What to know about the crisis of violence, politics and hunger engulfing Haiti

A long-simmering crisis over Haiti’s ability to govern itself, particularly after a series of natural disasters and an increasingly dire humanitarian emergency, has come to a head in the Caribbean nation, as its de facto president remains stranded in Puerto Rico and its people starve and live in fear of rampant violence.

The chaos engulfing the country has been bubbling for more than a year, only for it to spill over on the global stage on Monday night, as Haiti’s unpopular prime minister, Ariel Henry, agreed to resign once a transitional government is brokered by other Caribbean nations and parties, including the U.S.

But the very idea of a transitional government brokered not by Haitians but by outsiders is one of the main reasons Haiti, a nation of 11 million, is on the brink, according to humanitarian workers and residents who have called for Haitian-led solutions.

“What we’re seeing in Haiti has been building since the 2010 earthquake,” said Greg Beckett, an associate professor of anthropology at Western University in Canada.

What is happening in Haiti and why?

In the power vacuum that followed the assassination of democratically elected President Jovenel Moïse in 2021, Henry, who was prime minister under Moïse, assumed power, with the support of several nations, including the U.S.

When Haiti failed to hold elections multiple times — Henry said it was due to logistical problems or violence — protests rang out against him. By the time Henry announced last year that elections would be postponed again, to 2025, armed groups that were already active in Port-au-Prince, the capital, dialed up the violence.

Even before Moïse’s assassination, these militias and armed groups existed alongside politicians who used them to do their bidding, including everything from intimidating the opposition to collecting votes . With the dwindling of the country’s elected officials, though, many of these rebel forces have engaged in excessively violent acts, and have taken control of at least 80% of the capital, according to a United Nations estimate.

Those groups, which include paramilitary and former police officers who pose as community leaders, have been responsible for the increase in killings, kidnappings and rapes since Moïse’s death, according to the Uppsala Conflict Data Program at Uppsala University in Sweden. According to a report from the U.N . released in January, more than 8,400 people were killed, injured or kidnapped in 2023, an increase of 122% increase from 2022.

“January and February have been the most violent months in the recent crisis, with thousands of people killed, or injured, or raped,” Beckett said.

Armed groups who had been calling for Henry’s resignation have already attacked airports, police stations, sea ports, the Central Bank and the country’s national soccer stadium. The situation reached critical mass earlier this month when the country’s two main prisons were raided , leading to the escape of about 4,000 prisoners. The beleaguered government called a 72-hour state of emergency, including a night-time curfew — but its authority had evaporated by then.

Aside from human-made catastrophes, Haiti still has not fully recovered from the devastating earthquake in 2010 that killed about 220,000 people and left 1.5 million homeless, many of them living in poorly built and exposed housing. More earthquakes, hurricanes and floods have followed, exacerbating efforts to rebuild infrastructure and a sense of national unity.

Since the earthquake, “there have been groups in Haiti trying to control that reconstruction process and the funding, the billions of dollars coming into the country to rebuild it,” said Beckett, who specializes in the Caribbean, particularly Haiti.

Beckett said that control initially came from politicians and subsequently from armed groups supported by those politicians. Political “parties that controlled the government used the government for corruption to steal that money. We’re seeing the fallout from that.”

Many armed groups have formed in recent years claiming to be community groups carrying out essential work in underprivileged neighborhoods, but they have instead been accused of violence, even murder . One of the two main groups, G-9, is led by a former elite police officer, Jimmy Chérizier — also known as “Barbecue” — who has become the public face of the unrest and claimed credit for various attacks on public institutions. He has openly called for Henry to step down and called his campaign an “armed revolution.”

But caught in the crossfire are the residents of Haiti. In just one week, 15,000 people have been displaced from Port-au-Prince, according to a U.N. estimate. But people have been trying to flee the capital for well over a year, with one woman telling NBC News that she is currently hiding in a church with her three children and another family with eight children. The U.N. said about 160,000 people have left Port-au-Prince because of the swell of violence in the last several months.

Deep poverty and famine are also a serious danger. Gangs have cut off access to the country’s largest port, Autorité Portuaire Nationale, and food could soon become scarce.

Haiti's uncertain future

A new transitional government may dismay the Haitians and their supporters who call for Haitian-led solutions to the crisis.

But the creation of such a government would come after years of democratic disruption and the crumbling of Haiti’s political leadership. The country hasn’t held an election in eight years.

Haitian advocates and scholars like Jemima Pierre, a professor at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, say foreign intervention, including from the U.S., is partially to blame for Haiti’s turmoil. The U.S. has routinely sent thousands of troops to Haiti , intervened in its government and supported unpopular leaders like Henry.

“What you have over the last 20 years is the consistent dismantling of the Haitian state,” Pierre said. “What intervention means for Haiti, what it has always meant, is death and destruction.”

In fact, the country’s situation was so dire that Henry was forced to travel abroad in the hope of securing a U.N. peacekeeping deal. He went to Kenya, which agreed to send 1,000 troops to coordinate an East African and U.N.-backed alliance to help restore order in Haiti, but the plan is now on hold . Kenya agreed last October to send a U.N.-sanctioned security force to Haiti, but Kenya’s courts decided it was unconstitutional. The result has been Haiti fending for itself.

“A force like Kenya, they don’t speak Kreyòl, they don’t speak French,” Pierre said. “The Kenyan police are known for human rights abuses . So what does it tell us as Haitians that the only thing that you see that we deserve are not schools, not reparations for the cholera the U.N. brought , but more military with the mandate to use all kinds of force on our population? That is unacceptable.”

Henry was forced to announce his planned resignation from Puerto Rico, as threats of violence — and armed groups taking over the airports — have prevented him from returning to his country.

Now that Henry is to stand down, it is far from clear what the armed groups will do or demand next, aside from the right to govern.

“It’s the Haitian people who know what they’re going through. It’s the Haitian people who are going to take destiny into their own hands. Haitian people will choose who will govern them,” Chérizier said recently, according to The Associated Press .

Haitians and their supporters have put forth their own solutions over the years, holding that foreign intervention routinely ignores the voices and desires of Haitians.

In 2021, both Haitian and non-Haitian church leaders, women’s rights groups, lawyers, humanitarian workers, the Voodoo Sector and more created the Commission to Search for a Haitian Solution to the Crisis . The commission has proposed the “ Montana Accord ,” outlining a two-year interim government with oversight committees tasked with restoring order, eradicating corruption and establishing fair elections.

For more from NBC BLK, sign up for our weekly newsletter .

CORRECTION (March 15, 2024, 9:58 a.m. ET): An earlier version of this article misstated which university Jemima Pierre is affiliated with. She is a professor at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, not the University of California, Los Angeles, (or Columbia University, as an earlier correction misstated).

Patrick Smith is a London-based editor and reporter for NBC News Digital.

Char Adams is a reporter for NBC BLK who writes about race.

- Join our team

- The UOC in Latin America

Presentation

- Academic programme

Academic team

Career opportunities.

- Access requirements

Enrolment and fees

Online specialization diploma in crisis management and strategic planning (uoc, unitar).

The Postgraduate Diploma in Crisis Management and Strategic Planning is a unique opportunity designed to increase understanding of conflicts in all their dimensions and explore innovative approaches to their management, resolution and transformation, with the help of world-leading academics and experts. Built with the combined expertise of the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC) and the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR), it aims to equip participants with a broad set of skills, first-hand knowledge and unique expertise from the field. . The postgraduate course in Crisis Management and Strategic Planning (see more information below) is suitable for professionals working in conflict zones, within the framework of regional, governmental and non-governmental organizations, also for graduate students, young researchers or other academics who are interested in increasing your knowledge of conflicts and gaining skills in how to best resolve them. By choosing the...

The Postgraduate Diploma in Crisis Management and Strategic Planning is a unique opportunity designed to increase understanding of conflicts in all their dimensions and explore innovative approaches to their management, resolution and transformation, with the help of world-leading academics and experts. Built with the combined expertise of the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC) and the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR), it aims to equip participants with a broad set of skills, first-hand knowledge and unique expertise from the field. . The postgraduate course in Crisis Management and Strategic Planning (see more information below) is suitable for professionals working in conflict zones, within the framework of regional, governmental and non-governmental organizations, also for graduate students, young researchers or other academics who are interested in increasing your knowledge of conflicts and gaining skills in how to best resolve them. By choosing the postgraduate degree in Crisis Management and Strategic Planning, students gain access to a wide community of graduates (alumni) around the world. Becoming a part of this community will be a valuable asset for a lifetime. For more information you can consult the program file in English.

Boost your career

You can split your payment into instalments

- Conflict Analysis

- Conflict Resolution

- Introduction to PO and History of UN PO

- Mandate Evaluation, Leadership and Strategic Planning

- Interncultural/Ethnic Conflict and the management of diversity

- Game Theory

- Crisis Management

- Gender Matters

- Research Methods

Complete academic program

16 Oct 2024

Early enrolment

Credits ECTS

Languages: English

At the UOC, an ECTS credit is equivalent to 25 hours of student work.

Depending on the number of ECTS credits, the duration of lifelong learning programs ranges from 1 month to 2 years, approximately:

- Lifelong learning master's degree: 2 years

- Specialization diploma: 1 year

- Expert diploma: 1 semester (6 months)

- Postgraduate course: between 1 and 6 months

Fully online method

World's first ever online university

Personalized guidance and support

1st Spanish-language online MBA in the world

Together with:

The university that won the race against time

The virtual classroom

- Learning resources

- Academic pathway

Postgraduate in Crisis Management and Strategic Planning

At the UOC, an ECTS credit is equivalent to 25 hours of student work. Depending on the number of ECTS credits, the duration of lifelong learning programs ranges from 1 month to 2 years, approximately:

- Postgraduate course: between 1 and 6 months

The Specialization Diploma in Crisis Management and Strategic Planning (UOC, UNITAR) is part of the following academic pathway:

- Specialization Diploma: Armed Conflicts (UOC, UNITAR)

- Specialization Diploma: Crisis Management and Strategic Planning (UOC, UNITAR)

The specialization is a course within the Master's Degree in Conflict, Peace and Security. Students can go on to study either this master's degree or one of the following postgraduate courses: Armed Conflict, or Crisis Management and Strategic Management.

Dean management

Direction programme.

Celina del Felice

Donato kiniger passigli, francisco josé ruiz gonzález, grazvydas jasutis, johanna wolf de tafur, lucía morales aparicio, may tony akl, nicolai due-gundersen.

- Competencies

- Who is it addressed to?

- Professional outing

- to know the theory, its different approaches and the nature of contemporary conflicts

- to acquire skills of analysis and the ability to plan actions for peaceful interventions, both for the prevention of conflicts and for intervening during their development

- to learn techniques and strategies for intelligent non-violent intervention in conflict situations

- to access information and knowledge to be able to develop efficient intervention programmes and manage the quest for positive specific solutions

- to be able to lead and facilitate negotiation and mediation processes

- to transform the way to communicate both to prevent and to end conflicts

Employability

The employability of UOC students is key to the university's success. We identify and include in our programmes of study key competencies that are in demand in the job market. And our career guidance services empower you to make decisions and take action for your future occupation.

Student profile

- Any person with responsibilities and interests in solving conflicts

- Consultants, executives, leaders, lawyers of any industry

- Civil servants and managers of private and public organisations

- Directors and staff of NGOs, companies and other organisations working in conflict areas, in reconstruction, development and international cooperation

- Politicians and trade unionists

- Members of the armed forces and the police.

More than25 years' experience in e-learning

In 1995 the UOC was launched as the world's first fully online university . More than 25 years later, we are still pioneers in digital education.

Our eLearning Innovation Center oversees the evolution of our educational model, to ensure unique, high-quality, connected and networked learning experiences.

Times Higher Education

According to the Young University Rankings, published by Times Higher Education, we are fourth best in Spain.

Shanghai Ranking

We are among the world's top 150 universities for communication and the top 200 for education.

U-Multirank

Excellent ratings in knowledge transfer, regional engagement, and teaching and learning.

- Prior Knowledge

To be admitted to the programme, you must have a university degree or two years’ work experience and/or professional experience in the following fields:

- Legal Practice and Representation

- Humanitarian Action

- Political Science

- Cities and Urbanism

- International Cooperation

- International Conflict

- Criminology

- Human Rights and Democracy

- Public Administration and Management

- International Relations

Experience in a field other than those mentioned above will be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

Fluent English is essential for this programme because English is the language of instruction.

The UOC lifelong learning offers you programs aimed at acquiring the knowledge required for the most valued professional profiles.

Prior knowledge

The course material will be in English and the language used in class will also be English. Therefore, a command of English is required to follow this programme.

Depending on the lifelong learning programme in question, students who complete their studies will be awarded a lifelong learning master's degree, a specialization diploma or an expert diploma.

Students who pass other continuing education courses will be awarded the corresponding certificate.

- Enrolment process and price

- Payment options

Free enrolment insurance

Enrolment process.

This is the enrolment process that you have to follow if you want to start studying at the UOC for the first time. If you have already studied with us and want to continue, you should go to Virtual Campus Procedures.

Enrolment form

Fill in the enrolment form that you will find on all the pages of the program. After registering your personal data, you will be provided with a username and you will choose your password to access the campus. Then you will access the economic data section, where you will choose the payment method and you can request an invoice, if you need it.

You will receive two messages

Once you have enrolled, you will receive two messages to the mailbox that you have indicated. A first message is the confirmation of the formalization of your registration. In a second message, we will remind you of the username and password you have chosen, which will allow you to access the virtual campus.

Once you have completed your enrolment there is a fourteen day period within which you may exercise your right to withdraw your enrolment .

How do you enrol?

There are two moments a year for enrolment in Postgraduate Training, depending on when the program in question begins to teach. Check the registration period and the beginning of the course on the page of the studies you want to study.

Enrolment from May onwards

for programmes starting in September or October

Enrolment from November onwards

for programmes starting in February or March

Early enrolment discounts

Payment in instalments

Grants, aid and discounts

Special conditions for companies

Support for elite athletes

104.500 graduates

90 % of students study and work at the same time

84 % would choose the UOC again

Payment options for residents in Spain

For new students , the first installment will be 10% of the amount.

Master : The first installment will be paid with POS, at the time of enrollment, and the rest in a maximum of 19 monthly installments starting from the month of beginning of teaching, by direct debit.

In case of enrolling a master's degree with an amount higher than 5,000 euros, the first installment will be paid by direct debit.

Postgraduate : The first installment will be paid with POS, at the time of enrollment, and the rest in a maximum of 7 monthly installments starting from the month of beginning of teaching, by direct debit.

Specialization and course : for amounts over 300 euros the first installment will be paid with POS, at the time of enrollment, and the rest in a maximum of 3 instalments by direct debit.

Payment in instalments carries a cost of 31 euros per procedure.

One-off payment

Payment of the enrolment fee is made once only by direct debit. When choosing this payment option, you will have to enter your bank details on the enrolment form. The charge for the enrolment fee will be made the following month.

In the case of specialization courses, one-off payment is made by POS terminal.

Payment options for master's degree, postgraduate studies and specializations

Consult the financing terms and conditions:

- Préstamo Aplazo (Deferred loan) Santander

Payment options for residents outside Spain

Master's degree courses : The payment option for payment in instalments of the enrolment fee is direct debit (if you have a SEPA account) or card direct debit (if you do not have a SEPA account). The first installment will be paid at the time of enrollment, and the rest in a maximum of 19 monthly installments starting from the month of beginning of teaching.

Postgraduate courses : The payment option for payment in instalments of the enrolment fee is direct debit (if you have a SEPA account) or card direct debit (if you do not have a SEPA account). The first installment will be paid at the time of enrollment, and the rest in a maximum of 7 monthly installments starting from the month of beginning of teaching.

Specialization and course : for amounts over 300 euros the first installment of the payment must be made by POS terminal at the time of enrollment, and the rest in a maximum of 3 installments by direct debit (if you have a SEPA account) or card direct debit (if you do not have a SEPA account).

Check here if your bank has a SEPA account.

Payment of the enrolment fee is made once only by card direct debit or bank transfer.

If you choose card direct debit, you will have to give the details of the card to be charged during the enrolment process. Remember that the cards we accept are VISA, Visa Electron and MasterCard (you cannot pay with American Express or Diner's Club).

The charge for the course enrolment fee will be made the following month. If you choose to pay for your course by card, remember that the terms and conditions to which you have agreed with your bank will apply. It is important that the card limit is higher than the cost of enrolment to prevent bills from being rejected.

If you have a SEPA bank account, payment can be made by direct debit. To choose this payment option, you will have to enter your bank details on the enrolment form. The charge for the course enrolment fee will be made the following month.

If you choose to pay by bank transfer, a scanned copy of the counterfoil must be sent via the Campus section: Secretary's Office / Enrolment / Payment options. The deadline for payment is ten days after the formalization date and always before the start of teaching.

You can arrange the transfer with the details shown on the enrolment sheet.

Banco Santander Central Hispano Passeig de Gràcia, 5. 08007 Barcelona. Spain Account number: 0049-1806-91-2111869374 Swift Code: BSCH ES MM IBAN: ES15-0049-1806-9121-1186-9374

Payment options for companies

Companies may only make payments by bank transfer. They cannot make payment in instalments.

During the enrolment process, you can choose the form of payment for the company in the drop-down menu.

A scanned copy of the proof of payment must be sent via the Campus section: Secretary's Office / Enrolment / Payment options.

The details you will need to make the transfer are as follows:

Important: if the company pays a percentage and the student the remaining percentage, the company's part must be paid by bank transfer, and the student's part using the available preferred payment option (transfer, direct debit or card direct debit).

The UOC offers a series of discounts. If you are entitled to any of these discounts, you should select them in the dropdown menu in the Discounts section at the time of enrolling. If you are entitled to more than one, you will have to choose the one that benefits you most.

Discounts for specific groups

If you are eligible for any of these discounts at the time of enrolling, you will have to accredit your eligibility by submitting the relevant documentation within a maximum period of 10 calendar days.

Large family status

Students having large family status recognized by Spain or by the appropriate body in the other countries are entitled to the following discounts, according to their category:

Large families in the special category: 15% discount. Large families in the general category: 7.5% discount

People with disabilities

Students with a level of disability recognized by Spain as being equal to or greater than 33%, or the equivalent level recognized by any country, are entitled to a 15% discount.

Victims of terrorism

Students (or their children or spouse) who have been acknowledged as victims of terrorist acts by the appropriate body in Spain, or any other country, are entitled to a 15% discount.

Victims of domestic violence against women

Students (or their dependent children) who have been acknowledged as victims of gender-based violence by the appropriate body in Spain, or any other country, are entitled to a 15% discount.

Discounts for the UOC community

Uoc community: 7% discount.

You can obtain this discount if you have done at the UOC free subjects, languages, seminars, customized training courses (UOC Corporate) or a specialization. If you are studying a university degree or master's degree but have not yet been titled, you will also be given the community discount.

UOC Alumni: 10% discount

You can obtain this discount if you have obtained an official degree (degree, bachelor's degree, diploma, engineering or university master's degree) or a master's or postgraduate degree from the UOC.

Business agreement: discount on consultation according to agreement

You can get this discount if you have a link with a company associated with the UOC.

Discounts for companies

The UOC offers discounts to companies that participate and support the training of their professionals, prior agreement with the UOC.

Professionals linked to any company or institution that maintains a collaboration agreement with the UOC will be able to benefit from advantages and discounts on the cost of tuition fees for training programs in the University's catalog.

Support programme for elite athletes

Students considered to be elite athletes are entitled to a discount on the enrolment fee.

Consulta la información del programa

If you're eligible for one of these discounts and you also enrol early, the discount for early enrolment will be applied first and then the other discount will be applied to the remaining amount.

By default and at zero cost, the UOC offers an insurance policy to students who enrol on courses with a minimum duration of one semester, and who reside in Spain (students with a Spanish DNI/NIE document with a Spanish address). This means that if after enrolling you find yourself in one of the situations covered by the insurance, the UOC can help you continue with your studies.

Students on bachelor¿s degrees, master¿s degrees, specialization programmes, postgraduate courses, open courses and Centre for Modern Languages courses are all covered.

+ Find out about the free insurance to continue studying in the event of unemployment or health problems

See who this programme is for and the new competencies that you can develop.

Some programmes belongs to an academic pathway. Find out about the studies with which you can achieve your goals.

Would you like more information?

Send us your details and we'll send you information on this programme and regarding UOC products, services and promotional activities.

- Select a programme

- It is necessary for you to read and accept the legal warning on Data Protection policy

- Incorrect verification text. Please try again.

- Name and Surname

- Contact e-mail address

- Language to receive information

- Postal code

- Invalid phone

We appreciate your interest. Your request details have been sent successfully. We will soon send the information you requested to your email address.

Your request couldn't be sent.

Please try again.

Humanitarian neutrality in contemporary armed conflict: a conversation with Nils Melzer

As with many humanitarian crises in the past, the international armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine has revived heated discussions on the humanitarian principles and their relevance in contemporary armed conflict. We have all been reminded how the principles, in particular the principle of neutrality, can lead to misunderstanding and even outrage, and why they nonetheless remain such an essential compass and operational tool in highly polarized situations.

In this week’s episode of Humanity in War, podcast host Elizabeth Rushing navigated these murky waters with Nils Melzer, the director of ICRC’s International Law, Policy and Humanitarian Diplomacy Department, exploring how the humanitarian principles apply to contemporary armed conflict.

I’d like to start by framing why we’re having this conversation. The fundamental humanitarian principles of humanity, impartiality, neutrality and independence constitute the four common principles to international humanitarian law and the Red Cross and Red Crescent movement. But they go beyond that, referenced by Médecins Sans Frontières, UN resolutions, the European Union, the African Union and other humanitarian organizations. These are cardinal points of a compass crucial for dealing with the operational and ethical dilemmas of humanitarian actions.

This rich foundation of the principles begs the question: why now? The movement codified the principles in 1965 and followed them for decades before that. So why are we having a conversation now and going ‘back to the basics’ about the nature of and need for the humanitarian principles?

I think, as you said, the current discussion was triggered most recently by the international armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine, which has resulted in strong polarization of public opinion and where everyone – governments, organizations, cultural and religious institutions, even private corporations and individuals – are expected to take sides. This trend has put pressure on the Red Cross to take sides and has given rise to questions about the validity and legitimacy of its neutrality and impartiality, but also its confidential bilateral approach with all parties to an armed conflict.

Now, I think it’s important to remember that this is not the first time this has happened. It’s a recurring phenomenon that usually arises in connection with any kind of a watershed event that polarizes public opinion. Today, it may be the international armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine. But similarly, something like this happened after 9/11, when we had the so-called ‘war on terror’, which was also very strongly politicized and there was a lot of pressure to take the ‘right side’.

This is a very valuable point, because sometimes when this issue arises, people think this is the first time the principles have been called into question, and it’s not a new phenomenon at all. I teach a class on international humanitarian law, and each semester, this is the issue that comes up: the controversy surrounding neutrality and trying to really unpack what it means. I tell my students during that class that different humanitarian organizations have different comparative advantages and that the ICRC is arguably the most ‘strictly’ neutral, MSF a little less so, all the way to the name and shame advocacy or activist organizations that you and I have both worked for in the past. Would you agree with this explanation? And if so, how do you think we can strike the right balance?

Clearly there are plenty of organizations that do humanitarian work and address humanitarian needs in action. They may be defending also certain legal standards such as human rights law or refugee law, or the protection, as we do, of victims of armed conflict. But the working methods of each organization can differ because they really depend on their specific mandates, and they have to enable those organizations to actually fulfill their mandate.

In our case, the mission of the ICRC is to protect the lives and dignity of victims of armed conflict and other situations of violence and to provide them with assistance. So clearly our working methods must allow us to do that, to work in very dangerous and violent contexts of armed conflict on the battlefield on both sides of the frontline. We have to be able to negotiate with all parties. We have to be able to access victims, whether they be in prisons or in refugee camps, on both sides of the battlefield. We are unarmed and we cannot force our way in, so our presence has to be accepted and respected and our activities have to be understood and protected by all parties to the conflict. And this only works if they understand the benefits of our presence and that we do not take sides, that we remain neutral.

On that point, everything that you listed there that we ‘have to be able to do’ needs to be put in the context of where we’re doing this. We are operating in conflict zones. This is our stage. We know that emotions very understandably run high there. So how can we do better at explaining to people who are being directly impacted by the effects of armed conflict that neutrality is a non-negotiable to being able to protect and assist people affected by the effects of war?

You’re absolutely right to point out the emotional aspect of it. I think anyone who’s worked in a in a war zone knows that their emotions are affected as well. We’re not indifferent. Neutrality is not a question of being indifferent to what’s going on or of having sympathy or not – it’s not even a question of morality. It is a guiding star that really gives us a compass, that gives us a direction, how we can navigate the extremely violent and emotional environment of an armed conflict safely to be able to actually bring assistance and protection to victims of armed conflict.

I think that’s really important. It’s not a moral stance; it’s an operating principle. In an armed conflict, just try to publicly take sides with one party and then go to the battlefield and try to protect all victims of that conflict. It’s not possible.

Let’s explore another aspect of our work that often comes under scrutiny, and that’s our policy of confidentiality. This is a policy, not a principle, which means it doesn’t carry the same non-negotiable weight. In fact, there is an ICRC Doctrine, Doctrine 15 , that outlines what actions our organization can and cannot take in the event of violations. It includes a fourth and final recourse of public criticism.

With this in mind, could you explain to us a bit how the ICRC policy of confidentiality interrelates with the fundamental principles? What’s the difference and why is all of this so important in practice?

Neutrality and impartiality are part of our identity. This is who we are as an institution. Just like a judge in a in a trial, as humanitarians in armed conflict, we can never take sides. We cannot fulfill our function if we ever take sides. And just like a judge, we may have a personal opinion, we may have personal emotions, but we cannot allow that to affect what we are doing professionally. Therefore, our neutrality is an institutional principle that is non-negotiable. We can never, ever take sides.

Confidentiality, on the other hand, is the way we do our work. It provides a protected space where we can interact confidentially and diplomatically with belligerents. We can express our concerns and transmit our observations to them, even if they concern violations of the laws of war. It allows for a protected space where we can interact with them without them being immediately exposed to the public and potentially even to judicial proceedings. If those confidential and bilateral interventions do not succeed in persuading the belligerent, if we have repeated violations of humanitarian law, if we have no other way of influencing those actors in a confidential and bilateral way, we may leave that path and escalate to the next level, which would be to try to share our concerns with other States that might be able to influence those belligerents, or international organizations that might be able to influence again in a confidential and bilateral way. If that doesn’t prove successful, then we can also go to the public and make a so-called declaration on the quality of our dialogue with the belligerents, which basically is a first step to the public to express our concerns without still naming and shaming. And the very last at the very end of that escalation process would be a public denunciation of violations of international humanitarian law.

So there is an escalation process, with our preference being to persuade parties to the conflict to respect international humanitarian law and to correct any misconduct on their own. And we stand ready to support them, to train them, to provide them with guidance on that. As long as that dialogue is fruitful and produces results, we will not go public.

To throw another wrench into the works, we can’t overlook the ubiquitous communications backdrop. Humanitarians are no longer working in a world of telegrams and newspapers, but rather an increasingly interconnected and complex web of human discourse where misinformation, disinformation and hate speech can and does spread like wildfire. So how can we, as the ICRC, communicate the humanitarian principles clearly in this age of 280 character limits and misinformation cutting us off at the knees? What’s our best strategy?

I think we have to understand where the criticism is coming from, and most of it may not even be malicious. It’s understandable. Emotions, as you said, are running high. We feel hurt by what we see in the media, by the news we get about all the suffering that’s caused by armed conflict. And we tend to take sides. That’s a human tendency. That’s natural, and that’s a normal reaction to an abnormal stress situation.

But we are professionals working in a very difficult environment. So we have to try to explain who we are and why we take those measures in the way we do. Criticism often comes from people who are far away from the battlefield, who may not be aware of what the consequences would be of us changing our stance. If we lose access to the victims, who will go and protect them?

I think we have to ask those who we assist and visit in prisons, in refugee camps and hospitals and battlefields all over the world whether they would like us to be neutral or whether they would like us to take sides and condemn publicly at the cost of losing access to them. We have to ask the mother – whose son we are keeping alive with her letters in prison – whether she would like us to be neutral and have access, or have at least a hope to get access to her son, or whether she would like us to take sides and lose that access. Because we’re the only ones who may be able to someday escort him out of prison alive.

I think this is really the trade off that we have to communicate. That’s what neutrality is about and that’s what’s impartiality is about. And this is what our mission is about and who we are.

Thank you for bringing in that very human element to the work, which is an excellent segue to my last question, about the principle of humanity. The purpose of the principle of humanity is ‘to protect life and health and to ensure respect for the human being. It promotes mutual understanding, friendship, cooperation and lasting peace among all people’. These are words of love, essentially.

We have colleagues who have been called naïve before for pointing to the principle of humanity in appealing to actors to ‘do the right thing’, instead of advocating for compliance by aligning an actor’s interest (for example political or economic) with the law. What is your experience from previous roles with the principle – and overall concept – of humanity and getting actors to comply with the law?

Thank you for that question. I think it’s a very important one, and there are many memories that come to mind from my interactions with armed actors in the field. I’d like to make two points here.

First, we often presume that without our intervention as the ICRC and the restraints of the law, military forces and their soldiers would engage in senseless destruction and killing, committing war crimes with impunity. We sometimes forget that the laws of war have developed from the battlefields and that throughout history it was the warriors themselves who developed very strict codes of honour of what conduct was considered to be acceptable in war. This has developed through time and certainly requires stronger enforcement. But my own experience is that soldiers actually often suffer from the lack of clear guidance on how to ensure they’re doing the right thing. They are often traumatized, not as much by the brutality of the armed conflict, but by the haunting question of whether they have actually done the right thing. So the principle of humanity is not some kind of an academic concept, but it is the one guiding star, as you say, which allows us to retain our sanity in the brutal environment of armed conflict. It’s really a common value that is shared by all of us.

The second point I’d like to make is that the principle of humanity that you read out also points far beyond just responding to humanitarian needs, but guides us towards promoting peace and conflict prevention to take a stronger stance also in preventing humanitarian needs and human suffering from arising in the first place. I think here we as an organization can also in the future take a slightly stronger stance without getting entangled in the politics of it, just from a purely humanitarian perspective.

- John Lobor, Humanitarian principles in action: a Q&A with the South Sudan Red Cross , November 17, 2022

- Ariana Lopes Morey, What does ‘back to basics’ mean for gender and the fundamental principles? , September 1, 2022

- Fiona Terry, Taking action, not sides: the benefits of humanitarian neutrality in war , June 21, 2022

- Robert Mardini, Back to basics: humanitarian principles in contemporary armed conflict , June 16, 2022

Voluntary reports: a new tool ‘toward a universal culture of compliance with IHL’

14 mins read Back to basics: humanitarian principles in contemporary armed conflict / Humanitarian Action / Humanity in War podcast / Law and Conflict Giulio Bartolini

Codifying IHL before Lieber and Dunant: the 1820 treaty for the regularization of war

13 mins read Back to basics: humanitarian principles in contemporary armed conflict / Humanitarian Action / Humanity in War podcast / Law and Conflict Jacob Coffelt

There are no comments for now.

Leave a comment

Click here to cancel reply.

Email address * This is for content moderation. Your email address will not be made public.

Your comment

The Laws of Armed Conflict & International Humanitarian Law

11 Nov 2024 - 22 Dec 2024

Hamilton, Tauranga

LAWS476, LEGAL476, LAWS576

This research seminar paper provides an advanced-level examination of critical issues in the Laws of Armed Conflict and International Humanitarian Law. Students complete a supervised research project of up to 12,500 words.

Teaching Periods and Locations

- 24B (HAM) Cancelled Contact the School or Faculty Office for more information.

- 24B (TGA) Cancelled Contact the School or Faculty Office for more information.

If your paper outline is not linked below, try the previous year's version of this paper .

Indicative Fees

You will be sent an enrolment agreement which will confirm your fees. Tuition fees shown are indicative only and may change. There are additional fees and charges related to enrolment - please see the Table of Fees and Charges for more information.

Available subjects

International relations and security studies, legal studies, additional information.

Subject regulations

- Paper details current as of 27 Jan 2024 23:40pm

- Indicative fees current as of 8 Apr 2024 01:30am

You’re viewing this website as a international student

You’re currently viewing the website as a International student, you might want to change to domestic.

You're an International student if you are:

- Intending to study on a student visa

- Not a citizen of New Zealand or Australia

You're a domestic student if you are:

- A citizen of New Zealand or Australia

- A New Zealand permanent resident

- CCOE Seminar Series

Civilians in Conflict: ‘A Ukraine Case Study’ (12/13 JUN 2024)

Two years after Russia has lounged a full scale war against Ukraine, the war continues to cause extreme civilian harm and military casualties, affecting the lives of millions. From the annexation of Crimea to the sustained confrontations in the Donbas region, this protracted conflict has shed light on the profound humanitarian crises and geopolitical complexities inherent in modern warfare. Most importantly, it highlights the urgent need for effective intervention strategies to mitigate harm and safeguard vulnerable individuals. Reflecting on the past and analysing the current realities is crucial in paving the way for peace, reconciliation and a more cohesive society.

In this online seminar, we aim to nurture and strengthen the discussion of the complex humanitarian aspects of Civil-Military Cooperation in conflict zones, specifically focusing on the Ukraine crisis. The effective collaboration between humanitarian organisations and military forces plays an essential role in the protection of the most vulnerable, facilitating humanitarian efforts, promoting stability, and aiding in peacebuilding.

Through expert presentations and a moderated Q&A session, we aim to shed light on the challenges faced by civilians, explore protection strategies for protecting and supporting them, and identify best practices for promoting their well-being and safety in volatile environments. Valuable lessons will be drawn from the Ukrainian CIMIC experience, highlighting unique strategies and challenges encountered in this context.

- Get involved

- Livelihoods in Sudan Amid Armed Conflict (English) pdf (0.8 MB)

Livelihoods in Sudan Amid Armed Conflict

Livelihoods in Sudan Amid Armed Conflict (English)

April 12, 2024

Pervasive severe food insecurity in Sudan during the current armed conflict necessitates urgent and extensive interventions to enhance food aid, revitalize agricultural systems, and restore supply chains, to mitigate the food crisis and prevent further escalation.

The joint report from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) titled "Livelihoods in Sudan amid Armed Conflict” assesses the social and economic impacts of the ongoing armed conflict on rural Sudan. The report is based on analyses of a comprehensive survey of rural households across the country that both organizations conducted from November 2023 to January 2024, including 4,504 households.

Document Type

Regions and countries, related publications.

Publications

Intellectual property models for sustainable development.

Executive Summary of the report: Intellectual Property Models for Sustainable Development Since the launch of UNDP Accelerator Labs Network in 2019 and within e...

2024 Pacific Snapshot - Asia-Pacific Human Development Re...

While progress across several key indicators has been made, the UN Development Programme Pacific Snapshot of the 2024 Asia-Pacific Human Development Report high...

Annual Report 2023: A Malaria Free Vanuatu

Despite multiple challenges, including the COVID-19 pandemic and tropical cyclones causing interuptions to health services and responses to malaria cases, the M...

Annual Report 2023: Multi-Country Western Pacific Integra...

The Multi-Country Western Pacific Integrated HIV/TB Programme, supported by the Global Fund, continued to face challenges throughout 2023, primarily as a resul...

Pre-feasibility studies for the implementation of the sol...

The report presents the results of pre-feasibility studies for 37 projects in 18 partner cities as regards the implementation of the new ESCO Solar Power Plants...

Recommendations on Financial Incentives Schemes to Suppor...

The report elaborates on key recommendations for designing Super ESCO in Ukraine, best practices of fefinancing energy efficiency investments, as well as recomm...

- Open access

- Published: 10 April 2024

War related disruption of clinical tuberculosis services in Tigray, Ethiopia during the recent regional conflict: a mixed sequential method study

- Kibrom Gebreselasie Gebrehiwot 1 ,

- Gebremedhin Berhe Gebregergis 2 ,

- Measho Gebreslasie Gebregziabher 2 ,

- Teklay Gebrecherkos 1 ,

- Wegen Beyene Tesfamariam 1 ,

- Hailay Gebretnsae 3 ,

- Gebregziabher Berihu 2 ,

- Letebrhan Weldemhret 3 ,

- Goyitom Gebremedhn 3 ,

- Tsegay Wellay 2 ,

- Hadish Bekuretsion 3 ,

- Aregay Gebremedhin 4 ,

- Tesfay Gebregzabher Gebrehiwet 2 &

- Gebretsadik Berhe 2

Conflict and Health volume 18 , Article number: 29 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

38 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

More than 70% of the health facilities in Tigray, northern Ethiopia, have been totally or partially destroyed by the recent war in the region. Diagnosis and management of tuberculosis were among many health services that suffered. In this study we assess the status of tuberculosis care in health facilities of Tigray during the recent war and compare it with the immediate pre-war state.

Using sequential mixed method, we analyzed and compared the availability of diagnostic services in 69 health facilities and the utilization of tuberculosis care in 50 of them immediately before the war (September-October 2020) and during the war (November-July 2021). TB focal persons in each selected health facility were interviewed to evaluate the status of diagnostic services. Patient service utilization was assessed using health facility registrations. We also compared the average monthly case detection rate of multidrug resistant tuberculosis in the region before and during the war. We computed summary statistics and performed comparisons using t-tests. Finally, existing challenges related to tuberculosis care in the region were explored via in-depth interviews. Two investigators openly coded and analyzed the qualitative data independently via thematic analysis.

Among the 69 health facilities randomly selected, the registers of 19 facilities were destroyed by the war; data from the remaining 50 facilities were included in the TB service utilization analysis. In the first month of the war (November 2021) the number of tuberculosis patients visiting health facilities fell 34%. Subsequently the visitation rate improved steadily, but not to pre-war rates. This reduction was significant in northwest, central and eastern zones. Tuberculosis care in rural areas was hit hardest. Prior to the war 60% of tuberculosis patients were served in rural clinics; this number dropped to an average of 17% during the war. Health facilities were systematically looted. Of the 69 institutions assessed, over 69% of the microscopes in health centers, 87.5% of the microscopes in primary hospitals, and 68% of the microscopes in general hospitals were stolen or damaged. Two GeneXpert nucleic acid amplification machines were also taken from general hospitals. Regarding drug resistant TB, the average number of multidrug resistant tuberculosis (MDR TB) cases detected per month was reduced by 41% during the war with p-value < 0.001. In-depth interviews with eight health care workers indicated that the main factors affecting tuberculosis care in the area were lack of security, health facility destruction, theft of essential equipment, and drug supply disruption.

Conclusion and recommendation

Many tuberculosis patients failed to visit health facilities during the war. There was substantial physical damage to health care facilities and systematic looting of diagnostic equipment. Restoring basic public services and revitalizing clinical care for tuberculosis need urgent consideration.

Introduction

The recent war in Tigray, Ethiopia, devastated the health care system, leaving 85% of the health centers and 70% of the hospitals partially or completely non-functional. They were looted and destroyed by combatants, as reported by Médecins Sans Frontières [ 1 ]. Some medical personnel were put to death while others fled or were forcibly relocated. Of 312 ambulances in Tigray, 274 were stolen or destroyed [ 1 , 2 ]. In addition, the war caused massive civilian displacement, starvation, overcrowding, and the shutdown of basic public services (telecommunication, banking, and transportation). Nearly three million civilians were displaced internally or fled to Sudan [ 3 ]. When active fighting decreased, the government imposed a siege. The war created fertile ground for the spread of TB and emergence of drug resistance. Under such conditions, TB-related morbidity usually doubles or triples [ 4 ].

In 2020, just before the conflict, there were about 6,697 tuberculosis (TB) patients (including 89 with multidrug-resistant TB), 43,000 people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) patients, and 24,253 diabetes patients on follow-up [ 5 ].

We assessed the availability and utilization of TB clinical services in Tigray during the recent war (between November 2020 and July 2021) and compared it with the pre-war state. Furthermore, we assessed the challenges of providing TB clinical services in the region, including the damage to laboratory services. This will hopefully be an input as the region struggles to recover.

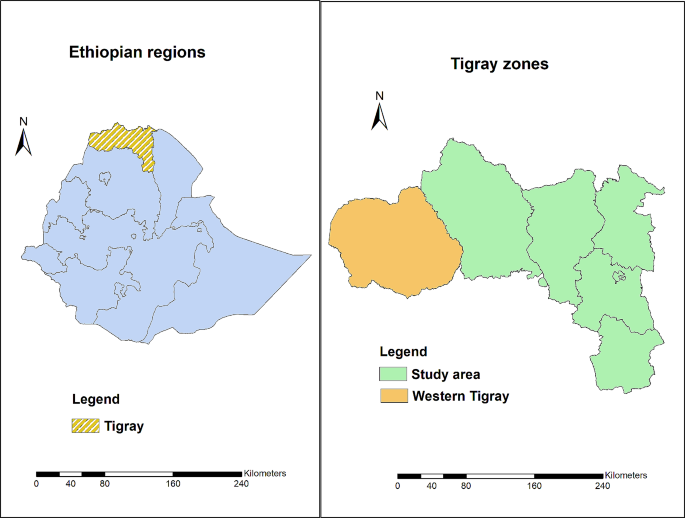

Tigray is one of twelve regional states in Ethiopia. It is situated in the northernmost part of the nation, bordering Eritrea to the north, Sudan to the west, the Amhara region to the south, and the Afar region to the east. As of 2022, the region’s population was estimated at 5.7 million ( https://www.citypopulation.de/en/ethiopia/admin/ET01__tigray/ ). Before the war, Tigray had two referral hospitals, 14 general hospitals, 24 primary hospitals, 231 health centers, and 741 health posts in its 7 zones (Refer to Fig. 1 ) [ 8 ]. TB diagnostic and treatment services were provided free of charge in all public health facilities.

During the study period Western Tigray was in the hands of foreign forces, with reports of ongoing ethnicity-based massacres of civilians. Access to the area was also denied to United Nations investigators and journalists. It was therefore excluded and the study conducted in the remaining six zones.

Map of Ethiopia showing the location of Tigray and its different zones

Study design and population

We used an explanatory sequential mixed method. First, we collected TB patient data (both susceptible and multidrug resistant forms) from health facility registries and we interviewed TB focal persons to assess laboratory-related damage. Next, we carried out in-depth interviews with TB case team coordinators, TB focal persons, laboratory staff, and medical directors to gather qualitative data regarding the difficulties faced in the diagnosis, management and treatment of TB.

Sample size determination and sampling procedures

Out of 229 health facilities in six zones, we randomly selected and visited 69 facilities (six general hospitals, twelve primary hospitals, and 51 health centers). Damage assessment related to laboratory diagnostics was possible in all 69 health facilities. However, we were unable to obtain the registers of 19 health institutions, as they were destroyed during the war; thus, TB service utilization data were collected from the 50 health facilities only. Eight in-depth interviews were conducted and saturation of information was used to indicate when to terminate recruitment and interview. The study participants were selected based on their position, professional relevance, and work experience. The participants were from a health center, a referral hospital, a reference laboratory, a district health office, and regional health bureau.

Data collection procedure and quality assurance

We developed a data abstraction format for the quantitative data collection. This contained the name and location of the health facility (urban or rural), total number of TB patients seen per month (September-July), the number of new MDR TB patients registered in any given month during the study period, and whether the patients received treatment. We used a different data collection tool to determine the amount of diagnostic equipment (microscopes, acid fast stain reagents, microscope slides, and GeneXpert machines) at each medical facility prior to and during the conflict. This data was used to evaluate the damage sustained by individual laboratories.

Health professionals experienced in data collection were recruited for data collection and the study team supervised the process. Four experienced investigators conducted the IDI in private settings with minimum noise. The demographics of respondents, the state of TB-related services in the respondent’s medical facility before and after the war in terms of diagnostics, the sufficiency of supplies, the effectiveness of the health delivery system, the case detection rate, and treatment outcomes were the primary topics covered in the interviews.

One day of training was given to the data collectors and supervisors. A pretest of the instruments was conducted in three health facilities outside of the study setting. Comments forwarded by the discussants and supervisors were incorporated.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were developed using percentages and means with standard deviations. We used a t-test to compare the patient visit data before and during the war. We performed stratified analysis by setting (urban vs. rural) and by zone.

With regard to the qualitative data, each audio-taped interview was reviewed multiple times, transcribed verbatim, and imported into Atlas.ti version 7.5 for coding and analysis. The transcribed and translated versions were read and reread. Filed notes and investigators’ memos were linked to the software. Two investigators openly coded and analyzed the data independently. The investigators held debriefing sessions throughout the data collection and analysis period. Thematic analysis was used; codes were developed based on the original terms used by participants, and then descriptions were subsequently developed followed by identification of the most frequently observed categories and development of themes.

Ethical clearance

Ethical clearance was obtained from Mekelle University College of Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (Ref.No. MU-IRB 2025/2022). Support letters were obtained from Tigray Health Bureau. In addition, permission was obtained from the head of each health facility before data collection. Verbal informed consent was obtained from each interview participant. Transcripts and voice recordings were kept on a password-protected computer and accessed only by the study team.

Quantitative section

Of the 69 institutions included in the study, we were able to analyze patient TB service consumption from 50 of them; as noted above, the registers of 19 health facilities were destroyed during the conflict, including nine from the Northwest zone, six from Central, two from Southeastern, and two from Southern zones 1 .

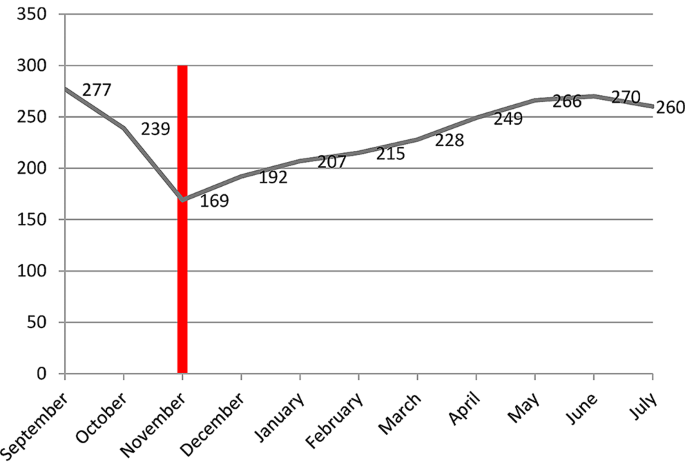

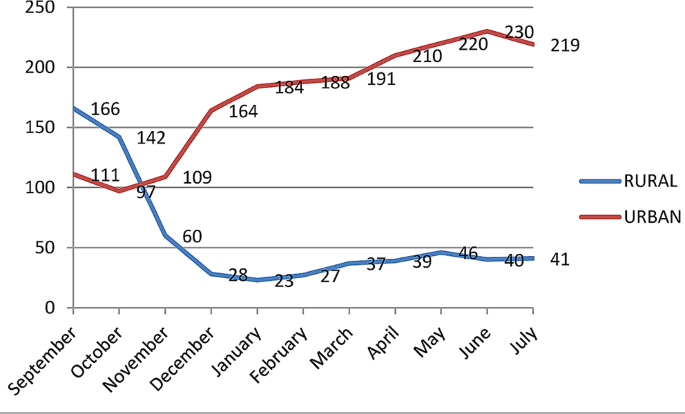

Pre-war (September-October), an average of 259 TB patients were seen each month in 50 health facilities. After the outbreak of war (November) this dropped to 169, a 34.5% reduction. Over time patients slowly resumed visiting, but the numbers remained lower than pre-war visit rate (Fig. 2 ).

Number of TB patients visiting study health facilities in Tigray before and during the war. The vertical line indicates the start of the war (November 4, 2020)

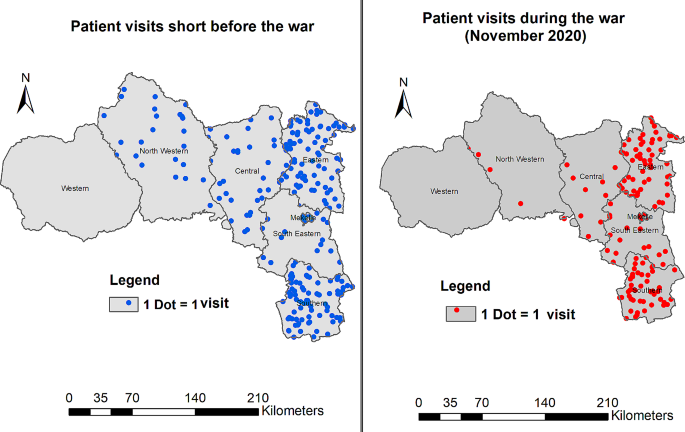

Reductions were statistically significant in the central, northwestern, and eastern zones (Table 2 ) and were higher in the central (72%) and northwestern (79%) zones (Fig. 3 ). Prior to the war 60% of tuberculosis patients were served in rural clinics; this number dropped to an average of 17% during the war (Fig. 4 ).

Map comparing tuberculosis patient visits shortly before (September and October average) and at the beginning of the conflict (November) in different zones of Tigray

TB patient visits in rural and urban health facilities before and during the war in Tigray

Multidrug-resistant TB patient care

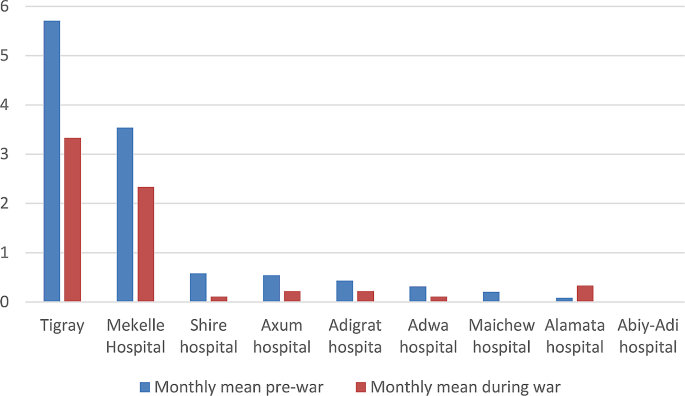

In comparison to the pre-war period, the monthly average number of MDR TB patients decreased by 41% during the war. This decrease was statistically significant with p-value < 0.001 (Fig. 5 ).

New MDR TB cases reported by health facilities before and during the war in Tigray

TB diagnostic service in health facilities

The data indicated clearly that microscopes and other equipment were systematically looted. Fifty-three (69.7%), 35 (87.5%), and 15 (68%) microscopes were taken from or damaged in health centers, primary hospitals, and general hospitals, respectively, as depicted in Table 3 . Acid fast bacilli (AFB) staining chemicals were unavailable in 82%, 25% and 33% of the health centers, primary hospitals, and general hospitals, respectively. In addition, 2 GeneXpert PCR machines were stolen in the study area.

Qualitative section

Socio-demographic status of participants.

The interview participants were aged 27—60 years. Their level of education ranged from diploma to MSc/specialist physician. We interviewed a regional TB case team coordinator, a district (woreda) communicable diseases expert, an internist from a tertiary hospital, two TB focal persons from a health center and a primary hospital, a laboratory official from Tigray Health Research Institute, a laboratory technician from a primary hospital, and a medical director.

Pre-war TB diagnosis and treatment services in Tigray

Before the war, clinical care of tuberculosis was available in all public health facilities free of charge. The private sector diagnosed 28–35% of new cases in Tigray, but once diagnosed, 80% of them were referred to public health facilities for treatment and follow-up. The Ethiopian pharmaceuticals supply agency (EPSA), a government body, supplied all TB medications and reagents every two months through its two hubs in Tigray. Prior to the war there were no major obstacles with supply.

AFB microscopy was available in all health centers and hospitals. The 14 GeneXpert machines in the region were located in the 14 general hospitals, two referral hospitals and in THRI (the Tigray Health Research Institute). ” “ Culture was available only in THRI. Before the war, THRI received about 1000 samples annually for culture and drug susceptibility tests . Tuberculosis focal person in Tigray Health Research Institute.

Prior to the war Tigray enjoyed a well integrated three-tier health care system. More than 1200 health extension workers played a key role in tuberculosis case detection in the community. They identified and referred presumptive TB patients to their catchment health centers. Some 80% of Tigray’s population lives in rural areas. Health extension workers received TB patients for directly observed therapy, DOTS treatment and follow-up close to their homes.

The health extension program was first started in Tigray 20 years ago with a main focus on maternal health and infectious disease prevention and later tuberculosis was added to the package. Tuberculosis case team coordinator from the regional health bureau.

The post office facilitated the transport of samples for GeneXpert and mycobacterial culture. Over time the case detection rate, treatment success rate and cure rate showed good improvement. All health facilities regularly reported all tuberculosis data (diagnosis, treatment and outcome) quarterly to the region’s health bureau using DHIS2.

TB diagnosis and treatment services in Tigray during the war

When Tigray was occupied by the allied forces (mainly Ethiopian National Defense Forces and Eritrean troops), a region-wide curfew was imposed. For two months, all basic public services including telecommunication, electricity, banking and transportation were stopped. Even ambulances were not allowed to work. Many health facilities were used as military stations, ruined deliberately and looted. Many health care workers, fearing for their lives, fled.

They used our hospital as a camp and took our microscopes. ” “We were running for our lives, but we were visiting the hospital occasionally. Five of the 10 patients came to the hospital after some stabilization, and I told them to go to Mekelle [the city least affected by the war and 72kms far]. A nurse from a primary hospital.

The largest hospital in Tigray, Ayder Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, located in the state capital Mekelle, was not directly attacked. But the surge of internally displaced people and lack of resources severely hampered patient care.

Our TB clinic served many patients asking for anti-TB medication but without any documents or referral. They came from the rural areas. An internist from Ayder Hospital.

About two months after the start of the war, active war became localized to some specific areas in Tigray and many public services (telecommunication, banking and transportation) began providing limited services. After eight months of occupation, the Tigray Defense Force expelled Ethiopian National Defense Force and Eritrean troops from Tigray. The federal government responded by blocking all telecommunication, electricity, banking and transportation and imposing a complete blockade, including food and fuel. It also suspended civil servant salaries and severely restricted the supply of anti-TB and other medications.

We walked on foot to and from the health facilities because there was no transportation as a result of fuel shortage. But at least we enjoyed peace and there was no one who would kill us. A nurse from a primary hospital. Only moral values kept us working without any payment for 14 months. An internist from Ayder Hospital.

Steps towards recovery

At the time of writing, most part of Tigray is free of active conflict after 2 years of all rounded siege, though the western Tigray, some part of southern Tigray and many areas bordering Eritrea remain tenuous. Telecommunications, banking, and other public services are functioning.

Tracing patients who were lost to follow-up is a challenge. Laboratory testing is essential to check for development of drug resistance (multidrug or extensively drug resistant). For patients with MDR TB, there are no second-line medications.

We can’t talk about TB control without having even a microscope. Patients who came back after stopping medications will require either GeneXpert test or drug susceptibility tests to make sure the disease hasn’t progressed to the next stage of resistance, but we don’t have them. Currently, GeneXpert is functional only in Mekelle. A health bureau TB coordinator.

Other interviewees were less pessimistic. An official at the THRI laboratory said they had organized mass screening in IDP centers for tuberculosis and other diseases, and they have found some TB patients lost to follow up, including MDR TB patients. These patients have been linked to facilities in Mekelle. They also hope to distribute 6000 anti-TB kits, some microscopes and reagents in collaboration with EPSA.

In this study, we assessed the status of clinical care related to TB services and its utilization by patients in health facilities in Tigray during the war period and compared it with the short and immediate pre-war period. The damage sustained by laboratories was assessed and challenges to the regional TB prevention and control program evaluated.

At the start of the conflict the number of TB patients using TB related medical services decreased by 34% in Tigray, by 79% in the northwest. This reduction persisted throughout the duration of the study, though it got progressively milder. A 38% increase in patient flow to Mekelle and Southeastern zones only partially compensated the 254% reduction in the other four zones. Mekelle and Southeastern zones are located in the center of Tigray and the war was most active in the peripheral part of the region. The large decrease in the detection of multidrug resistant forms of tuberculosis is very worrisome.

The primary causes of the decreased service utilization were the intentional destruction of medical facilities, the blockade of essential pharmaceuticals, the targeting of civilians and security fears, the migration of patients (both internal and abroad), and the cessation of critical public services. These results align with other studies and reports from Tigray [ 1 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. Health institutions in the study area have lost more than 75% of their TB laboratory diagnostic capacity with 103 of 138 microscopes having been stolen or damaged. The global objective of delivering patient-centered tuberculosis care is undermined by patients having to travel from their communities to metropolitan health institutions in order to receive medical care [ 10 ].

When TB patients cannot access appropriate care their options are limited: they can move to less affected areas, look for alternative medicine from traditional healers and religious sites, or die at home. Ethiopians frequently travel to holy water sites in search of remedies [ 11 , 12 ]. These all could result in the disease spreading widely, leading to higher mortality and the emergence of drug resistance. Currently the nation has a relatively low MDR TB prevalence, just 1.1% of newly diagnosed cases and 7.5% of those who have received treatment [ 13 , 14 , 15 ].

Patients who migrate in large numbers to safer areas run the risk of spreading the disease during travel and when they seek shelter in internally displaced person shelters. IDP centres are too often characterized by hunger and overcrowding. Moreover, medical facilities in less impacted areas are unlikely to be able to deal effectively with a sudden surge in demand. Once in refugee camps, the stigma associated with TB is high. This can reduce patients’ health-seeking behaviour and compliance with medications [ 16 ]. These patients not only continue to transmit the disease but are also at high risk of death (up to 2/3rd of them) or severe disability [ 17 ]. In addition, a substantial proportion of MDR TB patients with primary drug resistance and associated mortality could be anticipated in the region as has been shown in previous armed conflicts [ 18 ].

Continuation of the TB program in countries with complex emergency situations is possible, as reported in different studies [ 16 ]. However, this requires a strong commitment from governmental and nongovernmental actors. During the Tigray war, no government or non-governmental agency was able to sustain the tuberculosis program in the region, despite repeated pleas from the region’s healthcare workers.

The health system in Tigray has sustained enormous damage: interruption of childhood vaccines (including vaccines against TB), migration of health care workers, destruction of health facilities, looting of medical equipment, stock-out of essential supplies, and dismantled referral and reporting system. Restoration of this system requires much work and investment. Healthcare providers who do not receive their wages for months are forced to migrate. This requires an urgent solution [ 19 ].

This study has several limitations. The clinical TB service utilization part of the study covered only the first part of the war (eight months) and excluded areas worst affected (western Tigray and villages bordering Eritrea) for security reasons. The comparative pre-war period, the two months immediately before the war, may not be representative as the looming war could have affected TB care even before the war. Any or all of these factors can lead to underestimation of the impact of the war. In addition, data from 27% of the study health facilities were unavailable due to the damage to the health facilities or TB registries and the number of TB cases in the study might have been underestimated (both before and during the war). Regarding the interviews, the process might have been influenced by the researchers’ background, experience, prior assumptions, and values. This may have shaped the conversation and affect the participants’ replies.

We propose undertaking a more comprehensive study assessing the prevalence of the disease in the population and the magnitude of lost to follow-up patients.

The war has resulted in enormous disruption of TB care and requires urgent restoration. The result will be higher mortality, higher disease prevalence, and possibly different patterns of disease, including higher rates of drug resistant TB. Bringing the region back to the pre-war level of TB diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring will take many years and considerable investment.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed is put with the manuscript as an additional file.

MSF. Health facilities targeted in Tigray region, Ethiopia/ MSF [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.msf.org/health-facilities-targeted-tigray-region-ethiopia .

World Peace Foundation | The Fletcher School Tufts University. Starving Tigray: How Armed Conflict and Mass Atrocities Have Destroyed an Ethiopian Region’s Economy and Food System and Are Threatening Famine. 2021;1–66.

Pichon E, Ethiopia. War in Tigray. Background and state of play. EPRS | Eur Parliam Res Serv. 2022;(December).

Kimbrough W, Saliba V, Dahab M, Haskew C, Checchi F. The burden of tuberculosis in crisis-affected populations: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:950–65.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Tigray Health Burea. Annual bulletin 2021.

Amnesty International. I Don’t Know if they Realized I was a Person: Rape and Other Sexual Violence in the Conflict in Tigray, Ethiopia. 2004;10:17–9.

Amnesty International. Report 2022/2023 - The state of the world’s Human Rights [Internet]. 2023. Available from: www.amnesty.org.

Amnesty International. Northern Ethiopia - Humanitarian Update _ Situation Reports.

MSF forced. to suspend majority of healthcare activities in Ethiopia despite enormous needs.

World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2021 [Internet]. 2021. Available from: http://apps.who.int/bookorders .

Derseh D, Moges F, Tessema B. Smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis and associated risk factors among tuberculosis suspects attending spiritual holy water sites in Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2017;17(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2211-5 .

Kebede Ketema A. Assessment towards use of holy water as complementary treatment among PLWHA, Northeast, Ethiopia. Am J Intern Med. 2015;3(3):127.

Google Scholar

Federal Democratic Republic Of Ethiopia Ministry Of Health National Comprehensive Tuberculosis. Leprosy And TB/ HIV Training Manual For Health Care Workers. 2017;(July).

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. National Strategic Plan Tuberculosis And Leprosy Control (2013/14-2020). 2017.

Plan NS, Control L, November. 2017. 2020;13 (November 2017).

Munn-Mace G, Parmar D. Treatment of tuberculosis in complex emergencies in developing countries: a scoping review. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33(2):247–57.

Gele AA, Bjune GA. Armed conflicts have an impact on the spread of tuberculosis: the case of the Somali Regional State of Ethiopia [Internet]. 2010. Available from: http://www.conflict and health.com/content/4/1/1 .

Hargreaves S, Lönnroth K, Nellums LB, Olaru ID, Nathavitharana RR, Norredam M, et al. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and migration to Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23(3):141–6.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Tigray’s healthcare workers. haven’t been paid in over a year – and bear the brunt of the war [Internet]. The conversation; [cited 2024 Feb 3]. Available from: https://theconversation.com/tigrays-healthcare-workers-havent-been-paid-in-over-a-year-and-bear-the-brunt-of-the-war-192344 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We want to acknowledge the staff of school of public health (Mekelle University), Tigray regional health bureau and Tigray health research institute for assisting in the data collection. We particularly thank Belaynesh Debesay from Tigray regional health bureau for collecting the MDR TB data. We also extend our thanks to Dr. Marc Clark for his thorough revision of the manuscript

The authors did not receive any funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Medicine, College of Health Science, Mekelle University, PO Box: 1871, Mekelle, Ethiopia

Kibrom Gebreselasie Gebrehiwot, Teklay Gebrecherkos & Wegen Beyene Tesfamariam

School of Public Health, College of Health Science, Mekelle University, Mekelle, Ethiopia

Gebremedhin Berhe Gebregergis, Measho Gebreslasie Gebregziabher, Gebregziabher Berihu, Tsegay Wellay, Tesfay Gebregzabher Gebrehiwet & Gebretsadik Berhe

Tigray Health Research Institute, Mekelle, Tigray, Ethiopia

Hailay Gebretnsae, Letebrhan Weldemhret, Goyitom Gebremedhn & Hadish Bekuretsion

Tigray Regional Health Bureau, Mekelle, Tigray, Ethiopia

Aregay Gebremedhin

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

KG and TGG contributed to the conception of the study, study design, data analysis, and manuscript writing. TGG, GBG, HG, HB, LW, GG, AG, GB, TW, TG, MG, WBT, and GB contributed to the research design, data collection, and analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kibrom Gebreselasie Gebrehiwot .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical clearance was obtained from Mekelle University, College of Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (Ref.No. MU-IRB 2025/2022). Support letters were obtained from Tigray Health Bureau. In addition, permission was obtained from the head of each health facility before data collection. Verbal informed consent was obtained from each in-depth interview participant.