Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- April 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 4 CURRENT ISSUE pp.255-346

- March 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 3 pp.171-254

- February 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 2 pp.83-170

- January 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 1 pp.1-82

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Personalizing the Treatment of Substance Use Disorders

- Nora D. Volkow , M.D.

Search for more papers by this author

The opioid crisis in the United States has brought drug addiction to the forefront of the public mind and to the attention of health care personnel, organizations, and agencies. The epidemic of overdoses, beginning with those caused by prescription opioid analgesics and then broadening to include heroin and fentanyl and its analogs, has prompted major initiatives in local communities, states, and at the federal level to treat addiction and pain more effectively. The crisis has highlighted an insulated addiction treatment system that for decades was segregated from the rest of health care because of stigma associated with addiction and, by extension, the medications used to treat it. Stigmatizing attitudes have been slow to erode, but the moralizing and punitive viewpoints of the past are gradually giving way to a medical and even a cultural consensus that addiction is a chronic disorder of the brain, one that is strongly influenced by social factors, and one that is also treatable.

Parallel research in animal models and brain-imaging studies in individuals with substance use disorders has given us an increasingly precise picture of their neurobiology, including molecular and synaptic changes and the neuronal circuits involved, along with the consequences of their disruption. Most people are exposed to addictive substances at some point in their lives, including alcohol and nicotine, and many use these substances recreationally without developing addiction. Similarly, many patients who use opioids to treat their pain don’t develop addiction. But in a subset of individuals who are vulnerable because of genetics, age, and other variables, repeated exposure to addictive drugs diminishes the capacity of basal ganglia circuits to respond to natural reward and to motivate the behaviors needed for survival and well-being, while enhancing the sensitivity of stress and emotional circuits, including those from the extended amygdala, triggering anxiety and dysphoria when not taking the drug and weakening prefrontal executive-control circuitry necessary for self-regulation ( 1 ).

These changes, along with learning mechanisms that tie expectation of reward to drug cues, intensify each other in a kind of perfect storm: Inability to feel reward from non-drug activities, including social interactions, takes away the enjoyment of life and increases social isolation. Intense symptoms of withdrawal drive a search for temporary relief, and constant reminders of the drug in the environment contribute to persistent craving and preoccupation with obtaining the drug. Weakened capacity to resist the urge to take the drug or follow through on resolutions to quit leads, very often, to relapse and the accompanying regret or shame at having failed. Further increasing relapse risk are the frequently associated symptoms of depression, anxiety, and impaired sleep.

Until recently, the development of treatments for addiction was aimed at bringing about cessation of drug consumption (abstinence), which was the outcome required for U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of medications for substance use disorders. However, our current understanding of the mechanistic processes underlying addiction identifies a much broader set of clinically beneficial outcomes. For example, reduction of use in a person who uses heroin could decrease his or her risk of overdose, and improvements in sleep, depression, or executive function could also reduce relapse risk. In addition, technological advances and our growing understanding of the underlying neurobiology have given us the opportunity to target discrete neurobiological processes and personalize interventions to the unique deficits in a given individual and across the course of an individual’s disorder. A dimensional, personalized, and dynamic approach to treating substance use disorders could draw from medication use, neuromodulation techniques, behavioral approaches, and their combinations as the individual moves toward recovery.

Alternative Endpoints

To achieve a dimensional approach to treatment requires thinking anew about how we develop new treatments and what we expect in a treatment.

The existing pharmacopoeia for substance use disorders is severely limited. The FDA has approved medications only for alcohol, nicotine, and opioid use disorders ( Table 1 ), and currently there are no approved medications for cannabis, cocaine, methamphetamine, or inhalant use disorders. The absence of medications to treat most substance use disorders and the limited number of existing medications for alcohol, nicotine, and opioid use disorders make development of new therapeutics a high priority. Yet drug development for substance use disorders faces great hurdles.

a AMPA=α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid; FDA=U.S. Food and Drug Administration; GABA=γ-aminobutyric acid; NMDA= N -methyl- d -aspartate.

TABLE 1. Drugs approved by the FDA for treatment of substance use disorders a

To obtain FDA approval for most substance use disorders, medications until recently had to demonstrate that they produce abstinence in a significant subset of patients, as measured by negative urine tests. However, the abstinence endpoint is a high bar to achieve, equivalent to requiring remission of pain from an analgesic or remission of depression from an antidepressant. Yet, the FDA granted approval of analgesics and antidepressants on the basis of reduction of symptom severity, not remission ( 2 ). The high bar for addiction medications has discouraged investment by the pharmaceutical industry, and significant public sector help was required to bring many of the currently available medications for substance use disorders to market, including buprenorphine, extended-release naltrexone, lofexidine, and naloxone nasal spray.

Treatment programs for substance use disorders inherited a dichotomous working definition of recovery from the 12-step world of past generations, where being completely “drug free” was not merely the gold standard but the only standard, short of which an addicted individual was regarded as having failed or would not be considered to be “recovering.” Yet evidence indicates that abstinence is not the only clinically relevant outcome for every individual and that alternative endpoints can contribute to recovery even when abstinence is not completely achieved.

Reduced alcohol use (measured as percentage of heavy drinking days) is now being used as an endpoint in clinical trials for treatments for alcohol use disorder. The FDA has also recently expressed its openness to considering endpoints other than abstinence as targets in medication development for other substance use disorders ( 3 , 4 ). Given the illegality of many addictive drugs, it has been argued that any reduction in use should be considered a benefit to the individual’s health and safety ( 5 ). Every time a person addicted to heroin must obtain the drug, he or she faces the risks associated with the drug trade as well as with exposure to fentanyl or a contaminant that could lead to overdose or poisoning.

Recently, researchers found in a pooled sample of study participants with cocaine use disorder that those who had high-frequency use at the start of the study and had reduced to low-frequency use by the end of the study showed outcomes at 1-year follow-up similar to those of participants who had quit altogether ( 6 ).

Treating the Dimensions of Substance Use Disorder

Endpoints other than abstinence may lead not only to treatments that are helpful in reducing drug use but also to the use of compounds that target specific neurobiological processes and symptoms relevant to addiction and the risk for relapse.

In April 2018, the FDA, in partnership with the Addiction Policy Forum and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), convened a meeting to solicit input from patients with opioid use disorder as part of its Patient-Focused Drug Development initiative ( 7 ). Among other things, participants emphasized their desire for a more holistic and individualized approach to treatment, as well as their wish for medications that would address specific symptoms of withdrawal, such as cravings, depression, cognitive impairments, pain, and sleep problems. The same year, the FDA approved lofexidine for treating physical symptoms of opioid withdrawal during detoxification—the first approved drug for treating symptoms associated with opioid use disorder with a restricted purpose and not expected to lead, by itself, to continued abstinence. After detoxification, the individual would ideally be treated with naltrexone or buprenorphine as a longer-term treatment to help prevent relapse and achieve recovery. Other potential targets for medications are those that, while not addressing addiction directly, target major risk factors for relapse.

One such factor is insomnia, for it is frequently interrelated with substance use disorders, with each exacerbating the risk of the other. Findings of shared targets and circuits between disrupted sleep and addiction offer unique opportunities for treatment development. For example, while studying the role of orexin in narcolepsy, researchers serendipitously discovered an unusually high number of orexin-producing neurons in the postmortem brain of a heroin-addicted individual ( 8 ). They subsequently established in preclinical models and postmortem brain studies that long-term use of heroin was associated with an increase in orexin-producing neurons. Since orexin is already targeted by suvorexant, an FDA-approved drug for insomnia, NIDA is funding research to test its efficacy, along with that of other novel orexin receptor antagonists, as therapeutic agents in opioid use disorder.

Similarly, dysphoria and depression, which are frequently associated with protracted withdrawal, are another relevant area where our growing understanding of underlying neurocircuitry could guide selection of promising new targets. For example, the habenular complex is intricately involved in dysphoria and negative emotional states and is associated with depression ( 9 ) and addiction ( 10 ). Both alpha-5 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and mu-opioid receptors are highly expressed in the habenula, where they modulate its activity, contributing to the adverse symptoms of withdrawal that follow nicotine and heroin discontinuation, respectively, and to the relief that follows during intoxication. Targeting the habenula has already been shown to be beneficial in animal models of addiction treatment ( 11 ), and it has been a target for deep brain stimulation for the treatment of depression ( 12 ).

Because of the high comorbidity of substance use disorder with depression, psychiatrists have used antidepressants off-label to treat their addicted patients, even though randomized clinical trials of antidepressants have failed to achieve the desired outcome of abstinence. Recognizing that improving depression could still be beneficial for patients with substance use disorders, studies should revisit the possible efficacy of antidepressants as an element of addiction treatment, using endpoints other than abstinence. Bupropion, which blocks the dopamine and norepinephrine transporters and is an approved antidepressant medication, is also approved for the treatment of nicotine addiction. Given the involvement of the mu-opioid receptor system in mood, it would be expected that targeting depression might have particular value in treating opioid use disorder; an interesting feature of the opioid partial agonist buprenorphine is that it has antidepressant properties ( 13 ), and opioid-addicted patients who have depression respond particularly well to this medication ( 14 ).

Another important therapeutic target is that of addressing social isolation, and while this might be optimally achieved with behavioral interventions, including group treatment, medications could still hold promise. Addicted individuals report reduced pleasure from social contact, as well as fear of the stigma attached to their drug use, and thus they tend to isolate themselves. Isolation in turn drives drug taking ( 15 ). Here again, we could take advantage of our increased understanding of the neurobiology of social attachment to bolster social connections. For example, oxytocin, a neurochemical involved in social bonding that also modulates key processes associated with addiction, including reward and stress responses, is being evaluated as a possible addiction treatment and may enhance the efficacy of psychosocial addiction treatments ( 16 , 17 ).

A dimensional approach to the treatment of substance use disorder is also relevant to neuromodulation. Early research has shown that transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) may be useful in reducing drug cravings, and TMS is already an approved therapy for treatment-resistant depression. Research is needed to study how TMS, tDCS, or peripheral nerve stimulation could be used to improve symptoms associated with addiction, from acute symptoms of withdrawal to the more protracted symptoms of dysphoria and sleep problems. As we understand better how to use neuromodulation technologies to modify brain circuits, it may create opportunities to strengthen specific circuits that can buffer or compensate for others that have been impaired by drug use or constitute a predisposing vulnerability.

Behavioral therapies are also suited to dimensional approaches to substance use disorder treatment. Considerable research already shows the benefits of cognitive-behavioral treatments in improving self-regulation and of contingency management in strengthening the degraded motivation to engage in non-drug-related activities, so clearly these modalities are effective for addressing specific dimensions of the addiction process. Similarly, behavioral treatments to improve executive function could help build resilience against relapse, as shown by methylphenidate’s reported ability to reduce impulsivity in individuals with cocaine use disorder ( 18 ).

Making Addiction Treatment More Dynamic and Personalized

Trajectories of use vary among people who use drugs, ranging from persistent use or declining use to cessation and relapse or sustained cessation. Studies of people who inject opioids, for example, have identified factors that, to some extent, are predictive of these trajectories ( 19 ). Being in a stable relationship, for instance, has been associated with early cessation (highlighting the importance of social support).

Addiction is an evolving disorder that changes through time and across the lifespan of the individual and one that has an unpredictable element that springs from the unique experiences an individual is exposed to. Some widely used behavioral treatments already accommodate and address this changeability of substance use disorder. Cognitive-behavioral therapy teaches the individual to identify external triggers and respond more appropriately to internal states (e.g., mood, craving) that place them at risk for relapse. New technologies are developing algorithms to identify indicators of relapse risk and incorporating them into wearable devices and smartphones with the goal of delivering an intervention in a timely, targeted manner. In the future, as big-data analytics and machine-learning algorithms yield more insight into behavioral and biological markers of relapse risk, tools or devices to avert relapse farther in advance may be developed.

Toward the Future

Neuroscience has revealed that addiction involves a set of interconnected processes that can be targeted strategically, rather than being a disorder defined principally by a single behavior (uncontrollable excessive drug use). Addiction medicine is also increasingly recognizing that factors traditionally associated with recovery are components of treatment. For example, for any meaningful recovery to occur, the individual must be able to integrate him- or herself into a socially meaningful environment. People with substance use disorders who are professionally active or engage in meaningful activity and have a caring family face less of a challenge than those who have no social supports and whose isolation places them at high risk for relapse. The integration of peer mentors, recovery coaching, and supportive housing into addiction treatment is an example of this shift, but more research is needed to determine the most effective ways to sustain social inclusion and to achieve recovery ( 20 ).

Addiction is a complex disorder that involves brain circuits necessary for survival and one that is strongly influenced by genes, development, and social factors. We now understand the underlying mechanisms well enough that we can turn this complexity into an opportunity to include these dimensions as targets for substance use disorder treatment, as well as to personalize interventions to accommodate the unique neurobiological characteristics and social contexts of individual patients.

Dr. Volkow is Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

The author thanks Eric M. Wargo and Emily B. Einstein for their valuable help in the preparation of this article.

1 Koob GF, Volkow ND : Neurocircuitry of addiction . Neuropsychopharmacology 2010 ; 35:217–238 (erratum in Neuropsychopharmacology 2010 Mar; 35:1051) Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

2 Volkow ND, Woodcock J, Compton WM, et al. : Medication development in opioid addiction: meaningful clinical end points . Sci Transl Med 2018 ; 10: eaan2595 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

3 Kiluk BD, Carroll KM, Duhig A, et al. : Measures of outcome for stimulant trials: ACTTION recommendations and research agenda . Drug Alcohol Depend 2016 ; 158:1–7 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

4 US Food and Drug Administration Draft Guidance (FDA): Opioid Use Disorder: Endpoints for Demonstrating Effectiveness of Drugs for Medication-Assisted Treatment: Guidance for Industry. Silver Spring, Md, FDA, August 2018. https://www.fda.gov/media/114948/download Google Scholar

5 McCann DJ, Ramey T, Skolnick P : Outcome measures in medication trials for substance use disorders . Curr Treat Options Psychiatry 2015 ; 2:113–121 Crossref , Google Scholar

6 Roos CR, Nich C, Mun CJ, et al. : Clinical validation of reduction in cocaine frequency level as an endpoint in clinical trials for cocaine use disorder . Drug Alcohol Depend 2019 ; 205: 107648 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

7 Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration: The Voice of the Patient: A Series of Reports From the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Patient-Focused Drug Development Initiative: Opioid Use Disorder. Rockville, Md, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, 2018. https://www.fda.gov/media/124391/download Google Scholar

8 Thannickal TC, John J, Shan L, et al. : Opiates increase the number of hypocretin-producing cells in human and mouse brain and reverse cataplexy in a mouse model of narcolepsy . Sci Transl Med 2018 ; 10: eaao4953 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

9 Lawson RP, Nord CL, Seymour B, et al. : Disrupted habenula function in major depression . Mol Psychiatry 2017 ; 22:202–208 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

10 Velasquez KM, Molfese DL, Salas R : The role of the habenula in drug addiction . Front Hum Neurosci 2014 ; 8:174 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

11 Friedman A, Lax E, Dikshtein Y, et al. : Electrical stimulation of the lateral habenula produces enduring inhibitory effect on cocaine seeking behavior . Neuropharmacology 2010 ; 59:452–459 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

12 Morishita T, Fayad SM, Higuchi MA, et al. : Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: systematic review of clinical outcomes . Neurotherapeutics 2014 ; 11:475–484 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

13 Serafini G, Adavastro G, Canepa G, et al. : The efficacy of buprenorphine in major depression, treatment-resistant depression, and suicidal behavior: a systematic review . Int J Mol Sci 2018 ; 19:2410 Crossref , Google Scholar

14 Dreifuss JA, Griffin ML, Frost K, et al. : Patient characteristics associated with buprenorphine/naloxone treatment outcome for prescription opioid dependence: results from a multisite study . Drug Alcohol Depend 2013 ; 131:112–118 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

15 Venniro M, Zhang M, Caprioli D, et al. : Volitional social interaction prevents drug addiction in rat models . Nat Neurosci 2018 ; 21:1520–1529 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

16 Stauffer CS, Moschetto JM, McKernan SM, et al. : Oxytocin-enhanced motivational interviewing group therapy for methamphetamine use disorder in men who have sex with men: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial . Trials 2019 ; 20:145 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

17 Lee MR, Weerts EM : Oxytocin for the treatment of drug and alcohol use disorders . Behav Pharmacol 2016 ; 27:640–648 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

18 Goldstein RZ, Woicik PA, Maloney T, et al. : Oral methylphenidate normalizes cingulate activity in cocaine addiction during a salient cognitive task . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010 ; 107:16667–16672 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

19 Dong H, Hayashi K, Singer J, et al. : Trajectories of injection drug use among people who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada, 1996–2017: growth mixture modeling using data from prospective cohort studies . Addiction 2019 ; 114:2173–2186 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

20 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA): Social Inclusion (web page). Rockville, Md, SAMHSA, 2019. https://www.samhsa.gov/homelessness-programs-resources/hpr-resources/social-inclusion Google Scholar

- Ghazaleh Soleimani , Ph.D. ,

- Juho Joutsa , M.D., Ph.D. ,

- Khaled Moussawi , M.D., Ph.D. ,

- Shan H. Siddiqi , M.D. ,

- Rayus Kuplicki , Ph.D. ,

- Marom Bikson , Ph.D. ,

- Martin P. Paulus , M.D., Ph.D. ,

- Michael D. Fox , M.D., Ph.D. ,

- Colleen A. Hanlon , Ph.D. ,

- Hamed Ekhtiari , M.D., Ph.D.

- Lara N. Coughlin , Ph.D. ,

- Paul Pfeiffer , M.D. , M.S. ,

- Dara Ganoczy , M.P.H. ,

- Lewei A. Lin , M.D. , M.S.

- Ned H. Kalin , M.D.

- Substance Use Disorder Treatment

- Opioid Use Disorder

- Alcohol Use Disorder

- Nicotine Use Disorder

- Signs of Addiction

Addiction Research

Discover the latest in addiction research, from the neuroscience of substance use disorders to evidence-based treatment practices. reports, updates, case studies and white papers are available to you at hazelden betty ford’s butler center for research..

Why do people become addicted to alcohol and other drugs? How effective is addiction treatment? What makes certain substances so addictive? The Butler Center for Research at the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation investigates these and other questions and publishes its scientific findings in a variety of alcohol and drug addiction research papers and reports. Research topics include:

- Evidence-based treatment practices

- Addiction treatment outcomes

- Addiction, psychiatry and the brain

- Addictive substances such as prescription opioids and heroin

- Substance abuse in youth/teens, older adults and other demographic groups such as health care or legal professionals

These research queries and findings are presented in the form of updates, white papers and case studies. In addition, the Butler Center for Research collaborates with the Recovery Advocacy team to study special-focus addiction research topics, summarized in monthly Emerging Drug Trends reports. Altogether, these studies provide the latest in addiction research for anyone interested in learning more about the neuroscience of addiction and how addiction affects individuals, families and society in general. The research also helps clinicians and health care professionals further understand, diagnose and treat drug and alcohol addiction. Learn more about each of the Butler Center's addiction research studies below.

Research Updates

Written by Butler Center for Research staff, our one-page, topic-specific summaries discuss current research on topics of interest within the drug abuse and addiction treatment field.

View our most recent updates, or view the archive at the bottom of the page.

Patient Outcomes Study Results at Hazelden Betty Ford

Trends and Patterns in Cannabis Use across Different Age Groups

Alcohol and Tobacco Harm Reduction Interventions

Harm Reduction: History and Context

Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities and Addiction

Psychedelics as Therapeutic Treatment

Sexual and Gender Minority Youth and SUDs

Health Care Professionals and Mental Health

Grief and Addiction

Helping Families Cope with Addiction

Emerging Drug Trends Report and National Surveys

Shedding New Light on America’s No. 1 Health Problem

In collaboration with the University of Maryland School of Public Health and with support from the Butler Center for Research, the Recovery Advocacy team routinely issues research reports on emerging drug trends in America. Recovery Advocacy also commissions national surveys on attitudes, behaviors and perspectives related to substance use. From binge drinking and excessive alcohol use on college campuses, to marijuana potency concerns in an age of legalized marijuana, deeper analysis and understanding of emerging drug trends allows for greater opportunities to educate, inform and prevent misuse and deaths.

Each drug trends report explores the topic at hand, documenting the prevalence of the problem, relevant demographics, prevention and treatment options available, as well as providing insight and perspectives from thought leaders throughout the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation.

View the latest Emerging Drug Trends Report:

Pediatricians First Responders for Preventing Substance Use

- Clearing Away the Confusion: Marijuana Is Not a Public Health Solution to the Opioid Crisis

- Does Socioeconomic Advantage Lessen the Risk of Adolescent Substance Use?

- The Collegiate Recovery Movement Is Gaining Strength

- Considerations for Policymakers Regarding Involuntary Commitment for Substance Use Disorders

- Widening the Lens on the Opioid Crisis

- Concerns Rising Over High-Potency Marijuana Use

- Beyond Binging: “High-Intensity Drinking”

View the latest National Surveys :

- College Administrators See Problems As More Students View Marijuana As Safe

College Parents See Serious Problems From Campus Alcohol Use

- Youth Opioid Study: Attitudes and Usage

About Recovery Advocacy

Our mission is to provide a trusted national voice on all issues related to addiction prevention, treatment and recovery, and to facilitate conversation among those in recovery, those still suffering and society at large. We are committed to smashing stigma, shaping public policy and educating people everywhere about the problems of addiction and the promise of recovery. Learn more about recovery advocacy and how you can make a difference.

Evidence-Based Treatment Series

To help get consumers and clinicians on the same page, the Butler Center for Research has created a series of informational summaries describing:

- Evidence-based addiction treatment modalities

- Distinctive levels of substance use disorder treatment

- Specialized drug and alcohol treatment programs

Each evidence-based treatment series summary includes:

- A definition of the therapeutic approach, level of care or specialized program

- A discussion of applicability, usage and practice

- A description of outcomes and efficacy

- Research citations and related resources for more information

View the latest in this series:

Motivational Interviewing

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Case Studies and White Papers

Written by Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation researchers and clinicians, case studies and white papers presented by the Butler Center for Research provide invaluable insight into clinical processes and complex issues related to addiction prevention, treatment and recovery. These in-depth reports examine and chronicle clinical activities, initiatives and developments as a means of informing practitioners and continually improving the quality and delivery of substance use disorder services and related resources and initiatives.

- What does it really mean to be providing medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction?

Adolescent Motivational Interviewing

Peer Recovery Support: Walking the Path Together

Addiction and Violence During COVID-19

The Brain Disease Model of Addiction

Healthcare Professionals and Compassion Fatigue

Moving to Trauma-Responsive Care

Virtual Intensive Outpatient Outcomes: Preliminary Findings

Driving Under the Influence of Cannabis

Vaping and E-Cigarettes

Using Telehealth for Addiction Treatment

Grandparents Raising Grandchildren

Substance Use Disorders Among Military Populations

Co-Occurring Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders

Women and Alcohol

Prescription Rates of Opioid Analgesics in Medical Treatment Settings

Applications of Positive Psychology to Substance Use Disorder

Substance Use Disorders Among Legal Professionals

Factors Impacting Early Alcohol and Drug Use Among Youths

Animal-Assisted Therapy for Substance Use Disorders

Prevalence of Adolescent Substance Misuse

Problem Drinking Behaviors Among College Students

The Importance of Recovery Management

Substance Use Factors Among LGBTQ individuals

Prescription Opioids and Dependence

Alcohol Abuse Among Law Enforcement Officers

Helping Families Cope with Substance Dependence

The Social Norms Approach to Student Substance Abuse Prevention

Drug Abuse, Dopamine and the Brain's Reward System

Women and Substance Abuse

Substance Use in the Workplace

Health Care Professionals: Addiction and Treatment

Cognitive Improvement and Alcohol Recovery

Drug Use, Misuse and Dependence Among Older Adults

Emerging Drug Trends

Does Socioeconomic Advantage Lessen the Risk of Adolescent Substance Use

The Collegiate Recovery Movement is Gaining Strength

Involuntary Commitment for Substance Use Disorders

Widening the Lens of the Opioid Crisis

Beyond Binge Drinking: High Intensity Drinking

High Potency Marijuana

National Surveys

College Administrators See Problems as More Students View Marijuana as Safe

Risky Opioid Use Among College-Age Youth

Case Studies/ White Papers

What does it really mean to be providing medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction

Are you or a loved one struggling with alcohol or other drugs? Call today to speak confidentially with a recovery expert. Most insurance accepted.

Harnessing science, love and the wisdom of lived experience, we are a force of healing and hope for individuals, families and communities affected by substance use and mental health conditions..

Research Topics

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) is the largest supporter of the world’s research on substance use and addiction. Part of the National Institutes of Health, NIDA conducts and supports biomedical research to advance the science on substance use and addiction and improve individual and public health. Look below for more information on drug use, health, and NIDA’s research efforts.

Information provided by NIDA is not a substitute for professional medical care.

In an emergency? Need treatment?

In an emergency:.

- Are you or someone you know experiencing severe symptoms or in immediate danger? Please seek immediate medical attention by calling 9-1-1 or visiting an Emergency Department . Poison control can be reached at 1-800-222-1222 or www.poison.org .

- Are you or someone you know experiencing a substance use and/or mental health crisis or any other kind of emotional distress? Please call or text 988 or chat www.988lifeline.org to reach the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. 988 connects you with a trained crisis counselor who can help.

FIND TREATMENT:

- For referrals to substance use and mental health treatment programs, call the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357) or visit www.FindTreatment.gov to find a qualified healthcare provider in your area.

- For other personal medical advice, please speak to a qualified health professional. Find more health resources on USA.gov .

DISCLAIMER:

The emergency and referral resources listed above are available to individuals located in the United States and are not operated by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). NIDA is a biomedical research organization and does not provide personalized medical advice, treatment, counseling, or legal consultation. Information provided by NIDA is not a substitute for professional medical care or legal consultation.

Research by Substance

Find evidence-based information on specific drugs and substance use disorders.

- Cannabis (Marijuana)

- Commonly Used Drugs Charts

- Methamphetamine

- MDMA (Ecstasy/Molly)

- Over-the-Counter Medicines

- Prescription Medicines

- Psilocybin (Magic Mushrooms)

- Psychedelic and Dissociative Drugs

- Psychedelic and Dissociative Drugs as Medicines

- Steroids (Anabolic)

- Synthetic Cannabinoids (K2/Spice)

- Synthetic Cathinones (Bath Salts)

- Tobacco/Nicotine and Vaping

Drug Use and Addiction

Learn how science has deepened our understanding of drug use and its impact on individual and public health.

- Addiction Science

- Adolescent Brain

- Comorbidity

- Drug Checking

- Drug Testing

- Drugged Driving

- Drugs and the Brain

- Harm Reduction

- Infographics

- Mental Health

- Monitoring the Future

- National Drug Early Warning System (NDEWS)

- Overdose Death Rates

- Overdose Prevention Centers

- Overdose Reversal Medications

- Stigma and Discrimination

- Syringe Services Programs

- Trauma and Stress

- Trends and Statistics

- Words Matter: Preferred Language for Talking About Addiction

People and Places

NIDA research supports people affected by substance use and addiction throughout the lifespan and across communities.

- College-Age and Young Adults

- Criminal Justice

- Global Health

- LGBTQ Populations and Substance Use

- Military Life and Substance Use

- National Drug and Alcohol Facts Week Organizers and Participants

- Older Adults

- Parents and Educators

- Women and Drugs

Related Resources

- Learn more about Overdose Prevention from the Department of Health and Human Services.

- Learn more about substance use treatment, prevention, recovery support, and related services from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration .

- Learn more about the health effects of alcohol and alcohol use disorder from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism .

- Learn more the approval and regulation of prescription medicines from the Food and Drug Administration .

- Learn more about efforts to measure, prevent, and address public health impacts of substance use from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention .

- Learn more about controlled substance law and regulation enforcement from the Drug Enforcement Administration .

- Learn more about policies impacting substance use from the Office of National Drug Control Policy .

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 22 February 2021

Addiction as a brain disease revised: why it still matters, and the need for consilience

- Markus Heilig 1 ,

- James MacKillop ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4118-9500 2 , 3 ,

- Diana Martinez 4 ,

- Jürgen Rehm ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5665-0385 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ,

- Lorenzo Leggio ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7284-8754 9 &

- Louk J. M. J. Vanderschuren ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5379-0363 10

Neuropsychopharmacology volume 46 , pages 1715–1723 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

84k Accesses

94 Citations

321 Altmetric

Metrics details

The view that substance addiction is a brain disease, although widely accepted in the neuroscience community, has become subject to acerbic criticism in recent years. These criticisms state that the brain disease view is deterministic, fails to account for heterogeneity in remission and recovery, places too much emphasis on a compulsive dimension of addiction, and that a specific neural signature of addiction has not been identified. We acknowledge that some of these criticisms have merit, but assert that the foundational premise that addiction has a neurobiological basis is fundamentally sound. We also emphasize that denying that addiction is a brain disease is a harmful standpoint since it contributes to reducing access to healthcare and treatment, the consequences of which are catastrophic. Here, we therefore address these criticisms, and in doing so provide a contemporary update of the brain disease view of addiction. We provide arguments to support this view, discuss why apparently spontaneous remission does not negate it, and how seemingly compulsive behaviors can co-exist with the sensitivity to alternative reinforcement in addiction. Most importantly, we argue that the brain is the biological substrate from which both addiction and the capacity for behavior change arise, arguing for an intensified neuroscientific study of recovery. More broadly, we propose that these disagreements reveal the need for multidisciplinary research that integrates neuroscientific, behavioral, clinical, and sociocultural perspectives.

Similar content being viewed by others

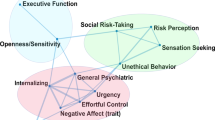

Subtypes in addiction and their neurobehavioral profiles across three functional domains

Gunner Drossel, Leyla R. Brucar, … Anna Zilverstand

Drug addiction: from bench to bedside

Julian Cheron & Alban de Kerchove d’Exaerde

The neurobiology of drug addiction: cross-species insights into the dysfunction and recovery of the prefrontal cortex

Ahmet O. Ceceli, Charles W. Bradberry & Rita Z. Goldstein

Introduction

Close to a quarter of a century ago, then director of the US National Institute on Drug Abuse Alan Leshner famously asserted that “addiction is a brain disease”, articulated a set of implications of this position, and outlined an agenda for realizing its promise [ 1 ]. The paper, now cited almost 2000 times, put forward a position that has been highly influential in guiding the efforts of researchers, and resource allocation by funding agencies. A subsequent 2000 paper by McLellan et al. [ 2 ] examined whether data justify distinguishing addiction from other conditions for which a disease label is rarely questioned, such as diabetes, hypertension or asthma. It concluded that neither genetic risk, the role of personal choices, nor the influence of environmental factors differentiated addiction in a manner that would warrant viewing it differently; neither did relapse rates, nor compliance with treatment. The authors outlined an agenda closely related to that put forward by Leshner, but with a more clinical focus. Their conclusion was that addiction should be insured, treated, and evaluated like other diseases. This paper, too, has been exceptionally influential by academic standards, as witnessed by its ~3000 citations to date. What may be less appreciated among scientists is that its impact in the real world of addiction treatment has remained more limited, with large numbers of patients still not receiving evidence-based treatments.

In recent years, the conceptualization of addiction as a brain disease has come under increasing criticism. When first put forward, the brain disease view was mainly an attempt to articulate an effective response to prevailing nonscientific, moralizing, and stigmatizing attitudes to addiction. According to these attitudes, addiction was simply the result of a person’s moral failing or weakness of character, rather than a “real” disease [ 3 ]. These attitudes created barriers for people with substance use problems to access evidence-based treatments, both those available at the time, such as opioid agonist maintenance, cognitive behavioral therapy-based relapse prevention, community reinforcement or contingency management, and those that could result from research. To promote patient access to treatments, scientists needed to argue that there is a biological basis beneath the challenging behaviors of individuals suffering from addiction. This argument was particularly targeted to the public, policymakers and health care professionals, many of whom held that since addiction was a misery people brought upon themselves, it fell beyond the scope of medicine, and was neither amenable to treatment, nor warranted the use of taxpayer money.

Present-day criticism directed at the conceptualization of addiction as a brain disease is of a very different nature. It originates from within the scientific community itself, and asserts that this conceptualization is neither supported by data, nor helpful for people with substance use problems [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. Addressing these critiques requires a very different perspective, and is the objective of our paper. We readily acknowledge that in some cases, recent critiques of the notion of addiction as a brain disease as postulated originally have merit, and that those critiques require the postulates to be re-assessed and refined. In other cases, we believe the arguments have less validity, but still provide an opportunity to update the position of addiction as a brain disease. Our overarching concern is that questionable arguments against the notion of addiction as a brain disease may harm patients, by impeding access to care, and slowing development of novel treatments.

A premise of our argument is that any useful conceptualization of addiction requires an understanding both of the brains involved, and of environmental factors that interact with those brains [ 9 ]. These environmental factors critically include availability of drugs, but also of healthy alternative rewards and opportunities. As we will show, stating that brain mechanisms are critical for understanding and treating addiction in no way negates the role of psychological, social and socioeconomic processes as both causes and consequences of substance use. To reflect this complex nature of addiction, we have assembled a team with expertise that spans from molecular neuroscience, through animal models of addiction, human brain imaging, clinical addiction medicine, to epidemiology. What brings us together is a passionate commitment to improving the lives of people with substance use problems through science and science-based treatments, with empirical evidence as the guiding principle.

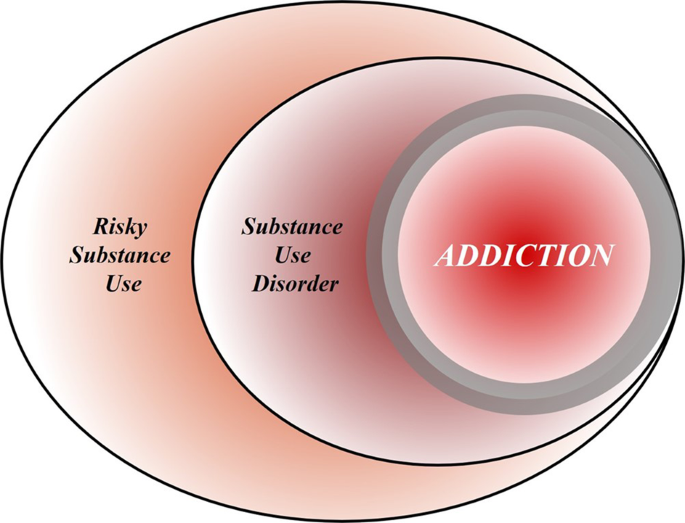

To achieve this goal, we first discuss the nature of the disease concept itself, and why we believe it is important for the science and treatment of addiction. This is followed by a discussion of the main points raised when the notion of addiction as a brain disease has come under criticism. Key among those are claims that spontaneous remission rates are high; that a specific brain pathology is lacking; and that people suffering from addiction, rather than behaving “compulsively”, in fact show a preserved ability to make informed and advantageous choices. In the process of discussing these issues, we also address the common criticism that viewing addiction as a brain disease is a fully deterministic theory of addiction. For our argument, we use the term “addiction” as originally used by Leshner [ 1 ]; in Box 1 , we map out and discuss how this construct may relate to the current diagnostic categories, such as Substance Use Disorder (SUD) and its different levels of severity (Fig. 1) .

Risky (hazardous) substance use refers to quantity/frequency indicators of consumption; SUD refers to individuals who meet criteria for a DSM-5 diagnosis (mild, moderate, or severe); and addiction refers to individuals who exhibit persistent difficulties with self-regulation of drug consumption. Among high-risk individuals, a subgroup will meet criteria for SUD and, among those who have an SUD, a further subgroup would be considered to be addicted to the drug. However, the boundary for addiction is intentionally blurred to reflect that the dividing line for defining addiction within the category of SUD remains an open empirical question.

Box 1 What’s in a name? Differentiating hazardous use, substance use disorder, and addiction

Although our principal focus is on the brain disease model of addiction, the definition of addiction itself is a source of ambiguity. Here, we provide a perspective on the major forms of terminology in the field.

Hazardous Substance Use

Hazardous (risky) substance use refers to quantitative levels of consumption that increase an individual’s risk for adverse health consequences. In practice, this pertains to alcohol use [ 110 , 111 ]. Clinically, alcohol consumption that exceeds guidelines for moderate drinking has been used to prompt brief interventions or referral for specialist care [ 112 ]. More recently, a reduction in these quantitative levels has been validated as treatment endpoints [ 113 ].

Substance Use Disorder

SUD refers to the DSM-5 diagnosis category that encompasses significant impairment or distress resulting from specific categories of psychoactive drug use. The diagnosis of SUD is operationalized as 2 or more of 11 symptoms over the past year. As a result, the diagnosis is heterogenous, with more than 1100 symptom permutations possible. The diagnosis in DSM-5 is the result of combining two diagnoses from the DSM-IV, abuse and dependence, which proved to be less valid than a single dimensional approach [ 114 ]. Critically, SUD includes three levels of severity: mild (2–3 symptoms), moderate (4–5 symptoms), and severe (6+ symptoms). The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) system retains two diagnoses, harmful use (lower severity) and substance dependence (higher severity).

Addiction is a natural language concept, etymologically meaning enslavement, with the contemporary meaning traceable to the Middle and Late Roman Republic periods [ 115 ]. As a scientific construct, drug addiction can be defined as a state in which an individual exhibits an inability to self-regulate consumption of a substance, although it does not have an operational definition. Regarding clinical diagnosis, as it is typically used in scientific and clinical parlance, addiction is not synonymous with the simple presence of SUD. Nowhere in DSM-5 is it articulated that the diagnostic threshold (or any specific number/type of symptoms) should be interpreted as reflecting addiction, which inherently connotes a high degree of severity. Indeed, concerns were raised about setting the diagnostic standard too low because of the issue of potentially conflating a low-severity SUD with addiction [ 116 ]. In scientific and clinical usage, addiction typically refers to individuals at a moderate or high severity of SUD. This is consistent with the fact that moderate-to-severe SUD has the closest correspondence with the more severe diagnosis in ICD [ 117 , 118 , 119 ]. Nonetheless, akin to the undefined overlap between hazardous use and SUD, the field has not identified the exact thresholds of SUD symptoms above which addiction would be definitively present.

Integration

The ambiguous relationships among these terms contribute to misunderstandings and disagreements. Figure 1 provides a simple working model of how these terms overlap. Fundamentally, we consider that these terms represent successive dimensions of severity, clinical “nesting dolls”. Not all individuals consuming substances at hazardous levels have an SUD, but a subgroup do. Not all individuals with a SUD are addicted to the drug in question, but a subgroup are. At the severe end of the spectrum, these domains converge (heavy consumption, numerous symptoms, the unambiguous presence of addiction), but at low severity, the overlap is more modest. The exact mapping of addiction onto SUD is an open empirical question, warranting systematic study among scientists, clinicians, and patients with lived experience. No less important will be future research situating our definition of SUD using more objective indicators (e.g., [ 55 , 120 ]), brain-based and otherwise, and more precisely in relation to clinical needs [ 121 ]. Finally, such work should ultimately be codified in both the DSM and ICD systems to demarcate clearly where the attribution of addiction belongs within the clinical nosology, and to foster greater clarity and specificity in scientific discourse.

What is a disease?

In his classic 1960 book “The Disease Concept of Alcoholism”, Jellinek noted that in the alcohol field, the debate over the disease concept was plagued by too many definitions of “alcoholism” and too few definitions of “disease” [ 10 ]. He suggested that the addiction field needed to follow the rest of medicine in moving away from viewing disease as an “entity”, i.e., something that has “its own independent existence, apart from other things” [ 11 ]. To modern medicine, he pointed out, a disease is simply a label that is agreed upon to describe a cluster of substantial, deteriorating changes in the structure or function of the human body, and the accompanying deterioration in biopsychosocial functioning. Thus, he concluded that alcoholism can simply be defined as changes in structure or function of the body due to drinking that cause disability or death. A disease label is useful to identify groups of people with commonly co-occurring constellations of problems—syndromes—that significantly impair function, and that lead to clinically significant distress, harm, or both. This convention allows a systematic study of the condition, and of whether group members benefit from a specific intervention.

It is not trivial to delineate the exact category of harmful substance use for which a label such as addiction is warranted (See Box 1 ). Challenges to diagnostic categorization are not unique to addiction, however. Throughout clinical medicine, diagnostic cut-offs are set by consensus, commonly based on an evolving understanding of thresholds above which people tend to benefit from available interventions. Because assessing benefits in large patient groups over time is difficult, diagnostic thresholds are always subject to debate and adjustments. It can be debated whether diagnostic thresholds “merely” capture the extreme of a single underlying population, or actually identify a subpopulation that is at some level distinct. Resolving this issue remains challenging in addiction, but once again, this is not different from other areas of medicine [see e.g., [ 12 ] for type 2 diabetes]. Longitudinal studies that track patient trajectories over time may have a better ability to identify subpopulations than cross-sectional assessments [ 13 ].

By this pragmatic, clinical understanding of the disease concept, it is difficult to argue that “addiction” is unjustified as a disease label. Among people who use drugs or alcohol, some progress to using with a quantity and frequency that results in impaired function and often death, making substance use a major cause of global disease burden [ 14 ]. In these people, use occurs with a pattern that in milder forms may be challenging to capture by current diagnostic criteria (See Box 1 ), but is readily recognized by patients, their families and treatment providers when it reaches a severity that is clinically significant [see [ 15 ] for a classical discussion]. In some cases, such as opioid addiction, those who receive the diagnosis stand to obtain some of the greatest benefits from medical treatments in all of clinical medicine [ 16 , 17 ]. Although effect sizes of available treatments are more modest in nicotine [ 18 ] and alcohol addiction [ 19 ], the evidence supporting their efficacy is also indisputable. A view of addiction as a disease is justified, because it is beneficial: a failure to diagnose addiction drastically increases the risk of a failure to treat it [ 20 ].

Of course, establishing a diagnosis is not a requirement for interventions to be meaningful. People with hazardous or harmful substance use who have not (yet) developed addiction should also be identified, and interventions should be initiated to address their substance-related risks. This is particularly relevant for alcohol, where even in the absence of addiction, use is frequently associated with risks or harm to self, e.g., through cardiovascular disease, liver disease or cancer, and to others, e.g., through accidents or violence [ 21 ]. Interventions to reduce hazardous or harmful substance use in people who have not developed addiction are in fact particularly appealing. In these individuals, limited interventions are able to achieve robust and meaningful benefits [ 22 ], presumably because patterns of misuse have not yet become entrenched.

Thus, as originally pointed out by McLellan and colleagues, most of the criticisms of addiction as a disease could equally be applied to other medical conditions [ 2 ]. This type of criticism could also be applied to other psychiatric disorders, and that has indeed been the case historically [ 23 , 24 ]. Today, there is broad consensus that those criticisms were misguided. Few, if any healthcare professionals continue to maintain that schizophrenia, rather than being a disease, is a normal response to societal conditions. Why, then, do people continue to question if addiction is a disease, but not whether schizophrenia, major depressive disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder are diseases? This is particularly troubling given the decades of data showing high co-morbidity of addiction with these conditions [ 25 , 26 ]. We argue that it comes down to stigma. Dysregulated substance use continues to be perceived as a self-inflicted condition characterized by a lack of willpower, thus falling outside the scope of medicine and into that of morality [ 3 ].

Chronic and relapsing, developmentally-limited, or spontaneously remitting?

Much of the critique targeted at the conceptualization of addiction as a brain disease focuses on its original assertion that addiction is a chronic and relapsing condition. Epidemiological data are cited in support of the notion that large proportions of individuals achieve remission [ 27 ], frequently without any formal treatment [ 28 , 29 ] and in some cases resuming low risk substance use [ 30 ]. For instance, based on data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) study [ 27 ], it has been pointed out that a significant proportion of people with an addictive disorder quit each year, and that most afflicted individuals ultimately remit. These spontaneous remission rates are argued to invalidate the concept of a chronic, relapsing disease [ 4 ].

Interpreting these and similar data is complicated by several methodological and conceptual issues. First, people may appear to remit spontaneously because they actually do, but also because of limited test–retest reliability of the diagnosis [ 31 ]. For instance, using a validated diagnostic interview and trained interviewers, the Collaborative Studies on Genetics of Alcoholism examined the likelihood that an individual diagnosed with a lifetime history of substance dependence would retain this classification after 5 years. This is obviously a diagnosis that, once met, by definition cannot truly remit. Lifetime alcohol dependence was indeed stable in individuals recruited from addiction treatment units, ~90% for women, and 95% for men. In contrast, in a community-based sample similar to that used in the NESARC [ 27 ], stability was only ~30% and 65% for women and men, respectively. The most important characteristic that determined diagnostic stability was severity. Diagnosis was stable in severe, treatment-seeking cases, but not in general population cases of alcohol dependence.

These data suggest that commonly used diagnostic criteria alone are simply over-inclusive for a reliable, clinically meaningful diagnosis of addiction. They do identify a core group of treatment seeking individuals with a reliable diagnosis, but, if applied to nonclinical populations, also flag as “cases” a considerable halo of individuals for whom the diagnostic categorization is unreliable. Any meaningful discussion of remission rates needs to take this into account, and specify which of these two populations that is being discussed. Unfortunately, the DSM-5 has not made this task easier. With only 2 out of 11 symptoms being sufficient for a diagnosis of SUD, it captures under a single diagnostic label individuals in a “mild” category, whose diagnosis is likely to have very low test–retest reliability, and who are unlikely to exhibit a chronic relapsing course, together with people at the severe end of the spectrum, whose diagnosis is reliable, many of whom do show a chronic relapsing course.

The NESARC data nevertheless show that close to 10% of people in the general population who are diagnosed with alcohol addiction (here equated with DSM-IV “dependence” used in the NESARC study) never remitted throughout their participation in the survey. The base life-time prevalence of alcohol dependence in NESARC was 12.5% [ 32 ]. Thus, the data cited against the concept of addiction as a chronic relapsing disease in fact indicate that over 1% of the US population develops an alcohol-related condition that is associated with high morbidity and mortality, and whose chronic and/or relapsing nature cannot be disputed, since it does not remit.

Secondly, the analysis of NESARC data [ 4 , 27 ] omits opioid addiction, which, together with alcohol and tobacco, is the largest addiction-related public health problem in the US [ 33 ]. This is probably the addictive condition where an analysis of cumulative evidence most strikingly supports the notion of a chronic disorder with frequent relapses in a large proportion of people affected [ 34 ]. Of course, a large number of people with opioid addiction are unable to express the chronic, relapsing course of their disease, because over the long term, their mortality rate is about 15 times greater than that of the general population [ 35 ]. However, even among those who remain alive, the prevalence of stable abstinence from opioid use after 10–30 years of observation is <30%. Remission may not always require abstinence, for instance in the case of alcohol addiction, but is a reasonable proxy for remission with opioids, where return to controlled use is rare. Embedded in these data is a message of literally vital importance: when opioid addiction is diagnosed and treated as a chronic relapsing disease, outcomes are markedly improved, and retention in treatment is associated with a greater likelihood of abstinence.

The fact that significant numbers of individuals exhibit a chronic relapsing course does not negate that even larger numbers of individuals with SUD according to current diagnostic criteria do not. For instance, in many countries, the highest prevalence of substance use problems is found among young adults, aged 18–25 [ 36 ], and a majority of these ‘age out’ of excessive substance use [ 37 ]. It is also well documented that many individuals with SUD achieve longstanding remission, in many cases without any formal treatment (see e.g., [ 27 , 30 , 38 ]).

Collectively, the data show that the course of SUD, as defined by current diagnostic criteria, is highly heterogeneous. Accordingly, we do not maintain that a chronic relapsing course is a defining feature of SUD. When present in a patient, however, such as course is of clinical significance, because it identifies a need for long-term disease management [ 2 ], rather than expectations of a recovery that may not be within the individual’s reach [ 39 ]. From a conceptual standpoint, however, a chronic relapsing course is neither necessary nor implied in a view that addiction is a brain disease. This view also does not mean that it is irreversible and hopeless. Human neuroscience documents restoration of functioning after abstinence [ 40 , 41 ] and reveals predictors of clinical success [ 42 ]. If anything, this evidence suggests a need to increase efforts devoted to neuroscientific research on addiction recovery [ 40 , 43 ].

Lessons from genetics

For alcohol addiction, meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies has estimated heritability at ~50%, while estimates for opioid addiction are even higher [ 44 , 45 ]. Genetic risk factors are to a large extent shared across substances [ 46 ]. It has been argued that a genetic contribution cannot support a disease view of a behavior, because most behavioral traits, including religious and political inclinations, have a genetic contribution [ 4 ]. This statement, while correct in pointing out broad heritability of behavioral traits, misses a fundamental point. Genetic architecture is much like organ structure. The fact that normal anatomy shapes healthy organ function does not negate that an altered structure can contribute to pathophysiology of disease. The structure of the genetic landscape is no different. Critics further state that a “genetic predisposition is not a recipe for compulsion”, but no neuroscientist or geneticist would claim that genetic risk is “a recipe for compulsion”. Genetic risk is probabilistic, not deterministic. However, as we will see below, in the case of addiction, it contributes to large, consistent probability shifts towards maladaptive behavior.

In dismissing the relevance of genetic risk for addiction, Hall writes that “a large number of alleles are involved in the genetic susceptibility to addiction and individually these alleles might very weakly predict a risk of addiction”. He goes on to conclude that “generally, genetic prediction of the risk of disease (even with whole-genome sequencing data) is unlikely to be informative for most people who have a so-called average risk of developing an addiction disorder” [ 7 ]. This reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of polygenic risk. It is true that a large number of risk alleles are involved, and that the explanatory power of currently available polygenic risk scores for addictive disorders lags behind those for e.g., schizophrenia or major depression [ 47 , 48 ]. The only implication of this, however, is that low average effect sizes of risk alleles in addiction necessitate larger study samples to construct polygenic scores that account for a large proportion of the known heritability.

However, a heritability of addiction of ~50% indicates that DNA sequence variation accounts for 50% of the risk for this condition. Once whole genome sequencing is readily available, it is likely that it will be possible to identify most of that DNA variation. For clinical purposes, those polygenic scores will of course not replace an understanding of the intricate web of biological and social factors that promote or prevent expression of addiction in an individual case; rather, they will add to it [ 49 ]. Meanwhile, however, genome-wide association studies in addiction have already provided important information. For instance, they have established that the genetic underpinnings of alcohol addiction only partially overlap with those for alcohol consumption, underscoring the genetic distinction between pathological and nonpathological drinking behaviors [ 50 ].

It thus seems that, rather than negating a rationale for a disease view of addiction, the important implication of the polygenic nature of addiction risk is a very different one. Genome-wide association studies of complex traits have largely confirmed the century old “infinitisemal model” in which Fisher reconciled Mendelian and polygenic traits [ 51 ]. A key implication of this model is that genetic susceptibility for a complex, polygenic trait is continuously distributed in the population. This may seem antithetical to a view of addiction as a distinct disease category, but the contradiction is only apparent, and one that has long been familiar to quantitative genetics. Viewing addiction susceptibility as a polygenic quantitative trait, and addiction as a disease category is entirely in line with Falconer’s theorem, according to which, in a given set of environmental conditions, a certain level of genetic susceptibility will determine a threshold above which disease will arise.

A brain disease? Then show me the brain lesion!

The notion of addiction as a brain disease is commonly criticized with the argument that a specific pathognomonic brain lesion has not been identified. Indeed, brain imaging findings in addiction (perhaps with the exception of extensive neurotoxic gray matter loss in advanced alcohol addiction) are nowhere near the level of specificity and sensitivity required of clinical diagnostic tests. However, this criticism neglects the fact that neuroimaging is not used to diagnose many neurologic and psychiatric disorders, including epilepsy, ALS, migraine, Huntington’s disease, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia. Even among conditions where signs of disease can be detected using brain imaging, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, a scan is best used in conjunction with clinical acumen when making the diagnosis. Thus, the requirement that addiction be detectable with a brain scan in order to be classified as a disease does not recognize the role of neuroimaging in the clinic.

For the foreseeable future, the main objective of imaging in addiction research is not to diagnose addiction, but rather to improve our understanding of mechanisms that underlie it. The hope is that mechanistic insights will help bring forward new treatments, by identifying candidate targets for them, by pointing to treatment-responsive biomarkers, or both [ 52 ]. Developing innovative treatments is essential to address unmet treatment needs, in particular in stimulant and cannabis addiction, where no approved medications are currently available. Although the task to develop novel treatments is challenging, promising candidates await evaluation [ 53 ]. A particular opportunity for imaging-based research is related to the complex and heterogeneous nature of addictive disorders. Imaging-based biomarkers hold the promise of allowing this complexity to be deconstructed into specific functional domains, as proposed by the RDoC initiative [ 54 ] and its application to addiction [ 55 , 56 ]. This can ultimately guide the development of personalized medicine strategies to addiction treatment.

Countless imaging studies have reported differences in brain structure and function between people with addictive disorders and those without them. Meta-analyses of structural data show that alcohol addiction is associated with gray matter losses in the prefrontal cortex, dorsal striatum, insula, and posterior cingulate cortex [ 57 ], and similar results have been obtained in stimulant-addicted individuals [ 58 ]. Meta-analysis of functional imaging studies has demonstrated common alterations in dorsal striatal, and frontal circuits engaged in reward and salience processing, habit formation, and executive control, across different substances and task-paradigms [ 59 ]. Molecular imaging studies have shown that large and fast increases in dopamine are associated with the reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse, but that after chronic drug use and during withdrawal, brain dopamine function is markedly decreased and that these decreases are associated with dysfunction of prefrontal regions [ 60 ]. Collectively, these findings have given rise to a widely held view of addiction as a disorder of fronto-striatal circuitry that mediates top-down regulation of behavior [ 61 ].

Critics reply that none of the brain imaging findings are sufficiently specific to distinguish between addiction and its absence, and that they are typically obtained in cross-sectional studies that can at best establish correlative rather than causal links. In this, they are largely right, and an updated version of a conceptualization of addiction as a brain disease needs to acknowledge this. Many of the structural brain findings reported are not specific for addiction, but rather shared across psychiatric disorders [ 62 ]. Also, for now, the most sophisticated tools of human brain imaging remain crude in face of complex neural circuit function. Importantly however, a vast literature from animal studies also documents functional changes in fronto-striatal circuits, as well their limbic and midbrain inputs, associated with addictive behaviors [ 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 ]. These are circuits akin to those identified by neuroimaging studies in humans, implicated in positive and negative emotions, learning processes and executive functions, altered function of which is thought to underlie addiction. These animal studies, by virtue of their cellular and molecular level resolution, and their ability to establish causality under experimental control, are therefore an important complement to human neuroimaging work.

Nevertheless, factors that seem remote from the activity of brain circuits, such as policies, substance availability and cost, as well as socioeconomic factors, also are critically important determinants of substance use. In this complex landscape, is the brain really a defensible focal point for research and treatment? The answer is “yes”. As powerfully articulated by Francis Crick [ 69 ], “You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules”. Social and interpersonal factors are critically important in addiction, but they can only exert their influences by impacting neural processes. They must be encoded as sensory data, represented together with memories of the past and predictions about the future, and combined with representations of interoceptive and other influences to provide inputs to the valuation machinery of the brain. Collectively, these inputs drive action selection and execution of behavior—say, to drink or not to drink, and then, within an episode, to stop drinking or keep drinking. Stating that the pathophysiology of addiction is largely about the brain does not ignore the role of other influences. It is just the opposite: it is attempting to understand how those important influences contribute to drug seeking and taking in the context of the brain, and vice versa.

But if the criticism is one of emphasis rather than of principle—i.e., too much brain, too little social and environmental factors – then neuroscientists need to acknowledge that they are in part guilty as charged. Brain-centric accounts of addiction have for a long time failed to pay enough attention to the inputs that social factors provide to neural processing behind drug seeking and taking [ 9 ]. This landscape is, however, rapidly changing. For instance, using animal models, scientists are finding that lack of social play early in life increases the motivation to take addictive substances in adulthood [ 70 ]. Others find that the opportunity to interact with a fellow rat is protective against addiction-like behaviors [ 71 ]. In humans, a relationship has been found between perceived social support, socioeconomic status, and the availability of dopamine D2 receptors [ 72 , 73 ], a biological marker of addiction vulnerability. Those findings in turn provided translation of data from nonhuman primates, which showed that D2 receptor availability can be altered by changes in social hierarchy, and that these changes are associated with the motivation to obtain cocaine [ 74 ].

Epidemiologically, it is well established that social determinants of health, including major racial and ethnic disparities, play a significant role in the risk for addiction [ 75 , 76 ]. Contemporary neuroscience is illuminating how those factors penetrate the brain [ 77 ] and, in some cases, reveals pathways of resilience [ 78 ] and how evidence-based prevention can interrupt those adverse consequences [ 79 , 80 ]. In other words, from our perspective, viewing addiction as a brain disease in no way negates the importance of social determinants of health or societal inequalities as critical influences. In fact, as shown by the studies correlating dopamine receptors with social experience, imaging is capable of capturing the impact of the social environment on brain function. This provides a platform for understanding how those influences become embedded in the biology of the brain, which provides a biological roadmap for prevention and intervention.

We therefore argue that a contemporary view of addiction as a brain disease does not deny the influence of social, environmental, developmental, or socioeconomic processes, but rather proposes that the brain is the underlying material substrate upon which those factors impinge and from which the responses originate. Because of this, neurobiology is a critical level of analysis for understanding addiction, although certainly not the only one. It is recognized throughout modern medicine that a host of biological and non-biological factors give rise to disease; understanding the biological pathophysiology is critical for understanding etiology and informing treatment.

Is a view of addiction as a brain disease deterministic?

A common criticism of the notion that addiction is a brain disease is that it is reductionist and in the end therefore deterministic [ 81 , 82 ]. This is a fundamental misrepresentation. As indicated above, viewing addiction as a brain disease simply states that neurobiology is an undeniable component of addiction. A reason for deterministic interpretations may be that modern neuroscience emphasizes an understanding of proximal causality within research designs (e.g., whether an observed link between biological processes is mediated by a specific mechanism). That does not in any way reflect a superordinate assumption that neuroscience will achieve global causality. On the contrary, since we realize that addiction involves interactions between biology, environment and society, ultimate (complete) prediction of behavior based on an understanding of neural processes alone is neither expected, nor a goal.

A fairer representation of a contemporary neuroscience view is that it believes insights from neurobiology allow useful probabilistic models to be developed of the inherently stochastic processes involved in behavior [see [ 83 ] for an elegant recent example]. Changes in brain function and structure in addiction exert a powerful probabilistic influence over a person’s behavior, but one that is highly multifactorial, variable, and thus stochastic. Philosophically, this is best understood as being aligned with indeterminism, a perspective that has a deep history in philosophy and psychology [ 84 ]. In modern neuroscience, it refers to the position that the dynamic complexity of the brain, given the probabilistic threshold-gated nature of its biology (e.g., action potential depolarization, ion channel gating), means that behavior cannot be definitively predicted in any individual instance [ 85 , 86 ].

Driven by compulsion, or free to choose?

A major criticism of the brain disease view of addiction, and one that is related to the issue of determinism vs indeterminism, centers around the term “compulsivity” [ 6 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 ] and the different meanings it is given. Prominent addiction theories state that addiction is characterized by a transition from controlled to “compulsive” drug seeking and taking [ 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 ], but allocate somewhat different meanings to “compulsivity”. By some accounts, compulsive substance use is habitual and insensitive to its outcomes [ 92 , 94 , 96 ]. Others refer to compulsive use as a result of increasing incentive value of drug associated cues [ 97 ], while others view it as driven by a recruitment of systems that encode negative affective states [ 95 , 98 ].