- Keyword Search

- Browse by Track

- Sessions Home

A Comprehensive Approach to Eating Disorders: The Future of Practice

The registered dietitian nutritionist is essential in the treatment of eating disorders. This session will leave you engaged, entertained, and inspired to integrate the newly published Standards of Practice and Professional Performance for Eating Disorders from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics into your clinical practice.

This interactive case-study presentation will include topics such as culinary medicine therapies, legislative advocacy, advancing educational offerings, and impact of nutritional neuropsychology on feeding behaviors. Attendees will offer live feedback through audience polling to guide the course of treatment throughout the presentation. Practical lessons in professionalism and medical ethics from veterans in the field of eating disorder treatment will also be discussed. Furthermore, attendees will gain essential training necessary for all RDNs who will encounter this population in practice–especially those seeking specialization.

Learning Objectives:

- Describe variations of clinical responsibilities between the RDN, CEDRD, and CEDRD-S in the treatment of eating disorders through an interactive case study.

- List three unintentional clinical nutrition interventions that impair eating disorder recovery.

- Design comprehensive MNT and biopsychosocial treatment intervention for an individual engaged in recovery from an eating disorder using a holistic, multidisciplinary approach.

Performance Indicators:

- 9.2.4 Collaborates with learner(s) and colleagues to formulate specific, measurable and attainable objectives and goals.

- 6.2.4 Disseminates research or performance improvement outcomes to advance knowledge, change practice and enhance effectiveness of services.

- 10.1.3 Works collaboratively with the interdisciplinary team (including NDTRs) to identify and implement valid and reliable nutrition screening to support access to care.

Moderator(s)

Melainie Rogers, MS, RDN, CDN, CEDRD-S

Founder and CEO

BALANCE eating disorder treatment center

Megan Kniskern, MS, RD, LD/N, CEDRD-S

MAK Nutrition Services

.jpg)

Tammy Beasley, MS, RDN, CEDRD-S, CSSD, LD

Vice President, Clinical Nutrition Services

Alsana Eating Recovery Communities

April Hackert, MS, RDN, LD, CEDRD-S

Psychiatric Culinary Medicine Research Dietitian

Choose to Change Nutrition Services

Nutrition knowledge of people with eating disorders

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Human Nutrition, Faculty of Public Health in Bytom, Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland

- 2 Student Scientific Team at the Department of Human Nutrition, Faculty of Public Health in Bytom, Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland

- PMID: 30837745

- DOI: 10.32394/rpzh.2019.0053

Background: Eating disorders are an increasingly common health problem that is a major therapeutic challenge. For many years, the basic form of therapy used to be psychiatric and psychotherapeutic treatment, but now it is postulated that the dietetician should also be part of the therapeutic teams.

Objective: The main purpose of the study is to assess nutrition knowledge of people with eating disorders with consideration to their age, place of living, education, BMI, type of disease, participation in dietary consultations and in therapy.

Material and methods: Nutrition knowledge of the respondents was assessed by means of an author’s survey questionnaire. The questionnaire was published in one of the social portals in the “Eating disorders – tackling” group gathering people with different types of eating disorders. The survey questionnaire consisted in 33 questions. Arithmetic mean and standard deviation for the number of correct answers provided by the respondents by the selected criteria.

Results: In terms of age, the least nutrition knowledge was attributable to the persons below 20 years of age (25.24 points in average). When considering the place of living, the least nutrition knowledge was revealed among the subjects living in medium cities (between 20 and 100 thousand of population) i.e. 25.31 points. In terms of education, the least nutrition knowledge was recorded in people with vocational education (24.83 points). When classifying the respondents by BMI, the highest average score was gained by the respondents with normal body mass index (BMI) (26.42 points).

Conclusions: The study on the level of nutrition knowledge among the people with eating disorders demonstrated that this knowledge was selective and insufficient to provide rational nutrition. It aimed at teaching the rules of healthy lifestyle and nutrition and thorough discussing of all nutrients, their functions and effect on the body.

Keywords: nutrition knowledge; eating disorders; lifestyle.

- Age Factors

- Feeding Behavior / psychology*

- Feeding and Eating Disorders / prevention & control

- Feeding and Eating Disorders / psychology*

- Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice*

- Nutrition Surveys / statistics & numerical data*

- Nutritional Status

- Surveys and Questionnaires

- Young Adult

- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, mastery is associated with weight status, food intake, snacking, and eating disorder symptoms in the nutrinet-santé cohort study.

- 1 Sorbonne Paris Nord University, Inserm U1153, Inrae U1125, Cnam, Nutritional Epidemiology Research Team (EREN), Centre of Research in Epidemiology and Statistics - University of Paris (CRESS), Bobigny, France

- 2 Counseling Psychology, Department of Psychology, University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany

- 3 CNRS, EconomiX – UMR 7235, University of Paris Nanterre, Ivry-sur-Seine, France

- 4 INRAE, UR 1303 ALISS, Ivry-sur-Seine, France

- 5 Paris School of Economics and INRAE, UMR1393 PjSE, Paris, France

- 6 Grenoble Alpes University, INRAE, CNRS, Grenoble INP, GAEL, Grenoble, France

- 7 Department of Public Health, AP-HP Avicenne Hospital, Bobigny, France

Mastery is a psychological resource that is defined as the extent to which individuals perceive having control over important circumstances of their lives. Although mastery has been associated with various physical and psychological health outcomes, studies assessing its relationship with weight status and dietary behavior are lacking. The aim of this cross-sectional study was to assess the relationship between mastery and weight status, food intake, snacking, and eating disorder (ED) symptoms in the NutriNet-Santé cohort study. Mastery was measured with the Pearlin Mastery Scale (PMS) in 32,588 adults (77.45% female), the mean age was 50.04 (14.53) years. Height and weight were self-reported. Overall diet quality and food group consumption were evaluated with ≥3 self-reported 24-h dietary records (range: 3–27). Snacking was assessed with an ad-hoc question. ED symptoms were assessed with the Sick-Control-One-Fat-Food Questionnaire (SCOFF). Linear and logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess the relationship between mastery and weight status, food intake, snacking, and ED symptoms, controlling for sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics. Females with a higher level of mastery were less likely to be underweight (OR: 0.88; 95%CI: 0.84, 0.93), overweight [OR: 0.94 (0.91, 0.97)], or obese [class I: OR: 0.86 (0.82, 0.90); class II: OR: 0.76 (0.71, 0.82); class III: OR: 0.77 (0.69, 0.86)]. Males with a higher level of mastery were less likely to be obese [class III: OR: 0.75 (0.57, 0.99)]. Mastery was associated with better diet quality overall, a higher consumption of fruit and vegetables, seafood, wholegrain foods, legumes, non-salted oleaginous fruits, and alcoholic beverages and with a lower consumption of meat and poultry, dairy products, sugary and fatty products, milk-based desserts, and sweetened beverages. Mastery was also associated with lower snacking frequency [OR: 0.89 (0.86, 0.91)] and less ED symptoms [OR: 0.73 (0.71, 0.75)]. As mastery was associated with favorable dietary behavior and weight status, targeting mastery might be a promising approach in promoting healthy behaviors.

Clinical Trial Registry Number: NCT03335644 at Clinicaltrials.gov .

Introduction

Psychological factors are linked to overweight and obesity ( 1 ), eating disorders (ED) ( 2 ), and dietary intake ( 3 , 4 ). In recent decades, research on psychological factors has shifted from assessing negative and pathological factors to positive factors ( 5 ). Positive factors can be easily targeted in interventions [with e.g., goal setting or using personal strengths ( 6 )] and represent important avenues to foster health over and above the absence of illness ( 7 ).

Mastery is defined as the extent to which individuals perceive having control over important circumstances of their lives ( 8 ). It is a psychological resource that helps individuals to cope with life events and life strains ( 9 ). Mastery is not regarded as a stable personality trait but as an adaptive self-concept that changes with critical experiences ( 10 ). As mastery is considered a modifiable factor ( 11 ), it may be a potential facilitator in promoting healthy dietary behavior.

Previous research has shown that mastery is associated with various physical health outcomes including better cardiometabolic health ( 10 , 12 , 13 ) or reduced mortality risk ( 12 , 14 ) as well as psychological health outcomes including higher self-esteem ( 13 , 15 ), sense of coherence ( 13 , 16 ), life satisfaction ( 16 ) and lower depression ( 15 , 17 ). However, research on the relationships between mastery and weight status as well as dietary behavior remain scarce and inconsistent. With regard to the relationship between mastery and weight status, different studies have found a negative relationship in both males and females ( 10 , 15 ), a positive relationship in male students ( 18 ) and no relationship in females ( 18 – 20 ) or males ( 19 ). Only a few studies investigated the relationship between mastery and food intake and revealed inconsistent results. Mastery was positively associated with the Healthy Eating Index and several of its indicators ( 21 ) in a large population. However, other studies showed no association between mastery and diet quality ( 22 ), fat or fiber intake ( 23 ) while there were inconsistent results regarding fruit and vegetable consumption ( 24 ). To our knowledge, no study has investigated the relationship between mastery and snacking. As frequent snacking can be seen as a maladaptive coping behavior to deal with stressors ( 25 , 26 ), it is conceivable that individuals who snack frequently, unlike those who do not snack frequently, show lower levels of mastery. Previous results regarding the relationship between mastery and EDs revealed a negative association between mastery and the overall level of eating pathology ( 20 ), binge eating ( 19 ) as well as weight concern, shape concern and eating concern ( 27 ). However, females with and without an ED reported a similar level of mastery ( 20 ).

To better understand the role of mastery with regard to dietary behavior, more research is needed, especially in a large population. Many studies on mastery have been conducted in specific populations, e.g., students, clinical populations or older adults, and do not consider potential confounders. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to investigate the association between mastery and weight status, diet quality, food group consumption, snacking and ED symptoms in a large sample of French adults, taking into account sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics.

Materials and Methods

Population and study design.

To conduct this study, we used data of the NutriNet-Santé study. The NutriNet-Santé study was launched in France in 2009 and is a large ongoing web-based prospective cohort study in the French population ( https://etude-nutrinet-sante.fr/ ). It aims at examining the relationship between nutrition and health as well as investigating determinants of dietary patterns and nutritional status in adults aged ≥18 years ( 28 ). At inclusion, participants were asked to fill out web-based questionnaires assessing diet, physical activity, anthropometric measures, lifestyle characteristics, socioeconomic conditions, and health status. Participants were asked to fill out this set of questionnaires every year after inclusion. Furthermore, participants were asked every month to complete another set of optional questionnaires assessing determinants of eating behavior, nutritional status and specific health-related aspects. Please see the study protocol for further information regarding the methodology and design ( 28 ).

Instruments

Mastery was assessed with a translated French version of the Pearlin Mastery Scale (PMS) ( 9 ). The PMS was once administered between May and November 2014. Responses to its 7 items were recorded on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 ( totally disagree ) to 7 ( totally agree ). Item scores were summed and then divided by the number of items, leading to a score ranging from 1 to 7. Higher mean values reflect higher levels of mastery. Previous studies have found support for the scale's validity and reliability ( 16 , 29 ).

Weight Status

BMI was assessed with self-reported height and weight. BMI (in kg/m 2 ) was calculated as the ratio of weight to squared height. Anthropometric data provided closest after completion of the PMS were used. Participants were categorized as underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m 2 ), normal weight (18.5 kg/m 2 ≤ BMI <25 kg/m 2 ), overweight (excluding obesity) (25 kg/m 2 ≤ BMI <30 kg/m 2 ), obese class I (30 kg/m 2 ≤ BMI <35 kg/m 2 ), obese class II (35 kg/m 2 ≤ BMI <40 kg/m 2 ), and obese class III (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m 2 ) ( 30 ).

Diet Quality and Food Group Consumption

At inclusion and every 6 months afterwards, participants were asked to complete a set of three 24-h dietary records (randomly distributed between 2 weekdays and 1 weekend day). Individuals who completed ≥3 24-h dietary records in the time-frame of 2 years before and 2 years after the completion of the PMS were selected for the present study. The number of completed 24-h records ranged from 3 to 27. An interactive web-based interface allowed the participants to complete the dietary record on their own by choosing among >3,500 food or beverage items ( 31 ). Participants were asked to report all foods and beverages consumed at mealtimes (breakfast, lunch, dinner) and other eating occasions. They estimated the amounts consumed using standard measurements or validated photographs ( 32 ). To assess portion sizes, participants had to choose between 7 categories for most food products: 3 main portion sizes, 2 intermediate portion sizes and 2 extreme portion sizes. Based on the NutriNet-Santé food composition table ( 33 ), nutrient intakes were estimated. Mean daily food intake (grams/day) was weighted according to weekday vs. weekend. We used the method proposed by Black ( 34 ) to identify participants with unlikely estimates of energy intake as under-reporters. We calculated the basal metabolic rate according to age, sex, weight, and height by using Schofield's equations ( 35 ). Based on basal metabolic rate and the level of physical activity, we determined energy requirement. We calculated the ratio between energy intake and estimated energy requirement and excluded individuals with ratios below the Goldberg cutoff ( 36 ). The validity of the dietary records in the NutriNet-Santé study has been shown by comparing the dietary records with biomarkers ( 37 , 38 ) and with interviews by a dietitian ( 31 ). For this study, we defined 19 food groups: fruit and vegetables, seafood (fish and shellfish), meat and poultry, processed meat, eggs, dairy products (e.g., milk, yogurts with ≤ 12% of added sugar), cheese, milk-based desserts (e.g., flan, milk shakes), starchy foods, wholegrain foods, legumes, fats (e.g., oil, butter), sugary and fatty foods (e.g., cakes, chocolate, ice cream, pancakes), sugar and confectionery (e.g., honey, jelly), fast food (e.g., pizzas, hamburgers, quiches), appetizers (e.g., chips, salted biscuits, salted oleaginous fruits), non-salted oleaginous fruits (e.g., non-salted nuts, non-salted almonds), sweetened beverages (sugary sweetened beverages and artificially sweetened beverages) and alcoholic beverages.

To assess diet quality, we used the modified French National Nutrition and Health Program Guideline Score (mPNNS-GS) which is an a priori diet quality score, reflecting the adherence to the French nutritional recommendations that were in effect at the time of the PMS measurement ( 39 ). It is based on the PNNS-GS score, however, it only accounts for the dietary component while excluding the physical activity component ( 39 , 40 ). The mPNNS-GS includes 12 components: 8 components refer to food serving recommendations (fruit and vegetables; starchy foods; wholegrain foods; dairy products; meat, eggs, and fish; seafood; vegetable fat; water and soda) and 4 components refer to moderation of intake (added fat, salt, sweets, and alcohol). For overconsumption of salt, overconsumption of added sugars from sweetened foods and when energy intake exceeds energy requirement [based on the level of physical activity level and basal metabolic rate ( 35 )] by > 5%, the score will be reduced. The maximum of the mPNNS-GS are 13.5 points, with higher scores indicating a better diet quality.

Between April and October 2014, a meal pattern questionnaire was administered. Snacking was assessed with one question (“How often do you usually snack in the daytime?”). Responses were recorded on a 7-point scale ranging from never to 6 times or more per day, each day and classified into 4 categories: never, < once a week, ≥ once a week (and < than once a day), or ≥ once a day. Further, we computed a binary variable: no snacking vs. snacking.

Eating Disorder (ED) Symptoms

ED symptoms were assessed with the French version of the SCOFF (Sick-Control-One-Fat-Food) questionnaire ( 41 ). The SCOFF was administered between June and December 2014. It includes 5 dichotomous items (yes vs. no) that cover the main features of EDs ( 42 ). A cut off ≥2 indicates ED symptoms (regardless of type). Previous studies support its reliability and validity and its suitability as a screening tool for EDs ( 43 , 44 ). In the current sample, McDonald's omega (ω) as an index for reliability ( 45 ) was 0.550, 95% CI [0.540, 0.561]. Furthermore, we used the Expali algorithm that allows to distinguish between ED categories ( 46 ). Based on the answers given in the SCOFF and the individual's BMI, the Expali algorithm classified individuals with ED symptoms into 4 broad categories. These categories were based on the DSM-5 ( 47 ): (1) restrictive disorders including anorexia nervosa, restrictive food intake disorder and atypical anorexia nervosa; (2) bulimic disorders including bulimia nervosa and bulimia nervosa of low frequency or duration; (3) hyperphagic disorders including binge-eating disorder and binge-eating disorder of low frequency or duration; and 4. other ED including purging disorder, night eating syndrome and any other ED.

Guided by previous studies, we collected data on potential confounders of the relationship between mastery, weight status, diet quality, food group consumption, snacking and EDs. Covariates were assessed at inclusion and once a year. We used the data provided closest to the date of the completion of the PMS. Selected covariates were as follows: age (years), sex, educational level (primary, secondary, undergraduate, and postgraduate), occupational status (unemployed, student, self-employed/farmer, employee/manual worker, intermediate profession, managerial staff/intellectual profession, and retired), monthly income per household unit (<1,200; 1,200–1,799; 1,800–2,299; 2,300–2,699; 2,700–3,699; ≥3,700 euros per household unit, and “unwilling to answer”), smoking status (never, former, and current smoker), level of physical activity (low, moderate, and high), and depressive symptomatology (yes, no). The covariates were determined as follows: we determined monthly income per household unit with information about income and household composition. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development equivalence scale, we converted the number of people in the household into number of consumption units: 1 consumption unit is attributed for the first adult in the household, 0.5 for other persons aged ≥14 years, and 0.3 for children aged <14 years ( 48 ). We determined physical activity with the short form of the French version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire ( 49 ). We estimated energy expenditure expressed in metabolic equivalent of task minutes per week. With that, we categorized the 3 levels of physical activity [low (<30 min/d), moderate (30–60 min/d), and high (≥60 min/d)]. We assessed depressive symptomatology by using the French version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression (CES-D) scale ( 50 , 51 ). Responses to its 20 items were recorded on a 4-point scale, with higher values indicating higher depressive symptomatology. A cut off ≥16 indicates a depressive symptomatology ( 51 ). In the current sample, McDonald's ω was 0.910, 95% CI [0.908, 0.912].

Data Analysis

To compare the characteristics of included with excluded participants, we performed Student t -Tests for continuous variables and Pearson's chi-square tests for categorical variables. We assessed the reliability of the French version of the PMS by calculating McDonald's omega (ω) ( 45 ). To test the factor structure of the PMS, we performed a one factor confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The following fit indexes with cut-off values for a good model fit were used to evaluate model fit: comparative fit index (CFI) ≥0.95, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.06, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) ≤ 0.08 ( 52 ). To investigate the relationship between mastery and participants' characteristics, we used Spearman correlation coefficients (with 95% CI) for continuous variables and Student t -test or ANOVA for categorical variables. Depending on the variable level (categorical/continuous), we reported participants' characteristics and descriptive characteristics of outcomes either as percentages (%) or means (M) and standard deviations (SD). Medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were used for non-normally distributed intake of food groups. To investigate the relationship between mastery (independent variable, IV) and weight status (dependent variable, DV), we performed multinomial logistic regressions. Only these analyses were stratified by sex because the interaction between mastery and weight status was the only interaction between mastery and a DV that was significant ( p = 0.005). To investigate the relationship between mastery (IV) and diet quality (DV) as well as normally distributed intake of food groups (DV) (fruit and vegetables, seafood, meat and poultry, dairy products, cheese, starchy foods, wholegrain foods, fats, sugary and fatty foods, sugar and confectionery), we performed multiple linear regressions. To investigate the relationship between mastery (IV) and non-normally distributed intake of food groups (DV) (processed meat, eggs, legumes, fast food, milk-based desserts, non-salted oleaginous fruits, appetizers, sweetened beverages, alcoholic beverages), we performed multinomial logistic regressions. For these groups, we defined three levels: no intake vs. low intake (< median intake among consumers) vs. high intake (≥median intake among consumers). To investigate the relationship between mastery (IV) and snacking (DV), we performed binary logistic regressions (snacking vs. no snacking) as well as multinomial logistic regressions with four frequency categories (never vs. < once a week vs. ≥ once a week vs. ≥ once a day). To investigate the relationship between mastery (IV) and ED symptoms (DV), we performed binary logistic regressions (ED symptoms vs. no ED symptoms) as well as multinomial logistic regressions with the four ED categories (no ED vs. restrictive disorder vs. bulimic disorder vs. hyperphagic disorder vs. other ED). From logistic regressions, we estimated the strength of the associations by the calculation of adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). All analyses were performed with (adjusted model) and without (unadjusted model) confounding variables. The adjusted model included age, sex, educational level, occupational status, monthly income per household unit, energy intake, smoking status, and physical activity. The analyses between mastery and food groups further included the number of 24-h dietary records as a confounding variable. Further, we computed a sensitivity analysis adding depressive symptomatology to the models. To handle missing data on covariates, we used multiple imputation by fully conditional specification (20 imputed data sets). All tests of statistical significance were 2-sided and significance was set at 5%. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Inc.), except for McDonald's ω that was calculated with the MBESS R package (version 4.8.0).

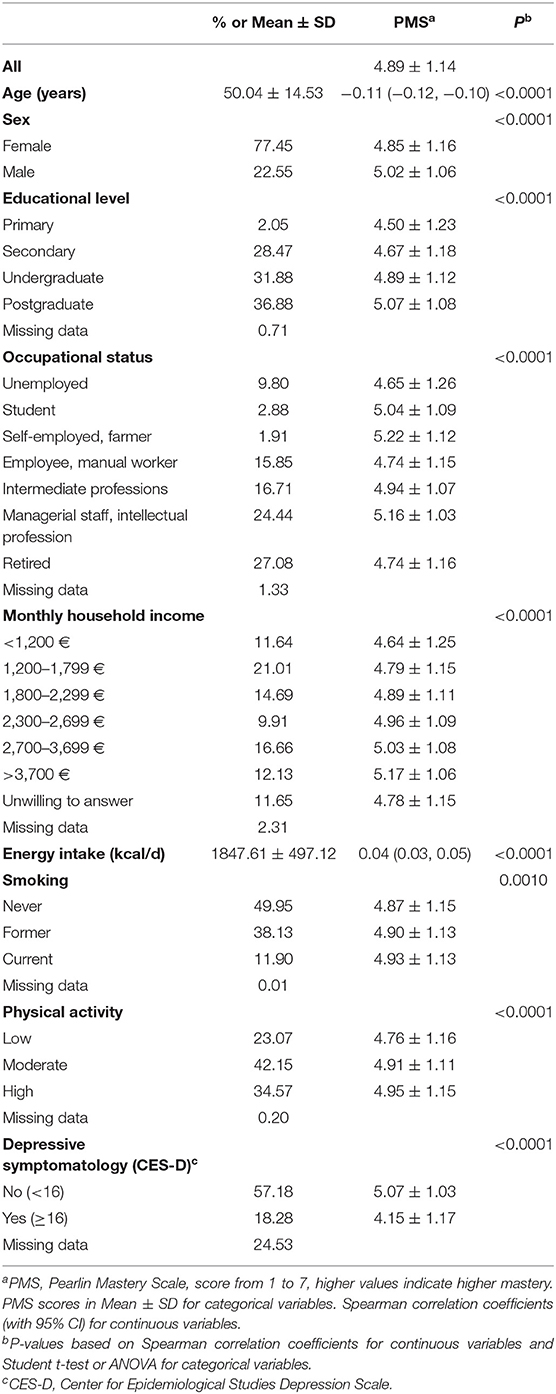

Sample Characteristics

Of the 139,420 subjects who were included in the NutriNet-Santé study in 2014, 33,017 participants completed the PMS. We excluded 148 participants due to an acquiescence bias (i.e., agreeing or disagreeing with all statements without consideration of the reverse-worded items) and 281 participants who were pregnant, resulting in 32,588 participants eligible for analysis. Among those, 30,620 participants also completed the snacking assessment, 30,339 participants reported anthropometric data, 28,951 participants completed the SCOFF, 25,024 participants had available data to assess diet quality and 22,209 participants had data on food group intake (see Supplementary Figure 1 ). To make better use of available data, we performed each analysis on a different subsample. Compared with excluded participants of the NutriNet-Santé cohort who did not complete the PMS or were excluded due to an acquiescence bias or pregnancy, included participants were older, had a higher proportion of males, a higher educational level and income (all p < 0.001). Table 1 presents the individual characteristics of the overall sample and their relationships to level of mastery. On average, mastery was higher in males, in more educated participants, in self-employed/farmers and managerial staff/intellectual professions, in participants with a higher income, in smokers, in participants with a higher physical activity and in participants without depressive symptomatology. Mastery was negatively associated with age and positively associated with energy intake. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the outcome variables.

Table 1 . Individual characteristics of N = 32,588 participants (NutriNet-Santé cohort study, 2014).

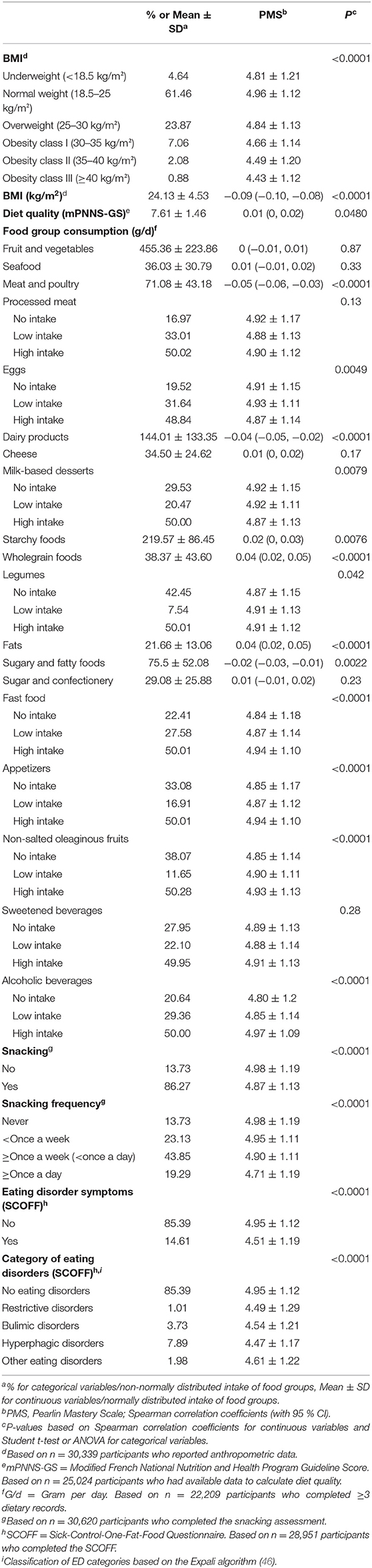

Table 2 . Descriptive characteristics of the outcome variables (NutriNet-Santé cohort study, 2014).

Psychometric Properties of the PMS

In the overall sample ( N = 32,588), McDonald‘s ω was 0.842, 95% CI [0.839, 0.845], supporting the reliability of the PMS. The CFA with mastery as the single common factor provided the following fit indices: CFI = 0.917, SRMR = 0.058, RMSEA = 0.126, 90% CI [0.124; 0.129], χ 2 (14, N = 32,588) = 7273.454, p < 0.0001. This indicates a good value of SRMR and an adequate value of CFI, but an unsatisfactory value of RMSEA. Except for item 6 that showed a satisfactory factor loading (0.40), all other items showed high factor loadings (0.50–0.84).

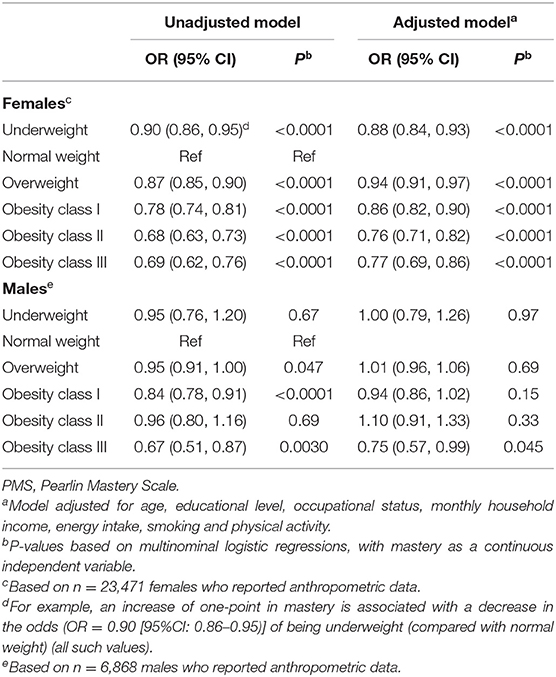

Relationship Between Mastery and Weight Status

Table 3 shows the results of the logistic regression models between mastery and BMI categories. In the adjusted model, females with a higher level of mastery were less likely to be underweight, overweight or obese (all classes) than females with a lower level of mastery. ORs were the lowest in females with obesity, in particular obesity class II and III. In the adjusted model, males with a higher level of mastery were less likely to be obese (class III) than males with a lower level of obesity. There was no significant association between mastery and underweight, overweight, obesity class I and II. An additional model was tested with depressive symptomatology taken into account as a confounder. In these sensitivity analyses, results were similar in females (all p < 0.05), while in males, the association between mastery and obesity (class III) was no longer significant ( p = 0.11).

Table 3 . Association between mastery (PMS) and weight status (BMI categories) in n = 30,339 participants, stratified by sex (NutriNet-Santé cohort study, 2014).

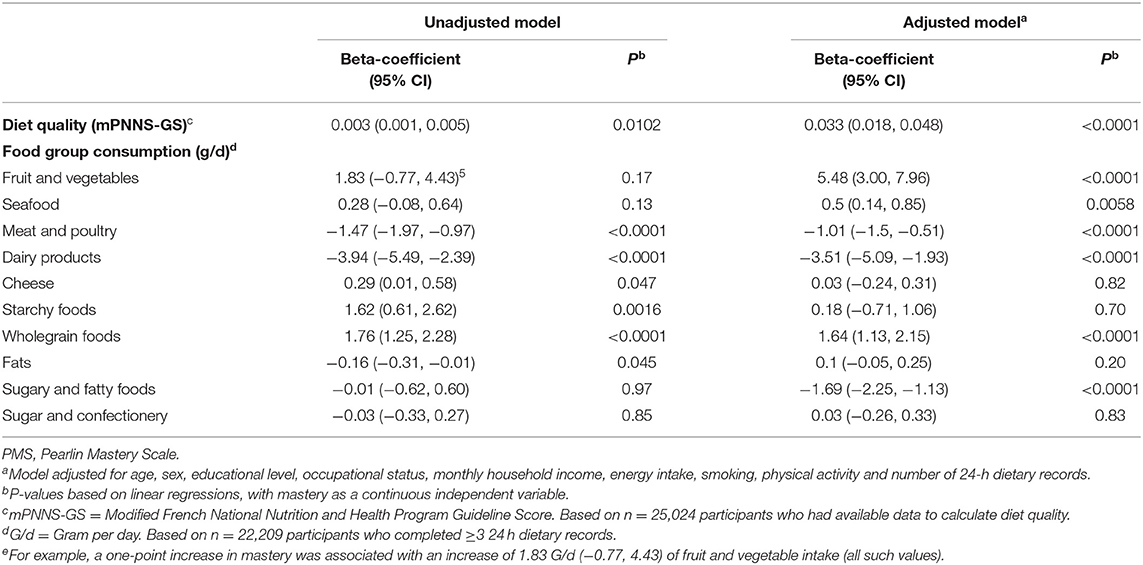

Relationship Between Mastery and Diet Quality as Well as Food Group Consumption

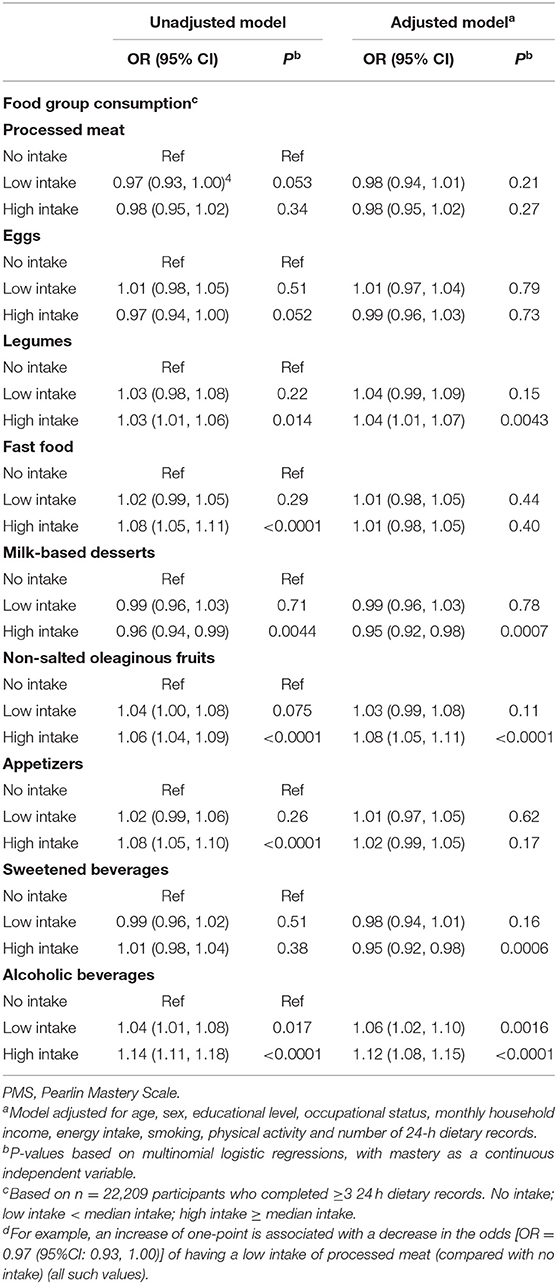

Table 4 presents the results of the linear regression models between mastery and diet quality as well as normally distributed intake of food groups. In the adjusted model, mastery was positively associated with diet quality and with consumption of fruit and vegetables, seafood, and wholegrain foods. Mastery was associated with a lower consumption of meat and poultry, dairy products, and sugary and fatty products. No association was found with cheese, starchy foods, fats, and sugar and confectionery. Table 5 presents the results of the logistic regression models between mastery and non-normally distributed intake of food groups. In the adjusted model, participants with a higher level of mastery were more likely to have a high intake of legumes, non-salted oleaginous fruits and a low or high intake of alcoholic beverages than participants with a lower level of mastery. In addition, they were less likely to have a high intake of milk-based desserts and sweetened beverages than participants with a lower level of mastery. No association was found with processed meat, eggs, fast food and appetizers. The sensitivity analyses showed similar results, except for an absence of association between mastery and the consumption of fruit and vegetables ( p = 0.11).

Table 4 . Associations between mastery (PMS), diet quality and consumption of food groups normally distributed (NutriNet-Santé cohort study, 2014).

Table 5 . Associations between mastery (PMS) and consumption of food groups non-normally distributed (NutriNet-Santé cohort study, 2014).

Relationship Between Mastery and Snacking

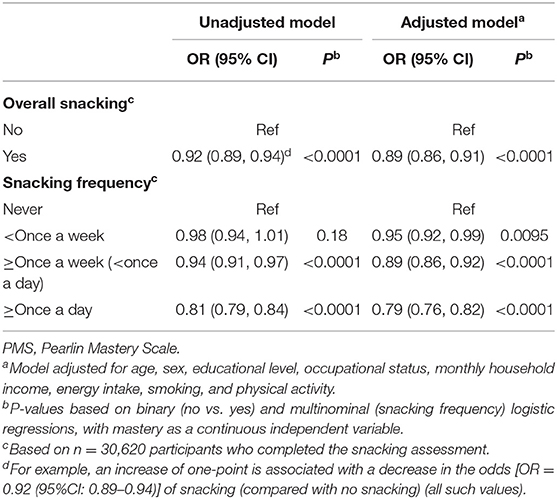

Table 6 presents the results of the logistic regression models between mastery and snacking. In the adjusted model, participants with a higher level of mastery were less likely to snack than participants with a lower level of mastery. The ORs decreased with higher snacking frequency. Overall, the sensitivity analyses showed equivalent results with the main observations (all p < 0.05).

Table 6 . Association between mastery (PMS) and snacking (NutriNet-Santé cohort study, 2014).

Relationship Between Mastery and ED Symptoms

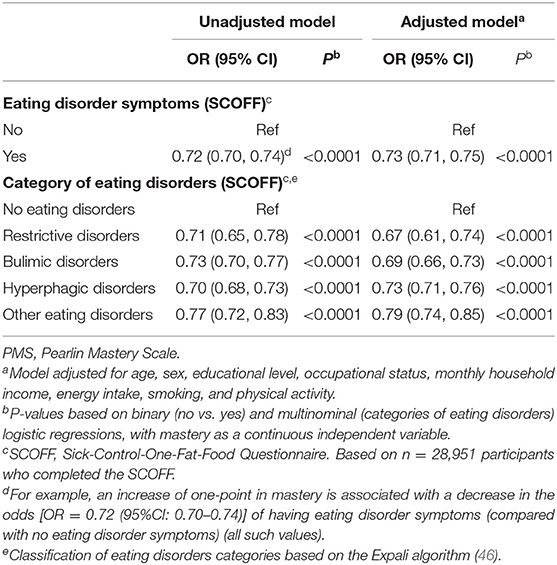

Table 7 presents the results of the logistic regression models between mastery and ED symptoms. In the adjusted model, participants with a higher level of mastery were less likely to have ED symptoms (restrictive/bulimic/hyperphagic and other EDs) than participants with a lower level of mastery. Overall, the sensitivity analyses showed equivalent results with the main observations (all p < 0.01).

Table 7 . Association between mastery (PMS) and eating disorder symptoms (NutriNet-Santé cohort study, 2014).

The aim of this study was to investigate the association between level of mastery and weight status, food intake, snacking and EDs in a large sample of French adults. We found that females with a higher level of mastery were less likely to be underweight, overweight or obese (all classes) than females with a lower level of mastery and that males with a higher level of mastery were less likely to be obese (class III) than males with a lower level of mastery. In addition, mastery was associated with better diet quality overall, a higher consumption of fruit and vegetables, seafood, wholegrain foods, legumes, non-salted oleaginous fruits, and alcoholic beverages and with a lower consumption of meat and poultry, dairy products, sugary and fatty products, milk-based desserts and sweetened beverages. Furthermore, mastery was associated with a lower snacking frequency and less ED symptoms.

Level of Mastery According to Sociodemographic and Lifestyle Characteristics

The mean overall mastery score in our study was comparable to previous studies ( 10 , 53 ). In line with the literature, mastery was higher in males ( 10 , 11 , 19 ), in participants who were younger ( 10 , 24 ), had a higher education ( 54 ), income ( 55 ), physical activity ( 10 , 21 ), no depressive symptomatology ( 13 , 15 , 19 ) and were self-employed/farmers or managerial staff/intellectual professions ( 53 ). Current smokers showed the highest level of mastery. This relationship has to be further examined since data in the literature are contradictory ( 10 , 21 , 24 ).

Our results showing that females with a higher level of mastery were less likely to be underweight, overweight or obese (all classes) were maintained when controlling for depressive symptomatology and are in line with some studies ( 10 , 15 , 27 ), but not others ( 18 – 20 ). Since mastery goes along with beliefs about the general controllability of the environment ( 56 ), individuals with a high level of mastery might perceive their life circumstances as a result of their own behavior and choices. This may lead to more health-promoting behaviors ( 56 ) and thus to a more favorable weight status. Mastery could also buffer the negative effect of stress on weight gain as suggested by another study ( 27 ). Our results showed only limited associations between mastery and weight status in males which is reflected in inconsistent results from previous studies ( 10 , 15 , 18 , 19 ). These sex-specific associations might be explained by lower prevalence rates of perceived weight discrimination in males and by the fact that males with obesity are generally more accepted than females with obesity ( 57 , 58 ). Mastery might be required when being judged by others and might therefore play a more important role in females than in males regarding weight gain. Given that our data are cross-sectional, the causal relationship between mastery and weight status remains unclear. Reciprocal links are conceivable, e.g., in the course of an intervention promoting obesity-provoking behavior, mastery decreased ( 59 ). Further studies on the mutual influence and dynamics between mastery and weight status are needed.

In line with a previous study in a representative sample ( 21 ), our results showed that mastery was associated with better diet quality overall in both males and females and more specifically, with a higher consumption of several healthy food groups (e.g., wholegrain foods) and a lower consumption of several unhealthy food groups (e.g., sugary and fatty foods). However, it has been proposed that the perceived utility from healthy eating might be sex-specific which might influence the relationship between mastery and healthy food choices ( 21 ). Males with a high level of mastery expected higher returns (a better health status) of their health-promoting behaviors while females with a high level of mastery showed more health-promoting behaviors as they may derive more pleasure out of these behaviors ( 21 ). Other studies showed no association with DASH (dietary approaches to stop hypertension) adherence ( 22 ) or specific food groups in specific populations with small sample sizes ( 23 , 24 ). Although mastery was mainly associated with a healthier food intake, we also found that mastery was associated with a higher intake of alcoholic beverages, in line with previous studies ( 21 , 60 ). Social support is positively correlated with level of mastery ( 60 ), which might lead to a wider social circle and an increased opportunity to share convivial meals, during which alcoholic beverages are often consumed ( 61 , 62 ). Further, the perception of having control over life circumstances might also lead to the perception of having better coping strategies to deal with the effects of alcohol ( 21 ). This might explain why mastery is associated with a healthier food intake overall, but also with a higher consumption of alcoholic beverages.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the relationship between mastery and snacking. Individuals with a higher level of mastery were less likely to snack, and the ORs decreased with snacking frequency. This is in line with the idea that a high level of mastery is related to more deliberate choices and less affective choices ( 21 ). As we live in an obesogenic environment where snacks, especially high-calorie snacks, are available almost anytime, a global sense of controllability and autonomy might go along with the capacity of resisting these temptations. In contrast, when individuals experience feelings of helplessness and desperation, one maladaptive coping strategy might be to snack in order to seek comfort (emotional eating) ( 63 ). However, more research about potential mechanisms between mastery and snacking is needed.

In line with some studies ( 19 , 27 ), but not all ( 20 ), individuals with a higher level of mastery were less likely to have ED symptoms than individuals with a lower level of mastery. A low level of mastery is reflected by feelings of helplessness and feelings of being exposed to stressors without having adequate coping strategies. Thus, a low level of mastery might contribute to the development of an ED and the key features of EDs, e.g., constantly monitoring eating behavior, body weight and shape might represent an attempt to gain back a sense of control ( 64 ). However, as our results were only based on cross-sectional data, we cannot draw any conclusions about the causal relationship between mastery and EDs. It is also conceivable that experiences as loss of control eating or purging might lead to a lower level of mastery.

Techniques to Enhance Mastery

As results have shown that mastery is associated with favorable outcomes overall, it may be a potential facilitator in promoting healthy dietary behavior. Mastery can be enhanced with cognitive techniques by increasing the understanding of the relevance of cognitive control in daily life ( 65 ). Tools to enhance mastery can be examining personal choices, planning desirable daily activities, coping with problems that cannot be changed and promoting a more satisfying lifestyle ( 65 ).

Strengths and Limitations

One strength of the study is the large population-based sample that allowed taking into account various confounders. However, the fact that the participants were recruited on a voluntarily basis could imply a strong interest in health and nutrition topics. Thus, a selection bias cannot be ruled out ( 66 , 67 ). To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the association between mastery and food group consumption based on ≥3 24-h dietary records that serve as a good indicator of usual diet. Further, we conducted sensitivity analyses by controlling for depressive symptomatology and results were comparable to the main observations. The SCOFF was used to assess ED symptoms. Due to its good sensitivity and specificity it is recommended as a screening tool ( 41 – 43 ). However, we observed a low reliability of the scale in line with other studies ( 68 , 69 ), which can be explained by its heterogenous items. We used the Expali algorithm, which enables distinguishing among the main categories of EDs. Nevertheless, the SCOFF cannot substitute for a clinical diagnosis, and we cannot exclude the possibility of having a certain number of false positive or false negative responses. The web-based self-report of height and weight could have led to random and systematic errors ( 70 ). However, standardized clinical measurements in a subsample ( N = 2,513) of the NutriNet-Santé study showed good convergence with self-reported data ( 71 ) and the large sample size can contribute to a minimization of the impact of measurement error ( 72 ). Our data supported the reliability of the PMS. However, although the indices of CFI and SRMR were adequate, RMSEA exceeded recommended cut-off values ( 52 , 73 ). Still, the inconsistency of CFI and RMSEA does not necessarily have to result in a rejection of the model ( 74 ). Another limitation is the cross-sectional design. As previous studies have shown that mastery varies over time and is influenced by critical life experiences ( 75 ), causal studies are needed. Finally, our paper focused on mastery as one aspect of control. However, there is a lack of consensus on theories and definitions with regard to control-related constructs, e.g., self-efficacy or locus of control ( 76 ). This might lead to difficulties in comparing and interpreting results.

Conclusions

Our results showed that females with a higher level of mastery were less likely to be underweight, overweight, or obese (all classes) while associations were more limited in males as males with a higher level of mastery were only less likely to be obese (class III). Mastery was associated with a better diet quality overall and with a higher consumption of several healthy food groups, e.g., wholegrain foods as well as with a lower consumption of several unhealthy food groups, e.g., sugary and fatty foods. However, mastery was also associated with a higher intake of alcoholic beverages. In addition, individuals with a higher level of mastery were less likely to snack and to have ED symptoms. As our results revealed that mastery is associated with favorable outcomes, mastery may be a potential facilitator in promoting healthy dietary behavior. However, research based on longitudinal designs and randomized-controlled trials are needed to further investigate these associations.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data of this study are protected under the protection of health data regulation set by the Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés (CNIL). If you are a researcher of a public institution, you can submit a collaboration request including your institution and a brief description of your project to collaboration@etude-nutrinet-sante.fr . All requests will be reviewed by the steering committee of the NutriNet-Santé study. A financial contribution may be requested. If the collaboration is accepted, a data access agreement will be necessary and appropriate authorizations from the competent administrative authorities may be needed. In accordance with existing regulations, no personal data will be accessible. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to collaboration@etude-nutrinet-sante .

Ethics Statement

The NutriNet-Santé cohort study was conducted in line with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Research Board of the French Institute for Health and Medical Research (IRB INSERM no. 0000388FWA00005831) and the Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés (CNIL nos. 908450 and 909216). Electronic informed consent was given by all participants. The study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03335644). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

UG, SP, and FE designed research (project conception, development of overall research plan, and study oversight). SP, VA, SH, and MT conducted research (hands-on conduct of the experiments and data collection). MR and UG analyzed data or performed statistical analysis. UG wrote paper. SP had primary responsibility for final content. UG, MR, NB, AN, FE, ST, VA, MT, and SP read and revised the manuscript and approved the final version. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The NutriNet-Santé cohort study was supported by the following public institutions: Ministère de la Santé, Santé Publique France, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), Institut National de Recherche pour l'Agriculture, l'Alimentation et l'Environnement (INRAE), Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers (CNAM), and Sorbonne Paris Nord Université. This research was part of the FOODPOL project, which was supported by the INRAE in the context of the 2013–2017 Metaprogramme Diet impacts and determinants: Interactions and Transitions. In addition, the project was part of the PSYCHALIM project supported by the INRAE and the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CRNS), in the context of the 2019–2021 Défi Mutations Alimentaires. UAG was supported by NutriAct – Competence Cluster Nutrition Research Berlin- Potsdam funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (FKZ: 01EA1408A-G).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cédric Agaesse (manager), Alexandre De-Sa and Rebecca Lutchia (dietitians), Thi Hong Van Duong, Younes Esseddik (IT manager), Régis Gatibelza, Jagatjit Mohinder and Aladi Timera (computer scientists), Julien Allegre, Nathalie Arnault, Laurent Bourhis, Nicolas Dechamp and Fabien Szabo de Edelenyi, Ph.D. (manager) (data-manager/statisticians), Sandrine Kamdem (health event validator), Maria Gomes (Nutrinaute support) for their technical contribution to the NutriNet-Santé study and Nathalie Druesne-Pecollo, Ph.D. (operational manager). We also thank all the volunteers in the NutriNet-Santé cohort. We also thank Pr. Pierre Déchelotte and Marie-Pierre Tavolacci for their involvement in the assessment of eating disorder symptoms in the NutriNet-Santé study.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2022.871669/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression; DV, dependent variable; IV, independent variable; mPNNS-GS, Modified French National Nutrition and Health Program Guideline Score; PMS, Pearlin Mastery Scale; SCOFF, Sick-Control-One-Fat-Food Questionnaire; ED, Eating disorders; CFI, Comparative fit index; RMSEA, Root mean square error of approximation; and SRMR, Standardized root mean square residual.

1. Gerlach G, Herpertz S, Loeber S. Personality traits and obesity: a systematic review. Obes Rev. (2015) 16:32–63. doi: 10.1111/obr.12235

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Farstad SM, McGeown LM, von Ranson KM. Eating disorders and personality, 2004-2016: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. (2016) 46:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.04.005

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Lunn TE, Nowson CA, Worsley A, Torres SJ. Does personality affect dietary intake? Nutrition. (2014) 30:403–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2013.08.012

4. Stok FM, Hoffmann S, Volkert D, Boeing H, Ensenauer R, Stelmach-Mardas M, et al. The DONE framework: creation, evaluation, and updating of an interdisciplinary, dynamic framework 2.0 of determinants of nutrition and eating. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0171077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171077

5. Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology: an introduction. Am Psychol. (2000) 55:5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

6. Bolier L, Haverman M, Westerhof GJ, Riper H, Smit F, Bohlmeijer E. Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health. (2013) 13:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-119

7. Seligman MEP. Positive health. Appl Psychol. (2008) 57:3–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00351.x

8. Pearlin LI, Nguyen KB, Schieman S, Milkie MA. The life-course origins of mastery among older people. J Health Soc Behav. (2007) 48:164–79. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800205

9. Pearlin LI, Schooler C. The structure of coping. J Health Soc Behav. (1978) 19:2–21. doi: 10.2307/2136319

10. Surtees PG, Wainwright NW, Luben R, Wareham NJ, Bingham SA, Khaw K-T. Mastery is associated with cardiovascular disease mortality in men and women at apperently low risk. Health Psychol. (2010) 29:412–20. doi: 10.1037/a0019432

11. Lee WJ, Liang CK, Peng LN, Chiou ST, Chen LK. Protective factors against cognitive decline among community-dwelling middle-aged and older people in Taiwan: a 6-year national population-based study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. (2017) 17:20–7. doi: 10.1111/ggi.13041

12. Roepke SK, Grant I. Toward a more complete understanding of the effects of personal mastery on cardiometabolic health. Health Psychol. (2011) 30:615–32. doi: 10.1037/a0023480

13. Lundgren O, Garvin P, Jonasson L, Andersson G, Kristenson M. Psychological resources are associated with reduced incidence of coronary heart disease. An 8-Year follow-up of a community-based swedish sample. Int J Behav Med. (2015) 22:77–84. doi: 10.1007/s12529-014-9387-5

14. Penninx BW, Van Tilburg T, Kriegsman DMW, Deeg DJH, Boeke AJP, Van Eijk JTM. Effects of social support and personal coping resources on mortality in older age: the longitudinal aging study Amsterdam. Am J Epidemiol. (1997) 146:510–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009305

15. Sammul S, Viigimaa M. Rapid socio-economic changes, psychosocial factors and prevalence of hypertension among men and women aged 55 years at baseline in Estonia: a 13-year follow-up study. Blood Press. (2018) 27:351–7. doi: 10.1080/08037051.2018.1476054

16. Togari T, Yonekura Y. A Japanese version of the Pearlin and Schooler's Sense of Mastery Scale. Springerplus. (2015) 4:399. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1186-1

17. Crowe L, Butterworth P. The role of financial hardship, mastery and social support in the association between employment status and depression: results from an Australian longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open. (2016) 6:e009834. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009834

18. Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Puhl R, Dyrbye LN, Dovidio JF, Yeazel M, et al. The adverse effect of weight stigma on the well-being of medical students with overweight or obesity: findings from a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. (2015) 30:1251–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3266-x

19. Wellman JD, Araiza AM, Solano C, Berru E. Sex differences in the relationships among weight stigma, depression, and binge eating. Appetite. (2019) 133:166–73. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2018.10.029

20. Froreich FV, Vartanian LR, Grisham JR, Touyz SW. Dimensions of control and their relation to disordered eating behaviours and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. J Eat Disord. (2016) 4:14. doi: 10.1186/s40337-016-0104-4

21. Cobb-Clark DA, Kassenboehmer SC, Schurer S. Healthy habits: the connection between diet, exercise, and locus of control. J Econ Behav Organ. (2014) 98:1–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2013.10.011

22. Mackenbach JD, Lakerveld J, Generaal E, Gibson-Smith D, Penninx BWJH, Beulens JWJ. Local fast-food environment, diet and blood pressure: the moderating role of mastery. Eur J Nutr. (2019) 58:3129–34. doi: 10.1007/s00394-018-1857-0

23. Jonnalagadda SS, Diwan S. Health behaviors, chronic disease prevalence and self-rated health of older asian indian immigrants in the U.S. J Immigr Health. (2005) 7:75–83. doi: 10.1007/s10903-005-2640-x

24. Daniel M, Brown A, Dhurrkay JG, Cargo MD, O'Dea K. Mastery, perceived stress and health-related behaviour in northeast Arnhem Land: a cross-sectional study. Int J Equity Health. (2006) 5:10. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-5-10

25. Park CL, Iacocca MO. A stress and coping perspective on health behaviors: theoretical and methodological considerations. Anxiety Stress Coping. (2014) 27:123–37. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2013.860969

26. Verhoeven AAC, Adriaanse MA, de Vet E, Fennis BM, de Ridder DTD. It's my party and I eat if I want to. Reasons for unhealthy snacking. Appetite. (2015) 84:20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.09.013

27. Roberts C, Troop N, Connan F, Treasure J, Campbell IC. The effects of stress on body weight: Biological and psychological predictors of change in BMI. Obesity. (2007) 15:3045–55. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.363

28. Hercberg S, Castetbon K, Czernichow S, Malon A, Méjean C, Kesse-Guyot E, et al. The Nutrinet-Santé study: a web-based prospective study on the relationship between nutrition and health and determinants of dietary patterns and nutritional status. BMC Public Health. (2010) 10:242. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-242

29. Eklund M, Erlandsson LK, Hagell P. Psychometric properties of a swedish version of the Pearlin Mastery Scale in people with mental illness and healthy people. Nord J Psychiatry. (2012) 66:380–8. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2012.656701

30. World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. WHO Technical Report Series no. 894 . Geneva: World Health Organization (2000).

Google Scholar

31. Touvier M, Kesse-Guyot E, Méjean C, Pollet C, Malon A, Castetbon K, et al. Comparison between an interactive web-based self-administered 24 h dietary record and an interview by a dietitian for large-scale epidemiological studies. Br J Nutr. (2011) 105:1055–64. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510004617

32. Le Moullec N, Deheeger M, Preziosi P, Monteiro P, Valeix P, Roland-Cachera MF. Validation of the photo manual used for the collection of dietary data in the SU. VI. MAX. study. Cah Nutr Diet. (1996) 31:158–64.

33. Nutrinet-Santé Study. Table de composition des aliments de l'étude Nutrinet-Santé [Nutrinet-Santé Study food-composition database] . Paris (2013).

34. Black A. Critical evaluation of energy intake using the Goldberg cut-off for energy intake: Basal metabolic rate. A practical guide to its calculation, use and limitations. Int J Obes. (2000) 24:1119–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801376

35. Schofield WN. Predicting basal metabolic rate, new standards and review of previous work. Hum Nutr Clin Nutr. (1985) 39:5–41.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

36. Goldberg GR, Black AE, Jebb SA, Cole TJ, Murgatroyd PR, Coward WA. Critical evaluation of energy intake data using fundamental principles of energy physiology: 1. derivation of cut-off limits to identify under-recording. Eur J Clin Nutr. (1991) 45:569–81.

37. Lassale C, Castetbon K, Laporte F, Deschamps V, Vernay M, Camilleri GM, et al. Correlations between fruit, vegetables, fish, vitamins, and fatty acids estimated by web-based nonconsecutive dietary records and respective biomarkers of nutritional status. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2016) 116:427–438.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.09.017

38. Lassale C, Castetbon K, Laporte F, Camilleri GM, Deschamps V, Vernay M, et al. Validation of a web-based, self-administered, non-consecutive-day dietary record tool against urinary biomarkers. Br J Nutr. (2015) 113:953–62. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515000057

39. Estaquio C, Kesse-Guyot E, Deschamps V, Bertrais S, Dauchet L, Galan P, et al. Adherence to the French Programme National Nutrition Santé Guideline Score is associated with better nutrient intake and nutritional status. J Am Diet Assoc. (2009) 109:1031–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.03.012

40. Assmann KE, Andreeva VA, Camilleri GM, Verger EO, Jeandel C, Hercberg S, et al. Dietary scores at midlife and healthy ageing in a French prospective cohort. Br J Nutr. (2016) 116:666–76. doi: 10.1017/S0007114516002233

41. Garcia FD, Grigioni S, Chelali S, Meyrignac G, Thibaut F, Dechelotte P. Validation of the French version of SCOFF questionnaire for screening of eating disorders among adults. World J Biol Psychiatry. (2010) 11:888–93. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2010.483251

42. Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacey JH. The SCOFF questionnaire: assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ. (1999) 319:1467–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1467

43. Botella J, Sepúlveda AR, Huang H, Gambara H. A meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of the SCOFF. Span J Psychol. (2013) 16:E92. doi: 10.1017/sjp.2013.92

44. Perry L, Morgan J, Reid F, Brunton J, O'Brien A, Luck A, et al. Screening for symptoms of eating disorders: reliability of the SCOFF screening tool with written compared to oral delivery. Int J Eat Disord. (2002) 32:466–72. doi: 10.1002/eat.10093

45. Hayes AF, Coutts JJ. Use Omega rather than Cronbach's Alpha for estimating reliability. But…. Commun Methods Meas. (2020) 14:1–24. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2020.1718629

46. Tavolacci MP, Gillibert A, Zhu Soubise A, Grigioni S, Déchelotte P. Screening four broad categories of eating disorders: Suitability of a clinical algorithm adapted from the SCOFF questionnaire. BMC Psychiatry. (2019) 19:366. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2338-6

47. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders . 5th ed. Washington, DC (2000).

48. Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques [National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies]. Consumption units. (2016). Available online at: http://www.insee.fr/en/methodes/default.asp?page=definitions/unite-consommation.htm (accessed: October 13, 2021)

49. Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-Country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2003) 35:1381–95. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB

50. Fuhrer R, Rouillon F. La version française de l'échelle CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale). Description et traduction de l'échelle d'autoévaluation. Psychatr Psychobiol. (1989) 4:163–6. doi: 10.1017/S0767399X00001590

51. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. (1977) 1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306

52. Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. (1999) 6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

53. Kovess-Masfety V, Leray E, Denis L, Husky M, Pitrou I, Bodeau-Livinec F. Mental health of college students and their non-college-attending peers: results from a large French cross-sectional survey. BMC Psychol. (2016) 4:20. doi: 10.1186/s40359-016-0124-5

54. Kubzansky LD, Berkman LF, Glass TA, Seeman TE. Is educational attainment associated with shared determinants of health in the elderly? Findings from the MacArthur Studies of successful aging. Psychosom Med. (1998) 60:578–85. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199809000-00012

55. Lachman ME, Weaver SL. The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1998) 74:763–73. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.763

56. Paquet C, Dubé L, Gauvin L, Kestens Y, Daniel M. Sense of mastery and metabolic risk: moderating role of the local fast-food environment. Psychosom Med. (2010) 72:324–31. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181cdf439

57. Spahlholz J, Baer N, König HH, Riedel-Heller SG, Luck-Sikorski C. Obesity and discrimination - a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Obes Rev. (2016) 17:43–55. doi: 10.1111/obr.12343

58. Puhl RM, Andreyeva T, Brownell KD. Perceptions of weight discrimination: prevalence and comparison to race and gender discrimination in America. Int J Obes. (2008) 32:992–1000. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.22

59. Ernersson Å, Frisman GH, Sepa Frostell A, Nyström FH, Lindström T. An obesity provoking behaviour negatively influences young normal weight subjects' health related quality of life and causes depressive symptoms. Eat Behav. (2010) 11:247–52. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.05.005

60. Mäkelä P, Raitasalo K, Wahlbeck K. Mental health and alcohol use: a cross-sectional study of the Finnish general population. Eur J Public Health. (2015) 25:225–31. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku133

61. Kritsotakis G, Konstantinidis T, Androulaki Z, Rizou E, Asprogeraka EM, Pitsouni V. The relationship between smoking and convivial, intimate and negative coping alcohol consumption in young adults. J Clin Nurs. (2018) 27:2710–8. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13889

62. Grønkjær M, Vinther-Larsen M, Curtis T, Grønbæk M, Nørgaard M. Alcohol use in Denmark: a descriptive study on drinking contexts. Addict Res Theory. (2010) 18:359–70. doi: 10.3109/16066350903145056

63. Camilleri GM, Méjean C, Kesse-Guyot E, Andreeva VA, Bellisle F, Hercberg S, et al. The associations between emotional eating and consumption of energy-dense snack foods are modified by sex and depressive symptomatology. J Nutr. (2014) 144:1264–73. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.193177

64. Sassaroli S, Gallucci M, Ruggiero GM. Low perception of control as a cognitive factor of eating disorders. Its independent effects on measures of eating disorders and its interactive effects with perfectionism and self-esteem. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. (2008) 39:467–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.11.005

65. Reich JW, Zautra AJ. A perceived control intervention for at-risk older adults. Psychol Aging. (1989) 4:415–24. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.4.4.415

66. Andreeva VA, Salanave B, Castetbon K, Deschamps V, Vernay M, Kesse-Guyot E, et al. Comparison of the sociodemographic characteristics of the large NutriNet-Santé e-cohort with French Census data: the issue of volunteer bias revisited. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2015) 69:893–8. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-205263

67. Andreeva VA, Deschamps V, Salanave B, Castetbon K, Verdot C, Kesse-Guyot E, et al. Comparison of dietary intakes between a large online cohort study (Etude NutriNet-Santé) and a nationally representative cross-sectional study (Etude Nationale Nutrition Santé) in France: addressing the issue of generalizability in E-Epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. (2016) 184:660–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww016

68. Ruzanska UA, Warschburger P. Psychometric evaluation of the German version of the Intuitive Eating Scale-2 in a community sample. Appetite. (2017) 117:126–34. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.06.018

69. Richter F, Strauss B, Braehler E, Adametz L, Berger U. Screening disordered eating in a representative sample of the german population: Usefulness and psychometric properties of the german SCOFF questionnaire. Eat Behav. (2017) 25:81–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.06.022

70. Rosella LC, Corey P, Stukel TA, Mustard C, Hux J, Manuel DG. The influence of measurement error on calibration, discrimination, and overall estimation of a risk prediction model. Popul Health Metr. (2012) 10:20. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-10-20

71. Lassale C, Péneau S, Touvier M, Julia C, Galan P, Hercberg S, et al. Validity of web-based self-reported weight and height: results of the Nutrinet-Santé study. J Med Internet Res. (2013) 15:e152. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2575

72. Hutcheon JA, Chiolero A, Hanley JA. Random measurement error and regression dilution bias. BMJ. (2010) 340:c2289. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2289

73. Bentler PM. Quantitative methods in psychology: comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. (1990) 107:238–46. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

74. Lai K, Green SB. The problem with having two watches: assessment of fit when RMSEA and CFI disagree. Multivariate Behav Res. (2016) 51:220–39. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2015.1134306

75. Jang Y, Chiriboga DA, Lee J, Cho S. Determinants of a sense of mastery in Korean American elders: a longitudinal assessment. Aging Ment Health. (2009) 13:99–105. doi: 10.1080/13607860802154531

76. Jacelon CS. Theoretical perspectives of perceived control in older adults: a selective review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. (2007) 59:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04320.x

Keywords: mastery, locus of control, weight status, diet quality, food group consumption, snacking, eating disorder symptoms, large population

Citation: Gisch UA, Robert M, Berlin N, Nebout A, Etilé F, Teyssier S, Andreeva VA, Hercberg S, Touvier M and Péneau S (2022) Mastery Is Associated With Weight Status, Food Intake, Snacking, and Eating Disorder Symptoms in the NutriNet-Santé Cohort Study. Front. Nutr. 9:871669. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.871669

Received: 08 February 2022; Accepted: 15 April 2022; Published: 25 May 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Gisch, Robert, Berlin, Nebout, Etilé, Teyssier, Andreeva, Hercberg, Touvier and Péneau. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sandrine Péneau, s.peneau@eren.smbh.univ-paris13.fr

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PMC10694452

Nutritional counseling in athletes: a systematic review

Simona fiorini.

1 Human Nutrition and Eating Disorder Research Center, Department of Public Health, Experimental and Forensic Medicine, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy

2 Laboratory of Food Education and Sport Nutrition, Department of Public Health, Experimental and Forensic Medicine, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy

Lenycia De Cassya Lopes Neri

Monica guglielmetti, elisa pedrolini, anna tagliabue, paula a. quatromoni.

3 Department of Health Sciences, Sargent College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Boston University, Boston, MA, United States

Cinzia Ferraris

Associated data.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Many studies report poor adherence to sports nutrition guidelines, but there is a lack of research on the effectiveness of nutrition education and behavior change interventions in athletes. Some studies among athletes demonstrate that nutrition education (NE), often wrongly confused with nutritional counseling (NC), alone is insufficient to result in behavior change. For this reason, a clear distinction between NC and NE is of paramount importance, both in terms of definition and application. NE is considered a formal process to improve a client’s knowledge about food and physical activity. NC is a supportive process delivered by a qualified professional who guides the client(s) to set priorities, establish goals, and create individualized action plans to facilitate behavior change. NC and NE can be delivered both to individuals and groups. To our knowledge, the efficacy of NC provided to athletes has not been comprehensively reviewed. The aim of this study was to investigate the current evidence on the use and efficacy of nutritional counseling within athletes. A systematic literature review was performed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses method. The search was carried out in: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Science Direct, Cochrane Library between November 2022 and February 2023. Inclusion criteria: recreational and elite athletes; all ages; all genders; NC strategies. The risk of bias was assessed using the RoB 2.0 Cochrane tool. The quality of evidence checking was tested with the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool system. From 2,438 records identified, 10 studies were included in this review, with athletes representing different levels of competition and type of sports. The most commonly applied behavior change theory was Cognitive Behavioral Theory. NC was delivered mainly by nutrition experts. The duration of the intervention ranged from 3 weeks to 5 years. Regarding the quality of the studies, the majority of articles reached more than 3 stars and lack of adequate randomization was the domain contributing to high risk of bias. NC interventions induced positive changes in nutrition knowledge and dietary intake consequently supporting individual performance. There is evidence of a positive behavioral impact when applying NC to athletes, with positive effects of NC also in athletes with eating disorders. Additional studies of sufficient rigor (i.e., randomized controlled trials) are needed to demonstrate the benefits of NC in athletes.

Systematic review registration

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ , identifier CRD42022374502.

1. Introduction

Ensuring appropriate energy and nutrient intakes in athletes is critical in reaching and maintaining an optimal nutritional status, that supports peak performance and facilitates proper recovery after training and competition ( 1 , 2 ). The nutritional requirements of athletes are influenced by numerous factors including gender, life stage, type of sport, training, phase of competition, environmental temperature, stress, high altitude exposure, physical injuries, phase of the menstrual cycle. For this reason, athletes’ dietary habits and diet composition should be customized according to their individual performance goals, preferences, and training phase ( 1 ). This work typically requires input from nutrition professionals known as registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs) or accredited nutritionists, as terminology varies across the world.

Several authors report that many athletes do not meet their nutrition requirements ( 3 ) and do not have sufficient intakes of energy ( 4 , 5 ), carbohydrates ( 6–8 ) and several micronutrients ( 5 , 9 ). In contrast, some athletes seem to favor fat intake ( 8 , 10 , 11 ), which may be above the recommended levels ( 2 ), both considering the general sport requirements and the specific sport needs. The levels of inadequate intake are not surely known and can be influenced by the possible under-reporting ( 12–14 ) and are often based on the athletes’ limited nutrition knowledge ( 15–17 ). Moreover, athletes can adopt inappropriate and dysfunctional eating behaviors such as fasting, skipping meals, dieting, binge eating, vomiting, and use of laxatives and/or diet pills ( 18 ). Low sports nutrition knowledge and/or disordered eating behavior in the context of training and competing in sport can lead to the state of low energy availability (LEA) which is defined as the mismatch between energy intake and exercise energy expenditure ( 19 ). LEA in athletes may occur unintentionally (low awareness of the athletes’ nutritional needs), intentionally (attempts to optimize body composition for competition or to avoid weight gain during injury or illness), or compulsively (due to eating disorders [EDs] or disordered eating [DE] behavior) ( 20 ). One of the important health consequences of LEA is relative energy deficiency in sport (REDs), a syndrome characterized by a range of compromised physiological functions that negatively affect all body systems (i.e., metabolic rate, menstrual function, bone health, immunity, protein synthesis, cardiovascular health, gastrointestinal function, and more) ( 21 , 22 ). LEA and REDs undermine athletic performance and put the athlete’s physical and mental health at risk ( 23 ), making these conditions prime targets for prevention and intervention activities ( 24 ).

For all these reasons, the development and application of valid intervention strategies is necessary to support athletes and protect their health. Bentley and colleagues ( 25 ) conducted a systematic review of the main sport nutrition interventions (i.e., nutrition education, nutritional counseling, individual and group workshops, consultations) applied to athletes, reporting that the up-to-date evidence-based literature is limited in its ability to identify the most effective strategy for use with this population. In spite of this, several studies reported that nutritional counseling (NC) could represent an important strategy to modify dietary habits and behaviors of athletes ( 26–35 ) making this a worthwhile area of investigation.

NC is a supportive process, characterized by a collaborative relationship between the counselor and the client(s) to establish food, nutrition and physical activity priorities, goals, and action plans ( 36 ). It is included in the Nutrition Care Process (NCP) model as a specific nutrition intervention generally delivered by RDNs ( 36 ). NC may apply a variety of models belonging to behavior change theories. The more widely used, validated theories are cognitive behavioral theory (CBT), social cognitive theory (SCT), transtheoretical model (TM), health belief model (HBF), systemic therapy (ST), and Mindfulness. These tools and strategies may be applied by themselves or in combination with other theories (i.e., CBT and TM together) based on the patients’ goals, objectives, and personal skills ( 36 , 37 ). NC can be delivered both to individuals and groups.

It is important to identify NC as an intervention that is distinct from nutrition education (NE). NE is a formal process to instruct or help a patient in a skill or to impart knowledge to help clients voluntarily manage or modify food, nutrition, and physical activity choices and behavior to maintain or improve health ( 36 ). Designed to improve nutrition knowledge, its aim is to support sound food choices at the level of the community or within a specific target population ( 38 , 39 ). In contrast, NC is a dynamic, two-way interaction that actively involves the client, using their existing nutrition knowledge as a starting point to define and support key behavioral changes. NC typically occurs in the context of an ongoing professional relationship where the nutrition counselor works privately with the client through a series of individualized sessions. The role of the sport nutrition counselor is to help athletes identify, adopt, and sustain a customized fueling strategy that maximizes training, performance, recovery, and holistic well-being while applying resources that facilitate nutritionally adequate, balanced eating patterns and address potential obstacles and barriers that predispose athletes to LEA and REDs. There is a role for both NE and NC when working with athletes, but the most appropriate strategy is one that is individually selected by the nutrition professional informed by their appraisal of the nutritional assessment, nutrition-related diagnosis, client needs, abilities, and life circumstances ( 36 ).

The role of the sport nutrition counselor is to offer advice to people interested in solving various current problems that the client(s) may face, which comprehend, for example, the ones derived from the preparatory work for performance in sports (i.e., energy balance according to training duration, type and intensity), contests and competitions participation, to promote the personal image, proposing a new perspective that can lead to overcoming the perceived or objective difficulties (e.g., fear of gaining weight, inadequate nutritional intake, management of injuries, etc.) and to optimize sport performances ( 40 ).

To the best of our knowledge, no review articles evaluated the application of NC in athletes to date. This paper aims to systematically review the current evidence on the use of NC in athletes and to identify the specific outcomes investigated to characterize its impact.

2. Materials and methods

This systematic review was performed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) method ( 41 ). The search was carried out in the following electronic databases: PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect and Cochrane Library. The languages allowed were English and Italian according to the capability of comprehension of the authors. No limits were considered according to the date of publication. Randomized controlled trials, uncontrolled observational studies, case study, case reports and case series, opinion articles, conference abstracts, theses, and dissertations were included. The study protocol was previously submitted on the PROSPERO platform and has its registration number CRD42022374502.

2.1. Literature research strategy

An electronic search was conducted with subject index terms “nutritional counseling” OR “nutrition counseling” OR “nutritional and eating education” OR “nutritional program” combined with the term “athletes” OR “sports” OR “performance” OR “athletic performance” OR “recreational athletes” OR “elite athletes.” Google Scholar was used to search gray literature and some references found in review articles were included manually. The populations of interest were recreational and elite athletes. We did not specify comparison conditions in our search because this was not included in the aim of the study which was simply to evaluate the use of NC, not necessarily compared to other strategies. The search strategy is illustrated in Table 1 . Detailed criteria for study inclusion and exclusion are listed in Table 2 .

Search strategy for different databases.

PICOS criteria of inclusion and exclusion.

2.2. Study selection