- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Income Inequality in America, Essay Example

Pages: 5

Words: 1442

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

Income Inequality in America. Is it a problem and how can it be fixed?

The fact that income inequality is a problem in the United States is undeniable. Claims of the widened income gap between rich Americans and poor Americans, in addition to the diminishing middle class, is a cause for concern (Yates 1). The income inequality is one of the worse political and economic problems the United States faces (Piketty and Saez 1-3). It causes significant problems to social and political stability. It is also an indicator of national decline. Indeed, it is based on this premise that, this essay examines whether income inequality in America is a problem, as well as how it can be fixed.

Income inequality leads to political change. As Saez and Zucman (1-6) explain, loss of income by the middle class compared to the top-earners leads to political change. During the 2000s, many businesses emerged seeking political offices, as they catered for nearly 30 times more employees than the trade unions. Between the year 2000 and 2010, business interest groups spent $492 million on labor, and nearly $28.6 billion on sponsoring activism. This led to the rise of political setting the business groups dominated (Smith 3-5).

Income inequality has adverse effects on democracy. Some scholars have considered that income inequality is not compatible with real democracy (Milanovic 1). This is since creating a disparity between wealthy and poor is historically the main cause of most revolution. Indeed, it is commented that the political system in the United States faces serious threats of drifting towards a kind of oligarchy by influencing the affluent, corporations, and special interest groups. Even though, income inequality may not have impact on economic growth, the action by the government may reduce the current levels. This raises tax rates on the wealthy. It may also cause political dispute or friction – between the poor and the rich.

Income inequality contributes to national poverty. Greater income inequality is likely to encourage greater rates of poverty, as under such situations, income shifts from those in the lower income bracket to those in the upper-income bracket. Saez and Zucman (1-6) argue that when wealth remains in upper income bracket, it may lead to political revolutions and policy reforms to offset the impacts that induce poverty. This has been the trend over the decade (Economist 1). The gap in earnings has also increased over the past five years. Current statistics from the U.S. Census shows that in 2010, the wealthiest 20 percent of entire households was allocated 50.2 percent of the sum household-income, compared to the poorest 20 percent, which received 3.3 percent. In the 1980s, the income shares of the richest households received 44.1 percent. The poorest got 4.2 percent. This shows rising inequality and poverty. Further statistics indicates that individuals in the least-affluent households lost nearly 21.4 percent of their income share. On the other hand, the most-affluent households witnessed an income rise of nearly 13.8 percent. Conversely, the remaining two poorest quintiles lost income (Economist 1).

Income inequality leads to political polarization. As Political Research Quarterly establishes, income inequality is connected to the current political polarization in the United States. In its 2013 study, Political Research Quarterly established that officials who were elected tended respond to the whims of the officials within the upper-income bracket, as a result ignoring the needs of people within the lower income group. The analysis provided by Martin and Harris (1) show that, income inequality is connected to the extent to which the House of Representatives polarization has always voted.

Income inequality also leads to social stratification. Martin and Harris (1) show that class divisions have mainly resulted due to income inequality. This has led to class warfare where the rich rally around the rich and the poor rally around the poor to gain political emancipation. Hence, the rich tend to create an own virtual country, which in their perception should be a self-contained world that is complete with first-rate social services, separate economy, and infrastructure. Indeed, the gap between poor and the rich is widening more in the United States than most advanced country. A growing consensus, for that reason, is that Americans have placed emphasis on pursuing economic growth instead of income redistribution. This argument is supported by current economists, such as Corak (2013) in his analysis of theorist Alan Krueger’s “Great Gatsby Curve.” In his review, Corak (2013) indicates that nations with greater income inequalities also tend to have a greater proportion of economic advantages and disadvantages. The trend is passed on from parents to their offspring.

On the other hand, some political theorists have argued that income inequality is not a problem, and that the problems have been overstated.

Indeed, Saez and Zucman (1-6) perceive that despite the existence of income inequality, economic growth and equality in terms of getting opportunities should be what matters. Some commentators have also expressed that despite being an American problem, it is also a global problem. As a result, it should not trigger significant policy reforms. Others have also expressed that income inequality has some underlying advantages, leading to a well-functioning and competition-driven economy. Additionally, significant policy reforms to cut out income inequality may lead to policies that lessen the welfare of the more affluent individuals.

A section of researchers also argues that there is no basis in the argument that income inequality slows economic and socio-political growth. Responding to claims that income inequality slows economic and socio-political growth, Petryni (1) argues that inequality is healthy within a free market economy, as it promotes greater competition for economic and political opportunities.

At the same time, wealth inequalities tend to compensate for themselves where an extensive increase in wealth occurs. This also implies that since the income inequalities do not pose significant political or economic problems, forced wealth transfers through taxation may obliterate the income pools needed to create new ventures, leading to further political discord between the poor and the wealthy in the society. Indeed, some recent studies have established a link between high marginal tax rates on high-income earners and greater growth in employment (Petryni 1).

Some political and social theorists also perceived income inequality as valuable and natural characteristic of US economy. The American Enterprise Institute sees the growth of income inequality gap as linked to the growth of opportunities—including the motivation and desire to seek political and social emancipation.

Smith (1) further contends that inequality emanates from the growth of economic prosperity and leads to an improved standard of living of the entire US population. Such incomes, Milanovic (1) argues, are a way of rewarding certain actors in the economy for their maximal investment efforts in the future. Towards this end, therefore, suppressing inequality discourages output and pursuit of political emancipation.

Conclusion and recommendations

Largely, income inequality is a problem in the United States. Income inequality contributes to national poverty. It also has adverse effects on democracy. Further, it leads to political change. Income inequality also leads to political polarization and stratification.

Hence, there is a need for more advanced tax and transfer policies that can align the United States with the other developed nations. This requires tax reforms, such as enacting tax incidence adjustments, subsidizing healthcare and increasing the social security, heavy investment in infrastructure, fortifying labor influence and providing higher education at low costs.

Making education available to more Americans through policies that subsidize cost of education will mean that more Americans have an opportunity for better income. This is since individuals with high education qualification report lower unemployment rate. However, equal job opportunities are also crucial. Public expenditure on welfare should be increased to ensure social and economic security, where the government provides subsidized healthcare. The more affluent members of the society should also be taxed higher than, the poor Americans.

Works Cited

Corak, Miles. “Income Inequality, Equality of Opportunity, and Intergenerational Mobility.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27.3(2013): 79–102

Economist, The. “The rich, the poor and the growing gap between them,” 2006. 11 April 2015, <http://www.economist.com/node/7055911>

Kenworthy, Lane. “Does More Equality Mean Less Economic Growth?” 2007, <http://lanekenworthy.net/2007/12/03/does-more-equality-mean-less-economic-growth/>

Martin, Jonathan and Harris, John. “President Obama, Republicans fight the class war.” Politico, 2012. <http://www.politico.com/story/2013/04/barack-obama-class-warrior-90052.html>

Milanovic, Branko. “More or Less.” International Monetary Fund, 2011.

Petryni, Matt. “Advantages & Disadvantages to Income Inequality.” n.d. 11 April 2015, <http://www.ehow.com/info_11415987_advantages-disadvantages-income-inequality.html>

Piketty, Thomas and Saez, Emmanuel. “Income Inequality In The United States, 1913–1998.” The Quarterly Journal Of Economics 28.1 (2003): 1-39

Saez, Emmanuel and Zucman, Gabriel. “Wealth and Inequality in the United States Since 1913: Evidence from Capitalised Income Tax Data.” National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge: 2013

Smith, Hedrick. “Who Stole the American Dream.” Random House: New York, 2012. < http://newshare.com/ruleschange/book-notes.pdf>

Todd, Michael. “The Benefits of Wealth Inequality (and Why We Should Not Fear It).” Pacific Standard , 2013. <http://www.psmag.com/business-economics/benefits-wealth-inequality-now-fear-67567>

Yates, Michael. “The Great Inequality.” Monthly Review 63.10 (2012)

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

American Airlines Demographic Information, Research Paper Example

Comparing and Contrasting Poems, Poem Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Causes and Consequences of Income Inequality – An Overview

Rising income inequality is one of the greatest challenges facing advanced economies today. Income inequality is multifaceted and is not the inevitable outcome of irresistible structural forces such as globalisation or technological development. Instead, this review shows that inequality has largely been driven by a multitude of political choices. The embrace of neoliberalism since the 1980s has provided the key catalyst for political and policy changes in the realms of union regulation, executive pay, the welfare state and tax progressivity, which have been the key drivers of inequality. These preventable causes have led to demonstrable harmful outcomes that are not explicable solely by material deprivation. This review also shows that inequality has been linked on the economic front with reduced growth, investment and innovation, and on the social front with reduced health and social mobility, and greater violent crime.

1 Introduction

Income inequality has recently come to be viewed as one of the greatest challenges facing the world today. In recent years, the topic has dominated the agenda of the World Economic Forum (WEF), where the world’s top political and business leaders attend. Their global risks report, drawn from over 700 experts in attendance, pronounced inequality to be the greatest threat to the world economy in 2017 ( Elliott 2017 ). Likewise, the past decade has seen leading global figures such as former American President Barack Obama, Pope Francis, Chinese President Xi Jinping, and the former head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Christine Lagarde, all undertake speeches on the gravity of income inequality and the need to address its rise. This is because, as this research note shows, income inequality engenders harmful consequences that are not explicable solely by material deprivation.

The general dynamics of income inequality include a tendency to rise slowly and fluctuate over time. For instance, Japan had one of the highest rates in the world prior to the Second World War and the United States (US) one of the lowest, which has since completely reversed for both. The United Kingdom (UK) was also the second most equitable large European country in the 1970s but is now the most inequitable ( Dorling 2018 : 27–28).

High rates of inequality are rarely sustained for long periods because they tend to lead to or become punctuated by man-made disasters that lead to a levelling out. Scheidel (2017) posits that there in fact exists a violent ‘Four Horseman of Leveling’ (mass mobilisation warfare, transformation revolutions, state collapse, and lethal pandemics) for inequality, which have at times dramatically reduced inequalities because they can lead to the alteration of existing power structures or wipe out the wealth of elites and redistribute their resources. For instance, the pronounced shocks of the two world wars led to the ‘Great Compression’ of income throughout the West in the post-war years. There is already some evidence that the current global pandemic caused by the novel Coronavirus, has led to greater aversion to income inequality ( Asaria, Costa-Font, and Cowell 2021 ; Wiwad et al. 2021 ).

Thus, greater aversion to inequality has been able to reduce inequality in the past, this is because, as this review also shows, income inequality does not result exclusively from efficient market forces but arises out of a set of rules that is shaped by those with political power. Inequality’s rise is not inevitable, nor beyond the control of governments and policymakers, as they can affect distributional outcomes and inequality through public policy.

It is the purpose of this review to outline the causes and consequences of income inequality. The paper begins with an analysis of the key structural and institutional determinants of inequality, followed by an examination into the harmful outcomes of inequality. It then concludes with a discussion of what policymakers can do to arrest the rise of inequality.

2 Causes of Income Inequality

Broadly speaking, explanations for the increase in income inequality have largely been classified as either structural or institutional. Historically, economists emphasised structural causes of increasing income inequality, with globalisation and technological change at the forefront. However, in recent years opinion has shifted to emphasise more institutional political factors to do with the adoption of neoliberal reforms such as privatisation, deregulation and tax and welfare reductions since the early 1980s. They were first embraced and most heavily championed by the UK and US, spreading globally later, and which provide the crucial catalysts of rising income inequality ( Atkinson 2015 ; Brown 2017 ; Piketty 2020 ; Stiglitz 2013 ). I discuss each of these key factors in turn.

2.1 Globalisation

One of the earliest, and most prominent explanations for the rise of income inequality emphasised the role of globalisation ( Borjas, Freeman, and Katz 1992 ; Revenga 1992 ). Globalisation has led to the offshoring of many goods and services that used to be produced or completed domestically in the West, which has created downward pressures on the wages of lower skilled workers. According to the ‘market forces hypothesis,’ increasing inequality is a response to the rising demand for skills at the top, in which the spread of globalisation and technological progress have been facilitated through reduced barriers to trade and movement.

Proponents of globalisation as the leading cause of inequality have argued that globalisation has constrained domestic state choices and left governments collectively powerless to address inequality. Detractors admit that globalisation has indeed had deep structural effects on Western economies but its impact on the degree of agency available to domestic governments has been mediated by individual policy choices ( Thomas 2016 : 346). A key problem with attributing the cause of inequality to globalisation, is that the extent of the inequality increase has varied considerably across countries, even though they have all been exposed to the same effects of globalisation. The US also has the highest inequality amongst rich countries, but it is less reliant on international trade than most other developed countries ( Brown 2017 : 56). Moreover, a recent meta-analysis by Heimberger (2020) found that globalisation has a “small-to-moderate” inequality-increasing effect, with financial globalisation displaying the largest impact.

2.2 Technology

A related explanation for inequality draws attention to the impact of technology specifically. The advent of the digital age has placed a higher premium on the skills needed for non-routine work and reduced the value placed on lower skilled routine work, as it has enabled machines to replace jobs that could be routinised. This skill-biased technological change (SBTC) has led to major changes in the organisation of work, as many full-time permanent jobs with benefits have given way to part-time flexible work without benefits, that are often centred around the completion of short ‘gigs’ such as a car journey or food delivery. For instance, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimated in 2015 that since the 1990s, roughly 60% of all job creation has been in the form of non-standard work due to technological changes and that those employed in such jobs are more likely to be poor ( Brown 2017 : 60).

Relatedly, a prevailing doctrine in economics is ‘marginal productivity theory,’ which holds that people with greater productivity levels will earn higher incomes. This is due to the belief that a person’s productivity is equated to their societal contribution ( Stiglitz 2013 : 37). Since technology is a leading determinant in the productivity of different skills and SBTC has led to increased productivity, it has also become a justification for inequality. However, it is very difficult to separate any one person’s contribution to society from that of others, as even the most successful businessperson owes their success to the rule of law, good infrastructure, and a state educated workforce ( Stiglitz 2013 : 97–98).

Further criticisms of the SBTC explanation, are that there was still substantial SBTC when inequality first fell dramatically and then stabilised in the period from 1930 to 1980, and it has failed to explain the perpetuation of both the gender and racial wage gap, “or the dramatic rise in education-related wage gaps for younger versus older workers” ( Brown 2017 : 67). Although it is difficult to decouple globalisation and technology, as they each have compounding tendencies, it is most likely that globalisation and technology are important explanatory factors for inequality, but predominantly facilitate and underlie the following more determinant institutional factors that happen to be already present, such as reduced tax progressivity, rising executive pay, and union decline. It is to these factors that I now turn.

2.3 Tax Policy

Taxes overwhelmingly comprise the primary source of revenue that governments can use for redistribution, which is fundamental to alleviating income inequality. Redistribution is defended on economic grounds because the marginal utility of money declines as income rises, meaning that the benefit derived from extra income is much higher for the poor than the rich. However, since the late 1970s, a major rethinking surrounding redistributive policy occurred. This precipitated ‘trickle-down economics’ theory achieving prominence amongst American and British policymakers, whereby the benefits from tax cuts on the wealthy would trickle-down to everyone. Subsequently, expert opinion has determined that tax cuts do not actually spur economic growth ( CBPP 2017 ).

Personal income tax progressivity has declined sharply in the West, as the average top income tax rate for OECD members fell from 62% in 1981 to 35% in 2015 ( IMF 2017 : 11). However, the decline has been most pronounced in the UK and the US, which had top rates of around 90% in the 1960s and 1970s. Corporate tax rates have also plummeted by roughly one half across the OECD since 1980 ( Shaxson 2015 : 4). Recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) research found that between 1985 and 1995, redistribution through the tax system had offset 60% of the increase in market inequality but has since failed to respond to the continuing increase in inequality ( IMF 2017 ). Moreover, in a sample of 18 OECD countries encompassing 50 years, Hope and Limberg (2020) found that tax reforms even significantly increased pre-tax income inequality, while having no significant effect on economic growth.

This decline in tax progressivity has been a leading cause of rising income inequality, which has been compounded by the growing problem of tax avoidance. A complex global web of shell corporations has been constructed by international brokers in offshore tax havens that is able to keep wealth hidden from tax collectors. The total hidden amount in tax havens is estimated to be $7.6 trillion US dollars and rising, or roughly 8% of total global household wealth ( Zucman 2015 : 36). Recent research has revealed that tax havens are overwhelmingly used by the immensely rich ( Alstadsæter, Johannesen, and Zucman 2019 ), thus taxing this wealth would substantially reduce income inequality and increase revenue available for redistribution. The massive reduction in income tax progressivity in the Anglo world, after it had been amongst its leaders in the post-war years, also “probably explains much of the increase in the very highest earned incomes” since 1980 ( Piketty 2014 : 495–496).

2.4 Executive Pay

The enormous rising pay of executives since the 1980s, has also fuelled income inequality and more specifically the gap between executives and their employees. For example, the gap between Chief Executive Officers (CEO) and their workers at the 500 leading US companies in 2016, was 335 times, which is nearly 10 times larger than in 1980. It is a similar story in the UK, with a pay ratio of 131 for large British firms, which has also risen markedly since 1980 ( Dorling 2017 ).

Piketty (2014 : 335) posits that the dramatic reduction in top income tax has had an amplifying effect on top executives pay since it provides them with much greater incentive to seek larger remuneration, as far less is then taken in tax. It is difficult to objectively measure an individual’s contribution to a company and with the onset of trickle-down economics and accompanying business-friendly climate since the 1980s, top executives have found it relatively easy to convince boards of their monetary worth ( Gabaix and Landier 2008 ).

The rise in executive pay in both the UK and US, is far larger than the rest of the OECD. This may partially be explained by the English-speaking ‘superstar’ theory, whereby the global market demand for top CEOs is much higher for native English speakers due to English being the prime language of the global economy ( Deaton 2013 : 210). Saez and Veall (2005) provide support for the theory in a study of the top 1% of earners from the Canadian province of Quebec, which showed that English speakers were able to increase their income share over twice as much as their French-speaking counterparts from 1980 to 2000. This upsurge of income at the top of the labour market has been accompanied by stagnation or diminishing returns for the middle and lower parts of the labour market, which has been affected by the dramatic decline of union influence throughout the West.

2.5 Union Decline

Trade unions have typically been viewed as an important force for moderating income inequality. They “contribute to wage compression by restricting wage decline among low-wage earners” and restrain wage surges among high-wage earners ( Checchi and Visser 2009 : 249). The mere presence of unions can also drive up the wages of non-union employees in similar industries, as employers tend to give in to wage demands to keep unions out. Union density has also been proven to be strongly associated with higher redistribution both directly and indirectly, through its influence on left party governments ( Haddow 2013 : 403).

There had broadly existed a ‘social contract’ between labour and business, whereby collective bargaining establishes a wage structure in many industries. However, this contract was abandoned by corporate America in the mid-1970s when large-scale corporate donations influenced policymakers to oppose pro-union reform of labour law, leading to political defeats for unions ( Hacker and Pierson 2010 : 58–59). The crackdown of strikes culminating in the momentous Air Traffic Controllers’ strike (1981) in the US and coal miner’s strike (1984–85) in the UK, caused labour to become de-politicised, which was self-reinforcing, because as their political power dispersed, policymakers had fewer incentives to protect or strengthen union regulations ( Rosenfeld and Western 2011 ). Consequently, US union density has plummeted from around a third of the workforce in 1960, down to 11.9% last decade, with the steepest decline occurring in the 1980s ( Stiglitz 2013 : 81).

Although the decline in union density is not as steep cross-nationally, the pattern is still similar. Baccaro and Howell (2011 : 529) found that on average the unionisation rate decreased by 0.39% a year since 1974 for the 15 OECD members they surveyed. Increasingly, the decline in the fortunes of labour is being linked with the increase in inequality and the sharpest increases in income inequality have occurred in the two countries with the largest falls in union density – the UK and US. Recent studies have found that the weakening of organised unions accounts for between a third and a fifth of the total rise in income inequality in the US ( Rosenfeld and Western 2011 ), and nearly one half of the increase in both the Gini rate and the top 10%’s income share amongst OECD members ( Jaumotte and Buitron 2015 ).

To illustrate the changing relationship between inequality and unionisation, Figure 1 displays a local polynomial smoother scatter plot of union density by income inequality, for 23 OECD countries, 1980–2018. They are negatively correlated, as countries with higher union density have much lower levels of income inequality. Figure 2 further plots the time trends of both. Income inequality (as measured via the Gini coefficient) has climbed over 0.02 percentage points on average in these countries since 1980, which is roughly a one-tenth rise. Whereas union density has fallen on average from 44 to 35 percentage points, which is over one-fifth.

Gini coefficient by union density, OECD 1980–2018. Data on Gini coefficients from SWIID ( Solt 2020 ); data on union density from ICTWSS Database ( Visser 2019 ).

Gini coefficient by union density, 1980–2018. Data on Gini coefficients from SWIID ( Solt 2020 ); data on union density from ICTWSS Database ( Visser 2019 ).

In sum, income inequality is multifaceted and is not the inevitable outcome of irresistible structural forces such as globalisation or technological development. Instead, it has largely been driven by a multitude of political choices. Tridico (2018) finds that the increases in inequality from 1990 to 2013 in 26 OECD countries, was largely owing to increased financialisation, deepening labour flexibility, the weakening of trade unions and welfare state retrenchment. While Huber, Huo, and Stephens (2019) recently reveals that top income shares are unrelated to economic growth and knowledge-intensive production but is closely related to political and policy changes surrounding union density, government partisanship, top income tax rates, and educational investment. Lastly, Hager’s (2020) recent meta-analysis concludes that the “empirical record consistently shows that government policy plays a pivotal role” in shaping income inequality.

These preventable causes that have given rise to inequality have created socio-economic challenges, due to the demonstrably negative outcomes that inequality engenders. What follows is a detailed analysis of the significant mechanisms that income inequality induces, which lead to harmful outcomes.

3 Consequences of Income Inequality

Escalating income inequality has been linked with numerous negative outcomes. On the economic front, negative results transpire beyond the obvious poverty and material deprivation that is often associated with low incomes. Income inequality has also been shown to reduce growth, innovation, and investment. On the social front, Wilkinson and Pickett’s ground-breaking The Spirit Level ( 2009 ), found that societies that are more unequal have worse social outcomes on average than more egalitarian societies. They summarised an extensive body of research from the previous 30 years to create an Index of Health and Social Problems, which revealed a host of different health and social problems (measuring life expectancy, infant mortality, obesity, trust, imprisonment, homicide, drug abuse, mental health, social mobility, childhood education, and teenage pregnancy) as being positively correlated with the level of income inequality across rich nations and across states within the US. Figure 3 displays the cross-national findings via a sample of 21 OECD countries.

Index of health and social problems by Gini coefficient. Data on health and social problems index from The Equality Trust (2018) ; data on Gini coefficients from OECD (2020) .

3.1 Economic

Income inequality is predominantly an economic subject. Therefore, it is understandable that it can engender pervasive economic outcomes. Foremost economically speaking, it has been linked with reduced growth, investment and innovation. Leading international organisations such as the IMF, World Bank and OECD, pushed for neoliberal reforms beginning in the 1980s, although they have recently started to substantially temper their views due to their own research into inequality. A 2016 study by IMF economists, noted that neoliberal policies have delivered benefits through the expansion of global trade and transfers of technology, but the resulting increases in inequality “itself undercut growth, the very thing that the neo-liberal agenda is intent on boosting” ( Ostry, Loungani, and Furceri 2016 : 41). Cingano’s (2014) OECD cross-national study, found that once a country’s income inequality reaches a certain level it reduces growth. The growth rate in these countries would have been one-fifth higher had income inequality not increased, while the greater equality of the other countries included in the study helped to increase their growth rates.

Consumer spending is good for economic growth but rising income inequality shifts more money to the top of the income distribution, where higher income individuals have a much smaller propensity to consume than lower-income individuals. The wealthy save roughly 15–25% of their income, whereas low income individuals spend their entire income on consumer goods and services ( Stiglitz 2013 : 106). Therefore, greater inequality reduces demand in an economy and is a major contributor to the ‘secular stagnation’ (persistent insufficient demand relative to aggregate private savings) that the largest Western economies have been experiencing since the financial crisis. Inequality also increases the level of debt, as lower-income individuals borrow more to maintain their standard of living, especially in a climate of low interest rates. Combined with deregulation, greater debt increases instability and “was a major contributor to, if not the underlying cause of, the 2008 financial crash” ( Brown 2017 : 35–36).

Another key economic effect of income inequality is that it leads to reduced welfare spending and public investment. Since a greater share of the income distribution is earned by the very wealthy, governments have less income available to fund education, public amenities, and other services that the poor rely heavily on. This creates social separation, whereby the wealthy opt out in publicly funding services because their private equivalents are of better quality. This causes a cycle of increasing income inequality that is likely to eventually lead to a situation of “private affluence and public squalor” ( Marmot 2015 : 39).

Lastly, it has been proven that economic instability is a by-product of increasing inequality, which harms innovation. Both countries and American states with the highest inequality have been found to be the least innovative in terms of the amount of Intellectual Property (IP) patents they produce ( Dorling 2018 : 129–130). Although income inequality is predominantly an economic subject, its effects are so pervasive that it has also been linked to a host of negative health and societal outcomes.

Wilkinson and Pickett found key associations between income inequality for both physical and mental health. For example, they discovered that on average the life expectancy gap is more than four years between the least and most equitable richest nations (Japan and the US). Since their revelations, overall life expectancy has been reported to be declining in the US ( Case and Deaton 2020 ). It has held or declined every year since 2014, which has led to a cumulative drop of 1.13 years ( Andrasfay and Goldman 2021 ). Marmot (2015) has provided evidence that there exists a social gradient whereby differences in affluence translate into increasing health inequalities, which can be shown even down to the neighbourhood level, as more affluent areas have higher life expectancy on average than deprived areas, and a clear gradient appears where life expectancy increases in line with affluence.

Moreover, Marmot’s famous Whitehall studies, which are large-scale longitudinal studies of Whitehall employees of UK central government, found an inverse-relationship between salary grade and ill-health, whereby low-grade workers were four times as likely as high-grade workers to suffer from ill-health ( 2015 : 11). Health steadily improves with rank and the correlation is little affected by lifestyle controls such as tobacco and alcohol usage. However, the leading factor that seems to make the most difference in ill-health is job stress and a person’s sense of control over their work, including the variety of work and the use and development of skills ( Schrecker and Bambra 2015 : 54–55).

‘Psychosocial stresses,’ like those appearing in the Whitehall studies, have been found to be more common and frequent amongst low-income individuals, beyond just the workplace ( Jensen and van Kersbergen 2017 : 24). Wilkinson and Pickett (2019) posit that greater income inequality engenders low self-esteem, chronic stress and depression, stemming from status anxiety. This occurs because more importance is placed on where people fit in a hierarchy with greater inequality. For evidence, they outline a clear relationship of a much higher percentage of the population suffering from mental illness in more unequal countries. Meticulous research has shown that huge inequalities in income result in the poor having feelings of shame across a range of environments. Furthermore, Dickerson and Kemeny’s (2004) meta-analysis of 208 studies found that stress-hormone (cortisol) levels were raised particularly “when people felt that others were making negative judgements about them” ( Rowlingson 2011 : 24).

These effects on both mental and physical health can be best illustrated via the ‘absolute income’ and ‘relative income’ hypotheses ( Daly, Boyce, and Wood 2015 ). The relative income hypothesis posits that when an individual’s income is held constant, the relative income of others can affect a person’s health depending on how they view themselves in comparison to those above them ( Wilkinson 1996 ). This pattern also holds when income inequality increases at the societal level, because if such changes lead to increases in chronic stress, it can increase ill-health nationally. Whereas the absolute income hypothesis predicts that health gains from an extra unit of income diminish as an individual’s income rises ( Kawachi, Adler, and Dow 2010 ). A mean preserving transfer from a richer to poorer individual raises the health of the poorer individual more than it lowers the health of the richer person. This occurs because there is an optimum threshold of income required to maintain good health. Thus, when holding total income constant, a more equal distribution of income should improve overall population health. This pattern also applies at the country-wide level, as the “effect of income on health appears substantial as countries move from about $15,000 to 25,000 US dollars per capita,” but appears non-existent beyond that point ( Leigh, Jencks, and Smeeding 2009 : 386–387).

Income inequality also impacts happiness and wellbeing, as the happiest nations are routinely the ones with low inequality, such as Denmark and Norway. Happiness has been proven to be affected by the law of diminishing returns in economics. It states that higher income incrementally improves happiness but only up to a certain point, as any individual income earned beyond roughly $70,000 US dollars, does not bring about greater happiness ( Deaton 2013 : 53). The negative physical and mental health outcomes that income inequality provoke, also impact key societal areas such as crime, social mobility and education.

Rates of violent crime are lower in more equal countries ( Hsieh and Pugh 1993 ; Whitworth 2012 ). This is largely because more equal countries have less poverty, which leads to less people being desperate about their situation, as lower-income individuals have been shown to commit more crime. Relatedly, according to strain theory, more unequal societies place higher social value in achieving economic success, while providing lower means to achieve it ( Merton 1938 ). This generates strain, which may lead more individuals to pursue crime as a means of attaining financial success. At the opposite end of the income spectrum, the wealthy in more equal countries are also less likely to exploit others and commit fraud or exhibit other anti-social behaviour, partly because they feel less of a need to cut corners to get ahead, or to make money ( Dorling 2017 : 152–153). Homicides also tend to rise with inequality. Daly (2016) reveals that inequality predicts homicide rates better than any other variable and accounts for around half of the variance in murder rates between countries and American states. Roughly 90% of American homicides are committed by men, and since the majority of homicides occur over status, inequality raises the stakes of disputes over status amongst men.

Studies have also shown that there is a marked negative relationship between income inequality and social mobility. Utilising Intergenerational Earnings Elasticity data from Blanden, Gregg, and Machin (2005) , Wilkinson and Pickett (2009) first outline this relationship cross-nationally for eight OECD countries. Corak (2013) famously expanded on this with his ‘Great Gatsby Curve’ for 22 countries using the same measure. I update and expand on these studies in Figure 4 to include all 36 OECD members, utilising the WEF’s inaugural 2020 Social Mobility Index. It clearly shows that social mobility is much lower on average in more unequal countries across the entire OECD.

Index of social mobility by Gini coefficient. Data on social mobility index from World Economic Forum (2020) ; data on Gini coefficients from SWIID ( Solt 2020 ).

A primary driver for the negative relationship between inequality and social mobility, derives from the availability of resources during early childhood. Life chances have been shown to be determined in early childhood to a disproportionately large extent ( Jensen and van Kersbergen 2017 : 29). Children in more equitable regions such as Scandinavia, have better access to resources, as they go to similar schools, receive similar educational opportunities, and have access to a wider range of career options. Whereas in the UK and US, a greater number of jobs at the top are closed off to those at the bottom and affluent parents are far more likely to send their children to private schools and fund other ‘child enrichment’ goods and services ( Dorling 2017 : 26). Therefore, as income inequality rises, there is a greater disparity in the resources that rich and poor parents can invest in their children’s education, which has been shown to substantially affect “cognitive development and school achievement” ( Brown 2017 : 33–34).

4 Conclusions

The causes and consequences of income inequality are multifaceted. Income inequality is not the inevitable outcome of irresistible structural forces such as globalisation or technological development. Instead, it has largely been driven by a multitude of institutional political choices. These preventable causes that have given rise to inequality have created socio-economic challenges, due to the demonstrably negative outcomes that inequality engenders.

The neoliberal political consensus poses challenges for policymakers to arrest the rise of income inequality. However, there are many proven solutions that policymakers can enact if the appropriate will can be summoned. Restoring higher levels of labour protections would aid in reversing the declining trend of labour wage share. Similarly, government promotion and support for new corporate governance models that give trade unions and workers a seat at the table in ownership decisions through board memberships, would somewhat redress the increasing power imbalance between capital and labour that is generating more inequality. Greater regulation aimed at limiting the now dominant shareholder principle of maximising value through share buy-backs and instead offering greater incentives to pursue maximisation of stakeholder value, long-term financial stability and investment, can reduce inequality. Most importantly, tax policy can be harnessed to redress income inequality. Such policies include restoring higher marginal income and corporate tax rates, setting higher corporate tax rates for firms with higher ratios of CEO-to-worker pay, and establishing luxury taxes on spiralling compensation packages. Finally, a move away from austerity, which has gripped the West since the financial crisis, and a move towards much greater government investment and welfare state spending, would also lift growth and low-wages.

Alstadsæter, A., N. Johannesen, and G. Zucman. 2019. “Tax Evasion and Inequality.” American Economic Review 109 (6): 2073–103. Search in Google Scholar

Andrasfay, T., and N. Goldman. 2021. “Reductions in 2020 US Life Expectancy Due to COVID-19 and the Disproportionate Impact on the Black and Latino Populations.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118 (5), https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2014746118 . Search in Google Scholar

Asaria, M., J. Costa-Font, and F. A. Cowell. 2021. “How Does Exposure to Covid-19 Influence Health and Income Inequality Aversion.” IZA Discussion Paper. no. 14103. Also available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3785067 . Search in Google Scholar

Atkinson, A. B. 2015. Inequality: What Can Be Done? London: Harvard University Press. Search in Google Scholar

Baccaro, L., and C. Howell. 2011. “A Common Neoliberal Trajectory: The Transformation of Industrial Relations in Advanced Capitalism.” Politics & Society 39 (4): 521–63, https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329211420082 . Search in Google Scholar

Blanden, J., P. Gregg, and S. Machin. 2005. Intergenerational Mobility in Europe and North America . London: Centre for Economic Performance. Search in Google Scholar

Borjas, G. J., R. B. Freeman, and L. F. Katz. 1992. “On the Labor Market Effects of Immigration and Trade.” In Immigration and the Workforce , edited by G. J. Borjas, and R. B. Freeman, 213–44. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Search in Google Scholar

Brown, R. 2017. The Inequality Crisis: The Facts and What We Can Do About It . Bristol: Polity Press. Search in Google Scholar

Case, A., and A. Deaton. 2020. Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism . Princeton: Princeton University Press. Search in Google Scholar

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) . 2017. Tax Cuts for the Rich Aren’t an Economic Panacea – and Could Hurt Growth. Also available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/tax-cuts-for-the-rich-arent-an-economic-panacea-and-could-hurt-growth . Search in Google Scholar

Checchi, D., and J. Visser. 2009. “Inequality and the Labor Market: Unions.” In The Oxford Handbook of Economic Inequality , edited by B. Nolan, W. Salverda, and T. M. Smeeding, 230–56. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Search in Google Scholar

Cingano, F. 2014. Trends in Income Inequality and its Impact on Economic Growth . OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 163. Paris: OECD Publishing. Search in Google Scholar

Corak, M. 2013. “Income Inequality, Equality of Opportunity, and Intergenerational Mobility.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27 (3): 79–102, https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.27.3.79 . Search in Google Scholar

Daly, M. 2016. Killing the Competition: Economic Inequality and Homicide . Oxford: Routledge. Search in Google Scholar

Daly, M., C. Boyce, and A. Wood. 2015. “A Social Rank Explanation of How Money Influences Health.” Health Psychology 34 (3): 222–30, https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000098 . Search in Google Scholar

Deaton, A. 2013. The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality . Princeton: Princeton University Press. Search in Google Scholar

Dickerson, S. S., and M. Kemeny. 2004. “Acute Stressors and Cortisol Responses: A Theoretical Integration and Synthesis of Laboratory Research.” Psychological Bulletin 130 (3): 355–91, https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.355 . Search in Google Scholar

Dorling, D. 2017. The Equality Effect: Improving Life for Everyone . Oxford: New Internationalist Publications Ltd. Search in Google Scholar

Dorling, D. 2018. Do We Need Economic Inequality? Cambridge: Polity Press. Search in Google Scholar

Elliott, L. 2017. “Rising Inequality Threatens World Economy, Says WEF.” The Guardian. Also available at https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/jan/11/inequality-world-economy-wef-brexit-donald-trump-world-economic-forum-risk-report . Search in Google Scholar

Gabaix, X., and A. Landier. 2008. “Why Has CEO Pay Increased So Much?” Quarterly Journal of Economics 123 (1): 49–100, https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2008.123.1.49 . Search in Google Scholar

Hacker, J. S., and P. Pierson. 2010. Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer – And Turned Its Back on the Middle Class . New York: Simon & Schuster. Search in Google Scholar

Haddow, R. 2013. “Labour Market Income Transfers and Redistribution.” In Inequality and the Fading of Redistributive Politics , edited by K. Banting, and J. Myles, 381–412. Vancouver: UBC Press. Search in Google Scholar

Hager, S. 2020. “Varieties of Top Incomes?” Socio-Economic Review 18 (4): 1175–98. Search in Google Scholar

Heimberger, P. 2020. “Does Economic Globalisation Affect Income Inequality? A Meta‐analysis.” The World Economy 43 (11): 2960–82, https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.13007 . Search in Google Scholar

Hope, D., and J. Limberg. 2020. The Economic Consequences of Major Tax Cuts for the Rich . London: London School of Economics and Political Science. Also available at http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/107919/ . Search in Google Scholar

Hsieh, C.-C., and M. D. Pugh. 1993. “Poverty, Inequality and Violent Crime: a Meta-Analysis of Recent Aggregate Data Studies.” Criminal Justice Review 18 (2): 182–202, https://doi.org/10.1177/073401689301800203 . Search in Google Scholar

Huber, E., J. Huo, and J. D. Stephens. 2019. “Power, Policy, and Top Income Shares.” Socio-Economic Review 17 (2): 231–53, https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwx027 . Search in Google Scholar

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2017. Fiscal Monitor: Tackling Inequality . Washington: IMF. Search in Google Scholar

Jaumotte, F., and C. O. Buitron. 2015. “Power from the People.” Finance & Development 52 (1): 29–31. Search in Google Scholar

Jensen, C., and K. Van Kersbergen. 2017. The Politics of Inequality . London: Palgrave. Search in Google Scholar

Kawachi, I., N. E. Adler, and W. H. Dow. 2010. “Money, Schooling, and Health: Mechanisms and Causal Evidence.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1186 (1): 56–68, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05340.x . Search in Google Scholar

Leigh, A., C. Jencks, and T. Smeeding. 2009. “Health and Economic Inequality.” In The Oxford Book of Economic Equality , edited by W. Salverda, B. Nolan, and T. Smeeding, 384–405. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Search in Google Scholar

Marmot, M. 2015. The Health Gap: The Challenge of an Unequal World . London: Bloomsbury. Search in Google Scholar

Merton, R. 1938. “Social Structure and Anomie.” American Sociological Review 3 (5): 672–82, https://doi.org/10.2307/2084686 . Search in Google Scholar

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) . 2020. “Income Inequality” (Indicator) . Paris: OECD Publishing. Also available at https://data.oecd.org/inequality/income-inequality.htm . Search in Google Scholar

Ostry, J. D., P. Loungani, and D. Furceri. 2016. “ Neoliberalism: Oversold? ” Finance and Development 532: 38–41. Also available at https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2016/06/ostry.htm . Search in Google Scholar

Piketty, T. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century . Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Search in Google Scholar

Piketty, T. 2020. Capital and Ideology . Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Search in Google Scholar

Revenga, A. 1992. “Exporting Jobs? The Impact of Import Competition on Employment and Wages in U.S. Manufacturing.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 107 (1): 255–84, https://doi.org/10.2307/2118329 . Search in Google Scholar

Rosenfeld, J., and B. Western. 2011. “Unions, Norms, and the Rise in U.S. Wage Inequality.” American Sociological Review 78 (4): 513–37. Search in Google Scholar

Rowlingson, K. 2011. Does Income Inequality Cause Health and Social Problems? York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Search in Google Scholar

Saez, E., and M. Veall. 2005. “The Evolution of High Incomes in Northern America: Lessons from Canadian Evidence.” American Economic Review 95 (3): 831–49, https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828054201404 . Search in Google Scholar

Scheidel, W. 2017. The Great Leveller: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century . Princeton: Princeton University Press. Search in Google Scholar

Schrecker, T., and C. Bambra. 2015. How Politics Makes Us Sick: Neoliberal Epidemics . New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Search in Google Scholar

Shaxson, N. 2015. Ten Reasons to Defend the Corporation Tax . London: Tax Justice Network. Also available at http://www.taxjustice.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Ten_Reasons_Full_Report.pdf . Search in Google Scholar

Solt, F. 2020. “Measuring Income Inequality across Countries and over Time: The Standardized World Income Inequality Database.” Social Science Quarterly 101 (3): 1183–99. Version 9.0, https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12795 . Search in Google Scholar

Stiglitz, J. 2013. The Price of Inequality . London: Penguin Books. Search in Google Scholar

The Equality Trust . 2018. “The Spirit Level Data.” London. Also available at https://www.equalitytrust.org.uk/civicrm/contribute/transact?reset=1&id=5 . Search in Google Scholar

Thomas, A. 2016. Republic of Equals: Predistribution and Property-Owning Democracy . Oxford: Oxford University Press. Search in Google Scholar

Tridico, P. 2018. “The Determinants of Income Inequality in OECD Countries.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 42 (4): 1009–42, https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bex069 . Search in Google Scholar

Visser, J. 2019. ICTWSS Database . Version 6.1. Amsterdam: Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labour Studies (AIAS), University of Amsterdam. Search in Google Scholar

Whitworth, A. 2012. “Inequality and Crime across England: A Multilevel Modelling Approach.” Social Policy and Society 11 (1): 27–40, https://doi.org/10.1017/s1474746411000388 . Search in Google Scholar

Wilkinson, R. 1996. Unhealthy Societies: The Afflictions of Inequality . London: Routledge. Search in Google Scholar

Wilkinson, R., and K. Pickett. 2009. The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone . London: Penguin Books. Search in Google Scholar

Wilkinson, R., and K. Pickett. 2019. The Inner Level: How More Equal Societies Reduce Stress, Restore Sanity and Improve Everyone’s Well-Being . London: Penguin Books. Search in Google Scholar

Wiwad, D., B. Mercier, P. K. Piff, A. Shariff, and L. B. Aknin. 2021. “Recognizing the Impact of COVID-19 on the Poor Alters Attitudes towards Poverty and Inequality.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology , https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2020.104083 . Search in Google Scholar

World Economic Forum. 2020. The Global Social Mobility Report 2020 . Geneva: World Economic Forum. Also available at https://www3.weforum.org/docs/Global_Social_Mobility_Report.pdf . Search in Google Scholar

Zucman, G. 2015. The Hidden Wealth of Nations: The Scourge of Tax Havens . Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

- X / Twitter

Supplementary Materials

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

Journal and Issue

Articles in the same issue.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/62240797/6163925227_7c3e989d53_o.0.1520267162.0.jpg)

Everything you need to know about income inequality

Share this story.

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Everything you need to know about income inequality

What is income inequality.

Broadly speaking, income inequality refers to the fact that different people earn different amounts of money. The wider those earnings are dispersed, the more unequal they are. But that intuitive concept of dispersal can be defined in several different ways. Indeed, income itself is a somewhat ambiguous idea that can be defined in different ways.

All that said, in the contemporary United States income inequality has been increasing for several decades by essentially any measure. Similar trends are observed in most other rich countries. At the same time, on a global scale inequality is probably declining.

Inequality has become a hot topic in American politics in recent years. The Occupy Wall Street movement's slogans about the 99 percent versus the 1 percent have stirred an influential current in politics. In a December 2013 speech Barack Obama called inequality the "defining challenge of our time." Conservative politicians overwhelmingly disagree, and focus groups seem to indicate that the public prefers talk about "opportunity" to explicit discussion of inequality. Still, the trend toward more inequality shows no sign of halting and left-of-center figures are likely to keep it on the policy agenda.

How do you measure inequality?

Inequality can be defined or measured in a number of different ways.

One traditional approach was to compare the income of a relatively broad swath of affluent people — the top ten percent of the income distribution (the top decile) or the top twenty percent (the top quintile) — to the national median or average. One big advantage of this approach is that the relevant data is readily available from the Census Bureau and other survey-based sources. A major downside is that this method doesn't tell you much of anything about the earnings of the very highest earners — people in the top 1 percent, for example.

A newer line of research pioneered by Emmanuel Saez, Thomas Piketty, and their collaborators at the World Top Incomes Database has been to use tax records to focus on the incomes of the very top of the distribution. That lets you understand the top 1 percent, the top 0.1 percent, and even the top 0.001 percent. This work has been the basis of much subsequent discussion about the 99 percent versus the 1 percent but the even finer slices are interesting, too.

It is also at times interesting to look at the gap between the poor (say the bottom 10 percent) and the median household. Metrics that define poverty in relative terms tend to, in effect, look at this kind of inequality. So discussions of the living standards of the poor are normally framed in terms of poverty rather than inequality.

Last but by no means least, there is a widely used summary method of calculating inequality that is known as the gini coefficient . A gini coefficient of 0 corresponds to precise equality while a gini coefficient of 1 corresponds to a state of total inequality.

What is a gini coefficient?

The gini coefficient is the most widely used single-summary number for judging the level of inequality in a particular country or region. Unfortunately, it does not lend itself to a particularly obvious intuitive interpretation.

The way it works is to start with a Lorenz curve :

The horizontal axis on this chart represents cumulative shares of the population. The vertical axis is cumulative shares of income. Trace the curve to the 50 percent point, in other words, and you'll see what share of national income the bottom 50 percent of the income distribution earns. Trace the curve to the 75 percent point and you'll see what share the bottom three quarters earn.

In a perfectly equal society, the bottom X percent would earn X percent of the income for any value of X and the Lorenz curve would be a perfect 45 degree angle. In unequal societies, the bottom X percent always earn less than X percent of the income. Except that the bottom 100 percent by definition must earn 100 percent of the income. So an unequal society is always a society whose Lorenz curve swoops below the 45 degree line and then converges with it at the very end.

The 45 degree angle divides a square in half. The Lorenz curve divides that half into two sections — A and B. The gini coefficient equals A / (A+B).

The downside to using a gini coefficient to describe a society is that (as you can see above) it's an incredibly abstract idea that's difficult to verbally describe. The advantage to using a gini coefficent is that in principle it summarizes all the information about the distribution of income and thus facilitates easy comparisons.

Is inequality bad?

There is considerable disagreement about this point.

One prominent argument in political philosophy, found in John Rawls' book A Theory of Justice , holds that inequalities in economic and social status can be justified to the extent that they serve the interests of the least-fortunate class in society but not otherwise. In other words, if society of impoverished subsistence farmers finds that the only way to broadly raise living standards is to industrialize and create a small class of rich factory owners, that's okay. Or if paying doctors substantially more than the average person's salary is the way to induce people to master the craft of medicine and cure the sick, that's okay too. Exactly how much inequality this approach (dubbed "the difference principle" by Rawls) would countenance in practice is difficult to say.

A different criticism of inequality appeals to an idea known as the declining marginal utility of money . In other words the exact same amount of money means different things to the real living standards of different people. A modest financial loss could mean foregone food for a poor person, foregone preventive medical care for someone further up the economic food chain, a foregone vacation for someone more prosperous than that, a somewhat-less-fancy vacation for someone even more prosperous than that, and it would be completely imperceptible to a genuinely rich person. In that view, inequality-reducing redistribution could increase overall human well-being.

Still on both of these views what's bad about inequality is that it's a sign of potentially foregone opportunity to raise the absolute living standards of the less-fortunate. There are also various efforts to demonstrate that inequality per se is a cause of problems.

Many of these ideas are summed up in The Spirit Level by Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson, which purports to show that inequality as such drives a number of social ills including low life expectancy, obesity, and poor educational outcomes. Another line of research claims to show that inequality is associated with a lack of social mobility. Last, there is a long tradition of argument that massive levels of economic inequality subvert democratic politics by concentrating excessive political influence in the hands of economic elites.

Counterposed to all of this is a long and broadly libertarian line of argumentation that there's nothing wrong with some people becoming extraordinarily rich if they happen to provide products or services that are broadly in demand.

How economically unequal is the United States?

By international standards, the United States is a very unequal country. Here's our gini coefficient compared to the other major rich economies:

The contemporary United States is also unequal by historical terms. Here's a look at the top ten percent's share of income over time:

One nuance to international comparisons is that the United States is considerably larger than other rich countries. If you look at inequality across the entire European Union rather than within a single European country, the EU as a whole is less equal than almost any particular European state. Conversely, if you consider the United States separately the vast majority of states are more equal than the country as a whole.

Is inequality rising because the rich are getting richer or because the poor are getting poorer?

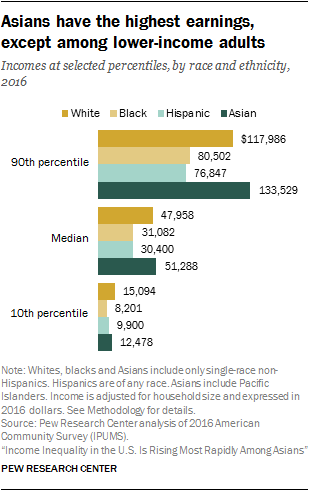

Mostly because the rich are getting richer. A vast swath of American households have been in financial distress since the economic crisis of 2008, but taking the long view incomes have tended to rise across the board. They've simply risen dramatically faster for the highest-income households than for the rest of the population:

Why is inequality rising?

There is some disagreement about this and also some nuance as to exactly which aspect of inequality we're talking about and what kind. Some of the most prominent accounts:

- Skill-biased technological change. Technological improvements raise incomes, but they do so unevenly. Rewards disproportionately go to highly educated workers. On this view, rising inequality reflects slowing educational progress and better schooling is the key solution. This has been the traditionally dominant view in economics, but it doesn't explain the specific rise of the top 1 percent very well.

- Immigration. Importing low-skilled workers to do low-paid jobs tends to raise measured income inequality. David Card estimates immigration to be the cause of about 5 percent of the total rise in inequality .

- Decline of labor unions. Labor unions reduce inequality both by raising wages at the low end and constraining them at the high end. Bruce Western and Jake Rosenfeld estimate that the decline of labor unions as a force in the American economy is responsible for 20 to 33 percent of the overall rise in inequality .

- Trade. Growing international trade with lower-wage countries such as China seems to have reduced the wage share of overall national income , boosting the incomes of people with large stock holdings.

- Superstar effects. Because the world is bigger and richer in 2014 than it was in 1964, being a "star" performer — the most popular athlete, author, or singer — is more lucrative than it used to be.

- Executives and Wall Street . Increased incomes for CEOs and financial sector professionals account for 58 percent of the top 1 percent of the income distribution and 67 percent of the top 0.1 percent. So the specific dynamics of compensation in those areas are wielding a big influence.

- Minimum wage. David Autor, Alan Manning, and Christopher Smith find that about a third (or possibly as much as half) of the growth in inequality between the median and the bottom ten percent is due to the declining real value of the minimum wage. This is different from the issues about the top end pulling away that normally dominate political discussions of inequality, but it's a noteworthy finding nonetheless.

- The fundamental nature of capitalism. Thomas Piketty has made waves lately with his new book Capital in the 21st Century, which argues that very high levels of inequality are the natural state of market economies . In his view, it's the economic equality of the mid-twentieth century that needs explaining, not today's inequality.

How does inequality relate to opportunity and upward mobility?

One common political response to rising inequality has been to argue that what really matters is economic opportunity : do people have a chance to rise to the top? Alan Krueger, the then-chair of the White House Council on Economic Advisors challenged this notion in 2012 with what he called "The Great Gatsby Curve." It shows a strong correlation between national income inequality and intergenerational mobility:

UC Davis economic historian Gregory Clark has challenged the link in an even more profound way by arguing that properly measured, social mobility is extremely low everywhere and always has been, even in places like Sweden .

What can the government do to reduce inequality?

The most straightforward thing the government could do to reduce income inequality would be to tax the rich more heavily and give additional money to the poor. The United States has some of the lowest taxes of any rich country so there's certainly room to do more.

Laws that were friendlier to labor union organizing and to the activities of existing labor unions would also likely reduce inequality. So would altering the mix of immigrants to the United States to include a higher proportion of skilled workers. So would improvements in educational attainment. But these kinds of measures speak more to the gap between the top 10 or 20 percent and the rest, not to the gap between the top 1 or 0.1 percent and the average.

For incomes at the very top, there is taxation and then there is the idea of directly targeting the sources of high-income individuals' earnings. That could mean stricter regulation of the financial sector to reduce earnings on Wall Street, or weaker protections for the holders of copyrights to reduce the earnings of superstars.

How does income inequality relate to wealth inequality?

Income is the flow of money that you receive. For most people it's your wages or salary. For some people, there might be dividends, interest payments, or rent thrown in. Wealth is how many financial assets you have stockpiled. The equity in your home, your bank account, your retirement account, or other stocks and bonds you may have accumulated.

There are two main reasons for this.

One is that the bottom quarter or so of the population has zero or negative net wealth , due to student loans, underwater mortgages, credit card debt, auto loans, or other debt instruments. Nobody has negative income and very few people have zero income when government benefits are factored in.

The other is that wealth leads to income. A billionaire who owns tons of stock is going to earn substantial dividends from his stock holdings. Some of that income will be saved, and turn into further wealth. This tends to put the wealth of the wealthiest on an upward trajectory unless something like a war or a depression or a massive political intervention interferes.

What's happening to inequality elsewhere in the world?

Broadly speaking, income inequality appears to be on the rise in almost all developed countries. That was the conclusion of a recent report on the subject by the Organization Economics Cooperation and Development (OECD) .

What's happening to global income inequality?

Even as inequality rises in most rich countries there is evidence that global inequality is declining somewhat from a very high level. World Bank economist Branko Milanovic made the following comparison of the global gini coefficient to the gini coefficients of a few specific countries:

On the other hand, the richest of the world's rich — the billionaires — are getting richer at a rapid pace according to Forbes' annual tally:

Why do some economists say the increase in inequality has been overstated?

While income inequality has been a growing subject of public discussion and most authorities take it for granted at this point that incomes in the United States have grown very unequal, there is some dispute about this. Richard Burkhauser, a Cornell University economist, and Scott Winship, a policy analyst at the Manhattan Institute, have been the leading proponents of the view that the new conventional wisdom overstates the increase in inequality.

The dispute hinged on a variety of conceptual issues, but also on the existence of different sources of data about income. Let's start with the data, and then get into the conceptual problems.

Census vs IRS

The biggest, broadest difference between inequality measures you will see is that some economists (following the work of Thomas Piketty and Emanuel Saez) look at tax return data from the Internal Revenue Service while others rely on the Current Population Survey (CPS) data from the Census Bureau.

The big advantage of the CPS is that it lets you find out information about non-cash compensation — mostly health insurance — and government benefits programs, both of which are important to middle- and working-class economic welfare.

The big disadvantage of the CPS is that because it's based on broad statistical counting, it doesn't give you insight into the top 1 percent, top 0.1 percent, or top 0.01 percent of the population. And since a very large share of the top 5 percent's overall income is in the hands of a very small elite (the top 0.1 percent, say) the CPS ends up undercounting the overall high-end cash income.

Household size

The average size of the American household has shrunk over time, meaning that income-per-household-member for the middle class has grown faster than income-per-household. Some people feel that "income stagnation" claims should be adjusted accordingly (which gives you a better sense of average living standards) while others do not (which gives you a better sense of the state of the labor market).

Taxes and transfers

Since 1979, the tax burden on poor and middle class families has shrunk. Social welfare expenditures (primarily health care programs like Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act) have risen, and a larger share of the population is receiving Social Security and Medicare benefits. All this means that if consider middle class incomes after taxes and transfers , you get a considerably rosier picture than if you consider pre-tax income. For similar reasons, IRS data will tend to suggest that retirees are very poor by neglecting the considerable value of government programs that lift the elderly out of poverty.

Somewhat ironically, the people who insist on including tax and transfer data in their inequality metrics tend to be associated with the political right while the people who argue in favor of progressive taxation and a generous welfare state tend to want to leave this stuff out of their inequality metrics.

Capital gains

Another conceptual issue relates to the treatment of capital gains, in other words profits earned on investments. Including IRS data on capital gains adds a lot to the incomes at the high end, because very rich people own the bulk of stock. At the same time, since profits from the sale of owner occupied housing are not normally taxed, middle class households' main form of capital gains income generally doesn't show up in this dataset.

Another issue with IRS capital gains data is that investment profits are taxed when they are realized, i.e. you pay tax on stock market profits when you sell shares. Combine that with the stock market's tendency to fluctuate up and down and this creates a very unstable income series. That, in turn, means that estimates of high-end income gains over a given period can be highly sensitive to your use of start and end dates. The realization issue also makes a difference for middle class incomes. Middle class workers tend to hold stock in tax-advantaged accounts like 401(k)s and IRAs. The value of these portfolios builds up, tax free, over time. The gains are then realized (and taxed) after retirement, when labor income has dropped to zero.

Health insurance