- Art Degrees

- Galleries & Exhibits

- Request More Info

Art History Resources

- Guidelines for Analysis of Art

- Formal Analysis Paper Examples

Guidelines for Writing Art History Research Papers

- Oral Report Guidelines

- Annual Arkansas College Art History Symposium

Writing a paper for an art history course is similar to the analytical, research-based papers that you may have written in English literature courses or history courses. Although art historical research and writing does include the analysis of written documents, there are distinctive differences between art history writing and other disciplines because the primary documents are works of art. A key reference guide for researching and analyzing works of art and for writing art history papers is the 10th edition (or later) of Sylvan Barnet’s work, A Short Guide to Writing about Art . Barnet directs students through the steps of thinking about a research topic, collecting information, and then writing and documenting a paper.

A website with helpful tips for writing art history papers is posted by the University of North Carolina.

Wesleyan University Writing Center has a useful guide for finding online writing resources.

The following are basic guidelines that you must use when documenting research papers for any art history class at UA Little Rock. Solid, thoughtful research and correct documentation of the sources used in this research (i.e., footnotes/endnotes, bibliography, and illustrations**) are essential. Additionally, these guidelines remind students about plagiarism, a serious academic offense.

Paper Format

Research papers should be in a 12-point font, double-spaced. Ample margins should be left for the instructor’s comments. All margins should be one inch to allow for comments. Number all pages. The cover sheet for the paper should include the following information: title of paper, your name, course title and number, course instructor, and date paper is submitted. A simple presentation of a paper is sufficient. Staple the pages together at the upper left or put them in a simple three-ring folder or binder. Do not put individual pages in plastic sleeves.

Documentation of Resources

The Chicago Manual of Style (CMS), as described in the most recent edition of Sylvan Barnet’s A Short Guide to Writing about Art is the department standard. Although you may have used MLA style for English papers or other disciplines, the Chicago Style is required for all students taking art history courses at UA Little Rock. There are significant differences between MLA style and Chicago Style. A “Quick Guide” for the Chicago Manual of Style footnote and bibliography format is found http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html. The footnote examples are numbered and the bibliography example is last. Please note that the place of publication and the publisher are enclosed in parentheses in the footnote, but they are not in parentheses in the bibliography. Examples of CMS for some types of note and bibliography references are given below in this Guideline. Arabic numbers are used for footnotes. Some word processing programs may have Roman numerals as a choice, but the standard is Arabic numbers. The use of super script numbers, as given in examples below, is the standard in UA Little Rock art history papers.

The chapter “Manuscript Form” in the Barnet book (10th edition or later) provides models for the correct forms for footnotes/endnotes and the bibliography. For example, the note form for the FIRST REFERENCE to a book with a single author is:

1 Bruce Cole, Italian Art 1250-1550 (New York: New York University Press, 1971), 134.

But the BIBLIOGRAPHIC FORM for that same book is:

Cole, Bruce. Italian Art 1250-1550. New York: New York University Press. 1971.

The FIRST REFERENCE to a journal article (in a periodical that is paginated by volume) with a single author in a footnote is:

2 Anne H. Van Buren, “Madame Cézanne’s Fashions and the Dates of Her Portraits,” Art Quarterly 29 (1966): 199.

The FIRST REFERENCE to a journal article (in a periodical that is paginated by volume) with a single author in the BIBLIOGRAPHY is:

Van Buren, Anne H. “Madame Cézanne’s Fashions and the Dates of Her Portraits.” Art Quarterly 29 (1966): 185-204.

If you reference an article that you found through an electronic database such as JSTOR, you do not include the url for JSTOR or the date accessed in either the footnote or the bibliography. This is because the article is one that was originally printed in a hard-copy journal; what you located through JSTOR is simply a copy of printed pages. Your citation follows the same format for an article in a bound volume that you may have pulled from the library shelves. If, however, you use an article that originally was in an electronic format and is available only on-line, then follow the “non-print” forms listed below.

B. Non-Print

Citations for Internet sources such as online journals or scholarly web sites should follow the form described in Barnet’s chapter, “Writing a Research Paper.” For example, the footnote or endnote reference given by Barnet for a web site is:

3 Nigel Strudwick, Egyptology Resources , with the assistance of The Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences, Cambridge University, 1994, revised 16 June 2008, http://www.newton.ac.uk/egypt/ , 24 July 2008.

If you use microform or microfilm resources, consult the most recent edition of Kate Turabian, A Manual of Term Paper, Theses and Dissertations. A copy of Turabian is available at the reference desk in the main library.

C. Visual Documentation (Illustrations)

Art history papers require visual documentation such as photographs, photocopies, or scanned images of the art works you discuss. In the chapter “Manuscript Form” in A Short Guide to Writing about Art, Barnet explains how to identify illustrations or “figures” in the text of your paper and how to caption the visual material. Each photograph, photocopy, or scanned image should appear on a single sheet of paper unless two images and their captions will fit on a single sheet of paper with one inch margins on all sides. Note also that the title of a work of art is always italicized. Within the text, the reference to the illustration is enclosed in parentheses and placed at the end of the sentence. A period for the sentence comes after the parenthetical reference to the illustration. For UA Little Rcok art history papers, illustrations are placed at the end of the paper, not within the text. Illustration are not supplied as a Powerpoint presentation or as separate .jpgs submitted in an electronic format.

Edvard Munch’s painting The Scream, dated 1893, represents a highly personal, expressive response to an experience the artist had while walking one evening (Figure 1).

The caption that accompanies the illustration at the end of the paper would read:

Figure 1. Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893. Tempera and casein on cardboard, 36 x 29″ (91.3 x 73.7 cm). Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo, Norway.

Plagiarism is a form of thievery and is illegal. According to Webster’s New World Dictionary, to plagiarize is to “take and pass off as one’s own the ideas, writings, etc. of another.” Barnet has some useful guidelines for acknowledging sources in his chapter “Manuscript Form;” review them so that you will not be mguilty of theft. Another useful website regarding plagiarism is provided by Cornell University, http://plagiarism.arts.cornell.edu/tutorial/index.cfm

Plagiarism is a serious offense, and students should understand that checking papers for plagiarized content is easy to do with Internet resources. Plagiarism will be reported as academic dishonesty to the Dean of Students; see Section VI of the Student Handbook which cites plagiarism as a specific violation. Take care that you fully and accurately acknowledge the source of another author, whether you are quoting the material verbatim or paraphrasing. Borrowing the idea of another author by merely changing some or even all of your source’s words does not allow you to claim the ideas as your own. You must credit both direct quotes and your paraphrases. Again, Barnet’s chapter “Manuscript Form” sets out clear guidelines for avoiding plagiarism.

VISIT OUR GALLERIES SEE UPCOMING EXHIBITS

- School of Art and Design

- Windgate Center of Art + Design, Room 202 2801 S University Avenue Little Rock , AR 72204

- Phone: 501-916-3182 Fax: 501-683-7022 (fax)

- More contact information

Connect With Us

UA Little Rock is an accredited member of the National Association of Schools of Art and Design.

Art History

What this handout is about.

This handout discusses a few common assignments found in art history courses. To help you better understand those assignments, this handout highlights key strategies for approaching and analyzing visual materials.

Writing in art history

Evaluating and writing about visual material uses many of the same analytical skills that you have learned from other fields, such as history or literature. In art history, however, you will be asked to gather your evidence from close observations of objects or images. Beyond painting, photography, and sculpture, you may be asked to write about posters, illustrations, coins, and other materials.

Even though art historians study a wide range of materials, there are a few prevalent assignments that show up throughout the field. Some of these assignments (and the writing strategies used to tackle them) are also used in other disciplines. In fact, you may use some of the approaches below to write about visual sources in classics, anthropology, and religious studies, to name a few examples.

This handout describes three basic assignment types and explains how you might approach writing for your art history class.Your assignment prompt can often be an important step in understanding your course’s approach to visual materials and meeting its specific expectations. Start by reading the prompt carefully, and see our handout on understanding assignments for some tips and tricks.

Three types of assignments are discussed below:

- Visual analysis essays

- Comparison essays

- Research papers

1. Visual analysis essays

Visual analysis essays often consist of two components. First, they include a thorough description of the selected object or image based on your observations. This description will serve as your “evidence” moving forward. Second, they include an interpretation or argument that is built on and defended by this visual evidence.

Formal analysis is one of the primary ways to develop your observations. Performing a formal analysis requires describing the “formal” qualities of the object or image that you are describing (“formal” here means “related to the form of the image,” not “fancy” or “please, wear a tuxedo”). Formal elements include everything from the overall composition to the use of line, color, and shape. This process often involves careful observations and critical questions about what you see.

Pre-writing: observations and note-taking

To assist you in this process, the chart below categorizes some of the most common formal elements. It also provides a few questions to get you thinking.

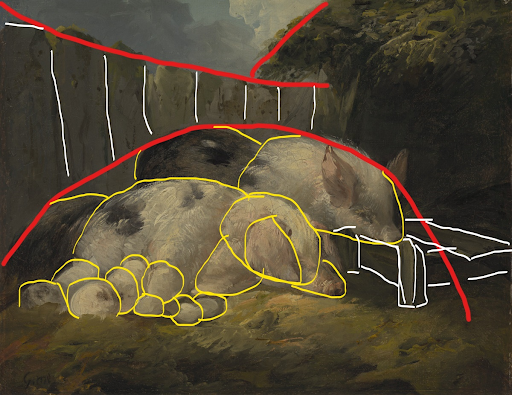

Let’s try this out with an example. You’ve been asked to write a formal analysis of the painting, George Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty , ca. 1800 (created in Britain and now in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond).

What do you notice when you see this image? First, you might observe that this is a painting. Next, you might ask yourself some of the following questions: what kind of paint was used, and what was it painted on? How has the artist applied the paint? What does the scene depict, and what kinds of figures (an art-historical term that generally refers to humans) or animals are present? What makes these animals similar or different? How are they arranged? What colors are used in this painting? Are there any colors that pop out or contrast with the others? What might the artist have been trying to accomplish by adding certain details?

What other questions come to mind while examining this work? What kinds of topics come up in class when you discuss paintings like this one? Consider using your class experiences as a model for your own description! This process can be lengthy, so expect to spend some time observing the artwork and brainstorming.

Here is an example of some of the notes one might take while viewing Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty :

Composition

- The animals, four pigs total, form a gently sloping mound in the center of the painting.

- The upward mound of animals contrasts with the downward curve of the wooden fence.

- The gentle light, coming from the upper-left corner, emphasizes the animals in the center. The rest of the scene is more dimly lit.

- The composition is asymmetrical but balanced. The fence is balanced by the bush on the right side of the painting, and the sow with piglets is balanced by the pig whose head rests in the trough.

- Throughout the composition, the colors are generally muted and rather limited. Yellows, greens, and pinks dominate the foreground, with dull browns and blues in the background.

- Cool colors appear in the background, and warm colors appear in the foreground, which makes the foreground more prominent.

- Large areas of white with occasional touches of soft pink focus attention on the pigs.

- The paint is applied very loosely, meaning the brushstrokes don’t describe objects with exact details but instead suggest them with broad gestures.

- The ground has few details and appears almost abstract.

- The piglets emerge from a series of broad, almost indistinct, circular strokes.

- The painting contrasts angular lines and rectangles (some vertical, some diagonal) with the circular forms of the pig.

- The negative space created from the intersection of the fence and the bush forms a wide, inverted triangle that points downward. The point directs viewers’ attention back to the pigs.

Because these observations can be difficult to notice by simply looking at a painting, art history instructors sometimes encourage students to sketch the work that they’re describing. The image below shows how a sketch can reveal important details about the composition and shapes.

Writing: developing an interpretation

Once you have your descriptive information ready, you can begin to think critically about what the information in your notes might imply. What are the effects of the formal elements? How do these elements influence your interpretation of the object?

Your interpretation does not need to be earth-shatteringly innovative, but it should put forward an argument with which someone else could reasonably disagree. In other words, you should work on developing a strong analytical thesis about the meaning, significance, or effect of the visual material that you’ve described. For more help in crafting a strong argument, see our Thesis Statements handout .

For example, based on the notes above, you might draft the following thesis statement:

In Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty, the close proximity of the pigs to each other–evident in the way Morland has overlapped the pigs’ bodies and grouped them together into a gently sloping mound–and the soft atmosphere that surrounds them hints at the tranquility of their humble farm lives.

Or, you could make an argument about one specific formal element:

In Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty, the sharp contrast between rectilinear, often vertical, shapes and circular masses focuses viewers’ attention on the pigs, who seem undisturbed by their enclosure.

Support your claims

Your thesis statement should be defended by directly referencing the formal elements of the artwork. Try writing with enough specificity that someone who has not seen the work could imagine what it looks like. If you are struggling to find a certain term, try using this online art dictionary: Tate’s Glossary of Art Terms .

Your body paragraphs should explain how the elements work together to create an overall effect. Avoid listing the elements. Instead, explain how they support your analysis.

As an example, the following body paragraph illustrates this process using Morland’s painting:

Morland achieves tranquility not only by grouping animals closely but also by using light and shadow carefully. Light streams into the foreground through an overcast sky, in effect dappling the pigs and the greenery that encircles them while cloaking much of the surrounding scene. Diffuse and soft, the light creates gentle gradations of tone across pigs’ bodies rather than sharp contrasts of highlights and shadows. By modulating the light in such subtle ways, Morland evokes a quiet, even contemplative mood that matches the restful faces of the napping pigs.

This example paragraph follows the 5-step process outlined in our handout on paragraphs . The paragraph begins by stating the main idea, in this case that the artist creates a tranquil scene through the use of light and shadow. The following two sentences provide evidence for that idea. Because art historians value sophisticated descriptions, these sentences include evocative verbs (e.g., “streams,” “dappling,” “encircles”) and adjectives (e.g., “overcast,” “diffuse,” “sharp”) to create a mental picture of the artwork in readers’ minds. The last sentence ties these observations together to make a larger point about the relationship between formal elements and subject matter.

There are usually different arguments that you could make by looking at the same image. You might even find a way to combine these statements!

Remember, however you interpret the visual material (for example, that the shapes draw viewers’ attention to the pigs), the interpretation needs to be logically supported by an observation (the contrast between rectangular and circular shapes). Once you have an argument, consider the significance of these statements. Why does it matter if this painting hints at the tranquility of farm life? Why might the artist have tried to achieve this effect? Briefly discussing why these arguments matter in your thesis can help readers understand the overall significance of your claims. This step may even lead you to delve deeper into recurring themes or topics from class.

Tread lightly

Avoid generalizing about art as a whole, and be cautious about making claims that sound like universal truths. If you find yourself about to say something like “across cultures, blue symbolizes despair,” pause to consider the statement. Would all people, everywhere, from the beginning of human history to the present agree? How do you know? If you find yourself stating that “art has meaning,” consider how you could explain what you see as the specific meaning of the artwork.

Double-check your prompt. Do you need secondary sources to write your paper? Most visual analysis essays in art history will not require secondary sources to write the paper. Rely instead on your close observation of the image or object to inform your analysis and use your knowledge from class to support your argument. Are you being asked to use the same methods to analyze objects as you would for paintings? Be sure to follow the approaches discussed in class.

Some classes may use “description,” “formal analysis” and “visual analysis” as synonyms, but others will not. Typically, a visual analysis essay may ask you to consider how form relates to the social, economic, or political context in which these visual materials were made or exhibited, whereas a formal analysis essay may ask you to make an argument solely about form itself. If your prompt does ask you to consider contextual aspects, and you don’t feel like you can address them based on knowledge from the course, consider reading the section on research papers for further guidance.

2. Comparison essays

Comparison essays often require you to follow the same general process outlined in the preceding sections. The primary difference, of course, is that they ask you to deal with more than one visual source. These assignments usually focus on how the formal elements of two artworks compare and contrast with each other. Resist the urge to turn the essay into a list of similarities and differences.

Comparison essays differ in another important way. Because they typically ask you to connect the visual materials in some way or to explain the significance of the comparison itself, they may require that you comment on the context in which the art was created or displayed.

For example, you might have been asked to write a comparative analysis of the painting discussed in the previous section, George Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty (ca. 1800), and an unknown Vicús artist’s Bottle in the Form of a Pig (ca. 200 BCE–600 CE). Both works are illustrated below.

You can begin this kind of essay with the same process of observations and note-taking outlined above for formal analysis essays. Consider using the same questions and categories to get yourself started.

Here are some questions you might ask:

- What techniques were used to create these objects?

- How does the use of color in these two works compare? Is it similar or different?

- What can you say about the composition of the sculpture? How does the artist treat certain formal elements, for example geometry? How do these elements compare to and contrast with those found in the painting?

- How do these works represent their subjects? Are they naturalistic or abstract? How do these artists create these effects? Why do these similarities and differences matter?

As our handout on comparing and contrasting suggests, you can organize these thoughts into a Venn diagram or a chart to help keep the answers to these questions distinct.

For example, some notes on these two artworks have been organized into a chart:

As you determine points of comparison, think about the themes that you have discussed in class. You might consider whether the artworks display similar topics or themes. If both artworks include the same subject matter, for example, how does that similarity contribute to the significance of the comparison? How do these artworks relate to the periods or cultures in which they were produced, and what do those relationships suggest about the comparison? The answers to these questions can typically be informed by your knowledge from class lectures. How have your instructors framed the introduction of individual works in class? What aspects of society or culture have they emphasized to explain why specific formal elements were included or excluded? Once you answer your questions, you might notice that some observations are more important than others.

Writing: developing an interpretation that considers both sources

When drafting your thesis, go beyond simply stating your topic. A statement that says “these representations of pig-like animals have some similarities and differences” doesn’t tell your reader what you will argue in your essay.

To say more, based on the notes in the chart above, you might write the following thesis statement:

Although both artworks depict pig-like animals, they rely on different methods of representing the natural world.

Now you have a place to start. Next, you can say more about your analysis. Ask yourself: “so what?” Why does it matter that these two artworks depict pig-like animals? You might want to return to your class notes at this point. Why did your instructor have you analyze these two works in particular? How does the comparison relate to what you have already discussed in class? Remember, comparison essays will typically ask you to think beyond formal analysis.

While the comparison of a similar subject matter (pig-like animals) may influence your initial argument, you may find that other points of comparison (e.g., the context in which the objects were displayed) allow you to more fully address the matter of significance. Thinking about the comparison in this way, you can write a more complex thesis that answers the “so what?” question. If your class has discussed how artists use animals to comment on their social context, for example, you might explore the symbolic importance of these pig-like animals in nineteenth-century British culture and in first-millenium Vicús culture. What political, social, or religious meanings could these objects have generated? If you find yourself needing to do outside research, look over the final section on research papers below!

Supporting paragraphs

The rest of your comparison essay should address the points raised in your thesis in an organized manner. While you could try several approaches, the two most common organizational tactics are discussing the material “subject-by-subject” and “point-by-point.”

- Subject-by-subject: Organizing the body of the paper in this way involves writing everything that you want to say about Moreland’s painting first (in a series of paragraphs) before moving on to everything about the ceramic bottle (in a series of paragraphs). Using our example, after the introduction, you could include a paragraph that discusses the positioning of the animals in Moreland’s painting, another paragraph that describes the depiction of the pigs’ surroundings, and a third explaining the role of geometry in forming the animals. You would then follow this discussion with paragraphs focused on the same topics, in the same order, for the ancient South American vessel. You could then follow this discussion with a paragraph that synthesizes all of the information and explores the significance of the comparison.

- Point-by-point: This strategy, in contrast, involves discussing a single point of comparison or contrast for both objects at the same time. For example, in a single paragraph, you could examine the use of color in both of our examples. Your next paragraph could move on to the differences in the figures’ setting or background (or lack thereof).

As our use of “pig-like” in this section indicates, titles can be misleading. Many titles are assigned by curators and collectors, in some cases years after the object was produced. While the ceramic vessel is titled Bottle in the Form of a Pig , the date and location suggest it may depict a peccary, a pig-like species indigenous to Peru. As you gather information about your objects, think critically about things like titles and dates. Who assigned the title of the work? If it was someone other than the artist, why might they have given it that title? Don’t always take information like titles and dates at face value.

Be cautious about considering contextual elements not immediately apparent from viewing the objects themselves unless you are explicitly asked to do so (try referring back to the prompt or assignment description; it will often describe the expectation of outside research). You may be able to note that the artworks were created during different periods, in different places, with different functions. Even so, avoid making broad assumptions based on those observations. While commenting on these topics may only require some inference or notes from class, if your argument demands a large amount of outside research, you may be writing a different kind of paper. If so, check out the next section!

3. Research papers

Some assignments in art history ask you to do outside research (i.e., beyond both formal analysis and lecture materials). These writing assignments may ask you to contextualize the visual materials that you are discussing, or they may ask you to explore your material through certain theoretical approaches. More specifically, you may be asked to look at the object’s relationship to ideas about identity, politics, culture, and artistic production during the period in which the work was made or displayed. All of these factors require you to synthesize scholars’ arguments about the materials that you are analyzing. In many cases, you may find little to no research on your specific object. When facing this situation, consider how you can apply scholars’ insights about related materials and the period broadly to your object to form an argument. While we cannot cover all the possibilities here, we’ll highlight a few factors that your instructor may task you with investigating.

Iconography

Papers that ask you to consider iconography may require research on the symbolic role or significance of particular symbols (gestures, objects, etc.). For example, you may need to do some research to understand how pig-like animals are typically represented by the cultural group that made this bottle, the Vicús culture. For the same paper, you would likely research other symbols, notably the bird that forms part of the bottle’s handle, to understand how they relate to one another. This process may involve figuring out how these elements are presented in other artworks and what they mean more broadly.

Artistic style and stylistic period

You may also be asked to compare your object or painting to a particular stylistic category. To determine the typical traits of a style, you may need to hit the library. For example, which period style or stylistic trend does Moreland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty belong to? How well does the piece “fit” that particular style? Especially for works that depict the same or similar topics, how might their different styles affect your interpretation? Assignments that ask you to consider style as a factor may require that you do some research on larger historical or cultural trends that influenced the development of a particular style.

Provenance research asks you to find out about the “life” of the object itself. This research can include the circumstances surrounding the work’s production and its later ownership. For the two works discussed in this handout, you might research where these objects were originally displayed and how they ended up in the museum collections in which they now reside. What kind of argument could you develop with this information? For example, you might begin by considering that many bottles and jars resembling the Bottle in the Form of a Pig can be found in various collections of Pre-Columbian art around the world. Where do these objects originate? Do they come from the same community or region?

Patronage study

Prompts that ask you to discuss patronage might ask you to think about how, when, where, and why the patron (the person who commissions or buys the artwork or who supports the artist) acquired the object from the artist. The assignment may ask you to comment on the artist-patron relationship, how the work fit into a broader series of commissions, and why patrons chose particular artists or even particular subjects.

Additional resources

To look up recent articles, ask your librarian about the Art Index, RILA, BHA, and Avery Index. Check out www.lib.unc.edu/art/index.html for further information!

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Adams, Laurie Schneider. 2003. Looking at Art . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Barnet, Sylvan. 2015. A Short Guide to Writing about Art , 11th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Tate Galleries. n.d. “Art Terms.” Accessed November 1, 2020. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Ask Yale Library

My Library Accounts

Find, Request, and Use

Help and Research Support

Visit and Study

Explore Collections

Art History Research at Yale: Dissertations & Theses

- How to Research Art

- Primary Sources

- Biographical Information

- Dissertations & Theses

- Image & Video Resources

- How to Cite Your Sources

- Copyright and Fair Use

- Collecting and Provenance Research This link opens in a new window

- How to Find Images

WHAT EXPERT RESEARCHERS KNOW

A thesis is typically the culminating project for a master's degree, while a dissertation completes a doctoral degree and represents a scholar's main area of expertise. However, some undergraduate students write theses that are published online, so it is important to note which degree requirements the thesis meets. While these are not published works like peer-reviewed journal articles, they are typically subjected to a rigorous committee review process before they are considered complete. Additionally, they often provide a large number of citations that can point you to relevant sources.

Find Dissertations & Theses at Yale

Dissertations & Theses @ Yale University A searchable databases with dissertations and theses in all disciplines written by students at Yale from 1861 to the present.

Yale University Master of Fine Arts Theses in Graphic Design Finding aid for Arts Library Special Collections holdings of over 600 individual theses from 1951 to the present. The theses are most often in book format, though some have more experimental formats. Individual records for the theses are also available in the library catalog.

Yale University Master of Fine Arts Theses in Photography Finding aid for Arts Library Special Collections holdings of over 300 individual Master of Fine Arts theses from 1971 to the present. The theses are most often in the format of a portfolio of photographic prints, though some theses are also in book form. Individual records for the MFA theses are also available in the library catalog.

Find Dissertations & Theses Online

- << Previous: Biographical Information

- Next: Image & Video Resources >>

- Last Updated: Aug 17, 2023 11:33 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/arthistoryresearch

Site Navigation

P.O. BOX 208240 New Haven, CT 06250-8240 (203) 432-1775

Yale's Libraries

Bass Library

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Classics Library

Cushing/Whitney Medical Library

Divinity Library

East Asia Library

Gilmore Music Library

Haas Family Arts Library

Lewis Walpole Library

Lillian Goldman Law Library

Marx Science and Social Science Library

Sterling Memorial Library

Yale Center for British Art

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

@YALELIBRARY

Yale Library Instagram

Accessibility Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Giving Privacy and Data Use Contact Our Web Team

© 2022 Yale University Library • All Rights Reserved

Department of Art and Art History

The MA thesis represents the final step in the fulfillment of your degree at Hunter. It should embody originality of thinking underscored by solid research based on primary and secondary sources. The thesis should demonstrate your ability to gather, evaluate, and present material in a critical and professional manner. It is intended to prepare you for further study on the doctoral level or as an end in itself to equip you with the skills necessary for a professional career in Art History.

Completed theses are approximately 50-75 pages in length and should exhibit a full scholarly textual apparatus: footnotes, bibliography, illustrations, and other relevant documentation.

For a comprehensive guide to the MA Thesis, please see MA Thesis Guidelines .

The MA thesis is designed to be written over the course of two consecutive semesters and is formally divided into two classes: Thesis Research (ARTH 79900) and Thesis Writing (ARTH 80000).

In Thesis Research the student will, in collaboration with their thesis advisor, define a topic, structure an argument, and begin researching and writing their thesis. In order to receive course credit, the student must submit an outline (including abstract and chapter summaries) and a draft of one chapter by the end of the semester.

Over the course of Thesis Writing , each student works individually with their primary advisor towards the completion of a polished, submission-ready thesis, which involves the deployment of primary and secondary research, the analysis of objects of visual and material culture, the crafting of convincing argumentation, and the editing of language at the sentence, paragraph, and thesis-level. The student will only receive credit for ARTH 80000 upon successful completion and submission of the thesis.

Each MA student is required to choose an advisor from the full-time Art History faculty to supervise their thesis project. The faculty member should be someone who is a specialist in your chosen area and, ideally, someone who you have already taken a class with during the course of your studies at Hunter. Students are advised to approach their intended advisor no later than the semester before enrolling in Thesis Research (ARTH 79900). While the faculty advisor can be of some assistance in refining an appropriate topic, you should already have several ideas in mind before opening the discussion.

The faculty advisor formally acts as the first reader of your thesis, providing direction and initial criticism of your research. Students are expected to speak regularly with their advisor over the course of two semesters. Before enrolling in Thesis Writing (ARTH 80000) students are advised to select a second reader for their thesis. The second reader is not a mentor but an external assessor of your final work. They should be chosen in consultation with your first reader and approached in a timely manner. Once the thesis has been finalized by the primary advisor, it will be turned over to the second reader for review. The second reader can make helpful suggestions and corrections to produce a better thesis.

Your thesis cannot be submitted without the signature of your first and second reader.

- October 30: Submit completed thesis to the first reader (thesis advisor).

- November 20: Submit the thesis, approved by the first reader, to the second reader

- December 14: Submit completed, edited thesis to the graduate advisor

- December 21: Upload the thesis to CUNY Academic Works

Funding for travel and thesis research:

The dean of arts and science offers travel grants to support thesis research up to $500 each.

To apply, please visit the following website: http://www.hunter.cuny.edu/artsci/graduate-education/funding-opportunities-for-graduate-students .

For further information please email Rob Cowan: [email protected]

Examples of recent MA Theses:

- Croft, Kyle, “Mobilizing Museums Against AIDS: Visual AIDS and Day Without Art, 1988–1989” (2020). CUNY Academic Works.

https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/578

- Shaikewitz, Joseph S., “Mexican Modernism’s Other: The Contemporáneos, Gender, and National Identity, 1920–1940” (2020). CUNY Academic Works.

https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/601

- Shevelkina, Maria M., “The Chôra of Dionisy’s Wall-Painting (1500-1502) at the Nativity of the Mother of God sobor, Ferapontovo Monastery” (2020). CUNY Academic Works.

https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/548

- Thackara, Tess, “Beyond Movements: Senga Nengudi’s Art Within and Without Feminism, Postminimalism, and the Black Arts Movement” (2020). CUNY Academic Works.

https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/605

Important Links and Documents

- Guidelines for the Preparation of a Master’s Thesis In Art History

- MA Thesis Agreement Form

- Maintenance of Matriculation Form

- School of Arts and Sciences Guidelines

- Step by Step Guide for Students

- Step by Step Guide for Readers

- Art History 799 Thesis Research

- Art History 800 Thesis Writing

I. General Information

II. Thesis Track: Program of Study

III: Thesis Track: Specific Requirements

IV. Non-Thesis Track: Program of Study

V. Non-Thesis Track: Specific Requirements

VI. Additional Important Information

Graduate Student Handbook Table of Contents

School Admin Structure

Info on UGA Policies

Graduate Enrollment Policies

Graduate Forms

Master of Art Degree in Art History (MA) Procedures & Requirements

Successful completion of the Master’s degree in Art History requires that the student fulfill several requirements in sequence, as determined by the student’s admission to one of two tracks within the MA program: the MA with thesis or the non-thesis MA. Below the student will find general information related to the program, as well as detailed information about specific requirements and the order in which they must be completed.

A. Thesis Track/Non-Thesis Track

The MA program in Art History has two,36-hour tracks: the thesis track and the non-thesis track. The thesis track is best suited for students who are interested in and capable of doctoral studies in art history. The non-thesis track is designed to accommodate those students who intend to pursue careers and professions that require a broad base of art historical knowledge but not the specialized, research-oriented skills required by the PhD in Art History.

Prospective students declare their intention to pursue a thesis or non-thesis track at the time of application. On acceptance into the MA program, the student’s program of study will be determined by this designation, which may change should the student or faculty find the student better suited to an alternative track. In the event of this, please contact the Graduate Office.

During the second semester in residence, each student must outline a program of study for meeting degree requirements in the thesis or non-thesis track. This program should be developed in consultation with the Major Professor and Advisory Committee (thesis-track) or the Area Chair (non-thesis track) and recorded on a Program of Study for Masters of Arts and Sciences form. You must submit an official Program of Study ( Form G138, found here ) the semester you are set to graduate. The Graduate Office will review your Program of Study before forwarding it to the Graduate School for approval.

If, after this point, an alteration to the Program of Study is necessary due to a change in course work, the Graduate Coordinator's Office must be notified so the paperwork any changes can be submitted to the Dean for further approval.

Note: The language requirement (see below) must be met prior to submitting this form.

B. Curriculum

MA students in both tracks are expected to enroll in at least 5 8000-level ARHI courses (i.e. grad seminars) across two years, three of which are to be completed in the first year. In rare cases, an exception might be approved by the student’s advisor, should another course be deemed indispensable to the student’s program of study.

C. Distribution

Because the MA degree is designed to provide a broad base of knowledge in the field of Art History, seminars are to be distributed as follows: 2 Pre-modern, 2 modern, and 1 or more in any area of the student’s choosing. Pre-modern includes Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance, Baroque and Non-Western; Modern includes 18 th -21 st Century.

In addition, MA students are required to take at least one course, whether at the 8000- or 6000-level, in each of the following areas: Area 1: Ancient, Non-Western; Area 2. Byzantine/Medieval, Renaissance/Baroque; Area 3; 18th and 19th Century; Area 4: 20th and 21st Century.

D. Grade Point Average

No grade below C will be accepted on the program of study. To be eligible for graduation, a student must maintain a 3.0 (B) average on the graduate transcript and a 3.0 (B) average on the program of study.

Funding is reviewed and awarded annually based on student performance. MA students are not eligible for departmental funding beyond the second year of the program.

II. Thesis Track: Program of Study

A. major professor.

During the first semester of study, the Chair of the Art History area will serve as a temporary advisor for all incoming students pursuing the thesis track. In the course of the first semester, and not later than the beginning of the second, each student is expected to approach a member of the faculty with whom he or she would like to work towards the completion of the Thesis and Master’s Degree. The Major Professor must be a member of the Art History faculty at UGA as well as a member of the University's graduate faculty.

The willingness of the faculty member to serve as the student’s major professor is recorded on the Change of Major Professor form, which is available from the Graduate Coordinator or online here . From this point forward, it is the responsibility of the student to arrange periodic conferences with the Major Professor to report his or her progress.

With approval from the art history area, a student may change his or her Major Professor a second time, providing he/she secures the appropriate signatures on the Change of Graduate Advisor/Major Professor Form (see above).

B. Advisory Committee

At the end of the second semester of study, following the submission of the Thesis Abstract (see below), each student will be assigned an Advisory Committee comprised of three faculty members , all of whom must be members of the Graduate Faculty. The appropriate form, found here , will then be forwarded from the Graduate Office to the Graduate School for approval. This process is initiated by the student.

In most cases, the Advisory Committee will be composed entirely of art history faculty. Faculty from other liberal arts disciplines may serve on committees as appropriate, but two-thirds of the committee must be made up of members of the art history faculty.

C. University-wide Required Courses

As of fall 2022, all graduate students are required to take the GradFIRST seminar (GRSC 7001). This one-credit, seminar style class is designed to introduce graduate students to supplement discipline-specific education with more generalized material meant to help incoming students successfully navigate graduate education at UGA. This course is to be taken in addition to the three-credit Graduate Seminar (GRSC 7770), which is required for all students on assistantship with instructional duties.

D. General Requirements

30 hours of classroom work (SUBTOTAL)

6 hours of research/thesis (a student may register for additional hours depending upon the time devoted to the research and thesis): ARHI 7000 and ARHI 7300.

1 hour GradFIRST seminar.

37 hours TOTAL

Note: In total, from entrance to defense of the MA thesis, the MA program is expected take no more than 2 years, with a graduation date in May of the second year. Although the graduate school allows students to submit their MA thesis within six years of their initial enrollment, continued advising from the Major Professor or the Advisory Committee should not be presumed for the duration of this period

Note: A student must be registered during any period in which he/she receives guidance from his / her advisory committee, uses university facilities or completes his/her work.

E. Foreign Language Requirement

Before beginning the second year of course work, each student must demonstrate a reading knowledge of an approved foreign language (in most cases Italian, French, Spanish or German). The language requirement can be demonstrated by earning a grade of “B” or better in a University of Georgia foreign language reading course or by passing a reading knowledge examination prepared by the Departments of Romance Languages or Germanic and Slavic Languages. A third alternative is to complete four semester of foreign language study (the equivalent of UGA’s 1001, 1002, 2001, and 2002); in these four courses a student must achieve a minimum of 3.0 GPA. This requirement may also be satisfied by successful completion of the equivalent course work before graduate school, as demonstrated by the student’s transcripts.

Note: Some students who enter the MA program with a weak background in art history may be required to make up their deficiency by taking prerequisite undergraduate course work beyond the standard requirements.

A. Abstract/Comprehensive Examination

The comprehensive examination is required at the end of the second semester in the MA program.This examination takes the form of a Thesis Abstract that describes to Abstract, which must include an outline, annotated bibliography, and illustrations, must be submitted to the Major Professor at least two weeks to the submission deadline.

Before the Thesis Abstract is submitted to the area, it must first be read and approved by the Major Professor. This abstract must include:

• A 3-4 page written narrative that describes the topic or problem and its significance within the field. This précis should also briefly layout the student method and research plans.

• A 1-2 page outline that indicates in general terms the order in which the issues are to be considered.

• A 2-4 page annotated bibliography of the key sources.

Up to 5 key images.

The abstract must be submitted to the Art History Area by the first Friday in April, as a compressed PDF. The faculty will determine, in conjunction with the student’s academic performance, whether the proposal has been approved, rejected, or needs to be revised shortly after the submission deadline. In the event of rejection, students might be invited to pursue the non-thesis track, though such an invitation is at the discretion of the faculty. If invited to revise, any required revisions must be completed before the last scheduled day of final exams. If the revised abstract is not approved, the student will be dismissed from the program and will not be allowed to take classes in the following semester.

Timetable for Part-Time Students:

In general, the MA program in art history is structured for full-time enrollment; i.e. three classes per semester of graduate work. On the very rare occasions that part- time students are accepted into the program (typically because they have full-time jobs at the University of Georgia), the students are required to take no less than two classes per semester of graduate work. In practice, this means that the Thesis Abstract must be submitted by the end of the third semester in the program. Revisions must be submitted by the middle of the fourth semester.

B. Thesis: Preparation/Submission/Defense

1. general information.

The MA thesis is the key document demonstrating a student’s competence and eligibility to receive a Master’s degree from the School of Art. Written under the direction of the Major Professor, the thesis is intended to demonstrate the ability of the student to make independent use of the most sophisticated sources of information available, including materials written foreign languages, especially in the language in which he/she has acquired a reading knowledge. In addition, it must also demonstrate the ability of the student to assemble relevant information in a clear and compelling manner and that shows, in addition, an ability to establish a strong art historical argument, written in clear expository prose. The length of the thesis should not exceed 25 pages, excluding notes and images.

Note: Following the first year of course work and the approval of the Thesis Abstract, full-time students enrolled in the thesis track are expected to research, write, and defend their Master’s Theses in one year. Part-time students, who are enrolled for five semesters in order to complete their coursework, will have an additional two semesters to complete the thesis.

Note: Students must be registered for at least 3 hours of thesis under the course number ARHI 7300 during the semester that the thesis is approved and they graduate

2. Specific Requirements / Timetable Thesis Preparation / Internal Evaluation

Students are responsible for initiating the writing process and for meeting all deadlines established by the Major Professor, the Art History area, and the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Arranged in chronological order, these are the deadlines to which the student must adhere:

The first complete draft of the Thesis must be submitted to the Major Professor no later than the beginning of the final (this is to say 4th) semester in residence. Shortly thereafter (and no later than the end of the first month of the semester in which the student intends to graduate) the student must meet with the entire Advisory Committee. At this meeting, the student will present progress made to date and will develop, in conjunction with the Advisory Committee, a timetable for the completion of the research and/or writing. At this initial meeting, or at a subsequent meeting, the committee will specify when they next expect to be apprised of the student’s progress and what form that demonstration of progress should take. If the committee decides that portions of the thesis should be presented to them for subsequent review, such a demonstration will not be submitted to the committee without prior approval by the Major Professor.

Before the completed thesis is submitted to the committee, the Major Professor must read and provisionally approve the final draft. If the Major Professor calls for changes, these must be done and resubmitted to the Major Professor for his/her provisional approval. Please note that the final draft must be prepared in accordance with a published manual of style (see A Student Guide to Preparation and Processing Theses), available in the Graduate School and must include footnotes, illustrations, and bibliography.

No less than four weeks before the scheduled Thesis Defense (see below) and no less than six weeks before the anticipated date of graduation, the student must submit three copies of the approved draft to the Advisory Committee. Comments may be presented to the student before the Thesis Defense or else at the defense itself. If the Advisory Committee determines that changes must be made before the Thesis Defense, then a revised schedule will be determined at that juncture. With regard to changes called for at the defense, the committee may require a review of the corrected thesis or they may relinquish that task, leaving the approval of the corrections to the Major Professor.

Per University guidelines, the use of generative AI in theses and dissertations is considered unauthorized assistance per the Academic Code of Honesty and is prohibited unless specifically authorized by members of the advisory committee for use within the approved scope. If approved by the advisory committee, the extent of generative AI usage should be disclosed in a statement within the thesis or dissertation.

An Application for Graduation available online can be found in ATHENA and must be filed with the Graduate School no later than the Friday of the first full week of classes of the semester you plan to complete your thesis and graduate.

3. Defense and Final Examination

The Master's Thesis defense is chaired by the student's major professor and attended by all members of the advisory committee. It will consist of two parts: 1) a public presentation of the student's research, and 2) a private defense attended by the student and advisory committee. Public research presentations will be scheduled the first Monday in April in conjunction with a departmental Research Day and should take the form of a 20-minute, illustrated lecture. Private defenses are to occur within a two-week window thereafter and are to be scheduled by the student in consultation with the student's Advisory Committee. Once a date for the private portion of the defense has been agreed upon, the student should file a Thesis Defense Request form with the school of Art Graduate Office.

The student and committee chair must appear in person for both components of the defense, but other committee members can participate via teleconference or video conference, provided that the comments of all participants can clearly and consistently be heard. If the major professor is not able to attend the defense in person, a substitute chair who is a current member of the committee can be designated. The defense can be held completely remotely if circumstances warrant and approval is granted by the Associate Director of Research and Graduate Studies and the School of Art Director. The advisory committee must approve the student's thesis and defense with no more than one dissenting vote and must certify its approval in writing, using the Approval Form for Master's Thesis, Defense, and Final Examination . An Abstention is not allowable for the final defense. An abstention is not allowable for the final defense. The results of the defense must be reported to the Graduate School at least two weeks prior to graduation for the current semester.

Student should not presume a summer defense or graduation, as faculty are often unable to serve at this time.

The honorific “with Distinction” is granted by the Area to students who, through independent research, produce exemplary theses that make a significant contribution to the field.

Successful defense of the MA thesis is only one of the requirements essential for the awarding of an MA in art history from UGA. Before the defense of the thesis, the student must have completed all course, language, and residency requirements as stated in the Graduate Bulletin.

4. Submission to the Graduate School / Final Approval

An Application for Graduation must be filed online with the Graduate School no later than Friday of the first full week of classes of your final semester (see Graduate School website for deadlines).

To ensure a smooth graduation, several things must take place in a timely fashion:

a. No later than four weeks prior to graduation (see Graduate School website for deadlines here), a complete formatted copy of the thesis must be electronically submitted to the Graduate School for a format check.

b. Approximately two weeks prior to the graduation ceremony (see Graduate School website for each semester’s deadlines ), the Graduate School must receive the Approval Form for Master’s Thesis, Defense, and Final Examination and an electronic submission of the corrected dissertation. This official electronic copy of the thesis will then be submitted by the Graduate School to the main library for archiving.

One electronic copy of the thesis must be submitted to the Graduate Coordinator's Office. A final copy of the thesis is also due to the Major Professor; students should consult with their Major Professor about which format – i.e. bound, electronic, unbound hard copy – is preferred.

All remaining course requirements (including incompletes) for the degree must be completed and reported to the Graduate School no later than one week prior to graduation. A student must enroll for a minimum of three hours of credit the semester in which graduation requirements are completed.

Note: Students should regularly check the Graduate School Website for deadline and procedural information related to the Masters Thesis.

IV. Non-Thesis Track: Program of Study

General requirements: non-thesis track.

30 hours in graduate art history courses, 15 hours of which must be taken at the 8000 level. (i.e., graduate seminars).

3 hours of art history or an approved elective outside the art history area that is central to the student's program of study.

3 hours in required ARHI 8050 Professional Portfolio and Practices

36 hours of classroom work

University-wide Required Courses

V. non-thesis track: specific requirements.

In lieu of a thesis, students pursuing the non-thesis track must take and pass ARHI 8050 Professional Portfolio and Practices. This course will prepare the student for various employment opportunities by requiring the creation, presentation, and revision of a professional portfolio. This course will serve as the culmination of the student’s graduate studies, and is meant to facilitate the student’s transition from an academic environment to the professional world.

This course will be graded on a Pass/Fail basis and may be repeated should the student fail on the first attempt. Should the student fail the course twice, he or she will not be allowed to obtain the MA in Art History. The class will be taught as needed in the spring semester so as to ensure that students pursuing the non-thesis track are able to graduate within a two-year timeframe.

VI. Symposia and Conferences

Graduate students in the History of Art are encouraged to present their research at conferences and symposia and to seek funding for related expenses. Students should consult with their Major Professor and Advisory Committee prior to submitting their abstracts, and on acceptance, they should contact with the Art History Area Chair and the Associate Director of Research and Graduate Studies to schedule a run-through of their presentations.

VII. Additional Important Information

Students in the Art History MA program at the University of Georgia have requirements and responsibilities that originate from the University, from the Graduate School, from the Lamar Dodd School of Art, and from the Art History Area. Please note that changes are occasionally made to the degree requirements and scheduling, which may significantly impact your program of study. Any such changes will automatically become part of your required program of study.

It is the student's responsibility to study the Graduate Bulletin, the School of Art brochure, and the School’s website ( http://www.art.uga.edu ) and to meet all requirements for his/her degree, including the Art School requirements listed below, and to observe all appropriate deadlines as his/her graduate program progresses.

Deadline dates and other pertinent information are posted regularly on the Graduate School website ( http://www.grad.uga.edu/ ). Please review frequently. Also, each graduate student is assigned a mailbox where all mail and notices will be placed for your convenience. Check your mailbox often for important announcements. Each student is required to have a UGA MYID email address. The Graduate Coordinator and the area chair for Art History should be provided with this address immediately. Students are expected to check it daily for pertinent information from the Graduate Program, the School, and the Area. Please also make note of the Graduate School's enrollment policies . This link includes information on Minimum Enrollment, Continuous Enrollment, Residence Credit, and Leave of Absence, Time Limit, and Extension of Time requirements.

All graduate students are required to be active members and participants in the Association of Graduate Art Students (AGAS). All graduate students are required to attend all AGAS lectures and are strongly encouraged to attend all other relevant lectures offered by the Lamar Dodd School of Art. The officers of AGAS should be prepared to represent the graduate students when called upon to do so by the School.

Keep the Graduate Coordinator’s Office updated on changes of address, phone number, and email each semester.

TIMETABLE FOR COMPLETING MA REQUIREMENTS.pdf

This handbook was last reviewed in August 2022 and last revised on February 13, 2024.

Art History Writing Guide

I. Introduction II. Writing Assignments III. Discipline-Specific Strategies IV. Keep in Mind V. Appendix

Introduction

At the heart of every art history paper is a close visual analysis of at least one work of art. In art history you are building an argument about something visual. Depending on the assignment, this analysis may be the basis for an assignment or incorporated into a paper as support to contextualize an argument. To guide students in how to write an art history paper, the Art History Department suggests that you begin with a visual observation that leads to the development of an interpretive thesis/argument. The writing uses visual observations as evidence to support an argument about the art that is being analyzed.

Writing Assignments

You will be expected to write several different kinds of art history papers. They include:

- Close Visual Analysis Essays

- Close Visual Analysis in dialogue with scholarly essays

- Research Papers

Close Visual Analysis pieces are the most commonly written papers in an introductory art history course. You will have to look at a work of art and analyze it in its entirety. The analysis and discussion should provide a clearly articulated interpretation of the object. Your argument for this paper should be backed up with careful description and analysis of the visual evidence that led you to your conclusion.

Close Visual Analysis in dialogue with scholarly essays combines formal analysis with close textual analysis.

Research papers range from theoretic studies to critical histories. Based on library research, students are asked to synthesize analyses of the scholarship in relation to the work upon which it is based.

Discipline-Specific Strategies

As with all writing assignment, a close visual analysis is a process. The work you do before you actually start writing can be just as important as what you consider when writing up your analysis.

Conducting the analysis :

- Ask questions as you are studying the artwork. Consider, for example, how does each element of the artwork contribute to the work's overall meaning. How do you know? How do elements relate to each other? What effect is produced by their juxtaposition

- Use the criteria provided by your professor to complete your analysis. This criteria may include forms, space, composition, line, color, light, texture, physical characteristics, and expressive content.

Writing the analysis:

- Develop a strong interpretive thesis about what you think is the overall effect or meaning of the image.

- Ground your argument in direct and specific references to the work of art itself.

- Describe the image in specific terms and with the criteria that you used for the analysis. For example, a stray diagonal from the upper left corner leads the eye to...

- Create an introduction that sets the stage for your paper by briefly describing the image you are analyzing and by stating your thesis.

- Explain how the elements work together to create an overall effect. Try not to just list the elements, but rather explain how they lead to or support your analysis.

- Contextualize the image within a historical and cultural framework only when required for an assignment. Some assignments actually prefer that you do not do this. Remember not to rely on secondary sources for formal analysis. The goal is to see what in the image led to your analysis; therefore, you will not need secondary sources in this analysis. Be certain to show how each detail supports your argument.

- Include only the elements needed to explain and support your analysis. You do not need to include everything you saw since this excess information may detract from your main argument.

Keep in Mind

- An art history paper has an argument that needs to be supported with elements from the image being analyzed.

- Avoid making grand claims. For example, saying "The artist wanted..." is different from "The warm palette evokes..." The first phrasing necessitates proof of the artist's intent, as opposed to the effect of the image.

- Make sure that your paper isn't just description. You should choose details that illustrate your central ideas and further the purpose of your paper.

If you find you are still having trouble writing your art history paper, please speak to your professor, and feel free to make an appointment at the Writing Center. For further reading, see Sylvan Barnet's A Short Guide to Writing about Art , 5th edition.

Additional Site Navigation

Social media links, additional navigation links.

- Alumni Resources & Events

- Athletics & Wellness

- Campus Calendar

- Parent & Family Resources

Helpful Information

Dining hall hours, next trains to philadelphia, next trico shuttles.

Swarthmore Traditions

How to Plan Your Classes

The Swarthmore Bucket List

Search the website

Department of the History of Art

You are here, dissertations, completed dissertations.

1942-present

DISSERTATIONS IN PROGRESS

As of July 2023

Bartunkova, Barbora , “Sites of Resistance: Antifascism and the Czechoslovak Avant-garde” (C. Armstrong)

Betik, Blair Katherine , “Alternate Experiences: Evaluating Lived Religious Life in the Roman Provinces in the 1st Through 4th Centuries CE” (M. Gaifman)

Boyd, Nicole , “Science, Craft, Art, Theater: Four ‘Perspectives’ on the Painted Architecture of Angelo Michele Colonna and Agostino Mitelli” (N. Suthor).

Brown, Justin , “Afro-Surinamese Calabash Art in the Era of Slavery and Emancipation” (C. Fromont)

Burke, Harry , “The Islands Between: Art, Animism, and Anticolonial Worldmaking in Archipelagic Southeast Asia” (P. Lee)

Chakravorty, Swagato , “Displaced Cinema: Moving Images and the Politics of Location in Contemporary Art” (C. Buckley, F. Casetti)

Chau, Tung , “Strange New Worlds: Interfaces in the Work of Cao Fei” (P. Lee)

Cox, Emily , “Perverse Modernism, 1884-1990” (C. Armstrong, T. Barringer)

Coyle, Alexander , “Frame and Format between Byzantium and Central Italy, 1200-1300” (R. Nelson)

Datta, Yagnaseni , “Materialising Illusions: Visual Translation in the Mughal Jug Basisht, c. 1602.” (K. Rizvi)

de Luca, Theo , “Nicolas Poussin’s Chronotopes” (N. Suthor)

Dechant, D. Lyle . ” ‘daz wir ein ander vinden fro’: Readers and Performers of the Codex Manesse” (J. Jung)

Del Bonis-O’Donnell, Asia, “Trees and the Visualization of kosmos in Archaic and Classical Athenian Art” (M. Gaifman)

Demby, Nicole, “The Diplomatic Image: Framing Art and Internationalism, 1945-1960” (K. Mercer)

Donnelly, Michelle , “Spatialized Impressions: American Printmaking Outside the Workshop, 1935–1975” (J. Raab)

Epifano, Angie , “Building the Samorian State: Material Culture, Architecture, and Cities across West Africa” (C. Fromont)

Fialho, Alex , “Apertures onto AIDS: African American Photography and the Art History of the Storage Unit” (P. Lee, T Nyong’o)

Foo, Adela , “Crafting the Aq Qoyuniu Court (1475-1490) (E. Cooke, Jr.)

Franciosi, Caterina , “Latent Light: Energy and Nineteenth-Century British Art” (T. Barringer)

Frier, Sara , “Unbearable Witness: The Disfigured Body in the Northern European Brief (1500-1620)” (N. Suthor)

Gambert-Jouan, Anabelle , “Sculpture in Place: Medieval Wood Depositions and Their Environments” (J. Jung)

Gass, Izabel, “Painted Thanatologies: Théodore Géricault Against the Aesthetics of Life” (C. Armstrong)

Gaudet, Manon , “Property and the Contested Ground of North American Visual Culture, 1900-1945” (E. Cooke, Jr.)

Haffner, Michaela , “Nature Cure: ”White Wellness” and the Visual Culture of Natural Health, 1870-1930” (J. Raab)

Hepburn, Victoria , “William Bell Scott’s Progress” (T. Barringer)

Herrmann, Mitchell, “The Art of the Living: Biological Life and Aesthetic Experience in the 21st Century” (P. Lee)

Higgins, Lily , “Reading into Things: Articulate Objects in Colonial North America, 1650-1783” (E. Cooke, Jr.)

Hodson, Josie , “Something in Common: Black Art under Austerity in New York City, 1975-1990” (Yale University, P. Lee)

Hong, Kevin , “Plasticity, Fungibility, Toxicity: Photography’s Ecological Entanglements in the Mid-Twentieth-Century United States” (C. Armstrong, J Raab)

Kang, Mia , “Art, Race, Representation: The Rise of Multiculturalism in the Visual Arts” (K. Mercer)

Keto, Elizabeth , “Remaking the World: United States Art in the Reconstruction Era, 1861-1900.” (J. Raab)

Kim, Adela , “Beyond Institutional Critique: Tearing Up in the Work of Andrea Fraser” (P. Lee)

Koposova, Ekaterina , “Triumph and Terror in the Arts of the Franco-Dutch War” (M. Bass)

Lee, Key Jo , “Melancholic Materiality: History and the Unhealable Wound in African American Photographic Portraits, 1850-1877” (K. Mercer)

Levy Haskell, Gavriella , “The Imaginative Painter”: Visual Narrative and the Interactive Painting in Britain, 1851-1914” (T. Barringer, E. Cooke Jr)

Marquardt, Savannah, “Becoming a Body: Lucanian Painted Vases and Grave Assemblages in Southern Italy” (M. Gaifman)

Miraval, Nathalie , “The Art of Magic: Afro-Catholic Visual Culture in the Early Modern Spanish Empire” (C. Fromont)

Mizbani, Sharon , Water and Memory: Fountains, Heritage, and Infrastructure in Istanbul and Tehran (1839-1950) (K. Rizvi)

Molarsky-Beck, Marina, “Seeing the Unseen: Queer Artistic Subjectivity in Interwar Photography” (C. Armstrong)

Nagy, Renata , “Bookish Art: Natural Historical Learning Across Media in Seventeenth-century Northern Europe” (Bass, M)

Olson, Christine , “Owen Jones and the Epistemologies of Nineteenth-Century Design” (T. Barringer)

Petrilli-Jones, Sara , “Drafting the Canon: Legal Histories of Art in Florence and Rome, 1600-1800” (N. Suthor)

Phillips, Kate , “American Ephemera” (J. Raab)

Potuckova, Kristina , “The Arts of Women’s Monastic Liturgy, Holy Roman Empire, 1000-1200” (J. Jung)

Quack, Gregor , “The Social Fabric: Franz Erhard Walther’s Art in Postwar Germany” (P. Lee)

Rahimi-Golkhandan, Shabnam , “The Photograph’s Shabih-Kashi (Verisimilitude) – The Liminal Visualities of Late Qajar Art (1853-1911)” (K. Rizvi)

Rapoport, Sarah , “James Jacques Joseph Tissot in the Interstices of Modernity” (T. Barringer, C. Armstrong)

Riordan, Lindsay , “Beuys, Terror, Value: 1967-1979” (S. Zeidler)

Robbins, Isabella , “Relationality and Being: Indigeneity, Space and Transit in Global Contemporary Art” (P. Lee, N. Blackhawk)

Sen, Pooja , “The World Builders ” (J. Peters)

Sellati, Lillian , “When is Herakles Not Himself? Mediating Cultural Plurality in Greater Central Asia, 330 BCE – 365 CE” (M. Gaifman)

Tang, Jenny , “Genealogies of Confinement: Carceral Logics of Visuality in Atlantic Modernism 1930 – 1945” (K. Mercer)

Thomas, Alexandra , “Afrekete’s Touch: Black Queer Feminist Errantry and Global African Art” (P. Lee)

Valladares, Carlos , “Jacques Demy” (P. Lee)

Verrot, Trevor , “Sculpted Lamentation Groups in the Late Medieval Veneto” (J. Jung)

Von-Ow, Pierre , Visual Tactics: Histories of Perspective in Britain and its Empire, 1670-1768.” (T. Barringer)

Wang, Xueli , “Performing Disappearance: Maggie Cheung and the Off-Screen” (Q. Ngan)

Webley, John , “Ink, Paint, and Blood: India and the Great Game in Russian Culture” (T. Barringer, M. Brunson)

Werwie, Katherine , “Visions Across the Gates: Materiality, Symbolism, and Communication in the Historiated Wooden Doors of Medieval European Churches” (J. Jung)

Wisowaty, Stephanie , “Painted Processional Crosses in Central Italy, 1250-1400: Movement, Mediation and Multisensory Effects” (J. Jung)

Young, Colin , “Desert Places: The Visual Culture of the Prairies and the Pampas across the Nineteenth Century” (J. Raab)

Zhou, Joyce Yusi, “Objects by Her Hand: Art and Material Culture of Women in Early Modern Batavia (1619-1799) (M. Bass, E. Cooke, Jr.)

- The Student Experience

- Financial Aid

- Degree Finder

- Undergraduate Arts & Sciences

- Departments and Programs

- Research, Scholarship & Creativity

- Centers & Institutes

- Geisel School of Medicine

- Guarini School of Graduate & Advanced Studies

- Thayer School of Engineering

- Tuck School of Business

Campus Life

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Athletics & Recreation

- Student Groups & Activities

- Residential Life

Art History

Department of art history.

- [email protected] Contact & Department Info Mail

- Undergraduate

- Major, Minor and Modifications

- Distribution of Subject Areas

- Foreign Study

- Careers & Opportunities

- College-level teaching

- Museum Work

- Publishing and Freelance Writing

- Art Librarian and Visual Resource Librarian

- Secondary Education

- Art and Architectural Preservation and Conservation

- Art Galleries / Auction Houses

- Corporate Art Curator and Art Investment

- Governmental Agencies

- Museum, Gallery Internships & Select Fieldwork in the United States

- Internships and Field Experience outside the United States

- External Fellowships

- Internal (Dartmouth-Based) Fellowships

- How to choose where to apply?

- The Application

- Financial Aid, Fellowships, and Grants

- Tell Us Your Story

- News & Events

- Riley Lecture

- Rosenthal Lecture

- Visual Resources

- Acknowledgments

Search form

To receive a BA degree “with honors” from the Department of Art History, a student must engage in independent but supervised research, compose an honors thesis, and present a synopsis of their work at a public forum. The research must represent a significant contribution to a specific field of inquiry within the discipline. The Honors Program enables students to explore particular problems in depth, while working closely with a faculty mentor.

Art History students visit the Hood Museum of Art.

So you think you want to write an Honors Thesis in Art History?

That’s great! In electing to write a thesis in Art History you will be joining a select group of advanced majors who have capped their Dartmouth experience with the exciting, challenging, and ultimately very rewarding undertaking of conducting advanced research on the topic of their choice.

The thesis is part of an Honors Program in the Department of Art History. Students who succeed will graduate with either Honors or, in some cases, High Honors on their diplomas.