Loading metrics

Open Access

Learning Forum

Learning Forum articles are commissioned by our educational advisors. The section provides a forum for learning about an important clinical problem that is relevant to a general medical audience.

See all article types »

A 21-Year-Old Pregnant Woman with Hypertension and Proteinuria

- Andrea Luk,

* To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: [email protected]

- Ching Wan Lam,

- Wing Hung Tam,

- Anthony W. I Lo,

- Enders K. W Ng,

- Alice P. S Kong,

- Wing Yee So,

- Chun Chung Chow

- Andrea Luk,

- Ronald C. W Ma,

- Ching Wan Lam,

- Wing Hung Tam,

- Anthony W. I Lo,

- Enders K. W Ng,

- Alice P. S Kong,

- Wing Yee So,

Published: February 24, 2009

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037

- Reader Comments

Citation: Luk A, Ma RCW, Lam CW, Tam WH, Lo AWI, Ng EKW, et al. (2009) A 21-Year-Old Pregnant Woman with Hypertension and Proteinuria. PLoS Med 6(2): e1000037. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037

Copyright: © 2009 Luk et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this article.

Competing interests: RCWM is Section Editor of the Learning Forum. The remaining authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Abbreviations: CT, computer tomography; I, iodine; MIBG, metaiodobenzylguanidine; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SDH, succinate dehydrogenase; SDHD, succinate dehydrogenase subunit D

Provenance: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed

Description of Case

A 21-year-old pregnant woman, gravida 2 para 1, presented with hypertension and proteinuria at 20 weeks of gestation. She had a history of pre-eclampsia in her first pregnancy one year ago. During that pregnancy, at 39 weeks of gestation, she developed high blood pressure, proteinuria, and deranged liver function. She eventually delivered by emergency caesarean section following failed induction of labour. Blood pressure returned to normal post-partum and she received no further medical follow-up. Family history was remarkable for her mother's diagnosis of hypertension in her fourth decade. Her father and five siblings, including a twin sister, were healthy. She did not smoke nor drink any alcohol. She was not taking any regular medications, health products, or herbs.

At 20 weeks of gestation, blood pressure was found to be elevated at 145/100 mmHg during a routine antenatal clinic visit. Aside from a mild headache, she reported no other symptoms. On physical examination, she was tachycardic with heart rate 100 beats per minute. Body mass index was 16.9 kg/m 2 and she had no cushingoid features. Heart sounds were normal, and there were no signs suggestive of congestive heart failure. Radial-femoral pulses were congruent, and there were no audible renal bruits.

Baseline laboratory investigations showed normal renal and liver function with normal serum urate concentration. Random glucose was 3.8 mmol/l. Complete blood count revealed microcytic anaemia with haemoglobin level 8.3 g/dl (normal range 11.5–14.3 g/dl) and a slightly raised platelet count of 446 × 10 9 /l (normal range 140–380 × 10 9 /l). Iron-deficient state was subsequently confirmed. Quantitation of urine protein indicated mild proteinuria with protein:creatinine ratio of 40.6 mg/mmol (normal range <30 mg/mmol in pregnancy).

What Were Our Differential Diagnoses?

An important cause of hypertension that occurs during pregnancy is pre-eclampsia. It is a condition unique to the gravid state and is characterised by the onset of raised blood pressure and proteinuria in late pregnancy, at or after 20 weeks of gestation [ 1 ]. Pre-eclampsia may be associated with hyperuricaemia, deranged liver function, and signs of neurologic irritability such as headaches, hyper-reflexia, and seizures. In our patient, hypertension developed at a relatively early stage of pregnancy than is customarily observed in pre-eclampsia. Although she had proteinuria, it should be remembered that this could also reflect underlying renal damage due to chronic untreated hypertension. Additionally, her electrocardiogram showed left ventricular hypertrophy, which was another indicator of chronicity.

While pre-eclampsia might still be a potential cause of hypertension in our case, the possibility of pre-existing hypertension needed to be considered. Box 1 shows the differential diagnoses of chronic hypertension, including essential hypertension, primary hyperaldosteronism related to Conn's adenoma or bilateral adrenal hyperplasia, Cushing's syndrome, phaeochromocytoma, renal artery stenosis, glomerulopathy, and coarctation of the aorta.

Box 1: Causes of Hypertension in Pregnancy

- Pre-eclampsia

- Essential hypertension

- Renal artery stenosis

- Glomerulopathy

- Renal parenchyma disease

- Primary hyperaldosteronism (Conn's adenoma or bilateral adrenal hyperplasia)

- Cushing's syndrome

- Phaeochromocytoma

- Coarctation of aorta

- Obstructive sleep apnoea

Renal causes of hypertension were excluded based on normal serum creatinine and a bland urinalysis. Serology for anti-nuclear antibodies was negative. Doppler ultrasonography of renal arteries showed normal flow and no evidence of stenosis. Cushing's syndrome was unlikely as she had no clinical features indicative of hypercortisolism, such as moon face, buffalo hump, violaceous striae, thin skin, proximal muscle weakness, or hyperglycaemia. Plasma potassium concentration was normal, although normokalaemia does not rule out primary hyperaldosteronism. Progesterone has anti-mineralocorticoid effects, and increased placental production of progesterone may mask hypokalaemia. Besides, measurements of renin activity and aldosterone concentration are difficult to interpret as the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis is typically stimulated in pregnancy. Phaeochromocytoma is a rare cause of hypertension in pregnancy that, if unrecognised, is associated with significant maternal and foetal morbidity and mortality. The diagnosis can be established by measuring levels of catecholamines (noradrenaline and adrenaline) and/or their metabolites (normetanephrine and metanephrine) in plasma or urine.

What Was the Diagnosis?

Catecholamine levels in 24-hour urine collections were found to be markedly raised. Urinary noradrenaline excretion was markedly elevated at 5,659 nmol, 8,225 nmol, and 9,601 nmol/day in repeated collections at 21 weeks of gestation (normal range 63–416 nmol/day). Urinary adrenaline excretion was normal. Pregnancy may induce mild elevation of catecholamine levels, but the marked elevation of urinary catecholamine observed was diagnostic of phaeochromocytoma. Conditions that are associated with false positive results, such as acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, acute cerebrovascular event, withdrawal from alcohol, withdrawal from clonidine, and cocaine abuse, were not present in our patient.

The working diagnosis was therefore phaeochromocytoma complicating pregnancy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of neck to pelvis, without gadolinium enhancement, was performed at 24 weeks of gestation. It showed a 4.2 cm solid lesion in the mid-abdominal aorto-caval region, while both adrenals were unremarkable. There were no ectopic lesions seen in the rest of the examined areas. Based on existing investigation findings, it was concluded that she had extra-adrenal paraganglioma resulting in hypertension.

What Was the Next Step in Management?

At 22 weeks of gestation, the patient was started on phenoxybenzamine titrated to a dose of 30 mg in the morning and 10 mg in the evening. Propranolol was added several days after the commencement of phenoxybenzamine. Apart from mild postural dizziness, the medical therapy was well tolerated during the remainder of the pregnancy. In the third trimester, systolic and diastolic blood pressures were maintained to below 90 mmHg and 60 mmHg, respectively. During this period, she developed mild elevation of alkaline phosphatase ranging from 91 to 188 IU/l (reference 35–85 IU/l). However, liver transaminases were normal and the patient had no seizures. Repeated urinalysis showed resolution of proteinuria. At 38 weeks of gestation, the patient proceeded to elective caesarean section because of previous caesarean section, and a live female baby weighing 3.14 kg was delivered. The delivery was uncomplicated and blood pressure remained stable.

Following the delivery, computer tomography (CT) scan of neck, abdomen, and pelvis was performed as part of pre-operative planning to better delineate the relationship of the tumour to neighbouring structures. In addition to the previously identified extra-adrenal paraganglioma in the abdomen ( Figure 1 ), the CT revealed a 9 mm hypervascular nodule at the left carotid bifurcation, suggestive of a carotid body tumour ( Figure 2 ). The patient subsequently underwent an iodine (I) 131 metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scan, which demonstrated marked MIBG-avidity of the paraganglioma in the mid-abdomen. The reported left carotid body tumour, however, did not demonstrate any significant uptake. This could indicate either that the MIBG scan had poor sensitivity in detecting a small tumour, or that the carotid body tumour was not functional.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037.g001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037.g002

In June 2008, four months after the delivery, the patient had a laparotomy with removal of the abdominal paraganglioma. The operation was uncomplicated. There was no wide fluctuation of blood pressures intra- and postoperatively. Phenoxybenzamine and propranolol were stopped after the operation. Histology of the excised tumour was consistent with paraganglioma with cells staining positive for chromogranin ( Figures 3 and 4 ) and synaptophysin. Adrenal tissues were notably absent.

The tumour is a well-circumscribed fleshy yellowish mass with maximal dimension of 5.5 cm.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037.g003

The tumour cells are polygonal with bland nuclei. The cells are arranged in nests and are immunoreactive to chromogranin (shown here) and synaptophysin.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037.g004

The patient was counselled for genetic testing for hereditary phaeochromocytoma/paraganglioma. She was found to be heterozygous for c.449_453dup mutation of the succinate dehydrogenase subunit D (SDHD) gene ( Figure 5 ). This mutation is a novel frameshift mutation, and leads to SDHD deficiency (GenBank accession number: 1162563). At the latest clinic visit in August 2008, she was asymptomatic and normotensive. Measurements of catecholamine in 24-hour urine collections had normalised. Resection of the left carotid body tumour was planned for a later date. She was to be followed up indefinitely to monitor for recurrences. She was also advised to contact family members for genetic testing. Our patient gave written consent for this case to be published.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037.g005

Phaeochromocytoma in Pregnancy

Hypertension during pregnancy is a frequently encountered obstetric complication that occurs in 6%–8% of pregnancies [ 2 ]. Phaeochromocytoma presenting for the first time in pregnancy is rare, and only several hundred cases have been reported in the English literature. In a recent review of 41 cases that presented during 1988 to 1997, maternal mortality was 4% while the rate of foetal loss was 11% [ 3 ]. Antenatal diagnosis was associated with substantial reduction in maternal mortality but had little impact on foetal mortality. Further, chronic hypertension, regardless of aetiology, increases the risk of pre-eclampsia by 10-fold [ 1 ].

Classically, patients with phaeochromocytoma present with spells of palpitation, headaches, and diaphoresis [ 4 ]. Hypertension may be sustained or sporadic, and is associated with orthostatic blood pressure drop because of hypovolaemia and impaired vasoconstricting response to posture change. During pregnancy, catecholamine surge may be triggered by pressure from the enlarging uterus and foetal movements. In the majority of cases, catecholamine-secreting tumours develop in the adrenal medulla and are termed phaeochromocytoma. Ten percent of tumours arise from extra-adrenal chromaffin tissues located in the abdomen, pelvis, or thorax to form paraganglioma that may or may not be biochemically active. The malignant potential of phaeochromocytoma or paraganglioma cannot be determined from histology and is inferred by finding tumours in areas of the body not known to contain chromaffin tissues. The risk of malignancy is higher in extra-adrenal tumours and in tumours that secrete dopamine.

Making the Correct Diagnosis

The diagnosis of phaeochromocytoma requires a combination of biochemical and anatomical confirmation. Catecholamines and their metabolites, metanephrines, can be easily measured in urine or plasma samples. Day collection of urinary fractionated metanephrine is considered the most sensitive in detecting phaeochromocytoma [ 5 ]. In contrast to sporadic release of catecholamine, secretion of metanephrine is continuous and is less subjective to momentary stress. Localisation of tumour can be accomplished by either CT or MRI of the abdomen [ 6 ]. Sensitivities are comparable, although MRI is preferable in pregnancy because of minimal radiation exposure. Once a tumour is identified, nuclear medicine imaging should be performed to determine its activity, as well as to search for extra-adrenal diseases. I 131 or I 123 MIBG scan is the imaging modality of choice. Metaiodobenzylguanidine structurally resembles noradrenaline and is concentrated in chromaffin cells of phaeochromocytoma or paraganglioma that express noradrenaline transporters. Radionucleotide imaging is contraindicated in pregnancy and should be deferred until after the delivery.

Treatment Approach

Upon confirming the diagnosis, medical therapy should be initiated promptly to block the cardiovascular effects of catecholamine release. Phenoxybenzamine is a long-acting non-selective alpha-blocker commonly used in phaeochromocytoma to control blood pressure and prevent cardiovascular complications [ 7 ]. The main side-effects of phenoxybenzamine are postural hypotension and reflex tachycardia. The latter can be circumvented by the addition of a beta-blocker. It is important to note that beta-blockers should not be used in isolation, since blockade of ß2-adrenoceptors, which have a vasodilatory effect, can cause unopposed vasoconstriction by a1-adrenoceptor stimulation and precipitate severe hypertension. There is little data on the safety of use of phenoxybenzamine in pregnancy, although its use is deemed necessary and probably life-saving in this precarious situation.

The definitive treatment of phaeochromocytoma or paraganglioma is surgical excision. The timing of surgery is critical, and the decision must take into consideration risks to the foetus, technical difficulty regarding access to the tumour in the presence of a gravid uterus, and whether the patient's symptoms can be satisfactorily controlled with medical therapy [ 8 , 9 ]. It has been suggested that surgical resection is reasonable if the diagnosis is confirmed and the tumour identified before 24 weeks of gestation. Otherwise, it may be preferable to allow the pregnancy to progress under adequate alpha- and beta-blockade until foetal maturity is reached. Unprepared delivery is associated with a high risk of phaeochromocytoma crisis, characterised by labile blood pressure, tachycardia, fever, myocardial ischaemia, congestive heart failure, and intracerebral bleeding.

Patients with phaeochromocytoma or paraganglioma should be followed up for life. The rate of recurrence is estimated to be 2%–4% at five years [ 10 ]. Assessment for recurrent disease can be accomplished by periodic blood pressure monitoring and 24-hour urine catecholamine and/or metanephrine measurements.

Genetics of Phaeochromocytoma

Approximately one quarter of patients presenting with phaeochromocytoma may carry germline mutations, even in the absence of apparent family history [ 11 ]. The common syndromes of hereditary phaeochromocytoma/paraganglioma are listed in Box 2 . These include Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2, neurofibromatosis type 1, and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) gene mutations. Our patient has a novel frameshift mutation in the SDHD gene located at Chromosome 11q. SDH is a mitochondrial enzyme that is involved in oxidative phosphorylation. Characteristically, SDHD mutation is associated with head or neck non-functional paraganglioma, and infrequently, sympathetic paraganglioma or phaeochromocytoma [ 12 ]. Tumours associated with SDHD mutation are rarely malignant, in contrast to those arisen from mutation of the SDHB gene. Like all other syndromes of hereditary phaeochromocytoma, SDHD mutation is transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion. However, not all carriers of the SDHD mutation develop tumours, and inheritance is further complicated by maternal imprinting in gene expression. While it may not be practical to screen for genetic alterations in all cases of phaeochromocytoma, most authorities advocate genetic screening for patients with positive family history, young age of tumour onset, co-existence with other neoplasms, bilateral phaeochromocytoma, and extra-adrenal paraganglioma. The confirmation of genetic mutation should prompt evaluation of other family members.

Box 2: Hereditary Phaeochromocytoma/Paraganglioma Syndromes

- Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome

- Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A and type 2B

- Neurofibromatosis type 1

- Mutation of SDHB , SDHC , SDHD

- Ataxia-telangiectasia

- Tuberous sclerosis

- Sturge-Weber syndrome

Key Learning Points

- Hypertension complicating pregnancy is a commonly encountered medical condition.

- Pre-existing chronic hypertension must be considered in patients with hypertension presenting in pregnancy, particularly if elevation of blood pressure is detected early during pregnancy or if persists post-partum.

- Secondary causes of chronic hypertension include renal artery stenosis, renal parenchyma disease, primary hyperaldosteronism, phaeochromocytoma, Cushing's syndrome, coarctation of the aorta, and obstructive sleep apnoea.

- Phaeochromocytoma presenting during pregnancy is rare but carries high rates of maternal and foetal morbidity and mortality if unrecognised.

- Successful outcomes depend on early disease identification, prompt initiation of alpha- and beta-blockers, carefully planned delivery, and timely resection of the tumour.

Phaeochromocytoma complicating pregnancy is uncommon. Nonetheless, in view of the potential for catastrophic consequences if unrecognised, a high index of suspicion and careful evaluation for secondary causes of hypertension is of utmost importance. Blood pressure should be monitored in the post-partum period and persistence of hypertension must be thoroughly investigated.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in the management of the patient or writing of the article. AL and RCWM wrote the article, with contributions from all the authors.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Mini Review

- Mini review series: Current topic in Hypertension

- Published: 02 June 2023

Preeclampsia up to date—What’s going on?

- Kanako Bokuda 1 &

- Atsuhiro Ichihara 1

Hypertension Research volume 46 , pages 1900–1907 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

6630 Accesses

4 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Preeclampsia is a hypertensive disorder in pregnancy characterized by placental malperfusion and subsequent multi-organ injury. It accounts for approximately 14% of maternal deaths and 10–25% of perinatal deaths globally. In addition, preeclampsia has been attracting attentions for its association with risks for developing chronic diseases in later life for both mother and child. This mini-review discusses on latest knowledge on prediction, prevention, management, and long-term outcomes of preeclampsia and also touches on association between COVID-19 and preeclampsia.

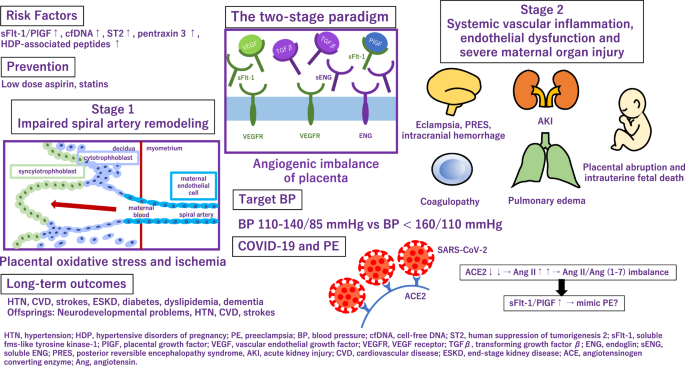

HTN hypertension, HDP hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, PE preeclampsia, BP blood pressure, cfDNA cell-free DNA, ST2 human suppression of tumorigenesis 2, sFlt-1 soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1, PIGF placental growth factor, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGFR VEGF receptor, TGF β transforming growth factor β , ENG endoglin, sENG soluble ENG, PRES posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, AKI acute kidney injury, CVD cardiovascular disease, ESKD end-stage kidney disease, ACE angiotensinogen converting enzyme, Ang angiotensin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Unravelling the potential of angiogenic factors for the early prediction of preeclampsia

Juilee S. Deshpande, Deepali P. Sundrani, … Sadhana R. Joshi

Circulating EGFL7 distinguishes between IUGR and PE: an observational case–control study

Micol Massimiani, Silvia Salvi, … Luisa Campagnolo

Pre-eclampsia

Evdokia Dimitriadis, Daniel L. Rolnik, … Ellen Menkhorst

Introduction

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) affect approximately 10% of all pregnancies globally. HDP, particularly preeclampsia (PE), accounts for as high as 14% of maternal mortality and results in 10–25% of perinatal deaths. The 2019 Maternal Mortality update from the WHO report noted the major contribution of PE and eclampsia to worldwide maternal deaths. Since once it develops, termination is the only given way to ameliorate the symptoms of PE, trials and cohort studies regarding PE, give insight into the development of diagnostic and prognostic tools and preventive care.

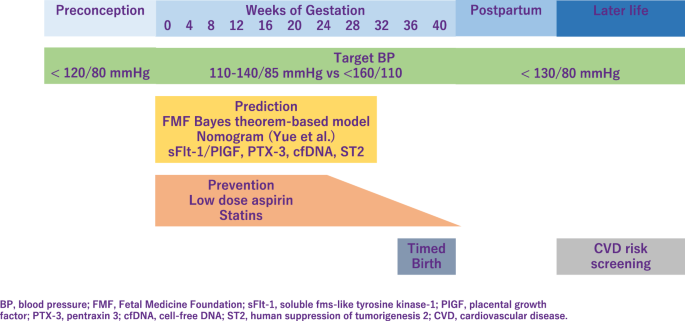

It is important to provide early screening and identify pregnant women at high risk who might benefit from prophylactic agents [ 1 ]. The Fetal Medicine Foundation proposed a Bayes theorem-based model to predict preterm PE using a combination of maternal characteristics, medical history, mean arterial pressure, uterine artery pulsatility index, and serum placental growth factor (PlGF). This model can predict ~90% of early PE cases, with delivery at <32 weeks of gestation and 75% of preterm PE cases, with delivery at <37 weeks of gestation [ 2 , 3 ]. Recently, Yue et al. have developed and validated a new nomogram for the early prediction of PE in pregnant Chinese women [ 4 ]. This nomogram included body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (BP), uterine artery ultrasound parameters, and serological indicators and can be easily utilized to facilitate the individualized prediction of PE.

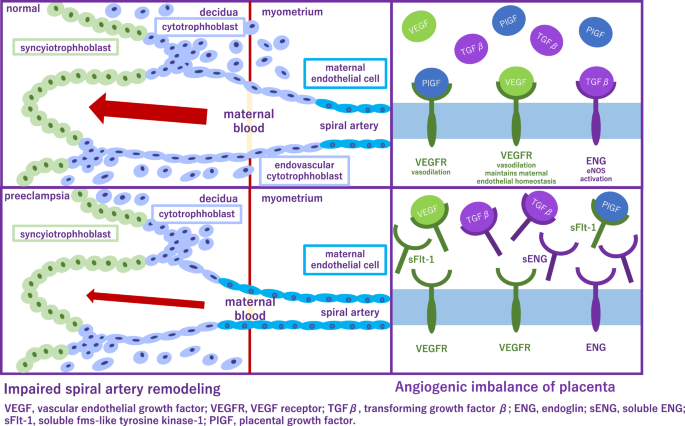

Application of angiogenic and antiangiogenic biomarkers into clinical practice will help reduce the considerable burden of morbidity and mortality associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes as a consequence of PE. PE is associated with alteration of angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors such as soluble fms-like tyrosine 1 (sFlt-1), soluble endoglin (sENG) and PlGF [ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ] (Fig. 1 ). Quantification of the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio, has been shown to be a useful biomarker test for aiding the diagnosis and short-term prediction of PE [ 10 ]. PRediction of short-term Outcomes in preGNant wOmen with Suspected PE Study (PROGNOSIS) proposed and validated sFlt-1/PIGF ratio cutoff of 38 to predict the development of PE in women with clinical suspicion [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. Furthermore, the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio test is likely to lessen the avoidable hospitalization of women at low risk of developing PE in the short term while identifying high-risk individuals requiring appropriate management [ 14 ].

Alteration of angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia

Besides sFlt-1 and PlGF, several biomarkers have been reported as candidate markers for predicting the development of PE. The first trimester pregnancy-associated plasma protein A can predict PE and superimposed PE in the third trimester [ 15 ]. Plasma cell-free DNA and human suppression of tumorigenesis served as diagnostic biomarkers for gestational hypertension (GH) and PE [ 16 ]. Pentraxin 3, an acute-phase protein which is produced and released in response to inflammatory stimuli, has been proposed as a novel biomarker predicting placental failure [ 17 ] and was also associated with PE [ 18 ]. Using an effective peptidomic analysis, Wakabayashi et al. identified seven circulating HDP-associated peptides (P-2081, P-2091, P-2127, P-2209, P-2378, P-2858, and P-3156) and proposed them as biomarkers for the diagnosis of HDP [ 19 ]. Interestingly, they have also investigated that these peptides are possible biomarkers for discriminating cardiovascular risk even in general population [ 20 ].

Low-dose aspirin is highly promising for the prevention of PE and is extensively studied. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP), National Institute for Health, and Care Excellence, Japan Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (JSSHP) recommend initiation of low-dose aspirin in women with high risk factor to reduce the risk of PE [ 21 , 22 , 23 ]. A systematic review established benefits of low-dose aspirin taken during pregnancy [ 24 ]. Aspirin use was significantly associated with lower risk of PE, perinatal mortality, preterm birth, and intrauterine growth restriction. According to the guideline proposed by the ACOG in 2018 [ 23 ], chronic hypertension (CH) is one of the risk factors for the development of PE, and aspirin is recommended for this group of patients. However, incidence of superimposed PE was not significantly different in the pre-ACOG group and post ACOG group, indicating that aspirin did not reduce the incidence of superimposed PE in patients with CH. Aspirin decreases the risk of PE, but its effectiveness in women with CH remains controversial [ 25 ]. Aspirin is preferably started before 16 weeks of gestation and continued until delivery. However, initiation of aspirin may complicate peripartum bleeding, which could be mitigated by discontinuing aspirin earlier. Recent multicenter, randomized trial showed that aspirin discontinuation at 24 to 28 weeks of gestation is noninferior to aspirin continuation for preventing preterm PE in individuals at high risk of PE and a normal sFlt-1/PlGF ratio between 24 weeks 0 days and 27 weeks 6 days of gestation.

The properties and mechanisms of action of statins make them candidates for the prevention of PE. In a meta-analysis, which included 10 studies describing 1391 women with uteroplacental insufficiency disorders: 703 treated with pravastatin and 688 not treated with statins, pravastatin prolonged pregnancy duration and improved associated obstetrical outcomes in pregnancies complicated with uteroplacental insufficiency disorders [ 26 ]. In contrast, 1120 women with singleton pregnancies at high risk of term PE were randomly assigned to receive pravastatin at a dose of 20 mg/d or placebo from 35 to 37 weeks of gestation until delivery or 41 weeks. Pravastatin in women at high risk of term PE did not reduce the incidence of delivery with PE [ 27 ].

In 2017, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association hypertension (ACC/AHA) treatment guidelines identified hypertension as BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg. However, the reference BP for hypertension during pregnancy as specified in international guidelines [eg. ISSHP [ 22 ], ACOG [ 28 , 29 ]], is ≥140/90 mmHg (Fig. 2 ). In Japan, guidelines of Japanese Society of Hypertension and JSSHP, both define hypertension as BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg whether the patient is pregnant or not [ 21 , 30 , 31 ]. Respecting BP control, from a preventive point of view, understanding the importance of preconception BP is of particular interest. It is relatively easy to intervene before pregnancy, and furthermore, this may have a greater impact on gestational outcome. In previous study, preconception BP and its change into early pregnancy was evaluated as risk markers for the development of HDP. Among 586 women with a pregnancy >20 weeks’ gestation, preconception BP levels were higher for preterm PE, term PE, and GH as compared with no HDP [ 32 ]. In large cohort study, which examined whether high BP in the preconception period was associated with GH and PE, when participants with normal BP were used as the reference, the adjusted ORs for GH were 1.48, 1.70, and 1.29, and for PE, the adjusted ORs were 1.55, 1.95, and 1.99 for the participants with prehypertension (SBP 120–139 mmHg or DBP 80–89 mmHg), stage 1 hypertension (SBP 140–159 mmHg or DBP 90–99 mmHg), and stage 2 hypertension (SBP ≥ 160 mmHg or DBP ≥ 100 mmHg), respectively [ 33 ]. These results support an association between hypertension and also prehypertension prior to pregnancy and an increased risk of GH and PE.

Management of preeclampsia

Target BP during pregnancy differs between guidelines. ISSHP recommends that BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg should be treated with a goal BP 110–140/85 mmHg, while ACOG recommends antihypertensive medications when BP ≥ 160/110 mmHg with goal BP below this threshold. JSSHP recommends to initiate antihypertensive medications when BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg for CH and BP ≥ 160/90 mmHg (depending on the situation, ≥140/90 mmHg) for other categories of HDP and to set target BP depending on the conditions of each case [ 21 ]. Studies reported that women in a low-risk cohort with stage 1 hypertension defined as 130–139 mmHg/80–89 mmHg, according to the ACC/AHA, are more likely to develop PE than women with normotensive in the early gestation. Based on the randomized controlled trial in China, the authors investigated whether PE was more likely to occur in stage 1 hypertensive women compared to the normotensive pregnant women between gestational age 12–20 weeks, in a high-risk cohort [ 34 ]. This subanalysis have revealed that stage 1 hypertension might be an additional risk factor for PE in high-risk pregnant women, and aspirin intervention might be useful in preventing PE. A meta-analysis established that the category of elevated BP had a risk ratio of 2.0 (95% prediction interval, 0.8–4.8), the stage 1 hypertension category had a risk ratio of 3.0 (95% prediction interval, 1.1–8.5), and the stage 2 hypertension category had a risk ratio of 7.9 (95% prediction interval, 1.8–35.1) [ 35 ]. However, none of the systolic BP measurements of <120 mmHg, <130 mmHg, or <140 mmHg were useful to rule out the development of PE. Another meta-analysis investigated that BP ≥ 120/80 mmHg, particularly ≥130/80 mmHg, at <20 weeks of gestation, is associated with increased maternal and perinatal risks and the authors proposed new BP categories in pregnancy as normal (<120/80), high normal (120–129/ < 80), and elevated (130–139/80–89) [ 36 ]. One retrospective study has shown that systolic BP < 130 mmHg within 14 weeks of gestation reduced the risk of developing early-onset superimposed PE in women with CH [ 37 ]. The benefits and safety of the treatment of mild hypertension (BP, <160/100 mm Hg) during pregnancy are still uncertain. Data are needed on whether a strategy of targeting a BP of less than 140/90 mmHg reduces the incidence of adverse pregnancy outcomes without compromising fetal growth.

Nifedipine, labetalol, and hydralazine alone or in combination are presently recommended by ACOG for the acute lowering of severe BP (≥160 mm Hg systolic and/or ≥110 mm Hg diastolic) in pregnancy [ 38 ]. A randomized controlled trial demonstrated that oral antihypertensives, methyldopa, nifedipine, and labetalol, all reduced BP in severe range to the reference range in most women [ 39 ]. As single drugs, nifedipine retard use resulted in a greater frequency of primary outcome [BP control (defined as 120–150 mm Hg SBP and 70–100 mm Hg DBP) within 6 h with no adverse outcomes.] attainment. A meta-analysis demonstrated that all commonly prescribed oral antihypertensives (labetalol, other β -blockers, methyldopa, calcium channel blockers, and mixed/multi-drug therapy) versus placebo/no therapy reduced the risk of severe hypertension by 30 to 70% in nonsevere pregnancy hypertension [ 40 ]. In addition, labetalol decreased proteinuria/PE and fetal/newborn death compared with placebo/no therapy, and proteinuria/PE compared with methyldopa and calcium channel blockers.

Currently, magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) is the primary treatment option and it is administered prophylactically to women with severe PE who are at risk of developing eclampsia. While MgSO4 is effective in preventing seizures, it is not as effective in reducing hypertension or other maternal organ injuries such as proteinuria in PE patients. Therefore, finding a therapeutic agent that improves multiple PE symptoms is urgent. In rat model, cyclosporin A (CsA) effectively attenuated PE manifestation and eclampsia-like seizure severity. In addition, CsA treatment significantly reduced the inflammatory cytokine levels and improved pregnancy outcomes following eclampsia-like seizures. The decreased inflammatory cytokines in PE are coincident with attenuated PE manifestation, suggesting that CsA treatment might decrease the PE severity through decreasing systemic inflammation [ 41 ]. Crocin, a hydrophilic carotenoid pigment, is a major compound with pharmacological activities found in Crocus sativus L. (saffron). Crocin alleviated inflammatory and oxidative stress in placental tissues, thereby protecting against GH, one of the major phenotypes of PE, and activated the Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway [ 42 ].

In women with a PE at term, immediate delivery reduces the risk of adverse maternal outcomes or progression to severe disease without affecting neonatal outcomes. However, in women with a PE diagnosed before term, benefits of delivery for the mother need to be weighed against the adverse consequences of iatrogenic preterm birth for the infant. In women with late preterm PE, the optimal time for termination is unclear because limitation of maternal disease progression needs to be balanced against infant complications. A randomized controlled study has shown that incidence of maternal death and severe hypertension was significantly lower in the planned delivery group compared with the expectant management group. However, planned delivery led to more neonatal unit admissions for the infant, principally for a listed indication of prematurity and without an excess of respiratory or other morbidity, intensity of care, or length of stay. This trade-off should be circumspectly discussed with women with late preterm PE to decide the optimal timing of delivery [ 43 ].

Long-term outcomes

Women with history of PE have increased cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. Pregnancy has been labeled as a stress test which reveals women with cardiovascular dysfunction or poor reserve [ 44 , 45 ]. A rise of 10-year maternal CVD risk is associated with PE, while those with sustained hypertension after delivery have a two-fold increase in the risk of developing CVD in the next 10–30 years. Adverse pregnancy outcomes (APO) including PE, occur in 10 to 20% of all pregnancies and are also associated with a 1.8- to 4.0-fold risk of future CVD [ 46 , 47 ]. Women with a history of HDP are reported to have stiffer arteries and have a 2–5 times higher risk of hypertension in later life, compared to normotensive gestations [ 48 , 49 ]. Association between HDP and later hypertension was reported to be stronger in younger women and in obese women in the 30–70 age group [ 50 ]. Additionally, PE is considered a risk factor for chronic diseases such as hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia, each of which independently increases the incidence of cardiovascular morbidity [ 45 ]. PE was included as a “risk-enhancer” in the updated 2018 cholesterol guideline [ 51 ] and in the 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease [ 52 ]. The ACOG recommends that women with APO undergo cardiovascular risk screening within 3 months postpartum [ 53 ].

Data from the Stroke Prevention in Young Women Study showed that women with a history of PE are 60% more likely to suffer from ischemic stroke after multivariable adjustment [ 54 ]. Studies from the World Health Organization also showed an increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke [ 55 ] and venous thromboembolism [ 56 ] in women with history of hypertension in pregnancy. Prior PE is also associated with an increased risk for the development of end-stage kidney disease. A meta-analysis of 2,309,946 women(among whom 103,308 women with PE) demonstrated that history of PE also increases the risk of vascular dementia [ 57 ].

The mechanisms responsible for these associations remain unclear. One possible mechanism maybe the presence of remaining angiotensin II type 1 receptor agonistic autoantibody (AT1-AA) postpartum. AT1-AAs are elevated in women with PE. AT1-AA binds to angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) and increases AT1R activity, intracellular calcium levels, and activation of intracellular mitogen activated protein kinase/extracellular signal regulated kinases (MAPK/ERK) pathways. Previous study reported that −18% of postpartum PE women have elevated circulating AT1-AAs 1 year after delivery [ 58 ]. These women with elevated AT1-AAs had increased sFlt-1, decreased free VEGF, and higher insulin resistance compared with autoantibody negative women and these correlations may suggest a mechanism by which women with PE have increased risks of severe complications later in life. JSSHP recommends to explain to women with a history of HDP that they have a higher risk of developing subsequent lifestyle diseases and cerebrovascular/cardiovascular diseases and that regular follow-up and lifestyle intervention guidance can reduce the incidence [ 21 ].

Preterm delivery is associated with long-term neurodevelopmental problems in the offspring. Zwertbroek et al. found that early delivery in women with late preterm HDP is associated with poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes in their children at 2 years of age [ 59 ]. These findings indicate an increased risk of developmental delay after early delivery compared to expectant monitoring. The infant from a PE pregnancy also appears at increased risk for CVD [ 60 ]. Infants of mothers with PE have higher BP during young adulthood and an increased risk for stroke in later life [ 61 ]. Other differences have also been shown, including increased BMI [ 62 ] and hormonal changes.

Pregnancy could potentially affect the susceptibility to and the severity of COVID-19 and pregnant women are at an increased risk of mortality and morbidity due to COVID-19. In addition, what we need to be aware of is that although pregnant women are less likely to complain of the symptoms of COVID-19, they are more than twice as likely to require critical care or mechanical ventilation than nonpregnant women [ 63 ]. Kalafat et al. have proposed that the mini-model which includes the maternal age, BMI, and pregnancy trimester can be used to estimate the risk of developing critical COVID-19 before disease onset. The addition of inflammatory markers to maternal BMI at the time of diagnosis can accurately predict critical COVID-19, PE, and the progression time from diagnosis to clinical deterioration [ 64 ].

Although few cases of intrauterine transmission of SARS-CoV-2 have been documented, it appears to be rare [ 65 ]. It is possibly related to low levels of SARS-CoV-2 viremia and the decreased coexpression of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) 2 and transmembrane serine protease 2 which is needed for SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells in the placenta. However, evidence is accumulating that SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with a number of adverse pregnancy outcomes including PE, preterm birth, and stillbirth [ 66 ]. This tendency is reported to be observed especially among pregnant women with severe COVID-19 disease, but one large, longitudinal, prospective, observational study assessing the effect of COVID-19 during pregnancy on mothers and neonates have shown that COVID-19 severity does not seem to be a factor in this association [ 67 ]. Additionally, besides the direct impact of COVID-19 on pregnancy outcomes, there is evidence that the pandemic and its effects on healthcare systems have had detrimental effects on pregnancy outcomes even among pregnant women not infected with SARS-CoV-2 [ 68 ].

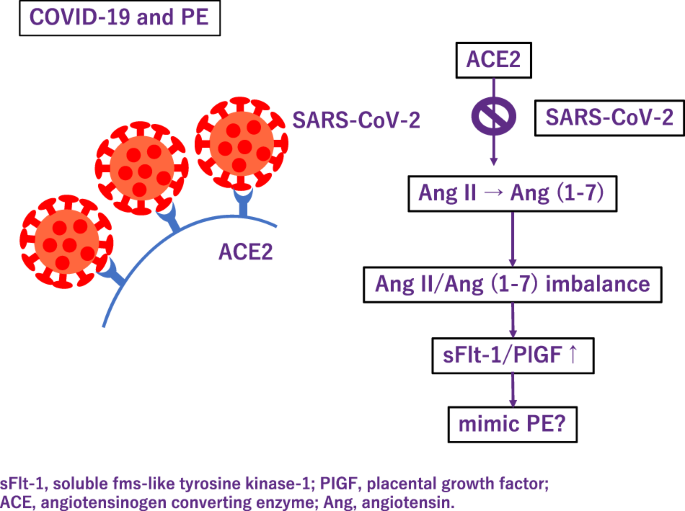

Also, some severe cases of COVID-19, patients present with PE-like symptoms (Fig. 3 ). PE mimicry by COVID-19 was confirmed following the alleviation of PE symptoms without delivery of placenta [ 69 ]. In COVID-19, ACE 2 function decreases and subsequently Ang (angiotensin) II activity increases [ 70 ]. Although COVID-19 shows an increase in the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio due to pathologic Ang II/Ang (1–7) imbalance like PE [ 71 ], sFlt1/PlGF ratio did not correlate with the severity [ 72 ]. Most experts believe that SARS-Cov-2 is likely to become endemic, the continued collection of data on the effects of COVID-19 during pregnancy are needed.

Association between COVID-19 and preeclampsia

Future perspectives

Pregnancy period is said to be a window where we can catch a glimpse of woman’s future. Though the symptoms of PE manifest typically in late pregnancy, fundamental alteration that underlies exists earlier in pregnancy or even preconceptionally and lasts throughout life. Earlier prediction, prevention and longer follow up is necessary for comprehensive management of PE. There is much to be done to decrease PE related maternal and fetal deaths and also to reduce maternal risks for chronic diseases in later life.

Rolnik DL, Wright D, Poon LC, O’Gorman N, Syngelaki A, de Paco Matallana C, et al. Aspirin versus placebo in pregnancies at high risk for preterm preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:613–22.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Chaemsaithong P, Pooh RK, Zheng M, Ma R, Chaiyasit N, Tokunaka M, et al. Prospective evaluation of screening performance of first-trimester prediction models for preterm preeclampsia in an Asian population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:650.e1–650.e16.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

O’Gorman N, Wright D, Syngelaki A, Akolekar R, Wright A, Poon LC, et al. Competing risks model in screening for preeclampsia by maternal factors and biomarkers at 11–13 weeks gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:103.e1–103.e12.

Yue C, Gao J, Zhang C, Ni Y, Ying C. Development and validation of a nomogram for the early prediction of preeclampsia in pregnant Chinese women. Hypertens Res. 2021;44:417–25.

Duhig KE, Myers J, Seed PT, Sparkes J, Lowe J, Hunter RM, et al. Placental growth factor testing to assess women with suspected pre-eclampsia: a multicentre, pragmatic, stepped-wedge cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;393:1807–18.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Verlohren S, Herraiz I, Lapaire O, Schlembach D, Moertl M, Zeisler H, et al. The sFlt-1/PlGF ratio in different types of hypertensive pregnancy disorders and its prognostic potential in preeclamptic patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:58.e1–8.

Verlohren S, Perschel FH, Thilaganathan B, Dröge LA, Henrich W, Busjahn A, et al. Angiogenic markers and cardiovascular indices in the prediction of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Hypertension. 2017;69:1192–7.

Levine RJ, Lam C, Qian C, Yu KF, Maynard SE, Sachs BP, et al. Soluble endoglin and other circulating antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:992–1005.

Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, Lim K-H, England LJ, Yu KF, et al. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:672–83.

Cerdeira AS, O’Sullivan J, Ohuma EO, Harrington D, Szafranski P, Black R, et al. Randomized interventional study on prediction of preeclampsia/eclampsia in women with suspected preeclampsia: INSPIRE. Hypertension. 2019;74:983–90.

Zeisler H, Llurba E, Chantraine FJ, Vatish M, Staff AC, Sennström M, et al. Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 to placental growth factor ratio: ruling out pre-eclampsia for up to 4 weeks and value of retesting. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol J Int Soc Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019;53:367–75.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Hund M, Allegranza D, Schoedl M, Dilba P, Verhagen-Kamerbeek W, Stepan H. Multicenter prospective clinical study to evaluate the prediction of short-term outcome in pregnant women with suspected preeclampsia (PROGNOSIS): study protocol. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:324.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Zeisler H, Llurba E, Chantraine F, Vatish M, Staff AC, Sennström M, et al. Predictive value of the sFlt-1:PlGF ratio in women with suspected preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:13–22.

Ohkuchi A, Masuyama H, Yamamoto T, Kikuchi T, Taguchi N, Wolf C, et al. Economic evaluation of the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio for the short-term prediction of preeclampsia in a Japanese cohort of the PROGNOSIS Asia study. Hypertens Res J Jpn Soc Hypertens. 2021;44:822–9.

Chen Y, Wang X, Hu W, Chen Y, Ning W, Lu S, et al. A risk model that combines MAP, PlGF, and PAPP-A in the first trimester of pregnancy to predict hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. J Hum Hypertens. 2022;36:184–91.

Liu L, Li H, Wang N, Song X, Zhao K, Zhang C. Assessment of plasma cell-free DNA and ST2 as parameters in gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Hypertens Res. 2021;44:996–1001.

Zhou P, Luo X, Qi H-B, Zong W-J, Zhang H, Liu D-D, et al. The expression of pentraxin 3 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha is increased in preeclamptic placental tissue and maternal serum. Inflamm Res. 2012;61:1005–12.

Colmenares-Mejía CC, Quintero-Lesmes DC, Bautista-Niño PK, Guio Mahecha E, Beltrán Avendaño M, Díaz Martínez LA, et al. Pentraxin-3 is a candidate biomarker on the spectrum of severity from pre-eclampsia to HELLP syndrome: GenPE study. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:884–91.

Araki Y, Yanagida M. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: strategy to develop clinical peptide biomarkers for more accurate evaluation of the pathophysiological status of this syndrome. Adv Clin Chem. 2020;94:1–30.

Wakabayashi I, Yanagida M, Araki Y. Associations of cardiovascular risk with circulating peptides related to hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Hypertens Res. 2021;44:1641–51.

Takagi K, Nakamoto O, Watanabe K, Tanaka K, Matsubara K, Kawabata I, et al. A review of best practice guide 2021 for diagnosis and management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) - misc. - researchmap. Hypertens Res Pregnancy. 2022;10:57–73.

Article Google Scholar

Brown MA, Magee LA, Kenny LC, Karumanchi SA, McCarthy FP, Saito S, et al. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: ISSHP classification, diagnosis, and management recommendations for international practice. Hypertension. 2018;72:24–43.

Espinoza J, Vidaeff A, Pettker CM, Simhan H. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 743: low-dose aspirin use during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e44–e52.

Henderson JT, Vesco KK, Senger CA, Thomas RG, Redmond N. Aspirin use to prevent preeclampsia and related morbidity and mortality: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;326:1192–206.

Magee LA, Khalil A, Kametas N, von Dadelszen P. Toward personalized management of chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226:S1196–210.

Hirsch A, Rotem R, Ternovsky N, Hirsh Raccah B. Pravastatin and placental insufficiency associated disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharm. 2022;13:1021548.

Döbert M, Varouxaki AN, Mu AC, Syngelaki A, Ciobanu A, Akolekar R, et al. Pravastatin versus placebo in pregnancies at high risk of term preeclampsia. Circulation. 2021;144:670–9.

Espinoza J, Vidaeff A, Pettker CM, Simhan H. Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 222. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e237–e260.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 203: chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e26–e50.

Metoki H, Iwama N, Hamada H, Satoh M, Murakami T, Ishikuro M, et al. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: definition, management, and out-of-office blood pressure measurement. Hypertens Res. 2022;45:1298–309.

Umemura S, Arima H, Arima S, Asayama K, Dohi Y, Hirooka Y, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2019). Hypertens Res. 2019;42:1235–481.

Nobles CJ, Mendola P, Mumford SL, Silver RM, Kim K, Andriessen VC, et al. Preconception blood pressure and its change into early pregnancy: early risk factors for preeclampsia and gestational. Hypertension. 2020;76:922–9.

Li N, An H, Li Z, Ye R, Zhang L, Li H, et al. Preconception blood pressure and risk of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia: a large cohort study in China. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:956–62.

Huai J, Lin L, Juan J, Chen J, Li B, Zhu Y, et al. Preventive effect of aspirin on preeclampsia in high‐risk pregnant women with stage 1 hypertension. J Clin Hypertens. 2021;23:1060–7.

Slade LJ, Mistry HD, Bone JN, Wilson M, Blackman M, Syeda N, et al. American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association blood pressure categories—a systematic review of the relationship with adverse pregnancy outcomes in the first half of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023;228:418–29.e34.

Suzuki H, Takagi K, Matsubara K, Mito A, Kawasaki K, Nanjo S, et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes according to blood pressure levels for prehypertension: a review and meta-analysis. Hypertens Res Pregnancy. 2022;10:29–39.

Ueda A, Hasegawa M, Matsumura N, Sato H, Kosaka K, Abiko K, et al. Lower systolic blood pressure levels in early pregnancy are associated with a decreased risk of early-onset superimposed preeclampsia in women with chronic hypertension: a multicenter retrospective study. Hypertens Res. 2022;45:135–45.

Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 692: emergent therapy for acute-onset, severe hypertension during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:e90–5.

Easterling T, Mundle S, Bracken H, Parvekar S, Mool S, Magee LA, et al. Oral antihypertensive regimens (nifedipine retard, labetalol, and methyldopa) for management of severe hypertension in pregnancy: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394:1011–21.

Bone JN, Sandhu A, Abalos ED, Khalil A, Singer J, Prasad S, et al. Oral antihypertensives for nonsevere pregnancy hypertension: systematic review, network meta- and trial sequential analyses. Hypertension. 2022;79:614–28.

Huang Q, Hu B, Han X, Yang J, Di X, Bao J, et al. Cyclosporin A ameliorates eclampsia seizure through reducing systemic inflammation in an eclampsia-like rat model. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:263–70.

Chen X, Huang J, Lv Y, Chen Y, Rao J. Crocin exhibits an antihypertensive effect in a rat model of gestational hypertension and activates the Nrf-2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Hypertens Res. 2021;44:642–50.

Chappell LC, Brocklehurst P, Green ME, Hunter R, Hardy P, Juszczak E, et al. Planned early delivery or expectant management for late preterm pre-eclampsia (PHOENIX): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394:1181–90.

Thilaganathan B, Kalafat E. Cardiovascular system in preeclampsia and beyond. Hypertension. 2019;73:522–31.

Vakhtangadze T, Gakhokidze N, Khutsishvili M, Mosidze S. The link between hypertension and preeclampsia/eclampsia-life-long cardiovascular risk for women. Vessel. 2019;3:19.

Google Scholar

Bellamy L, Casas J-P, Hingorani AD, Williams DJ. Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;335:974.

Minissian MB, Kilpatrick S, Eastwood J-A, Robbins WA, Accortt EE, Wei J, et al. Association of spontaneous preterm delivery and future maternal cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2018;137:865–71.

Leon LJ, McCarthy FP, Direk K, Gonzalez-Izquierdo A, Prieto-Merino D, Casas JP, et al. Preeclampsia and cardiovascular disease in a large UK pregnancy cohort of linked electronic health records. Circulation. 2019;140:1050–60.

Honigberg MC, Zekavat SM, Aragam K, Klarin D, Bhatt DL, Scott NS, et al. Long-term cardiovascular risk in women with hypertension during pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:2743–54.

Wagata M, Kogure M, Nakaya N, Tsuchiya N, Nakamura T, Hirata T, et al. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, obesity, and hypertension in later life by age group: a cross-sectional analysis. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:1277–83.

Wilson PWF, Polonsky TS, Miedema MD, Khera A, Kosinski AS, Kuvin JT. Systematic review for the 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:3210–27.

Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:1376–414.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Presidential Task Force on Pregnancy and Heart Disease and Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 212: pregnancy and heart disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e320–56.

Brown DW, Dueker N, Jamieson DJ, Cole JW, Wozniak MA, Stern BJ, et al. Preeclampsia and the risk of ischemic stroke among young women. Stroke. 2006;37:1055–9.

Poulter NR, Chang CL, Farley TMM, Meirik O, Marmot MG. Haemorrhagic stroke, overall stroke risk, and combined oral contraceptives: results of an international, multicentre, case-control study. Lancet. 1996;348:505–10.

World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contarception. Venous thromboembolic disease and combined oral contraceptives: results of international multicentre case-control study. Lancet. 1995;346:1575–82.

Samara AA, Liampas I, Dadouli K, Siokas V, Zintzaras E, Stefanidis I, et al. Preeclampsia, gestational hypertension and incident dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published evidence. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2022;30:192–7.

Hubel CA, Wallukat G, Wolf M, Herse F, Rajakumar A, Roberts JM, et al. Agonistic angiotensin II type 1 receptor autoantibodies in postpartum women with a history of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2007;49:612–7.

Zwertbroek EF, Franssen MTM, Broekhuijsen K, Langenveld J, Bremer H, Ganzevoort W, et al. Neonatal developmental and behavioral outcomes of immediate delivery versus expectant monitoring in mild hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: 2-year outcomes of the HYPITAT-II trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:154.e1–154.e11.

Burton GJ, Redman CW, Roberts JM, Moffett A. Pre-eclampsia: pathophysiology and clinical implications. BMJ. 2019;366:l2381.

Davis EF, Lazdam M, Lewandowski AJ, Worton SA, Kelly B, Kenworthy Y, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in children and young adults born to preeclamptic pregnancies: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1552–61.

Davisson RL, Hoffmann DS, Butz GM, Aldape G, Schlager G, Merrill DC, et al. Discovery of a spontaneous genetic mouse model of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2002;39:337–42.

Allotey J, Fernandez S, Bonet M, Stallings E, Yap M, Kew T, et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m3320.

Kalafat E, Prasad S, Birol P, Tekin AB, Kunt A, Di Fabrizio C, et al. An internally validated prediction model for critical COVID-19 infection and intensive care unit admission in symptomatic pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226:403.e1–403.e13.

Vivanti AJ, Vauloup-Fellous C, Prevot S, Zupan V, Suffee C, Do Cao J, et al. Transplacental transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3572.

Wei SQ, Bilodeau-Bertrand M, Liu S, Auger N. The impact of COVID-19 on pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can Med Assoc J. 2021;193:E540–E548.

Papageorghiou AT, Deruelle P, Gunier RB, Rauch S, García-May PK, Mhatre M, et al. Preeclampsia and COVID-19: results from the INTERCOVID prospective longitudinal study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:289.e1–289.e17.

Chmielewska B, Barratt I, Townsend R, Kalafat E, van der Meulen J, Gurol-Urganci I, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e759–e772.

Mendoza M, Garcia-Ruiz I, Maiz N, Rodo C, Garcia-Manau P, Serrano B, et al. Pre-eclampsia-like syndrome induced by severe COVID-19: a prospective observational study. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;127:1374–80.

Wu J, Deng W, Li S, Yang X. Advances in research on ACE2 as a receptor for 2019-nCoV. Cell Mol Life Sci CMLS. 2021;78:531–44.

Giardini V, Carrer A, Casati M, Contro E, Vergani P, Gambacorti-Passerini C. Increased sFLT-1/PlGF ratio in COVID-19: a novel link to angiotensin II-mediated endothelial dysfunction. Am J Hematol. 2020;95:E188–91.

Soldavini CM, Di Martino D, Sabattini E, Ornaghi S, Sterpi V, Erra R, et al. sFlt-1/PlGF ratio in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in patients affected by COVID-19. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2022;27:103–9.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Endocrinology and Hypertension, Tokyo Women’s Medical University, Tokyo, Japan

Kanako Bokuda & Atsuhiro Ichihara

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kanako Bokuda .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Bokuda, K., Ichihara, A. Preeclampsia up to date—What’s going on?. Hypertens Res 46 , 1900–1907 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-023-01323-w

Download citation

Received : 20 December 2022

Revised : 17 April 2023

Accepted : 02 May 2023

Published : 02 June 2023

Issue Date : August 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-023-01323-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1

- Placental growth factor

- Low dose aspirin

This article is cited by

Clinical features of recurrent preeclampsia: a retrospective study of 109 recurrent preeclampsia patients.

Hypertension Research (2024)

Advancements in microRNA-based electrochemical biosensors for preeclampsia detection

- Durairaj Sekar

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Practice Test

- Fundamentals of Nursing

- Anatomy and Physiology

- Medical and Surgical Nursing

- Perioperative Nursing

- Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing

- Maternal & Child Nursing

- Community Health Nursing

- Pathophysiology

- Nursing Research

- Study Guide and Strategies

- Nursing Videos

- Work for Us!

- Privacy Policy

Pregnacy Induced Hypertension (PIH) Case Study

Pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) is one of the most common complications of pregnancy. This occurs during the 20 th week of gestation or late in the second trimester of pregnancy. This is a health condition wherein there is a rise in the blood pressure and disappears after the termination of pregnancy or delivery. PIH was formerly called toxaemia or the presence of toxins in the blood. This is because its occurrence was not well understood in the clinical field. Its common manifestations are hypertension, proteinuria (presence of protein in the urine), and edema. There are 2 main types of pregnancy-induced hypertension namely: pre-eclampsia and eclampsia.

- Pre-eclampsia— this is the non-convulsive form of PIH. This affects 7% of all pregnant women. Its incidence is higher in lower socio-economic groups. It may be classified either mild or severe.

- Eclampsia— this is the convulsive form of PIH. It occurs with 5% of all pre-eclampsia cases. The mortality rate among mothers is nearly 20% and fetal mortality is also high due to premature delivery.

NORMAL ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

There are a lot of bodily changes that happen during a normal pregnancy. There are external changes that are noticeable, and there are internal changes that can only be appreciated through thorough clinical examinations. Most of the changes are the body’s response to the changes in levels of hormones and the growing demands of the fetus.

The two dominant female hormones, estrogen and progesterone , change in a normal level. Along with this, a significant rise/appearance of 4 more major hormones take place; these are 1. human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG), 2. human placental lactogen, 3. prolactin, and 4. oxytocin. All these 6 hormones interact with each other simultaneously to maintain a normal pregnancy as it progresses.

The following are the major effects of these hormones in the body:

The exact cause of pregnancy-induced hypertension is unknown; however, it is highly linked to angiotensin gene T235 and the existence of other risk factors. Malnutrition and inadequate prenatal care are the greatest risk factors. The history and presence of diabetes mellitus (DM), multifetal gestation (twin pregnancies), polyhydramnios (excessive amniotic fluid), and renal diseases are also among the major contributory factors in the development of PIH. In the past, the mystery revolving around PIH postulated a lot of theories on its true origin, most of them were believed to be of toxic nature. Among these are placental infarcts, autointoxication, uremia, pyelonephritis, and maternal sensitization to total proteins.

The i ncidence of PIH among pregnant women is very high (8%), costing hundreds and thousands of lives of both mothers and fetus around the world. This commonly affects first-time pregnancies due to the presence of functioning tropoblasts (develops after the 20 th week of gestation and stays evident until after 48 hours after delivery. Age is also an important indicator in the development of PIH. Too early, as in teenage pregnancies and old primigravidas (first-time pregnancy) as in over 35 years of age put a woman higher chances of having pregnancy-induced hypertension .

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The signs and symptoms of the type of PIH present in a pregnant woman are based on the presentation of evident clinical manifestations. These are shown in the table below:

COMPLICATIONS

Based on the severity of the PIH present to a person or the extent of damage left/occurred, a list of possible complications can be drawn.

- Abruption placenta

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

- Prematurity

- Intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR)

- HELLP syndrome

- Maternal and/or fetal death

The changes of the mother and/or fetus to survive after an episode of convulsion or until delivery depends on the threshold on the effects of PIH and its complications. This can be:

- Good— if the symptoms are mild or those that are with mild pre-eclampsia and is responding well to the treatment regimen

- Poor— if there are multiple and long episodes of convulsions that are associated or lead to the development of persistent coma, hyperthermia, cyanosis, tachycardia, and liver damage.

- Congestive heart failure (CHF)

- Pulmonary edema

- Cerebral hemorrhage

- Renal failure

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATIONS

Diagnostic evaluations are performed after episodes of convulsions or after the client has been rushed to a health care facility. These are routinely done to assess the damages and will serve as the basis for the plan of treatment.

- 24-hour urine-protein— health problem through protein determination from the involvement of the renal system.

- Serum BUN and creatinine— to evaluate renal functioning.

- Ophthalmic examination— to assess spasm, papilledema, retinal edema/detachment, and/or hemorrhages.

- Ultrasonography with stress and non- stress test— to evaluate fetal well-being after.

- Stress test —fetalheart tone (FHT) and fetal activity are electronically monitored after oxytocin induction which causes uterine contraction.

- Non-stress test —fetal heart tone (FHT) and fetal activity are electronically monitored during fetal activity (no oxytocin induction).

NURSING DIAGNOSES

- Fluid volume excess related to altered blood osmolarity and sodium/water retention.

- Altered nutrition, less than body requirements related to loss through damaged renal membrane.

- Altered tissue perfusion related to increased peripheral resistance and vasospasm in renal and cardiovascular system.

- Altered urinary elimination related to hypovolemia.

- Sensory/perceptual alterations: visual related to cerebral edema and decreased oxygenation of the brain.

- Diversional activity deficit related to decreased time for rest and sleep from stimulating environment.

- Risk for injury related to seizure episodes.

- Anxiety-related to fear of the unknown.

The overall goal of management in pregnancy-induced hypertension is directed towards the control of hypertension and the correction of developed health problems that might leadto other serious complications. Among the specially-designed treatment course for PIH are the following:

- Use of antihypertensive drugs (hydralazine-drug of choice)

- Diet-high protein, high calories

- Magnesium sulphate (MgSO4) treatment

- Diazepam and amobarbital sodium (if convulsions don’t respond to MgSO4)

- Beta-adrenergic blockers (used for acute hypertension)

- Delivery (if all treatment regimen don’t work)

NURSING MANAGEMENT

A. Assessment

- Monitor blood pressure in sitting or side-lying position.

- Monitor fetal heart tone (FHT) and fetal heart rate (FHR).

- Check for deep tendon reflexes (DTR) and clonus.

- Monitor intake and output (I&O) and proteinuria.

- Monitor daily weight and edema.

- Assess for signs of labor (possibility of abruption placenta).

- Assess for emotional status.

B. Interventions

1. Fluid balance

- Maintain patent and regulated IVF

- Strict I&O monitoring

- Monitor hematocrit level

- Vital signs monitoring every hour

- Assess breath sounds for signs of pulmonary edema

2. Tissue perfusion

- Position on left-lateral position

- Monitor fetal activity (stress and fetal activity)

3. Preventing injury

- Monitor cerebral signs and symptoms (headache, visual disturbances, and dizziness)

- Lie on left-lateral position if cerebral symptoms are present

- Secure padded side rails

- Keep oxygen suction set, tongue blade, and emergency medications (diazepam and magnesium sulphate) at all times

- Never leave an unstable patient

4. Anxiety

Discuss the health condition and planned treatment

- PIH is not lifetime

- PIH is only for the first pregnancy

- All medications and its maternal and fetal effects

Allow to ask questions and answer it truthfully

Provide emotional support to the client and family

C. Educative

- Reinforce the importance of rest and sleep

- Encourage family cooperation with the treatment course

- Discuss the laboratory procedures and alternative managements

- Include medical team, client, and significant others in the discussion

- Be realistic in discussing the possibilities of premature delivery

- No sign of pulmonary edema

- Adequate urine output

- No episode of seizure

- Stable and normal heart rate

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Anaphylactic shock case study -the impending doom, ectopic pregnancy case study, chronic suppurative otitis media case study, gestational diabetes mellitus case study, leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

A CASE STUDY ON LIFE-THREATENING PREGNANCY-INDUCED HYPERTENSION IN PRETERM PREGNANCY AND MANAGEMENT CHALLENGES

Related Papers

Introduction: Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are the most common causes of adverse maternal & perinatal outcomes. Such investigations in resource limited settings would help to have great design strategies in preventing maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality. All women who presented with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and delivered in the hospital and whose records were complete, were included in the study and divided into 5 groups namely, Gestational hypertension (GH), Mild pre-eclampsia (PE), Severe pre-eclampsia, Eclampsia and Chronic hypertension with superimposed pre-eclampsia (CHPE) based on their clinical presentation at admission. After excluding all incomplete data entries, the sample size was finalized at 200. Results: In this study, records of 2,989 women who delivered in our tertiary hospital were reviewed and of these, 256 women had hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Fifty six of these women had either left the hospital against medical advice or their records were incomplete so their outcome could not be followed and hence were excluded from the study. Conclusion: Pre-eclampsia and Eclampsia still remains a major problem in developing countries. Pregnancy induced hypertension is one of the most extensively researched subjects in obstetrics. Still the etiology remains an enigma to us. Though the incidence of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia is on the decline, still it remains the major contributor to poor maternal and foetal outcome. The fact that pre-eclampsia, eclampsia is largely a preventable disease is established by the negligible incidence of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia with proper antenatal care and prompt treatment of pre-eclampsia. In preclampsia and eclampsia, pathology should be understood and that i-involves multiorgan dysfunction should be taken into account. The early use of antihypertensive drugs, optimum timing of delivery and strict fluid balance, anticonvulsants in cases of eclampsia will help to achieve successful outcome. Early transfer to specialist centre is important and the referral the referral centers should be well equipped to treat such critically ill patients.

IOSR Journals

Back Ground: Aim: The Aim of the study was to find out the incidence of PIH & Preeclampsia and to evaluate the risk factors, predictors of severity and obstetrical and perinatal outcome in severe preeclampsia and Eclampsia.. Place and duration Methodology: Out of total 8800 deliveries 880 were diagnosed to have pregnancy induced hypertension. Out of these 580 (66%) had gestational hypertension. 80(0.9%) cases had preeclampsia without severe features, 220(2.5%) cases had preeclampsia with severe features. The present study was conducted in 200 cases of preeclampsia with severe features. The cases were evaluated and managed as per the existing protocol in the department and Obstetrical and perinatal outcome were recorded and analyzed. Results: The incidence of pregnancy induced hypertension was 10% and preeclampsia 3.5% in our study. 50% had anemia and 30% had obesity as risk factors. Materanl mortality was seen in 12cases of severe preeclamsia, accounting to 50% of total maternal deaths in our centre. Other maternal complications were seen in 60% of cases.Most common was Eclamsia in 30% of cases followed by Abruption in 20% & DIC in 18% and 20% of cases required transfusion of blood & Blood components for thrombocytopenia and coagulation failure. 10% cases required ventilator support for dyspneoa. Perinatal mortality was seen in 16% of cases. Perinatal morality is due to premaurity, low birth weight and abruption. NICU admissions were required in 20% of cases because of severe birth Asphyxia. Conclusion: Regular antenatal checkup and regular blood pressure measurement will help in early detection of hypertensive cases. Treating anemia and educating women on significance of alarming symptoms will improve maternal and perinatal outcome. Hospitalisation, regular BP monitoring, investigations and timely delivery will improve significantly the maternal and perinatal outcome. A good maternal intensive care unit and neonatal intensive care unit will help to improve obstetrical and perinatal outcome in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Hypertension in Pregnancy

Altaf shaikh

Corine Koopmans

https://www.ijhsr.org/IJHSR_Vol.11_Issue.1_Jan2021/IJHSR_Abstract.041.html

International Journal of Health Sciences and Research (IJHSR)

Background: Hypertension is one of the common medical complications of pregnancy & contributes significantly to maternal & perinatal morbidity & mortality. The World Health Organization estimates that at least one woman dies every seven minutes from complications of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Hence a study was undertaken to assess the impact of Pregnancy Induced Hypertension on fetal outcomes among mothers with PIH who delivered at tertiary care hospital, Dadra & Nagar Haveli. Method: It was a cross sectional study conducted at Shri Vinoba Bhave Civil Hospital, Silvassa, Dadra & Nagar Haveli from September to November 2020.The sample size of the study was 32. The data regarding demographic variables, obstetric history, clinical details & examinations, investigations & fetal outcomes was collected using Structured Interview Schedule. Result: In the present study, Gestational Hypertension was found to be 65.62%, Pre eclampsia was 28.12% and Eclampsia was found to be 6.25%. It was more prevalent among multipara mothers. The clinical representation of PIH showed that 71.87% mothers had pain in lower abdomen, 37.3% had pedal edema followed by 15.62% headache & 9.37% blurring of vision. Antihypertensive drugs (93.75%) were given to almost all the mothers whereas 9.37% were treated with anticonvulsant medicines. The most common fetal complications found were preterm births (43.75%) & LBW (37.5%). 28.12% babies required NICU admission due to various reasons whereas 6.25% neonatal deaths were reported. Conclusion: Pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders are common and adversely impact perinatal outcomes. Efforts should be made at both the community and hospital levels to increase awareness regarding hypertensive disorder of pregnancy and reduce its associated morbidity and mortality.

Clinical & Biomedical Research

Francisco Maximiliano Pancich Gallarreta

Scholar Science Journals

Background: Preeclampsia and eclampsia have been recognized as clinical entities since the times of Hippocrates. Pregnancy induced hypertension (PIH) is one of the commonest disorders associated with the increased risk of maternal and fetal complications. It is reported in the world literature that the incidence of eclampsia is on the decline, but still a menace in developing countries. Objectives: To study the maternal and foetal outcome in pregnancy induced hypertension. Material and Methods: A prospective randomized study was carried out A total of 100 pregnant women with PIH were enrolled in the study. A pre-tested interview tool was used to collect necessary information such as detailed history, clinical examination findings and investigations performed. Results were analysed using SPSS 13.0 Results: In the present study, the overall incidence of PIH was 8.96%, which includes preeclampsia in 7.26% and eclampsia in 1.70%. Preterm labour was the commonest maternal obstetrical complication observed in 18% of mild PIH and 48% of severe PIH cases. Prematurity was the commonest foetal complication seen in 17.99%, 47.62% and 52.63% of mild PIH, severe PIH and Eclampsia cases respectively. Conclusion: Pregnancy induced hypertension is a common medical disorder seen associated with pregnancy in the rural population, especially among young primigravidas, who remain unregistered during pregnancy. Maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality can be reduced by early recognition and institutional management.

American Journal of Pediatrics

Mustafa Captain

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics

Eray Çalışkan