The Art of Listening: Communication Skill Essay

Introduction.

Communication is a complex process that involves encoding and decoding of information. Listening, which is one of the communication elements, determines how effective the communication process is. Most people do not know how they can improve their listening skills in order to perfect communication. The process of improving listening requires one to develop a specific point of view to use in evaluating a message’s content. Among all communication skills, the art of listening is less emphasized. In most cases when dealing with communication skills problems, most people overlook listening (McKelvie, 2009). It is however important for communicators to understand that listening promotes good communication. As a good listener, one is required to differentiate the speaker’s emotional and delivery elements from the substance and content of the message (McKelvie, 2009). Most people are unable to overcome the distraction associated with the speaker’s emotional elements and thus end up receiving the wrong information.

To avoid being distracted by delivery and emotional elements which tend to cover the message’s content, it is important for a listener to learn how to differentiate facts and ideas. Generally, a listener should understand that listening entails more than message delivery. When listening, a listener should be keen to identify the core information. To avoid emotional element distraction, it’s important for a listener to bear in mind that emotional and delivery elements are not included in the message as elements for emphasizing the substance of the message, but rather as elements to help one in identifying the main substance of the message.

According to McKelvie, (2009), a listener should try to identify the content of message rather than dwelling on how the message is delivered. To avoid distraction by the delivery and emotional elements a listener should develop a habit of developing responses about the issues being discussed from the speaker’s messages. In addition, to be more focused on the message’s content and substance rather than its emotional elements, a listener should always try to find the answers for any questions arising from the speech.

Another way through which a listener can learn how to improve communication is by trying to analyse the message or speech’s content from someone else’s point of view (McKelvie, 2009). Analysing the message using a different person’s point of view increases the listener’s horizon which enables him to have a better understanding of the specific topic. In order to avoid distractions when listening and improve on identifying the message content, a listener should learn when and how to focus on facts. Listeners should always bear in mind that facts are generated from ideas (McKelvie, 2009). Since the process of identifying facts is a complex one, listeners need to learn how to give the speaker undivided attention. Making notes while listening can help a listener improve his listening skills (McKelvie, 2009).

As a way of lowering distraction by the emotional and delivery elements of the message and focus more on the content of the message, a listener should learn how to relate the message delivery system with message content. A good listener should be in a position to differentiate ideas and employ this skill in analysing the message’s content. A listener should be in a position to identify some of the emotional and delivery elements such as biased perspective and environmental factors that are most likely to cause him to have a distracted attention while listening. One strategy through which a listener can avoid message distractions is by learning to focus mainly on facts rather than ideas (McKelvie, 2009).

McKelvie, R., (2009). Listen Better to improve relationships . Suite101 publishers.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, December 26). The Art of Listening: Communication Skill. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-art-of-listening-communication-skill/

"The Art of Listening: Communication Skill." IvyPanda , 26 Dec. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/the-art-of-listening-communication-skill/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'The Art of Listening: Communication Skill'. 26 December.

IvyPanda . 2021. "The Art of Listening: Communication Skill." December 26, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-art-of-listening-communication-skill/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Art of Listening: Communication Skill." December 26, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-art-of-listening-communication-skill/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Art of Listening: Communication Skill." December 26, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-art-of-listening-communication-skill/.

- The Discrepancy Between an Original Psychological Article and Its Representation

- Exxon Mobile Company's Communication Strategy

- Henry Jenkins’ Theory of Convergence Culture

- Analysing a community development

- Designing a Sufficient Storyboard

- Distractions While Studying: Advantages and Disadvantages of Distraction

- Whaling is Unethical Socially: Analysing the Problem

- Analysing The Lesson By Tim Bedley

- Measuring Beliefs About Distraction by Senn and Radomsky

- Analysing Customers Through Mosaic

- Ability to Convey Verbal Messages

- Types of Conflicts and Ways to Resolve Them

- Analyzing Messages in Communications: E-Mail Examples

- The Communication Needs of the Shawnee Indian Tribe

- Facilitation Technique: A Framework for Efficient Communication

Husband and Wife (detail, 1945) by Milton Avery. Gift of Mr and Mrs Roy R Neuberger. Photo by Allen Phillips/ Wadsworth Atheneum

The art of listening

To listen well is not only a kindness to others but also, as the psychologist carl rogers made clear, a gift to ourselves.

by M M Owen + BIO

Writing in Esquire magazine in 1935, Ernest Hemingway offered this advice to young writers: ‘When people talk, listen completely… Most people never listen.’ Even though Hemingway was one of my teenage heroes, the realisation crept up on me, somewhere around the age of 25: I am most people. I never listen.

Perhaps never was a little strong – but certainly my listening often occurred through a fog of distraction and self-regard. On my worst days, this could make me a shallow, solipsistic presence. Haltingly, I began to try to reach inside my own mental machinery, marshal my attention differently, listen better. I wasn’t sure what I was doing; but I had crossed paths with a few people who, as a habit, gave others their full attention – and it was powerful. It felt rare, it felt real; I wanted them around.

As a culture, we treat listening as an automatic process about which there is not a lot to say: in the same category as digestion, or blinking. When the concept of listening is addressed at any length, it is in the context of professional communication; something to be honed by leaders and mentors, but a specialisation that everyone else can happily ignore. This neglect is a shame. Listening well, it took me too long to discover, is a sort of magic trick: both parties soften, blossom, they are less alone.

Along the way, I discovered that Carl Rogers, one of the 20th century’s most eminent psychologists, had put a name to this underrated skill: ‘active listening’. And though Rogers’s work was focused initially on the therapeutic setting, he drew no distinction between this and everyday life: ‘Whatever I have learned,’ he wrote, ‘is applicable to all of my human relationships.’ What Rogers learnt was that listening well – which necessarily involves conversing well and questioning well – is one of the most accessible and most powerful forms of connection we have.

T he paucity of my listening powers dawned on me as a byproduct of starting to meditate. This is not to make some claim to faux enlightenment – simply to say that meditation is the practice of noticing what you notice, and meditators tend to carry this mindset beyond the yoga mat, and begin to see their own mind more clearly. Among a smorgasbord of other patterns and quirks, what I saw was a self that, too often, didn’t listen.

The younger me enjoyed conversation. But a low, steady egoism meant that what I really enjoyed was talking. When it was someone else’s turn to talk, the listening could often feel like a chore. I might be passively absorbing whatever was being said – but a greater part of me would be daydreaming, reminiscing, making plans. I had a habit of interrupting, in the rather masculine belief that, whatever others had to say, I could say better for them. Sometimes, I would zone out and tune back in to realise that I’d been asked a question. I had a horrible habit, I saw, of sitting in silent linguistic craftsmanship, shaping my answer for when my turn came around – and only half-listening to what I’d actually be responding to.

The exceptions to this state of affairs, I began to see, were situations where there existed self-interest. If the subject was me, or material that might be of benefit to me, my attention would automatically sharpen. It was very easy to listen to someone explaining what steps I needed to take to ace a test or make some money. It was easy to listen to juicy gossip, particularly of the kind that made me feel fortunate or superior. It was easy to listen to debates on topics where I had a burning desire to be right. It was easy to listen to attractive women.

Bad listening signals to the people around you that you don’t care about them

On bad days, this attentional autopilot constricted me. On topics of politics or philosophy, this made me a bore and a bully. People avoided disagreeing with me on anything, even trivial points, because they knew it would balloon into annoyance and a failure to listen to their reasoning. In my personal life, too often, I could forget to support or lift up those around me. The flipside of not listening is not questioning – because, when you don’t want to listen, the last thing you want to do is trigger the exact scenario in which you are most expected to listen. And so I didn’t ask my friends serious questions often enough. I liked jokes, and I liked gossip; but I’d forget to ask them the real stuff. Or I’d ask them things they’d already told me a week ago. Or forget to ask about their recent job interview or break-up.

This is where bad listening does the most damage: it signals to the people around you that you don’t care about them, or you do but only in a skittish, flickering sort of a way. And so people become wary of opening up, or asking for advice, or leaning on you in the way that we lean on those people we truly believe to be big of heart.

All of the above makes for rather a glum picture, I know. I don’t want to overstate things. I wasn’t a monster. I cared for people and, when I concentrated, I could show it. I was liked, I made my way in the world, I apparently possessed what we call charisma. Plenty of the time, I listened fine. But this may be precisely the point: you can coast along in life as a bad listener. We tend to forgive it, because it’s common.

Kate Murphy, in her book You’re Not Listening (2020), frames modern life as particularly antagonistic to good listening:

[W]e are encouraged to listen to our hearts, listen to our inner voices, and listen to our guts, but rarely are we encouraged to listen carefully and with intent to other people.

Why do we accept bad listening? Because, I think, listening well is hard, and we all know it. Like all forms of self-improvement, breaking this carapace requires intention, and ideally guidance.

W hen I discovered Rogers’s writings on listening, it was confirmation that, in many conversations, I had been getting it all wrong. When listening well, wrote Rogers and his co-author Richard Evans Farson in 1957, the listener ‘does not passively absorb the words which are spoken to him. He actively tries to grasp the facts and the feelings in what he hears, and he tries, by his listening, to help the speaker work out his own problems.’ This was exactly the stance I had only rarely adopted.

Born in 1902 – in the same suburb of Chicago as Hemingway, three years earlier – Rogers had a strict religious upbringing. As a young man, he seemed destined for the ministry. But in 1926, he crossed the road from Union Theological Seminary to Columbia University, and committed himself to psychology. (At this time, psychology was a field so new and so in vogue that, in 1919, during negotiations for the Treaty of Versailles, Sigmund Freud had secretly advised Woodrow Wilson’s ambassador in Paris.)

Rogers’s early work was focused on what were then called ‘delinquent’ children; but, by the 1940s, he was developing a new approach to psychotherapy, which came to be termed ‘humanistic’ and ‘person-centred’. Unlike Freud, Rogers believed that all of us possess ‘strongly positive directional tendencies’. Unhappy people, he believed, were not broken; they were blocked. And as opposed to the then-dominant modes of psychotherapy – psychoanalysis and behaviourism – Rogers believed that a therapist should be less a problem-solver, and more a sort of skilled midwife, drawing out solutions that already existed in the client. All people possess a deep urge to ‘self-actualise’, he believed, and it is the therapist’s job to nurture this urge. They were there to ‘release and strengthen the individual, rather than to intervene in his life’. Key to achieving this goal was careful, focused, ‘active’ listening.

That this perspective doesn’t seem particularly radical today is a testament to Rogers’s legacy. As one of his biographers, David Cohen, writes , Rogers’s therapeutic philosophy ‘has become part of the fabric of therapy’. Today, in the West, many of us believe that going to therapy can be an empowering and positive move, rather than an indicator of crisis or sickness. This shift owes a great deal to Rogers. So too does the expectation that a therapist will allow themselves to enter into our thinking, and express a careful but tangible empathy. Where Freud focused on the mind in isolation, Rogers valued more of a merging of minds – boundaried, but intimate.

On bad days, I would wait hawk-like for things I could correct or belittle

Active listening, for Rogers, was essential to creating the conditions for growth. It was one of the key ingredients in making another person feel less alone, less stuck, and more capable of self-insight.

Rogers held that the basic challenge of listening is this: consciousnesses are isolated from one another, and there are thickets of cognitive noise between them. Cutting through the noise requires effort. Listening well ‘requires that we get inside the speaker, that we grasp, from his point of view , just what it is he is communicating to us.’ This empathic leap is a real effort. It is much easier to judge another’s point of view, analyse it, categorise it. But to put it on, like a mental costume, is very hard. As a teenager, I was a passionate atheist and a passionate Leftist. I saw things as very simple: all believers are gullible, and all conservatives are psychopaths, or at minimum heartless. I could hold to my Manichean view precisely because I had made no effort to grasp anyone else’s viewpoint.

Another of my old mental blocks, also flagged by Rogers, is the instinct that anyone I’m talking to is likely dumber than me. This arrogance is terrible for any attempt at listening, as Rogers recognises: ‘Until we can demonstrate a spirit which genuinely respects the potential worth of an individual,’ he writes, we won’t be good listeners. Previously, on bad days, I would wait hawk-like for things I could correct or belittle. I would look for clues that this person was wrong, and could be made to feel wrong. But as Rogers writes, to listen well, we ‘must create a climate which is neither critical, evaluative, nor moralising’.

‘Our emotions are often our own worst enemies when we try to become listeners,’ he wrote. In short, a great deal of bad listening comes down to lack of self-control. Other people animate us, associations fly, we are pricked by ideas. (This is why we have built careful social systems around not discussing such things as religion or politics at dinner parties.) When I was 21, if someone suggested that some pop music was pretty good, or capitalism had some redeeming features, I was incapable of not reacting. This made it very hard for me to listen to anyone’s opinion but my own. Which is why, Rogers says, one of the first skills to learn is non-intervention. Patience. ‘To listen to oneself,’ he wrote, ‘is a prerequisite to listening to others.’ Here, the analogy with meditation is clear: don’t chase every thought, don’t react to every internal event, stay centred. Today, in conversation, I try to constantly remind myself: only react, only intervene, when invited or when it will obviously be welcome. This takes practice, possibly endless practice.

And when we do intervene, following Rogers, we must resist the ever-present urge to drag the focus of the conversation back to ourselves. Sociologists call this urge ‘the shift response’. When a friend tells me they’d love to visit Thailand, I must resist the selfish pull to leap in with Oh yeah, Thailand is great, I spent Christmas in Koh Lanta once, did I ever tell you about the Muay Thai class I did? Instead, I must stay with them: where exactly do they want to go, and why? Sociologists call this ‘the support response’. To listen well is to step back, keep the focus with someone else.

A nice example of Rogers’s approach, taken from his career, is his experience during the Second World War. Rogers was asked by the US Air Force to assess the psychological health of gunners, among whom morale appeared low. By being patient, and nonjudgmental, and gentle with his attention, Rogers discovered that the gunners had been bottling up one of their chief complaints: they resented civilians. Returning to his hometown and attending a football game, reported one pilot, ‘all that life and gaiety and luxury – it makes you so mad’. Rogers didn’t suggest any drastic intervention, or push any change in view. He recommended that the men be allowed to be honest about their anger, and process it openly, without shame. Their interlocutors, Rogers said, should begin by simply listening to them – for as long as it took, until they were unburdened. Only then should they respond.

Much like meditating, listening in this way takes work. It may take even more work outside the therapy room, in the absence of professional expectation. At all times, for almost all of us, our internal monologue is running, and it is desperate to spill from our brain onto our tongue. Stemming the flow requires intention. This is necessary because, even when we think an intervention is positive, it may be self-centred. We might not feel it, Rogers says, but, typically, when we offer our interpretation or input, ‘we are usually responding to our own needs to see the world in certain ways’. When I first began to observe myself as a listener, I saw how difficult I found it to simply let people finish their sentences. I noticed the infinite wave of impatience on which my attention rode. I noticed the slippery temptation of asking questions that were not really questions at all, but impositions of opinion disguised as questions. The better road, I began to see, was to stay silent. To wait.

The active listener’s job is to simply be there, to focus on ‘thinking with people instead of for or about them’. This thinking with requires listening for what Rogers calls ‘total meaning’. This means registering both the content of what they are saying, and (more subtly) the ‘ feeling or attitude underlying this content’. Often, the feeling is the real thing being expressed, and the content a sort of ventriloquist’s dummy. Capturing this feeling involves real concentration, especially as nonverbal cues – hesitation, mumbling, changes in posture – are crucial. Zone out, half-listen, and the ‘total meaning’ will entirely elude us.

Everyone wants to be listened to. Why else the cliché that people fall in love with their therapists?

And though the bad listener loves to internally multitask while someone else is talking, faking it won’t work. As Rogers writes, people are alert to the mere ‘pretence of interest’, resenting it as ‘empty and sterile’. To sincerely listen means to marshal a mixture of agency, compassion, attention and commitment. This ‘demands practice’, Rogers said, and ‘may require changes in our own basic attitudes’.

Rogers’s theories were developed in a context where one person is attempting, explicitly, to help another person heal and grow. But Rogers was always explicit about the fact that his work was ‘about life’. Of his theories, he said that ‘the same lawfulness governs all human relationships’.

I think I started off from a lower point; by nature, I think my brain tends toward distraction and self-regard. But one would not need to be a bad listener to benefit from Rogers’s ideas. Even someone whose autopilot is an empathetic, interested listener can find much in his work. Rogers did more than anyone else to explore listening, systemise its dynamics, and record his professional explorations.

Certainly, being a good listener had an impact on Rogers’s own life. As another of his biographers, Howard Kirschenbaum, told me, Rogers discovered that ‘listening empathically to others was enormously healing and freeing, in both therapy and other relationships’. At his 80th birthday party, a cabaret was staged in which two Carl Rogers impersonators listened to one another in poses of exaggerated empathy. The well-meaning gag was a compliment; in a somewhat rare case of intellectuals actually embodying the ideas they espouse, Rogers was remembered as an excellent listener by everyone who knew him. Despite the kind of foibles that can weigh down any life – a reliance on alcohol, a frustration with monogamy – Rogers appears to have been a decent man: warm, open, and never cruel.

That he was able to carry his theories into his life should give encouragement, even to those of us who aren’t world-famous psychologists. Everyone wants to be listened to. Why else the cliché that people fall in love with their therapists? Why else does all seduction start with riveted attention? Consider your own experience, and you will likely find a direct correlation between the people you feel love you, and the people who actually listen to the things you say. The people who never ask us a thing are the people we drift away from. The people who listen so hard that they pull new things out of us – who hear things we didn’t even say – are the ones we grab on to for life.

P erhaps above all, Rogers understood the stakes involved in listening well. All of us, when we are our best selves, want to bring growth to the people we choose to give our time to. We want to help them unlock themselves, stand taller, think better. The dynamic may not be as direct as with a therapist; there is more of an equal footing – but when our relationships are healthy, we want those around us to thrive. Listening well, Rogers showed, is the simplest route there. Be with people in the right way, and they become ‘enriched in courage and self-confidence’. They feel the releasing glow of attention, and develop an ‘underlying confidence in themselves’. If we don’t want this for our friends, then we are not their friends.

Indeed, such is the generosity of active listening that one can view the practice as one that borders on the spiritual. Though Rogers traded theology for psychology in his early 20s, he always maintained an interest in spirituality. He enjoyed the work of Søren Kierkegaard , an existentialist Christian; and, over the years, he had public discussions with the theologians Paul Tillich and Martin Buber . In successful therapy sessions, said Rogers, both therapist and client can find themselves in ‘a trance-like feeling’ where ‘there is, to borrow Buber’s phrase, a real “I-Thou” relationship’. Of his relationship to his clients, Rogers said: ‘I would like to go with him on the fearful journey into himself.’

Perhaps this is a bit rich for you; perhaps you would rather frame active listening as simply good manners, or a neat interpersonal hack. The point is: really listening to others might be an act of irrational generosity. People will eat up your attention; it could be hours or years before they ever turn the same attention back on you. Sometimes, joyfully, your listening will yield something new, deliver them somewhere. Sometimes, the person will respond with generosity of their own, and the reciprocity will be powerful. But often, nothing. Only rarely will people notice, let alone thank you, for your efforts. Yet this generosity of attention is what people deserve.

And lest this all sound a bit pious – active listening is not pure altruism. Listening well, as Rogers said, is ‘a growth experience’. It allows us to get the best of others. The carousel of souls is endless. People have deeply felt and fascinating lives, and they can enfranchise us to worlds we would never otherwise know. If we truly listen, we expand our own intelligence, emotional range, and sense that the world remains open to discovery. Active listening is a kindness to others but, as Rogers was always quick to make clear, it is also a gift to ourselves.

Brains learn from other brains, and listening well is the simplest way to draw a thread, open a channel

Rogers became a hero of the 1960s counterculture . He admired their utopian dreams of psychic liberation and uninhibited communication; late in life, he was drawn to the New Age writings of Carlos Castañeda. All of this speaks to one of the key critiques of Rogers’s philosophy, both during his lifetime and today: that he was too optimistic. Rogers recognised himself that he was, in Cohen’s words, ‘incorrigibly positive’. His critics called him a sort of Pollyanna of the mind, and thought him naive for believing that such simple interventions as empathy and listening could trigger transformation in people. (Perhaps certain readers will harbour similar critiques about my own beliefs as expressed here.)

Those inclined to agree with this assessment of Rogers will probably think that I have overstated the case. Listening as love? Listening as spiritual practice? But in my own life, a renewed approach to listening has improved how I relate to others, and I now believe listening is absurdly under-discussed. Good listening is complex, subtle, slippery – but it is also right here, it lives in us, and we can work on it every day. Unlike the abstractions of so much of ethics and so much of philosophy, our listening is there to be honed, every day. Like a muscle, it can be trained. Like an intellect, it can be tested. In the very same moment, it can spur both our own growth and the growth of others. Brains learn from other brains, and listening well is the simplest way to draw a thread, open a channel. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that I couldn’t write nonfiction that anyone else actually wanted to read until I began trying to truly listen.

‘The greatest compliment that was ever paid me,’ said Henry David Thoreau, ‘was when one asked me what I thought, and attended to my answer.’ Left on autopilot, I can still be a bad listener. I’ll interrupt, finish sentences, chivvy people along. I suspect many of the people I know still find me to be, on balance, an average listener. But I try! With anyone I can impact – and especially those whose souls I can help to light up – I follow Rogers; I offer as much ‘of safety, of warmth, of empathic understanding, as I can genuinely find in myself to give.’ And I open myself to whatever I can learn. I fail in my attentions, again and again. But I tune back in, again and again. I believe it is working.

Consciousness and altered states

A reader’s guide to microdosing

How to use small doses of psychedelics to lift your mood, enhance your focus, and fire your creativity

Tunde Aideyan

The scourge of lookism

It is time to take seriously the painful consequences of appearance discrimination in the workplace

Andrew Mason

Thinkers and theories

Our tools shape our selves

For Bernard Stiegler, a visionary philosopher of our digital age, technics is the defining feature of human experience

Bryan Norton

Family life

A patchwork family

After my marriage failed, I strove to create a new family – one made beautiful by the loving way it’s stitched together

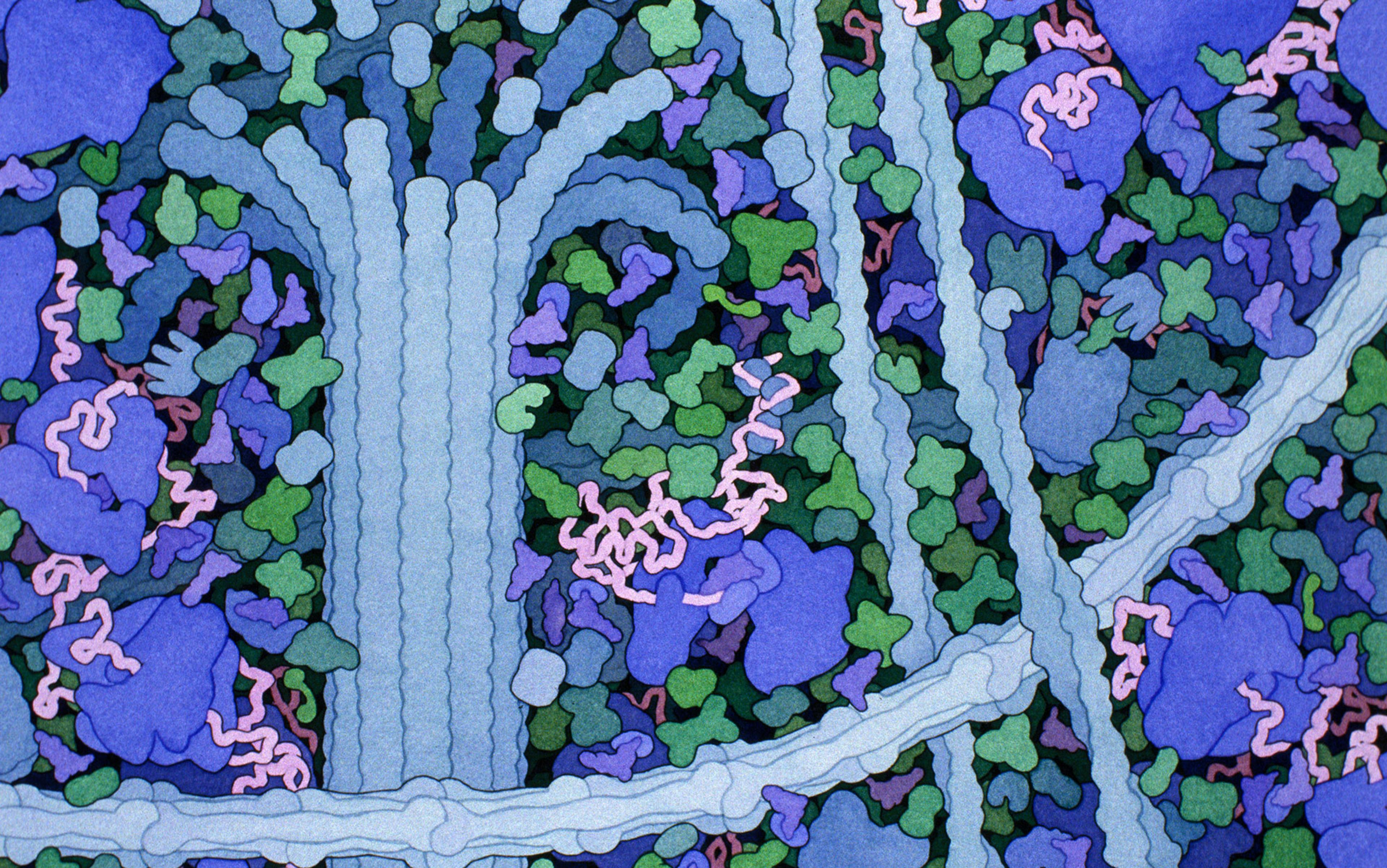

The cell is not a factory

Scientific narratives project social hierarchies onto nature. That’s why we need better metaphors to describe cellular life

Charudatta Navare

Stories and literature

Terrifying vistas of reality

H P Lovecraft, the master of cosmic horror stories, was a philosopher who believed in the total insignificance of humanity

Sam Woodward

Home — Essay Samples — Education — Listening — The Art of Active Listening

The Art of Active Listening

- Categories: Listening Perception Skills

About this sample

Words: 469 |

Published: Jan 29, 2019

Words: 469 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

- Comprehensive (Informational) Listening:- Students listen for the content of the message.

- Critical (Evaluative) Listening:- Students judge the message.

- Appreciative (Aesthetic) Listening:- Students listen for enjoyment.

- Therapeutic (Empathetic) Listening:-Students listen to support others but not judge them.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Education Psychology Life

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1304 words

2 pages / 789 words

1 pages / 360 words

2 pages / 921 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Distorted listening is a phenomenon that occurs when individuals misinterpret or misunderstand the messages being communicated to them. This can happen for a variety of reasons, including cognitive biases, emotional responses, [...]

Blosser (1988) agrees on what B. Neuman says when announcing “a positive relationship between television watching and reading comprehension results for Hispanic students”. In addition, (Koskinnen, Wilson and Gambreel; 1987) [...]

Even though the Earth seems like it is completely stable, the environment is being damaged. For example, because of forest destruction, floods occur since there are no trees to drink the rain. The people of the world have [...]

High-performance liquid chromatography is an analytical technique used to separate, identify, and quantify each component in a mixture. The liquid solvent containing the sample mixture passes through a column filled with a [...]

The importance of critical thinking can not be overrated. Critical thinking is a valuable tool that is used in every aspect of life. There is always a problem to be solved or an important decision to be made. Defining and [...]

Although they are very young, the responsibility of securing their future has been given solely to students. They receive guidance from parents and teachers but most of the work must be done by them. Therefore, to be able to [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Books & Audio

- The Art of Listening

It is through this creative process that we at once love and are loved.

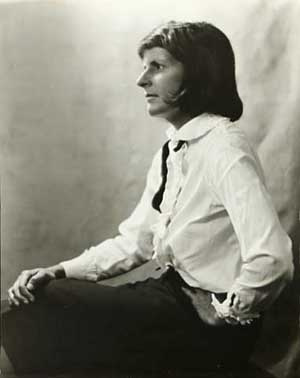

by Brenda Ueland Sunday, October 25, 1992 San Jose Mercury News

I WANT to write about the great and powerful thing that listening is. And how we forget it. And how we don’t listen to our children, or those we love. And least of all — which is so important, too — to those we do not love. But we should. Because listening is a magnetic and strange thing, a creative force. Think how the friends that really listen to us are the ones we move toward, and we want to sit in their radius as though it did us good, like ultraviolet rays.

This is the reason: When we are listened to, it creates us, makes us unfold and expand. Ideas actually begin to grow within us and come to life. You know how if a person laughs at your jokes you become funnier and funnier, and if he does not, every tiny little joke in you weakens up and dies. Well, that is the principle of it. It makes people happy and free when they are listened to. And if you are a listener, it is the secret of having a good time in society (because everybody around you becomes lively and interesting), of comforting people, of doing them good. Who are the people, for example, to whom you go for advice? Not to the hard, practical ones who can tell you exactly what to do, but to the listeners; that is, the kindest, least censorious, least bossy people you know. It is because by pouring out your problem to them, you then know what to do about it yourself. When we listen to people there is an alternating current that recharges us so we never get tired of each other. We are constantly being re-created.

When people listen, creative waters flow

Now, there are brilliant people who cannot listen much. They have no ingoing wires on their apparatus. They are entertaining, but exhausting, too. I think it is because these lecturers, these brilliant performers, by not giving us a chance to talk, do not let this little creative fountain inside us that begins to spring and cast up new thoughts and unexpected laughter and wisdom. That is why, when someone has listened to you, you go home rested and lighthearted. Now this little creative fountain is in us all. It is the spirit, or the intelligence, or the imagination — whatever you want to call it. If you are very tired, strained, have no solitude, run too many errands, talk to too many people, drink too many cocktails, this little fountain is muddied over and covered with a lot of debris. The result is you stop living from the center, the creative fountain, and you live from the periphery, from externals. That is, you go along on mere willpower without imagination. It is when people really listen to us, with quiet, fascinated attention, that the little fountain begins to work again, to accelerate in the most surprising way. I discovered all this about three years ago, and truly it made a revolutionary change in my life. Before that, when I went to a party, I would think anxiously: “Now try hard. Be lively. Say bright things. Talk. Don’t let down.” And when tired, I would have to drink a lot of coffee to keep this up. Now before going to a party, I just tell myself to listen with affection to anyone who talks to me, to be in their shoes when they talk; to try to know them without my mind pressing against theirs, or arguing, or changing the subject. Sometimes, of course, I cannot listen as well as others. But when I have this listening power, people crowd around and their heads keep turning to me as though irresistibly pulled. By listening I have started up their creative fountain. I do them good. Now why does it do them good? I have a kind of mystical notion about this. I think it is only by expressing all that is inside that purer and purer streams come. It is so in writing. You are taught in school to put down on paper only the bright things. Wrong. Pour out the dull things on paper too — you can tear them up afterward — for only then do the bright ones come. If you hold back the dull things, you are certain to hold back what is clear and beautiful and true and lively.

Who are the people, for example, to whom you go for advice? Not to the hard, practical ones who can tell you exactly what to do, but to the listeners; that is, the kindest, least censorious, least bossy people you know.

Women listen better

I think women have this listening faculty more than men. It is not the fault of men. They lose it because of their long habit of striving in business, of self-assertion. And the more forceful men are, the less they can listen as they grow older. And that is why women in general are more fun than men, more restful and inspiriting.

Now this non-listening of able men is the cause of one of the saddest things in the world — the loneliness of fathers, of those quietly sad men who move along with their grown children like remote ghosts. When my father was over 70, he was a fiery, humorous, admirable man, a scholar, a man of great force. But he was deep in the loneliness of old age and another generation. He was so fond of me. But he could not hear me — not one word I said, really. I was just audience. I would walk around the lake with him on a beautiful afternoon and he would talk to me about Darwin and Huxley and higher criticism of the Bible. “Yes, I see, I see,” I kept saying and tried to keep my mind pinned to it, but I was restive and bored. There was a feeling of helplessness because he could not hear what I had to say about it. When I spoke I found myself shouting, as one does to a foreigner, and in a kind of despair that he could not hear me. After the walk I would feel that I had worked off my duty and I was anxious to get him settled and reading in his Morris chair, so that I could go out and have a livelier time with other people. And he would sigh and look after me absentmindedly with perplexed loneliness. For years afterward I have thought with real suffering about my father’s loneliness. Such a wonderful man, and reaching out to me and wanting to know me! But he could not. He could not listen. But now I think that if only I had known as much about listening then as I do now, I could have bridged the chasm between us. To given an example: Recently, a man I had not seen for 20 years wrote me. He was an unusually forceful man and had made a great deal of money. But he had lost his ability to listen. He talked rapidly and told wonderful stories and it was just fascinating to hear them. But when I spoke — restlessness: “Just hand me that, will you?… Where is my pipe?” It was just a habit. He read countless books and was eager to take in ideas, but he just could not listen to people.

Listened patiently

Well, this is what I did. I was more patient — I did not resist his non-listening talk as I did my father’s. I listened and listened to him, not once pressing against him, even in thought, with my own self-assertion.

I said to myself: “He has been under a driving pressure for years. His family has grown to resist his talk. But now, by listening, I will pull it all out of him. He must talk freely and on and on. When he has been really listened to enough, he will grow tranquil. He will begin to want to hear me.” And he did, after a few days. He began asking me questions. And presently I was saying gently: “You see, it has become hard for you to listen.” He stopped dead and stared at me. And it was because I had listened with such complete, absorbed, uncritical sympathy, without one flaw of boredom or impatience, that he now believed and trusted me, although he did not know this. “Now talk,” he said. “Tell me about that. Tell me all about that.” Well, we walked back and forth across the lawn and I told him my ideas about it. “You love your children, but probably don’t let them in. Unless you listen, you can’t know anybody. Oh, you will know facts and what is in the newspapers and all of history, perhaps, but you will not know one single person. You know, I have come to think listening is love, that’s what it really is.” Well, I don’t think I would have written this article if my notions had not had such an extraordinary effect on this man. For he says they have changed his whole life. He wrote me that his children at once came closer; he was astonished to see what they are; how original, independent, courageous. His wife seemed really to care about him again, and they were actually talking about all kinds of things and making each other laugh.

Family tragedies

For just as the tragedy of parents and children is not listening, so it is of husbands and wives. If they disagree they begin to shout louder and louder — if not actually, at least inwardly — hanging fiercely and deafly onto their own ideas, instead of listening and becoming quieter and more comprehending. But the most serious result of not listening is that worst thing in the world, boredom; for it is really the death of love. It seals people off from each other more than any other thing. Now, how to listen. It is harder than you think. Creative listeners are those who want you to be recklessly yourself, even at your very worst, even vituperative, bad-tempered. They are laughing and just delighted with any manifestation of yourself, bad or good. For true listeners know that if you are bad-tempered it does not mean that you are always so. They don’t love you just when you are nice; they love all of you. In order to listen, here are some suggestions: Try to learn tranquility, to live in the present a part of the time every day. Sometimes say to yourself: “Now. What is happening now? This friend is talking. I am quiet. There is endless time. I hear it, every word.” Then suddenly you begin to hear not only what people are saying, but also what they are trying to say, and you sense the whole truth about them. And you sense existence, not piecemeal, not this object and that, but as a translucent whole. Then watch your self-assertiveness. And give it up. Remember, it is not enough just to will to listen to people. One must really listen. Only then does the magic begin. We should all know this: that listening, not talking, is the gifted and great role, and the imaginative role. And the true listener is much more beloved, magnetic than the talker, and he is more effective and learns more and does more good. And so try listening. Listen to your wife, your husband, your father, your mother, your children, your friends; to those who love you and those who don’t, to those who bore you, to your enemies. It will work a small miracle. And perhaps a great one.

We should all know this: that listening, not talking, is the gifted and great role, and the imaginative role. And the true listener is much more beloved, magnetic than the talker, and he is more effective and learns more and does more good.

Brenda Ueland, a prolific Minnesota author and columnist, died in 1985. A collection of her essays, “Strength to Your Sword Arm: Selected Writings by Brenda Ueland” was released earlier this month. Copyright © 1992 by The Estate of Brenda Ueland. Reprinted by permission of HolyCow! Press, Box 3170, Mt. Royal Station, Duluth, Minn. 55803.

Download the pdf version of The Art of Listening

About the Author

The Power & Presence website is designed to help you discover ways to resolve conflict, build relationships, and become a more powerful and present human being.

Judy Ringer is the author.

You’re welcome to reprint all or parts of this article as long as you include “About the Author” text, and a link to PowerandPresence.com

- We Have to Talk: A Step-by-Step Checklist for Difficult Conversations

- Feedback or Criticism? A Toolbox for Dealing with Criticism in the Workplace

- Top 6 Ineffective Leadership Traits

- Conflict Resolution for Kids: Breathe, Learn, Talk

- Fear of Failure and the Art of Ukemi: 3 Lessons from Aikido

- Purposeful Communication

- Being Heard: 6 Strategies for Getting Your Point Across

- Frequently Asked Questions About Aikido, Centering, Conflict and Communication

- Difficult People: 3 Questions to Help You Turn Your Tormentors into Teachers

- Aikido, Resistance, and Flawless Consulting

- Tips and Strategies for Workplace Conflict: An Interview with Judy Ringer

- Are You Worried? 4 Steps to Peace of Mind

- Taking Myself Too Seriously: Suggestions for Reclaiming Perspective

- How to Keep a Good Employee: Look, Listen, Learn

- Conquering Performance Anxiety: A 6-Step Checklist

- Hidden Gifts: What Aikido Can Teach Us About Conflict

- The Manager as Mediator: First Manage You

- Six-Step Checklist for Holding Powerful Conversations

About This Site

The Power & Presence site is designed to help the reader discover answers, skills, and methods to resolve conflict, build relationships, and become a more powerful and present human being. Judy Ringer is the author.

Aikido is the metaphor we use to help you be more intentional with your ki , communicate purposefully, and create your life and work from center.

Ki (pronounced “key”) is Japanese for universal energy; it’s the central syllable in Aikido , which is often translated as “the way of blending with energy”.

This is an educational website with many free resources.

Ways to have Fun on the Site

- Use the customized search engine to explore a topic of interest.

- Visit the Bookstore .

- Explore and download Articles and Posts you like.

- If you republish, please include a link to PowerandPresence.com .

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 3 min read

The Art of Listening

The key skills needed to become a truly effective listener.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

We’re surrounded by talented people at work with great ideas to share. But listening is about more than angling your ear in someone’s direction. You have to really listen to what they say, understand what they mean and unearth how they feel. Try out these tips to improve your listening skills.

What Is Listening?

Listening and hearing are not the same thing. Listening is an active process, where you get meaning from what’s being said before you respond. Let’s explore ways to listen better.

Following the Speaker

Conversations, especially work chat, can be tough going. But if you find it difficult to keep your attention on the speaker, you can train yourself to focus by:

- Pausing to think of questions rather than your response. You’ll show you’re engaged, help the speaker open up and say what they really feel.

- Asking questions from what they’re saying shows you’re interested, builds rapport and helps you clarify their points. Questions such as, 'Did I get that right?' will also give you feedback if you’ve understood the speaker correctly. [1]

- Mentally round up key points . We think up to four times faster than we talk, so it’s easy to get impatient with a speaker's slow progress. [2] Instead of thinking about what you’re going to say next, use that spare brain power to sum up the speaker's main points. When they’ve finished talking, say something like, 'What I hear you saying is…' to find out if you’re on the same page.

Supporting the Speaker

A good listener can encourage a speaker to say what they really feel and help articulate themselves better. To do it, you can:

- Paraphrase – break down and frame what they’re saying in your own language. You’ll show you’re listening, force yourself to pay attention and get a clearer sense of what they’re saying.

- Spur on the speaker by saying things like 'go on', 'tell me more' or 'that’s interesting'. You can also repeat one of their phrases to encourage them to open up.

- Watch out for behavioral cues that reveal a gap between what a speaker is saying and what they really feel. For example, their words may convey confidence about an idea but their body language (gestures, posture, facial expressions) reveal underlying anxiety.

- Subtly mirror the speaker's body language to show interest and increase their confidence and empathy levels.

- Maintain eye contact , nod, raise eyebrows and lean forward to show interest. But be subtle and remember to concentrate on what they’re saying.

Reflective Listening

Reflective listening helps you really understand what’s being said, make a connection with the speaker and encourage more thought-provoking conversation. To master this skill, try:

- Asking open questions . So, 'How do you feel about work?' instead of 'Do you like it here?' These help you build on what you heard and continue the conversation.

- Developing empathy . To gain a deeper understanding of how the speaker feels, use phrases such as 'You felt X because Y?'

- Reflecting back the feelings of the speaker by saying something like 'So, you felt excited?' When asked a direct question, respond to the feeling that lies behind it.

Final Advice

Remember, listening isn’t just about fuelling a conversation. Where relevant, you can bring up what someone said hours, days or weeks later. It feels great when someone remembers something you said and brings it up later. What’s more, good listeners circle back around to follow up on key points or important issues. [3] By focusing on the speaker instead of yourself, you’ll get the information you need and become a better communicator.

[1] ‘5 Ways To Master The Art Of Listening’ (2013). Available at: https://www.americanexpress.com/en-us/business/trends-and-insights/articles/5-ways-to-master-the-art-of-listening/ (accessed July 27, 2023).

[2] Eugene Raudsepp, ‘The Art Of Listening Well’. Available at: https://www.inc.com/magazine/19811001/33.html (accessed July 27 July, 2023).

[3] Genevieve Conti, ‘How to Master the Art of Listening’ (2016). Available at: https://zapier.com/blog/become-a-better-listener/ (accessed July 27, 2023).

Join Mind Tools and get access to exclusive content.

This resource is only available to Mind Tools members.

Already a member? Please Login here

Team Management

Learn the key aspects of managing a team, from building and developing your team, to working with different types of teams, and troubleshooting common problems.

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Newest Releases

SWOT Analysis

SMART Goals

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

How to stop procrastinating.

Overcoming the Habit of Delaying Important Tasks

What Is Time Management?

Working Smarter to Enhance Productivity

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Virtual collaboration.

Choosing the right tools to collaborate online

Animated Video

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

The Art of Listening

Explorative listening as a way to be with others..

Posted March 26, 2019

A little over a year ago, my closest friends and I lost Dr. Jennifer Gonzales Shushereba. As is so often the case with deeply felt loss—whether that of a friend, or a grandparent, or a relationship—we struggled for some time to put into words just what it was about her that we’d forever be missing. In my work as a therapist, I’ve witnessed how the same soaring sources of beauty gifted by another’s presence serve as tortuous reminders of our loss. These reminders can evoke the deepest lows—the sort of lows that make us ache in a way that feels like we’re destined to break, as if the pain of getting through the tough stuff wasn’t so normally human, and as though getting through it weren’t possible.

It is, of course. What ultimately initiated the process of healing was being listened to by others— deeply listened to. Not surprisingly, this remains exactly the quality that I appreciated most in Jenn and serves as the topic of this post—not least because it’s a small pleasure that connects us deeply to others [1], but also because it’s so tremendously difficult to actually be this sort of listener. What follows is one attempt at distilling the core elements of this skill, inspired by the exemplar I loved so much.

The sort of listening Jenn (and close friends since) excelled at made it pretty clear that not all listening is the same. In what we might call responsive listening , the primary purpose is one of informational exchange or problem solving, and the listening itself manifests in permutational self-based if-this-then-that feedback patterns. For example, my friend answers a question about how they’d like to spend a sunny afternoon together. I then crunch this information against a backdrop of logistical concerns, my own desires, and so on—I respond, we negotiate some tricky timing around separate dinners post-sunset, and then we’re off to the park.

In negotiating an evening in the park and engaging in responsive listening , I must listen to my friend’s stated wish (information being exchanged) while considering my own (self-basis) in order to respond appropriately (feedback exchange) and arrive at our mutual goal: a shared afternoon prior to separate plans post-sunset. This sort of listening isn’t bad, even if it is perfunctory—indeed, all other human cooperation rests on our ability to communicate, and sometimes we really do just need to get things done. But let’s acknowledge for a second that this isn’t the sort of listening likely to be recalled so fondly by others in our absence, and it’s not the kind that we seek when we need to be vulnerable or venture into more emotional territory. It’s not the kind the forges connection in the way most of us seek.

Emotional intimacy involves a second, deeper form of listening—something we might call explorative listening . In this, the goal is simply to be with another person where they’re at as they speak. Sounds easy, right?

Not so much. It turns out this level of communication is much more difficult, and requires that we shed the template of responsive listening. In contrast, explorative listening is devoid of:

1. Obligatory and expected specific informational exchange or problem solving

2. Goals to be met by the end of the conversation

3. Reflexive self-driven responses to the other’s exchanges

Research has defined this sort of listening in differing ways (e.g., attentive listening [2], active listening [3], or interpersonal empathic listening [4], to name a few among the potential many), but the core features seem to be:

1. Other-focus/temporary exclusion of the self in the process

2. Use of verbal and nonverbal cues indicating attention , understanding, and nonjudgment

3. Curiosity without judgment (empathic exploration)

In a scenario where someone is expressing some discomfort at work, explorative listening shifts the focus away from one’s own desires or needs and toward the exploration of the other. Within this template, the conversation is free of personal goals, expectations of the other, or any self-interested need for the conversation to arrive at any point at all . Instead, responses are encouraging and nonjudgmental—nudging only towards further exploration and expression. In general, this is accomplished in the form of back channeling [3] (verbal and warm “mmhmm” and “yeah” statements, timed appropriately), or nonverbal gestures, like slow nodding, gently held eye contact, and relaxed posture.

Truly adept listeners mirror the physical position of their speakers, and match their vocal tones in gentler hues, effectively setting the stage for the namesake component of explorative listening: that of the exploration itself.

If what we’ve said through our actions above is as follows: “I’m here. I’m with you. You can be how you are, and I’ll just go along with you,” what comes next is where the richness lies: in explorative listening , we move with the speaker past the vagaries of first-draft dialogue [5] to what lies beneath. It’s not enough to hear that something at work was troubling—adept listeners are curious as to why this particular interaction ruffled the speaker so, and they gently prod. “Go on,” they might offer—or, “Hmmm, I wonder why that is?” At times, silent stillness may be the gesture that indicates a readiness for whatever comes next [5,6].

This process isn’t always easy—and it requires that the explorative listener actively rally against the egoism present in responsive listening. Perhaps, for example, encouraging another to explore their responses to conflict serves as a reminder of our own, of which we are somewhat embarrassed. In these moments, explorative listening’s true gift is that of selflessness; our focus on the other doesn’t preclude our own stuff—it just puts it on hold until the other has moved from wherever they picked it up to wherever they feel comfortable leaving it.

Being listened to in this way feels like a gift because it is. How often are we truly allowed the freedom to explore the messiness so present in our jumbled thoughts [7], or to actually be invited to explore our experiences alongside someone who makes it so clear they’re willing to go where we want to go and remain a steady balance to our own stumbling [8]? How often are we gifted another’s presence and witnessing without the (well-intentioned) interruptions which hallmark responsive listening and (at times) seem to insist that our turn is over, or that our divulsions have somehow become unpalatable or—perhaps worse— boring ?

For most of us, I’m guessing, the answer is “not often enough.” I’m guessing the opposite is ironically also true: that for all the good this feels to receive, so many of us (myself included) overlook the importance of giving it to others as we move throughout our days. This would seem remarkable were it not so wondrously human: there are only so many hours in a day, and at times it feels as though there just isn’t much left in the tank to give when the time comes to step up and switch from responsive to explorative.

Yet this is what I remember most about Jenn. Her form of hearing and being with others is difficult, sure—and yet it requires no particularly superhuman skill, even though most of us struggle to do it. It’s so incredibly meaningful, and yet seems rare—even though I’ve yet to meet someone who wouldn’t want another chance to experience this with Jenn, or to offer it to her in return.

And—at least in my case and like so many of the best things—it’s often not appreciated fully until we’re made aware of its loss. In losing Jenn, the remarkable sour has slowly transitioned to the (perhaps) inevitable bittersweet—for the past year, I’ve been at once crushed by the loss of her and the example of listening she saw fit to dispense so freely, and at the same time so sweetly reminded of this gift she’d given each time I’ve experienced it through others.

It’s as though she were at once both gone and still here.

Still listening.

Still gently reminding us to do this for others, for as long and as much as we can.

[1] The School of Life. Small Pleasures. (2016). London: The School of Life.

[2] Pasupathi, M., & Rich, B. (2005). Inattentive listening undermines self-verification in personal storytelling. Journal of Personality, 73 (4), 1051-1086.

[3] Kuhn, R., Bradbury, T.N., Nussbeck, F.W. & Bodenmann, G. (2018). The power of listening: Lending an ear to the partner during dyadic coping conversations. Journal of Family Psychology, 32 (6), 762-772.

[4] Rogers, C. R. (1951). Client-centered therapy, its current practice, implications, and theory. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

[5] The School of Life. On Being Nice. (2017). London: The School of Life.

[6] Maun, A. (2014). The art of doing almost nothing: how a core Taijiquan principle can help us to understand turning points in therapeutic processes. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 20 (2), 77-78.

[7] The School of Life. Self-Knowledge. (2017). London: The School of Life.

[8] The School of Life. What Is Psychotherapy? (2018). London: The School of Life.

David Kyle Bond, Ph.D. , is a lecturer at the University of California, Irvine in the Psychological Science department.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Gray Matter

9 Ways to Master the Art of Listening

by Aletheia · Dec 24, 2020 · 21 Comments

Everyone thinks they’re great listeners.

What’s easier than sitting down and just hearing what a person has to say, right?

Hearing isn’t necessarily listening, nor is it necessarily listening well .

As G.K. Chesterton said, “there’s a lot of difference between hearing and listening.”

The truth is, many people come to conversations with agendas, whether that is to make themselves be heard, or to make themselves not be heard, and to actually escape the conversation altogether. If you’re an introvert , you probably opt for the latter.

If you’re anything like me you probably find yourself on the receiving end of countless uninitiated conversations. Although you sit quietly listening to them, the fact is that you’d much prefer to be doing something else.

The problem with constantly feeling this way is that we never actually hear the people who speak to us. We don’t put our entire attention, interest or heart into listening and truly understanding them. And not only does this create alienation within us, but that alienation is felt by the other person as well.

The Art Of Listening

Just because you’re quiet and you let others do 75% of the talking, doesn’t mean you’re a good listener. And just because you’re good at talking and receiving what the other says, doesn’t mean you’re a great listener either.

How many times have you longed to be heard and understood only to have the receiving end ordering a pizza in the background, shuffling through papers or texting while you talk?

Being unheard results in feelings of disconnection and loneliness.

The need to be understood and listened to is a basic human need, along with food, water, and shelter. Yet, the sad reality is that most of us lack this basic life skill.

Listening is an art. It requires us to be patient, receptive, open-minded, and non-judgmental. It requires us to not put words in other people’s mouths, fill in gaps, or presume to understand the other person fully.

There is a certain Zen-like quality in practicing listening. Not only does it help us socially, but it also helps us spiritually as well.

Dissolve the shadows that obscure your inner Light in this weekly email-based membership! Perfect for any soul seeker serious about practicing ongoing shadow work and self-love.

Those who can listen to others well can listen to themselves deeply.

This is the foundation of self-awareness , self-love , and self-knowledge.

In fact, the art of listening is central to practices such as meditation and mindfulness. So why not hone this skill with others each day, and make the best opportunity of every moment you get?

How to Master the Art of Listening

Here’s how to bring this crucial life skill into your everyday existence:

1. Make Eye Contact

This first rule is very obvious but frequently forgotten. If you don’t look at the person while they’re speaking, you give them the impression that you don’t care what they say. In essence, it appears as though you don’t even care about them.

2. Don’t Interrupt

Let the person speak uninterrupted. To master the art of listening you need to halt any good thoughts that come to mind and let the person say everything they need to say. Often times people simply need someone to talk to, not someone who will butt in and give their own thoughts and opinions. The goal is to shine the spotlight on them , not you.

3. Practice “Active Listening”

The art of listening isn’t simply about staying quiet 100% of the time, it’s also about asking questions. These questions are for clarification, or for further explanation so that you can fully understand what the speaker is telling you. For instance, questions like these are brilliant: “Are you saying that _______”, “What I heard you say was ______”, “Did you mean that _______.”

4. Show You Understand

Sign up to our LonerWolf Howl newsletter

Get free weekly soul-centered guidance for your spiritual awakening journey! (100% secure.)

Another great way to show that you understand what the person is telling you is to nod. You can also make noises that show you’re in tune with what the person is saying such as “yes”, “yeah”, “mhmm”, “okay.” This seems trivial, but it’s important to not behave like a zombie and demonstrate some interest and comprehension.

5. Listen Without Thinking

In other words, listen without forming responses in your mind. Be wholehearted and listen to the entire message. It’s very tempting to fill the spaces, after all, our minds think around 800 words per minute, compared to 125-150 words we speak per minute. Don’t miss valuable information by letting your mind wander!

6. Listen Without Judgement

To effectively master the art of listening it’s extremely important to withhold any negative evaluations or judgments. Make it your goal to be open-minded as much as possible. After all, who wants to open up to a narrow-minded person? It also helps to be mindful of your “shut off” triggers, which are the specific words, looks, or situations that cause you to stop listening. This way, you can prevent yourself from shutting off in the future.

7. Listen To Non-Verbal Communication

About 60-75% of our communication is non-verbal. That’s a lot! In order to know whether to encourage the speaker, to open yourself more, or to be more supportive in your approach, it’s essential to know what the person’s body is saying. Do they display signs of discomfort? Are they wary of you? Does their body language align with their words?

8. Create A Suitable Environment

It can be difficult to listen to another person when the TV is screaming, your phone is buzzing and there are thousands of cars passing by. When you remove all of these distractions and find a quiet place to sit down and listen, it’s much easier to listen empathetically with an open mind and whole heart. Also, when you indicate it would be good to “find a quiet place,” you put importance in the person and what they have to say. Once again, you show care and consideration.

9. Observe Other People

If you’re really serious about mastering the art of listening, why not observe other people? One of the best ways to become a better listener is to observe the way people interact with each other, and all the irritating and rude things they do. Create an “annoying habit” checklist, and see if you do any. If you’re brave enough, you can even ask someone you trust about what they like and dislike about the way you interact with others in conversation.

Mastering the Art of Listening Requires Self-Respect

Do you need to listen to everyone deeply all the time? No. That’s not realistic and it can be quite exhausting. It’s perfectly okay to pick and choose who you decide to listen to. Again this requires listening deeply to yourself and your own needs. Are you tired? Is the other person overstepping your boundaries? Do you have something else to do? Feel free to draw a line.

Listening requires self-respect , both toward yourself and other people. You don’t need to be a doormat, a martyr, or a therapist to everyone. But do understand the difference that the power of listening has: it makes you feel more connected to others and life.

So approach this skill with healthy self-respect: you deserve to feel close to others, but also to honor your own needs.

Listening is a skill that is transferable to all aspects of life.

As Diogenes Laertius said: “ We have two ears and only one tongue in order that we may hear more and speak less. ” The art of listening is an invaluable life skill. Not only will it help you communicate better with your friends and family, but it will help you succeed in every other area of your life.

If you found this article helpful, please feel free to comment, or share an experience!

More Starting The Journey

About Aletheia

Aletheia is a prolific psychospiritual writer, author, educator, and intuitive guide whose work has touched the lives of millions worldwide. As a survivor of fundamentalist religious abuse, her mission is to help others find love, strength, and inner light in even the darkest places. She is the author of hundreds of popular articles, as well as numerous books and journals on the topics of Self-Love, Spiritual Awakening, and more. [Read More]

Support Our Work

We spend thousands of dollars and hundreds of hours every month writing, editing, and managing this website – you can find out more in our support page . If you have found any comfort, support, or guidance in our work, please consider donating as it would mean the world to us:

Custom Amount:

I'd like to receive your latest weekly newsletter!

One of my failings as a man was my inability to listen. Since becoming single I have worked on improving this skill and this article puts a useful framework on the process. I wish I had learned this sooner but still I am glad I learned it at all. These social skills should be taught in schools.

Is anyone here in a position to recommend Dresses and Chemises? Thanks xx

Thank you for the beautiful insights!

Hello thanks so much for talking about this side of working in digital.

Good post here. One thing I’d like to say is the fact that most professional fields consider the Bachelor Degree just as the entry level standard for an online education. When Associate Certifications are a great way to start out, completing your Bachelors opens many entrance doors to various professions, there are numerous online Bachelor Course Programs available by institutions like The University of Phoenix, Intercontinental University Online and Kaplan. Another issue is that many brick and mortar institutions offer Online versions of their qualifications but generally for a substantially higher fee than the providers that specialize in online qualification programs.

lovely article. one question. how do you respond to cultures where making eye contact is considered disrespectful?

The New York Times

The learning network | are we losing the art of listening.

Are We Losing the Art of Listening?

Questions about issues in the news for students 13 and older.

- See all Student Opinion »

Listening, like other skills, can be developed through practice, or lost if not used regularly. Good listeners focus on what they are hearing. They pause to think about what they’ve heard before responding. They ask questions because they want to know the answers, not just to keep the conversation going. Do you often find yourself in the company of good listeners? Would you describe yourself as a good listener? Why or why not? In the op-ed piece “The Art of Listening,” Henning Mankell writes about what he has learned from living a “straddled existence, with one foot in African sand and the other in European snow”:

The simplest way to explain what I’ve learned from my life in Africa is through a parable about why human beings have two ears but only one tongue. Why is this? Probably so that we have to listen twice as much as we speak. In Africa listening is a guiding principle. It’s a principle that’s been lost in the constant chatter of the Western world, where no one seems to have the time or even the desire to listen to anyone else. From my own experience, I’ve noticed how much faster I have to answer a question during a TV interview than I did 10, maybe even 5, years ago. It’s as if we have completely lost the ability to listen. We talk and talk, and we end up frightened by silence, the refuge of those who are at a loss for an answer. … Many people make the mistake of confusing information with knowledge. They are not the same thing. Knowledge involves the interpretation of information. Knowledge involves listening. So if I am right that we are storytelling creatures, and as long as we permit ourselves to be quiet for a while now and then, the eternal narrative will continue.

Students: Give us your take on these observations about listening. Like Mr. Mankell, do you feel pressure to respond more quickly than you’d like? Do you find silence frustrating? Have you noticed that you have to repeat things in talking to others, or that you easily forget what they tell you? What about the African proverb that says we have one mouth and two ears so that we talk half as much as we listen–is that good advice, wishful thinking or something else?

Students 13 and older are invited to comment below. Please use only your first name. For privacy policy reasons, we will not publish student comments that include a last name.

Comments are no longer being accepted.

Sometimes I can feel pressure but a lot of the time I do not, the times I do are when it is deciding for one thing over the other. Silence has never frustrated me, it more helps then makes me frustrated. I do notice that i repeat myself more then ounce and have to repeat. I think that advice is true but isn’t in place today.

I do not feel pressured to talk more in class. Naturally i find myself answering questions and being the top student in my class. I guess i was just born a genius or something. I believe the way school is run is perfect.

Give us your take on these observations about listening. Like Mr. Mankell, do you feel pressure to respond more quickly than you’d like? Do you find silence frustrating? Have you noticed that you have to repeat things in talking to others, or that you easily forget what they tell you? What about the African proverb that says we have one mouth and two ears so that we talk half as much as we listen–is that good advice, wishful thinking or something else?

Yes I do feel like teachers want you to respond quicker then we’d like to. Some people take a little longer to raise their hand or write down the answer then other people do. Sometimes I do forget what people tell me right after they say it, sometimes it’s because they say things to fast and other times it’s because I wasn’t paying attention.

Don’t find it very pressuring. Silence is frustrating its just to quiet need loud noises. I forget things that everyone tells me I need to pay more attention. Also i don’t agree with this proverb because in size are mouth is slightly bigger than are ears combine well mine is anyway.

I think the observations about listening are accurate. I do feel the pressure to respond more quickly than I’d like because I feel as if the person is waiting too long for an answer. Silence isn’t frustrating to me unless I asked a question to someone and they didn’t respond. I do have to repeat things to others and they sometimes have to repeat things to me because either I forget or I need to hear it one more time to interpret it. I do think that the African proverb is wishful thinking.

I believe that some people have lost the art of listening but other people still have it, I notice when some one takes time to think about what you said while also planning what they will say.

I do not feel pressured to answer more quickly than i’d like. I talk when I have something to say. I only feel pressured if i’m speaking in front of a class or a high ranking person(s).

To Mr. Mankell, Listening to a speaker’s or teacher’s guidance on a subject fills our brain with knowledge. But not all have the potential or focus to sit down and listen to what a wise one has to say.