Presentation of Christ at the Temple

* As an Amazon Associate, and partner with Google Adsense and Ezoic, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Presentation of Christ at the Temple by Giotto is a religious painting dated c.1304 - c.130. It is one of Giotto’s series called Scenes from the Life of Christ, located at Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel, Padua, Italy. The medium is Oil on a 200 x 185 cm canvas, and the style is Proto-Renaissance.

It is a series of images showing activities around a Jewish tradition, from entrance to the temple to completion of the procedure. Jesus Christ is known as the Saviour in the bible. This painting shows Jesus, just about to undergo one of the Jewish traditions, known as dedication. Traditionally, it was a requirement in the Law of Moses that every firstborn male is dedicated. 'As it is written in the Law of the Lord, every firstborn male is to be consecrated to The Lord.' Luke 2:23.

To the left, a woman presents a baby. A man stands behind her, and another woman behind the man. There is something special about the man and woman which is brought about by the woman behind them. These two have sort of yellow crowns on their heads, while the other woman doesn't have. According to the bible, the man is named Joseph while the woman is named Mary, and the two were Jesus' parents. The crown represents the divinity of the parents. Notably, these two were "chosen by God" to bring forth "The Saviour of the World" and hence the divine nature. The blue colour also adds to the chosen nature of the baby, since blue is a sign of royalty.

Joseph happens to hold two doves. In the biblical context, a family was required to offer a sacrifice in the temple. 'A pair of doves or two young Pigeons.' Luke 2:24. This action explains why the father presents the doves. According to biblical history, a low-income family would opt for doves rather than pigeons, which explains the records that the Saviour was lowly, and from a humble background.

Towards the left is a man holding a baby, and a woman stands behind them. The man represents Simeon, referred to as righteous and devout. The yellow crown also appears upon his head. The woman behind him is a prophetess known as Anna. She holds a script to represent her priestly role in the dedication. In another image, an angel hovers above Anna. The angel is a sign of acceptance of the divine baby, Jesus Christ, and also adds to the divine nature of the subject and tradition. In a later image, the man hands the baby back to the mother, which represents the end of the procedure. Presentation of Christ at the Temple by Giotto speaks volumes on the dedication of Jesus Christ and brings the reality of the procedure in a few images. From the divine crowns to the humility of the participants, the lowly yet divine life of Jesus is displayed.

More GIOTTO Paintings

Giotto.jpg)

The Arrest of Christ (Kiss of Judas)

Giotto.jpg)

Lamentation

Stefaneschi Triptych

Ognissanti Madonna

The Last Judgement

The Flight into Egypt

Adoration of the Magi

More renaissance artists.

Sandro Botticelli

Leonardo da Vinci

Albrecht Durer

Giotto.jpg)

Hieronymus Bosch

Article author.

Tom Gurney in an art history expert. He received a BSc (Hons) degree from Salford University, UK, and has also studied famous artists and art movements for over 20 years. Tom has also published a number of books related to art history and continues to contribute to a number of different art websites. You can read more on Tom Gurney here.

A Light to the Nations: Giotto’s ‘Presentation’

While celebrating the feast of the Presentation of Our Lord, we are invited to reflect on how we ourselves receive and recognize the Christ child. Am I a Simeon or an Anna?

The Christmas season has come to an end, and we have welcomed the joy of the Messiah, but have we recognized Him as the Savior of the World? When Simeon encounters Christ in the temple he recognizes that God’s promise to him “that he should not see death before he had seen the Lord’s Christ” (Luke 2:26) has been fulfilled. He also prophesizes to Mary that “a sword will pierce through your own soul also” (Luke 2:35).

In the famous fresco by Giotto, we are invited into the encounter between Simeon and the Christ. The left side of the painting portrays the Lord’s humanity in its radical simplicity. Joseph stands near holding two turtle doves to offer at the temple. Mary is the picture of motherhood, reaching out for her child in need.

The figures on the right half of the painting are enlivened with divine meaning and point to Jesus’ divinity – the angel flying overhead, the prophetess with the scroll. Look at the face of Simeon – full of awe and thanksgiving as he gazes at the face of God.

In contrast, the Child Jesus at the center of the fresco portrays his full humanity by reaching back to his mother. Surely we can all think of a time when we have seen a baby reject the arms of a stranger in favor of the comforting embrace of his mother.

Imagine Jesus as that sweet baby.

Simeon’s words at the temple are honored and repeated during the Liturgy of the Hours, prayed daily in Compline (Night Prayer). Each night, with the setting of the sun, we are reminded of our death, and the words of Simeon remind us of a life of faith, well lived.

Tonight, pray the Canticle of Simeon and then return to the image by Giotto:

Canticle of Simeon

Antiphon: Protect us, Lord, as we stay awake; watch over us as we sleep, that awake, we may keep watch with Christ, and asleep, rest in His peace. Alleluia!

Lord, now you let your servant go in peace; your word has been fulfilled: my own eyes have seen the salvation which you have prepared in the sight of every people: a light to reveal you to the nations and the glory of your people Israel.

Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit; as it was in the beginning, is now, and will be forever. Amen.

Place yourself into the image, in the position of Simeon with Christ in your arms. What must that be like?

Imagine the relief and peace of Simeon that God’s promise to him has been fulfilled. He has beheld the Messiah and now his life is complete. Repeat the words of Simeon in the canticle – words of thanksgiving, praise, peace, and surrender. The encounter with Christ is enough for Simeon. His life is now complete. Is the encounter enough for you?

Want to hear breaking news first? Join us.

Username or email *

Password *

Remember me Login

Lost your password?

Your Collection

Log in to the harvard art museums, 1933.29: the presentation in the temple.

- Add to Collection

- copy = 'Copy Permanent URL', 2000)" data-behavior="tooltip"> Copy Link

- Reuse via IIIF

- $focus.focus($refs.osd_viewer), 250)};" x-tooltip.raw="Toggle Deep Zoom Mode" data-behavior="tooltip" target="_blank" > Toggle Deep Zoom Mode

Gallery Text

In 1496 and 1497, the daughter and son of the “Catholic Kings,” Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, wed the son and daughter of Emperor Maximilian I of Austria. This is one of eight panels from an enormous retable altarpiece for a church in Valladolid, Spain, believed to commemorate the alliance that united the kingdoms of Castile and Leon with the Holy Roman Empire.

The splendor with which this biblical scene is depicted befits the occasion. The Jewish temple where Christ is presented to the high priest Simeon has been envisioned as a Gothic cathedral, its interior adorned with heraldic devices and escutcheons. The unknown artist, likely a Spaniard active at the royal court, was clearly inspired by Netherlandish models. He excels at the depiction of costly materials and decorative details: brocade, ermine, embroidered cloth, marble, stained glass, pearls, jewels. In the background is a richly carved choir screen, with one shutter open, revealing the candlelit altar behind it.

Identification and Creation

Physical descriptions, acquisition and rights.

The Harvard Art Museums encourage the use of images found on this website for personal, noncommercial use, including educational and scholarly purposes. To request a higher resolution file of this image, please submit an online request.

Publication History

- Edgar Peters Bowron, European Paintings Before 1900 in the Fogg Art Museum: A Summary Catalogue including Paintings in the Busch-Reisinger Museum , Harvard University Art Museums (Cambridge, MA, 1990), p. 42, color plate; pp. 119, 370, repr. b/w cat. no. 814

- Angelica Daneo, The Kress Collection at the Denver Art Museum , Denver Art Museum (Denver, 2011), pp. 95-99, repr. p. 97 as fig 30.(e)

Exhibition History

- The Artistic Splendor of the Spanish Kingdoms:The Art of Fifteenth-Century Spain , Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, 01/19/1996 - 04/07/1996

- 32Q: 2500 Renaissance , Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, 11/16/2014 - 01/01/2050

Subjects and Contexts

- Google Art Project

Verification Level

This record has been reviewed by the curatorial staff but may be incomplete. Our records are frequently revised and enhanced. For more information please contact the Division of European and American Art at [email protected]

The Arena Chapel (and Giotto’s frescos) in virtual reality

Set the resolution to 8k! (use the gear icon) and take a guided virtual tour of the Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel, in Padova, Italy — thanks to Matthew Brennan. 360-degree video allows you to look around the interior freely, and provides a new perspective on this masterpiece of Italian Renaissance art.

See the frescoes up-close and at eye-level, as if you were floating right in front of them, thanks to a new approach developed by Mirror Stage Studio.

Narration by SmartHistory: www.smarthistory.org

Video production by Mirror Stage: www.mirrorstage.io

This video makes use of imagery available in the public domain, as well as provided by SmartHistory.

Video transcript

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] We’re in the Arena Chapel, a small private chapel that was connected to a palace that was owned by the Scrovegni family.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:13] It was the Scrovegni family who commissioned Giotto to decorate this chapel with frescoes.

Dr. Zucker: [0:20] It’s called the Arena Chapel because it’s next to an ancient Roman arena.

Dr. Harris: [0:23] When you’re inside it, as we are now, I have to say that it’s taller than I expected, and that feeling of being enclosed by images that happens when you’re in a space entirely covered with fresco.

Dr. Zucker: [0:38] There are lots of narrative scenes, but even in between those scenes are trompe l’oeil faux marble panels. We get the sense that there is inlaid stone, but in fact, this is all painting.

Dr. Harris: [0:52] That extends even onto the ceiling, where we have a star-studded blue sky with images of Christ and Mary and other saints and figures.

Dr. Zucker: [1:03] The Arena Chapel is organized in a very strict way. Three registers begin at the top and move downward. I think of it as a kind of spiral, that is, it tells a continuous story. It begins with Christ’s grandparents. It goes into the birth of Mary, her marriage, and then when we get down to the second register, we get to Christ’s life or ministry. Then the bottom register is the Passion; these are the events at the end of Christ’s life and immediately after his death.

[1:34] The impetus for the entire cycle can be seen at the apex of the triumphal arch on the opposite wall, with God, who calls Gabriel to his side, telling him to go to the Virgin Mary and announce to her that she will bear humanity’s savior, that she will bear Christ.

Dr. Harris: [1:53] Interestingly, when Giotto painted God, he inserted a panel painting, so that is not fresco. It’s interesting that he chose to paint it in a style that was more conservative, less earthly than the style that we see in the frescoes.

[2:09] Just to go back to that Annunciation and this wall, we begin to see the illusionism that we see throughout the cycles. If we look to Mary and the angel, Giotto has created an architectural space for each of them. These are not panel paintings with gold backgrounds that suggest a divine space. These are earthly settings for Mary and the angel.

Dr. Zucker: [2:33] There’s another great example of the way that architecture and the sense of space is constructed, even in this era before linear perspective.

[2:41] Two scenes below the Annunciation are these wonderful, empty architectural spaces, these rooms that have oil lanterns that hang from their ceilings, and there is such a delicate sense of space, of light and shadow. It is this bravura example of naturalism and it shows Giotto’s interest in the world, the present, the physical space that humanity occupies.

[3:07] The narrative cycle begins on the right altar side in the top register. It introduces Joachim and Anna, the grandparents of Christ.

Dr. Harris: [3:17] Mary’s parents.

Dr. Zucker: [3:18] Joachim begins by being thrown out of the temple.

Dr. Harris: [3:21] For his childlessness.

Dr. Zucker: [3:23] That’s right, he’s grown old without children. Don’t take this too literally, it’s not in the Bible. These are the extra stories that were added to the biblical narrative because people wanted to know what happened in between the events that really are mentioned in the Bible.

Dr. Harris: [3:38] Much of this is from a book called “The Golden Legend” that filled in narrative.

Dr. Zucker: [3:43] Let’s focus on the last scene on the right side of the upper register, which is the Meeting at the Golden Gate. To get here, what’s happened is that Joachim has prayed to God, wanting a child. Anna, his wife, has done the same, and they’ve both been visited and been told that there is hope.

[4:02] They’re shown coming together for the first time in front of Jerusalem, in front of the Golden Gate.

Dr. Harris: [4:09] Each now with the awareness that their desire for a child, this wish, has been fulfilled.

Dr. Zucker: [4:16] We have this wonderful example of the humanism of Giotto. We see their faces together. It is a kiss, it is incredibly intimate, so personal. Their faces come together, they touch and almost become a single face.

Dr. Harris: [4:32] We sense the warmth of their embrace, the warmth of the figures around them who watch, and something that we see throughout the cycle, figures who have mass and volume to their bodies, who exist three-dimensionally in space.

[4:48] Gone are the elongated, swaying, ethereal bodies of the Gothic period. Giotto gives us figures that are bulky and monumental, where drapery pulls around their bodies, and taken together with the emotion in their faces, it’s almost like we have real human beings in art for the first time in more than a thousand years.

Dr. Zucker: [5:12] Giotto — we think — was Cimabue’s student, and learned from that great master, who had begun to experiment with the chiaroscuro that you’re speaking of. This light and shadow, this ability to model volume, and form, and mass, but nothing like what Giotto has achieved here.

[5:30] You’re right, it is the coming together of both the chiaroscuro as well as the emotion, as well as the human interaction that creates the sense of the importance of our existence here on Earth.

Dr. Harris: [5:44] I would also add the clarity of the gestures and the narrative.

Dr. Zucker: [5:48] Look at the way in which the city is not rendered in an accurate way. We have a schematic view, and yet it’s everything we need. We have the gate of Jerusalem. Now, of course, Giotto had no idea what the architecture of Jerusalem looked like, yet from legend, he has created this golden arch and this medieval-looking fortified city.

Dr. Harris: [6:08] But the forms are simplified.

Dr. Zucker: [6:09] It’s a stage set, and he wants those figures to be front and center. They are what’s most important. If we move across to the other wall, the upper register continues the narrative. Mary is born, she’s presented in the temple, she’s married.

[6:25] And then, we get back to the altar side of the chapel, and there we reach the triumphal arch. We’re back to God the Father now, but below that we have the Annunciation.

Dr. Harris: [6:36] In the register below, now, we see scenes from Christ’s childhood including…

Dr. Zucker: [6:42] The Circumcision, the Flight into Egypt.

Dr. Harris: [6:45] …the Massacre of the Innocents. And then moving to the next wall, we begin the story of the ministry of Christ and his miracles.

Dr. Zucker: [6:54] As the story unfolds from scene to scene, Christ is often shown in profile, which is derived from the Roman tradition of coinage, which is the most noble way of representing a figure. He’s shown moving from left to right, which is the way that we’re meant to read the scenes.

Dr. Harris: [7:12] So Giotto is helping us to move through the narrative from one scene to the next. Here, we see Christ on a donkey, with the apostles behind him.

Dr. Zucker: [7:21] You’ll notice that Giotto does not really care to depict every single one of the 12 apostles. He’s really giving us only three or four faces, and the rest are just an accumulation of halos.

Dr. Harris: [7:33] There’s that legacy of symbolic representation that we think of as more medieval.

Dr. Zucker: [7:39] Look at the way in which the figures in the lower right, there are three of them, begin to pull off their outer garment. One man is pulling his arm out of his sleeve. The next is taking the garment off his head, and the final one is placing that garment at the feet of the donkey in an act of respect.

[7:57] But it is almost cinemagraphic. There is this idea that is, I think, part of the chapel as a whole, that it is about the movement of time. This is one of the most innovative aspects of the entire chapel, I think.

[8:10] One technical issue, if you look at Christ, there is a blue garment that’s wrapped around his waist, but the blue is almost entirely missing, and that’s because the Arena Chapel is painted in buon fresco, true fresco. That is, pigment is applied to wet plaster.

Dr. Harris: [8:26] When that happens, the pigment binds to the plaster, and the paint becomes literally part of the wall.

Dr. Zucker: [8:33] That’s right, the wall is stained. The problem is that blue was really expensive. Ultramarine blue came from lapis lazuli, which was a very expensive, semi-precious stone.

[8:44] Enrico Scrovegni, when he drew up the contract with Giotto, did not want the blue’s brilliance to be diminished by being mixed with the plaster. So he asked that it be applied as secco fresco.

Dr. Harris: [8:55] Dry fresco.

Dr. Zucker: [8:56] That’s right, on top of the wall, and the result is it didn’t last.

Dr. Harris: [9:00] Right. It didn’t adhere to the wall as well as the paint that was applied to the wet plaster. Sadly, that’s been flaked off, and we really have to use our imagination to fill in a brilliant blue on that drapery.

Dr. Zucker: [9:11] Let’s move on to the bottom register, to the end of Christ’s life. On the lowest register, the register that’s devoted to the scenes of the Passion, is the Arrest of Christ, also known as the Kiss of Judas.

Dr. Harris: [9:25] This is the moment when Judas leads the Romans to Christ, and they arrest him and take him away, and torture him, and ultimately crucify him. Remember, Judas is one of the 12 apostles, one of those considered closest to Christ. He betrays him for 30 pieces of silver.

Dr. Zucker: [9:45] And so it is all the more horrific — it’s all the more a terrible betrayal — because this is one of the people that Christ trusted most. Judas has betrayed Christ, not by pointing at him from afar, but with a kiss.

Dr. Harris: [9:58] There’s chaos here.

Dr. Zucker: [10:00] Well, that’s right. That idea of the embrace is really important, I think, because look at the way that Giotto has the figure of Judas’ arm and cloak wrapping around him, embracing him, enveloping him and — importantly — stopping him. Remember that in almost every scene we have noticed Christ moving from left to right in profile.

[10:22] But here, Judas is an impediment. His progress is stopped. This is literally arresting his movement forward.

Dr. Harris: [10:30] If we compare this, for example, to Duccio’s “Betrayal of Christ,” there, Christ is frontal. Here he’s in profile. You’re right, but it makes it so that Judas and Christ look at one another, look at each other in the eye. Judas is a little bit shorter. He looks up at Christ.

[10:46] There’s a sense of, to me, determination, but also at the same time maybe a hint of beginning to be sorry for what he’s done.

Dr. Zucker: [10:54] But still, corruption in that face versus the nobility of Christ’s.

Dr. Harris: [10:59] And the sense that Christ knew that this would happen, right, at the Last Supper. He said, “One of you will betray me,” and an acceptance of his destiny that we often see in images of Christ.

Dr. Zucker: [11:09] Let’s go back to that idea of chaos that you raised before. Giotto has created this sense of violence, and one of the ways that he’s done that is by reserving half the painting, the sky, just for those lances, for those torches, for those clubs, and the way in which they’re not held in an orderly way, but they are helter-skelter, crossing at angles.

[11:31] They create this almost violent visual rhythm that draws our eye down to Christ, down to Judas, but also feel[s] dangerous.

Dr. Harris: [11:40] There’s a sense of Judas and Christ anchoring the composition down as that chaos takes place around him. The most remarkable figure to me, though, is the figure who leans his left side of his body and his elbow out of the composition, almost right into our space.

Dr. Zucker: [11:58] It’s amazing actually, and it almost prefigures the way that Caravaggio, who centuries later will master this idea of breaking the picture plane.

Dr. Harris: [12:06] Then we also see another device that Giotto employs often in the Arena Chapel, and that is a figure with his back to us. That figure seems to be pulling something that’s out of the space of the panel, but look at his feet, perfectly foreshortened, grounded; there’s that sense of Giottoesque weight and monumentality to the figures, all of that modeling as we can follow the forms of the body underneath.

Dr. Zucker: [12:32] Giotto is giving us this full sensory experience. We have this crowd of figures, the sense of violence; the crowd is multiplied because we can see numerous helmets, which by the way would’ve originally been silver, but have oxidized.

Dr. Harris: [12:46] There’s a sense of a crowd pressing in, of all these faces watching what’s going to happen.

Dr. Zucker: [12:51] There’s one man on a horn who’s blowing creating this sense of energy; this audio that goes with this painting, that finishes the whole scene in its chaos and its drama.

Dr. Harris: [13:02] Giotto is a master of the dramatic.

Dr. Zucker: [13:05] One of the most powerful scenes in the chapel is the Lamentation. Christ has been crucified. He’s been taken down off the cross, and he’s now being mourned by his mother, by his followers.

Dr. Harris: [13:18] That word that we use for this scene, Lamentation, comes from the word to lament, to grieve.

Dr. Zucker: [13:24] This is one of the saddest images I’ve ever seen. We have Mary holding her dead son, and it reminds us of a scene that’s across the wall of the Nativity, where there is this tenderness and this relationship between Mary and her infant son, and now we see Mary again holding her adult, now dead son.

Dr. Harris: [13:45] On her lap, the way she does as a mother when he’s a child.

Dr. Zucker: [13:49] The idea of representing Christ as dead is a modern idea, putting emphasis on Christ as physical, as human.

Dr. Harris: [13:57] I think we’re struck by the simplicity of the composition. Giotto’s placing all of this emphasis on the figures. He’s simplified the background, but where we might expect to see the most important figure, Christ, in the center, Giotto’s moved him off to the left.

[14:13] The landscape is in service of drawing our eye down toward Christ, that rocky hill that forms a landscape that moves our eye down to Mary and Christ.

Dr. Zucker: [14:25] And at the top, there’s a tree, and the tree might look dead, but of course, it might also be winter. That tree might grow leaves again in the spring, and it is an analogy to Christ and his eventual resurrection.

Dr. Harris: [14:39] It’s not just that the dead Christ is on his mother’s lap. Look at how she’s raised her right knee to prop him up. Look at how she bends forward.

Dr. Zucker: [14:49] And twists her body.

Dr. Harris: [14:50] And puts her arms around him. One hand on his shoulder, another on his chest. She leans forward as if to plead with him to wake up, as if in disbelief that this could have happened.

Dr. Zucker: [15:02] At Christ’s feet, we see Mary Magdalene, with her typical red hair, who is attending to his feet, and of course, that’s appropriate given the biblical tradition as well because she had anointed Christ’s feet. There’s a real sense of tenderness there.

[15:16] Giotto is so interested in naturalism that he’s willing to show two figures where we only see the backs. There’s no representation of their faces at all. We would never have seen this in the medieval period.

Dr. Harris: [15:28] That’s because those figures provide no information to the narrative. All that they do is frame Christ and Mary. They draw our eye to those most important figures.

Dr. Zucker: [15:39] We look at Christ and Mary as they’re looking at Christ and Mary.

Dr. Harris: [15:42] Exactly. We become like them, surrounding the body of Christ. But they also help to create an illusion of space. It’s amazing to me how close they are to us. Their bottoms almost move out into our space. Giotto makes it clear that these figures are looking in, and therefore there is an “in” to look into. There’s space here for the human figures to occupy.

Dr. Zucker: [16:10] There are other-than-human figures here as well. There are angels, but these angels are not detached figures. They mourn as we mourn. They rend their clothing, they tear at themselves, they pull their hair. They are in agony.

Dr. Harris: [16:24] And they’re foreshortened. Like the figures with their backs to us, they assist in Giotto’s creating an illusion of space. Like the angels above them, the human figures display their grief in different ways. Some are sad and resigned and keep to themselves, other figures throw their arms out.

[16:44] There’s a real interest in individuality, in the different ways that people experience emotion. I always like to look at the feet, and the feet of the figure on the far right, that sense of gravity and weight of a figure, really standing on the ground, just like the figures who are sitting, not the medieval floating figures that we’ve come to expect.

Dr. Zucker: [17:05] Well, that ground is used for several purposes; to root those figures, but also to draw our eye down to Christ, or in another sense, to allow us to move out of the picture, because as we move from the Lamentation, we move to the next image, which is the scene where Christ says “Do not touch me” when Mary Magdalene recognizes him as he has been resurrected.

[17:28] You’ll notice that Giotto has continued that mountain. Our eye then moves down and so there is this visual relationship that is drawn between Christ’s death, Christ’s mourning, and Christ’s resurrection by the landscape that frames them.

[17:42] In the trompe-l’oeil depictions of inset stone, there is another painted scene in a little quatrefoil.

Dr. Harris: [17:49] Here we see Jonah being swallowed by the whale and we see water.

Dr. Zucker: [17:54] Or at least a giant fish.

Dr. Harris: [17:56] Throughout the chapel, we see this, an Old Testament scene being paired with the New Testament. Specifically, Old Testament scenes that, in some way, prefigured the life of Christ.

Dr. Zucker: [18:08] So Jonah is swallowed by this giant fish, by this whale, prays for forgiveness having betrayed God, and is delivered from this fish. It is a perfect Old Testament analogy to the New Testament story of Christ’s crucifixion and ultimate resurrection.

[18:24] It’s a tour de force of emotion. It’s such an expression of this late medieval period that is moving towards what we will eventually call the Renaissance. Below the Passion scene is even more painting. There are these marvelous representations of virtues and vices, that is, expressions of good and evil.

Dr. Harris: [18:43] We’re looking at the figure of Envy.

Dr. Zucker: [18:45] It’s one of my favorite figures.

Dr. Harris: [18:46] Here’s a figure in profile, engulfed in flames, clutching a bag.

Dr. Zucker: [18:52] But reaching with her other hand for something she does not have, something that she wants.

Dr. Harris: [18:56] Not content with what she has, she wants more.

Dr. Zucker: [19:00] She’s got huge ears. It’s as if every sense is attuned to what she does not have.

Dr. Harris: [19:06] We see emerging from her mouth a snake, who moves toward her eyes.

Dr. Zucker: [19:10] That’s right, it doubles back on itself because it is what she sees that bites her, in a sense.

Dr. Harris: [19:15] We have virtues and vices here because these are the good and evil that we confront, all of us, in our lives. And these are the things that decide at the day of judgment [whether] we go to heaven or hell.

Dr. Zucker: [19:26] They are in a sense abstractions of the ideas that are told in the stories above. The final virtue, as we move towards the exit of the chapel is Hope, and she is reaching upward, floating, a classicized figure.

Dr. Harris: [19:43] And she’s winged like an angel and is lifted up toward a figure on the upper right, who’s handing her a crown.

Dr. Zucker: [19:51] And so Hope, because she’s in the corner, is looking up towards the Last Judgment, and is of the same scale, and her body is in the same diagonal position as the elect in the bottom left corner.

Dr. Harris: [20:05] We see the elect, many of them with their hands in positions of prayer, looking up toward the enormous figure of Christ, the largest figure in this chapel.

Dr. Zucker: [20:15] We should say that the elect are the blessed, that is, these are people that are going to heaven, and you’ll see that they’re actually accompanied by angels that look so caring and gentle. They’re shepherding these people into heaven. If you look carefully, you can see that their feet are not on the ground. They’re actually levitating slightly. They’re rising up.

Dr. Harris: [20:35] These benevolent, generous expressions on the face of those angels as they look at all of these individuals who’ve made the choices in their lives that have led them to this moment of being blessed.

Dr. Zucker: [20:48] The choices that are laid out for us in the virtues and vices in the bottom panels. Just below the elect, you can see that there are what seem to be children, naked, coming out of coffins, out of tombs. Those nude figures are meant to represent the souls that are to be judged by Christ, who, as you said, sits in the middle.

[21:11] He sits here as judge, to judge those souls that are being wakened from the dead, to determine whether or not they are blessed and get to go to heaven or if they’re going to end up on the right side of this painting, in hell.

Dr. Harris: [21:24] This follows very standard iconography or standard composition of the Last Judgment, with the blessed, those who are going to heaven, on Christ’s right, and the damned below, on Christ’s left. Now, just either side of Christ, though, that division of left and right doesn’t happen.

Dr. Zucker: [21:43] That’s because this is heaven.

Dr. Harris: [21:45] There we see a court of saints, and around that mandorla, that full body halo around Christ, we see angels blowing trumpets.

Dr. Zucker: [21:55] These are images that come right out of the Apocalypse, the Gospel according to John.

Dr. Harris: [22:01] The Book of Revelation.

Dr. Zucker: [22:02] We have the angels announcing the end of time. We have angels above them rolling up the sky as if it were a scroll. These are images that we generally see in Last Judgments because they are in the text of the Bible.

[22:15] The scene of hell on the lower right with a large blue figure that is meant to represent Satan, surrounding him are souls being tortured in hell.

Dr. Zucker: [22:25] A lot of this imagery is inspired, I think, indirectly by the work of Dante, who had not so long ago written “The Divine Comedy,” which was extremely popular, and he describes the landscape of hell.

Dr. Harris: [22:38] And he equates the punishments of hell with the different kinds of sins that people committed. In the Last Judgment that we’re looking at, and because the patron here was concerned with the sin of usury, we see usurers featured. They’re being hung with the bags of money on the ropes that they’re hanging from.

Dr. Zucker: [23:00] Right. Usury is requiring interest for when you lend money. It’s basically just the act of banking. That was a mortal sin. In fact, Dante speaks at great length about the usurers who have their money bags hanging from their necks and are in one of the lowest of the circles of hell.

[23:17] Below the usurers, you can actually make out a specific individual, also hanged. This is Judas, the disciple that betrays Christ.

Dr. Harris: [23:26] So anyone leaving the chapel from this exit would look up at this scene of the Last Judgement, up at the cross carried by two angels. Perhaps they would notice that figure that I just noticed, a figure behind the cross, grasping it for dear life, and would also have looked up and have seen Enrico Scrovegni himself, the patron, offering this chapel to the Three Marys.

Dr. Zucker: [23:53] As the public would have walked outside after a sermon, after Mass perhaps, they would be reminded right before they walk back into the world — the world of desire, the world of sin — that the sacrifice that Christ had made, that story that had unfolded in this chapel, comes down to decisions that they need to make in their own life.

[24:14] This is, in a sense, a kind of last reminder before you walk out to take these stories seriously.

Dr. Harris: [24:20] Giotto makes it very easy for us to do that by painting these figures in their humanity, by making the narrative so easy and clear to read, and by making something so beautiful, recognized for its beauty even when it was first painted.

Dr. Zucker: [24:37] That’s right. Even in its own day.

[24:39] [music]

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

We've begun to update our look on video and essay pages!

Smarthistory's video and essay pages look a little different but still work the same way. We're in the process of updating our look in small ways to make Smarthistory's content easy to read and accessible on all devices. You can now also collapse the sidebar for focused watching and reading, then open it back up to navigate. We'll be making more improvements to the site over the next few months!

Where next?

Explore related content

The Presentation of the Christ Child in the Temple

Giotto ca. 1320, isabella stewart gardner museum boston, united states.

- Title: The Presentation of the Christ Child in the Temple

- Creator: Giotto

- Creator Lifespan: 1267 - 1337

- Creator Nationality: Italian

- Creator Gender: M

- Date Created: ca. 1320

- Physical Dimensions: w43.6 x h45.2 cm

- Type: Paintings

- Rights: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Get the app

Explore museums and play with Art Transfer, Pocket Galleries, Art Selfie, and more

THE PRESENTATION OF THE CHRIST CHILD IN THE TEMPLE, ABOUT 1320

About the artwork.

At first glance the small painting of The Presentation of the Christ Child in the Temple looks like a self-contained object. It has a balanced composition: two pairs of standing figures flank a dainty ciborium that symbolizes the Temple of Jerusalem. Following the gospel of Luke, the artist has illustrated the dramatic moment when Simeon and the prophetess Anna recognize the Christ Child as the savior. Ever since the early nineteenth century, the Presentation has been known to be one of a series of seven paintings of the life of Christ (the others are in Munich, London, and New York). Although some scholars have questioned the traditional attribution of the series to Giotto, all the scenes are devised with such imagination and executed with such depth of feeling that only he could have painted them. There is nothing stereotyped about the compositions: each action is expressive, each face is individual. Thus, in the Presentation, the child struggles to get back in his mother’s arms. None of Giotto’s followers made such telling observations of human behavior. Source: Everett Fahy (1978), "The Presentation of the Christ Child in the Temple," in Eye of the Beholder , edited by Alan Chong et al. (Boston: ISGM and Beacon Press, 2003): 39

Related Images

About Our Products

Quality Gardner Museum Custom Prints is your exclusive source for custom reproductions authorized and available for purchase directly from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. All items that are offered are produced using gallery-quality materials and the color is managed in a manner that produces a reproduction as true to the original as modern technology will allow.

Selection Many of the works offered through this store are exclusive and not available anywhere else. In addition, new works are continually added to the offering, so come back often to see our new releases.

Customization You have found the work that speaks to you. Now what? Using our innovative custom framing tool, you can preview exactly what your finished and framed art will look like. We offer many different moulding styles so there is sure to be a match for any type of decor.

- About Gardner Museum Custom Prints

- Help & FAQs

- Contact Info

- Shopping Cart

- Back to gardnermuseum.org

- Go to Gift at the Gardner

- Plan Your Visit

- Event Schedule

- Music at the Gardner

- Contemporary Art at the Gardner

File : Giotto - Scrovegni - -19- - Presentation at the Temple.jpg

File history, file usage on commons, file usage on other wikis.

Giotto_-_Scrovegni_-_-19-_-_Presentation_at_the_Temple.jpg (492 × 500 pixels, file size: 91 KB, MIME type: image/jpeg )

Summary [ edit ]

- Virgin Mary

Structured data

Items portrayed in this file, presentation at the temple, digital representation of, main subject.

- 19. Presentation of Jesus at the Temple

- Artworks with Wikidata item

- Artworks digital representation of unknown type of work

- PD-Art (PD-old-100)

- PD US expired

Navigation menu

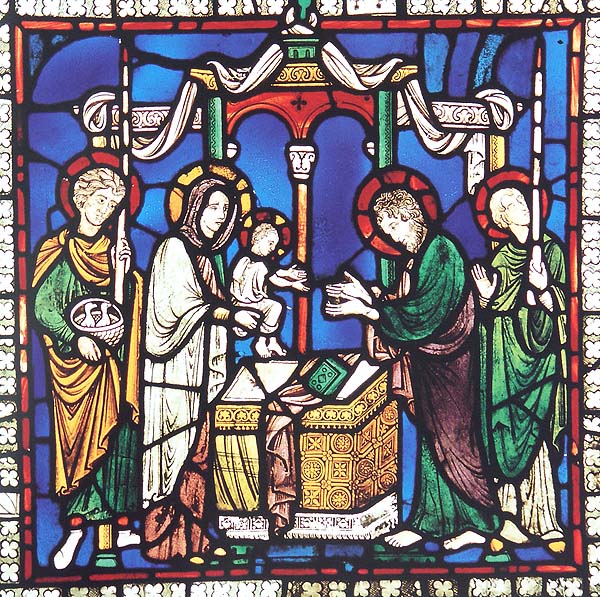

Widow’s Window to the Presentation: Prophetess Anna in the Temple

February 8, 2018 by Jessica Savage

Throughout the Middle Ages, the feast of the Presentation of Christ was observed on February 2 nd , where it gradually absorbed the rites of the Purification of the Virgin. [1] Incorporating blessed candles and certain songs, the feast came to be known as Candlemas . The only gospel writer to describe the Presentation of Christ in the Temple was Luke in the second chapter of his Gospel account (Luke 2:22–39). Luke writes that, in accordance with Jewish tradition, parents were required to bring an acceptable offering in exchange for the priest’s redemptive blessing on their child. Luke notes that “a pair of turtledoves, or two young pigeons” would fulfill the sacrifice (Luke 2:24). In Presentation scenes, the gathered doves, usually held by Joseph, signal Christ’s restoration under Mosaic Law. Over time, lit candles at this same ritual came to mark the Virgin’s cleansing and reentry into the temple. [2] In a stained-glass window in Canterbury Cathedral, we find Joseph holding both implements at the far left, a visual sign of the combined purpose of their visit (Figure 1).

When the Holy Family approaches the altar, Luke records two mystical occurrences that concern key witnesses in the temple. First, Simeon, the named priest from Jerusalem, prophesies the divinity of the Christ Child. [3] Another prophetic utterance comes from the lips of an unlikely source, the temple’s aged widow, Anna the prophetess. Luke tells us that Anna fasted and prayed there without ceasing. Anna is the New Testament’s only prophetess, and her privileged glimpse of the important ritual uniquely connects her to the childhood of Christ.

The Presentation is Anna’s one shining moment in the Gospels. In the Index of Medieval Art there are over 960 examples of the subject Christ: Presentation , and at least 330 include Anna as a secondary figure in the scene. We discover varied depictions of Anna in these medieval images. She is depicted as a scroll-bearing prophetess; as proxy to the presentation ritual, handling the different ritual items; or she may be simply shown among the other women surrounding the Virgin Mary. Despite her prominent role at the Presentation of Christ, Anna’s portrayal in medieval images can be perplexing. It seems medieval artists, who knew about her visionary role at the Presentation, could choose to emphasize or de-emphasize Anna as a prophetess based on tradition, context, or perhaps even their own interpretations of her significance. Several Presentation scenes also include a woman near the altar, and Indexers have often identified her as a female attendant, questioning her identity as the prophetess in iconographic descriptions. [4] Thus was born the usual Index reading of this female figure: “probably Anna.”

Because of the inconsistency of representations of the Presentation, it is not always easy to identify Anna in medieval images. Moreover, Luke’s account offers few details about her, other than that she is:

- the daughter of Phanuel of the tribe of Aser

- “far advanced in years”

- long widowed (for over 84 years)

- found in the temple, both day and night, fasting and praying

- one of the first testifiers of the divinity of Christ and declares it during the presentation (not elaborated further)

Analysis of Presentation scenes does reveal a few key details consistently associated with Anna: the presence of a halo; her scroll, which expounds her part in the prophecy; her interaction with presentation/purification implements, including the doves and candles; and her advanced age, sometimes suggested by her modest wimple. One or more of these details could be enough for a positive ID of our prophetess. Another sign is her speaking gesture, as in the Presentation miniature in the Romanesque Mont-Saint-Michel Sacramentary , in which Anna’s hands are shown outstretched in a wide statement of praise (Figure 2). This miniature also exemplifies an iconographic conundrum that sometimes accompanies Anna: a second nimbed and veiled female figure stands just behind Joseph, and she is carrying two doves in draped hands. Is this a second Anna? Or is this simply a sanctified female attendant? This female assistant is doing what many later Annas do in bearing the sacrificial birds, so the context with which we identify Anna becomes increasingly important.

Anna is one of the first people, even the first woman, to reveal Christ’s destiny, but her exact words are omitted from Luke’s account. We know that she “spoke of him to all that looked for the redemption of Israel” (Luke 2:38). However, since Anna’s actual words are not recorded, her scrolls present a number of different inscriptions. An Index search reveals some of the most intriguing ones. In the fifth-century sanctuary apse mosaic at Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, Anna’s scroll is inscribed BEATVS VENTER QVI TE PORTAVIT (Luke 11:27), meaning “Blessed is the womb that bore thee.” In a late twelfth-century mosaic in the Cathedral of Monreale, Anna holds a scroll inscribed POSIT(US) EST HIC I(N) RVINA(M) (Luke 2:34), repeating the words first said by Simeon, “This child is set for the fall.” In a fifteenth-century panel by the artist known as the “Byzantine Painter,” Anna holds a scroll inscribed (in Greek) “This child created Heaven and Earth” (Figure 3). And in one emotive declaration in a ca. 1240 Psalter from Hildesheim, Anna’s scroll is inscribed in Latin, EXULTATUIT COR MEUM (I Samuel, 02:01, also known as the Canticle of Anna ), meaning “My heart hath rejoiced” (Stuttgart, Landesbibliothek, Cod. Don. 309, fol. 37r).

Anna’s scroll has even been used to identify her by name, as in the presentation scene on the ca. 1365 Florentine Ashmolean Predella , from a private collection in Tuscany, with a scroll inscribed “ANNA PROFETESSA DEO GRATIAS AMEN” (“Prophetess Anna, Thanks be to God”). In this case, Anna’s index finger is elegantly lifted upward to indicate from whom her proselytizing originates. In other examples, Anna’s scroll can be completely blank, or filled with a pseudo-inscription. In the Armenian T’oros Roslin Gospels , the scroll expands into neat folds revealing simple red rulings (Figure 4).

The new advanced filter options offered by the Index database can reveal interesting trends within the Anna images recorded by the Index. I performed a keyword search for “Anna,” filtering by the subject Christ: Presentation , and restricted the search to fifteenth century examples (setting the date slider at 1400 to 1499). I limited these examples further with the Work of Art Type filter set to “Manuscript.” This way, I found over 60 records of interest describing fifteenth century illuminations that include this scene.

I narrowed these results further by adding a second subject filter with one of the Index’s grouped terms, Candle: held by Prophetess Anna . I found that, with each refinement, I was able to reconstruct Anna’s changing representation in medieval iconography. Curiously, in several of these late medieval examples, Anna is holding both a candle and a dove, and she is directly behind the Virgin Mary (not Simeon), displacing Joseph completely. These three-character scenes of the Presentation make up a good portion of later examples, and they underscore Anna’s union with the Holy Family’s first official appearance. In one such image, a fifteenth-century Book of Hours made in Paris, Anna is holding a candle in her right hand while playfully balancing a basket of birds on her head. A talented multitasker, Anna has, in a sense, usurped Joseph’s gift-bearing role (Figure 5).

No matter how she appears—as a wise widow bearing her scroll, or as a female witness bearing the implements of the impending ritual—the prophetess Anna is an exemplary New Testament woman. Through her time-honored vows of chastity, piety, and obedience to God, virtuous qualities brought out in her varied iconography, she presents a model of behavior for the young mother.

Further Reading

Shorr, Dorothy C. “The Iconographic Development of the Presentation in the Temple.” The Art Bulletin 28, no. 1 (1946): 17–32.

Schiller, Gertrud. Iconography of Christian Art , vol. 2, The Presentation of Christ in the Temple , trans. Janet Seligman (Greenwich, Conn.: New York Graphic Society, 1972): 90–94.

Elliott, J. K. “Anna’s Age (Luke 2:36–37).” Novum Testamentum , 30, Fasc. 2 (Apr., 1988), 100–102.

Hammond, Joseph. “Tintoretto and the ‘Presentation of Christ’: The Altar of the Purification in Santa Maria Dei Carmini, Venice.” Artibus Et Historiae 34, no. 68 (2013): 203–217.

“Presentation of the Christ Child in the Temple.” In The Oxford Dictionary of Christian Art & Architecture , edited by Murray, Peter, Linda Murray, and Tom Devonshire Jones: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Witherington III, Ben. “Mary, Simeon or Anna: Who First Recognized Jesus as Messiah.” Accessed 2 February 2018: https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-topics/new-testament/mary-simeon-or-anna-who-first-recognized-jesus-as-messiah/

[1] From at least the fourth century this ritual was celebrated as a post-purification feast, known as Hypapante , which Justinian set 40 days after the feast of the Epiphany, or on February 14.

[2] For the best study of the development of this iconography, see Dorothy C. Shorr, “The Iconographic Development of the Presentation in the Temple,” Art Bulletin 28 (1946): 20–46.

[3] Simeon holds the infant in his arms and instantly says to the Virgin Mary, “Behold this child is set for the fall, and for the resurrection of many in Israel…,” and representations of Simeon are associated with the text Nunc Dimittis , also known as the Canticle of Simeon (Luke 2:34–35).

[4] Shorr notes that, in most northern medieval examples after the thirteenth-century, Anna’s place was taken over by a young handmaiden (Shorr, 1946, p. 27).

The Database

Access the Database

Recent Posts

- Index Spotlight Series: Brooke Jurgenson

- Medieval Iconography of Pizzerias

- Kyriaki Giannouli Assists the Index with Mount Athos Backfiles

- Index Spotlight Series: Tinney Mak

- Call for Papers: “Unruly Iconographies? Examining the Unexpected in Medieval Art.”

Follow us on social media!

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- February 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- September 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

The Presentation of the Virgin (c. 1305) by Giotto

Note. This paper is an updated version (7/27/04) of a presention at the (Re)Discovering Aesthetics conference at University College, Cork on July 10, 2004.

Here are some examples of what I mean. Giotto's pictorial space, while undeniably more naturalistic than its precedents, is rife with inconsistencies:

1. Orthogonals and diagonals obey no consistent projection scheme; 2. Objects diminish ecccentrically with respect to distance; 3. Architectural impossibilities abound; 4. Perspectival and parallel projections are co-mingled.

The Expulsion of Joachim from the Temple exhibits 1, 2 and 4. The temple enclosure is presented in essentially parallel projection (click on the image to see the black diagonals on the diagram); the other diagonals converge, but to horizons on different elevations; and the pulpit is far too small for the indicated distance.

The Presentation of Mary in the Temple likewise exhibits 1and 2, and also 4. The architecture of the tower defies rationality, the near corner lacking any visible support.

3 . Giotto, The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple. Click on image for 4, the projection diagram.

My point in calling attention to these anomalies is not misplaced literalism. Rather it is grounded in aesthetic wonder. First in wonder at the fact that such features do not undermine the generally positive aesthetic effect of the works. That they do not is implied by the reception of the works both in Giotto's day and in ours. Secondly in wonder that so little curiosity is shown by commentators as to what precisely is the aesthetic effect of the inconsistencies, and why they have the effect they do. For there is practically no systematic (let me stress systematic ) discussion of the subject in the vast Giotto literature, so far as I have been able to find. Yet resolving those questions is plainly crucial to a deep understanding of Giotto's pictorial style. 4 .

Perhaps one reason for the neglect is that until recently it has been difficult to gauge the effect of isolated features. One can only try to imagine them away or compare the subject picture with other pictures differing in the relevant respect. Imagination is at once frail and capricious, and contrasting paintings never present an alternative "neat," that is to say, without other differences entering into the case. Fortunately recent advances in digital technology make it possible to create fully colored and textured reproductions of the works with selectively altered features. For instance, the diagonals in the Expulsion can be regularized and the result compared with that of the original. Likewise one can modify the other anomalous features of this and other Arena Chapel works, and thereby better take the measure of the originals. On this basis one can assess the artistic advantages and disadvantages of mingling projection schemes, erratically diminishing objects with distance, converging diagonals to different horizons, and various other spatial discrepancies or ambiguities. Operating with the new data, one finds oneself thrown into something like the position of the artist pondering practical problems - which are of course aesthetic problems - of how to manage the pictorial space within the various constraints applicable to the commission. In creating the transforms, one enters into the artist's project, attaining thereby a more intimate acquaintance with the art of art.

Such topics are particularly suited to a renewed interest in aesthetics in art history. For any given work we find an aesthetically rich and specific nest of problems concerning perceptions instead of generalities. We can form specific aesthetic questions and seek answers. The flood of new data generated by the transforms serves to sharpen the ultimate arbiter of matters aesthetic, namely the well-informed and well-practiced eye, as I hope to demonstrate through the following examples found in Giotto's work in the Chapel.

1. Projection-irregularities in the architectural setting.

Diagrams alert one to projection irregularities but do not enable one appreciate the aesthetic effect they produce. Digital transforms such as the following show what Giotto might, in principle, have done, and what the aesthetic effect of that would have been. The preliminary results are somewhat surprising.

5. Transform regularizing perspective of 1, keeping POV and size of forward figures unmodified.

The modified Joachim in the first transform calms down Giotto's hyperactive space - hyperactive in presenting multiple shifts of point of view. To be sure the regularized architectural structure is still far from realistic, since the pulpit is unaccountably reduced in size relative to the enclosure and the figures. But waiving that for the moment, by viewing the transform we are better positioned to appreciate the shift in aesthetic effect and address the question of what the artistic value of Giotto's invention is. Comparing the two we can ask how exactly the regularity of the transform affects us? What artistic good in the original is enhanced or degraded? Does the irregularity of the projection in the original take anything from it that Giotto or his contemporaries would have valued? Does it take anything away from what we value in Giotto?

The loss or gain, since aesthetic, must be expressed in terms of aesthetic properties. For instance it might be alleged that the scrambled projection makes for a more coherent surface design. Consider for example the felicitously balanced divergent slants of the base and pulpit in the original. That symmetry is virtually lost when the pulpit is nearly leveled. The upward slant of the pulpit in the original also widens the void into which Joachim is propelled by the censorious priest. Granted, a correct perspectival version can retain the slant, as in the next transform (6). Is this better? But this version produces a more aggressive rush out of depth by the entire structure, an effect not likely to meet with favor among Giotto cognoscenti, e.g, John White (5) .

6. Transform of 1 regularizing the perspective, preserving the upward tilt of the pulpit. POV nearer, forward figures enlarged accordingly.

The original may also conceivably be more expressive than either regularized alternative, perhaps conveying piety, which is plausibly a chief desideratum for Giotto, and for us too. Further, in its day Giotto's awkward composite was less at odds with the modes of spatial depiction it supplanted than are the regularized alternatives. Fully consistent perspective might have seemed too abrupt a shift, too dismissive of its immediate precedents. Or perhaps Giotto's mixed mode better reflects the less-than-merely-worldly character of the subject matter. Regardless of how one judges these suggestions it seems clear that the subject deserves to be explored instead of passed over, as it mostly has been all these years.

2. Misorientation of figures relative to the depicted context.

In the Presentation of Mary the figure of Anna is strikingly misorientated. She ascends a staircase lying at an angle of 30 degrees to what is called the picture plane. Yet she is orientated parallel to that plane. For her orientation to match that of the stairs, the stairs would have to be swiveled 30 degrees, as shown in the transform (7).

7. The stairs in 3 swiveled to conform to Mary's orientation.

(I have no transform regularizing her orientation in relation to the stairs in the original because I haven't felt equal to the task of redrawing her.) In this case I am fairly confident of one artistic good achieved - her orientation felicitously stresses the picture plane, helping to offset the diagonal placement of the architecture. If I am right about that advantage, what remaining questions are there about this (comparatively rare) feature? Does the orientation also have something to do with Anna's importance, signified also by her enhanced size? Or with the desire to show her face (to project that to the audience, as actors project their voice)? Unquestionably the orientation injects something artificial, unnaturalistic, into the depiction. Is that specific sort of artifice artistically good in itself, given the rest of the context?

3. Discrepancies of scale

Nothing is more obvious in the Arena Chapel pictures than the discrepancy of scale between the lower sections of the architecture, which are presented (more or less) full-size, and the upper ones, which are presented in miniature. The pulpit and staircase leading to it are disproportionately small. Why?

Left, 8. Transform of 3 with upper parts of the architecture heightened to lessen the discrepancy of scale. Right, 9. Transform of The Meeting at the Golden Gate to a similar effect.

It is not difficult to form reasonable hypotheses that contribute to an explanation of this. Here are some. The format was too small to permit the full height of structures to be shown without making the protagonists too small to be seen in detail from the available vantage points, or else without making the protagonists insufficiently commanding in the overall scene (the architecture upstaging the sacred event). These hazards can be gauged by enlarging the structure in The Presentation of Mary and The Meeting at the Golden Gate. The former now interestingly resembles Taddeo Gaddi's version of the same story in the Baroncelli Chapel of Santa Croce some twenty years later.

10. Left, Taddeo Gaddi (?), The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple. Drawing. Louvre. Right, 11, in which the perspective of 10is regularized.

Would the gain in naturalism of scale trump the figures' salience? Alternatively one may question why it was important for Giotto to show the full height of the structure, as opposed to the lower parts only 6 .

In the Expulsion Giotto could have lessened the discrepancy of scale by enlarging the pulpit. How well would this have worked? Here are two possibilities. The first enlarges the pulpit keeping the rest of the original as it is. (12) The second enlarges the pulpit with the perspective regularized as in 5 above. (13). In both cases to my eye the pulpit is now oppressive (though one could connect that with the theme!), too brutally so for Giotto, I believe. The transform by itself does not show whether this suspicion is correct, but it puts us in a better position to weigh the possibilities.

21. Transform of 1 with pulpit enlarged and the rest as it was. Click on image for 13, transform of 5 with pulpit enlarged.

Of course there is much more to the visual experience of the discrepant scale than has been so far suggested. First there is the obvious link between size and distance. Secondly there is the perceptual circumstance that when we focus on the figures the miniaturized parts of the structure usually fall into the periphery of our field of vision. And in reverse, focusing on the miniaturized parts throws the figures into the periphery. Since the discrepancy of scale normally and necessarily suggests a difference of distance, and since the eye seeks consistency wherever it can be imposed, even at the cost of ignoring plain facts, the miniaturized parts of the structure are readily able to be seen, in passing, as farther off than is consistent with their connections with parts in the foreground. Those connections can be momentarily suppressed, just as can the presence of the outsized figures as they move into the periphery when one focuses upon the miniaturized parts.

In fact, something of the same visual abstraction is normal in the phenomenology of attention. When we attend to the figures rather than the architecture we can partially suppress the data concerning the architecture even when both fall within the same region of our visual field.

The viewer's use of a shifting focus and selective attention seems to work quite well as long as the distant parts can be taken as mere setting, without figural involvement. But place a figure in the pulpit in either of these pictures and the inconsistency becomes jarring, incapable of being suppressed, as is shown, I think, by the next transform (14). Giotto regularly avoids doing this. That makes it look as if the artist consciously or preconsciously counts on our use of a shifting focus (ocularly or attention-wise) and that his pictures gain in overall naturalistic effect from the engaged viewer spontaneously adopting this tactic in the course of sustained study of the works.

14. Transform of 1 with appropriately sized figure in the pulpit.

The aesthetic possibilities here, familiar to us because exploited by Cézanne and the cubists in modern times, deserve to be explored.

4. Giotto's worm's eye horizon In the Arena pictures Giotto uses an impossibly low topographical horizon whenever such a horizon is visible, as it is in The Meeting at the Golden Gate.

15. Giotto, The Meeting of Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gate.

The same low horizon-like division of ground and backdrop is found in The Expulsion of Joachim . This immediately raises two questions relating to the latter. What is the literal reference of the blue background? It looks for all the world like sky, which its counterpart in the Meeting certainly is. Yet how can it be, with the edge of the ground so low? In both pictures the figures and the perspectival elements in the architecture imply a topographical horizon not lower than the midriffs of the figures. And if we must take the blue in the Expulsion to be an interior surface, following Paul Hills' 7 reading of the space as interior, based on the structures being interior ones, ciborium and pulpit as for instance in San Clemente , how can the base of the wall come so low? In fact it would slice across the enclosure! Why does Giotto favor such an anomaly? In this case the blue expanse may gain, as several commentators say, the thematic significance of an emotional void into which Joachim is propelled by the rejection of his offering, but Giotto's choice of a worm's eye view is by no means restricted to contexts where a specialized theme operates, as its presence in the Meeting shows. So it is relevant to search for an explanation based on the spatial effect alone.

Such a one is suggested if we compare the horizon in The Meeting at the Golden Gate with a transform that raises the horizon to accord with the dominant figural and architectural indications.

16. Transform of 15 with topographical horizon raised to suit the level of the figures and most architectural indications.

The transform incorporating this horizon shows how diminished the city walls become, and how uncomfortably sunk in the landscape they are. A similar aesthetic effect would result from raising the topographical horizon in the perspectival regularized Expulsion , as is shown by the corresponding transform of 5 -- placing the scene outside, that is. (17) I have not attempted to produce a viable interior background, where the problem of scale would be formidable.

17. Transform of 5 with topographical horizon made consistent with the perspective.

What I suggest is that a sufficient reason for the abnormally low horizon (or horizon-like division) is that it restores to the miniaturized upper architectural features much of their proper stature. And even more basically, it allows the foreground motifs to breathe by placing them against a void rather than against a receding ground.

5. Integration of individual spaces on the wall

Quite apart from questions about the coherence of the pictorial space within a given picture are issues relating to the optimum arrangement of motifs in pictures in relation to others on the wall. On the east or choir wall in the Arena we find a fascinating medley of arrangements (Fig. 18).

Left, 18 . Giotto, the Arena Chapel east wall, with the color partly restored. Right, 19, transform of 18 flipping the Visitation .

On the second tier are the two fictive alcoves or chapels ( coretti ) that continue the space of the actual chapel. On the fourth tier at the springing of the arch is the Annunciation , in which Gabriel and Mary occupy buildings on either side of the arch that mirror each other. The orthogonals of these structures recede symmetrically in opposite directions to vanishing points (fictively) lying far outside the Chapel to right and left, thus forming two disjoint spaces. The effect, however, is to make the buildings seem turned toward each other, that is, toward the center of the wall. The orthogonals of the fictive chapels converge toward the altar, thus in exact opposition to those of the buildings of the Annunciation. They form one space rather than two. On the third tier are Judas receiving the 30 talents (left) and the Visitation (right), in both of which the placement of the diagonally positioned architectural structures suggests a recession to the right -- thus contrasting with the symmetry of the tiers directly above and below. Anyone sensitive to the aesthetics of formal arrangement must wonder whether Giotto's management of these arrangements is the optimal one. If it is the best, then why is it so? Only a close study of the four available options, which are but child's play to produce by digital transformation (19-21), can provide us with a well-founded aesthetic judgment. I will return to questions of this sort in the last section of the paper, 'Second-guessing Giotto.'

Left, 20. Transform of 18 flipping both the Visitation and Judas receiving the 30 Talents.Right, 21. Transform of 18 with only the Judas flipped.

6. Ambiguities of protrusion/recession

The oddity of the house-to-house Annunciation raises a number of questions. Taken literally it is most curious, since it represents the holy transaction as linking matching buildings on opposite sides of a street. That already strains credulity. Much odder is the fact that the structures are presented from widely different points of view, the left one from off-stage left and the right one from off-stage right. This has been noted in the literature 8 , although sometimes with suggestions 9 that the structures as angled toward each other , which they are not, since their fronts lie parallel to the picture plane. A third and quite striking effect of the whole is the seeming protrusion of the balconies into the space of the Chapel, which all observers note with approval and admiration. Let us consider these traits in turn.

The most basic feature of the design, the use of matching structures and intervening space, has perhaps been deemed too obviously salutary to require comment 10 . It seems patent that on a formal level, matching structures are virtually a necessity. How else could the two columns of images be closed off so as to supply a uniform base for the heaven above? Given that Gabriel's annunciation to Mary is to be accommodated in this space, just below the dispatch of the angel on his mission, and given the required size of figures in relation to the available space, both structures must be employed, a consideration which is also consonant with the importance of the event and with the Chapel-wide scene above it. Further, given that Gabriel must be on the left in order to continue the narrative on the walls, placing the Virgin on the right allows God's fructifying radiance to fall in a direct line upon her as the announcement of the event is conveyed laterally from the left by His angelic agent. It also places the Virgin next to the continuation of her narrative on the right wall. These considerations understandably might trump naturalism of the mise en scène . This brings us to the (merely apparent) opposition of orientation of the structures. We find two explanations in the literature. First the angled forms of the design felicitously fill the available space between the curves of the two arches with the least possible occlusion by the outside arch 11 . Secondly the design is said to induce the eye to glide more easily from side to side, intensifying the effect of transmitted messages 12 . These are intuitively plausible, but need confirmation or correction by examination of the alternatives which cancel the opposition. For example, would the gazes of Gabriel and Mary be "hemmed in by the jutting balconies" but for the angled rendering, as White 13 surmises? A transform such as 22 can put this to the test. (For an enlargement of 22, click on the image and obtain 23.)

Left, 22. Transform of 18 with balconies of the Annunciation presented strictly frontally. Right, 18. The original repeated. Click on image to obtain 23, an enlargement of the top two registers of 22.

Finally, the apparent protrusion of the balconies into the real space of the chapel injects a quite separate dynamism into the whole. This effect, it should be noted, is not required by the drawing - indeed the drawing itself is evenly balanced between contradictions - but visually it is an irresistible "moment" of the design. That is, most though not all of our ocular fixations will contain an impression of protrusion. We are not likely to notice the distance cues that are inconsistent with this effect, most notably the fact that the curve of the outer (painted) arch passes in front of the foremost part of the roofs on both sides, as it could not do if the balconies extended beyond that arch. One commentator 14 proposes that the protrusion as a graphic symbol of the intrusion into the world of the deity in the miraculous conception. Perhaps there is merit in this, but it may also be doubted on the basis of there being no general practice in Giotto of symbolizing divine intrusions this way. And in terms of spatial illusion alone, is the protrusion of the balconies really more convincing to the eye than consistent recession would be?

These problems and hypotheses can be addressed more acutely by studying the alternatives to Giotto's image. The first (22 and 23) presents fully frontal views of the two buildings, the second (24) lessens the ambiguity of depth by providing a clear indication of ground lying in front of the base of the buildings, and the third (25) does the same for the frontal version of the scene.

24. Transform lessening the spatial ambiguity of the right side building of the Annunciation. Click on the image for 25, which does the same for the frontal version of the balconies (22 and 23).

Merely comparing the alternatives with the original does not of course automatically answer the questions of meaning and intention. But surely it provides the eye with more data to draw upon in forming, and testing, one's interpretations.

Giotto's fictive protrusions and recessions, consistent and inconsistent alike, in the Arena works are pervasively tantalizing, as we can appreciate if we study closely the upper section of the same wall. Fixate on the steps leading to the enthroned Christ and it is easy to feel the whole throne drift out into the viewer's space. (26) The sky offers no tangible assurance of its lying behind the arch or even behind the balconies of the Annunciation structures, although the crowd of angels on each side of the throne tends to restrain its protrusion when the shifting eye takes them into account.

26. Giotto, East wall of the Arena Chapel with color partly restored (detail). Click on the image for 23, the frontal view of the buildings.

Indeed, the more one dwells on the works the more equivocations one finds. Consider for instance the tendency of the inner band of the outer (painted) arch, as it rises beyond the Annunciation , to become an inner surface of a three-dimensional structure comparable to the actual triumphal arch. The constant shifting of the fictive forms seems to be an essential part of Giotto's appeal, forming a counterpoise to the much acclaimed, classic repose of the monumental figures 15 .

7. Second-guessing Giotto

I have already posed questions concerning the aesthetic merit of Giotto's designs compared with that of alternatives. Here is a set of four options for The Presentation of Mary in the Temple : the original, a perspectival regularization to each of the two suggested horizons (27-28 ), and a partial ameliorization of the inconsistency of the original by leveling the porch of the structure, leaving all else the same (29).

Left. 3. Giotto, The Presentation of the Virgin at the Temple . Right. 27. Transform regularizing the perspective in 3 to the height of the figures and the indications given by the upper architecture.

Left. 28. Transform regularizing perspective of 3 to the horizon implied by the lower architecture. Right. 29. Minimal lessening of projection inconsistency by leveling porch floor, leaving the rest unchanged.

For my own part, I think Giotto would earn higher marks had he chosen the last (29). Anyone who prefers the original has the task of explaining why the downwardly sloping porch floor is a positive attribute within Giotto's own parameters. Any suggestions?

And finally I offer an arguably better alternative to Giotto's The Meeting of Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gate (30). Its space is far from consistent, since the wrenching discrepancy of ground level on the two sides of the bridge is not set right, nor is there any good way to do so. But much in the original has been regularized without loss of drama or grandeur. Can Giotto's original really be aesthetically superior to the transform, even within his parameters? Here is a nice problem for Giotto cognoscenti to ponder.

Left , 15. Giotto, The Meeting of Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gate. Right, 30. Transform of 15 regularizing the perspective to the lowest feasible horizon.

Throughout the foregoing reflections my main purpose has not been to gain your agreement on particular matters of interpretation and assessment, but only to pose unsolved aesthetic problems as eminently worthy of serious attention. In proposing that the enlightening potential of the additional data provided by the transforms be utilized my plea is simply this: How else can we ever do full justice to the myriad details of Giotto's artistic practice?

My general theme is thus the need for a reinvigorated address to aesthetic problems posed even by paintings that one may think have been exhaustively analyzed. Here, surely, is a down-to-earth way in which rediscovering aesthetics can produce tangible good in art history.

1 . John White, Birth and Rebirth of Pictorial Space (1957, 1967,1987) and Art and Architecture in Italy 1250-1400 (1966), Ch. 24.

2 . Alastair Smart, The Assisi Problem and the Art of Giotto (1971), Ch. IV.

3 . James H. Stubblebine, Assisi and the Rise of Vernacular Art (1985).

4 . I do not deny that the literature contains many illuminating comments about particular anomalies. On a larger scale there is a challenging explanation of the scrambling of modes, horizons, etc. in James Elkins' The Poetics of Perspective (1994) namely that painters at the time conceived of space in terms of individual objects rather than the spatial manifold as a whole. I find this thesis partly true and yet inadequate because it posits too radical a breach between inseparables. To produce any pictorial space the relations among objects must be set forth. Hence an overall spatial effect is necessarily produced. For Giotto and for us his pictorial spaces must register as somewhat strange and problematic wholes because of the inconsistencies.

5 . White, op. cit.