97 OCD Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best ocd topic ideas & essay examples, 🥇 most interesting ocd topics to write about, 📌 simple & easy ocd essay titles, ❓ ocd research questions.

- Intake Report and Treatment Plan: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) According to Joan, her whole life from childhood has been accompanied by her overambitious to achieve in every task, her conscientious nature, never-making mistakes behavior, and her avoidance to indicate the presence of a mistake […]

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder – Psychology This paper mainly addresses some of the characteristics of OCD, what contribute it, the kind of people who are likely to attract the disease, types of treatment of the disorder, and how it affects a […] We will write a custom essay specifically for you by our professional experts 808 writers online Learn More

- OCD: The Four D’s Diagnostic Indicators Firstly, obsessive thoughts often interfere with the usual people’s acts and cause a surge of panic, disturbing to complete their work.

- Freud’s Theory of Personality Development and OCD The ego, on the other hand, is in the middle and manages both the desires of the Id and those of the superego.

- The Obsessive-Compulsive Psychological Disorder In addition, the disorder affects the way he relates with the likes of Simon Bishop and the gay painter both of whom are his neighbors.

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in an Asian American Patient The issue of substance use should also be addressed as one of the possible factors that may have exacerbated the patient’s sense of anxiety and prompted the aggravation of her OCD.

- Discussion: Anxiety Disorder and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders To be diagnosed with a specific phobia, one must exhibit several symptoms, including excessive fear, panic, and anxiety. Specific phobias harm the physical, emotional, and social well-being of an individual.

- Case of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Overall, Robert does not have a dependency on other people when it comes to handling his OCD and prefers being on his own the majority of the time.

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder in Adults Obsessive Compulsive Disorder is an anxiety disorder that is represented by uncontrollable, repetitive and unwanted thoughts.

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder One of them is the Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder the syndrome which causes people to have recurring, unwanted thoughts and drives them to uncontrollable, repetitive actions.

- Neurotransmission and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder The proteins and the other substances that the neuron needs for its function are manufactured by the cell body or soma and the nucleus and the neuron is known as the “manufacturing and recyling plant”.

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in a Young Woman After Bess’s mother’s serious intervention into the course of her life, Bess was absorbed in her studies and later in her work.

- Psychodynamic and Cognitive-Behavioral Approaches of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder In this article, after overviewing both the psychodynamic and cognitive behavioral models of OCD, Kempke and Luyten point out that as opposed to the cognitive behavioral model, the arena of psychodynamic approach to OCD is […]

- Obsessive – Compulsive Personality Disorder: Diagnosis and Treatment Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder is the term used to refer to a mental condition in which a victim is too preoccupied with perfectionism, orderliness, and interpersonal and mental control, at the expense of efficiency, openness and […]

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Minor Psychiatric Illnesses However, the severe obsessive-compulsive disorder may lead to major incapacitation adversely affecting the life of the victims. When an individual exhibits or complains about obsession or compulsion or both to the extent that his normal […]

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Effective Treatment It is very true that due to the demands of the fast passed life most of the people suffer from stress.

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: Cognitive & Behavioural Formulations In most of the cases of OCD it is the rituals that end up controlling them. Even though most adults with OCD are aware of the fact that what they are doing is absurd, some […]

- Howard Hughes’s Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder The purpose of this paper is to discuss the obsessive-compulsive disorder in the case of Howard Hughes, with the help of the Big Five personality model.

- Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder and Care Hospitalization is a rare treatment method for patients who have an obsessive compulsory personality disorder. For instance, new drugs such as Prozac and SRRI are proved to offer a reprieve to patients suffering obsessive compulsory […]

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Analysis The behaviors are not realistically connected to the anxiety that the client tries to alleviate. Developmental Disorder: No diagnosis Rationale The client has a BA degree and is gainfully employed, which is evidenced by her […]

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Treatments Analysis The independent variable is the treatment method comprising CBT, BT, and NT while the dependent variables are the occurrences of actions and the occurrences of thoughts.

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Diagnostics Developmental Disorder: No diagnosis No diagnosis can be made since the woman used to be an active member of her community. Medical Disorder: No diagnosis The client maintains that she does not have medical issues.

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Its Causes While it is possible to clearly articulate the symptoms of OCD, the final and definite answer to the question about the causes of the disorder is yet to be found. Currently, it is hypothesised that […]

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Diagnosis and Therapy The ritual, i.e, the street corner, may be a response to an obsessional theme or a way to lower an underlying anxiety.

- Experience of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder The obsessive-compulsive disorder is a rather common psychiatric illness, which has a tendency to occupy a significant time in the mind of the patient and provides a feeling that he/she is not in control of […]

- Mindfulness Therapy for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder It is important to introduce the patient to the mindfulness intervention as early as possible by inviting him to take part in a 5-minute mindfulness-of-breath exercise in order to note particular reflections about the nature […]

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) – Psychology The other sign relates to the fear of lacking the need in life and consequently losing whatever has been acquired and is in possession.

- Psychological Issues: Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Nevertheless, the study showed that the majority of the correspondents who suffered from the disease were Judaism. Moreover, individuals suffering from the disorder refrain from visiting hospitals in fear of humiliation and guilt attributed to […]

- The Treatment of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder Thus, Madam Y is to be convinced of the therapist’s good intentions. Unconditional positive regard is also one of the most important ways which is to be used to help Madam Y.

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: Definition, Types and Causes Efforts to raise people’s awareness about OCD have been on the rise since the late 1990s and the first decade of the 21st century.

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatment Persistent thoughts and repetitive behaviors are major characteristics of the obsessive-compulsive disorder. Early, diagnosis, combined therapy and ability of the patient to regulate anxiety are critical in treatment of the obsessive-compulsive disorder.

- Brief Overview of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) The strange acts torment the mind and the distractions affect the social wellbeing of the patient. The brain has the “orbital frontal cortex” that is responsible of reporting and soliciting the rest of the brain […]

- Invasive Circuitry-Based Neurotherapeutics: Stereotactic Ablation and Deep Brain Stimulation for OCD

- Autism Spectrum Traits in Children and Adolescents With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Symptoms Predict Poorer Response to Gamma Ventral Capsulotomy for Intractable OCD

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Anxiety and OCD Spectrum Disorders

- Identical Symptomatology but Different Diagnosis: Treatment Implications of an OCD Versus Schizophrenia Diagnosis

- Childhood-Onset Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Tic-Related Subtype of OCD?

- Reduced Anterior Cingulate Glutamatergic Concentrations in Childhood OCD and Major Depression Versus Healthy Controls

- Neural Responses of OCD Patients Towards Disorder-Relevant, Generally Disgust-Inducing, and Fear-Inducing Pictures

- Dealing With Corona Virus Anxiety and OCD

- The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Patients With OCD

- Recent Life Events and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD): The Role of Pregnancy & Delivery

- Basic Neurotransmission and the Psychotropic Treatment of OCD

- The Characteristics, Common Symptoms, and Treatments of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), a Neurological Anxiety Disorder

- Social Factors That May Contribute or Result From OCD

- Are “Obsessive” Beliefs Specific to OCD?: A Comparison Across Anxiety Disorders

- Wisconsin Card Sorting Task (WCST) Errors and Cerebral Blood Flow in Obsessive‐Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

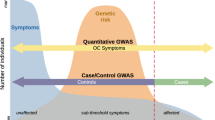

- Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) Between ADHD and OCD

- Treatment Non-response in OCD: Methodological Issues and Operational Definitions

- The Symptoms, Treatment, and Combination of Therapies for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- The Other Side of COVID-19: Impact on Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and Hoarding

- Should OCD Be Classified as an Anxiety Disorder in DSM‐V?

- Evaluation of Biological Explanations of OCD

- OCD in Children and Adolescents: A Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment Manual

- A New Infection-Triggered, Autoimmune Subtype of Pediatric OCD and Tourette’s Syndrome

- Parents With OCD and the Influences on Children

- Social Movements and Awareness and Educate the Public About OCD

- Hoarding in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Results From the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study

- Women Are at Greater Risk of OCD Than Men: A Meta-Analytic Review of Ocd Prevalence Worldwide

- Compulsive Hoarding: OCD Symptom, Distinct Clinical Syndrome, or Both?

- Does Comorbid Major Depressive Disorder Influence Outcome of Exposure and Response Prevention for OCD?

- Repeated Cortico-Striatal Stimulation Generates Persistent OCD-Like Behavior

- Quality of Life in OCD: Differential Impact of Obsessions, Compulsions, and Depression Comorbidity

- What Should the Diagnostic Criteria for OCD Be?

- Characterizing the Hoarding Phenotype in Individuals With OCD: Associations With Comorbidity, Severity, and Gender

- Compassion-Focused Group Therapy for Treatment-Resistant OCD: Initial Evaluation Using a Multiple Baseline Design

- High Rates of OCD Symptom Misidentification by Mental Health Professionals

- Widespread Structural Brain Changes in OCD: A Systematic Review of Voxel-Based Morphometry Studies

- Causes and Triggers for Obsessive Compulsive-Disorder (OCD)

- Distinct Subcortical Volume Alterations in Pediatric and Adult OCD: A Worldwide Meta- and Mega-Analysis

- Treating OCD With Exposure and Response Prevention

- What Is OCD Behaviour?

- What Are the Types of OCD?

- Is OCD a Form of Anxiety?

- What Causes OCD?

- What Are the Main Symptoms of OCD?

- Is OCD a Mental Disability?

- Can OCD Be Fully Cured?

- How Can You Tell if Someone Has OCD?

- What Happens if OCD Is Not Treated?

- Is OCD a Permanent Condition?

- How Long Does OCD Usually Last?

- What Are the Main Causes of OCD?

- How Many People With OCD Recover?

- What Does Undiagnosed OCD Look Like?

- Is OCD a Form of Addiction?

- Can OCD Be Triggered by Trauma?

- What Childhood Trauma Causes OCD?

- How OCD Takes the Living Out of Life?

- What Is Childhood and Adolescent OCD?

- How Is OCD Treated for Children With Compulsive Disorder?

- What Analysis of Genome-Wide Associations of Complications of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder?

- How Are OCD and Genes Related?

- Can OCD Cause Psychosis?

- Who Is Most Commonly Affected by OCD?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, March 2). 97 OCD Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/ocd-essay-topics/

"97 OCD Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 2 Mar. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/ocd-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2024) '97 OCD Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 2 March.

IvyPanda . 2024. "97 OCD Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/ocd-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "97 OCD Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/ocd-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "97 OCD Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/ocd-essay-topics/.

- Cognitive Therapy Essay Topics

- Mental Disorder Essay Topics

- Schizophrenia Essay Topics

- Anxiety Essay Topics

- Meditation Questions

- BPD Research Ideas

- Eating Disorders Questions

- Gambling Essay Titles

- Bipolar Disorder Research Ideas

- ADHD Essay Ideas

- Bulimia Topics

- Anorexia Essay Ideas

- Disorders Ideas

- Abnormal Psychology Paper Topics

- Dissociative Identity Disorder Essay Topics

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychiatry

Therapies for obsessive-compulsive disorder: Current state of the art and perspectives for approaching treatment-resistant patients

Kevin swierkosz-lenart.

1 Department of Psychiatry, Service Universitaire de Psychiatrie de l’Age Avancé (SUPAA), Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Prilly, Switzerland

Joao Flores Alves Dos Santos

2 Department of Mental Health and Psychiatry, Geneva University Hospital, Geneva, Switzerland

Julien Elowe

3 Department of Psychiatry, Lausanne University Hospital, University of Lausanne, West Sector, Prangins, Switzerland

4 Department of Psychiatry, Lausanne University Hospital, University of Lausanne, North Sector, Yverdon-les-Bains, Switzerland

Anne-Hélène Clair

5 Sorbonne University, UPMC Paris 06 University, INSERM, CNRS, Institut du Cerveau et de la Moelle Épinière, Paris, France

Julien F. Bally

6 Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Service of Neurology, Lausanne University Hospital and University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

Françoise Riquier

7 Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Service of Neurosurgery, Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), University of Lausanne (UNIL), Lausanne, Switzerland

Jocelyne Bloch

Bogdan draganski.

8 Laboratory for Research in Neuroimaging (LREN), Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Centre for Research in Neurosciences, Lausanne University Hospital, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

9 Department of Neurology, Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences, Leipzig, Germany

Marie-Thérèse Clerc

Beatriz pozuelo moyano, armin von gunten.

10 Univ Paris-Est Créteil, DMU IMPACT, Département Médical-Universitaire de Psychiatrie et d’Addictologie, Hôpitaux Universitaires Henri Mondor - Albert Chenevier, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Créteil, France

11 Sorbonne Université, Institut du Cerveau - Paris Brain Institute - ICM, Inserm, CNRS, Paris, France

Even though obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) is one of the ten most disabling diseases according to the WHO, only 30–40% of patients suffering from OCD seek specialized treatment. The currently available psychotherapeutic and pharmacological approaches, when properly applied, prove ineffective in about 10% of cases. The use of neuromodulation techniques, especially Deep Brain Stimulation, is highly promising for these clinical pictures and knowledge in this domain is constantly evolving. The aim of this paper is to provide a summary of the current knowledge about OCD treatment, while also discussing the more recent proposals for defining resistance.

1. Introduction

According to the DSM-5, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is characterized by the presence of obsessions and/or compulsions. Obsessions are recurrent and persistent thoughts, urges, or images that are experienced as intrusive and unwanted, whereas compulsions are repetitive behaviors or mental acts that an individual feels driven to perform in response to an obsession or according to rules that must be applied rigidly ( 1 ).

The WHO listed OCD within the ten medical illnesses associated with greatest worldwide disability ( 2 ), its estimated prevalence in the United States is 2.3% for lifetime OCD and 1.2% for 12 months criteria ( 3 ), while the lifetime prevalence of OCD in the general population, according to a study that considered six European countries, is estimated to be in the range of 1–2% ( 4 ). Despite the major impact of this condition on quality of life, it has been reported that only a small proportion of OCD sufferers seek psychiatric treatment, ranging from 30 to 40% ( 5 ).

Patient reluctance to consult a professional, together with the fact that OCD rarely results in situations requiring compulsory hospitalization, probably accounts for psychiatrists’ lack of opportunity to recognize and treat this condition, as found in several surveys ( 6 , 7 ).

These critical issues constitute a potential risk that many patients do not access adequate treatment and will be misdiagnosed as resistant when several available treatment steps have not been offered.

The aim of this paper is to provide a summary of the current knowledge about OCD treatment, while also discussing the more recent proposals for defining resistance.

2. First-line treatment

2.1. psychotherapy.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) with exposure and response prevention (E/RP) is one of the first-line evidence-based treatments for OCD ( 8 , 9 ). Indeed, several meta-analyses have found a significant reduction of OCD symptoms after a psychotherapy including E/RP ( 10 – 13 ), with 42–52% of patients achieving symptom remission ( 12 ). Moreover, CBT has been found to be more efficient than serotoninergic treatment, including Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs), by several studies ( 12 , 14 , 15 ). More recently, a review indicated a number needed to treat (NNT) of three for CBT and five for SSRIs ( 16 ), with the additional benefit of fewer side effects and relapses. However, those results should be interpreted considering potential biases, such as the exclusion from the CBT trials of patients with comorbidities or the most severe cases of OCD.

Furthermore, the limit of accessibility to CBT should be considered, SSRI remaining the most cost-effective treatments ( 17 ). Indeed, financial cost, difficulty attending sessions and fear regarding anxiety-provoking exercises are the main perceived barriers to initiate and complete CBT ( 18 ). In line with those results, a systematic meta-analysis indicated that more than 15% of eligible patients refuse CBT and about 16% dropped out, with lower dropout rates in group CBT ( 19 ), Internet based CBT ( 20 ) or other psychotherapy techniques combined with E/RP, such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) could partially overcome those limits.

Nevertheless, it is suggestive of the crucial importance of psychotherapy in the treatment algorithm, especially since acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) ( 21 ) or mindfulness ( 22 ), alone or combined with E/RP, showed promising perspectives in the treatment of OCD.

2.2. Pharmacotherapy: Serotoninergic agents

Along with CBT, SSRIs are considered a first-line treatment in OCD by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Practice Guidelines ( 8 ). There is multiple evidence regarding the connections between serotonergic disruption and OCD: a specific genetic polymorphism for the gene encoding the serotonin transporter 5-HTT (SLC6A4) has been found in significant association with OCD patients ( 23 , 24 ). An increased sensitivity of 5-HT2 receptors has also been hypothesized in OCD patients, since OCD patients show a more pronounced neuroendocrine response than healthy controls to stimulation with an agent with high affinity for 5-HT2 receptors ( 25 ). These neurophysiological findings may explain the low efficacy of antidepressants with primary norepinephrine action, such as desipramine, compared with molecules with a serotonergic action profile ( 26 ). However, there is no evidence to date of an unequivocal correlation between alterations in specific serotoninergic pathways and the clinical manifestation of symptoms. As noted in a recent comprehensive review of pharmacotherapeutic strategies, considerations of serotonergic disruption are based exclusively on empirical evidence, whereas studies on specific alterations of 5HT2A receptors have produced controversial results ( 27 ).

As such, SSRI monotherapy is suggested as an option for patients with insufficient compliance for psychotherapy. Clomipramine has been accounted for a greater efficacy in several meta-analyses ( 28 , 29 ), but single trials ( 30 , 31 ) comparing it head-to-head with SSRIs do not support this evidence. When SSRIs are used to treat OCD, they should be regarded as anti-obsessive agents rather than antidepressants, bearing in mind that both the dosage and the latency between the start of treatment and the response are different when compared to depression. For example, SSRI are more efficacious when used at higher doses than for depression ( 32 , 33 ). Also, a meta-analysis showed that the minimum time between SSRI initiation at effective dosage and its clinical impact is 10–12 weeks ( 32 ). However, this work, which reviews seventeen randomized clinical trials, introduces an element of complexity. The first statistically significant results of symptom reduction are observed after only 2 weeks of prescribing SSRIs, and the improvement follows a logarithmic curve whereby the greatest effects of treatment are observed in the early phase. Some meta-analyses even suggest longer waiting periods, showing a progressive improvement up to 28 weeks after the initiation of SSRI therapy ( 34 – 36 ).

However, the framework of action of serotonergic agents remains complex and not unambiguously definable in terms of both dosage and response delay. A meta-analysis focusing on the question of correlation between dosage and clinical response, conducted on nine randomized clinical trials, concluded that there was a 7–9% higher reduction in OCD symptoms in patients in the high-dose group, although all treatment groups (low-dose, medium-dose, and high-dose) showed a greater reduction in YBOCS score than placebo group ( 37 ). Although the benefit of these higher doses has been shown, it must be born in mind that the number needed to treat (NTT) of OCD patients on monotherapy with standard-dose SSRIs is five, whereas the NTT for obtaining a response by switching to a medium or high dose ranges from 13 to 15. This testifies to the limited possibility of obtaining a response in a non-responder with dose escalation ( 33 ). A further factor to be taken into account is the fact that off-label prescriptions produce a considerable lack of access for patients to adequate dose therapy. This phenomenon prolongs the duration of untreated illness (DUI), a parameter that appears to have a significant impact in terms of outcome for patients treated with SSRIs ( 38 ).

Table 1 indicates the maximum dosage for several SSRIs used as anti-obsessive agents ( 26 ), compared to the same molecules when used as antidepressant agents.

Comparison of maximum dosage of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) when used as antidepressants vs. anti-obsessive agents.

The use of high doses of serotonergic agents requires subsequent medical monitoring, in particular ECG monitoring (risk of QT prolongation), liver enzymes and electrolytes check at month 1, 2, 3, 6, and 12 after treatment initiation, then once a year in the absence of side effects. If necessary, drug plasma level controls and CYP450 genotyping may be useful in case of suspicion of rapid metabolizers. Particular attention must be paid when other drugs are prescribed for co-morbid conditions, to prevent serotoninergic syndrome (for instance monoamine oxidase B inhibitors).

The main psychiatric assessment tool in the follow-up of OCD therapy is the YBOCS. Data from the literature define a favorable response in terms of a reduction from the initial score of 25–35%, and there is not a generally accepted consensus in defining this threshold ( 39 ). The International Treatment Refractory OCD Consortium proposed stages for assessing the response to treatment. A reduction of 35% or greater of the YBOCS score and Clinical Global Impression (CGI) less or equal to two is considered a full response; a reduction between 25 and 35% is a partial response and a reduction inferior to 25% is a non-response ( 40 ). A retrospective study of 87 adult patients attempted to establish a correlation between the percentage reduction of YBOCS and CGI. The results show that setting a 30% or greater reduction in YBOCS has the highest efficiency of clinical predictivity, with a 91% chance of having a CGI corresponding to “improved” or “very much improved” ( 41 ).

3. Second-line treatment

Taking for granted the heterogeneity in the definition of response criteria in the literature, a recent review on pharmacotherapeutic strategies in OCD suggests that only up to 50% of patients respond to SSRIs ( 27 ). Despite research aimed at identifying the preferred molecule among SSRIs, no significant differences in terms of efficacy have been shown within this class ( 39 , 42 ). Switching from one SSRI to another seems to allow an improvement of 20% in the best cases. Alternative strategies are discussed separately in the following sections.

3.1. Clomipramine

Clomipramine is a tricyclic antidepressant. Its antidepressant properties are probably due to the inhibition of neuronal re-uptake of serotonin (5-HT) and noradrenaline released into the synaptic space. Clomipramine’s pharmacological spectrum includes noradrenergic, antihistaminic and serotonergic properties. Its role in the treatment of OCD has been established since the first controlled study in 1991 ( 43 ), and its effectiveness has been confirmed several times in subsequent studies ( 15 , 44 ). Despite rapidly gaining a reputation as the gold standard treatment for OCD, clomipramine showed to be non-superior to SSRIs in a recent meta-analysis including 53 articles ( 42 ). Its side-effect profile (including epilepsy, increased liver enzymes, xerostomia, increased heart rate, constipation) calls for caution when prescribing it.

Although clomipramine remains a possible second-line treatment according to the APA ( 8 ) and Canadian clinical practice guidelines ( 45 ), the most recent evidence suggests that switching from an SSRI to clomipramine is not mandatory, while preliminary data support its use as an add-on agent in cases of resistance. Further investigations in this regard remain necessary ( 42 ).

Venlafaxine is the most studied molecule in this class, having shown efficacy in numerous trials ( 45 – 47 ) at a dose of 150–375 mg/d, with a response rate of up to 60%. The interpretation of these data is limited by the heterogeneity of responder definition: 35% reduction in YBOCS ( 46 ); CGI less than or equal to two ( 48 ), CGI-I less than or equal to 2 and 25% reduction in YBOCS ( 48 ). However, the studies mentioned so far do not show a significant advantage over SSRIs. Its efficacy is probably comparable to that of clomipramine, with a side-effect profile that makes it preferable to the latter ( 46 ).

4. Add-on treatments

4.1. antidepressant combination.

Although supported by little evidence, the add-on of clomipramine in combination with SSRIs is considered by the APA Practice Guidelines ( 8 ). A 2008 trial, including 20 patients who had failed to respond to at least two trials with a SSRI and who were taking clomipramine at different doses, showed a significant response in 50% of the sample with citalopram as an add-on therapy after 1 month of treatment ( 49 ). Another work on 14 patients showed that the add-on of sertraline to clomipramine is preferable to a dose increase of clomipramine as monotherapy in case of resistance ( 50 ). A report on four cases also showed that the combination of clomipramine and fluoxetine can be effective even in cases where the individual molecules have not produced any benefit in patients ( 51 ).

4.2. Antidopaminergic agents

The role of antidopaminergic molecules in the treatment of OCD is suggested by the hypothesis of dopaminergic hyperactivation, with a disruption of the medial prefrontal cortex inhibitory circuit on the amygdala and a subsequent increased activation of anxiety ( 52 , 53 ). The role of anxiety in the activation of obsessive behavior has been conceptualized from a modeling of complex tasks defined as “structured event complexes” (SECs), with respect to which the orbitofrontal cortex is implicated in reward, the anterior cingulate cortex in error detection, the basal ganglia in influencing the activation threshold of motor and behavioral programmes, while the prefrontal cortex would play the role of storing memories of these SECs. The activation of SECs could be accompanied by anxiety that is progressively alleviated by the performance of tasks, while a deficit in this process may be responsible for many OCD symptoms and have anxiety as its trigger ( 54 ). The dopamine D4 (DRD4) variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) 7R allele polymorphism is significantly associated with OCD ( 55 ), and a worsening of obsessive symptoms has been observed in OCD patients taking dopaminergic agonist drugs ( 56 ). However, as with serotonin, the evidence is ambiguous. The link between dopaminergic dysfunction and Tourette’s syndrome, as well as for other tic disorders, is more solid, and may in part influence the conception of the pathophysiology of OCD, given the high comorbidity between these conditions.

According to the most recent trials and reviews, the most effective prescriptions are low doses of aripiprazole (1–5 mg/d) and risperidone (0.5–1 mg/d) ( 57 – 59 ). This evidence suggests a possible role for 5HT2A antagonism in the control of OCD symptoms. The addition of an antipsychotic to SSRIs is effective in about a third of patients, especially in the presence of tics, with a number needed to treat of about five ( 33 , 34 ). A recent meta-analysis including all double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials comparing augmentation of SSRIs with antipsychotics to placebo supplementation in treatment-resistant OCD revealed a clear superiority of haloperidol, aripiprazole and risperidone over placebo, while quetiapine, paliperidone and olanzapine showed no evidence of superiority. Response was defined by a reduction of at least 35% of the YBOCS score. The overall rate of attrition in the group treated with antipsychotics as add-ons ranged from 10 to 25%, attributable in part to adverse effects, the main ones reported being mouth dryness, headache, and increased appetite ( 36 ). Clozapine is not recommended, as there is sufficient evidence of its role in a possible worsening of OCD symptoms ( 60 ).

4.3. Glutamatergic agents

An increased concentration of glutamate, one of the neurotransmitters in the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical loop, has been detected in the CSF of OCD patients ( 61 , 62 ), and a specific association between OCD and polymorphisms in genes SAPAP3 and SLC1A1, which code for proteins involved in glutamatergic transmission, has been found in several studies ( 63 – 65 ). The clinical data reported in the following section, however, only offers evidence regarding the use of glutamatergic agents as adjunctive therapies. The etiopathogenetic role of glutamatergic disruption therefore remains to be explored, to clarify whether it is a sufficient cause or rather an added element in the determination of a polyfactorial clinical picture.

The efficacy of memantine, a NMDA receptor antagonist which regulates the effects of pathologically elevated glutamate levels, in the treatment of OCD has been studied in a randomized trial of 42 patients treated with memantine versus placebo as an add-on to fluvoxamine for 8 weeks. At the end of the study, 89% of patients on memantine met the criteria for remission, defined as YBOCS score less than or equal to 16 compared with 32% in the placebo group ( 66 ). A recent meta-analysis confirmed that patients receiving memantine were 3.61 times more likely to respond to treatment than those receiving placebo, with a response threshold set at a 35% reduction in the YBOCS score. The average reduction was of 12 points on the YBOCS compared to the scores before the add-on for the treatment group. The most common memantine-related side effects were headache, drowsiness, confusion and dizziness, usually of moderate and transient magnitude. No statistically significant differences in terms of adverse events and dropouts were reported comparing the memantine-treated group and the placebo group ( 67 ). Since a significant effect was observed in trials of memantine as add-on therapy after 12 weeks, this period is the minimum recommended for evaluating the appropriateness of this treatment strategy ( 68 ).

A recent trial compared amantadine, another glutamatergic agent, versus placebo as add-on therapy to fluvoxamine in a randomized sample of 100 patients for 12 weeks. At the end of the study, the amantadine-treated group had a significant reduction in YBOCS on the total score and on the subscale for obsessive symptoms. No significant differences were observed in the reduction of the subscale for compulsive symptoms. The two groups had no significant differences in adverse effects. The considerations made so far, in the light of this evidence, suggest a potential role for amantadine in the treatment algorithm for OCD ( 69 ).

Ketamine is a NMDA receptor antagonist as well as a non-selective agent targeting the opioid, cholinergic and monoamine systems, all of which may contribute to its efficacy in OCD ( 69 – 71 ). It is used in off-label clinical practice as an augmentation strategy when the better-proven approaches have failed ( 71 – 73 ). Most trials indicate a rapid but short-lasting effect (days to weeks), with responses varying from full remission to no benefit ( 74 , 75 ).

Lamotrigine is an antiepileptic drug used in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. In view of its inhibitory action on AMPA glutamatergic receptors, its possible role as an adjunctive therapy in OCD has been investigated in a few studies and case reports ( 75 – 78 ) all indicating that lamotrigine may be an effective and safe therapeutic option as an add-on to SSRI treatment.

Topiramate, another AMPA antagonist, showed controversial results as both improvements ( 79 ) and worsening ( 80 ) of symptoms were observed.

5. OCD resistant vs. OCD refractory

A patient meets the criteria for OCD resistant when he or she has a reduction inferior to 25% at the YBOCS despite a trial of at least 12 weeks at the highest tolerated dose of SSRIs or clomipramine, in combination with at least 30 h of CBT. Refractory OCD is defined as a non-response after 3–6 months of at least three antidepressants (including clomipramine), and at least two add-on trial with atypical antipsychotics ( 81 ). However, these operational definitions are not unequivocal in the literature, and there are those who reserve the category of refractory for those patients who show no benefit or even worsen with the proposed treatment ( 82 ). Even in cases where adequate treatment is offered to the patient, a 10% persistence of severe disability due to OCD can be observed ( 83 ). For these patients, one therapeutic option may be the addition of glutamatergic agents, according to the potential and limitations just described. As an additional criterion for the transition to interventional therapy, the use of another CBT trial with a second independent therapist is indicated as a consensual criterion. Regarding interventional psychiatry, the strongest evidence is currently available for the use of DBS, while preliminary data encourage the investigation of other alternatives.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a neuromodulation technique whose application in OCD is based on a well-documented efficacy ( 84 ). A systematic review showed that, with regard to the target, there were no significant differences between the anterior limb of the internal capsule (ALIC) and the subthalamic nucleus (STN), and that up to 60% of operated patients had a reduction of at least 35% at YBOCS ( 85 ). The authors do not systematically report the inclusion criteria for all patients presented in the meta-analysis, but state that DBS is a last-line therapy. The most commonly accepted criteria for the indication of DBS in OCD patients are as follows: non-response (response being defined as at least 35% reduction in YBOCS) to two courses of SSRI treatment at the maximum dosage for at least 12 weeks; one course of clomipramine treatment at the maximum dose for at least 12 weeks; one add-on therapy with a second-generation antipsychotic for at least 8 weeks; one course of CBT, a Y-BOCS score of at least 28 points; a GAF score of less than 45 points; OCD duration of at least 5 years ( 79 ). This should be completed by the findings of a 2015 survey of 18 patients investigating the overall impact of DBS in quality of life ( 86 ). Both YBOCS responders and non-responders reported an improvement in their condition, while also reporting an improvement in their self-perception and emerging difficulties in the social sphere. These data are comparable with what has been learned about Parkinson’s patients who benefited from STN DBS ( 87 ). More recently, new targets have been proposed, such as ventral capsule/ventral striatum (VC/VS), nucleus accumbens (NAcc), anteromedial subthalamic nucleus (amSTN), or inferior thalamic peduncle (ITP) ( 84 ). The preliminary evidences of efficacy leaves open the prospect of an individual approach based on the identification of the different dimensions contributing to the heterogeneity of OCD ( 88 ). To date, the Congress of Neurological Surgeons considers the following evidence-based recommendations: the use of bilateral subthalamic nucleus DBS, combined with optimal pharmacotherapy, is recommended on a level I evidence basis. The use of bilateral nucleus accumbens or bed nucleus of stria terminalis for refractory pathology is on a type II level of evidence. These indications are the result of a systematic review conducted by the Guidelines Task Force in 2020, considering an updated literature up to 2019 ( 89 ).

Although DBS may be a viable treatment option to consider in resistant OCD, a recent Swedish survey revealed that only 29% of OCD patients are aware of its existence, that all psychotherapists surveyed estimate that their patients do not meet the criteria for an intervention, and that although psychiatrists believe 98% of the time that they have patients potentially eligible for DBS, they doubt their ability to identify them ( 90 ).

Added to this is the difficulty of insurance coverage: in the US, only 50 per cent of potential DBS recipients receive treatment, and less than 40 per cent receive coverage from their insurance company ( 91 ).

A 2022 article on the DBS access crisis identifies the lack of insurance and lack of knowledge on the part of mental health professionals as the cause of this The authors point out that this is in contrast to the mental-health parity laws enacted in 2008 ( 92 ).

A recent review, which included 40 articles and covers the last 20 years of DBS practice in OCD patients, reports the main adverse effects associated with this therapy. These can be divided into three groups: adverse effects due to surgical or hardware-related complications, stimulation-induced side effects and other types of side effects which will be listed briefly below. Electrode malpositioning or intracranial infection (which affects between 1 and 15% of Parkinson’s DBS procedures overall) are the main causes of device removal and re-implantation. Intracranial bleeding is a serious side effect that can reach rates of between 4.8 and 7.7%. Epileptic seizures, regardless of the site of stimulation, have been occasionally described in the 5 years following surgery. These have malpositioning, cranial infections, unstable somatic pathologies and abrupt changes in parameters as risk factors. The most frequent stimulation-related side effect is hypomania, although this usually resolves after adjustment of the stimulation parameters. Other adverse effects related to stimulation include weight gain, sleep disturbances, subjective memory complaints and increased anxiety. The increased risk of suicide remains controversial as this could be attributable to previous pathology or disappointment at the lack of response to the device implantation ( 93 ).

5.2. Other interventional techniques

5.2.1. rtms.

A review of 2011 ( 94 ) reports 10 studies on repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) targeting dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and supplementary motor area (SMA), stating that it only demonstrated acute efficacy, with no significant difference with sham treatment. The most frequently reported adverse event in rTMS studies is headache, while there are anecdotal case reports on the occurrence of seizures and psychotic symptoms. In the meta-analysis under discussion, none of the side effects persisted for more than 4 weeks after the end of stimulation and no serious adverse events such as seizures and memory problems or cognitive problems occurred.

More recently, a multicenter study showed that bilateral low frequency rTMS targeting SMA significantly reduced obsessive symptoms compared to sham, with a sustained effect at 6 weeks follow-up ( 95 ). Another study showed the superiority of a 1 Hz stimulation of DLPFC over a similar 10 Hz stimulation and sham ( 96 ). Specific coils have received FDA approval for the treatment of OCD: H7 was cleared in 2018, based on evidence showing that its use in one study led to a 30% reduction in YBOCS in 38% of treated patients, compared to 11% in sham conditions ( 97 ). In 2020, the COOl D-B80 coil also received approval. According to the Clinical TMS society, the use of FDA-approved coils for OCD is recommended in case of resistance after two indicated therapies (two medications or one medication plus psychotherapy) that have been conducted for at least 8 weeks, or in case of drug intolerance after at least two trials. TMS is considered a viable alternative to relatively risky second- and third-line drug trials, such as antipsychotics, opioids, benzodiazepines and glutamatergic agents ( 98 ).

This evidence suggests that planning rTMS therapy before giving an indication for DBS is certainly desirable, considering the risks and benefits.

5.2.2. tDCS

A 2021 meta-analysis on the use of tDCS in psychiatric and neurological disorders found that a Pubmed search for the two keywords “tDCS” and “OCD” yielded a result of only eight entries. Due to the scarcity of trials, the authors exceptionally included Class IV studies in their analysis of this disorder, without excluding those involving a pediatric population ( 99 ). In this context, the authors make a recommendation of anodal pre-SMA tDCS as possibly effective in improving OCD (Level C). This is based on a class II trial ( 100 ) in which non-responders were enrolled in a subsequent open-label phase, achieving a noticeable improvement in symptom intensity despite not being able to be considered as responders. Further research is needed in this area, given these encouraging preliminary data on a technique characterized by safety and minimal invasiveness.

According to a review taking into account 567 tDCS sessions, the adverse events reported were moderate fatigue (35.3%), tingling (70.6%), slight itching at the electrode placement site (30.4%), headache (11.8%), nausea (2.9%), and insomnia (0.98%) ( 101 ). Despite its excellent safety profile, the data on the potential efficacy of tDCS in OCD do not currently justify systematically proposing this therapy in resistant or refractory cases.

6. Discussion

Less than 10% of OCD patients are currently receiving evidence-based therapy ( 10 ). The prospect of improving the offer for these patients, suffering from a highly debilitating condition lies in the adoption of common and scientifically validated practices on the one hand, and also in focusing research efforts in the directions offered by interventional psychiatry, and specifically DBS.

The scrupulous adoption of diagnostic and assessment criteria, followed by the adoption of treatment guidelines, allows reliable identification of resistant cases, which are potential beneficiaries of therapeutic approaches under research investigation. Given the impact of the disease on the patient’s quality of life, there is an increasing need to bring clinicians and researchers together to propose guidelines that integrate treatment options at the different stages of the algorithm. A graphic summary of the evidence discussed in this article is presented in Figure 1 . There is a need to propose the transfer of “experimental” paradigms to the clinic, without formally demanding a high level of evidence-basis in cases of resistance, but rather focusing on sufficient data to allow clinicians to make proposals according to the clinical presentation. Clinics and research are moving together in a direction of local groups developing empirical strategies supported by a reasonable foundation. It is important for this work to continue because it is from there that solid evidence will come to produce future guidelines, capable of integrating the most recent pharmacological and technical acquisitions.

A schematic summary of the various treatment steps according to the best evidence in the literature.

Author contributions

JD, JE, A-HC, JB, FR, JFB, BD, M-TC, BPM, AG, and LM contributed equally, either by writing entire paragraphs in their specific field of expertise, or by providing bibliographical references, and correcting and expanding information in order to offer the reader the best state-of-the-art in the article’s field of investigation. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Featured Clinical Reviews

- Screening for Atrial Fibrillation: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement JAMA Recommendation Statement January 25, 2022

- Evaluating the Patient With a Pulmonary Nodule: A Review JAMA Review January 18, 2022

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder : Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment

- 1 Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco

- 2 Department of Psychiatry and Yale Child Study Center, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut

- 3 Department of Psychiatry and University of Florida Genetics Institute, Gainesville

- Comment & Response Deep Brain Stimulation for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Sina Kohl, PhD; Jens Kuhn, MD JAMA

- Comment & Response Deep Brain Stimulation for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder—Reply Matthew E. Hirschtritt, MD, MPH; Michael H. Bloch, MD, MS; Carol A. Mathews, MD JAMA

Question What advances in screening, diagnosis, and management of adult obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) have been introduced in the past 5 years?

Findings In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition , OCD is now defined separately from anxiety disorders and there is an increased emphasis on the role of or relationships to comorbid tics, hoarding, and poor insight. There is growing support for novel dissemination methods for behavioral interventions (eg, online-based therapy), pharmacologic approaches (eg, neuroleptic augmentation of antidepressants), and neuromodulation (eg, deep-brain stimulation).

Meaning More accurate screening, precise diagnosis and formulation, and empirically supported treatments may lead to improved prognosis for adults with OCD.

Importance Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a neuropsychiatric disorder associated with significant impairment and a lifetime prevalence of 1% to 3%; however, it is often missed in primary care settings and frequently undertreated.

Objective To review the most current data regarding screening, diagnosis, and treatment options for OCD.

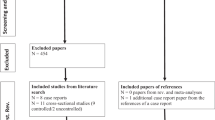

Evidence Review We searched PubMed, EMBASE, and PsycINFO to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs), meta-analyses, and systematic reviews that addressed screening and diagnostic and treatment approaches for OCD among adults (≥18 years), published between January 1, 2011, and September 30, 2016. We subsequently searched references of retrieved articles for additional reports. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews were prioritized; case series and reports were included only for interventions for which RCTs were not available.

Findings Among 792 unique articles identified, 27 (11 RCTs, 11 systematic reviews or meta-analyses, and 5 reviews/guidelines) were selected for this review. The diagnosis of OCD was revised for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition , which addresses OCD separately from anxiety disorders and contains specifiers to delineate the presence of tics and degree of insight. Treatment advances include increasing evidence to support the efficacy of online-based dissemination of cognitive behavioral therapies, which have demonstrated clinically significant decreases in OCD symptoms when conducted by trained therapists. Current evidence continues to support the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as first-line pharmacologic interventions for OCD; however, more recent data support the adjunctive use of neuroleptics, deep-brain stimulation, and neurosurgical ablation for treatment-resistant OCD. Preliminary data suggest safety of other agents (eg, riluzole, ketamine, memantine, N -acetylcysteine, lamotrigine, celecoxib, ondansetron) either in combination with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or as monotherapy in the treatment of OCD, although their efficacy has not yet been established.

Conclusions and Relevance The dissemination of computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy and improved evidence supporting it represent a major advancement in treatment of OCD. Although cognitive behavioral therapy with or without selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors remains a preferred initial treatment strategy, increasing evidence that supports the safety and efficacy of neuroleptics and neuromodulatory approaches in treatment-resistant cases provides alternatives for patients whose condition does not respond to first-line interventions.

Read More About

Hirschtritt ME , Bloch MH , Mathews CA. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder : Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment . JAMA. 2017;317(13):1358–1367. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.2200

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 01 August 2019

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

- Dan J. Stein 1 ,

- Daniel L. C. Costa 2 ,

- Christine Lochner 3 ,

- Euripedes C. Miguel 2 ,

- Y. C. Janardhan Reddy 4 ,

- Roseli G. Shavitt 2 ,

- Odile A. van den Heuvel 5 , 6 &

- H. Blair Simpson 7

Nature Reviews Disease Primers volume 5 , Article number: 52 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

311 Citations

207 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Obsessive compulsive disorder

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is a highly prevalent and chronic condition that is associated with substantial global disability. OCD is the key example of the ‘obsessive–compulsive and related disorders’, a group of conditions which are now classified together in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, and the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision, and which are often underdiagnosed and undertreated. In addition, OCD is an important example of a neuropsychiatric disorder in which rigorous research on phenomenology, psychobiology, pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy has contributed to better recognition, assessment and outcomes. Although OCD is a relatively homogenous disorder with similar symptom dimensions globally, individualized assessment of symptoms, the degree of insight, and the extent of comorbidity is needed. Several neurobiological mechanisms underlying OCD have been identified, including specific brain circuits that underpin OCD. In addition, laboratory models have demonstrated how cellular and molecular dysfunction underpins repetitive stereotyped behaviours, and the genetic architecture of OCD is increasingly understood. Effective treatments for OCD include serotonin reuptake inhibitors and cognitive–behavioural therapy, and neurosurgery for those with intractable symptoms. Integration of global mental health and translational neuroscience approaches could further advance knowledge on OCD and improve clinical outcomes.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 1 digital issues and online access to articles

92,52 € per year

only 92,52 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Toward a neurocircuit-based taxonomy to guide treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder

Elizabeth Shephard, Emily R. Stern, … Euripedes C. Miguel

A dimensional perspective on the genetics of obsessive-compulsive disorder

Nora I. Strom, Takahiro Soda, … Lea K. Davis

Autoantibodies in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review

Dominik Denzel, Kimon Runge, … Dominique Endres

Robbins, T. W., Vaghi, M. M. & Banca, P. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: puzzles and prospects. Neuron 102 , 27–47 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Mataix-Cols, D., do Rosario-Campos, M. C. & Leckman, J. F. A. Multidimensional model of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 162 , 228–238 (2005).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bloch, M. H., Landeros-Weisenberger, A., Rosario, M. C., Pittenger, C. & Leckman, J. F. Meta-analysis of the symptom structure of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 165 , 1532–1542 (2008).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Taylor, S. et al. Musical obsessions: a comprehensive review of neglected clinical phenomena. J. Anxiety Disord. 28 , 580–589 (2014).

Stein, D. J., Hollander, E. & Josephson, S. C. Serotonin reuptake blockers for the treatment of obsessional jealousy. J. Clin. Psychiatry 55, 30–33 (1994).

Greenberg, D. & Huppert, J. D. Scrupulosity: a unique subtype of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 12 , 282–289 (2010).

Phillips, K. A. et al. Should an obsessive-compulsive spectrum grouping of disorders be included in DSM-V? Depress. Anxiety 27 , 528–555 (2010). This review provides the rationale for the DSM-5 decision to include a new chapter on OCRDs .

Stein, D. J. et al. The classification of obsessive–compulsive and related disorders in the ICD-11. J. Affect. Disord. 190 , 663–674 (2016).

Bienvenu, O. J. et al. The relationship of obsessive–compulsive disorder to possible spectrum disorders: results from a family study. Biol. Psychiatry 48 , 287–293 (2000).

Monzani, B., Rijsdijk, F., Harris, J. & Mataix-Cols, D. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for dimensional representations of DSM-5 obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 71 , 182–189 (2014).

Karno, M. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in five US communities. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 45 , 1094 (1988).

Baxter, A. J., Vos, T., Scott, K. M., Ferrari, A. J. & Whiteford, H. A. The global burden of anxiety disorders in 2010. Psychol. Med. 44 , 2363–2374 (2014). This systematic review provides the foundation for estimations of the global burden of anxiety and related disorders .

Fontenelle, L. F., Mendlowicz, M. V. & Versiani, M. The descriptive epidemiology of obsessive–compulsive disorder. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 30 , 327–337 (2006).

Ruscio, A. M., Stein, D. J., Chiu, W. T. & Kessler, R. C. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol. Psychiatry 15 , 53–63 (2008). This community survey provides data on the prevalence and comorbidity of OCD in the general population .

Fontenelle, L. F. & Hasler, G. The analytical epidemiology of obsessive–compulsive disorder: risk factors and correlates. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 32 , 1–15 (2008).

Russell, E. J., Fawcett, J. M. & Mazmanian, D. Risk of obsessive-compulsive disorder in pregnant and postpartum women. J. Clin. Psychiatry 74 , 377–385 (2013).

Sharma, E., Thennarasu, K. & Reddy, Y. C. J. Long-term outcome of obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults. J. Clin. Psychiatry 75 , 1019–1027 (2014).

Lewis-Fernández, R. et al. Culture and the anxiety disorders: recommendations for DSM-V. Depress. Anxiety 27 , 212–229 (2010).

Isomura, K. et al. Metabolic and cardiovascular complications in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a total population, sibling comparison study with long-term follow-up. Biol. Psychiatry 84 , 324–331 (2018).

Meier, S. M. et al. Mortality among persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder in Denmark. JAMA Psychiatry 73 , 268–274 (2016).

Nelson, E. & Rice, J. Stability of diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Am. J. Psychiatry 154 , 826–831 (1997).

Weissman, M. M. et al. The cross national epidemiology of obsessive compulsive disorder. The Cross National Collaborative Group. J. Clin. Psychiatry 55 , 5–10 (1994).

PubMed Google Scholar

Stein, D. J., Scott, K. M., de Jonge, P. & Kessler, R. C. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders: from surveys to nosology and back. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 19 , 127–136 (2017).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Taylor, S. Etiology of obsessions and compulsions: a meta-analysis and narrative review of twin studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31 , 1361–1372 (2011).

Leckman, J. F. et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: a review of the diagnostic criteria and possible subtypes and dimensional specifiers for DSM-V. Depress. Anxiety 27 , 507–527 (2010).

Taylor, S. Molecular genetics of obsessive–compulsive disorder: a comprehensive meta-analysis of genetic association studies. Mol. Psychiatry 18 , 799–805 (2012).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Taylor, S. Disorder-specific genetic factors in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 171 , 325–332 (2015).

Article CAS Google Scholar

International Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Foundation Genetics Collaborative (IOCDF-GC) & OCD Collaborative Genetics Association Studies (OCGAS). Revealing the complex genetic architecture of obsessive–compulsive disorder using meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 23 , 1181–1188 (2017). This paper comprises the largest analysis of genome-wide association studies in OCD .

McGrath, L. M. et al. Copy number variation in obsessive-compulsive disorder and Tourette syndrome: a cross-disorder study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 53 , 910–919 (2014).

Brander, G., Pérez-Vigil, A., Larsson, H. & Mataix-Cols, D. Systematic review of environmental risk factors for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a proposed roadmap from association to causation. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 65 , 36–62 (2016).

Dykshoorn, K. L. Trauma-related obsessive–compulsive disorder: a review. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2 , 517–528 (2014).

Miller, M. L. & Brock, R. L. The effect of trauma on the severity of obsessive-compulsive spectrum symptoms: a meta-analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 47 , 29–44 (2017).

Mufford, M. S. et al. Neuroimaging genomics in psychiatry—a translational approach. Genome Med. 9 , 102 (2017).

Wolpe, J. The systematic desensitization treatment of neuroses. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 132 , 189–203 (1961).

Rachman, S., Hodgson, R. & Marks, I. M. The treatment of chronic obsessive-compulsive neurosis. Behav. Res. Ther. 9 , 237–247 (1971).

Rachman, S. Obsessional ruminations. Behav. Res. Ther. 9 , 229–235 (1971).

Salkovskis, P. M. Obsessional-compulsive problems: a cognitive-behavioural analysis. Behav. Res. Ther. 23 , 571–583 (1985).

Craske, M. G., Treanor, M., Conway, C. C., Zbozinek, T. & Vervliet, B. Maximizing exposure therapy: an inhibitory learning approach. Behav. Res. Ther. 58 , 10–23 (2014).

Jacoby, R. J. & Abramowitz, J. S. Inhibitory learning approaches to exposure therapy: a critical review and translation to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 49 , 28–40 (2016).

Obsessive Compulsive Cognitions Working Group. Cognitive assessment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 35 , 667–681 (1997).

Article Google Scholar

Stein, D. J., Goodman, W. K. & Rauch, S. L. The cognitive-affective neuroscience of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2 , 341–346 (2000).

Benzina, N., Mallet, L., Burguière, E., N’Diaye, K. & Pelissolo, A. Cognitive dysfunction in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 18 , 80 (2016).

Wood, J. & Ahmari, S. E. A. Framework for understanding the emerging role of corticolimbic-ventral striatal networks in OCD-associated repetitive behaviors. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 9 , 171 (2015).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Burguière, E., Monteiro, P., Mallet, L., Feng, G. & Graybiel, A. M. Striatal circuits, habits, and implications for obsessive–compulsive disorder. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 30 , 59–65 (2015).

Kalueff, A. V. et al. Neurobiology of rodent self-grooming and its value for translational neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 17 , 45–59 (2015).

Baxter, L. R. Caudate glucose metabolic rate changes with both drug and behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 49 , 681 (1992).

Kwon, J. S., Jang, J. H., Choi, J.-S. & Kang, D.-H. Neuroimaging in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Expert Rev. Neurother. 9 , 255–269 (2009).

van den Heuvel, O. A. et al. Brain circuitry of compulsivity. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 26 , 810–827 (2016).

van Velzen, L. S., Vriend, C., de Wit, S. J. & van den Heuvel, O. A. Response inhibition and interference control in obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8 , 419 (2014).

Rotge, J.-Y. et al. Provocation of obsessive-compulsive symptoms: a quantitative voxel-based meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 33 , 405–412 (2008).

Thorsen, A. L. et al. Emotional processing in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 25 functional neuroimaging studies. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 3 , 563–571 (2018).

Del Casale, A. et al. Executive functions in obsessive–compulsive disorder: an activation likelihood estimate meta-analysis of fMRI studies. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 17 , 378–393 (2015).

Eng, G. K., Sim, K. & Chen, S.-H. A. Meta-analytic investigations of structural grey matter, executive domain-related functional activations, and white matter diffusivity in obsessive compulsive disorder: an integrative review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 52 , 233–257 (2015).

Gillan, C. M., Robbins, T. W., Sahakian, B. J., van den Heuvel, O. A. & van Wingen, G. The role of habit in compulsivity. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 26 , 828–840 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rasgon, A. et al. Neural correlates of affective and non-affective cognition in obsessive compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis of functional imaging studies. Eur. Psychiatry 46 , 25–32 (2017).

Williams, L. M. Precision psychiatry: a neural circuit taxonomy for depression and anxiety. Lancet Psychiatry 3 , 472–480 (2016).

Sprooten, E. et al. Addressing reverse inference in psychiatric neuroimaging: meta-analyses of task-related brain activation in common mental disorders. Hum. Brain Mapp. 38 , 1846–1864 (2017).

Fineberg, N. A. et al. Mapping compulsivity in the DSM-5 obsessive compulsive and related disorders: cognitive domains, neural circuitry, and treatment. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 21 , 42–58 (2017).

Article PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Carlisi, C. O. et al. Shared and disorder-specific neurocomputational mechanisms of decision-making in autism spectrum disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Cereb. Cortex 27 , 5804–5816 (2017).

Norman, L. J. et al. Neural dysfunction during temporal discounting in paediatric attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 269 , 97–105 (2017).

Fan, S. et al. Trans-diagnostic comparison of response inhibition in Tourette’s disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 19 , 527–537 (2017).

Norman, L. J. et al. Structural and functional brain abnormalities in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 73 , 815 (2016).

Pujol, J. et al. Mapping structural brain alterations in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 61 , 720 (2004).

van den Heuvel, O. A. et al. The major symptom dimensions of obsessive-compulsive disorder are mediated by partially distinct neural systems. Brain 132 , 853–868 (2008).

Radua, J. & Mataix-Cols, D. Voxel-wise meta-analysis of grey matter changes in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry 195 , 393–402 (2009).

Radua, J., van den Heuvel, O. A., Surguladze, S. & Mataix-Cols, D. Meta-analytical comparison of voxel-based morphometry studies in obsessive-compulsive disorder versus other anxiety disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67 , 701–711 (2010).

de Wit, S. J. et al. Multicenter voxel-based morphometry mega-analysis of structural brain scans in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 171 , 340–349 (2014).

Fouche, J.-P. et al. Cortical thickness in obsessive–compulsive disorder: multisite mega-analysis of 780 brain scans from six centres. Br. J. Psychiatry 210 , 67–74 (2017).

Subirà, M. et al. Structural covariance of neostriatal and limbic regions in patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 41 , 115–123 (2016).

Thompson, P. M. et al. ENIGMA and the individual: predicting factors that affect the brain in 35 countries worldwide. NeuroImage 145 , 389–408 (2017).

Boedhoe, P. S. W. et al. Distinct subcortical volume alterations in pediatric and adult OCD: a worldwide meta- and mega-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 174 , 60–69 (2017).

Goodkind, M. et al. Identification of a common neurobiological substrate for mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry 72 , 305–315 (2015).

Boedhoe, P. S. W. et al. Cortical abnormalities associated with pediatric and adult obsessive-compulsive disorder: findings from the ENIGMA Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Working Group. Am. J. Psychiatry 175 , 453–462 (2018). Together with Boedhoe et al. (2017), this paper comprises the largest brain imaging study of OCD .

Radua, J. et al. Multimodal voxel-based meta-analysis of white matter abnormalities in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 39 , 1547–1557 (2014).

Jenkins, L. M. et al. Shared white matter alterations across emotional disorders: a voxel-based meta-analysis of fractional anisotropy. Neuroimage Clin. 12 , 1022–1034 (2016).

Bandelow, B. et al. Biological markers for anxiety disorders, OCD and PTSD: a consensus statement. Part II: neurochemistry, neurophysiology and neurocognition. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 18 , 162–214 (2016).

Kim, E. et al. Altered serotonin transporter binding potential in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder under escitalopram treatment: [ 11 C]DASB PET study. Psychol. Med. 46 , 357–366 (2015).

Nikolaus, S., Antke, C., Beu, M. & Müller, H.-W. Cortical GABA, striatal dopamine and midbrain serotonin as the key players in compulsive and anxiety disorders — results from in vivo imaging studies. Rev. Neurosci. 21 , 119–139 (2010).

Goodman, W. K. et al. Beyond the serotonin hypothesis: a role for dopamine in some forms of obsessive compulsive disorder? J. Clin. Psychiatry 51 , 36–43 (1990).

Olver, J. S. et al. Dopamine D1 receptor binding in the anterior cingulate cortex of patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 183 , 85–88 (2010).

Ducasse, D. et al. D2 and D3 dopamine receptor affinity predicts effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in obsessive-compulsive disorders: a metaregression analysis. Psychopharmacology 231 , 3765–3770 (2014).

Brennan, B. P., Rauch, S. L., Jensen, J. E. & Pope, H. G. A. Critical review of magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 73 , 24–31 (2013).

Bhattacharyya, S. et al. Anti-brain autoantibodies and altered excitatory neurotransmitters in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 34 , 2489–2496 (2009).

Stewart, S. E. et al. Meta-analysis of association between obsessive-compulsive disorder and the 3ʹ region of neuronal glutamate transporter gene SLC1A1 . Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 162 , 367–379 (2013).

Burguiere, E., Monteiro, P., Feng, G. & Graybiel, A. M. Optogenetic stimulation of lateral orbitofronto-striatal pathway suppresses compulsive behaviors. Science 340 , 1243–1246 (2013). This paper demonstrates the value of basic neuroscience research in shedding light on OCD .

Kariuki-Nyuthe, C., Gomez-Mancilla, B. & Stein, D. J. Obsessive compulsive disorder and the glutamatergic system. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 27 , 32–37 (2014).

Turna, J., Grosman Kaplan, K., Anglin, R. & Van Ameringen, M. “What’s bugging the gut in OCD?” A review of the gut microbiome in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Depress. Anxiety 33 , 171–178 (2015).

Renna, M. E., O’Toole, M. S., Spaeth, P. E., Lekander, M. & Mennin, D. S. The association between anxiety, traumatic stress, and obsessive-compulsive disorders and chronic inflammation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress. Anxiety 35 , 1081–1094 (2018).

Fineberg, N. A. et al. Probing compulsive and impulsive behaviors, from animal models to endophenotypes: a narrative review. Neuropsychopharmacology 35 , 591–604 (2009).

Mataix-Cols, D. et al. Symptom stability in adult obsessive-compulsive disorder: data from a naturalistic two-year follow-up study. Am. J. Psychiatry 159 , 263–268 (2002).

Lochner, C. et al. Gender in obsessive–compulsive disorder: clinical and genetic findings. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 14 , 105–113 (2004).

Torresan, R. C. et al. Symptom dimensions, clinical course and comorbidity in men and women with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 209 , 186–195 (2013).

Rapp, A. M., Bergman, R. L., Piacentini, J. & Mcguire, J. F. Evidence-based assessment of obsessive–compulsive disorder. J. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Dis. 8 , 13–29 (2016).

du Toit, P. L., van Kradenburg, J., Niehaus, D. & Stein, D. J. Comparison of obsessive-compulsive disorder patients with and without comorbid putative obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders using a structured clinical interview. Compr. Psychiatry 42 , 291–300 (2001).

Goodman, W. K. et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 46 , 1006–1011 (1989). The Y-BOCS remains the gold standard measure for assessing symptom severity in OCD .

Rosario-Campos, M. C. et al. The Dimensional Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (DY-BOCS): an instrument for assessing obsessive–compulsive symptom dimensions. Mol. Psychiatry 11 , 495–504 (2006).