Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 13 July 2023

Mapping barriers to green supply chains in empirical research on green banking

- Teresa C. Herrador-Alcaide 1 ,

- Montserrat Hernández-Solís 1 &

- Susana Cortés Rodríguez 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 411 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

873 Accesses

2 Citations

Metrics details

- Business and management

The role of green banking (GB) in the green supply chain (CSC) is a relevant issue for green growth. The literature has pointed to some barriers identified as obstacles to the development of GSC. Since the publish of the framework of OECD for green growth, which is a reference for most of the countries, empirical research on GB has proliferated. Despite this, the barriers to the development of GSC have not yet been linked to empirical research on GB.Through a literature review of the empirical research on GB, this paper identifies by scientific impact the banking role, and we contribute with a mapping of the relationship among barriers to the development of GSC and conclusions of empirical research regarding GB, also considering the link with main topics of GB research. Additionally, it displays the main vectors related to area, year and methodology for each barrier and topic of empirical research on GB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Greenfield investment and job creation in Ghana: a sectorial analysis and geopolitical implications of Chinese investments

Daniel Assamah & Shaoyu Yuan

Promoting carbon neutrality and green growth through cultural industry financing

Hanzhi Zhang, Jingfeng Zhang & Chih-Hung Pai

Ways to bring private investment to the tourism industry for green growth

Fengxiao Gong & Hui Chen

Introduction

In 2009, a group of 34 countries signed a declaration of Green Growth, recognizing that “growth” and “green” can go hand in hand in order to add value to the sustainable development, resulting so the green growth strategies (OEDC, 2011 ). The green development links the growth of green businesses and innovation processes within green supply chain (GSC). The transition towards the GSC entails many difficulties (Zhu et al., 2005 ), that supposes the existence of barriers to GSC development. Despite the relevant role of the green banking (GB) for green growth, the seemingly abundant literature draws few conclusions about the contributions of GB to the GSC, and consequently, to the social value of the GB is not being sufficiently endorsed.

We have conducted a literature review to identify barriers to the development of CSG in the literature on GB, and draw qualitative conclusions about the evolution of research, since as Andrew Booth et al. ( 2012 ) indicate, a review of the literature must obtain qualitative conclusions.

Our work displays two types of contributions to green values. First, we contribute to cataloging of findings of empirical research on GB but associating them with the barriers to the development of GSC. Second, we contribute with an analysis of literature on empirical research on GB according to its scientific impact. Consequently, we map the barriers to CSG according to the scientific impact and relating it to the cataloging of topics on GB. Therefore, we can offer a perspective on the gaps and future lines in research on GB as a key agent in the development of GSC.

Our findings display relevant conclusions on how the empirical research on GB makes a proactive role or not for the development of GSC. Furthermore, we identify key differences on the research published by analyzing principal vectors in several dimensions of investigation.

After this section, the rest of the paper is structured as follows: Background, Method, Scientific production: sample and descriptives, Barriers to GSC identified in empirical research on GB, Mapping of scientific impact of empirical research on GB, and Conclusions, and suggestions.

The concept of GSC is also linked to the impact that supply chain causes on the environment (Beamon, 1999 ), that involves a set of processes (e.g., purchasing, manufacturing, marketing, logistics, etc.) in order to integrate customers satisfaction, efficiency, quality, and responsiveness (Zelbst et al., 2010 ). Thus, sustainability has been incorporated as an indispensable concept in supply chain (Seuring and Müller, 2008 ) to make socially and environmentally responsible business, that considers sustainable development, corporate social responsibility (CSR), stakeholder concerns, and corporate accountability (Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals, 2013 ). To achieve this goal, everyone plays their role, involving all economic agents in the sustainability of economic processes, that supposes the environmental sustainability as key concept to growth (Green et al., 2012 ; Seuring and Müller, 2008 ). The concepts of “sustainability” and “green going” are linked to the supply chain management (Srivastava, 2007 ), emerging the approach of GSC as a manner of integration of environment, sustainability, and performance in the supply chain. The integration of green initiatives implies the assumption of complete responsibility for the impacts of the different members of the chain (Kaur et al., 2018 ). Thus, each agent apport a value to contribute to the sustainable GSC, being necessary the understanding of business (Beltramello et al., 2013 ) and the different stakeholders´ roles (Meherishi et al., 2019 ).

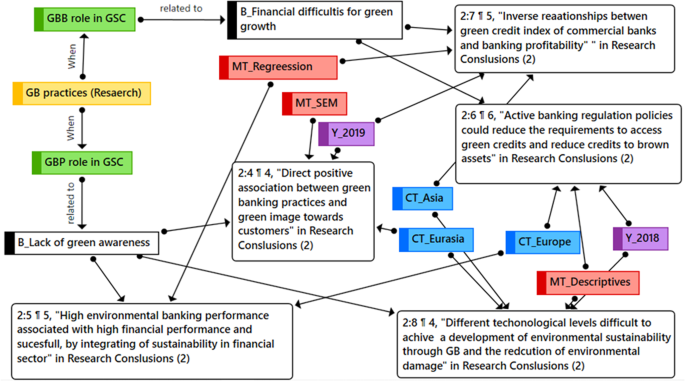

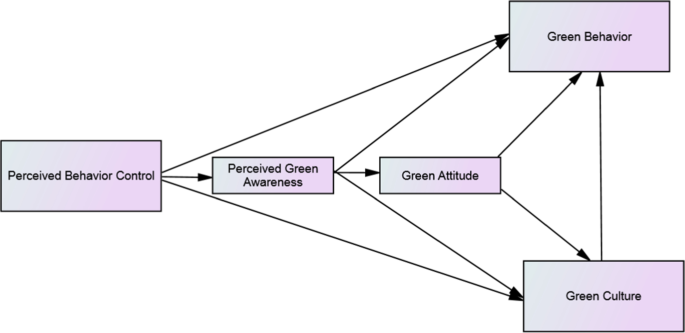

Considering GSC as the framework for sustainable development, on the one hand, GB can be considered as the company who implements pollution-free banking processes (GBP), that is, when a bank company works using less-polluting banking services. On the other hand, GB also can be considered as the bank company who makes green banking business (GBB), such as green investments or green credit, as a manner of providing the necessary financing for the GSC. Under this second approach, the term GB will include those bank companies with a business approach of financial products for the environmental sustainability. In this second one, the final objective of the green process is focused on the supporting of other members of GSC, being GB a mediator or driver of the green growth (see Fig. 1 ). This growth is associated with terms of sustainability and social ethics (Rao et al., 2015 ). Thus, banking can apport a determinant value for the eco-innovative business model (Beltramello et al., 2013 ). The absence of green financing causes that the managers must solve financial constrictions (Yang et al., 2019 ). Financial problems for green innovation are consider as a barrier for green growth (OEDC, 2011 ; Kaur et al., 2018 ; Sun et al., 2020 ), due to bank loans continue being the main sources of financing for some green companies (Belltramello et al., 3013), but the problems to access to this type of financing causes financial constrains (Kaur et al., 2018 ). It leads us to consider the analysis of GB as driver of green economy.

In literature, the GB plays two roles, one as any other industry trying to reduce its environmental footprint, and the other as a driver of GSC by facilitating the financing of green industries. Source: Authors.

Oher problem is the disclosure about sustainability in GB (Dissanayake et al., 2016 ), that could be linked to the problems of lack of environmental knowledge and environmental awareness (Kaur et al., 2018 ). Likewise, the lack of knowledge about the benefits of green business is associated with the lack of green commitment of some members of the GSC, such as bank companies or governments (Belltramello et al., 2013 ).

Thus, three groups of barriers have been identified, (1) those related to environmental knowledge, (2) the scarce of green awareness (linked to the lack of CSR), and (3) the problems to green production (Kaur et al., 2018 ) due to financial problems. Financial difficulties for green innovation are a real barrier (OECD, 2011 ), due to the financial risk that green investments entail (Sun et al., 2020 ; Wu et al., 2019 ; Yang et al., 2019 ) and consequently with effect on the real capacity to make green products.

According to the usual barriers to development of GCS and the key role of GB, we consider the following research questions (RQ):

RQ1: Can barriers to GSC development be identified in the empirical literature on GB?

RQ2: Can we identify which barriers to GSC development have received the most attention in research?

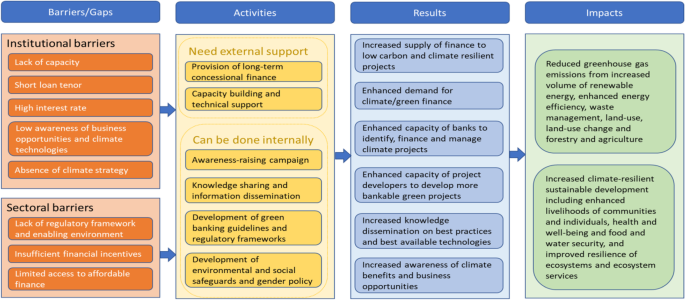

We use a systematic literature review (SLR), because according to Pierre Pluye et al. ( 2016 ) this research approach allows the categorization of qualitative-quantitative contributions to identify items and deficiencies in emerging issues of the economy (see see Masi et al., 2017 ; Meherishi et al., 2019 , and Munaro et al., 2020 ) for circular economy; Rashid and Ratten ( 2020 ) for entrepreneurship and innovation; or Gollapudi et al. ( 2019 ) and Queiroz et al. ( 2019 ) for financial technology and digital economy.

Nevertheless, this approach has not been applied to map the contributions of GB to the green growth as relevant value in the GSC.

To define stable thematic categories on the role of GB in green businesses, the present SLR was designed by considering the approach of Booth et al. ( 2012 ) and the Cochrane review protocol (Higgins and Green, 2011 ). Thus, various sequential phases were applied for the SLR (see Grant and Booth, 2009 ): selection and qualitative assessment of articles (phase 1), data systematization (phase 2), and data analysis (phase 3).

Selection and quality assessment of articles (phase 1)

We emphasize that according to the main objective of this work, which is the qualitative analysis of the empirical research on GB to identify barriers to the development of CSG, only the papers associated with the research terms “green” and “banking” are analyzed. For the inclusion we only selected those in which we could identify possible barriers to the development of CSG.

In the present SLR were included articles from ABI/INFORM and IsI Web of Science—Core collection (Thomson Reuters) and Scopus (Elsevier) databases—only published papers in English between 2011 and 2020 were included.

2011 was chosen as starting point because the OECD published in this year the document entitled “Towards green growth: A summary for policy makers” (2011). This document is considered as a real starting point for the development of the green economy under the current conception of sustainable economy (Bina, 2013 ). The disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has affected research objectives in all fields, including in the field of Economics, and specifically also in green banking. Therefore, the COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 period would not be comparable with the data series analyzed, which is why half of 2020 was taken as the end point of the paper series to be analyzed. On the other hand, there is not yet a sufficient post-COVID-19 data series to make a pre- and post-COVID-19 comparison in the green banking literature, from the approach of barriers to development of the GSC.

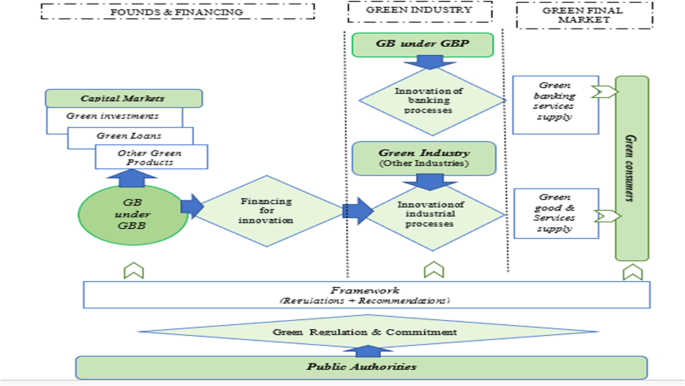

According to the research objective, in this phase, we applied a usual protocol for literature reviews. To perform a data quality screening, several actions were carried out to obtain a reliable database. In four steps: (1) Identification, (2) Screening, (3) Suitability, and (4) Inclusion (see Fig. 2 ).

The SLR has been developed in the usual steps, so that the process guarantees the verification and quality of the sample of resulting papers. Source: Authors.

For the step 1 (Identification) tow searches were made in databases, one in ABI/INFORM collection and other in Web of Science (WoS). The search path was in ABI/INFORM: /green AND banking/ abstract or title/English/article/Scientific reviews/peer review/2011–2020/full paper. The search in WoS was done in a similar way. Both according to Fig. 1 , ending the search on July 21, 2020. After identification and screening steps according to Fig. 2 , the data were tabulated and submitted to the check list. Thus, in the step 3 (suitability) articles that without an adequate indication on methodology, objectives, conclusions, and other relevant dimensions were eliminated. For this qualitative selection process, a triple-blind review of the 46 articles was carried out by each author. As result, in the step 4 (Inclusion) a whole of 30 articles met the requirements (see Supplementary Appendix I ). They provided conclusions on the relationship between green banking as part of GSC for green growth.

After step 3 (suitability), only 46 papers associated “green” and “banking” also considering the usual eligibility criteria (journals with quality signs, full paper, Economics Area, or Social Sciences). And more specifically the sample is specified in 30 works in step 4 (inclusion), considering furthermore only those that fall within the scope of the research objective (identification of barriers to the development of CSG in the conclusions of empirical research on GB). At this point, one might ask why it is interesting for the scientific community to review the literature within such specific parameters. It is precisely that we observe that the GB contributions to the GSC have not been associated to the research term “GB” yet. This is diminishing the visible value of the GB for the GSC, what’s both a limitation as a goal in terms of identifying research gaps. As in other reviews of the specialized literature whose objective is qualitative and not strictly bibliometric, the final sample is reduced to a small number of articles (Queiroz et al., 2019 ; Tseng et al., 2019 ).

Thus, our research is framed in the field of social sciences under the approach of Spash ( 2020 ), and it seeks to improve knowledge about GB-GSC in order to contribute to the social change of the economy, improving social welfare. In line with Bardsley ( 2020 ), we consider that social and ecological stimuli can redirect credit towards green infrastructure. This must be done from the different positions of each agent in the GSC, where undoubtedly the bank companies must develop a more proactive role. This in the long term must contribute to mitigating greenhouse gas emissions.

Data systematization (phase 2)

A coding template was designed in Microsoft Excel to provide an adequate coding for data treatment. This template included a whole of 19 fields. A questionnaire run play on 20% of the initially selected articles to verify the reliability of the template in a triple review (one by researcher) (see Supplementary Appendix I ). After filtering the results, the final coding template included 17 fields: Article ID (numbering assigned by researchers), paper´s name, year, authors, country authors, continent authors, country of empirical analysis, Continent of empirical analysis (GB location), research topic, GB approach within GSC, research objective, analysis methodology, type of data, identification of specific conclusions on green banking, conclusions on green banking research, journal, and database. Most of the fields were synthesized using numerical coding, but some of them required a summary narrative approach for the qualitative treatment of mapping of conclusions (Queiroz et al., 2019 ; Rumrill and Fitzgerald, 2001 ). To avoid bias, each author revised the coding made by the other authors.

Data analysis (phase 3)

For the qualitative analysis some fields were considered as primary fields, due to the objective of the research is to identify the real contributions of GB empirical research and making a map of the current research situation. Thus, the primary fields were research topic, country, methodology, year, and conclusion, following Masi et al. ( 2017 ) and Queiroz et al. ( 2019 ).

First, we analyze the relationships between several fields of the coding template by using the specific statistical analysis software (Statistical Package for Social Sciences Software—SPSS—-version 20.0) plus Excel for graphs. Second, we identified the similarities and differences in the conclusions related to GB regarding the barriers to GSC, by using a specific software for qualitative analysis (Atas.ti software). Thus, the research paper follows cross-sectional qualitative research with descriptive outcomes.

Limitations

This study performs the search by combining two databases (ABI/INFORM and WoS), selecting only bibliography in English, and in scientific quality journals (peer-reviewed), which guarantees the initial inclusion of relevant literature. However, as indicated by other authors, a limitation of this work could be the framework of the study (Roy et al., 2022 ), which is delimited by the GSC, which makes the analysis of empirical research on GB focus exclusively on papers whose conclusions of GB can be associated with some of the barriers to the development of CSG. This affects the number of articles finally selected for analysis. However, this objective is simultaneously an opportunity to develop research about relationship between the theoretical knowledge about CSG and the empirical knowledge about GB. The fact of use a small sample (with a small number of articles) does not affect the qualitative conclusions of the study, since it does not seek to carry out statistical inference. Even in quantitative analyses for modeling, a small sample size would not be sufficient to discard the results, as they could be showing valuable latent patterns (Everitt, 1975 ). In spite that the use of a sample size of 30 or more observations ensures a normal distribution of the sample in statistical terms, as it happens in our sample; some authors also indicate that the sample size cannot be considered strictly in statistical terms, since in exploratory phases it cannot be considered as a limitation to the approach of an investigation (Sapnas and Zeller, 2002 ; Mundfrom et al., 2005 ), even less so, when the literature review focuses on the narrative in order to obtain a qualitative synthesis of results. Despite the application of a protocol to systematize the study, it is not uncommon for different studies to obtain different results (Rodrigo, 2012 ). Therefore, the sample size of our study does not compromise our findings, taking into account that the sample selection was carried out following an internationally accepted systematization protocol. Nevertheless, the results must be interpreted with caution, within the theoretical framework of the work, which must be taken into account for its interpretation.

Scientific production: sample and descriptives

The GB research is considered as an interesting field (Queiroz et al., 2019 ) because it offers a way to analysis. However, green banking has not reached an equal level of technological processes even within the same country, so there is still a long way to go to achieve a development of environmental sustainability through green banking (Deka, 2015 ), highlighting its social responsibility in reducing environmental damage (Kondyukova et al., 2018 ). Thus, the company location is considered a key variable in economic research (Herrador-Alcaide and Hernandez-Solis, 2019 ), also for literature review in most of the research fields (e.g., Masi et al., 2017 ; Queiroz et al., 2019 ; Rumrill and Fitzgerald, 2001 ), and even more when the analysis is focused to identify differences, gaps and opportunities. As it is usual, we used location, year, and topic to frame the main descriptives of scientific production about empirical research on GB.

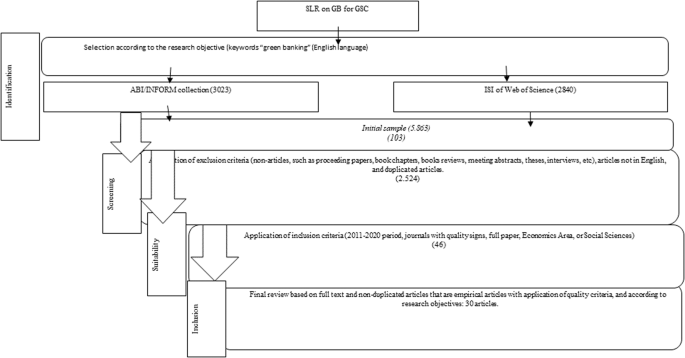

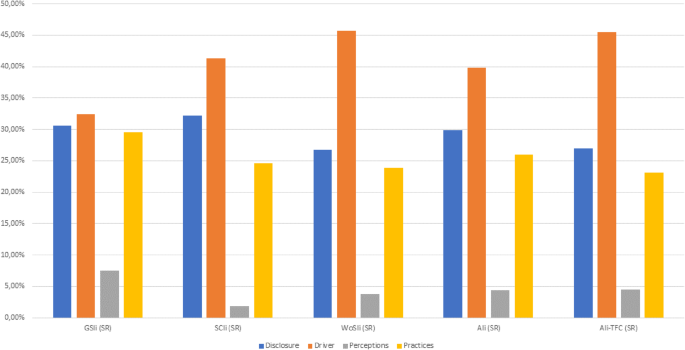

Figure 3 displays location of GB research by considering each research topic.

Figure 3 displays radial area by topic, continent and number of papers by authors´ location (first spider chart) and by the location of empirical research. Source: Authors.

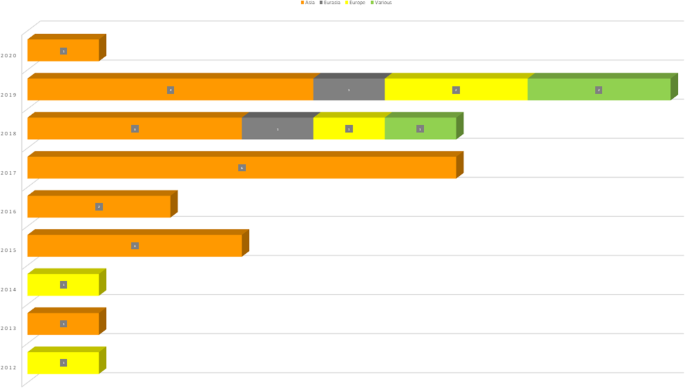

By considering the year, the largest scientific production is concentrated in 2019, and secondly in 2017 and 2018 (sea Fig. 4 ).

The geographical distribution based on the number of papers shows a greater scientific production in Asia in 2017. Source: Authors.

Additionally, we use methodology as other complementary vector to classify the status of scientific production, due to some methodologies as the descriptive statistic normally with secondary data (Masud et al., 2017 ) could be considered as first steps in research (Shampa and Jobaid, 2017 ), opposite to others as Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), that could be linked to a more advanced research phase (Tarka, 2018 ). Our sample displays majorly the use of descriptive methodology (the 46.66% of papers apply descriptive methodology) and only in the topic of GB disclosure the most used methodology is the regression analysis.

All the above shows the descriptive of the scientific production on GB of our sample, strictly considering the number of articles published in each topic, using as descriptives the geographical area (continent), the year of publication and the methodology. However, these descriptives based on the number of articles do not display the scientific impact of the publications, for which we have considered the citation criterion (see section on mapping by impact).

Barriers to GSC identified in empirical research on GB

The qualitative analysis of the research on GB was focused to the identification of the research lines by topic and their relationships with GSC barriers. This section shows our primer contribution through the identification of relationships between the GB and GSC. Furthermore, we identified also how GB could be or not a barrier for GSC. The analysis of relationships has been carried out by using the software, Atlas.ti. The findings are commented according to previous literature. It should be noted that for the qualitative analysis we have considered the location where the empirical analysis on GB has been performed, not the location per researcher (author), because our analysis focuses on discerning the barriers to the development of the GSC originated in the development of GB. Therefore, it does not make sense to link the results of the research to the location of the researcher, but to that of the continent on which the analysis has been carried out.

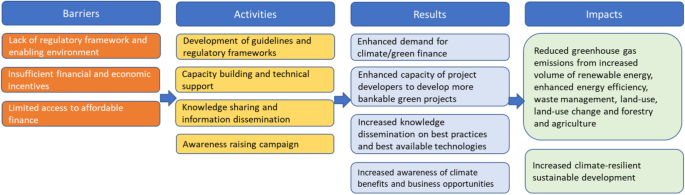

Barriers for GSC development in research on GB disclosure

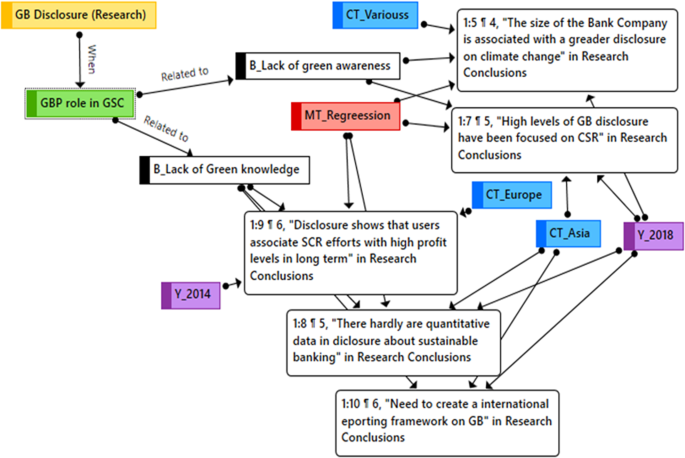

The literature on GB disclosure is mainly focused on GBP role. Thus, the value apported by GB to GSC is oriented to the banking process (see Fig. 5 ), being green disclosure associated to GB (Masud et al., 2017 ).

The GB disclosure in its GBP role is linked to two barriers, one for lack of green knowledge and another for lack of green awareness. Source: Authors.

Attending to the literature map on Gb disclosure (research conclusions)-GSC (barriers for) shown in the Fig. 5 , we identified the following qualitative connexions:

Some conclusions point out the lack of green awareness. The main line of conclusions relates the size of the bank company with levels of GB disclosure on climate change (Kılıç and Kuzey, 2019 ), but the reduction of carbon footprint and the saving of energy are hardly linked to the GB disclosure. The information is concentrated on board and ownership (Bose et al., 2018 ) and consequently on CSR. This line can be linked to the research carried out in 2018 in multiple countries.

Other conclusions point out the lack of green knowledge. When bank companies adopt voluntary guidelines for environmental performance, they disclose green qualitative information, but not quantitative data about sustainability (Kumar and Prakash, 2018 ). An international reporting framework (Masud et al., 2018 ) and the awareness of e-banking users (Lekakos et al., 2014 ) are necessary for the contribution of GB to the sustainable growth.

These barriers suppose that GB disclosure may be at an early stage, more focused on corporate image than a real accountability. Despite GB is starting to reduce this barrier through disclosure information on CSR for green management, however, the absence of quantitative data and heterogeneity in the content of the disclosure do not allow GB to show itself as a green member of the GSC.

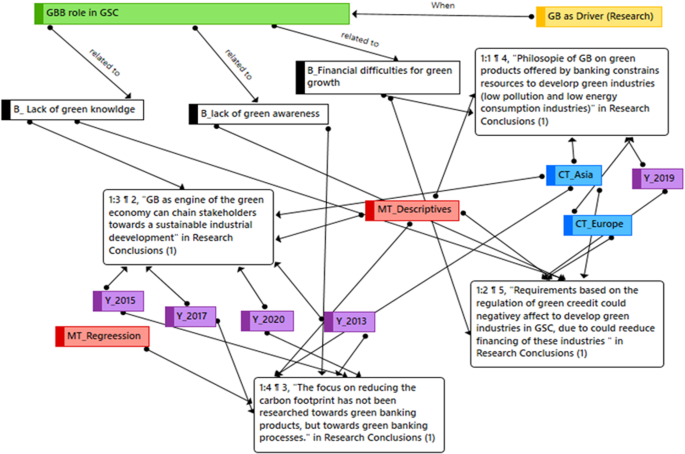

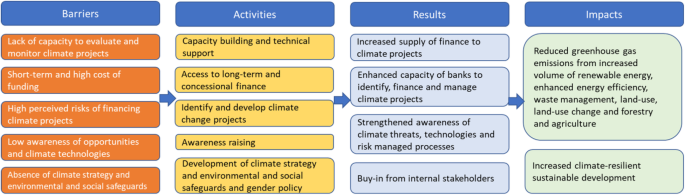

Barriers for GSC development in research on GB as driver of economy

We find that GB as driver of economy is focused mayorly on the GBB role. Thus, the GBB plays a key role for the development and sustainability (Manohar and Kumar, 2012 ; Ramila and Gurusamy, 2015 ; Islam et al., 2017 ; Miah et al., 2021 ), and reduction of pollution (Ramila and Gurusamy, 2015 ), but it is not free of barriers for de develop of GSC (Fig. 6 ). Green corporate performance, that it measured throughout CSR, is linked to green marketing strategies (Lymperopoulos et al., 2012 ).

The GB as driver of Economy in its GBB role is linked to all barriers for developing the GSC. Source: Authors.

Accordingly, we found three types of GSC barriers when GB literature is focus on GB as driver of economy:

Financial difficulties can cause a lower development of green growth (Miah et al., 2021 ; Radović-Marković and Živanović, 2019 ; Nieto, 2019 ; He et al., 2019 ; Julia and Kassim, 2019 ), because green regulation and financing policies maybe cause financial constraints in eco-industries. Regulation can hinder the distribution of bank credit for the green investment (He et al., 2019 ). This line of conclusions has been mainly analyzed in Asia and Europe, during 2019.

GSC barrier based on green unknowledge can be linked to two key conclusions. First conclusion shows that GBB can chain stakeholders towards sustainable industries (Manohar and Kumar, 2012 ; Miah et al., 2021 ), but other conclusion shows that a low GBB can be caused by the low knowledge of which must be the adequate green regulations to expand green growth. These barriers are concentrated in Asia, in a plurality of years, and they have been mainly identified by using descriptive analysis.

We can identify in the literature barriers based on lack of green awareness. Thus, literature shows that GBB research has not been able to associate reduction of pollution to GB products. The ecological offer of banking products is linked to banking philosophy of ethics and equity (Julia and Kassim, 2019 ), but transition to a low-carbon economy requires that banks integrate environmental risks into their governance systems (Nieto, 2019 ), being GB considered as a solution for the massive green infrastructure projects (Fashli et al., 2019 ). Also, green guidelines in countries and geopolitical context are necessaries (Julia and Kassim, 2019 ).

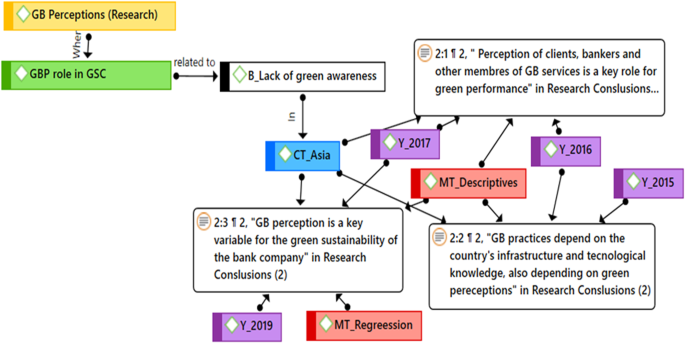

Barriers for GSC development in research on GB perceptions-

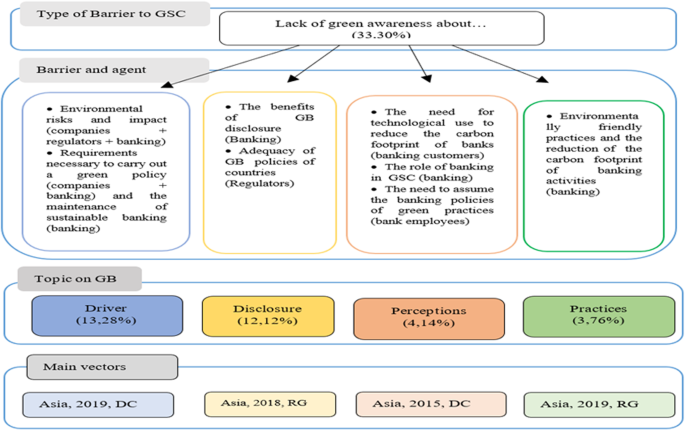

According to the map of qualitative conclusions of literature on GB perceptions (see Fig. 7 ), we found that the GB perceptions was researched under the approach of GBP.

The GB perceptions in its GBP role is linked to the lack of green awareness for developing the GSC. Source: Authors.

We found that main lines about GB perception could be linked to barriers for GSC based on the lack of green awareness. These barriers are mainly investigated within perception of clients about the use of green banking processes (Jatana and Jain, 2016 ; Jayabal and Soudarya, 2017 ), and how the massive acceptance of the GB practices depend not only on infrastructure and technology (Girish, 2016 ; Subramanian, 2015 ). It depends on the green behavior of banking staff (Girish, 2016 ; Mehedi and Maniruzzaman, 2017 ). Motivation is an important personal predictor of green performance in banking (Iqbal et al., 2018 ). Likewise, stakeholder perceptions are essential for the bank company’s sustainable development (Linh and Anh, 2017 ).

Barriers for GSC development in research on GB practices

We found that this research line on GB practice has been developed in the two GB roles: GBB and GBP. GB practices in GBB role are linked to barriers cause by financial problems for the green growth (see Fig. 8 ). The environmental banking performance has been associated with a larger financial performance (Laguir et al., 2018 ). Regarding the causality of this association, it has been found that the integration of sustainability in the financial sector does not harm financial performance but rather increases it (Weber, 2017 ). However, it has also been found that the green credit index of commercial banks is associated with an inverse relationship with their profitability (Song et al., 2019 ). As solution for this problem, a more active banking regulation could reduce the requirements that affect the cost of capital of green projects (Thomä and Gibhardt, 2019 ).

The GB practices in both roles (GBP and GBB), is linked to the lack of green awareness and lack of green financial resources for developing the GSC. Source: Authors.

GB practices on GBP role is linked to barriers by lack of green awareness. Several studies link GB practices with the sustainability of banking business, environmental commitment, social image, and manage of green practices. The location and temporal distribution of the studies, as well as the methodology used, is so diverse that we do not suggest possible associations. We must highlight that a direct and positive association was found between green banking practices and the green image (Ibe-enwo et al., 2019 ).

Considering previous maps with the qualitative identification of barriers considering these four topics on GB empirical research, the focus of GB concept is concentrated in GBP. According to this GB concept (GBP) and predominant topic of research on barriers to GSC (Lack of green awareness), we can point out that disclosure about GB has mainly focus on corporate image of banking and the capacity of disclosure in order to improve green knowledge of the agents within GSC.

These maps have implemented to define qualitative relationships among barriers to GSC and conclusions of empirical research on GB. Nevertheless, they should not be used to identify the priorities and gaps in the research, being necessary to carry out an analysis by scientific impact.

Mapping the scientific impact of empirical research on GB and barriers to GSC

The impact of research literature of each published article is commonly measured through the number of citations received by it. To collect appointments there are several search specialized engines. Among the most common are the Google Scholar (GS), the Web of Science (WoC) and Scopus (Sc). All of them collect automatically, reliably and systematically the citations received by the articles, papers and other research documents published although they measure the impact with different scope. While GS collects all citations received by publication in any database, WoC collects only those received in its database, and equally does Scopus. In order to measure the importance that research on GB has, all of the above are adequate. It could be interpreted that GS measures the impact for the generality, while WoC and Scopus measure a more relevant impact academically. To draw up our map of the state of empirical research on GB, we will use all three options.

Considering the total number of citations received in each of the bases, we build for each topic a relevance index of the topic by citations based on the following formulas:

Where GSC i , WoSI i, , and SCI i are the citation rates by base and topic, respectively. The numerator of each index represents the number of citations accumulated among all the papers published in a topic (i), while the denominator collects the total number of citations of all topics (all articles reviewed). In this way, the number of citations accumulated in each topic is relativized according to the total impact of the research analyzed. These indices are initially used to compare the scientific impact of the GB topics by comparing the three bases.

To determine a unique global impact that allows to relate barriers, topics and descriptive, we use an average index ( AIi ), which combines the different citation rates of each database, which ensures that we consider the impact in a broad sense. It is calculated as average of the citation indexes of each database. This average index allows us to apply a uniform measure to different aspects through the common measure of scientific impact per citation.

Correction of the time effect (age of publication) on the impact per citation

Table 1 shows the impact of each topic calculated based on citations. However, articles with a higher tenure (earliest date of publication) could have accumulated a greater number of citations just because of their longer publication time. In this way, if the effect of time on the AIi were not considered, a greater scientific interest could be attributed to older research whose greater volume of citations could be due more to the time effect than to a greater relevance for its interest to the scientific community. That is why we must consider the effect of time in the calculation of the impact per appointment. To do this, we built a correcting factor of the time effect. This correcting factor is based on the “Citation Rates” published in Field Baseline of InCitess Essential Science Indicators (Clarivate Analytics, 2023). From Clarivate’s Citation Rates we build an index to correct the AIi of each year, thus eliminating the effect of time on the citations received, which are placed in a homogeneous temporal context.

First, we construct a ratio that divides the Citation Rate (CRi) of each year by the Citation Rate of the base year (CR20). We take the last year of publication of the analyzed period (2020) as the base year for the conversion of the citations received by each paper to homogeneous values. Accordingly, the citation correction factor for the time elapsed since publication effect (TFCi) is constructed as: TFCi = CR i /CR20, where “ i ” corresponds to each year of the series. The CR i and CR20 corresponding to all the fields considered together are taken. TFCi allows the value of each AIi to be recalculated, transforming it into a homogeneous number in tenure to the average citations of the 2020 values, thus allowing the comparability of all the citations accumulated by the papers in the base year.

Second, the AIi-TFC is obtained as AIi-TFC = AIi/TFCi. In this way, the impact per appointment has been homogenized to average values of citations of 2020 (see Table 1).

Third, the sample rate (SR) is calculated, which is the proportion that each AIi-TFC represents over the 100% of the sample. The SR serves to compare the specific weight that the relevance by volume of citations (corrected for the time effect) has on the sample analyzed. In this way we can establish the appropriate priority among topics, barriers, and other vectors analyzed; neutralizing the effect of time on the scientific relevance attributed to the impact per citation.

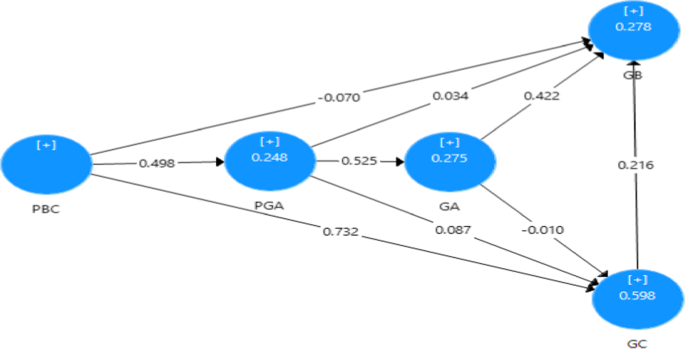

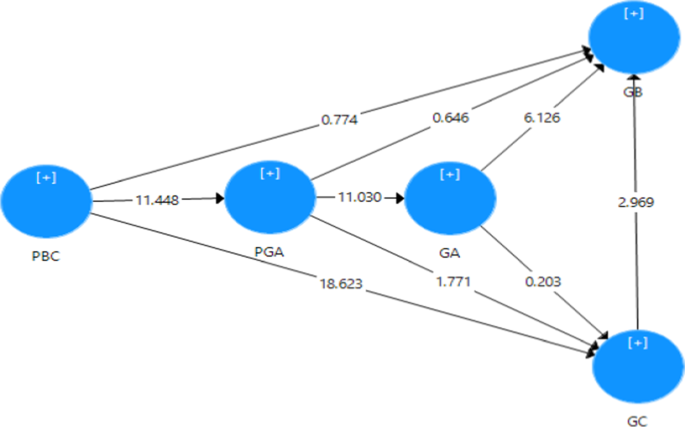

According of all above by considering the scientific impact measured by citations, Table 2 and Fig. 9 displays that GB as driver of economy is most relevant topic of the empirical research on GB in all indices. According to the average impact index of each topic (AIi), followed by the topic on GB disclosure, GB practices, GB perceptions.

The main topic by scientific impact is the GB as driver of GSC. Source: Authors.

When TFCi is applied to correct the time effect, the AIi-TFCi are 16.66%, 28.04%, 2.80%, and 14.24% for Disclosure, Driver, Perception, and Practices, respectively. This means that Disclosure, Driver, Perception and Practices have a specific relevance weight (SR) of 26.99, 45.42, 4.53, and 23.06% over 100% of the sample. It can be observed that by scientific impact by citation (isolated time effect) the order of most researched topics continues to be maintained as shown in Table 2 (Driver: 45.42%, Disclosure: 26.99%, Practices: 23.06%, and Perceptions: 4.53%).

It is observed that once the corrective factor of the time effect has been applied, the proportionality of the corrected cumulative citations does not affect the research preferences in terms of topics. This confirms that the method of analysis and the indices applied are a solvent tool for the measurement of scientific relevance calculated by citations, according to the objectives of the research.

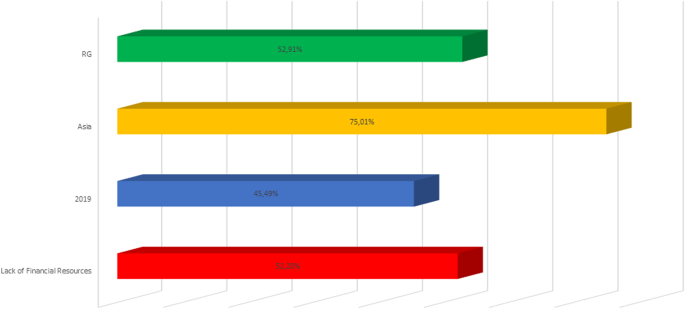

To identify the main vectors according to area, year, and methodology, we also use the SR (AIi-TFC) of each paper. According to Fig. 10 , Asia receives the 75.01% of citations, and the main temporal vector indicates that the year 2019 concentrates the 45.49% of citations. The main vector by methodology indicates that the 52.91% of the citations are for methodology based on regression models. The Lack of Financial Resources is the main barrier to GSC with the 52.20% of citations.

The main vectors considering the scientific impact are as continent Asia, as a method of analysis the regressions, as year 2019, and as a barrier the absence of financial resources. Source: Authors.

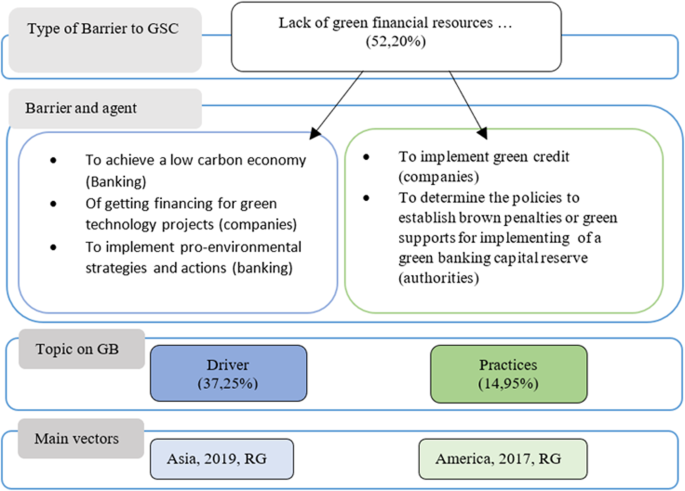

Mapping of barriers to GSC in empirical research on GB

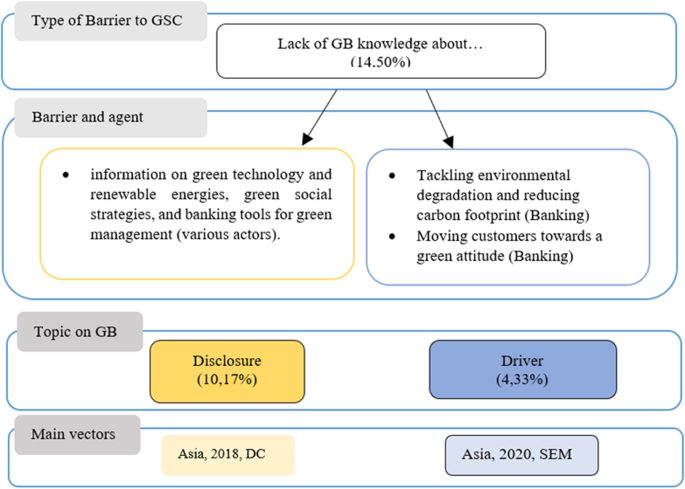

The specific weights of each barrier considering the AIi are 51.33%, 31.99%, and 16.68%, for the barriers of Lack of Green Financial Resources, Lack of Green Awareness, and Lack of Green Knowledge, respectively. The specific weights of each of the three barriers indicated by applying the time correction factor (SR for each barrier) are 52.20%, 30.30%, and 14.50%, respectively. It is observed that the adjustment of the specific weight of each barrier due to the accumulation of citations that could be due to the time effect is scarce. As in the topics, we can affirm that the differences in the scientific attention paid to each of the barriers is not due to a greater accumulation of citations by the age of the publication. Thus, the most relevant barriers corrected for the time effect remain in the same descending order: Lack of Green Financial Resources, Lack of Green Awareness, and Lack of Green Knowledge.

The results of scientific impact of each barrier, breaking it down by GB topics and their impact by the different types of descriptives (area, year, and methodology), once considered the time effect (see Table 3 ). So, we can identify the priorities by Relating barriers, topics, and descriptive, by considering their relevancy by scientific impact.

Accordingly, the most relevancy by scientific impact is focused first on the lack of green financial resources (52.20%), second on the lack of green awareness (33.30%), and thirdly on the lack of green knowledge (14.40%).

For the lack of financial resources, the main topic is GB as driver of economy (37.25%) and its main descriptives vectors are Asia (31.58%) / 2019 (31.19%) / RG (19.21%). For the second barrier to GSC (lack of green awareness), the main topic is driver (13.28%) and its vectors are Asia/2019/DC. For the third barrier, the main topic is disclosure (10.17%) and its main vectors are Asia / 2018 / DC.

In addition, Fig. 11 shows the conclusions for the barrier related to the lack of green financial resources, but also associating barrier with conclusions, topic, and main vectors by topic.

Regarding the lack of green financial resources, the main topic is the GB as driver of Economy. Source: Authors.

The barrier to GSC associated with the lack of green financial resources analyzed through the results of empirical research on GB, shows that barrier can be mostly associated with limitations found in the role that GB should play as an engine for green development. The conclusions of empirical research suggest that banking fails to drive its function towards goals related to the carbon-free economy. The research also leads to the conclusion that companies operating within the GSC indicate that the role of the GB is not allowing them access to financing for green projects, possibly because banks have not yet found adequate pro-environmental strategies in the performance of their role as conduits of financial resources.

Figure 12 indicates that the barrier due to lack of green awareness for the development of GSC, considering the scientific impact of empirical research on GB, is shown to be relevantly associated with problems in driving financial resources to GSC. The conclusions of the empirical research analyzed lead to limit the lack of green awareness around three agents: banks, companies, and regulators.

Regarding the lack of green awareness, the main topic is the GB as driver of Economy. Source: Authors.

For banks, the problem lies in how to insert environmental risk, so as to make it attractive to raise financial resources in the capital markets in order to direct them towards the needs of funds demanded by the companies that act in the GSC. As for regulators, the problem is how to make green policies that allow both establishing economic incentives for banks to attract resources and for companies to act in favor of green sustainability. For companies, the problem is limited access to green finance.

Figure 13 shows how in the empirical literature on GB the barriers to the development of GSC are relative to disclosure. Specifically, due to the lack of green knowledge associated with the absence of disclosure about technology to improve green production, the strategies for its implementation and banking management tools. This lack of disclosure that motivates ignorance would affect various economic agents, not only the banks themselves.

Regarding the lack of green knowledge, the main topic is the GB disclosure. Source: Authors.

Conclusions and suggestions

The degree of commitment of all sectors with green growth means that most companies are increasingly involved in the transformation towards non-polluting processes. In this green transformation, the empirical research can shed light on how GB role is adding value to GSC. According to literature, GB is hardly starting to finance the green growth.

The empirical research on GB can be grouped around 4 topics: GB as driver of green economy, Disclosure on GB, Perceptions on GB, and Practices of GB (They were coded as GB driver, GB disclosure, GB perceptions, and GB practices, respectively). Considering the scientific attention received, measured by the scientific input (by citations), the most relevant topic has been GB driver (45.42%), but with a near attention received for the topics GB disclosure and GB practices (26.99% and 23.06%, respectively). Scientific attention on perceptions related to GB has had little scientific impact. Considering the differentiation between the role of the GB as GBP or GBB, some papers have focused on research on GB as green banking processes (GBP) but considering the scientific impact the research have been majorly focused on green banking business (GBB).

By considering the barriers to the development of CSG identified in empirical research on GB, applying the scientific impact of publications, the most relevant barrier is that related to the lack of access to green financing, which accounts for more than 52.20% of scientific attention; compared to just over 33.30% and 14.50% for barriers due to lack of green awareness and green knowledge, respectively.

Regarding the relationships between barriers and topics, we found that in the literature analyzed the most relevant topics are the following: Lack of green financial resources-GB driver, Lack of green awareness-GB driver, and Lack of green knowledge-GB disclosure. In this barrier-topic context, no geographical area reaches a scientific interest higher than 33%, although Asia are revealed as the areas of greatest interest for scientific research. Also, by scientific impact, the most relevant year has been 2019 and the methodology more applied was regression (modeling).

Since the OECD declaration—“Towards green growth: A summary for policy makers”—(2011), the findings about what is relevant to the development found within the conclusions of the empirical research on GB, allow us to point out an initial mapping on how the role of the GB could be holding back green development. Nevertheless, our findings must be interpreted with caution, and must be considered in the research framework that combines the empirical research published related to GB and the theorization about barriers to GSC, because only those papers that are in this intersection allow to draw valid conclusions according to the research objective. Consequently, and despite complying with the protocols that guarantee quality literature review process, this does not exempt from the existence of other publications not adjusted to the criteria established for the research objective that could contain interesting conclusions about GB, but they are framed within other approaches.

Considering, our contributions within the research framework of present work, we may remark the following conclusions and suggestions:

The research on GB that has attracted more attention considering impact per citation is not conditioned by the age of the publication. This indicates that the relevant topics of scientific interest related to GB within the GSC are not linked to a specific temporal space, being these topics of interest in all the periods analyzed.

It would be interesting the extension of research about GB towards the GBB approach to improve the knowledge about GB as key support for developing the GSC. Accordingly, the analysis of GB should be considered under the role of banking products to finance green business. On the contrary, the GBP approach implies that green transformation of the bank processes in green process does not differ from other companies do. The mere digitalization of the bank processes is a common adaptation to a global market, but it does not suppose that banking takes a key role to develop the GSC.

Most research topics on GB should focus on measuring the effect that green investment and loans could have on the advancement of a cleaner industry for the expansion of the GSC. Maybe the focus could be directed towards cataloging associations between research results and the term GB.

The relevancy of the topic related to GB driver as a main topic in two of the barriers to the development of the GSC, shows how society needs to improve different aspects of the role of green banking business to build a financial bridge between those who offer economic resources and those who demand them. The lack of disclosure, understood as lack of accountability towards society, may be hindering the development of CSG due to lack of knowledge. Consequently, the measuring of GB disclosure and its modeling could be considered a relevant goal for future research.

The concentration of publications in the topic of GB as driver of economy point out to consider this topic as the main issue in future lines on GB research. According to barriers, they have been majorly focused on the barriers to the development of GSC based on lack of green financial resources and green awareness. A key idea for next research is the need to increase research from the perspective of the value that GB plays for the development of sustainable green growth, that is, when GB plays the role of promoter of GSC (GBB role), and how it should be channeled the necessary financing for the renewal of business models towards green business models.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), Madrid, Spain

Teresa C. Herrador-Alcaide, Montserrat Hernández-Solís & Susana Cortés Rodríguez

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors in the equal proportion collected and analyzed the data, designed the study, interpreted the results, carried out the implications, did the literature review, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Teresa C. Herrador-Alcaide , Montserrat Hernández-Solís or Susana Cortés Rodríguez .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Additional information.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary file, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Herrador-Alcaide, T.C., Hernández-Solís, M. & Cortés Rodríguez, S. Mapping barriers to green supply chains in empirical research on green banking. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10 , 411 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01900-x

Download citation

Received : 20 October 2022

Accepted : 28 June 2023

Published : 13 July 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01900-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Open access

- Published: 06 March 2020

Transition towards green banking: role of financial regulators and financial institutions

- Hyoungkun Park 1 , 2 &

- Jong Dae Kim 3

Asian Journal of Sustainability and Social Responsibility volume 5 , Article number: 5 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

72k Accesses

86 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper provides an overview of green banking as an emerging area of creating competitive advantages and new business opportunities for private sector banks and expanding the mandate of central banks and supervisors to protect the financial system and manage risks of individual financial institutions. Climate change is expected to accelerate and is no longer considered only as an environmental threat because it affects all economic sectors. Furthermore, climate-related risks are causing physical and transitional risks for the financial sector. To mitigate the negative impacts, central banks, supervisors and policymakers started undertaking various green banking initiatives, although the approach taken so far is slightly different between developed and developing countries. In parallel, both private and public financial institutions, individually and collectively, are trying to address the issues on the horizon especially from a risk management perspective. Particularly, private sector banks have developed climate strategies and rolled out diverse green financial instruments to seize the business opportunities. This paper uses the theory of change conceptual framework at the sectoral, institutional and combined level as a tool to identify barriers in green banking and analyze activities that are needed to mitigate those barriers and to reach desired results and impacts.

Introduction

The latest IPCC report (IPCC 2018 ) reaffirmed that human activities caused global warming and are likely to further accelerate it by reaching 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels between 2030 and 2052 based on a business-as-usual scenario. The IPCC report set highly ambitious targets of reducing global net anthropogenic CO 2 emissions by approximately 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 and reaching net zero around 2050 to meet 1.5 °C of global warming. Limiting global warming to 1.5 °C certainly requires social and business transformations and emissions reductions across all sectors. Whilst the National Climate Assessment (USGCRP 2018 ) was more limited in scope by focusing its findings on the United States, it reached similar conclusions and suggested measures to reduce risks through emissions mitigation and adaptation actions. These findings prove that there is still a long way to go despite negative impacts arising from climate change and global warming (Doran and Zimmerman 2009 ; Cook et al. 2013 ).

To achieve such a structural transformation, the magnitude of the investment required is enormous. The IPCC report projected USD 2.4 trillion in clean energy is needed every year through 2035 and between USD 1.6 and USD 3.8 trillion in energy system supply-side investments every year through 2050, which is equivalent to USD 51.2 and USD 122 trillion exclusively for energy investments. Considering the significant investment needs, the financial sector is expected to play a pivotal role in providing necessary financial resources as it is the backbone of the real economy (OECD 2017 ). The role of the banking sector is central in meeting financial needs of the private sector and delivering credit to households and individuals (Beck and Demirguc-Kunt 2006 ; Wang 2016 ). The banking sector also plays a critical role in supporting a country’s adaptation to climate change and enhancing its financial resilience to climate risks. Banks can help reduce risks associated with climate change and sustainability, mitigate the impact of these risks, adapt to climate change and support recovery by reallocating financing to climate-sensitive sectors.

Climate change is affecting the financial system because of its far-reaching impact across all sectors and geographies, and the high degree of certainty that risks will emerge and have irreversible consequences if no actions are taken today. However, climate-related risks are not yet fully assessed and factored into current valuation of assets (NGFS 2019 ). The role of banks in financing the transition to a green economy is to unlock private investments, to bridge supply and demand while considering the entire spectrum of risks and to evaluate projects from both an economic and environmental perspective (EBF 2017 ). Although several banks have demonstrated their leadership in financing green or climate projects, the green portfolio of most banks is still very low. The International Finance Corporation (IFC) estimated the total green loans and credits of banks in developing countries to the private sector in 2016 to be approximately USD 1.5 trillion, or about 7% of total claims on the private sector in emerging markets (IFC 2018a , 2018b ). This outcome results from both a lack of the necessary regulatory and supervisory framework and failure to integrate environment and climate change risks into banks’ strategies and risk management systems. Additionally, the current financial framework often makes the required investment difficult to be met due to barriers exist at the sectoral and institutional level (Mazzucato and Semieniuk 2018 ). In response to the lack of regulatory and supervisory framework, a growing number of central banks and regulators around the world are becoming aware of their role and potential mandate in addressing climate change and environment risks faced by the banking and financial sector and taking actions (Volz 2017 ). For example, a group of central banks and supervisors launched the Networking for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) in 2017 to contribute to the analysis and management of climate and environment-related risks in the financial sector, and to mobilize mainstream finance to support the transition toward a sustainable economy (NGFS 2018 ). In parallel, more banks, especially private sector commercial banks, have started greening their operations by integrating environmental and climate change risks into their strategies and risk management systems and rolling out green financial products to expand their business horizons.

While green banking is still a new concept in the field of climate finance, it can serve the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)‘s objectives by financing climate change mitigation and adaptation activities in collaboration with the private sector. This paper aims to identify the challenges that climate change presents to the financial sector and describes and analyzes various tools for financial institutions that can help manage climate and credit risks while developing business opportunities in parallel.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 introduces the topic of green banking and reviews the relevant literature. Section 3 shows the green banking initiatives being undertaken by central banks and regulators and recent discussions about the mandates of central banks in their efforts to make the bank’s operations green and sustainable. It will also analyze the key difference in the approaches taken by developed and developing countries. This is followed by a discussion of the range of strategies, policies, tools and instruments that are being adopted and deployed by banks and presents the framework in Section 4. Section 5 introduces the theory of change conceptual framework as a tool to analyze current barriers and gaps, activities to be performed to mitigate the barriers and expected results and impacts that can be created. The final section discusses implications for academia, policy makers and practitioners and provides directions for future research.

Overview of green banking

Definition of green banking.

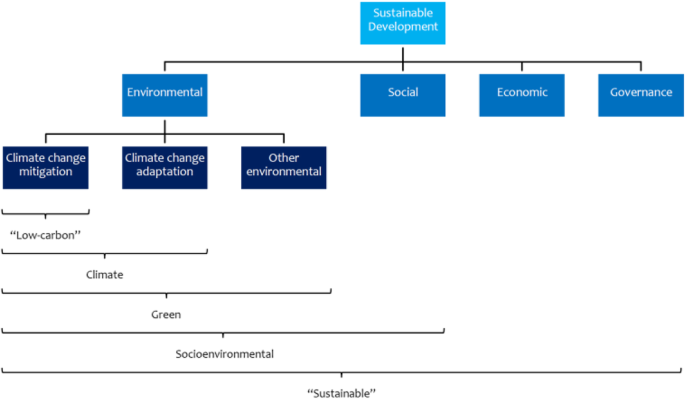

There is no universally accepted definition of green banking (Alexander 2016 ) and it varies widely between countries. However, some researchers and organizations tried to come up with their own definition. The Indian Institute for Development and Research in Banking Technology (IDRBT), which is established by the Reserve Bank of India, defined green banking as an umbrella term referring to practices and guidelines that make banks sustainable in economic, environmental and social dimensions (IDRBT, 2013 ). Green banking is similar to the concept of ethical banking, which starts with the aim of protecting the environment, as it involves promoting environmental and social responsibility while providing excellent banking services (Bihari 2011 ). The State Bank of Pakistan defined green banking as promoting environmentally friendly practices that aid banks and customers in reducing their carbon footprints (SBP 2015 ). Green banking can be also called social or responsible banking because it covers the social responsibility of banks towards environmental protection, illustrating that social issues often intersect with environmental issues. Social banking is broadly defined as addressing some of the most pressing issues of our time and aiming to have a positive impact on people, the environment and culture by meaning of banking (Kaeufer 2010 ; Weber and Remer 2011 ). Similarly, responsible banking encompasses a strong commitment by banks to sustainable development and addressing corporate social responsibility as an integral part of its business activities. Finally, green banking can be a subset of sustainable banking which tends to capture broader environmental and social dimensions (Dufays 2012 ). Global Alliance for Banking on Values (GABV) is an independent network of banks and banking cooperatives with a shared mission to use finance to deliver sustainable economic, social and environmental development. GABV has endorsed the principles of sustainable banking which include triple bottom line approach (social, environmental and financial aspects) at the heart of the business model, grounded in communities and transparent and inclusive governance (GABV 2012 ). There are many overlaps between these definitions and concepts which can be confusing to some extent. To make the scope and definitions a little clearer, UNEP provided a good comparison on respective definitions of green vs. sustainable vs. socioenvironmental (UNEP, 2016 ), as shown in Fig. 1 . According to UNEP, sustainable finance is the most inclusive concept which contains social, environmental and economic aspects while green finance includes climate and other environmental finance but excludes social and economic aspects.

A simplified schema for understanding broad terms. Source: UNEP, 2016

Whilst the definition of green finance in the UNEP paper was used to address environmental concerns in general and therefore became broader than the definition of climate finance, the scope of this paper will only apply to banking activities related to climate change mitigation and adaptation. In this respect, the concept of green banking is similar to that of climate finance defined by the UNFCCC which refers to finance that aims at reducing emissions and enhancing sinks of greenhouse gases and aims at reducing vulnerability of, and maintaining and increasing the resilience of, human and ecological systems to negative climate change impacts. In this paper, green banking is defined as financing activities by banking and non-banking financial institutions with an aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and increase the resilience of the society to negative climate change impacts while considering other sustainable development goals such as economic growth, job creation and gender equality.

Need for green banking as a risk assessment and management tool

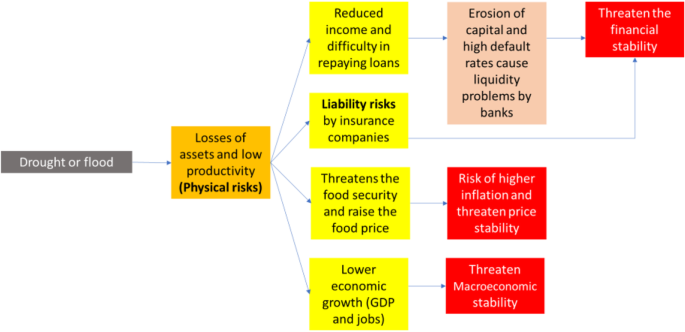

IPCC rightfully claimed that there is no clear scientific evidence on how the banking sector will be affected by the impacts of climate change (IPCC 2001 ). Whilst there may not be clear scientific evidence, central banks, regulators and the academia have been analyzing the climate change challenges from a financial risk and stability point of view (Kim et al. 2015 ; Carney 2015 ; Battiston et al. 2017 ; Volz 2017 ). Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) within the Bank of England identified two primary financial risk factors associated with climate change: physical and transition (PRA 2018 ). Physical risk is defined as the first-order risks which arise from climate and weather-related events, such as floods, storms, heatwaves, droughts and sea-level rise with the vulnerability of exposure of human and natural systems (PRA 2015 ; Batten et al. 2016 ; PRA 2018 ). Physical risks can lead to higher credit risks and financial losses by impairing asset values. Transition risks are those that can arise while adjusting, frequently in a disorderly fashion, towards a low-carbon economy (Carney 2015 ; Platinga and Scholtens). Given that climate change mitigation actions often require radical changes and adjustments by the public and private sector and households, a large range of assets are at risk of becoming stranded. This is especially prevalent for fossil-fuel related sectors and assets, which as a result of a revaluation, can in turn lead to higher credit exposure for banking and non-banking financial institutions. Additionally, liability risks can be another primary financial risk factor. Liability risks can arise if parties suffering losses from the damages of climate change seek compensation from those they hold accountable (Heede 2014 ; Carney 2015 ). Liability risks can be more relevant to the insurance sector rather than banking sector due their nature and compensation mechanism. The three types of financial risk factors constitute a major threat to the stability of the financial system (Carney 2015 ; Arezki et al. 2016 ; Christophers 2017 ).

Those risks can come in parallel as they are interdependent. For example, an agriculture-dominated economy can suffer in many ways. Drought or flood, which is a physical risk, can lead to direct losses in agriculture and other agriculture- and food-related value-added sectors. Such a damage in turn can trigger liability risks if their properties were insured. Extreme weather events will not only reduce incomes generated by those sectors but also hamper economic growth by lowering the gross domestic product (GDP) and affecting the job market and thus threaten macroeconomic stability. As a result, affected corporates and individuals may not be able to repay their loans. Once loan default rates increase, banks with heavy agriculture portfolios will suffer. Ultimately, the stability of the whole financial system can be threatened. Additionally, changes in agricultural input can affect food security and food prices which in turn can influence the inflation rate and threaten price stability (Heinen et al. 2016 ). Figure 2 shows an example of climate change affecting in an agriculture-dominant economy.

Climate change effects in an agriculture-dominant economy

For banking and non-banking financial institutions, the transition risks of policy changes can cause more immediate and serious consequences compared to the other two types of financial risks, especially from a credit risk perspective. For example, valuation of collaterals such as land and properties may have to be downgraded if the governments decide to give up on coastal lands and properties vulnerable to sea-level rise for economic reasons or introduce more stringent building energy efficiency standards. Additionally, more extreme hot weather can decrease agricultural productivity leading to lower valuations. Borrowers in the tourism sector relying on coral ecosystems are likely to suffer from a significant decline of coral reefs of 70–90% under a 1.5 °C global warming scenario. Those banks that hold such collaterals and assets would be expected to reserve more capital against them or require more collaterals to offset the shortfall and manage the probability of default and loss-given-default which will become a financial burden by borrowers. Many banks have high exposure to carbon-intensive industries whose business models may not fit into the transition to a low-carbon economy. As a result, the borrowers in the carbon-intensive sector may face challenges in repaying loans due to a decrease in their earnings and asset value. As a result, more banks can be under pressure to shift their investment and lending patterns by divesting from fossil-fuels and investing more in low carbon and energy efficient technologies.

Additionally, the climate risk factors may increase market and operational risks for banks. Market risks can arise from significant fluctuations in energy and commodity prices due to the transition on carbon-intensive industries. Coupled with weakened macroeconomic conditions such as inflation and economic growth, these market risks can increase transaction costs for banks. Banks may also have to bear higher insurance risk premiums on their own assets vulnerable to climate change. Operational risks associated with business continuity can also increase due to climate change and frequency and depth of extreme weather events. For example, banks may have to relocate their headquarters and data centers. Reputational risks by banks could also arise from investing in carbon-intensive assets and borrowers as some might view such activities as breach of fiduciary duty for failing to consider long-term investment value drivers (Table 1 ).

Banks have increasingly started assessing the risks associated with exposure to their loans by adopting risk management frameworks such as the Equator Principles, which are essentially a credit risk management tool that can be used to identify, evaluate and manage environmental and social risks in project finance transactions. However, many frameworks like the Equator Principles are voluntary, legally non-binding industry benchmark and demonstrated inherent limitations including limited scope, a lack of transparency and publicly disclosed information, inadequate monitoring and a lack of accountability, liability, implementation and enforcement (Wörsdörfer 2016 ).

Arguably, the most effective means to address those issues would be to make such tools more enforceable within the boundary of the regulatory and prudential frameworks, assuming that most banks would not voluntarily undertake such measures. However, with exceptions of a few countries such as Bangladesh, China and Indonesia, most countries have just started exploring this possibility. In the case of China, the People’s Bank of China and the China Banking Regulatory Commission developed Green Credit Guidelines based on their Banking Industry Regulation and Administration Law and Commercial Banking Law. China’s Green Credit Guidelines require that banks establish a monitoring and evaluating system for green credit. The effectiveness of such policies is not easy to measure, and they are mostly still in mixed form between voluntary guidelines and enforceable regulations. Nonetheless, even voluntary guidelines can provide a very strong signal to banks if they come from central banks and supervisors, or organically from banks themselves, and are expected to encourage banks to assess and manage credit risks which may transit from climate risks.

Some argue that green loans possess better credit quality than non-green loans, particularly in terms of a lower non-performing loan (NPL) ratio (Weber et al. 2010 , 2015 ; Cui et al. 2018 ). On the other hand, NGFS conducted a preliminary stock-taking of research on credit risk differentials in terms of default rates and NPL ratio between green and non-green assets and concluded that there were no potential risk differentials (NGFS 2019 ). Existing data gaps is one of the factors that make a conclusion difficult to be drawn. Simply put, there isn’t much data available in this field given this is still a very new area and it’s been only a few years since countries and banks have started analyzing the potential risk exposure. Consistent and reliable data covering the credit exposure to climate risks and risk-return profiles of green and non-green assets over a sufficient period of time is needed (NGFS 2019 ).

The role of central banks and financial regulators in responding to climate change challenges

Debates on the role of the central banks and financial regulators.

As the financial risks from climate change are becoming more apparent and relevant to the banking sector, a growing number of central banks and financial regulators are taking them more seriously (Monnin 2018 ). NGFS members also acknowledge that climate-related risks are becoming financial risks and therefore taking care of climate risks is within the mandates of central banks and supervisors (NGFS 2018 ). Prior to the launch of the NGFS, the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) and the G20 Sustainable Finance Study Group, which was formerly known as G20 Green Finance Study Group, were established to serve similar objectives. The TCFD was established by the Financial Stability Board, which is an international body that monitors and makes recommendations about the global financial system, with an aim to develop voluntary, consistent climate-related financial risk disclosures that would be helpful to investors, lenders, insurance companies and asset managers in identifying and managing financial risks (TCFD 2017 ). Similarly, the G20 Sustainable Finance Study Group was created to identify barriers to green finance and improve the financial system to mobilize private capital for green and sustainable investment (G20 Green Finance Study Group 2017 ). While these kinds of frameworks and industry-led initiatives are major drivers of innovation and risk management, the public sector, namely central banks and financial regulators, also must play a supporting role in mainstreaming green finance and making sure climate-related risks are properly measured, verified and reported. However, many central banks are still reluctant to ease capital requirements for green lending without clear evidence that green finance indeed carries lower risks. Many debates are now arising regarding the climate change and environmental mandate of central banks and financial regulators (Volz 2017 ).

According to the statutes of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), a central bank is defined as the bank that has been entrusted the duty of regulating the volume of currency and credit in the country. Central banks have historically had three main functional roles, which are to maintain price stability and financial stability, to support a country’s financing needs at times of crisis and to constrain misuse of its financial powers in normal times (Goodhart 2010 ). Additionally, central banks are often required to contribute to stabilizing exchange rate, creating jobs and fueling economic growth (Barkawi and Monnin 2015 ). Central banks often act as financial regulators that define the rules for banking and non-banking financial institutions such as the minimum capital requirement and specific restrictions on certain types of lending. However, there are other cases where an independent supervisory authority is established with the power of financial regulations and supervision while a central bank solely focuses on the monetary policy. The recent financial crisis between 2007 and 2008 indeed accelerated and expanded the role of central banks as the guardian of the financial system and as a lender of last resort. In this respect, the main job of a central bank is to control inflation and macroeconomic and financial stability. Thus, in a narrow sense evaluating climate-related risks and adjusting its monetary and macroprudential policies accordingly can be seen as overstepping its mandate. Volz ( 2017 ) also described potential conflicts with core objectives and mandates of central banks, overstretching their powers and resistance within the central banking community by incorporating the green objective in the mandate of central banks. Additionally, there is a question on the legal mandate of central banks. Some central banks in developing countries such as the Bangladesh Bank, the Banco Central do Brasil and the People’s Bank of China are active in pursuing green central banking policies and explicitly included sustainability in their mandate (Dikau and Ryan-Collins 2017 ). Also, the Financial Services Authority (OJK), the financial market regulator in Indonesia, has safeguarding financial system stability as a foundation of sustainable development in their corporate objectives and subsequently launched a roadmap for sustainable finance in 2014 and regulation on sustainable finance in 2017 (OJK 2014 ; OJK 2017 ). However, such an environmental sustainability mandate is relatively ambiguous for those in developed countries. For example, Article 127 (1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union defines price stability as the main objective of the European System of Central Banks (ESCB). Although some rely on Article 3 (3) of the Treaty on European Union, which states that the European Central Bank (ECB) shall support the general economic policies in the Union including a high level of protection and improvement of the quality of the environment, to argue that the ECB already integrated the environmental sustainability in its mandate; however, it is still considered as a secondary objective of the ECB and thus there is room for different interpretations. One study found that 54 out of 133 central banks have a mandate to spearhead sustainable economic growth or support sustainability goals set by the government but their mandates are not explicitly linked to climate change (Dikau and Volz 2019 ). To sum up, most central banks have focused on its interventionist role in the world’s economies since the financial crisis and they have not made significant adjustment of their policies to support a low-carbon transition (NEF 2017 ).