- Customer Reviews

- Extended Essays

- IB Internal Assessment

- Theory of Knowledge

- Literature Review

- Dissertations

- Essay Writing

- Research Writing

- Assignment Help

- Capstone Projects

- College Application

- Online Class

How to Write an Abstract for Research Proposal

by Antony W

December 13, 2021

An abstract in a research proposal summarizes the main aspect of the assignment in a given sequence in 300 words or less. It highlights the purpose of the study, the research problem, design of the study, findings, summary of your interpretations and conclusions.

For what it’s worth, the abstract of your research proposal should give a clear and concise elaboration of the major aspects of an issue you’ve investigated.

In this guide, you’ll learn how to write an abstract for any research proposal. We’ll look at why an abstract is important, the types of abstracts, writing style, and what to avoid when it comes to writing an abstract for your research proposal.

Types of Abstracts for a Research Proposal

There are four types of abstracts that you can write for a research proposal:

- Critical abstract

- Descriptive abstract

- Informative abstract

- Highlight abstract

1. Critical abstract

A critical abstract in a research proposal describes the primary findings and gives a solid judgment on the validity, completeness, and reliability of the study. It’s your responsibility as a researcher to evaluate your work and then compare it with already existing work on the same subject.

Because a critical abstract includes an additional commentary, it tends to longer. Often, the length falls between 400 and 500 words. However, do keep in mind that this type of an abstract is very are, which means your instructor may never ask you to write a critical abstract for your research proposal.

2. Highlight Abstract

A highlight abstract is a piece of writing that can’t stand independent of its associated document. It uses incomplete and leading remarks, with the primary goal of grabbing the attention of the reader to the study.

Professors have made it clear that a highlight abstract is not by itself a true abstract to use in a research proposal. Since it cannot stand on its away separate from the associated article, it’s unlikely that your teacher will ask you to use it in academic writing.

3. Descriptive abstract

A descriptive abstract gives a short description of the research proposal. It may include purpose, method, and the scope of the research, and it’s often 100 words or less in length. Some people consider it to be an outline of the research proposal rather than an actual abstract for the document.

While a descriptive abstract describes the type of information a reader will find in a research proposal, it neither critics the work nor provides results and conclusion of the study.

4. Informative Abstract

Many abstracts in academic writing are informative. They don’t analyze the study or investigation that you propose, but they explain a research project in a way that they can stand independently. In other words, an informative abstract gives an explanation for the main arguments, evidence, and significant results.

In addition to featuring purpose, method, and scope, an informative abstract also include the results, conclusion, as well as the recommendation of the author. As for the length, an informative abstract should not be more than 300 words.

How to Write an Abstract for a Research Proposal

Of the four type of abstracts that we’ve discussed above, an informative abstract is what you’ll need to write in your research proposal. Writing an abstract for a research proposal isn’t difficult at all. You only need to know what to write and how to write it, and you’re good to get started.

1. Write in Active Voice

First, use active voice when writing an abstract for your research proposal. However, this doesn’t mean you should avoid passive voice in entirety. If you find that some sentences can’t make sense unless with passive sentence construction, feel free to bend this rule somewhat.

Second, make sure your sentences are concise and complete. Refrain from using ambiguous words. Keep the language simple instead.

Lastly, never use present or future tense to write an abstract for a research proposal. You’re reporting a study that you’ve already conducted and therefore writing in past sense makes the most sense.

Your abstract should come immediately after the title page. Write in block format without paragraph indentations. The abstract should not be more than 300 words long and the page should not have a number. The word “Abstract” in your research proposal should be center aligned in the page, unless otherwise stated.

In addition to these formatting rules, the last sentence of your abstract should summarize the application to practice or the conclusions of your study. In the case where it seems appropriate, you might want follow this by statement that suggests a need for additional research.

3. Time to Write the Abstract

There are no hard rules on when to write an abstract for a research proposal. Some students choose to write the section first while others choose to write it last. We strongly recommend that you write the abstract last because it’s a summary of the whole paper. You can also write it in the beginning if you’ve already outlined your draft and know what you want to talk about even before you start writing.

Your informative abstract is subject to frequent changes as you work on your paper, and that holds whether you write the section first or last. Be flexible and tweak this part of the assignment as necessary. Also, make sure you report statistical findings in parentheses.

Read abstract to be sure the summary of the study agrees with what you’ve written in your proposal. As we mentioned earlier, this section is subject to change depending on the direction your research takes. So make sure you identify and correct any anomalies if any.

Mistakes to Avoid When Writing an Abstract for Research Proposal

To wind up this guide, here are some of the most common mistakes that you should avoid when writing an abstract for your research proposal:

- Avoid giving a lengthy background

- Don’t include citations to other people’s work

- An abstract shouldn’t include a table, figure, image, or any kind of illustration

- Don’t include terms that are difficult to understand

About the author

Antony W is a professional writer and coach at Help for Assessment. He spends countless hours every day researching and writing great content filled with expert advice on how to write engaging essays, research papers, and assignments.

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Definition and Purpose of Abstracts

An abstract is a short summary of your (published or unpublished) research paper, usually about a paragraph (c. 6-7 sentences, 150-250 words) long. A well-written abstract serves multiple purposes:

- an abstract lets readers get the gist or essence of your paper or article quickly, in order to decide whether to read the full paper;

- an abstract prepares readers to follow the detailed information, analyses, and arguments in your full paper;

- and, later, an abstract helps readers remember key points from your paper.

It’s also worth remembering that search engines and bibliographic databases use abstracts, as well as the title, to identify key terms for indexing your published paper. So what you include in your abstract and in your title are crucial for helping other researchers find your paper or article.

If you are writing an abstract for a course paper, your professor may give you specific guidelines for what to include and how to organize your abstract. Similarly, academic journals often have specific requirements for abstracts. So in addition to following the advice on this page, you should be sure to look for and follow any guidelines from the course or journal you’re writing for.

The Contents of an Abstract

Abstracts contain most of the following kinds of information in brief form. The body of your paper will, of course, develop and explain these ideas much more fully. As you will see in the samples below, the proportion of your abstract that you devote to each kind of information—and the sequence of that information—will vary, depending on the nature and genre of the paper that you are summarizing in your abstract. And in some cases, some of this information is implied, rather than stated explicitly. The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , which is widely used in the social sciences, gives specific guidelines for what to include in the abstract for different kinds of papers—for empirical studies, literature reviews or meta-analyses, theoretical papers, methodological papers, and case studies.

Here are the typical kinds of information found in most abstracts:

- the context or background information for your research; the general topic under study; the specific topic of your research

- the central questions or statement of the problem your research addresses

- what’s already known about this question, what previous research has done or shown

- the main reason(s) , the exigency, the rationale , the goals for your research—Why is it important to address these questions? Are you, for example, examining a new topic? Why is that topic worth examining? Are you filling a gap in previous research? Applying new methods to take a fresh look at existing ideas or data? Resolving a dispute within the literature in your field? . . .

- your research and/or analytical methods

- your main findings , results , or arguments

- the significance or implications of your findings or arguments.

Your abstract should be intelligible on its own, without a reader’s having to read your entire paper. And in an abstract, you usually do not cite references—most of your abstract will describe what you have studied in your research and what you have found and what you argue in your paper. In the body of your paper, you will cite the specific literature that informs your research.

When to Write Your Abstract

Although you might be tempted to write your abstract first because it will appear as the very first part of your paper, it’s a good idea to wait to write your abstract until after you’ve drafted your full paper, so that you know what you’re summarizing.

What follows are some sample abstracts in published papers or articles, all written by faculty at UW-Madison who come from a variety of disciplines. We have annotated these samples to help you see the work that these authors are doing within their abstracts.

Choosing Verb Tenses within Your Abstract

The social science sample (Sample 1) below uses the present tense to describe general facts and interpretations that have been and are currently true, including the prevailing explanation for the social phenomenon under study. That abstract also uses the present tense to describe the methods, the findings, the arguments, and the implications of the findings from their new research study. The authors use the past tense to describe previous research.

The humanities sample (Sample 2) below uses the past tense to describe completed events in the past (the texts created in the pulp fiction industry in the 1970s and 80s) and uses the present tense to describe what is happening in those texts, to explain the significance or meaning of those texts, and to describe the arguments presented in the article.

The science samples (Samples 3 and 4) below use the past tense to describe what previous research studies have done and the research the authors have conducted, the methods they have followed, and what they have found. In their rationale or justification for their research (what remains to be done), they use the present tense. They also use the present tense to introduce their study (in Sample 3, “Here we report . . .”) and to explain the significance of their study (In Sample 3, This reprogramming . . . “provides a scalable cell source for. . .”).

Sample Abstract 1

From the social sciences.

Reporting new findings about the reasons for increasing economic homogamy among spouses

Gonalons-Pons, Pilar, and Christine R. Schwartz. “Trends in Economic Homogamy: Changes in Assortative Mating or the Division of Labor in Marriage?” Demography , vol. 54, no. 3, 2017, pp. 985-1005.

![what is a research proposal abstract “The growing economic resemblance of spouses has contributed to rising inequality by increasing the number of couples in which there are two high- or two low-earning partners. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the topic under study (the “economic resemblance of spouses”). This sentence also implies the question underlying this research study: what are the various causes—and the interrelationships among them—for this trend?] The dominant explanation for this trend is increased assortative mating. Previous research has primarily relied on cross-sectional data and thus has been unable to disentangle changes in assortative mating from changes in the division of spouses’ paid labor—a potentially key mechanism given the dramatic rise in wives’ labor supply. [Annotation for the previous two sentences: These next two sentences explain what previous research has demonstrated. By pointing out the limitations in the methods that were used in previous studies, they also provide a rationale for new research.] We use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to decompose the increase in the correlation between spouses’ earnings and its contribution to inequality between 1970 and 2013 into parts due to (a) changes in assortative mating, and (b) changes in the division of paid labor. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The data, research and analytical methods used in this new study.] Contrary to what has often been assumed, the rise of economic homogamy and its contribution to inequality is largely attributable to changes in the division of paid labor rather than changes in sorting on earnings or earnings potential. Our findings indicate that the rise of economic homogamy cannot be explained by hypotheses centered on meeting and matching opportunities, and they show where in this process inequality is generated and where it is not.” (p. 985) [Annotation for the previous two sentences: The major findings from and implications and significance of this study.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-1.png)

Sample Abstract 2

From the humanities.

Analyzing underground pulp fiction publications in Tanzania, this article makes an argument about the cultural significance of those publications

Emily Callaci. “Street Textuality: Socialism, Masculinity, and Urban Belonging in Tanzania’s Pulp Fiction Publishing Industry, 1975-1985.” Comparative Studies in Society and History , vol. 59, no. 1, 2017, pp. 183-210.

![what is a research proposal abstract “From the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s, a network of young urban migrant men created an underground pulp fiction publishing industry in the city of Dar es Salaam. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the context for this research and announces the topic under study.] As texts that were produced in the underground economy of a city whose trajectory was increasingly charted outside of formalized planning and investment, these novellas reveal more than their narrative content alone. These texts were active components in the urban social worlds of the young men who produced them. They reveal a mode of urbanism otherwise obscured by narratives of decolonization, in which urban belonging was constituted less by national citizenship than by the construction of social networks, economic connections, and the crafting of reputations. This article argues that pulp fiction novellas of socialist era Dar es Salaam are artifacts of emergent forms of male sociability and mobility. In printing fictional stories about urban life on pilfered paper and ink, and distributing their texts through informal channels, these writers not only described urban communities, reputations, and networks, but also actually created them.” (p. 210) [Annotation for the previous sentences: The remaining sentences in this abstract interweave other essential information for an abstract for this article. The implied research questions: What do these texts mean? What is their historical and cultural significance, produced at this time, in this location, by these authors? The argument and the significance of this analysis in microcosm: these texts “reveal a mode or urbanism otherwise obscured . . .”; and “This article argues that pulp fiction novellas. . . .” This section also implies what previous historical research has obscured. And through the details in its argumentative claims, this section of the abstract implies the kinds of methods the author has used to interpret the novellas and the concepts under study (e.g., male sociability and mobility, urban communities, reputations, network. . . ).]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-2.png)

Sample Abstract/Summary 3

From the sciences.

Reporting a new method for reprogramming adult mouse fibroblasts into induced cardiac progenitor cells

Lalit, Pratik A., Max R. Salick, Daryl O. Nelson, Jayne M. Squirrell, Christina M. Shafer, Neel G. Patel, Imaan Saeed, Eric G. Schmuck, Yogananda S. Markandeya, Rachel Wong, Martin R. Lea, Kevin W. Eliceiri, Timothy A. Hacker, Wendy C. Crone, Michael Kyba, Daniel J. Garry, Ron Stewart, James A. Thomson, Karen M. Downs, Gary E. Lyons, and Timothy J. Kamp. “Lineage Reprogramming of Fibroblasts into Proliferative Induced Cardiac Progenitor Cells by Defined Factors.” Cell Stem Cell , vol. 18, 2016, pp. 354-367.

![what is a research proposal abstract “Several studies have reported reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes; however, reprogramming into proliferative induced cardiac progenitor cells (iCPCs) remains to be accomplished. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence announces the topic under study, summarizes what’s already known or been accomplished in previous research, and signals the rationale and goals are for the new research and the problem that the new research solves: How can researchers reprogram fibroblasts into iCPCs?] Here we report that a combination of 11 or 5 cardiac factors along with canonical Wnt and JAK/STAT signaling reprogrammed adult mouse cardiac, lung, and tail tip fibroblasts into iCPCs. The iCPCs were cardiac mesoderm-restricted progenitors that could be expanded extensively while maintaining multipo-tency to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells in vitro. Moreover, iCPCs injected into the cardiac crescent of mouse embryos differentiated into cardiomyocytes. iCPCs transplanted into the post-myocardial infarction mouse heart improved survival and differentiated into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells. [Annotation for the previous four sentences: The methods the researchers developed to achieve their goal and a description of the results.] Lineage reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs provides a scalable cell source for drug discovery, disease modeling, and cardiac regenerative therapy.” (p. 354) [Annotation for the previous sentence: The significance or implications—for drug discovery, disease modeling, and therapy—of this reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-3.png)

Sample Abstract 4, a Structured Abstract

Reporting results about the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis, from a rigorously controlled study

Note: This journal requires authors to organize their abstract into four specific sections, with strict word limits. Because the headings for this structured abstract are self-explanatory, we have chosen not to add annotations to this sample abstract.

Wald, Ellen R., David Nash, and Jens Eickhoff. “Effectiveness of Amoxicillin/Clavulanate Potassium in the Treatment of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis in Children.” Pediatrics , vol. 124, no. 1, 2009, pp. 9-15.

“OBJECTIVE: The role of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis (ABS) in children is controversial. The purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of high-dose amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate in the treatment of children diagnosed with ABS.

METHODS : This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Children 1 to 10 years of age with a clinical presentation compatible with ABS were eligible for participation. Patients were stratified according to age (<6 or ≥6 years) and clinical severity and randomly assigned to receive either amoxicillin (90 mg/kg) with potassium clavulanate (6.4 mg/kg) or placebo. A symptom survey was performed on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 20, and 30. Patients were examined on day 14. Children’s conditions were rated as cured, improved, or failed according to scoring rules.

RESULTS: Two thousand one hundred thirty-five children with respiratory complaints were screened for enrollment; 139 (6.5%) had ABS. Fifty-eight patients were enrolled, and 56 were randomly assigned. The mean age was 6630 months. Fifty (89%) patients presented with persistent symptoms, and 6 (11%) presented with nonpersistent symptoms. In 24 (43%) children, the illness was classified as mild, whereas in the remaining 32 (57%) children it was severe. Of the 28 children who received the antibiotic, 14 (50%) were cured, 4 (14%) were improved, 4(14%) experienced treatment failure, and 6 (21%) withdrew. Of the 28children who received placebo, 4 (14%) were cured, 5 (18%) improved, and 19 (68%) experienced treatment failure. Children receiving the antibiotic were more likely to be cured (50% vs 14%) and less likely to have treatment failure (14% vs 68%) than children receiving the placebo.

CONCLUSIONS : ABS is a common complication of viral upper respiratory infections. Amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate results in significantly more cures and fewer failures than placebo, according to parental report of time to resolution.” (9)

Some Excellent Advice about Writing Abstracts for Basic Science Research Papers, by Professor Adriano Aguzzi from the Institute of Neuropathology at the University of Zurich:

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

Generate accurate APA citations for free

- Knowledge Base

- APA Style 7th edition

- How to write and format an APA abstract

APA Abstract (2020) | Formatting, Length, and Keywords

Published on November 6, 2020 by Raimo Streefkerk . Revised on January 17, 2024.

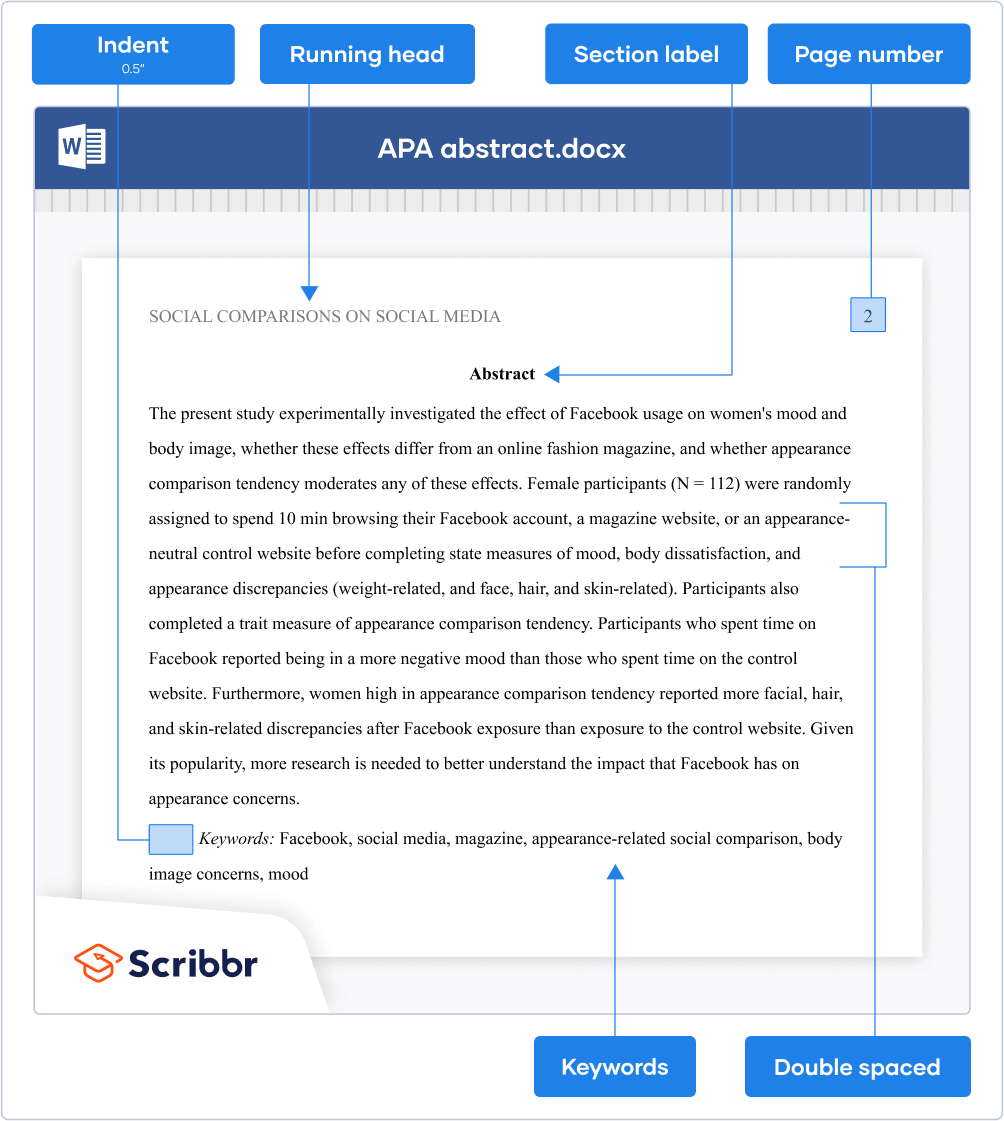

An APA abstract is a comprehensive summary of your paper in which you briefly address the research problem , hypotheses , methods , results , and implications of your research. It’s placed on a separate page right after the title page and is usually no longer than 250 words.

Most professional papers that are submitted for publication require an abstract. Student papers typically don’t need an abstract, unless instructed otherwise.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

How to format the abstract, how to write an apa abstract, which keywords to use, frequently asked questions, apa abstract example.

Formatting instructions

Follow these five steps to format your abstract in APA Style:

- Insert a running head (for a professional paper—not needed for a student paper) and page number.

- Set page margins to 1 inch (2.54 cm).

- Write “Abstract” (bold and centered) at the top of the page.

- Do not indent the first line.

- Double-space the text.

- Use a legible font like Times New Roman (12 pt.).

- Limit the length to 250 words.

- Indent the first line 0.5 inches.

- Write the label “Keywords:” (italicized).

- Write keywords in lowercase letters.

- Separate keywords with commas.

- Do not use a period after the keywords.

Are your APA in-text citations flawless?

The AI-powered APA Citation Checker points out every error, tells you exactly what’s wrong, and explains how to fix it. Say goodbye to losing marks on your assignment!

Get started!

The abstract is a self-contained piece of text that informs the reader what your research is about. It’s best to write the abstract after you’re finished with the rest of your paper.

The questions below may help structure your abstract. Try answering them in one to three sentences each.

- What is the problem? Outline the objective, research questions , and/or hypotheses .

- What has been done? Explain your research methods .

- What did you discover? Summarize the key findings and conclusions .

- What do the findings mean? Summarize the discussion and recommendations .

Check out our guide on how to write an abstract for more guidance and an annotated example.

Guide: writing an abstract

At the end of the abstract, you may include a few keywords that will be used for indexing if your paper is published on a database. Listing your keywords will help other researchers find your work.

Choosing relevant keywords is essential. Try to identify keywords that address your topic, method, or population. APA recommends including three to five keywords.

An abstract is a concise summary of an academic text (such as a journal article or dissertation ). It serves two main purposes:

- To help potential readers determine the relevance of your paper for their own research.

- To communicate your key findings to those who don’t have time to read the whole paper.

Abstracts are often indexed along with keywords on academic databases, so they make your work more easily findable. Since the abstract is the first thing any reader sees, it’s important that it clearly and accurately summarizes the contents of your paper.

An APA abstract is around 150–250 words long. However, always check your target journal’s guidelines and don’t exceed the specified word count.

In an APA Style paper , the abstract is placed on a separate page after the title page (page 2).

Avoid citing sources in your abstract . There are two reasons for this:

- The abstract should focus on your original research, not on the work of others.

- The abstract should be self-contained and fully understandable without reference to other sources.

There are some circumstances where you might need to mention other sources in an abstract: for example, if your research responds directly to another study or focuses on the work of a single theorist. In general, though, don’t include citations unless absolutely necessary.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Streefkerk, R. (2024, January 17). APA Abstract (2020) | Formatting, Length, and Keywords. Scribbr. Retrieved March 22, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/apa-style/apa-abstract/

Is this article helpful?

Raimo Streefkerk

Other students also liked, apa headings and subheadings, apa running head, apa title page (7th edition) | template for students & professionals, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 3. The Abstract

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

An abstract summarizes, usually in one paragraph of 300 words or less, the major aspects of the entire paper in a prescribed sequence that includes: 1) the overall purpose of the study and the research problem(s) you investigated; 2) the basic design of the study; 3) major findings or trends found as a result of your analysis; and, 4) a brief summary of your interpretations and conclusions.

Writing an Abstract. The Writing Center. Clarion University, 2009; Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper. The Writing Center, University of Wisconsin, Madison; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-first Century . Oxford, UK: Chandos Publishing, 2010;

Importance of a Good Abstract

Sometimes your professor will ask you to include an abstract, or general summary of your work, with your research paper. The abstract allows you to elaborate upon each major aspect of the paper and helps readers decide whether they want to read the rest of the paper. Therefore, enough key information [e.g., summary results, observations, trends, etc.] must be included to make the abstract useful to someone who may want to examine your work.

How do you know when you have enough information in your abstract? A simple rule-of-thumb is to imagine that you are another researcher doing a similar study. Then ask yourself: if your abstract was the only part of the paper you could access, would you be happy with the amount of information presented there? Does it tell the whole story about your study? If the answer is "no" then the abstract likely needs to be revised.

Farkas, David K. “A Scheme for Understanding and Writing Summaries.” Technical Communication 67 (August 2020): 45-60; How to Write a Research Abstract. Office of Undergraduate Research. University of Kentucky; Staiger, David L. “What Today’s Students Need to Know about Writing Abstracts.” International Journal of Business Communication January 3 (1966): 29-33; Swales, John M. and Christine B. Feak. Abstracts and the Writing of Abstracts . Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2009.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Types of Abstracts

To begin, you need to determine which type of abstract you should include with your paper. There are four general types.

Critical Abstract A critical abstract provides, in addition to describing main findings and information, a judgment or comment about the study’s validity, reliability, or completeness. The researcher evaluates the paper and often compares it with other works on the same subject. Critical abstracts are generally 400-500 words in length due to the additional interpretive commentary. These types of abstracts are used infrequently.

Descriptive Abstract A descriptive abstract indicates the type of information found in the work. It makes no judgments about the work, nor does it provide results or conclusions of the research. It does incorporate key words found in the text and may include the purpose, methods, and scope of the research. Essentially, the descriptive abstract only describes the work being summarized. Some researchers consider it an outline of the work, rather than a summary. Descriptive abstracts are usually very short, 100 words or less. Informative Abstract The majority of abstracts are informative. While they still do not critique or evaluate a work, they do more than describe it. A good informative abstract acts as a surrogate for the work itself. That is, the researcher presents and explains all the main arguments and the important results and evidence in the paper. An informative abstract includes the information that can be found in a descriptive abstract [purpose, methods, scope] but it also includes the results and conclusions of the research and the recommendations of the author. The length varies according to discipline, but an informative abstract is usually no more than 300 words in length.

Highlight Abstract A highlight abstract is specifically written to attract the reader’s attention to the study. No pretense is made of there being either a balanced or complete picture of the paper and, in fact, incomplete and leading remarks may be used to spark the reader’s interest. In that a highlight abstract cannot stand independent of its associated article, it is not a true abstract and, therefore, rarely used in academic writing.

II. Writing Style

Use the active voice when possible , but note that much of your abstract may require passive sentence constructions. Regardless, write your abstract using concise, but complete, sentences. Get to the point quickly and always use the past tense because you are reporting on a study that has been completed.

Abstracts should be formatted as a single paragraph in a block format and with no paragraph indentations. In most cases, the abstract page immediately follows the title page. Do not number the page. Rules set forth in writing manual vary but, in general, you should center the word "Abstract" at the top of the page with double spacing between the heading and the abstract. The final sentences of an abstract concisely summarize your study’s conclusions, implications, or applications to practice and, if appropriate, can be followed by a statement about the need for additional research revealed from the findings.

Composing Your Abstract

Although it is the first section of your paper, the abstract should be written last since it will summarize the contents of your entire paper. A good strategy to begin composing your abstract is to take whole sentences or key phrases from each section of the paper and put them in a sequence that summarizes the contents. Then revise or add connecting phrases or words to make the narrative flow clearly and smoothly. Note that statistical findings should be reported parenthetically [i.e., written in parentheses].

Before handing in your final paper, check to make sure that the information in the abstract completely agrees with what you have written in the paper. Think of the abstract as a sequential set of complete sentences describing the most crucial information using the fewest necessary words. The abstract SHOULD NOT contain:

- A catchy introductory phrase, provocative quote, or other device to grab the reader's attention,

- Lengthy background or contextual information,

- Redundant phrases, unnecessary adverbs and adjectives, and repetitive information;

- Acronyms or abbreviations,

- References to other literature [say something like, "current research shows that..." or "studies have indicated..."],

- Using ellipticals [i.e., ending with "..."] or incomplete sentences,

- Jargon or terms that may be confusing to the reader,

- Citations to other works, and

- Any sort of image, illustration, figure, or table, or references to them.

Abstract. Writing Center. University of Kansas; Abstract. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Abstracts. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Borko, Harold and Seymour Chatman. "Criteria for Acceptable Abstracts: A Survey of Abstracters' Instructions." American Documentation 14 (April 1963): 149-160; Abstracts. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Hartley, James and Lucy Betts. "Common Weaknesses in Traditional Abstracts in the Social Sciences." Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 60 (October 2009): 2010-2018; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-first Century. Oxford, UK: Chandos Publishing, 2010; Procter, Margaret. The Abstract. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Riordan, Laura. “Mastering the Art of Abstracts.” The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 115 (January 2015 ): 41-47; Writing Report Abstracts. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing Abstracts. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-First Century . Oxford, UK: 2010; Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper. The Writing Center, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Writing Tip

Never Cite Just the Abstract!

Citing to just a journal article's abstract does not confirm for the reader that you have conducted a thorough or reliable review of the literature. If the full-text is not available, go to the USC Libraries main page and enter the title of the article [NOT the title of the journal]. If the Libraries have a subscription to the journal, the article should appear with a link to the full-text or to the journal publisher page where you can get the article. If the article does not appear, try searching Google Scholar using the link on the USC Libraries main page. If you still can't find the article after doing this, contact a librarian or you can request it from our free i nterlibrary loan and document delivery service .

- << Previous: Research Process Video Series

- Next: Executive Summary >>

- Last Updated: Mar 21, 2024 9:59 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

How to Write an Abstract APA Format

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

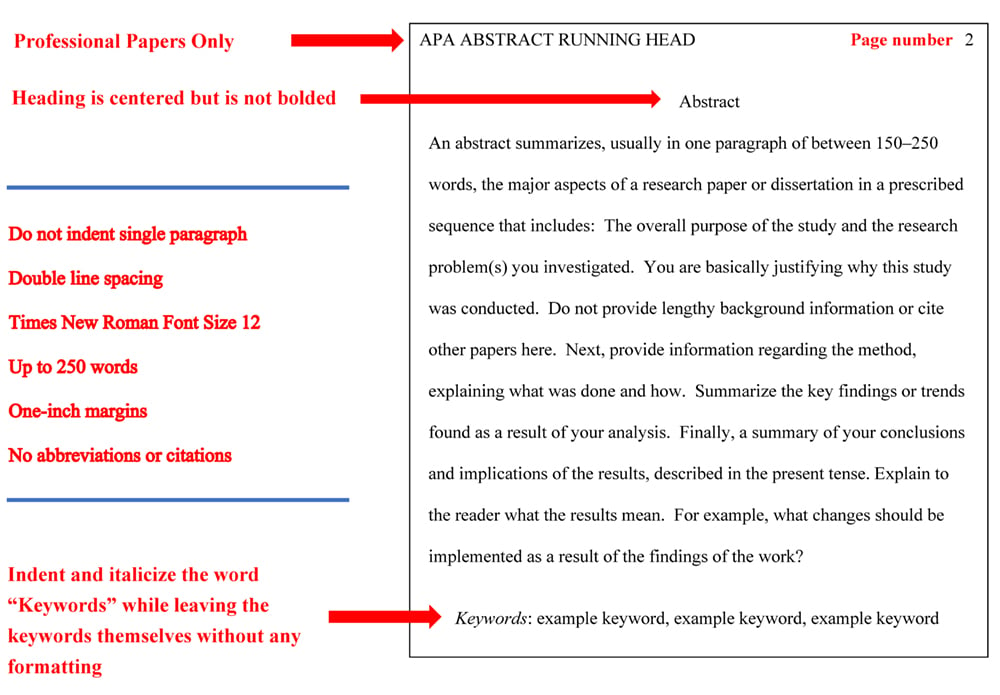

An APA abstract is a brief, comprehensive summary of the contents of an article, research paper, dissertation, or report.

It is written in accordance with the guidelines of the American Psychological Association (APA), which is a widely used format in social and behavioral sciences.

An APA abstract summarizes, usually in one paragraph of between 150–250 words, the major aspects of a research paper or dissertation in a prescribed sequence that includes:

- The rationale: the overall purpose of the study, providing a clear context for the research undertaken.

- Information regarding the method and participants: including materials/instruments, design, procedure, and data analysis.

- Main findings or trends: effectively highlighting the key outcomes of the hypotheses.

- Interpretations and conclusion(s): solidify the implications of the research.

- Keywords related to the study: assist the paper’s discoverability in academic databases.

The abstract should stand alone, be “self-contained,” and make sense to the reader in isolation from the main article.

The purpose of the abstract is to give the reader a quick overview of the essential information before reading the entire article. The abstract is placed on its own page, directly after the title page and before the main body of the paper.

Although the abstract will appear as the very first part of your paper, it’s good practice to write your abstract after you’ve drafted your full paper, so that you know what you’re summarizing.

Note : This page reflects the latest version of the APA Publication Manual (i.e., APA 7), released in October 2019.

Structure of the Abstract

[NOTE: DO NOT separate the components of the abstract – it should be written as a single paragraph. This section is separated to illustrate the abstract’s structure.]

1) The Rationale

One or two sentences describing the overall purpose of the study and the research problem(s) you investigated. You are basically justifying why this study was conducted.

- What is the importance of the research?

- Why would a reader be interested in the larger work?

- For example, are you filling a gap in previous research or applying new methods to take a fresh look at existing ideas or data?

- Women who are diagnosed with breast cancer can experience an array of psychosocial difficulties; however, social support, particularly from a spouse, has been shown to have a protective function during this time. This study examined the ways in which a woman’s daily mood, pain, and fatigue, and her spouse’s marital satisfaction predict the woman’s report of partner support in the context of breast cancer.

- The current nursing shortage, high hospital nurse job dissatisfaction, and reports of uneven quality of hospital care are not uniquely American phenomena.

- Students with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) are more likely to exhibit behavioral difficulties than their typically developing peers. The aim of this study was to identify specific risk factors that influence variability in behavior difficulties among individuals with SEND.

2) The Method

Information regarding the participants (number, and population). One or two sentences outlining the method, explaining what was done and how. The method is described in the present tense.

- Pretest data from a larger intervention study and multilevel modeling were used to examine the effects of women’s daily mood, pain, and fatigue and average levels of mood, pain, and fatigue on women’s report of social support received from her partner, as well as how the effects of mood interacted with partners’ marital satisfaction.

- This paper presents reports from 43,000 nurses from more than 700 hospitals in the United States, Canada, England, Scotland, and Germany in 1998–1999.

- The study sample comprised 4,228 students with SEND, aged 5–15, drawn from 305 primary and secondary schools across England. Explanatory variables were measured at the individual and school levels at baseline, along with a teacher-reported measure of behavior difficulties (assessed at baseline and the 18-month follow-up).

3) The Results

One or two sentences indicating the main findings or trends found as a result of your analysis. The results are described in the present or past tense.

- Results show that on days in which women reported higher levels of negative or positive mood, as well as on days they reported more pain and fatigue, they reported receiving more support. Women who, on average, reported higher levels of positive mood tended to report receiving more support than those who, on average, reported lower positive mood. However, average levels of negative mood were not associated with support. Higher average levels of fatigue but not pain were associated with higher support. Finally, women whose husbands reported higher levels of marital satisfaction reported receiving more partner support, but husbands’ marital satisfaction did not moderate the effect of women’s mood on support.

- Nurses in countries with distinctly different healthcare systems report similar shortcomings in their work environments and the quality of hospital care. While the competence of and relation between nurses and physicians appear satisfactory, core problems in work design and workforce management threaten the provision of care.

- Hierarchical linear modeling of data revealed that differences between schools accounted for between 13% (secondary) and 15.4% (primary) of the total variance in the development of students’ behavior difficulties, with the remainder attributable to individual differences. Statistically significant risk markers for these problems across both phases of education were being male, eligibility for free school meals, being identified as a bully, and lower academic achievement. Additional risk markers specific to each phase of education at the individual and school levels are also acknowledged.

4) The Conclusion / Implications

A brief summary of your conclusions and implications of the results, described in the present tense. Explain the results and why the study is important to the reader.

- For example, what changes should be implemented as a result of the findings of the work?

- How does this work add to the body of knowledge on the topic?

Implications of these findings are discussed relative to assisting couples during this difficult time in their lives.

- Resolving these issues, which are amenable to managerial intervention, is essential to preserving patient safety and care of consistently high quality.

- Behavior difficulties are affected by risks across multiple ecological levels. Addressing any one of these potential influences is therefore likely to contribute to the reduction in the problems displayed.

The above examples of abstracts are from the following papers:

Aiken, L. H., Clarke, S. P., Sloane, D. M., Sochalski, J. A., Busse, R., Clarke, H., … & Shamian, J. (2001). Nurses’ reports on hospital care in five countries . Health affairs, 20(3) , 43-53.

Boeding, S. E., Pukay-Martin, N. D., Baucom, D. H., Porter, L. S., Kirby, J. S., Gremore, T. M., & Keefe, F. J. (2014). Couples and breast cancer: Women’s mood and partners’ marital satisfaction predicting support perception . Journal of Family Psychology, 28(5) , 675.

Oldfield, J., Humphrey, N., & Hebron, J. (2017). Risk factors in the development of behavior difficulties among students with special educational needs and disabilities: A multilevel analysis . British journal of educational psychology, 87(2) , 146-169.

5) Keywords

APA style suggests including a list of keywords at the end of the abstract. This is particularly common in academic articles and helps other researchers find your work in databases.

Keywords in an abstract should be selected to help other researchers find your work when searching an online database. These keywords should effectively represent the main topics of your study. Here are some tips for choosing keywords:

Core Concepts: Identify the most important ideas or concepts in your paper. These often include your main research topic, the methods you’ve used, or the theories you’re discussing.

Specificity: Your keywords should be specific to your research. For example, suppose your paper is about the effects of climate change on bird migration patterns in a specific region. In that case, your keywords might include “climate change,” “bird migration,” and the region’s name.

Consistency with Paper: Make sure your keywords are consistent with the terms you’ve used in your paper. For example, if you use the term “adolescent” rather than “teen” in your paper, choose “adolescent” as your keyword, not “teen.”

Jargon and Acronyms: Avoid using too much-specialized jargon or acronyms in your keywords, as these might not be understood or used by all researchers in your field.

Synonyms: Consider including synonyms of your keywords to capture as many relevant searches as possible. For example, if your paper discusses “post-traumatic stress disorder,” you might include “PTSD” as a keyword.

Remember, keywords are a tool for others to find your work, so think about what terms other researchers might use when searching for papers on your topic.

The Abstract SHOULD NOT contain:

Lengthy background or contextual information: The abstract should focus on your research and findings, not general topic background.

Undefined jargon, abbreviations, or acronyms: The abstract should be accessible to a wide audience, so avoid highly specialized terms without defining them.

Citations: Abstracts typically do not include citations, as they summarize original research.

Incomplete sentences or bulleted lists: The abstract should be a single, coherent paragraph written in complete sentences.

New information not covered in the paper: The abstract should only summarize the paper’s content.

Subjective comments or value judgments: Stick to objective descriptions of your research.

Excessive details on methods or procedures: Keep descriptions of methods brief and focused on main steps.

Speculative or inconclusive statements: The abstract should state the research’s clear findings, not hypotheses or possible interpretations.

- Any illustration, figure, table, or references to them . All visual aids, data, or extensive details should be included in the main body of your paper, not in the abstract.

- Elliptical or incomplete sentences should be avoided in an abstract . The use of ellipses (…), which could indicate incomplete thoughts or omitted text, is not appropriate in an abstract.

APA Style for Abstracts

An APA abstract must be formatted as follows:

Include the running head aligned to the left at the top of the page (professional papers only) and page number. Note, student papers do not require a running head. On the first line, center the heading “Abstract” and bold (do not underlined or italicize). Do not indent the single abstract paragraph (which begins one line below the section title). Double-space the text. Use Times New Roman font in 12 pt. Set one-inch (or 2.54 cm) margins. If you include a “keywords” section at the end of the abstract, indent the first line and italicize the word “Keywords” while leaving the keywords themselves without any formatting.

Example APA Abstract Page

Download this example as a PDF

Further Information

- APA 7th Edition Abstract and Keywords Guide

- Example APA Abstract

- How to Write a Good Abstract for a Scientific Paper or Conference Presentation

- How to Write a Lab Report

- Writing an APA paper

How long should an APA abstract be?

An APA abstract should typically be between 150 to 250 words long. However, the exact length may vary depending on specific publication or assignment guidelines. It is crucial that it succinctly summarizes the essential elements of the work, including purpose, methods, findings, and conclusions.

Where does the abstract go in an APA paper?

In an APA formatted paper, the abstract is placed on its own page, directly after the title page and before the main body of the paper. It’s typically the second page of the document. It starts with the word “Abstract” (centered and not in bold) at the top of the page, followed by the text of the abstract itself.

What are the 4 C’s of abstract writing?

The 4 C’s of abstract writing are an approach to help you create a well-structured and informative abstract. They are:

Conciseness: An abstract should briefly summarize the key points of your study. Stick to the word limit (typically between 150-250 words for an APA abstract) and avoid unnecessary details.

Clarity: Your abstract should be easy to understand. Avoid jargon and complex sentences. Clearly explain the purpose, methods, results, and conclusions of your study.

Completeness: Even though it’s brief, the abstract should provide a complete overview of your study, including the purpose, methods, key findings, and your interpretation of the results.

Cohesion: The abstract should flow logically from one point to the next, maintaining a coherent narrative about your study. It’s not just a list of disjointed elements; it’s a brief story of your research from start to finish.

What is the abstract of a psychology paper?

An abstract in a psychology paper serves as a snapshot of the paper, allowing readers to quickly understand the purpose, methodology, results, and implications of the research without reading the entire paper. It is generally between 150-250 words long.

Undergraduate Research Center

The following instructions are for the Undergraduate Research Center's Undergraduate Research, Scholarship and Creative Activities Conference, however the general concepts will apply to abstracts for similar conferences. In the video to the right, Kendon Kurzer, PhD presents guidance from the University Writing Program. To see abstracts from previous URC Conferences, visit our Abstract Books Page .

What is an abstract?

An abstract is a summary of a research project. Abstracts precede papers in research journals and appear in programs of scholarly conferences. In journals, the abstract allows readers to quickly grasp the purpose and major ideas of a paper and lets other researchers know whether reading the entire paper will be worthwhile. In conferences, the abstract is the advertisement that the paper/presentation deserves the audience's attention.

Why write an abstract?

The abstract allows readers to make decisions about your project. Your sponsoring professor can use the abstract to decide if your research is proceeding smoothly. The conference organizer uses it to decide if your project fits the conference criteria. The conference audience (faculty, administrators, peers, and presenters' families) uses your abstract to decide whether or not to attend your presentation. Your abstract needs to take all these readers into consideration.

How does an abstract appeal to such a broad audience?

The audience for the abstract for the Undergraduate Research, Scholarship and Creative Activities Conference (URSCA) covers the broadest possible scope--from expert to lay person. You need to find a comfortable balance between writing an abstract that both shows your knowledge and yet is still comprehensible--with some effort--by lay members of the audience. Limit the amount of technical language you use and explain it where possible. Always use the full term before you refer to it by acronym Example: DNA double-stranded breaks (DSBs). Remember that you are yourself an expert in the field that you are writing about--don't take for granted that the reader will share your insider knowledge.

What should the abstract include?

Think of your abstract as a condensed version of your whole project. By reading it, the reader should understand the nature of your research question.

Like abstracts that researchers prepare for scholarly conferences, the abstract you submit for the Undergraduate Research, Scholarship and Creativities Conference (URSCA) will most likely reflect work still in progress at the time you write it. Although the content will vary according to field and specific project, all abstracts, whether in the sciences or the humanities, convey the following information:

- The purpose of the project identifying the area of study to which it belongs.

- The research problem that motivates the project.

- The methods used to address this research problem, documents or evidence analyzed.

- The conclusions reached or, if the research is in progress, what the preliminary results of the investigation suggest, or what the research methods demonstrate.

- The significance of the research project. Why are the results useful? What is new to our understanding as the result of your inquiry?

Whatever kind of research you are doing, your abstract should provide the reader with answers to the following questions: What are you asking? Why is it important? How will you study it? What will you use to demonstrate your conclusions? What are those conclusions? What do they mean?

SUGGESTED CONTENT STRUCTURE:

Brief Background/Introduction/Research Context: What do we know about the topic? Why is the topic important? Present Research Question/Purpose: What is the study about? Methods/Materials/Subjects/Materials: How was the study done? Results/Findings: What was discovered? Discussion/Conclusion/Implications/Recommendations What does it mean?

What if the research is in progress and I don't have results yet?

For the URSCA Conference you can write a "Promissory Abstract" which will still describe the background, purpose and how you will accomplish your study's purpose and why it is important. Phrases like "to show whether" or "to determine if" can be helpful to avoid sharing a "hoped for" result.

Stylistic considerations

The abstract should be one paragraph for the URSCA Conference and should not exceed the word limit (150-200 words). Edit it closely to be sure it meets the Four C's of abstract writing:

- Complete — it covers the major parts of the project.

- Concise — it contains no excess wordiness or unnecessary information.

- Clear — it is readable, well organized, and not too jargon-laden.

- Cohesive — it flows smoothly between the parts.

The importance of understandable language

Because all researchers hope their work will be useful to others, and because good scholarship is increasingly used across disciplines, it is crucial to make the language of your abstracts accessible to a non-specialist. Simplify your language. Friends in another major will spot instantly what needs to be more understandable. Some problem areas to look for:

- Eliminate jargon. Showing off your technical vocabulary will not demonstrate that your research is valuable. If using a technical term is unavoidable, add a non-technical synonym to help a non-specialist infer the term's meaning.

- Omit needless words—redundant modifiers, pompous diction, excessive detail.

- Avoid stringing nouns together (make the relationship clear with prepositions).

- Eliminate "narration," expressions such as "It is my opinion that," "I have concluded," "the main point supporting my view/concerns," or "certainly there is little doubt as to. . . ." Focus attention solely on what the reader needs to know.

Before submitting your abstract to the URSCA Conference:

- Make sure it is within the word limit. You can start with a large draft and then edit it down to make sure your abstract is complete but also concise. (Over-writing is all too easy, so reserve time for cutting your abstract down to the essential information.).

- Make sure the language is understandable by a non-specialist. (Avoid writing for an audience that includes only you and your professor.)

- Have your sponsoring professor work with you and approve the abstract before you submit it online.

- Only one abstract per person is allowed for the URSCA Conference.

Multimedia Risk Assessment of Biodiesel - Tier II Antfarm Project

Significant knowledge gaps exist in the fate, transport, biodegradation, and toxicity properties of biodiesel when it is leaked into the environment. In order to fill these gaps, a combination of experiments has been developed in a Multimedia Risk Assessment of Biodiesel for the State of California. Currently, in the Tier II experimental phase of this assessment, I am investigating underground plume mobility of 20% and 100% additized and unadditized Soy and Animal Fat based biodiesel blends and comparing them to Ultra Low-Sulfer Diesel #2 (USLD) by filming these fuels as they seep through unsaturated sand, encounter a simulated underground water table, and form a floating lens on top of the water. Thus far, initial findings in analyzing the digital images created during the filming process have indicated that all fuels tested have similar travel times. SoyB20 behaves most like USLD in that they both have a similar lateral dispersion lens on top of the water table. In contrast, Animal Fat B100 appears to be most different from ULSD in that it has a narrower residual plume in the unsaturated sand, as well as a narrower and deeper lens formation on top of the water table.

Narrative Representation of Grief

In William Faulkner's As I Lay Dying and Kazuo Ishiguro's Never Let Me Go how can grief, an incomprehensible and incommunicable emotion, be represented in fiction? Is it paradoxical, or futile, to do so? I look at two novels that struggle with representing intense combinations of individual and communal grief: William Faulkner's As I Lay Dying and Kazuo Ishiguro's Never Let Me Go . At first glance, the novels appear to have nothing in common: Faulkner's is a notoriously bleak odyssey told in emotionally heavy stream-of-consciousness narrative, while Ishiguro's is a near-kitschy blend of a coming-of-age tale and a sci-fi dystopia. But they share a rare common thread. They do not try to convey a story, a character, an argument, or a realization, so much as they try to convey an emotion. The novels' common struggle is visible through their formal elements, down to the most basic technical aspects of how the stories are told. Each text, in its own way, enacts the trauma felt by its characters because of their grief, and also the frustration felt by its narrator (or narrators) because of the complex and guilty task of witnessing for grief and loss.

This webpage was based on articles written by Professor Diana Strazdes, Art History and Dr. Amy Clarke, University Writing Program, UC Davis. Thanks to both for their contributions.

The Dissertation Abstract: 101

How to write a clear & concise abstract (with examples).

By: Madeline Fink (MSc) Reviewed By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | June 2020

So, you’ve (finally) finished your thesis or dissertation or thesis. Now it’s time to write up your abstract (sometimes also called the executive summary). If you’re here, chances are you’re not quite sure what you need to cover in this section, or how to go about writing it. Fear not – we’ll explain it all in plain language , step by step , with clear examples .

Overview: The Dissertation/Thesis Abstract

- What exactly is a dissertation (or thesis) abstract

- What’s the purpose and function of the abstract

- Why is the abstract so important

- How to write a high-quality dissertation abstract

- Example/sample of a quality abstract

- Quick tips to write a high-quality dissertation abstract

What is an abstract?

Simply put, the abstract in a dissertation or thesis is a short (but well structured) summary that outlines the most important points of your research (i.e. the key takeaways). The abstract is usually 1 paragraph or about 300-500 words long (about one page), but but this can vary between universities.

A quick note regarding terminology – strictly speaking, an abstract and an executive summary are two different things when it comes to academic publications. Typically, an abstract only states what the research will be about, but doesn’t explore the findings – whereas an executive summary covers both . However, in the context of a dissertation or thesis, the abstract usually covers both, providing a summary of the full project.

In terms of content, a good dissertation abstract usually covers the following points:

- The purpose of the research (what’s it about and why’s that important)

- The methodology (how you carried out the research)

- The key research findings (what answers you found)

- The implications of these findings (what these answers mean)

We’ll explain each of these in more detail a little later in this post. Buckle up.

What’s the purpose of the abstract?

A dissertation abstract has two main functions:

The first purpose is to inform potential readers of the main idea of your research without them having to read your entire piece of work. Specifically, it needs to communicate what your research is about (what were you trying to find out) and what your findings were . When readers are deciding whether to read your dissertation or thesis, the abstract is the first part they’ll consider.

The second purpose of the abstract is to inform search engines and dissertation databases as they index your dissertation or thesis. The keywords and phrases in your abstract (as well as your keyword list) will often be used by these search engines to categorize your work and make it accessible to users.

Simply put, your abstract is your shopfront display window – it’s what passers-by (both human and digital) will look at before deciding to step inside.

Why’s it so important?

The short answer – because most people don’t have time to read your full dissertation or thesis! Time is money, after all…

If you think back to when you undertook your literature review , you’ll quickly realise just how important abstracts are! Researchers reviewing the literature on any given topic face a mountain of reading, so they need to optimise their approach. A good dissertation abstract gives the reader a “TLDR” version of your work – it helps them decide whether to continue to read it in its entirety. So, your abstract, as your shopfront display window, needs to “sell” your research to time-poor readers.

You might be thinking, “but I don’t plan to publish my dissertation”. Even so, you still need to provide an impactful abstract for your markers. Your ability to concisely summarise your work is one of the things they’re assessing, so it’s vital to invest time and effort into crafting an enticing shop window.

A good abstract also has an added purpose for grad students . As a freshly minted graduate, your dissertation or thesis is often your most significant professional accomplishment and highlights where your unique expertise lies. Potential employers who want to know about this expertise are likely to only read the abstract (as opposed to reading your entire document) – so it needs to be good!

Think about it this way – if your thesis or dissertation were a book, then the abstract would be the blurb on the back cover. For better or worse, readers will absolutely judge your book by its cover .

How to write your abstract

As we touched on earlier, your abstract should cover four important aspects of your research: the purpose , methodology , findings , and implications . Therefore, the structure of your dissertation or thesis abstract needs to reflect these four essentials, in the same order. Let’s take a closer look at each of them, step by step:

Step 1: Describe the purpose and value of your research

Here you need to concisely explain the purpose and value of your research. In other words, you need to explain what your research set out to discover and why that’s important. When stating the purpose of research, you need to clearly discuss the following:

- What were your research aims and research questions ?

- Why were these aims and questions important?

It’s essential to make this section extremely clear, concise and convincing . As the opening section, this is where you’ll “hook” your reader (marker) in and get them interested in your project. If you don’t put in the effort here, you’ll likely lose their interest.

Step 2: Briefly outline your study’s methodology

In this part of your abstract, you need to very briefly explain how you went about answering your research questions . In other words, what research design and methodology you adopted in your research. Some important questions to address here include:

- Did you take a qualitative or quantitative approach ?

- Who/what did your sample consist of?

- How did you collect your data?

- How did you analyse your data?

Simply put, this section needs to address the “ how ” of your research. It doesn’t need to be lengthy (this is just a summary, after all), but it should clearly address the four questions above.

Need a helping hand?

Step 3: Present your key findings

Next, you need to briefly highlight the key findings . Your research likely produced a wealth of data and findings, so there may be a temptation to ramble here. However, this section is just about the key findings – in other words, the answers to the original questions that you set out to address.

Again, brevity and clarity are important here. You need to concisely present the most important findings for your reader.

Step 4: Describe the implications of your research

Have you ever found yourself reading through a large report, struggling to figure out what all the findings mean in terms of the bigger picture? Well, that’s the purpose of the implications section – to highlight the “so what?” of your research.

In this part of your abstract, you should address the following questions:

- What is the impact of your research findings on the industry /field investigated? In other words, what’s the impact on the “real world”.

- What is the impact of your findings on the existing body of knowledge ? For example, do they support the existing research?

- What might your findings mean for future research conducted on your topic?

If you include these four essential ingredients in your dissertation abstract, you’ll be on headed in a good direction.

Example: Dissertation/thesis abstract

Here is an example of an abstract from a master’s thesis, with the purpose , methods , findings , and implications colour coded.

The U.S. citizenship application process is a legal and symbolic journey shaped by many cultural processes. This research project aims to bring to light the experiences of immigrants and citizenship applicants living in Dallas, Texas, to promote a better understanding of Dallas’ increasingly diverse population. Additionally, the purpose of this project is to provide insights to a specific client, the office of Dallas Welcoming Communities and Immigrant Affairs, about Dallas’ lawful permanent residents who are eligible for citizenship and their reasons for pursuing citizenship status . The data for this project was collected through observation at various citizenship workshops and community events, as well as through semi-structured interviews with 14 U.S. citizenship applicants . Reasons for applying for U.S. citizenship discussed in this project include a desire for membership in U.S. society, access to better educational and economic opportunities, improved ease of travel and the desire to vote. Barriers to the citizenship process discussed in this project include the amount of time one must dedicate to the application, lack of clear knowledge about the process and the financial cost of the application. Other themes include the effects of capital on applicant’s experience with the citizenship process, symbolic meanings of citizenship, transnationalism and ideas of deserving and undeserving surrounding the issues of residency and U.S. citizenship. These findings indicate the need for educational resources and mentorship for Dallas-area residents applying for U.S. citizenship, as well as a need for local government programs that foster a sense of community among citizenship applicants and their neighbours.

Practical tips for writing your abstract

When crafting the abstract for your dissertation or thesis, the most powerful technique you can use is to try and put yourself in the shoes of a potential reader. Assume the reader is not an expert in the field, but is interested in the research area. In other words, write for the intelligent layman, not for the seasoned topic expert.

Start by trying to answer the question “why should I read this dissertation?”

Remember the WWHS.

Make sure you include the what , why , how , and so what of your research in your abstract:

- What you studied (who and where are included in this part)

- Why the topic was important

- How you designed your study (i.e. your research methodology)

- So what were the big findings and implications of your research

Keep it simple.

Use terminology appropriate to your field of study, but don’t overload your abstract with big words and jargon that cloud the meaning and make your writing difficult to digest. A good abstract should appeal to all levels of potential readers and should be a (relatively) easy read. Remember, you need to write for the intelligent layman.

Be specific.

When writing your abstract, clearly outline your most important findings and insights and don’t worry about “giving away” too much about your research – there’s no need to withhold information. This is the one way your abstract is not like a blurb on the back of a book – the reader should be able to clearly understand the key takeaways of your thesis or dissertation after reading the abstract. Of course, if they then want more detail, they need to step into the restaurant and try out the menu.

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

You Might Also Like:

17 Comments

This was so very useful, thank you Caroline.

Much appreciated.

This information on Abstract for writing a Dissertation was very helpful to me!

This was so useful. Thank you very much.

This was really useful in writing the abstract for my dissertation. Thank you Caroline.

Very clear and helpful information. Thanks so much!

Fabulous information – succinct, simple information which made my life easier after the most stressful and rewarding 21 months of completing this Masters Degree.

Very clear, specific and to the point guidance. Thanks a lot. Keep helping people 🙂

This was very helpful

Thanks for this nice and helping document.

Waw!!, this is a master piece to say the least.

Very helpful and enjoyable

Thank you for sharing the very important and usful information. Best Bahar

Very clear and more understandable way of writing. I am so interested in it. God bless you dearly!!!!

Really, I found the explanation given of great help. The way the information is presented is easy to follow and capture.

Wow! Thank you so much for opening my eyes. This was so helpful to me.

Thanks for this! Very concise and helpful for my ADHD brain.

I am so grateful for the tips. I am very optimistic in coming up with a winning abstract for my dessertation, thanks to you.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

Table of Contents

How To Write a Research Proposal

Writing a Research proposal involves several steps to ensure a well-structured and comprehensive document. Here is an explanation of each step:

1. Title and Abstract

- Choose a concise and descriptive title that reflects the essence of your research.

- Write an abstract summarizing your research question, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes. It should provide a brief overview of your proposal.

2. Introduction:

- Provide an introduction to your research topic, highlighting its significance and relevance.

- Clearly state the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Discuss the background and context of the study, including previous research in the field.

3. Research Objectives

- Outline the specific objectives or aims of your research. These objectives should be clear, achievable, and aligned with the research problem.

4. Literature Review:

- Conduct a comprehensive review of relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings, identify gaps, and highlight how your research will contribute to the existing knowledge.

5. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to employ to address your research objectives.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques you will use.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate and suitable for your research.

6. Timeline:

- Create a timeline or schedule that outlines the major milestones and activities of your research project.

- Break down the research process into smaller tasks and estimate the time required for each task.

7. Resources:

- Identify the resources needed for your research, such as access to specific databases, equipment, or funding.

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources to carry out your research effectively.

8. Ethical Considerations:

- Discuss any ethical issues that may arise during your research and explain how you plan to address them.