- Open access

- Published: 18 September 2021

Implementation of active learning methods by nurse educators in undergraduate nursing students’ programs – a group interview

- Sanela Pivač 1 ,

- Brigita Skela-Savič 1 ,

- Duška Jović 2 ,

- Mediha Avdić 3 &

- Sedina Kalender-Smajlović 1

BMC Nursing volume 20 , Article number: 173 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

19k Accesses

6 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Modern and active learning methods form an important part in the education of Nursing students. They encourage the development of communication and critical thinking skills, and ensure the safe health care of patients. Our aim was to obtain naturalistic data from nurse educators regarding want the use and effects of implementing active learning methods (Peyton’s Four-Step Approach, Mind Mapping, Debriefing and Objective Structured Clinical Examination methods) in the study process of students of Nursing after a completed education module, Clinical skills of mentors , as part of the Strengthening Nursing in Bosnia and Herzegovina Project. We wish to learn about the perception of nurse educators regarding the use of active learning methods in the study process of Nursing in the future.

Qualitative research was conducted and a group interview technique was used for data collection. Beforehand, research participants were included in a two-day education module, Clinical skills of mentors , as part of the Strengthening Nursing in Bosnia and Herzegovina Project. Content analysis of the discussion transcriptions was conducted.

Fourteen nurse educators participated. Group interviews were conducted in September 2019. The obtained categories form four topics: (1) positive effect on the development of students’ communication skills (2) positive effect of learning methods on the development of students’ critical thinking skills (3) ensuring a safe learning environment (4) implementation of active learning methods.

Conclusions

The use of various active learning methods in simulation settings improves the Nursing students’ critical thinking and communication skills. Therefore, we believe that Peyton’s Four-Step Approach, Mind Mapping and Debriefing methods should be included as tools for effective student learning and as preparation for directly performing safe nursing interventions with a patient. Effective approaches to the assessment of Nursing students may ensure quality patient health care in accordance with the vision of the nursing profession.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Education of nurses in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) has been undergoing rapid development. In BiH, the emphasis of the health care system and the education of health professionals is mainly on curative care and medical services. This might limit the potential of the nursing staff to react to the population’s present and future health needs. To avoid the negative consequences of reduced competencies and practice, nurses developed a project that would strengthen nursing in BiH [ 1 ].

Several nursing-related challenges that currently have a negative effect on the nursing profession and which, therefore, hinder health outcomes in BiH, were identified in collaboration with major stakeholders in BiH, including faculties of nursing and other important organizations [ 2 ]. As stated by Francis and O’Brien [ 3 ], teaching clinical skills is an important part in educating students of Nursing in an increasingly more complex health care and social environment. As a method of teaching, skills-lab training is viewed as a key component of curricula in the majority of our faculties that offer health-related study programs as it enables a protected training environment where students are permitted to make mistakes and where they can practice their skills on mannequins before working on real patients [ 4 ].

In BiH, mentorship at faculties of Nursing is conducted by graduate nurses who are teaching assistants or senior teaching assistants rather than mentors, and are employed full-time or are outsourced. In BiH, there are no additional training options that would equip nurses to work as mentors, either full time or part time, so they only need to meet the general and specific criteria for an associate/teacher position [ 5 ]. That is why in 2017, the Strengthening Nursing in BiH Project developed a training program for BiH clinical skills mentors that comprised seven modules (34 h in total) and was focused on different aspects of adult education, and teaching tools and methods. In BiH, the faculties offering Nursing courses have been faced with challenges regarding the organization of additional training for clinical skills mentors. In order for mentors to be prepared for this role as best as they can, they use professional literature, the internet and engage in team meetings [ 6 ].

In order to improve nursing education, various teaching methods have been introduced to assist students in gaining knowledge, skills and attitudes that are relevant for nursing practice.

The implementation of active learning methods into the study process might result in students’ improved motivation for learning, encourage their critical thinking skills and independent learning [ 7 ]. Rather than continuing with employing traditional teacher-centered educational approaches, faculties should introduce an active student-centered learning environment since creating learning experiences that encourage reflection, knowledge building, problem-solving, inquiry, and critical thinking are highly significant [ 8 ]. Authors [ 9 , 10 ] state that active learning methods in nursing education are highly significant with an aim to eliminate passive listening and transition to assuming an active role in the educational process and obtain the ability to apply information from lectures in a meaningful way. The development of the pedagogical skills occurs according to the actual situation in the process of the nurse’s practical work [ 11 ].

The use of simulation-based learning contributes to the development of students’ sense of safety when they perform various tasks [ 12 ]. The skill laboratory functions as a transitional setting between a classroom and clinical venues [ 13 ].

Peyton’s Four-Step Approach is a learning method that comprises four steps and is highly effective in the learning process of nursing interventions. The first step is demonstration , in which the teacher demonstrates the intervention at their normal pace without giving any additional verbal explanations. The second step is deconstruction , in which the teacher performs the intervention by giving detailed descriptions of all the phases of the intervention. In the third step referred to as comprehension , the teacher performs the intervention according to the student’s instructions of each step of the intervention. In the final, fourth step called intervention , students perform the intervention by themselves without the help of the teacher [ 14 ]. In the research on the effectiveness of the method, the authors found that the Peyton’s Four-Step Approach method enables students’ active involvement in the process of learning about nursing intervention [ 15 ]. The process of self-explanation, which Peyton’s Four-Step Approach contains when a student is thinking aloud, enables an improved learning process and the development of critical thinking skills [ 16 ].

The Mind Mapping method is an excellent pedagogical tool used to help students achieve positive learning outcomes [ 17 ] that may be successfully implemented in the education process as it ensures a creative environment and is an effective tool for teachers, mentors, students and researchers [ 18 ]. The Mind Mapping method encourages students to obtain relevant information and develops critical thinking skills, which in turn, has positive effects on the provision of safe health care for patients [ 19 ]. There are several reasons why using the Mind Mapping method in learning and teaching is recommended. Firstly, there is no long text. Also, it enables learning through synthesizing, as well as clarification and better reorganization of ideas. Furthermore, it assists with revision, encourages visualization of the content that had been learnt before, enables cooperation via studying in groups, which has positive consequences for everybody involved, and finally, mind maps that are submitted to the group result in a better experience because more participants are involved, which produces more ideas and stimulates the use of critical thinking skills [ 20 , 21 , 22 ].

A guided discussion is also quite significant in teaching Nursing students as it enables very authentic simulations of reality since a mentor asks students to critically evaluate their knowledge and skills that they had demonstrated while performing the scenario. Despite much research conducted on educating with simulation, the guided discussion has not yet been sufficiently defined [ 23 ]. The use of scenarios with debriefing constitutes a strategy facilitating the teaching-learning process in the undergraduate nursing course [ 24 ].

The assessment of clinical skills is also highly significant in nursing education. Therefore, the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) may be considered to be a sound assessment tool whose objective is the assessment of nursing students’ clinical competences in a safe and controlled environment, which enables simple assessment of the knowledge and performance of clinical skills that are important in nursing practice. Also, the assessment tool may serve to better prepare students for their profession [ 25 , 12 ].

A higher education teacher is one of the key factors for a nursing student to be successful in their studies [ 26 ], so teachers should be familiar with effective teaching methods [ 27 ]. A teacher’s primary task is to ensure a creative environment and a learning path that engages a student [ 28 ]. A suitable learning method may encourage nursing students to learn, improve students’ communication, and motivate and inform them about effective learning [ 29 ].

Aim of the study

After conducting the educational module Clinical skills of mentors as part of the Strengthening Nursing in BiH Project, our aim was to obtain naturalistic data from nurse educators regarding the use and effects of introducing active learning methods (Peyton’s Four-Step Approach, Mind Mapping, Debriefing and Objective Structured Clinical Examination methods) in the study process of Nursing students. Nurse educators in BiH have not yet developed knowledge in the field of active and contemporary learning methods or competencies to transition to modern teaching methods from more traditional ones. That is why we conducted the research to learn about the perception of nurse educators about the use of active learning methods in the study process of Nursing in the future.

Our research question was

What is the perception of nurse educators on the use and effects of active learning methods in nursing undergraduate study programs?

The qualitative descriptive study of a formal group interview was used [ 30 ]. The group interview was conducted in pre-existing “natural” groups of nursing educators in a region of BiH. Invited participants attended a two-day education module: Clinical skills of mentors as part of the Strengthening Nursing in BiH Project that was hosted by two higher education senior lecturers of Nursing from Slovenia, where higher education and clinical mentorship in Nursing is developed in accordance with international [ 31 , 32 ] and national guidelines for Nursing education [ 33 ].

A group interview allows group members to influence each other with their comments and experience, and to form an opinion regarding the issue currently discussed after reflecting on it as a group [ 34 ], which results in obtaining more information than with face-to-face interviews [ 35 ].

Setting and participants

The environment in which the research was conducted impacted the format of the group [ 27 ] that was invited to participate for research purposes. 14 nurse educators that are employed at the faculty (n = 6) and/or in a clinical setting (n = 8) participated in a group interview. 12 women and two men participated, the average age of the participants was 35.7 years (SD = 0.7), the average length of service was 15.1 years (SD = 11.1). One participant had completed doctoral studies, nine held master’s degrees in Nursing and four held bachelor degree in Nursing.

Semi-structured guiding questions that were being updated throughout the discussion were used in the group interview. The semi-structured interview contained eight basic questions:

What is your opinion regarding the significance of the qualifications of nurse educators to work with Nursing students?

What skills should nurse educators have in order to teach students of Nursing effectively?

How useful do you think the Peyton’s Four-Step Approach method is for teaching Nursing students?

What is your opinion on the usefulness of the OSCE stations as a method of assessing Nursing students?

How do you assess the usefulness of the Mind Mapping method in the learning process?

What is your attitude towards using and implementing the Debriefing method in the process?

Which presented method do you think is most suitable for teaching the students of Nursing?

What is your attitude towards the impact of the presented learning methods and assessment on the development of critical thinking skills of Nursing students?

The reliability of the research was ensured by considering the homogeneity of the group, an appropriate number of participants in the interview, by giving instructions before the start of the interview emphasizing that everyone has the possibility to participate in the discussion and by encouraging them with questions when guiding the group interview [ 36 ]. The reliability check was ensured by digitally recording the conversations in the group interview. We then transcribed the recording and checked that the transcription matched the audio recording. To increase the validity of data analysis, two researchers analyzed the data and ensured that the codes were unified. An independent analysis of two researchers decreases the possibility of partiality and increases the interpretative basis of the research. With the thematic analysis, we demonstrated that data analysis has been conducted in a precise, consistent, and exhaustive manner through recording, systematizing, and disclosing the methods of analysis with enough detail [ 37 ]. Also, we used traditional tools: colored pens, paper, and sticky notes for ensuring rigor [ 38 ]. Authors checked the participants to ensure relevant evaluation [ 39 ].

Data collection

The group interview took place in September 2019 at the end of the education module and was guided by a moderator and a semi-structured questionnaire. There was also an administrator who recorded the discussions. The research participants attended a two-day education module, Clinical skills of mentors , as part of the Strengthening BiH Project. The purpose of the module was to inform and educate nurse educators about active learning methods and assessment of students of Nursing: Mind Mapping, Debriefing, Peyton’s Four-Step Approach methodology and the OSCE stations. We presented the purpose of the research and topics before conducting the group interview. The average time of the group interview was 90 min. Discussions were recorded upon obtaining a written permission by the participants. To ensure anonymity we added randomly selected letters to the interviewers.

Data analysis

For qualitative data, the method of thematic content analysis was employed. All recordings were transcribed verbatim and the texts were read several times. After coding units were identified, coding was conducted and categories and key topics were defined. Each participant in the group interview was ascribed a corresponding code. The nominal identity of a transcription was lost while the traceability of content was ensured. Authors state that a thematic analysis is a widely used qualitative analytical method that offers an accessible and theoretically adjustable approach to the analysis of qualitative data [ 40 ].

Based on an analysis of the text, 47 codes were designed alongside 14 umbrella categories. The obtained categories fall into four final topics: (1) a positive effect on the development of students’ critical thinking skills (2) a positive effect of learning methods on the development of students’ critical thinking skills (3) providing a safe learning environment (4) implementation of active learning methods (Table 1 ).

Table 2 presents topics that are substantiated by representative quotes, their effects on the education of students of nursing, the obstacles and consequences that nurse educators have observed, and suggestions regarding improvements based on the presented topics and statements.

1. A positive effect on the development of students’ communication skills

Participants in the group interview believed that various active methods have a positive effect on the development of Nursing students’ communication skills, and on achieving professional competencies in communication. They emphasize the importance of feedback exchanged between a student and a nurse educator that should be given at a time when a student is still thinking about their work and there is still time to improve the process itself. They think that feedback has an impact on the active role of a student and on achievement of the set goals. The research participants believe that showing nursing interventions several times during the learning process has positive effects on students’ memorizing skills and results in less errors when providing health care to patients.

2. The effect of learning methods on the development of critical thinking

In their statements, the participants of the group interview most often stated that using various innovative methods in a simulation setting encourages critical thinking skills of nursing students, impacts the development of students’ self-confidence and motivates them to work and study. Active participation and critical thinking lead students to successful problem solving. Participants believe that teaching by means of actively solving problems results in students’ reflecting and encourages them to show and say what they know. The participants emphasize that using certain methods of learning also depends on external resources.

3. Ensuring a safe learning environment

The participants of the group interview all thought that methods such as the Peyton’s Four-Step Approach method, the OSCE stations and Debriefing contribute to a safe clinical environment since students revise their knowledge and skills several times in simulated conditions and in this way strengthen their knowledge. They believe that preparing students to perform safe nursing intervention is connected to safe and quality patient health care in a clinical setting.

4. Implementation of active learning methods

The nurse educators included in the research found the presented methods highly suitable for use in the education process of Nursing students, but emphasized that a suitable venue should be provided, and that teachers or clinical mentors should be suitably prepared. They think that nurse educators neither have enough pedagogical and andragogical experiences and skills, nor knowledge on active learning methods.

With qualitative research, we obtained the views and opinions of nurse educators from some nursing faculties and clinical settings in BiH on the effects of active learning methods on students of nursing. Participants in the group interview believed that various active methods have a positive effect on the development of Nursing students’ communication skills, and on achieving professional competencies in communication. They emphasized the importance of feedback exchanged between a student and a nurse educator. Other research [ 41 , 42 , 43 ] also emphasizes the importance of communication skills, giving feedback and providing quality in nursing care. In our study the participants of the conducted research thought that active learning methods contribute to a more effective learning of nursing interventions, provide an active approach to learning about nursing interventions and enable a more confident performance of nursing interventions in a clinical setting with a patient, and provide a safe environment either for the patient or for the student.

Participants believe that the use of innovative methods in a simulation environment encourages students’ critical thinking, motivation, development of self-confidence and problem-based learning. Christianson Krista [ 44 ] puts great importance on the connection between emotional intelligence and critical thinking in nursing education. A study [ 45 ] demonstrated that critical thinking education improves problem-solving skills. A good relationship between a nurse educator and a student brings positive results in students’ education and motivates them for work in a clinical setting [ 46 ]. In addition, a teacher’s professional knowledge and their organizational and communication skills also have an effect on successful learning [ 47 ]. Baksi et al. [ 48 ] researched the effects that clinical preparatory education provided before the first clinical experience had on anxiety.

The opinions of the participants regarding the Debriefing method mostly refer to the importance of feedback. In researching debriefing practices in interprofessional simulation with students from the socio-material perspective, the findings have shown how debriefing intertwines with, and is shaped by social and material relationships. Two patterns of enacting debriefing were identified. First, debriefing as an algorithm was enacted as a protocol-based, closed inquiry approach and secondly, laissez-faire debriefing was enacted as a collegial conversation with an open inquiry approach that has a loose structure [ 49 ].

Nursing educators believe that active pedagogical methods of learning might help students to optimize the development of their critical thinking skills. Therefore, we believe that Peyton’s Four-Step Approach method, Mind Mapping and Debriefing should be included as a tool for successful learning of students and preparation for working directly with patients, which has already been pointed out by previous research conducted by Janicas and Narchi [ 24 ] and Francis and O’Brien [ 3 ].

The use of Mind Mapping helps students to understand their thinking process, obtain basic knowledge that they will upgrade with in-depth professional knowledge [ 18 ], and encourages them to learn independently, be independent and think critically [ 50 ]. While students were developing mind maps, they were also exploring the critical thinking concept by reflecting on how they make patient care decisions in a clinical setting [ 22 ]. The reflection resulted in the students being better able to describe their critical thinking process and demonstrate the concept graphically. Mind Mapping may be used to illustrate the pathways that encourage reflection on patient care [ 51 ].

The participants of our research believe that the methods that were presented and demonstrated with examples contribute to a safe clinical setting. Clark [ 25 ] also emphasizes that one of the more challenging tasks of faculties of health sciences is to educate students with competencies that will secure safe and effective nursing and patient care. In the research, nurse educators believe that active methods are very useful in the education process of Nursing students, but emphasize that an appropriate location should be provided and that nurse educators should be suitably trained. They also believe that nurse educators must have pedagogical and andragogical knowledge, so that they can implement active and quality teaching methods in the pedagogical process. The challenges in the training of nursing educators are in the transition from traditional education to simulated learning environment [ 52 ]. Addressing nurse educator challenges and empowering them with the means, opportunity and skills to utilize student-centered teaching and learning strategies may contribute to the development of undergraduate student nurses’ clinical reasoning skills. Raising awareness of the challenges that nurse educators experience in implementing student-centered facilitation of learning can assist in developing the strategies to ensure nurse educators become more student-centered in their teaching [ 53 ].

Based on the conducted research, we propose an implementation of active teaching methods in the educational process of nursing students. Recommendations relate to regular monitoring of learning objectives, evaluation, updating teaching methods and the transition from traditional forms of learning to innovative forms.

Limitations and Strengths

Nurse educators that had previously been included in the training on active teaching methods in Nursing were included in the research. An advantage of the research is that we have obtained the views and opinions of nurse educators regarding the usefulness and effectiveness of the presented methods in the undergraduate study program of Nursing immediately after the conducted theoretical and practical training. An important limitation is also the local context of nursing development in BiH. The convenient sampling does not always allow us to select the best representatives related to the research question. It is likely that the members included in the group are more motivated for improvements in nursing education than other nurses at faculties and clinical settings.

Further research should focus on two areas. Firstly, it should be researched how often active learning methods are used in the education process and secondly, the opinions of students on how active learning methods impact the understanding and learning of nursing intervention could be obtained. The limitation of the research is the time span of the education on active teaching methods and the selection of guiding questions, since we are aware that the selection of questions might partially impact the answers given by the participants. It may be supposed that a different selection of guiding questions might result in different opinions of nurse educators.

The results of the qualitative research were used to present the meaning and understanding of implementing active learning methods in undergraduate study programs of Nursing. Based on the conducted research we believe that nurse educators lack pedagogical and andragogical knowledge as well as knowledge of active learning methods. The use of active learning methods by nurse educators improves communication skills and develop students’ critical thinking skills. The final results of implementing active learning methods are in the acquired learning outcomes, nursing interventions that are performed optimally, development of competent professionals, boosting self-confidence, improvement of communication and critical thinking skills, as well as the self-initiative and readiness to work with patients in a clinical setting. Cutting edge and active learning methods are important for ensuring the quality of a study process and in the teaching of students of Nursing. We also wish to encourage study programs where the presented learning methods would be used in the study process, so that students will become active participants who can use their knowledge in providing safe patient care as a result of these active methods of teaching and learning.

We considered ethical principles of ensuring the voluntary nature of participating in the research, protecting the identity of individuals, confidentiality, privacy and respecting the truth. Research was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki-Tokyo Declaration [ 54 ], the Code of Ethics for Nurses and Nurse Assistants of Slovenia [ 55 ] and the ethical guidelines of the Social Research Ethics Guidance [ 56 , 57 ]. We did not apply for the approval by the National Medical Ethics Committee as the National Medical Ethics Committee only makes decisions concerning experimental research and non-experimental research conducted on patients and vulnerable groups in the population (patients, the elderly, children, disabled adults). Nurse educators do not form part of vulnerable groups and our questions were not considered to belong to the group of vulnerable questions. The study is exempt from ethical approval according national legislation (European Commission: Accession countries - legislation related to research ethics Slovenia).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Objective Structured Clinical Examination

Avdić M, Jović D, Dropić E, Van Malderen, Schwendimann R. Formal education of medical nurses in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Nursing Journal. 2014;1:25–27.

Google Scholar

Strengthening Nursing in Bosnia and Hercegovina Project, n. d. http://www.fondacijafami.org/Sestrinstvo_pdf_/Project%20Leaflet.pdf . Accessed 15 Jan 2020.

Francis G, O’Brien M. Teaching clinical skills in pre-registration nurse education: value and methods. Br J Nurs. 2019;28:452–6.

Article Google Scholar

Awad SA, Mohamed MHN. Effectiveness of Peyton’s Four-Step Approach on nursing students’ performance in skill-lab training. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2019;5:1–5.

Jović D, Avdić M, Katić-Vrdoljak I. Assessment of the needs for additional training for clinical skills mentors at the faculties with nursing studies in BiH. In: Pesjak K, Pivač S, editors. Inter-professional integration at different levels of healthcare: trends, needs and challenges. 11th International Scientific Conference, Bled, Slovenia, June 7th, 2018. Jesenice: Angela Boškin Faculty of Health Care; 2018. p. 83 – 8.

Jović D, Avdić M, Marković N, Katić-Vrdoljak I. Training scheme for clinical skills mentors in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In: Pesjak K, Mlakar S, editors. Responsibilities of health policy-makers and managers for the retention and development of nurses and other healthcare professionals – 2020: International year of the nurse and the midwife. 13th International Scientific Conference, Jesenice, Slovenia, September 24th, 2020. Jesenice: Angela Boškin Faculty of Health Care; 2020. p. 174-8.

Parikh ND. Effectiveness of teaching through mind mapping technique. Int J Indian Psychol. 2016;3:148–56.

Alexander BJ, Lindow LE, Schock MD. Measuring the impact of cooperative learning exercises on student perception of peerto - peer learning: a case study. J Physican Assist Educ. 2008;3:18–25.

Bristol T, Hagler D, McMillian-Bohler J, Wermers R, Hatch D, Oermann MH. Nurse educators’ use of lecture and active learning. Teach Learn Nurs. 2019;14:94–96.

Waldeck JN, Weimer M. Sound decision making about the lecture’s role in the college classroom. Commun Educ. 2017; doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2016.1275721 .

Benner P, Sutphen M, Leonard V, Day L. Educating nurses: a call for radical transformation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2010.

Smrekar M, Ledinski Fičko S, Hošnjak AM, Ilić B. Use of the objective structured clinical examination in undergraduate nursing education. Croat Nurs J. 2017;1:91–102.

Hashim R, Qamar K, Khan MA, Rehman S. Role of skill laboratory training in medical education: students’ perspective. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2016;3:195–8.

Nikendei C, Huber J, Stiepak J, Huhn D, Lauter J, Herzog W, et al. Modification of Peyton’s Four-Step Approach for small group teaching – a descriptive study. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:1–8.

Ahmed FR, Morsi SR, Mostafa HM. Effect of Peyton’s Four Step Approach on skill acquisition, self-confidence and self - satisfaction among critical care nursing students. IOSR-JNHS. 2018;6:38–47.

Krauter M, Weyrich P, Schultz JH, Buss SJ, Nikendei C, Junger J, et al. Effects of Peyton’s Four-Step Approach on objective performance measures in technical skills training: a controlled trial. Teach Learn Med. 2011;3:244–50.

Kernan WD, Basch CH, Carodett V. Using mind mapping to indentify reserach topics: a llesson for teaching research methods. Pedagogy Health Promot. 2017; doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/2373379917719729 .

Buran A, Filyukov A. Mind mapping tehnique in language learning. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2015;206:215–8.

Noonan M. Mind maps: enhancing midwifery education. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;8:847–52.

D’Antoni AV, Zipp GP, Olson VG, Cahill TF. Does the mind map learning strategy facilitate information retrieval and critical thinking in medical students? BMC Med Educ. 2010; doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-10-61 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Vilela VV, Pereira Barbosa LC, Miranda Vilela AL, Santos Neto LL. The use of mind maps as support in medical education. J Contemp Med Edu. 2013;4:199–206.

Rosciano A. The effectiveness of mind mapping as an active learning strategy among associate degree nursing students. Teach Learn Nurs. 2015;2:93–9.

Karnjuš I, Križmarić M, Zazula D. Importance of debriefing in high-fidelity simulations. Slov Med J. 2014;3:246–54.

Vieira Janicas RCS, Zanon Narchi N. Evaluation of nursing students’ learning using realistic scenarios with and without debriefing. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2019;27:e3187.

Clark CA. Evaluating nurse practitioner students through objective structured clinical examination. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2015;1:53–4.

Hermansyah D, Witansa R. Influence of use of mind mapping method by teachers on teaching preparation in basic school in subject of materials teaching eyes lesson science natural science (IPA). Journal Elementary Educ. 2017;1:37–52.

Lloyd D, Boyd B, Den Exter K. Mind mapping as an interactive tool for engaging complex geographical issuess. New Zealand Geographer Society. 2010; doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7939.2010.01185.x .

Zipp GP, Maher C, D’Antoni AV. Mind mapping: teaching and learning strategy for physical therapy curricula. J Phys Ther Educ. 2015;1:43–8.

Luo J. Teaching mode of thinking development learning based on mind mapping in the course of health fitness education. iJET. 2019;8:192–205.

Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. London, New Delhi: Sage Publications; 2004.

European Union. Directive 2005/36/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council. 2005. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do? uri = OJ:L:2005:255:0022:0142:en:PDF. Accessed 17 Jul 2013.

European Union. Directive 2013/55/EU of the European Parlament of the Council. 2013. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ: L:2013:354:0132:0170:en:PDF. Accessed 9 Jan 2016.

Skela-Savič B. Smernice za izobraževanje v zdravstveni negi na študijskem programu prve stopnje Zdravstvene nege (VS). Obzor Zdrav Neg. 2015;4:320–33.

Clarke A. Focus group interviews in health-care research. Prof Nurs. 1999;14:395–7.

CAS Google Scholar

Bolderston A. Conducting a research interview. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2012;43:66–76.

Polgar S, Thomas SA. Introduction to research in the health sciences. 4th ed. Oxford: Churchill Livingstone: 2000.

Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16:1–13.

Maher C, Hadfield M, Hutchings M, de Eyto A. Ensuring rigor in qualitative data analysis: a design research approach to coding combining NVivo with traditional material methods. Int J Qual Methods. 2018; doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918786362 .

Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Effective evaluation: improving the usefulness of evaluation results through responsive and naturalistic approaches. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1981.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

Hardavella G, Aamli-Gaagnat A, Saad N, Rousalova I, Sreter KB. How to give and receive feedback effectively. Breathe. 2017; doi: https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.009917 .

Ratna H. The importance of effective communication in healthcare practice. Harvard Public Health Review. 2019;23.

Bodys-Cupak I, Łatka J, Ziarko E, Majda A, Zalewska-Puchała J. Medical simulation with simulated patients in the education of Polish nursing students - pilot study. Polish Nurs. 2020;3:166–73.

Christianson KL. Emotional intelligence and critical thinking in nursing students: integrative review of literature. Nurse Educ. 2020;6:E62-E65.

Kanbay Y, Okanlı A. The effect of critical thinking education on nursing students’ problem-solving skills. Contemp Nurse. 2017;3:313–21.

Haakma I, Janssen M, Minnaert A. Understanding the relationship between teacher behavior and motivation in students with acquired deafblindness. Am Ann Deaf. 2016;161:314–26.

Al Naqbi S. The use of mind mapping to develop writing skills in UAE schools. Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues. 2011;2:120–33.

Baksi A, Gumus F, Zengin L. Effectiveness of the preparatory clinical education on nursing students anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Caring Sci. 2017;2:1003–12.

Nyström S, Dahlberg J, Edelbring S, Hult H, Dahlgren MA. Debriefing practices in interprofessional simulation with students: a sociomaterial perspective. BMC Med Educ. 2016; doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0666-5 .

Kalyanasundaram M, Abraham SB, Ramachandran D, Jayaseelan JB, Singh Z, Purty AJ. Effectiveness of mind mapping technique in information retrieval among medical college students in Puducherry – apilot study. Indian J Community Med. 2017;19:19–23.

Picton C. Mind maps: reflecting on nature. Emerg Nurse. 2009; doi: https://doi.org/10.7748/en.17.2.3.s1 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Lillekroken D. A privilege but also a challenge.“ Nurse educators’ perceptions about teaching fundamental care in a simulated learning environment: A qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2020;11/12: 2011–22.

van Wyngaarden A, Leech R, Coetzee I. Challenges nurse educators experience with development of student nurses’ clinical reasoning skills. Nurse Educ Pract. 2019; doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2019.102623 .

World Medical Association. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ 2013. Accessed 12 Feb 2020.

Kodeks etike v zdravstveni negi in oskrbi Slovenije. 2014. http://www.kme-nmec.si/files/2018/03/Kodeks-etike-v-zdravstveni-negi-in-oskrbi-Slovenije-marec-2014.pdf . Accessed 12 Feb 2020.

Social Resarch Association Research Ethics Guidance. 2003. ethical guidelines 2003.pdf (the-sra.org.uk). Accessed 12 May 2019.

Social Resarch Association Research Ethics Guidance. 2021. https://the-sra.org.uk/common/Uploaded%20files/Resources/SRA%20Research%20Ethics%20guidance%202021.pdf . Accessed 14 Jun 2021.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Strengthening Nursing in BiH Project for inviting us to participate in the provision of training as a part of the education module: Clinical skills of mentors that enabled us to conduct the research among the training participants after completing the training. We would also like to thank all the participants of the research, who shared their opinions and views about the presented issue.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Angela Boškin Faculty of Health Care, Spodnji Plavž 3, SI-4270, Jesenice, Slovenia

Sanela Pivač, Brigita Skela-Savič & Sedina Kalender-Smajlović

Faculty of Medicine, Department of Health Care, University of Banja Luka, Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Duška Jović

Public Institution Health Centre of Sarajevo Canton, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Mediha Avdić

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SP contributed to the conception and design of the study, definition of sample, theoretical introduction and discussion, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. BSS contributed to the design of the study, theoretical introduction, methods, final reading of article. DJ contributed to the theoretical introduction and discussion and acquisition of data. MA contributed to the theoretical introduction and discussion and acquisition of data. SKS contributed to the theoretical introduction, analysis and interpretation of data discussion and conclusions. All authors drafted the manuscript and approved of the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sanela Pivač .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

In order to conduct the research, we received a written consent from all the research participants. We ensured the anonymity of all the research participants. Informed consent was obtained. The participants received information about different aspects of the study; their rights on voluntary participation and withdrawal from the study at any time as well as their privacy and confidentiality rights were explained to them. Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the Senate Committee for Science, Research and Development at the Angela Boškin Faculty of Health Care in August 2019. We obtained the consent from the Fami Foundation for improving Health Care and Social Welfare.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Pivač, S., Skela-Savič, B., Jović, D. et al. Implementation of active learning methods by nurse educators in undergraduate nursing students’ programs – a group interview. BMC Nurs 20 , 173 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00688-y

Download citation

Received : 27 May 2021

Accepted : 28 August 2021

Published : 18 September 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00688-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Nursing education

- Teaching tools

- Critical thinking

- Communication skills

BMC Nursing

ISSN: 1472-6955

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 16 March 2024

Clinical virtual simulation: predictors of user acceptance in nursing education

- José Miguel Padilha 2 nAff1 ,

- Patrício Costa 3 , 4 , 5 ,

- Paulino Sousa 6 &

- Ana Ferreira 7

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 299 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

27 Accesses

Metrics details

Using virtual patients integrated in simulators expands students’ training opportunities in healthcare. However, little is known about the usability perceived by students and the factors/determinants that predict the acceptance and use of clinical virtual simulation in nursing education.

To identify the factors/determinants that predict the acceptance and use of clinical virtual simulation in learning in nursing education.

Observational, cross-sectional, analytical study of the use of clinical virtual simulation in nursing to answer the research question: What factors/determinants predict the acceptance and use of a clinical virtual simulator in nursing education? We used a non-probabilistic sampling, more specifically a convenience sample of nursing degree students. The data were collected through a questionnaire adapted from the Technology Acceptance Model 3. In technology and education, the Technology Acceptance Model is a theoretical model that predicts the acceptance of the use of technology by users.

The sample comprised 619 nursing students, who revealed mean values of perceived usefulness (M = 5.34; SD = 1.19), ease of use (M = 4.74; SD = 1.07), and intention to use the CVS (M = 5.21; SD = 1.18), in a Likert scale of seven points (1—the worst and 7 the best possible opinion).

This study validated the use of Technology Acceptance Model 3 adapted and tested the related hypotheses, showing that the model explains 62% of perceived utility, 32% of ease of use, and 54% of intention to use the clinical virtual simulation in nursing by nursing students. The adequacy of the model was tested by analysis of the direct effects of the relationships between the internal constructs (PU-BI, β = 0.11, p = 0.012; PEOU-BI, β = -0.11, p = 0.002) and the direct relations between some of the constructs internal to the Technology Acceptance Model 3 and the external determinants Relevance for learning and Enjoyability.

In the proposed model, the external constructs that best predicted perceived usefulness, ease of use, and behaviour intention to use the clinical virtual simulation in nursing were Relevance for learning and Enjoyability.

Conclusions

These study results allowed us to identify relevance for learning and enjoyability as the main factors/determinants that predict the acceptance and use of clinical virtual simulation in learning in nursing.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The rapid transformation of society in recent decades and the technical and scientific advancements in health sciences continually challenge higher education institutions (HEIs) to innovate, develop, and implement new pedagogical methodologies that guarantee up-to-date and quality training. Translating knowledge into clinical practice has become one of the main challenges of the first decades of the twenty-first century in research and higher education in health [ 1 , 2 ]. The higher education institutions have been systematically confronted with the difficulty of teaching central and structuring concepts of clinical practice and difficulty in translating these concepts into clinical practice [ 1 , 2 ]. Since the 1950s, multiple pedagogical strategies have been developed and implemented, such as Problem-Based Learning. These strategies intend to help students develop cognitive, instrumental, and attitudinal skills (Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes), among others, as structuring elements to ensure the quality and safety of their clinical practice. Quality and safety in clinical practice are associated with intrinsic and extrinsic factors for healthcare professionals. Of the intrinsic factors, clinical decision-making skills stand out. The development of clinical decision-making skills in healthcare students is one of the biggest challenges posed to higher education institutions teachers [ 3 ]. This becomes more evident in pre-graduate training with students without clinical experience. In addition, from a student's point of view, this is also one of the main challenges faced. Learning in the healthcare field implicates the need to ensure the quality and safety of the decision in each action, usually linked to fear of making mistakes, causing harm to the patient and, consequently, likely to negatively impact students’ mental health [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. Thus, it is crucial to develop, implement and evaluate strategies that enable or recreate clinical environments and clinical decision scenarios before tutored or autonomous clinical practice. These environments must recreate spaces of high realism and fidelity creating friendly learning environments and recreating emotionally safe but simultaneously challenging spaces where students can build their learning [ 8 ].

The educational strategies traditionally used in health have almost reached their highest potential, thus stimulating innovation through new andragogical strategies that support the interaction of those involved in learning in enhancing active learning and capturing the intrinsic motivation of students, directing them to the translation of knowledge, enabling more meaningful learning, and leading to greater perception of effectiveness and less likelihood of clinical error [ 3 , 8 ].

In the last decades, simulation in health has emerged as a pedagogical strategy whose evidence demonstrates improved knowledge retention, instrumental, relational and communication skills, leadership and teamwork skills, and the transference of competencies [ 9 , 10 , 11 ].

- Clinical virtual simulation

Currently, the technological development in information and communication technologies allows to recreate patients and clinical conditions in virtual learning environments. These virtual patients are computer programs that simulate real-life clinical scenarios in which students act as health professionals, collecting the clinical history, performing the physical examination, defining the diagnosis, the intervention to be implemented, and evaluating the outcome of the clinical decision. Virtual simulation is defined as a type of simulation that places the student at the centre of decision-making, motor and/or communication skills [ 12 ].

The use of virtual patients in a virtual healthcare environment to train clinical reasoning and/or clinical decision-making skills has been defined as clinical virtual simulation (CVS) [ 13 , 14 ]. Using virtual patients in education effectively improves knowledge, critical thinking, clinical reasoning, instrumental skills, self-efficacy perception, learning satisfaction, interaction and feedback, teamwork, learning experience, and realism of simulation spaces, making them emotionally safer [ 13 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ].

The increased use of clinical virtual simulation in recent years in health education was boosted during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the recognition achieved during these pandemic years, little is known about the factors that influence the acceptance by students of the use of clinical virtual simulation.

In 2016, the Nursing School of Porto began developing clinical virtual scenarios in Nursing to be integrated into the clinical virtual simulator Body Interact® (BY).

The use of clinical virtual simulation in the Nursing Degree as an andragogical strategy began in 2018–2019. Since then, studies have been conducted on usability [ 13 , 25 ], knowledge retention, satisfaction and learning perception [ 14 ], the impact on learning in small groups, and the perception of curricular integration [ 26 ].

However, further investigation is needed regarding the factors that promote the adoption and use of clinical virtual simulation by students. The use of clinical virtual simulation as an integrated pedagogical strategy in a health degree implies the reorganization of the curricular plans and the introduction of andragogical strategies directed to enhancing active learning and capturing the intrinsic motivation of the student to learn [ 8 ].

The technology acceptance model

In technology and education, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) is a theoretical model that predicts the acceptance of the use of technology by users [ 27 ]. This model was developed by Davis F.D. (1989) [ 28 ], to which were added the determinants of perceived utility by Davis & Venkatesh (2000) [ 29 ] and the determinants of ease of use by Venkatesh V. (2000) [ 30 ]. More recently, Venkatesh V. & Bala H. (2008) developed an integrated Technology Acceptance Model 3 (TAM3) including a structure of the individual determinants for the adoption and use of technology.

Based on the TAM3 [ 31 ], this study sought to identify the factors/determinants that predict the use of clinical virtual simulation in nursing education.

Methodology

An observational, cross-sectional, analytical study of the use of clinical virtual simulation was carried out to answer the research question: What factors/determinants predict the acceptance and use of a clinical virtual simulator in nursing education? (Table 1 ).

Selection of participants

All students of the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th year of the Nursing Degree in the Nursing School of Porto (ESEP) ( n = 870) were invited to participate in this study.

Considering all items related to TAM, with a count of 62 items, and applying the rule of thumb suggested by Nunnally (1978) [ 32 ] of 10 cases per variable, the recommended sample size would be 620 participants.

Following a non-probabilistic sampling methodology, a convenience sample of nursing students was selected, who voluntarily agreed to participate, and following the inclusion/exclusion criteria:

Inclusion criteria: ESEP degree students who completed attendance, with or without success, of the curricular unit Body Responses to Disease 1 (RCD 1) in the academic years 2019–2020, 2020–2021, and 2021–2022.

Exclusion criteria: ESEP degree students who have not attended the curricular unit Body Responses to Disease 1 in the academic years 2019–2020, 2020–2021, and 2021–2022, and students who obtained accreditation to the curricular unit.

In our study, the actual sample size is n = 619 participants. It's important to note that we do not conduct a unified analysis for all 62 items. Therefore, our sample size is similar to the calculated requirement, providing a robust foundation for the statistical analyses employed in our study.

Ethical considerations

The ESEP’s ethics committee granted authorisation for the study 697/2022 and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data collection

Data were collected through a questionnaire adapted from the Technology Acceptance Model 3 [ 31 , 33 ].

The variables under study are defined in Tables 2 and 3 .

For the translation and validation into European Portuguese of the Technology Acceptance Model 3, authorization was granted from the authors and the following steps were carried out [ 33 , 34 ]:

Stage I – Initial translation

Translation 1 from English into Portuguese performed by a professional Portuguese native translator (without knowledge of the TAM3);

Two translations by Portuguese native speakers, one trained in the field of Computer Sciences (without knowledge of the TAM3) (Translation 2) and one healthcare professional with experience using the TAM3 and clinical virtual simulation (Translation 3), both proficient in English.

Stage II—Synthesis of translations Translation 1, 2 and 3

Production of the Translation final version 1 (Researcher, two native Portuguese speakers, one from the health area with experience in the use of clinical virtual simulation and the TAM3 and another from the area of Computer Sciences—different from the participants in stage I);

Stage III—Back-translation by two English native speakers (without medical background).

Stage IV—Analysis by an expert group with experience in the use of the TAM3 and virtual simulation in nursing education

Semantic equivalence (adapted to the clinical virtual simulation);

Ideological equivalence;

Experiential equity;

Conceptual equivalence.

Stage V—Pre-test of the pre-final version with a group of 10 students who were not included in the study sample.

Final version—The authors waived submission of the version for evaluation and approval.

Data were collected between May and July 2022.

Data analysis

In the initial phase, frequencies and descriptive statistics were extracted from all the collected variables. This approach allowed the analysis of the distribution of variables, evaluating the sensitivity of items (used to evaluate latent constructs) and detecting potential atypical values (outliers). Then, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of the distribution of variables, and values of asymmetry and kurtosis were used to assess the degree of separation of variables from normal distribution. The main psychometric properties of the different dimensions of the TAM3 were studied. Different validity criteria (criterion and construct validity) were applied considering best practices [ 35 ] and the evaluation of their internal consistency. To evaluate the constructs internal to the TAM3 and external (individual determinants), exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed to define the factors associated with the constructs of the TAM3. Subsequently, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was employed to verify whether the items of each scale saturated the identified factors. Path analysis was used to determine the main predictors (and relevant interactions between predictors) of the intention to use clinical virtual simulation in learning, the main dependent variable to model. This analysis included other variables besides its immediate predictors, such as the perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. Different mediation models were also developed to test whether some of the explored variables inhibited the relationship between the most relevant variables of the TAM3.

The data related to the global score variables of utilization (GS) and system utilization (SU) were extracted from the Learning Management System (LMS) of the clinical virtual simulation. The global score variable refers to the average overall evaluation obtained by the student in clinical virtual simulation utilization regarding his/her clinical decision-making skills, measured in percentage of success. The system utilization variable (SU) refers to the total number of clinical scenarios the student completed in the clinical virtual simulation.

Statistical analysis was performed using JASP, Jamovi, IBM SPSS Amos v.26, and IBM SPSS Statistics v. 26. The results are reported following the APA standards, presenting the magnitude measurements of the Cohen d effect (0.2 low; 0.5 medium, and 0.8 high) and considering of P < 0.05 as significant. In the confirmatory factor analysis, the criteria applied to evaluate the adjustment of the model were the χ2 value and its p-value, ideally nonsignificant, the CFI > 0.95, GFI > 0.90 and RMSEA > 0.03 and < 0.08 [ 36 ]. In the analysis of the convergent validity of the items internal to the TAM3, the reliability value of the construct (CR) > 0.8, the mean extracted variance (AVE) > 0.5 [ 36 ], and factor loads in inter-correlation items lower than the square root of the AVE for each construct were the adopted criteria [ 37 ].

A total of 619 Nursing students participated in this study, being 85.50% ( n = 531) female, 35.1% ( n = 218) 2nd-year students; 36.2% ( n = 225) 3rd-year students; and 28.7% ( n = 178) 4th-year students. Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics of the sample, and Table 5 the correlation matrix of age, course marks, number of completed scenarios and mean global evaluation score.

Analysis of the acceptance of the use of CVS by the TAM3

Descriptive analysis of the items, followed by the exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and trajectories analysis, were performed sequentially to investigate the acceptance of the use of the CVS and to identify the factors that determine the acceptance and use of the clinical virtual simulation in nursing education, as presented below.

Descriptive analysis of the items of the TAM3

The descriptive results of the Technology Acceptance Model 3 items, organised according to the constructs internal to the TAM and the individual determinants (constructs external to the TAM).

Exploratory factor analysis of the TAM

After the descriptive analysis of the data, the internal constructs associated with the Technology Acceptance Model 3 (PU-perceived usefulness; PEOU-perceived ease of use and BI-Behaviour intention to use) were analysed. Firstly, the EFA, using the Axis Factoring Main method, the Oblimin rotation method and the Kaiser Normalization criterion (KMO = 0.894, and Bartlett’s sphericity test < 0.001) were applied to analyse whether the items presented adequate factor loadings in each construct of the Technology Acceptance Model 3. The EFA allowed to identify three factors associated with the internal constructs of the Technology Acceptance Model 3 that explain 74.6% of the total variance of the data and present an adequate internal consistency (Table 6 ).

Then, EFA was performed with the items of individual determinants of the TAM3 (e.g., CSE-Self-efficacy in the use of CVS; PEC-Perception of external control; CPLAY-Perceived playfulness in the use of CVS; CANX-Anxiety with the use of CVS; ENJ-Enjoyability associated with the use of CVS) to analyse whether the items revealed adequate factor loadings in each individual determinants of the TAM3. In the EFA, the principal axis factoring method was used with the Oblimin rotation, and the Kaiser Normalization criterion for factor extraction. To analyse the adequacy of the data to perform the EFA, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test (KMO) was performed considering a value greater than 0.8 as meritorious [ 38 ] and the Bartlett’s Sphericity test p < 0.05 to test the relationship between the variables (KMO = 0.879; Bartlett’s sphericity test < 0.001). The EFA allowed to identify ten factors that explained 59.4% of the total variance of the data. However, items OUT_2_TAM34; CANX_1_TAM13; CPLAY_4_TAM47; PEC_4_TAM12; SN_3_TAM22; SN_4_TAM23; CPLAY_4_TAM47; PEC_4_TAM47; PEC_4_TAM12; SN_TAM23; SN_4_TAM3; SN_TA3; SN_2_TA3; SN_TAM3; SN_TAM3; SN_TAM3; SN_TAM3; SN_TAM3; SN_TAM3; SN_TAM33; SN_2_TAM3; SN_TAM3; SN_TAM3; SN_TAM3; SN_TAM_TAM3; SN_TAM3; SN_TAM33; SN_TAM3; SN_TAM3 presented factor loadings < 0.3 [ 36 ] or cross factor loadings in more than one factor, so they were excluded from the analysis. We performed a second EFA excluding the problem items described (KMO = 0.867; Bartlett’s sphericity test < 0.001). This analysis allowed to identify eight factors that explain 68.64% of the variance of the data. However, we verified that items PEC_2_TAM10, PEC_3_TAM11, and PEC_1_TAM9 had factor loadings < 0.3 or cross-factor loadings in more than one factor, so they were excluded from the analysis. Excluding these items, we performed a new EFA (KMO = 0.856; Bartlett’s Sphericity test < 0.001) that identified 7 factors, explaining 63.1% of the total variance of the data and presenting adequate internal consistency (Table 7 ).

Confirmatory factor analysis of the TAM

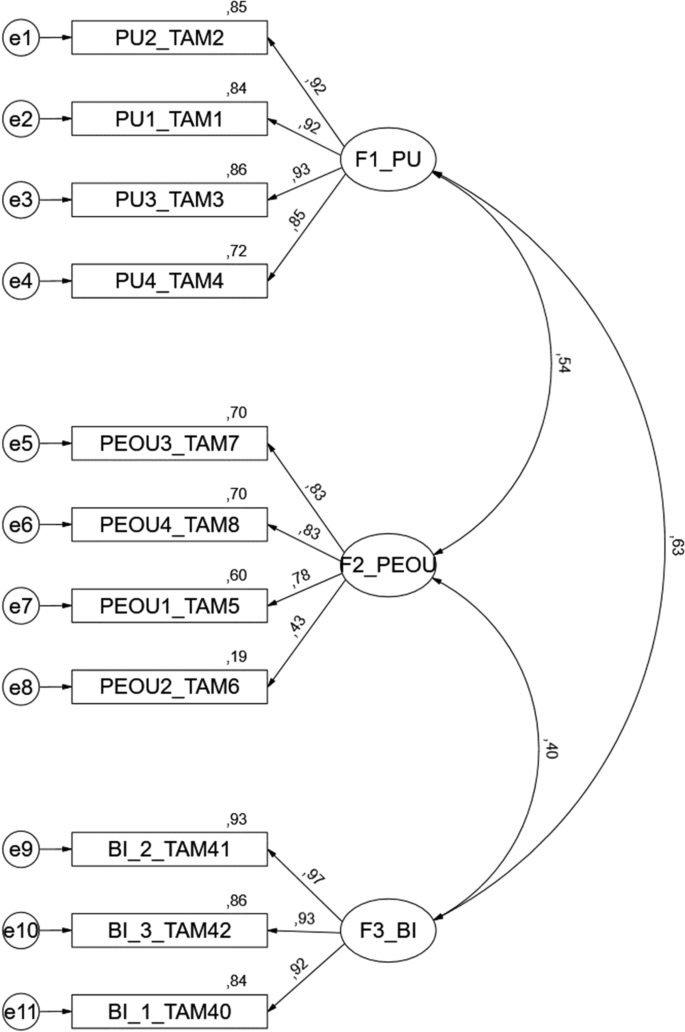

Once the factorial structure of the Technology Acceptance Model 3 was defined for this study, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to validate the constructs internal to the Technology Acceptance Model 3 (Perceived usefulness, Perceived ease of use, and Behaviour intention to use), although ideally, this analysis requires a new sample. The results revealed acceptable adequacy of the model (Fig. 1 ) [(χ2(41) = 178, P < 0.001, CFI = 0.976, PCFI = 0.727, GFI = 0.948; PGFI = 0.589, RMSEA = 0.075; p (rmsea 0.05) < 0.001)]. Table 8 presents the results of the construct’s validity.

CFA model of factors internal to the TAM3. Footnote: F1-PU-Perceived usefulness; F2-PEOU-Perceived ease of use; F3-BI-Behaviour intention to use

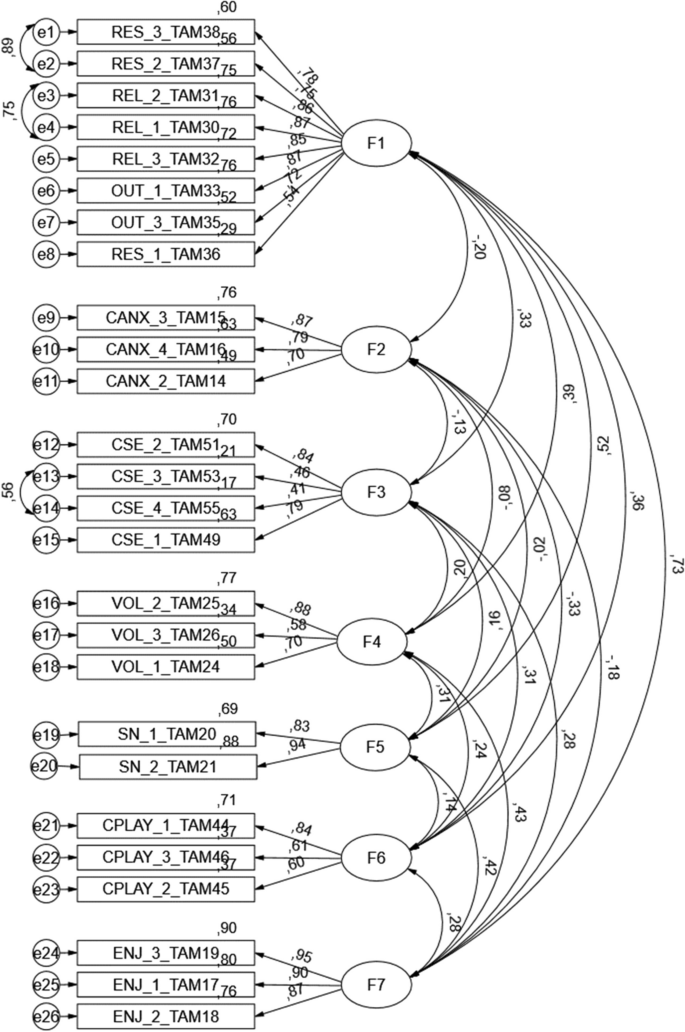

The analysis of Table 9 shows the appropriateness of convergent and discriminant validity of the proposed model (Fig. 1 ). CFA was performed to validate the constructs associated with the determinants external to the Technology Acceptance Model 3 (REL-Relevance for learning; CANX-Anxiety with the use of CVS; CSE-Self-efficacy in the use of CVS; VOL-Voluntariness; PEC-Perception of external control; SN-Subjective Norm; CPLAY-Perceived playfulness in the use of CVS; ENJ-Enjoyability associated with the use of CVS) (Fig. 2 ). The results showed an acceptable fit to the model [(χ2(275) = 621, P < 0.001, CFI = 0.949, PCFI = 0.803, GFI = 0.888; PGFI = 0.695, RMSEA = 0.057; p (rmsea 0.05) = 0.025)]. Table 10 shows the construct validity results, with all items, except CSE_4_TAM55, presenting factorial loads greater than 0.5, revealing an acceptable convergent validity [ 36 ].

CFA model of the individual determinants of TAM 3. Footnote: F1-REL-Relevance to learning; F2—CANX—Anxiety with the use of CVS; F3—CSE—Self-efficacy in the use of CVS; F4—VOL—Voluntariness; F5—SN—Subjective Norm; F6—CPLAY—Perceived Playfulness in the use of CVS; F7—ENJ—Enjoyability associated with the use of CVS

The errors of the items with higher modification index values were correlated to improve the adjustment of the model. More specifically, a correlation was established between the following items: RES_3_TAM38 and RES_2_TAM37; REL_2_TAM31 and REL_1_TAM30; CSE_3_TAM53, and CSE_3_TAM55. This decision was based on the content similarity presented by the correlated items.

The convergent validity of the individual determinant items of the TAM3, a Construct Reliability (CR) revealed a value greater than 0.73, an Average Extracted Variance (AVE) greater than 0.42 [ 36 ], and factorial loadings in the inter-item correlation lower than the square root of the AVE for each construct [ 38 ], highlighted bold in Table 11 above the diagonal. The global analysis indicates the appropriateness of convergent and discriminant validity of the proposed model.

Trajectory analysis

In the proposed model, the items’ global average score of evaluation of the use of the virtual simulator (GS) and those related to the use of clinical virtual simulation (SU) were not considered (Table 12 ), given the high number of missing values (higher than 30%) that negatively influenced data quality and weakened the proposed model. The high number of missing values is justified by the participation in this sample of 4th-year students who attended the curricular unit Body Responses to Disease 1 in 2019–2020, an academic year in which it was not possible to extract the variables per student from the LMS.

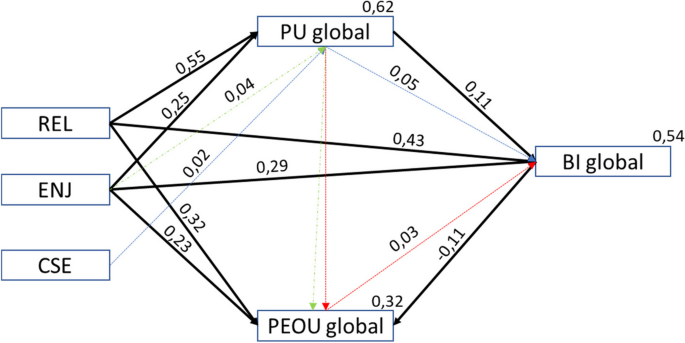

Trajectory analysis was used to analyse the adequacy of the TAM3 adapted to assess the acceptance of the use of clinical virtual simulation. Table 13 summarises the tested hypotheses. Figure 3 represents the standardised constructs coefficients of the model and coefficients of determination ( R 2 ) associated with the modelling of the dependent variables. The model presents values of [(χ 2 (5) = 7.22, p = 0.205, CFI = 0.999, PCFI = 0.111, GFI = 0.998; PGFI = 0.091, RMSEA = 0.027; p (rmsea 0.05) = 0.789)]. In Fig. 3 , the proposed model explains a high variance of perceived usefulness ( R 2 = 62%), intention to use the CVS ( R 2 = 54%), and a lower variance of ease of use ( R 2 = 32%).

Model proposed for the acceptance of the technology for CVS (TAM3CVS_MP). Legend: REL-Relevance for learning; CSE-Self-efficacy in the use of CVS; ENJ-Enjoyability associated with the use of CVS; Black lines in Bold—direct effects; Dashed lines (blue/green and red)—indirect effects

Table 13 shows that the defined hypotheses related to the internal constructs and the individual determinants of the TAM3 regarding the acceptance of the clinical virtual simulation, the perceived usefulness (PU), the perceived ease of use (PEOU) and the behaviour intention to use (BI)], are influenced by Relevance for learning (REL) [REL → PU ( β = 0.55; P < 0.001), REL → PEOU ( β = 0.32; P < 0.001), REL → BI ( β = 0.43; P < 0.001)], and Enjoyability (ENJ) [ENJ → PU ( β = 0.25; P < 0.001), ENJ → PEOU ( β = 0.23; P < 0.001), ENJ → BI ( β = 0.29; P < 0.001)]. The remaining hypotheses were not supported in this study.

Table 14 shows the standardised indirect effects of the Model proposed for the acceptance of the technology for CVS (TAM3CVS_MP).

The participants showed mean values of perceived usefulness (M = 5.34; SD = 1.19), ease of use (M = 4.74; SD = 1.07), and behaviour intention to use the clinical virtual simulation (M = 5.21; SD = 1.18), indicating the acceptance of the use of clinical virtual simulation in nursing education.

This study validated the use of the Technology Acceptance Model 3 adapted to clinical virtual simulation and tested the related hypotheses, showing that the model explains 62% of perceived usefulness, 32% of ease of use, and 54% of behaviour intention to use the clinical virtual simulation by nursing students. The adequacy of the model was tested by analysing the direct effects of the relationships between the internal constructs (PU → BI, β = 0.11, P = 0.012; PEOU → BI, β = -0.11, P = 0.002) and direct relations between some of the constructs internal to the TAM and the external determinants, Relevance for learning and Enjoyability. Also, the adequacy of the proposed model was determined by analysing the indirect effects of self-efficacy in the use of clinical virtual simulation (CES) on BI ( P = 0.05) through PU ( P = 0.02) and the indirect effect on Enjoyability (ENJ) on PU through PEOU ( P = 0.044) and the indirect effect of PU on BI through PEOU ( P = 0.026).

In sum, regarding the technology acceptance model for clinical virtual simulation, the internal constructs that predicted the intention to use were perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. However, perceived ease of use emerges as new its inverse relationship with the behaviour intention to use. This fact finds no parallel in the evidence [ 33 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 ]. This data points out that the responses expressed by the students are not related to the ease of use inherent to technology but rather to the cognitive performance necessary for the resolution of clinical scenarios and the training of clinical decision-making skills. Thus, the greater the perception of ease of use in a perspective of greater competence in the clinical decision-making process, the lower the intention to use the clinical virtual simulation. These data also reveals the need for clinical scenarios to present an increasing level of complexity according to the development of clinical decision-making skills.

In the proposed model, Relevance for learning (REL) and Enjoyability (ENJ) were the external constructs that best predicted perceived usefulness, ease of use, and behaviour intention to use clinical virtual simulation. This is in line with some of the findings of a meta-analysis by Rosli M.S et al. (2022) [ 43 ], the study of the adequacy of the Technology Acceptance Model 3 to virtual reality by Jiang, M et al. [ 39 ], and the study on the acceptance of computer games as an educational strategy, where Relevance for learning was also identified as one of the best predictors of perceived usefulness and/or ease of use by Lemay, D. J et al. [ 41 ].

The decision on the behaviour intention to use the clinical virtual simulation should consider three indirect effects identified:

The self-efficacy in the use of the clinical virtual simulation (CVS) indirectly predicts the behaviour intention to use the CVS through the moderation of perceived usefulness. This emphasises the need to optimise the support to students with less perceived self-efficacy in the use of CVS;

Enjoyability predicts ease of use of CVS through moderation of perceived usefulness. This fact points to the perception of enjoyability having a positive influence on the perceived usefulness, which positively influences the ease of use of the CVS. Also, this demonstrates that the increased Enjoyability associated with use can help overcome some of the complexity perceived by the student in the use of CVS;

The perceived usefulness predicts the behaviour intention to use CVS through moderation of perceived ease of use. These data point out that a greater utility perceived by the student in the use of CVS helps overcome some of the complexity perceived in the use of CVS in clinical reasoning training.

The analysis of the descriptive data associated with each construct internal to the TAM3 and the individual determinants showed average scores ranging between 4.14–5.59, except for Anxiety related to the use of the CVS, with an average score of 1.5, indicating its low perception by the students. The average self-efficacy score of the use of CVS (M = 6.72) is explained by the fact that it is evaluated on a 10-point Guttman scale. The lowest average score observed is for the subjective norm, indicating that it is not the influence of other people, particularly teachers, that determined the use of CVS by students. Regarding the voluntary use of CVS, data should be interpreted with caution since items TAM25 (M = 4.71) and TAM26 (M = 4.34) revealed a low perception of obligation perceived by the student to use the CVS, while item TAM24 (M = 5.24) showed a higher value associated to the voluntary use of the CVS. Regarding the ease of use, item TAM6 (M = 4.06) revealed that the use of CVS did not require much effort, as opposed to item TAM7 (M = 5.10), expressing the ease of use.

These are innovative results as they highlight the positive influence that the relevance attributed to learning and development of clinical reasoning and clinical decision-making skills (Learning Relevance) have on the perception of ease of use, perceived usefulness in the use of CVS, and the effective use of CVS. These results are associated with the relevance attributed by the student who views the use of CVS as linked to the triggering of emotions such as enjoyability, a fact previously determined as a variable to adjust the use of technology by Venkatesh V. & Bala H. (2008) [ 31 ] but still little explored by Kim, S et al. [ 44 ]. This study shows that the use of CVS, ease of use, and usefulness are influenced by the positive representation that the student has of the contribution to their training as a future nurse. Also, these study results demonstrate that the use of CVS creates a playful context that helps students learn actively in a friendly environment, bringing aspects of gamification that help them set goals, get scores, and compare results between students [ 44 , 45 ] while simultaneously anticipating clinical challenges. Using game elements added to the CVS contributes to developing intrinsic motivation [ 46 ] and satisfaction with the learning process [ 8 ].

The use of CVS promotes students’ active learning and the capture of their intrinsic motivation through facilitated access to pedagogical resources according to the pacing and learning preferences of the students. This learning environment promotes autonomy, the development of effectiveness and belonging to a learning community, an environment in which the teacher is a facilitator of the learning process, and the student learns while having fun [ 46 , 47 , 48 ]. It can be argued that the motivation under analysis can be extrinsic [ 46 ] because it uses a perception of locus of internal causality associated with an integrated regulation process by anticipating the results that students may achieve, a fact represented by the construct Relevance for learning (REL). However, the construct Enjoyability clarifies the existence of intrinsic motivation based on interest and student satisfaction with the learning process using the CVS [ 46 ]. Thus, this study showed that a personal determinant of the student (REL) and an adjustment determinant (ENJ) are central to the use of CVS in nursing education.

Currently, the acceptance and adoption of CVS in Nursing education, in this context, goes beyond external variables to the student that may determine the adoption of CVS, for example, the influence of teachers and significant people or individual determinants related only to characteristics of CVS, for example, the effectiveness in the use of CVS, anxiety associated with the use of CVS, and playfulness. This study revealed that the current characteristics of pre-graduation students, who are digital natives [ 49 ], lead to features related to the use of technology that may be overcome by the nature of the learning outcomes anticipated by students.

In sum, this study produced interesting outcomes for nursing education in this context, affirming that the use of CVS in learning is directly determined by students’ perceived relevance and enjoyability. This positively influences the usefulness and perceived ease of use and consequently the behaviour intention to use the CVS. Perceived Self-efficacy indirectly predicted the behaviour intention to use CVS through moderation by perceived usefulness.

The results of this study require careful interpretation because they only represent a single context of nursing degree education and were implemented in one of the curriculum units of the syllabus. Notwithstanding, this study presents data that can support educators in the health field in making decisions or developing new studies, overcoming some of the limitations of this study.

Study limitations

The main limitations of this study were the use of the same sample of students to perform the EFA and CFA.

Another identified limitation was not having included the construct of the attitude referred to in other studies. This option was based on the expectation of having data related to the behaviour from the evaluation and use of the CVS. Also, the lack of data for the entire sample regarding the Global Scores of use and the number of completed scenarios per student conditioned the potential of the presented model. Thus, using this model in samples with these available data is recommended. This limitation stems from the fact that CVS is still little used as an andragogical strategy in health education.

This study provided noteworthy contributions to propose a technology acceptance model for clinical virtual simulation (TAM3CVS_MP), identifying the factors determining the acceptance and use of clinical virtual simulation by nursing students.