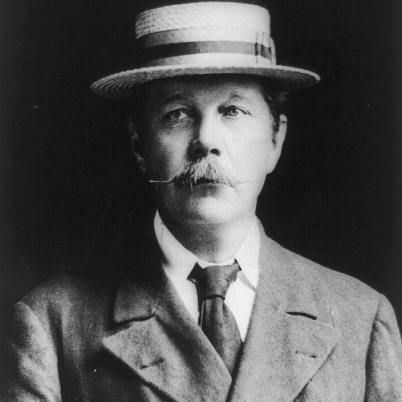

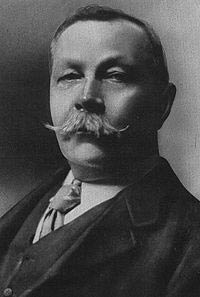

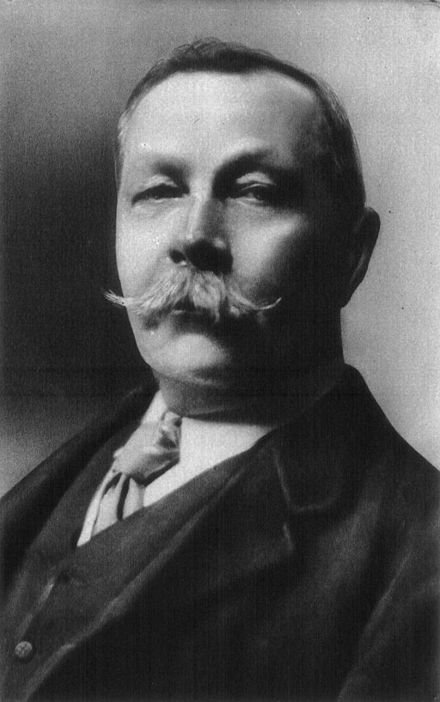

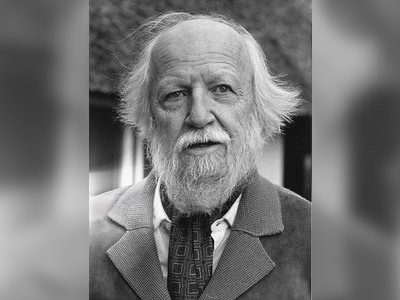

Arthur Conan Doyle

(1859-1930)

Who Was Arthur Conan Doyle?

In 1890, Arthur Conan Doyle's novel, A Study in Scarlet introduced the character of Detective Sherlock Holmes. Doyle would go on to write 60 stories about Sherlock Holmes. He also strove to spread his Spiritualism faith through a series of books that were written from 1918 to 1926. Doyle died of a heart attack in Crowborough, England on July 7, 1930.

On May 22, 1859, Arthur Conan Doyle was born to an affluent, strict Irish-Catholic family in Edinburgh, Scotland. Although Doyle's family was well-respected in the art world, his father, Charles, who was a life-long alcoholic, had few accomplishments to speak of. Doyle's mother, Mary, was a lively and well-educated woman who loved to read. She particularly delighted in telling her young son outlandish stories. Her great enthusiasm and animation while spinning wild tales sparked the child's imagination. As Doyle would later recall in his biography, "In my early childhood, as far as I can remember anything at all, the vivid stories she would tell me stand out so clearly that they obscure the real facts of my life."

At the age of 9, Doyle bid a tearful goodbye to his parents and was shipped off to England, where he would attend Hodder Place, Stonyhurst — a Jesuit preparatory school — from 1868 to 1870. Doyle then went on to study at Stonyhurst College for the next five years. For Doyle, the boarding-school experience was brutal: many of his classmates bullied him, and the school practiced ruthless corporal punishment against its students. Over time, Doyle found solace in his flair for storytelling and developed an eager audience of younger students.

Medical Education and Career

When Doyle graduated from Stonyhurst College in 1876, his parents expected that he would follow in his family's footsteps and study art, so they were surprised when he decided to pursue a medical degree at the University of Edinburgh instead. At med school, Doyle met his mentor, Professor Dr. Joseph Bell, whose keen powers of observation would later inspire Doyle to create his famed fictional detective character, Sherlock Holmes. At the University of Edinburgh, Doyle also had the good fortune to meet classmates and future fellow authors James Barrie and Robert Louis Stevenson. While a medical student, Doyle took his own first stab at writing, with a short story called The Mystery of Sasassa Valley . That was followed by a second story, The American Tale , which was published in London Society .

During Doyle's third year of medical school, he took a ship surgeon's post on a whaling ship sailing for the Arctic Circle. The voyage awakened Doyle's sense of adventure, a feeling that he incorporated into a story, Captain of the Pole Star .

In 1880, Doyle returned to medical school. Back at the University of Edinburgh, Doyle became increasingly invested in Spiritualism or "Psychic religion," a belief system that he would later attempt to spread through a series of his written works. By the time he received his Bachelor of Medicine degree in 1881, Doyle had denounced his Roman Catholic faith.

Doyle's first paying job as a doctor took the form of a medical officer's position aboard the steamship Mayumba, traveling from Liverpool to Africa. After his stint on the Mayumba, Doyle settled in Plymouth, England for a time. When his funds were nearly tapped out, he relocated to Portsmouth and opened his first practice. He spent the next few years struggling to balance his burgeoning medical career with his efforts to gain recognition as an author. Doyle would later give up medicine altogether, in order to devote all of his attention to his writing and his faith.

Personal Life

In 1885, while still struggling to make it as a writer, Doyle met and married his first wife, Louisa Hawkins. The couple moved to Upper Wimpole Street and had two children, a daughter and a son. In 1893, Louisa was diagnosed with tuberculosis. While Louisa was ailing, Doyle developed an affection for a young woman named Jean Leckie. Louisa ultimately died of tuberculosis in Doyle's arms, in 1906. The following year, Doyle would remarry to Jean Leckie, with whom he would have two sons and a daughter.

Books: Sherlock Holmes

In 1886, newly married and still struggling to make it as an author, Doyle started writing the mystery novel A Tangled Skein . Two years later, the novel was renamed A Study in Scarlet and published in Beeton's Christmas Annual . A Study in Scarlet , which first introduced the wildly popular characters Detective Sherlock Holmes and his assistant, Watson, finally earned Doyle the recognition he had so desired. It was the first of 60 stories that Doyle would pen about Sherlock Holmes over the course of his writing career. Also, in 1887, Doyle submitted two letters about his conversion to Spiritualism to a weekly periodical called Light .

Doyle continued to actively participate in the Spiritualist movement from 1887 to 1916, during which time he wrote three books that experts consider largely autobiographical. These include Beyond the City (1893), The Stark Munro Letters (1895) and A Duet with an Occasional Chorus (1899). Upon achieving success as a writer, Doyle decided to retire from medicine. Throughout this period, he additionally produced a handful of historical novels including one about the Napoleonic Era called The Great Shadow in 1892, and his most famous historical novel, Rodney Stone , in 1896.

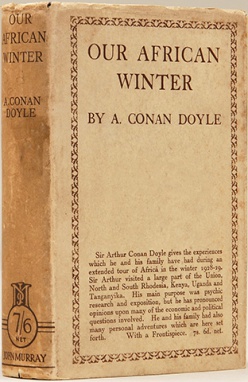

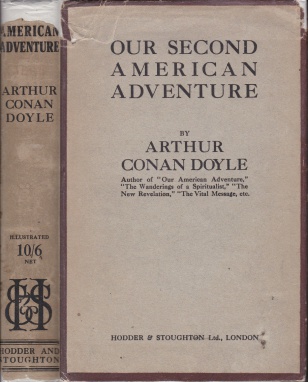

The prolific author also composed four of his most popular Sherlock Holmes books during the 1890s and early 1900s: The Sign of Four (1890), The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1892), The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1894) and The Hound of Baskervilles , published in 1901. In 1893, to Doyle's readers' disdain, he had attempted to kill off his Sherlock Holmes character in order to focus more on writing about Spiritualism. In 1901, however, Doyle reintroduced Sherlock Holmes in The Hound of Baskervilles and later brought him back to life in The Adventure of the Empty House so the lucrative character could earn Doyle the money to fund his missionary work. Doyle also strove to spread his faith through a series of written works, consisting of The New Revolution (1918), The Vital Message (1919), The Wanderings of a Spiritualist (1921) and History of Spiritualism (1926).

In 1928, Doyle's final twelve stories about Sherlock Holmes were published in a compilation entitled The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes .

Having recently been diagnosed with Angina Pectoris, Doyle stubbornly ignored his doctor's warnings, and in the fall of 1929, embarked on a spiritualism tour through the Netherlands. He returned home with chest pains so severe that he needed to be carried on shore and was thereafter almost entirely bedridden at his home in Crowborough, England. Rising one last time on July 7, 1930, Doyle collapsed and died in his garden while clutching his heart with one hand and holding a flower in the other.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Arthur Conan Doyle

- Birth Year: 1859

- Birth date: May 22, 1859

- Birth City: Edinburgh

- Birth Country: Scotland

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Author Arthur Conan Doyle wrote 60 mystery stories featuring the wildly popular detective character Sherlock Holmes and his loyal assistant Watson.

- Journalism and Nonfiction

- Fiction and Poetry

- Astrological Sign: Gemini

- Hodder Place, Stonyhurst

- Stonyhurst College

- University of Edinburgh

- Nacionalities

- Scot (Scotland)

- Death Year: 1930

- Death date: July 7, 1930

- Death City: Crowborough

- Death Country: United Kingdom

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Arthur Conan Doyle Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/arthur-conan-doyle

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: June 17, 2020

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- Where there is no imagination there is no horror.

Famous British People

The Real Royal Scheme Depicted in ‘Mary & George’

William Shakespeare

Anya Taylor-Joy

Kate Middleton, Princess of Wales

Kensington Palace Shares an Update on Kate

Amy Winehouse

Prince William

Where in the World Is Kate Middleton?

Christopher Nolan

Emily Blunt

Jane Goodall

Biography Online

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Biography

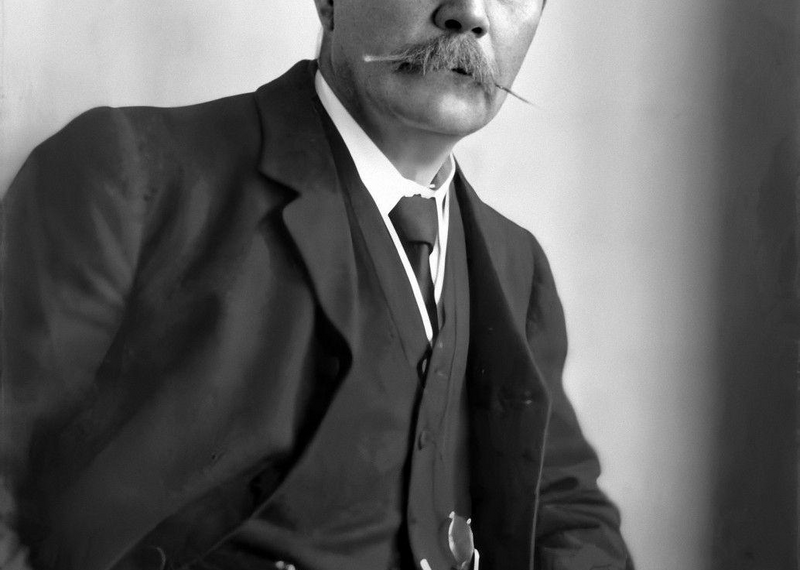

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) – Scottish writer, physician and spiritualist – best known for his Sherlock Holmes stories.

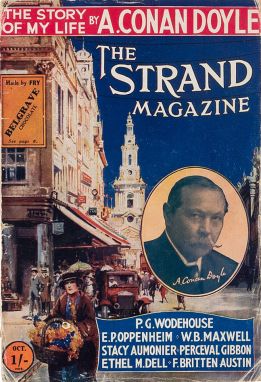

After his father’s death, the burden of supporting a large family fell on Arthur Conan Doyle. To supplement his income he began writing short stories. His first story of note was A Study in Scarlet published in the Beeton’s Christmas Annual 1887 (featuring the first appearance of Sherlock Holmes. This later led to a contract writing more Sherlock Holmes stories for the Strand magazine. It was in these early stories that he developed the character of Sherlock Holmes. It was a character that fascinated the reading public and he soon became one of the best-loved fictional characters. Sherlock Holmes always had an element of mystery – the sharpest mind and his unbelievable powers of observation.

“…when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth…”

-Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, (Sherlock Holmes)

Sherlock Holmes also had his share of human weaknesses such as smoking and drug addiction. His partner, the sensible, loyal Watson proved the ideal counterbalance to the highly strung genius of Holmes.

The success of Sherlock Holmes enabled Conan Doyle to retire from his medical profession and become a full-time writer. But, it was not the popular Sherlock Holmes stories which inspired him the most. He was more interested in writing serious historical novels and becoming known as a famous writer in this genre. However, his historical novels never brought him the same financial remuneration or fame as his Sherlock Holmes stories did.

After a while, Doyle became increasingly frustrated with the public’s obsession with Holmes, at a time when he was growing weary of the stories. Therefore, he decided to retire Holmes in 1893 by having him plunge into a ravine with his arch-enemy Professor Moriarty. Holmes hoped this would give him more time to write his ‘serious novels’ – but, much to his frustration, he struggled to escape the public’s perception of him as the creator of Holmes. In fact, it wasn’t uncommon for members of the public to equate Conan Doyle with Sherlock Holmes – much to his annoyance.

In 1900, Conan Doyle served in a field hospital in the Boer war. He also later published a pamphlet The War in South Africa: Its Cause and Conduct , which sought to justify British actions in the unpopular Boer war. For his services in the war, he was knighted, though undoubtedly his fame as the creator of Sherlock Holmes was also a factor.

In, 1906, his first wife, Louisa Hawkins, died after a long battle with Tuberculosis. It was a big blow to Conan Doyle who had moved to Switzerland to help her health.

After getting married to his second wife, Denise Steward a year later, he again was in the need for more money to finance a lavish new family home. Again, Doyle turned to his ever-profitable Holmes, securing a great deal with an American publisher for more Holmes stories. Thus, Holmes was resurrected, Conan Doyle cleverly wrote that Holmes had never died in the fall but cunningly escaped Moriarty and had gone into hiding from his enemies.

Conan Doyle’s most famous character was a man of great reason and science, so it was perhaps ironical that Conan Doyle was to become greatly interested in the new religion of spiritualism. A large part of spiritualism was the contacting of deceased relatives through seances. For many years, Conan Doyle had toyed with the ideas, but the traumatic years of the First World War (where he lost a brother and son) changed his outlook to that of a fervent believer. Conan Doyle became one of the chief proponents and public faces for spiritualism. Conan Doyle felt that this proof of life beyond death could give fresh impetus to religion.

“Religions are mostly petrified and decayed, overgrown with forms and choked with mysteries. We can prove that there is no need for this. All that is essential is both very simple and very sure.” ( The New Revelation 1918)

The success of Conan Doyle’s Holmes enabled him to pursue many different interests. As well, as researching spiritualism, Conan Doyle found time to fight miscarriages of justice such as the George Edalji case.

“I should dearly love that the world should be ever so little better for my presence. Even on this small stage, we have our two sides, and something might be done by throwing all one’s weight on the scale of breadth, tolerance, charity, temperance, peace, and kindliness to man and beast. We can’t all strike very big blows, and even the little ones count for something.”

Arthur Conan Doyle, Stark Munro Letters (1894)

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle ”, Oxford, UK. www.biographyonline.net. Published 25th June 2009. Last updated 15 February 2018.

The Doctor and the Detective: A Biography of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The Doctor and the Detective: A Biography of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle at Amazon

The Complete Sherlock Holmes

The Complete Sherlock Holmes at Amazon

Related pages

Biography of Arthur Conan Doyle, Author and Creator of Sherlock Holmes

Topical Press Agency / Hulton Archive / Getty Images

- Best Selling Authors

- Best Seller Reviews

- Book Clubs & Classes

- Classic Literature

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/McNamara-headshot-history1800s-5b7422c046e0fb00504dcf97.jpg)

Arthur Conan Doyle (May 22, 1859 - July 7, 1930) created one of the world's most famous characters, Sherlock Holmes. But in some ways, the Scottish-born author felt trapped by the runaway popularity of the fictional detective.

Over the course of a long writing career, Conan Doyle wrote other stories and books he believed to be superior to the tales and novels about Holmes. But the great detective turned into a sensation on both sides of the Atlantic, with the reading public clamoring for more plots involving Holmes, his sidekick Watson, and the deductive method.

As a result Conan Doyle, offered great sums of money by publishers, felt compelled to keep turning out stories about the great detective.

Fast Facts: Arthur Conan Doyle

Known For : British writer best known for his detective fiction featuring the character Sherlock Holmes.

Born : May 22, 1859

Died : July 7, 1930

Published Works : More than 50 titles featuring Sherlock Holmes, "The Lost World"

Spouse(s) : Louisa Hawkins (m. 1885; died 1906), Jean Leckie (m. 1907)

Children : Mary Louise, Arthur Alleyne Kingsley, Denis Percy Stewart, Adrian Malcolm, Jean Lena Annette

Notable Quote : "When the impossible has been eliminated, all that remains no matter how improbable is possible."

Early Life of Arthur Conan Doyle

Arthur Conan Doyle was born May 22, 1859, in Edinburgh, Scotland. The family's roots were in Ireland , which Arthur's father had left as a young man. The family surname had been Doyle, but as an adult Arthur preferred to use Conan Doyle as his surname.

Growing up as an avid reader, young Arthur, a Roman Catholic, attended Jesuit schools and a Jesuit university .

He attended medical school at Edinburgh University where he met a professor and surgeon, Dr. Joseph Bell, who was a model for Sherlock Holmes. Conan Doyle noticed how Dr. Bell was able to determine a great many facts about patients by asking seemingly simple questions, and the author later wrote about how Bell's manner had inspired the fictional detective.

Medical Career

In the late 1870s, Conan Doyle began writing magazine stories, and while pursuing his medical studies he had a yearning for adventure. At the age of 20, in 1880, he signed on to be the ship's surgeon of a whaling vessel headed to Antarctica. After a seven-month voyage, he returned to Edinburgh, finished his medical studies, and began the practice of medicine.

Conan Doyle continued to pursue writing and published in various London literary magazines throughout the 1880s . Influenced by a character of Edgar Allan Poe , the French detective M. Dupin, Conan Doyle wished to create his own detective character.

Sherlock Holmes

The character of Sherlock Holmes first appeared in a story, "A Study in Scarlet," which Conan Doyle published at the end of 1887 in a magazine, Beeton's Christmas Annual. It was reprinted as a book in 1888.

At the same time, Conan Doyle was conducting research for a historical novel, "Micah Clarke", which was set in the 17th century. He seemed to consider that his serious work, and the Sherlock Holmes character merely a challenging diversion to see if he could write a convincing detective story.

At some point, it occurred to Conan Doyle that the growing British magazine market was the perfect place to try an experiment in which a recurring character would turn up in new stories. He approached The Strand magazine with his idea, and in 1891 he began publishing new Sherlock Holmes stories.

The magazine stories became an enormous hit in England. The character of the detective who uses reasoning became a sensation. And the reading public eagerly awaited his newest adventures.

Illustrations for the stories were drawn by an artist, Sidney Paget, who actually added much to the public's conception of the character. It was Paget who drew Holmes wearing a deerstalker cap and a cape, details not mentioned in the original stories.

Arthur Conan Doyle Became Famous

With the success of the Holmes stories in The Strand magazine, Conan Doyle was suddenly an extremely famous writer. The magazine wanted more stories. But as the author didn't want to be overly associated with the now-famous detective, he demanded an outrageous sum of money.

Expecting to be relieved of the obligation to write more stories, Conan Doyle asked for 50 pounds per story. He was stunned when the magazine accepted, and he went on to keep writing about Sherlock Holmes.

While the public was crazy for Sherlock Holmes, Conan Doyle devised a way to be finished with writing the stories. He killed off the character by having him, and his nemesis Professor Moriarity, die while going over Reichenbach Falls in Switzerland . Conan Doyle's own mother, when told of the planned story, begged her son not to finish off Sherlock Holmes.

When the story in which Holmes died was published in December 1893, the British reading public was outraged. More than 20,000 people canceled their magazine subscriptions. And in London, it was reported that businessmen wore mourning crepe on their top hats.

Sherlock Holmes Was Revived

Arthur Conan Doyle, freed from Sherlock Holmes, wrote other stories and invented a character named Etienne Gerard, a soldier in Napoleon's army. The Gerard stories were popular, but not nearly as popular as Sherlock Holmes.

In 1897 Conan Doyle wrote a play about Holmes, and an actor, William Gillette, became a sensation playing the detective on Broadway in New York City . Gillette added another facet to the character, the famous meerschaum pipe.

A novel about Holmes, " The Hound of the Baskervilles ", was serialized in The Strand in 1901-02. Conan Doyle got around the death of Holmes by setting the story five years before his demise.

However, the demand for Holmes stories was so great that Conan Doyle essentially brought the great detective back to life by explaining that no one had actually seen Holmes go over the falls. The public, happy to have new tales, accepted the explanation.

Arthur Conan Doyle wrote about Sherlock Holmes until the 1920s.

In 1912 he published an adventure novel, " The Lost World ", about characters who find dinosaurs still living in a remote area of South America. The story of "The Lost World" has been adapted for film and television a number of times, and also served as an inspiration for such films as "King Kong" and "Jurassic Park".

Conan Doyle served as a doctor in a military hospital in South Africa during the Boer War in 1900 and wrote a book defending Britain's actions in the war. For his services he was knighted in 1902, becoming Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

The author died on July 7, 1930. His death was newsworthy enough to be reported on the front page of the next day's New York Times. A headline referred to him as "Spiritist, Novelist, and Creator of Famous Fiction Detective." As Conan Doyle believed in an afterlife, his family said they were awaiting a message from him after death.

The character of Sherlock Holmes, of course, lives on and appears in films right up to the present day.

- 'The Lost World,' Arthur Conan Doyle's Dinosaur Classic

- Understanding Mystery Writing

- Biography of Edgar Rice Burroughs, American Writer, Creator of Tarzan

- Notable Authors of the 19th Century

- Timeline from 1890 to 1900

- Classic Works of Literature for a 9th Grade Reading List

- Why “Anne of Green Gables” May Wind Up the Most Adapted Book in History

- Biography of Agatha Christie, English Mystery Writer

- Life of Wilkie Collins, Grandfather of the English Detective Novel

- Using the Word Pastiche

- Sole vs. Soul: How to Choose the Right Word

- What Is a Modifier in Grammar?

- Recommended Reads for High School Freshmen

- A.A. Milne Publishes Winnie-the-Pooh

- Michael Crichton Movies by Year

Arthur's parents, Mary Foley Doyle and Charles Altamont Doyle, had moved to Scotland from London, hoping that Charles could advance his career in architecture. Having inherited some measure of his family's artistic talent, Charles began with every hope of success, but never realized his dreams. Plagued by depression and alcoholism, Charles was a distant father and husband, becoming so detached from reality that he ended life in an asylum. With considerable charity, his son Arthur later said of him, "My father's life was full of the tragedy of unfulfilled powers and of underdeveloped gifts."

By this time, Charles Doyle had lost his job, and the family had difficulty paying the school fees. A lodger named Bryan Charles Waller became the family's protector, eventually supporting Mary, Charles, and their children completely.

Once at university, Conan Doyle found the work difficult and boring. He gained more amusement from playing sports, at which he excelled, than in listening to lectures in large, crowded lecture halls. More interesting than studying was describing his instructors' eccentric personalities. Among his teachers was the man Conan Doyle later acknowledged as his inspiration for Sherlock Holmes, Dr. Joseph Bell. Dr. Bell taught his students the importance of observation, using all the senses to obtain an accurate diagnosis. He enjoyed impressing students by guessing a person's profession from a few indications, through a combination of deductive and inductive reasoning, like Holmes. Although Bell's methods fascinated Conan Doyle, his cold indifference towards his patients repelled the young medical student. Some of this coldness found its way into Sherlock Holmes's character, especially in the early stories.

In 1886, Doyle finished the first Sherlock Holmes novella, A Study in Scarlet . After several rejections, he was forced to sell it outright for £25 for inclusion in the 1887 Beeton's Christmas Annual, a holiday collection that often sold out, but did not usually attract much attention in the national press. The work was reprinted in 1889 and many more times, but Conan Doyle never earned another penny from it. Sign of the Four , the second work to feature Holmes and Watson, also achieved a small, but by no means brilliant, success.

While writing the early Holmes stories, Doyle also began what he considered his most important work: chivalric, historical novels based on British history, primarily, Micah Clark, Sir Nigel, and The White Company . Although these novels were widely admired, none of them created the stir caused by the first series of short stories featuring Sherlock Holmes and John Watson that appeared in The Strand Magazine , starting in 1891. Despite their overwhelming success, Conan Doyle never suspected that these stories would be the foundation of his literary legacy.

After writing three series of twelve Holmes stories, receiving the unheard-of sum of £1000 for the last dozen, Conan Doyle was sick to death of the popular detective and decided to kill him off in the 1893 story, "The Final Problem." Conan Doyle considered the Holmes stories light fiction, good for earning money, but destined to be quickly forgotten, the literary equivalent of junk food. "I couldn't revive him if I would, at least not for years," he wrote to a friend who urged Holmes's resurrection, "for I have had such an overdose of him that I feel towards him as I do towards pâté de foie gras , of which I once ate too much, so that the name of it gives me a sickly feeling to this day." The vehement public reaction to Holmes's death must have shocked Conan Doyle. People wore black armbands and wrote him pleading--or threatening--letters. Still, it was nine years before he capitulated to public opinion and brought Holmes back. The third Holmes novel, The Hound of the Baskervilles , appeared in nine parts in The Strand Magazine during 1901-2, but it was presented as an old case from Watson's records, completed before Holmes's death. Conan Doyle did not make up his mind to resurrect Holmes until 1903, when he wrote "The Empty House." He continued, reluctantly, to produce Holmes stories until 1927, three years before his own death. Conan Doyle became an important public figure, twice standing (unsuccessfully) for Parliament. He was knighted for his efforts on behalf of the Boer War, both as the author of a persuasive, pro-war book and as a volunteer, caring for wounded British soldiers in the field. He even took on several real-life mysteries, using Holmes's methods and his own status as a famous author to free two unjustly imprisoned men. The First World War tore apart Conan Doyle's familiar world. Like so many others, he lost close family members to the conflict. Conan Doyle's brother-in-law and nephew died in combat, while the influenza pandemic took his brother Innes and his eldest son Kingsley, weakened by war wounds. During the war, he managed to have himself appointed as an observer for the Foreign Office, but he was kept away from the horrors of the western front for fear that he might reveal to the public things that the military would rather have kept quiet. Even Sherlock Holmes served England in the war. In the story that Conan Doyle intended to be the last Holmes outing, His Last Bow , published in 1916, Holmes outwits a German spy. Conan Doyle found a refuge from the horrors of the war, and he clung to it tenaciously. Starting in 1916, he publicly declared himself a spiritualist, and over the next few years he made spiritualism the center of his life, writing on the subject and traveling all over the world to advocate his beliefs. Never afraid to take an unpopular stand, Conan Doyle wrote a book in 1922 called The Coming of the Fairies , in which he defended the veracity of two young girls who claimed to have photographed each other playing with actual fairies and goblins.

Towards the end of their lives, long after Conan Doyle's death, the aged "girls" admitted to having used paper cutouts as stand-ins for the fairies. Interestingly, Conan Doyle's own Uncle Richard had invented, in his book illustrations, the typical representation of a fairy as a little girl with dragonfly wings and a gossamer gown. No matter how many times Conan Doyle was tricked by mediums later proven to be dishonest, he continued to believe in spiritualism. The famous American magician Harry Houdini made a project of trying to convince Conan Doyle of his error, but all he managed to do was ruin their friendship. Houdini saw spiritualism as cruel because it gave people false hope; Conan Doyle, who was already suffering from serious heart disease, wanted to believe that death was a grand new adventure. He fought his infirmity, trying to continue writing and traveling as before. He died at the age of 71, secure in his spiritualist beliefs.

Doctor, writer, believer in the supernatural--Conan Doyle's personality encompassed all these traits that contributed to the Sherlock Holmes stories we love to read today. Conan Doyle's fanciful imagination, combined with his scientific training, created ideas that have helped to shape the modern mystery and science fiction genres. One of the first to anticipate the dangers of submarines in warfare, he wrote a Sherlock Holmes story on the subject. His novel The Lost World is the ancestor of Jurassic Park and countless other films. Another of his stories, "The Ring of Thoth," was probably the plot source of the 1932 film The Mummy with Boris Karloff. An 1883 medical article called "Life and Death in the Blood," outlining the imaginary voyage of a microscopic observer through the human body, anticipated the main idea behind the film Fantastic Voyage . Conan Doyle's most long-lived idea, however, was Sherlock Holmes himself, who has continued to evolve in our time through the works of other writers and filmmakers, taking forms even his creator could never have imagined.

Conan Doyle wrote the Holmes stories quickly, never imagining that they would receive much scrutiny. If he forgot a date or fact from a previous story, he forged ahead without looking it up. This bad habit has resulted in some startling discrepancies. Was Watson wounded in the leg or the arm? How could Watson's deceased wife be on a visit to her mother's? Is Watson's given name "James" or "John"? To correct these and other inconsistencies, Sherlockians comb the "canon," or "sacred writings," for clues, seek secondary sources (inventing some themselves when all else fails), and write "scholarly" articles, using Holmes's methods to solve contradictions in the works or following clues to add new "facts" to Holmes's and Watson's biographies.

One favorite Sherlockian controversy centers on the "original" location of 221b Baker Street, a non-existent address in Conan Doyle's time. When Baker Street was renumbered during the 1920s, 221b was created on the block formerly called Upper Baker Street. Many faithful representations of the sitting room at 221b Baker Street have been constructed throughout the world. All contain the violin, the tobacco-holding Persian slipper, and other Holmesian accouterments mentioned in the stories.

- Inventors and Inventions

- Philosophers

- Film, TV, Theatre - Actors and Originators

- Playwrights

- Advertising

- Military History

- Politicians

- Publications

- Visual Arts

Arthur Conan Doyle - Creator of Sherlock Holmes

***TOO LONG***Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for A Study in Scarlet, the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson. The brilliant Sherlock Holmes is one of the great detectives of crime fiction and has inspired a cult following as well as many film and television interpretations. But he shone all the brighter when shedding light on a case for the benefit of the lower-wattage Watson.

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle KStJ DL (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for A Study in Scarlet, the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Holmes and Dr. Watson. The Sherlock Holmes stories are milestones in the field of crime fiction.

Doyle was a prolific writer; other than Holmes stories, his works include fantasy and science fiction stories about Professor Challenger and humorous stories about the Napoleonic soldier Brigadier Gerard, as well as plays, romances, poetry, non-fiction, and historical novels. One of Doyle's early short stories, "J. Habakuk Jephson's Statement" (1884), helped to popularise the mystery of the Mary Celeste.

Doyle is often referred to as "Sir Arthur Conan Doyle" or "Conan Doyle", implying that "Conan" is part of a compound surname rather than a middle name. His baptism entry in the register of St Mary's Cathedral, Edinburgh, gives "Arthur Ignatius Conan" as his given names and "Doyle" as his surname. It also names Michael Conan as his godfather. The catalogues of the British Library and the Library of Congress treat "Doyle" alone as his surname.

Steven Doyle, publisher of The Baker Street Journal, wrote: "Conan was Arthur's middle name. Shortly after he graduated from high school he began using Conan as a sort of surname. But technically his last name is simply 'Doyle'." When knighted, he was gazetted as Doyle, not under the compound Conan Doyle.

Doyle was born on 22 May 1859 at 11 Picardy Place, Edinburgh, Scotland. His father, Charles Altamont Doyle, was born in England, of Irish Catholic descent, and his mother, Mary (née Foley), was Irish Catholic. His parents married in 1855. In 1864 the family scattered because of Charles's growing alcoholism, and the children were temporarily housed across Edinburgh. Arthur lodged with Mary Burton, the aunt of a friend, at Liberton Bank House on Gilmerton Road, while studying at Newington Academy.

In 1867, the family came together again and lived in squalid tenement flats at 3 Sciennes Place. Doyle's father died in 1893, in the Crichton Royal, Dumfries, after many years of psychiatric illness. Beginning at an early age, throughout his life Doyle wrote letters to his mother, and many of them were preserved.

Supported by wealthy uncles, Doyle was sent to England, to the Jesuit preparatory school Hodder Place, Stonyhurst in Lancashire at the age of nine (1868–70). He then went on to Stonyhurst College, which he attended until 1875. While Doyle was not unhappy at Stonyhurst, he said he did not have any fond memories of it because the school was run on medieval principles: the only subjects covered were rudiments, rhetoric, Euclidean geometry, algebra and the classics. Doyle commented later in his life that this academic system could only be excused "on the plea that any exercise, however stupid in itself, forms a sort of mental dumbbell by which one can improve one's mind." He also found the school harsh, noting that, instead of compassion and warmth, it favoured the threat of corporal punishment and ritual humiliation.

From 1875 to 1876, he was educated at the Jesuit school Stella Matutina in Feldkirch, Austria. His family decided that he would spend a year there in order to perfect his German and broaden his academic horizons. He later rejected the Catholic faith and became an agnostic. One source attributed his drift away from religion to the time he spent in the less strict Austrian school. He also later became a spiritualist mystic.

Medical career

From 1876 to 1881, Doyle studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh Medical School; during this period he spent time working in Aston (then a town in Warwickshire, now part of Birmingham), Sheffield and Ruyton-XI-Towns, Shropshire. Also during this period, he studied practical botany at the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh. While studying, Doyle began writing short stories. His earliest extant fiction, "The Haunted Grange of Goresthorpe", was unsuccessfully submitted to Blackwood's Magazine. His first published piece, "The Mystery of Sasassa Valley", a story set in South Africa, was printed in Chambers's Edinburgh Journal on 6 September 1879. On 20 September 1879, he published his first academic article, "Gelsemium as a Poison" in the British Medical Journal, a study which The Daily Telegraph regarded as potentially useful in a 21st-century murder investigation.

Doyle was the doctor on the Greenland whaler Hope of Peterhead in 1880. On 11 July 1880, John Gray's Hope and David Gray's Eclipse met up with the Eira and Leigh Smith. The photographer W.J.A. Grant took a photograph aboard the Eira of Doyle along with Smith, the Gray brothers, and ship's surgeon William Neale, who were members of the Smith expedition. That expedition explored Franz Josef Land, and led to the naming, on 18 August, of Cape Flora, Bell Island, Nightingale Sound, Gratton ("Uncle Joe") Island, and Mabel Island.

After graduating with Bachelor of Medicine and Master of Surgery (M.B. C.M.) degrees from the University of Edinburgh in 1881, he was ship's surgeon on the SS Mayumba during a voyage to the West African coast. He completed his Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) degree (an advanced degree beyond the basic medical qualification in the UK) with a dissertation on tabes dorsalis in 1885.

In 1882, Doyle partnered with his former classmate George Turnavine Budd in a medical practice in Plymouth, but their relationship proved difficult, and Doyle soon left to set up an independent practice. Arriving in Portsmouth in June 1882, with less than £10 (£1100 in 2019) to his name, he set up a medical practice at 1 Bush Villas in Elm Grove, Southsea. The practice was not successful. While waiting for patients, Doyle returned to writing fiction.

Doyle was a staunch supporter of compulsory vaccination and wrote several articles advocating the practice and denouncing the views of anti-vaccinators.

In early 1891, Doyle embarked on the study of ophthalmology in Vienna. He had previously studied at the Portsmouth Eye Hospital in order to qualify to perform eye tests and prescribe glasses. Vienna had been suggested by his friend Vernon Morris as a place to spend six months and train to be an eye surgeon. But Doyle found it too difficult to understand the German medical terms being used in his classes in Vienna, and soon quit his studies there. For the rest of his two-month stay in Vienna, he pursued other activities, such as ice skating with his wife Louisa and drinking with Brinsley Richards of the London Times. He also wrote The Doings of Raffles Haw.

After visiting Venice and Milan, he spent a few days in Paris observing Edmund Landolt, an expert on diseases of the eye. Within three months of his departure for Vienna, Doyle returned to London. He opened a small office and consulting room at 2 Upper Wimpole Street, or 2 Devonshire Place as it was then. (There is today a Westminster City Council commemorative plaque over the front door.) He had no patients, according to his autobiography, and his efforts as an ophthalmologist were a failure.

Doyle struggled to find a publisher. His first work featuring Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, A Study in Scarlet, was written in three weeks when he was 27 and was accepted for publication by Ward Lock & Co on 20 November 1886, which gave Doyle £25 (equivalent to £2,900 in 2019) in exchange for all rights to the story. The piece appeared a year later in the Beeton's Christmas Annual and received good reviews in The Scotsman and the Glasgow Herald.

Holmes was partially modelled on Doyle's former university teacher Joseph Bell. In 1892, in a letter to Bell, Doyle wrote, "It is most certainly to you that I owe Sherlock Holmes ... round the centre of deduction and inference and observation which I have heard you inculcate I have tried to build up a man", and in his 1924 autobiography, he remarked, "It is no wonder that after the study of such a character [viz., Bell] I used and amplified his methods when in later life I tried to build up a scientific detective who solved cases on his own merits and not through the folly of the criminal."Robert Louis Stevenson was able to recognise the strong similarity between Joseph Bell and Sherlock Holmes: "My compliments on your very ingenious and very interesting adventures of Sherlock Holmes. ... can this be my old friend Joe Bell?" Other authors sometimes suggest additional influences—for instance, Edgar Allan Poe's character C. Auguste Dupin, who is mentioned, disparagingly, by Holmes in A Study in Scarlet. Dr. (John) Watson owes his surname, but not any other obvious characteristic, to a Portsmouth medical colleague of Doyle's, Dr. James Watson.

A sequel to A Study in Scarlet was commissioned, and The Sign of the Four appeared in Lippincott's Magazine in February 1890, under agreement with the Ward Lock company. Doyle felt grievously exploited by Ward Lock as an author new to the publishing world, and so, after this, he left them. Short stories featuring Sherlock Holmes were published in the Strand Magazine. Doyle wrote the first five Holmes short stories from his office at 2 Upper Wimpole Street (then known as Devonshire Place), which is now marked by a memorial plaque.

Doyle's attitude towards his most famous creation was ambivalent. In November 1891, he wrote to his mother: "I think of slaying Holmes, ... and winding him up for good and all. He takes my mind from better things." His mother responded, "You won't! You can't! You mustn't!" In an attempt to deflect publishers' demands for more Holmes stories, he raised his price to a level intended to discourage them, but found they were willing to pay even the large sums he asked. As a result, he became one of the best-paid authors of his time.

In December 1893, to dedicate more of his time to his historical novels, Doyle had Holmes and Professor Moriarty plunge to their deaths together down the Reichenbach Falls in the story "The Final Problem". Public outcry, however, led him to feature Holmes in 1901 in the novel The Hound of the Baskervilles. Holmes' fictional connection with the Reichenbach Falls is celebrated in the nearby town of Meiringen.

In 1903, Doyle published his first Holmes short story in ten years, "The Adventure of the Empty House", in which it was explained that only Moriarty had fallen, but since Holmes had other dangerous enemies—especially Colonel Sebastian Moran—he had arranged to make it look as if he too were dead. Holmes was ultimately featured in a total of 56 short stories—the last published in 1927—and four novels by Doyle, and has since appeared in many novels and stories by other authors.

Doyle's first novels were The Mystery of Cloomber, not published until 1888, and the unfinished Narrative of John Smith, published only posthumously, in 2011. He amassed a portfolio of short stories, including "The Captain of the Pole-Star" and "J. Habakuk Jephson's Statement", both inspired by Doyle's time at sea. The latter popularised the mystery of the Mary Celeste and added fictional details such as that the ship was found in perfect condition (it had actually taken on water by the time it was discovered), and that its boats remained on board (the single boat was in fact missing). These fictional details have come to dominate popular accounts of the incident, and Doyle's alternate spelling of the ship's name as the Marie Celeste has become more commonly used than the original spelling.

Between 1888 and 1906, Doyle wrote seven historical novels, which he and many critics regarded as his best work. He also wrote nine other novels, and—later in his career (1912–29)—five narratives (two of novel length) featuring the irascible scientist Professor Challenger. The Challenger stories include his best-known work after the Holmes oeuvre, The Lost World. His historical novels include The White Company and its prequel Sir Nigel, set in the Middle Ages. He was a prolific author of short stories, including two collections set in Napoleonic times and featuring the French character Brigadier Gerard.

Doyle's works for the stage include: Waterloo, which centres on the reminiscences of an English veteran of the Napoleonic Wars and features a character Gregory Brewster, written for Henry Irving; The House of Temperley, the plot of which reflects his abiding interest in boxing; The Speckled Band, adapted from his earlier short story "The Adventure of the Speckled Band"; and an 1893 collaboration with J. M. Barrie on the libretto of Jane Annie.

Sporting career

While living in Southsea, the seaside resort of Portsmouth, Doyle played football as a goalkeeper for Portsmouth Association Football Club, an amateur side, under the pseudonym A. C. Smith.

Doyle was a keen cricketer, and between 1899 and 1907 he played 10 first-class matches for the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC). He also played for the amateur cricket teams the Allahakbarries and the Authors XI alongside fellow writers J. M. Barrie, P. G. Wodehouse and A. A. Milne. His highest score, in 1902 against London County, was 43. He was an occasional bowler who took one first-class wicket, W. G. Grace, and wrote a poem about the achievement.

In 1901, Doyle was one of three judges for the world's first major bodybuilding competition, which was organized by the "Father of Bodybuilding", Eugen Sandow. The event was held in London's Royal Albert Hall. The other two judges were the sculptor Sir Charles Lawes-Wittewronge and Eugen Sandow himself.

Doyle was an amateur boxer. In 1909, he was invited to referee the James Jeffries–Jack Johnson heavyweight championship fight in Reno, Nevada. Doyle wrote: "I was much inclined to accept ... though my friends pictured me as winding up with a revolver at one ear and a razor at the other. However, the distance and my engagements presented a final bar."

Also a keen golfer, Doyle was elected captain of the Crowborough Beacon Golf Club in Sussex for 1910. He had moved to Little Windlesham house in Crowborough with Jean Leckie, his second wife, and resided there with his family from 1907 until his death in July 1930.

He entered the English Amateur billiards championship in 1913.

While living in Switzerland, Doyle became interested in skiing, which was relatively unknown in Switzerland at the time. He wrote an article, "An Alpine Pass on 'Ski'" for the December 1894 issue of The Strand Magazine, in which he described his experiences with skiing and the beautiful alpine scenery that could be seen in the process. The article popularized the activity and began the long association between Switzerland and skiing.

In 1885 Doyle married Louisa (sometimes called "Touie") Hawkins (1857–1906). She was the youngest daughter of J. Hawkins, of Minsterworth, Gloucestershire, and the sister of one of Doyle's patients. Louisa suffered from tuberculosis. In 1907, the year after Louisa's death, he married Jean Elizabeth Leckie (1874–1940). He had met and fallen in love with Jean in 1897, but had maintained a platonic relationship with her while his first wife was still alive, out of loyalty to her. Jean outlived him by ten years, and died in London.

Doyle fathered five children. He had two with his first wife: Mary Louise (1889–1976) and Arthur Alleyne Kingsley, known as Kingsley (1892–1918). He had an additional three with his second wife: Denis Percy Stewart (1909–1955), who became the second husband of Georgian Princess Nina Mdivani; Adrian Malcolm (1910–1970); and Jean Lena Annette (1912–1997). None of Doyle's five children had children of their own, so he has no living direct descendants.

Political campaigning

Doyle served as a volunteer doctor in the Langman Field Hospital at Bloemfontein between March and June 1900, during the Second Boer War in South Africa (1899–1902). Later that same year, he wrote a book on the war, The Great Boer War, as well as a short work titled The War in South Africa: Its Cause and Conduct, in which he responded to critics of the United Kingdom's role in that war, and argued that its role was justified. The latter work was widely translated, and Doyle believed it was the reason he was knighted (given the rank of Knight Bachelor) by King Edward VII in the 1902 Coronation Honours. (He received the accolade from the King in person at Buckingham Palace on 24 October of that year.)

He stood for Parliament twice as a Liberal Unionist: in 1900 in Edinburgh Central; and in 1906 in the Hawick Burghs. He received a respectable share of the vote, but was not elected. He served as a Deputy-Lieutenant of Surrey beginning in 1902, and was appointed a Knight of Grace of the Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem in 1903.

Doyle was a supporter of the campaign for the reform of the Congo Free State that was led by the journalist E. D. Morel and diplomat Roger Casement. In 1909 he wrote The Crime of the Congo, a long pamphlet in which he denounced the horrors of that colony. He became acquainted with Morel and Casement, and it is possible that, together with Bertram Fletcher Robinson, they inspired several characters that appear in his 1912 novel The Lost World. Later, after the Easter Rising, Casement was found guilty of treason against the Crown, and was sentenced to death. Doyle tried, unsuccessfully, to save him, arguing that Casement had been driven mad, and therefore should not be held responsible for his actions.

As the First World War loomed, and having been caught up in a growing public swell of Germanophobia, Doyle gave a public donation of 10 shillings to the anti-immigration British Brothers' League.

Doyle was also a fervent advocate of justice and personally investigated two closed cases, which led to two men being exonerated of the crimes of which they were accused. The first case, in 1906, involved a shy half-British, half-Indian lawyer named George Edalji, who had allegedly penned threatening letters and mutilated animals in Great Wyrley. Police were set on Edalji's conviction, even though the mutilations continued after their suspect was jailed. Apart from helping George Edalji, Doyle's work helped establish a way to correct other miscarriages of justice, as it was partially as a result of this case that the Court of Criminal Appeal was established in 1907.

The story of Doyle and Edalji was dramatised in an episode of the 1972 BBC television series, The Edwardians. In Nicholas Meyer's pastiche The West End Horror (1976), Holmes manages to help clear the name of a shy Parsi Indian character wronged by the English justice system. Edalji was of Parsi heritage on his father's side. The story was fictionalised in Julian Barnes's 2005 novel Arthur and George, which was adapted into a three-part drama by ITV in 2015.

The second case, that of Oscar Slater—a Jew of German origin who operated a gambling den and was convicted of bludgeoning an 82-year-old woman in Glasgow in 1908—excited Doyle's curiosity because of inconsistencies in the prosecution's case and a general sense that Slater was not guilty. He ended up paying most of the costs for Slater's successful 1928 appeal.

Freemasonry and spiritualism

Doyle had a longstanding interest in mystical subjects and remained fascinated by the idea of paranormal phenomena, even though the strength of his belief in their reality waxed and waned periodically over the years.

In 1887, in Southsea, influenced by Major-General Alfred Wilks Drayson, a member of the Portsmouth Literary and Philosophical Society, Doyle began a series of investigations into the possibility of psychic phenomena and attended about 20 seances, experiments in telepathy, and sittings with mediums. Writing to spiritualist journal Light that year, he declared himself to be a spiritualist, describing one particular event that had convinced him psychic phenomena were real. Also in 1887 (on 26 January), he was initiated as a Freemason at the Phoenix Lodge No. 257 in Southsea. (He resigned from the Lodge in 1889, returned to it in 1902, and resigned again in 1911.)

In 1889, he became a founding member of the Hampshire Society for Psychical Research; in 1893, he joined the London-based Society for Psychical Research; and in 1894, he collaborated with Sir Sidney Scott and Frank Podmore in a search for poltergeists in Devon.

Doyle and the spiritualist William Thomas Stead (before the latter was lost in the sinking of the Titanic) were led to believe that Julius and Agnes Zancig had genuine psychic powers, and they claimed publicly that the Zancigs used telepathy. However, in 1924, the Zancigs confessed that their mind reading act had been a trick; they published the secret code and all other details of the trick method they had used under the title "Our Secrets!!" in a London newspaper. Doyle also praised the psychic phenomena and spirit materializations that he believed had been produced by Eusapia Palladino and Mina Crandon, both of whom were also later exposed as frauds.

In 1916, at the height of the First World War, Doyle's belief in psychic phenomena was strengthened by what he took to be the psychic abilities of his children's nanny, Lily Loder Symonds. This and the constant drumbeat of wartime deaths inspired him with the idea that spiritualism was what he called a "New Revelation" sent by God to bring solace to the bereaved. He wrote a piece in Light magazine about his faith and began lecturing frequently on spiritualism. In 1918, he published his first spiritualist work, The New Revelation.

Some have mistakenly assumed that Doyle's turn to spiritualism was prompted by the death of his son Kingsley, but Doyle began presenting himself publicly as a spiritualist in 1916, and Kingsley died on 28 October 1918 (from pneumonia contracted during his convalescence after being seriously wounded in the 1916 Battle of the Somme). Nevertheless, the war-related deaths of many people who were close to him appears to have even further strengthened his long-held belief in life after death and spirit communication. Doyle's brother Brigadier-general Innes Doyle died, also from pneumonia, in February 1919. His two brothers-in-law (one of whom was E. W. Hornung, creator of the literary character Raffles), as well as his two nephews, also died shortly after the war. His second book on spiritualism, The Vital Message, appeared in 1919.

Doyle found solace in supporting spiritualism's ideas and the attempts of spiritualists to find proof of an existence beyond the grave. In particular, according to some, he favoured Christian Spiritualism and encouraged the Spiritualists' National Union to accept an eighth precept – that of following the teachings and example of Jesus of Nazareth. He was a member of the renowned supernaturalist organisation The Ghost Club.

In 1919, the magician P. T. Selbit staged a séance at his flat in Bloomsbury, which Doyle attended. Although some later claimed that Doyle had endorsed the apparent instances of clairvoyance at that séance as genuine, a contemporaneous report by the Sunday Express quoted Doyle as saying "I should have to see it again before passing a definite opinion on it" and "I have my doubts about the whole thing". In 1920, Doyle and the noted sceptic Joseph McCabe held a public debate at Queen's Hall in London, with Doyle taking the position that the claims of spiritualism were true. After the debate, McCabe published a booklet Is Spiritualism Based on Fraud?, in which he laid out evidence refuting Doyle's arguments and claimed that Doyle had been duped into believing in spiritualism through deliberate mediumship trickery.

Doyle also debated the psychiatrist Harold Dearden, who vehemently disagreed with Doyle's belief that many cases of diagnosed mental illness were the result of spirit possession.

In 1920, Doyle travelled to Australia and New Zealand on spiritualist missionary work, and over the next several years, until his death, he continued his mission, giving talks about his spiritualist conviction in Britain, Europe, and the United States.

Doyle wrote a novel The Land of Mist centered on spiritualist themes and featuring the character Professor Challenger. He also wrote many non-fiction spiritualist works. Perhaps his most famous of these was The Coming of the Fairies (1922), in which Doyle described his beliefs about the nature and existence of fairies and spirits, reproduced the five Cottingley Fairies photographs, asserted that those who suspected them being faked were wrong, and expressed his conviction that they were authentic. Decades later, the photos were definitively shown to have been faked, and their creators admitted to the fakery.

Doyle was friends for a time with the American magician Harry Houdini. Even though Houdini explained that his feats were based on illusion and trickery, Doyle was convinced that Houdini had supernatural powers and said as much in his work The Edge of the Unknown. Houdini's friend Bernard M. L. Ernst recounted a time when Houdini had performed an impressive trick at his home in Doyle's presence. Houdini had assured Doyle that the trick was pure illusion and had expressed the hope that this demonstration would persuade Doyle not to go around "endorsing phenomena" simply because he could think of no explanation for what he had seen other than supernatural power. However, according to Ernst, Doyle simply refused to believe that it had been a trick. Houdini became a prominent opponent of the spiritualist movement in the 1920s, after the death of his beloved mother. He insisted that spiritualist mediums employed trickery, and consistently exposed them as frauds. These differences between Houdini and Doyle eventually led to a bitter, public falling-out between them.

In 1922, the psychical researcher Harry Price accused the "spirit photographer" William Hope of fraud. Doyle defended Hope, but further evidence of trickery was obtained from other researchers. Doyle threatened to have Price evicted from the National Laboratory of Psychical Research and predicted that, if he persisted in writing what he called "sewage" about spiritualists, he would meet the same fate as Harry Houdini. Price wrote: "Arthur Conan Doyle and his friends abused me for years for exposing Hope." In response to the exposure of frauds that had been perpetrated by Hope and other spiritualists, Doyle led 84 members of the Society for Psychical Research to resign in protest from the society on the ground that they believed it was opposed to spiritualism.

Doyle's two-volume book The History of Spiritualism was published in 1926. W. Leslie Curnow, a spiritualist, contributed much research to the book. Later that year, Robert John Tillyard wrote a predominantly supportive review of it in the journal Nature. This review provoked controversy: Several other critics, notably A. A. Campbell Swinton, pointed out the evidence of fraud in mediumship, as well as Doyle's non-scientific approach to the subject. In 1927, Doyle gave a filmed interview, in which he spoke about Sherlock Holmes and spiritualism.

Doyle and the Piltdown Hoax

Richard Milner, an American historian of science, has presented a case that Doyle may have been the perpetrator of the Piltdown Man hoax of 1912, creating the counterfeit hominid fossil that fooled the scientific world for over 40 years. Milner noted that Doyle had a plausible motive—namely, revenge on the scientific establishment for debunking one of his favourite psychics—and said that The Lost World appeared to contain several clues referring cryptically to his having been involved in the hoax.Samuel Rosenberg's 1974 book Naked is the Best Disguise purports to explain how, throughout his writings, Doyle had provided overt clues to otherwise hidden or suppressed aspects of his way of thinking that seemed to support the idea that Doyle would be involved in such a hoax.

However, more recent research suggests that Doyle was not involved. In 2016, researchers at the Natural History Museum and Liverpool John Moores University analyzed DNA evidence showing that responsibility for the hoax lay with the amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson, who had originally "found" the remains. He had initially not been considered the likely perpetrator, because the hoax was seen as being too elaborate for him to have devised. However, the DNA evidence showed that a supposedly ancient tooth he had "discovered" in 1915 (at a different site) came from the same jaw as that of the Piltdown Man, suggesting that he had planted them both. That tooth, too, was later proven to have been planted as part of a hoax.

Dr Chris Stringer, an anthropologist from the Natural History Museum, was quoted as saying: "Conan Doyle was known to play golf at the Piltdown site and had even given Dawson a lift in his car to the area, but he was a public man and very busy[,] and it is very unlikely that he would have had the time [to create the hoax]. So there are some coincidences, but I think they are just coincidences. When you look at the fossil evidence[,] you can only associate Dawson with all the finds, and Dawson was known to be personally ambitious. He wanted professional recognition. He wanted to be a member of the Royal Society and he was after an MBE . He wanted people to stop seeing him as an amateur".

Another of Doyle's longstanding interests was architectural design. In 1895, when he commissioned an architect friend of his, Joseph Henry Ball, to build him a home, he played an active part in the design process. The home in which he lived from October 1897 to September 1907, known as Undershaw (near Hindhead, in Surrey), was used as a hotel and restaurant from 1924 until 2004, when it was bought by a developer and then stood empty while conservationists and Doyle fans fought to preserve it. In 2012, the High Court in London ruled in favor of those seeking to preserve the historic building, ordering that the redevelopment permission be quashed on the ground that it had not been obtained through proper procedures. The building was later approved to become part of Stepping Stones, a school for children with disabilities and special needs.

Doyle made his most ambitious foray into architecture in March 1912, while he was staying at the Lyndhurst Grand Hotel: He sketched the original designs for a third-storey extension and for an alteration of the front facade of the building. Work began later that year, and when it was finished, the building was a nearly exact manifestation of the plans Doyle had sketched. Superficial alterations have been subsequently made, but the essential structure is still clearly Doyle's.

In 1914, on a family trip to the Jasper National Park in Canada, he designed a golf course and ancillary buildings for a hotel. The plans were realised in full, but neither the golf course nor the buildings have survived.

In 1926, Doyle laid the foundation stone for a Spiritualist Temple in Camden, London. Of the building's total £600 construction costs, he provided £500.

Doyle was found clutching his chest in the hall of Windlesham Manor, his house in Crowborough, Sussex, on 7 July 1930. He died of a heart attack at the age of 71. His last words were directed toward his wife: "You are wonderful." At the time of his death, there was some controversy concerning his burial place, as he was avowedly not a Christian, considering himself a Spiritualist. He was first buried on 11 July 1930 in Windlesham rose garden.

He was later reinterred together with his wife in Minstead churchyard in the New Forest, Hampshire. Carved wooden tablets to his memory and to the memory of his wife, originally from the church at Minstead, are on display as part of a Sherlock Holmes exhibition at Portsmouth Museum. The epitaph on his gravestone in the churchyard reads, in part: "Steel true/Blade straight/Arthur Conan Doyle/Knight/Patriot, Physician and man of letters".

A statue honours Doyle at Crowborough Cross in Crowborough, where he lived for 23 years. There is a statue of Sherlock Holmes in Picardy Place, Edinburgh, close to the house where Doyle was born.

Arthur Conan Doyle has been portrayed by many actors, including:

Arthur Conan Doyle is the ostensible narrator of Ian Madden's short story "Cracks in an Edifice of Sheer Reason".

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle features as a recurring character in Pip Murphy's Christie and Agatha's Detective Agency series, including A Discovery Disappears and Of Mountains and Motors.

- Arthur Conan Doyle en.wikipedia.org

You might also like

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. A Biographical Introduction

Dr andrzej diniejko , d. litt.; contributing editor, poland.

[ Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Authors —> Arthur Conan Doyle —> Next ]

Introduction

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle is known all over the world as the creator of one of the most famous fictional characters in English literature, the master detective Sherlock Holmes, but he was much more than the originator of modern detective literature. He was a man of many talents and pursuits: a medical doctor, multi-talented sportsman, prolific and excellent storyteller, keen patriot and a staunch imperialist, as well as a campaigner against miscarriages of justice.

He tried his hand in many genres of fiction and poetry. He wrote detective stories, historical and social romances, political essays and an innumerable number of letters to the press, public figures, acquaintances and friends, to his adored mother and other family members. Last but not least, he was a formidable public speaker and a dedicated Spiritualist, who investigated and popularised supernatural phenomena. A Victorian to the bone, he cherished the ideals of duty, chivalry, honour and respectability.

The origin of the surname

Doyle had an ancient Irish surname, ranking twelfth in the list of the most common surnames in Ireland. It can be derived from the Gaelic Dub-Ghaill ('dark foreigner'), the name which the Celts gave to the Vikings, who began settling in Ireland more than 1,000 years ago, or from the Anglo-Norman surname of d'Oillys, who arrived in England with William the Conqueror and then settled in Ireland.

There is a controversy about the full name of the author of the Sherlock Holmes stories. He always signed himself: A. Conan Doyle. Whether Conan is a middle name or the first part of the compound surname is a matter of dispute among Doylists. The entry in the register of baptisms of St. Mary's Cathedral in Edinburgh gives 'Arthur Ignatius Conan' as his Christian names, and 'Doyle' as his surname.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle as a child, with his father Charles Altamond (Adcock 96).

The Doyle family originated in Ireland and were dedicated Roman Catholics. Arthur Conan Doyle's grandfather, John Doyle (c. 1797-1868), a tailor, was born in Dublin into a devoutly Catholic family. All John's siblings entered Catholic religious orders, but John, who exhibited artistic talents, decided to become a painter. In 1820, he married Marianne Conan, a daughter of a Dublin's tailor. In c. 1822, John and Mary Doyle moved to London with their baby daughter and rented a house in Soho, which was inhabited by artists and writers. John wanted to become a portrait painter, but soon he gained fame as a political cartoonist under the pseudonym of HB. In 1833, he moved with his wife and children to a large house near Hyde Park at 17 Cambridge Terrace, where he subsequently entertained notable people including Sir Walter Scott, Charles Dickens, Benjamin Disraeli, William Makepeace Thackeray, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Millais, and Edwin Lanseer.

In 1832, Charles Altamont Doyle, Sir Arthur's father, was born. He grew up with one sister and three brothers. All his brothers made splendid careers: James William Edmund (1822-1892) was a historian and history illustrator; Richard (1824-1883) became a Punch cartoonist like his father; and Henry Edmund (1827-1892) became an art critic and a painter. In 1869, he was appointed Director of the National Gallery of Ireland.

Charles (1832-1893), Arthur's father, was not as successful as his elder brothers. Although he exhibited an original artistic talent, he was not able to earn a living from his paintings. At the age of 17, he moved to Edinburgh, Scotland, and got the job of a clerk in the Office of Works as an architectural draftsman. He rented lodgings in the New Town, a central area of Edinburgh, in a house owned by a Roman Catholic widow Catherine Foley. In 1855, he married his landlady's daughter, Mary Josephine (1837-1921), aged seventeen, with whom he had nine children, seven of whom survived infancy.

Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle was born on May 22, 1859, at 11 Picardy Place, Edinburgh. He was baptised two days later in nearby St. Mary's Roman Catholic Church. Arthur was raised in a dysfunctional family because his father, an impecunious artist, was neurotic and could hardly support the family with a clerk's meagre salary. He developed a serious drinking problem, which eventually brought him to a mental asylum in 1881. Arthur's mother was a strong-minded Irishwoman, who traced her ancestry to the Plantagenets. She held the family together and carried the burden of running the household and raising the children. In his Memories and Adventures Conan Doyle writes that his boyhood in Edinburgh was

Spartan at home and more Spartan at the Edinburgh school where a tawse-brandishing schoolmaster of the old type made our young living miserable. From the age of seven to nine I suffered under this pock-marked one-eyed rascal who might have stepped from the pages of Dickens. [11]

Arthur's mother, who knew well contemporary English and French authors, was a masterful storyteller, and she inspired her son to take interest in history and literature. She exerted a strong influence on his future career. She told him stories of their family ancient aristocratic roots. At the age of about five Arthur wrote his first story, which had only thirty-six words. It was about a Bengal tiger and a hunter.

At the age of seven Arthur began his education at Newington Academy in Edinburgh. Then thanks to his mother and the financial help of his uncles, particularly, Michael Conan, a Paris correspondent for the Art Journal , Arthur received good education. First, he was sent for a year to Hodder, a prep school which prepared for a prestigious Jesuit school, Stonyhurst College, in Lancashire, which Arthur started in autumn 1870. As Andrew Lykett writes:

Stonyurst was conservative and ultra-montane. This meant that its Rector or Head, Father Edward Ignatius Purbrick, followed a firm papal line in seeking to stem the tide of materialism in post- Darwinian Britain. [Lycett 32]

Arthur did not like the strict discipline and excessive religious instruction which the Jesuits had imposed on pupils. He was soon disillusioned with the Christian faith and when he was leaving the school he became almost an agnostic. While at Stonyhurst College, Arthur edited a school paper called Wasp and next the Stonyhurst Figaro , in which he revealed his talent as a future story writer. He also became a keen sportsman. In his later life he played cricket, rugby, football and golf, and was a cross-country skier.

After passing the London Matriculation Examination at Stonyhurst, Arthur spent a year in a Jesuit grammar school, Stella Matutina, in Feldkirch, Austria, where he was to learn German. He did not speak much German because he was surrounded by other English boys, but he discovered the short stories of Edgar Allan Poe, such as “The Gold Bug” and “The Murder in the Rue Morgue,” which later exerted a great influence on his detective fiction. At Feldkirch he also edited a student paper, the Feldkirch Gazette , which carried the motto “Fear not, and put it in print.” However, when he wrote an editorial criticising the Jesuit teachers' custom of censoring the boys' letters, the paper was shut down. Arthur's uncle, Michael Conan, a famous journalist, encouraged him to write, but he did not take this idea seriously at that time. (Pascal 18)

As a young boy Arthur was an avid reader, and one of his most favourite books was Sir Walter Scott's Ivanhoe . His other early readings included the novels of Robert Michael Ballantyne, Mayne Reid, James Fenimore Cooper, and Jules Verne. He spent much of his spare time reading, and once he borrowed so many books from the local library that, as he recalls in Memories and Adventures , a special meeting of a library committee was held in his honour, at which a bye-law was passed that no subscriber should be permitted to change his book more than three times a day. (Pascal 13)

In 1876, Arthur Conan Doyle began to study medicine at his mother's suggestion at the University of Edinburgh, which had been one of the best medical schools at that time. He met Dr. Joseph Bell (1837-1911), the famous lecturer and an expert in the use of deductive reasoning, who inspired the character of Sherlock Holmes, and the physiologist, Professor William Rutherford (1839-1899), a model for Professor Challenger. He also studied under Sir Robert Christison (1797-1882), one of the founding fathers of modern toxicology. (Harris 449)

During his medical studies, Arthur desperately tried to earn money for his living and to support his family. 1879, he worked as a medical assistant to Doctor Hoare in the town of Aston (now a district of Birmingham); next he worked in Sheffield and in Ruyton-XI-Towns, Shropshire. As a student he began writing short stories to earn some extra money. His earliest fiction, “The Haunted Grange of Goresthorphe,” was rejected by Blackwood's Magazine , but The “Mystery of the Sasassa Valley” was accepted for publication by Chambers Journal . He also published a scientific article, “Gelseminum as a Poison” in the British Medical Journal .

In 1880, Conan Doyle took a break from his studies and went on a daring six-month sea voyage to the Arctic on the whaling ship Hope. All British whale ships had to carry a surgeon, even if he was a 20 year-old medical student. During the voyage Doyle wrote a fascinating diary which was published recently. This voyage inspired him to write the story, “The Captain of the Pole Star.”

Medical profession and part-time authorship

Finally, in 1881, Conan Doyle passed qualifying examinations and settled in the Portsmouth suburb of Southsea in the next year to begin his own medical practice. As a keen sportsman, he joined the Southsea Bowling Club and the North End Cricket Club, and started playing rugby. He also joined the Literary and Scientific Society. Soon he found out that he was not satisfied with his medical career and decided to try his hand in writing fiction. From a young age he found pleasure in writing letters and articles and, finally, composing short stories.

In Southsea, Doyle, aged 23, wrote articles and short stories for London Society , All the Year Round , Temple Bar , Lancet , and The British Journal of Photography . He also wrote his first novel, The Narrative of John Smith . Its manuscript was lost in the mail on its way to the publisher. Although not good fiction, the novel provides a fascinating insight into the young writer's mind. It was published in 2011.

This early novel is about a middle-aged man who is stricken with gout and confined to his bed for a week. He attempts to write a book, and expounds his views on topics such as medicine, religion, literature and interior design. Many of the opinions reflect the author's outlook, e.g. his belief in the importance of science and medicine, and his scepticism about religious dogma.

In the 1880s Conan Doyle continued his private medical practice at Southsea, which turned out to be far from prosperous, and published fiction in various magazines. In 1886, he wrote a novella, A Study in Scarlet , which introduced the character of Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson. Because of its brevity it was not published as a separate book, but was included in Beeton's Christmas Annual in the following year. The Annual was not very popular and Doyle decided to write historical romances instead of detective fiction.

Conan Doyle often wrote to his mother about his longing to have a wife. Eventually, in 1885, he married Louise 'Toulie' Hawkins, whom he had met while treating her terminally ill brother Jack. Surprisingly, instead of going on a honeymoon with his young wife, he went on a tour of Ireland with the Stonyhurst Wanderers, the school's old boys cricket team. Four years later Arthur and Louise had their first child, Mary, and in 1892 their second child, Arthur, known as Kingsley.

In 1890, Conan Doyle studied briefly ophthalmology in Vienna. He then visited the Hygiene Institute in Berlin, where Robert Koch's cure for tuberculosis was being tested, and reported on the cure, first in a letter to the Daily Telegraph , and next in an article “Dr Koch and his Cure,” published in the Review of the Reviews . Although he had some doubts about the curative properties of the new procedure, he was impressed by Koch himself as “a model of scientist as hero.” (Kerr 84)

After return to England, Conan Doyle moved to London with his wife and daughter to start practice as an eye specialist at 2 Upper Wimpole Street. However, as he wrote in his Memories and Adventures , “not one single patient had entered the threshold of my room.” (96) Having no patients he had plenty of time to reconsider his career, and eventually, he decided to undergo a significant metamorphosis from doctor to writer (Kerr 91). In August, Doyle decided to give up medicine and make his living as a full-time professional writer. He next moved with his family to Tennison Road in South Norwood to concentrate only on writing. He published the first six “Adventures of Sherlock Holmes” in the Strand Magazine , and in 1890, the second Sherlock Holmes novel, The Sign of the Four , in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine . When the stories were published in book form as The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1892), “the Baker Street mania finally swept the public. By then Conan Doyle had launched himself as a full-time professional writer.” (Dirda 12)

Life at Undershaw and Windlesham

In 1893, Louise was diagnosed with tuberculosis. During the first years of the illness, the Doyles spent much time in Switzerland, hoping that local climate would help her. While in Switzerland Conan Doyle practised winter sports and became the first British to cross the Alpine pass in snow shoes. After return from Switzerland to London, Conan Doyle met the novelist Grant Allen at luncheon, who told him that he had also suffered from consumption and that he had found the climate of Surrey beneficial for his health. Doyle rushed to Hindhead, the highest village in Surrey, with buildings at between 185 and 246 metres above sea level. He immediately bought a plot of ground, and commissioned a house to be built before leaving with his wife for Egypt in the autumn of 1895. The house, called Undershaw, which was designed for rest and recuperation of his wife, was ready in 1897.