Reading Achievement and Motivation in Boys and Girls pp 1–28 Cite as

Motivation: Introduction to the Theory, Concepts, and Research

- Paulina Arango 4

- First Online: 03 May 2018

1588 Accesses

2 Citations

Part of the book series: Literacy Studies ((LITS,volume 15))

Motivation is a psychological construct that refers to the disposition to act and direct behavior according to a goal. Like most of psychological processes, motivation develops throughout the life span and is influenced by both biological and environmental factors. The aim of this chapter is to summarize research on the development of motivation from infancy to adolescence, which can help understand the typical developmental trajectories of this ability and its relation to learning. We will start with a review of some of the most influential theories of motivation and the aspects each of them has emphasized. We will also explore how biology and experience interact in this development, paying special attention to factors such as: school, family, and peers, as well as characteristics of the child including self-esteem, cognitive development, and temperament. Finally, we will discuss the implications of understanding the developmental trajectories and the factors that have an impact on this development, for both teachers and parents.

- Achievement

- Motivational theories

- Influences on motivation

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

This is not intended to be an exhaustive review of motivational theories. For a more detailed review see: (Dörnyei and Ushioda 2013 ; Eccles and Wigfield 2002 ; Wentzel and Miele 2009 ; Wigfield et al. 2007 ).

For more information on the development of motivation in adults you can see: Carstensen 1993 ; Kanfer and Ackerman 2004 ; Wlodkowski 2011 .

Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk taking behavior. Psychological Review, 64 (6), 359–372. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0043445 .

Article Google Scholar

Atkinson, J. W., & Raynor, J. O. (1978). Personality, motivation, and achievement . Oxford: Hemisphere.

Google Scholar

Aunola, K., Leskinen, E., Onatsu-Arvilommi, T., & Nurmi, J. E. (2002). Three methods for studying developmental change: A case of reading skills and self-concept. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 72 (3), 343–364. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709902320634447 .

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory . Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1991). Self-regulation of motivation through anticipatory and self-reactive mechanisms. In R. A. Dienstbier (Ed.), Perspectives on motivation: Nebraska symposium on motivation (Vol. 38, pp. 69–164). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control . New York: Freeman.

Bandura, A. (1999). A social cognitive theory of personality. In L. Pervin & O. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality (2nd ed., pp. 154–196). New York: Guilford.

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (2001). Self-efficacy beliefs as shapers of children’s aspirations and career trajectories. Child Development, 72 (1), 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00273 .

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., & Damasio, A. R. (2000). Emotion, decision making and the orbitofrontal cortex. Cerebral Cortex, 10 (3), 295–307. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/10.3.295 .

Boulton, M. J., Don, J., & Boulton, L. (2011). Predicting children’s liking of school from their peer relationships. Social Psychology of Education, 14 (4), 489–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-011-9156-0 .

Bradley, R. H., & Corwyn, R. F. (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 53 (1), 371–399. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233 .

Brechwald, W. A., & Prinstein, M. J. (2011). Beyond homophily: A decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21 (1), 166–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00721.x .

Buss, D. M. (2008). Human nature and individual differences. In S. E. Hampson & H. S. Friedman (Eds.), The handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 29–60). New York: The Guilford Press.

Cain, K. M., & Dweck, C. S. (1989). The development of children’s conceptions of Intelligence; A theoretical framework. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Advances in the psychology of human intelligence (Vol. 5, pp. 47–82). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Cain, K., & Dweck, C. S. (1995). The relation between motivational patterns and achievement cognitions through the elementary school years. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 41 (1), 25–52.

Carlson, C. L., Mann, M., & Alexander, D. K. (2000). Effects of reward and response cost on the performance and motivation of children with ADHD. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24 (1), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005455009154 .

Carstensen, L. L. (1993, January). Motivation for social contact across the life span: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. In Nebraska symposium on motivation (Vol. 40, pp. 209–254).

Catalano, R. F., Berglund, M. L., Ryan, J. A., Lonczak, H. S., & Hawkins, J. D. (2004). Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591 (1), 98–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716203260102 .

Coll, C. G., Bearer, E. L., & Lerner, R. M. (2014). Nature and nurture: The complex interplay of genetic and environmental influences on human behavior and development . Mahwah: Psychology Press.

Collins, W. A., Maccoby, E. E., Steinberg, L., Hetherington, E. M., & Bornstein, M. H. (2000). Contemporary research on parenting: The case for nature and nurture. American Psychologist, 55 (2), 218–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003–066X.55.2.218 .

Conger, R. D., Wallace, L. E., Sun, Y., Simons, R. L., McLoyd, V. C., & Brody, G. H. (2002). Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology, 38 (2), 179. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012–1649.38.2.179 .

Connell, J. P. (1985). A new multidimensional measure of children’s perception of control. Child Development, 56 (4), 1018–1041. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130113 .

Damasio, A. R., Everitt, B. J., & Bishop, D. (1996). The somatic marker hypothesis and the possible functions of the prefrontal cortex [and discussion]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 351 (1346), 1413–1420. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1996.0125 .

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self–determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11 (4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01 .

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002a). The paradox of achievement: The harder you push, the worse it gets. In J. Aronson (Ed.), Improving academic achievement: Impact of psychological factors on education (pp. 61–87). San Diego: Academic Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002b). Self–determination research: Reflections and future directions. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self–determination theory research (pp. 431–441). Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2013). Teaching and researching: Motivation . London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315833750 .

Book Google Scholar

Dweck, C. S. (2002). The development of ability conceptions. In A. Wigfield & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Development of achievement motivation (pp. 57–88). San Diego: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978–012750053–9/50005–X .

Eccles, J. S. (1987). Gender roles and women’s achievement–related decisions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 11 (2), 135–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471–6402.1987.tb00781.x .

Eccles, J. S. (1993). School and family effects on the ontogeny of children’s interests, self–perceptions, and activity choice. In J. Jacobs (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation, 1992: Developmental perspectives on motivation (pp. 145–208). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Eccles, J. S., & Harold, R. D. (1993). Parent–school involvement during the early adolescent years. Teachers’ College Record, 94 , 568–587.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (1995). In the mind of the actor: The structure of adolescents’ achievement task values and expectancy–related beliefs. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21 (3), 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167295213003 .

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53 (1), 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153 .

Eccles, J. S., Wigfield, A., Harold, R., & Blumenfeld, P. B. (1993). Age and gender differences in children’s self– And task perceptions during elementary school. Child Development, 64 (3), 830–847. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467–8624.1993.tb02946.x .

Eccles, J. S., Wigfield, A., & Schiefele, U. (1998). Motivation to succeed. In W. Damon (Series Ed.) & N. Eisenberg (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of Child Psychology (5th ed. Vol. 3, pp. 1017–1095). New York: Wiley.

Eccles–Parsons, J., Adler, T. F., & Kaczala, C. M. (1982). Socialization of achievement attitudes and beliefs: Parental influences. Child Development, 53 (2), 310–321. https://doi.org/10.2307/1128973 .

Eccles–Parsons, J., Adler, T. F., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., Kaczala, C. M., Meece, J. L., et al. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motivation (pp. 75–146). San Francisco: Freeman.

Eggen, P. D., & Kauchak, D. P. (2007). Educational psychology: Windows on classrooms . Virginia: Prentice Hall.

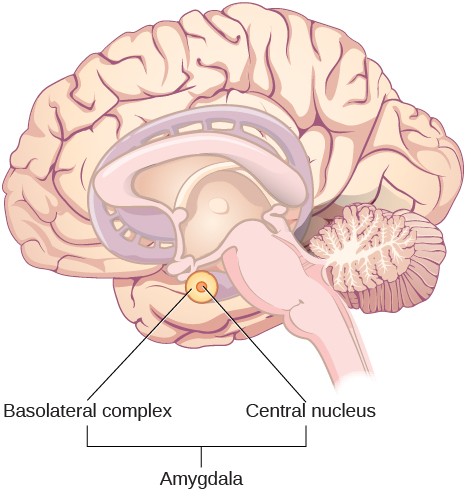

Ernst, M. (2014). The triadic model perspective for the study of adolescent motivated behavior. Brain and Cognition, 89 , 104–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2014.01.006 .

Ernst, M., & Fudge, J. L. (2009). A developmental neurobiological model of motivated behavior: Anatomy, connectivity and ontogeny of the triadic nodes. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 33 (3), 367–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.10.009 .

Ernst, M., & Paulus, M. P. (2005). Neurobiology of decision making: A selective review from a neurocognitive and clinical perspective. Biological Psychiatry, 58 (8), 597–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.004 .

Ernst, M., Pine, D. S., & Hardin, M. (2006). Triadic model of the neurobiology of motivated behavior in adolescence. Psychological Medicine, 36 (03), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291705005891 .

Ernst, M., Romeo, R. D., & Andersen, S. L. (2009). Neurobiology of the development of motivated behaviors in adolescence: A window into a neural systems model. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 93 (3), 199–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2008.12.013 .

Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2002). Children’s competence and value beliefs from childhood through adolescence: Growth trajectories in two male–sex–typed domains. Developmental Psychology, 38 (4), 519–533. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012–1649.38.4.519 .

Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2004). Parental influences on youth involvement in sports. In M. R. Weiss (Ed.), Developmental sport and exercise psychology: A lifespan perspective (pp. 145–164). Morgantown: Fitness Information Technology.

Freud, S. (1920). Beyond the pleasure principle . London: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis.

Friedel, J. M., Cortina, K. S., Turner, J. C., & Midgley, C. (2007). Achievement goals, efficacy beliefs and coping strategies in mathematics: The roles of perceived parent and teacher goal emphases. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 32 (3), 434–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2006.10.009 .

Furrer, C., & Skinner, E. (2003). Sense of relatedness as a factor in children’s academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95 (1), 148–162. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022–0663.95.1.148 .

Gallardo, L. O., Barrasa, A., & Guevara–Viejo, F. (2016). Positive peer relationships and academic achievement across early and midadolescence. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 44 (10), 1637–1648. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2016.44.10.1637 .

Glenn, S., Dayus, B., Cunningham, C., & Horgan, M. (2001). Mastery motivation in children with down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research and Practice, 7 (2), 52–59. https://doi.org/10.3104/reports.114 .

Gniewosz, B., Eccles, J. S., & Noack, P. (2015). Early adolescents’ development of academic self-concept and intrinsic task value: The role of contextual feedback. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 25 (3), 459–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12140 .

Gunderson, E. A., Ramirez, G., Levine, S. C., & Beilock, S. L. (2012). The role of parents and teachers in the development of gender–related math attitudes. Sex Roles, 66 (3–4), 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9996-2 .

Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., & Perencevich, K. C. (Eds.). (2004). Motivating reading comprehension: Concept oriented reading instruction . Mahwah: Erlbaum. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410610126 .

Harackiewicz, J. M., Barron, K. E., & Elliot, A. J. (1998). Rethinking achievement goals: When are they adaptive for college students and why? Educational Psychologist, 33 (1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3301_1 .

Heckhausen, H. (1987). Emotional components of action: Their ontogeny as reflected in achievement behavior. In D. Gîrlitz & J. F. Wohlwill (Eds.), Curiosity, imagination, and play (pp. 326–348). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Heckhausen, J. (2000). Motivational psychology of human development: Developing motivation and motivating development . Amsterdam: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4115(00)80003-5 .

Hokoda, A., & Fincham, F. D. (1995). Origins of children’s helpless and mastery achievement patterns in the family. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87 (3), 375–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.87.3.375 .

Hull, C. L. (1943). Principles of behavior: An introduction to behavior theory . Oxford: Appleton-Century Company, Incorporated.

Jacobs, J. E., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Parents, task values, and real-life achievement-related choices. In C. Sansone & J. M. Harackiewicz (Eds.), Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The search for optimal motivation and performance (pp. 405–439). San Diego: Academic Press.

Jacobs, J. E., Lanza, S., Osgood, D. W., Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Changes in children’s self-competence and values: Gender and domain differences across grades one through twelve. Child Development, 73 (2), 509–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00421 .

Jacobs, J. E., Davis-Kean, P., Bleeker, M., Eccles, J. S., & Malanchuk, O. (2005). I can, but I don’t want to. The impact of parents, interests, and activities on gender differences in math. In A. Gallagher & J. Kaufman (Eds.), Gender differences in mathematics: An integrative psychological approach (pp. 246–263). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

James, W. (1963). Psychology . New York: Fawcett.

Kahne, J., Nagaoka, J., Brown, A., O’Brien, J., Quinn, T., & Thiede, K. (2001). Assessing after-school programs as contexts for youth development. Youth & Society, 32 (4), 421–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X01032004002 .

Kanfer, R., & Ackerman, P. L. (2004). Aging, adult development, and work motivation. Academy of Management Review, 29 (3), 440–458. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2004.13670969 .

Karbach, J., Gottschling, J., Spengler, M., Hegewald, K., & Spinath, F. M. (2013). Parental involvement and general cognitive ability as predictors of domain-specific academic achievement in early adolescence. Learning and Instruction, 23 , 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.09.004 .

King, R. B., & Ganotice, F. A., Jr. (2014). The social underpinnings of motivation and achievement: Investigating the role of parents, teachers, and peers on academic outcomes. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 23 (3), 745–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-013-0148-z .

Kleinginna, P. R., Jr., & Kleinginna, A. M. (1981). A categorized list of motivation definitions, with a suggestion for a consensual definition. Motivation and Emotion, 5 (3), 263–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00993889 .

Lee, J., & Shute, V. J. (2010). Personal and social-contextual factors in K–12 academic performance: An integrative perspective on student learning. Educational Psychologist, 45 (3), 185–202. 1080/00461520.2010.493471 .

Lee, V. E., & Smith, J. (2001). Restructuring high schools for equity and excellence: What works . New York: Teachers College Press.

Linnenbrink, E. A. (2005). The dilemma of performance-approach goals: The use of multiple goal contexts to promote students’ motivation and learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97 (2), 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.2.197 .

Logan, M., & Skamp, K. (2008). Engaging students in science across the primary secondary interface: Listening to the students’ voice. Research in Science Education, 38 (4), 501–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-007-9063-8 .

Mantzicopoulos, P., French, B. F., & Maller, S. J. (2004). Factor structure of the pictorial scale of perceived competence and social acceptance with two pre-elementary samples. Child Development, 75 (4), 1214–1228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00734.x .

Marjoribanks, K. (2002). Family and school capital: Towards a context theory of students’ school outcomes . Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-9980-1 .

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50 (4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346 .

McDougal, W. (1908). An introduction to social psychology . Boston: John W. Luce and Co..

McInerney, D. M. (2008). Personal investment, culture and learning: Insights into school achievement across Anglo, aboriginal, Asian and Lebanese students in Australia. International Journal of Psychology, 43 (5), 870–879. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590701836364 .

Midgley, C. (Ed.). (2014). Goals, goal structures, and patterns of adaptive learning . Abingdon: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410602152 .

Murdock, T. B., Hale, N. M., & Weber, M. J. (2001). Predictors of cheating among early adolescents: Academic and social motivations. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 26 (1), 96–115. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.2000.1046 .

National Research Council. (2004). Engaging schools: Fostering high school students’ motivation to learn . Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.42–1079 .

Nelson, R. M., & DeBacker, T. K. (2008). Achievement motivation in adolescents: The role of peer climate and best friends. The Journal of Experimental Education, 76 (2), 170–189. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.76.2.170-190 .

Niccols, A., Atkinson, L., & Pepler, D. (2003). Mastery motivation in young children with Down’s syndrome: Relations with cognitive and adaptive competence. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 47 (2), 121–133. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00452.x .

Nicholls, J. G. (1979). Development of perception of own attainment and causal attributions for success and failure in reading. Journal of Educational Psychology, 71 (1), 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.71.1.94 .

Nicholls, J. G., & Miller, A. T. (1984). The differentiation of the concepts of difficulty and ability. Child Development, 54 (4), 951–959. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129899 .

Patrick, H., Anderman, L. H., Ryan, A. M., Edelin, K. C., & Midgley, C. (2001). Teachers’ communication of goal orientations in four fifth-grade classrooms. The Elementary School Journal, 102 (1), 35–58. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1002168 .

Pavlov, I. P. (2003). Conditioned reflexes . Mineola: Courier Corporation.

Pesu, L. A., Aunola, K., Viljaranta, J., & Nurmi, J. E. (2016a). The development of adolescents’ self-concept of ability through grades 7–9 and the role of parental beliefs. Frontline Learning Research, 4 (3), 92–109. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v4i3.249 .

Pesu, L., Viljaranta, J., & Aunola, K. (2016b). The role of parents’ and teachers’ beliefs in children’s self-concept development. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 44 , 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2016.03.001 .

Petri, H. L., & Govern, J. M. (2012). Motivation: Theory, research, and application . Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing.

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). Multiple goals, multiple pathways: The role of goal orientation in learning and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92 (3), 544–555. 10.I037//0022-O663.92.3.544 .

Pintrich, P. R. (2003). A motivational science perspective on the role of student motivation in learning and teaching contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95 (4), 667. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.4.667 .

Pintrich, P. R., & Maehr, M. L. (2004). Advances in motivation and achievement: Motivating students, improving schools (Vol. 13). Bingley: Emerald Grup Publishing Limited.

Ratelle, C. F., Guay, F., Larose, S., & Senécal, C. (2004). Family correlates of trajectories of academic motivation during a school transition: A semiparametric group-based approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96 (4), 743. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.4.743 .

Roeser, R. W., Eccles, J. S., & Sameroff, A. J. (1998). Academic and emotional functioning in early adolescence: Longitudinal relations, patterns, and prediction by experience in middle school. Development and Psychopathology, 10 (02), 321–352.

Roeser, R. W., Marachi, R., & Gelhbach, H. (2002). A goal theory perspective on teachers’ professional identities and the contexts of teaching. In C. M. Midgley (Ed.), Goals, goal structures, and patterns of adaptive learning (pp. 205–241). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80 (1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0092976 .

Ryan, A. M. (2001). The peer group as a context for the development of young adolescents’ motivation and achievement. Child Development, 72 (4), 1135–1150. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00338 .

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). An overview of self-determination theory: An organismic-dialectical perspective. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination theory research (pp. 3–33). Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

Schunk, D. H., & Pajares, F. (2002). The development of academic self-efficacy. In A. Wigfield & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Development of achievement motivation (pp. 15–32). San Diego: Academic Press.

Schunk, D. H., Meece, J. R., & Pintrich, P. R. (2012). Motivation in education: Theory, research, and applications . Harlow: Pearson Higher Ed.

Shell, D. F., Colvin, C., & Bruning, R. H. (1995). Self-efficacy, attribution, and outcome expectancy mechanisms in reading and writing achievement: Grade-level and achievement-level differences. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87 (3), 386–398. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.87.3.386 .

Shin, H., & Ryan, A. M. (2014). Friendship networks and achievement goals: An examination of selection and influence processes and variations by gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43 (9), 1453–1464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0132-9 .

Simpkins, S. D., Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Charting the Eccles’ expectancy-value model from mothers’ beliefs in childhood to youths’ activities in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 48 (4), 1019–1032. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027468 .

Simpson, R. D., & Oliver, J. (1990). A summary of major influences on attitude toward and achievement in science among adolescent students. Science Education, 74 (1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.3730740102 .

Sjaastad, J. (2012). Sources of inspiration: The role of significant persons in young people’s choice of science in higher education. International Journal of Science Education, 34 (10), 1615–1636. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2011.590543 .

Skinner, B. F. (1963). Operant behavior. American Psychologist, 18 (8), 503–515. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045185 .

Skinner, E. A. (1995). Perceived control, motivation, and coping . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Skinner, E. A., Chapman, M., & Baltes, P. B. (1988). Control, meansends, and agency beliefs: A new conceptualization and its measurement during childhood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54 (1), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.1.117 .

Skinner, E. A., Gembeck-Zimmer, M. J., & Connell, J. P. (1998). Individual differences and the development of perceived control. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 6 (2/3. Serial No. 254), 1–220.

Stipek, D., Recchia, S., McClintic, S., & Lewis, M. (1992). Self-evaluation in young children. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development , 57 (1. Serial No. 226) 1–97.

Swarat, S., Ortony, A., & Revelle, W. (2012). Activity matters: Understanding student interest in school science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 49 (4), 515–537. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21010 .

Tenenbaum, H. R., & Leaper, C. (2003). Parent-child conversations about science: The socialization of gender inequities? Developmental Psychology, 39 (1), 34–47. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.39.1.34 .

Thorndike, E. L. (1927). The law of effect. The American Journal of Psychology, 39 (1/4), 212–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/141541310.2307/1415413 .

Ushioda, E. (2007). Motivation, autonomy and sociocultural theory. In P. Benson (Ed.), Learner autonomy 8: Teacher and learner perspectives (pp. 5–24). Dublin: Authentik.

Vallerand, R. J. (1997). Toward a hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 29 , 271–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60019-2 .

Vedder-Weiss, D., & Fortus, D. (2013). School, teacher, peers, and parents’ goals emphases and adolescents’ motivation to learn science in and out of school. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 50 (8), 952–988. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21103 .

Véronneau, M. H., Vitaro, F., Brendgen, M., Dishion, T. J., & Tremblay, R. E. (2010). Transactional analysis of the reciprocal links between peer experiences and academic achievement from middle childhood to early adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 46 (4), 773. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019816 .

Volkow, N. D., Wang, G. J., Newcorn, J. H., Kollins, S. H., Wigal, T. L., Telang, F., & Wong, C. (2011). Motivation deficit in ADHD is associated with dysfunction of the dopamine reward pathway. Molecular Psychiatry, 16 (11), 1147–1154. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2010.97 .

Wang, M. T., & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Social support matters: Longitudinal effects of social support on three dimensions of school engagement from middle to high school. Child Development, 83 (3), 877–895. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01745.x .

Wang, M. T., & Sheikh-Khalil, S. (2014). Does parental involvement matter for student achievement and mental health in high school? Child Development, 85 (2), 610–625. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12153 .

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92 (4), 548–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.92.4.548 .

Weiner, B., Frieze, I., Kukla, A., Reed, L., Rest, S., & Rosenbaum, R. M. (1987). Perceiving the causes of success and failure. In E. E. Jones, D. E. Kanouse, H. H. Kelley, R. E. Nisbett, S. Valins, & B. Weiner (Eds.), Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behavior (pp. 95–120). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Weisz, J. P. (1984). Contingency judgments and achievement behavior: Deciding what is controllable and when to try. In J. G. Nicholls (Ed.), The development of achievement motivation (pp. 107–136). Greenwich: JAI Press.

Wentzel, K. R. (1998). Social relationships and motivation in middle school: The role of parents, teachers, and peers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90 (2), 202–209. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.90.2.202 .

Wentzel, K. R. (2000). What is it that I’m trying to achieve? Classroom goals from a content perspective. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25 (1), 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1021 .

Wentzel, K. (2002). Are effective teachers like good parents? Teaching styles and student adjustment in early adolescence. Child Development, 73 (1), 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00406 .

Wentzel, K. R. (2005). Peer relationships, motivation, and academic performance at school. In C. S. Dweck & A. J. Elliot (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 279–296). New York: Guilford Press.

Wentzel, K. R., & Miele, D. B. (Eds.). (2009). Handbook of motivation at school . New York: Routledge.

Wentzel, K. R., & Muenks, K. (2016). Peer influence on students’ motivation, academic achievement, and social behavior. In K. R. Wentzel & G. B. Ramani (Eds.), Handbook of social influences in school contexts: Social-emotional, motivation, and cognitive outcomes (pp. 13–30). New York: Routledge.

Wentzel, K. R., Battle, A., Russell, S. L., & Looney, L. B. (2010). Social supports from teachers and peers as predictors of academic and social motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 35 (3), 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.03.002 .

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. (1992). The development of achievement task values: A theoretical analysis. Developmental Review, 12 (3), 265–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/0273-2297(92)90011-P .

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25 (1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1015 .

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2002). The development of competence beliefs and values from childhood through adolescence. In A. Wigfield & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Development of achievement motivation (pp. 92–120). San Diego: Academic Press.

Wigfield, A., & Tonks, S. (2004). The development of motivation for reading and how it is influenced by CORI. In J. T. Guthrie, A. Wigfield, & K. C. Perencevich (Eds.), Motivating reading comprehension: Concept-oriented reading instruction (pp. 249–272). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Wigfield, A., & Wagner, A. L. (2005). Competence, motivation, and identity development during adolescence. In A. J. Elliot & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 222–239). New York: Guilford Press.

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Yoon, K. S., Harold, R. D., Arbreton, A. J., Freedman-Doan, C., & Blumenfeld, P. C. (1997). Change in children’s competence beliefs and subjective task values across the elementary school years: A 3-year study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89 (3), 451. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.89.3.451 .

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Schiefele, U., Roeser, R. W., & Davis-Kean, P. (2006). Development of achievement motivation . In N. Eisenberg, W. Damon & R.M. Lerner (Vol. 3, pp.933–1002). Hoboken: Wiley. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0315 .

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Schiefele, U., Roeser, R. W., & Davis‐Kean, P. (2007). Development of achievement motivation . Hoboken: Wiley.

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Roeser, R. W., & Schiefele, U. (2008). Development of achievement motivation. In W. Damon, R. M. Lerner, D. Kuhn, R. S. Siegler, & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Child and adolescent development: An advanced course (pp. 406–434). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Wlodkowski, R. J. (2011). Enhancing adult motivation to learn: A comprehensive guide for teaching all adults . San Francisco: Wiley.

Woodworth, R. S. (1918). Dynamic Psychology . New York: Columbia University Press.

Yeung, W. J., Linver, M. R., & Brooks–Gunn, J. (2002). How money matters for young children's development: Parental investment and family processes. Child Development, 73 (6), 1861–1879. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00511 .

Zimmerman, B. J., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1990). Student differences in self-regulated learning: Relating grade, sex, and giftedness to self-efficacy and strategy use. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82 (1), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.82.1.51 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Escuela de Psicología, Universidad de los Andes, Santiago, Chile

Paulina Arango

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Paulina Arango .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Education, Universidad de los Andes, Las Condes, Chile

Pelusa Orellana García

Institute of Literature, Universidad de los Andes, Las Condes, Chile

Paula Baldwin Lind

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Arango, P. (2018). Motivation: Introduction to the Theory, Concepts, and Research. In: Orellana García, P., Baldwin Lind, P. (eds) Reading Achievement and Motivation in Boys and Girls. Literacy Studies, vol 15. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75948-7_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75948-7_1

Published : 03 May 2018

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-75947-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-75948-7

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

10.1 Motivation

Learning objectives.

- Define intrinsic and extrinsic motivation

- Understand that instincts, drive reduction, self-efficacy, and social motives have all been proposed as theories of motivation

- Explain the basic concepts associated with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

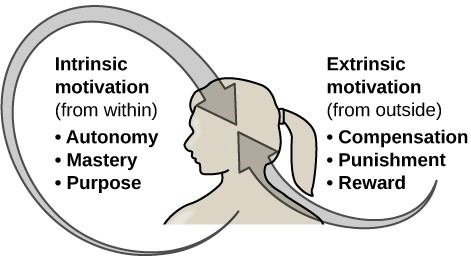

Why do we do the things we do? What motivations underlie our behaviors? Motivation describes the wants or needs that direct behavior toward a goal. In addition to biological motives, motivations can be intrinsic (arising from internal factors) or extrinsic (arising from external factors) ( Figure 10.2 ). Intrinsically motivated behaviors are performed because of the sense of personal satisfaction that they bring, while extrinsically motivated behaviors are performed in order to receive something from others.

Think about why you are currently in college. Are you here because you enjoy learning and want to pursue an education to make yourself a more well-rounded individual? If so, then you are intrinsically motivated. However, if you are here because you want to get a college degree to make yourself more marketable for a high-paying career or to satisfy the demands of your parents, then your motivation is more extrinsic in nature.

In reality, our motivations are often a mix of both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, but the nature of the mix of these factors might change over time (often in ways that seem counter-intuitive). There is an old adage: “Choose a job that you love, and you will never have to work a day in your life,” meaning that if you enjoy your occupation, work doesn’t seem like . . . well, work. Some research suggests that this isn’t necessarily the case (Daniel & Esser, 1980; Deci, 1972; Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999). According to this research, receiving some sort of extrinsic reinforcement (i.e., getting paid) for engaging in behaviors that we enjoy leads to those behaviors being thought of as work no longer providing that same enjoyment. As a result, we might spend less time engaging in these reclassified behaviors in the absence of any extrinsic reinforcement. For example, Odessa loves baking, so in her free time, she bakes for fun. Oftentimes, after stocking shelves at her grocery store job, she often whips up pastries in the evenings because she enjoys baking. When a coworker in the store’s bakery department leaves his job, Odessa applies for his position and gets transferred to the bakery department. Although she enjoys what she does in her new job, after a few months, she no longer has much desire to concoct tasty treats in her free time. Baking has become work in a way that changes her motivation to do it ( Figure 10.3 ). What Odessa has experienced is called the overjustification effect—intrinsic motivation is diminished when extrinsic motivation is given. This can lead to extinguishing the intrinsic motivation and creating a dependence on extrinsic rewards for continued performance (Deci et al., 1999).

Other studies suggest that intrinsic motivation may not be so vulnerable to the effects of extrinsic reinforcements, and in fact, reinforcements such as verbal praise might actually increase intrinsic motivation (Arnold, 1976; Cameron & Pierce, 1994). In that case, Odessa’s motivation to bake in her free time might remain high if, for example, customers regularly compliment her baking or cake decorating skills.

These apparent discrepancies in the researchers’ findings may be understood by considering several factors. For one, physical reinforcement (such as money) and verbal reinforcement (such as praise) may affect an individual in very different ways. In fact, tangible rewards (i.e., money) tend to have more negative effects on intrinsic motivation than do intangible rewards (i.e., praise). Furthermore, the expectation of the extrinsic motivator by an individual is crucial: If the person expects to receive an extrinsic reward, then intrinsic motivation for the task tends to be reduced. If, however, there is no such expectation, and the extrinsic motivation is presented as a surprise, then intrinsic motivation for the task tends to persist (Deci et al., 1999).

In educational settings, students are more likely to experience intrinsic motivation to learn when they feel a sense of belonging and respect in the classroom. This internalization can be enhanced if the evaluative aspects of the classroom are de-emphasized and if students feel that they exercise some control over the learning environment. Furthermore, providing students with activities that are challenging, yet doable, along with a rationale for engaging in various learning activities can enhance intrinsic motivation for those tasks (Niemiec & Ryan, 2009). Consider Hakim, a first-year law student with two courses this semester: Family Law and Criminal Law. The Family Law professor has a rather intimidating classroom: He likes to put students on the spot with tough questions, which often leaves students feeling belittled or embarrassed. Grades are based exclusively on quizzes and exams, and the instructor posts results of each test on the classroom door. In contrast, the Criminal Law professor facilitates classroom discussions and respectful debates in small groups. The majority of the course grade is not exam-based, but centers on a student-designed research project on a crime issue of the student’s choice. Research suggests that Hakim will be less intrinsically motivated in his Family Law course, where students are intimidated in the classroom setting, and there is an emphasis on teacher-driven evaluations. Hakim is likely to experience a higher level of intrinsic motivation in his Criminal Law course, where the class setting encourages inclusive collaboration and a respect for ideas, and where students have more influence over their learning activities.

Theories About Motivation

William James (1842–1910) was an important contributor to early research into motivation, and he is often referred to as the father of psychology in the United States. James theorized that behavior was driven by a number of instincts, which aid survival ( Figure 10.4 ). From a biological perspective, an instinct is a species-specific pattern of behavior that is not learned. There was, however, considerable controversy among James and his contemporaries over the exact definition of instinct. James proposed several dozen special human instincts, but many of his contemporaries had their own lists that differed. A mother’s protection of her baby, the urge to lick sugar, and hunting prey were among the human behaviors proposed as true instincts during James’s era. This view—that human behavior is driven by instincts—received a fair amount of criticism because of the undeniable role of learning in shaping all sorts of human behavior. In fact, as early as the 1900s, some instinctive behaviors were experimentally demonstrated to result from associative learning (recall when you learned about Watson’s conditioning of fear response in “Little Albert”) (Faris, 1921).

Another early theory of motivation proposed that the maintenance of homeostasis is particularly important in directing behavior. You may recall from your earlier reading that homeostasis is the tendency to maintain a balance, or optimal level, within a biological system. In a body system, a control center (which is often part of the brain) receives input from receptors (which are often complexes of neurons). The control center directs effectors (which may be other neurons) to correct any imbalance detected by the control center.

According to the drive theory of motivation, deviations from homeostasis create physiological needs. These needs result in psychological drive states that direct behavior to meet the need and, ultimately, bring the system back to homeostasis. For example, if it’s been a while since you ate, your blood sugar levels will drop below normal. This low blood sugar will induce a physiological need and a corresponding drive state (i.e., hunger) that will direct you to seek out and consume food ( Figure 10.5 ). Eating will eliminate the hunger, and, ultimately, your blood sugar levels will return to normal. Interestingly, drive theory also emphasizes the role that habits play in the type of behavioral response in which we engage. A habit is a pattern of behavior in which we regularly engage. Once we have engaged in a behavior that successfully reduces a drive, we are more likely to engage in that behavior whenever faced with that drive in the future (Graham & Weiner, 1996).

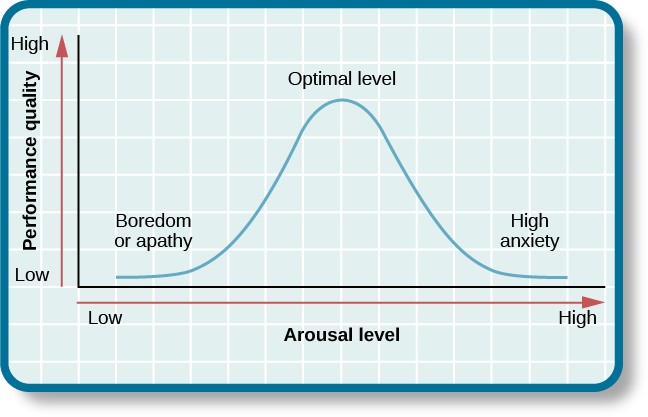

Extensions of drive theory take into account levels of arousal as potential motivators. As you recall from your study of learning, these theories assert that there is an optimal level of arousal that we all try to maintain ( Figure 10.6 ). If we are underaroused, we become bored and will seek out some sort of stimulation. On the other hand, if we are overaroused, we will engage in behaviors to reduce our arousal (Berlyne, 1960). Most students have experienced this need to maintain optimal levels of arousal over the course of their academic career. Think about how much stress students experience toward the end of spring semester. They feel overwhelmed with seemingly endless exams, papers, and major assignments that must be completed on time. They probably yearn for the rest and relaxation that awaits them over the extended summer break. However, once they finish the semester, it doesn’t take too long before they begin to feel bored. Generally, by the time the next semester is beginning in the fall, many students are quite happy to return to school. This is an example of how arousal theory works.

So what is the optimal level of arousal? What level leads to the best performance? Research shows that moderate arousal is generally best; when arousal is very high or very low, performance tends to suffer (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908). Think of your arousal level regarding taking an exam for this class. If your level is very low, such as boredom and apathy, your performance will likely suffer. Similarly, a very high level, such as extreme anxiety, can be paralyzing and hinder performance. Consider the example of a softball team facing a tournament. They are favored to win their first game by a large margin, so they go into the game with a lower level of arousal and get beat by a less skilled team.

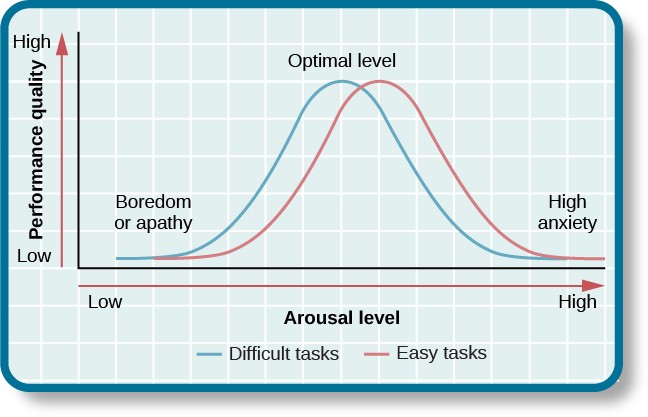

But optimal arousal level is more complex than a simple answer that the middle level is always best. Researchers Robert Yerkes (pronounced “Yerk-EES”) and John Dodson discovered that the optimal arousal level depends on the complexity and difficulty of the task to be performed ( Figure 10.7 ). This relationship is known as Yerkes-Dodson law , which holds that a simple task is performed best when arousal levels are relatively high and complex tasks are best performed when arousal levels are lower.

Self-efficacy and Social Motives

Self-efficacy is an individual’s belief in her own capability to complete a task, which may include a previous successful completion of the exact task or a similar task. Albert Bandura (1994) theorized that an individual’s sense of self-efficacy plays a pivotal role in motivating behavior. Bandura argues that motivation derives from expectations that we have about the consequences of our behaviors, and ultimately, it is the appreciation of our capacity to engage in a given behavior that will determine what we do and the future goals that we set for ourselves. For example, if you have a sincere belief in your ability to achieve at the highest level, you are more likely to take on challenging tasks and to not let setbacks dissuade you from seeing the task through to the end.

A number of theorists have focused their research on understanding social motives (McAdams & Constantian, 1983; McClelland & Liberman, 1949; Murray et al., 1938). Among the motives they describe are needs for achievement, affiliation, and intimacy. It is the need for achievement that drives accomplishment and performance. The need for affiliation encourages positive interactions with others, and the need for intimacy causes us to seek deep, meaningful relationships. Henry Murray et al. (1938) categorized these needs into domains. For example, the need for achievement and recognition falls under the domain of ambition. Dominance and aggression were recognized as needs under the domain of human power, and play was a recognized need in the domain of interpersonal affection.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

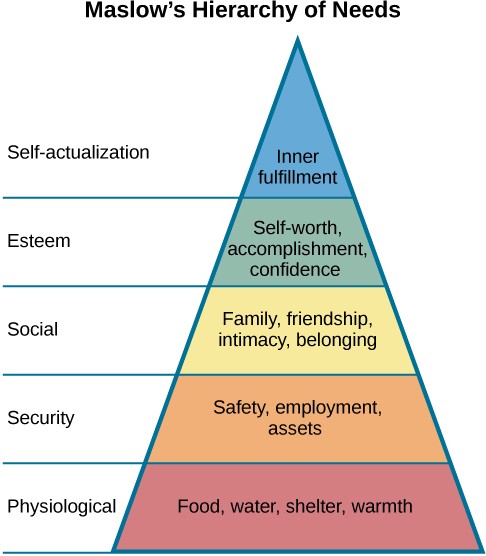

While the theories of motivation described earlier relate to basic biological drives, individual characteristics, or social contexts, Abraham Maslow (1943) proposed a hierarchy of needs that spans the spectrum of motives ranging from the biological to the individual to the social. These needs are often depicted as a pyramid ( Figure 10.8 ).

At the base of the pyramid are all of the physiological needs that are necessary for survival. These are followed by basic needs for security and safety, the need to be loved and to have a sense of belonging, and the need to have self-worth and confidence. The top tier of the pyramid is self-actualization, which is a need that essentially equates to achieving one’s full potential, and it can only be realized when needs lower on the pyramid have been met. To Maslow and humanistic theorists, self-actualization reflects the humanistic emphasis on positive aspects of human nature. Maslow suggested that this is an ongoing, life-long process and that only a small percentage of people actually achieve a self-actualized state (Francis & Kritsonis, 2006; Maslow, 1943).

According to Maslow (1943), one must satisfy lower-level needs before addressing those needs that occur higher in the pyramid. So, for example, if someone is struggling to find enough food to meet his nutritional requirements, it is quite unlikely that he would spend an inordinate amount of time thinking about whether others viewed him as a good person or not. Instead, all of his energies would be geared toward finding something to eat. However, it should be pointed out that Maslow’s theory has been criticized for its subjective nature and its inability to account for phenomena that occur in the real world (Leonard, 1982). Other research has more recently addressed that late in life, Maslow proposed a self-transcendence level above self-actualization—to represent striving for meaning and purpose beyond the concerns of oneself (Koltko-Rivera, 2006). For example, people sometimes make self-sacrifices in order to make a political statement or in an attempt to improve the conditions of others. Mohandas K. Gandhi, a world-renowned advocate for independence through nonviolent protest, on several occasions went on hunger strikes to protest a particular situation. People may starve themselves or otherwise put themselves in danger displaying higher-level motives beyond their own needs.

Link to Learning

Check out this interactive exercise that illustrates some of the important concepts in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Rose M. Spielman, Kathryn Dumper, William Jenkins, Arlene Lacombe, Marilyn Lovett, Marion Perlmutter

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Psychology

- Publication date: Dec 8, 2014

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology/pages/10-1-motivation

© Feb 9, 2022 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Emotion and Motivation

Learning objectives.

- Illustrate intrinsic and extrinsic motivation

Why do we do the things we do? What motivations underlie our behaviors? Motivation describes the wants or needs that direct behavior toward a goal. In addition to biological motives, motivations can be intrinsic (arising from internal factors) or extrinsic (arising from external factors) (Figure 1). Intrinsically motivated behaviors are performed because of the sense of personal satisfaction that they bring, while extrinsically motivated behaviors are performed in order to receive something from others.

Figure 1 . Intrinsic motivation comes from within the individual, while extrinsic motivation comes from outside the individual.

Think about why you are currently in college. Are you here because you enjoy learning and want to pursue an education to make yourself a more well-rounded individual? If so, then you are intrinsically motivated. However, if you are here because you want to get a college degree to make yourself more marketable for a high-paying career or to satisfy the demands of your parents, then your motivation is more extrinsic in nature.

In reality, our motivations are often a mix of both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, but the nature of the mix of these factors might change over time (often in ways that seem counter-intuitive). There is an old adage: “Choose a job that you love, and you will never have to work a day in your life,” meaning that if you enjoy your occupation, work doesn’t seem like . . . well, work. Some research suggests that this isn’t necessarily the case (Daniel & Esser, 1980; Deci, 1972; Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999). According to this research, receiving some sort of extrinsic reinforcement (i.e., getting paid) for engaging in behaviors that we enjoy leads to those behaviors being thought of as work no longer providing that same enjoyment. As a result, we might spend less time engaging in these reclassified behaviors in the absence of any extrinsic reinforcement. For example, Odessa loves baking, so in her free time, she bakes for fun. Oftentimes, after stocking shelves at her grocery store job, she whips up pastries in the evenings because she enjoys baking. When a coworker in the store’s bakery department leaves his job, Odessa applies for his position and gets transferred to the bakery department. Although she enjoys what she does in her new job, after a few months, she no longer has much desire to concoct tasty treats in her free time. Baking has become work in a way that changes her motivation to do it (Figure 2). What Odessa has experienced is called the overjustification effect—intrinsic motivation is diminished when extrinsic motivation is given. This can lead to extinguishing the intrinsic motivation and creating a dependence on extrinsic rewards for continued performance (Deci et al., 1999).

Figure 2 . Research suggests that when something we love to do, like icing cakes, becomes our job, our intrinsic and extrinsic motivations to do it may change. (credit: Agustín Ruiz)

Other studies suggest that intrinsic motivation may not be so vulnerable to the effects of extrinsic reinforcements, and in fact, reinforcements such as verbal praise might actually increase intrinsic motivation (Arnold, 1976; Cameron & Pierce, 1994). In that case, Odessa’s motivation to bake in her free time might remain high if, for example, customers regularly compliment her baking or cake decorating skills.

These apparent discrepancies in the researchers’ findings may be understood by considering several factors. For one, physical reinforcement (such as money) and verbal reinforcement (such as praise) may affect an individual in very different ways. In fact, tangible rewards (i.e., money) tend to have more negative effects on intrinsic motivation than do intangible rewards (i.e., praise). Furthermore, the expectation of the extrinsic motivator by an individual is crucial: If the person expects to receive an extrinsic reward, then intrinsic motivation for the task tends to be reduced. If, however, there is no such expectation, and the extrinsic motivation is presented as a surprise, then intrinsic motivation for the task tends to persist (Deci et al., 1999).

In addition, culture may influence motivation. For example, in collectivistic cultures, it is common to do things for your family members because the emphasis is on the group and what is best for the entire group, rather than what is best for any one individual (Nisbett, Peng, Choi, & Norenzayan, 2001). This focus on others provides a broader perspective that takes into account both situational and cultural influences on behavior; thus, a more nuanced explanation of the causes of others’ behavior becomes more likely. (You will learn more about collectivistic and individualistic cultures when you learn about social psychology.)

In educational settings, students are more likely to experience intrinsic motivation to learn when they feel a sense of belonging and respect in the classroom. This internalization can be enhanced if the evaluative aspects of the classroom are de-emphasized and if students feel that they exercise some control over the learning environment. Furthermore, providing students with activities that are challenging, yet doable, along with a rationale for engaging in various learning activities can enhance intrinsic motivation for those tasks (Niemiec & Ryan, 2009). Consider Hakim, a first-year law student with two courses this semester: Family Law and Criminal Law. The Family Law professor has a rather intimidating classroom: He likes to put students on the spot with tough questions, which often leaves students feeling belittled or embarrassed. Grades are based exclusively on quizzes and exams, and the instructor posts results of each test on the classroom door. In contrast, the Criminal Law professor facilitates classroom discussions and respectful debates in small groups. The majority of the course grade is not exam-based, but centers on a student-designed research project on a crime issue of the student’s choice. Research suggests that Hakim will be less intrinsically motivated in his Family Law course, where students are intimidated in the classroom setting, and there is an emphasis on teacher-driven evaluations. Hakim is likely to experience a higher level of intrinsic motivation in his Criminal Law course, where the class setting encourages inclusive collaboration and a respect for ideas, and where students have more influence over their learning activities.

Contribute!

Improve this page Learn More

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Motivation. Authored by : OpenStax College. Located at : https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/10-1-motivation . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 10: Emotion and Motivation

Introduction.

What makes us behave as we do? What drives us to eat? What drives us toward sex? Is there a biological basis to explain the feelings we experience? How universal are emotions?

In this chapter, we will explore issues relating to both motivation and emotion. We will begin with a discussion of several theories that have been proposed to explain motivation and why we engage in a given behavior. You will learn about the physiological needs that drive some human behaviors, as well as the importance of our social experiences in influencing our actions.

Next, we will consider both eating and having sex as examples of motivated behaviors. What are the physiological mechanisms of hunger and satiety? What understanding do scientists have of why obesity occurs, and what treatments exist for obesity and eating disorders? How has research into human sex and sexuality evolved over the past century? How do psychologists understand and study the human experience of sexual orientation and gender identity? These questions—and more—will be explored.

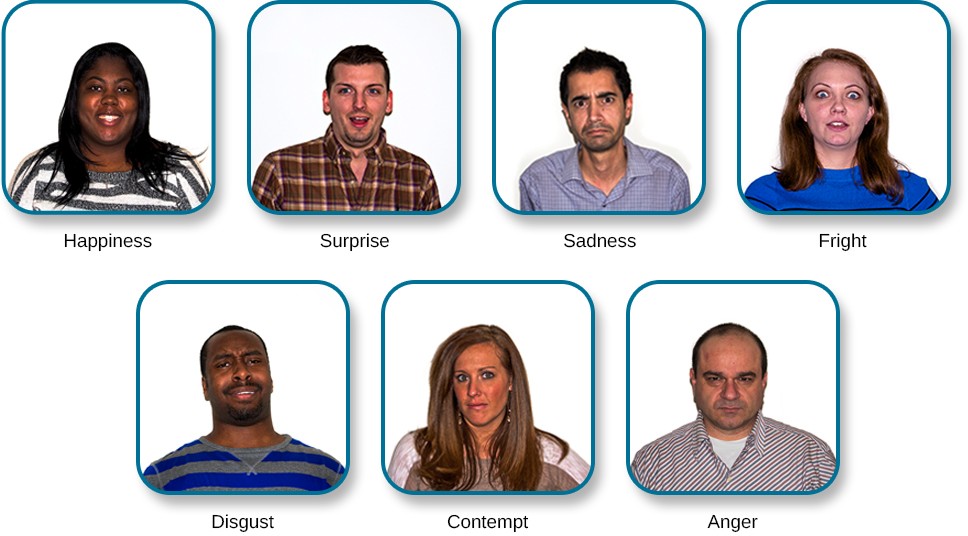

This chapter will close with a discussion of emotion. You will learn about several theories that have been proposed to explain how emotion occurs, the biological underpinnings of emotion, and the universality of emotions.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define intrinsic and extrinsic motivation

- Understand that instincts, drive reduction, self-efficacy, and social motives have all been proposed as theories of motivation

- Explain the basic concepts associated with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

Why do we do the things we do? What motivations underlie our behaviors? Motivation describes the wants or needs that direct behavior toward a goal. In addition to biological motives, motivations can be intrinsic (arising from internal factors) or extrinsic (arising from external factors) ( Figure 10.2 ). Intrinsically motivated behaviors are performed because of the sense of personal satisfaction that they bring, while extrinsically motivated behaviors are performed in order to receive something from others.

Figure 10.2 Intrinsic motivation comes from within the individual, while extrinsic motivation comes from outside the individual.

Think about why you are currently in college. Are you here because you enjoy learning and want to pursue an education to make yourself a more well-rounded individual? If so, then you are intrinsically motivated. However, if you are here because you want to get a college degree to make yourself more marketable for a high-paying career or to satisfy the demands of your parents, then your motivation is more extrinsic in nature.

In reality, our motivations are often a mix of both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, but the nature of the mix of these factors might change over time (often in ways that seem counter-intuitive). There is an old adage: “Choose a job that you love, and you will never have to work a day in your life,” meaning that if you enjoy your occupation, work doesn’t seem like . . . well, work. Some research suggests that this isn’t necessarily the case (Daniel & Esser, 1980; Deci, 1972; Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999). According to this research, receiving some sort of extrinsic reinforcement (i.e., getting paid) for engaging in behaviors that we enjoy leads to those behaviors being thought of as work no longer providing that same enjoyment. As a result, we might spend less time engaging in these reclassified behaviors in the absence of any extrinsic reinforcement. For example, Odessa loves baking, so in her free time, she bakes for fun. Oftentimes, after stocking shelves at her grocery store job, she often whips up pastries in the evenings because she enjoys baking. When a coworker in the store’s bakery department leaves his job, Odessa applies for his position and gets transferred to the bakery department. Although she enjoys what she does in her new job, after a few months, she no longer has much desire to concoct tasty treats in her free time. Baking has become work in a way that changes her motivation to do it ( Figure 10.3 ). What Odessa has experienced is called the overjustification effect—intrinsic motivation is diminished when extrinsic motivation is given. This can lead to extinguishing the intrinsic motivation and creating a dependence on extrinsic rewards for continued performance (Deci et al., 1999).

Figure 10.3 Research suggests that when something we love to do, like icing cakes, becomes our job, our intrinsic and extrinsic motivations to do it may change. (credit: Agustín Ruiz)

Other studies suggest that intrinsic motivation may not be so vulnerable to the effects of extrinsic reinforcements, and in fact, reinforcements such as verbal praise might actually increase intrinsic motivation (Arnold, 1976; Cameron & Pierce, 1994). In that case, Odessa’s motivation to bake in her free time might remain high if, for example, customers regularly compliment her baking or cake decorating skills.

These apparent discrepancies in the researchers’ findings may be understood by considering several factors. For one, physical reinforcement (such as money) and verbal reinforcement (such as praise) may affect an individual in very different ways. In fact, tangible rewards (i.e., money) tend to have more negative effects on intrinsic motivation than do intangible rewards (i.e., praise). Furthermore, the expectation of the extrinsic motivator by an individual is crucial: If the person expects to receive an extrinsic reward, then intrinsic motivation for the task tends to be reduced. If, however, there is no such expectation, and the extrinsic motivation is presented as a surprise, then intrinsic motivation for the task tends to persist (Deci et al., 1999).

In educational settings, students are more likely to experience intrinsic motivation to learn when they feel a sense of belonging and respect in the classroom. This internalization can be enhanced if the evaluative aspects of the classroom are de-emphasized and if students feel that they exercise some control over the learning environment. Furthermore, providing students with activities that are challenging, yet doable, along with a rationale for engaging in various learning activities can enhance intrinsic motivation for those tasks (Niemiec & Ryan, 2009). Consider Hakim, a first-year law student with two courses this semester: Family Law and Criminal Law. The Family Law professor has a rather intimidating classroom: He likes to put students on the spot with tough questions, which often leaves students feeling belittled or embarrassed. Grades are based exclusively on quizzes and exams, and the instructor posts results of each test on the classroom door. In contrast, the Criminal Law professor facilitates classroom discussions and respectful debates in small groups. The majority of the course grade is not exam-based, but centers on a student-designed research project on a crime issue of the student’s choice. Research suggests that Hakim will be less intrinsically motivated in his Family Law course, where students are intimidated in the classroom setting, and there is an emphasis on teacher-driven evaluations. Hakim is likely to experience a higher level of intrinsic motivation in his Criminal Law course, where the class setting encourages inclusive collaboration and a respect for ideas, and where students have more influence over their learning activities.

THEORIES ABOUT MOTIVATION

William James (1842–1910) was an important contributor to early research into motivation, and he is often referred to as the father of psychology in the United States. James theorized that behavior was driven by a number of instincts, which aid survival ( Figure 10.4 ). From a biological perspective, an instinct is a species-specific pattern of behavior that is not learned. There was, however, considerable controversy among James and his contemporaries over the exact definition of instinct. James proposed several dozen special human instincts, but many of his contemporaries had their own lists that differed.

A mother’s protection of her baby, the urge to lick sugar, and hunting prey were among the human behaviors proposed as true instincts during James’s era. This view—that human behavior is driven by instincts—received a fair amount of criticism because of the undeniable role of learning in shaping all sorts of human behavior. In fact, as early as the 1900s, some instinctive behaviors were experimentally demonstrated to result from associative learning (recall when you learned about Watson’s conditioning of fear response in “Little Albert”) (Faris, 1921).

Figure 10.4 (a) William James proposed the instinct theory of motivation, asserting that behavior is driven by instincts. (b) In humans, instincts may include behaviors such as an infant’s rooting for a nipple and sucking. (credit b: modification of work by “Mothering Touch”/Flickr)

Another early theory of motivation proposed that the maintenance of homeostasis is particularly important in directing behavior. You may recall from your earlier reading that homeostasis is the tendency to maintain a balance, or optimal level, within a biological system. In a body system, a control center (which is often part of the brain) receives input from receptors (which are often complexes of neurons). The control center directs effectors (which may be other neurons) to correct any imbalance detected by the control center.

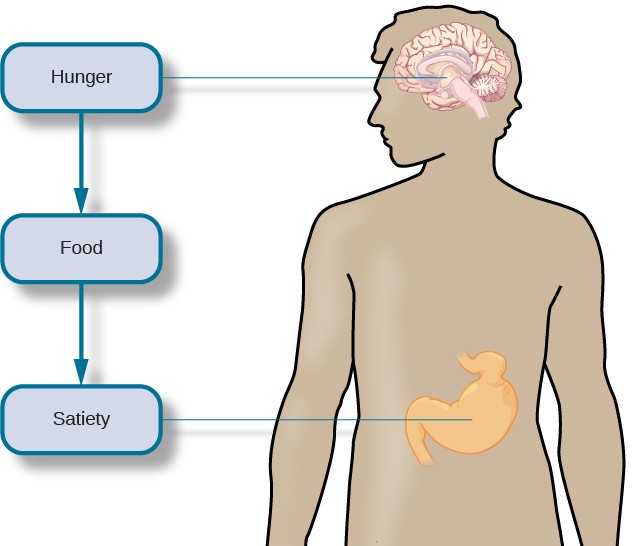

According to the drive theory of motivation, deviations from homeostasis create physiological needs. These needs result in psychological drive states that direct behavior to meet the need and, ultimately, bring the system back to homeostasis. For example, if it’s been a while since you ate, your blood sugar levels will drop below normal. This low blood sugar will induce a physiological need and a corresponding drive state (i.e., hunger) that will direct you to seek out and consume food ( Figure 10.5 ). Eating will eliminate the hunger, and, ultimately, your blood sugar levels will return to normal. Interestingly, drive theory also emphasizes the role that habits play in the type of behavioral response in which we engage. A habit is a pattern of behavior in which we regularly engage. Once we have engaged in a behavior that successfully reduces a drive, we are more likely to engage in that behavior whenever faced with that drive in the future (Graham & Weiner, 1996).

Figure 10.5 Hunger and subsequent eating are the result of complex physiological processes that maintain homeostasis. (credit “left”: modification of work by “Gracie and Viv”/Flickr; credit “center”: modification of work by Steven Depolo; credit “right”: modification of work by Monica Renata)

Extensions of drive theory take into account levels of arousal as potential motivators. As you recall from your study of learning, these theories assert that there is an optimal level of arousal that we all try to maintain ( Figure 10.6 ). If we are underaroused, we become bored and will seek out some sort of stimulation. On the other hand, if we are overaroused, we will engage in behaviors to reduce our arousal (Berlyne, 1960). Most students have experienced this need to maintain optimal levels of arousal over the course of their academic career. Think about how much stress students experience toward the end of spring semester. They feel overwhelmed with seemingly endless exams, papers, and major assignments that must be completed on time. They probably yearn for the rest and relaxation that awaits them over the extended summer break. However, once they finish the semester, it doesn’t take too long before they begin to feel bored. Generally, by the time the next semester is beginning in the fall, many students are quite happy to return to school. This is an example of how arousal theory works.

Figure 10.6 The concept of optimal arousal in relation to performance on a task is depicted here. Performance is maximized at the optimal level of arousal, and it tapers off during under- and overarousal.

So what is the optimal level of arousal? What level leads to the best performance? Research shows that moderate arousal is generally best; when arousal is very high or very low, performance tends to suffer (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908). Think of your arousal level regarding taking an exam for this class. If your level is very low, such as boredom and apathy, your performance will likely suffer. Similarly, a very high level, such as extreme anxiety, can be paralyzing and hinder performance. Consider the example of a softball team facing a tournament. They are favored to win their first game by a large margin, so they go into the game with a lower level of arousal and get beat by a less skilled team.

But optimal arousal level is more complex than a simple answer that the middle level is always best. Researchers Robert Yerkes (pronounced “Yerk-EES”) and John Dodson discovered that the optimal

arousal level depends on the complexity and difficulty of the task to be performed ( Figure 10.7 ). This relationship is known as Yerkes-Dodson law , which holds that a simple task is performed best when arousal levels are relatively high and complex tasks are best performed when arousal levels are lower.

Figure 10.7 Task performance is best when arousal levels are in a middle range, with difficult tasks best performed under lower levels of arousal and simple tasks best performed under higher levels of arousal.

Self-efficacy and Social Motives

Self-efficacy is an individual’s belief in her own capability to complete a task, which may include a previous successful completion of the exact task or a similar task. Albert Bandura (1994) theorized that an individual’s sense of self-efficacy plays a pivotal role in motivating behavior. Bandura argues that motivation derives from expectations that we have about the consequences of our behaviors, and ultimately, it is the appreciation of our capacity to engage in a given behavior that will determine what we do and the future goals that we set for ourselves. For example, if you have a sincere belief in your ability to achieve at the highest level, you are more likely to take on challenging tasks and to not let setbacks dissuade you from seeing the task through to the end.

A number of theorists have focused their research on understanding social motives (McAdams & Constantian, 1983; McClelland & Liberman, 1949; Murray et al., 1938). Among the motives they describe are needs for achievement, affiliation, and intimacy. It is the need for achievement that drives accomplishment and performance. The need for affiliation encourages positive interactions with others, and the need for intimacy causes us to seek deep, meaningful relationships. Henry Murray et al. (1938) categorized these needs into domains. For example, the need for achievement and recognition falls under the domain of ambition. Dominance and aggression were recognized as needs under the domain of human power, and play was a recognized need in the domain of interpersonal affection.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

While the theories of motivation described earlier relate to basic biological drives, individual characteristics, or social contexts, Abraham Maslow (1943) proposed a hierarchy of needs that spans the spectrum of motives ranging from the biological to the individual to the social. These needs are often depicted as a pyramid ( Figure 10.8 ).

Figure 10.8 Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is illustrated here. In some versions of the pyramid, cognitive and aesthetic needs are also included between esteem and self-actualization. Others include another tier at the top of the pyramid for self-transcendence.

At the base of the pyramid are all of the physiological needs that are necessary for survival. These are followed by basic needs for security and safety, the need to be loved and to have a sense of belonging, and the need to have self-worth and confidence. The top tier of the pyramid is self-actualization, which is a need that essentially equates to achieving one’s full potential, and it can only be realized when needs lower on the pyramid have been met. To Maslow and humanistic theorists, self-actualization reflects the humanistic emphasis on positive aspects of human nature. Maslow suggested that this is an ongoing, life- long process and that only a small percentage of people actually achieve a self-actualized state (Francis & Kritsonis, 2006; Maslow, 1943).

According to Maslow (1943), one must satisfy lower-level needs before addressing those needs that occur higher in the pyramid. So, for example, if someone is struggling to find enough food to meet his nutritional requirements, it is quite unlikely that he would spend an inordinate amount of time thinking about whether others viewed him as a good person or not. Instead, all of his energies would be geared toward finding something to eat. However, it should be pointed out that Maslow’s theory has been criticized for its subjective nature and its inability to account for phenomena that occur in the real world (Leonard, 1982). Other research has more recently addressed that late in life, Maslow proposed a self-transcendence level above self-actualization—to represent striving for meaning and purpose beyond the concerns of oneself (Koltko-Rivera, 2006). For example, people sometimes make self-sacrifices in order to make a political statement or in an attempt to improve the conditions of others. Mohandas K. Gandhi, a world- renowned advocate for independence through nonviolent protest, on several occasions went on hunger strikes to protest a particular situation. People may starve themselves or otherwise put themselves in danger displaying higher-level motives beyond their own needs.

Hunger and Eating

- Describe how hunger and eating are regulated

- Differentiate between levels of overweight and obesity and the associated health consequences

- Explain the health consequences resulting from anorexia and bulimia nervosa

Eating is essential for survival, and it is no surprise that a drive like hunger exists to ensure that we seek out sustenance. While this chapter will focus primarily on the physiological mechanisms that regulate hunger and eating, powerful social, cultural, and economic influences also play important roles. This section will explain the regulation of hunger, eating, and body weight, and we will discuss the adverse consequences of disordered eating.

PHYSIOLOGICAL MECHANISMS

There are a number of physiological mechanisms that serve as the basis for hunger. When our stomachs are empty, they contract, causing both hunger pangs and the secretion of chemical messages that travel to the brain to serve as a signal to initiate feeding behavior. When our blood glucose levels drop, the pancreas and liver generate a number of chemical signals that induce hunger (Konturek et al., 2003; Novin, Robinson, Culbreth, & Tordoff, 1985) and thus initiate feeding behavior.

For most people, once they have eaten, they feel satiation , or fullness and satisfaction, and their eating behavior stops. Like the initiation of eating, satiation is also regulated by several physiological mechanisms. As blood glucose levels increase, the pancreas and liver send signals to shut off hunger and eating (Drazen & Woods, 2003; Druce, Small, & Bloom, 2004; Greary, 1990). The food’s passage through the gastrointestinal tract also provides important satiety signals to the brain (Woods, 2004), and fat cells release leptin , a satiety hormone.

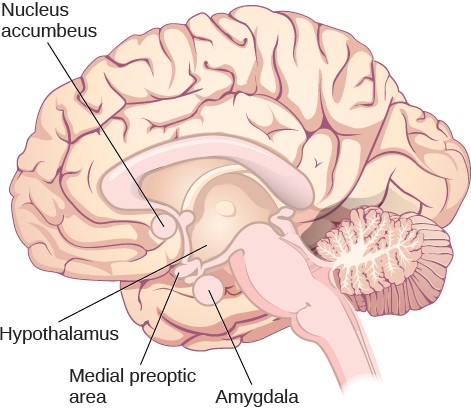

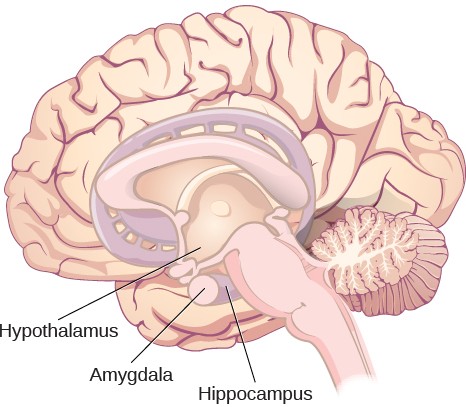

The various hunger and satiety signals that are involved in the regulation of eating are integrated in the brain. Research suggests that several areas of the hypothalamus and hindbrain are especially important sites where this integration occurs (Ahima & Antwi, 2008; Woods & D’Alessio, 2008). Ultimately, activity in the brain determines whether or not we engage in feeding behavior ( Figure 10.9 ).

Figure 10.9 Hunger and eating are regulated by a complex interplay of hunger and satiety signals that are integrated in the brain.

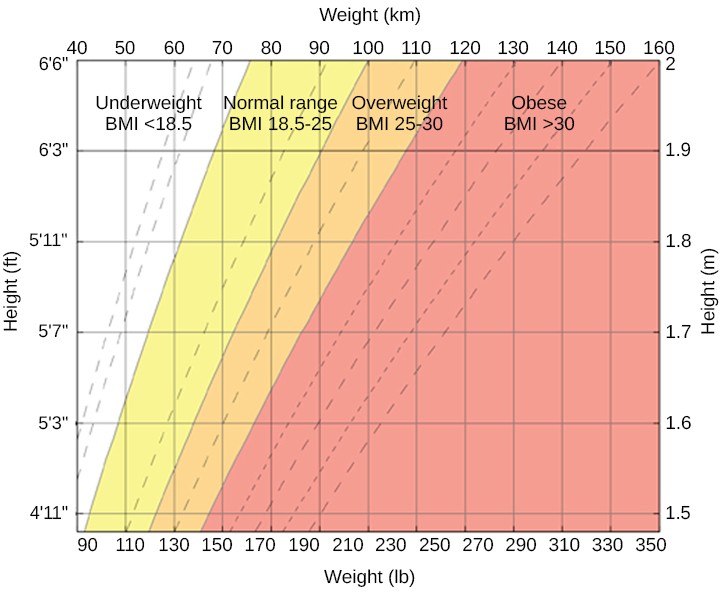

METABOLISM AND BODY WEIGHT

Our body weight is affected by a number of factors, including gene-environment interactions, and the number of calories we consume versus the number of calories we burn in daily activity. If our caloric intake exceeds our caloric use, our bodies store excess energy in the form of fat. If we consume fewer calories than we burn off, then stored fat will be converted to energy. Our energy expenditure is obviously affected by our levels of activity, but our body’s metabolic rate also comes into play. A person’s metabolic rate is the amount of energy that is expended in a given period of time, and there is tremendous individual variability in our metabolic rates. People with high rates of metabolism are able to burn off calories more easily than those with lower rates of metabolism.