- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What Really Makes Toyota’s Production System Resilient

- Willy C. Shih

“Just-in-time” only works as part of a comprehensive suite of strategies.

Toyota has fared better than many of its competitors in riding out the supply chain disruptions of recent years. But focusing on how Toyota had stockpiled semiconductors and the problems of other manufacturers, some observers jumped to the conclusion that the era of the vaunted Toyota Production System was over. Not the case, say Toyota executives. TPS is alive and well and is a key reason Toyota has outperformed rivals.

The supply chain disruptions triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic caused major headaches for manufacturers around the world. Nowhere was this felt more acutely than in the auto industry, which faced severe shortages of semiconductor chips and other components. This led many people to argue that just-in-time and lean production methods were dead and being superseded by “just-in-case” stocking of more inventory.

- Willy C. Shih is a Baker Foundation Professor of Management Practice at Harvard Business School.

Partner Center

ESG Case Study – Toyota Motor Corporation

February 24, 2021 — 02:59 pm EST

Written by [email protected] (ETF Trends) for ETF Trends ->

By Sara Rodriguez, Sage ESG Research Analyst

About Toyota Motor Corporation

Toyota Motor Corporation is a Japanese multinational automotive company that designs, manufacturers, and sells passenger and commercial vehicles. The company also has a financial services branch that offers financing to vehicle dealers and customers. Toyota is the second-largest car manufacturer in the world and ranked the 11th largest company by Forbes — and produces vehicles under five brands: Toyota, Hino, Lexus, Ranz, and Daihatsu. Toyota also partners with Subaru, Isuzu, and Mazda.

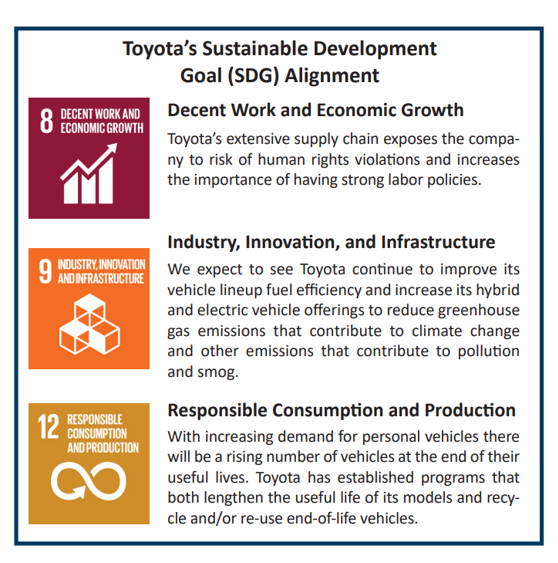

Environmental

Motor vehicles are one of the largest contributors to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and, as a result, climate change, with the transportation sector accounting for a third of U.S. GHG emissions in 2018. Although most emissions come from vehicle usage rather than the process of manufacturing vehicles, government regulations place the burden on auto companies to improve fuel efficiency and reduce overall emissions. While climate change regulations present financial risk to automakers, they also offer opportunities; increased fuel efficiency requirements are likely to lead to more sales of electric vehicles and hybrid systems. Toyota pioneered the first popular hybrid vehicle with the 1997 release of the Prius, the world’s first mass-produced hybrid. Since then, Toyota has sold 15 million hybrids worldwide . In 2018, hybrids accounted for 58% of Toyota’s sales, contributing to Toyota reaching substantially better carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from new vehicles than regulatory standards and the best levels in the industry (102.1g/km compared to U.S. regulation of 119g/km). In 2020, Toyota reduced global average CO2 emissions from new vehicles by 22% compared to 2010 levels by improving vehicle performance and expanding its lineup. Toyota’s goal is to increase that number to 30% by 2025, with the goal of 90% total reduction by 2050. The company aims to offer an electric version of all Toyota and Lexus models worldwide by 2025. (Toyota does not yet sell any all-electric vehicles to the U.S., but it does outside the U.S.)

In addition to greenhouse gases, cars emit smog-forming pollutants that contribute to poor air quality and trigger negative health effects. Recently, a London court ruled that air pollution significantly contributed to the death of a nine-year-old girl with asthma who had been exposed to excessive nitrogen dioxide (NO2) levels. NO2 is a toxic gas emitted by cars that use diesel fuel, and although European Union laws set regulatory levels for NO2 in the air, Britain has missed its targets for a decade due to a lack of enforcement. As Toyota expands into European markets, the smog rating of its cars will be financially material and an important aspect of risk management.

Compared to industry peers, Toyota excels in addressing emissions and fuel efficiency. In 2014 Toyota Motor Credit Corporation, the financial arm of Toyota Motor Corporation, introduced the auto industry’s first-ever asset-backed green bond and has since issued five total green bonds. The newest $750 million bond will go toward developing new Toyota and Lexus vehicles to possess a hybrid or alternative fuel powertrain, achieve a minimum of 40 highway and city miles per gallon, and receive an EPA Smog Rating of 7/10 or better. The bond program was reviewed by Sustainalytics, which found that Toyota leads its competitors in supporting its carbon transition through green bond investments.

In addition to curbing emissions caused by Toyota’s vehicles, the company seeks to reduce plant emissions to zero by 2050 by utilizing renewable energy and equipment optimization. In automaking, water is used in painting and other manufacturing processes. Toyota has implemented initiatives to reduce the amount of water used in manufacturing and has developed technology that allows the painting process to require no water. In 2019, Toyota reduced water usage by 5% per vehicle, with the goal of 3% further reduction by 2025, for an overall reduction of 34% from 2001 levels. To reduce the environmental impact of materials purchased from suppliers, Toyota has launched Green Purchasing Guidelines to prioritize the purchase of parts and equipment with a low environmental footprint. We would like to see Toyota continue to develop its supply chain environmental policies.

As the global population grows, so does number of cars on the road, which creates waste when they’ve reached the end of their useful lives. Toyota’s Global 100 Dismantlers Project was created to establish systems for appropriate treatment of end-of-life vehicles through battery collection and car recycling. Toyota aims to have 15 vehicle recycling facilities by 2025. Toyota is also working to minimize waste by prolonging the useful life of its vehicles. Toyota has a strong reputation for producing quality, reliable vehicles. Consumer Reports lists Toyota’s overall reliability as superb, and Toyota and Lexus often take the top spots in Consumer Reports Annual Auto Reliability Survey. An Iseecars.com study found that Toyota full-size SUV models are the longest-lasting vehicles and most likely to reach over 200,000 miles.

Driving is an activity with inherent risk. The World Health Organization estimates that 1.35 million people die in car accidents each year. Accidents are worse in emerging nations where transportation infrastructure has not kept up with the increase in the number of cars on the road; without countermeasures, traffic fatalities are predicted to become the seventh-leading cause of death worldwide by 2030. Demand for personal vehicles will continue to increase as developing countries experience higher standards of living, and product safety will be paramount to automaker’s reputations and brand values. Toyota has put forth a goal of Zero Casualties from Traffic Accidents and adopted an Integrated Safety Management Concept to work toward eliminating traffic fatalities by providing driver support at each stage of driving: from parking to normal operation, the accident itself, and the post-crash. Toyota and Lexus models regularly earn top safety ratings by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. In addition to traditional safety features, Toyota actively invests in the development of autonomous vehicles, including a $500 million investment in Uber and autonomous ridesharing. If fully developed, autonomous driving can offer increased safety to passengers, lower accident rates, and provide mobility for the elderly and physically disabled.

Accidents caused by defective vehicles can have significant financial repercussions for auto manufacturers. Toyota experienced significant damage to its reputation and brand value in 2009 when unintended acceleration caused a major accident that killed four people riding in a dealer-loaned Lexus in San Diego. Toyota subsequently began recalling millions of vehicles, citing problems of pedal entrapment from unsecured floor mats and “sticky gas pedals.” Toyota’s failure to quickly respond resulted in a $1.2 billion settlement with the Justice Department and $50 million in fines from the NHTSA. The scandal generated an extraordinary amount of news coverage, and the Toyota recall story ranked among the top 10 news stories across all media in January and February 2010. Litigation costs, warranty costs, and increased marketing to counter the negative publicity of the event were estimated to cost Toyota over $5 billion (annual sales are about $275 billion). As a result of bad press, Toyota’s 2010 sales fell 16% from the previous year and its stock price fell 10% overall, while competitors like Ford benefitted and experienced stock price growth of 80% over the same period. Future recalls and quality issues are certain to prove costly for Toyota and may continue to negatively impact its consumer reputation.

Another social issue that can be financially material for automakers is human rights. Automobiles consist of about 30,000 parts, making their supply chain extensive and at high risk for human rights abuses. Toyota addresses human rights concerns in its Corporate Sustainability Report (CSR) and cites Migrant Workers and Responsible Sourcing of Cobalt as its priorities for 2020; however, Toyota does not have a clean labor record. A 2008 report published by the Institute for Global Labour and Human Rights accused Toyota of a catalog of human rights abuses, including stripping foreign workers of their passports and forcing them to work grueling hours without days off for less than half of the legal minimum wage. Toyota was also accused of involvement in the suppression of freedom of association at its plant in the Philippines. Toyota’s CSR lists a host of external nongovernmental organizations the company partners with to promote fair working conditions, however; due to the high-risk present in its supply chain and its past offenses, we would like to see the company further develop its labor and human rights policies.

Lastly, we would mention that Toyota has been accused of discriminatory practices. In 2016, Toyota Motor Credit Corporation, the financial arm of Toyota Motor Corporation, agreed to pay 21.9 million in restitution to thousands of African American, Asian, and Pacific Islander customers for charging them higher interest rates on auto loans than their white counterparts with comparable creditworthiness. Toyota has since taken measures to change its pricing and compensation system to reduce incentives to mark up interest rates.

Toyota shows strength in its transparency, and its Corporate Sustainability Report (CSR) is prepared in accordance with multiple sustainability reporting agencies, including the Global Reporting Initiative, Sustainable Accounting Standards Board, and the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures; the CSR data is also verified by a third party. Starting in 2021, Toyota’s CSR will be updated whenever necessary to ensure timely disclosure, rather than annually. In 2019 Toyota created a Sustainability Management Department and added the role of Chief Sustainability Officer to its executive management team in 2020. Toyota’s CSR offers thorough information on its executive compensation policies, however; the composition of Toyota’s board of directors is an area of weakness for the company. There is a lack of independence among board members, and the chair of the board is not independent. In general, when compared to the U.S., Japanese companies have a smaller percentage of outside directors due to a history of corporate governance emphasizing incumbency and promotion from within. However, since the release of the Japanese Corporate Governance Code in 2015, companies have felt pressure to make meaningful board composition changes. We hope to see Toyota strengthen its board composition and adopt executive renumeration policies that are tied to sustainability performance.

Like other automakers, Toyota has lobbied aggressively to weaken Obama-era fuel economy standards. In 2017, the Environmental Protection Agency announced plans to work with Toyota to overhaul internal management practices at the agency. Inviting a company regulated by the agency to alter internal practices has been previously unprecedented and raises concerns over how Toyota could wield influence over EPA functions. Toyota is a member of the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers, the most powerful automotive industry lobbying association, which has strongly opposed climate change motivated regulation since 2016, contradicting the company’s public stance on emissions.

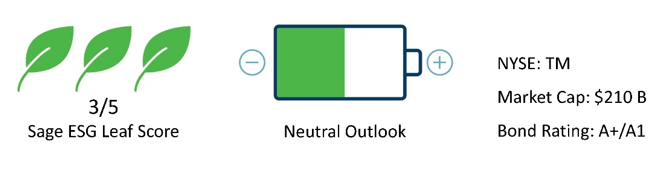

Risk & Outlook

Sage believes Toyota to be well adapted to manage sustainability challenges, despite the high environmental and social risks in the automotive industry. We expect the auto industry to see an increase in regulatory risk surrounding vehicle emissions and fuel efficiency; however, we believe Toyota will continue to innovate to meet and exceed emission standards and the company is well positioned to benefit from future fuel efficiency regulations. We hope to see Toyota continue to improve its social performance and expand on its recently introduced human capital policies. In addition to regulation, the auto industry faces disruption caused by new areas of technology such as automated driving, electrification, and shared mobility, and these areas will be important to monitor. Toyota’s strong management of ESG issues makes the company a leader amongst its peers; however, due to risk present in the automotive industry we rank Toyota a 3/5 for its Sage ESG Leaf Score.

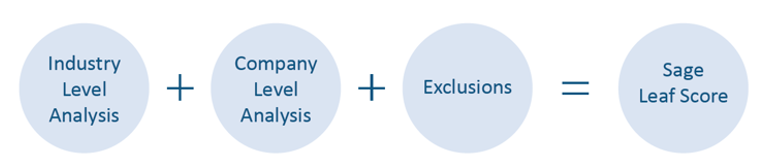

Sage ESG Leaf Score Methodology

No two companies are alike. This is exceptionally apparent from an ESG perspective, where the challenge lies not only in assessing the differences between companies, but also in the differences across industries. Although a company may be a leader among its peer group, the industry in which it operates may expose it to risks that cannot be mitigated through company management. By combining an ESG macro industry risk analysis with a company-level sustainability evaluation, the Sage Leaf Score bridges this gap, enabling investors to quickly assess companies across industries. Our Sage Leaf Score, which is based on a 1 to 5 scale (with 5 leaves representing ESG leaders), makes it easy for investors to compare a company in, for example, the energy industry to a company in the technology industry, and to understand that all 5-leaf companies are leaders based on their individual company management and the level of industry risk that they face.

For more information on Sage’s Leaf Score, click here.

Originally published by Sage Advisory

- ISS ESG Corporate Rating Report on Toyota Motor Corporation.

- Environmental Report 2020 Toyota Motor Corporation.

- Sustainability Data Book 2020 Toyota Motor Corporation.

- Lambert, Lisa. “Toyota Motor Credit settles with U.S. over racial bias in auto loans” February 2, 2016.

- “Automobiles” Sustainability Accounting Standards Board. September, 2014.

- Kaufman, Alexander. “Scott Pruitt’s Plan to Outsource Part Of EPA Overhaul to Automaker Raises Concerns” December 12, 2017.

- “How the US auto industry accelerated lobbying under President Trump” November, 2017.

- Charles Kernaghan, Barbara Briggs, Xiaomin Zhang, et al. “The Toyota You Don’t Know” Institute for Global Labour and Human Rights. 2008.

- Road Safety World Health Organization.

- Toyota Motor Credit Corporation Green Bond Framework Second-Party Opinion January 21, 2020.

- Toshihiko Hiura and Junya Ishikawa. "Corporate Governance in Japan: Board Membership and Beyond" Bain & Company. February 23, 2016.

- Taylor, Lin. ”Landmark ruling links death of UK schoolgirl to pollution" December 16, 2020.

Disclosures

Sage Advisory Services, Ltd. Co. is a registered investment adviser that provides investment management services for a variety of institutions and high net worth individuals. The information included in this report constitute Sage’s opinions as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice due to various factors, such as market conditions. This report is for informational purposes only and is not intended as investment advice or an offer or solicitation with respect to the purchase or sale of any security, strategy or investment product. Investors should make their own decisions on investment strategies based on their specific investment objectives and financial circumstances. All investments contain risk and may lose value. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Sustainable investing limits the types and number of investment opportunities available, this may result in the Fund investing in securities or industry sectors that underperform the market as a whole or underperform other strategies screened for sustainable investing standards. No part of this Material may be produced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without our express written permission. For additional information on Sage and its investment management services, please view our web site at www.sageadvisory.com, or refer to our Form ADV, which is available upon request by calling 512.327.5530.

The views and opinions expressed herein are the views and opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Nasdaq, Inc.

More Related Articles

This data feed is not available at this time.

Sign up for the TradeTalks newsletter to receive your weekly dose of trading news, trends and education. Delivered Wednesdays.

To add symbols:

- Type a symbol or company name. When the symbol you want to add appears, add it to My Quotes by selecting it and pressing Enter/Return.

- Copy and paste multiple symbols separated by spaces.

These symbols will be available throughout the site during your session.

Your symbols have been updated

Edit watchlist.

- Type a symbol or company name. When the symbol you want to add appears, add it to Watchlist by selecting it and pressing Enter/Return.

Opt in to Smart Portfolio

Smart Portfolio is supported by our partner TipRanks. By connecting my portfolio to TipRanks Smart Portfolio I agree to their Terms of Use .

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Case Analysis, Toyota: "The Lean Mind" 70 Years of innovation

This case study aims to reveal the reasons for Toyota's success and make its experience guide the developing brands to success.

Related Papers

helen turner

Long Range Planning

Peter J. Buckley

Mossimo Sesom

Deborah Nightingale

This Transition-To-Lean Guide is intended to help your enterprise leadership navigate your enterprise’s challenging journey into the promising world of “lean.” You have opened this guide because, in some fashion, you have come to realize that your enterprise must undertake a fundamental transformation in how it sees the world, what it values, and the principles that will become its guiding lights if it is to prosper — or even survive — in this new era of “clock-speed” competition. However you may have been introduced to “lean,” you have undertaken to benefit from its implementation.

Ayesha Majid , Yahya Rehman

Toyota is a name almost everyone is familiar with. It has been the market leader in automobiles specially hybrid and electric automobiles. It has been operational in Pakistan since 1989. Toyota is a one of a kind Japanese multinational automotive manufacturer. As of September 2018, it was the sixth largest company in the world in terms of revenue. The economic conditions however have not been very favorable for the automotive industry. The economy of Pakistan and the consistent increase in dollar rates has taken a huge toll on the sales of the multinational manufacturer. Focus group analysis show that majority of the people preferred Honda over Toyota due to several reasons including near to none change in the designs of Toyota Corolla’s variants. Another factor was that Toyota was seen more as a car for the rural areas which was best suited for a rugged terrain. Although the general perception is that Toyota has better car suspension and fuel efficiency, people would still prefer Honda and other Japanese cars. Respondents said that advertisements played a crucial role but they do not compel the customer to buy a product like a car, there are other factors that are taken under consideration. Pakwheels and olx were the first two online platforms that they mentioned when asked about their go to online source. Family and friends advice played a major role in deciding which car to buy. According to the research conducted by our group through questionnaire, a regression was done and seen that the general perception that a reduction in prices will increase sales was not true because people usually associate low prices with low quality products. According to the regression, only advertisement and product have a significant result. All the variables are positively correlated with each other and less than one and positive indicating a formative relationship to the dependent variable. Branding has an insignificant positive relationship with purchase intention because consumers are only considering three competitors; Honda, Suzuki and Japanese cars.

Volume III of this guide may be used as an in-depth reference source for acquiring deep knowledge about many of the aspects of transitioning to lean. Lean change agents and lean implementation leaders should find this volume especially valuable in preparing their organizations for the lean transformation and in developing and implementing an enterprise level lean implementation plan. The richness and depth of the discussions in this volume should be helpful in charting a course, avoiding pitfalls, and making in-course corrections during implementation. We assume that the reader of Volume III is familiar with the history and general principles of the lean paradigm that are presented in Volume I, Executive Overview. A review of Volume II, Transition to Lean Roadmap may be helpful prior to launching into Volume III. For those readers most heavily involved in the lean transformation, all three volumes should be understood and referenced frequently.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > Strategic Management - a Dynamic View

Organizational Identity, Corporate Strategy, and Habits of Attention: A Case Study of Toyota

Submitted: 20 April 2018 Reviewed: 24 August 2018 Published: 31 December 2018

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.81117

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Edited Volume

Strategic Management - a Dynamic View

Edited by Okechukwu Lawrence Emeagwali

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

1,966 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

This chapter links organizational identity as a cohesive attribute to corporate strategy and a competitive advantage, using Toyota as a case study. The evolution of Toyota from a domestic producer, and exporter, and now a global firm using a novel form of lean production follows innovative tools of human resources, supply chain collaboration, a network identity to link domestic operations to overseas investments, and unparalleled commercial investments in technologies that make the firm moving from a sustainable competitive position to one of unassailable advantage in the global auto sector. The chapter traces the strategic moves to strength Toyota’s identity at all levels, including in its overseas operations, to build a global ecosystem model of collaboration.

- institutional identity

- lean management

- learning symmetries

- habits of attention

Author Information

Charles mcmillan *.

- Schulich School of Business, York University, Toronto, Canada

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected]

(Article for Lawrence Emeagwali (Ed.), Strategic Management . London, 2018)

October 18, 2018.

“There is no use trying” said Alice, “we cannot believe impossible things.”—Lewis Carroll

1. Introduction

Few organizations combine the institutional benefits of longevity and tradition with the disruptive startup advantages of novelty and suspension of path dependent behavior. This chapter provides a case study of Toyota Corporation, an organization with an explicit philosophy that embodies “…standardized work and kaizen (that) are two sides of the same coin. Standardized work provides a consistent basis for maintaining productivity, quality and safety at high levels. Kaizen furnishes the dynamics of continuing improvement and the very human motivation of encouraging individuals to take part in designing and managing their own jobs” ([ 1 ], p. 38). Toyota’s philosophy, combining a model that is “stable and paranoid, systematic experimental, formal and frank” [ 2 ], often called the Toyota Way, evolved from the founding of Toyoda Automatic Loom Works, founded in 1911, setting up an auto division in 1933, and Toyota Motor Company in 1937 [ 3 ].

What is unique about Toyota and its pioneering lean production, described colloquially as just-in-time (JIT), embraces a deliberative philosophy that establishes a corporate identity for safety, quality, and aspirational performance goals. Going forward, with plants and distribution centers around the world, Toyota cultivates a direct involvement of employees, suppliers, and other organizations, called the Toyota Group, as a network identity that extends boundary members of the firm’s eco-system that also embodies detailed performance measures to strengthen and reinforce identity enhancement. These identity attributes creating novel and seemingly contradictory configurations, both at home and now in global markets. Toyota provides a framework to link identity as a cohesive attribute for problem-solving with explicit, data-driven benchmarks, a DNA that encompasses observation, analysis, hypothesis testing from the shop floor to the executive suite [ 3 , 4 ].

The concept of identity has a long pedigree in the social sciences, dating from classical writers like Adam Smith, Karl Marx, Max Weber, and Emile Durkheim, focusing on individual identities separate and distinct from larger social systems arising from the division of labor. However, identity in organizations is a relatively new construct, based on claims that are “central, distinctive, and enduring” [ 5 ]. Despite the growing literature on organizational identity [ 6 , 7 ], there is less consensus given the multiple disciplinary focus, the levels of analysis, well as minimum empirical work linking organizational identity to corporate strategy. In some cases, identity linkages touch on outcomes like brand equity, reputation, visual media like social networking and the gap between defining what the organization is today and what it wants to become, despite the high failure rate of firms [ 8 ]. Indeed, there is little reason to doubt that “the concept of organizational identity is suffering an identity crisis” ([ 9 ], p. 206).

Despite the growing literature on organization identity, encompassing diverse constructs and methodologies [ 6 , 7 ], often at different organizational levels (individuals, groups and senior management), has limited empirical study linking individual and group identity both to corporate strategy and corporate performance. Various accounts of social experiences, concentrating on a sense of insider and outsider to frame a mutual identity mindset that shapes organizational identity, apply personal histories and narratives, but leave open the distinction between corporate identity and organizational identity [ 10 ]. Identity producing mechanisms flowing from purposeful actions vary by context, such as universities and faith-based organizations to technology and engineering organizations with complicated role activities grounded in socio-technical design [ 11 ]. Compelling cases of identity as a tool for organizational integration, or the impact of cleavage and conflict owing to human diversity policies, personality characteristics of key actors, and sub-unit identity images advance understanding of behavior within organizations, but often ignores how both strategic choice and external forces impact these internal mindsets. Many scholars associate internal identity issues to external stakeholders using sundry communication tools (e.g., [ 12 ]) but the literature has few studies that explain what organizational identity features are truly different and give a competitive advantage in contested markets over time. To advance hypothesis testing and to encourage conceptual development in both theory and practice, there must be a linkage to identity as a construct that provides insights to an organization’s competitive advantage.

This chapter addresses the issues linking strategic choices and capabilities to Toyota’s identity as a case study. Toyota’s strategic positioning and high-performance outcomes amplify identity tools at three levels, its employees (both in Japan and its factories overseas), its suppliers, and its customers. Depicted as a best practice company [ 13 ], Toyota is seen as a model to emulate in sectors as diverse as hospitals and retailing. This chapter has three objectives: first, by examining Toyota’s transformation as a leading domestic producer to a top global company, the firm’s core identity has changed little despite numerous internal and external changes; second, Toyota as a case study illustrates the capacity to have multiple images in different contexts, without sacrificing its core identity; and third, the chapter offers recommendations for empirical studies of organizational identity.

2. Organizational identification and identity

In their seminal article, Stuart and Whetten [ 5 ] put forward the concept of organizational identity constituting a set of “claims” and specified what was central, distinctive and enduring, but recognizing that organizations can have multiple identities and claims that can be contradictory, ambiguous, or even unrelated. While some authors have attempted to provide more clarity, Pratt addresses the construct of identity and its generality, stating it was “often overused and under specified” beyond general statements about “who are we?” and “who do we want to become?”

Historically, identity and identification are described in classical writings focusing on societies, social systems, and their constituent parts. Such examples as Adam Smith in economics on the division of labor, Babbage on the division of work tasks, Marx on division of social class, Max Weber on the division of status and occupation, and Durkheim on differentiated social structures, each contributed to current views of how individuals, groups, and teams become a cohesive collective in a complex organization. More specifically, Durkheim’s [ 14 ] analysis of the division of labor and differentiated social structures with distinct socio-psychological values and impacts required variations in role homogeneity in sub-systems. 1 His views influenced subsequent writers as diverse as Freud in psychiatry and Harold Laswell in political theory, whose study of world politics includes a chapter entitled “Nations and Classes: The Symbols of Identification.”

Simon [ 15 ] introduced identification to organization theory, describing it as follows: “the process of identification permits the broad organizational arrangements to govern the decisions of the persons who participate in the structure” (p. 102). More specifically, “a person identifies himself with a group when, in making a decision, he evaluates the several alternatives of choice in terms of their consequences for the specified group” in contrast to personal motivation, where “his evaluation is based upon an identification with himself or his family” ([ 16 ], p. 206). Both the fault lines of identity, based on status, perverse incentives, class or occupation, as well as group identification [ 17 ] impact organizational performance by variations in shared goals and preferences, as well as forms of interaction and feedback, often enhanced or lessoned by recruitment patterns and work rules and incentives.

Identity and identification as reference points in organizations also flow from the configuration of roles, role structures, and “clusters of activities” where “a person has an occupational self-identity and is motivated to behave in ways which affirm and enhance the value attributes of that identity” ([ 18 ], p. 179). Theories of social identity assume individual identity is partitioned into ingroups and outgroups is social situations and organizational life, often with an implicit cost–benefit calculation, but acts of altruistic behavior, where behavioral norms benefit the welfare of others, often seen in “collectivist societies,” strengthens organizational identity [ 19 ]. Other approaches take a social constructionist approach, emphasizing social and cultural perspectives [ 20 ], where sense-making comes from stories and narratives of everyday experience [ 21 ], thereby, “…in linking identity and narrative in an individual, we link an individual [career] story to a particular cultural and historical narrative of a group” [ 22 ]. Going further, Dutton et al. [ 23 ] speculate that organizational identification is a process of self-categorization cultivated by distinctive, central, and enduring attributes that get reflected in corporate image, reputation, or strategic vision. Alvesson [ 24 ] describes the need for identity alignment: “…by strengthening the organization’s identity—its experienced distinctiveness, consistency, and stability—it can be assumed that individual identities and identification will be strengthen with what they are supposed to be doing at their work place.”

While some studies [ 25 ] purport to focus on managerial strategies that project images as a tool to shape distinctive identities with stakeholders, the reality is that organizational identities without corresponding integration of individual, sub-unit, or group identification may lead to behavioral frictions, and detachment via lower compliance and cues of detachment. Conflict and cleavages affect group-binding identification, often persisting as conformity of opinion, forms of social interaction, and group loyalties, as well as enhancing internal legitimacy for desired outcomes. While both individuals and groups may have multiple and loosely connected identities, there remains lingering organizations dysfunctions that exacerbate cleavage and conflict, such as hypocrisy, selective amnesia, or disloyalty [ 18 ]. Psychological exit comes from unsatisfactory outcomes, a form of weakening organizational identity and strengthening group identity to give voice for remedial actions [ 26 ]. In the extreme, such sub-identities found in groups and sub-units compete with other forms of identification and may lead to organizational dysfunctions [ 17 ].

Akerlof and Kranton [ 27 ] view organizational identity, with emphasis on why firms must transform workers from outsiders to insiders, as a form of motivational capital. In short, a distinctive identity is a distinctive competence. To quote Likert [ 28 ]. “the favorable attitudes towards the organization and the work are not those of easy complacency but are the attitudes of identification with the organization and its objectives and a high sense of involvement in achieving them” (p. 98). Other theorists suggest variations in organizational identity impact sense-making and interpretative processes [ 29 ], internalization of learning [ 10 ] and processes linking shared values and modes of performance [ 30 ].

Identity and identification cues, viewed as the mental perceptions of individual self-awareness, social interactions and experiences, and self-esteem have many antecedents, such as social class [ 31 ], demographic factors like age, race, religion, or sex [ 32 ], and national culture and identity [ 33 ]. Studies emphasizing social construction perspectives stem from individual accounts, often defined in social narratives, histories, and biographies rooted in time and place [ 34 ]. As Hammack [ 22 ] emphasizes, “…in linking identity and narrative in an individual, we link an individual story to a particular cultural and historical narrative of a group” (p. 230). At a general level, organizational culture depicts the set of norms and values that are widely shared and strongly held throughout the organization [ 35 ], and refers to the “unspoken code of communication among members of an organization” [ 36 ] and aids and supplements task coordination and group identity. In this way, individual employees better understand the premises of decision choices in problem solving at the organizational level. In complex organizations, identity is linked to the strategic capacity of choice opportunities and implementation dynamics of priorities and preferences. As Thoenig and Paradieise [ 37 ] emphasize, “strategic capacity lies to a great extent in how much its internal subunits … shape its identity, define its priorities approve its positions, prepare the way for general agreement to be adopted on its roadmap and provide a framework for the decisions and acts of all its components” (p. 299).

Such diverse views leave open how organizational identity, or shared central vision, confers competitive advantage in contested spaces. As a starting hypothesis, a shared identity strengthens coordination across diverse groups applying common norms, codes and protocols, hence improving shared learning skills. In a similar vein, individual cleavages and loyalties are lessoned by shared interactions and information sharing that mobilize learning tools. Further, organizational identity strengthens individual identities via performance success that promotes a shared set of preferences, expectation, and habits of rule setting.

3. Organizational performance at Toyota

By any standards—shareholder value, product innovation, employee satisfaction measured by low turnover and lack of strike action, market capitalization—Toyota has been astonishingly successful, both against rival incumbents in the auto sector, but as a organizational pioneer in transportation with just-in-time thinking. Against existing rivals at home, or in an industry with firms pursuing growth by alliances and acquisition (Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi, VW-Porsche), facing receivership and saved by public funding (GM and Chrysler), exiting as a going concern (British Leyland) or new startups (Tesla). Toyota’s performance is unrivaled. Toyota remains a firm committed to organic development, steady and consistent market share in all key international markets, and cultivating a shared identity within its eco-system around measurable outcomes of product safety, quality, and consumer value.

As shown in Figure 1 , despite many forms of competitive advantages, such as size, high domestic market share, being part of a larger group, or diversification, there are many times when the side expected to win actually is less profitable and may actually lose. Toyota’s growth and expansion, despite the turbulent 2009 recall and temporary retreats [ 38 , 39 ], comes with consistent profitability and market share growth. In this organizational transformation, Toyota has replicated its identity of “safety, quality, and value” outside its home market, often depicted by foreigners as “inscrutable,” closed, and Japan Inc. [ 40 ]. Strategically, this organizational identity framework is multipurpose, allowing shared alignment of identities with domestic employees, suppliers and supervisors, but also incorporating these identity attributes first to foreign operations in North America and subsequently to Europe and Asia. Toyota management considers the firm as a learning organization, where learning symmetries take place at all levels, vertically and horizontally.

Operating Profits versus Firm Revenues in the Auto Sector.

Unlike many corporate design models of multinationals, where foreign subsidiaries passively replicate the production systems of the home market (a miniature replica effect) or seek out decision-attention from head-quarters [ 41 ] Toyota is evolving as a global enterprise. In this model, Toyota’s foreign subsidies and trade blocks (e.g., NAFTA and Europe), solve key problems and translate the protocols for headquarters and its global network of factories, distribution outlets, and service and maintenance dealerships. In this way, Toyota’s training protocols, network learning systems, and using foreign subsidies to develop new technologies (e.g., Toyota Canada pioneering cold weather technologies for ignitions engineering), i.e., a learning chain that mobilizes employee identity to network identity, including its global supply chain collaboration [ 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 ].

To illustrate the complexity of contemporary auto production and the need to evolve both organizational design around supply chains, and the nature of complementarities in production, firms like Toyota must realign engineering and technological systems to novel role configurations for a diverse workforce. A car (or truck) has over 5000 parts, components, and sub-assemblies, where factories are linked to diverse supply chains with tightly-knit communications and transport linkages, often across national boundaries, to produce a factory production cycle of 1 minute per vehicle, or even less. Parts or components like steel, for instance, are not commodities, undifferentiated only by price, and Japanese steel producers produced the high carbon steel that was more resistant to water, hence rust. This production cycle demands very high quality and safety of each part and component, plus the precision engineering processes to assemble them. This alignment determines not only the standards of quality and safety of the finished vehicle but the image and reputation of the company, plus an indispensable need to retain price value of the brand in the aftermarket sales cycle.

To this contemporary production system, reshaped and refined since Toyota first introduced in 1956 what Womack et al. [ 46 ] termed “the machine that changed the world,” auto production now faces a steady, relentless, and inexorable technology disruption. This shift in engines and fuel consumption technologies, away from diesel and gasoline-powered vehicles, to new dominant technologies, such as electric vehicles, fuel-cells, battery, hydrogen, or hybrid, each requiring massive changes to traditional parts and components suppliers, and the layout of factory assembly. Successful firms thus require forward-looking strategic intent and novel organizational configurations both to exploit existing systems based on gasoline vehicles, or novel organizational systems to explore new technologies and processes. Strategies differ widely. Tesla as a new startup has dedicated factories and labs using lithium battery technology. To gain equivalent scale of Toyota, GM, and Volkswagen, i.e., over 10 million vehicles per year, Nissan and Renault joined with Mitsubishi as a new alliances and equity investment partner.

By contrast, both Ford and GM are retreating from large markets like Europe, Japan, or India with direct-foreign investment strategies. Even more intrusive to existing production programs and protocols are new demands for data analytics, artificial intelligence, robotic and associated Internet and social media technologies. Both incumbent firms, new startups, and suppliers are developing futuristic technologies in drivers’ facial recognition, driving habits, and consumer disabilities, from wheel chairs to hearing that impact cars of the future, and impose threats to existing distinctive competences and corporate identity. Not all firms can manage simultaneously the processes of exploitation of existing organizational programs, and the exploration of product innovation and assembly [ 47 ]. Toyota is an exception.

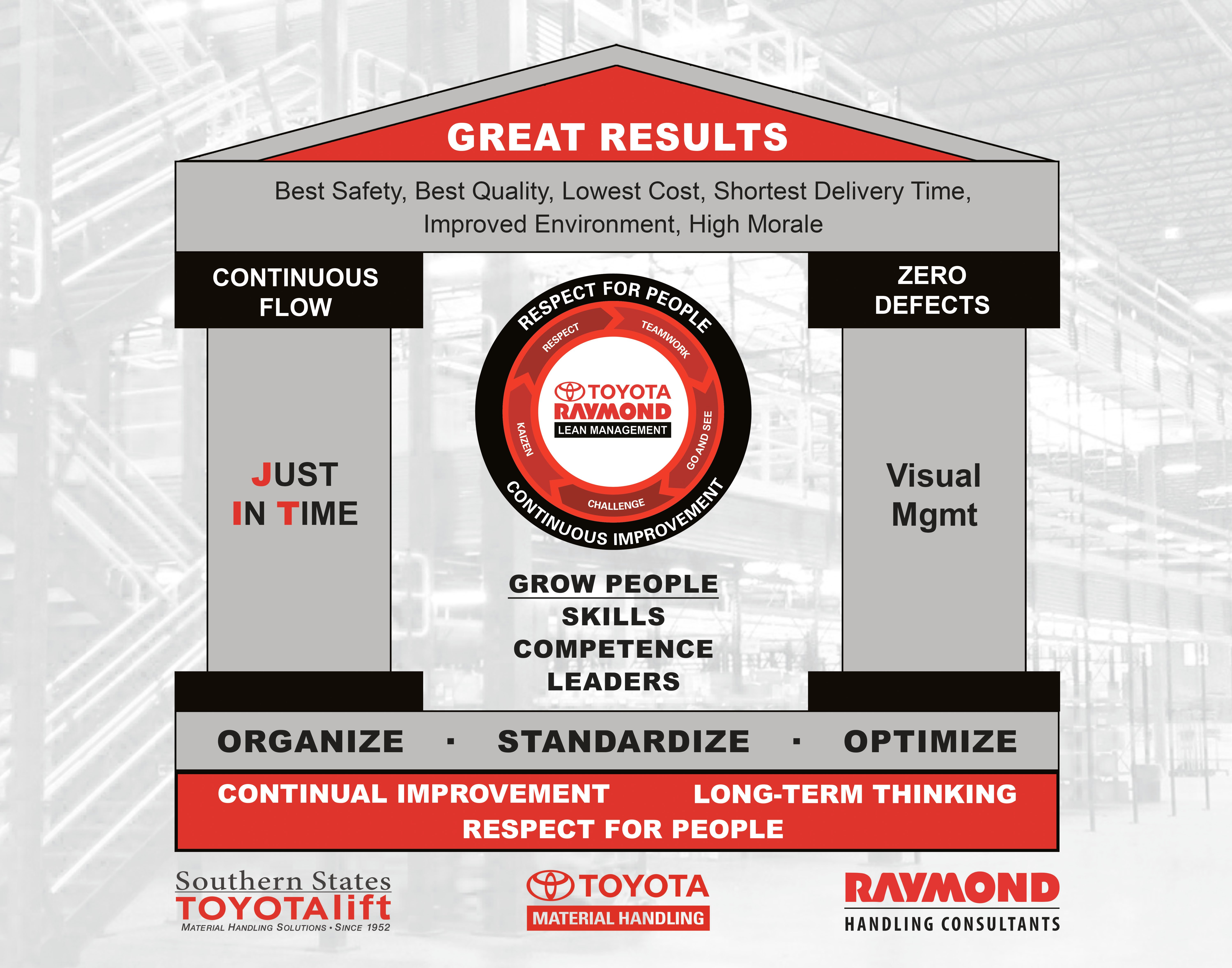

The Toyota production system is transformational, an organizational philosophy around two core ideas, kaizen or principles of continuous improvement, and nemawashi , or consensus decision-making that allow network effects across its global factories, research labs, its supplier organizations, and related parts of the global eco-system, from universities to global shipping firms. In the firm’s century-old evolution, starting as a leading textile firm that still exists but migrating to auto manufacturing as only the second largest by unit sales (behind Nissan), Toyota has emerged as the top producer both at home and globally, measured by market share, and a leading player in markets like North America, Europe, Latin America, India and China, where many rivals have a low market share presence (e.g., Europe firms in the US, American firms in Europe).

Strategies of corporate retreat in key markets (GM in Europe, GM and Ford in India, Ford in Japan), suggest home market advantages are the new testing ground for first-mover disadvantage [ 48 ] when firms face massive technology disruption. To cite an example, during the 1990s, four major automakers, Toyota, GM, Honda, and Ford, took the lead in the development of hybrid technologies, with GM the leader with 23 patents in hybrid vehicles (vs. 17 for Toyota, 16 for Ford, and 8 for Honda). By 2000, however, Honda and Toyota were the clear leaders, with Honda had filed 170 patents, and Toyota with 166 in hybrid drivetrain technology, far ahead pf Ford with 85 and GM at 56. Today, Fords’ hybrid is a license from Toyota.

4. Toyota identity as a social construct

The auto sector symbolizes the development of post-war multinationals largely based on firm-specific capabilities and proprietary advantages. This organizational evolution includes changing work mechanisms characterized as machine theory by management [ 49 ], a catch-all phrase to describe scientific management techniques espoused by Frederick Taylor from his 1911 book with that title. He first learned time management at Philips Executer Academy and became an early practitioner of what became known as kaizen, continuous improvement, working with Henry Gantt [ 50 ], studying all aspects of work, tools, machine speeds, workflow design, the conversion of raw materials into finished products, and payment systems. The Taylor studies, later dubbed Fordism [ 51 ], was an approach to eliminate waste and unnecessary movements, or “soldiering”—a deliberate restriction of worker output.

Taylor’s disciples in the engineering profession spread his message beyond America, to Europe, as well as to Japan and Russia, where even Lenin and Trotsky developed an interest after the Revolution of 1917. In appearances before Congressional committees, and in other forums, Taylor’s theories faced withering criticisms and great resistance by American union movement a “dehumanizing of the worker” and a tool for profits at the expense of the worker. [ 50 , 52 ]. In Japan, however, Taylorism and scientific management had wide acceptance, starting with Yukinori Hoshino’s translation of Principles of Scientific Management with the title, The Secret of Saving Lost Motion, which sold 2 million copies. Several firms adopted scientific management practices, including standard motions, worker bonuses, and Japanese authors published best sellers on similar notions of work practices, including one entitled Secrets for Eliminating Futile Work and Increasing Production [ 3 ].

After 1945 in Japan, given the wartime devastation of Japan’s industrial capacity, resource scarcity—food, building supplies, raw materials of all sorts, electric power—had a profound and lasting impact on Japanese society, even more so when the American military supervised the Occupation and displayed abundance of everyday goods—big cars, no shortage of food, long leisure hours, and consumer spending using American dollars. As Japanese firms slowly rebuilt, the corporate ethos promoted efficient use of everything, and waste became a watchword for inefficiency. Japanese executives visited US factories, the Japanese media documented US success stories. American management practices were widely emulated, and US consultants—notably Peter Drucker, W. Juran, and W. Edwards Deming—had an immense following and their books, papers and personal appearances were publicized, translated and widely-read, even by high school students. While American firms emphasized a marketing philosophy where the customer is king, Japanese firms remained committed to production, helped in part by trading firms, led by the nine giant Soga Sosha , to distribute and sell both at home and abroad. US human resource practices also showed a stark contrast with Japanese practices. In the US, the rise of the trade union movement and national legislation from Roosevelt’s New Deal, meant that management-worker relations for firms and factories were contractual, setting out legal norms, and negotiated commitments for pay, seniority, promotion, job rotation and skills differentials, so that worker identity was less towards the firm, more to the trade union, and what incentives and compensation union leadership could deliver [ 53 ].

Japan industrial firms, by contrast, cultivated three features of management-worker relations. The first was life time employment—once hired, the employee stayed in the firm until retirement. Second, wages and compensation were determined by seniority—young workers received lower wages and bonus compensation, just as older workers were paid more relative to their actual productivity. And third, firms had enterprise unions, as distinct from industry unions in the US and Europe (e.g., unions autoworkers, coal workers or shipbuilders). All three characteristics greatly extended the psychological linkages between employee identity and the firm’s identity, and the employee’s career success was directly tied to the firm’s success. In Japan, with very low turnover, but high screening processes, firms hired the best graduates, and training was on-going and formed part of the job description, with little layoffs, firing, or absenteeism. Additionally, there was little employee fear of adopting new technologies. Abegglen and Stalk [ 54 ] describe the implication of technological diffusion as follows: “…it is the relatively close identification of the interests of kaisha and their employees that have made this rate of technological change possible and the patterns of union relations implicit in that degree of identification” (p. 133). Indeed, some writers go further, citing how the human resource system was imposed on a Confucian society, with an ethos to govern individual and group interactions for reciprocal benefits, in a market system of winners and losers. As Morishima [ 55 ] puts it, Korea and China chose Confucianism with the market, Japan chose the market with Confucianism, while North America and Europe were characterized by Protestant-driven market behavior of winners and losers. For Toyota, a family enterprise with links to many sectors like steel, textiles, aviation and machinery, the post-war environment brought inevitable contracts with American automotive practices.

Okika [ 56 ] describes the implications of the evolving Japanese model of labor-management relations in the firm:

Japanese enterprises made their decisions by gaining an overall consensus through repeated discussions starting from the bottom and working up … making it easier for workers to accept technical innovation flexibly. For a start, that sense of identity with the firm is strong and they are aware that the firm’s development is to their own advantage, so they tend to improve the efficiency of its production system and strengthens its competitiveness (p. 22).

Across Japan, industrial firms, from Sony to Canon, recruited workers from rural areas, executives read US textbooks, and many visited US factories to study management practices. The production focus of Japanese firms, in a competitive environment of limited slack, hence the need for managerial improvisation and what the French call bricolage , i.e., making do with what is available [ 57 ]. In operational terms, this meant long production runs, division of labor taken to the extreme is monotonous assembly work tasks, product output determined by managerial estimates of demand, and wide use of buffer stocks to absorb varying time cycles of different sub-assembly needs. Buffer stocks also allowed conflicting management department goals to get sorted out with little time constraints, and less need to focus on quality issues based on bad product design, resource waste (e.g., steel), or timing processes that lead to product defects. Organizational reforms widely adopted across US industry, such as product divisions for large enterprises, largely left the product system intact, allowing middle management to focus on coordination between operational benchmarks at the factory level and financial benchmarks imposed by top management [ 58 ]. GM was seen in Japan as the prototype models to emulate.

5. Challenges to orthodox industrial production

The advance of industrialization involved new methods of energy, raw materials, dominant technologies, and organizational configurations [ 58 ] but relatively little to consideration actual production systems, especially after Henry Ford introduced mass production using interchangeable parts. As foreign executives visited Ford’s assembly lines, there were dissenting opinions, such as Czech entrepreneur Thomas Bata and S. Toyoda who worked a year in Detroit. How could three core concepts be integrated—craft skills of custom-made products like a kimono or a house, the volume-cost advantages of mass production, and the nigh utilization capacity of process production in beer or chemicals?

Toyota’s introduction of the lean production system has been widely studied, 2 including its the origins in the 1950s by Ohno [ 62 ], when visiting America and adopting ideas from super market chains, and had strong views on scientific management’s focus on the total production system, and Japanese concepts of jishu kanri (voluntary work groups). Japanese managers had both knowledge and experience with traditional crafts sectors like woodblock prints and silk designs in textiles or the long training needed for Japan’s culinary arts. How could three core concepts be integrated—craft skills of custom-made products like a kimono or a house, the volume-cost advantages of mass production, and the nigh utilization capacity of process production in beer or chemicals?

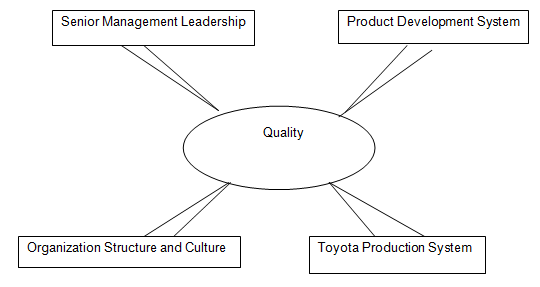

Core concepts of lean production is the desire to maximize capacity utilization, by reducing production variability and minimize excess inventories with a view to eradicating waste [ 54 ]. But other factors are critical, such as supplying high quality workmanship of craft production, reducing per unit costs via mass production using interchangeable parts, and high capacity utilization of continuous flow production, typically seen as three distinct systems. The ingrained ethos of resource scarcity in Japanese society, demonstrating that low slack in organizations encourage search behavior [ 63 ], and these requirements required pooling of efforts as an organizational philosophy ( Figure 2 ).

Contrasts Between Traditional Technical Design and Toyota’s Model.

To perfect the system over time, starting in the 1960s, Toyota accelerated the adoption of high work commitment by organizing workers in teams, reducing the number of job classifications, seeking suggestions from employees, and investing in training of new workers, 47–48 days per worker, compared to less than 5–6 days for US plants, 21–22 days for European plants [ 3 ]. The focus on production as an integrated system, using hardware ideas like quick die change equipment, robots, and advanced computer-aided design, also meant removing traditional tasks that are noisy, hard on the eyes, or dangerous to allow employees to concentrate on tasks like quality assessment, and allowing a worker to stop the entire production line, known as andon, in the case of equipment problems, shortage of parts, and discovery of defects, i.e., transferring certain responsibilities from managers and supervisors to workers [ 60 ]. Paradoxically, Toyota and other Japanese auto plants were far less automated than their foreign-owned rivals, not just for assembly line work but other tasks like welding and painting.

Einstein once said, “Make everything as simple as possible, but no simpler.” Simplicity became a watchword in the evolution of Toyota’s lean production system, a contrast to the complicated vertical integration model adopted in Detroit. Toyota adopted a highly focused structural design, becoming a systems assembler and sourcing from dedicated suppliers, each with core competences in specialized domains and technologies. Production engineering—e.g., craft, mass assembly or process systems—became central features as organizational configuration, choosing from the strengths of each but discarding the perceived weaknesses. Stress was place on the worker, avoiding the monotonous routines of a moving assembly line, by including job rotation and special training to apply quality management circles within a group structure. The advantages of process manufacturing as high capacity utilization came from high initial overhead of equipment and overhead, including IT investments, but allowing flexibility in machine set up, such as quick die change that reduced the need to stop the line for product variability from 3 months, to 3 weeks, to 3 minutes, to less than 3 seconds. The internal factory layout, an S shape configuration, changed the sequencing of tasks, the forms of supervisor-employee interactions, and the speed and timing of interdependencies between the production operations and external suppliers of parts, delivering “just in time.”

In some cases, the interactions involve the core production system and independent suppliers serving as complementarities 3 where the competitive advantage of one is augmented by the presence of the other [ 45 ]. Early examples included Ford’s cooperation with Firestone to produce tires, or Renault’s links to Michelin to produce radial tires. Complementarities allow synergistic advantages, a contrast to additive, discrete features [ 64 ], and allow two immediate effects: knowledge spillovers at differing stages of production, including process learning impacts, and complimentary and coordinated changes in activities and programs across the value chain, such as process benchmarks for product design, scheduling, inspection, and time cycles of production. Toyota cultivates complementarity attributes but instituted a revised activity sequence, discarding production based on estimated demand forecasts, and turning finished production of cars and trucks to car lots for ultimate sale. The pull system starts with customer demands, allowing novel design using the advantages of the need for high capacity utilization of smaller actual output demands, to manufacture outputs with shorter time for product delivery.

6. JIT and Toyota’s deep supplier collaboration systems

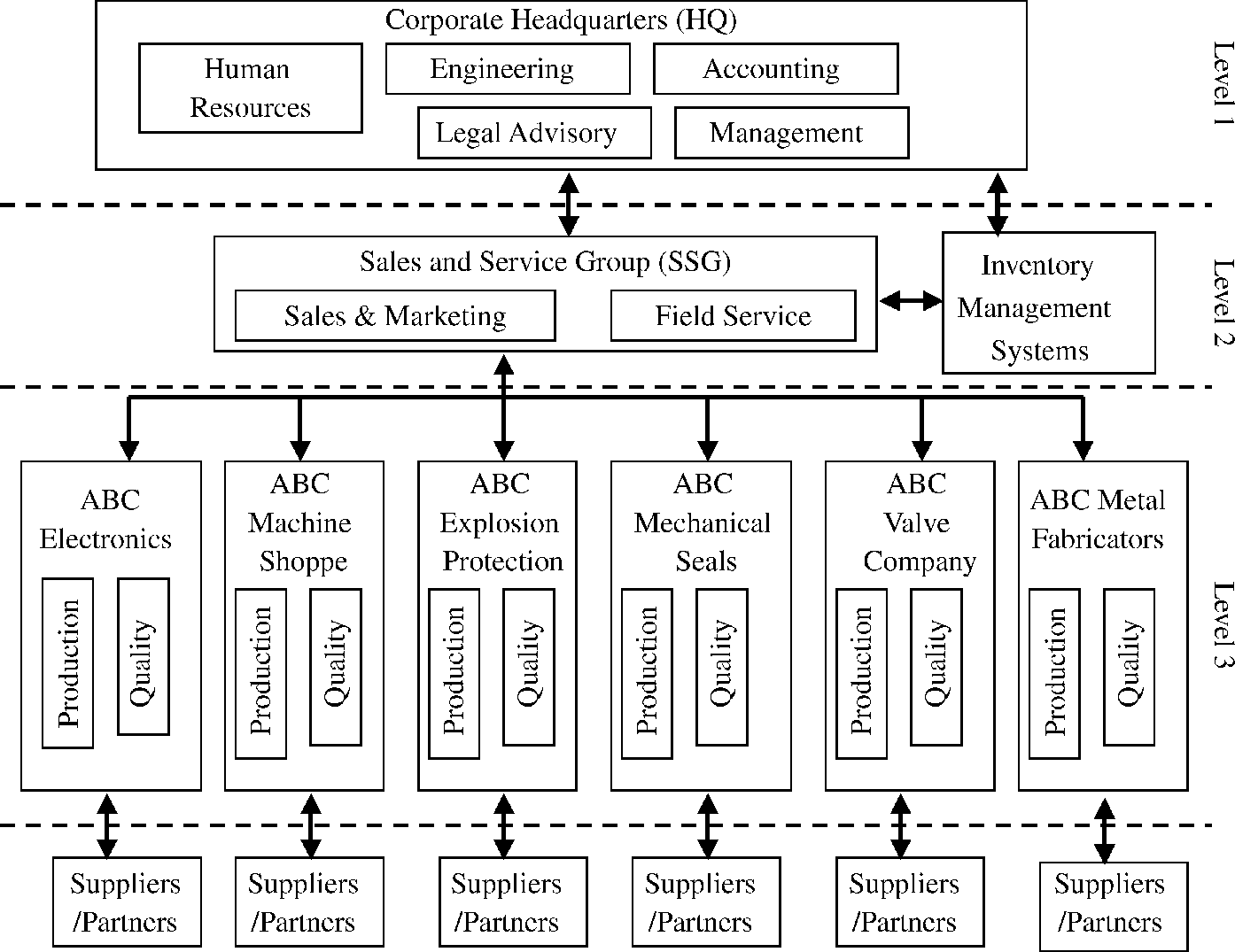

Toyota’s lean production both reconfigures the boundaries of the firm by incorporating the supply chain as an integrated, cooperative network with collective competences and capabilities across the network value chain and incorporates decision processes for learning and knowledge sharing that shifts subunit identities to a collective identity. Lean production requires these system-wide processes to address inoperability issues like buffer stocks, time delays, peak demand, or product defects. Deep collaboration across sub-units needs robust methods to design, evaluate, and verify data gathering and data feedback. Unlike economic models of transaction costs, or contractual relations, lean production emphasizes symmetrical collaboration to optimize outcome effectiveness for the total eco-system organization, not sub-optimize for only certain members, sub-units, or component firms. Toyota’s collective identity is a notable corporate example that combines both superb operational performance but also long-term, forward looking innovation through its complex ecosystem of Tier I and Tier II supplier system. As depicted in Figure 3 , Toyota aligns its supply system both domestically and overseas with knowledge systems, including standards of precision and quality, including using internal staffing and consultants to assure optimum outcomes against agreed benchmarks.

Figure 3.

Toyota’s Knowledge Diffusion and Sharing Approaches.

By replacing asymmetric contractual relations based on cost, Toyota shifts the locus of corporate risk to the total eco-system, involving Toyota at the center, the Tier I and Tier II suppliers, and their Tier I and Tier II suppliers. The lean “pull” of production control is a connectivity to calibrate inventory at each stage, starting with the final assembly and preceding to each preceding stage without delay. Unlike the push model, where the early steps of sub-assembly is sequential to subsequent stages and require buffer inventory to lesson delays, Toyota’s lean system of ‘pulling’ requires training and upgrading skills employed at different work stations, and close communications across the total supply chain system. To make this system work, economic transaction costs are discarded, and replaced by a currency of cooperation using preventive tools and benchmarks to meet high standards of reliability where Tier II firms meet rigorous standards of price, quality, and delivery. Suppliers are battle-tested, i.e., they must conform to agreed specifications and their products are accepted only after years of testing. Tier I suppliers, on the other hand, meet the exacting standards of Tier II suppliers but they form part of the design, research, and testing of new products, markets, and technological innovations. Tier II suppliers can “graduate” to being Tier I suppliers if they meet benchmark performance over time, thus demanding intense deep collaboration at Level 4 ( Figure 4 ).

Levels of Value Chain Collaboration: Toyota as Level 4.

Less coordinated systems of structure, processes, and executive decision-making inhibit eco-system operability. Three integrating systems are vital: (1) technical systems, including IT, software, and data; (2) organizational tools of coordination, like dedication teams supported by specialists and intense data sharing; and (3) collaborative executive decision processes that champion novelty, innovation, and feedback [ 65 , 66 ]. Inoperability can come from seemingly mundane tasks, like loading supplies on a truck with different invoices, manifest requirements, and delivery times. Separate and differing organizational processes inhibit deep collaboration. Inoperability arises from silo information flows and compartmentalization. Even with aspirational targets of decision-making, organizations acting alone fail to develop and improve competencies and capabilities to manage this integrated system via experiential learning, feedback, and criticism [ 67 , 68 , 69 ].

Deep collaboration needs robust methods to design, evaluate, and verify data gathering and data feedback to optimize effectiveness for the total eco-system organization, not sub-optimize for only certain members, sub-parts, or component firms [ 70 ]. Toyota’s lean production now has both a language and a vocabulary to remove task ambiguities and increase identity among workers, sub-units, and factories in the global network, but requiring a learning process to perfect clear meanings and defined protocols. Words like kanban, andon, jioda, yo-i-dan, and kijosei have precise meanings and routines, and such terms as reverse engineering, early detection, and ringi seido or consensus decision-making, simplify and codify precise protocols for shared communication. Benchmark techniques are widely used but less to evaluate past performance against competitors, but more to evaluate current performance against higher targets and aspirational stretch goals [ 71 ]. Indeed, deep collaboration at each stage requires a judicious combination of sharing ideas, new targets, real time feedback, and potential revisions. Where ambiguous signals, informal targets and past measures become explicit, and shared across the system.

Training programs—internships, formal courses, apprenticeships—build organizational capabilities and mitigates risks from operating with incomplete knowledge, inexperience, understanding operating rules and procedures. Deep collaboration illustrates the need for similar training approaches to know, understand, and apply knowledge across the entire system. Toyota gains three network advantages: positional, where individual managers and subsidiaries access tools and protocols for high performance processes and benchmarks that create learning; structural, where communication connections strengthen the effectiveness and acuity of information flows to attend to emerging problems; agility, by strengthening interactions between individuals and teams, and embedding the new benchmarks across the entire network of factories, sales offices, and supplier organizations.

7. Split identities at Toyota

By the early 1980s, Toyota, like many leading Japanese corporations such as Sony, Komatsu, Canon, Matsushita, and Hitachi, were making deep inroads in the American market via exports. The auto sector was singled out, as 500,000 American autoworkers were laid off, a new President, Ronald Reagan faced pressure from Congress to take legislative action, and firms like Ford applied to the American International Trade Commission for temporary relief, following similar action by the powerful auto union, the UAW. Further, Japan’s emphasis on direct export sales stood in contrast to American strategies of direct investment in foreign markets, often by acquisition of local companies [ 8 , 45 , 72 ] . 4 For firms like Toyota, growing high dependence on exports meant that larger total volumes (domestic + exports) strengthened their product capacity and cost position at home, including that of their supplier base. Japan’s auto exports to the US reached 6.6 million vehicles in 1981, up from a million units 10 years earlier, 566,042, accounted for almost 20% of total Japanese auto exports.

The imposition of Japan’s export restraints, formalized in June 1981, coincided a $1.5b loan guarantee to Chrysler, indefinite layoffs of over 30,000 auto workers, and sectors like steel facing declining market share. Pressed by firms like Ford for Congressional actions, MITI imposed export quotas on each Japanese company, a form of “administrative guidance” designed to accommodate political goals in each country but was in fact a “cartel” solution aimed to appease the US government [ 3 , 74 ]. The percentage breakdown for each of the five biggest exporters, calculated mainly by US exports in the previous 2 years, was as follows: Toyota (30.75), Nissan (27.15), Honda (20.75), Mazda (9.48), and Mitsubishi (6.7). The impact for each company in the brutally competitive Japanese market varied: Honda was the first to begin direct investment, opening its first plant in Ohio and then Ontario; while Toyota kept to its quota by exports but strengthened domestic operations to build up a commanding market share lead, over 50%. For the Japanese auto sector, as Summerville notes [ 74 ], “investment in local production was also a crucial way to insulate oneself from further export cutbacks, and of course to get away from the thumb of the Japanese state” (p. 395). Toyota illustrates the complexity to manage very fast growth in foreign markets, while transferring its corporate identity to a network identity of safety, quality, and value [ 43 ], even though the knowledge sharing processes that are now taken for granted at home, including quality standards of suppliers, may not exist in foreign countries [ 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 ].

The massive recall in 1999, where Toyota accepted responsibility to service over 8.5 million vehicles, the President appearing before Congress, and sundry lawsuits launched in a litigious environment against a foreign-owned firm, have been analyzed and studied 5 in the media, the automotive press, and by academic studies, with mixed conclusions. The reality, despite paying fines, accepting responsibility, apologizing to the American public, and accepting the huge financial costs of the recall, Toyota refused to play the blame game, or take easy solutions, like importing more parts from Canada or Japan, or shifting American production to Canada or Mexico. Toyota took the difficult decision, true to its identity, of fixing the core problem, raising the quality standards of its American-own parts supplier, devoting more resources to training, and accepting short-term risks to financial performance, particularly when leading automakers from Europe, Korea, and Japan were investing in the US market. The Detroit Big 3 received temporary relief, a massive bailout after bankruptcy from the US and Canadian government, and a 25% tariff on imported trucks, one of the most profitable segments for American producers. Toyota quietly responded about building a truck factory in Texas.

8. Discussion and conclusions

In a world of disruptive corporate strategy and identity offer a refined tool for alignment of stakeholders to create competitive advantage. Corporate culture focuses on the behavioral assumptions to perceive, think, and feel in problem-solving [ 81 ] within the organization, while organizational identity is a projection of that culture to external stakeholders to align both cognitive and behavioral tools for growth and innovation. Individual and sub-unit identities can lead to cleavage and discord, especially where environmental forces make knowledge and information asymmetric, so special attention and sense-making requires an adaptive alignment to improve performance ( Figure 5 ).

Organizational Strategy and Identity Linkages.

Increasing, all organizations face four separate but related challenges that impact overall performance but also survival as independent entities. Clearly, technological change imposes new challenges for internal organizational competences and capabilities, as firms scramble for mergers, takeovers, and new alliances to meet the test of size and foreign market penetration, or a retreat approach or even drift. Decision uncertainty influences the nature of internal competencies, learning barriers, and the sustainable position of existing firms. The third challenge with disruption is the growing complexity of the firm’s ecosystem, and what is the optimal scale of a firm’s future business case, based on potential changes to customer markets across multiple countries?

The fourth challenge relates to the first three but is subtler. That challenge concerns what might be called the Galapagos trap, namely designing an ecosystem that is suitable for one market that is unsuitable for global markets and allows little transfer of knowledge or engineering knowhow to other markets with a separate eco-system, including the supplier system. Recent examples include Japan’s unique wireless standards that did not apply in foreign markets systems, or American big car gas guzzlers with limited fuel mileage that did not meet foreign market regulations. Toyota’s development of hydrogen fuel powered vehicles, based on new chemical technologies, is a case in point, where existing infrastructure lacks the necessary technical requirements for even limited mass appeal. In all four of these development challenges, the competitive race is to avoid the lessons of the computer industry, where new smart phone technologies displaced existing incumbents, lowered entry barriers for new startups, and shifted the main suppliers and their location.

Such fundamental changes pose difficult questions for firms’ missions, corporate identity, and framing long term employee loyalty. As Simon [ 76 ] warned decades ago, “organizational identification…implies absorption of strategic plans into the minds of organizational members where they can have direct effect upon the entire decision-process, starting with the identification of problems…” (p. 141).

- 1. Toyota Motor Corporation. The Toyota Production System. Tokyo: Japan; 1992

- 2. Takeuchi H, Osono E, Shimizu N. The contradictions that affect Toyota’s success. Harvard Business Review. 2008;(June):96-104

- 3. McMillan CJ. The Japanese Industrial System. Berlin: De Gruyter; 1985

- 4. Spear S, Bowen HH. Decoding the DNA of the Toyota production system. Harvard Business Review. 1999; 87 :97-106

- 5. Stuart A, Whetten DA. Organizational identity. Research in Organizational Behavior. 1985; 7 :263-295

- 6. Hatch MJ, Schultz M. Organizational Identity: A Reader. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004

- 7. He H, Brown AD. Organizational identity and organizational identification: A review of the literature and suggestions for research. Group and Organization Management. 2013; 38 (1):3-35

- 8. McMillan C, Overall J. Crossing the chasm and over the abyss: Perspectives on organizational failure. Academy of Management Perspectives. 2017; 31 (4):1-17

- 9. Whetton DA. Albert and Whetton revisited, strengthening the concept of organizational identity. Journal of Management Inquiry. 2006; 15 :119-134

- 10. Rodrigues S, Child J. The development of corporate identity: A political perspective. Journal of Management Studies. 2008; 45 :885-911

- 11. Schultz M, Maguire S, Langley A, Tsoukas H. Constructing Identity in and around Organizations. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2012

- 12. Balmer JMT, Greyser SA. Managing the multiple identities of the Corporation. California Management Review. 2002; 44 (3):72-86

- 13. Kogut B. Knowledge, Options, and Institutions. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. https://www.amazon.com/s/ref=rdr_ext_aut?_encoding=UTF8&index=books&field-author=Bruce Kogut

- 14. Durkheim E. The Division of Labour in Society. New York: Free Press; 1933

- 15. Camuffo A, Wilhelm M. Complementarities and organizational (Mis)fit: A retrospective analysis of the Toyota recall crisis. Journal of Organizational Design. 2016; 5 :2-13

- 16. Simon HA. Administrative Behavior. New York: MacMillan; 1976

- 17. March JG, Simon HA. Organizations. New York: John Wiley; 1958

- 18. Katz D, Kahn RL. The Social Psychology of Organizations. New York: Wiley; 1966

- 19. Hofstede G. Culture’s Consequences. Beverley Hills, CA: Sage Publishing; 1980

- 20. Giddens A. Modernity and Self-identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1988

- 21. Vough H, Caza BB. Identity work in organizations and occupations: Definitions, theories, and pathways forward. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2018; 39 (7):889-910. https://scholar.google.ca/scholar?oi=bibs&cluster=17457274272124570525&btnI=1&hl=en

- 22. Hammack PL. Narrative and the cultural psychology of identity. Personnel and Social Psychology Review. 2008; 12 (3):222-247

- 23. Dutton JE, Dukerich JM, Harquail CV. Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1994; 39 :239-263

- 24. Alvesson M, Ashcraft KL, Thomas R. Identity matters: Reflections on the construction of identity scholarship in organization studies. Organization. 2008; 15 :5-28

- 25. Lamertz K, Pursey PM, Heugens AR, Calmet L. The configuration of organizational images among firms in the Canadian Beer Brewing Industry. Journal of Management Studies. 2005; 42 (4):817-843. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/action/doSearch?ContribAuthorStored=Lamertz%2C+Kai , https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/action/doSearch?ContribAuthorStored=Heugens%2C+Pursey+P+M+A+R , https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/action/doSearch?ContribAuthorStored=Calmet%2C+Loïc

- 26. Hirschman AO. Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms Organizations, and States. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1970

- 27. Akerlof GA, Kranton RE. Identity and the economics of organizations. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2005; 19 :9-32

- 28. Likert R. New Patterns of Management. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1961. p. 1961

- 29. Dutton JE, Dukerich JM. Keeping an eye on the mirror: The role of image andidentity in organizational adaptation. Academy of Management Journal.1991; 34 :517-554