Read our research on: Gun Policy | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

The public, the political system and american democracy, most say ‘design and structure’ of government need big changes, survey report.

The public’s criticisms of the political system run the gamut, from a failure to hold elected officials accountable to a lack of transparency in government. And just a third say the phrase “people agree on basic facts even if they disagree politically” describes this country well today.

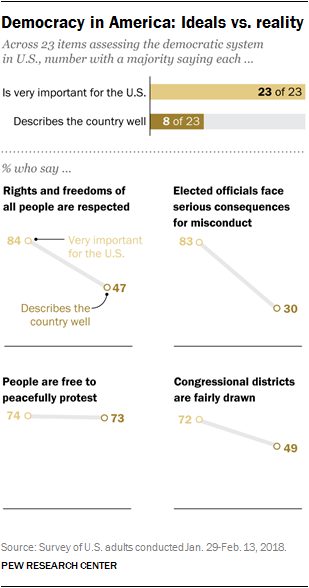

The perceived shortcomings encompass some of the core elements of American democracy. An overwhelming share of the public (84%) says it is very important that “the rights and freedoms of all people are respected.” Yet just 47% say this describes the country very or somewhat well; slightly more (53%) say it does not.

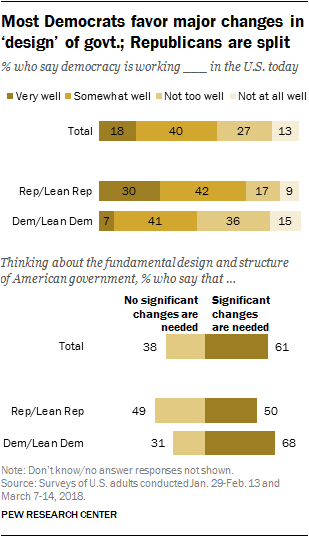

Despite these criticisms, most Americans say democracy is working well in the United States – though relatively few say it is working very well. At the same time, there is broad support for making sweeping changes to the political system: 61% say “significant changes” are needed in the fundamental “design and structure” of American government to make it work for current times.

The public sends mixed signals about how the American political system should be changed, and no proposals attract bipartisan support. Yet in views of how many of the specific aspects of the political system are working, both Republicans and Democrats express dissatisfaction.

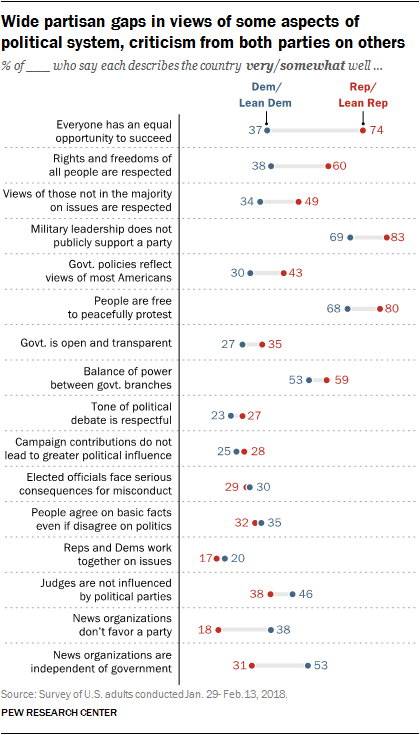

To be sure, there are some positives. A sizable majority of Americans (74%) say the military leadership in the U.S. does not publicly support one party over another, and nearly as many (73%) say the phrase “people are free to peacefully protest” describes this country very or somewhat well.

In general, however, there is a striking mismatch between the public’s goals for American democracy and its views of whether they are being fulfilled. On 23 specific measures assessing democracy, the political system and elections in the United States – each widely regarded by the public as very important – there are only eight on which majorities say the country is doing even somewhat well.

The new survey of the public’s views of democracy and the political system by Pew Research Center was conducted online Jan. 29-Feb. 13 among 4,656 adults. It was supplemented by a survey conducted March 7-14 among 1,466 adults on landlines and cellphones.

Among the major findings:

Mixed views of structural changes in the political system. The surveys examine several possible changes to representative democracy in the United States. Most Americans reject the idea of amending the Constitution to give states with larger populations more seats in the U.S. Senate, and there is little support for expanding the size of the House of Representatives. As in the past, however, a majority (55%) supports changing the way presidents are elected so that the candidate who receives the most total votes nationwide – rather than a majority in the Electoral College – wins the presidency.

A majority says Trump lacks respect for democratic institutions. Fewer than half of Americans (45%) say Donald Trump has a great deal or fair amount of respect for the country’s democratic institutions and traditions, while 54% say he has not too much respect or no respect. These views are deeply split along partisan and ideological lines. Most conservative Republicans (55%) say Trump has a “great deal” of respect for democratic institutions; most liberal Democrats (60%) say he has no respect “at all” for these traditions and institutions.

Few say tone of political debate is ‘respectful.’ Just a quarter of Americans say “the tone of debate among political leaders is respectful” is a statement that describes the country well. However, the public is more divided in general views about tone and discourse: 55% say too many people are “easily offended” over the language others use; 45% say people need to be more careful in using language “to avoid offending” others.

Cynicism about money and politics. Most Americans think that those who donate a lot of money to elected officials have more political influence than others. An overwhelming majority (77%) supports limits on the amount of money individuals and organizations can spend on political campaigns and issues. And nearly two-thirds of Americans (65%) say new laws could be effective in reducing the role of money in politics.

Most are aware of basic facts about political system and democracy. Overwhelming shares correctly identify the constitutional right guaranteed by the First Amendment to the Constitution and know the role of the Electoral College. A narrower majority knows how a tied vote is broken in the Senate, while fewer than half know the number of votes needed to break a Senate filibuster. ( Take the civics knowledge quiz .)

Democracy seen as working well, but most say ‘significant changes’ are needed

Overall, nearly six-in-ten Americans (58%) say democracy in the United States is working very or somewhat well, though just 18% say it is working very well. Four-in-ten say it is working not too well or not at all well.

Republicans have more positive views of the way democracy is working than do Democrats: 72% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents say democracy in the U.S. is working at least somewhat well, though only 30% say it is working very well. Among Democrats and Democratic leaners, 48% say democracy works at least somewhat well, with just 7% saying it is working very well.

More Democrats than Republicans say significant changes are needed in the design and structure of government. By more than two-to-one (68% to 31%), Democrats say significant changes are needed. Republicans are evenly divided: 50% say significant changes are needed in the structure of government, while 49% say the current structure serves the country well and does not need significant changes.

The public has mixed evaluations of the nation’s political system compared with those of other developed countries. About four-in-ten say the U.S. political system is the best in the world (15%) or above average (26%); most say it is average (28%) or below average (29%), when compared with other developed nations. Several other national institutions and aspects of life in the U.S. – including the military, standard of living and scientific achievements – are more highly rated than the political system.

Republicans are about twice as likely as Democrats to say the U.S. political system is best in the world or above average (58% vs. 27%). As recently as four years ago, there were no partisan differences in these opinions.

Bipartisan criticism of political system in a number of areas

In most cases, however, partisans differ on how well the country lives up to democratic ideals – or majorities in both parties say it is falling short.

Some of the most pronounced partisan differences are in views of equal opportunity in the U.S. and whether the rights and freedoms of all people are respected.

Republicans are twice as likely as Democrats to say “everyone has an equal opportunity to succeed” describes the United States very or somewhat well (74% vs. 37%).

A majority of Republicans (60%) say the rights and freedoms of all people are respected in the United States, compared with just 38% of Democrats.

And while only about half of Republicans (49%) say the country does well in respecting “the views of people who are not in the majority on issues,” even fewer Democrats (34%) say this.

No more than about a third in either party say elected officials who engage in misconduct face serious consequences or that government “conducts its work openly and transparently.” Comparably small shares in both parties (28% of Republicans, 25% of Democrats) say the following sentence describes the country well: “People who give a lot of money to elected officials do not have more political influence than other people.”

Fewer than half in both parties also say news organizations do not favor one political party, though Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say this describes the country well (38% vs. 18%). There also is skepticism in both parties about the political independence of judges. Nearly half of Democrats (46%) and 38% of Republicans say judges are not influenced by political parties.

Partisan gaps in opinions about many aspects of U.S. elections

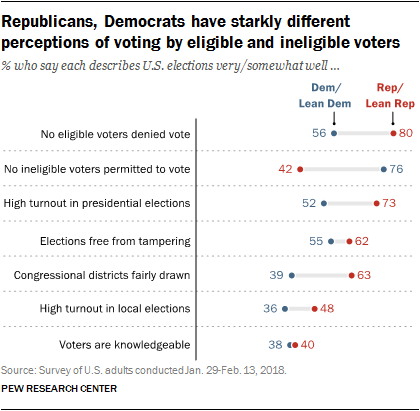

Overwhelming shares in both parties say it is very important that elections are free from tampering (91% of Republicans, 88% of Democrats say this) and that voters are knowledgeable about candidates and issues (78% in both parties).

But there are some notable differences: Republicans are almost 30 percentage points more likely than Democrats to say it is very important that “no ineligible voters are permitted to vote” (83% of Republicans vs. 55% of Democrats).

And while majorities in both parties say high turnout in presidential elections is very important, more Democrats (76%) than Republicans (64%) prioritize high voter turnout.

The differences are even starker in evaluations of how well the country is doing in fulfilling many of these objectives. Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say that “no eligible voters are prevented from voting” describes elections in the U.S. very or somewhat well (80% vs. 56%). By contrast, more Democrats (76%) than Republicans (42%) say “no ineligible voters are permitted to vote” describes elections well.

Democrats – particularly politically engaged Democrats – are critical of the process for determining congressional districts. A majority of Republicans (63%) say the way congressional voting districts are determined is fair and reasonable compared with just 39% of Democrats; among Democrats who are highly politically engaged, just 29% say the process is fair.

And fewer Democrats than Republicans consider voter turnout for elections in the U.S. – both presidential and local – to be “high.” Nearly three-quarters of Republicans (73%) say “there is high voter turnout in presidential elections” describes elections well, compared with only about half of Democrats (52%).

Still, there are a few points of relative partisan agreement: Majorities in both parties (62% of Republicans, 55% of Democrats) say “elections are free from tampering.” And Republicans and Democrats are about equally skeptical about whether voters are knowledgeable about candidates and issues (40% of Republicans, 38% of Democrats).

Facts are more important than ever

In times of uncertainty, good decisions demand good data. Please support our research with a financial contribution.

Report Materials

Table of Contents

Around the world, people who trust others are more supportive of international cooperation, two-thirds of u.s. adults say they’ve seen their own news sources report facts meant to favor one side, in views of u.s. democracy, widening partisan divides over freedom to peacefully protest, experts predict more digital innovation by 2030 aimed at enhancing democracy, the state of americans’ trust in each other amid the covid-19 pandemic, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Alexis de Tocqueville

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 7, 2019 | Original: November 9, 2009

French sociologist and political theorist Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859) traveled to the United States in 1831 to study its prisons and returned with a wealth of broader observations that he codified in “Democracy in America” (1835), one of the most influential books of the 19th century. With its trenchant observations on equality and individualism, Tocqueville’s work remains a valuable explanation of America to Europeans and of Americans to themselves.

Alexis de Tocqueville: Early Life

Alexis de Tocqueville was born in 1805 into an aristocratic family recently rocked by France’s revolutionary upheavals. Both of his parents had been jailed during the Reign of Terror. After attending college in Metz, Tocqueville studied law in Paris and was appointed a magistrate in Versailles, where he met his future wife and befriended a fellow lawyer named Gustave de Beaumont.

Did you know? During his travels in the United States, one of the first things that surprised Alexis de Tocqueville about American culture was how early everyone seemed to eat breakfast.

In 1830 Louis-Philippe, the “bourgeois monarch,” took the French throne, and Tocqueville’s career ambitions were temporarily blocked. Unable to advance, he and Beaumont secured permission to carry out a study of the American penal system, and in April 1831 they set sail for Rhode Island .

Alexis de Tocqueville: American Travels

From Sing-Sing Prison to the Michigan woods, from New Orleans to the White House , Tocqueville and Beaumont traveled for nine months by steamboat, by stagecoach, on horseback and in canoes, visiting America’s penitentiaries and quite a bit in between. In Pennsylvania , Tocqueville spent a week interviewing every prisoner in the Eastern State Penitentiary. In Washington , D.C., he called on President Andrew Jackson during visiting hours and exchanged pleasantries.

The travelers returned to France in 1832. They quickly published their report, “On the Penitentiary System in the United States and Its Application in France,” written largely by Beaumont. Tocqueville set to work on a broader analysis of American culture and politics, published in 1835 as “Democracy in America.”

Alexis de Tocqueville: “Democracy in America”

As “Democracy in America” revealed, Tocqueville believed that equality was the great political and social idea of his era, and he thought that the United States offered the most advanced example of equality in action. He admired American individualism but warned that a society of individuals can easily become atomized and paradoxically uniform when “every citizen, being assimilated to all the rest, is lost in the crowd.” He felt that a society of individuals lacked the intermediate social structures—such as those provided by traditional hierarchies—to mediate relations with the state. The result could be a democratic “tyranny of the majority” in which individual rights were compromised.

Tocqueville was impressed by much of what he saw in American life, admiring the stability of its economy and wondering at the popularity of its churches. He also noted the irony of the freedom-loving nation’s mistreatment of Native Americans and its embrace of slavery.

Alexis de Tocqueville: Later Life

In 1839, as the second volume of “Democracy in America” neared publication, Tocqueville reentered political life, serving as a deputy in the French assembly. After the Europe-wide revolutions of 1848, he served briefly as Louis Napoleon’s foreign minister before being forced out of politics again when he refused to support Louis Napoleon’s coup.

He retired to his family estate in Normandy and began writing a history of modern France, the first volume of which was published as “The Old Regime and the French Revolution” (1856). He blamed the French Revolution on corruption among the nobility and on the political disillusionment of the French population. Tocqueville’s plans for later volumes were cut short by his death from tuberculosis in 1859.

Alexis de Tocqueville: Legacy

Tocqueville’s works shaped 19th-century discussions of liberalism and equality, and were rediscovered in the 20th century as sociologists debated the causes and cures of tyranny. “Democracy in America” remains widely read and even more widely quoted by politicians, philosophers, historians and anyone seeking to understand the American character.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

By the People: Essays on Democracy

Harvard Kennedy School faculty explore aspects of democracy in their own words—from increasing civic participation and decreasing extreme partisanship to strengthening democratic institutions and making them more fair.

Winter 2020

By Archon Fung , Nancy Gibbs , Tarek Masoud , Julia Minson , Cornell William Brooks , Jane Mansbridge , Arthur Brooks , Pippa Norris , Benjamin Schneer

The basic terms of democratic governance are shifting before our eyes, and we don’t know what the future holds. Some fear the rise of hateful populism and the collapse of democratic norms and practices. Others see opportunities for marginalized people and groups to exercise greater voice and influence. At the Kennedy School, we are striving to produce ideas and insights to meet these great uncertainties and to help make democratic governance successful in the future. In the pages that follow, you can read about the varied ways our faculty members think about facets of democracy and democratic institutions and making democracy better in practice.

Explore essays on democracy

Archon fung: we voted, nancy gibbs: truth and trust, tarek masoud: a fragile state, julia minson: just listen, cornell william brooks: democracy behind bars, jane mansbridge: a teachable skill, arthur brooks: healthy competition, pippa norris: kicking the sandcastle, benjamin schneer: drawing a line.

Get smart & reliable public policy insights right in your inbox.

‘America Is a Republic, Not a Democracy’ Is a Dangerous—And Wrong—Argument

Enabling sustained minority rule at the national level is not a feature of our constitutional design, but a perversion of it.

Dependent on a minority of the population to hold national power, Republicans such as Senator Mike Lee of Utah have taken to reminding the public that “we’re not a democracy.” It is quaint that so many Republicans, embracing a president who routinely tramples constitutional norms, have suddenly found their voice in pointing out that, formally, the country is a republic. There is some truth to this insistence. But it is mostly disingenuous. The Constitution was meant to foster a complex form of majority rule, not enable minority rule.

The founding generation was deeply skeptical of what it called “pure” democracy and defended the American experiment as “wholly republican.” To take this as a rejection of democracy misses how the idea of government by the people, including both a democracy and a republic, was understood when the Constitution was drafted and ratified. It misses, too, how we understand the idea of democracy today.

George Packer: Republicans are suddenly afraid of democracy

When founding thinkers such as James Madison spoke of democracy, they were usually referring to direct democracy, what Madison frequently labeled “pure” democracy. Madison made the distinction between a republic and a direct democracy exquisitely clear in “ Federalist No. 14 ”: “In a democracy, the people meet and exercise the government in person; in a republic, they assemble and administer it by their representatives and agents. A democracy, consequently, will be confined to a small spot. A republic may be extended over a large region.” Both a democracy and a republic were popular forms of government: Each drew its legitimacy from the people and depended on rule by the people. The crucial difference was that a republic relied on representation, while in a “pure” democracy, the people represented themselves.

At the time of the founding, a narrow vision of the people prevailed. Black people were largely excluded from the terms of citizenship, and slavery was a reality, even when frowned upon, that existed alongside an insistence on self-government. What this generation considered either a democracy or a republic is troublesome to us insofar as it largely granted only white men the full rights of citizens, albeit with some exceptions. America could not be considered a truly popular government until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which commanded equal citizenship for Black Americans. Yet this triumph was rooted in the founding generation’s insistence on what we would come to call democracy.

The history of democracy as grasped by the Founders, drawn largely from the ancient world, revealed that overbearing majorities could all too easily lend themselves to mob rule, dominating minorities and trampling individual rights. Democracy was also susceptible to demagogues—men of “factious tempers” and “sinister designs,” as Madison put it in “Federalist No. 10”—who relied on “vicious arts” to betray the interests of the people. Madison nevertheless sought to defend popular government—the rule of the many—rather than retreat to the rule of the few.

American constitutional design can best be understood as an effort to establish a sober form of democracy. It did so by embracing representation, the separation of powers, checks and balances, and the protection of individual rights—all concepts that were unknown in the ancient world where democracy had earned its poor reputation.

In “Federalist No. 10” and “Federalist No. 51,” the seminal papers, Madison argued that a large republic with a diversity of interests capped by the separation of powers and checks and balances would help provide the solution to the ills of popular government. In a large and diverse society, populist passions are likely to dissipate, as no single group can easily dominate. If such intemperate passions come from a minority of the population, the “ republican principle ,” by which Madison meant majority rule , will allow the defeat of “ sinister views by regular vote .” More problematic are passionate groups that come together as a majority. The large republic with a diversity of interests makes this unlikely, particularly when its separation of powers works to filter and tame such passions by incentivizing the development of complex democratic majorities : “In the extended republic of the United States, and among the great variety of interests, parties, and sects which it embraces, a coalition of a majority of the whole society could seldom take place on any other principles than those of justice and the general good.” Madison had previewed this argument at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 using the term democracy , arguing that a diversity of interests was “the only defense against the inconveniences of democracy consistent with the democratic form of government.”

Jeffrey Rosen: America is living James Madison’s nightmare

Yet while dependent on the people, the Constitution did not embrace simple majoritarian democracy. The states, with unequal populations, got equal representation in the Senate. The Electoral College also gave the states weight as states in selecting the president. But the centrality of states, a concession to political reality, was balanced by the House of Representatives, where the principle of representation by population prevailed, and which would make up the overwhelming number of electoral votes when selecting a president.

But none of this justified minority rule, which was at odds with the “republican principle.” Madison’s design remained one of popular government precisely because it would require the building of political majorities over time. As Madison argued in “ Federalist No. 63, ” “The cool and deliberate sense of the community ought, in all governments, and actually will, in all free governments, ultimately prevail over the views of its rulers.”

Alexander Hamilton, one of Madison’s co-authors of The Federalist Papers , echoed this argument. Hamilton made the case for popular government and even called it democracy: “A representative democracy, where the right of election is well secured and regulated & the exercise of the legislative, executive and judiciary authorities, is vested in select persons, chosen really and not nominally by the people, will in my opinion be most likely to be happy, regular and durable.”

The American experiment, as advanced by Hamilton and Madison, sought to redeem the cause of popular government against its checkered history. Given the success of the experiment by the standards of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, we would come to use the term democracy as a stand-in for representative democracy, as distinct from direct democracy.

Consider that President Abraham Lincoln, facing a civil war, which he termed the great test of popular government, used constitutional republic and democracy synonymously, eloquently casting the American experiment as government of the people, by the people, and for the people. And whatever the complexities of American constitutional design, Lincoln insisted , “the rule of a minority, as a permanent arrangement, is wholly inadmissible.” Indeed, Lincoln offered a definition of popular government that can guide our understanding of a democracy—or a republic—today: “A majority, held in restraint by constitutional checks, and limitations, and always changing easily, with deliberate changes of popular opinions and sentiments, is the only true sovereign of a free people.”

The greatest shortcoming of the American experiment was its limited vision of the people, which excluded Black people, women, and others from meaningful citizenship, diminishing popular government’s cause. According to Lincoln, extending meaningful citizenship so that “all should have an equal chance” was the basis on which the country could be “saved.” The expansion of we the people was behind the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments ratified in the wake of the Civil War. The Fourteenth recognized that all persons born in the U.S. were citizens of the country and entitled to the privileges and immunities of citizenship. The Fifteenth secured the vote for Black men. Subsequent amendments, the Nineteenth, Twenty-Fourth, and Twenty-Sixth, granted women the right to vote, prohibited poll taxes in national elections, and lowered the voting age to 18. Progress has been slow— and s ometimes halted, as is evident from current efforts to limit voting rights —and the country has struggled to become the democratic republic first set in motion two centuries ago. At the same time, it has also sought to find the right republican constraints on the evolving body of citizens, so that majority rule—but not factious tempers—can prevail.

Adam Serwer: The Supreme Court is helping Republicans rig elections

Perhaps the most significant stumbling block has been the states themselves. In the 1790 census, taken shortly after the Constitution was ratified, America’s largest state, Virginia, was roughly 13 times larger than its smallest state, Delaware. Today, California is roughly 78 times larger than Wyoming. This sort of disparity has deeply shaped the Senate, which gives a minority of the population a disproportionate influence on national policy choices. Similarly, in the Electoral College, small states get a disproportionate say on who becomes president. Each of California’s electoral votes is estimated to represent 700,000-plus people, while one of Wyoming’s speaks for just under 200,000 people.

Subsequent to 1988, the Republican presidential candidate has prevailed in the Electoral College in three out of seven elections, but won the popular vote only once (2004). If President Trump is reelected, it will almost certainly be because he once again prevailed in the Electoral College while losing the popular vote. If this were to occur, he would be the only two-term president to never win a plurality of the popular vote. In 2020, Trump is the first candidate in American history to campaign for the presidency without making any effort to win the popular vote, appealing only to the people who will deliver him an Electoral College win. If the polls are any indication, more Americans may vote for Vice President Biden than have ever voted for a presidential candidate, and he could still lose the presidency. In the past, losing the popular vote while winning the Electoral College was rare. Given current trends, minority rule could become routine. Many Republicans are actively embracing this position with the insistence that we are, after all, a republic, not a democracy.

They have also dispensed with the notion of building democratic majorities to govern, making no effort on health care, immigration, or a crucial second round of economic relief in the face of COVID-19. Instead, revealing contempt for the democratic norms they insisted on when President Barack Obama sought to fill a vacant Supreme Court seat, Republicans in the Senate have brazenly wielded their power to entrench a Republican majority on the Supreme Court by rushing to confirm Justice Amy Coney Barrett. The Senate Judiciary Committee vote to approve Barrett also illuminates the disparity in popular representation: The 12 Republican senators who voted to approve of Barrett’s nomination represented 9 million fewer people than the 10 Democratic senators who chose not to vote. Similarly, the 52 Republican senators who voted to confirm Barrett represented 17 million fewer people than the 48 senators who voted against her. And the Court Barrett is joining, made up of six Republican appointees (half of whom were appointed by a president who lost the popular vote) to three Democratic appointees, has been quite skeptical of voting rights—a severe blow to the “democracy” part of a democratic republic. In 2013’s Shelby County v. Holder , the Court struck down a section of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that allowed the federal government to preempt changes in voting regulations from states with a history of racial discrimination.

As Adam Serwer recently wrote in these pages , “ Shelby County ushered in a new era of experimentation among Republican politicians in restricting the electorate, often along racial lines.” Republicans are eager to shrink the electorate. Ostensibly seeking to prevent voting fraud, which studies have continually shown is a nonexistent problem, Republicans support efforts to make voting more difficult—especially for minorities, who do not tend to vote Republican. The Republican governor of Texas, in the midst of a pandemic when more people are voting by mail, limited the number of drop-off locations for absentee ballots to one per county. Loving, with a population of 169, has one drop-off location; Harris, with a population of 4.7 million (majority nonwhite), also has one drop-off location. States controlled by Republicans, such as Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas, have also closed polling places, making voters in predominantly minority communities stand in line for hours to cast their ballot.

Who counts as a full and equal citizen—as part of we the people —has shrunk in the Republican vision. Arguing against statehood for the District of Columbia, which has 200,000 more people than the state of Wyoming, Senator Tom Cotton from Arkansas said Wyoming is entitled to representation because it is “a well-rounded working-class state.” It is also overwhelmingly white. In contrast, D.C. is 50 percent nonwhite.

High-minded claims that we are not a democracy surreptitiously fuse republic with minority rule rather than popular government. Enabling sustained minority rule at the national level is not a feature of our constitutional design, but a perversion of it. Routine minority rule is neither desirable nor sustainable, and makes it difficult to characterize the country as either a democracy or a republic. We should see this as a constitutional failure demanding constitutional reform.

This story is part of the project “ The Battle for the Constitution ,” in partnership with the National Constitution Center .

- Lesson Plans

- Teacher's Guides

- Media Resources

Democracy in America: Alexis de Tocqueville's Introduction

Theodore Chasseriau, Alexis Charles Henry de Tocqueville, Representant du Peuple , 1848. Lithograph, Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris.

Wikimedia Commons

In 1831 an ambitious and unusually perceptive twenty-five-year-old French aristocrat visited the United States. Alexis de Tocqueville’s official purpose was to study the American penal system, but his real interest was America herself. He spent nine months criss-crossing the young country, traveling mostly by steamboat, but also sometimes on horseback and by foot. He visited the bustling Eastern cities, explored the wilderness on the northwestern frontier, and had several adventures on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. He even stayed in a log cabin. Throughout, he spoke to Americans of every rank and profession, including two presidents and Charles Carroll, the last surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence. Tocqueville’s sojourn in America did lead to the writing of a book on the American penal system, but its much more important result was the reflection on equality and freedom known as Democracy in America . This great book remains arguably one of the two most important books on America political life, the Federalist Papers being the other one.

Democracy in America is a large book in two volumes (published five years apart, in 1835 and 1840). Volume One describes and analyzes American conditions and political institutions, while Volume Two examines the effect of American democracy on what we would call culture (literature, economics, the family, religion, etc.). The reason for Tocqueville’s interest in these themes is explained in a general Introduction to the whole work. There we learn that although Tocqueville was an aristocrat, he believed that the world was undergoing a “great democratic revolution,” that it is inevitably and irreversibly becoming more and more democratic. And this belief is what motivated his deep interest in America, for his visit convinced him that America had achieved in a peaceful and natural way almost complete “equality of conditions.” By understanding America, he thought that we could not only understand what democracy means, but in a way even glimpse the world’s future. “I confess,” he wrote, “that in America I saw more than America; I sought the image of democracy itself, with its inclinations, its character, its prejudices, and its passions, in order to learn what we have to fear or hope from its progress.” This feature examines Tocqueville’s argument that the “great democratic revolution” is inevitable and irresistible.

Part of A Long Tradition

Alexis de Tocqueville is part of a long tradition of well-educated Europeans who traveled to America and published books or diaries about their experiences in the “new” world. Unlike most of the others, however, the book Tocqueville wrote has proved over the years to be a lasting source of information and insight into both America and democracy. Democracy in America is now widely studied in America universities, and it has been quoted by Presidents, Supreme Court Justices, and Congressmen. Humbler instances of its influence abound; for example, the name for the most generous category of giver to The United Way is the “Alexis de Tocqueville Society”.

When Tocqueville visited America, Andrew Jackson was President. It was in this period that the United States first surpassed Europe in per capita income. It was also during Tocqueville’s visit that Black Hawk, the leader of the Sauk and Fox Indians, agreed to move across the Mississippi River to a reservation in Iowa, and that Nat Turner led an uprising of slaves in Virginia.

The current popularity of Democracy in America in the United States might have surprised Tocqueville himself, because he wrote the book primarily for a French audience. The first volume was published forty-six years after the French Revolution. That great upheaval had destroyed the “ancient regime” — the political order comprised of divine right monarchs, hereditary aristocrats, and peasants — but France had still not found political stability. As Tocqueville points out in the Introduction, many leading Frenchmen were unwilling to accept that equality had come to stay: looking to the past with regret some foolishly ignored the fundamental changes taking place around them; others found themselves caught in various unnatural and unhealthy moral and political confusions. It was first and foremost for such people that Tocqueville wrote the book. He hoped that by showing them in detail what democracy was they would be able better to guide France’s own transition to democracy. In so doing, however, he gave the world its richest, most various, and deepest reflection on democracy. But why was Tocqueville so certain that democracy was inevitable and irresistible? His argument for this opinion is the main theme of this book’s introduction.

Note on the text of Democracy in America . Several translations of Tocqueville’s text are available in English. The page numbers and quotations used in this feature refer to the translation done by Harvey C. Mansfield and Delba Winthrop (the University of Chicago Press, 2000). This is one of the most recent and highly regarded translations, but it is not available online. Therefore, for those who wish to use an online text, the links provided are to the 1899 revision of the Henry Reeve translation . The two translations differ in many ways, but it should not be difficult to find the parallel passages.

How to Teach Tocqueville’s Introduction

Use the following activities and worksheets to help students understand what specific developments and events in history contribute to the advancement of greater equality in society and which ones Tocqueville regarded as most important.

Suggested Homework Assignment

Have the students read pp. 3–7 and 12–15 of Democracy in America the night before the reading is discussed in class ( "Tocqueville Reading A” in the reading packet ). Each student should draw up a numbered list of the different things that Tocqueville says contribute to equality in society (Link to Equality Worksheet ). They should also define the following words: generative, clergy, Providence, enlightenment, feudal, haphazardly, arsenal (Link to Definitions Worksheet ). The class can have two, or if there is time, three parts. The most important part is the second activity below and the most time should be spent on it.

Activity 1. “Equality of Condition”

Have a student read out loud the first three paragraphs of the Introduction. Follow this with a brief discussion of this passage, beginning with the question, what is it about America that most impressed Tocqueville? This is of course something he calls the “equality of conditions.” Tocqueville does not say much about this here; he doesn’t even define it or tell us what it is. But he does describe in broad strokes how important it is, and the students should get some appreciation of this. Ask them what the equality of conditions is responsible for in America. Students should be able to say several things about this, but one thing they should notice is that it is not the same thing as democracy. According to Tocqueville, equality of conditions shapes laws and otherwise influences government, but it also “creates opinions” and “gives birth to sentiments” in society more broadly. It is the “primary fact” about America, the “generative fact” from which all other facts seem to issue, and the “central point” at which all of Tocqueville’s observations come to an end. Equality of conditions influences and may give rise to democracy, but it is something deeper and more powerful than any particular form of government

Activity 2. “A great democratic revolution is taking place among us”

Tocqueville then shifts his attention to France (and more generally, to Europe) and announces that “a great democratic revolution is taking place among us.” The problem is that there is an important division of opinion in France about what this revolution means. Is it something new and accidental that can be stopped, or is it something deep and old, indeed, “the most permanent fact known in history”? To answer this question, Tocqueville gives us a thumbnail sketch of French history over the past seven hundred years. The core of the lesson is what Tocqueville says in this history in the next two and a half pages . For most of this passage, each paragraph elaborates a different thing that has contributed to the advancement of equality. Have students read and discuss this passage. Students should understand how the thing Tocqueville is discussing (e.g., the development of a taste for literature, struggles between king and nobles, etc.) worked to promote equality. Students will have their lists to consult and the teacher may want to develop a running list on the blackboard or whiteboard.

Since Democracy in America was published in 1835, Tocqueville’s history begins in approximately 1100 CE. The first paragraph of the history gives a brief sketch of Europe at that time, before the great movement towards equality began. Because Tocqueville’s statement is very brief and mentions only the most essential points, help the students understand what he is saying. For example, Tocqueville says that a few families had a monopoly on political power. Moreover, their power is a certain kind, being tied to the possession of land (feudal estates) and passing from one person to another in the same family only by inheritance. These arrangements guarantee that only a very few people have a share of political power — the king and the nobles or aristocrats (warriors); all the rest are peasants or serfs working the land. There is absolutely no equality between a king and a noble, on the one hand, or between a noble and a serf, on the other.

In the paragraphs that follow, Tocqueville describes the important developments and events (usually one for each paragraph) that gradually undermined the feudal system and transformed Europe in the direction of social equality. After having a student read a paragraph, have the class discuss it, asking how the development or event fostered or encouraged equality. For example, the first step is the development of the “political power of the clergy”. Americans are so used to thinking that church and state should be separate, that we might wonder how it can be a good thing (i.e., how it can favor equality) for clergymen to have political power? Tocqueville suggests two answers. First, when the clergy got political power, it introduced into feudal Europe a new route to political power, a route based on the church rather than on inherited land. To put it bluntly, if you can get power through the church, you don’t need land. This did not make everyone in society equal, but it does mean that there were now more ways to get political power and that more people had access to political power than before; and anything that extends access to political power, favors equality. Second, because of the Christian idea that all men are equal before God, anyone — serf, peasant, or lord — could become a clergyman. In other words, inside the church there is a principle of equality, and when the clergy gained political power, this principle began (gradually) to influence politics.

Work through each of the paragraphs, discussing how each of the developments Tocqueville mentions favors equality and therefore democracy. Tocqueville lists four main developments, each of which established a new route to political power: the clergy, law and lawyers, money and trade, enlightenment or the taste for literature and the arts. Then in several paragraphs, he elaborates on various aspects of these four. Finally, he explains that almost all the major events in the past seven hundred years benefitted equality. There are many surprising things in Tocqueville’s brief history and students should begin to get a sense for his view that every development and major event in European history, promoted equality, including a great many that had no intention of so doing. Having worked through the passage, students should have a much better appreciation for the many social, economic, intellectual, and religious changes that help to support democracy because they help to maintain equality in society.

When the class has worked through these three pages, the teacher may want to look at the list and ask which one of the developments the students think was most important for promoting equality. There is no “right” answer to this question, but the paragraph on p. 5 that begins “Once works of the intellect had become sources of force and wealth” is very important ( “Tocqueville Reading B” in the reading packet ). This passage highlights how important the human mind is for democracy, for it points out that the great intellectual and creative talents of humanity are distributed seemingly at random, without any thought for rank or power or class. And it is precisely these talents that, according to Tocqueville, reveal “the natural greatness of man.” Moreover, their products, especially literature, are “an arsenal open to all, from which the weak and the poor came each day to seek arms.” It seems to be Tocqueville’s view that the development of the human mind fosters and goes naturally together with equality and democracy.

To examine in more detail Tocqueville’s description of equality in specifically American conditions, read Part One , chapters 1-3.

Activity 3. “Providential Fact” or “Force of Nature”?

By this point, it should be clear to the students that of the two opinions about the “great democratic revolution” summarized in the fifth paragraph of the Introduction, Tocqueville himself adheres to the second one, namely that it is “irresistible because ... it seems the most continuous, the oldest, and the most permanent fact known in history.” The lesson could end here, but if there is time and interest, the teacher may have a further discussion of how Tocqueville evaluates or judges the brute, if irresistible fact he has just described. What is his attitude towards it?

The crucial passages to answer this question appear on pages 6–7 (from the paragraph that begins “Everywhere the various incidents in the lives of people.” to the paragraph that ends “... takes us backward toward the abyss” ( “Tocqueville Reading C” in the reading packet ). Draw the attention of students to the many references or allusions to God, human power (the weakness of it), Providence, “religious terror,” “the usual course of nature,” and the Creator. What is revealed about Tocqueville’s view when he speaks about the movement towards equality in such highly charged theological language? Does this mean that equality and democracy are not just inevitable and irresistible, but also good? If that is what Tocqueville means, why does he regard this irresistible revolution with a “sort of religious terror”? Finally, ask students to reflect on the significance of the two images Tocqueville uses in this passage: the reference to the creation of the stars and to men floating backwards down a rapidly flowing river (both on p. 7).

Selected EDSITEment Websites

- Alexis de Tocqueville in France

- Democracy in America , American Studies, University of Virginia

- The Alexis De Tocqueville Tour: Exploring Democracy in Americ a

Materials & Media

Democracy in america: alexis de tocqueville's introduction: worksheet 1, democracy in america: alexis de tocqueville's introduction: worksheet 2, democracy in america: alexis de tocqueville's introduction: worksheet 3, related on edsitement, alexis de tocqueville on the tyranny of the majority, alexis de tocqueville’s warning: the tyranny of the majority, the constitutional convention of 1787, the federalist and anti-federalist debates on diversity and the extended republic.

Democracy in America: Critical Summary Essay

Introduction, critical summary of “democracy in america”, critical response, works cited.

The book, “ Democracy in America ” by Alexis de Tocqueville defines the thoughts of the author on various aspects of America from the angles of social, political, security, and the need for appreciation of diversity especially among the Anglo-Americans. Thus, this reflective treatise attempts to explicitly review various thoughts expressed in this book. Besides, the paper is specifically on the quantifiable elements as discusses and presents explanation at the macro level.

This literature is vital in understanding the history of America and how the political system operates on the facets of foreign policy evaluation and modifying democracy in order to maintain relevance in line with the American dream. As a matter of fact, the author discusses social problems, injustices, and discrimination in the face of the American democratic system.

Tocqueville (1862) states that “epochs sometimes occur in the life of a nation when the old customs of a person are changed, public morality is destroyed, religious belief shaken, and the spell of tradition broken” (Tocqueville 19). However, the same freedom liberates the Americans to choose religious inclination as long as the same does not infringe the right of other from the historical perspective of America resonates on the ideology of ultimate triumph from involuntary slavery and exploitation.

The book reviews the beginning of America and its endeavors towards natural morality. The author identifies statesmen who would do everything to defend what they believed in as the infact America experienced metamorphosis. For instance, defense of morality and the rule of law in the society of America has been the main issue proposed by the author since the rule of law defines the moral standards captured in the constitution on personal orientation.

The author claims that in America, “a stranger may be well inclined to praise many of the institutions of their country, but he begs permission to blame some things in it, a permission that is inexorably refused” (Tocqueville 17). This aspect is key towards reviewing the main institutional structures that facilitate coexistence among the Anglo-Americans in terms of social and moral values.

The book identifies social change as defining democracy and the practical aspects of the same. According to the author, Democratization of a political system reveals the level of maturity of a nation. The timid souls are identified by the author as the very people who believe in the status quo and resistance to change at all levels unlike the new society of America which is ready to make sacrifices when there is an urgent need for the same.

Argument construction is a systematic and dynamic process. The main objective, sub objective, and environment influence its process of dissemination. Specifically, chapter three to five states that the process of democracy evaluation is as a result of the perception of the ideal learning logic and prior experience as guided by planning rubric.

The book opines that having a well prepared democratization plan will ensure that a person is adequately prepared with all the materials that are needed to deliver a properly constructed and easy to interpret social systems.

Since the ability to create distinct emotions in an argument is essential in the final persuasiveness, the author’s concluding that democracy is a continuous process that climax upon understanding the underlying premises. As a result, the reader is placed in an effective and flexible environment that creates room for objective reflection and proactive thinking in terms of the history of America.

Tocqueville, Alexis. Democracy in America, New York: Longman, 1862. Print.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, November 24). Democracy in America: Critical Summary. https://ivypanda.com/essays/democracy-in-america-critical-summary/

"Democracy in America: Critical Summary." IvyPanda , 24 Nov. 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/democracy-in-america-critical-summary/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Democracy in America: Critical Summary'. 24 November.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Democracy in America: Critical Summary." November 24, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/democracy-in-america-critical-summary/.

1. IvyPanda . "Democracy in America: Critical Summary." November 24, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/democracy-in-america-critical-summary/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Democracy in America: Critical Summary." November 24, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/democracy-in-america-critical-summary/.

- "The Old Regime and the French Revolution" by Alexis De Tocqueville

- Durkheim and Tocqueville on Groups in Society

- Alexis de Tocqueville: Three Races in the U.S.

- Skilled Labor and Alexis de Tocqueville's Views

- Anglo-American Western Expansion

- Ideas of Tyranny in 1776 and 1830

- Borderland and Its Features in the United States

- The History of the Mexican–American War

- Settling in the United States

- The History of Propaganda: From the Ancient Times to Nowadays

- Why would they act the way they act?

- Sigmund Freud's "The Uncanny"

- "A Ghetto Takes Shape" by Kenneth Kusmer

- Significance of a Male Role Model for Forming Tomas and Gabe’s Personal

- Critical Analysis of "Uncle Tom’s Cabin"

Home — Essay Samples — Government & Politics — Political Systems & Ideologies — Democracy in America

Essays on Democracy in America

Democracy in united states, how democratic is the constitution and is there a need for the removal of the electoral college, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Democracy as One of The Staple and Founding Features of The United States

An evolution of american democracy, role and impact of the pressure groups, tocqueville - the persistence of a democratic republic, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Significance of Democracy in The United States

A corruptive factor in american politics, trump and democracy, the federalist no. 51 and its significance in political thought, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

Essay on Democracy in 100, 300 and 500 Words

- Updated on

- Jan 15, 2024

The oldest account of democracy can be traced back to 508–507 BCC Athens . Today there are over 50 different types of democracy across the world. But, what is the ideal form of democracy? Why is democracy considered the epitome of freedom and rights around the globe? Let’s explore what self-governance is and how you can write a creative and informative essay on democracy and its significance.

Today, India is the largest democracy with a population of 1.41 billion and counting. Everyone in India above the age of 18 is given the right to vote and elect their representative. Isn’t it beautiful, when people are given the option to vote for their leader, one that understands their problems and promises to end their miseries? This is just one feature of democracy , for we have a lot of samples for you in the essay on democracy. Stay tuned!

Can you answer these questions in under 5 minutes? Take the Ultimate GK Quiz to find out!

This Blog Includes:

What is democracy , sample essay on democracy (100 words), sample essay on democracy (250 to 300 words), sample essay on democracy for upsc (500 words).

Democracy is a form of government in which the final authority to deliberate and decide the legislation for the country lies with the people, either directly or through representatives. Within a democracy, the method of decision-making, and the demarcation of citizens vary among countries. However, some fundamental principles of democracy include the rule of law, inclusivity, political deliberations, voting via elections , etc.

Did you know: On 15th August 1947, India became the world’s largest democracy after adopting the Indian Constitution and granting fundamental rights to its citizens?

Must Explore: Human Rights Courses for Students

Must Explore: NCERT Notes on Separation of Powers in a Democracy

Democracy where people make decisions for the country is the only known form of governance in the world that promises to inculcate principles of equality, liberty and justice. The deliberations and negotiations to form policies and make decisions for the country are the basis on which the government works, with supreme power to people to choose their representatives, delegate the country’s matters and express their dissent. The democratic system is usually of two types, the presidential system, and the parliamentary system. In India, the three pillars of democracy, namely legislature, executive and judiciary, working independently and still interconnected, along with a free press and media provide a structure for a truly functional democracy. Despite the longest-written constitution incorporating values of sovereignty, socialism, secularism etc. India, like other countries, still faces challenges like corruption, bigotry, and oppression of certain communities and thus, struggles to stay true to its democratic ideals.

Did you know: Some of the richest countries in the world are democracies?

Must Read : Consumer Rights in India

Must Read: Democracy and Diversity Class 10

As Abraham Lincoln once said, “democracy is the government of the people, by the people and for the people.” There is undeniably no doubt that the core of democracies lies in making people the ultimate decision-makers. With time, the simple definition of democracy has evolved to include other principles like equality, political accountability, rights of the citizens and to an extent, values of liberty and justice. Across the globe, representative democracies are widely prevalent, however, there is a major variation in how democracies are practised. The major two types of representative democracy are presidential and parliamentary forms of democracy. Moreover, not all those who present themselves as a democratic republic follow its values.

Many countries have legally deprived some communities of living with dignity and protecting their liberty, or are practising authoritarian rule through majoritarianism or populist leaders. Despite this, one of the things that are central and basic to all is the practice of elections and voting. However, even in such a case, the principles of universal adult franchise and the practice of free and fair elections are theoretically essential but very limited in practice, for a democracy. Unlike several other nations, India is still, at least constitutionally and principally, a practitioner of an ideal democracy.

With our three organs of the government, namely legislative, executive and judiciary, the constitutional rights to citizens, a multiparty system, laws to curb discrimination and spread the virtues of equality, protection to minorities, and a space for people to discuss, debate and dissent, India has shown a commitment towards democratic values. In recent times, with challenges to freedom of speech, rights of minority groups and a conundrum between the protection of diversity and unification of the country, the debate about the preservation of democracy has become vital to public discussion.

Did you know: In countries like Brazil, Scotland, Switzerland, Argentina, and Austria the minimum voting age is 16 years?

Also Read: Difference Between Democracy and Dictatorship

Democracy originated from the Greek word dēmokratiā , with dēmos ‘people’ and Kratos ‘rule.’ For the first time, the term appeared in the 5th century BC to denote the political systems then existing in Greek city-states, notably Classical Athens, to mean “rule of the people.” It now refers to a form of governance where the people have the right to participate in the decision-making of the country. Majorly, it is either a direct democracy where citizens deliberate and make legislation while in a representative democracy, they choose government officials on their behalf, like in a parliamentary or presidential democracy.

The presidential system (like in the USA) has the President as the head of the country and the government, while the parliamentary system (like in the UK and India) has both a Prime Minister who derives its legitimacy from a parliament and even a nominal head like a monarch or a President.

The notions and principle frameworks of democracy have evolved with time. At the core, lies the idea of political discussions and negotiations. In contrast to its alternatives like monarchy, anarchy, oligarchy etc., it is the one with the most liberty to incorporate diversity. The ideas of equality, political representation to all, active public participation, the inclusion of dissent, and most importantly, the authority to the law by all make it an attractive option for citizens to prefer, and countries to follow.

The largest democracy in the world, India with the lengthiest constitution has tried and to an extent, successfully achieved incorporating the framework to be a functional democracy. It is a parliamentary democratic republic where the President is head of the state and the Prime minister is head of the government. It works on the functioning of three bodies, namely legislative, executive, and judiciary. By including the principles of a sovereign, socialist, secular and democratic republic, and undertaking the guidelines to establish equality, liberty and justice, in the preamble itself, India shows true dedication to achieving the ideal.

It has formed a structure that allows people to enjoy their rights, fight against discrimination or any other form of suppression, and protect their rights as well. The ban on all and any form of discrimination, an independent judiciary, governmental accountability to its citizens, freedom of media and press, and secular values are some common values shared by all types of democracies.

Across the world, countries have tried rooting their constitution with the principles of democracy. However, the reality is different. Even though elections are conducted everywhere, mostly, they lack freedom of choice and fairness. Even in the world’s greatest democracies, there are challenges like political instability, suppression of dissent, corruption , and power dynamics polluting the political sphere and making it unjust for the citizens. Despite the consensus on democracy as the best form of government, the journey to achieve true democracy is both painstaking and tiresome.

Did you know: Countries like Singapore, Peru, and Brazil have compulsory voting?

Must Read: Democracy and Diversity Class 10 Notes

Democracy is a process through which the government of a country is elected by and for the people.

Yes, India is a democratic country and also holds the title of the world’s largest democracy.

Direct and Representative Democracy are the two major types of Democracy.

Related Articles

Hope you learned from our essay on democracy! For more exciting articles related to writing and education, follow Leverage Edu .

Sonal is a creative, enthusiastic writer and editor who has worked extensively for the Study Abroad domain. She splits her time between shooting fun insta reels and learning new tools for content marketing. If she is missing from her desk, you can find her with a group of people cracking silly jokes or petting neighbourhood dogs.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Very helpful essay

Thanks for your valuable feedback

Thank you so much for informing this much about democracy

Leaving already?

8 Universities with higher ROI than IITs and IIMs

Grab this one-time opportunity to download this ebook

Connect With Us

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

September 2024

January 2025

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Democracy in America

Alexis de toqueville, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

Alexis de Tocqueville begins Democracy in America by discussing present-day conditions in his own nation, France. Although France—and Europe in general—have long been home to aristocratic monarchies (where a king and queen rule but an aristocratic class also retains power and privileges based on birth), equality of condition (a leveling out of social class hierarchies) is increasingly coming to replace such customs. Tocqueville describes a number of broad historical reasons for these changes, and then admits that he himself is terrified of this democratizing process. However, given that it’s impossible to halt the forces of democratization, he suggests that it would be useful to consider the example of American democracy, where equality of condition has developed further than anywhere else.

Tocqueville first describes the basis of American society by giving a historical account of the Pilgrims who first arrived from England, and the ways in which sovereignty of the people was established quite early on, most notably through the dissemination of power into various townships . He maintains that this helps to mitigate the dangers of highly centralized administration, which can numb or “enervate” nations. Tocqueville elaborates a number of features of America’s federalist system, which divides power between the national capital, the states, and local townships, stressing the ways this system both maintains individual freedom and encourages people to play an active role in their nation’s political affairs. Democratic juries are a key example of active political life in America.

After discussing some of the advantages and disadvantages of great size, Tocqueville discusses the ways America has avoided the dangers of large kingdoms. He returns to a discussion of early American history and the arguments about how to divide power, resulting in the current division of political parties. Tocqueville also draws attention to the power of the press in America, which he praises as a civic institution that promotes liberty and disseminates political knowledge. Political associations are another means by which Americans maintain individual political rights. Indeed, Tocqueville insists on political rights and education as essential to promoting freedom, and he argues that Americans have by and large succeeded in promoting such rights—even if he also draws attention to certain excesses of Americans’ intense political involvement.

Tocqueville subsequently turns to what he considers a crucial aspect of American society: the sovereignty of the majority, which, he warns, can become just as tyrannical as an individual despot. He worries that it’s the very strength of democratic institutions in America that may one day lead to the country’s downfall—arguing against a number of his contemporaries who fear that democracy’s weakness might lead to anarchy and disorder. However, Tocqueville also argues that America has found a number of ways to mitigate tyranny of the majority, especially through law and the jury system, political associations, and the historical effects of Puritanism in early America. He concludes Part One by acknowledging that he doesn’t think France or other countries should copy the American system; still, he argues, American democracy has proved remarkably versatile and powerful.

In Part Two, Tocqueville pays far more attention to non- or extra-political aspects of American culture, expressing more reservations about American democracy and its effect on social life than he had in Part One. He insists that Americans have little concern for philosophy or abstract ideas, preferring simplicity and directness. This is in part why religion can be so useful in a democracy, since it is a clear (though limited) source of authority that also mitigates some of the materialism and selfishness that Tocqueville finds prevalent in democratic societies.

Tocqueville argues that America hasn’t made much progress in science, poetry, or the arts, and he attempts to find political reasons for this weakness. Democratic equality has the unfortunate consequence of making people pursue material desires and economic improvement above all else, he thinks, leaving them little time or interest for more abstract, intellectual affairs. Still, the ability of more and more people to leave desperate poverty behind will only increase the number of those involved in scientific pursuits, even if the quality of such pursuits is lower than in an aristocracy. Tocqueville continues to insist on Americans’ preference for the concrete over the abstract, the practical over the theoretical, and the useful over the beautiful. As a result, America and other democracies will tend to produce more and cheaper commodities rather than fewer, more well-wrought objects. Tocqueville uses similar reasoning to explain what he argues is America’s lack of its own literature. Americans’ lives are unpoetic, he thinks. But he also tries to imagine what poetry will look like in the future, hypothesizing that democratic poetry will increasingly study human nature and try to account for all of human existence.

Tocqueville subsequently returns to his earlier argument that freedom and equality do not necessarily go together—and that, indeed, democracies will always privilege the latter over the former. America’s individualism both results from equality and works to maintain it, he thinks, even while causing bonds between people to erode and threatening the ability of society to function well. This lack of fellow-feeling is what makes democracies particularly prone to despotism, he thinks, even as the political and civic associations that are so prevalent in America have worked against such a threat. Indeed, Tocqueville turns his attention to the various civic institutions, such as town halls and temperance societies, which bind citizens together and work against individualism and materialism.

Tocqueville turns to another aspect of American culture, the intense physical vigor that seems to characterize Americans; he argues that this stems from their embrace of constant activity and striving to improve their material conditions. This is also why industry and commerce are prized above all in America, he thinks, because Americans are eager to become wealthy (and enjoy far more upward mobility than in an aristocracy); however, he warns that the consolidation of wealth among a manufacturing class threatens to erode such social mobility. Tocqueville also discusses Americans’ casual manners and disdain for etiquette, which he contrasts to European attitudes, while also depicting Americans as vain and proud.

Tocqueville then spends some time discussing the institution of the family in America, where the relationship between fathers and sons is characterized by a greater ease than in Europe—there, a sense of patriarchal authority leads to stiff, artificial family relations. Tocqueville also praises the place of women in America, who are given far more independence and respect than they are in Europe. He admires their relatively higher level of education and argues that education should be extended to women as part of extending political rights to everyone. He finds that women play a central role in the success of American democracy—even though he also argues that this participation is predicated on their confinement to the domestic sphere. Indeed, Tocqueville thinks that America has accepted the “natural” differences between men and women and, therefore, that there is actually greater equality between the sexes in the United States.

Tocqueville goes on to describe other characteristics of American manners, from homogeneity of behavior to Americans’ vanity to the monotony of daily life that exists when people’s conditions are more and more the same—Tocqueville fears the “enervating” effects of such homogeneous behaviors, attitudes, and ways of life. He characterizes Americans as ambitious, even as their ambitions have an upper limit: Americans prefer stability and peace above all else, making them unlikely to want to seize power or go to war. Europe is far more revolutionary than America precisely because democracy has not yet secured a place for itself there. Indeed, Tocqueville insists on the relationship between democracy and peace, even as he acknowledges some of the peculiarities of democratic armies, whose soldiers are unique in democratic societies because they are eager for war.

Tocqueville returns to his concern that democracies will continue to prefer increasingly centralized power, in part because of their preference for peace and stability. America has managed to avoid such dangers thus far because its citizens have had a long time to accustom themselves both to individual liberties and to participation in politics on a number of levels. Still, the centralization of power remains a major danger in a democracy. At the same time, though, perhaps the greatest threat to a democracy is the despotism of the majority. Tocqueville depicts a number of hypothetical scenarios of future democratic societies where everyone thinks and acts the same way, where tyranny is diffused in a subtle, insidious, but no less powerful way. As he concludes, he acknowledges that it’s difficult, if not impossible, to predict the future; he is saddened by the homogenization and increased uniformity of ways of life that he sees, even as he admits that this may be an unavoidable consequence of extending greater equality to all. In any case, he argues that it’s impossible and undesirable to turn back the clock—even as he ends by insisting that people have the power to change their historical conditions, working within the vast processes of democratization in order to maintain and extend individual liberties.

- Kindle Store

- Kindle eBooks

Promotions apply when you purchase

These promotions will be applied to this item:

Some promotions may be combined; others are not eligible to be combined with other offers. For details, please see the Terms & Conditions associated with these promotions.

- Highlight, take notes, and search in the book

- In this edition, page numbers are just like the physical edition

Buy for others

Buying and sending ebooks to others.

- Select quantity

- Buy and send eBooks

- Recipients can read on any device

These ebooks can only be redeemed by recipients in the US. Redemption links and eBooks cannot be resold.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Democracy in America: And Two Essays on America (Penguin Classics) New Ed Edition, Kindle Edition

One of the most influential political texts ever written on America, and an indispensable authority on the nature of democracy In 1831 Alexis de Tocqueville, a young French aristocrat and civil servant, made a nine-month journey through eastern America. The result was Democracy in America , a monumental study of the strengths and weaknesses of the nation's evolving politics. Tocqueville looked to the flourishing democratic system in America as a possible model for post-revolutionary France, believing its egalitarian ideals reflected the spirit of the age. This edition, the only one that contains all Tocqueville's writings on America, includes the rarely translated 'Two Weeks in the Wilderness', an evocative account of Tocqueville's travels among the Iroquois and Chippeway, and 'Excursion to Lake Oneida'. Translated by Gerald Bevan with an Introduction and Notes by Isaac Kramnick

- ISBN-13 978-0140447606

- Edition New Ed

- Sticky notes On Kindle Scribe

- Publisher Penguin

- Publication date April 24, 2003

- Language English

- File size 1706 KB

- See all details

- Kindle (5th Generation)

- Kindle Keyboard

- Kindle (2nd Generation)

- Kindle (1st Generation)

- Kindle Paperwhite

- Kindle Paperwhite (5th Generation)

- Kindle Touch

- Kindle Voyage

- Kindle Oasis

- Kindle Scribe (1st Generation)

- Kindle Fire HDX 8.9''

- Kindle Fire HDX

- Kindle Fire HD (3rd Generation)

- Fire HDX 8.9 Tablet

- Fire HD 7 Tablet

- Fire HD 6 Tablet

- Kindle Fire HD 8.9"

- Kindle Fire HD(1st Generation)

- Kindle Fire(2nd Generation)

- Kindle Fire(1st Generation)

- Kindle for Windows 8

- Kindle for Windows Phone

- Kindle for BlackBerry

- Kindle for Android Phones

- Kindle for Android Tablets

- Kindle for iPhone

- Kindle for iPod Touch

- Kindle for iPad

- Kindle for Mac

- Kindle for PC

- Kindle Cloud Reader