An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Impact of COVID-19 on the social, economic, environmental and energy domains: Lessons learnt from a global pandemic

a School of Information Systems and Modelling, Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, University of Technology Sydney, NSW 2007, Australia

I.M. Rizwanul Fattah

Md asraful alam.

b School of Chemical Engineering, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou 450001, China

A.B.M. Saiful Islam

c Department of Civil and Construction Engineering, College of Engineering, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam 31451, Saudi Arabia

Hwai Chyuan Ong

S.m. ashrafur rahman.

d Biofuel Engine Research Facility, Queensland University of Technology (QUT), Brisbane, QLD 4000, Australia

e Tarbiat Modares University, P.O.Box: 14115-111, Tehran, Iran

f Science and Math Program, Asian University for Women, Chattogram 4000, Bangladesh

Md. Alhaz Uddin

g Department of Civil Engineering, College of Engineering, Jouf University, Sakaka, Saudi Arabia

T.M.I. Mahlia

COVID-19 has heightened human suffering, undermined the economy, turned the lives of billions of people around the globe upside down, and significantly affected the health, economic, environmental and social domains. This study aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on the ecological domain, the energy sector, society and the economy and investigate the global preventive measures taken to reduce the transmission of COVID-19. This analysis unpacks the key responses to COVID-19, the efficacy of current initiatives, and summarises the lessons learnt as an update on the information available to authorities, business and industry. This review found that a 72-hour delay in the collection and disposal of waste from infected households and quarantine facilities is crucial to controlling the spread of the virus. Broad sector by sector plans for socio-economic growth as well as a robust entrepreneurship-friendly economy is needed for the business to be sustainable at the peak of the pandemic. The socio-economic crisis has reshaped investment in energy and affected the energy sector significantly with most investment activity facing disruption due to mobility restrictions. Delays in energy projects are expected to create uncertainty in the years ahead. This report will benefit governments, leaders, energy firms and customers in addressing a pandemic-like situation in the future.

1. Introduction

The newly identified infectious coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) was discovered in Wuhan and has spread rapidly since December 2019 within China and to other countries around the globe ( Zhou et al., 2020 ; Kabir et al., 2020 ). The source of SARS-CoV-2 is still unclear ( Gorbalenya et al., 2020 ). Fig. 1 demonstrates the initial timeline of the development of SARS-CoV-2 ( Yan et al., 2020 ). The COVID-19 pandemic has posed significant challenges to global safety in public health ( Wang et al., 2020 ). On 31 st January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO), due to growing fears about the rapid spread of coronavirus, announced a global epidemic and on 11 th March, the disease was recognised as a pandemic ( Chowdhury et al., 2021 ). COVID-19 clinical trials indicate that almost all patients admitted to hospital have trouble breathing and pneumonia-like symptoms ( Holshue et al., 2020 ). Clinical diagnosis has identified that COVID-19 (disease caused by SARS-CoV-2) patients have similar indications to other coronavirus affected patients, e.g. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) ( Wang and Su, 2020 ). The initial indication of a COVID-19 infection is coughing, fever, and short breath, and in the later stages, it can damage the kidney, cause pneumonia, and unexpected death ( Mofijur et al., 2020 ). The vulnerability of the elderly (>80 years of age) is high, with a fatality rate of ~22% of cases infected by COVID-19 ( Abdullah et al., 2020 ). The total number of confirmed COVID-19 cases has reached over 33 million as of 29 th September 2020, with more than 213 countries and regions affected by the pandemic ( Worldometer, 2020 ). Over 1,003,569 people have already passed away ( Worldometer, 2020 ) due to COVID-19. Most countries are currently trying to combat the virus spread by screening for COVID-19 in large numbers and maintaining social distancing policies with an emphasis on the health of human beings.

The initial stage development timeline for COVID-19 ( Yan et al., 2020 ).

Fig. 2 shows infections and replication cycle of the coronavirus. In extreme cases, the lungs are the most severely damaged organ of a SARS-CoV-2 infected person (host). The alveoli are porous cup-formed small cavities located in the structure of the lungs where the gas exchange of the breathing process take place. The most common cells on the alveoli are the type II cells.

Infections and replication cycle of the coronavirus ( Acter et al., 2020 ).

It has been reported that travel restrictions play a significant role in controlling the initial spread of COVID-19 ( Chinazzi et al., 2020 ; Aldila et al., 2020 ; Beck and Hensher, 2020 ; Bruinen de Bruin et al., 2020 ; de Haas et al., 2020 ). It has been reported that staying at home is most useful in controlling both the initial and last phase of infectious diseases ( de Haas et al., 2020 ; Cohen, 2020 , Pirouz et al., 2020 ). However, since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, quarantines, entry bans, as well as other limitations have been implemented for citizens in or recent travellers to several countries in the most affected areas ( Sohrabi et al., 2020 ). Also, most of the industries were shutdown to lower mobility. A potential benefit of these measures is the reduction of pollution by the industrial and transportation sector, improving urban sustainability ( Jiang et al., 2021 ). Fig. 3 shows the global responses to lower the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak. There have been negative economic and social implications due to restrictions and decreased travel readiness worldwide ( Leal Filho et al., 2020 ). A fall in the volume of business activity and international events and an increase in online measures could have a long-term impact. The status of global transport and air activity as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic is shown in Fig. 4 ( International Energy Agency (IEA), 2020 ). By March 2020, the average global road haulage activity in regions with lockdowns had declined to almost 50% of the 2019 standard. Air travel has almost completely stopped in certain regions with aviation activity decreasing by over 90% in some European countries. Air activity in China recovered slightly from a low in late February, with lockdown measures somewhat eased. Nevertheless, as lockdowns spread, by the end of Q1 2020, global aviation activity decreased by a staggering 60%.

Initial preventive measures to lower the COVID-19 outbreak ( Bruinen de Bruin et al., 2020 ).

Global transport and aviation activity in the first quarter of the year 2020 ( International Energy Agency (IEA), 2020 ).

The spread of COVID-19 continues to threaten the public health situation severely ( Chinazzi et al., 2020 ) and greatly affect the global economy. Labour displacement, business closures and stock crashes are just some of the impacts of this global lockdown during the pandemic. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the effect of COVID-19 will result in a worldwide economic decline in 2020 and a decline in the economic growth to 3% ( International Monetary Fund (IMF) ). COVID-19 has a detrimental impact on economic growth due to two primary factors. In the beginning, the exponential growth of the global epidemic directly contributed to considerable confusion about instability in the financial and capital markets. Secondly, countries have strictly regulated human movement and transport to monitor the growth of the epidemic and significantly reduced economic activity, putting pressure on both consumer and productive economic activity.

Since the 1970s, the link between economic growth and pollution has been an important global concern. The assessment of energy and financial efficiency is usually connected to environmental pollution research. Green practices at a national level, the inclusion of renewable energy, regulatory pressure and the sustainable use of natural resources are associated with environmental sustainability ( Khan et al., 2020 ). One study has shown that environmental pollution increases with economic growth and vice versa ( Cai et al., 2020 ). The strict control over movement and business activity due to COVID-19 has led to an economic downturn, which is in turn, expected to reduce environmental pollution. This paper systematically assesses how the novel coronavirus has had a global effect on society, the energy sector and the environment. This study presents data compiled from the literature, news sources and reports (from February 2020 to July 2020) on the management steps implemented across the globe to control and reduce the impact of COVID-19. The study will offer guidelines for nations to assess the overall impact of COVID-19 in their countries.

2. Impact of COVID-19 on the environmental domain

2.1. waste generation.

The generation of different types of waste indirectly creates a number of environmental concerns ( Schanes et al., 2018 ). The home isolation and pop-up confinement services in countries that have experienced major impacts of COVID-19 are standard practise, as hospitals are given priority to the most serious cases. In some countries, hotels are being used to isolate travellers for at least two weeks on entry. In several countries, such quarantine measures have resulted in consumers increasing their domestic online shopping activity that has increased domestic waste. In addition, food bought online is packaged, so inorganic waste has also increased. Medical waste has also increased. For instance, Wuhan hospitals produced an average of 240 metric tonnes of medical waste during the outbreak compared to their previous average of fewer than 50 tonnes ( Zambrano-Monserrate et al., 2020 ). This unusual situation poses new and major obstacles in the implementation of waste collection services, thus creating a new challenge for waste collection and recycling groups. With the global adaptation to exponential behavioural and social shifts in the face of COVID-19 challenges, municipal services such as waste collection and management need to alter their operations to play an important role in reducing the spread of infectious diseases.

2.1.1. Lifespan of COVID-19 on different waste media

SARS-CoV-2′s transmission activity has major repercussions for waste services. SARS-CoV-2 attacks host cells with ACE2 proteins directly. ACE2 is a cell membrane-associated enzyme in the lungs, heart and kidneys. When all the resources in the host cell are infected and depleted, the viruses leave the cell in the so-called shedding cycle ( Nghiem et al., 2020 ). Clinical and virological evidence suggests that the elimination of the SARS-CoV-2 virus is most relevant early on, right before and within a couple of days of the onset of the illness ( AEMO, 2020 ). Fomites are known as major vectors for the replication of other infectious viruses during the outbreak ( Park et al., 2015 ). Evidence from SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses show that they remain effective for up to a few days in the atmosphere and on a variety of surfaces ( Fig. 5 ). The survival time of SARS-CoV-2 on hard and plastic surfaces is up to three days indicating that waste materials from COVID-19 patients may contain coronavirus and be a source of infection spread ( Chin et al., 2020 ). During the early stages of this epidemic, updated waste disposal methods to tackle COVID-19 were not implemented on the broader community. The concept of clinical waste essentially also applies to waste from contaminated homes and quarantine facilities. Throughout this pandemic, huge volumes of domestic and hospital waste, particularly plastic waste, has been generated. This has already impeded current efforts to reduce plastic waste and decrease its disposal in the environment. More effort should be made to find alternatives to heavily used plastics.

The lifespan of SARS-CoV-2 on different media ( Chin et al., 2020 ; van Doremalen et al.; 2020 ; Ye et al., 2016 )

2.1.2. Waste recycling service

COVID-19 has already had significant effects on waste recycling. Initially, as the outbreak spread and lockdowns were implemented in several countries, both public authorities and municipal waste management officials had to adjust to the situation quickly. Waste disposal has also been a major environmental problem for all technologically advanced nations, as no clear information was available about the retention time of SARS-CoV-2 ( Liu et al., 2020 ). Recycling is a growing and efficient means of pollution control, saving energy and conserving natural resources ( Ma et al., 2019 ). Recycling projects in various cities have been put on hold due to the pandemic, with officials worried about the possibility of COVID-19 spreading to recycling centres. Waste management has been limited in affected European countries. For example, Italy prohibited the sorting of waste by infected citizens. Extensive waste management during the pandemic is incredibly difficult because of the scattered nature of the cases and the individuals affected. The value of implementing best management practises for waste handling and hygiene to minimise employee exposure to potentially hazardous waste, should be highlighted at this time. Considering the possible role of the environment in the spread of SARS-CoV-2 ( Qu et al., 2020 ), the processing of both household and quarantine facility waste is a crucial point of control. Association of Cities and Regions for sustainable Resource management (ACR+) has reported on the provision of separate collection services to COVID-19 contaminated households and quarantine facilities to protect frontline waste workers in Europe, as shown in Fig. 6 . ACR+ also suggests a 72-hour delay in waste disposal (the possible lifespan of COVID-19 in the environment) ( Nghiem et al., 2020 ). Moreover, the collected waste should be immediately transported to waste incinerators or sites without segregation.

Recommended waste management during COVID-19 ( ACR+ 2020 ).

2.2. NO 2 emissions

Without the global pandemic, we had naively anticipated that in 2020 global emissions would rise by around 1% on a five-year basis. Instead, the sharp decline in economic activity in response to the current crisis will most probably lead to a modest drop in global greenhouse emissions. The European Space Agency (ESA), with its head office in Paris, France, is an intergovernmental body made up of 22 European countries committed to exploring the international space. To monitor air pollution in the atmosphere, the ESA uses the Copernicus Sentinel-5P Satellite. In addition to the compound contents measurement, the Copernicus Sentinel-5P troposphere monitor (TROPOMI) and other specified precision equipment measure ozone content, sulphur dioxide, carbon monoxide, and methane. Table 1 shows NO 2 emissions data acquisition by ESA using Sentinel-5P across different regions of Europe ( Financial Times, 2020 ).

NO 2 emissions data acquisition by ESA using Sentinel-5P across different regions of Europe ( Financial Times, 2020 ).

Burning fossil fuels, such as coal, oil, gas and other fuels, is the source of atmospheric nitrogen dioxide ( Munawer, 2018 ). The bulk of the NO 2 in cities, however, comes from emissions from motor vehicles (approximately 80%). Other NO 2 sources include petroleum and metal refining, coal-fired electricity, other manufacturing and food processing industries. Some NO 2 is naturally produced by lightning in the atmosphere and from the soil, water, and plants, which, taken together, constitutes not even 1% of the total NO 2 found in the air of our localities. Due to pollution variations as well as changes in weather conditions, the levels of the NO 2 in our atmosphere differ widely every day. Anthropogenic pollution is estimated to contain around 53 million tonnes of NO 2 annually. Nitrogen dioxide, together with nitrogen oxide (NO), are considered the major components of oxides of nitrogen (NOx) ( M Palash et al., 2013 ; Fattah et al., 2013 ). NO, and NO 2 are susceptible to other chemicals and form acid rain that is toxic to the environment ( Mofijur et al., 2013 ; Ashraful et al., 2014 ), WHO lists NO 2 as one of the six typical air contaminants in the atmosphere. For this reason, the amount of NO 2 in the atmosphere is used as a precise measure for determining whether the COVID-19 outbreak affects environmental pollution.

NO 2 is an irritating reddish-brown gas with an unpleasant smell, and when cooled or compressed, it becomes a yellowish-brown liquid ( Wang and Su, 2020 ). NO 2 inflames the lung linings and can decrease lung infection immunity. High levels of NO 2 in the air we breathe can corrode our body's lung tissues . Nitrogen dioxide is a problematic air pollutant because it leads to brown photochemical smog formation, which can have significant impacts on human health ( Huang et al., 2020 ). Brief exposure to high concentrations of NO 2 can lead to respiratory symptoms such as coughing, wheezing, bronchitis, flu, etc., and aggravate respiratory illnesses such as asthma. Increased NO 2 levels can have major effects on individuals with asthma, sometimes leading to frequent and intense attacks ( Munawer, 2018 ). Asthmatic children and older individuals with cardiac illness are most vulnerable in this regard. However, its main drawback is that it produces two of the most harmful air pollutants, ozone and airborne particles. Ozone gas affects our lungs and the crops we eat.

2.2.1. NO₂ emissions across different countries

According to the ESA ( European Space Agency (ESA), 2020 ), average levels of NO 2 declined by 40% between 13 th March 2020 to 13 th April 2020. The reduction was 55% compared to the same period in 2019. Fig. 7 compares the 2019-2020 NO 2 concentration ( European Space Agency (ESA), 2020 ). The displayed satellite image was captured with the TROPOMI by ESA satellite Sentinel-5P. The percentage reductions in average NO 2 emissions in European countries during the COVID-19 outbreak from 1 st April to 30 th April 2020 can be seen in Fig. 8 ( Myllyvirta, 2020 ). Portugal, Spain, Norway, Croatia, France, Italy, and Finland are the countries that experienced the largest decrease in NO 2 levels, with 58%, 48%, 47%, 43% and 41%, respectively.

Comparison of the NO 2 concentration between 2019 and 2020 in Europe ( European Space Agency (ESA), 2020 ).

Changes in average NO 2 emission in different countries ( Myllyvirta, 2020 ).

The average 10-day animation of NO 2 emissions throughout Europe (from 1 st January to 11 th March 2020), demonstrated the environmental impact of Italy's economic downturn, see Fig. 9 ( European Space Agency (ESA), 2020 ). In the recent four weeks (Last week of February 2020 to the third week of March 2020) the average concentration of NO 2 in Milan, Italy, has been at least 24% less than the previous four weeks. In the week of 16 – 22 March, the average concentration was 21% lower than in 2019 for the same week. Over the last four weeks of January 2020, NO 2 emissions in Bergamo city has been gradually declining. During the week of 16–22 March, the average concentration was 47% less than in 2019. In Rome, NO 2 rates were 26–35% lower than average in the last four weeks (third week of January 2020 to the third week of February 2020) than they were during the same week of 2019 ( Atmosphere Monitoring Service, 2020 ).

Changes of NO 2 emission (a) over entire Italy (b) capital city (c) other cities ( European Space Agency (ESA), 2020 ; Atmosphere Monitoring Service, 2020 ).

Fig. 10 shows a comparison of NO 2 volumes in Spain in March 2019 and 2020. As per ( European Space Agency (ESA), 2020 ), Spain's NO 2 pollutants decreased by up to 20–30% due to lockdown, particularly across big cities like Madrid, Barcelona, and Seville. ESA Sentinel-5P captured the satellite image using TROPOMI. Satellite images of the 10 days between 14 th and 25 th March 2020 show that NO 2 tropospheric concentration in the areas of Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, and Murcia ranges from 0–90 mg/m 3 . The NO 2 tropospheric concentration for Seville is almost 0 mg/m 3 for the same time. For March 2019, the average NO 2 tropospheric concentration for the Madrid area was between 90 and 160 mg/m 3 . At the same time, the range of NO 2 tropospheric concentration for Barcelona, Valencia, and Seville area was between 90–140 mg/m 3 , 90-130 mg/m 3 , and 30–50 mg/m 3 , respectively.

Comparison between before and after lockdown NO 2 emissions in Spain ( European Space Agency (ESA), 2020 ).

Fig. 11 shows the reduction in the amount of NO 2 emissions in France in March 2019 and 2020 ( European Space Agency (ESA), 2020 ). In France, levels of NO 2 have been reduced by 20% to 30%. The ESA Sentinel-5P satellite image was captured with the TROPOMI. In Paris and other major cities, the emission levels of NO 2 considerably lowered due to lockdown. The three major areas of France where NO 2 tropospheric concentration was significant are Paris, Lyon, Marseille and their surroundings. Satellite images of the ten days between 14 th and 25 th March 2020 show that NO 2 tropospheric concentration of the Paris, Lyon, Marseille areas ranges 30–90 mg/m 3 , 20–40 mg/m 3 and 40–80 mg/m 3 , respectively. For March 2019, the average NO 2 tropospheric concentration for the same areas was reported as 100–160 mg/m 3 , 30–60 mg/m 3, and 90–140 mg/m 3 , respectively.

Comparison of NO 2 emissions in France before and after lockdown ( European Space Agency (ESA), 2020 ).

Various industries across the UK have been affected by COVID-19, which has influenced air contamination. As shown in Fig. 12 , there were notable drops in the country's NO 2 emissions on the first day of quarantine ( Khoo, 2020 ). Edinburgh showed the most significant reduction. The average NO 2 emissions on 26 th March 2020, were 28 μg/m 3 while on the same day of 2019, this was 74 μg/m 3 ( Khoo, 2020 ). The second biggest reduction was observed in London Westminster where emissions reduced from 58 µg/m 3 to 30 µg/m 3 . Not all cities have seen such a significant decrease, with daily air pollution reducing by 7 μg/m 3 compared to the previous year in Manchester Piccadilly, for example ( Statista, 2020 ).

(a) Changes in NO 2 emissions in the UK during lockdown ( European Space Agency (ESA), 2020 ); (b) comparison of NO 2 emissions in 2019 and 2020 ( Khoo, 2020 ).

2.3. PM emission

The term particulate matter, referred to as PM, is used to identify tiny airborne particles. PM forms in the atmosphere when pollutants chemically react with each other. Particles include pollution, dirt, soot, smoke, and droplets. Pollutants emitted from vehicles, factories, building sites, tilled areas, unpaved roads and the burning of fossil fuels also contribute to PM in the air ( Baensch-Baltruschat et al., 2020 ). Grilling food (by burning leaves or gas grills), smoking cigarettes, and burning wood on a fireplace or stove also contribute to PM. The aerodynamic diameter is considered a simple way to describe PM's particle size as these particles occur in various shapes and densities. Particulates are usually divided into two categories, namely, PM 10 that are inhalable particles with a diameter of 10 μm or less and PM 2.5 which are fine inhalable particle with a diameter of 2.5 μm or less. PM 2.5 exposure causes relatively severe health problems such as non-fatal heart attacks, heartbeat irregularity, increased asthma, reduced lung function, heightened respiratory symptoms, and premature death ( Weitekamp et al., 2020 ).

PM 2.5 also poses a threat to the environment, including lower visibility (haze) in many parts of the globe. Particulates can be transported long distances then settle on the ground or in water sources. In these contexts and as a function of the chemical composition, PM 2.5 may cause acidity in lakes and stream water, alter the nutrient balance in coastal waters and basins, deplete soil nutrients and damage crops on farms, affect the biodiversity in the ecosystem, and contribute to acid rain. This settling of PM, together with acid rain, can also stain and destroy stones and other materials such as statues and monuments, which include valuable cultural artefacts ( Awad et al., 2020 ).

2.3.1. PM emission in different countries

Due to the COVID-19 outbreak, PM emission in most countries has been reduced ( Chatterjee et al., 2020 ; Ghahremanloo et al., 2021 ; Gualtieri et al., 2020 ; Sharifi and Khavarian-Garmsir, 2020 ; Srivastava, 2020 ). Fig. 13 shows the impact of COVID19 on PM emission in a number of some countries around the world ( Myllyvirta, 2020 ). The largest reductions in PM pollution took place in Portugal, with 55%, followed by Norway, Sweden, and Poland with reductions of 32%, 30%, and 28%, respectively. Spain, Poland, and Finland recorded PM emission reductions of 19%, 17% and 16%, respectively. Both Romania and Croatia recorded no changes in PM level, with Switzerland and Hungary recording about a 3% increase in PM emission.

Reduction of PM emission in different countries ( Myllyvirta, 2020 ).

PM emissions have been significantly reduced during the epidemic in most regions of Italy. Fig. 14 illustrates the changes in COVID-19 containment emissions before and after a lockdown in major cities in Italy. According to a recent study by Sicard et al. ( Sicard et al., 2020 ), lockdown interventions have had a greater effect on PM emission. They found that confinement measures reduce PM 10 emissions in all major cities by “around 30% to 53%” and “around 35% to 56%”.

Comparison of PM emission in Italy (a) PM 2.5 emission (b) Changes of PM 2.5 emission (c) PM 10 emission (d) Changes of PM 10 emission ( Sicard et al., 2020 ).

2.4. Noise emission

Noise is characterised as an undesirable sound that may be produced from different activities, e.g. transit by engine vehicles and high volume music. Noise can cause health problems and alter the natural condition of ecosystems. It is among the most significant sources of disruption in people and the environment ( Zambrano-Monserrate and Ruano, 2019 ). The European Environment Agency (EEA) states that traffic noise is a serious environmental problem that negatively affects the health and security of millions of citizens in Europe. The consequences of long-term exposure to noise include sleep disorders, adverse effects on the heart and metabolic systems, and cognitive impairment in children. The EEA estimates that noise pollution contributes to 48,000 new cases of heart disease and 12,000 early deaths per year. They also reported chronic high irritation for 22 million people and a chronic high level of sleep disorder for 6.5 million people ( Lillywhite, 2020 ).

Most governments have imposed quarantine measures that require people to spend much more time at home. This has considerably reduced the use of private and public transport. Commercial activities have almost completely stopped. In most cities in the world, these changes have caused a significant decline in noise levels. This was followed by a significant decline in pollution from contaminants and greenhouse gas emissions. Noise pollution from sources like road, rail or air transport has been linked to economic activity. Consequently, we anticipate that the levels of transport noise will decrease significantly due to the decreased demand for mobility in the short term ( Ro, 2020 ).

For example, it was obvious that environmental noise in Italy was reduced after 8 th March 2020 (the lockdown start date) due to a halt in commercial and recreational activities. A seismograph facility in Lombardy city in Italy that was severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic indicated how the quarantine measures reduce both traffic and noise emissions. The comparison of the 24-hour seismic noise data before and after the lockdown period indicates a considerable drop in environmental noise in Italy ( Bressan, 2020 ).

3. Impact of COVID-19 on the socio-economic domain

COVID-19 has created a global health crisis where countless people are dying, human suffering is spreading, and people's lives are being upended ( Nicola et al., 2020 ). It is not only just a health crisis but also a social and economic crisis, both of which are fundamental to sustainable development ( Pirouz et al., 2020 ). On 11 th March 2020, when WHO declared a global pandemic, 118,000 reported cases spanning 114 countries with over 4,000 fatalities had been reported. It took 67 days from the first reported case to reach 100,000 cases, 11 days for the second 100,000, and just four days for the third ( United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2020 ). This has overwhelmed the health systems of even the richest countries with doctors being forced to make the painful decision of who lives and who dies. The COVID-19 pandemic has pushed the world into uncertainty and countries do not have a clear exit strategy in the absence of a vaccine. This pandemic has affected all segments of society. However, it is particularly damaging to vulnerable social groups, including people living in poverty, older persons, persons with disabilities, youths, indigenous people and ethnic minorities. People with no home or shelter such as refugees, migrants, or displaced persons will suffer disproportionately, both during the pandemic and in its aftermath. This might occur in multiple ways, such as experiencing limited movement, fewer employment opportunities, increased xenophobia, etc. The social crisis created by the COVID-19 pandemic may also increase inequality, discrimination and medium and long-term unemployment if not properly addressed by appropriate policies.

The protection measures taken to save lives are severely affecting economies all over the world. As discussed previously, the key protection measure adopted universally is the lockdown, which has forced people to work from home wherever possible. Workplace closures have disrupted supply chains and lowered productivity. In many instances, governments have closed borders to contain the spread. Other measures such as travel bans and the prohibition of sporting events and other mass gatherings are also in place. In addition, measures such as discouraging the use of public transport and public spaces, for example, restaurants, shopping centres and public attractions are also in place in many parts of the world. The situation is particularly dire in hospitality-related sectors and the global travel industry, including airlines, cruise companies, casinos and hotels which are facing a reduction in business activity of more than 90% ( Fernandes, 2020 ). The businesses that rely on social interactions like entertainment and tourism are suffering severely, and millions of people have lost their jobs. Layoffs, declines in personal income, and heightened uncertainty have made people spend less, triggering further business closures and job losses ( Ghosh, 2020 ).

A key performance indicator of economic health is Gross Domestic Product (GDP), typically calculated on a quarterly or annual basis. IMF provides a GDP growth estimate per quarter based on global economic developments during the near and medium-term. According to its estimate, the global economy is projected to contract sharply by 3% in 2020, which is much worse than the 2008 global financial crisis ( International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2020 ). The growth forecast was marked down by 6% in the April 2020 World Economic Outlook (WEO) compared to that of the October 2019 WEO and January 2020 WEO. Most economies in the advanced economy group are expected to contract in 2020, including the US, Japan, the UK, Germany, France, Italy and Spain by 5.9%, 5.4%, 6.5%, 7.0%, 7.2%, 9.1%, and 8.0% respectively. Fig. 15 a shows the effect of COVID-19 on the GDP of different countries around the globe. On the other hand, economies of emerging market and developing economies, excluding China, are projected to contract by only 1.0% in 2020. The economic recovery in 2021 will depend on the gradual rolling back of containment efforts in the latter part of 2020 that will restore consumer and investor confidence. According to the April 2020 WEO, the level of GDP at the end of 2021 in both advanced and emerging market and developing economies is expected to remain below the pre-virus baseline (January 2020 WEO Update), as shown in Fig. 15 b.

(a) Quarterly World GDP. 2019:Q1 =100, dashed line indicates estimates from January 2020 WEO; (b) GDP fall due to lockdown in selected countries.

A particular example of a country hardest hit by COVID-19 is Italy. During the early days of March, the Italian government imposed quarantine orders in major cities that locked down more than seventeen million people ( Andrews, 2020 ). The mobility index data by Google for Italy shows there has been a significant reduction in mobility (and therefore economic activity) across various facets of life. The reported decline of mobility in retail and recreation, grocery and pharmacy, transit stations and workplaces were 35%, 11%, 45% and 34% respectively ( Rubino, 2020 ). The Italian economy suffered great financial damage from the pandemic. The tourism, and hospitality sectors were among those most severely affected by foreign countries prohibiting travel to and from Italy, and by the government's national lockdowns in early March ( Brunton, 2020 ). A March 2020 study in Italy showed that about 99% of the companies in the housing and utility sector said the epidemic had affected their industry. In addition, transport and storage was the second most affected sector. Around 83% of companies operating in this sector said that their activities had been affected by the coronavirus ( Statista, 2020 ) pandemic. In April 2020, Italian Minister Roberto Gualtieri estimated a 6% reduction in the GDP for the year 2020 ( Bertacche et al., 2020 ). The government of Italy stopped all unnecessary companies, industries and economic activities on 21 st March 2020. Therefore The Economist estimates a 7% fall in GDP in 2020 ( Horowitz, 2020 ). The Economist predicted that the Italian debt-to-GDP ratio would grow from 130% to 180% by the end of 2020 ( Brunton, 2020 ) and it is also assumed that Italy will have difficulty repaying its debt ( Bertacche et al., 2020 ).

4. Impact of COVID-19 on the energy domain

COVID-19 has not only impacted health, society and the economy but it has also had a strong impact on the energy sector ( Chakraborty and Maity, 2020 ; Abu-Rayash and Dincer, 2020 ). World energy demand fell by 3.8% in the first quarter (Q1) of 2020 compared with Q1 2019. In Q1 of 2020, the global coal market was heavily impacted by both weather conditions and the downturn in economic activity resulting in an almost 8% fall compared to Q1 2019. The fall was primarily in the electricity sector as a result of substantial declines in demand (-2.5%) and competitive advantages from predominantly low-cost natural gas. The market for global oil has plummeted by almost 5%. Travel bans, border closures, and changes in work routines significantly decreased the demand for the use of personal vehicles and air transport. Thus rising global economic activity slowed down the use of fuel for transportation ( Madurai Elavarasan et al., 2020 ). In Q1 2020, the output from nuclear energy plants decreased worldwide, especially in Europe and the US, as they adjusted for lower levels of demand. Demand for natural gas dropped significantly, by approximately 2% in Q1 2020, with the biggest declines in China, Europe, and the United States. In the Q1 2020, the need for renewable energy grew by around 1.5%, driven in recent years by the increasing output of new wind and solar plants. Renewable energy sources substantially increased in the electricity generation mix, with record hourly renewable energy shares in Belgium, Italy, Germany, Hungary, and East America. The share of renewable energy sources in the electricity generation mix has increased. Table 2 shows the effect of COVID-19 outbreak on the energy demand around the world.

Impact of COVID-19 on global energy sector ( AEMO, 2020 ; CIS Editorial, 2020 ; Eurelectric, 2020 ; Livemint, 2020 ; Renewable Energy World, 2020 ; S&P Global, 2020 ; Madurai Elavarasan et al., 2020 ).

Different areas have implemented lockdown of various duration. Therefore, regional energy demand depends on when lockdowns were introduced and how lockdowns influence demand in each country. In Korea and Japan, the average impact on demand is reduced to less than 10%, with lower restrictions. In China, where the first COVID-19 confinement measures were introduced, not all regions faced equally stringent constraints. Nevertheless, virus control initiatives have resulted in a decline of up to 15% in weekly energy demand across China. In Europe, moderate to complete lockdowns were more radical. On average, a 17% reduction in weekly demand was experienced during temporary confinement periods. India's complete lockdown has cut energy requirements by approximately 30%, which indicates yearly energy needs are lowered by 0.6% for each incremental lockdown week ( International Energy Agency (IEA) 2020 ).

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has predicted an annual average decline in oil production of 9% in 2020, reflecting a return to 2012 levels. Broadly, as electricity demand has decreased by about 5% throughout the year, coal production may fall by 8%, and the output of coal-fired electricity generation could fall by more than 10%. During the entire year, gas demand may fall far beyond Q1 2020 due to a downward trend in power and industrial applications. Nuclear energy demand will also decrease in response to reduced electricity demand. The demand for renewable energies should grow due to low production costs and the choice of access to many power systems. Khan et al. (2020) reported that international trade is significantly and positively dependent on renewable energy. In addition, sustainable growth can be facilitated through the consumption of renewable energy which improves the environment, enhances national image globally and opens up international trade opportunities with environmentally friendly countries ( Khan et al., 2021 ). As such, policies that promote renewables can result in economic prosperity, create a better environment as well as meet critical goals for sustainable development ( Khan et al., 2020 ).

5. Preventive measures to control COVID-19 outbreak

COVID-19 is a major crisis needing an international response. Governments will ensure reliable information is provided to assist the public in combating this pandemic. Community health and infection control measures are urgently needed to reduce the damage done by COVID-19 and minimise the overall spread of the virus. Self-defence techniques include robust overall personal hygiene, face washing, refraining from touching the eyes, nose or mouth, maintaining physical distance and avoiding travel. In addition, different countries have already taken preventive measures, including the implementation of social distancing, medicine, forestation and a worldwide ban on wildlife trade. A significant aim of the community health system is to avoid SARS-CoV-2 transmission by limiting large gatherings. COVID-19 is transmitted by direct communication from individual to individual. Therefore, the key preventive technique is to limit mass gatherings. Table 3 shows the impact of lockdown measures on the recovery rate of COVID-19 infections. The baseline data for this table is the median value, for the corresponding day of the week, during the 5-week period 3 rd January to 6 th February 2020.

Mobility index report of different countries ( Ghosh, 2020 ; Johns Hopkins University (JHU), 2020 ; Worldometer, 2020 ).

As of today, no COVID-19 vaccine is available. Worldwide scientists are racing against time to develop the COVID-19 vaccine, and WHO is now monitoring more than 140 vaccine candidates. As of 29 th September 2020, about 122 candidates have been pre-clinically checked, i.e. determining whether an immune response is caused when administering the vaccine to animals ( Biorender, 2020 ). About 45 candidates are in stage I where tests on a small number of people are conducted to decide whether it is effective ( Biorender, 2020 ). About 29 candidates are in Phase II where hundreds of people are tested to assess additional health issues and doses ( Biorender, 2020 ). Only 14 candidates are currently in Phase III, where thousands of participants are taking a vaccine to assess any final safety concerns, especially with regard to side effects ( Biorender, 2020 ). 3 candidates are in Phase IV, where long-term effects of the vaccines on a larger population is observed ( Biorender, 2020 ). The first generation of COVID-19 vaccines is expected to gain approval by the end of 2020 or in early 2021 ( Peiris and Leung, 2020 ). It is anticipated that these vaccines will provide immunity to the population. These vaccines can also reduce the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and lead to a resumption of a pre-COVID-19 normal. Table 4 shows the list of vaccines that have been passed in the pre-clinical stage. In addition, according to the COVID-19 vaccine and therapeutics tracker, there are 398 therapeutic drugs in development. Of these, 83 are in the pre-clinical phase, 100 in Phase I, 224 in Phase II, 119 in Phase III and 46 in Phase IV ( Biorender, 2020 ).

List of vaccines that have passed the pre-clinical stage ( Biorender, 2020 ).

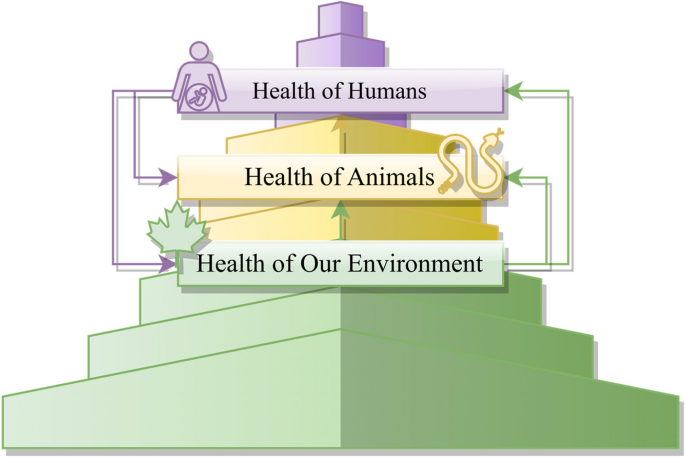

In addition to the above, forestation and a worldwide ban on wildlife trade can also play a significant role in reducing the spread of different viruses. More than 30% of the ground area is covered with forests. The imminent increase in population contributes to deforestation in agriculture or grazing for food, industries and property. The rise in ambient temperature, sea levels and extreme weather events affects not only the land and environment but also public health ( Ruscio et al., 2015 ; Arora and Mishra, 2020 ). Huge investment has been made into treatments, rehabilitation and medications to avoid the impact of this epidemic. However, it is important to focus on basic measures, e.g. forestation and wildlife protection. The COVID-19 infection was initially spread from the Seafood Market, Wuhan, China. Therefore, China temporarily banned wildlife markets in which animals are kept alive in small cages. It has been reported that 60% of transmittable diseases are animal-borne, 70% of which are estimated to have been borne by wild animals ( Chakraborty and Maity, 2020 ). Deforestation is also related to various kinds of diseases caused by birds, bats, etc. ( Afelt et al., 2018 ). For example, COVID-19 is a bat-borne disease that is transmitted to humans. Therefore, several scientists have advised various countries to ban wildlife trade indefinitely so that humans can be protected from new viruses and global pandemics like COVID-19.

6. Conclusion

In this article, comprehensive analyses of energy, environmental pollution, and socio-economic impacts in the context of health emergency events and the global responses to mitigate the effects of these events have been provided. COVID-19 is a worldwide pandemic that puts a stop to economic activity and poses a severe risk to overall wellbeing. The global socio-economic impact of COVID-19 includes higher unemployment and poverty rates, lower oil prices, altered education sectors, changes in the nature of work, lower GDPs and heightened risks to health care workers. Thus, social preparedness, as a collaboration between leaders, health care workers and researchers to foster meaningful partnerships and devise strategies to achieve socio-economic prosperity, is required to tackle future pandemic-like situations. The impact on the energy sector includes increased residential energy demand due to a reduction in mobility and a change in the nature of work. Lockdowns across the globe have restricted movement and have placed people primarily at home, which has, in turn, decreased industrial and commercial energy demand as well as waste generation. This reduction in demand has resulted in substantial decreases in NO 2, PM, and environmental noise emissions and as a consequence, a significant reduction in environmental pollution. Sustainable urban management that takes into account the positive benefits of ecological balance is vital to the decrease of viral infections and other diseases. Policies that promote sustainable development, ensuring cities can enforce recommended measures like social distancing and self-isolation will bring an overall benefit very quickly. The first generation of COVID-19 vaccines is expected to gain approval by the end of 2020 or in early 2021, which will provide immunity to the population. It is necessary to establish preventive epidemiological models to detect the occurrence of viruses like COVID-19 in advance. In addition, governments, policymakers, and stakeholders around the world need to take necessary steps, such as ensuring healthcare services for all citizens, supporting those who are working in frontline services and suffering significant financial impacts, ensuring social distancing, and focussing on building a sustainable future. It is also recommended that more investment is required in research and development to overcome this pandemic and prevent any similar crisis in the future.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Editor: Dr. Syed Abdul Rehman Khan

- Abdullah S., et al. Air quality status during 2020 Malaysia movement control order (MCO) due to 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pandemic. Sci. Total Environ. 2020; 729 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Abu-Rayash A., Dincer I. Analysis of the electricity demand trends amidst the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020; 68 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- ACR+, Municipal waste management and COVID-19. URL: https://www.acrplus.org/en/municipal-waste-management-covid-19 . Date accessed: 22nd September, 2020. 2020.

- Acter T., et al. Evolution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: a global health emergency. Sci. Total Environ. 2020; 730 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- AEMO, COVID-19 demand impact in Australia. https://aemo.com.au/en/news/demand-impact-australia-covid19 . Date accessed: 21st September, 2020. 2020.

- Afelt A., Frutos R., Devaux C. Bats, coronaviruses, and deforestation: toward the emergence of novel infectious diseases? Front. Microbiol. 2018; 9 702-702. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aldila D., et al. A mathematical study on the spread of COVID-19 considering social distancing and rapid assessment: the case of Jakarta, Indonesia. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020; 139 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Andrews, F., Before and after: Italy's tourist attractions left deserted amid coronavirus lockdown. https://www.thenational.ae/lifestyle/travel/before-and-after-italy-s-tourist-attractions-left-deserted-amid-coronavirus-lockdown-1.991274 . Date accessed: 21st September, 2020, in The National. 2020: Abu Dhabi.

- Arora N.K., Mishra J. COVID-19 and importance of environmental sustainability. Environ. Sustain. 2020; 3 (2):117–119. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ashraful A.M., et al. Production and comparison of fuel properties, engine performance, and emission characteristics of biodiesel from various non-edible vegetable oils: a review. Energy Convers. Manage. 2014; 80 :202–228. [ Google Scholar ]

- Atmosphere Monitoring Service. Air quality information confirms reduced activity levels due to lockdown in Italy. https://atmosphere.copernicus.eu/air-quality-information-confirms-reduced-activity-levels-due-lockdown-italy . Date accessed: 21st September, 2020. 2020.

- Awad O.I., et al. Particulate emissions from gasoline direct injection engines: a review of how current emission regulations are being met by automobile manufacturers. Sci. Total Environ. 2020; 718 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baensch-Baltruschat B., et al. Tyre and road wear particles (TRWP) - a review of generation, properties, emissions, human health risk, ecotoxicity, and fate in the environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020; 733 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck M.J., Hensher D.A. Insights into the impact of COVID-19 on household travel and activities in Australia – the early days under restrictions. Transp. Policy. 2020; 96 :76–93. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bertacche, M., Orihuela, R., and Colten, J., Italy struck by deadliest day as virus prompts industry shutdown. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-21/germany-plans-extra-spending-of-eu150-billion-scholz-says . Date accessed: 21st September, 2020, in Bloomberg. 2020.

- Biorender, COVID-19 vaccine & therapeutics tracker. URL: https://biorender.com/covid-vaccine-tracker . Date accessed: 28th September, 2020. 2020.

- Bressan, D., Coronavirus lockdowns cause worldwide decrease in man-made seismic noise. https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidbressan/2020/04/04/coronavirus-lockdowns-cause-worldwide-decrease-in-man-made-seismic-noise/#1643453464da . Date accessed: 21st September, 2020, in Forbes. 2020.

- Bruinen de Bruin Y., et al. Initial impacts of global risk mitigation measures taken during the combatting of the COVID-19 pandemic. Saf. Sci. 2020; 128 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brunton, J., Nothing less than a catastrophe': Venice left high and dry by coronavirus. https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2020/mar/17/nothing-less-than-a-catastrophe-venice-left-high-and-dry-by-coronavirus . date accessed: 21st September, 2020, in The Guardian. 2020.

- Cai C., et al. Temperature-responsive deep eutectic solvents as green and recyclable media for the efficient extraction of polysaccharides from Ganoderma lucidum. J. Cleaner Prod. 2020; 274 [ Google Scholar ]

- Chakraborty I., Maity P. COVID-19 outbreak: migration, effects on society, global environment and prevention. Sci. Total Environ. 2020; 728 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chatterjee A., et al. High rise in carbonaceous aerosols under very low anthropogenic emissions over eastern Himalaya, India: impact of lockdown for COVID-19 outbreak. Atmos. Environ. 2020 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chin A.W.H., et al. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in different environmental conditions. Lancet Microbe. 2020; 1 (1):e10. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chinazzi M., et al. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science. 2020; 368 (6489):395–400. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- CIS Editorial, Coronavirus impact on energy markets. URL: https://www.icis.com/explore/resources/news/2020/04/08/10482507/topic-page-coronavirus-impact-on-energy-markets . Date accessed: 2nd September, 2020. 2020.

- Cohen M.J. Does the COVID-19 outbreak mark the onset of a sustainable consumption transition? Sustainability. 2020; 16 (1):1–3. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chowdhury, M. A., M. B. A. Shuvho, M. A. Shahid, A. K. M. M. Haque, M. A. Kashem, S. S. Lam, H. C. Ong, M. A. Uddin and M. Mofijur (2021). "Prospect of biobased antiviral face mask to limit the coronavirus outbreak." Environmental Research 192: 110294. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- de Haas M., Faber R., Hamersma M. How COVID-19 and the Dutch ‘intelligent lockdown’ change activities, work and travel behaviour: evidence from longitudinal data in the Netherlands. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020; 6 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eurelectric, Impact of COVID 19 on customers and society. URL: https://cdn.eurelectric.org/media/4313/impact_of_covid_19_on_customers_and_society-2020-030-0216-01-e-h-584D2757.pdf . Date accessed: 28th Spetember, 2020. 2020.

- European Space Agency (ESA). Sentinel-5P. https://www.esa.int/Applications/Observing_the_Earth/Copernicus/Sentinel-5P . Date accessed: 21st September, 2020. 2020.

- Fattah I.M.R., et al. Impact of various biodiesel fuels obtained from edible and non-edible oils on engine exhaust gas and noise emissions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013; 18 :552–567. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fernandes, N., Economic effects of coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19) on the world economy. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3557504 . Date accessed: 21st September, 2020. 2020.

- Financial Times, Coronavirus: is Europe losing Italy? https://www.ft.com/content/f21cf708-759e-11ea-ad98-044200cb277f . Date accessed: 21st September, 2020, in Financial Times. 2020.

- Ghahremanloo M., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on air pollution levels in East Asia. Sci. Total Environ. 2021; 754 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ghosh, I. The road to recovery: which economies are reopening? URL: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/the-road-to-recovery-which-economies-are-reopening-covid-19/ . Date accessed: 22nd September, 2020. 2020 [cited 2020 25th July, 2020]; Available from: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/the-road-to-recovery-which-economies-are-reopening-covid-19/.

- Gorbalenya A.E., et al. The species severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 2020; 5 (4):536–544. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gualtieri G., et al. Quantifying road traffic impact on air quality in urban areas: a Covid19-induced lockdown analysis in Italy. Environ. Pollut. 2020 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Holshue M.L., et al. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020; 382 (10):929–936. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Horowitz, J., Italy locks down much of the country's north over the coronavirus. URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/07/world/europe/coronavirus-italy.html . Date accessed: 21st September, 2020, in The New York Times. 2020.

- Huang, Y., W.-c. Mok, Y.-s. Yam, J. L. Zhou, N. C. Surawski, B. Organ, E. F. C. Chan, M. Mofijur, T. M. I. Mahlia and H. C. Ong (2020). Evaluating in-use vehicle emissions using air quality monitoring stations and on-road remote sensing systems. Science of The Total Environment 740: 139868. [ PubMed ]

- International Energy Agency (IEA) IEA; Paris: 2020. Global Energy Review. https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2020 Date accessed: 21st September, 2020. 2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Economic Outlook, April 2020: The Great Lockdown. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/04/14/weo-april-2020 . Date accessed: 22nd September, 2020. 2020.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF), World economic outlook, April 2020: The Great Lockdown. URL: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/04/14/weo-april-2020 . Date accessed: 21st September, 2020. 2020.

- Jiang P., et al. Spatial-temporal potential exposure risk analytics and urban sustainability impacts related to COVID-19 mitigation: a perspective from car mobility behaviour. J. Cleaner Prod. 2021; 279 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johns Hopkins University (JHU). COVID-19 dashboard by the center for systems science and engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html . Date accessed: 25th July, 2020. 2020.

- Kabir M.T., et al. nCOVID-19 pandemic: from molecular pathogenesis to potential investigational therapeutics. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020; 8 616-616. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Khan S.A.R., et al. Measuring the impact of renewable energy, public health expenditure, logistics, and environmental performance on sustainable economic growth. Sustain. Dev. 2020; 28 (4):833–843. [ Google Scholar ]

- Khan S.A.R., et al. Investigating the effects of renewable energy on international trade and environmental quality. J. Environ. Manage. 2020; 272 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Khan S.A.R., et al. Determinants of economic growth and environmental sustainability in South Asian association for regional cooperation: evidence from panel ARDL. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Khan S.A.R., et al. A state-of-the-art review and meta-analysis on sustainable supply chain management: future research directions. J. Cleaner Prod. 2021; 278 [ Google Scholar ]

- Khoo, A., Coronavirus lockdown sees air pollution plummet across UK. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-52202974 . Date accessed: 21st September, 2020, in BBC News. 2020.

- Leal Filho W., et al. COVID-19 and the UN sustainable development goals: threat to solidarity or an opportunity? Sustainability. 2020; 12 (13):5343. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lillywhite, R., Air quality and wellbeing during COVID-19 lockdown. https://www.newswise.com/coronavirus/air-quality-and-wellbeing-during-covid-19-lockdown/?article_id=730455 . Date accessed: 21st September, 2020, in Newswise. 2020: USA.

- Liu M., et al. Waste paper recycling decision system based on material flow analysis and life cycle assessment: a case study of waste paper recycling from China. J. Environ. Manage. 2020; 255 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Livemint. India's energy demand falls by 30% due to COVID-19 lockdown. URL: https://www.livemint.com/news/world/lockdown-cuts-india-s-energy-demand-by-30-says-iea-11588235067694.html . Date accessed: 28th September, 2020. 2020.

- M Palash S., et al. Impacts of biodiesel combustion on NOx emissions and their reduction approaches. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2013; 23 (0):473–490. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ma B., et al. Recycle more, waste more? When recycling efforts increase resource consumption. J. Cleaner Prod. 2019; 206 :870–877. [ Google Scholar ]

- Madurai Elavarasan R., et al. COVID-19: impact analysis and recommendations for power sector operation. Appl. Energy. 2020; 279 115739-115739. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Madurai Elavarasan R., et al. COVID-19: impact analysis and recommendations for power sector operation. Appl. Energy. 2020 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mofijur M., et al. A study on the effects of promising edible and non-edible biodiesel feedstocks on engine performance and emissions production: a comparative evaluation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013; 23 (0):391–404. [ Google Scholar ]

- Munawer M.E. Human health and environmental impacts of coal combustion and post-combustion wastes. J. Sustain. Min. 2018; 17 (2):87–96. [ Google Scholar ]

- Myllyvirta, L., 11,000 air pollution-related deaths avoided in Europe as coal, oil consumption plummet. https://energyandcleanair.org/air-pollution-deaths-avoided-in-europe-as-coal-oil-plummet/ . Date accessed: 21st September, 2020. 2020.

- Mofijur, M., I. M. Rizwanul Fattah, A. B. M. Saiful Islam, M. N. Uddin, S. M. Ashrafur Rahman, M. A. Chowdhury, M. A. Alam and M. A. Uddin (2020). "Relationship between Weather Variables and New Daily COVID-19 Cases in Dhaka, Bangladesh." Sustainability 12(20): 8319.

- Nghiem L.D., et al. The COVID-19 pandemic: considerations for the waste and wastewater services sector. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2020; 1 [ Google Scholar ]

- Nicola M., et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): a review. Int. J. Surg. 2020; 78 :185–193. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Park G.W., et al. Evaluation of a new environmental sampling protocol for detection of human norovirus on inanimate surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015; 81 (17):5987–5992. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Peiris M., Leung G.M. What can we expect from first-generation COVID-19 vaccines? Lancet North Am. Ed. 2020 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pirouz B., et al. Investigating a serious challenge in the sustainable development process: analysis of confirmed cases of COVID-19 (new type of coronavirus) through a binary classification using artificial intelligence and regression analysis. Sustainability. 2020; 12 (6):2427. [ Google Scholar ]

- Qu G., et al. An imperative need for research on the role of environmental factors in transmission of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020; 54 (7):3730–3732. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Renewable Energy World, Renewables achieve clean energy record as COVID-19 hits demand. URL: https://www.renewableenergyworld.com/2020/04/06/renewables-achieve-clean-energy-record-as-covid-19-hits-demand/ . Date accessed: 28th September, 2020. 2020.

- Ro, C., Is coronavirus reducing noise pollution? https://www.forbes.com/sites/christinero/2020/04/19/is-coronavirus-reducing-noise-pollution/#2fe787d5766f . Date accessed: 21st September, 2020, in Forbes. 2020.

- Rubino, d.M., Coronavirus, il decreto del governo: tutte le misure per la zona arancione e quelle per il resto d'Italia. URL: https://www.repubblica.it/cronaca/2020/03/08/news/coronavirus_i_decreti_del_governo-250617415/ . Date accessed: 21st September, 2020, in la Repubblica. 2020.

- Ruscio B.A., et al. One health - a strategy for resilience in a changing arctic. Int. J. Circumpolar Health. 2015; 74 :27913. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- S&P Global, Japan, Singapore lockdowns to stifle Asian gas, power demand further. https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/market-insights/latest-news/natural-gas/040720-japan-singapore-lockdowns-to-stifle-asian-gas-power-demand-further . Date accessed: 21st September, 2020. 2020.

- Schanes K., Dobernig K., Gözet B. Food waste matters - a systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. J. Cleaner Prod. 2018; 182 :978–991. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sharifi A., Khavarian-Garmsir A.R. The COVID-19 pandemic: impacts on cities and major lessons for urban planning, design, and management. Sci. Total Environ. 2020 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sicard P., et al. Amplified ozone pollution in cities during the COVID-19 lockdown. Sci. Total Environ. 2020; 735 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sohrabi C., et al. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Int. J. Surg. 2020; 76 :71–76. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Srivastava A. COVID-19 and air pollution and meteorology-an intricate relationship: a review. Chemosphere. 2020 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Statista, Perceived impact of coronavirus (COVID-19) among Italian companies in March 2020, by macro sector. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1103017/perceived-impact-of-coronavirus-covid-19-among-italian-companies-by-sector/ . Date accessed: 21st September, 2020. 2020.

- Statista, COVID-19 lockdown affect on nitrogen dioxide (NO2) emissions in UK cities in March 2020 compared with March 2019. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1111519/no2-emissions-decrease-due-to-lockdown-united-kingdom/ . Date accessed: 21st September, 2020. 2020.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), The social and economic impact of COVID-19 in the Asia-Pacific region. https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/crisis-prevention-and-recovery/the-social-and-economic-impact-of-covid-19-in-asia-pacific.html . Date accessed: 21st September, 2020. 2020.

- van Doremalen N., et al. Aerosol and Surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020; 382 (16):1564–1567. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang D., et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020; 323 (11):1061–1069. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang Q., Su M. A preliminary assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on environment – a case study of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020; 728 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weitekamp C.A., et al. Health effects from freshly emitted versus oxidatively or photochemically aged air pollutants. Sci. Total Environ. 2020; 704 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Worldometer, Reported cases and deaths by country, territory, or conveyance. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ . Date accessed: 25th July, 2020. 2020.

- Worldometer, Reported cases and deaths by country, territory, or conveyance. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ . Date accessed: 22nd September, 2020. 2020.

- Yan Y., et al. The first 75 days of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) outbreak: recent advances, prevention, and treatment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020; 17 (7):2323. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ye Y., et al. Survivability, partitioning, and recovery of enveloped viruses in untreated municipal wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016; 50 (10):5077–5085. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zambrano-Monserrate M.A., Ruano M.A. Does environmental noise affect housing rental prices in developing countries? Evidence from Ecuador. Land Use Policy. 2019; 87 [ Google Scholar ]

- Zambrano-Monserrate M.A., Ruano M.A., Sanchez-Alcalde L. Indirect effects of COVID-19 on the environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020; 728 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhou P., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020; 579 (7798):270–273. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic – and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Ways to Discover College Essay Ideas

Tags: students , colleges , college admissions , college applications , college search , Coronavirus

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

How to decide if an mba is worth it.

Sarah Wood March 27, 2024

What to Wear to a Graduation

LaMont Jones, Jr. March 27, 2024

FAFSA Delays Alarm Families, Colleges

Sarah Wood March 25, 2024

Help Your Teen With the College Decision

Anayat Durrani March 25, 2024

Toward Semiconductor Gender Equity

Alexis McKittrick March 22, 2024

March Madness in the Classroom

Cole Claybourn March 21, 2024

20 Lower-Cost Online Private Colleges

Sarah Wood March 21, 2024

How to Choose a Microcredential

Sarah Wood March 20, 2024

Basic Components of an Online Course

Cole Claybourn March 19, 2024

Can You Double Minor in College?

Sarah Wood March 15, 2024

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Supplements

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 5, Issue 7

- The COVID-19 pandemic: diverse contexts; different epidemics—how and why?

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Wim Van Damme 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4773-5341 Ritwik Dahake 2 ,

- Alexandre Delamou 3 ,

- Brecht Ingelbeen 1 ,

- Edwin Wouters 4 , 5 ,

- Guido Vanham 6 , 7 ,

- Remco van de Pas 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1681-2604 Jean-Paul Dossou 1 , 8 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1294-3850 Seye Abimbola 10 , 11 ,

- Stefaan Van der Borght 12 ,

- Devadasan Narayanan 13 ,

- Gerald Bloom 14 ,

- Ian Van Engelgem 15 ,

- Mohamed Ali Ag Ahmed 16 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7000-3712 Joël Arthur Kiendrébéogo 1 , 17 , 18 ,

- Kristien Verdonck 1 ,

- Vincent De Brouwere 1 ,

- Kéfilath Bello 8 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5867-971X Helmut Kloos 19 ,

- Peter Aaby 20 ,

- Andreas Kalk 21 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2761-3566 Sameh Al-Awlaqi 22 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0968-0826 NS Prashanth 23 ,

- Jean-Jacques Muyembe-Tamfum 24 ,

- Placide Mbala 24 ,

- Steve Ahuka-Mundeke 24 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2393-1492 Yibeltal Assefa 25

- 1 Department of Public Health , Institute of Tropical Medicine , Antwerpen , Belgium

- 2 Independent Researcher , Bengaluru , India

- 3 Africa Centre of Excellence for Prevention and Control of Transmissible Diseases , Gamal Abdel Nasser University of Conakry , Conakry , Guinea

- 4 Department of Sociology and Centre for Population , University of Antwerp , Antwerpen , Belgium

- 5 Centre for Health Systems Research and Development , University of the Free State—Bloemfontein Campus , Bloemfontein , Free State , South Africa

- 6 Biomedical Department , Institute of Tropical Medicine , Antwerpen , Belgium

- 7 Biomedical Department , University of Antwerp , Antwerpen , Belgium

- 8 Public Health , Centre de recherche en Reproduction Humaine et en Démographie , Cotonou , Benin