Ethics and Morality

Is greed good, the psychology and philosophy of greed.

Posted October 6, 2014 | Reviewed by Kaja Perina

[Article revised on 2 May 2020.]

Greed is the disordered desire for more than is decent or deserved, not for the greater good but for one’s own selfish interest, and at the detriment of others and society at large. Greed can be for anything, but is most commonly for food, money, possessions, power, fame, status, attention , admiration, and sex.

The origins of greed

Greed often arises from early negative experiences such as parental absence, inconsistency, or neglect. In later life, feelings of anxiety and vulnerability, often combined with low self-esteem , lead the person to fixate on a substitute for the love and security that he or she so sorely lacked. The pursuit of this substitute distracts from negative feelings, and its accumulation provides much needed comfort and reassurance.

If greed is much more developed in human beings than in other animals, this is partly because human beings have the capacity to project themselves far into the future, to the time of their death and even beyond. The prospect of our eventual demise gives rise to anxiety about our purpose, value, and meaning.

In a bid to contain this existential anxiety, our culture provides us with ready-made narratives of life and death. Whenever existential anxiety threatens to surface into our conscious mind, we naturally turn to culture for comfort and consolation. Today, it is so happens that our culture—or lack of it, for our culture is in a state of flux and crisis—places a high value on materialism , and, by extension, on greed.

Our culture’s emphasis on greed is such that people have become immune to satisfaction. Having acquired one thing, they immediately set their sights on the next thing that suggests itself. Today, the object of desire is no longer satisfaction but desire itself.

Can greed be good?

Another theory of greed is that it is programmed into our genes because, in the course of evolution, it has tended to promote survival and reproduction. Without some measure of greed, individuals and communities are more likely to run out of resources, and to lack the means and motivation to innovate and achieve, making them more vulnerable to the vagaries of fate and the designs of their enemies.

Although a blind and blunt force, greed leads to superior economic and social outcomes. In contrast to altruism , which is a mature and refined capability, greed is a primitive and democratic impulse, and ideally suited to our culture of mass consumption. Altruism attracts passing praise, but really it is greed that our society rewards, and that delivers the material goods and economic growth upon which we have come to rely.

Like it or not, our society is fuelled by greed, and without greed would descend into poverty and anarchy. And it is not just our society: greed lies at the bottom of all successful modern and historical societies, and political systems designed to check or eliminate it have all ended in abject failure.

Gordon Gekko from the film Wall Street is especially eloquent on the benefits of greed:

Greed, for the lack of a better word, is good. Greed is right, greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms; greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge [sic.] has marked the upward surge of mankind.

The economist Milton Friedman argued that the problem of social organization is not to eradicate greed, but to set up an arrangement under which it does the least harm. For Friedman, capitalism is just that kind of system.

But greed is, to say the least, a mixed blessing. People who are consumed by greed become utterly fixated on the object of their greed. Their lives are reduced to little more than a quest to accumulate as much as possible of whatever it is they covet and crave. Even though they have met their every reasonable need and more, they are utterly unable to redirect their drives and desires to other and higher things.

After a time, greed becomes embarrassing, and people who are embarrassed by their greed may take to hiding it behind a carefully crafted persona. For example, people who run for political office because they crave power may tell others (and perhaps also themselves) that what they really want is to help people or serve their country, while decrying all those who, like them selves, crave power for the sake of power. Deception is a common outcome of greed, as are envy and spite.

Greed is also associated with negative psychological states such as stress , exhaustion, anxiety, depression , and despair, and with maladaptive behaviours such as gambling, scavenging, hoarding, trickery, and theft. By overriding reason, compassion, and love, greed loosens family and community ties and undermines the bonds and values upon which society is built.

Greed may drive the economy, but as recent history has made all too clear, unfettered greed can also precipitate a deep and long-lasting economic recession. What’s more, our consumer culture continues to inflict severe damage on the environment , resulting in, among others, deforestation, desertification, ocean acidification, species extinctions, and more frequent and severe extreme weather events. There is a question about whether such greed can be sustainable in the short term, never mind the long term.

Greed and Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

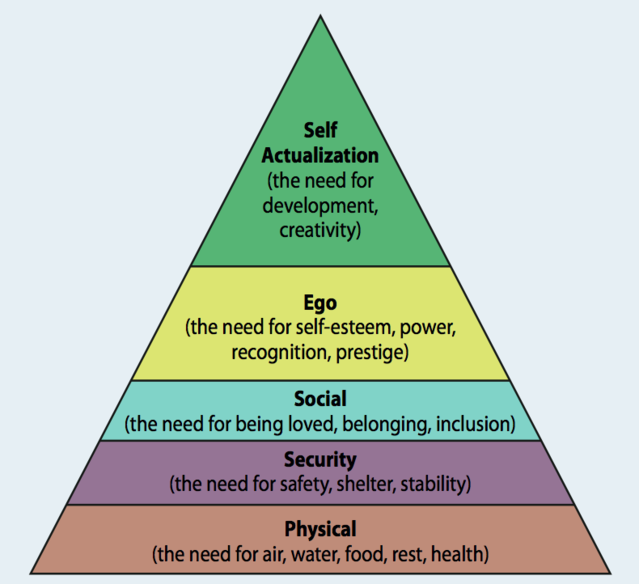

The psychologist Abraham Maslow proposed that healthy human beings have a certain number of needs, and that these needs can be arranged in a hierarchy, with some needs (such as physiological and safety needs) being more primitive or basic than others (such as social and ego needs). Maslow’s so-called ‘hierarchy of needs’ is often presented as a five-level pyramid, with higher needs coming into focus only once lower, more basic needs have been met.

Maslow called the bottom four levels of the pyramid ‘deficiency needs’ because a person does not feel anything if they are met. Thus, physical needs such as eating, drinking, and sleeping are deficiency needs, as are security needs, social needs such as friendship and sexual intimacy , and ego needs such as self-esteem and peer recognition.

On the other hand, Maslow called the fifth level of the pyramid a ‘growth need’ because it enables a person to ‘self-actualize’, that is, to reach his or her highest or fullest potential as a human being. Once people have met all their deficiency needs, the focus of their anxiety shifts to self-actualization, and they begin—even if only at a subconscious or semiconscious level—to contemplate the context and meaning of their life and life in general.

The problem with greed is that it grounds us on one of the lower levels of the pyramid, preventing us from ever reaching the pinnacle of growth and self-actualization. Of course, this is the precise purpose of greed: to defend against existential anxiety, which is the type of anxiety associated with the apex of the pyramid.

Greed and religion

Because it removes us from the bigger picture, because it prevents us from communing with ourselves and with God, greed is strongly condemned by all major religions.

In the Christian tradition, avarice is one of the seven deadly sins. It is understood as a form of idolatry that forsakes the love of God for the love of self and material things, forsakes things eternal for things temporal. In the Divine Comedy , the avaricious are bound prostrate on a floor of cold, hard rock as a punishment for their attachment to earthly goods and neglect of higher things.

In the Buddhist tradition, craving keeps us from the path to enlightenment.

Similarly, in the Bhagavad Gita , Lord Krishna calls covetousness a great destroyer and the foundation of sin:

It is covetousness that makes men commit sin. From covetousness proceeds wrath; from covetousness flows lust, and it is from covetousness that loss of judgment, deception, pride, arrogance, and malice, as also vindictiveness, shamelessness, loss of prosperity, loss of virtue, anxiety, and infamy spring, miserliness, cupidity, desire for every kind of improper act, pride of birth, pride of learning, pride of beauty, pride of wealth, pitilessness for all creatures, malevolence towards all…

The song The Fear by singer and songwriter Lily Allen is a modern, secular version of this tirade.

Here are a few choice lyrics by way of a conclusion:

I want to be rich and I want lots of money

I don’t care about clever I don’t care about funny

…And I’m a weapon of massive consumption

And it’s not my fault it’s how I’m programmed to function

…Forget about guns and forget ammunition

‘Cause I’m killing them all on my own little mission

I don’t know what’s right and what’s real anymore

And I don’t know how I’m meant to feel anymore

And when do you think it will all become clear?

‘Cause I’m being taken over by The Fear

Neel Burton is author of Heaven and Hell: The Psychology of the Emotions and other books.

Neel Burton, M.D. , is a psychiatrist, philosopher, and writer who lives and teaches in Oxford, England.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Greed Is Good or Is It? Quote and Meaning

Does Greed "Capture the Essence of the Evolutionary Spirit?"

- Important Historical Figures

- U.S. Presidents

- Native American History

- American Revolution

- America Moves Westward

- The Gilded Age

- Crimes & Disasters

- The Most Important Inventions of the Industrial Revolution

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

Greed Is Bad

Greed is good, greed is good in u.s. history.

- Why It Hasn't Worked in Real Life

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Amadeo-Closeup-582619cd3df78c6f6acca4e6.jpg)

- M.B.A, MIT Sloan School of Management

- M.S.P, Social Planning, Boston College

- B.A., University of Rochester

In the 1987 movie "Wall Street," Michael Douglas as Gordon Gekko gave an insightful speech where he said, "Greed, for lack of a better word, is good." He went on to make the point that greed is a clean drive that "captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms; greed for life, for money, for love, for knowledge has marked the upward surge of mankind."

Gekko then compared the United States to a "malfunctioning corporation" that greed could still save. He then said, "America has become a second-rate power. Its trade deficit and its fiscal deficit are at nightmare proportions."

Both of these last two points are truer now than in the 1980s. China surpassed the United States as the world's largest economy, with the European Union following closely behind. The trade deficit has only gotten worse in the last thirty years. The U.S. debt is now larger than the country's entire economic output.

Is greed bad? Can you trace the financial crisis of 2008 back to the greed of Michael Milkin, Ivan Boesky, and Carl Icahn? These are the Wall Street traders upon whom the movie was based. Greed causes the inevitable irrational exuberance that creates asset bubbles. Then still more greed blinds investors to the warning signs of collapse. In 2005, they ignored the inverted yield curve that signaled a recession.

That's certainly true of the 2008 financial crisis when traders created, bought, and sold sophisticated derivatives. The most damaging were mortgage-backed securities. They were based on underlying real mortgages. They were guaranteed by an insurance derivative called a credit default swap.

These derivatives worked great until 2006. That's when housing prices started falling.

The Fed began raising interest rates in 2004. Mortgage holders, especially those with adjustable rates, soon owed more than they could sell the house for. They began defaulting.

As a result, no one knew the underlying values of the mortgage-backed securities. Companies like American International Group (AIG) that wrote the credit default swaps ran out of cash to pay swap holders.

The Federal Reserve and the U.S. Treasury Department had to bail out AIG, along with Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the major banks.

Or is greed, as Gordon Gekko pointed out, good? Perhaps, if the first caveman didn't greedily want cooked meat and a warm cave, he never would have bothered to figure out how to start a fire.

Economists claim that the free market forces if left to themselves without government interference, unleashes the good qualities of greed. Capitalism itself is also based on a healthy form of greed.

Could Wall Street, the center of American capitalism, function without greed? Probably not, since it depends on the profit motive. The banks, hedge funds, and securities traders that drive the American financial system buy and sell stocks. The prices depend on the underlying earnings, which is another word for profit.

Without profit, there is no stock market, no Wall Street, and no financial system.

President Ronald Reagan's policies matched the "greed is good" mood of 1980s America. He promised to reduce government spending, taxes, and regulation. He wanted to get government out of the way to allow the forces of supply and demand to rule the market unfettered.

In 1982, Reagan kept his promise by deregulating banking. It led to the savings and loan crisis of 1989.

Reagan went against his promise of reduced government spending. Instead, he used Keynesian economics to end the recession of 1981. He tripled the national debt.

He both cut and raised taxes. In 1982, he cut income taxes to combat the recession. In 1988, he cut the corporate tax rate. He also expanded Medicare and increased payroll taxes to ensure the solvency of Social Security.

President Herbert Hoover also believed greed was good. He was an advocate of laissez-faire economics . He believed the free market and capitalism would stop the Great Depression. Hoover argued that economic assistance would make people stop working. He wanted the market to work itself out after the 1929 stock market crash.

Even after Congress pressured Hoover to take action, he would only help businesses. He believed their prosperity would trickle down to the average person. Despite his desire for a balanced budget, Hoover still added $6 billion to the debt.

Why Greed Is Good Hasn't Worked in Real Life

Why hasn't the "Greed is good" philosophy worked in real life? The United States has never had a truly free market. The government has always intervened through its spending and tax policies.

Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton imposed tariffs and taxes to pay for debt incurred from the Revolutionary War. Debt, and taxes to pay for it, increased with every subsequent war and economic crisis.

Since its beginning, the American government has restricted the free market by taxing some goods and not others. We may never know if greed, left to its own devices, could truly bring about good.

European Commission, Eurostat. " China, US and EU Are the Largest Economies in the World ," Page 1.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. " Exhibit 1. U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services ," Page 1.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. " Federal Debt: Total Public Debt as Percent of Gross Domestic Product ."

Universidad Francisco Marroquín. " The Fed Ignores the Yield Curve (But the Yield Curve Is Warning for a Recession) ."

The Brookings Institution. " The Origins of the Financial Crisis ," Pages 7-8, 32.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. " Open Market Operations ."

FDIC. " Crisis and Response: An FDIC History, 2008–2013 ," Page 13.

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. " Crisis and Response: An FDIC History, 2008–2013 ," Pages 24, 27.

William Boyes and Michael Melvin. " Fundamentals of Economics ," Pages 33-34. Cengage Learning, 2013.

Federal Reserve History. " Garn-St Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982 ."

Allen Independent School District. " A Shift to the Right Under Reagan ," Page 7.

TreasuryDirect. " Historical Debt Outstanding - Annual 1950 - 1999 ."

Tax Foundation. " Federal Individual Income Tax Rates History ," Pages 6, 8.

Tax Policy Center. " Corporate Top Tax Rate and Bracket, 1909 to 2018 ."

Social Security Administration. " Social Security Amendments of 1983: Legislative History and Summary of Provisions ," Pages 3-5.

The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. " Herbert Hoover on the Great Depression and New Deal, 1931-1933 ," Page 1.

TreasuryDirect. “ Historical Debt Outstanding - Annual 1900 - 1949 ."

National Bureau of Economic Research. " Alexander Hamilton's Market Based Debt Reduction Plan ," Pages 3-4.

- Dodd-Frank Act: History and Impact

- What Is Fiscal Policy? Definition and Examples

- A Beginner's Guide to Economic Indicators

- History of the US Federal Budget Deficit

- The Globalization of Capitalism

- The History of the U.S. Balance of Trade

- The 1980s American Economy

- Understanding How Budget Deficits Grow During Recessions

- The Three Historic Phases of Capitalism and How They Differ

- National Debt or Federal Deficit? What's the Difference?

- What Is National Debt and Where It Fits Within the Economy

- How Much U.S. Debt Does China Really Own?

- When Did the Great Recession End?

- What Is Free Trade? Definition, Theories, Pros, and Cons

- Comparing Monetary and Fiscal Policy

- What Is Neoliberalism? Definition and Examples

Greed Is Good: A 300-Year History of a Dangerous Idea

Not long ago, the pursuit of commercial self-interest was largely reviled. How did we come to accept it?

Among MBA students, few words provoke greater consternation than “greed.” Wonder aloud in a classroom whether some practice might fairly be described as greedy , and students don’t know whether to stick up for the Invisible Hand or seek absolution. Most, by turns, do a little of both.

Such reactions shouldn’t be surprising. Greed has always been the hobgoblin of capitalism, the mischief it makes a canker on the faith of capitalists. These students' troubled consciences are not the result of doubts about the efficacy of free markets, but of the centuries of moral reform that was required to make those markets as free as they are.

We sometimes forget that the pursuit of commercial self-interest was largely reviled until just a few centuries ago. “A man who is a merchant can seldom if ever please God,” St. Jerome said, expressing the prevailing belief in Christendom about the relative worthiness of a life devoted to trade. The choice to enter business didn’t necessarily deprive one of salvation, but it certainly hazarded his soul. “If thou wilt needs damn thyself, do it a more delicate way then drowning,” Iago tells a lovesick Rodrigo. “Make all the money thou canst.”

The problem of money-making was not only that it favored earthly delights over divine obligations. It also enflamed the tendency to prefer our own needs over those of the people around us and, more worrisome still, to recklessly trade their best interests for our own base satisfaction. St. Thomas Aquinas, who ranked greed among the seven deadly sins, warned that trade which aimed at no other purpose than expanding one’s wealth was “justly reprehensible” for “it serves the desire for profit which knows no limit.”

It was not until the mischievous moralist Bernard Mandeville that someone attempted to gloss greed as anything other than a shameful motive. A name now largely lost to history, Mandeville became a foil for 18th-century philosophy when, in 1705, he first proposed his infamous equation: Private vices yield public benefits. It came as part of The Fable of the Bees , an allegorical poem that described a thriving beehive where dark intentions keep the wheels of commerce turning. The outrage Mandeville stoked had less to do with this causal explanation than with the assertion that only by such means could a nation grow wealthy and strong. As he contended (with characteristic bluntness) in the conclusion to the Fable :

T’ enjoy the World’s Conveniences, Be fam’d in War, yet live in Ease, Without great Vices, is a vain EUTOPIA seated in the Brain.

Philosophers lined up to take their shots at Mandeville, whose moral paradox seemed so appalling precisely because it could not be so easily dismissed. The most notable among them was Adam Smith, the founding father of modern economics, who struggled to distinguish the mainspring of his system from the one Mandeville proposed.

Consider how Smith describes the selfish landowner, of whom he says the “proverb, that the eye is larger than the belly, never was more fully verified.” Looking out over his fields, in his imagination, he “consumes himself the whole harvest.” The belly, however, is not so obliging. The greedy landlord may engorge himself without making a dent in his crop, and he is “obliged to distribute” the rest in payment to all those who help supply his “economy of greatness.”

This is Smith’s Invisible Hand at work. It is counterintuitive force for good that, on first glance, seems not especially different from Mandeville’s contention that private vices yield public benefits. Smith was sensitive to this fact—Bernard Mandeville did not exactly make for good company—and he struggled to create distance between them.

He did this in two ways. First, Smith emphasized the moral distinction between primary aims and secondary effects. The Fable of the Bees never explicitly claimed that vice was good in itself , merely that it was advantageous—a subtle distinction that created confusion for Mandeville’s readers which the author, a cynic through and through, made little effort to dispel.

Smith, by contrast, made abundantly clear that, as a matter of moral assessment, one should distinguish between the intentions of an actor and the broader effects of his actions. Recall the greedy landlord. Yes, the primary aims of his daily labors—vanity, sway, self-indulgence—are far from admirable. But in spite of this fact, his efforts still have the effect of distributing widely “the necessaries of life” such that, “without intending it, without knowing it,” he, and others like him, “advance the interest of society.” This is another way of saying, for Smith, the moral logic of free markets was a law of unintended consequences. The Invisible Hand gives what a greedy landlord takes.

The second move Smith made was to effectively redefine “Greed.” Mandeville—and for that matter, the Church Fathers before him—spoke in such a way that any self-interested pursuit seemed morally suspect. Smith, for his part, refused to go along. He acknowledged that pursuing our interests often entails getting what we want from other people, but he maintained that not all of these pursuits, morally speaking, were equal. We get what we want in a complex commercial society—indeed, we get to have a complex commercial society—not because we seize things outright, but because we pursue them in a way that acknowledges legal and cultural constraints. That is how we distinguish the merchant from the mugger. Both pursue their own interests, but only one does so in a manner that confers legitimacy on the gains.

Greed, as such, became an acquisitive exercise that fell on the wrong side of this divide. Some of these activities, like the mugger’s, were fairly prohibited, but those of, say, the mean-spirited merchant were checked by censure and disgrace. These forces did not eradicate selfishness, but by the moral distinction they maintained, they helped establish a new ideal of the upstanding businessman.

That ideal was famously embodied by Smith’s friend, Benjamin Franklin. In his Autobiography , Franklin presented himself as the epitome of a new American Dream, a man who emerged from “Poverty & Obscurity” to attain “a State of Affluence & some Degree of Reputation in the World.” Franklin found nothing to be ashamed of in riches and repute, provided they were turned toward some broader purpose. His success allowed him to retire from the printing business at 42 so that he might spend the balance of his life on initiatives—civic, scientific, philanthropic—that all enhanced the common good.

The example of Franklin, and those like him, gave reason for optimism to those who understood the mixed blessing of free -markets. “Whenever we get a glimpse of the economic man, he is not selfish,” the great English economist Alfred Marshall wrote toward the end of the 19th century. “On the contrary, he is generally hard at work saving capital chiefly for the benefit of others.” By “others,” Marshall principally meant the members of one’s family, but he was also making a larger point about how our “self-interest” can expand and evolve when we have achieved financial security. The “love of money,” he declared, encompasses “an infinite variety of motives,” which “include many of the highest, the most refined, and the most unselfish elements of our nature.”

Then again, they also include lesser elements. Andrew Carnegie might have proclaimed that it was the responsibility of a rich man to act as “agent and trustee for his poorer brethren,” but the steel magnate’s beneficence was backstopped by cheap labor, dangerous working conditions, and swift action to break strikes. Besides, the active redistribution of wealth was something of a side-story (and a subversive one at that) to the moral logic of free markets. The Invisible Hand worked not by appealing to the altruism of exceptionally rich men, but by turning an antisocial instinct like greed into an unwitting civil servant.

Still, by the early 20th century, some believed his services might safely be dismissed. Reflecting on the extraordinary rate of development in Europe and the United States, John Maynard Keynes suggested that “the economic problem” (which he classed as the “struggle for subsistence”) might actually be “solved” by 2030. Then, Keynes said, we might “dare” to assess the “love of money” at its “true value,” which, for those who couldn’t wait, he described as “a somewhat disgusting morbidity, one of those semi-criminal, semi-pathological propensities which one hands over with a shudder to the specialists in mental disease.” In other words, at last, we could afford to shift our attention from the advantages of greed and to disadvantages of greedy people.

Keynes’s views were extreme, but only in expression. Substantively, everyone agreed with him that greed was still a vice and a rather vicious one at that. A. Lawrence Lowell, the President of Harvard University, called “a motive above personal profit” among businessmen a prerequisite for establishing Harvard Business School, while its first dean, Edwin Francis Gay, told a prospective faculty hire that the pedagogy of his institution did not include “teaching young men to be ‘moneymakers.’”

As a lingering distaste for the profit-motive combined with continued economic development, the assumption began to wane that self-interested pursuits were the organizing force of a modern economy. Keynes pointed to this when he extolled the “tendency of big enterprise to socialize itself,” a phenomenon by which enlightened middle-managers—guided by science, reason, and administrative esprit du corps—would at last supplant the animism of the Invisible Hand. If “the corporate system is to survive,” Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means wrote in the conclusion to their seminal study of the modern American corporation, “the ‘control’ of the great corporation should develop into a purely neutral technocracy, balancing a variety of claims by various groups in the community and assigning to each a portion of the income stream on the basis of public policy rather than private cupidity.”

Berle and Means wrote these lines in 1932. In hindsight, they don’t seem exactly prescient. As a matter of economic science, the revolt against managerial capitalism, and the reevaluation of greed, took shape after the Second World War, led by efforts of the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter and, later on, the architects of Agency Theory. Against Keynes, Schumpeter presented a new vision of capitalism as “Creative Destruction.” The “relevant problem” for economists, he said, was not how capitalism “administers existing structures” (the purview of the middle-manager) but “how it creates and destroys them,” an anarchic activity undertaken by Schumpeter’s hero, the entrepreneur.

As an icon for capitalism, the pugnacious individualism of the entrepreneur was entirely at odds with the vision of Berle and Means. According to Schumpeter, what drove an economy was headlong innovation, not careful administration. This was the hallmark of entrepreneurial activity, the courageous effort of an inspired mind, not the fruit of corporate collaboration.

An appeal to “private cupidity” was not the only way of eliciting such inspiration, but it was certainly the most obvious. It was also favored by the enthusiasts of Agency Theory, who began filling the ranks of business schools and economics departments in the ‘60s and ‘70s. They eschewed the common cause of managerial capitalism as an endorsement of soft socialism, an inducement to fuzzy thinking, and a recipe for corporate decay. Instead, they portrayed the company as a collection of self-serving individuals whose interests could be aligned with those of shareholders only by appeals to Keynes’s semi-pathological propensity: the love of money. Thus, the rise of stock options, performance pay, and other compensatory strategies that aimed to spark innovation in the executive suite. For the most part, the moral arguments called upon to support these recommendations took a familiar form. Greedy behavior could be tolerated, even encouraged, but only if it eliminated worse offenses: starvation, exposure, idiocy.

But choosing a lesser evil at the expense of a greater one is merely an exercise in good judgment. It does nothing to change the nature of what is chosen, and when a nation no longer fears, first and foremost, the pangs of abject misery, it may be said that greed has largely served its social purpose. An affluent people might fairly turn their attention to the ugly behavior greed encourages and to the social and political perils of extreme inequality. They may have good reason, in short, to restrain the Invisible Hand.

Accordingly, in recent decades, a new line of argument has opened in the moral defense of greed, a change that was augured and embodied above all others by Ayn Rand. Rand understood that, when someone defended greed by an appeal to the common good, he was also conceding that greed could be checked by it. As the moral foundation for free markets, such an argument was entirely unacceptable to Rand, who took aim at it in her 1965 essay What is Capitalism?

“Implicitly, uncritically, and by default, political economy accepted as its axioms the fundamental tenets of collectivism,” she declared in a sweeping indictment of the Invisible Hand tradition. “The moral justification of capitalism does not lie in the altruist claim that it represents the best way to achieve ‘the common good.’” That may be so, but it is “merely a secondary consequence.” Instead, capitalism is the only economic system in which “the exceptional men” are not “held down by the majority” and in which (as she said elsewhere) the “only good” that humans can do to one another and “the only statement of their proper relationship” are both acknowledged: “Hands off!”

A woman who titled a collection of essays The Virtue of Selfishness , Rand was given to brackish candor. Yet at a time when many people think that the common good is more often imperiled than empowered by unbridled greed, she provides an alternative defense of the acquisitive instinct by appealing to an ethics of gross achievement and a formulation of personal liberty that looks with suspicion and disdain on any talk of civic duty, moral obligation, or even prudential restraint. Her aim was simple: To relieve greed, once and for all, of any moral taint.

“I think greed is healthy,” an apparent acolyte told the graduating class at Berkeley’s business school in 1986. “You can be greedy and still feel good about yourself.” The speaker was Ivan Boesky, who shortly thereafter would be fined $100 million, and later go to prison, for insider trading. His address was adapted by Oliver Stone as the basis for Gordon Gekko’s “greed is good” speech in Wall Street . An exhortation to shareholders of a sagging company, it reads like a corporate raider’s war cry, with Gekko the grinning avatar of Agency Theory.

Such a blunt endorsement of greed today remains far beyond the mainstream. If we tolerate greed, it is because we accept the hard bargain of the Invisible Hand. We believe that greed can do good, not that it is good. That, we are unwilling to say.

But for the most part, I don’t think we don’t say very much about greed, not comfortably at least. Perhaps that is the inevitable price of an economic system that relies on the vigor of self-interested pursuits, that it instills a kind of moral quietism in the face of avarice, for whether out of a desire to appear non-judgmental or for reasons of moral expediency, unless some action verges on the criminal, we hesitate to call it greed, much less evidence of someone greedy. We don’t deny the existence of such individuals, but like Bigfoot, they tend to be more rumored than seen.

Moral revolutions come about in different ways. If we reject some conduct but rarely admit an example, we enjoy the benefit of being high-minded without the burden of moral restraint. We also embolden that behavior, which proceeds with a presumptive blessing. As a matter of public discourse and polite conversation, “Greed” is unlikely to be “Good” anytime soon, but a vice need not become a virtue for the end result to look the same.

Milton Friedman told us greed was good. He was half right

50 years ago Milton Friedman declared that greed was good, but there was always more to the story – as well as making profits firms hold the unique power to achieve social objectives, writes UNSW Business School's Richard Holden

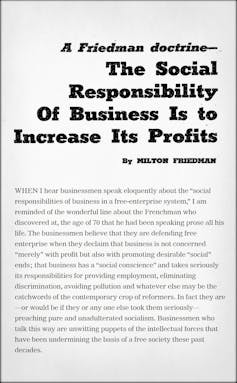

Fifty years ago, well before the movie Wall Street, Chicago economist Milton Friedman set down what for many was the essence of the famous speech on Wall Street in an article for the New York Times magazine titled: “ The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits ”.

His point, which along with his other contributions was recognised when he was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1976, was that businesses serve society best when they abandon talk of “social responsibilities” and solely maximise returns for shareholders.

Incredibly influential (the past week has seen special conferences and anniversary analyses ), the essay has been credited with ushering in the doctrine of “ shareholder primacy ,” and with it short-termism, hostile takeovers, colossal frauds and savage job cuts.

It’s a doctrine not seriously challenged until the 2008-2009 global financial crisis. But in an important respect, it was misread.

Although not clear from the title of the essay , Friedman himself was quite concerned with broader social aims. His essay was about how best to achieve them. His point was that if companies made as much money as they could for their shareholders, those shareholders could spend it on social goals, “if they wished to do so”.

For the company to attempt to guess what goals its shareholders would want to support and to support them itself would be for the company to do its main job badly. Although it made a certain sort of sense, the Friedman doctrine has turned out to be incomplete.

As Harvard University’s Oliver Hart (who also won the Nobel Prize for Economics) has pointed out, corporations are often much better than their shareholders at achieving the goals their shareholders care about.

Corporations can achieve more than individuals

Individual shareholders can’t do much to avert climate change, but the corporations they own can.

A mining company could either stop operating an environmentally-damaging mine or run the mine, make a bunch of money and pay it to shareholders who could use the money to mitigate the damage “if they wished to do so”. It's hard to argue that, if shareholders do indeed “wish to do so”, the first option isn’t better.

To cite a recent instance is hard to “un-blow-up” 46,000 years of Indigenous heritage .

In contrast, Friedman was almost surely right about corporate charitable contributions, which was in many ways the impetus for the article. In what way are corporations better at giving money to charities (and political parties) than individuals? In none that are obvious (and not potentially corrupt).

So where do we draw the line about what corporations do and don’t do?

Proponents of the “stakeholder view” now endorsed by an increasing number of superannuation funds think corporations should have a composite objective that takes into account the interests of shareholders, bondholders, workers, suppliers, the environment, and more.

Yet a point in every direction…

The problem with this, as recognised by the arrow-covered pointless man in the animated Harry Nilsson film What’s The Point? is that “a point in every direction is the same as no point at all”.

As Friedman put it, composite objectives suffer from “looseness and lack of rigour”.

Others, such as Hart and University of Chicago professor Luigi Zingales think firms should find out what shareholders most want, and “ pursue that goal .” This has the virtue of permitting a social objective while creating a concrete, measurable goal.

It’s a way of giving shareholders (and super fund members) a voice that is more direct than simply electing directors every few years.

Friedman helped start an important discussion. Fifty years on, it isn’t finished.

Richard Holden is a Professor of Economics at UNSW Business School . This article first appeared on The Conversation.

You are free to republish this article both online and in print. We ask that you follow some simple guidelines .

Please do not edit the piece, ensure that you attribute the author, their institute, and mention that the article was originally published on Business Think.

By copying the HTML below, you will be adhering to all our guidelines.

Press Ctrl-C to copy

Vital Signs: 50 years ago Milton Friedman told us greed was good. He was half right

Professor of Economics, UNSW Sydney

Disclosure statement

Richard Holden does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

UNSW Sydney provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

The point is, ladies and gentleman, that greed – for lack of a better word – is good. Greed is right. Greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms – greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge – has marked the upward surge of mankind.

– Gordon Gekko, Wall Street 1987

Fifty years ago, well before the movie Wall Street, Chicago economist Milton Friedman set down what for many was the essence of the famous speech in Wall Street in an article for the New York times magazine entitled “ The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits ”.

His point, which along with his other contributions was recognised when he was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1976, was that businesses serve society best when they abandon talk of “social responsibilities” and solely maximise returns for shareholders.

Incredibly influential (the past week has seen special conferences and anniversary analyses ), the essay has been credited with ushering in the doctrine of “ shareholder primacy ,” and with it short-termism, hostile takeovers, colossal frauds and savage job cuts.

It’s a doctrine not seriously challenged until the 2008-2009 global financial crisis.

But in an important respect it was misread.

Although not clear from the title of the essay , Friedman himself was quite concerned with broader social aims.

His essay was about how best to achieve them.

His point was that if companies made as much money as they could for their shareholders, those shareholders could spend it on social goals, “if they wished to do so”.

For the company to attempt to guess what goals its shareholders would want to support and to support them itself would be for the company to do its main job badly.

Although it made a certain sort of sense, the Friedman doctrine has turned out to be incomplete.

As Harvard University’s Oliver Hart (who also won the Nobel Prize for Economics) has pointed out, corporations are often much better than their shareholders at achieving the goals their shareholders care about.

Corporations can achieve more than individuals

Individual shareholders can’t do much to avert climate change, but the corporations they own can.

A mining company could either stop operating an environmentally-damaging mine or run the mine, make a bunch of money and pay it to shareholders who could use the money to mitigate the damage “if they wished to do so”.

Its hard to argue that, if shareholders do indeed “wish to do so”, the first option isn’t better.

To cite a recent instance, is hard to “un-blow-up” 46,000 years of Indigenous heritage .

Read more: Corporate dysfunction on Indigenous affairs: Why heads rolled at Rio Tinto

In contrast, Friedman was almost surely right about corporate charitable contributions, which was in many ways the impetus for the article.

In what way are corporations better at giving money to charities (and political parties) than individuals? In none that are obvious (and not potentially corrupt).

So where do we draw the line about what corporations do and don’t do?

Proponents of the “stakeholder view” now endorsed by an increasing number of superannuation funds think corporations should have a composite objective that takes into account the interests of shareholders, bondholders, workers, suppliers, the environment, and more.

Yet a point in every direction…

The problem with this, as recognised by the arrow-covered pointless man in the animated Harry Nilsson film What’s The Point? is that “a point in every direction is the same as no point at all”.

As Friedman put it, composite objectives suffer from “looseness and lack of rigour”.

Others, such as Hart and University of Chicago professor Luigi Zingales think firms should find out what shareholders most want, and “ pursue that goal .”

This has the virtue of permitting a social objective while creating a concrete, measurable goal.

It’s a way of giving shareholders (and super fund members) a voice that is more direct than simply electing directors every few years.

Friedman helped start an important discussion. Fifty years on, it isn’t finished.

- Milton Friedman

- Social licence to operate

- Vital signs

- Social responsibility

- Shareholder primacy

Project Offier - Diversity & Inclusion

Senior Lecturer - Earth System Science

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

The New York Times

The learning network | greed is good.

Greed Is Good?

Note: This lesson was originally published on an older version of The Learning Network; the link to the related Times article will take you to a page on the old site.

Teaching ideas based on New York Times content.

- See all lesson plans »

Overview of Lesson Plan: In this lesson, students consider the traits and actions of greedy characters in Dickens stories and other literature, drawing parallels to current events. They then write a newspaper-style profile of one character.

Shannon Doyne, The New York Times Learning Network

Suggested Time Allowance: one or two class periods.

Activities and Procedures:

1. WARM-UP/DO-NOW: Write “GREED” on the board. Then invite students to name greedy characters they have encountered in fiction (novels, short stories, poems, fairy tales, movies, television, etc.) and in the news media. Ask “What makes him or her greedy?” as you write a list of the names on the board. Have students choose one character from the list. Then distribute copies of the “Someone Wants But So” handout and give students time to complete it. When they have finished, have students who wrote about the same character work together, if any did. Have group members share their ideas, then report to the whole class. Ask individual students who chose unique characters to also tell about their characters. Be sure each group or student talks about whether the character treats others fairly, the degree to which greed overshadows fair treatment, and how other characters’ happiness, security or well-being is (or is not) diminished as a result of this character’s actions. Are there any significant differences between the fictional and nonfictional characters? Then tell students that they will now read an article about a new television movie based on a novel by Charles Dickens, in which greed, unfairness and economic hardship are central elements.

2. ARTICLE QUESTIONS: As a class, read and discuss “Dickens and the Business Cycle: The Victorian Way of Debt,” focusing on the following questions: a. What is timely about the PBS adaptation of “Little Dorrit”? b. How is William Dorrit treated unfairly? What about his daughter Amy? c. What motivated the “deliciously bad” characters? d. Alessandra Stanley writes, “‘Little Dorrit’ is as rich at the margins as at the center” thanks to its characters. What does she mean by this? e. Do you think “Little Dorrit” viewers are uplifted by the story, depressed or some combination of the two? Explain.

3. ACTIVITY: Turn students’ attention to the novel they are currently reading for class, or one they have read recently that lends itself to a discussion about money, greed, power, fairness and so on. Before distributing the handout “Money Matters,” have students briefly summarize the plot, or what they have read so far, if they are in the middle of the book. Then, have students work in pairs to complete the handout. Encourage them to include, but keep separate, specific details from the novel and their own interpretations. When students have completed their handouts, lead them in a discussion that addresses each topic they wrote about. Ask: What details did you pull out from the text to illustrate each theme or element? What interpretations did you make with respect to these headings? How does the novel help you understand greed as a motivation? How does it help you understand the effects of greed on others? Is this novel “timeless” in how it deals with these issues? If so, how, and if not, why not? What parallels, if any, exist between this novel and the current climate in which we live (like the ones pointed out in the article about “Little Dorrit”)? Are there lessons to be learned here? If so, what are they?

4. FOR HOMEWORK OR FUTURE CLASSES: Individually, students write a newspaper profile of the “greedy” character of their choice, as though he or she were real. Tell them to use their completed graphic organizer from the warm-up activity to help them add details about what the character wants, how he or she goes about getting it, what happens as a result and how others are affected by his or her actions and choices. Encourage them to reread the work, or view it again if working with a film or television show, in order to glean specific details. Students might model their profiles on a published piece like “The Talented Mr. Madoff.” Consider having students publish their revised profiles as a special literary supplement to your school newspaper.

Related Times Resources:

- ADDITIONAL TIMES ARTICLES AND MULTIMEDIA: Article: Amid Swaths of Greed, Pockets of Benevolence Article: When Dockets Imitate Drama Domestic Disturbances Blog: “Diagnosis: Greed” Outposts Blog: “Greed and Need” Economix Blog: “Sin Cycle: When Greed Isn’t Good” Paper Cuts Blog: “Is There a Cure for Greed?”

- LEARNING NETWORK RESOURCES: Teaching With The Times: Literature Teaching With The Times: Film in the Classroom Lesson Plan: Bubble Trouble Analyzing Causes of the Economic Crisis Lesson Plan: It’s the Same Old Story Finding Commonalities Between Classic Literature and Popular Stories Student Crossword: Great Books and Authors

- ARCHIVAL TIMES MATERIALS: Review: A Dickens Adaptation in Novelistic Detail A 1988 review of new television adaptations of Dickens’ works, including “Little Dorrit.”

- TIMES TOPICS: Charles Dickens United States Economy

Extension Activities: 1. Read this quote from Charles Dickens’ “David Copperfield” (1849): “Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pound ought and six, result misery.” Write a short story set in the time period of your choice, using this quote as a theme. 2. Interview people and conduct research on the topic “How to Want Less.” Then write an essay or poem on the topic, to be shared with the class.

Interdisciplinary Connections: Economics – Investigate the impact of the economic slowdown in your community. You might interview a family member or older friend who has made changes to his or her business operations, work time, spending or other efforts related to our changing economy. You might read the series “Recession Challenges Small Businesses” to see how other writers have approached the subject.

Academic Content Standards: Grades six to 12. Language Arts Standard 1 – Demonstrates competence in the general skills and strategies of the writing process. Language Arts Standard 2 – Uses the stylistic and rhetorical aspects of writing. Language Arts Standard 3 – Uses grammatical and mechanical conventions in written compositions. Language Arts Standard 5 – Uses the general skills and strategies of the reading process. Economics Standard 8 – Understands basic concepts of United States fiscal policy and monetary policy.

This lesson plan may be used to address the academic standards listed above. These standards are drawn from Content Knowledge: A Compendium of Standards and Benchmarks for K-12 Education; 3rd and 4th Editions and have been provided courtesy of the Mid-continent Research for Education and Learning in Aurora, Colorado.

Comments are no longer being accepted.

What's Next

Why Greed is Good

How it works

In today’s society, there hasn’t been an alternative way besides a collective economic benefit that would work in our economic system. That’s because the world runs on greed. No matter how unfair it may seem to those who are less fortunate than those of upper power. The government knows what’s best for the people and even, so they give opportunities to those who are less fortunate. Even though an individual economic interest would be the more popular idea for those less fortunate, simply because they have more of a say in what gets implemented.

Ultimately limiting the power of the government. What they fail to realize is that capitalism, provides for an expansion in economic growth, more incentives, consumers choose their desired product, and more benefits. Collective economic benefits fit more into the scheme of a balanced society for the simple reason of allowing the popular demand to be instilled. In this type of economic system, the wealthy will focus on being as efficient as possible. “Firms in a capitalist-based society face an incentive to be efficient and produce goods that are in demand (Pettinger, T).” Ultimately, giving the citizens a voice on what needs to be implemented or not. In the past, there hasn’t been another way other than the greed of an economy that has worked. The world, in general, runs on the wealth of others but that doesn’t mean that it doesn’t allow others to get into a position of that matter.

In the YouTube video with Milton Friedman, American economist for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and his theory of stabilization policy, states, “the great achievements haven’t come from government bureaus…and in which cases, where they have escaped the kind of grinding poverty, are in capitalism and free trade.” The productivity in a capitalist system is unmatched and there are opportunities for everyone out there to make something out of themselves. If private firms know they can make a profit off what you’re doing, then they will allow it. The world revolves around money. It always has been. Greed is the driving force of capitalism and without it, capitalism wouldn’t exist and many of inventions wouldn’t have become what they are today. For example, Henry Ford when he revolutionized the automobile industry. Examples like these show the importance of a collective based economy in the world today. One of the main issues with capitalism is that it seems that the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. Those who are wealthy are in power because they have the money to make the change and allow funding to those less fortunate. It’s harder for lower-class citizens to rise above this because there is an everlasting chain with this process. Most of the people who get into power inherit the wealth from their family or friend. This limits the lower-class ability to come out of poverty because there are barriers to entry for them. The fact of the matter is that history doesn’t show any favor to other forms because there hasn’t been one discovered, at least one who’s as efficient as capitalism. The thought of individual economic interest is unheard of just because of the system we are in. The ratio of rich people to poor is insane. Distributing the wealth isn’t going to solve the issue rather it would cause an outburst from those who are in power. The people of the highest power in the government don’t reward virtue. Thus, finding people who are going to organize society for us is unprecedented.

A collective economy should be the norm because it allows for a more advanced individual prosperity as opposed to the restrictions individual economic interest has in it whereby it attempts to distribute wealth from the rich. Capitalism also allows markets to develop and mature on their own subsequently dying out on their own, making way for a new market opportunity to replace them and in theory new people will get rich. In any way you look at it collectively or individual or not you can’t solely trust anyone to make the greatest decision. If the reward is lower than the risk, then you’re being fooled. This country, and many others, operates on a low risk, high-reward aspect. Now, this relates to many engineering jobs because as in engineer your job is to be as efficient as possible and operate at a point, where a net loss isn’t even a thought. We must take into consideration that our data is going to based on cash flow patterns, money management, appreciation and depreciation, and other common economic knowledge.

All these aspects help engineers understand the meaning of money and how it’s used and so forth. Knowing these elements will help us understand what went wrong and how we could fix them. Being in a collective economic system will help too because we’ll be allowed funding through government help once the demand for our invention is arising. The fact that history has showed us that success can happen in this type of economic system should be a motivation factor for up and coming engineers. It gives us the opportunity to make a change in the economy by providing our fellow citizens with our byproduct. In conclusion staying in a collective economy is the most reliable thing us citizens can do no matter the inequality of rich and poor. It gives us the best chance to become more successful because it helps expands economic growth and gives the citizens an input on what should be implemented. The saying, “if it’s not broke, don’t fix it”, can abide by this conclusion because from history alone it shows us that there isn’t a more efficient way.

Cite this page

Why Greed Is Good. (2021, Jul 04). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/why-greed-is-good/

"Why Greed Is Good." PapersOwl.com , 4 Jul 2021, https://papersowl.com/examples/why-greed-is-good/

PapersOwl.com. (2021). Why Greed Is Good . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/why-greed-is-good/ [Accessed: 24 Apr. 2024]

"Why Greed Is Good." PapersOwl.com, Jul 04, 2021. Accessed April 24, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/why-greed-is-good/

"Why Greed Is Good," PapersOwl.com , 04-Jul-2021. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/why-greed-is-good/. [Accessed: 24-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2021). Why Greed Is Good . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/why-greed-is-good/ [Accessed: 24-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Science Proves It: Greed Is Good

L et us now stop and praise the plutocrat. Really. Props too to the bailed out, the overprivileged, the exploiters of the little guys, the Machiavellian narcissists who earn way, way too much and are taking advantage of the rest of us to stay that way. Oh, and let’s praise Putin too.

Greed really is good, as are income inequality, bullying across class lines and even the iron fist of the political strongman—in certain contexts, at least. That’s the conclusion of a new study from the University of Oxford, just published in Nature Communications . Using mathematical models of human social groups, the researchers found that when communities are hierarchically structured—meaning that there is a potential for high inequality too—the individuals at the top tend to make more of an effort in the interests of the group than those at the bottom, including competing with outside groups and facing potential danger in the process.

The authors detected that behavior across nearly all cultures, and cite corresponding studies of chimps, blue monkeys and ring-tail lemurs, showing that higher ranking individuals tend to venture closer to the perilous border of the group’s territory during patrols, and high-ranking females will join the males in combat with other groups. In return, the lower ranking members are allowed to become what is known as free-riders, hiding behind the skirts of the big shots and contributing little on their own. The price for this protection? Don’t cross the dominant members of your own group or they’ll direct their power—and ire—at you too.

Studies like this always raise illuminating and troubling questions and are easy to exploit by nearly anyone with a social or political agenda. (See? There really is such a thing as the safety net turning into a hammock; the makers versus the takers really do exist. Or: See? Bully-boy behavior is the stuff of the apes, something egalitarian societies—and homo sapiens as a whole—ought to have left behind by now.)

But, as in nearly all matters of human behavior, the reality is more nuanced than ideology allows for. Throughout history there is a long tradition of powerful people who serve the group in some way being rewarded with more power still. Famous generals become Presidents (Washington, Grant, Eisenhower), not just because everyone knows their names but because they’ve proven their fortitude in battle and can prove it again if dangerous outsiders come calling. If you’re confused about Vladimir Putin’s stratospheric approval numbers at home even as he has made Russia an international pariah—at least in the eyes of the West—be confused no more.

We tolerate too the enormous wealth some inventors and industrialists accumulate because at least part of the time, they make our lives better too. (Thank you for the cars, Mr. Ford, and for the iPod, Mr. Jobs.) Admittedly, we’re a lot less tolerant when wealthy and powerful people create things that benefit only other wealthy and powerful people—(Thank you for, um, the $25 million condo that nobody I know will ever remotely be able to live in, Mr. Trump)—but we’d rather have an economy that rewards ambition than one that smothers it.

Free-riding is more complex than it seems as well. There’s truth to the fact that in the past, at least, welfare could be a disincentive to work, especially when the work that was on offer was unappealing (you try working a deep frier all day) and paid little more than the free money the government was giving you. But there’s a limit to that—especially when it comes to arguments against extending long-term unemployment benefits.

Under federal formulae, a weekly unemployment check tops out at 40-50% of your last paycheck. If you were grossing only $400 a week to begin with—and plenty of hourly workers don’t make even that much—that’s a cool $200 in benefits. How long could you lounge about in that hammock? On the other hand, health insurance free-riders—people who wait until they’re sick to sign up—do represent a real risk. So the only way to make sure everybody gets a fair shake is—oh, what do you call it again? Ah, yes: a mandate.

The behaviors we share with the lower apes are there for a reason: they worked when we were lower apes, and they still do. The plutocrats, the pampered, are necessary members of a complex economy, and calls for pure egalitarianism have always been nonsense. But so is the tough-love, pull-yourself-up, no free lunch even if you’re starving ethos of the people who have forgotten—or never knew—what that kind of desperation feels like. There’s not a thing wrong with the rich and powerful, provided that they remember what wealth and power are for. Blue-tailed monkeys and lemurs do—so how hard can it be?

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at [email protected]

Sample details

- Behaviorism

Related Topics

- Common sense

- Consciousness

- Absenteeism

- Individualism

- Masculinity

Greed: The Destroyer of Worlds

It is not inconceivable to state that greed is good in a world ruled by universal law. This would result in a perfect duty to refrain from acting on this. Excess money does not lead to happiness and the more money you have to more you want to earn more money. The economy would fall if people were going to live according to Gecko’s maxim. It is not rational to act on the “greed is good” maxim as it does not meet the requirements based on Step 2 and Step 3.

The maxim does not meet the requirements of Universal Law. Gecko’s speech would fit in with Nietzsche philosophy as it was driven by a sire to see human kind moving to higher and higher states of being. A quote from Gecko’s speech: “Greed, in all of its forms – greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge – has marked the upward surge of mankind. ” Nietzsche viewed morality as a dead end in human development and I am of an opinion that he would agree with Gecko’s views about greed.

ready to help you now

Without paying upfront

Gecko’s views would have also resonated Any Rand’s philosophies as she believed that self-interest was morally good. Her three central virtues were rationality, productiveness and pride and these virtues centre on selfishness and greed. As per Rand “sustaining life, one’s own life in particular, is the original objective standard of value. ” Not forgetting Adam Smith’s thinking about one’s own security, gains, interest and capitalistic views. I believe that self-interest and the pursuit to riches leads to greed.

Greed is socially destructive. The agents or law-making bodies of a country should have laws in place to handle the equitable distribution of wealth. Greed can lead to an economic melt-down as every individual will be pushing to make more money and their self-interest forgetting that we are living in a world with limited resources. Self-interest and egoism may lead to greed and that could be destructive. The agents should use the veil on ignorance to put proper policies in place on the amount of wealth individuals can amass.

All the inhabitants of planet earth should have fair and equal opportunities and at the same time take care of the environment we live in and living sensibly. This discussion links to the Sustainability assignment as greed according to my opinion is also the root cause of high ecological footprints in this planet. As individuals are consuming more resources than what our planet can provide for us. We should start living consciously and sustainable.

As individual move higher and higher the more resources they consume hence depleting the scarce resources the world can offer us. This course was an eye opener to me and I am planning to live a sustainable lifestyle going forward to ensure that the future generations will have resources to sustain them. As individuals we do not realize that our pursuit to “live more comfortable lives as we call it” have serious repercussions. We are chasing wealth, glamour and high statuses but at what cost? Is it all worth it?

Cite this page

https://graduateway.com/essay-greed-is-good/

You can get a custom paper by one of our expert writers

Check more samples on your topics

Adderall, the wonder drug or the destroyer.

The boy with ADHD did not introduce his girlfriend to any of his friends because he could not remember her name, similar to how a chicken with ADD never fully crosses the road due to distractions. ADHD is a developmental and behavioral disorder that affects 3 to 5 percent of all school-age children. According to the

Analysis of “The Visible and Invisible Worlds of Salem”

Salem Witch Trials

What is the author’s main theme? In Chapter 3 “The Visible and Invisible Worlds of Salem” in After The Fact the author discussed how “Over the past few decades historians have studied the traumatic experiences of 1692 in great detail”(52). The author talks about the Salem outbreak in New England and how bewitchment was related

Compare and Contrast Each Version of War of The Worlds

The version of War of the Worlds I found most effective in creating fear amongst its audience was the radio broadcast. In both the novel version and the radio broadcast the alien creature that lands on Earth are described in great detail. Its grotesque features are planted in our mind as the narrator tell us

Study of ‘Anne Hathaway’ from Carol Ann Duffy’s ‘The Worlds Wife’

How typical, in terms of language, style, structure and concerns is ‘Anne Hathaway’ of the collection? Carol Ann Duffy presents Anne Hathaway as a character who is deeply in love with her partner whom she is writing a poem for. This poem shows that the collection is not an act of revenge, as it shows how

Bridging the Two Worlds-the Organizational Dilemma

Organization

Everyone, including myself, has had a memorable experience that deeply impacted them. One day, when exams were approaching, I woke up early and went to the library. Unfortunately, it was crowded with people and there were no empty seats. So, I decided to leave my bag on the desk to reserve my spot and went

Innocence and Experience: Blake’s Contrasting Worlds

nnocence represents the ideal state and experience represents the reality'. Discuss this statement in the light of the poems you have studied so far. Blake's Songs of Innocence and Experience juxtapose the innocent, pastoral world of childhood against an adult world of disappointment and corruption. Yet, the two contrasting states are never fully separated in

“War of the Worlds” by HG Wells

The War of the Worlds was written in 1898 by HG Wells. It was written in the Victorian era. At this time, many people were questioning religion and exploring atheist ideas. Wells himself was an atheist and a socialist, so he had strong ideologies and many opinions on religious beliefs; especially with Christianity and Judaism. In

The Search For Other Worlds Extrasolar Planets

Earths Beyond Earth: The Search for Other Worlds In early 1990, the first extrasolar planet was detected, surprising everyone by its strangeness. More planets have now been discovered outside our solar system than in it. These planets present many great mysteries to the astronomical world. Extrasolar planets are planets that exist outside our solar system; they are

A Walker Between Worlds

Shamanism is a great mental and emotional journey that involves the shaman and the patients to transcend their normal, ordinary definitions of reality to a deeper level of consciousness. Shamanism is the sustenance of human vitality. It is a system of healing based on spiritual power from personal helping spirits whom the shaman encounters on

Hi, my name is Amy 👋

In case you can't find a relevant example, our professional writers are ready to help you write a unique paper. Just talk to our smart assistant Amy and she'll connect you with the best match.

Write an essay on Greed steals away wisdom

Explanation: Greed means to have an intense selfish desire to have something. Greed often destroys ones good judgement and the difference between right and wrong. Greed takes aways ones wisdom that means it can lead a person to callousness and arrogance. POINTS TO BE CONSIDERED - Greed has been identified as undesirable through human history because it creates conflict between personal and social goals. Greed does not allow one to think neutrally , it takes away all rational thinking . For eg- excess eating may lead to obesity, excess drinking can cause fatal illness. The same way greed for power and wealth can also be dangerous not just individually but also for society. Human are social and cultural animals , they will never be satisfied with whatever they have, they are always hungry for more. Human fail to realise that GREED MAKES THEM POOR. Greed can make people do strange things, even some unlawful acts. People see an opportunity to make more money through something they consider harmless , albeit illegal but then they get caught, face prison and destroy their careers. Greedy people usually hoard their possessions, never give to charity and stockpile their wealth. This is not a good way to manage money.They even wont hesitate stealing from people just to add a little more to their pile. Greedy people also sometimes end up in gambling . they want to see their money multiply and in the end they lose everything. The more people have, the more people want. Families break because of materialism, siblings go to court of matters of inheritance . They do such acts because they have lost all wisdom, they have no sense of judgement anymore. The root cause of greed is comparison with others, we should never compare ourselves with others and be content with what we have.

Write an essay on phloem

Essay on Greed Is Bad

Students are often asked to write an essay on Greed Is Bad in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Greed Is Bad

Greed: a short introduction.

Greed is a strong desire to have more of something, like money or power, than is needed. It is a bad trait because it can lead to many problems. Greed can make people selfish, dishonest, and hurtful to others. It can ruin relationships and cause unhappiness.

Impact on Personal Relationships

Greed can harm our personal relationships. If we are always wanting more, we might forget to appreciate what we already have. This can make us unhappy and make it hard for us to get along with others. It can also lead to feelings of jealousy and anger.

Effects on Society

Greed can also have a negative impact on society. It can lead to corruption, where people in power use their position for their own gain. This can harm the community and make it harder for everyone to succeed.

In conclusion, greed is a harmful trait. It can damage our relationships, make us unhappy, and harm society. It is important to be grateful for what we have and to treat others with kindness and respect.

250 Words Essay on Greed Is Bad

Introduction.

Greed is a desire to have more of something than you need. It is a harmful trait that can lead to many problems. This essay will explain why greed is bad.

Effects on Relationships

Greed can harm our relationships. When we want more than we need, we might start to take from others. This can make them feel used or unimportant. It can lead to fights and lost friendships.

Impact on Personal Growth

Greed can also stop us from growing as people. If we are always wanting more, we might not take the time to be happy with what we have. This can make us feel unsatisfied, even when we have a lot.

Consequences for Society

Greed is not just bad for us as individuals, but also for society. When people are greedy, they can ignore the needs of others. This can lead to inequality and injustice.

In conclusion, greed is a harmful trait that can damage our relationships, stop our personal growth, and harm society. It is important to be thankful for what we have, and to think about the needs of others. This will lead to a happier and more fair world.

500 Words Essay on Greed Is Bad

Greed is a strong desire to have more of something than you actually need. It can be for money, power, food, or anything else. Most of us are taught from a young age that being greedy is not good. This essay will explain why greed is bad.

Greed can have a negative effect on our relationships. When a person is greedy, they often think only about themselves and not about others. They may be willing to hurt others to get what they want. This can lead to fights and arguments with friends and family. It can also make people feel lonely, as others may not want to be around someone who is always thinking about themselves.

Impact on Society

Greed can also have a negative impact on society. When people are greedy, they can take more than their fair share of resources. This can lead to others not having enough. For example, if a person is greedy for money, they might not pay their fair share of taxes. This can lead to less money for schools, hospitals, and other important services.

Greed and Happiness

Greed can also make it harder for people to be happy. When a person is always wanting more, they may never feel satisfied with what they have. They may always be thinking about what they don’t have, rather than enjoying what they do have. This can make it hard for them to feel happy or content.

Greed and the Environment

Greed can also be bad for the environment. When people want more and more, they often use up more resources. This can lead to problems like deforestation, pollution, and climate change. These issues can harm animals, plants, and even our own health.

In conclusion, greed is bad for many reasons. It can hurt our relationships, society, and the environment. It can also make it hard for us to be happy. Instead of being greedy, we should try to be thankful for what we have and think about the needs of others. This can help us to live happier and more fulfilling lives.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Green Energy A Solution To Climate Change

- Essay on Green India Clean India

- Essay on Greenland

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Home — Essay Samples — Life — Greed — Discussion of Why Greed is Good for the Economy

Discussion of Why Greed is Good for The Economy

- Categories: Adam Smith Greed

About this sample

Words: 600 |

Published: Sep 1, 2020

Words: 600 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Works Cited:

- Cartwright, M. (2016). Women in ancient Greece. Ancient History Encyclopedia. https://www.ancient.eu/article/921/women-in-ancient-greece/