integration, through out of which will come a conglomerated, mulatto, mongrel class of people.

Both races will be destroyed in such a movement.

[reporter 1] We just got a report here on this end that the students are in.

[reporter 2] Negroes were trying to integrate the bathing beaches.

And the Florida Advisory Committee to the US Civil Rights Commission warned that the city was becoming a racial superbomb with a short fuse.

[Alexander] Civil rights activists began to be portrayed in the media and among, you know, many politicians as criminals.

People who are deliberately violating the law, segregation laws that existed in the South.

[King] For years now, I have heard the word “wait.”

It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity.

This wait has almost always meant never.

Justice too long delayed is justice denied.

I think that one of the most brilliant tactics of the civil rights movement was its transformation of the notion of criminality.

Because for the first time, being arrested was a noble thing.

Being arrested by white people was your worst nightmare.

Still is, uh, for many African Americans.

So what’d they do?

They voluntarily defined a movement around getting arrested.

They turned it on its head.

[Cobb] If you looked at the history of black people’s various struggles in this country, the connecting theme is the attempt to be understood as full, complicated human beings.

We are something other than this, uh, visceral image of criminality and menace and threat to which people associate with us.

[protestors screaming]

We’re willing to be beaten for democracy, and you misuse democracy in the street.

Let us lay aside irrelevant differences… and make our nation whole.

[applauding]

[Gates] The Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act said, “Finally, we admit it. Though slavery ended in December 1865… we took away these people’s rights, and now we’re gonna fix it.”

[Marc Mauer] For the first time, you know, promise of equal justice becomes at least a possibility.

Their cause must be our cause, too.

[Alexander] Unfortunately, at the very same time that the civil rights movement was gaining steam, crime rates were beginning to rise in this country.

Crime was increasing in the baby boom generation that had emerged immediately after World War II.

Now they were adults.

So, just through sheer demographic change, we had an increase in the amount of crime.

…and became very easy for politicians then to say, um, that the civil rights movement itself was contributing to rising crime rates, and that if we were to give the Negroes their freedom, um, then we would be repaid, as a nation, with crime.

[Stevenson] The prison population in the United States was largely flat throughout most of the 20th century.

It didn’t go up a lot. It didn’t come down a lot.

But that changed in the 1970s.

And in the 1970s, we began an era which has been defined by this term, “mass incarceration.”

This is a nation of laws, and as Abraham Lincoln has said, “No one is above the law. No one is below the law.”

And we’re going to enforce the law and Americans should remember that, if we’re going to have law and order.

♪ Breaking rocks out here On the chain gang ♪

♪ Breaking rocks and serving my time ♪

♪ Because I’ve been convicted of crime ♪

♪ Hold it steady right there While I hit it ♪

[Richard Nixon] Each moment in history is a fleeting time, precious and unique.

But some stand out as moments of beginning… in which courses are set that shape decades or centuries.

This can be such a moment.

It’s with the Nixon era, and the law and order period when crime begins to stand in for race.

If there is one area where the word “war” is appropriate, it is in the fight against crime.

Part of what he talked about was a war on crime.

But that was one of those code words, what we might call “dog-whistle politics” now, which really was referring to the black political movements of the day, Black Power, Black Panthers, the antiwar movement, the movements for women’s and gay liberation at that time, which Nixon felt compelled to fight back against.

Once the federal government, through the FBI, moves into an area, this should be warning to those who engage in these acts that they eventually are going to be apprehended.

[Cobb] There’s this outcry for law and order.

And Nixon becomes the person who articulates that perfectly.

[Nixon] There can be no progress in America without respect for law.

Many people felt like, uh, we were losing control.

[Nixon] We need total war in the United States against the evils, uh, that we see in our cities.

Federal spending for local law enforcement will double.

Time is running out for the merchants of crime and corruption in American society.

[siren wailing]

The wave of crime is not going to be the wave of the future in the United States of America.

We must wage what I have called “total war” against public enemy number one in the United States, the problem of dangerous drugs.

“A war on drugs.”

And that utterance gave birth to this era, where we decided to deal with drug addiction and drug dependency as a crime issue rather than a health issue.

Hundreds of thousands of people were sent to jails and prisons for simple possession of marijuana, for low-level offenses.

America’s public enemy number one in the United States is drug abuse.

In order to fight and defeat this enemy, it is necessary to wage a new, all-out offensive.

This call for law and order becomes integral to something that comes to be known as the Southern strategy.

Nixon begins to recruit Southern whites, formerly staunch Democrats, into the Republican fold.

[Alexander] Persuading poor and working-class whites to join the Republican Party in droves…

By speaking to, in subtle and non-racist terms…

…a thinly veiled racial appeal…

…talking about crime, by talking about law and order or the chaos of our urban cities unleashed by the civil rights movement.

[Nixon] We have launched an all-out offensive against crime, against narcotics, against permissiveness in our country.

[Alexander] The rhetoric of “get tough” and “law and order,” um, was part and parcel of the backlash of the civil rights movement.

[reporter] A Nixon administration official admitted the war on drugs was all about throwing black people in jail.

He said, quote,

♪ The end of the Reagan era I’m like 11 or 12 or ♪