- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a serious mental disorder in which people interpret reality abnormally. Schizophrenia may result in some combination of hallucinations, delusions, and extremely disordered thinking and behavior that impairs daily functioning, and can be disabling.

People with schizophrenia require lifelong treatment. Early treatment may help get symptoms under control before serious complications develop and may help improve the long-term outlook.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Schizophrenia involves a range of problems with thinking (cognition), behavior and emotions. Signs and symptoms may vary, but usually involve delusions, hallucinations or disorganized speech, and reflect an impaired ability to function. Symptoms may include:

- Delusions. These are false beliefs that are not based in reality. For example, you think that you're being harmed or harassed; certain gestures or comments are directed at you; you have exceptional ability or fame; another person is in love with you; or a major catastrophe is about to occur. Delusions occur in most people with schizophrenia.

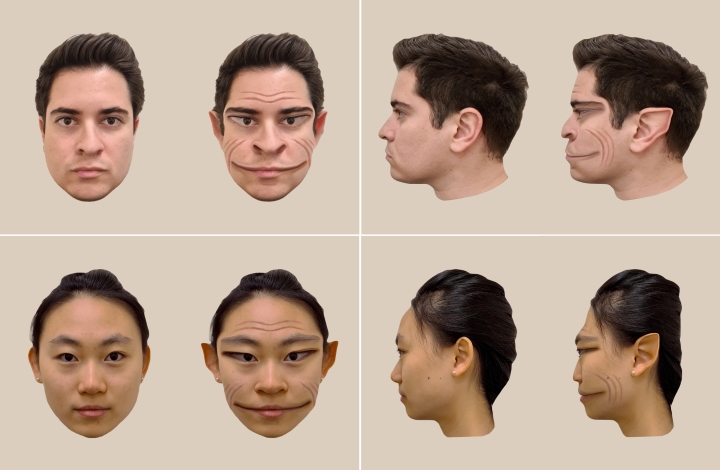

- Hallucinations. These usually involve seeing or hearing things that don't exist. Yet for the person with schizophrenia, they have the full force and impact of a normal experience. Hallucinations can be in any of the senses, but hearing voices is the most common hallucination.

- Disorganized thinking (speech). Disorganized thinking is inferred from disorganized speech. Effective communication can be impaired, and answers to questions may be partially or completely unrelated. Rarely, speech may include putting together meaningless words that can't be understood, sometimes known as word salad.

- Extremely disorganized or abnormal motor behavior. This may show in a number of ways, from childlike silliness to unpredictable agitation. Behavior isn't focused on a goal, so it's hard to do tasks. Behavior can include resistance to instructions, inappropriate or bizarre posture, a complete lack of response, or useless and excessive movement.

- Negative symptoms. This refers to reduced or lack of ability to function normally. For example, the person may neglect personal hygiene or appear to lack emotion (doesn't make eye contact, doesn't change facial expressions or speaks in a monotone). Also, the person may lose interest in everyday activities, socially withdraw or lack the ability to experience pleasure.

Symptoms can vary in type and severity over time, with periods of worsening and remission of symptoms. Some symptoms may always be present.

In men, schizophrenia symptoms typically start in the early to mid-20s. In women, symptoms typically begin in the late 20s. It's uncommon for children to be diagnosed with schizophrenia and rare for those older than age 45.

Symptoms in teenagers

Schizophrenia symptoms in teenagers are similar to those in adults, but the condition may be more difficult to recognize. This may be in part because some of the early symptoms of schizophrenia in teenagers are common for typical development during teen years, such as:

- Withdrawal from friends and family

- A drop in performance at school

- Trouble sleeping

- Irritability or depressed mood

- Lack of motivation

Also, recreational substance use, such as marijuana, methamphetamines or LSD, can sometimes cause similar signs and symptoms.

Compared with schizophrenia symptoms in adults, teens may be:

- Less likely to have delusions

- More likely to have visual hallucinations

When to see a doctor

People with schizophrenia often lack awareness that their difficulties stem from a mental disorder that requires medical attention. So it often falls to family or friends to get them help.

Helping someone who may have schizophrenia

If you think someone you know may have symptoms of schizophrenia, talk to him or her about your concerns. Although you can't force someone to seek professional help, you can offer encouragement and support and help your loved one find a qualified doctor or mental health professional.

If your loved one poses a danger to self or others or can't provide his or her own food, clothing, or shelter, you may need to call 911 or other emergency responders for help so that your loved one can be evaluated by a mental health professional.

In some cases, emergency hospitalization may be needed. Laws on involuntary commitment for mental health treatment vary by state. You can contact community mental health agencies or police departments in your area for details.

Suicidal thoughts and behavior

Suicidal thoughts and behavior are common among people with schizophrenia. If you have a loved one who is in danger of attempting suicide or has made a suicide attempt, make sure someone stays with that person. Call 911 or your local emergency number immediately. Or, if you think you can do so safely, take the person to the nearest hospital emergency room.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

It's not known what causes schizophrenia, but researchers believe that a combination of genetics, brain chemistry and environment contributes to development of the disorder.

Problems with certain naturally occurring brain chemicals, including neurotransmitters called dopamine and glutamate, may contribute to schizophrenia. Neuroimaging studies show differences in the brain structure and central nervous system of people with schizophrenia. While researchers aren't certain about the significance of these changes, they indicate that schizophrenia is a brain disease.

Risk factors

Although the precise cause of schizophrenia isn't known, certain factors seem to increase the risk of developing or triggering schizophrenia, including:

- Having a family history of schizophrenia

- Some pregnancy and birth complications, such as malnutrition or exposure to toxins or viruses that may impact brain development

- Taking mind-altering (psychoactive or psychotropic) drugs during teen years and young adulthood

Complications

Left untreated, schizophrenia can result in severe problems that affect every area of life. Complications that schizophrenia may cause or be associated with include:

- Suicide, suicide attempts and thoughts of suicide

- Anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Abuse of alcohol or other drugs, including nicotine

- Inability to work or attend school

- Financial problems and homelessness

- Social isolation

- Health and medical problems

- Being victimized

- Aggressive behavior, although it's uncommon

There's no sure way to prevent schizophrenia, but sticking with the treatment plan can help prevent relapses or worsening of symptoms. In addition, researchers hope that learning more about risk factors for schizophrenia may lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment.

- Schizophrenia. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. https://dsm.psychiatryonline.org. Accessed Sept. 5, 2019.

- AskMayoExpert. Schizophrenia (adult). Mayo Clinic; 2018.

- Valton V, et al. Comprehensive review: Computational modeling of schizophrenia. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2017; doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.08.022.

- Fisher DJ, et al. The neurophysiology of schizophrenia: Current update and future directions. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2019; doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2019.08.005.

- Schizophrenia. National Institute of Mental Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/schizophrenia/index.shtml. Accessed Sept. 5, 2019.

- Schizophrenia. National Alliance on Mental Illness. https://www.nami.org/learn-more/mental-health-conditions/schizophrenia. Accessed Sept. 5, 2019.

- What is schizophrenia? American Psychiatric Association. https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/schizophrenia/what-is-schizophrenia. Accessed Sept. 5, 2019.

- Schizophrenia. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/psychiatric-disorders/schizophrenia-and-related-disorders/schizophrenia. Accessed Sept. 5, 2019.

- How to cope when a loved one has a serious mental illness. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/helpcenter/serious-mental-illness. Accessed Sept. 5, 2019.

- Supporting a friend or family member with mental health problems. MentalHealth.gov. https://www.mentalhealth.gov/talk/friends-family-members. Accessed Sept. 5, 2019.

- For people with mental health problems. MentalHealth.gov. https://www.mentalhealth.gov/talk/people-mental-health-problems. Accessed Sept. 5, 2019.

- Roberts LW, ed. Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders. In: The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. 7th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019.

- Schak KM (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. Dec. 11, 2019.

- Leung, JG (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. Dec. 10, 2019.

Associated Procedures

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Let’s celebrate our doctors!

Join us in celebrating and honoring Mayo Clinic physicians on March 30th for National Doctor’s Day.

Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

This topic discusses clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and course of schizophrenia. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of schizophrenia in adults and children, and their treatment are discussed separately.

● (See "Psychosis in adults: Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnostic evaluation" .)

● (See "Schizophrenia in adults: Epidemiology and pathogenesis" .)

● (See "Depression in schizophrenia" .)

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- Winter 2024 | VOL. 22, NO. 1 Reproductive Psychiatry: Postpartum Depression is Only the Tip of the Iceberg CURRENT ISSUE pp.1-142

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Schizophrenia: An Overview

- Tahir Rahman , M.D. , and

- John Lauriello , M.D.

Search for more papers by this author

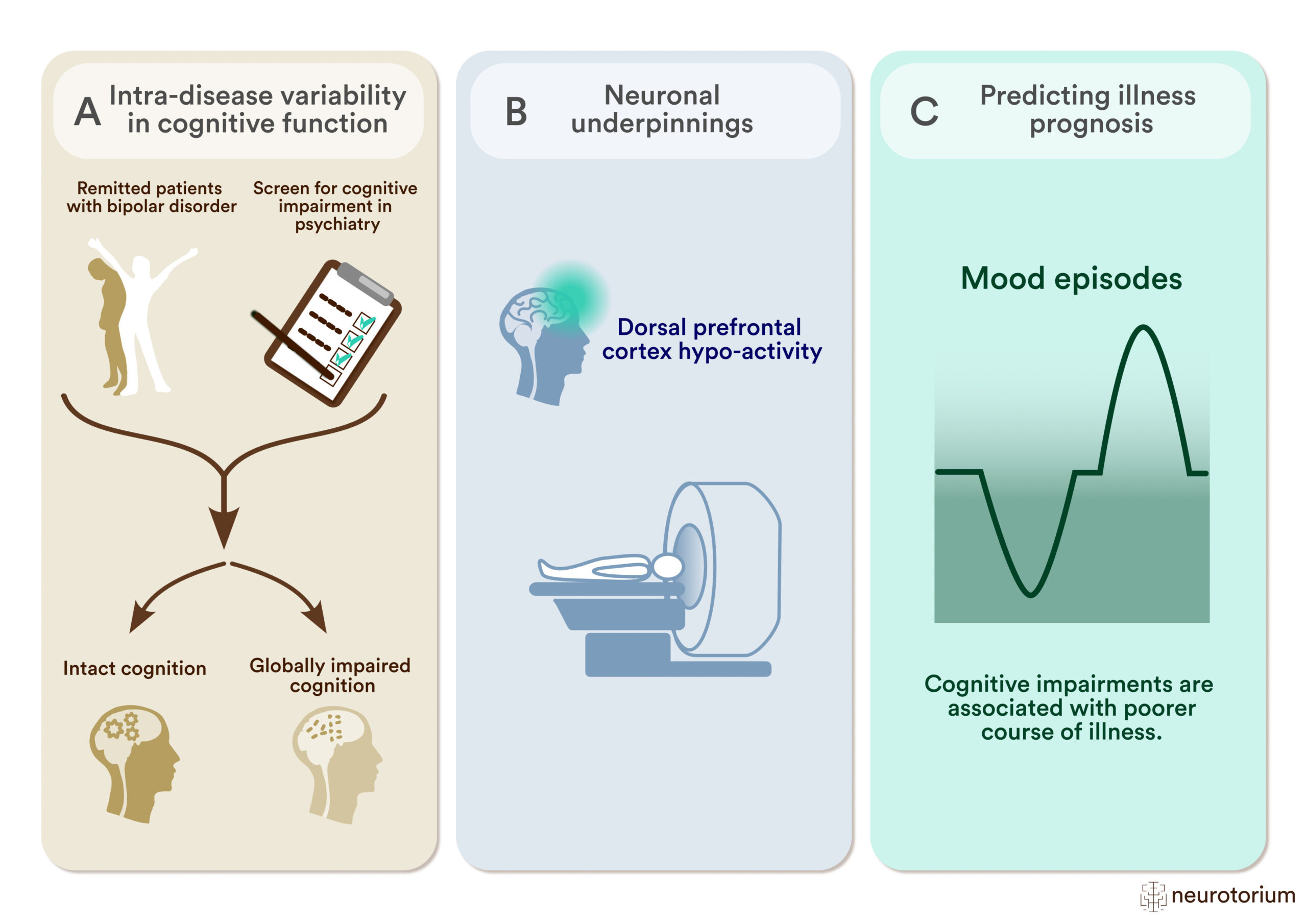

Few changes were made to the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia in DSM-5 . Schizophrenia is a chronic mental illness with positive symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech and behavior), negative symptoms, and cognitive impairment. Discoveries in genetics, neuroimaging, and immune function continue to advance understanding of the etiologies for this elusive disease. The authors reviewed the current literature to give an overview. The topics include historical foundations, epidemiology, suicide risk, genomewide association studies, twin studies, neuroimaging, ventricular size, complement component 4 mediated synapse elimination, major histocompatibility complex markers, and associations seen in obstetrical complications, nutritional issues, prodromal and attenuated states, cannabis use, childhood trauma, immigration, and traumatic brain injury. Also reviewed are expressed emotions of caregivers and recidivism, conditions comorbid with obsessive-compulsive disorder, mood disorders, substance use, and finally some legal and ethical issues. These important developments in elucidating the disease mechanism will likely allow for the development of future novel treatment strategies.

A homeless man arrives at the emergency room, reporting that his brother is a space alien who is trying to take over the world. The man claims to hear voices and feel the presence of aliens in his body that are controlling his thoughts and actions. Such bizarre presentations are often seen among psychotic patients diagnosed as having schizophrenia. Physicians beginning to practice psychiatry are often drawn to the field after seeing patients with dramatic psychotic symptoms and soon learn that the illness is quite complex. Schizophrenia is a chronic psychiatric illness characterized by positive symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, and grossly disorganized speech and behavior), negative symptoms (apathy, social isolation, and diminished affect), and cognitive impairment ( 1 ). Any combination of these symptoms can lead to marked disruption in behavior and significant negative effects on functioning and an increased risk for the development of many comorbid health problems, suicide risk, and substance use disorders. Despite advances in epidemiology, genetics, and neuroimaging, psychiatrists still rely on a comprehensive history, physical exam, and laboratory studies to diagnose schizophrenia. The exact etiologic factors remain elusive. It is by definition a diagnosis made after the exclusion of other possible conditions such as a mood disorder, substance abuse, or certain medical conditions. We begin by discussing historical foundations of this illness, and DSM-5 criteria, and we review the epidemiologic, genetic, and neuroanatomical markers seen in this disease.

Historical Foundations

In 1911, the Swiss psychiatrist Eugene Blueler chose the Greek roots “schizo” (split) and “phrene” (mind) to describe the disorganized thinking of people with schizophrenia. Arnold Pick had noted in 1891 both psychotic and cognitive deficits among those with this disorder and called it “dementia praecox.” More notably, Emil Kraepelin in 1893 differentiated the episodic nature of psychosis seen in manic-depression from dementia praecox ( 2 ). Kurt Schneider tried to distinguish various forms of psychotic symptoms that he thought had special value in distinguishing schizophrenia from psychosis resulting from other disorders. These are known as Schneider's “first-rank” symptoms. They include passivity experiences, such as bizarre delusions of being controlled by an external force, thought insertion or withdrawal, and thought broadcasting. He used the German term gedankenlautwerden to describe the auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia as voices that are heard aloud. These voices could comment on an individual’s thoughts or behavior. The individual could also hear third-person conversations with other hallucinated voices talking to each other ( 3 ). Blueler, Kraepelin, Schneider, and other pioneers of psychiatry based schizophrenia’s classification on the observation that many psychotic symptoms tend to occur together. Despite such elegant descriptions, extensive diagnostic evaluations and follow-up have shown that there are no specific psychotic symptoms that are pathognomonic for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia was also traditionally subclassified into disorganized, catatonic, paranoid, residual, or undifferentiated types. These subtypes have not been shown to be reliable or predictive of outcome of the disorder and were eliminated in DSM-5 ( 4 ). The box on this page highlights the DSM-5 criteria for schizophrenia. If the full criteria are met but the duration of illness is less than six months, the diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder should be diagnosed.

DSM-5 CRITERIA FOR SCHIZOPHRENIA a

For a significant portion of the time since the onset of the disturbance, level of functioning in one or more major areas, such as work, interpersonal relations, or self-care, is markedly below the level achieved prior to the onset (or when the onset is in childhood or adolescence, there is failure to achieve expected level of interpersonal, academic, or occupational functioning).

Continuous signs of the disturbance persist for at least 6 months. This 6-month period must include at least 1 month of symptoms (or less if successfully treated) that meet Criterion A (i.e., active-phase symptoms) and may include periods of prodromal or residual symptoms. During these prodromal or residual periods, the signs of the disturbance may be manifested by only negative symptoms or by two or more symptoms listed in Criterion A present in an attenuated form (e.g., odd beliefs, unusual perceptual experiences).

Schizoaffective disorder and depressive or bipolar disorder with psychotic features have been ruled out because either 1) no major depressive or manic episodes have occurred concurrently with the active-phase symptoms, or 2) if mood episodes have occurred during active-phase symptoms, they have been present for a minority of the total duration of the active and residual periods of the illness.

The disturbance is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication) or another medical condition.

If there is a history of autism spectrum disorder or a communication disorder of childhood onset, the additional diagnosis of schizophrenia is made only if prominent delusions or hallucinations, in addition to the other required symptoms of schizophrenia, are also present for at least 1 month (or less if successfully treated).

Specify if:

The following course specifiers are only to be used after a 1-year duration of the disorder and if they are not in contradiction to the diagnostic course criteria.

Specify current severity:

_________________

a Reprinted from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , 5th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Copyright © 2013, American Psychiatric Association. Used with permission.

Psychosis is generally defined as a break in reality testing either by abnormal sensory experiences, such as hallucinations, or by holding fixed false beliefs (delusions) that are not accepted by most people. Impairment is also commonly seen in thought and speech patterns. An individual with schizophrenia may develop disorganized speech that makes maintaining discourse during an interview difficult (formal thought disorder) ( 5 ). A few minor changes were made to the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia from DSM-IV to DSM-5 . Five cardinal symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior, and negative symptoms) are all still recognized in criterion A. However, two of the first three (delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized speech) are now required to make the diagnosis. The concept of bizarre hallucinations or commenting voices was given more credence in earlier diagnostic criteria, but the phenomena are no longer given special consideration (as Schneider believed they should) in DSM-5 ( 6 ).

Despite these changes in diagnostic criteria, it is imperative for clinicians to screen patients for the cardinal signs of psychosis and to clinically elicit the classical symptoms of the disorder. This often requires a careful mental status examination and the collection of external sources of information such as records and interviews of family members ( 1 , 7 ).

Epidemiology

The prevalence of schizophrenia is around 1% (0.3% to 0.7%) worldwide ( 1 , 8 ). The incidence is about 1.5 per 10,000 individuals. The male:female ratio is 1.4:1. The increased risk among men has been of interest to researchers. Some have suggested that this may result from higher drug use among men or a possible protective effect from contraceptive use among women ( 8 , 9 ). On the basis of a large genomewide association study, the genetic basis of schizophrenia is similar among males and females. Females are often diagnosed later than males, and males typically have a worse outcome ( 1 , 10 ). About 20% of patients with schizophrenia attempt suicide. There is a 5%−6% lifetime prevalence rate of completed suicide, making this a life-threatening disorder. However, most individuals with schizophrenia die of natural causes and have a mortality rate that is two to three times greater than the rest of the population. The disease often strikes patients in the prime of their young adult life. The adult incidence curve increases until it reaches its highest point in the mid-20s, then declines. A second, much smaller peak of increased incidence of schizophrenia is seen in the 40s, which is more common in females ( 1 , 11 ).

Individuals with schizophrenia are much more vulnerable to becoming homeless than are people with no mental illness. Some of the highest rates of schizophrenia are found in the chronically homeless population. A large public mental health system study found that 15% were homeless at the time of at least one service encounter in a one-year period. Male gender, African American ethnicity, presence of substance use disorder, and a lack of Medicaid insurance were associated with homelessness of patients diagnosed as having schizophrenia. Patients often develop a complex array of social, medical, psychiatric, and financial issues. High levels of general medical comorbidities are commonly found among patients with schizophrenia and add a tremendous burden to the health care needs and cost in this population. Earlier diagnosis and treatment may be of great importance to prevent a declining health and psychosocial course ( 10 , 12 , 13 ).

Genetic Studies

Schizophrenia is often thought to be a number of disorders sharing a similar presentation ( 1 , 14 ). This is because no specific gene or environmental factor explains the etiology for all of the affected individuals ( 15 ). Genetic research has not revealed a robust understanding of the etiology of schizophrenia. Instead, genomewide association studies (GWAS) have revealed only a few weak-effect associations, which account for only a small part of the genetic risk. A complex interplay of genes and environment is likely responsible for the similar presentations of schizophrenia. The total heritable risk for schizophrenia is 70%−80% ( 14 – 16 ). A large number of statistical analyses are needed to estimate the genetic and environmental aspects of variance. Estimates are sometimes obtained with large data sample sets from individuals with a close genetic relationship—such as twins and siblings—rather than from more distantly related individuals. It has been determined that the monozygotic twin concordance rate is 40%−50% and that the dizygotic twin concordance rate is 10%−15%. Offspring of the unaffected monozygotic twin are at increased risk of schizophrenia, and there is a high incidence of disease among adopted children whose biological mothers have a diagnosis of schizophrenia ( 15 ). The following are some genes that have been of interest to schizophrenia researchers: catechol O -methyltransferase (COMT), DAO/G30, DISC 1, DTNB 1, GABRB2, NRG 1, and ZNF804A. Rare deletions at 15q13 and 22q11 (DiGeorge syndrome) regions may also predispose individuals to schizophrenia ( 15 – 17 ). There is genetic support for the existence of common DNA variants (single nucleotide polymorphisms) that influence risk of both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, differing from Kraeplin’s model, which assumes that these are two very separate entities ( 17 ).

GWASs have a greater power to detect weak associations to common variants. In 2014, the largest molecular genetic study of schizophrenia ever conducted was published by the schizophrenia genetics consortium. In this landmark schizophrenia GWAS, 108 conservatively defined loci met genomewide significance ( 18 ). Associations found that were relevant to hypotheses of the etiology and treatment of schizophrenia included DRD2 (the target of antipsychotic drugs) and multiple genes (e.g., GRM3, GRIN2A, SRR, GRIA1) involved in glutamatergic neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity. Epidemiological studies have also long hinted at a role for immune dysregulation involving the MHC in schizophrenia; the findings also provided genetic support for this hypothesis.

Another large multisite study was recently conducted to characterize 12 neurophysiological and neurocognitive endophenotypic measures in schizophrenia. Several genes of potential interest were identified: HTR6 on chromosome 1p36 (emotion recognition), ZNF804A on 2q32 (sensorimotor dexterity), ATXN7 on 3p14 (the antisaccade task), DAT on 5p15 (prepulse inhibition), GRIN2B on 12p12 (face memory), and YWHAE on 17p13 (multivariate cognitive phenotype) ( 19 ). Many of the candidate genes are involved in neurotransmission, synaptic plasticity, and brain development. Genetic markers involving the MHC along chromosome 6 are of great interest ( 20 ). The complement activation cascade is normally integral to the immune system’s ability to eliminate pathogens. However, excessive complement, particularly component 4 mediated synapse elimination, may play a role in the development of schizophrenia. In the brain, microglia are phagocyte immune cells that express complement receptors. Inappropriate or intense synaptic pruning may be explained by this aberrant immunological function ( 21 , 22 ). Advanced paternal age has also been linked to schizophrenia, possibly implicating de novo mutations in paternal germ cells. One study found that the odds of schizophrenia occurring among offspring of fathers 45 years old or older were 2.8 times as great as among offspring of fathers ages 20–24 years ( 23 ). However, in a large meta-analysis, increased genetic risk from the mother was thought to explain the association between advanced paternal age and psychosis and argued against the de novo mutation hypothesis. Instead, assortative mating may contribute to the observed association between advanced paternal age and maternal schizophrenia ( 24 ).

Gestational, Nutritional, and Immune System Factors

A host of environmental factors are also implicated in the development of schizophrenia. These include maternal factors such as immigration, perinatal factors (infections, inflammation, obstetrical complications, maternal stress, and fetal hypoxia), and winter births ( 25 – 27 ). Evidence of vascular involvement, including enlarged retinal venule calibers, are possibly related to genes regulated by hypoxia, altered cerebral blood flow, and mitochondrial dysfunction ( 26 ). Higher winter birth rates may be associated with gestational infections such as influenza or vitamin D deficiency. Famines leading to malnutrition during neurodevelopment are also implicated in schizophrenia ( 26 , 27 ). Folate deficiency in particular has been identified as a risk factor for schizophrenia in epidemiologic and gene-association studies. Low serum folate levels are correlated with negative symptoms of patients with schizophrenia. Elevated concentrations of homocysteine in the third trimester of maternal serum was correlated with a twofold risk of schizophrenia for the offspring. The low functioning 677C>T (222Ala>Val) variant in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene is overrepresented among patients with schizophrenia. Misvariants in three other genes that regulate 1-carbon metabolism—folate hydrolase 1 (FOLH1), methionine synthase (MTR), and COMT—are correlated with negative, but not positive, symptoms in schizophrenia. On the basis of preliminary trials, folate plus vitamin B12 supplementation may improve negative symptoms of schizophrenia for such genetically susceptible individuals ( 28 ).

Cytokines are signaling molecules of the immune system that exert effects in the periphery and the brain. They are produced by both immune and nonimmune cells and exert their effects by binding specific cytokine receptors on a variety of target cells. There is evidence of an increased prevalence of aberrant cytokine levels among patients with schizophrenia. Infection may induce maternal immune activation, which subsequently leads to a cytokine-mediated inflammatory response in the fetus. The timing of the insult to the developing fetus may also play an important role. Associations between schizophrenia and second-trimester influenza, rubella, respiratory infection, polio, measles, and varicella-zoster have been implicated ( 29 ). Toxoplasma gondii (a protozoan) infection of pregnant women may cause congenital deafness, retinal damage, seizures, and mental retardation. In addition, serum antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii were also found to be a risk factor for the development of schizophrenia ( 30 ). The following are some cytokines and inflammatory pathways that have been studied and found to be potentially associated with schizophrenia: tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin 1 (IL-1), IL-6, and IL-8 ( 31 , 32 ). Aside from their effects on neurotransmission, particularly dopamine, antipsychotics may additionally have a balancing effect on immune responses, perhaps accounting for the delayed response seen in many cases ( 33 ). For instance, antipsychotic treatment has been found to modulate plasma levels of soluble IL-2 receptors and to reduce the plasma levels of IL-1β and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) ( 33 , 34 ). Anti-inflammatory effects of aspirin, N -acetylcysteine, and estrogens have also been found to be beneficial in treating schizophrenia ( 35 ). In a recent meta-analysis, some cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and transforming growth factor-β [TGF-β]) were hypothesized to be state markers for acute exacerbations, whereas others (IL-12, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and soluble IL-2 receptor) may be trait markers ( 36 ).

Brain Injury, Traumatic Events, Cannabis, and Immigration

Environmental insults, such as traumatic brain injury, childhood traumatic events, and cannabis use, are also implicated in schizophrenia ( 25 , 37 ). Compared with native-born populations, immigrant populations, particularly those that face discrimination, have a considerable risk of schizophrenia. However, the exact mechanism of the environmental contribution to this risk remains poorly understood ( 38 ). Traumatic histories are common among patients with schizophrenia, and childhood traumatic events are associated with the development of schizophrenia. Patients diagnosed as having comorbid schizophrenia and posttraumatic stress disorder have worse symptoms, higher rates of suicidal thoughts, and more frequent hospitalizations ( 39 ).

Neurotransmitters and Receptors

In 1975, Seeman et al. discovered that haloperidol bound to dopamine sites with higher potency than did other neurotransmitters. These sites were named antipsychotic/dopamine receptors (now called D2 receptors). The research team further delineated antipsychotics by a rank order of potencies that were directly related to the mean daily antipsychotic dose taken by patients. They found that a minimum occupancy (65%) of D2 receptors was needed for antipsychotic benefit ( 40 ). The “dopamine hypothesis” was thus born and has long been used to describe the underlying pathophysiology of schizophrenia. However, mounting research implicates the dysregulation of other pathways such as glutamatergic, opioid, GABA-ergic, serotonergic, cholinergic, and possibly other systems ( 41 ).

The N -methyl- d -aspartate (NMDA) receptor is a glutamatergic receptor that has been of great interest to schizophrenia researchers, particularly with regard to recently discovered receptor subunits. NMDA receptors may be involved in brain overactivity caused by withdrawal of sedatives such as alcohol, resulting in agitation and seizures. The NMDA antagonists phencyclidine and ketamine induce a psychosis among healthy individuals that can mimic schizophrenia ( 42 , 43 ). In addition, neuroimaging studies using magnetic resonance spectroscopy have linked GABA and NMDA receptors to abnormal brain connectivity of individuals with schizophrenia ( 44 ). Reduced NMDA receptor activity can lead to sensory deficits, generalized cognitive deficits, impaired learning and memory, thought disorder, negative symptoms, positive symptoms, gating deficits, executive dysfunction, and dopamine dysregulation ( 45 ). NMDA receptor sites have now been identified with sophisticated three-dimensional crystallographic studies. These subunits may help lead to new discoveries, because endogenous ligands or pharmacological substances are known to modulate NMDA receptor activity in a subunit selective fashion ( 46 ). GABA-ergic inhibitory function is also of great interest for novel drug development ( 47 ).

Neuroimaging

Expanding data in neuroimaging has found evidence that individuals with schizophrenia have enlarged ventricles and cortical tissue loss of about 5% of brain volume ( 48 ). Some affected structures include the hippocampus, superior temporal cortex, and the prefrontal cortex. Functional MRI studies have found evidence of hyperactivity in the hippocampus and the dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex, leading some researchers to believe that a loss of inhibitory neuron function may be responsible for some of the symptoms in schizophrenia. A combination of structural and functional imaging strategies is currently being investigated to look for patterns of brain connectivity, particularly around the time when clinically high-risk individuals transition into full-blown psychosis ( 49 ). Progressive brain changes over time have been associated with a poorer prognosis. Some studies also suggest that antipsychotic medications have a subtle but measurable influence on brain tissue loss over time ( 50 ).

Prodromal State and Synaptic Pruning

Approximately 80%−90% of patients with schizophrenia have a “prodrome” lasting up to one year, characterized by “attenuated” psychotic symptoms that appear to be on a continuum with softer forms of psychotic symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations. These symptoms may include unusual, odd, or overvalued beliefs, guardedness, or auditory hallucinations. Schizophrenia is thought to derive primarily from deficits in dendritic spines that arise during development, thus posing another challenge to researchers ( 51 ).

From embryonic development to about the age of two years, new neurons and synapses are formed rapidly. This results in far more neurons and synapses than are needed. Synaptic pruning is the process by which these extra synapses are eliminated, thereby increasing the efficiency of the neural network. The entire process continues up until approximately 10 years of age, by which time nearly 50% of the synapses present at two years of age have been eliminated. The pattern and timeline of pruning may differ in various regions of the brain ( 51 ). This process of “editing” of brain connections—in which excess material is discarded—is a mechanism that remains elusive. The cytokine and microglial mediated synaptic pruning and dendritic retraction provide a hypothesis for the disease mechanism seen in the brains of individuals with schizophrenia ( 52 ).

Illness Course

Adolescent or young adult patients often present with the prodrome of symptoms described above in which patients function below their baseline level prior to meeting the full criteria for schizophrenia. This time period is also sometimes referred to as an “at-risk mental state.” It can be challenging to differentiate this from a mood disorder, substance abuse, attentional disorders, or maladaptive personality features ( 25 , 53 ). There are also studies revealing overlaps between autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia. Childhood-onset schizophrenia is a rare subtype. Genomewide copy number variation studies have identified rare mutations that are strong risk factors for both autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia. Nevertheless, early intervention is considered vital in reducing adverse outcomes ( 25 , 54 ).

Expressed Emotions and Recidivism

Numerous studies have demonstrated that high levels of expressed emotions (EE) in families of patients with schizophrenia are associated with relapses. Researchers since the 1950s have found that EE is an important environmental stressor that can worsen psychopathology and can often contribute to recidivism. For example, families or caregivers may use a negative tone of voice to convey their feelings of hostility (anger, criticism, rejection, irritability, ignorance, etc.), which ultimately can lead to patient decompensation. Case management interventions such as psychoeducation, improved communication skills, and healthy coping strategies, along with medication adherence, can be effective strategies in reducing high EE and decreasing recidivism ( 55 , 56 ).

Prognostic Considerations

Because the disease is variable, schizophrenia researchers over the past several decades have been examining prognostic indicators. In general, prognostic outcomes are considered better for females and with higher premorbid levels of social adjustment (e.g., being married, higher education levels, occupational status), rapid as opposed to slow onset of psychotic symptoms, positive as opposed to negative symptoms, and having a family environment with low EE scores. Indicators for higher risk of relapse are a genetic history of schizophrenia, a baseline schizoid personality disorder, earlier age of onset, higher levels of negative symptoms, and longer inpatient treatment ( 57 ). Religious, spiritual, artistic, and cultural issues are often pertinent to explore in interactions with patients, and psychiatrists and other clinicians should make efforts to use a person-centered approach during rapport building and treatment. However, aggressively challenging delusions is not generally effective and may agitate or create mistrust among patients with psychosis ( 58 ). Occasionally, patients can incorporate caregivers into their delusional system and thus pose a serious challenge to treatment.

Patients with schizophrenia have a lower overall life expectancy in comparison with that of the general population. This is likely due to a lack of overall quality of health and behavioral issues such as high blood pressure, diabetes, cancer, poor diet, lack of exercise, and cardiopulmonary diseases. Half of all patients with schizophrenia smoke cigarettes, a major contributor to comorbid health problems ( 59 ).

Comorbidity Issues

Teasing apart schizophrenia symptoms from those of other comorbid disorders can be difficult. Multiple studies worldwide have found that depression, anxiety, and substance abuse are found more often among patients with schizophrenia than in the general population ( 60 , 61 ). It is difficult to know whether these problems are part of the syndrome of schizophrenia or a result of having the illness. For example, if a young patient is also abusing substances, a first episode of psychosis can present a challenging clinical problem. One study suggested that 44% of such patients turned out to have had a drug-induced psychosis and that 56% of patients later developed schizophrenia as their primary diagnosis ( 61 , 62 ). Adolescents with a polymorphism (Val 158 Met) of the COMT gene may be especially vulnerable to developing schizophrenia after cannabis abuse ( 62 ).

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) also has been found at an increased rate (up to 12.5-fold) in schizophrenia. Conversely, there is a 3.77-fold increased risk of schizophrenia among patients with OCD. For some patients, depression and OCD are part of a prodrome for schizophrenia ( 61 , 63 ).

Legal and Ethical Issues

Contrary to popular belief, the proportion of violent crimes committed by people diagnosed with a severe mental illness is small. Despite portrayals in mass media, strangers are at a lower risk of being violently attacked by someone who has a severe mental disorder than by someone who is mentally healthy ( 64 ). However, the presence of substance abuse, treatment nonadherence, and persecutory delusions are associated with a greater risk of violence. Family members and friends are at the highest risk of being victimized by a violent patient who has a severe mental illness ( 64 , 65 ). The presence of psychosis from a severe mental illness is a common basis for the insanity defense used in criminal law in most states and in the federal jurisdiction of the United States. Forensic psychiatrists often reconstruct the accused individual’s lifelong history to determine whether a severe mental illness such as schizophrenia or some other condition, including malingering (faking), is present ( 66 ).

Patients with schizophrenia may become severely disabled by their symptoms. Examples include an inability to care for themselves (e.g., maintaining proper sustenance, shelter, or medical care) or a risk of harming themselves or others. The legal system is often involved to advocate for treatment and is balanced against the patient’s individual freedom and autonomy. For example, a guardian or surrogate decision maker may be legally appointed to make financial or medical decisions on the patient’s behalf. It may also become necessary for patients to be held involuntarily (civilly committed) for a period in an inpatient treatment facility or residential care facility. Medications may be forced on patients in some jurisdictions, usually on the basis of imminent harm criteria such as risk of harm to self or others. The use of injectable medications may become useful in the treatment of nonadherent patients. Obtaining consent for treatment can be challenging with patients who lack insight into their illness. Information should be titrated gradually to ethically treat the patient while revealing important potential harmful side effect issues as the patient regains the capacity to understand them ( 66 – 68 ). Patients with severe mental illnesses, including schizophrenia, have long been the subject of oppression, imprisonment, and even genocide under the Nazi regime. It is therefore critically important for psychiatry to maintain proper ethical codes of conduct with respect to the research and treatment of its most vulnerable populations ( 69 ).

Conclusions

Schizophrenia is a complex and chronic disorder with profound effects on patients, families, and communities. There is no unifying single feature of schizophrenia; psychiatrists have long hypothesized that schizophrenia is a multifactorial disease (or diseases) of the brain, which has in common similar symptoms and effects on functioning. Important advances in genetics, immune function, neuroanatomical markers, and neurodevelopment have increased our understanding of the underlying pathophysiology associated with the illness. In the coming years, we hope that further elucidating the pharmacogenetics, immunological aspects, and neurodevelopmental aspects of schizophrenia will allow for the discovery of novel treatments targeted to individual patients, ideally very early in the course of the illness.

Dr. Lauriello reports that he has served as an advisory member for an educational project that received an unrestricted educational grant from Janssen and Alkermes Pharmaceutical companies, served on a speakers bureau for Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, and received grant or research funding for a clinical trial site supported by Otsuka through Florida Atlantic University. Dr. Rahman reports no financial relationships with commercial interests.

1 American Psychiatric Association : Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , 5th ed. Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Association, 2013 Crossref , Google Scholar

2 Andreasen NC, Carpenter WT Jr : Diagnosis and classification of schizophrenia . Schizophr Bull 1993 ; 19:199–214 Crossref , Google Scholar

3 Schneider K : Clinical Psychopathology (English translation by B A Hamilton) . New York, Grune & Stratton, 1959 Google Scholar

4 Tandon R, Gaebel W, Barch DM, et al. : Definition and description of schizophrenia in the DSM-5 . Schizophr Res 2013 ; 150:3–10 Crossref , Google Scholar

5 Andreasen NC : Thought, language, and communication disorders: I. Clinical assessment, definition of terms, and evaluation of their reliability . Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979 ; 36:1315–1321 Crossref , Google Scholar

6 Heckers S, Barch DM, Bustillo J, et al. : Structure of the psychotic disorders classification in DSM-5 . Schizophr Res 2013 ; 150:11–14 Crossref , Google Scholar

7 Keefe RS, Poe M, Walker TM, et al. : The Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale: an interview-based assessment and its relationship to cognition, real-world functioning, and functional capacity . Am J Psychiatry 2006 ; 163:426–432 Crossref , Google Scholar

8 Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke JD Jr, et al. : One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States: based on five Epidemiologic Catchment Area sites . Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988 ; 45:977–986 Crossref , Google Scholar

9 Aleman A, Kahn RS, Selten JP : Sex differences in the risk of schizophrenia: evidence from meta-analysis . Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003 ; 60:565–571 Crossref , Google Scholar

10 Clemmensen L, Vernal DL, Steinhausen HC : A systematic review of the long-term outcome of early onset schizophrenia . BMC Psychiatry 2012 ; 12:150 Crossref , Google Scholar

11 Popovic D, Benabarre A, Crespo JM, et al. : Risk factors for suicide in schizophrenia: systematic review and clinical recommendations . Acta Psychiatr Scand 2014 ; 130:418–426 Crossref , Google Scholar

12 Foster A, Gable J, Buckley J : Homelessness in schizophrenia . Psychiatr Clin North Am 2012 ; 35:717–734 Crossref , Google Scholar

13 Folsom DP, Hawthorne W, Lindamer L, et al. : Prevalence and risk factors for homelessness and utilization of mental health services among 10,340 patients with serious mental illness in a large public mental health system . Am J Psychiatry 2005 ; 162:370–376 Crossref , Google Scholar

14 Schizophrenia Psychiatric Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) Consortium : Genome-wide association study identifies five new schizophrenia loci . Nat Genet 2011 ; 43:969–976 Crossref , Google Scholar

15 Gejman PV, Sanders AR, Duan J : The role of genetics in the etiology of schizophrenia . Psychiatr Clin North Am 2010 ; 33:35–66 Crossref , Google Scholar

16 Farrell MS, Werge T, Sklar P, et al. : Evaluating historical candidate genes for schizophrenia . Mol Psychiatry 2015 ; 20:555–562 Crossref , Google Scholar

17 Pearlson GD : Etiologic, phenomenologic, and endophenotypic overlap of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder . Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2015 ; 11:251–281 Crossref , Google Scholar

18 Ripke S, Neale BM, Corvin A, et al. : Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci . Nature 2014 ; 511(7510):421 Crossref , Google Scholar

19 Greenwood TA, Swerdlow NR, Gur RE, et al. : Genome-wide linkage analyses of 12 endophenotypes for schizophrenia from the Consortium on the Genetics of Schizophrenia . Am J Psychiatry 2013 ; 170:521–532 Crossref , Google Scholar

20 Sinkus ML, Adams CE, Logel J, et al. : Expression of immune genes on chromosome 6p21.3-22.1 in schizophrenia . Brain Behav Immun 2013 ; 32:51–62 Crossref , Google Scholar

21 Sekar A, Bialas AR, de Rivera H, et al. : Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium : Schizophrenia risk from complex variation of complement component 4 . Nature 2016 ; 530:177–183 Crossref , Google Scholar

22 Whalley K : Psychiatric disorders: linking genetic risk to pruning . Nat Rev Neurosci 2016 ; 17:199 Crossref , Google Scholar

23 Jaffe AE, Eaton WW, Straub RE, et al. : Paternal age, de novo mutations and schizophrenia . Mol Psychiatry 2014 ; 19:274–275 Crossref , Google Scholar

24 Miller B, Erick M, Jouko M, et al. : Meta-analysis of paternal age and schizophrenia risk in male versus female offspring . Schizophr Bull 2011 ; 37:1039–1047. Crossref , Google Scholar

25 Laurens KR, Luo L, Matheson SL, et al. : Common or distinct pathways to psychosis? A systematic review of evidence from prospective studies for developmental risk factors and antecedents of the schizophrenia spectrum disorders and affective psychoses . BMC Psychiatry 2015 ; 15:205 Crossref , Google Scholar

26 Meier MH, Shalev I, Moffitt TE, et al. : Microvascular abnormality in schizophrenia as shown by retinal imaging . Am J Psychiatry 2013 ; 170:1451–1459 Crossref , Google Scholar

27 Hoek HW, Brown AS, Susser E : The Dutch famine and schizophrenia spectrum disorders . Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998 ; 33:373–379 Crossref , Google Scholar

28 Roffman JL, Lamberti JS, Achtyes E, et al. : Randomized multicenter investigation of folate plus vitamin B12 supplementation in schizophrenia . JAMA Psychiatry 2013 ; 70:481–489 Crossref , Google Scholar

29 Ashdown H, Dumont Y, Ng M, et al. : The role of cytokines in mediating effects of prenatal infection on the fetus: implications for schizophrenia . Mol Psychiatry 2006 ; 11:47–55 Crossref , Google Scholar

30 Torrey EF, Bartko JJ, Lun ZR, et al. : Antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis . Schizophr Bull 2007 ; 33:729–736 Crossref , Google Scholar

31 Pandey GN, Ren X, Rizavi HS, et al. : Proinflammatory cytokines and their membrane-bound receptors are altered in the lymphocytes of schizophrenia patients . Schizophr Res 2015 ; 164:193–198 Crossref , Google Scholar

32 Nielsen PR, Agerbo E, Skogstrand K, et al. : Neonatal levels of inflammatory markers and later risk of schizophrenia . Biol Psychiatry 2015 ; 77:548–555 Crossref , Google Scholar

33 Haring L, Koido K, Vasar V, et al. : Antipsychotic treatment reduces psychotic symptoms and markers of low-grade inflammation in first episode psychosis patients, but increases their body mass index . Schizophr Res 2015 ; 169:22–29 Crossref , Google Scholar

34 Tourjman V, Kouassi É, Koué MÈ, et al. : Antipsychotics’ effects on blood levels of cytokines in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis . Schizophr Res 2013 ; 151:43–47 Crossref , Google Scholar

35 Bumb JM, Enning F, Leweke FM : Drug repurposing and emerging adjunctive treatments for schizophrenia . Expert Opin Pharmacother 2015 ; 16:1049–1067 Crossref , Google Scholar

36 Miller BJ, Buckley P, Seabolt W, et al. : Meta-analysis of cytokine alterations in schizophrenia: clinical status and antipsychotic effects . Biol Psychiatry 2011 ; 70:663–671 Crossref , Google Scholar

37 Rabner J, Gottlieb S, Lazdowsky L, et al. : Psychosis following traumatic brain injury and cannabis use in late adolescence: a case series . Am J Addict 2016 ; 25:92–93 Crossref , Google Scholar

38 Cantor-Graae E, Selten JP : Schizophrenia and migration: a meta-analysis and review . Am J Psychiatry 2005 ; 162:12–24 Crossref , Google Scholar

39 Strauss JL, Calhoun PS, Marx CE, et al. : Comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder is associated with suicidality in male veterans with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder . Schizophr Res 2006 ; 84:165–169 Crossref , Google Scholar

40 Madras BK : History of the discovery of the antipsychotic dopamine D2 receptor: a basis for the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia . J Hist Neurosci 2013 ; 22:62–78 Crossref , Google Scholar

41 Deng C, Dean B : Mapping the pathophysiology of schizophrenia: interactions between multiple cellular pathways . Front Cell Neurosci 2013 ; 7:238 Crossref , Google Scholar

42 Correll CU, Kane JM : Schizophrenia: mechanism of action of current and novel treatments . J Clin Psychiatry 2014 ; 75:347–348 Crossref , Google Scholar

43 Jentsch JD, Roth RH : The neuropsychopharmacology of phencyclidine: from NMDA receptor hypofunction to the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia . Neuropsychopharmacology 1999 ; 20:201–225 Crossref , Google Scholar

44 McGlashan TH, Hoffman RE : Schizophrenia as a disorder of developmentally reduced synaptic connectivity . Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000 ; 57:637–648 Crossref , Google Scholar

45 Coyle JT, Tsai G, Goff D : Converging evidence of NMDA receptor hypofunction in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia . Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003 ; 1003:318–327 Crossref , Google Scholar

46 Paoletti P, Bellone C, Zhou Q : NMDA receptor subunit diversity: impact on receptor properties, synaptic plasticity and disease . Nat Rev Neurosci 2013 ; 14:383–400 Crossref , Google Scholar

47 Cohen SM, Tsien RW, Goff DC, et al. : The impact of NMDA receptor hypofunction on GABAergic neurons in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia . Schizophr Res 2015 ; 167:98–107 Crossref , Google Scholar

48 Shenton ME, Dickey CC, Frumin M, et al. : A review of MRI findings in schizophrenia . Schizophr Res 2001 ; 49:1–52 Crossref , Google Scholar

49 Kerns JG, Lauriello J : Can structural neuroimaging be used to define phenotypes and course of schizophrenia? Psychiatr Clin North Am 2012 ; 35:633–644 Crossref , Google Scholar

50 Andreasen NC, Liu D, Ziebell S, et al. : Relapse duration, treatment intensity, and brain tissue loss in schizophrenia: a prospective longitudinal MRI study . Am J Psychiatry 2013 ; 170:609–615 Crossref , Google Scholar

51 Cannon TD : How schizophrenia develops: cognitive and brain mechanisms underlying onset of psychosis . Trends Cogn Sci 2015 ; 19:744–756 Crossref , Google Scholar

52 Santos E, Noggle CA: Encyclopedia of Child Behavior and Development. New York, Springer, 2011, pp 1464–1465 Google Scholar

53 Maibing CF, Pedersen CB, Benros ME, et al. : Risk of schizophrenia increases after all child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: a nationwide study . Schizophr Bull 2015 ; 41:963–970. Crossref , Google Scholar

54 Vorstman JA, Burbach JP: Autism and schizophrenia: genetic and phenotypic relationships; in Comprehensive Guide to Autism. Edited by Patel VB, Preedy VR, Martin CR. New York, Springer, 2014, pp 1645–1662 Google Scholar

55 Cechnicki A, Bielańska A, Hanuszkiewicz I, et al. : The predictive validity of expressed emotions (EE) in schizophrenia. A 20-year prospective study . J Psychiatr Res 2013 ; 47:208–214 Crossref , Google Scholar

56 Macmillan JF, Crow TJ, Johnson AL, et al. : Expressed emotion and relapse in first episodes of schizophrenia . Br J Psychiatry 1987 ; 151:320–323 Crossref , Google Scholar

57 Juola P, Miettunen J, Veijola J, et al. : Predictors of short- and long-term clinical outcome in schizophrenic psychosis—the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort study . Eur Psychiatry 2013 ; 28:263–268 Crossref , Google Scholar

58 Ryan ME, Melzer T : Delusions in schizophrenia: where are we and where do we need to go? Int J School Cogn Psychol 2014 ; 1:115 Google Scholar

59 Laursen TM, Munk-Olsen T, Vestergaard M : Life expectancy and cardiovascular mortality in persons with schizophrenia . Curr Opin Psychiatry 2012 ; 25:83–88 Crossref , Google Scholar

60 Tsai J, Rosenheck RA : Psychiatric comorbidity among adults with schizophrenia: a latent class analysis . Psychiatry Res 2013 ; 210:16–20 Crossref , Google Scholar

61 Buckley PF, Miller BJ, Lehrer DS, et al. : Psychiatric comorbidities and schizophrenia . Schizophr Bull 2009 ; 35:383–402 Crossref , Google Scholar

62 Estrada G, Fatjó-Vilas M, Muñoz MJ, et al. : Cannabis use and age at onset of psychosis: further evidence of interaction with COMT Val158Met polymorphism . Acta Psychiatr Scand 2011 ; 123:485–492 Crossref , Google Scholar

63 Tibbo P, Kroetsch M, Chue P, et al. : Obsessive-compulsive disorder in schizophrenia . J Psychiatr Res 2000 ; 34:139–146 Crossref , Google Scholar

64 Angermeyer MC : Schizophrenia and violence . Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2000 ; 102(s407):63–67 Crossref , Google Scholar

65 Scott CL, Resnick PJ : Violence risk assessment in persons with mental illness . Aggress Violent Behav 2006 ; 11:598–611 Crossref , Google Scholar

66 Resnick PJ : The detection of malingered psychosis . Psychiatr Clin North Am 1999 ; 22:159–172 Crossref , Google Scholar

67 Appelbaum PS, Grisso T : Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment . N Engl J Med 1988 ; 319:1635–1638 Crossref , Google Scholar

68 Appelbaum PS, Grisso T : The MacArthur Treatment Competence Study: I. Mental illness and competence to consent to treatment . Law Hum Behav 1995 ; 19:105–126 Crossref , Google Scholar

69 Torrey EF, Yolken RH : Psychiatric genocide: Nazi attempts to eradicate schizophrenia . Schizophr Bull 2010 ; 36:26–32. Crossref , Google Scholar

- Techniques for Measurement of Serotonin: Implications in Neuropsychiatric Disorders and Advances in Absolute Value Recording Methods 29 November 2023 | ACS Chemical Neuroscience, Vol. 14, No. 24

- Transferosome-Based Intranasal Drug Delivery Systems for the Management of Schizophrenia: a Futuristic Approach 15 December 2023 | BioNanoScience, Vol. 15

- Evaluation of psychometric properties of a leaflet developed for schizophrenia 17 May 2023 | International Journal of Social Psychiatry, Vol. 69, No. 7

- Association Between Childhood Exposure to Pet Cats and Later Diagnosis of Schizophrenia: A Case-Control Study in Saudi Arabia Cureus, Vol. 36

- Adult abuse and poor prognosis in Taiwan, 2000–2015: a cohort study 6 December 2022 | BMC Public Health, Vol. 22, No. 1

- The differential associations of positive and negative symptoms with suicidality Schizophrenia Research, Vol. 248

- A Literature Review on the Efficacy of Injectable Neuroleptics in the Treatment of Schizophrenia 8 August 2022 | Undergraduate Research in Natural and Clinical Science and Technology (URNCST) Journal, Vol. 6, No. 8

- Effectiveness of sensory modulation for people with schizophrenia: A multisite quantitative prospective cohort study 19 April 2022 | Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, Vol. 69, No. 4

- New Paradigms of Old Psychedelics in Schizophrenia 23 May 2022 | Pharmaceuticals, Vol. 15, No. 5

- Study on Executive Function of Schizophrenia Patients Advances in Psychology, Vol. 12, No. 09

- Incidence of Orthostatic Hypotension in Schizophrenic Patients Using Antipsychotics at Sambang Lihum Mental Health Hospital, South Kalimantan 30 August 2021 | Borneo Journal of Pharmacy, Vol. 4, No. 3

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

- Early Signs

What Are the Different Types of Schizophrenia?

Subtypes No Longer Used in Diagnosis

Why the DSM-5 Eliminated Schizophrenia Types

Dsm-5 criteria for schizophrenia, paranoid schizophrenia, disorganized (hebephrenic) schizophrenia, residual schizophrenia, catatonic schizophrenia, undifferentiated schizophrenia, schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

- Next in Schizophrenia Guide Early Signs and Symptoms of Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is no longer diagnosed with subtypes. It’s considered a chronic mental health condition that exists on a spectrum. Schizophrenia interferes with a person's perception of reality. People with schizophrenia face emotional difficulties and trouble thinking rationally and clearly. They also have challenges in their relationships with others.

This article will discuss the former schizophrenia subtypes, including why they are no longer used for diagnosis, though can be helpful for providers who treat people living with schizophrenia.

Verywell / Cindy Chung

Until the most recent version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders ( DSM-5 ) was published in 2013, schizophrenia was officially recognized as having five distinct subtypes:

- Disorganized/ hebephrenic

- Undifferentiated

However, mental health experts said that the symptoms of each subtype were not reliable or consistently valid and got in the way of making a diagnosis . Therefore, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) removed schizophrenia subtypes from the DSM-5.

Although they are no longer used for diagnosis, some mental health providers find schizophrenia subtypes can be helpful when they're deciding on the best treatment for someone with the condition.

The symptoms of the schizophrenia subtypes overlap with those of other mental health conditions. To be diagnosed with schizophrenia, a person must meet the criteria outlined in the DSM-5.

A person must have two or more of the following symptoms for at least one month (or less if they have been treated), and at least one symptom must be delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech:

- Positive symptoms (those abnormally present): Hallucinations, such as hearing voices or seeing things that do not exist; paranoia; and exaggerated or distorted perceptions, beliefs, and behaviors

- Negative symptoms (those abnormally absent): A loss of or a decrease in the ability to initiate plans, speak, express emotion, or find pleasure

- Disorganized symptoms: Confused and disordered thinking and speech, trouble with logical thinking, and sometimes bizarre behavior or abnormal movements

Continuous signs of the disturbance must be present for at least six months. Within that time, at least one month must include the above symptoms (or less if the person has been successfully treated).

A person may also have periods of prodromal or residual symptoms.

- A prodrome is the period of early, mild symptoms before a full-on episode.

- Residual schizophrenia is the phase after a person has had an episode where the symptoms are not totally resolved but are not as intense as they were during the episode. Usually, they only have negative symptoms of schizophrenia or very mild positive symptoms.

During prodromal or residual periods, a person may only have negative symptoms or could have two or more symptoms listed above in an attenuated form—that is, odd beliefs or unusual perceptual experiences.

A person must also show a decreased level of functioning in daily life, such as doing self-care, managing their relationships, or working. During this phase, people may start to withdraw socially, lose interest in their usual activities, or struggle with personal hygiene.

Schizoaffective disorder and depressive or bipolar disorder with psychotic features have to be ruled out before a diagnosis of schizophrenia can be made.

This schizophrenia subtype is the one that often comes to mind when people think of schizophrenia. It is also the type that is most often depicted in the media and popular culture.

Fixed, false beliefs that conflict with reality ( delusions ) are a hallmark of paranoid schizophrenia. Hallucinations, particularly hearing voices (auditory hallucinations), are also common.

Paranoid schizophrenia primarily involves the onset of traits, feelings, or behaviors that were not there before—referred to as positive symptoms.

Positive symptoms of schizophrenia include the following:

- Preoccupation with one or more delusions

- Auditory hallucinations

In paranoid schizophrenia, the following symptoms are not typically present (or if they are, they are not prominent):

- Disorganized speech

- Disorganized or catatonic behavior

- Flat or inappropriate affect

Symptoms Can Come and Go

The symptoms of schizophrenia may not be experienced all at once. A person living with the illness may experience different symptoms at different times.

Disorganized schizophrenia is also called hebephrenic schizophrenia. This subtype of schizophrenia is characterized by symptoms that interrupt a person's thinking and communication (disorganized symptoms).

People with this schizophrenia subtype may have the following symptoms:

- Disorganized behavior

Here are some common challenges that people with hebephrenic schizophrenia may face:

- Difficulty with routine tasks like personal hygiene and self-care

- Reacting emotionally in ways that are incongruous or inappropriate to the situation

- Trouble with communication

- Misusing words or placing them in the wrong order

- Difficulty thinking clearly and responding appropriately

- Speaking in neologisms (the use of nonsense words or making up words)

- Moving quickly between thoughts without logical connections

- Forgetting or misplacing items

- Pacing or walking in circles

- Difficulty understanding everyday things

- Giving unrelated answers to questions

- Repeating phrases or words

- Trouble with completing tasks or meeting goals

- Challenges with impulse control

- Failing to make eye contact

- Showing childlike behaviors

- Withdrawing socially

Residual schizophrenia is not the same as the residual phase of schizophrenia. The residual phase of schizophrenia is a period when a person's symptoms are not as intense. However, they may still have negative symptoms—for example, a previous trait or behavior stops, or there's a lack of a trait or behavior that would normally be present.

A person with residual schizophrenia does not currently have prominent delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, or highly disorganized or catatonic behavior. Instead, they have negative symptoms and/or two or more diagnostic symptoms of schizophrenia in a milder form (such as odd beliefs or unusual perceptual experiences).

Symptoms of residual schizophrenia can include:

- Blunted affect (e.g., trouble expressing emotions, diminished facial expressions or expressive gestures)

- Odd beliefs

- Unusual perceptions

- Social withdrawal

Other Conditions

People with schizophrenia can also have other mental health disorders at the same time (co-occurring or co-morbid conditions), including depression and substance use disorders.

A person with catatonic schizophrenia meets the criteria for a diagnosis of schizophrenia and also has symptoms of catatonia . Catatonia involves excessive movement (excited catatonia) or decreased movement (retarded catatonia) that affects both speech and behavior.

Catatonic schizophrenia symptoms may include the following:

- Catalepsy (muscular rigidity, lack of response to external stimuli)

- Waxy flexibility (limbs remain for an unusually long time in the position they are placed by another)

- Stupor (unresponsiveness to most stimuli)

- Excessive motor activity (apparently purposeless activity not influenced by external stimuli)

- Extreme negativism (apparently motiveless resistance to all instructions or maintenance of a rigid posture against attempts to be moved)

- Mutism (lack of speech)

- Posturing (voluntary assumption of inappropriate or bizarre postures)

- Stereotyped movements (involuntary, repetitive physical movements such as rocking)

- Prominent grimacing (distorting the face in an expression, usually of pain, disgust, or disapproval)

- Echolalia (repeating what others say)

- Echopraxia (imitating the movements of others)

A person with undifferentiated schizophrenia has symptoms that fit a diagnosis of schizophrenia but do not completely fit with the paranoid type, catatonic type, or disorganized type.

There are no specific symptoms that indicate undifferentiated schizophrenia. Instead, a person shows many symptoms that do not meet the full criteria for a particular subtype.

The symptoms of undifferentiated schizophrenia may include:

- Hallucinations

- Exaggerated or distorted perceptions, beliefs, and behaviors

- Unusual or disorganized speech

- Neglect of personal hygiene

- Social withdrawal

- Excessive sleeping or a lack of sleep

- Difficulty making plans

- Problems with emotions and emotional expression

- Trouble with logical thinking

- Bizarre behavior

- Abnormal movements

Childhood Schizophrenia

Childhood schizophrenia is not a subtype of schizophrenia. This term refers to the age of onset of schizophrenia, not a separate diagnosis.

There are other disorders on the schizophrenia spectrum, along with schizophrenia. The conditions are listed in the DSM-5-TR as “schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders.”

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders include:

- Schizoaffective disorder

- Delusional disorder

- Brief psychotic disorder

- Schizophreniform disorder

Schizoaffective Disorder

Schizoaffective disorder has features of schizophrenia and features of a mood disorder, either major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder .

Symptoms of schizoaffective disorder fall into the following three categories:

Delusional Disorder

Delusional disorder is a form of psychosis in which a person has fixed, false beliefs. For example, a person with delusion disorder may believe a celebrity is in love with them, that someone is spying on them or "out to get them," or that they have a great talent or importance. They may also hold other beliefs that are outside the realm of reality.

Brief Psychotic Disorder

Brief psychotic disorder is an episode of psychotic behavior with a sudden onset that lasts less than a month. After the episode, the person goes into complete remission. However, it is possible to have another psychotic episode in the future.

A brief psychotic episode is characterized by the sudden onset of delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized speech. The symptoms are are often triggered by stress and only last a few days. For example, a person who witnesses a traumatic event may have hallucinations or delusions temporarily in response to the severe stress of what they experienced.

Schizophreniform Disorder

With schizophreniform disorder, a person has symptoms of schizophrenia that last less than six months.

Schizotypal Personality Disorder

Schizotypal personality disorder involves having odd beliefs, perceptions, and behaviors. A person with schizotypical personality disorder can be suspicious or paranoid of others and often has limited relationships.

Paranoid, disorganized/hebephrenic, residual, catatonic, and undifferentiated schizophrenia are no longer diagnoses in the DSM-5.

However, since the subtypes can show the different ways that schizophrenia spectrum disorders can be experienced, some providers find it useful to talk about them when they're working with patients.

Today, schizophrenia is considered a spectrum disorder that includes schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, brief psychotic disorder, schizophreniform disorder, and schizoaffective disorder.

American Psychiatric Association. What is schizophrenia? ,

Administration SA and MHS. Table 3. 22, DSM-IV to DSM-5 schizophrenia comparison .

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Table 3.22, DSM-IV to DSM-5 Schizophrenia Comparison . [Internet] Rockville (MD) (US); 2016 Jun.

Mental Health UK. Types of schizophrenia .

NIMH. Schizophrenia .

Schennach R, Riedel M, Obermeier M, et al. What are residual symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorder? Clinical description and 1-year persistence within a naturalistic trial. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci . 2015;265(2):107-116. doi:10.1007/s00406-014-0528-2

Khokhar JY, Dwiel LL, Henricks AM, Doucette WT, Green AI. The link between schizophrenia and substance use disorder: A unifying hypothesis . Schizophr Res . 2018;194:78-85. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2017.04.016

Castle, DJ, Buckley, PF, & Upthegrove, R. Schizophrenia and psychiatric comorbidities: Recognition and management . (2021). Oxford University Press.

Rasmussen SA, Mazurek MF, Rosebush PI. Catatonia: Our current understanding of its diagnosis, treatment and pathophysiology . World J Psychiatry . 2016;6(4):391-398. Published 2016 Dec 22. doi:10.5498/wjp.v6.i4.391

Kendhari J, Shankar R, Young-Walker L. A review of childhood-onset schizophrenia . Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ) . 2016;14(3):328-332. doi:10.1176/appi.focus.20160007

APA. DSM-5-TR fact sheets .

APA. Schizoaffective disorder .

APA. Delusional disorder .

APA. Brief psychotic disorder .

APA. Schizophreniform disorder .

APA. Schizotypal personality disorder .

By Heather Jones Heather M. Jones is a freelance writer with a strong focus on health, parenting, disability, and feminism.

Transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses.

Información en español

Celebrating 75 Years! Learn More >>

- Health Topics

- Brochures and Fact Sheets

- Help for Mental Illnesses

- Clinical Trials

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder characterized by disruptions in thought processes, perceptions, emotional responsiveness, and social interactions. Although the course of schizophrenia varies among individuals, schizophrenia is typically persistent and can be both severe and disabling.

Symptoms of schizophrenia include psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions, and thought disorder (unusual ways of thinking), as well as reduced expression of emotions, reduced motivation to accomplish goals, difficulty in social relationships, motor impairment, and cognitive impairment. Although symptoms typically start in late adolescence or early adulthood, schizophrenia is often viewed from a developmental perspective. Cognitive impairment and unusual behaviors sometimes appear in childhood, and persistent presence of multiple symptoms represent a later stage of the disorder. This pattern may reflect disruptions in brain development as well as environmental factors such as prenatal or early life stress. This perspective fuels the hope that early interventions will improve the course of schizophrenia which is often severely disabling when left untreated.

Additional information can be found on the NIMH Health Topics page on Schizophrenia .

Age-Of-Onset for Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is typically diagnosed in the late teens years to early thirties, and tends to emerge earlier in males (late adolescence – early twenties) than females (early twenties – early thirties). 1,2 More subtle changes in cognition and social relationships may precede the actual diagnosis, often by years.

Prevalence of Schizophrenia

Precise prevalence estimates of schizophrenia are difficult to obtain due to clinical and methodological factors such as the complexity of schizophrenia diagnosis, its overlap with other disorders, and varying methods for determining diagnoses. Given these complexities, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders are often combined in prevalence estimation studies. A summary of currently available data is presented here.

- Across studies that use household-based survey samples, clinical diagnostic interviews, and medical records, estimates of the prevalence of schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders in the U.S. range between 0.25% and 0.64%. 3,4,5

- Estimates of the international prevalence of schizophrenia among non-institutionalized persons is 0.33% to 0.75%. 6,7

Burden of Schizophrenia

Despite its relatively low prevalence, schizophrenia is associated with significant health, social, and economic concerns.

- Schizophrenia is one of the top 15 leading causes of disability worldwide. 8

- The estimated average potential life lost for individuals with schizophrenia in the U.S. is 28.5 years. 10

- Co-occurring medical conditions, such as heart disease, liver disease, and diabetes, contribute to the higher premature mortality rate among individuals with schizophrenia. 10 Possible reasons for this excess early mortality are increased rates of these medical conditions and under-detection and under-treatment of them. 13