- Technical Help

- CE/CME Help

- Billing Help

- Sales Inquiries

Qualitative Data Analysis

This course provides an applied approach to qualitative data analysis through the lens of multiple methods and methodologies.

About this Course

The analysis of qualitative research data is a fundamental yet multifaceted process that requires careful attention to the unique qualities of qualitative research design. This course provides an applied, phenomenological approach to qualitative data analysis. It is designed for an interdisciplinary audience with examples taken from the nonprofit, commercial, and government sectors in the health and social sciences.

Undergraduate/graduate students, research staff, and IRB members in particular may find this course meaningful as an introduction to qualitative research methods.

Course Preview:

Language Availability: English

Suggested Audiences: Faculty, IRB Chairs, IRB Members, Research Staff, Undergraduate and Graduate Students

Organizational Subscription Price: $675 per year/per site for government and non-profit organizations; $750 per year/per site for for-profit organizations Independent Learner Price: $99 per person

Course Content

" role="button"> introduction to qualitative data analysis.

This module discusses the data analysis considerations shared by all qualitative methods and approaches this course covers. This includes the basic qualitative data analysis process and tools and the rigorous and ethical approaches to qualitative data analysis that apply across methods.

Recommended Use: Required ID (Language): 20971 (English) Author(s): Margaret R. Roller, MA - Roller Research

" role="button"> In-Depth Interview Method

This module begins with an overview of the basic in-depth interview method and its variations. This provides the foundation for the core discussions concerning the distinctive aspects of the in-depth interview method that affect qualitative data analysis, including quality and ethical considerations.

Recommended Use: Supplemental ID (Language): 20972 (English) Author(s): Margaret R. Roller, MA - Roller Research

" role="button"> Focus Group Discussion Method

To provide a basis for the core discussions, this module begins with an overview of the fundamentals of the focus group method and its variations. This provides an understanding of the distinctive aspects of the focus group method that affect qualitative data analysis, including quality and ethical considerations.

Recommended Use: Supplemental ID (Language): 20973 (English) Author(s): Margaret R. Roller, MA - Roller Research

" role="button"> Ethnography

Understanding the ethnographic approach and its variations is important to the discussion of data analysis. For this reason, the module begins with an overview of ethnographic research and the distinctive aspects of ethnography that affect qualitative data analysis, including quality and ethical considerations.

Recommended Use: Supplemental ID (Language): 20974 (English) Author(s): Margaret R. Roller, MA - Roller Research

" role="button"> Narrative Research

This module provides an overview of narrative research and its variations. It provides an overview of narrative research, which serves as a foundation for the core discussions concerning the distinctive aspects of the narrative research approach that affect qualitative data analysis. The module concludes with a discussion of quality and ethical considerations.

Recommended Use: Supplemental ID (Language): 20975 (English) Author(s): Margaret R. Roller, MA - Roller Research

" role="button"> Case Study Research

Case study research and its variations are examined at the start of this module. Then, distinctive aspects of case study research that affect qualitative data analysis are explored, including quality and ethical considerations.

Recommended Use: Supplemental ID (Language): 20976 (English) Author(s): Margaret R. Roller, MA - Roller Research

" role="button"> Qualitative Content Analysis Method

This module reviews the basic Qualitative Content Analysis (QCA) method and its variations. It also discusses the distinctive aspects of the QCA method that affect qualitative data analysis and the quality and ethical considerations that QCA presents.

Recommended Use: Supplemental ID (Language): 20977 (English) Author(s): Margaret R. Roller, MA - Roller Research

Who should take the Qualitative Data Analysis course?

The suggested audience includes students, faculty, and staff that want to learn more about the basics of qualitative data analysis and one or more of the discussed methods.

How long does it take to complete the Qualitative Data Analysis course?

This course consists of one required module and six supplemental modules. All learners should complete module 1 and then complete the supplemental modules as needed (20-30 minutes each).

" role="button"> Why should an organization subscribe to this course?

Organizational subscriptions provide access to the organization's affiliated members. This allows organizations to train individuals across the organization on how to properly conduct qualitative data analysis.

" role="button"> What are the standard recommendations for learner groups?

This course is designed such that learners should complete the first module and then any following method modules as needed.

" role="button"> Is this course eligible for continuing medical education credits?

This course does not currently have CE/CME credits available.

Related Content

This course provides learners with an understanding of how to improve study design, collect and analyze data, and promote reproducible research.

Essentials of observational research protocol design and development.

Foundational course that orients and prepares learners to engage with the scholarly publication process in an informed way.

An in-depth review of the development and execution of protocols.

Privacy Overview

Cookies on this website

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you click 'Accept all cookies' we'll assume that you are happy to receive all cookies and you won't see this message again. If you click 'Reject all non-essential cookies' only necessary cookies providing core functionality such as security, network management, and accessibility will be enabled. Click 'Find out more' for information on how to change your cookie settings.

- Study with us

- Short Courses in Qualitative Research Methods

- Introduction to Analysing Qualitative Data

Study with us:

- Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods

- Introduction to doing Qualitative Interviews

- Introduction to conversation analysis and health care encounters

- Learning with the book: an introduction to qualitative research methods for health research

This course will provide you with a good introduction to qualitative data analysis. Our expert tutors will support you to develop and practice your analysis skills using a combination of online lectures, group discussions, and practical online workshops.

This two-day online course introduces the principles and practice of qualitative data analysis, with emphasis on thematic analysis.

Over two days our approachable and research-active experts will show that analysis is achievable though an accessible step-by-step process, and will provide de-identified data for you to work with. Day one begins by looking at organising data (coding categorising and theme development); day two explores 'finding a story' and developing your analysis to translate to a research paper or thesis chapter.

We aim to support those who are planning to undertake or manage qualitative research using in-depth or semi-structured interviews or qualitative observational data, and support those who have already collected qualitative data which they are unsure how to analyse. The thematic analysis approach used is also applicable to other kinds of qualitative data including observation, diaries, and other text sources. While the course is aimed at the needs of health and care professionals, researchers, academics and postgraduate students, the skills developed here apply to many settings - please ask us if you are unsure whether Analysing Qualitative Data is the course for you.

COURSE DELIVERY

Please note that some of the teaching sessions for this online course will involve you participating in live, interactive Zoom sessions, which will fall between the hours of 09:00 and 17:00 UK time . We are very happy to welcome bookings wherever you are internationally, but please make sure that you are able to attend video calls between these hours.

The course will include:

- Expert-led lectures (a mixture of live and pre-recorded) on the principles of qualitative data analysis, with emphasis on thematic analysis

- Demonstrations and small group work to develop skills in coding and categorising qualitative data and in data interpretation

- Practical online exercises considering how to conduct and recognise 'good quality' qualitative analysis

- Expert feedback to support your learning and understanding

Learning outcomes

Learning Outcomes

By the end of the course participants will:

- Have an understanding of the principles of qualitative data analysis with emphasis on thematic analysis

- Have gained practical experience of coding, categorising, and conceptualising qualitative data or qualitative observational data using a thematic analysis approach

We provide:

- Access to the online learning platform (CANVAS)

- Online access to slides and materials

- De-identified data for you to work on whilst developing your skills

- Experienced, approachable tutors who are research-active

Online course

Date: 11-12 March 2024

Course details:

Course fee: £750 Duration: 2 days Total places: 24 Venue: Online Course

If you have any questions and queries please email us

“Fantastic teaching, great content, personal insight / experiences, putting it into practice and great to meet so many other people involved in qual research... Excellent course!”

“It has been a real privilege to attend a course led by such high quality, high calibre speakers – sharing the theory but intertwined with the reality of their own experiences and interests and passions.”

"A highlight was realising how far I’d come and how much I’d learned! Feeling inspired to try out what I’ve learned, thank you”

COURSE TUTORS

Lisa Hinton

Catherine Pope

Sue Ziebland

and expert tutors from the Medical Sociology & Health Experiences Research Group team

Oxford Qualitative Courses

This highly-regarded programme is delivered in online and face to face formats to suit a range of learners. We use a mixture of lectures and small group work, delivered by our team of qualitative researchers from the University of Oxford’s Medical Sociology and Health Experiences Research Group . Our group has run these successful courses for almost twenty years alongside active involvement in qualitative research on a variety of different topics, ranging from studies of personal experiences of health conditions and of healthcare practice, to evaluations of organisational change. Our group also includes qualitative methodologists at the forefront of developing qualitative methods including conversation analysis and evidence synthesis.

Findings from our group’s research on patient experiences, together with supported video, audio and text extracts, have been compiled to form the multi-award winning heathtalk.org website and its sister site socialcaretalk.org . Our portfolio of research and expertise informs current local, national and international healthcare policy and research.

The syllabuses of our qualitative courses draw on a wide range of expertise from within our research group, including the disciplinary areas of medical sociology, anthropology, and public policy.

Receive our bulletin:

Our courses are popular and often sell-out quickly. To receive a bulletin of upcoming course dates, please register here .

Got a question? Contact us:

Our friendly team are on-hand to answer your questions and queries.

Email: [email protected]

Make a Gift

Qualitative Research

The Odum Institute provides ongoing consulting services and short courses on qualitative research and related software. Qualitative research is a social scientific method for collecting textual, visual, or audio data.

Consultations & Guest Lectures

Consultations.

If you have questions regarding research design, data collection, strategies for analysis, and options for reporting findings , please contact Paul Mihas using the information provided below. Paul can also provide consultations on deductive, inductive, and abductive perspectives that inform qualitative research.

Paul can help you through any of the stages of your project, including the early stages of developing research questions and proposal writing, such as: Designing a study, data collection, analysis, developing research products .

Assistant Director of Qualitative and Mixed Methods Research

Guest lectures.

Time permitting, Paul is also available to give guest lectures on various qualitative research topics at classes and meetings. If you would like to schedule a guest lecture on a qualitative research topic, please contact Paul Mihas directly or visit our guest lecture page .

Back to top

Qualitative Research Traditions

- Generic qualitative

- Thematic qualitative research

- Phenomenology

- Ethnography

- Narrative Analysis

- Grounded Theory

Mixed Methods

Paul can also assist if you are conducting a study combining or connecting qualitative and quantitative data. Please visit our mixed methods page for more information.

Project Planning, Data Collection and Analysis

As part of a fee-based service , the Odum Institute offers project-based design and analysis using strategies customized for each project’s needs. These range from evaluation projects to multi-year research studies. Assistant Director Paul Mihas, with the assistance of graduate students, can help with:

- Research design

- Developing interview and focus group guides

- Conducting data collection

- Data analysis using specialized software

- Final reports

Dissertation & Master’s Thesis Assistance

If you would like Paul Mihas to provide feedback regarding a master’s thesis or dissertation proposal or draft of a chapter, please feel free to contact him at [email protected] .

Qualitative Data Analysis Software

The Odum Institute provides specialized computer programs that provide tools for mixed methods analyses; these include QSR NVivo, ATLAS.ti, MAXQDA, and a web-based program, Dedoose .

Odum offers short courses on these programs as well as consultations regarding their use. Please see the current Institute short course schedule or contact Paul Mihas to arrange a customized presentation for graduate or undergraduate classes or other special audiences.

QRS NVivo is a software program for coding and analyzing textual and multimedia data . It also allows researchers to construct diagrams (“mind maps” and “concept maps”) of codes and transcripts and automatically generates comparison diagrams to assess differences between codes or transcripts.

Its analytical strengths include:

- Cluster analysis of transcripts and multidimensional matrix analysis of codes

- Quantitative variables for “mixing” quantitative and qualitative data.

ATLAS.ti , a program for analyzing textual and multimedia data , allows users to analyze data based on codes and analytical memos . The software also allows users to create diagrams of transcripts, quotations, memos, and codes and to create links between these “objects” in diagrams.

The query tool lets users ask complex questions of their data, including Boolean searches or queries based on demographics. A co-occurrence table allows researchers to review conceptual intersections of codes. A joint-display matrix allows users to combine qualitative codes and quantitative variables.

MAXQDA is a qualitative analysis software package that helps researchers code textual, audio, or video data and analyze coded segments .

The software also allows users to merge qualitative and quantitative analysis by exporting and importing variables to and from SPSS and Excel. The software includes a mixed methods set of tools for generating tables that “mix” the qualitative codes and quantitative variables. A memo-writing feature allows users to add reflective writing to their analytic process.

A content analysis feature allows researchers to create a special dictionary of keywords. Intercoder reliability features are also available.

Dedoose is a web-based application for analyzing qualitative and mixed methods research with text, images, audio, videos, and spreadsheet data . The program provides numerous user-friendly charts for making sense of mixed methods studies.

Learning Opportunities

Qualitative research summer intensive:.

The Odum Institute has joined ResearchTalk, Inc. , in presenting the Qualitative Research Summer Intensive , a five-day qualitative research professional development course series, offered annually in July. The intensive includes courses on qualitative traditions, research design, data collection, analysis, and innovative strategies in the field.

Examples & Resources

Consultants at the Odum Institute have authored several online articles regarding specific qualitative methods. For more information, please visit the Sage website regarding learning to use:

Grounded Theory jQuery(document).ready(function(){ jQuery('.osc_tooltip').tooltip({ template:' ' }).on('shown.bs.tooltip', function(){ jQuery( '.tooltip.oscitas-bootstrap-container' ).attr( 'aria-hidden', 'false'); }).on('hidden.bs.tooltip', function(){ jQuery( '.tooltip.oscitas-bootstrap-container' ).attr( 'aria-hidden', 'true'); }); });

Phenomenological analysis jquery(document).ready(function(){ jquery('.osc_tooltip').tooltip({ template:'' }).on('shown.bs.tooltip', function(){ jquery( '.tooltip.oscitas-bootstrap-container' ).attr( 'aria-hidden', 'false'); }).on('hidden.bs.tooltip', function(){ jquery( '.tooltip.oscitas-bootstrap-container' ).attr( 'aria-hidden', 'true'); }); });, analyze written text jquery(document).ready(function(){ jquery('.osc_tooltip').tooltip({ template:'' }).on('shown.bs.tooltip', function(){ jquery( '.tooltip.oscitas-bootstrap-container' ).attr( 'aria-hidden', 'false'); }).on('hidden.bs.tooltip', function(){ jquery( '.tooltip.oscitas-bootstrap-container' ).attr( 'aria-hidden', 'true'); }); });, narrative analysis jquery(document).ready(function(){ jquery('.osc_tooltip').tooltip({ template:'' }).on('shown.bs.tooltip', function(){ jquery( '.tooltip.oscitas-bootstrap-container' ).attr( 'aria-hidden', 'false'); }).on('hidden.bs.tooltip', function(){ jquery( '.tooltip.oscitas-bootstrap-container' ).attr( 'aria-hidden', 'true'); }); });, build a codebook jquery(document).ready(function(){ jquery('.osc_tooltip').tooltip({ template:'' }).on('shown.bs.tooltip', function(){ jquery( '.tooltip.oscitas-bootstrap-container' ).attr( 'aria-hidden', 'false'); }).on('hidden.bs.tooltip', function(){ jquery( '.tooltip.oscitas-bootstrap-container' ).attr( 'aria-hidden', 'true'); }); });, charmazian grounded theory jquery(document).ready(function(){ jquery('.osc_tooltip').tooltip({ template:'' }).on('shown.bs.tooltip', function(){ jquery( '.tooltip.oscitas-bootstrap-container' ).attr( 'aria-hidden', 'false'); }).on('hidden.bs.tooltip', function(){ jquery( '.tooltip.oscitas-bootstrap-container' ).attr( 'aria-hidden', 'true'); }); });, visual analysis jquery(document).ready(function(){ jquery('.osc_tooltip').tooltip({ template:'' }).on('shown.bs.tooltip', function(){ jquery( '.tooltip.oscitas-bootstrap-container' ).attr( 'aria-hidden', 'false'); }).on('hidden.bs.tooltip', function(){ jquery( '.tooltip.oscitas-bootstrap-container' ).attr( 'aria-hidden', 'true'); }); });, analyze oral discourse jquery(document).ready(function(){ jquery('.osc_tooltip').tooltip({ template:'' }).on('shown.bs.tooltip', function(){ jquery( '.tooltip.oscitas-bootstrap-container' ).attr( 'aria-hidden', 'false'); }).on('hidden.bs.tooltip', function(){ jquery( '.tooltip.oscitas-bootstrap-container' ).attr( 'aria-hidden', 'true'); }); });, instrument development jquery(document).ready(function(){ jquery('.osc_tooltip').tooltip({ template:'' }).on('shown.bs.tooltip', function(){ jquery( '.tooltip.oscitas-bootstrap-container' ).attr( 'aria-hidden', 'false'); }).on('hidden.bs.tooltip', function(){ jquery( '.tooltip.oscitas-bootstrap-container' ).attr( 'aria-hidden', 'true'); }); });.

The Qualitative Research Resources Page from the UNC Health Sciences Library is also an excellent resource for information on qualitative research methods.

Qualitative Research Certificate

Graduate Certificate

The Qualitative Research Certificate consists of four three-credit hour courses (12 credit hours) developed to prepare students and professionals to understand a broad and in-depth knowledge of qualitative research approaches and to conduct qualitative research studies.

Over recent years, qualitative research has been increasingly conducted and influential in educational research across disciplines.

The Qualitative Research Certificate within the College of Education at Purdue University requires students to obtain a minimum grade of B for each course while also maintaining an overall GPA of 3.0/4.0. This certificate program accepts applications from Purdue University graduate students from any Purdue West Lafayette graduate programs.

This residential program has rolling admission. Applications must be fully complete and submitted (including all required materials) and all application fees paid prior to the deadline in order for applications to be considered and reviewed. For a list of all required materials for this program application, please see the “Admissions” tab below.

July 1 is the deadline for Fall applications.

November 15 is the deadline for Spring applications.

March 15 is the deadline for Summer applications.

This program does not lead to licensure in the state of Indiana or elsewhere. Contact the College of Education Office of Teacher Education and Licensure (OTEL) at [email protected] before continuing with program application if you have questions regarding licensure or contact your state Department of Education about how this program may translate to licensure in your state of residence.

Application Instructions for the Qualitative Research Certificate from the Office of Graduate Studies :

In addition to a submitted application (and any applicable application fees paid), the following materials are required for admission consideration, and all completed materials must be submitted by the application deadline in order for an application to be considered complete and forwarded on to faculty and the Purdue Graduate School for review.

Here are the materials required for this application:

- Official, current Purdue transcripts

- Graduate School Form 18 for Dual Enrolled students. Please upload this form with your application with your signature and information only. Our office will obtain the necessary faculty signatures.

- Academic Statement of Purpose

- Personal History Statement

We encourage prospective students submit an application early, even if not all required materials are uploaded. Applications are not forwarded on for faculty review until all required materials are uploaded.

When submitting your application for this program, please select the following options:

- Select a Campus: Purdue West Lafayette (PWL)

- Select your proposed graduate major: Curriculum and Instruction

- Please select an Area of Interest: Curriculum Studies

- Please select a Degree Objective: Qualitative Research Graduate Certificate

- Primary Course Delivery: Residential

Program Requirements

Required courses.

- EDCI 61500: Qualitative Research Methods in Education (3 cr.) A course providing an introduction to qualitative research methods in education.

- EDCI 61600: Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Educational Research (3 cr.) A course focused on collection and analysis of qualitative data

- Elective #1: with focus on qualitative methods (3 cr.)

- Elective #2: with focus on qualitative methods (3 cr.)

- CAND 99100: Candidate (Must be registered as a candidate for graduation to receive the Certificate) Candidate registration should be completed through the Office of Graduate Studies when registering for the final course. Student must contact the office directly at [email protected] . Failure to register properly will result in a delay of being awarded the certificate

- EDCI 567: Action Research in Science Education

- EDCI 59100: Research in International Contexts

- EDCI 591: Technology for Qualitative Research

- EDCI 612: Literacy Research Methodologies

- ANTH 605: Seminar in Ethnographic Analysis

- COM 584: Historical/Critical Research in Communication

- HDFS 679: Qualitative Research on Families

- TECH 697: Qualitative Research Methods in Technology Studies

- WGSS 680: Feminist Theory

- WGSS 682: Issues in Feminist Research and Methodology

- Other elective courses may be approved (before completing) by the faculty advisor in the home department in conjunction with the Qualitative Research Certificate coordinator in the Dept. of Curriculum and Instruction

APPLICATION PROCEDURE

Course Content Information or Blackboard: Contact Dr. Stephanie Zywicki Course Registration, payment, drops/withdraws, and removing holds: [email protected] Career accounts: ITaP (765) 494-4000

- Student Login

- Instructor Login

- Areas of Study

- Art and Design

- Behavioral Health Sciences

- Business Administration

- Leadership and Management

- Project Management

- See the full list

- Construction and Sustainability

- Humanities and Languages

- Mathematics and Statistics

- Sciences and Biotechnology

- Chemistry and Physics

- Clinical Laboratory Science

- Health Advising

- Life Science Business and Biotechnology

- Online Sciences Courses

- Technology and Information Management

- Writing, Editing and Technical Communication

- Transfer Credit

- Transfer Credit Courses

- Online Learning

- Online Courses and Certificates

- Information Sessions

- Career Services

- Career-Development Courses

- Professional Internship Program

- Custom Programs

- For Universities and Organizations

- Academic Services

- Transcripts

- General Information

- Community Guidelines

- Course and Program Information

- Latest COVID-19 Information

- Online Course Policies

- Certificates, Programs and CEUs

- Concurrent Enrollment

- International Student Services

- Student Aid

- Disability Support Services

- Financial Assistance

- Voices Home

- Educator Insights

- Student Stories

- Professional Pathways

- Industry Trends

- Free and Low Cost Events

- Berkeley Global

Qualitative Research: Design, Implementation and Methods

DESIGN X440.2

Get an introduction to what qualitative research is, the types of qualitative research methods, the appropriate situations to apply qualitative methods, and how to conduct your own qualitative research. You learn to build a research protocol and use various techniques to design, conduct, analyze and present an informative research study.

At the end of the course, you are expected to conduct your own qualitative research study . To that end, you develop a research plan based on the given situation, collect data using qualitative methodologies , engage with various techniques for coding and analyzing qualitative data effectively, and present the data and insights in a manner that is best aligned with the goals of the research.

Prerequisites: None.

Course Outline

Course Objectives

- Understand what constitutes qualitative research, how it differs from quantitative research and when to apply qualitative research methods

- Identify and formulate appropriate qualitative research plans

- Apply qualitative research data collection techniques

- Develop coding schemes for analysis of qualitative data

- Present qualitative data to inform and influence

What You Learn

- Developing qualitative research questions

- Building a research protocol

- Observing, listening and probing: the core skills of a qualitative researcher

- Qualitative sampling and participant recruitment

- Understanding an overview of the qualitative data analysis process

- Communicating your findings, from summary to interpretation

- Presenting qualitative results

How You Learn

We are online! All of the design classes are conducted online and include video classes, mentor-led learning and peer-to-peer support through our student online platform, Canvas.

- Reading assignments

- Quizzes at instructor’s discretion

- Small-group activities

- Homework assignments

- Capstone project

Is This Course Right for You?

This course is intended for students in the Professional Program in User Experience (UX) Design , or anybody interested in obtaining skills in qualitative research. You do not need preexisting research experience for this course. Our experienced instructors provide practical information, leverage their qualitative research skills and monitor your development along with peer-to-peer support on our student online platform.

Summer 2024 enrollment opens on March 18!

Thank you for your interest in this course!

The course you have selected is currently not open for enrollment.

Enter your email below to be notified when it becomes available.

Required Field

Get Notified

We're excited that you have chosen us as your education provider.

Once a section for this class is available, we will email you with enrollment information.

Your privacy is important to us .

Email Privacy Policy

Your privacy is important to us!

We do not share your information with other organizations for commercial purposes.

We only collect your information if you have subscribed online to receive emails from us.

We do not partner with or have special relationships with any ad server companies.

If you want to unsubscribe, there is a link to do so at the bottom of every email.

Read the full Privacy Policy

← Back to your information .

Session Time-Out

Privacy policy, cookie policy.

This statement explains how we use cookies on our website. For information about what types of personal information will be gathered when you visit the website, and how this information will be used, please see our Privacy Policy .

How we use cookies

All of our web pages use "cookies". A cookie is a small file of letters and numbers that we place on your computer or mobile device if you agree. These cookies allow us to distinguish you from other users of our website, which helps us to provide you with a good experience when you browse our website and enables us to improve our website.

We use cookies and other technologies to optimize your website experience and to deliver communications and marketing activities that are targeted to your specific needs. Some information we collect may be shared with selected partners such as Google, Meta/Facebook or others. By browsing this site you are agreeing to our Privacy Policy . You can revoke your voluntary consent to participate in monitored browsing and targeted marketing by selecting “Disable All Cookies” below.

Types of cookies we use

We use the following types of cookies:

- Strictly necessary cookies - these are essential in to enable you to move around the websites and use their features. Without these cookies the services you have asked for, such as signing in to your account, cannot be provided.

- Performance cookies - these cookies collect information about how visitors use a website, for instance which pages visitors go to most often. We use this information to improve our websites and to aid us in investigating problems raised by visitors. These cookies do not collect information that identifies a visitor.

- Functionality cookies - these cookies allow the website to remember choices you make and provide more personal features. For instance, a functional cookie can be used to remember the items that you have placed in your shopping cart. The information these cookies collect may be anonymized and they cannot track your browsing activity on other websites.

Most web browsers allow some control of most cookies through the browser settings. To find out more about cookies, including how to see what cookies have been set and how to manage and delete them please visit https://www.allaboutcookies.org/.

Specific cookies we use

The list below identify the cookies we use and explain the purposes for which they are used. We may update the information contained in this section from time to time.

- JSESSIONID: This cookie is used by the application server to identify a unique user's session.

- registrarToken: This cookie is used to remember items that you have added to your shopping cart

- locale: This cookie is used to remember your locale and language settings.

- cookieconsent_status: This cookie is used to remember if you've already dismissed the cookie consent notice.

- _ga_UA-########: These cookies are used to collect information about how visitors use our site. We use the information to compile reports and to help us improve the website. The cookies collect information in an anonymous form, including the number of visitors to the website, where visitors have come to the site from and the pages they visited. This anonymized visitor and browsing information is stored in Google Analytics.

Changes to our Cookie Statement

Any changes we may make to our Cookie Policy in the future will be posted on this page.

Short courses

Qualitative Research Methods in Health

- 10am - 1pm each day

Cost: £1,500

Book a place.

Please email [email protected] if you wish to apply for this course. The next course will start on 3 October 2024

This course aims to equip you with the knowledge and skills to understand, design and conduct high quality qualitative research.

The course will help you:

- gain a clear understanding of the principles of qualitative research

- practise skills including interviewing, running a focus group, data analysis, and developing and presenting a research protocol

This course will be delivered online over 10 Thursday mornings from 3 October to 12 December.

This course is run by researchers from the UCL Centre for Excellence in Qualitative Research, within the Research Department of Primary Care and Population Health (PCPH).

Who it's for

This course is for:

- Master's level students, PhD students and research staff who need to design and conduct a qualitative study

- those who wish to know how to assess the quality of qualitative research (e.g. funders, journal editors, ethical committee members etc.)

You don't need to have any previous experience of qualitative research, but you will need to do some preparation before each session.

Course content

Lead: Julia Bailey and Tom Witney

This workshop will help you understand the basis on which qualitative methodology is selected as a research approach.

- learn about the philosophical debates around qualitative research

- contrast qualitative and quantitative approaches

- discuss the place of qualitative research in health and medicine

You'll also critique a published paper of a qualitative study. This will help you reflect on a completed study and consider not only the methodological approach and selection of methods, but also practical aspects such as sampling, what counts as data, the position of the researcher, data analysis, and application of findings.

Learning objectives

By the end of this workshop you'll be able to:

- describe key features of qualitative research

- explain the rationale for key features of qualitative research design

- know when qualitative or quantitative study designs are appropriate

- understand how ‘theory’ is relevant for qualitative research

Leads: Harpreet Sihre and Silvie Cooper

On this workshop you'll learn about qualitative research interviewing techniques and developing topic guides.

You'll explore structured, semi-structured and in-depth interview methods and their application, using real world examples. However, the emphasis will be on semi-structured interview techniques.

You'll also learn about and discuss:

- the importance of different communication styles and researcher reflexivity

- practical issues such as structuring questions, building rapport and dealing with challenging interviews

You'll be encouraged to think of an area of research around which you'll structure and produce a topic guide for use in a practical session. You'll also get the opportunity to practice your newly developed interviewing skills.

As far as possible, the workshop is tailored towards research that those attending are planning/doing.

By the end of this workshop you'll be able to:

- describe and distinguish between structured, semi-structured and 'in-depth' interviewing

- formulate and construct a topic guide

- apply and evaluate some key interviewing skills

Lead: Tom Witney and Fiona Aspinal

This workshop will introduce you to focus groups - a key qualitative research method.

You'll learn about the:

- different stages of the research process where focus groups can be used

- types of research questions that lend themselves to this approach

- practicalities of sampling, convening and conducting focus groups, including issues to consider when researching sensitive topics

You'll also practise your communication and group facilitation skills.

You'll be encouraged to think of an area of research around which you'll structure and produce a topic guide for use in a practical session.

- explain when and how to use focus groups

- design a topic guide for a focus group study

- organise and facilitate a focus group

Leads: Nathan Davies and Fiona Stevenson

On this workshop you'll discuss a range of ways of conducting qualitative data analysis and the rationales for different approaches.

You'll be encouraged to critically reflect on how decisions made throughout research affect the type and extent of analysis possible. The importance of decisions about transcription are also stressed.

You'll consider the place of data management software in qualitative analysis. You won't be taught how to use particular software packages, but you'll discuss the advantages and disadvantages of using these.

You'll conduct a thematic analysis on a piece of data, and reflect on and consider the best approach for your own work.

Please note: this workshop does not provide training in the use of Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis packages

- distinguish between different types of qualitative data analysis

- recognise the importance of decisions relating to transcribing, reflexivity, field notes, double coding and data management

- consider various approaches to analysis

- understand the principles and practicalities of conducting a basic thematic analysis

- evaluate the benefits of Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis for your projects

Leads: Jane Wilcock and Stephanie Kumpunen

In this interactive workshop you'll plan your own qualitative study design.

You'll work on your own and in small and large groups, with an experienced tutor. You'll also have the opportunity for one-to-one and small group discussions and advice on qualitative study design.

The first day is spent planning your study in a structured way. On the second day you'll present your study design proposal to tutors and other students in small groups, and discuss research issues arising from the proposed studies.

- write clear research questions

- understand the principles of (and debates about) quality in qualitative research

- plan a qualitative research study, specifying the details of how a study will be carried out

- present a four-slide summary of your study design

- discuss the rationale for chosen study designs

Teaching and assessment

The course is highly interactive, involving a range of teaching techniques including group work, practical tasks and discussion.

It will be run with a mixture of synchronous, online learning (e.g. presentations, small group discussions) and asynchronous learning (pre-recorded videos, readings, preparatory writing/planning).

You'll receive help designing and planning your own qualitative research project. You'll then present your design proposals and receive feedback from course tutors and peers at the end of the course.

You'll be required to do some preparation before each session (reading and/or watching videos).

How to apply

To apply for this course you’ll need to complete a short application form.

Your application will be judged on your suitability for the course and how much you're likely to benefit. Priority will be given to people who are actively planning or conducting qualitative research.

Please email [email protected] if you’d like to be added to the waiting list. When booking opens and there are spaces available for the course, you'll be emailed the application form.

Cancellation policy

Cancellations must be received in writing at least two weeks before the start of the event and will be subject to an administration charge of 20% of the course fee. Unfortunately, no refunds will be made within two weeks of the course date. Any refund will be made by UCL to you within 30 days of your cancellation and be paid to you in the same way as you paid for your order.

We reserve the right to cancel teaching if necessary and will, in such event, make a full refund of the registration fee. PCPH Events will not be liable for any additional incurred costs.

Further information

If you have any questions about the course content, please email Fiona Stevenson ( [email protected] ) or Julia Bailey ( [email protected] ).

For administrative queries, please contact Lynda Russell-Whitaker ( [email protected] ).

Course team

Julia Bailey - joint Course Director

Julia is an Associate Professor at the e-Health Unit at UCL and a sexual health speciality doctor in South East London. Her research interests include sexual health, e-Health, doctor-patient interaction, science communication and social science in medicine (qualitative methodologies). View Julia’s IRIS profile for more information about her work and publications.

Fiona Stevenson - joint Course Director

Fiona is a Professor of Medical Sociology and Co-Director of e-Health Unit at UCL. She’s currently Head of the Department of Primary Care and Population Health at UCL. Her research is broadly encompassed by the overarching theme of perceptions, communication and interactions about treatment. Her methodological expertise lies in qualitative methods, both in relation to thematic analysis of interviews and focus groups and conversation analysis of interactional data. She has expertise in conducting original research as well as implementing research findings into practice. View Fiona’s IRIS profile for more information about her work and publications.

Nathan Davies

Nathan is an Associate Professor and Alzheimer’s Society Fellow based in the Centre for Ageing Population Studies at UCL. His main research interests are in older adults, dementia, and supporting family carers. He's a qualitative researcher leading on several qualitative studies, which explore sensitive topics, including end of life care. In addition to experience of interviews, focus groups and various types of qualitative analysis, he has extensive experience of co-design, co-production and consensus-based methods. View Nathan’s IRIS profile for more information about his work and publications.

Jane Wilcock

Jane is a Senior Research Associate in the Centre for Ageing & Population Studies, UCL. Her main research interests are in dementia, ageing, emergent technologies and trials of complex interventions in primary care and community settings. A mixed-methods researcher, Jane has experience of a variety of study designs such as RCTs, interview and focus group studies, nominal group techniques and co-design of interventions. In addition, she is a methodology expert for the NIHR Research Design Service London. View Jane’s IRIS profile for more information about her work and publications.

Silvie Cooper

Silvie is a Lecturer (Teaching) in the Department of Applied Health Research at UCL. Her research interests include capacity building for health research, management of chronic pain, digital health, and patient education, using qualitative, mixed methods, and translational research approaches. Alongside her research, she designs and teaches on a variety of health and social science courses for undergraduates, postgraduates and professionals. Topics include research and evaluation methods, the social aspects of health and illness, and the impact of context, practice and policy on healthcare experiences. View Silvie’s IRIS profile for more information about her works and publications.

Harpreet Sihre

Harpreet formerly completed her PhD at the Institute of Applied Health Research, University of Birmingham, where she researched the lived experiences of South Asian women with severe postnatal psychiatric illnesses using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. She then worked at the Unit of Social and Community Psychiatry on an NIHR-funded study researching accessibility and acceptability of Perinatal Mental Health Services.

Harpreet’s research interests encompass mental health, perinatal mental health, access to services and equality, diversity and inclusion, using qualitative research methods. Harpreet has taught on both undergraduate and postgraduate courses, including small group teaching and lecturing at the University of Birmingham and Queen Mary University. View Harpreet’s IRIS profile for more information about her work and publications.

Tom is a Research Fellow at the department of Primary Care and Population Health . He is a qualitative health researcher, with a particular interest in sexual health and relationship intimacy. His current work focuses on improving access to sexual health for trans and gender diverse people and supporting uptake of chlamydia retesting following a diagnosis. View Tom’s Iris profile for more information about his work and publications.

Fiona Aspinal

Fiona is based in the Department of Applied Health Research for the NIHR ARC North Thames as 'Senior Research Associate in Qualitative Methods Applied to Organisational Research in Health' where, as part of the ARC North Thames' Research Partnership Team, she helps to facilitate and support health and social care research with local, regional and national relevance. She is also the social care research lead for NIHR CRN North Thames.

Her areas of research interest are: Qualitative research and evaluation of complex health and social care interventions and organisations; The experience and outcomes of integrated care policy and practice for staff, service users and informal carers; Social and community health care for adults, including people with dementia; Social care research infrastructure/skills.

At UCL, in addition to the Qualitative Research Methods in Health short course, Fiona teaches on research methods and social science courses and modules, such as the BSc Population Health Sciences, the Medicine MBBS BSc and the Population Health MSc. She also supervises undergraduate and postgraduate students. View Fiona’s Iris profile for more information about her work and publications.

Stephanie Kumpunen

Stephanie is a THIS Institute Doctoral Fellow at UCL and a Senior Fellow in Health Policy at Nuffield Trust (a London-based health and care think tank). Her research focuses on the organisation of Primary Care and community-based health and care services.

Stephanie has led on a number of qualitative studies and mixed-methods evaluations. She has a particular interest in rapid qualitative approaches; namely rapid ethnographies that inform health and care service improvement. View Stephanie’s UCL profile for more information about her work and publications.

“The course is a really a great opportunity to read, reflect, discuss and share research, which is helpful for personal and professional development.” [Academic Clinical Fellow, Spring 2022]

“This session really helped me to organise my thoughts and put together a coherent plan for future research. It will make writing my protocol very easy!” [PhD Student, Spring 2022]

“It was such an excellent course. The information and materials provided were straight to the point and helpful, the working atmosphere was inspiring and constructive, and the tasks were interesting and activating. Thank you to all tutors!” [Clinical Research Programme Coordinator, Spring 2022]

“Great tutors, great reading material. It was very interesting to hear other peoples' experiences. Although this course was virtual, there were plenty of opportunities for interaction. I now have a better understanding and I am confident to run my study. I would recommend this course to anyone who wants an intro in qual research.” [Pre-Doctoral Research Fellow, 2021]

"I have a more clear understanding of the basics of qual methods, terminology and ways it may fit into my own research." [Researcher, 2019]

Course information last modified: 22 Apr 2024, 13:33

Length and time commitment

- Time commitment: 10am - 1pm each day

- Course length: 10 weeks

Contact information

- Lynda Russell-Whitaker

- [email protected]

Related Short Courses

NCRM delivers training and resources at core and advanced levels, covering quantitative, qualitative, digital, creative, visual, mixed and multimodal methods

20th Anniversary Impact Prize

Tell us how NCRM has helped you to make an impact

Short courses

Browse our calendar of training courses and events

Featured training course

Our resources

NCRM hosts a huge range of online resources, including video tutorials and podcasts, plus an extensive publications catalogue.

Online tutorials

Access more than 80 free research methods tutorials

Resources for trainers

Browse our materials for teachers of research methods

Methods News

NCRM annual lecture to explore AI in social research

Contribute to MethodsCon: Futures

Applications open for NCRM 20th Anniversary Impact Prize

10 free data analytics courses you can take online

Data analytics is the science of taking raw data, cleaning it, and analyzing it to inform conclusions and support decision making. From business to health care to social media, data analytics is changing the way organizations operate.

“It’s not hyperbole to say that data analytics has really taken over the world,” says Brian Caffo, professor of biostatistics at Johns Hopkins University’s Bloomberg School of Public Health and director of academic programs for the university’s Data Science and AI Institute. “Every domain has become increasingly quantitative to inform decision making.”

Berkeley's Data Science Master's

And this space isn’t slowing down anytime soon: The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that employment for data scientists will grow 35% from 2022 to 2032, with 17,700 new job openings projected each year on average during that decade.

Interested in becoming a data analyst? Below, we’ve compiled ten free data analytics courses to help give you a firmer grasp of this rapidly growing field.

A/B Testing

About: This course covers the design and analysis of A/B tests, which are online experiments that compare two versions of content to see which one appeals to viewers more. A/B tests are used throughout the tech industry by companies like Amazon and Google. This course is offered through Udacity.

Course length: Six self-paced modules

Who this course is for: Beginners

What you’ll learn: In this course you’ll learn about A/B testing, experiment ethics, how to choose metrics, design an experiment, and analyze results.

Prerequisites: None

Data Analytics Short Course

About: In this quick, five-tutorial course you’ll get a broad overview of data analytics. You’ll learn about the different types of roles in data analytics, a summary of the tools and skills you’ll need to develop, and a hands-on introduction to the field. This course is offered by CareerFoundry.

Course length: 75 minutes, divided into five 15-minute lessons

What you’ll learn: In this course you’ll get an introduction to data analytics. You’ll also analyze a real dataset to solve a business problem through data cleaning, visualizations, and garnering final insights.

Prerequisites: None

Data Science: R Basics

About: This program gives you a foundational knowledge of programming language R. Offered by HarvardX through the EdX platform, this course is offered for free; the paid version includes a credential. It’s the first of ten courses HarvardX offers as part of its Professional Certificate in Data Science.

Course length: Eight weeks, 1–2 hours per week

What you’ll learn: In this course you’ll learn basic R syntax and foundational R programming concepts, including data types, vectors arithmetic, and indexing. You’ll also perform operations that include sorting, data wrangling using dplyr, and making plots.

“It’s the basics of how to wrangle, analyze, and visualize data in R,” says Dustin Tingley, Harvard University’s deputy vice provost for advances in learning and a professor of government in the school’s government department. “That gets you writing a little bit of code, but you’re not doing anything that heavy.”

Prerequisites: HarvardX recommends having an up-to-date browser to enable programming directly in a browser-based interface

Fundamentals of Qualitative Research Methods

About: This course will teach you the fundamentals of qualitative research methods. Qualitative research provides deeper insights into real-world problems that might not always be immediately evident. This course is offered through Yale University on YouTube.

Course length: 90 minutes spread out over six modules

What you’ll learn: In this course you’ll learn how qualitative research is a way to systematically collect, organize, and interpret information that is difficult to measure quantitatively. This includes developing qualitative research questions, gathering data through interviews and focus groups, and analyzing this data.

“Qualitative research is the systematic, rigorous application of narratives and tools to better understand a complex phenomenon,” says Leslie Curry, a professor of public health and management at the Yale School of Public Health and a professor of management at the Yale School of Management. She adds that this approach can help understand flaws in large data sets. “It can be used as an adjunct to a lot of the really important work that’s happening in large data analysis.”

Getting and Cleaning Data

About: This course covers the basic ways that data can be obtained and how that data can be cleaned to make it “tidy.” It will also teach you the components of a complete data set, such as raw data, codebooks, processing instructions, and processed data. This course is offered by Johns Hopkins University through Coursera, and is part of a 10-course Data Science Specialization series.

Course length: Four weeks, totaling approximately 19 hours

What you’ll learn: Through this course you’ll learn about common data storage systems, how to use R for text and date manipulation, how to use data cleaning basics to make data “tidy,” and how to obtain useable data from the web, application programming interfaces (APIs), and databases.

“It’s the starting point” when it comes to data analysis, Caffo says. “Without a good data set that is cleaned and appropriate for use, you have nothing. You can talk all you want about doing models or whatnot—underlying that has to be the data to support it.”

Prerequisites: None

Introduction to Data Science with Python

About: This course teaches you concepts and techniques to give you a foundational understanding of data science and machine learning. Offered by HarvardX through the EdX platform, this course can be taken for free. The paid version offers a credential.

Course length: Eight weeks, 3–4 hours a week

Who this course is for: Intermediate

What you’ll learn: This course will give you hands-on experience using Python to solve real data science challenges. You’ll use Python programming and coding for modeling, statistics, and storytelling.

“It gets you up and running with the main workhorse tools of data analytics,” says Tingley. “It helps to set people up to take more advanced courses in things like machine learning and artificial intelligence.”

Prerequisites: None, but Tingley says having a basic background in high school-level algebra and basic probability is helpful. Some programming experience—particularly in Python—is recommended

Introduction to Databases and SQL Querying

About: In this course you’ll learn how to query a database, create tables and databases, and be proficient in basic SQL querying. This free course is offered through Udemy.

Course length: Two hours and 17 minutes

What you’ll learn: This course will acquaint you with the basic concepts of databases and queries. This course will walk you through setting up your environment, creating your first table, and writing your first query. By the course’s conclusion, you should be able to write simple queries related to dates, string manipulation, and aggregation.

Introduction to Data Analytics

About: This course offers an introduction to data analysis, the role of a data analyst, and the various tools used for data analytics. This course is offered by IBM through Coursera.

Course length: Five modules totaling roughly 10 hours

What you’ll learn: This course will teach you about data analytics and the different types of data structures, file formats, and sources of data. You’ll learn about the data analysis process, including collecting, wrangling, mining, and visualizing data. And you’ll learn about the different roles within the field of data analysis.

Learn to Code for Data Analysis

About: This course will teach you how to write your own computer programs, access open data, clean and analyze data, and produce visualizations. You’ll code in Python, write analyses and do coding exercises using the Jupyter Notebooks platform. This course is offered through the United Kingdom’s Open University on its OpenLearn platform.

Course length: Eight weeks, totaling 24 hours

What you’ll learn: In this course you’ll learn basic programming and data analysis concepts, recognize open data sources, use a programming environment to develop programs, and write simple programs to analyze large datasets and produce results.

Prerequisites: A background in coding—especially Python—is helpful

The Data Scientist’s Toolbox

About: This course will give you an introduction to the main tools and concepts of data science. You will learn the ideas behind turning data into actionable knowledge and get an introduction to tools like version control, markdown, git, GitHub, R, and RStudio. This course is offered by Johns Hopkins University through Coursera, and is part of a 10-course Data Science Specialization series.

Course length: 18 hours

What you’ll learn: This course will teach you how to set up R, RStudio, GitHub, and other tools. You will learn essential study design concepts, as well as how to understand the data, problems, and tools that data analysts use.

“That course is a very accessible introduction for anyone who wants to get started in this,” Caffo says. “It’s an overview that covers the full pipeline, from things like collecting and arranging data to asking good questions, all the way to creating a data deliverable.”

The takeaway

From businesses estimating demand for their products to political campaigns figuring out where they should run advertisements to health care professionals running clinical trials to judge a drug’s efficacy, data analytics has a wide variety of applications. Getting a better understanding of the field on your own time can be done easily and freely. And the field is only growing.

“Just about every field is having a revolution in data analytics,” Caffo says. “In fields like medicine that have always been data driven, it’s become more data-driven.”

Syracuse University MS in Applied Data Science Online

Mba rankings.

- Best Online MBA Programs for 2024

- Best Online Master’s in Accounting Programs for 2024

- Best MBA Programs for 2024

- Best Executive MBA Programs for 2024

- Best Part-Time MBA Programs for 2024

- 25 Most Affordable Online MBAs for 2024

- Best Online Master’s in Business Analytics Programs for 2024

Information technology & data rankings

- Best Online Master’s in Data Science Programs for 2024

- Most Affordable Master’s in Data Science for 2024

- Best Master’s in Cybersecurity Degrees for 2024

- Best Online Master’s in Cybersecurity Degrees for 2024

- Best Online Master’s in Computer Science Degrees for 2024

- Best Master’s in Data Science Programs for 2024

- Most Affordable Online Master’s in Data Science Programs for 2024

- Most Affordable Online Master’s in Cybersecurity Degrees for 2024

Health rankings

- Best Online MSN Nurse Practitioner Programs for 2024

- Accredited Online Master’s of Social Work (MSW) Programs for 2024

- Best Online Master’s in Nursing (MSN) Programs for 2024

- Best Online Master’s in Public Health (MPH) Programs for 2024

- Most Affordable Online MSN Nurse Practitioner Programs for 2024

- Best Online Master’s in Psychology Programs for 2024

Leadership rankings

- Best Online Doctorate in Education (EdD) Programs for 2024

- Most Affordable Online Doctorate in Education (EdD) Programs for 2024

- Coding Bootcamps in New York for 2024

- Best Data Science and Analytics Bootcamps for 2024

- Best Cybersecurity Bootcamps for 2024

- Best UX/UI bootcamps for 2024

Boarding schools

- World’s Leading Boarding Schools for 2024

- Top Boarding School Advisors for 2024

Earn Your Master’s in Data Science Online From SMU

Effectiveness of Psychosocial Skills Training and Community Mental Health Services: A Qualitative Research

- Original Paper

- Published: 22 April 2024

Cite this article

- Halil İbrahim Bilkay ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8231-960X 1 ,

- Burak Şirin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8485-5756 2 &

- Nermin Gürhan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3472-7115 2

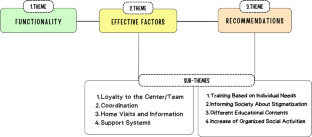

This study employs a phenomenological approach to investigate the experiences of individuals who access services at a community mental health center (CHMC) in Türkiye The aim of this study is to comprehend the experiences of individuals who participate in psychosocial skills training at the CHMC. Thematic analysis of data from sixteen in-depth interviews revealed three main themes and eight sub-themes. Functionality theme emphasizes the positive impact of CHMC services and training on daily life and social functioning. Effective Factors theme encompasses the elements that improve the effectiveness of CHMC services. Participants have provided suggestions for the content of the training under the theme of Recommendations. Study results show that CHMC services and psychosocial skills training benefit individuals' daily lives and functioning, but that opportunities for improvement exist. It is crucial to incorporate participant feedback, and further research should be conducted to investigate the effectiveness of these services in this area.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Piloting a mental health training programme for community health workers in South Africa: an exploration of changes in knowledge, confidence and attitudes

Goodman Sibeko, Peter D. Milligan, … Dan J. Stein

The experiences of lay health workers trained in task-shifting psychological interventions: a qualitative systematic review

Ujala Shahmalak, Amy Blakemore, … Waquas Waheed

“These are people just like us who can work”: Overcoming clinical resistance and shifting views in the implementation of Individual Placement and Support (IPS)

Danika Sharek, Niamh Lally, … Agnes Higgins

Abaoglu, H., Mutlu, E., Ak, S., Akı, E., & Anıl Yagcıoglu, E. (2020). The effect of life skills training on functioning in schizophrenia: A randomized controlled trial. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 46 (Suppl 1), S220. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa030.533

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Alatas, G., Karaoglan, A., Arslan, M. ve Yanik, M. (2009). Toplum temelli ruh sağlığı modeli ve Türkiye’de toplum ruh sağlığı merkezleri projesi. Nöropsikiyatri Arşivi, 46 (Özel Sayı), 25–29.

Aruldass, P., Sekar, T. S., Saravanan, S., Samuel, R., & Jacob, K. S. (2022). Effectiveness of social skills training groups in persons with severe mental illness: A pre–post intervention study. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 44 (2), 114–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/02537176211024146

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Attepe Ozden, S., Tekindal, M., Gedik, T. E., Ege, A., Erim, F. & Tekindal, M. A. (2022). Reporting qualitative research: Turkish adaptation of COREQ checklist. European Journal Of Science And Technology, (35), 522–529. https://doi.org/10.31590/ejosat.976957

Aydin, M., Altınbaş, K., Nal, Ş, Ercan, S., Ayhan, M., Usta, A., & Özbek, S. (2019). The comparison of patients with schizophrenia in community mental health centers according to living conditions in nursing home or home. Anatolian Journal of Psychiatry., 21 (1), 14–23. https://doi.org/10.5455/apd.42123

Article Google Scholar

Bag, B. (2018). An example of a model for practicing community mental health nursing: recovery. Current Approaches in Psychiatry , 10 (4), 481–493. https://doi.org/10.18863/pgy.375814

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11 (4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Bekiroglu, S., & Ozden, S. A. (2021). Psychosocial interventions for individuals with severe mental illness and their families in Turkey: A systematic review. Current Approaches in Psychiatry , 13(1), 52–76. https://doi.org/10.18863/pgy.721987

Chan, A., Wong, S., & Chien, W. (2018). A prospective cohort study of community functioning among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatry Research, 259 , 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.10.019

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Sage.

Google Scholar

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches . Sage.

Chronister, J., Fitzgerald, S., & Chou, C.-C. (2021). The meaning of social support for persons with serious mental illness: A family member perspective. Rehabilitation Psychology, 66 (1), 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000369

Corrigan, P. W., Morris, S. B., Michaels, P. J., Rafacz, J. D., & Rusch, N. (2012). Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: A meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 63 (10), 963–973. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100529

Coker, F., Yalcınkaya, A., Celik, M., & Uzun, A. (2021). The effect of community mental health center services on the frequency of hospital admission, severity of disease symptoms, functional recovery, and insight in patients with schizophrenia. Journal of Psychıatrıc Nursıng , 12 (3):181–187 https://doi.org/10.14744/phd.2021.18199

De Mamani, A. W., Altamirano, O., McLaughlin, M., & Lopez, D. (2020). Culture and family-based intervention for schizophrenia, bipolar, and other psychotic-related spectrum disorders. Cross-Cultural Family Research and Practice , 645–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-815493-9.00020-x

Ensari, H., Gultekin, B. K., Karaman, D., Koc, A., & Beskardes, A. F. (2013). The effects of the service of community mental health center on the patients with schizophrenia - evaluation of quality of life, disabilities, general and social functioning-a summary of one year follow-up. Anatolian Journal Psychiatry, 14 (82), 108-114. https://doi.org/10.5455/apd.36380

Fan, Y., Ma, N., Ouyang, A., Zhang, W., He, M., Chen, Y., Liu, J., Li, Z., Yang, J., Ma, L., & Caine, E. D. (2022). Effectiveness of a community-based peer support service among persons suffering severe mental illness in China. PeerJ, 10 , e14091. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.14091

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Guvenc, N. C., & Oner, H. (2020). Views of patient relatives and health professionals about the reasons of the patients enrolled in the community mental health center to discontinue or irregularly continue the center. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66 (7), 707–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020931875

Houser, J. (2015). Nursing research: Reading, using, and creating evidence (3rd ed.). Jones and Bartlett Learning.

Lee, H. J., Ju, Y. J., & Park, E. C. (2017). Utilization of professional mental health services according to recognition rate of mental health centers. Psychiatry Research, 250 , 204–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.051

Liberman, R. P., Wallace, C. J., Blackwell, G., Eckman, T. A., Vaccaro, J. V., & Kuehnel, T. G. (1993). Innovations in skills training for the seriously mentally ill: The UCLA social and independent living skills modules. Innovations and Research, 2 (2), 43–59.

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation: Revised and expanded from qualitative research and case study applications in education . Jossey-Bass.

Picton, C. J., Moxham, L., & Patterson, C. (2017). The use of phenomenology in mental health nursing research. Nurse Researcher, 25 (3), 14–18. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr.2017.e1513

Polit, D. F., Beck, C. T. (2004). Nursing research principles & methods , 7th Edition. Williams & Wilkins, Chapter 13: 289–314.

Potash, J. (2019). Continuous acts of creativity: Art therapy principles of therapeutic change. Art Therapy, 36 , 173–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2019.1684159

Rodriguez, A., & Smith, J. (2018). Phenomenology as a healthcare research method. Evidence Based Journals, 21 , 96–98. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2018-102990

Oren, R., Orkibi, H., Elefant, C., & Salomon-Gimmon, M. (2019). Arts-based psychiatric rehabilitation programs in the community: Perceptions of healthcare professionals. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 42 , 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000325

Shipman, S. D. (2015). The role of self-awareness in developing global competence: A qualitative multi-case study. Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Capstone s. Paper 21.

Uslu-Ak, B. (2021) Mental health and psychosocial support in Turkey: Practıces, policies and recommendations. Turkish Journal of Social Work Research , 5 (1), 46–55.

Sardogan, C., & Gultekin, B. K. (2023). The frequency of regular participation in the Community Mental Health Center (CMHC) programme of patients with the diagnosis of psychotic disorders and evaluation of related factors. Turkish Journal Clinical Psychiatry, 26 , 264–271.

Sahin, Ş, Elboga, G., & Altindag, A. (2020). The effects of the frequency of participation to the community mental health center on insight, treatment adherence and functionality. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 23 , 64–71. https://doi.org/10.5505/kpd.2020.49369

Soygur, H. (2016). Community mental health services: Quo vadis? Noropsikiyatri Arsivi, 53 (1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.5152/npa.2016.15022016

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19 (6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Townley, G., Brusilovskiy, E., Klein, L., McCormick, B., Snethen, G., & Salzer, M. S. (2022). Community mental health center visits and community mobility of people with serious mental ıllnesses: A facilitator or constraint? Community Mental Health Journal, 58 (3), 420–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-021-00821-w

Yanos, P., DeLuca, J., Roe, D., & Lysaker, P. (2020). The impact of illness identity on recovery from severe mental illness: A review of the evidence. Psychiatry Research , 288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112950

Yildirim, A., HacıhasanogluAsılar, R., Camcıoglu, T. H., Erdiman, S., & Karaagaç, E. (2015). Effect of psychosocial skills training on disease symptoms, insight, internalized stigmatization, and social functioning in patients with schizophrenia. Rehabilitation Nursing: The Official Journal of the Association of Rehabilitation Nurses, 40 (6), 341–348. https://doi.org/10.1002/rnj.195

Yildiz M. (2011). Psychological social skills training for schizophrenia patients . Turkish Social Psychiatry Association.

Yildiz, M., Kiras, F., Incedere, A., Esen, D., Gurcan, M. B., Abut, F. B., Ipci, K., & Tural, U. (2018). Development of social functioning assessment scale for people with schizophrenia: Validity and reliability study. Anatolıan Journal of Psychıatry, 19 , 29–38. https://doi.org/10.5455/apd.2374

Yildiz, M. (2019). Psychosocial skills training trainer's manual . Umuttepe Publications, 2nd Edition.

Yıldız, M. (2021). Psychosocial rehabilitation interventions in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Archives of Neuropsychiatry, 58 (Suppl 1), 77–82.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors express gratitude to the staff of the mental health center for their support and assistance during the study, as well as to the participants who generously provided responses to the questions posed.

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Samsun Mental Health and Diseases Hospital, Samsun, Türkiye

Halil İbrahim Bilkay

Psychiatric Nursing Department, Tokat Gaziosmanpasa University, Tokat, Türkiye

Burak Şirin & Nermin Gürhan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design.

Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Halil İbrahim BİLKAY and Burak ŞİRİN. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Halil İbrahim BİLKAY and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Nermin GÜRHAN read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Halil İbrahim Bilkay .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

"The study's abstract was presented as an oral presentation at the 7th International 11th National Psychiatric Nursing Congress (18-20 October 2023) in Ankara".

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Bilkay, H.İ., Şirin, B. & Gürhan, N. Effectiveness of Psychosocial Skills Training and Community Mental Health Services: A Qualitative Research. Community Ment Health J (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-024-01278-3

Download citation

Received : 29 January 2024

Accepted : 31 March 2024

Published : 22 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-024-01278-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Community mental health center

- Psychosocial skills training

- Qualitative research

- Functionality

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 24 April 2024

Exploring information needs among family caregivers of children with intellectual disability in a rural area of South Africa: a qualitative study

- Mantji Juliah Modula 1 &

- Mpho Grace Chipu 1

BMC Public Health volume 24 , Article number: 1139 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details