- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 24 April 2021

Cesarean myomectomy: a case report and review of the literature

- Priyanka Garg ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0336-4750 1 , 2 &

- Romi Bansal 2

Journal of Medical Case Reports volume 15 , Article number: 193 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

5210 Accesses

7 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Routine myomectomy at the time of cesarean section has been condemned in the past due to fear of uncontrolled hemorrhage and peripartum hysterectomy. It is still a topic of debate worldwide. However, in recent years, many case studies of cesarean myomectomy have been published validating its safety without any significant complications.

Case presentation

We describe the case of a 27-year-old gravida 2 para 1 live birth 1 North Indian woman with one previous lower segment caesarean section (LSCS) at 35 weeks with labor pains and scar tenderness. Her recent ultrasound (USG) report suggested a single live intrauterine pregnancy with an intramural fibroid of 8.6 × 6.5 cm located in the left anterolateral wall of the lower uterine segment. The patient was taken up for emergency cesarean section along with successful removal of the myoma, which was bulging into the incision line, causing difficulty in closure of the uterine wound. Prophylactically, oxytocin infusion, bilateral ligation of uterine arteries, and injection vasopressin (diluted) was administered to decrease the blood loss. The patient was discharged after 7 days without any complications.

Conclusions

Routine myomectomy at the time of cesarean section is not a standard procedure and is not accepted worldwide. However, it may be considered a safe option in carefully selected cases in the hands of an experienced obstetrician with appropriate hemostatic technique. Large multicenter randomized controlled trials should be conducted to evaluate the best practice guidelines for cesarean myomectomy.

Peer Review reports

Leiomyomas are the most common benign tumors of the reproductive tract in women of childbearing age. Their exact incidence in pregnancy is hard to estimate. However, literature reports a prevalence of 2–4% [ 1 ]. The incidence is rising due to delayed childbearing and a rapid increase in the number of cesarean sections over the last few years. The majority of the patients are either asymptomatic or have mild symptoms and need conservative management only. Myomectomy during cesarean section is routinely avoided due to increased vascularity of the gravid uterus leading to massive hemorrhage, unnecessary obstetric hysterectomy, and increased perioperative morbidity and mortality. However, in modern obstetrics, with advancements in anesthesia, adequate availability of blood products, selective devascularization techniques, and a multidisciplinary approach, obstetricians are increasingly choosing to perform myomectomy during cesarean section, thus saving the patient from future morbidity due to multiple surgeries, anesthetic complications, and out-of-pocket expenditure [ 2 ]. Here, we report the case of a successful myomectomy done during an emergency cesarean section without any complications. We intend to break the traditional thumb rule of avoiding myomectomy at the time of cesarean section, and be open to the procedure after careful case selection.

A 27-year-old gravida 2 para 1 live birth 1 North Indian woman with one previous lower segment caesarean section (LSCS) presented to our outpatient department (OPD) at 35 weeks with complaints of intermittent pain in the lower abdomen that was radiating to her back for the last 5 hours. There was no associated complaint of leaking or bleeding per vaginum . Her antenatal period was uneventful. However, she was diagnosed as having a fibroid on the left side of the uterus but reported no complications that could be attributed to it. Her general and systemic examination was unremarkable. All the antenatal investigations were normal. Her recent ultrasound (USG) report suggested a single live intrauterine pregnancy with an intramural fibroid measuring 8.6 × 6.5 cm located in the left anterolateral wall of the lower uterine segment.

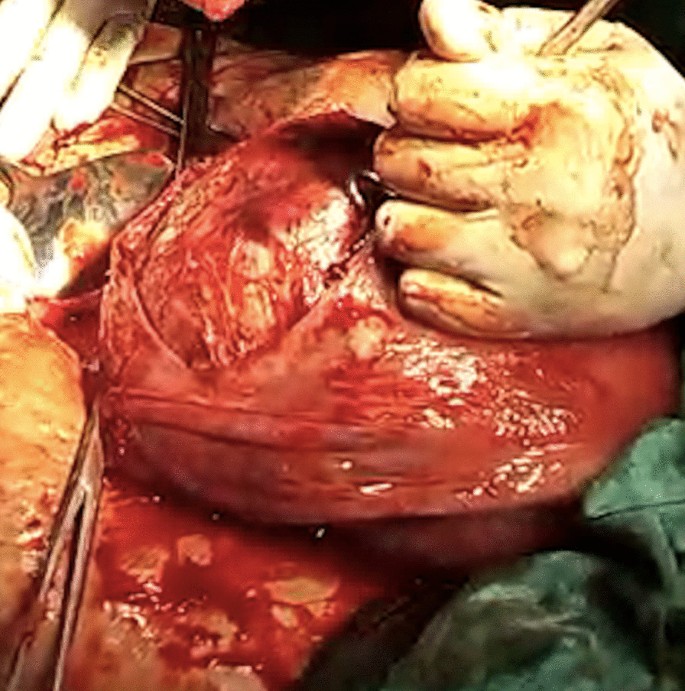

On admission, her heart rate was 96 beats per minute, blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg, and mild pallor was present. Abdominal examination revealed a term size uterus with longitudinal lie. Mild uterine contractions were present with positive scar tenderness. On auscultation, fetal heart rate was 142 beats/minute. Vaginal examination depicted a 2 cm dilated cervix, which was 20–30% effaced, presenting part at −3 station with intact membranes. She was taken up for emergency LSCS given previous cesarean section with preterm labor and scar tenderness. Her preoperative hemoglobin was 12.1 gm%, hematocrit was 34.5%, and blood group was O positive. Adequate blood products were arranged and informed written consent was obtained from the patient and her relatives after explaining to them about the risk of excessive bleeding, need for blood transfusion, and peripartum hysterectomy. During surgery, the abdomen was opened by an infra-umbilical vertical incision for adequate access. There was a single large intramural fibroid occupying most of the lower uterine segment. The previous scar was intact but thinned out, possibly because of the stretching effect of the fibroid. A lower segment transverse incision was made below the inferior margin of the fibroid, and a 2.54 kg female baby was delivered, with an APGAR score of 9 at 1 minute. As the fibroid was bulging into the incision line and causing difficulty in closure of the uterine wound, the decision of myomectomy was taken (Fig. 1 ). Prophylactically, oxytocin infusion, bilateral ligation of uterine arteries, and injection of vasopressin (diluted) was injected to decrease the blood loss. The fibroid was then enucleated and the myoma bed closed with delayed absorbable sutures followed by closure of the uterine wound. A complete hemostasis was achieved. The total duration of the surgery was approximately 50 minutes and the amount of blood lost around 1100 mL, which is almost comparable to other cesarean sections. Broad-spectrum antibiotics and analgesics were administered in the postoperative period. Her post-surgery hemoglobin was 11.4 gm% and hematocrit was 33%, thus not requiring any blood transfusion. The patient was discharged on the seventh postoperative day with a normal involuting uterus. On follow-up at 6 weeks, the uterus was completely involuted, and repeat USG did not show any fibroid. On further follow-up to 6 months, she was asymptomatic and had an uneventful course.

Intraoperative image depicting the fibroid bulging into the incision line

We report a case of successful myomectomy performed at the time of an emergency cesarean section, with an intent to disintegrate the long-established belief of avoiding it due to fear of complications. Pregnancy with fibroid is a high-risk situation. Although the majority of such cases are asymptomatic or have mild symptoms, 10–40% of cases can present with antenatal complications in the form of pregnancy loss, degenerative changes, malpresentation, abruption placenta, preterm labor, dysfunctional labor or uterine inertia, and increased chances of operative delivery, thus increasing maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality [ 3 ]. Treatment is usually conservative during the antenatal period in the form of bed rest, adequate hydration, and analgesics. Myomectomy is rarely required in the case of intractable abdominal pain due to twisting of pedunculated sub-serosal fibroid, red degeneration unresponsive to conservative treatment, or massively enlarged myoma causing abdominal discomfort to the patient [ 1 ]. In a recent study, a successful myomectomy was performed during the first trimester at 11 weeks for a large myoma of 14 cm that was a cause of severe discomfort to the patient [ 4 ]. The patient continued with pregnancy to term and delivered a healthy baby. Another uneventful myomectomy was performed in the second trimester by Bhatla et al . without any adverse impact on pregnancy [ 5 ]. Myomectomy during cesarean section is still a topic of debate in the modern era. Until the last decade, it was considered a dreadful surgery except for pedunculated sub-serosal fibroids. However, many researches have concluded that the procedure is not dangerous and does not lead to complications in the hands of an experienced obstetrician [ 6 ]. Kwawukume performed cesarean myomectomies on 12 patients and reported that enucleation was much easier in pregnancy due to increased softness of the tissue [ 7 ]. A retrospective case–control study, comparing 40 women with fibroids who underwent cesarean myomectomy with 80 women with fibroids forming the control group who underwent cesarean section alone, reported no significant difference in the incidence of hemorrhage between the two groups (12.5% and 11.3%, respectively) [ 8 ]. Similar findings were reported in another study, with no significant differences in hemoglobin levels, incidence of blood transfusions, or postoperative pyrexia. However, not all myomas need to be removed, but only those causing difficulty in delivery of the fetus or wound closure and sub-serosal fibroids. In our case, myomectomy was inevitable as the myoma was in the incision line, making wound closure impossible. Every possible effort should be made to reduce the blood loss. Bilateral ligation of uterine arteries immediately after delivery of the fetus significantly reduces both intraoperative and postoperative blood loss and risk of peripartum hysterectomy [ 9 ]. It also reduces the recurrence of myomas and minimizes the need for future surgery, with no apparent effect on fertility [ 10 ]. This was a key step in our case which prevented the dreaded complications. Also, the postpartum uterus is better adapted physiologically to control bleeding than in any other phase of a woman’s lifetime. The patient and relatives should be properly counseled and informed that removal of myoma is possible, and a final decision can be taken at the time of cesarean based upon the size, number, and location of the fibroid.

The idea of performing myomectomy at the time of cesarean section appears winsome in a low-resource country like India, where fibroids are common. If performed safely, it can avoid the additional morbidity of a future surgery, thus justifying the cost-effectiveness of the procedure. However, the importance of an expert obstetrician, equipped center with adequate manpower and blood products, and careful case selection cannot be ignored.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ardovino M, Ardovino I, Castaldi MA, Monteverde A, Colacurci N, Cobellis L. Laparoscopic myomectomy of a subserous pedunculated fibroid at 14 weeks of pregnancy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:2–6.

Article Google Scholar

Kathpalia SK, Arora D, Vasudeva S, Singh S. Myomectomy at cesarean section: a safe option. Med J Armed Forces India. 2016;72:S161–3.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Ma PC, Juan YC, De WI, Chen CH, Liu WM, Jeng CJ. A huge leiomyoma subjected to a myomectomy during a cesarean section. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;49(2):220–2.

Leach K, Khatain L, Tocce K. First trimester myomectomy as an alternative to termination of pregnancy in a woman with a symptomatic uterine leiomyoma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:2–5.

Bhatla N, Dash BB, Kriplani A, Agarwal N. Myomectomy during pregnancy: a feasible option. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2009;35(1):173–5.

Guler AE, Guler ZÇD, Kinci MF, Mungan MT. Myomectomy during cesarean section: why do we abstain from? J Obstet Gynecol India. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-019-01303-6 .

Kwawukume E. Myomectomy during cesarean section. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2002;76(2):183–4.

Kaymak O, Ustunyurt E, Okyay RE, Kalyoncu S, Mollamahmutoglu L. Myomectomy during cesarean section. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2005;89(2):90–3.

Murmu S. successful myomectomy during caesarean section: a case report. Int J Contemp Med Res [IJCMR]. 2019;6(9):44–5.

Liu WM, Wang PH, Tang WL, Te WI, Tzeng CR. Uterine artery ligation for treatment of pregnant women with uterine leiomyomas who are undergoing cesarean section. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(2):423–8.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Obstetric and Gynecology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bathinda, 151505, India

Priyanka Garg

Department of Obstetric and Gynecology, Adesh institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Bathinda, Punjab, India

Priyanka Garg & Romi Bansal

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

PG and RB treated the patient. PG wrote the manuscript. RB revised and edited the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Priyanka Garg .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study did not conduct any experiments on animals or humans. The patient consented to the use of her personal data for the purpose of this case report.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The authors have no association with financial or nonfinancial organizations.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Garg, P., Bansal, R. Cesarean myomectomy: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports 15 , 193 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-02785-7

Download citation

Received : 29 January 2021

Accepted : 12 March 2021

Published : 24 April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-02785-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Postpartum hemorrhage

Journal of Medical Case Reports

ISSN: 1752-1947

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Decreased Length of Stay for C-section Case Study

Executive Summary

Local problem.

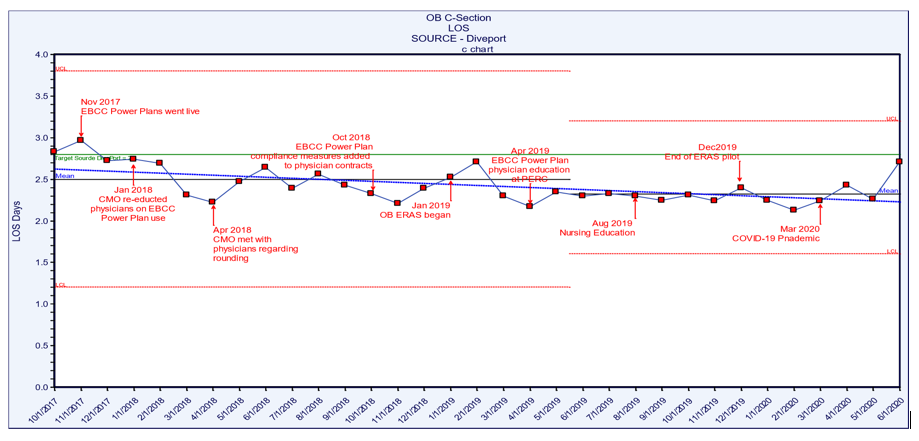

To decrease the variability in care delivery to improve the standard of care and the outcomes of the patients undergoing a cesarean section (C-section) procedure. Baptist Health South Florida’s (BHSF) Homestead Hospital implemented electronic order sets (PowerPlans ™) in 2017 for the patient population, and over time has improved the length of stay (LOS) and maintained zero maternal deaths and zero venous thromboembolisms (VTEs). Homestead also initiated an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pilot for the cesarean section population. The goal of the ERAS c-Section pilot was to serve as an adjunct to current practices geared to deliver a multidisciplinary approach to care with a defined multimodal perioperative care pathway designed to reduce the stress response to surgery and accelerate the patient’s recovery. This encompassed people, process and technology as change management impacted the way Homestead Hospital delivered care along with the build and design of the electronic healthcare record (EHR) requirements. The ERAS pilot will be discussed in more detail under the Clinical Transformation section as an example of pending development and redesign. Analytics measuring the utilization of the PowerPlans supported the measurement of adherence to the standard of care compliance and improved outcomes with a decrease in LOS. The overall LOS for the patient population with the implementation of the PowerPlan decreased from 3.0 days in FY 2017 to 2.30 days in 2020 pre-COVID-19. There is a slight increase noted in LOS in Q1 2020.

Key Stakeholders

Physicians, nursing, pharmacy, lactation team, discharge planning, informatics and patients/family.

EHR data , clinical decision support alerts (e.g., allergies, sepsis, VTE prevention and fetal demise), PowerPlans for bundle compliance, device integration for vital signs and fetal monitoring, bedside specimen collection and scanning, human milk and formula management and analytics for process and outcomes measurement.

People and Process

Physician and staff buy-in, patient counseling, education and commitment pre-op and post-op; ongoing care team education and commitment to care redesign; neonatal bonding, comfort, feeding, safety and discharge follow-up plan.

Lessons Learned

- Buy-in is key for both the care team and the patient and family

- Education of the PowerPlans and ERAS Pathway is a huge key to success

- Sharing analytics to high-light improvements will help keep the process successful

- The build and design of the EHR tools to support the workflow will assist with compliance

- Neonatal components including safety and comfort will help decrease stress of the mother and support a reduced stress response

Define the Clinical Problem and Pre-Implementation Performance

Childbirth is one of the leading causes of hospital admission in the United States and there is documented evidence of variation in C-section rates, costs and outcomes due to variation in care delivery models. BHSF partnered with Navigant on the T2020 initiative which includes redesigning care for select diagnosis related groups. Navigant and the organization decided upon a structure of an OB/GYN Steering Committee as well as a design team. Both teams included representation from the facilities that provide obstetrical care throughout the health system.

The Steering Committee elected to focus on the cesarean section population to improve overall outcomes, including decreased LOS and bundle compliance. The design team collaborated on creating clinical specifications to ensure every obstetric patient get the same care, every time. Initiatives included a decrease in the LOS and overall improved standardization of care. This case study will focus on the implementation of the PowerPlan and compliance in the utilization.

Perinatal Services also participated in the ERAS pilot for elective C-section patients, which decreased the average LOS, reduced the use of opioids for pain among patients and an improved the infection rate. LOS for ERAS patients as compared to non-ERAS was 1.98 vs. 2.29 for the study period. Non-Opioid use in ERAS patients was 80% and use of non-opioids in non-ERAS patients was 37.74%. The surgical infection rate for the ERAS patients was 0% and non-ERAS was as high as 6.25%. Pain control was also 17% better for the ERAS patients. These indicators show evidence that support the improvements made in the pilot study for the cesarean section ERAS patients and will be the subject of the next phase of work.

The overall LOS for the C-section population with improved bundle compliance decreased from 3.0 days in FY 2017 to 2.30 days in FY 2019 and prior to COVID-19 in Q1 2020. Perinatal Care Quality Measures also include standardization practices such as prophylactic antibiotics, VTE prevention and pain control.

The numerators in this case study are the clinical practice being measured for compliance (PowerPlans) and the LOS for the population. The denominator is the patient population which meets the Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Groups (MS-DRG) definition for C-section cases. Exclusions include hospice, rehab and expired patients. The organization follows the guidelines and recommendations of The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecology (ACOG), CMS, MS-DRG and benchmarks against Premier. Targeted performance (Premier benchmark) is cesarean section LOS of 2.81, Premier bundle compliance of 80% and zero serious safety evens.

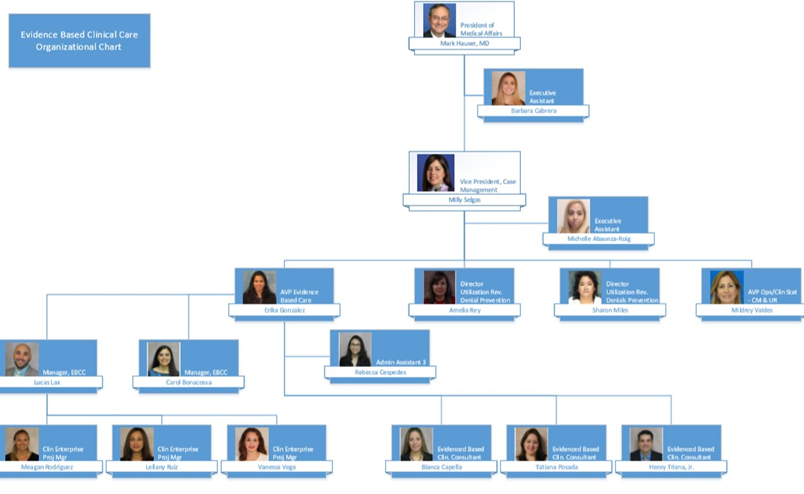

Design and Implementation Model Practices and Governance

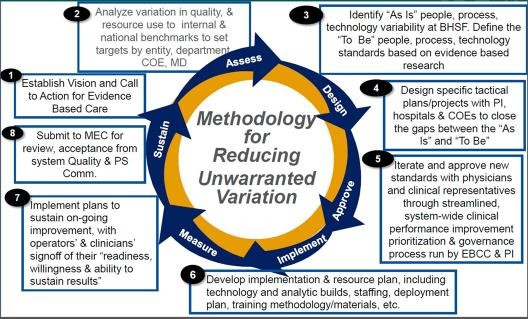

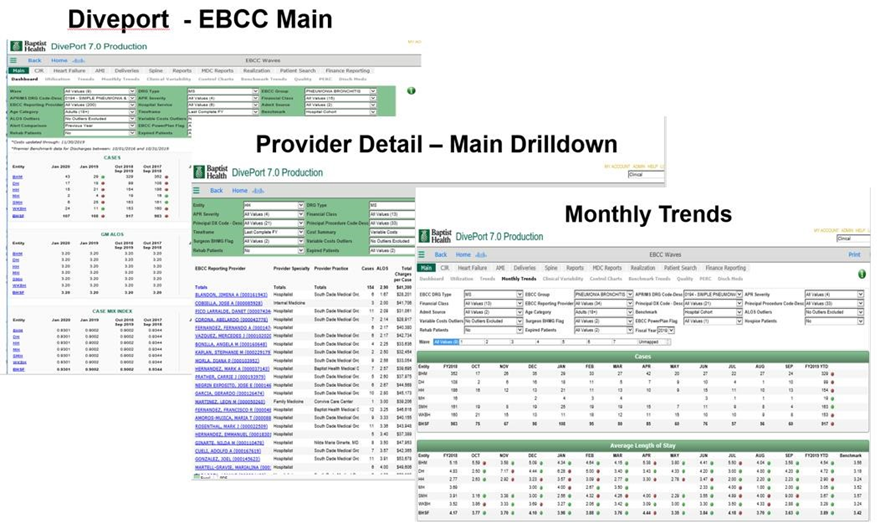

BHSF’s evidence-based clinical care (EBCC) initiative is a strategic system-wide standardization effort to reduce variation and unnecessary costs while focusing on evidence-based, quality care. The process is driven by key stakeholders and is supported by real-time, statistically supported benchmarked data. The charter was signed in 2016 and provides the foundation for a methodical approach to improve patient outcomes (Figure 1).

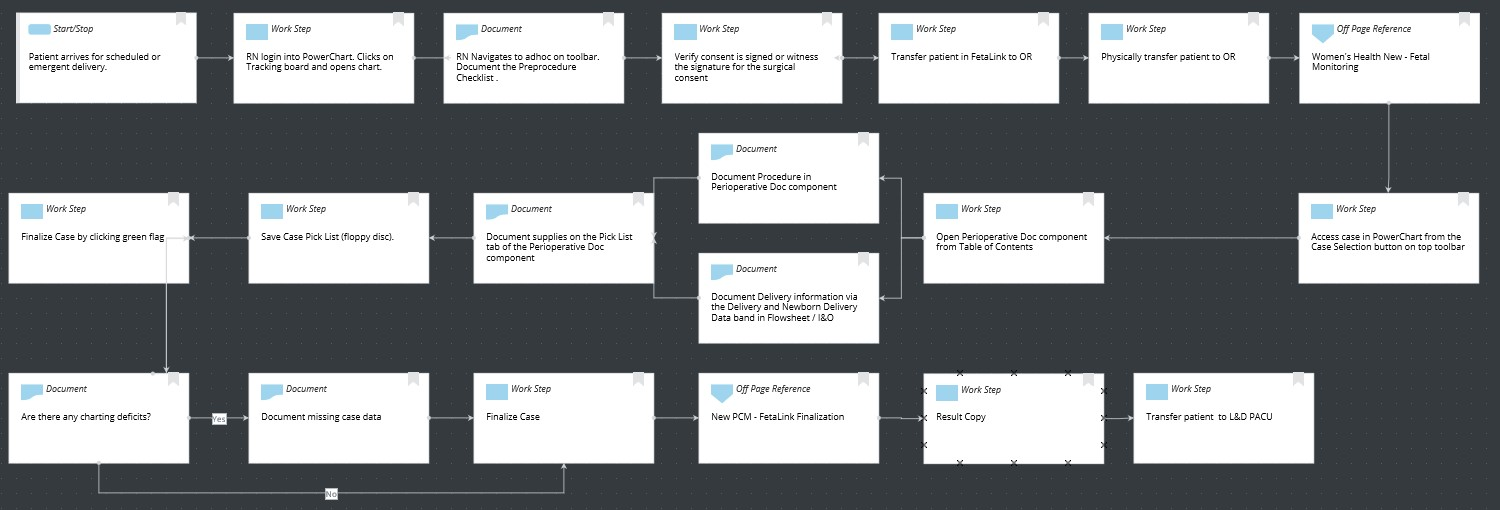

The methodology begins with a call to action to for an evidenced based care assessment of current and future state, design plan, team approval, development of an implementation plan, measurement and sustainment plans (Figure 2).

Each specific project is supported by a sub-group who are experts in on the focus topic. The Service Line Collaborative includes:

- Cardiac and Vascular

- Critical Care

- Emergency Department

- Gastrointestinal

- Infectious Disease

- Neonatology

- Neuroscience

- Orthopedics

- Surgery/PEI/ERAS/NSQIP

The organization has partnered with Navigant on the T2020 initiative which includes redesigning care for select diagnosis related groups. They decided upon a structure of an OB/GYN Steering Committee as well as a design team. Both steering and design teams included member representation from the facilities that provide obstetrical care throughout the system. The steering committee elected to focus on the primary patient population having the largest impact in reducing the overall C-section rate at BHSF. The design team collaborated on creating clinical specifications to ensure obstetric patients get the same care every patient, every time. While the work is still underway to decrease the overall cesarean section rate, the team has successfully decreased the overall LOS for the patient population and instituted a pilot for the utilization of Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS).

Technologies include EHR data, CDS–alerts such as allergies, sepsis and fetal demise, PowerPlans for bundle compliance, device integration for vital signs and fetal monitoring, bedside specimen collection and scanning, human milk and formula management and analytics for process and outcomes measurement. The PowerPlans were rolled out in 2017 and followed the recommendations from ACOG.

Education was completed via lunch and learns with classroom time, on-line formats on the EBCC website via the intranet and on the Baptist Health South Florida website which is available in the public domain. PowerPlan education is a consistent part of physician education and CME education is available with every MS-DRG or pathway as it rolls out. The education for the ERAS C-section pilot began in December 2018 and the first ERAS patient plan of care was started in January 2019. Other facilities along with BHSF followed the piloted plan of care and additional rollouts are expected. As a recommendation of The Joint Commission, the organization also will begin SIM training for maternal hemorrhage and hypertensive crisis.

The vaginal and C-section delivery steering committee meets monthly and consists of representatives from the EBCC, physicians (CMO), nursing leadership, L&D, HIT, AVP neonatal services, perinatal services and clinical education.

Clinical Transformation enabled through Information and Technology

In November 2017, BHSF implemented the PowerPlans to decrease variation in the care of the C-section patient population. Three key areas of focus for decreasing the LOS in the cesarean section population for Homestead Hospital include the prevention of infection, the prevention of deep vein thrombosis and adequate pain control. Evidence based care practices support the implementation of these key elements as part of the standardized process of care to decrease the overall LOS. In addition to the PowerPlans to minimize the variation in care delivery order sets, the team also focused on education of the PowerPlans early rounding to assess the day before expected discharge and accountability, and in January of 2019, Homestead Hospital initiated a pilot for ERAS in a subset of cesarean section patients. The change in care delivery regarding ERAS and those outcomes will drive the next phase of care delivery and expand to a broader base. Once COVID-19 initiatives begin to fall into place, resources can shift back to these types of projects.

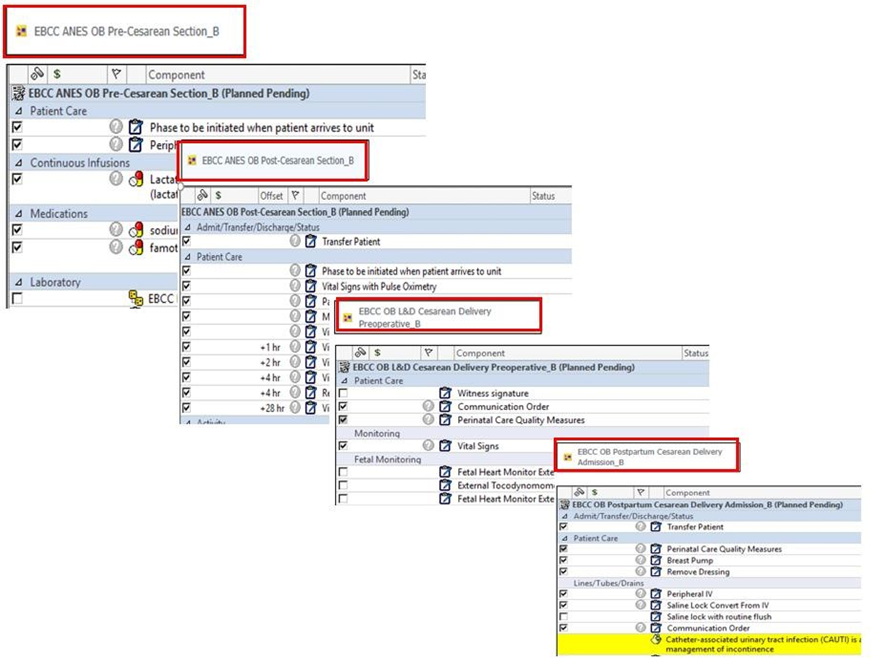

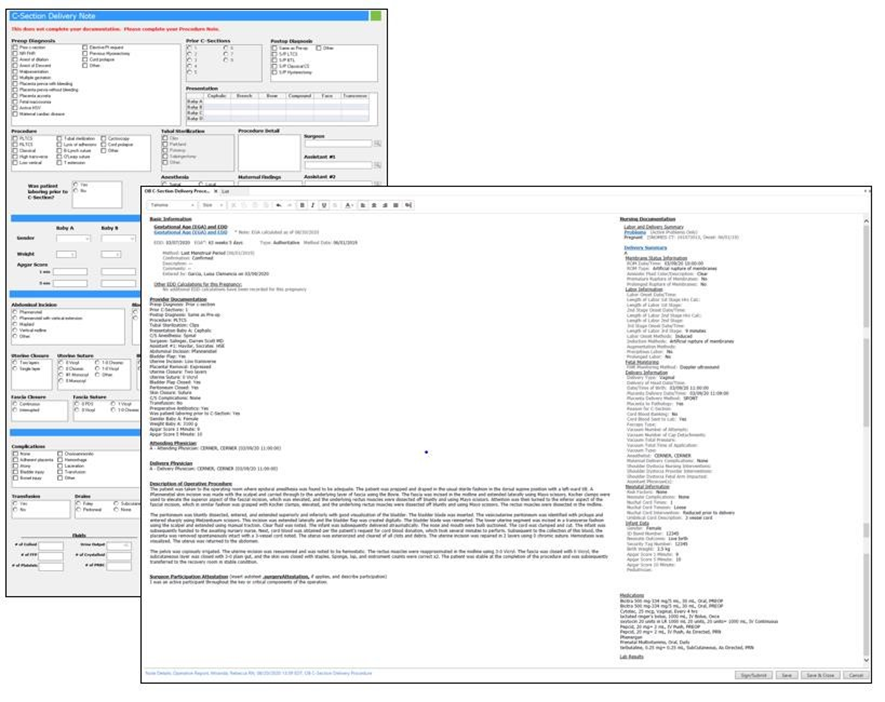

PowerPlans that currently exist for C-section include (Figure 3):

- EBCC anesthesia pre-cesarean

- EBCC anesthesia post-cesarean

- EBCC OB L&D cesarean delivery pre-operative

- EBCC OB postpartum cesarean delivery admission

PowerForms™ are used by providers to document the data of the cesarean section delivery. This is extractable data and is pulled into the provider’s note which improves the communication of care for the care team (figure 4).

Integration remains seamless, as while in the OR patients are associated to the anesthesia vital sign monitors and vital signs interface into the surgical anesthesia module. All documentation takes place in the anesthesia module and once saved creates a document which is visible within the EHR. All medications and fluids administered while in the OR also display in the patient’s eMAR (Figure 5).

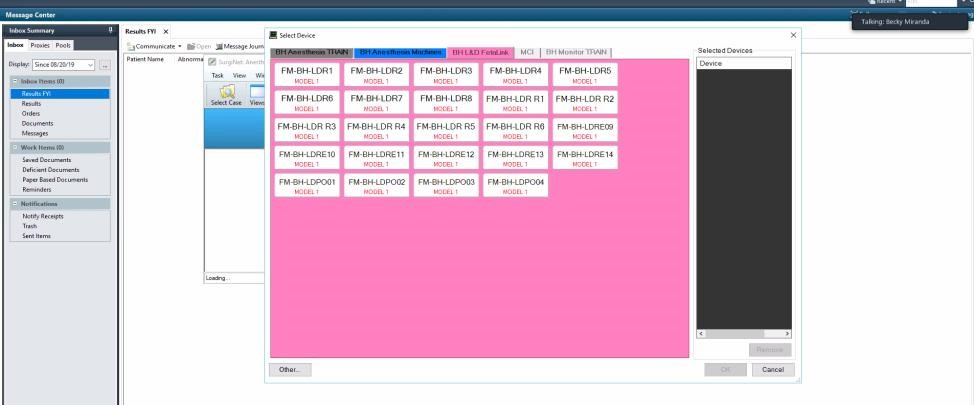

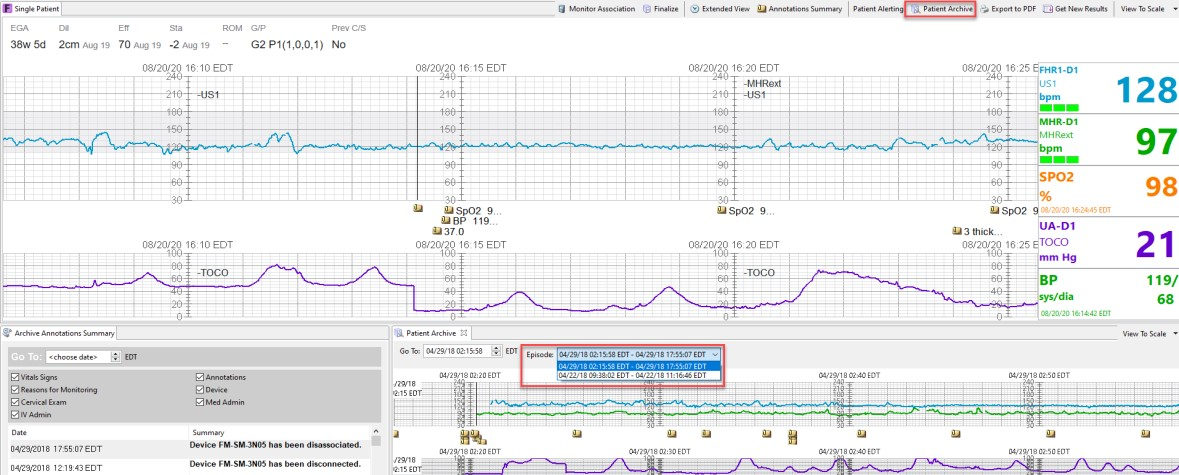

Other safety aspects include the integration with fetal monitoring. Patients are associated to fetal monitors using the Fetalink™ application. Maternal vital signs interface into PowerChart IView™ in addition to all annotations documented within the Fetalink application. Once the patient is in Post-Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU) the patient is then associated to the bedside vital sign monitors using the associate device function in IView™ where vital signs are also interfaced. Maternal previous C-section history status displays within the Fetalink application in addition to gravida and para counts. Providers are also able to view fetal strips remotely using the Fetalink mobile app, Fetalink+. Any previously saved fetal strips archived throughout patient's pregnancy and can be viewed straight from the Fetalink application as well as within the Women's Health Overview component (Figure 6).

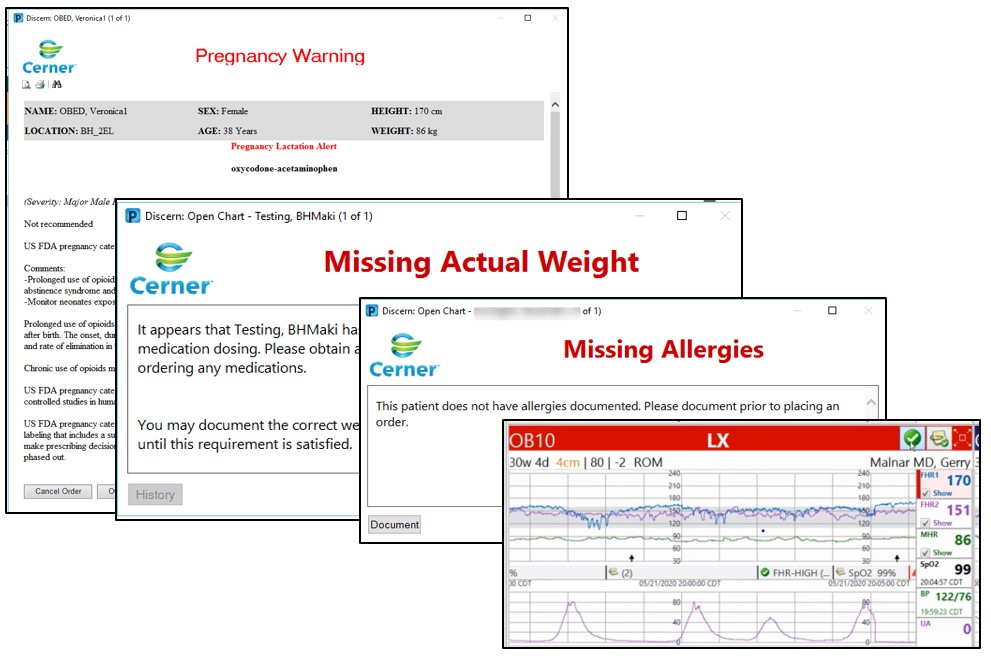

Alerts are visible on monitors, dashboards and within the EHR. CDS alerts such as sepsis with the St. John’s sepsis algorithm, allergies, contraindicated medications, weights and even fetal demise are examples of the alerts firing in real-time to keep mother and baby safe (Figure 7).

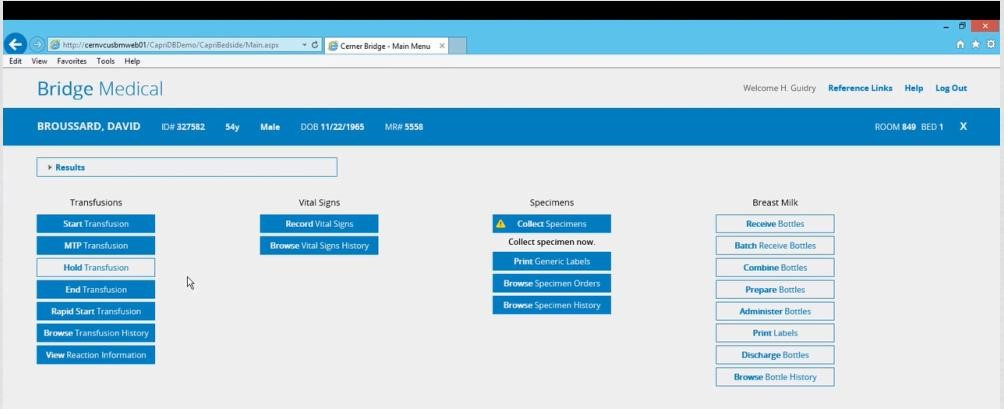

Rounding out the technologies is the capability for bedside scanning for blood, human milk and specimen collection (Figure 8).

People, processes and technology are all important factors in maintaining the safest level of care in the maternal health space. There are many moving pieces and parts, so a fully integrated EHR system increases the ease of use, adoption and standardization of care. The use of evidence based clinical care, tracked with near-real-time analytics helps to ensure improved outcomes such as decreased LOS and decreased safety events such as VTEs and maternal mortalities.

Workflows are mapped out by the interdisciplinary teams and changes are addressed as needed. Clinical decisions and updates to the evidence follow the charter for the EBCC (Figure 9).

Improving Adherence to the Standard of Care

Homestead Hospital, as part of the BHSF care initiatives instituted Power Plans™ to drive the utilization of C-section care bundles to decrease variation of care delivery and improve outcomes for the patient population. Targeting LOS was one of the focus areas with most documented resources support the average hospital LOS post cesarean section to be 2– 4 days. The standardized approach for the PowerPlan rollout, the established educational process and the existing commitment to standardized care via the EBCC structure led to the success of the rollout from the beginning.

The numerator in their care bundle utilization is the clinical practice being measured for compliance (PowerPlan utilization) and the patient population is the denominator which meets the MS-DRG definition for cesarean section cases. BHSF and Homestead Hospital follow the guidelines and recommendations of ACOG, CMS, MS-DRG and benchmarks against Premier. Targeted performance LOS of 2.30 days and bundle compliance of 80% (Figure 10).

Improving Patient Outcomes

The overall LOS for the C-section population with the implementation of the PowerPlan decreased from 3.0 days in FY 2017 to 2.30 days in 2020 pre-COVID-19. The Premier benchmark is 2.81 days. There is a slight increase noted in LOS in Q1 2020. There also were no reported VTEs or maternal deaths within the population (Figure 11).

Of note is also the work done for the C-section ERAS pilot. This work began in January of 2019 and concluded in August of 2019 with a total of 30 patients. The outcomes for those patients included: LOS for ERAS patients as compared to non-ERAS was 1.98 vs. 2.29 for the study period. Non-Opioid use in ERAS patients was 80% and use of non-opioids in non-ERAS patients was 37.74%. The surgical infection rate for the ERAS patients was 0% and for the non-ERAS was as high as 6.25%. Pain control was also 17% better for the ERAS patients. These indicators support the evidence by showing improvements in the ERAS patients in the study. Additional utilization and process redesign will continue with ERAS projects once the impact of COVID-19 stabilizes for the organization.

Accountability and Driving Resilient Care Redesign

Creating a strong governance, incorporating evidence based clinical care and having access to a strong analytic system are all key factors in improving clinical outcomes. The data must be easily captured, readily available, meaningful to key stakeholders and the quality of the data must be trusted. BSFH has created an analytics system that is both successful and sustainable.

The EBCC is the governing body that drives the focus on reducing unnecessary cost and clinical variation through the implementation of evidence-based clinical standards integration, with real-time availability of clinical information and analytics. EBCC monitoring data is housed in DivePort 7.0 (Figure 12).

The implementation of the cesarean section ERAS project is a great example of how data was leveraged to trigger care and process redesign. An ERAS program consists of a multidisciplinary approach to care with a defined multimodal perioperative care pathway designed to reduce the stress response to surgery and accelerate the patient’s recovery. Successful implementation has been shown to decrease variability between patients, resulting in earlier return of gastrointestinal function and reductions in hospital length of stay, complications and total cost.

The goal of the Homestead Hospital ERAS pilot was to have 30 patients in the evaluation. This pilot study was started in January 2019 and completed August 30, 2019, with a total of 30 patients. The outcomes included a reduction in LOS, decreased utilization of opioids with an increased pain management satisfaction score and a zero surgical site infection rate, The success of the C-section ERAS pilot has led to care redesign decisions for other surgical populations. Post COVID-19 turn-around, these initiatives will be implemented on a broader scale.

The views and opinions expressed in this content or by commenters are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of HIMSS or its affiliates.

HIMSS Davies Awards

The HIMSS Davies Award showcases the thoughtful application of health information and technology to substantially improve clinical care delivery, patient outcomes and population health.

Begin Your Path to a Davies Award

Breastfeeding rate in the first hour of life according to type of delivery and year of occurrence. CS = cesarean sections, VB = vaginal birth

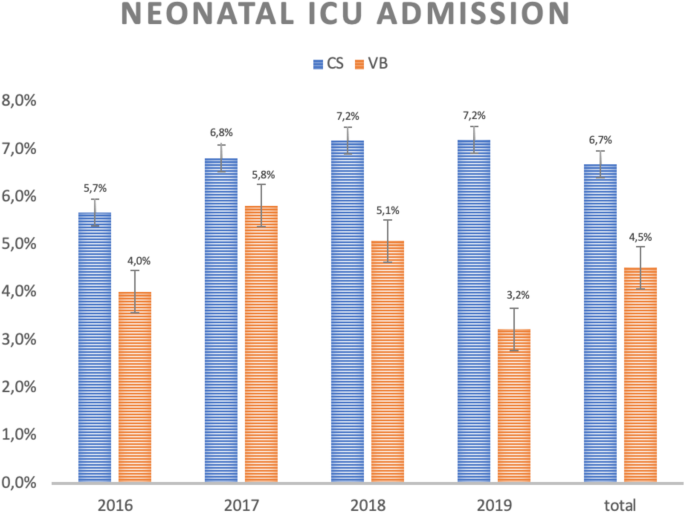

Regarding the NICU admission rate, it is noticed that neonates born by C-section are more likely to need this type of support than those born by vaginal delivery (6.7% vs 4.5%, p = 0.0078, as shown in Fig. 2 ).

Neonatal ICU admission rate according to type of delivery and year of birth. CS = cesarean sections, VB = vaginal birth

The quantitative analysis of NICU admissions in C-sections also reveals that in less than 5% of cases the cesarean was due to an emergency related to intrapartum fetal distress, so this condition seems not to contribute to the final result.

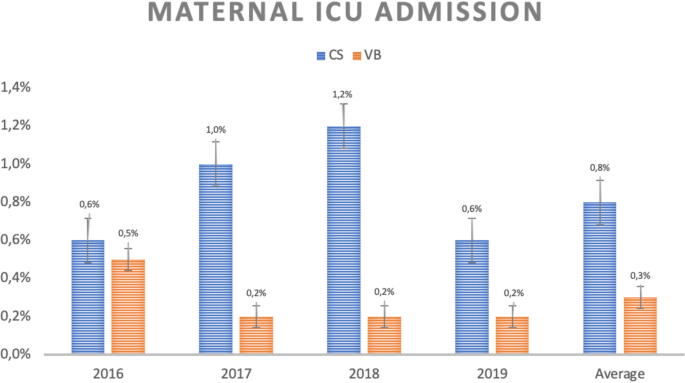

As with their babies, low-risk parturient who underwent C-sections had higher admission rates to the ICU than those who underwent vaginal delivery (0,8% vs 0,3%, p = 0.001), as shown in Fig. 3 .

Maternal ICU admission rate according to type of delivery and year of occurrence. CS = C-sections, VB = vaginal birth

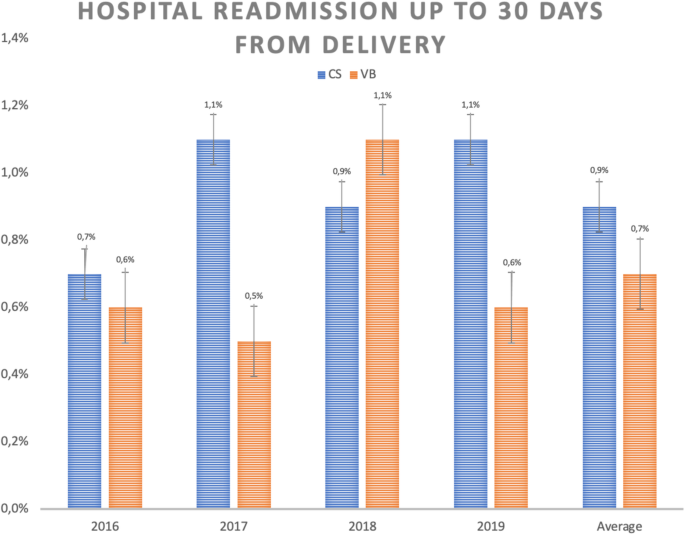

The rates of hospital readmission within 30 days from delivery are also higher in those patients submitted to C-sections than to vaginal delivery, although without statistical significance (Fig. 4 ).

Hospital readmission rate up to 30 days from delivery according to type of delivery and year of occurrence. CS = C-sections, VB = vaginal birth

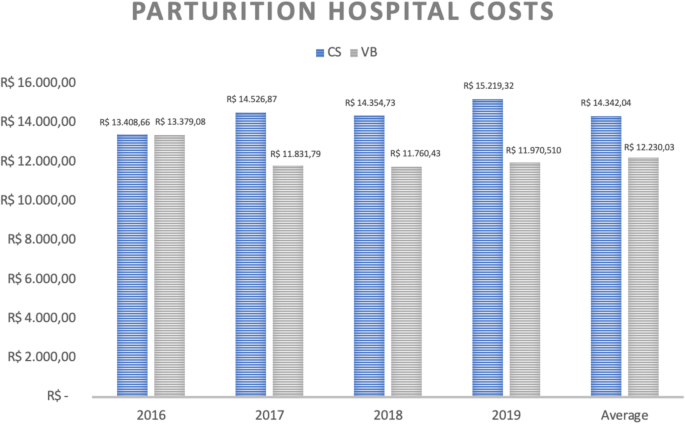

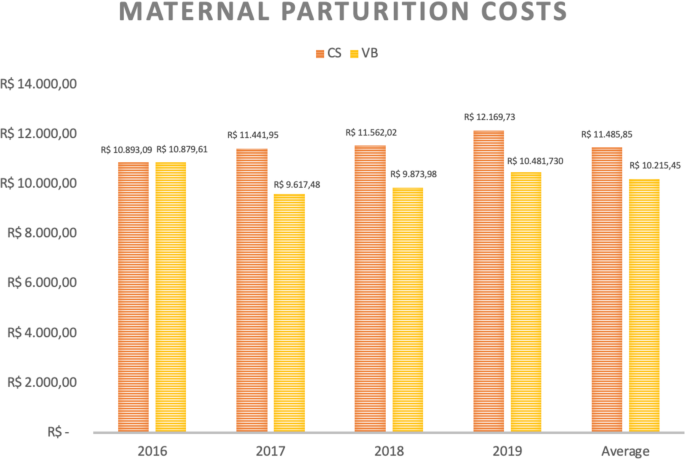

Finally, considering the average costs (calculated in Brazilian Reais – R$) of hospital stay for mother-baby binomial in low-risk pregnancies, it can be noted that cesarean deliveries cost R$14,0342.04 while vaginal deliveries cost R$12,230.03 (Fig. 5 ).

Average of parturition costs (in real) of hospitalization of the parturient-newborn binomial according to type of delivery and year of occurrence. CS = C-section, VB = Vaginal Birth

When analyzing maternal and neonatal hospital costs separately, we observed that C-sections present higher expenses for both settings, as demonstrated in Figs. 6 and 7 .

Average costs (in real) of maternal hospitalization for delivery according to type of delivery and year of occurrence. CS = C-section, VB = Vaginal birth

Average costs (in real) of hospitalization of the newborn due to delivery according to type of delivery and year of occurrence. CS = C-sections, VB = Vaginal birth

Vaginal births have lower hospital costs than cesarean sections in low-risk pregnancies. Although C-section has been related to worse results [ 11 ], this study shows which kind of results are better in vaginal delivery, and includes only low risk pregnancies, in which C-sections should be less frequent.

The mothers’ results are better in vaginal birth considering ICU admission rates. The neonatal results are also more favorable in vaginal birth especially considering NICU admission and breastfeeding in the first hour after delivery. This study showed that vaginal births are associated with better healthcare value delivery.

Despite the absence of statistical significance, the maternal rates of hospital readmission within 30 days from delivery were higher in those patients undergoing C-sections than vaginal deliveries. This finding does not allow us to conclude that this is a worse clinical outcome, but it is still contributing for the analysis of medical expenses with C-sections.

Data analysis shows homogeneity between groups and this allows more substantial conclusions. The first item that draws attention is the comparison between the costs of cesarean and vaginal deliveries. Considering the overall hospital costs per patient (mother-baby binomial), cesarean deliveries are almost 15% more expensive than vaginal deliveries in low-risk pregnancies (R$14,0342.04 versus R$12,230.03). As the results showed, the C-sections higher costs must be related to the higher rate of maternal and neonatal ICU admission. Besides that, they may be related to the team needed to provide assistance for a C-section and increased use of medications in this kind of delivery.

Considering a scenario where C-section rates would represent 20% of cases for low risk pregnancies, and therefore still exceeding the 15–18% described as ideal and safe in the literature, the savings in the analyzed period would reach almost R$7million [ 7 ].

To imagine that such a rate is unattainable shows pessimism since the group studied was comprised exclusively by singleton pregnancies of low risk, with cephalic presentation and without previous C-section. In the available literature, low and high-risk pregnancies appear in the same universe of analysis. However, it is precisely the elective C-sections in low-risk groups that seem to promote the highest rate of preventable hospitalization in the NICU. Considering low risk as singleton pregnancies at term with cephalic presentation without previous C-section (Robson groups 1 to 4), which represents around 80% of births in the world, probably the action on these groups should translate in value results: lower costs and better outcomes [ 27 ].

There are already several attempts to reduce the number of caesareans worldwide, especially in Brazil, where these rates are incredibly high [ 28 , 29 ].

The total cost of hospitalization for cesarean delivery is more expensive due to higher maternal and neonatal costs. Literature has shown that newborns of elective cesareans are more likely to have respiratory distress compared with those whose mothers went through labor [ 30 ]. Considering that such discomfort is the main cause of hospitalization in the NICU, greater use of this expensive resource in babies born by C- section was already expected [ 31 ]. Therefore, it is not surprising that there is a difference of almost 30% between hospital costs related to newborns undergoing cesarean delivery and those of vaginal delivery. Besides that, while only 4.5% of the babies born by vaginal delivery were admitted to NICU in this series, more than 6.7% of those born by C-section had the same outcome, which means a difference of approximately 160 admissions in this unit during the analyzed period. It is important to point out that intrapartum emergency C-sections only took place in exceptional conditions, such as fetal distress diagnosed by intrapartum cardiotocography category III and placental abruption.

From the maternal point of view, the results are also unfavorable for C-sections. The analysis of hospital readmission rate in the first 30 days after birth is one of the indicators proposed by the Health Care Payment Learning & Action Network working group. It reveals that it is more than 20% higher in cases of cesarean delivery than in vaginal delivery for the studied groups, although without statistical significance [ 26 ]. Maternal ICU admission rate also denotes a disadvantage for C-sections. Again, the causes are multifactorial but obviously closely related to the complications of the procedure. A retrospective study involving more than 14 thousand cases already exposed a higher rate of hospital readmission. These are mainly related to surgical wound infection in post-cesarean patients and that corroborates the data found in this series [ 32 ].

As proposed by the CQMC (Core Quality Measures Collaborative), breastfeeding in the first hour of life was considered as a value delivery [ 25 ]. Once again, the difference is in favor of vaginal delivery with an average adherence of 92% of cases versus 88% in C-sections. Factors such as postpartum position, anesthetic condition and surgical environment must have contributed to these results [ 33 , 34 ] .

The remaining question is related to the continuity of a potentially harmful practice in relation to the other whose value delivery is shown to be greater. The answer to these questions is complex and involves several factors that generated the preference for C-section. They range from the model of remuneration for childbirth care to the judicialization of health, patient’s apprehension about a painful process, reduction of training in vaginal deliveries, cultural issues (such as fear of a painful process), and lack of active nursing support during labor [ 14 ].

Evidently, particularities about the assistance model of each country must be taken into account. In countries such as Brazil, where private assistance to labor is personalized, the assistance by a team in a shift and dichotomization between prenatal care and delivery may be plausible solutions when requiring more predictable availability from the assistance team. In other countries where this practice is already in vogue, the payment of bonus linked to outcomes could also bring benefits. Furthermore, cultural issues in countries that perceive C-section as the safer mode of delivery may also be addressed in educational campaigns.

Based on the above, it becomes clear that changes in the current form of obstetric care adapted to each economic model are urgent. Adjustments in the remuneration model may be important in countries with personalized and doctor-centered obstetric care. It is difficult to establish the ideal model, especially considering the differences between public and private systems.

However, ideas such as the use of the Global Budget defined by the average diagnosis-related-groups (DRG) of the target population and the payment of salaries to doctors have been used to manage hospitals. In this case, the hospital receives a fixed amount (monthly or yearly) to offer its services, regardless of the volume of resources it uses. With some nuances, as goals to be met and additional compensation by special procedures or accreditations, this model is used in some Social Health Organizations (OSS) in Brazil, in which non-profit companies manage government hospitals by fixed monthly values [ 35 ]. Also, a better structure of a bonus policy for professionals related to value delivery, besides the payment of salaries, could also be considered.

Finally, it is also necessary to build a better health system and medical teaching process to allow improvement in vaginal delivery rate, and consequently achieve better results and low costs regarding the delivery.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study are the detailed analysis of the causes for higher costs of cesarean sections and the description of worse results related to it. One clear advantage was the exclusion of high-risk cases that could cause an interpretation bias.

This study included a specific population and considered only low-risk pregnancies from a Brazilian private hospital. For that reason, it is essential to understand the reality of other medical institutions, both in clinical and cost-related terms. This is because vaginal delivery assistance can vary substantially in quality.

Besides that, the allocation of fixed and variable costs between different institutions may also differ. It is also necessary to understand whether the data can be replicated when the high-risk pregnancies are considered.

Finally, it could be stated that it is common to perform elective cesarean sections due to the maternal desire in the analyzed hospital, a reality that is not always present in every service and that could affect our results.

Data from a national hospital-based cohort with 23,940 postpartum women, held in 2011–2012, showed an initial preference for cesarean delivery of 27.6%, ranging from 15.4% (primiparous public sector) to 73.2% (multiparous women with previous cesarean private sector). The main reason for the choice of vaginal delivery was the best recovery of this type of delivery (68.5%) and for the choice of cesarean, the fear of pain (46.6%). Women from private sector presented 87.5% caesarean, with increased decision for cesarean birth in end of gestation, independent of diagnosis of complications. In both sectors, the proportion of caesarean section was much higher than desired by women [ 36 ].

Cesarean deliveries in low-risk pregnancies were associated with a lower value delivery because, in addition to being more expensive, they had worse perinatal outcomes. Reviewing the financing model as well as the practice itself is essential to deliver more value-based healthcare in obstetrics.

Availability of data and materials

The data of this article are available with the corresponding author, by email [email protected] .

Xu K, Soucat A, Kutzin J, et al. Public spending on health: a closer look at global trends: World Health Organization (WHO); 2018.

Google Scholar

Silveira D. 2019. Available at https://g1.globo.com/economia/noticia/2019/12/20/gasto-de-brasileiros-com-saude-privada-em-relacao-ao-pib-e-mais-que-dobro-da-media-dos-paises-da-ocde-diz-ibge.ghtml ; Accessed Dec 2019.

Barros A in IBGE News. 2019. Available at https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia-noticias/2012-agencia-de-noticias/noticias/26444-despesas-com-saude-ficam-em-9-2-do-pib-e-somam-r-608-3-bilhoes-em-2017 ; Accessed Dec 2019.

Ribeiro A, et al. Observatório 2019: ANHAP - Associação Nacional dos Hospitais Privados; 2019.

Médici A, Ribeiro A, et al. Observatório 2020: ANHAP - Associação Nacional dos Hospitais Privados; 2020.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUP Facts and figures: statistics on hospital based care in the United States, 2009. 2011. Available at (last accessed in April, 2020): http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/factsandfigures/2009/pdfs/FF_report_2009.pdf .

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Statistical brief: cost of childbirth. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. Available at (last accessed in April, 2020): https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb107.pdf . Jan 2019.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUPNet, healthcare cost & utilization project. complications of pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium. 2003. Available at (last accessed in April, 2020): http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUPNet, healthcare cost & utilization project. certain conditions originating in the perinatal period. 2013. Available at (last accessed in April, 2020): http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov

Global Date. Forthcoming report about preterm births 2015.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (College); Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Caughey AB, Cahill AG, Guise JM, Rouse DJ. Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(3):179–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.026 .

Article Google Scholar

Leite AC, Araujo Júnior E, Helfer TM, Marcolino LA, Vasques FA, Sá RA. Comparative analysis of perinatal outcomes among different typesof deliveries in term pregnancies in a reference maternity of Southeast Brazil. Ceska Gynekol. 2016;81(1):54–7.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Etringer AP, Pinto MFT, Gomes MASM. Análise de custos da atenção hospitalar ao parto vaginal e à cesariana eletiva para gestantes de risco habitual no Sistema Único de Saúde. Cien Saude Colet. 2019;24(4).

Truven Health Analytics. The cost of having a baby in the United States. 2013. Available at (last accessed in April, 2020): http://transform.childbirthconnection.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Cost-of-Having-aBaby-Executive-Summary.pdf

Molina G, Weiser TG, Stuart R, et al. Relationship between cesarean delivery rate and maternal and neonatal mortality. JAMA. 2015;314(21):2263–70. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.15553 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

SINASC/DATASUS. Available at (last accessed in April, 2020): http://www2.datasus.gov.br/DATASUS/index.php?area=060702 .

Vogt SE, Silva KS, Dias MAB. Comparison of childbirth care models in public hospitals, Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2014;48(2):304–13. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-8910.2014048004633 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Brown MM, Brown GC, Brown HC, Irwin B, Brown KS. The comparative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of vitreoretinal interventions. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2008;19(3):202–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICU.0b013e3282fc9c35 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bae J. Value-based medicine. Epidemiol Health. 2015;37:e2015014. https://doi.org/10.4178/epih/e2015014 .

Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2477–81. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1011024 .

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington: National Academies Press; 2001.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement. QCV100: an introduction to quality, cost, and value in health care. 2016. http://app.ihi.org/lms/home.aspx .

Quinn K. The 8 basic payment methods in health care. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(4):300–6. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-2784 .

OCDE Focus on. Better ways to pay for health care. Available at (last accessed in Apr 2020): https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Better-ways-to-pay-for-health-care-FOCUS.pdf . Jun 201.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Core measures: Disponível em; 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityMeasures/Core-Measures.html .

Healthcare Payment Learning and Action Network. Accelerating and aligning clinical episode payment models. McLean: The MITRE Corporation; 2018. Available at (last accessed in Apr 2020): http://hcp-lan.org/workproducts/cep-whitepaper-final.pdf .

Vogel JP, Betrán AP, Vindevoghel N, Souza JP, Torloni MR, Zhang J, et al. Use of the Robson classification to assess caesarean section trends in 21 countries: a secondary analysis of two WHO multicountry surveys. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(5):e260–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70094-X .

Negrini R, Ferreira RDDS, Albino RS, Daltro CAT. Reducing caesarean rates in a public maternity hospital by implementing a plan of action: a quality improvement report. BMJ Open Qual. 2020;9(2).

Borem P, de Cássia SR, Torres J, et al. A quality improvement initiative to increase the frequency of vaginal delivery in Brazilian hospitals. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(2):415–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003619 .

Curet LB, Zachman RD, Rao AV, Poole WK, Morrison J, Burkett G. Effect of mode of delivery on incidence of respiratory distress syndrome. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1988;27(2):165–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7292(88)90002-1 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Yee W, Amin H, Wood S. Elective cesarean delivery, neonatal intensive care unit admission, and neonatal respiratory distress. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(4):823–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816736e7 .

Ergen EB, Ozkaya E, Eser A, et al. Comparison of readmission rates between groups with early versus late discharge after vaginal or cesarean delivery: a retrospective analyzes of 14,460 cases. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31(10):1318–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2017.1315661 .

Brown A, Jordan S. Impact of birth complications on breastfeeding duration: an internet survey. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(4):828–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06067.x Epub 2012 Jul 5. PMID: 22765355.

Zanardo V, Svegliado G, Cavallin F, Giustardi A, Cosmi E, Litta P, et al. Elective cesarean delivery: does it have a negative effect on breastfeeding? Birth. 2010;37(4):275–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00421.x PMID: 21083718.

Morais HMM, Albuquerque MSV, Oliveira RS, Cazuzu AKI, Silva NAFD. Social healthcare organizations: a phenomenological expression of healthcare privatization in Brazil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2018;34(1):e00194916. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00194916 .

Domingues RMSM, Dias MAB, Nakamura-Pereira M, et al. Process of decision-making regarding the mode of birth in Brazil: from the initial preference of women to the final mode of birth. Cad Saúde Pública. 2014;30(Suppl 1):S101–16 [cited 2021 Feb 28]. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0102-311X2014001300017&lng=en . https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00105113 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and publication of this article.

The data was obtained by the hospital’s medical records system with no cost involved.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Maternal and Child Department, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, Av. Albert Einstein, 627 - Jardim Leonor, São Paulo, SP, 05652-900, Brazil

Romulo Negrini, Raquel Domingues da Silva Ferreira & Daniela Zaros Guimarães

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Romulo Negrini: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing- Original draft preparation. Raquel D S Ferreira: Validation, Data curation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Visualization . Daniela Z Guimarães: Writing- Reviewing and Editing. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Romulo Negrini .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study obtained ethical clearance from the Sociedade Israelita Brasileira - Hospital Albert Einstein – SP - Brazil ethical committee (protocol number 31362720.2.0000.0071 / 2020).

The informed consent was waived by this cited ethical committee (Sociedade Israelita Brasileira - Hospital Albert Einstein – SP - Brazil) considering the study used only a hospital database, not collecting information from specific patients or even conducting clinical interventions (opinion of ethic committee number 4.803.450).

All author declares that all procedure in this study were conducted in accordance with the international and institutional (Sociedade Israelita Brasileira - Hospital Albert Einstein) relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

There are no competing interests in this publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Negrini, R., da Silva Ferreira, R.D. & Guimarães, D.Z. Value-based care in obstetrics: comparison between vaginal birth and caesarean section. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21 , 333 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03798-2

Download citation

Received : 01 December 2020

Accepted : 08 April 2021

Published : 26 April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03798-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Healthcare cost

- Delivery of healthcare

- Quality of healthcare

- Birth setting

- Obstetric delivery

- Cesarean section

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth

ISSN: 1471-2393

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 07 April 2020

Prevalence, indications, and outcomes of caesarean section deliveries in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Getnet Gedefaw 1 ,

- Asmamaw Demis 2 ,

- Birhan Alemnew 3 ,

- Adam Wondmieneh 2 ,

- Addisu Getie 2 &

- Fikadu Waltengus 4

Patient Safety in Surgery volume 14 , Article number: 11 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

18k Accesses

38 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Caesarean section rates have increased worldwide in recent decades. Caesarean section is an essential maternal healthcare service. However, it has both maternal and neonatal adverse outcomes. Therefore this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to estimate the prevalence, indication, and outcomes of caesarean section in Ethiopia.

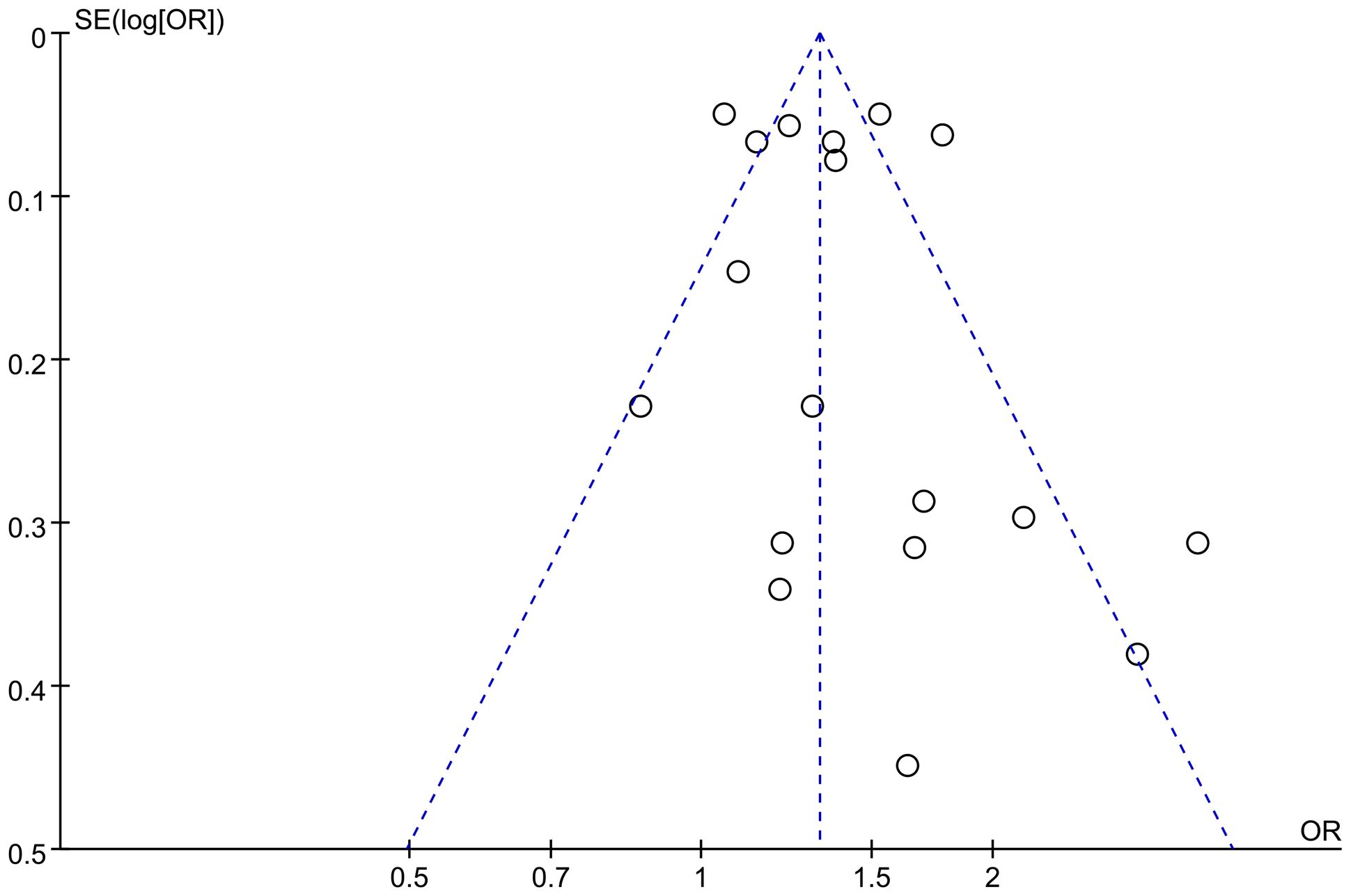

Twenty three cross-sectional studies with a total population of 36,705 were included. Online databases (PubMed/Medline, Hinari, Web of Science, and Google Scholar) and online university repository was used. All the included papers were extracted and appraised using the standard extraction sheet format and Joanna Briggs Institute respectively. The pooled prevalence of the caesarean section, indications, and outcomes was calculated using the random-effect model.

The overall pooled prevalence of Caesarean section was 29.55% (95% CI: 25.46–33.65). Caesarean section is associated with both maternal and neonatal complications. Cephalopelvic disproportion [18.13%(95%CI: 12.72–23.53] was the most common indication of Caesarean section followed by non-reassuring fetal heart rate pattern [19.57% (95%CI: 16.06–23.08]. The common neonatal complications following Caesarean section included low APGAR score, perinatal asphyxia, neonatal sepsis, meconium aspiration syndrome, early neonatal death, stillbirth, and prematurity whereas febrile morbidity, surgical site infection, maternal mortality, severe anemia, and postpartum hemorrhage were the most common maternal complications following Caesarean section.

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, the rate of Cesarean section was high. Cephalopelvic disproportion, low Apgar score, and febrile morbidity were the most common indication of Caesarean section, neonatal outcome and maternal morbidity following Caesarean section respectively. Increasing unjustified Caesarean section deliveries as a way to increase different neonatal and maternal complications, then several interventions needed to target both the education of professionals and the public.

Caesarean section is the commonest operative delivery technique in the world. Caesarean section is the delivery of the fetus, membrane, and placenta through abdominal and uterine incision after fetal viability [ 1 ].

The rate of Caesarean section is different across countries even between urban and rural areas, due to different socio-economic statuses, and opportunities to access public and private health care services [ 2 ].

According to American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist (ACOG) report, Caesarean delivery significantly increased woman’s risk vulnerability of pregnancy-related morbidity and mortality which accounts (35.9 deaths per 100,000 live deliveries) as compared to a women posses vaginal delivery (9.2 deaths per 100,000 live births) [ 3 ].

Despite Caesarean section a life saving medical intervention and procedures to the decrease adverse birth outcome, controlling different postoperative neonatal and maternal complications are challenging in terms of patient safety, long duration of hospital stay, cost and psychological trauma. Maternal outcomes of Caesarean section included: postpartum fever, surgical site infection, puerperal sepsis, maternal mortality whereas neonatal sepsis, early neonatal death, stillbirth, perinatal asphyxia, low Apgar score, and prematurity were the most common complication of the newborn [ 4 , 5 , 6 ].

Despite World Health Organization (WHO) recommended the optimal rate of Caesarean section should be lie between 5 and 15%, it is significantly increasing even if the reasons for the continued increase in the Caesarean rates are not completely understood: women are having fewer children, maternal age is rising, use of electronic fetal monitoring is widespread, malpresentation especially breech presentation, frequency of forceps and vacuum delivery is decreased, rate of labor induction increases, obesity dramatically rises and Vaginal birth after Caesarean decreased are some of the possible explanations [ 7 ].

Previous Caesarean scar, malpresentation and malposition, antepartum hemorrhage, obstructed labor, cephalopelvic disproportion, non-reassuring fetal heart rate pattern, and multiple pregnancies are the most common indications of Caesarean section [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 8 ].

According to the 2016 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey, the rate of C-section (21.4%) in Addis Ababa was far more than the 10–15% rate recommended by the world health organization. EDHS (2016) report showed there is an absolute difference rate of Caesarean section across different regions in Ethiopia which accounts Amhara (2.3%), Oromia (0.9%), SNNPR(1.9%), Afar (0.7%), Tigray (2%), Somali(0.4%), Benishangul Gumuz (1%) too far from the lowest 5% WHO recommendation of Caesarean section deliveries. This review helps to see C-section rates beyond 15% and below 5% is considered medically unjustified or unnecessary, with negligible benefits for most mothers, and yet costly and unequally distributed throughout the population [ 9 , 10 ].

Ethiopia is a good case study to assess Caesarean prevalence, indications, and outcomes because, like other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, maternal mortality and neonatal mortality did not decline sufficiently to meet the Sustainable Development Goal for maternal health and child, and was estimated at 412 maternal deaths and 29 neonatal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2016 [ 9 ].

Despite a few single studies stated different maternal and fetal outcomes of Caesarean section, there is a lack of data to show the distribution and outcome of Caesarean section in different regions where they are provided.

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to estimate the pooled prevalence of Caesarean section deliveries and to determine the indications and outcomes of Caesarean section deliveries in Ethiopia.

This systematic review and meta-analysis have been conducted to estimate the pooled prevalence of Caesarean section, indications, maternal and neonatal outcomes in Ethiopia via the standard PRISMA checklist guideline.

Search strategy

International databases (PubMed, Google Scholar, Web of science and HINARI), different gray works of literature and articles in the university repository were included. The searching engine terms were used using PICO formulating questions. These are: “newborn”, “neonatal”, “birth outcome”, “stillbirth”, perinatal asphyxia””, “neonatal sepsis”, “prematurity”, “early neonatal death”, “low Apgar score”, “preterm”, “maternal mortality”, “wound infection”, “surgical site infection”, “febrile morbidity”,” puerperal sepsis”, “puerperal fever”, postpartum hemorrhage”, “blood loss”, “anemia”, “leading factors of Caesarean section”, “indications of Caesarean section”, “Ethiopia”. The following search engine terms were used: neonate OR newborn OR women OR infant OR fetal OR children AND “neonatal sepsis” OR “perinatal asphyxia” OR “low Apgar score” OR “stillbirth” OR “prematurity” OR “preterm birth” OR “early neonatal death” OR “perinatal” OR “neonatal death” OR “preterm “puerperal sepsis” OR “puerperal fever” OR “wound infection” OR “surgical site infection” OR “postpartum hemorrhage” OR “anemia” OR “maternal mortality” OR “maternal death” OR “blood loss” OR “indication of Caesarean section, ‘factors of Caesarean section”, “leading factors of Caesarean section”, “fetal indication of CS”, “Maternal indication of CS”AND Ethiopia and related terms.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Twenty three (23) cross-sectional studies were included. Articles reported prevalence or/and an indication, or/and neonatal outcomes or/and maternal outcomes were incorporated. Only English language literature and research articles were included. Studies published till October 2019 were reviewed, screened and appraised for this study. Whereas, articles without full abstracts or texts and articles reported out of the scope of the outcome interest were excluded.

Quality assessment

GG, AD & AW independently evaluated the quality of each study using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality appraisal checklist [ 11 ]. Any disagreement was resolved by the hindrance of the third reviewer (FW, BA &AG). The following JBI items used to appraise cross-sectional studies were: [ 1 ] inclusion criteria, [ 2 ] description of study subject and setting, [ 3 ] valid and reliable measurement of exposure, [ 7 ] objective and standard criteria used, [ 9 ] identification of confounder, [ 10 ] strategies to handle confounder, [ 12 ] outcome measurement, and [ 13 ] appropriate statistical analysis. Hence, studies considered with the JBI checklist value of 50% and above of the quality assessment indicators as low risk and good to be included for the analysis.

Data extraction

All the datasets are exported to Endnote version X8 software, and then we transferred to the Microsoft Excel spreadsheet to remove duplicate data in the review. Three authors (GG, AD, and AG) independently extracted all the important data using a standardized JBI data extraction format. Any disagreement between reviewers was resolved by the second team reviewers (FW, BA & AW). The consensus was declared through critical discussion and evaluation of the articles by the independent group reviewers. The name of the author, sample size, publication year, study area, response rate, region, study design, the prevalence of specific maternal outcomes, the prevalence of neonatal outcomes, indications of Caesarean section, and prevalence of Caesarean section with 95%CI were extracted.

Outcome of measurements

Neonatal outcomes.

Any neonatal outcomes reported following C-section (Stillbirth, prematurity, neonatal sepsis, perinatal asphyxia, low Apgar score, and early neonatal death) were included.

Maternal outcomes

Any maternal complications identified after C-section were included puerperal sepsis, wound infection (surgical site infection), febrile morbidity (puerperal fever), postpartum hemorrhage, severe anemia, and maternal mortality.

Indications of caesarean section

Both maternal and fetal indications (obstructed labor, cephalo pelvic disproportion, NRFHRP (Non-reassuring fetal heart rate pattern), multiple gestations, failed induction, malpresentation, malposition, and antepartum hemorrhage) were included.

Data analysis

A Funnel plot and Eggers regression test was used to check publication bias [ 14 ]. Cochrane Q-test and I-squared statistics were computed to check the heterogeneity of studies [ 15 , 16 ]. Pooled analysis was conducted using a weighted inverse variance random-effects model [ 17 ]. Subgroup analysis was done by study region (area), and sample size. STATA version 11 statistical software was used to compute the analysis. Forest plot format was used to present the pooled point prevalence, indications and outcomes of C-section with 95%Cl.

Characteristics of the included studies

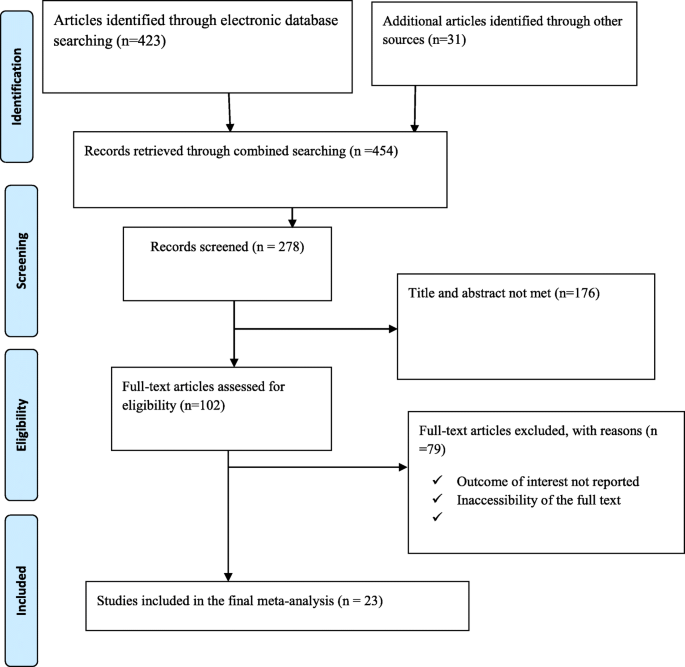

Four hundred twenty-three studies were retrieved at PubMed, Google Scholar, Science Direct, web of science, HINARI and other gray and online repository accessed articles regarding prevalence, indications, and the maternal and fetal outcome of Caesarean section in Ethiopia. After duplicates were expunged, 278 studies remained.

Out of 278 remained articles, 176 articles were excluded after review of their titles and abstracts. Therefore, 102 full-text articles were accessed and assessed for inclusion criteria, which resulted in the further exclusion of 79 articles primarily due to reason. As a result, 23 studies were met the inclusion criteria to undergo the final systematic review and meta-analysis (Fig. 1 ) (Table 1 ).

Flow chart of study selection for systematic review and meta-analysis of indications, maternal and fetal outcomes of cesarean section in Ethiopia

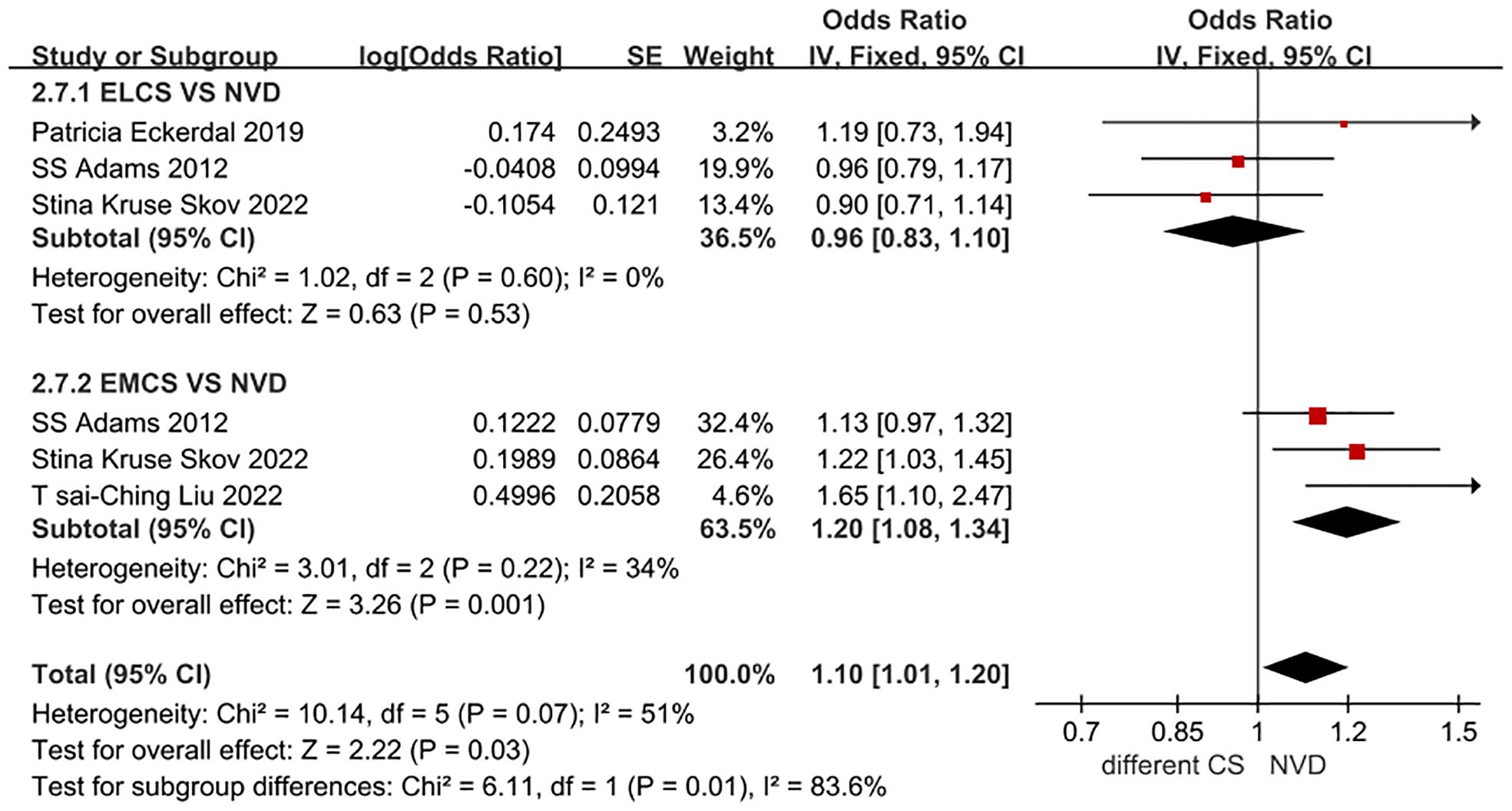

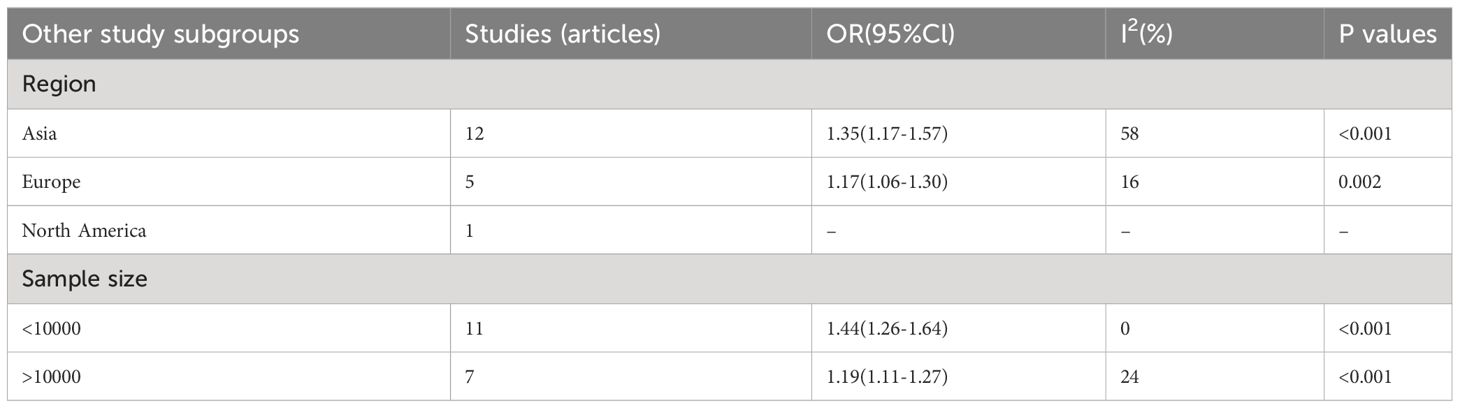

Prevalence of caesarean section in Ethiopia

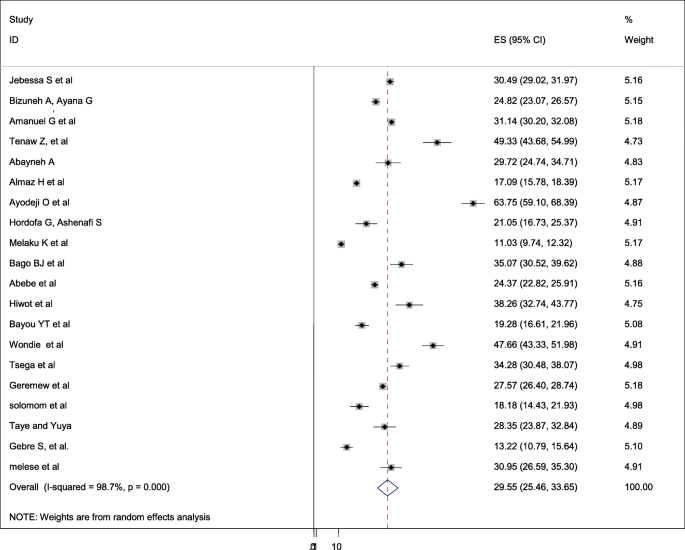

The overall pooled prevalence of Caesarean section is presented with a forest plot ( Fig. 2 ). Therefore, the pooled estimated prevalence of Caesarean section in Ethiopia was 29.55% (95% CI; 25.46–33.65; I2 = 98.7%, P < 0.001).

Forest plot of the pooled prevalence of cesarean section in Ethiopia

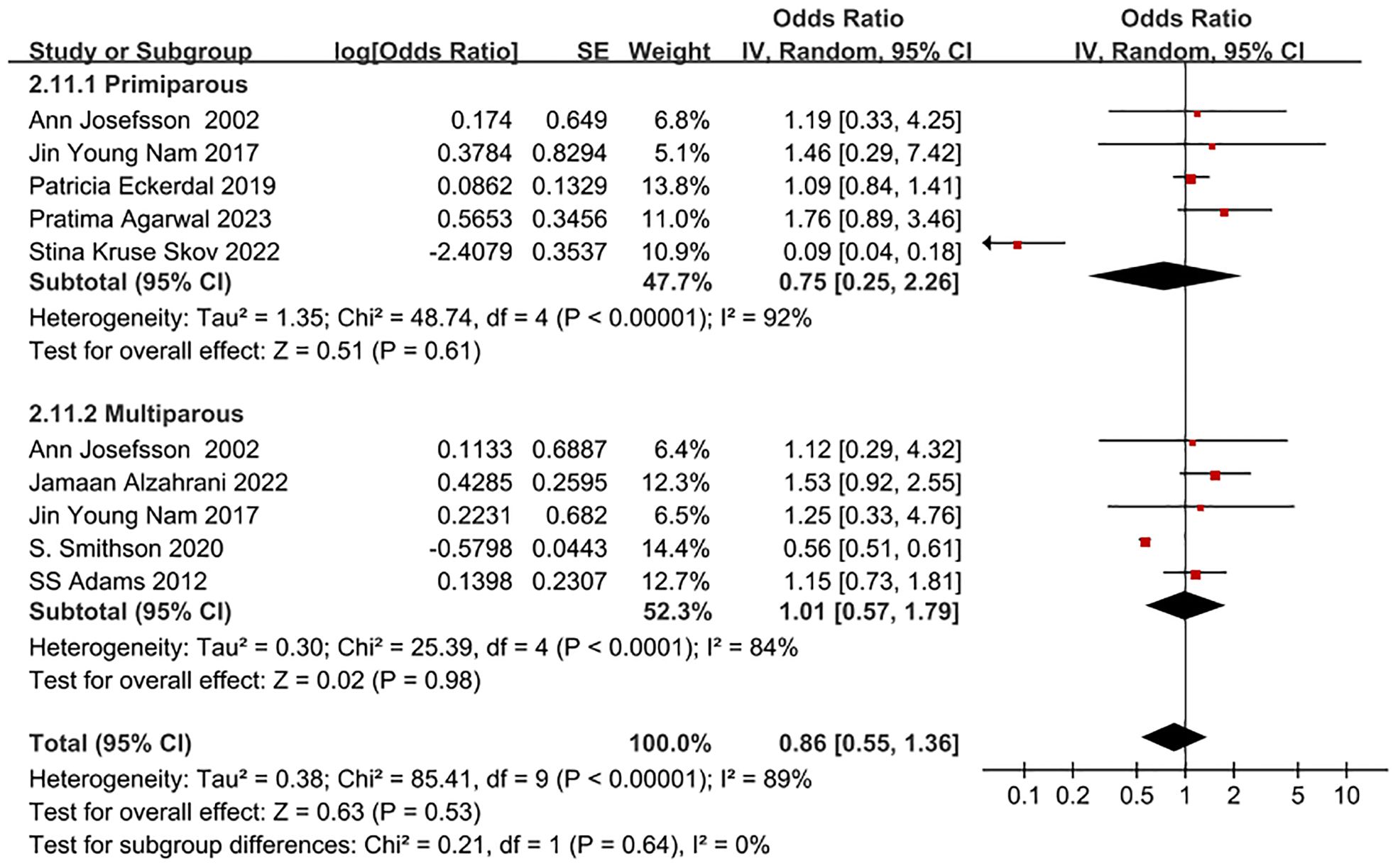

Publication bias

A funnel plot was assessed for the asymmetry distribution of the Caesarean section using visual inspection of the forest plot ( Fig. 3 ). Egger’s regression test showed with a p -value of 0.251 indicated the absence of publication bias.

Funnel plot with 95% confidence limits of the pooled prevalence of cesarean section in Ethiopia

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis was computed with the evidence of heterogeneity. Hence the Cochrane I 2 statistic =98.7%, P < 0.001) showed the presence of marked heterogeneity in this study. Therefore subgroup analysis was implemented using the study area (region) and sample size using random model effect analysis. Regarding the study area (region), the prevalence of Caesarean section was highest in Addis Ababa, accounted for 40.39% (95%CI: 12.35, 68.43) whereas the rate of Caesarean section was higher among studies of having sample size less than 500, accounted for 34.91% (95%CI: 25.48–44.34) ( Fig. 4 - 5 ).

Forest plot of the subgroup analysis based on region (area) of the study

Forest plot of the subgroup analysis based on the sample size of the study

Indication of caesarean section

In this systematic review and meta-analysis; obstructed labor, cephalopelvic disproportion, multiple pregnancies, non-reassuring fetal heart rate pattern (NRFHRP), failed induction and augmentation, malpresentation and malposition, and antepartum hemorrhage are the most common indications of Caesarean section. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD) is the most common indication of Caesarean section followed by non-reassuring fetal heart rate pattern (NRFHRP), and obstructed labor in Ethiopia ( Table 2 ).

Neonatal complication following caesarean section in Ethiopia

Among women who underwent Caesarean section; neonatal sepsis, early neonatal death, stillbirth, low Apgar score, perinatal asphyxia (PNA), meconium aspiration syndrome, and prematurity were the reported neonatal complications in this study. Among neonatal complications, low Apgar score was the most common adverse complication of the newborn followed by perinatal asphyxia and neonatal sepsis respectively in Ethiopia (Table 3 ).

Maternal complications following caesarean section in Ethiopia

Following Caesarean section different adverse maternal complications were reported. Febrile morbidity, puerperal sepsis, postpartum hemorrhage, surgical site infection, maternal mortality, and severe anemia were the most common adverse maternal complications following Caesarean section. Puerperal fever or febrile morbidity was the leading cause of maternal morbidity following Caesarean section followed by postpartum hemorrhage in Ethiopia (Table 4 ).

Despite Caesarean section is an essential component of comprehensive obstetric and newborn care for reducing maternal and neonatal mortality, there is a lack of data regarding Caesarean section rates, its indications and outcomes in Ethiopia. Studies showed negative or no complications of Caesarean on neonatal mortality in low and middle-income countries where the Caesarean rates are high. Cesarean section is very crucial in settings where the Caesarean rates are very low, due to the unavailability of Caesarean [ 39 ].

Caesarean sections can cause significant and sometimes permanent complications, disability or death particularly in settings that lack the facilities and/or capacity to properly conduct safe surgery and treat surgical complications [ 40 ].

Low- and middle-income countries, wealthy women have more than five times higher C-section use than poor women. In the United States, 32% of births were by C-section in 2015, an increase from 23% in 2000, as the data showed, and in the United Kingdom, 26.2% of births were by C-section in 2015, up from 19.7% in 2000. According to the World Health Organization report, the country with the lowest C-section rate, at 0.6% in 2010, was South Sudan and the country with the highest, at 58.1% in 2014, was the Dominican Republic. Whereas, some countries where more than half of births were by C-section were Brazil, at 55.5% in 2015; Egypt, at 55.5% in 2014; Turkey, at 53.1% in 2015; and Venezuela, at 52.4% in 2013 [ 41 ].

The overall prevalence of Caesarean section in Ethiopia was 29.55% (95% CI: 25.46–33.65). This report is higher than the study done in Saudi Arabia [ 42 ], Nigeria [ 43 ], Pakistan [ 44 ], India [ 5 ], Brazil [ 45 ] and low and middle-income countries analysis [ 46 ]. This discrepancy might be due to the age of the mother elapses the ideal birth time, significantly increasing, non-communicable disease, increasing electronic fetal monitoring availability and accessibility in referral and general hospitals. This study finding is lower than the study done in Nepal, North America and Western Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean [ 47 ]. This difference might be due to countries with a rich wealth index that may have the capacity to have modern operative obstetrics management as compared to low and middle countries. Hence, low and middle-income countries have resource limitation and c-section is resource-constrained, may have low comprehensive obstetric health care services.

Antepartum hemorrhage, non-reassuring fetal heart rate pattern, malpresentation, and malposition, failed induction, obstructed labor, multiple gestations, cephalopelvic disproportion were the most common indications of Caesarean section in Ethiopia. This study finding is supported by the study done in low and middle-income countries [ 46 ], Saudi Arabia [ 42 ], Ghana [ 6 , 8 ], Jordan [ 4 ] and India [ 5 ].

Neonatal sepsis, stillbirth, prematurity, perinatal asphyxia, low Apgar score, and meconium aspiration syndrome were the most common neonatal complications following the Caesarean section in Ethiopia. This study finding is supported by the study done in India [ 5 ], Jordan [ 4 ], and Ghana [ 6 ].

Postpartum hemorrhage, surgical site infection, puerperal fever, anemia, and maternal mortality were the most common neonatal adverse outcome of Caesarean section in Ethiopia. The finding of this study is supported by the study done in India [ 5 ], Jordan [ 4 ], and African countries [ 48 ].

In this study, the overall pooled prevalence of Caesarean section in Ethiopia was high. Non-reassuring fetal heart rate patterns, cephalopelvic disproportion, and obstructed labor were the most common indication of Caesarean section. Low Apgar score, perinatal asphyxia, and neonatal sepsis were the most common complication of neonates whereas postpartum hemorrhage and febrile morbidity were the common maternal complications following the Caesarean section in Ethiopia. Therefore, based on the study findings, the authors recommend a particular emphasis to follow the WHO recommendations and guidelines. Avoiding unjustified and unnecessary indications for Caesarean sections has a significantly higher impact to prevent poor maternal and fetal outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

All related data has been presented within the manuscript. The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available from the corresponding author on request.

Abbreviations

- Caesarean section

Postpartum hemorrhage,

Obstructed labor

Cephalopelvic disproportion

Antepartum hemorrhage

South Nation Nationalities and Peoples region

Confidence Interval

Lyell DJ, Power M, Murtough K, Ness A, Anderson B, Erickson K, Schulkin J. Surgical techniques at cesarean delivery: a US survey. Surg J. 2016;2(04):e119–25.

Article Google Scholar

Strom S. Rates, Trends, and Determinants of Cesarean Section Deliveries in El Salvador: 1998 to 2008 (doctoral dissertation); 2013.

Google Scholar

Rayburn WF, Strunk AL. Profiles about practice settings of American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists fellows. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(6):1295–8.

BĂƟĞŚĂ AM, Al-Daradkah SA, Khader YS, Basha A, Sabet F, et al. Cesarean ^ĞcƟŽn͗ incidence, causes, associated factors and outcomes: a NĂƟŽnĂů WrŽƐƉĞcƟǀĞ study from Jordan. Gynecol Obstet Case Rep. 2017;3(3):5.

Desai G, Anand A, Modi D, Shah S, Shah K, Shah A, et al. Rates, indications, and outcomes of caesarean section deliveries: a comparison of tribal and non-tribal women in Gujarat, India. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0189260. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189260 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gulati D, Hjelde GI. Indications for Cesarean Sections at Korle Bu Teaching Hospital. Ghana (Master's thesis); 2012.

Betrán AP, Merialdi M, Lauer JA, Bing-Shun W, Thomas J, Van Look P, Wagner M. Rates of caesarean section: analysis of global, regional and national estimates. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2007;21(2):98–113.