What We Offer

With a comprehensive suite of qualitative and quantitative capabilities and 55 years of experience in the industry, Sago powers insights through adaptive solutions.

- Recruitment

- Communities

- Methodify® Automated research

- QualBoard® Digital Discussions

- QualMeeting® Digital Interviews

- Global Qualitative

- Global Quantitative

- In-Person Facilities

- Research Consulting

- Europe Solutions

- Neuromarketing Tools

- Trial & Jury Consulting

Who We Serve

Form deeper customer connections and make the process of answering your business questions easier. Sago delivers unparalleled access to the audiences you need through adaptive solutions and a consultative approach.

- Consumer Packaged Goods

- Financial Services

- Media Technology

- Medical Device Manufacturing

- Marketing Research

With a 55-year legacy of impact, Sago has proven we have what it takes to be a long-standing industry leader and partner. We continually advance our range of expertise to provide our clients with the highest level of confidence.

- Global Offices

- Partnerships & Certifications

- News & Media

- Researcher Events

Sago Announces Launch of Sago Health to Elevate Healthcare Research

Sago Launches AI Video Summaries on QualBoard to Streamline Data Synthesis

Sago Executive Chairman Steve Schlesinger to Receive Quirk’s Lifetime Achievement Award

Drop into your new favorite insights rabbit hole and explore content created by the leading minds in market research.

- Case Studies

- Knowledge Kit

How Connecting with Gen C Can Help Your Brand Grow

Digital Detox: How Different Generations Navigate Social Media Breaks

Get in touch

- Account Logins

Different Types of Sampling Techniques in Qualitative Research

- Resources , Blog

Key Takeaways:

- Sampling techniques in qualitative research include purposive, convenience, snowball, and theoretical sampling.

- Choosing the right sampling technique significantly impacts the accuracy and reliability of the research results.

- It’s crucial to consider the potential impact on the bias, sample diversity, and generalizability when choosing a sampling technique for your qualitative research.

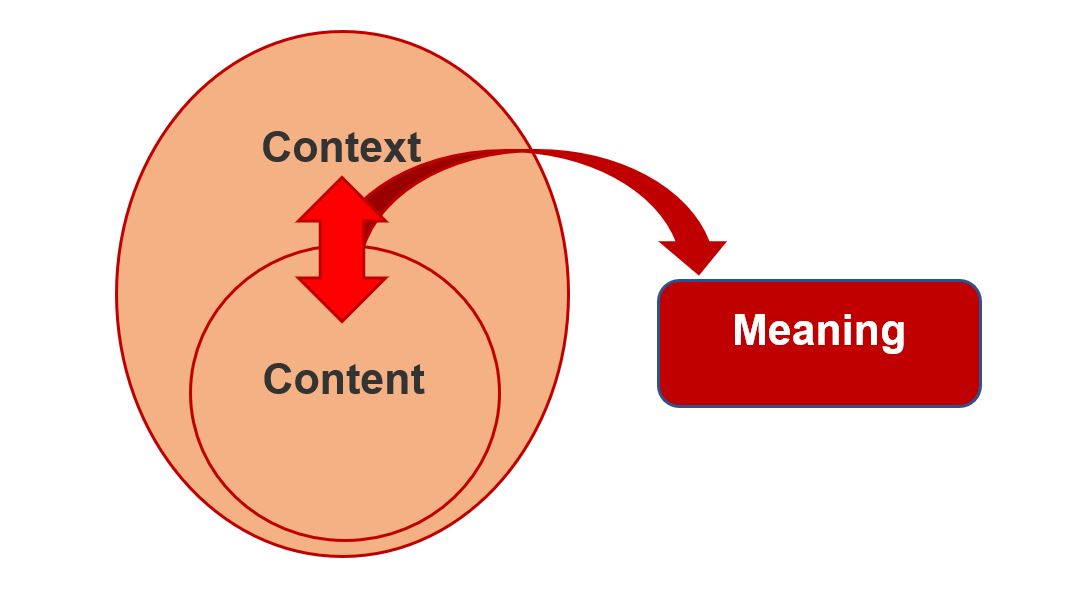

Qualitative research seeks to understand social phenomena from the perspective of those experiencing them. It involves collecting non-numerical data such as interviews, observations, and written documents to gain insights into human experiences, attitudes, and behaviors. While qualitative research can provide rich and nuanced insights, the accuracy and generalizability of findings depend on the quality of the sampling process. Sampling is a critical component of qualitative research as it involves selecting a group of participants who can provide valuable insights into the research questions.

This article explores different types of sampling techniques used in qualitative research. First, we’ll provide a comprehensive overview of four standard sampling techniques used in qualitative research. and then compare and contrast these techniques to provide guidance on choosing the most appropriate method for a particular study. Additionally, you’ll find best practices for sampling and learn about ethical considerations researchers need to consider in selecting a sample. Overall, this article aims to help researchers conduct effective and high-quality sampling in qualitative research.

In this Article:

- Purposive Sampling

- Convenience Sampling

- Snowball Sampling

- Theoretical Sampling

Factors to Consider When Choosing a Sampling Technique

Practical approaches to sampling: recommended practices, final thoughts, get expert guidance on your sample needs.

Want expert input on the best sampling technique for your qualitative research project? Book a consultation for trusted advice.

Request a consultation

4 Types of Sampling Techniques and Their Applications

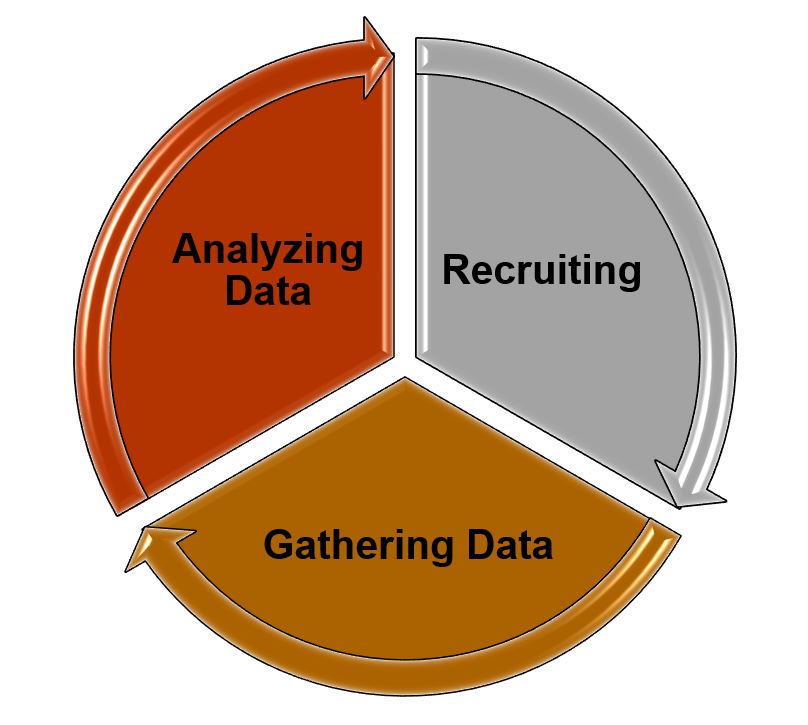

Sampling is a crucial aspect of qualitative research as it determines the representativeness and credibility of the data collected. Several sampling techniques are used in qualitative research, each with strengths and weaknesses. In this section, let’s explore four standard sampling techniques used in qualitative research: purposive sampling, convenience sampling, snowball sampling, and theoretical sampling. We’ll break down the definition of each technique, when to use it, and its advantages and disadvantages.

1. Purposive Sampling

Purposive sampling, or judgmental sampling, is a non-probability sampling technique commonly used in qualitative research. In purposive sampling, researchers intentionally select participants with specific characteristics or unique experiences related to the research question. The goal is to identify and recruit participants who can provide rich and diverse data to enhance the research findings.

Purposive sampling is used when researchers seek to identify individuals or groups with particular knowledge, skills, or experiences relevant to the research question. For instance, in a study examining the experiences of cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, purposive sampling may be used to recruit participants who have undergone chemotherapy in the past year. Researchers can better understand the phenomenon under investigation by selecting individuals with relevant backgrounds.

Purposive Sampling: Strengths and Weaknesses

Purposive sampling is a powerful tool for researchers seeking to select participants who can provide valuable insight into their research question. This method is advantageous when studying groups with technical characteristics or experiences where a random selection of participants may yield different results.

One of the main advantages of purposive sampling is the ability to improve the quality and accuracy of data collected by selecting participants most relevant to the research question. This approach also enables researchers to collect data from diverse participants with unique perspectives and experiences related to the research question.

However, researchers should also be aware of potential bias when using purposive sampling. The researcher’s judgment may influence the selection of participants, resulting in a biased sample that does not accurately represent the broader population. Another disadvantage is that purposive sampling may not be representative of the more general population, which limits the generalizability of the findings. To guarantee the accuracy and dependability of data obtained through purposive sampling, researchers must provide a clear and transparent justification of their selection criteria and sampling approach. This entails outlining the specific characteristics or experiences required for participants to be included in the study and explaining the rationale behind these criteria. This level of transparency not only helps readers to evaluate the validity of the findings, but also enhances the replicability of the research.

2. Convenience Sampling

When time and resources are limited, researchers may opt for convenience sampling as a quick and cost-effective way to recruit participants. In this non-probability sampling technique, participants are selected based on their accessibility and willingness to participate rather than their suitability for the research question. Qualitative research often uses this approach to generate various perspectives and experiences.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, convenience sampling was a valuable method for researchers to collect data quickly and efficiently from participants who were easily accessible and willing to participate. For example, in a study examining the experiences of university students during the pandemic, convenience sampling allowed researchers to recruit students who were available and willing to share their experiences quickly. While the pandemic may be over, convenience sampling during this time highlights its value in urgent situations where time and resources are limited.

Convenience Sampling: Strengths and Weaknesses

Convenience sampling offers several advantages to researchers, including its ease of implementation and cost-effectiveness. This technique allows researchers to quickly and efficiently recruit participants without spending time and resources identifying and contacting potential participants. Furthermore, convenience sampling can result in a diverse pool of participants, as individuals from various backgrounds and experiences may be more likely to participate.

While convenience sampling has the advantage of being efficient, researchers need to acknowledge its limitations. One of the primary drawbacks of convenience sampling is that it is susceptible to selection bias. Participants who are more easily accessible may not be representative of the broader population, which can limit the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, convenience sampling may lead to issues with the reliability of the results, as it may not be possible to replicate the study using the same sample or a similar one.

To mitigate these limitations, researchers should carefully define the population of interest and ensure the sample is drawn from that population. For instance, if a study is investigating the experiences of individuals with a particular medical condition, researchers can recruit participants from specialized clinics or support groups for that condition. Researchers can also use statistical techniques such as stratified sampling or weighting to adjust for potential biases in the sample.

3. Snowball Sampling

Snowball sampling, also called referral sampling, is a unique approach researchers use to recruit participants in qualitative research. The technique involves identifying a few initial participants who meet the eligibility criteria and asking them to refer others they know who also fit the requirements. The sample size grows as referrals are added, creating a chain-like structure.

Snowball sampling enables researchers to reach out to individuals who may be hard to locate through traditional sampling methods, such as members of marginalized or hidden communities. For instance, in a study examining the experiences of undocumented immigrants, snowball sampling may be used to identify and recruit participants through referrals from other undocumented immigrants.

Snowball Sampling: Strengths and Weaknesses

Snowball sampling can produce in-depth and detailed data from participants with common characteristics or experiences. Since referrals are made within a network of individuals who share similarities, researchers can gain deep insights into a specific group’s attitudes, behaviors, and perspectives.

4. Theoretical Sampling

Theoretical sampling is a sophisticated and strategic technique that can help researchers develop more in-depth and nuanced theories from their data. Instead of selecting participants based on convenience or accessibility, researchers using theoretical sampling choose participants based on their potential to contribute to the emerging themes and concepts in the data. This approach allows researchers to refine their research question and theory based on the data they collect rather than forcing their data to fit a preconceived idea.

Theoretical sampling is used when researchers conduct grounded theory research and have developed an initial theory or conceptual framework. In a study examining cancer survivors’ experiences, for example, theoretical sampling may be used to identify and recruit participants who can provide new insights into the coping strategies of survivors.

Theoretical Sampling: Strengths and Weaknesses

One of the significant advantages of theoretical sampling is that it allows researchers to refine their research question and theory based on emerging data. This means the research can be highly targeted and focused, leading to a deeper understanding of the phenomenon being studied. Additionally, theoretical sampling can generate rich and in-depth data, as participants are selected based on their potential to provide new insights into the research question.

Participants are selected based on their perceived ability to offer new perspectives on the research question. This means specific perspectives or experiences may be overrepresented in the sample, leading to an incomplete understanding of the phenomenon being studied. Additionally, theoretical sampling can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, as researchers must continuously analyze the data and recruit new participants.

To mitigate the potential for bias, researchers can take several steps. One way to reduce bias is to use a diverse team of researchers to analyze the data and make participant selection decisions. Having multiple perspectives and backgrounds can help prevent researchers from unconsciously selecting participants who fit their preconceived notions or biases.

Another solution would be to use reflexive sampling. Reflexive sampling involves selecting participants aware of the research process and provides insights into how their biases and experiences may influence their perspectives. By including participants who are reflexive about their subjectivity, researchers can generate more nuanced and self-aware findings.

Choosing the proper sampling technique is one of the most critical decisions a researcher makes when conducting a study. The preferred method can significantly impact the accuracy and reliability of the research results.

For instance, purposive sampling provides a more targeted and specific sample, which helps to answer research questions related to that particular population or phenomenon. However, this approach may also introduce bias by limiting the diversity of the sample.

Conversely, convenience sampling may offer a more diverse sample regarding demographics and backgrounds but may also introduce bias by selecting more willing or available participants.

Snowball sampling may help study hard-to-reach populations, but it can also limit the sample’s diversity as participants are selected based on their connections to existing participants.

Theoretical sampling may offer an opportunity to refine the research question and theory based on emerging data, but it can also be time-consuming and resource-intensive.

Additionally, the choice of sampling technique can impact the generalizability of the research findings. Therefore, it’s crucial to consider the potential impact on the bias, sample diversity, and generalizability when choosing a sampling technique. By doing so, researchers can select the most appropriate method for their research question and ensure the validity and reliability of their findings.

Tips for Selecting Participants

When selecting participants for a qualitative research study, it is crucial to consider the research question and the purpose of the study. In addition, researchers should identify the specific characteristics or criteria they seek in their sample and select participants accordingly.

One helpful tip for selecting participants is to use a pre-screening process to ensure potential participants meet the criteria for inclusion in the study. Another technique is using multiple recruitment methods to ensure the sample is diverse and representative of the studied population.

Ensuring Diversity in Samples

Diversity in the sample is important to ensure the study’s findings apply to a wide range of individuals and situations. One way to ensure diversity is to use stratified sampling, which involves dividing the population into subgroups and selecting participants from each subset. This helps establish that the sample is representative of the larger population.

Maintaining Ethical Considerations

When selecting participants for a qualitative research study, it is essential to ensure ethical considerations are taken into account. Researchers must ensure participants are fully informed about the study and provide their voluntary consent to participate. They must also ensure participants understand their rights and that their confidentiality and privacy will be protected.

A qualitative research study’s success hinges on its sampling technique’s effectiveness. The choice of sampling technique must be guided by the research question, the population being studied, and the purpose of the study. Whether purposive, convenience, snowball, or theoretical sampling, the primary goal is to ensure the validity and reliability of the study’s findings.

By thoughtfully weighing the pros and cons of each sampling technique, researchers can make informed decisions that lead to more reliable and accurate results. In conclusion, carefully selecting a sampling technique is integral to the success of a qualitative research study, and a thorough understanding of the available options can make all the difference in achieving high-quality research outcomes.

If you’re interested in improving your research and sampling methods, Sago offers a variety of solutions. Our qualitative research platforms, such as QualBoard and QualMeeting, can assist you in conducting research studies with precision and efficiency. Our robust global panel and recruitment options help you reach the right people. We also offer qualitative and quantitative research services to meet your research needs. Contact us today to learn more about how we can help improve your research outcomes.

Find the Right Sample for Your Qualitative Research

Trust our team to recruit the participants you need using the appropriate techniques. Book a consultation with our team to get started .

Navigating the Dynamic Future of Qualitative Research

Building Trust Through Inclusive Healthcare Research Recruitment

The Swing Voter Project Wisconsin: March 2024

The Deciders February 2024: African American voters in North Carolina

OnDemand: Moderator Minutes: Maximizing Efficiency with QualBoard – Streamline Your Projects with Support & AI

2024 Trends in Research: Fact or Fiction?

The Swing Voter Project in Michigan – February 2024

OnDemand: 5 Steps to High-Quality Data: Mitigating the Challenges of Data Quality in Quantitative Research

Take a deep dive into your favorite market research topics

How can we help support you and your research needs?

BEFORE YOU GO

Have you considered how to harness AI in your research process? Check out our on-demand webinar for everything you need to know

Chapter 5. Sampling

Introduction.

Most Americans will experience unemployment at some point in their lives. Sarah Damaske ( 2021 ) was interested in learning about how men and women experience unemployment differently. To answer this question, she interviewed unemployed people. After conducting a “pilot study” with twenty interviewees, she realized she was also interested in finding out how working-class and middle-class persons experienced unemployment differently. She found one hundred persons through local unemployment offices. She purposefully selected a roughly equal number of men and women and working-class and middle-class persons for the study. This would allow her to make the kinds of comparisons she was interested in. She further refined her selection of persons to interview:

I decided that I needed to be able to focus my attention on gender and class; therefore, I interviewed only people born between 1962 and 1987 (ages 28–52, the prime working and child-rearing years), those who worked full-time before their job loss, those who experienced an involuntary job loss during the past year, and those who did not lose a job for cause (e.g., were not fired because of their behavior at work). ( 244 )

The people she ultimately interviewed compose her sample. They represent (“sample”) the larger population of the involuntarily unemployed. This “theoretically informed stratified sampling design” allowed Damaske “to achieve relatively equal distribution of participation across gender and class,” but it came with some limitations. For one, the unemployment centers were located in primarily White areas of the country, so there were very few persons of color interviewed. Qualitative researchers must make these kinds of decisions all the time—who to include and who not to include. There is never an absolutely correct decision, as the choice is linked to the particular research question posed by the particular researcher, although some sampling choices are more compelling than others. In this case, Damaske made the choice to foreground both gender and class rather than compare all middle-class men and women or women of color from different class positions or just talk to White men. She leaves the door open for other researchers to sample differently. Because science is a collective enterprise, it is most likely someone will be inspired to conduct a similar study as Damaske’s but with an entirely different sample.

This chapter is all about sampling. After you have developed a research question and have a general idea of how you will collect data (observations or interviews), how do you go about actually finding people and sites to study? Although there is no “correct number” of people to interview, the sample should follow the research question and research design. You might remember studying sampling in a quantitative research course. Sampling is important here too, but it works a bit differently. Unlike quantitative research, qualitative research involves nonprobability sampling. This chapter explains why this is so and what qualities instead make a good sample for qualitative research.

Quick Terms Refresher

- The population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about.

- The sample is the specific group of individuals that you will collect data from.

- Sampling frame is the actual list of individuals that the sample will be drawn from. Ideally, it should include the entire target population (and nobody who is not part of that population).

- Sample size is how many individuals (or units) are included in your sample.

The “Who” of Your Research Study

After you have turned your general research interest into an actual research question and identified an approach you want to take to answer that question, you will need to specify the people you will be interviewing or observing. In most qualitative research, the objects of your study will indeed be people. In some cases, however, your objects might be content left by people (e.g., diaries, yearbooks, photographs) or documents (official or unofficial) or even institutions (e.g., schools, medical centers) and locations (e.g., nation-states, cities). Chances are, whatever “people, places, or things” are the objects of your study, you will not really be able to talk to, observe, or follow every single individual/object of the entire population of interest. You will need to create a sample of the population . Sampling in qualitative research has different purposes and goals than sampling in quantitative research. Sampling in both allows you to say something of interest about a population without having to include the entire population in your sample.

We begin this chapter with the case of a population of interest composed of actual people. After we have a better understanding of populations and samples that involve real people, we’ll discuss sampling in other types of qualitative research, such as archival research, content analysis, and case studies. We’ll then move to a larger discussion about the difference between sampling in qualitative research generally versus quantitative research, then we’ll move on to the idea of “theoretical” generalizability, and finally, we’ll conclude with some practical tips on the correct “number” to include in one’s sample.

Sampling People

To help think through samples, let’s imagine we want to know more about “vaccine hesitancy.” We’ve all lived through 2020 and 2021, and we know that a sizable number of people in the United States (and elsewhere) were slow to accept vaccines, even when these were freely available. By some accounts, about one-third of Americans initially refused vaccination. Why is this so? Well, as I write this in the summer of 2021, we know that some people actively refused the vaccination, thinking it was harmful or part of a government plot. Others were simply lazy or dismissed the necessity. And still others were worried about harmful side effects. The general population of interest here (all adult Americans who were not vaccinated by August 2021) may be as many as eighty million people. We clearly cannot talk to all of them. So we will have to narrow the number to something manageable. How can we do this?

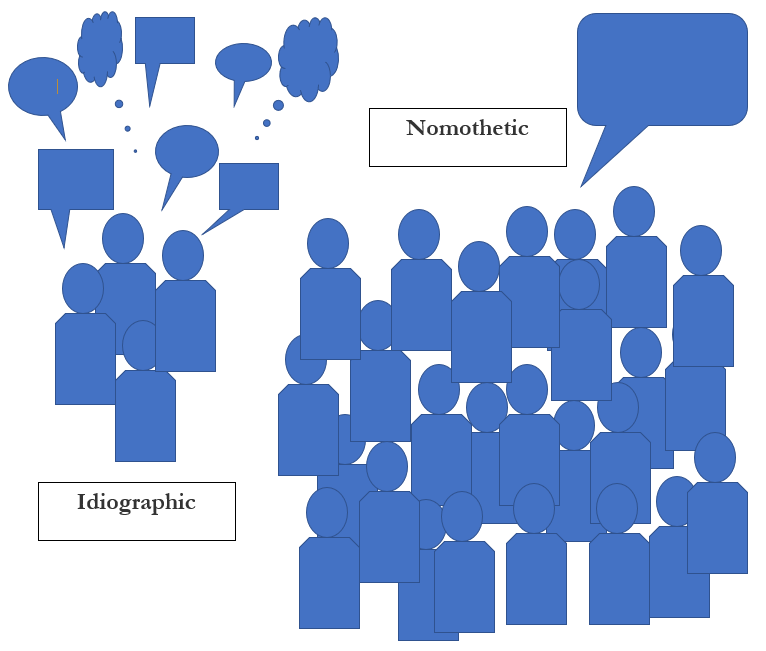

First, we have to think about our actual research question and the form of research we are conducting. I am going to begin with a quantitative research question. Quantitative research questions tend to be simpler to visualize, at least when we are first starting out doing social science research. So let us say we want to know what percentage of each kind of resistance is out there and how race or class or gender affects vaccine hesitancy. Again, we don’t have the ability to talk to everyone. But harnessing what we know about normal probability distributions (see quantitative methods for more on this), we can find this out through a sample that represents the general population. We can’t really address these particular questions if we only talk to White women who go to college with us. And if you are really trying to generalize the specific findings of your sample to the larger population, you will have to employ probability sampling , a sampling technique where a researcher sets a selection of a few criteria and chooses members of a population randomly. Why randomly? If truly random, all the members have an equal opportunity to be a part of the sample, and thus we avoid the problem of having only our friends and neighbors (who may be very different from other people in the population) in the study. Mathematically, there is going to be a certain number that will be large enough to allow us to generalize our particular findings from our sample population to the population at large. It might surprise you how small that number can be. Election polls of no more than one thousand people are routinely used to predict actual election outcomes of millions of people. Below that number, however, you will not be able to make generalizations. Talking to five people at random is simply not enough people to predict a presidential election.

In order to answer quantitative research questions of causality, one must employ probability sampling. Quantitative researchers try to generalize their findings to a larger population. Samples are designed with that in mind. Qualitative researchers ask very different questions, though. Qualitative research questions are not about “how many” of a certain group do X (in this case, what percentage of the unvaccinated hesitate for concern about safety rather than reject vaccination on political grounds). Qualitative research employs nonprobability sampling . By definition, not everyone has an equal opportunity to be included in the sample. The researcher might select White women they go to college with to provide insight into racial and gender dynamics at play. Whatever is found by doing so will not be generalizable to everyone who has not been vaccinated, or even all White women who have not been vaccinated, or even all White women who have not been vaccinated who are in this particular college. That is not the point of qualitative research at all. This is a really important distinction, so I will repeat in bold: Qualitative researchers are not trying to statistically generalize specific findings to a larger population . They have not failed when their sample cannot be generalized, as that is not the point at all.

In the previous paragraph, I said it would be perfectly acceptable for a qualitative researcher to interview five White women with whom she goes to college about their vaccine hesitancy “to provide insight into racial and gender dynamics at play.” The key word here is “insight.” Rather than use a sample as a stand-in for the general population, as quantitative researchers do, the qualitative researcher uses the sample to gain insight into a process or phenomenon. The qualitative researcher is not going to be content with simply asking each of the women to state her reason for not being vaccinated and then draw conclusions that, because one in five of these women were concerned about their health, one in five of all people were also concerned about their health. That would be, frankly, a very poor study indeed. Rather, the qualitative researcher might sit down with each of the women and conduct a lengthy interview about what the vaccine means to her, why she is hesitant, how she manages her hesitancy (how she explains it to her friends), what she thinks about others who are unvaccinated, what she thinks of those who have been vaccinated, and what she knows or thinks she knows about COVID-19. The researcher might include specific interview questions about the college context, about their status as White women, about the political beliefs they hold about racism in the US, and about how their own political affiliations may or may not provide narrative scripts about “protective whiteness.” There are many interesting things to ask and learn about and many things to discover. Where a quantitative researcher begins with clear parameters to set their population and guide their sample selection process, the qualitative researcher is discovering new parameters, making it impossible to engage in probability sampling.

Looking at it this way, sampling for qualitative researchers needs to be more strategic. More theoretically informed. What persons can be interviewed or observed that would provide maximum insight into what is still unknown? In other words, qualitative researchers think through what cases they could learn the most from, and those are the cases selected to study: “What would be ‘bias’ in statistical sampling, and therefore a weakness, becomes intended focus in qualitative sampling, and therefore a strength. The logic and power of purposeful sampling like in selecting information-rich cases for study in depth. Information-rich cases are those from which one can learn a great deal about issues of central importance to the purpose of the inquiry, thus the term purposeful sampling” ( Patton 2002:230 ; emphases in the original).

Before selecting your sample, though, it is important to clearly identify the general population of interest. You need to know this before you can determine the sample. In our example case, it is “adult Americans who have not yet been vaccinated.” Depending on the specific qualitative research question, however, it might be “adult Americans who have been vaccinated for political reasons” or even “college students who have not been vaccinated.” What insights are you seeking? Do you want to know how politics is affecting vaccination? Or do you want to understand how people manage being an outlier in a particular setting (unvaccinated where vaccinations are heavily encouraged if not required)? More clearly stated, your population should align with your research question . Think back to the opening story about Damaske’s work studying the unemployed. She drew her sample narrowly to address the particular questions she was interested in pursuing. Knowing your questions or, at a minimum, why you are interested in the topic will allow you to draw the best sample possible to achieve insight.

Once you have your population in mind, how do you go about getting people to agree to be in your sample? In qualitative research, it is permissible to find people by convenience. Just ask for people who fit your sample criteria and see who shows up. Or reach out to friends and colleagues and see if they know anyone that fits. Don’t let the name convenience sampling mislead you; this is not exactly “easy,” and it is certainly a valid form of sampling in qualitative research. The more unknowns you have about what you will find, the more convenience sampling makes sense. If you don’t know how race or class or political affiliation might matter, and your population is unvaccinated college students, you can construct a sample of college students by placing an advertisement in the student paper or posting a flyer on a notice board. Whoever answers is your sample. That is what is meant by a convenience sample. A common variation of convenience sampling is snowball sampling . This is particularly useful if your target population is hard to find. Let’s say you posted a flyer about your study and only two college students responded. You could then ask those two students for referrals. They tell their friends, and those friends tell other friends, and, like a snowball, your sample gets bigger and bigger.

Researcher Note

Gaining Access: When Your Friend Is Your Research Subject

My early experience with qualitative research was rather unique. At that time, I needed to do a project that required me to interview first-generation college students, and my friends, with whom I had been sharing a dorm for two years, just perfectly fell into the sample category. Thus, I just asked them and easily “gained my access” to the research subject; I know them, we are friends, and I am part of them. I am an insider. I also thought, “Well, since I am part of the group, I can easily understand their language and norms, I can capture their honesty, read their nonverbal cues well, will get more information, as they will be more opened to me because they trust me.” All in all, easy access with rich information. But, gosh, I did not realize that my status as an insider came with a price! When structuring the interview questions, I began to realize that rather than focusing on the unique experiences of my friends, I mostly based the questions on my own experiences, assuming we have similar if not the same experiences. I began to struggle with my objectivity and even questioned my role; am I doing this as part of the group or as a researcher? I came to know later that my status as an insider or my “positionality” may impact my research. It not only shapes the process of data collection but might heavily influence my interpretation of the data. I came to realize that although my inside status came with a lot of benefits (especially for access), it could also bring some drawbacks.

—Dede Setiono, PhD student focusing on international development and environmental policy, Oregon State University

The more you know about what you might find, the more strategic you can be. If you wanted to compare how politically conservative and politically liberal college students explained their vaccine hesitancy, for example, you might construct a sample purposively, finding an equal number of both types of students so that you can make those comparisons in your analysis. This is what Damaske ( 2021 ) did. You could still use convenience or snowball sampling as a way of recruitment. Post a flyer at the conservative student club and then ask for referrals from the one student that agrees to be interviewed. As with convenience sampling, there are variations of purposive sampling as well as other names used (e.g., judgment, quota, stratified, criterion, theoretical). Try not to get bogged down in the nomenclature; instead, focus on identifying the general population that matches your research question and then using a sampling method that is most likely to provide insight, given the types of questions you have.

There are all kinds of ways of being strategic with sampling in qualitative research. Here are a few of my favorite techniques for maximizing insight:

- Consider using “extreme” or “deviant” cases. Maybe your college houses a prominent anti-vaxxer who has written about and demonstrated against the college’s policy on vaccines. You could learn a lot from that single case (depending on your research question, of course).

- Consider “intensity”: people and cases and circumstances where your questions are more likely to feature prominently (but not extremely or deviantly). For example, you could compare those who volunteer at local Republican and Democratic election headquarters during an election season in a study on why party matters. Those who volunteer are more likely to have something to say than those who are more apathetic.

- Maximize variation, as with the case of “politically liberal” versus “politically conservative,” or include an array of social locations (young vs. old; Northwest vs. Southeast region). This kind of heterogeneity sampling can capture and describe the central themes that cut across the variations: any common patterns that emerge, even in this wildly mismatched sample, are probably important to note!

- Rather than maximize the variation, you could select a small homogenous sample to describe some particular subgroup in depth. Focus groups are often the best form of data collection for homogeneity sampling.

- Think about which cases are “critical” or politically important—ones that “if it happens here, it would happen anywhere” or a case that is politically sensitive, as with the single “blue” (Democratic) county in a “red” (Republican) state. In both, you are choosing a site that would yield the most information and have the greatest impact on the development of knowledge.

- On the other hand, sometimes you want to select the “typical”—the typical college student, for example. You are trying to not generalize from the typical but illustrate aspects that may be typical of this case or group. When selecting for typicality, be clear with yourself about why the typical matches your research questions (and who might be excluded or marginalized in doing so).

- Finally, it is often a good idea to look for disconfirming cases : if you are at the stage where you have a hypothesis (of sorts), you might select those who do not fit your hypothesis—you will surely learn something important there. They may be “exceptions that prove the rule” or exceptions that force you to alter your findings in order to make sense of these additional cases.

In addition to all these sampling variations, there is the theoretical approach taken by grounded theorists in which the researcher samples comparative people (or events) on the basis of their potential to represent important theoretical constructs. The sample, one can say, is by definition representative of the phenomenon of interest. It accompanies the constant comparative method of analysis. In the words of the funders of Grounded Theory , “Theoretical sampling is sampling on the basis of the emerging concepts, with the aim being to explore the dimensional range or varied conditions along which the properties of the concepts vary” ( Strauss and Corbin 1998:73 ).

When Your Population is Not Composed of People

I think it is easiest for most people to think of populations and samples in terms of people, but sometimes our units of analysis are not actually people. They could be places or institutions. Even so, you might still want to talk to people or observe the actions of people to understand those places or institutions. Or not! In the case of content analyses (see chapter 17), you won’t even have people involved at all but rather documents or films or photographs or news clippings. Everything we have covered about sampling applies to other units of analysis too. Let’s work through some examples.

Case Studies

When constructing a case study, it is helpful to think of your cases as sample populations in the same way that we considered people above. If, for example, you are comparing campus climates for diversity, your overall population may be “four-year college campuses in the US,” and from there you might decide to study three college campuses as your sample. Which three? Will you use purposeful sampling (perhaps [1] selecting three colleges in Oregon that are different sizes or [2] selecting three colleges across the US located in different political cultures or [3] varying the three colleges by racial makeup of the student body)? Or will you select three colleges at random, out of convenience? There are justifiable reasons for all approaches.

As with people, there are different ways of maximizing insight in your sample selection. Think about the following rationales: typical, diverse, extreme, deviant, influential, crucial, or even embodying a particular “pathway” ( Gerring 2008 ). When choosing a case or particular research site, Rubin ( 2021 ) suggests you bear in mind, first, what you are leaving out by selecting this particular case/site; second, what you might be overemphasizing by studying this case/site and not another; and, finally, whether you truly need to worry about either of those things—“that is, what are the sources of bias and how bad are they for what you are trying to do?” ( 89 ).

Once you have selected your cases, you may still want to include interviews with specific people or observations at particular sites within those cases. Then you go through possible sampling approaches all over again to determine which people will be contacted.

Content: Documents, Narrative Accounts, And So On

Although not often discussed as sampling, your selection of documents and other units to use in various content/historical analyses is subject to similar considerations. When you are asking quantitative-type questions (percentages and proportionalities of a general population), you will want to follow probabilistic sampling. For example, I created a random sample of accounts posted on the website studentloanjustice.org to delineate the types of problems people were having with student debt ( Hurst 2007 ). Even though my data was qualitative (narratives of student debt), I was actually asking a quantitative-type research question, so it was important that my sample was representative of the larger population (debtors who posted on the website). On the other hand, when you are asking qualitative-type questions, the selection process should be very different. In that case, use nonprobabilistic techniques, either convenience (where you are really new to this data and do not have the ability to set comparative criteria or even know what a deviant case would be) or some variant of purposive sampling. Let’s say you were interested in the visual representation of women in media published in the 1950s. You could select a national magazine like Time for a “typical” representation (and for its convenience, as all issues are freely available on the web and easy to search). Or you could compare one magazine known for its feminist content versus one antifeminist. The point is, sample selection is important even when you are not interviewing or observing people.

Goals of Qualitative Sampling versus Goals of Quantitative Sampling

We have already discussed some of the differences in the goals of quantitative and qualitative sampling above, but it is worth further discussion. The quantitative researcher seeks a sample that is representative of the population of interest so that they may properly generalize the results (e.g., if 80 percent of first-gen students in the sample were concerned with costs of college, then we can say there is a strong likelihood that 80 percent of first-gen students nationally are concerned with costs of college). The qualitative researcher does not seek to generalize in this way . They may want a representative sample because they are interested in typical responses or behaviors of the population of interest, but they may very well not want a representative sample at all. They might want an “extreme” or deviant case to highlight what could go wrong with a particular situation, or maybe they want to examine just one case as a way of understanding what elements might be of interest in further research. When thinking of your sample, you will have to know why you are selecting the units, and this relates back to your research question or sets of questions. It has nothing to do with having a representative sample to generalize results. You may be tempted—or it may be suggested to you by a quantitatively minded member of your committee—to create as large and representative a sample as you possibly can to earn credibility from quantitative researchers. Ignore this temptation or suggestion. The only thing you should be considering is what sample will best bring insight into the questions guiding your research. This has implications for the number of people (or units) in your study as well, which is the topic of the next section.

What is the Correct “Number” to Sample?

Because we are not trying to create a generalizable representative sample, the guidelines for the “number” of people to interview or news stories to code are also a bit more nebulous. There are some brilliant insightful studies out there with an n of 1 (meaning one person or one account used as the entire set of data). This is particularly so in the case of autoethnography, a variation of ethnographic research that uses the researcher’s own subject position and experiences as the basis of data collection and analysis. But it is true for all forms of qualitative research. There are no hard-and-fast rules here. The number to include is what is relevant and insightful to your particular study.

That said, humans do not thrive well under such ambiguity, and there are a few helpful suggestions that can be made. First, many qualitative researchers talk about “saturation” as the end point for data collection. You stop adding participants when you are no longer getting any new information (or so very little that the cost of adding another interview subject or spending another day in the field exceeds any likely benefits to the research). The term saturation was first used here by Glaser and Strauss ( 1967 ), the founders of Grounded Theory. Here is their explanation: “The criterion for judging when to stop sampling the different groups pertinent to a category is the category’s theoretical saturation . Saturation means that no additional data are being found whereby the sociologist can develop properties of the category. As he [or she] sees similar instances over and over again, the researcher becomes empirically confident that a category is saturated. [They go] out of [their] way to look for groups that stretch diversity of data as far as possible, just to make certain that saturation is based on the widest possible range of data on the category” ( 61 ).

It makes sense that the term was developed by grounded theorists, since this approach is rather more open-ended than other approaches used by qualitative researchers. With so much left open, having a guideline of “stop collecting data when you don’t find anything new” is reasonable. However, saturation can’t help much when first setting out your sample. How do you know how many people to contact to interview? What number will you put down in your institutional review board (IRB) protocol (see chapter 8)? You may guess how many people or units it will take to reach saturation, but there really is no way to know in advance. The best you can do is think about your population and your questions and look at what others have done with similar populations and questions.

Here are some suggestions to use as a starting point: For phenomenological studies, try to interview at least ten people for each major category or group of people . If you are comparing male-identified, female-identified, and gender-neutral college students in a study on gender regimes in social clubs, that means you might want to design a sample of thirty students, ten from each group. This is the minimum suggested number. Damaske’s ( 2021 ) sample of one hundred allows room for up to twenty-five participants in each of four “buckets” (e.g., working-class*female, working-class*male, middle-class*female, middle-class*male). If there is more than one comparative group (e.g., you are comparing students attending three different colleges, and you are comparing White and Black students in each), you can sometimes reduce the number for each group in your sample to five for, in this case, thirty total students. But that is really a bare minimum you will want to go. A lot of people will not trust you with only “five” cases in a bucket. Lareau ( 2021:24 ) advises a minimum of seven or nine for each bucket (or “cell,” in her words). The point is to think about what your analyses might look like and how comfortable you will be with a certain number of persons fitting each category.

Because qualitative research takes so much time and effort, it is rare for a beginning researcher to include more than thirty to fifty people or units in the study. You may not be able to conduct all the comparisons you might want simply because you cannot manage a larger sample. In that case, the limits of who you can reach or what you can include may influence you to rethink an original overcomplicated research design. Rather than include students from every racial group on a campus, for example, you might want to sample strategically, thinking about the most contrast (insightful), possibly excluding majority-race (White) students entirely, and simply using previous literature to fill in gaps in our understanding. For example, one of my former students was interested in discovering how race and class worked at a predominantly White institution (PWI). Due to time constraints, she simplified her study from an original sample frame of middle-class and working-class domestic Black and international African students (four buckets) to a sample frame of domestic Black and international African students (two buckets), allowing the complexities of class to come through individual accounts rather than from part of the sample frame. She wisely decided not to include White students in the sample, as her focus was on how minoritized students navigated the PWI. She was able to successfully complete her project and develop insights from the data with fewer than twenty interviewees. [1]

But what if you had unlimited time and resources? Would it always be better to interview more people or include more accounts, documents, and units of analysis? No! Your sample size should reflect your research question and the goals you have set yourself. Larger numbers can sometimes work against your goals. If, for example, you want to help bring out individual stories of success against the odds, adding more people to the analysis can end up drowning out those individual stories. Sometimes, the perfect size really is one (or three, or five). It really depends on what you are trying to discover and achieve in your study. Furthermore, studies of one hundred or more (people, documents, accounts, etc.) can sometimes be mistaken for quantitative research. Inevitably, the large sample size will push the researcher into simplifying the data numerically. And readers will begin to expect generalizability from such a large sample.

To summarize, “There are no rules for sample size in qualitative inquiry. Sample size depends on what you want to know, the purpose of the inquiry, what’s at stake, what will be useful, what will have credibility, and what can be done with available time and resources” ( Patton 2002:244 ).

How did you find/construct a sample?

Since qualitative researchers work with comparatively small sample sizes, getting your sample right is rather important. Yet it is also difficult to accomplish. For instance, a key question you need to ask yourself is whether you want a homogeneous or heterogeneous sample. In other words, do you want to include people in your study who are by and large the same, or do you want to have diversity in your sample?

For many years, I have studied the experiences of students who were the first in their families to attend university. There is a rather large number of sampling decisions I need to consider before starting the study. (1) Should I only talk to first-in-family students, or should I have a comparison group of students who are not first-in-family? (2) Do I need to strive for a gender distribution that matches undergraduate enrollment patterns? (3) Should I include participants that reflect diversity in gender identity and sexuality? (4) How about racial diversity? First-in-family status is strongly related to some ethnic or racial identity. (5) And how about areas of study?

As you can see, if I wanted to accommodate all these differences and get enough study participants in each category, I would quickly end up with a sample size of hundreds, which is not feasible in most qualitative research. In the end, for me, the most important decision was to maximize the voices of first-in-family students, which meant that I only included them in my sample. As for the other categories, I figured it was going to be hard enough to find first-in-family students, so I started recruiting with an open mind and an understanding that I may have to accept a lack of gender, sexuality, or racial diversity and then not be able to say anything about these issues. But I would definitely be able to speak about the experiences of being first-in-family.

—Wolfgang Lehmann, author of “Habitus Transformation and Hidden Injuries”

Examples of “Sample” Sections in Journal Articles

Think about some of the studies you have read in college, especially those with rich stories and accounts about people’s lives. Do you know how the people were selected to be the focus of those stories? If the account was published by an academic press (e.g., University of California Press or Princeton University Press) or in an academic journal, chances are that the author included a description of their sample selection. You can usually find these in a methodological appendix (book) or a section on “research methods” (article).

Here are two examples from recent books and one example from a recent article:

Example 1 . In It’s Not like I’m Poor: How Working Families Make Ends Meet in a Post-welfare World , the research team employed a mixed methods approach to understand how parents use the earned income tax credit, a refundable tax credit designed to provide relief for low- to moderate-income working people ( Halpern-Meekin et al. 2015 ). At the end of their book, their first appendix is “Introduction to Boston and the Research Project.” After describing the context of the study, they include the following description of their sample selection:

In June 2007, we drew 120 names at random from the roughly 332 surveys we gathered between February and April. Within each racial and ethnic group, we aimed for one-third married couples with children and two-thirds unmarried parents. We sent each of these families a letter informing them of the opportunity to participate in the in-depth portion of our study and then began calling the home and cell phone numbers they provided us on the surveys and knocking on the doors of the addresses they provided.…In the end, we interviewed 115 of the 120 families originally selected for the in-depth interview sample (the remaining five families declined to participate). ( 22 )

Was their sample selection based on convenience or purpose? Why do you think it was important for them to tell you that five families declined to be interviewed? There is actually a trick here, as the names were pulled randomly from a survey whose sample design was probabilistic. Why is this important to know? What can we say about the representativeness or the uniqueness of whatever findings are reported here?

Example 2 . In When Diversity Drops , Park ( 2013 ) examines the impact of decreasing campus diversity on the lives of college students. She does this through a case study of one student club, the InterVarsity Christian Fellowship (IVCF), at one university (“California University,” a pseudonym). Here is her description:

I supplemented participant observation with individual in-depth interviews with sixty IVCF associates, including thirty-four current students, eight former and current staff members, eleven alumni, and seven regional or national staff members. The racial/ethnic breakdown was twenty-five Asian Americans (41.6 percent), one Armenian (1.6 percent), twelve people who were black (20.0 percent), eight Latino/as (13.3 percent), three South Asian Americans (5.0 percent), and eleven people who were white (18.3 percent). Twenty-nine were men, and thirty-one were women. Looking back, I note that the higher number of Asian Americans reflected both the group’s racial/ethnic composition and my relative ease about approaching them for interviews. ( 156 )

How can you tell this is a convenience sample? What else do you note about the sample selection from this description?

Example 3. The last example is taken from an article published in the journal Research in Higher Education . Published articles tend to be more formal than books, at least when it comes to the presentation of qualitative research. In this article, Lawson ( 2021 ) is seeking to understand why female-identified college students drop out of majors that are dominated by male-identified students (e.g., engineering, computer science, music theory). Here is the entire relevant section of the article:

Method Participants Data were collected as part of a larger study designed to better understand the daily experiences of women in MDMs [male-dominated majors].…Participants included 120 students from a midsize, Midwestern University. This sample included 40 women and 40 men from MDMs—defined as any major where at least 2/3 of students are men at both the university and nationally—and 40 women from GNMs—defined as any may where 40–60% of students are women at both the university and nationally.… Procedure A multi-faceted approach was used to recruit participants; participants were sent targeted emails (obtained based on participants’ reported gender and major listings), campus-wide emails sent through the University’s Communication Center, flyers, and in-class presentations. Recruitment materials stated that the research focused on the daily experiences of college students, including classroom experiences, stressors, positive experiences, departmental contexts, and career aspirations. Interested participants were directed to email the study coordinator to verify eligibility (at least 18 years old, man/woman in MDM or woman in GNM, access to a smartphone). Sixteen interested individuals were not eligible for the study due to the gender/major combination. ( 482ff .)

What method of sample selection was used by Lawson? Why is it important to define “MDM” at the outset? How does this definition relate to sampling? Why were interested participants directed to the study coordinator to verify eligibility?

Final Words

I have found that students often find it difficult to be specific enough when defining and choosing their sample. It might help to think about your sample design and sample recruitment like a cookbook. You want all the details there so that someone else can pick up your study and conduct it as you intended. That person could be yourself, but this analogy might work better if you have someone else in mind. When I am writing down recipes, I often think of my sister and try to convey the details she would need to duplicate the dish. We share a grandmother whose recipes are full of handwritten notes in the margins, in spidery ink, that tell us what bowl to use when or where things could go wrong. Describe your sample clearly, convey the steps required accurately, and then add any other details that will help keep you on track and remind you why you have chosen to limit possible interviewees to those of a certain age or class or location. Imagine actually going out and getting your sample (making your dish). Do you have all the necessary details to get started?

Table 5.1. Sampling Type and Strategies

Further Readings

Fusch, Patricia I., and Lawrence R. Ness. 2015. “Are We There Yet? Data Saturation in Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Report 20(9):1408–1416.

Saunders, Benjamin, Julius Sim, Tom Kinstone, Shula Baker, Jackie Waterfield, Bernadette Bartlam, Heather Burroughs, and Clare Jinks. 2018. “Saturation in Qualitative Research: Exploring Its Conceptualization and Operationalization.” Quality & Quantity 52(4):1893–1907.

- Rubin ( 2021 ) suggests a minimum of twenty interviews (but safer with thirty) for an interview-based study and a minimum of three to six months in the field for ethnographic studies. For a content-based study, she suggests between five hundred and one thousand documents, although some will be “very small” ( 243–244 ). ↵

The process of selecting people or other units of analysis to represent a larger population. In quantitative research, this representation is taken quite literally, as statistically representative. In qualitative research, in contrast, sample selection is often made based on potential to generate insight about a particular topic or phenomenon.

The actual list of individuals that the sample will be drawn from. Ideally, it should include the entire target population (and nobody who is not part of that population). Sampling frames can differ from the larger population when specific exclusions are inherent, as in the case of pulling names randomly from voter registration rolls where not everyone is a registered voter. This difference in frame and population can undercut the generalizability of quantitative results.

The specific group of individuals that you will collect data from. Contrast population.

The large group of interest to the researcher. Although it will likely be impossible to design a study that incorporates or reaches all members of the population of interest, this should be clearly defined at the outset of a study so that a reasonable sample of the population can be taken. For example, if one is studying working-class college students, the sample may include twenty such students attending a particular college, while the population is “working-class college students.” In quantitative research, clearly defining the general population of interest is a necessary step in generalizing results from a sample. In qualitative research, defining the population is conceptually important for clarity.

A sampling strategy in which the sample is chosen to represent (numerically) the larger population from which it is drawn by random selection. Each person in the population has an equal chance of making it into the sample. This is often done through a lottery or other chance mechanisms (e.g., a random selection of every twelfth name on an alphabetical list of voters). Also known as random sampling .

The selection of research participants or other data sources based on availability or accessibility, in contrast to purposive sampling .

A sample generated non-randomly by asking participants to help recruit more participants the idea being that a person who fits your sampling criteria probably knows other people with similar criteria.

Broad codes that are assigned to the main issues emerging in the data; identifying themes is often part of initial coding .

A form of case selection focusing on examples that do not fit the emerging patterns. This allows the researcher to evaluate rival explanations or to define the limitations of their research findings. While disconfirming cases are found (not sought out), researchers should expand their analysis or rethink their theories to include/explain them.

A methodological tradition of inquiry and approach to analyzing qualitative data in which theories emerge from a rigorous and systematic process of induction. This approach was pioneered by the sociologists Glaser and Strauss (1967). The elements of theory generated from comparative analysis of data are, first, conceptual categories and their properties and, second, hypotheses or generalized relations among the categories and their properties – “The constant comparing of many groups draws the [researcher’s] attention to their many similarities and differences. Considering these leads [the researcher] to generate abstract categories and their properties, which, since they emerge from the data, will clearly be important to a theory explaining the kind of behavior under observation.” (36).

The result of probability sampling, in which a sample is chosen to represent (numerically) the larger population from which it is drawn by random selection. Each person in the population has an equal chance of making it into the random sample. This is often done through a lottery or other chance mechanisms (e.g., the random selection of every twelfth name on an alphabetical list of voters). This is typically not required in qualitative research but rather essential for the generalizability of quantitative research.

A form of case selection or purposeful sampling in which cases that are unusual or special in some way are chosen to highlight processes or to illuminate gaps in our knowledge of a phenomenon. See also extreme case .

The point at which you can conclude data collection because every person you are interviewing, the interaction you are observing, or content you are analyzing merely confirms what you have already noted. Achieving saturation is often used as the justification for the final sample size.

The accuracy with which results or findings can be transferred to situations or people other than those originally studied. Qualitative studies generally are unable to use (and are uninterested in) statistical generalizability where the sample population is said to be able to predict or stand in for a larger population of interest. Instead, qualitative researchers often discuss “theoretical generalizability,” in which the findings of a particular study can shed light on processes and mechanisms that may be at play in other settings. See also statistical generalization and theoretical generalization .

A term used by IRBs to denote all materials aimed at recruiting participants into a research study (including printed advertisements, scripts, audio or video tapes, or websites). Copies of this material are required in research protocols submitted to IRB.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research Sampling Strategies

Introduction.

- Sampling Strategies

- Sample Size

- Qualitative Design Considerations

- Discipline Specific and Special Considerations

- Sampling Strategies Unique to Mixed Methods Designs

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Mixed Methods Research

- Qualitative Research Design

- Quantitative Research Designs in Educational Research

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Gender, Power, and Politics in the Academy

- Girls' Education in the Developing World

- Non-Formal & Informal Environmental Education

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research Sampling Strategies by Timothy C. Guetterman LAST MODIFIED: 26 February 2020 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0241

Sampling is a critical, often overlooked aspect of the research process. The importance of sampling extends to the ability to draw accurate inferences, and it is an integral part of qualitative guidelines across research methods. Sampling considerations are important in quantitative and qualitative research when considering a target population and when drawing a sample that will either allow us to generalize (i.e., quantitatively) or go into sufficient depth (i.e., qualitatively). While quantitative research is generally concerned with probability-based approaches, qualitative research typically uses nonprobability purposeful sampling approaches. Scholars generally focus on two major sampling topics: sampling strategies and sample sizes. Or simply, researchers should think about who to include and how many; both of these concerns are key. Mixed methods studies have both qualitative and quantitative sampling considerations. However, mixed methods studies also have unique considerations based on the relationship of quantitative and qualitative research within the study.

Sampling in Qualitative Research

Sampling in qualitative research may be divided into two major areas: overall sampling strategies and issues around sample size. Sampling strategies refers to the process of sampling and how to design a sampling. Qualitative sampling typically follows a nonprobability-based approach, such as purposive or purposeful sampling where participants or other units of analysis are selected intentionally for their ability to provide information to address research questions. Sample size refers to how many participants or other units are needed to address research questions. The methodological literature about sampling tends to fall into these two broad categories, though some articles, chapters, and books cover both concepts. Others have connected sampling to the type of qualitative design that is employed. Additionally, researchers might consider discipline specific sampling issues as much research does tend to operate within disciplinary views and constraints. Scholars in many disciplines have examined sampling around specific topics, research problems, or disciplines and provide guidance to making sampling decisions, such as appropriate strategies and sample size.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Education »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Academic Achievement

- Academic Audit for Universities

- Academic Freedom and Tenure in the United States

- Action Research in Education

- Adjuncts in Higher Education in the United States

- Administrator Preparation

- Adolescence

- Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate Courses

- Advocacy and Activism in Early Childhood

- African American Racial Identity and Learning

- Alaska Native Education

- Alternative Certification Programs for Educators

- Alternative Schools

- American Indian Education

- Animals in Environmental Education

- Art Education

- Artificial Intelligence and Learning

- Assessing School Leader Effectiveness

- Assessment, Behavioral

- Assessment, Educational

- Assessment in Early Childhood Education

- Assistive Technology

- Augmented Reality in Education

- Beginning-Teacher Induction

- Bilingual Education and Bilingualism

- Black Undergraduate Women: Critical Race and Gender Perspe...

- Blended Learning

- Case Study in Education Research

- Changing Professional and Academic Identities

- Character Education

- Children’s and Young Adult Literature

- Children's Beliefs about Intelligence

- Children's Rights in Early Childhood Education

- Citizenship Education

- Civic and Social Engagement of Higher Education

- Classroom Learning Environments: Assessing and Investigati...

- Classroom Management

- Coherent Instructional Systems at the School and School Sy...

- College Admissions in the United States

- College Athletics in the United States

- Community Relations

- Comparative Education

- Computer-Assisted Language Learning

- Computer-Based Testing

- Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Evaluating Improvement Net...

- Continuous Improvement and "High Leverage" Educational Pro...

- Counseling in Schools

- Critical Approaches to Gender in Higher Education

- Critical Perspectives on Educational Innovation and Improv...

- Critical Race Theory

- Crossborder and Transnational Higher Education

- Cross-National Research on Continuous Improvement

- Cross-Sector Research on Continuous Learning and Improveme...

- Cultural Diversity in Early Childhood Education

- Culturally Responsive Leadership

- Culturally Responsive Pedagogies

- Culturally Responsive Teacher Education in the United Stat...

- Curriculum Design

- Data Collection in Educational Research

- Data-driven Decision Making in the United States

- Deaf Education

- Desegregation and Integration

- Design Thinking and the Learning Sciences: Theoretical, Pr...

- Development, Moral

- Dialogic Pedagogy

- Digital Age Teacher, The

- Digital Citizenship

- Digital Divides

- Disabilities

- Distance Learning

- Distributed Leadership

- Doctoral Education and Training

- Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) in Denmark

- Early Childhood Education and Development in Mexico

- Early Childhood Education in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Childhood Education in Australia

- Early Childhood Education in China

- Early Childhood Education in Europe

- Early Childhood Education in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Early Childhood Education in Sweden

- Early Childhood Education Pedagogy

- Early Childhood Education Policy

- Early Childhood Education, The Arts in

- Early Childhood Mathematics

- Early Childhood Science

- Early Childhood Teacher Education

- Early Childhood Teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Years Professionalism and Professionalization Polici...

- Economics of Education

- Education For Children with Autism

- Education for Sustainable Development

- Education Leadership, Empirical Perspectives in

- Education of Native Hawaiian Students

- Education Reform and School Change

- Educational Statistics for Longitudinal Research

- Educator Partnerships with Parents and Families with a Foc...

- Emotional and Affective Issues in Environmental and Sustai...

- Emotional and Behavioral Disorders

- Environmental and Science Education: Overlaps and Issues

- Environmental Education

- Environmental Education in Brazil

- Epistemic Beliefs

- Equity and Improvement: Engaging Communities in Educationa...

- Equity, Ethnicity, Diversity, and Excellence in Education

- Ethical Research with Young Children

- Ethics and Education

- Ethics of Teaching

- Ethnic Studies

- Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention

- Family and Community Partnerships in Education

- Family Day Care

- Federal Government Programs and Issues

- Feminization of Labor in Academia

- Finance, Education

- Financial Aid

- Formative Assessment

- Future-Focused Education

- Gender and Achievement

- Gender and Alternative Education

- Gender-Based Violence on University Campuses

- Gifted Education

- Global Mindedness and Global Citizenship Education

- Global University Rankings

- Governance, Education

- Grounded Theory

- Growth of Effective Mental Health Services in Schools in t...

- Higher Education and Globalization

- Higher Education and the Developing World

- Higher Education Faculty Characteristics and Trends in the...

- Higher Education Finance

- Higher Education Governance

- Higher Education Graduate Outcomes and Destinations

- Higher Education in Africa

- Higher Education in China

- Higher Education in Latin America

- Higher Education in the United States, Historical Evolutio...

- Higher Education, International Issues in

- Higher Education Management

- Higher Education Policy

- Higher Education Research

- Higher Education Student Assessment

- High-stakes Testing

- History of Early Childhood Education in the United States

- History of Education in the United States

- History of Technology Integration in Education

- Homeschooling

- Inclusion in Early Childhood: Difference, Disability, and ...

- Inclusive Education

- Indigenous Education in a Global Context

- Indigenous Learning Environments

- Indigenous Students in Higher Education in the United Stat...

- Infant and Toddler Pedagogy

- Inservice Teacher Education

- Integrating Art across the Curriculum

- Intelligence

- Intensive Interventions for Children and Adolescents with ...

- International Perspectives on Academic Freedom

- Intersectionality and Education

- Knowledge Development in Early Childhood

- Leadership Development, Coaching and Feedback for

- Leadership in Early Childhood Education

- Leadership Training with an Emphasis on the United States

- Learning Analytics in Higher Education

- Learning Difficulties

- Learning, Lifelong

- Learning, Multimedia