Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 08 March 2018

Meta-analysis and the science of research synthesis

- Jessica Gurevitch 1 ,

- Julia Koricheva 2 ,

- Shinichi Nakagawa 3 , 4 &

- Gavin Stewart 5

Nature volume 555 , pages 175–182 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

54k Accesses

870 Citations

881 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Biodiversity

- Outcomes research

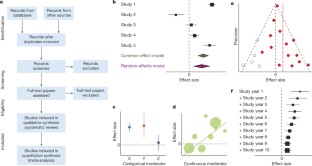

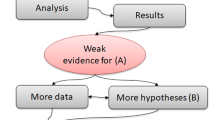

Meta-analysis is the quantitative, scientific synthesis of research results. Since the term and modern approaches to research synthesis were first introduced in the 1970s, meta-analysis has had a revolutionary effect in many scientific fields, helping to establish evidence-based practice and to resolve seemingly contradictory research outcomes. At the same time, its implementation has engendered criticism and controversy, in some cases general and others specific to particular disciplines. Here we take the opportunity provided by the recent fortieth anniversary of meta-analysis to reflect on the accomplishments, limitations, recent advances and directions for future developments in the field of research synthesis.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Eight problems with literature reviews and how to fix them

The past, present and future of Registered Reports

Raiders of the lost HARK: a reproducible inference framework for big data science

Jennions, M. D ., Lortie, C. J. & Koricheva, J. in The Handbook of Meta-analysis in Ecology and Evolution (eds Koricheva, J . et al.) Ch. 23 , 364–380 (Princeton Univ. Press, 2013)

Article Google Scholar

Roberts, P. D ., Stewart, G. B. & Pullin, A. S. Are review articles a reliable source of evidence to support conservation and environmental management? A comparison with medicine. Biol. Conserv. 132 , 409–423 (2006)

Bastian, H ., Glasziou, P . & Chalmers, I. Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: how will we ever keep up? PLoS Med. 7 , e1000326 (2010)

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Borman, G. D. & Grigg, J. A. in The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-analysis 2nd edn (eds Cooper, H. M . et al.) 497–519 (Russell Sage Foundation, 2009)

Ioannidis, J. P. A. The mass production of redundant, misleading, and conflicted systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Milbank Q. 94 , 485–514 (2016)

Koricheva, J . & Gurevitch, J. Uses and misuses of meta-analysis in plant ecology. J. Ecol. 102 , 828–844 (2014)

Littell, J. H . & Shlonsky, A. Making sense of meta-analysis: a critique of “effectiveness of long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy”. Clin. Soc. Work J. 39 , 340–346 (2011)

Morrissey, M. B. Meta-analysis of magnitudes, differences and variation in evolutionary parameters. J. Evol. Biol. 29 , 1882–1904 (2016)

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Whittaker, R. J. Meta-analyses and mega-mistakes: calling time on meta-analysis of the species richness-productivity relationship. Ecology 91 , 2522–2533 (2010)

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Begley, C. G . & Ellis, L. M. Drug development: Raise standards for preclinical cancer research. Nature 483 , 531–533 (2012); clarification 485 , 41 (2012)

Article CAS ADS PubMed Google Scholar

Hillebrand, H . & Cardinale, B. J. A critique for meta-analyses and the productivity-diversity relationship. Ecology 91 , 2545–2549 (2010)

Moher, D . et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6 , e1000097 (2009). This paper provides a consensus regarding the reporting requirements for medical meta-analysis and has been highly influential in ensuring good reporting practice and standardizing language in evidence-based medicine, with further guidance for protocols, individual patient data meta-analyses and animal studies.

Moher, D . et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 4 , 1 (2015)

Nakagawa, S . & Santos, E. S. A. Methodological issues and advances in biological meta-analysis. Evol. Ecol. 26 , 1253–1274 (2012)

Nakagawa, S ., Noble, D. W. A ., Senior, A. M. & Lagisz, M. Meta-evaluation of meta-analysis: ten appraisal questions for biologists. BMC Biol. 15 , 18 (2017)

Hedges, L. & Olkin, I. Statistical Methods for Meta-analysis (Academic Press, 1985)

Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 36 , 1–48 (2010)

Anzures-Cabrera, J . & Higgins, J. P. T. Graphical displays for meta-analysis: an overview with suggestions for practice. Res. Synth. Methods 1 , 66–80 (2010)

Egger, M ., Davey Smith, G ., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br. Med. J. 315 , 629–634 (1997)

Article CAS Google Scholar

Duval, S . & Tweedie, R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 56 , 455–463 (2000)

Article CAS MATH PubMed Google Scholar

Leimu, R . & Koricheva, J. Cumulative meta-analysis: a new tool for detection of temporal trends and publication bias in ecology. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 271 , 1961–1966 (2004)

Higgins, J. P. T . & Green, S. (eds) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions : Version 5.1.0 (Wiley, 2011). This large collaborative work provides definitive guidance for the production of systematic reviews in medicine and is of broad interest for methods development outside the medical field.

Lau, J ., Rothstein, H. R . & Stewart, G. B. in The Handbook of Meta-analysis in Ecology and Evolution (eds Koricheva, J . et al.) Ch. 25 , 407–419 (Princeton Univ. Press, 2013)

Lortie, C. J ., Stewart, G ., Rothstein, H. & Lau, J. How to critically read ecological meta-analyses. Res. Synth. Methods 6 , 124–133 (2015)

Murad, M. H . & Montori, V. M. Synthesizing evidence: shifting the focus from individual studies to the body of evidence. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 309 , 2217–2218 (2013)

Rasmussen, S. A ., Chu, S. Y ., Kim, S. Y ., Schmid, C. H . & Lau, J. Maternal obesity and risk of neural tube defects: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 198 , 611–619 (2008)

Littell, J. H ., Campbell, M ., Green, S . & Toews, B. Multisystemic therapy for social, emotional, and behavioral problems in youth aged 10–17. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004797.pub4 (2005)

Schmidt, F. L. What do data really mean? Research findings, meta-analysis, and cumulative knowledge in psychology. Am. Psychol. 47 , 1173–1181 (1992)

Button, K. S . et al. Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14 , 365–376 (2013); erratum 14 , 451 (2013)

Parker, T. H . et al. Transparency in ecology and evolution: real problems, real solutions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 31 , 711–719 (2016)

Stewart, G. Meta-analysis in applied ecology. Biol. Lett. 6 , 78–81 (2010)

Sutherland, W. J ., Pullin, A. S ., Dolman, P. M . & Knight, T. M. The need for evidence-based conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19 , 305–308 (2004)

Lowry, E . et al. Biological invasions: a field synopsis, systematic review, and database of the literature. Ecol. Evol. 3 , 182–196 (2013)

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Parmesan, C . & Yohe, G. A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature 421 , 37–42 (2003)

Jennions, M. D ., Lortie, C. J . & Koricheva, J. in The Handbook of Meta-analysis in Ecology and Evolution (eds Koricheva, J . et al.) Ch. 24 , 381–403 (Princeton Univ. Press, 2013)

Balvanera, P . et al. Quantifying the evidence for biodiversity effects on ecosystem functioning and services. Ecol. Lett. 9 , 1146–1156 (2006)

Cardinale, B. J . et al. Effects of biodiversity on the functioning of trophic groups and ecosystems. Nature 443 , 989–992 (2006)

Rey Benayas, J. M ., Newton, A. C ., Diaz, A. & Bullock, J. M. Enhancement of biodiversity and ecosystem services by ecological restoration: a meta-analysis. Science 325 , 1121–1124 (2009)

Article ADS PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Leimu, R ., Mutikainen, P. I. A ., Koricheva, J. & Fischer, M. How general are positive relationships between plant population size, fitness and genetic variation? J. Ecol. 94 , 942–952 (2006)

Hillebrand, H. On the generality of the latitudinal diversity gradient. Am. Nat. 163 , 192–211 (2004)

Gurevitch, J. in The Handbook of Meta-analysis in Ecology and Evolution (eds Koricheva, J . et al.) Ch. 19 , 313–320 (Princeton Univ. Press, 2013)

Rustad, L . et al. A meta-analysis of the response of soil respiration, net nitrogen mineralization, and aboveground plant growth to experimental ecosystem warming. Oecologia 126 , 543–562 (2001)

Adams, D. C. Phylogenetic meta-analysis. Evolution 62 , 567–572 (2008)

Hadfield, J. D . & Nakagawa, S. General quantitative genetic methods for comparative biology: phylogenies, taxonomies and multi-trait models for continuous and categorical characters. J. Evol. Biol. 23 , 494–508 (2010)

Lajeunesse, M. J. Meta-analysis and the comparative phylogenetic method. Am. Nat. 174 , 369–381 (2009)

Rosenberg, M. S ., Adams, D. C . & Gurevitch, J. MetaWin: Statistical Software for Meta-Analysis with Resampling Tests Version 1 (Sinauer Associates, 1997)

Wallace, B. C . et al. OpenMEE: intuitive, open-source software for meta-analysis in ecology and evolutionary biology. Methods Ecol. Evol. 8 , 941–947 (2016)

Gurevitch, J ., Morrison, J. A . & Hedges, L. V. The interaction between competition and predation: a meta-analysis of field experiments. Am. Nat. 155 , 435–453 (2000)

Adams, D. C ., Gurevitch, J . & Rosenberg, M. S. Resampling tests for meta-analysis of ecological data. Ecology 78 , 1277–1283 (1997)

Gurevitch, J . & Hedges, L. V. Statistical issues in ecological meta-analyses. Ecology 80 , 1142–1149 (1999)

Schmid, C. H . & Mengersen, K. in The Handbook of Meta-analysis in Ecology and Evolution (eds Koricheva, J . et al.) Ch. 11 , 145–173 (Princeton Univ. Press, 2013)

Eysenck, H. J. Exercise in mega-silliness. Am. Psychol. 33 , 517 (1978)

Simberloff, D. Rejoinder to: Don’t calculate effect sizes; study ecological effects. Ecol. Lett. 9 , 921–922 (2006)

Cadotte, M. W ., Mehrkens, L. R . & Menge, D. N. L. Gauging the impact of meta-analysis on ecology. Evol. Ecol. 26 , 1153–1167 (2012)

Koricheva, J ., Jennions, M. D. & Lau, J. in The Handbook of Meta-analysis in Ecology and Evolution (eds Koricheva, J . et al.) Ch. 15 , 237–254 (Princeton Univ. Press, 2013)

Lau, J ., Ioannidis, J. P. A ., Terrin, N ., Schmid, C. H . & Olkin, I. The case of the misleading funnel plot. Br. Med. J. 333 , 597–600 (2006)

Vetter, D ., Rucker, G. & Storch, I. Meta-analysis: a need for well-defined usage in ecology and conservation biology. Ecosphere 4 , 1–24 (2013)

Mengersen, K ., Jennions, M. D. & Schmid, C. H. in The Handbook of Meta-analysis in Ecology and Evolution (eds Koricheva, J. et al.) Ch. 16 , 255–283 (Princeton Univ. Press, 2013)

Patsopoulos, N. A ., Analatos, A. A. & Ioannidis, J. P. A. Relative citation impact of various study designs in the health sciences. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 293 , 2362–2366 (2005)

Kueffer, C . et al. Fame, glory and neglect in meta-analyses. Trends Ecol. Evol. 26 , 493–494 (2011)

Cohnstaedt, L. W. & Poland, J. Review Articles: The black-market of scientific currency. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 110 , 90 (2017)

Longo, D. L. & Drazen, J. M. Data sharing. N. Engl. J. Med. 374 , 276–277 (2016)

Gauch, H. G. Scientific Method in Practice (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2003)

Science Staff. Dealing with data: introduction. Challenges and opportunities. Science 331 , 692–693 (2011)

Nosek, B. A . et al. Promoting an open research culture. Science 348 , 1422–1425 (2015)

Article CAS ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Stewart, L. A . et al. Preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data: the PRISMA-IPD statement. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 313 , 1657–1665 (2015)

Saldanha, I. J . et al. Evaluating Data Abstraction Assistant, a novel software application for data abstraction during systematic reviews: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Syst. Rev. 5 , 196 (2016)

Tipton, E. & Pustejovsky, J. E. Small-sample adjustments for tests of moderators and model fit using robust variance estimation in meta-regression. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 40 , 604–634 (2015)

Mengersen, K ., MacNeil, M. A . & Caley, M. J. The potential for meta-analysis to support decision analysis in ecology. Res. Synth. Methods 6 , 111–121 (2015)

Ashby, D. Bayesian statistics in medicine: a 25 year review. Stat. Med. 25 , 3589–3631 (2006)

Article MathSciNet PubMed Google Scholar

Senior, A. M . et al. Heterogeneity in ecological and evolutionary meta-analyses: its magnitude and implications. Ecology 97 , 3293–3299 (2016)

McAuley, L ., Pham, B ., Tugwell, P . & Moher, D. Does the inclusion of grey literature influence estimates of intervention effectiveness reported in meta-analyses? Lancet 356 , 1228–1231 (2000)

Koricheva, J ., Gurevitch, J . & Mengersen, K. (eds) The Handbook of Meta-Analysis in Ecology and Evolution (Princeton Univ. Press, 2013) This book provides the first comprehensive guide to undertaking meta-analyses in ecology and evolution and is also relevant to other fields where heterogeneity is expected, incorporating explicit consideration of the different approaches used in different domains.

Lumley, T. Network meta-analysis for indirect treatment comparisons. Stat. Med. 21 , 2313–2324 (2002)

Zarin, W . et al. Characteristics and knowledge synthesis approach for 456 network meta-analyses: a scoping review. BMC Med. 15 , 3 (2017)

Elliott, J. H . et al. Living systematic reviews: an emerging opportunity to narrow the evidence-practice gap. PLoS Med. 11 , e1001603 (2014)

Vandvik, P. O ., Brignardello-Petersen, R . & Guyatt, G. H. Living cumulative network meta-analysis to reduce waste in research: a paradigmatic shift for systematic reviews? BMC Med. 14 , 59 (2016)

Jarvinen, A. A meta-analytic study of the effects of female age on laying date and clutch size in the Great Tit Parus major and the Pied Flycatcher Ficedula hypoleuca . Ibis 133 , 62–67 (1991)

Arnqvist, G. & Wooster, D. Meta-analysis: synthesizing research findings in ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 10 , 236–240 (1995)

Hedges, L. V ., Gurevitch, J . & Curtis, P. S. The meta-analysis of response ratios in experimental ecology. Ecology 80 , 1150–1156 (1999)

Gurevitch, J ., Curtis, P. S. & Jones, M. H. Meta-analysis in ecology. Adv. Ecol. Res 32 , 199–247 (2001)

Lajeunesse, M. J. phyloMeta: a program for phylogenetic comparative analyses with meta-analysis. Bioinformatics 27 , 2603–2604 (2011)

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Pearson, K. Report on certain enteric fever inoculation statistics. Br. Med. J. 2 , 1243–1246 (1904)

Fisher, R. A. Statistical Methods for Research Workers (Oliver and Boyd, 1925)

Yates, F. & Cochran, W. G. The analysis of groups of experiments. J. Agric. Sci. 28 , 556–580 (1938)

Cochran, W. G. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics 10 , 101–129 (1954)

Smith, M. L . & Glass, G. V. Meta-analysis of psychotherapy outcome studies. Am. Psychol. 32 , 752–760 (1977)

Glass, G. V. Meta-analysis at middle age: a personal history. Res. Synth. Methods 6 , 221–231 (2015)

Cooper, H. M ., Hedges, L. V . & Valentine, J. C. (eds) The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-analysis 2nd edn (Russell Sage Foundation, 2009). This book is an important compilation that builds on the ground-breaking first edition to set the standard for best practice in meta-analysis, primarily in the social sciences but with applications to medicine and other fields.

Rosenthal, R. Meta-analytic Procedures for Social Research (Sage, 1991)

Hunter, J. E ., Schmidt, F. L. & Jackson, G. B. Meta-analysis: Cumulating Research Findings Across Studies (Sage, 1982)

Gurevitch, J ., Morrow, L. L ., Wallace, A . & Walsh, J. S. A meta-analysis of competition in field experiments. Am. Nat. 140 , 539–572 (1992). This influential early ecological meta-analysis reports multiple experimental outcomes on a longstanding and controversial topic that introduced a wide range of ecologists to research synthesis methods.

O’Rourke, K. An historical perspective on meta-analysis: dealing quantitatively with varying study results. J. R. Soc. Med. 100 , 579–582 (2007)

Shadish, W. R . & Lecy, J. D. The meta-analytic big bang. Res. Synth. Methods 6 , 246–264 (2015)

Glass, G. V. Primary, secondary, and meta-analysis of research. Educ. Res. 5 , 3–8 (1976)

DerSimonian, R . & Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control. Clin. Trials 7 , 177–188 (1986)

Lipsey, M. W . & Wilson, D. B. The efficacy of psychological, educational, and behavioral treatment. Confirmation from meta-analysis. Am. Psychol. 48 , 1181–1209 (1993)

Chalmers, I. & Altman, D. G. Systematic Reviews (BMJ Publishing Group, 1995)

Moher, D . et al. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of reporting of meta-analyses. Lancet 354 , 1896–1900 (1999)

Higgins, J. P. & Thompson, S. G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 21 , 1539–1558 (2002)

Download references

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this Review to the memory of Ingram Olkin and William Shadish, founding members of the Society for Research Synthesis Methodology who made tremendous contributions to the development of meta-analysis and research synthesis and to the supervision of generations of students. We thank L. Lagisz for help in preparing the figures. We are grateful to the Center for Open Science and the Laura and John Arnold Foundation for hosting and funding a workshop, which was the origination of this article. S.N. is supported by Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT130100268). J.G. acknowledges funding from the US National Science Foundation (ABI 1262402).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Ecology and Evolution, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, 11794-5245, New York, USA

Jessica Gurevitch

School of Biological Sciences, Royal Holloway University of London, Egham, TW20 0EX, Surrey, UK

Julia Koricheva

Evolution and Ecology Research Centre and School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, 2052, New South Wales, Australia

Shinichi Nakagawa

Diabetes and Metabolism Division, Garvan Institute of Medical Research, 384 Victoria Street, Darlinghurst, Sydney, 2010, New South Wales, Australia

School of Natural and Environmental Sciences, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 7RU, UK

Gavin Stewart

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed equally in designing the study and writing the manuscript, and so are listed alphabetically.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Jessica Gurevitch , Julia Koricheva , Shinichi Nakagawa or Gavin Stewart .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Reviewer Information Nature thanks D. Altman, M. Lajeunesse, D. Moher and G. Romero for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

PowerPoint slides

Powerpoint slide for fig. 1, rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Gurevitch, J., Koricheva, J., Nakagawa, S. et al. Meta-analysis and the science of research synthesis. Nature 555 , 175–182 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25753

Download citation

Received : 04 March 2017

Accepted : 12 January 2018

Published : 08 March 2018

Issue Date : 08 March 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25753

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses

Affiliations.

- 1 Behavioural Science Centre, Stirling Management School, University of Stirling, Stirling FK9 4LA, United Kingdom; email: [email protected].

- 2 Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science, London School of Economics and Political Science, London WC2A 2AE, United Kingdom.

- 3 Department of Statistics, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, USA; email: [email protected].

- PMID: 30089228

- DOI: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

Systematic reviews are characterized by a methodical and replicable methodology and presentation. They involve a comprehensive search to locate all relevant published and unpublished work on a subject; a systematic integration of search results; and a critique of the extent, nature, and quality of evidence in relation to a particular research question. The best reviews synthesize studies to draw broad theoretical conclusions about what a literature means, linking theory to evidence and evidence to theory. This guide describes how to plan, conduct, organize, and present a systematic review of quantitative (meta-analysis) or qualitative (narrative review, meta-synthesis) information. We outline core standards and principles and describe commonly encountered problems. Although this guide targets psychological scientists, its high level of abstraction makes it potentially relevant to any subject area or discipline. We argue that systematic reviews are a key methodology for clarifying whether and how research findings replicate and for explaining possible inconsistencies, and we call for researchers to conduct systematic reviews to help elucidate whether there is a replication crisis.

Keywords: evidence; guide; meta-analysis; meta-synthesis; narrative; systematic review; theory.

- Guidelines as Topic

- Meta-Analysis as Topic*

- Publication Bias

- Review Literature as Topic

- Systematic Reviews as Topic*

Library Services

UCL LIBRARY SERVICES

- Guides and databases

- Library skills

- Systematic reviews

Synthesis and systematic maps

- What are systematic reviews?

- Types of systematic reviews

- Formulating a research question

- Identifying studies

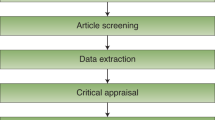

- Searching databases

- Describing and appraising studies

- Software for systematic reviews

- Online training and support

- Live and face to face training

- Individual support

- Further help

On this page:

Types of synthesis

- Systematic evidence map

Synthesis is the process of combining the findings of research studies. A synthesis is also the product and output of the combined studies. This output may be a written narrative, a table, or graphical plots, including statistical meta-analysis. The process of combining studies and the way the output is reported varies according to the research question of the review.

In primary research there are many research questions and many different methods to address them. The same is true of systematic reviews. Two common and different types of review are those asking about the evidence of impact (effectiveness) of an intervention and those asking about ways of understanding a social phenomena.

If a systematic review question is about the effectiveness of an intervention, then the included studies are likely to be experimental studies that test whether an intervention is effective or not. These studies report evidence of the relative effect of an intervention compared to control conditions.

A synthesis of these types of studies aggregates the findings of the studies together. This produces an overall measure of effect of the intervention (after taking into account the sample sizes of the studies). This is a type of quantitative synthesis that is testing a hypothesis (that an intervention is effective) and the review methods are described in advance (using a deductive a priori paradigm).

- Ongoing developments in meta-analytic and quantitative synthesis methods: Broadening the types of research questions that can be addressed O'Mara-Eves, A. and Thomas, J. (2016). This paper discusses different types of quantitative synthesis in education research.

If a systematic review question is about ways of understanding a social phenomena, it iteratively analyses the findings of studies to develop overarching concepts, theories or themes. The included studies are likely to provide theories, concepts or insights about a phenomena. This might, for example, be studies trying to explain why patients do not always take the medicines provided to them by doctors.

A synthesis of these types of studies is an arrangement or configuration of the concepts from individual studies. It provides overall ‘meta’ concepts to help understand the phenomena under study. This type of qualitative or conceptual synthesis is more exploratory and some of the detailed methods may develop during the process of the review (using an inductive iterative paradigm).

- Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review Barnett-Page and Thomas, (2009). This paper summarises some of the different approaches to qualitative synthesis.

There are also multi-component reviews that ask broad question with sub-questions using different review methods.

- Teenage pregnancy and social disadvantage: systematic review integrating controlled trials and qualitative studies. Harden et al (2009). An example of a review that combines two types of synthesis. It develops: 1) a statistical meta-analysis of controlled trials on interventions for early parenthood; and 2) a thematic synthesis of qualitative studies of young people views of early parenthood.

Systematic evidence maps

Systematic evidence maps are a product that describe the nature of research in an area. This is in contrast to a synthesis that provides uses research findings to make a statement about an evidence base. A 'systematic map' can both explain what has been studied and also indicate what has not been studied and where there are gaps in the research (gap maps). They can be useful to compare trends and differences across sets of studies.

Systematic maps can be a standalone finished product of research, without a synthesis, or may also be a component a systematic review that will synthesise studies.

A systematic map can help to plan a synthesis. It may be that the map shows that the studies to be synthesised are very different from each other, and it may be more appropriate to use a subset of the studies. Where a subset of studies is used in the synthesis, the review question and the boundaries of the review will need to be narrowed in order to provide a rigorous approach for selecting the sub-set of studies from the map. The studies in the map that are not synthesised can help with interpreting the synthesis and drawing conclusions. Please note that, confusingly, the 'scoping review' is sometimes used by people to describe systematic evidence maps and at other times to refer to reviews that are quick, selective scopes of the nature and size of literature in an area.

A systematic map may be published in different formats, such as a written report or database. Increasingly, maps are published as databases with interactive visualisations to enable the user to investigate and visualise different parts of the map. Living systematic maps are regularly updated so the evidence stays current.

Some examples of different maps are shown here:

- Women in Wage Labour: An evidence map of what works to increase female wage labour market participation in LMICs Filters Example of a systematic evidence map from the Africa Centre for Evidence.

- Acceptability and uptake of vaccines: Rapid map of systematic reviews Example of a map of systematic reviews.

- COVID-19: a living systematic map of the evidence Example of a living map of health research on COVID-19.

Meta-analysis

- What is a meta-analysis? Helpful resource from the University of Nottingham.

- MetaLight: software for teaching and learning meta-analysis Software tool that can help in learning about meta-analysis.

- KTDRR Research Evidence Training: An Overview of Effect Sizes and Meta-analysis Webcast video (56 mins). Overview of effect sizes and meta-analysis.

- << Previous: Describing and appraising studies

- Next: Software for systematic reviews >>

- Last Updated: Apr 4, 2024 10:09 AM

- URL: https://library-guides.ucl.ac.uk/systematic-reviews

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: Synthesis & Discussion

- Get Started

- Exploratory Search

- Where to Search

- How to Search

- Grey Literature

- What about errata and retractions?

- Eligibility Screening

- Critical Appraisal

- Data Extraction

- Synthesis & Discussion

- Assess Certainty

- Share & Archive

One of the final steps in a systematic review is the synthesis of evidence and writing the discussion.

Your team began working toward this stage in the protocol when you clearly identified the comparisons of interest. The work you've done in data extraction and critical appraisal phases will feed directly into the synthesis.

Qualitative Synthesis

Qualitative synthesis in systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses.

Selecting the best approach for synthesis will depend on your scope , included material, field of research, etc. Therefore, it is important to follow methodological guidance that best matches your scope and field (e.g., a heath-focused review guided by the Cochrane Handbook ). It can also be helpful to check out the synthesis and discussion of systematic reviews published by journals to which you plan to submit your review.

In almost all cases, a qualitative synthesis of some kind will be part of your systematic review. A quantitative synthesis (e.g., meta-analysis ) should only be pursued as appropriate.

Meta-synthesis and Qualitative Evidence Synthesis are term sometimes used to describe a systematic review with only a qualitative synthesis .

Guidance for Qualitative Synthesis

In some methodological guidance , this stage may effectively be described as a separate methodology altogether.

For example, the Cochrane Handbook, Part 2: Core Methods covers synthesis through the lens of conducting a meta-analysis and/or quantitative synthesis. In Part 3: Specific perspectives in reviews, Cochrane goes into more detail about qualitative evidence synthesis in Chapter 21 : Qualitative Evidence. Similarly, the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis contains a stand-alone chapter, Chapter 2: Systematic Reviews of Qualitative Evidence

Considerations and Decisions

- How you will group data for your synthesis and how grouping decisions are made , whether you're pursuing just a qualitative synthesis or both a qualitative synthesis and a meta-analysis, is an important consideration prior to starting the synthesis.

- Assess heterogeneity between studies, even if you don't plan to pursue a meta-analysis. Consider variability in participants studied, the definitions/measurements/frequency/etc. of interventions, or exposures, or outcomes, etc. This is part of the process to determine which studies are reasonable to synthesize.

- Selection of a formal qualitative synthesis approach ( optional )

Qualitative Data and Analysis Tools

Check out this Library Guide for more information about tools for qualitative data anlaysis at Virginia Tech.

Qualitative Synthesis Approaches

This is not a comprehensive list of approaches. However, it can be a jumping off point for your team as you plan. The selection of approaches listed here is partially informed by Barnett-Page & Thomas (2009)

Note: Many of these approaches are also stand-alone qualitative research methods.

Content Analysis

"In the case of qualitative systematic reviews, raw data consist of qualitative research findings (i.e. text) that have been systematically extracted from existing research reports...The manner in which these findings are coded is largely guided by the research topic and questions and the data that are available for analysis." ( Finfgeld-Connett, 2014 )

- Identification of data segments

- Memoing & diagramming

Resources for Content Analysis

- Finfgeld-Connett D. Use of content analysis to conduct knowledge-building and theory-generating qualitative systematic reviews . Qualitative Research . 2014;14(3):341-352. doi:10.1177/1468794113481790

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process . Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Mayring, P. (2015). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical background and procedures . In A. Bikner-Ahsbahs, C. Knipping, & N. Presmeg (Eds.), Approaches to Qualitative Research in Mathematics Education: Examples of Methodology and Methods (pp. 365–380). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9181-6_13

Thematic Synthesis

"Developed out of a need to conduct reviews that addressed questions relating to intervention need, appropriateness, acceptability, [and effectiveness] without compromising on key principles developed in systematic reviews"( Barnett-Paige & Thomas 2009 )

According to Thomas & Harden (2008) :

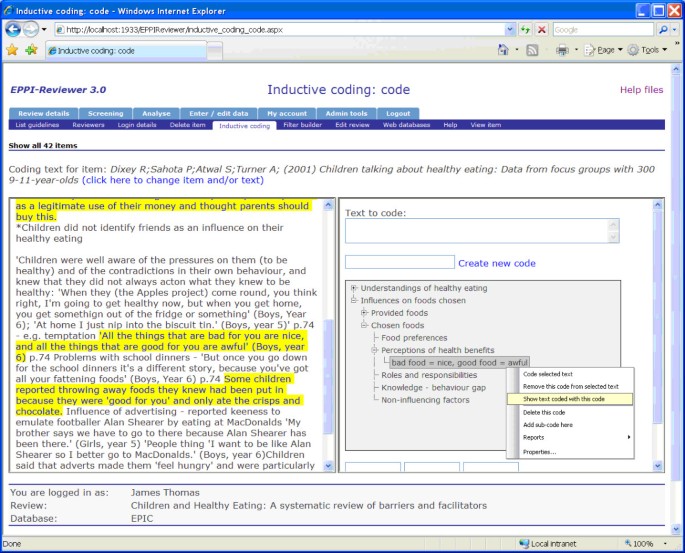

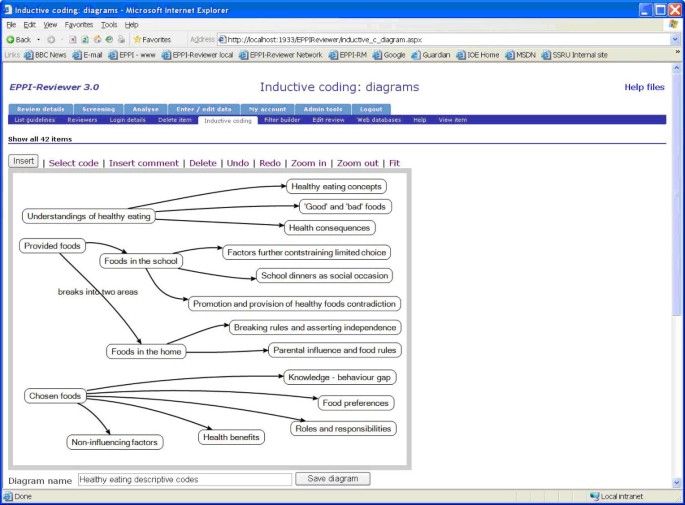

- Code text (line-by-line)

- Develop descriptive themes

- Generate analytic themes

Resources for Thematic Synthesis

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews . BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008 Jul 10;8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. PMID: 18616818; PMCID: PMC2478656.

Framework Synthesis

The "rationale [behind framework synthesis] is that qualitative research produces large amounts of textual data in the form of transcripts, observational fieldnotes etc. The sheer wealth of information poses a challenge for rigorous analysis. Framework synthesis offers a highly structured approach to organising and analysing data (e.g. indexing using numerical codes, rearranging data into charts etc)." ( Barnett-Page & Thomas, 2009 )

According to Brunton & James (2020) :

- Familiarization (with existing literature)

- Framework selection

- Indexing & charting

- Mapping & interpretation

Resources for Framework Synthesis

- Brunton, G., Oliver, S., & Thomas, J. (2020). Innovations in framework synthesis as a systematic review method . Research Synthesis Methods, 11(3), 316–330. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1399

- Dixon-Woods, M. Using framework-based synthesis for conducting reviews of qualitative studies . BMC Med 9, 39 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-9-39

Grounded Theory

Grounded theory is defined as "a specific methodology developed by Glaser and Strauss (1967) for the purpose of building theory from data . In this book the term grounded theory is used in a more generic sense to denote theoretical constructs derived from qualitative analysis of data." ( Strauss & Corbin, 2008 )

According to Barnett-Paige & Thomas, 2009 , "key methods and assumptions...include":

- " simultaneous phases of data collection and analysis;

- inductive approach to analysis, allowing the theory to emerge from the theory ;

- the use of constant comparison method ;

- the use of theoretical sampling to reach theoretical saturation; and the generation of new theory"

Resources for Grounded Theory

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research . Aldine.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research (3rd ed.): Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory . SAGE Publications, Inc. https://dx. doi. org/10.4135/9781452230153

Meta-Ethnography

This is proposed as an alternative to "Meta-Analysis" (Nolbit & Hare, 1998; Barnett-Paige & Thomas 2009 ) and "should be interpretive rather than aggregative . We make the case that is should take the form of reciprocal translations of studies into one another" (Nolbit & Hare, 1998)

- Reciprocal translational analysis (RTA) - translate concepts; evolve overarching concepts

- Refutational synthesis - explore and explain contradictions between studies

- Lines-of-argument (LOA) synthesis - building up a picture of a whole from the parts (the individual studies)

Reporting Guideline

Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: The eMERGe reporting guidance (documents the development of eMERGe)

Resources for Meta-Ethnography

- Sattar, R., Lawton, R., Panagioti, M. et al. Meta-ethnography in healthcare research: a guide to using a meta-ethnographic approach for literature synthesis . BMC Health Serv Res 21, 50 (2021). https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.vt.edu/10.1186/s12913-020-06049-w

- France, E.F., Wells, M., Lang, H. et al. Why, when and how to update a meta-ethnography qualitative synthesis . Syst Rev 5, 44 (2016). https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.vt.edu/10.1186/s13643-016-0218-4

- Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography . SAGE Publications, Inc. https://dx. doi. org/10.4135/9781412985000

- Barnett-Page, E., Thomas, J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review . BMC Med Res Methodoly 9, 59 (2009). https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.vt.edu/10.1186/1471-2288-9-59

- Flemming, K., & Noyes, J. (2021). Qualitative Evidence Synthesis: Where Are We at? International Journal of Qualitative Methods . https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406921993276

Meta-Analysis

- Presenting Results

- Alternative Quantitative Synthesis

Meta-analysis

“The statistical analysis of a large collection of analysis results from individual studies for the purpose of integrating the findings .” ( Glass, 1976 )

“A statistical analysis which combines the results of several independent studies considered by the analyst to be ‘combinable’. ” (Huque, 1988)

“Meta-analysis is the statistical combination of results from two or more separate studies .” (Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3, Chapter 10 )

The Cochrane Handbook ( Chapter 10.1 ) states:

"Do not start here!" ...results of meta-analyses can be very misleading if suitable attention has not been given to formulating the review question; specifying eligibility criteria; identifying and selecting studies; collecting appropriate data; considering risk of bias; planning intervention comparisons; and deciding what data would be meaningful to analyse.

Choosing to pursue a Meta-Analysis

Reasons to pursue a meta-analysis.

Meta-analyses are a desirable end-goal as a this kind of synthesis can:

- Increase statistical power / improve precision

- Result in a summary estimate of the direction and size of the effect or association

- Determine consistent across studies and explore why studies found different results

- Address questions that can’t be addressed by the individual studies (related to factors that differ across studies)

- Potentially resolve uncertainties if disagreement in literature and identify areas where evidence is insufficient

Reasons not to pursue a Meta-Analysis

Despite the appeal of the meta-analytic approach, it is vital that studies in the meta-analysis measure the same thing in the same way - that the studies themselves are reasonable to combine statistically .

According to Cochrane Chapter 12.1 , "Legitimate reasons [for not conducting a meta-analysis] include limited evidence ; incompletely reported outcome/effect estimates, or different effect measures used across studies; and bias in the evidence." Table 12.1.a describes scenarios that may preclude meta-analyses, with possible solutions

Likewise, a synthesis is only as good as the studies included . In other words, a meta-analysis cannot improve poor quality studies.

This is not a comprehensive list - as with any analysis, you'll need to select specific approaches based on the kind of data you have.

- How you will group data for your synthesis and how grouping decisions are made , is an important consideration prior to starting the synthesis.

- Effect size measures must be comparable across included studies and/or computable given the information available in the primary studies. For example, in a review of weight loss studies, you may convert all effects to pounds of lost weight.

- Fixed-Effects: "assumes (1) all studies are measuring the same common (true) effect size (why we call it fixed), [and] (2) the observed results would be identical expect for random (sampling error)" ( Borenstein, 2009 )

- Random-Effects: "assumes (1) there are multiple population effects that the studies are estimating - different effect sizes underlying different studies, [and] (2) variability between effect sizes is due to sampling error + variability in population of effects" ( Borenstein, 2009 )

- There are some additional analyses you'll need to run to determine heterogeneity (how different studies are from each other). A sensitivity analysis or meta-regression is used to evaluate the effects of including or excluding certain groups of studies in your analysis, for example studies rated as low quality or high-risk of bias during the critical appraisal. You can also consider publication bias in your sample using a funnel plot (although there are valid critiques of the reliability of this practice).

- Glass, Gene V. “ Primary, Secondary, and Meta-Analysis of Research .” Educational Researcher , vol. 5, no. 10, 1976, pp. 3–8, https://doi.org/10.2307/1174772.

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to Meta-Analysis . John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470743386

- Pigott, T. D., & Polanin, J. R. (2020). Methodological Guidance Paper: High-Quality Meta-Analysis in a Systematic Review . Review of Educational Research , 90 (1), 24–46. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319877153

Tools for Meta-Analyses

Several tools exist for running your own meta-analyses. If you need further support, check out the help tab in this box.

Graphical User Interface (no programming required)

- RevMan | Developed by the Cochrane Collaboration; good for beginners

- PyMeta | Built from PythonMeta package for command line interface in python

- Comprehensive Meta-Analysis | fee-based

- MedCalc | fee-based

Command Line Interface (programming required)

- Metafor | R package; introduction from creator, Wolfgang Viechtbauer

- xmeta | R package; toolbox for multivariate meta-analyses

- PythonMeta | Python package; graphical interface available as PyMeta

- Polanin, J. R., Hennessy, E. A., & Tanner-Smith, E. E. (2017). A Review of Meta-Analysis Packages in R . Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics , 42 (2), 206–242. https://doi.org/10.3102/1076998616674315

- Video for using R for Meta package

Present Meta-Analysis Results

A meta-analysis is most commonly presented as a Forest Plot.

Forest Plot

If you are new to the concept of forest plots, check out Dr. Terry Shaneyfelt from UAB School of Medicine How to interpret a forest plot .

Alternative Quantitative Synthesis Methods

According to Cochrane Chapter 9.5 , "There are circumstances under which a meta-analysis is not possible, however, and other statistical synthesis methods might be considered, so as to make best use of the available data."

Table 9.5.a from the Cochrane Handbook , represented below, outlines some alternative synthesis method (and one summary method in the first row).

While the Evidence Synthesis Services (ESS) team at the University Libraries is available to support the other stages of a systematic review and/or meta-analysis,

we recommend reaching out to the Statistical Applications and Innovations Group (SAIG) for support in the statistical synthesis / meta-analysis.

Methodological Guidance

- Health Sciences

- Animal, Food Sciences

- Social Sciences

- Environmental Sciences

Cochrane Handbook - Part 1: About Cochrane Reviews

Chapter III : Reporting the Review (specifically part III.III ); Note: if you are not conducting a Cochrane Review, use this resource as a guidepost

Cochrane Handbook - Part 2: Core Methods

Chapter 9 : Summarizing study characteristics and preparing for synthesis

- 9.2 A general framework for synthesis

- 9.3 Preliminary steps of a synthesis

- 9.4 Checking data before synthesis

- 9.5 Types of synthesis

Chapter 10 : Analyzing data and undertaking meta-analyses

- 10.1 Do not start here!

- 10.2 Introduction to meta-analysis

- 10.3 A generic inverse-variance approach to meta-analysis

- 10.4 Meta-analysis of dichotomous outcomes

- 10.5 Meta-analysis of continuous outcomes

- 10.6 Combining dichotomous and continuous outcomes

- 10.7 Meta-analysis of ordinal outcomes and measurement scales

- 10.8 Meta-analysis of counts and rates

- 10.9 Meta-analysis of time-to-event outcomes

- 10.10 Heterogeneity

- 10.11 Investing heterogeneity

- 10.12 Missing data

- 10.13 Bayesian approaches to meta-analysis

- 10.14 Sensitivity analyses

- 10.S1 Supplementary material: Statistical algorithms in Review Manager 5.1

Chapter 12 : Synthesizing and presenting findings using other methods

- 12.1 Why a meta-analysis of effect estimates may not be possible

- 12.2 Statistical synthesis when meta-analysis of effect estimates is not possible

- 12.3 Visual display and presentation of the data

Chapter 13 : Assessing risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis

- 13.2 Minimizing risk of bias due to missing results

- 13.3 A framework for assessing risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis

Chapter 15: Interpreting results and drawing conclusions

- 15.2 Issues of indirectness and applicability

- 15.3 Interpreting results of statistical analyses

- 15.4 Interpreting results from dichotomous outcomes

- 15.5 Interpreting results from continuous outcomes (including standardized mean differences)

- 15.6 Drawing conclusions

Cochrane Handbook - Part 3: Specific Perspectives in Reviews

Chapter 21 : Qualitative Evidence

- 21.2 Designs for synthesizing and integrating qualitative evidence with intervention reviews

- 21.3 Defining qualitative evidence and studies

- 21.4 Planning qualitative evidence synthesis linked to an intervention review

- 21.5 Question development

- 21.13 Methods for integrating the qualitative evidence synthesis with an intervention review

SYREAF Tutorials

Step 5 . data synthesis.

Conducting systematic reviews of intervention questions III: Synthesizing data from intervention studies using meta-analysis. O’Connor AM, Sargeant JM, Wang C. Zoonoses Public Health. 2014 Jun;61 Suppl 1:52-63. doi: 10.1111/zph.12123. PMID: 24905996

Meta-analyses including data from observational studies. O’Connor AM, Sargeant JM. Prev Vet Med. 2014 Feb 15;113(3):313-22. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2013.10.017. Epub 2013 Oct 31. PMID: 24268538

Step 6. Presenting the results & Step 7. Reaching a conclusion

Conducting systematic reviews of intervention questions II: Relevance screening, data extraction, assessing risk of bias, presenting the results and interpreting the findings. Sargeant JM, O’Connor AM. Zoonoses Public Health. 2014 Jun;61 Suppl 1:39-51. doi: 10.1111/zph.12124. PMID: 24905995

Campbell - MECCIR

C59. Addressing risk of bias / study quality in the synthesis ( review / final manuscript )

C60 . Incorporating assessments of risk of bias ( review / final manuscript )

C61. Combining different scales ( review / final manuscript )

C62. Ensuring meta-analyses are meaningful ( review / final manuscript )

C63. Assessing statistical heterogeneity ( protocol & review / final manuscript )

C64. Addressing missing outcome data ( review / final manuscript )

C65. Addressing skewed data ( review / final manuscript )

C66. Addressing studies with more than two groups ( protocol & review / final manuscript )

C67. Comparing subgroups ( protocol & review / final manuscript )

C68. Interpreting subgroup analyses ( protocol & review / final manuscript )

C69. Considering statistical heterogeneity when interpreting the results ( review / final manuscript )

C70. Addressing non-standard designs ( protocol & review / final manuscript )

C71. Conducting sensitivity analysis ( protocol & review / final manuscript )

C72. Interpreting results ( review / final manuscript )

C73. Investigating reporting biases ( review / final manuscript )

C77. Formulating implications for practice ( review / final manuscript )

C78. Avoiding recommendations ( review / final manuscript )

C79. Formulating implications for research ( review / final manuscript )

CEE - Guidelines and Standards for Evidence synthesis in Environmental Management

Section 9. data synthesis.

CEE Standards for conduct and reporting

9.1 Systematic Reviews

9.1.1 Narrative Synthesis

9.1.2 Quantitative Data Synthesis

9.1.3 Qualitative Data Synthesis

Section 10. Interpreting findings and reporting conduct

10.1 The interpretation of evidence syntheses

10.2 Reporting conduct of evidence synthesis

10.3 Reporting findings of evidence syntheses

Reporting in Protocol and Final Manuscript

- Final Manuscript

In the Protocol | PRISMA-P

Data synthesis (item 15), qualitative synthesis only.

If quantitative synthesis is not appropriate, describe the type of summary planned (Item 15d)

all of the above plus:

Describe criteria under which study data will be quantitatively synthesised (Item 15a) ...quantitative synthesis, describe planned summary measures , methods of handling data and methods of combining data from studies , including any planned exploration of consistency (such as I2 , Kendall’s τ) (Item 15b) ...describe any proposed additional analyses (such as sensitivity or subgroup analyses, meta-regression) (Item 15c)

In the Final Manuscript | PRISMA

Synthesis methods (item 13; report in methods ), essential items.

- Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis . (Item 13a)

- Report any methods required to prepare the data collected from studies for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics or data conversions (Item 13b)

- Report chosen tabular structure(s) used to display results of individual studies and syntheses, along with details of the data presented (Item 13c)

- Report chosen graphical methods used to visually display results of individual studies and syntheses (Item 13c)

- If it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis, describe and justify the synthesis methods ...or summary approach used (Item 13d)

- If a planned synthesis was not considered possible or appropriate, report this and the reason for that decision (Item 13d)

Additional Items

- If studies are ordered or grouped within tables or graphs based on study characteristics (such as by size of the study effect, year of publication), consider reporting the basis for the chosen ordering/grouping (Item 13c)

- If non-standard graphs were used, consider reporting the rationale for selecting the chosen graph (Item 13c)

Meta-Analysis (or other quantitative methods used)

- ...reference the software, packages, and version numbers used to implement synthesis methods (such as metan in Stata metafor (version 2.1-0) in R118) (Item 13d)

- the meta-analysis model (fixed-effect, fixed-effects, or random-effects) and provide rationale for the selected model.

- the method used (such as Mantel-Haenszel, inverse-variance).

- any methods used to identify or quantify statistical heterogeneity (such as visual inspection of results, a formal statistical test for heterogeneity, heterogeneity variance (τ2), inconsistency (such as I2), and prediction intervals)

- the between-study (heterogeneity) variance estimator used (such as DerSimonian and Laird, restricted maximum likelihood (REML)).

- the method used to calculate the confidence interval for the summary effect (such as Wald-type confidence interval, Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman)

- If a Bayesian approach to meta-analysis was used, describe the prior distributions about quantities of interest (such as intervention effect being analysed, amount of heterogeneity in results across studies) (Item 13d)

- If multiple effect estimates from a study were included in a meta-analysis...describe the method(s) used to model or account for the statistical dependency. .. (Item 13d)

- If methods were used to explore possible causes of statistical heterogeneity , specify the method used (such as subgroup analysis, meta-regression) (Item 13e)

- which factors were explored, levels of those factors, and which direction of effect modification was expected and why (where possible) (Item 13e)

- whether analyses were conducted using study-level variables (where each study is included in one subgroup only), within-study contrasts (where data on subsets of participants within a study are available, allowing the study to be included in more than one subgroup), or some combination of the above ( Item 13e)

- how subgroup effects were compared (such as statistical test for interaction for subgroup analyses) (Item 13e)

- If other methods were used to explore heterogeneity because data were not amenable to meta-analysis of effect estimates, describe the methods used (such as structuring tables to examine variation in results across studies based on subpopulation, key intervention components, or contextual factors) along with the factors and levels (Item 13e)

- If any analyses used to explore heterogeneity were not pre-specified, identify them as such (Item 13e)

- If sensitivity analyses were performed, provide d etails of each analysis (such as removal of studies at high risk of bias, use of an alternative meta-analysis model) (Item 13f)

- If any sensitivity analyses were not pre-specified , identify them as such (Item 13f)

If a random-effects meta-analysis model was used, consider specifying other details about the methods used, such as the method for calculating confidence limits for the heterogeneity variance (Item 13d)

Reporting Bias Assessment (Item 14; report in methods )

- Specify the methods ... used to assess the risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases).

- If risk of bias due to missing results was assessed using an existing tool, specify the methodological components/domains/items of the tool, and the process used to reach a judgment of overall risk of bias .

- If any adaptations to an existing tool to assess risk of bias due to missing results were made (such as omitting or modifying items), specify the adaptations.

- If a new tool to assess risk of bias due to missing results was developed for use in the review, describe the content of the tool and make it publicly accessible.

- Report how many reviewers assessed risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis, whether multiple reviewers worked independently, and any processes used to resolve disagreements between assessors.

- Report any processes used to obtain or confirm relevant information from study investigators.

- If an automation tool was used to assess risk of bias due to missing results, report how the tool was used , how the tool was trained , and details on the tool’s performance and internal validation

Results of Synthesis (Item 20; report in results )

- Provide a brief summary of the characteristics and risk of bias among studies contributing to each synthesis (meta-analysis or other). The summary should focus only on study characteristics that help in interpreting the results (especially those that suggest the evidence addresses only a restricted part of the review question, or indirectly addresses the question). If the same set of studies contribute to more than one synthesis, or if the same risk of bias issues are relevant across studies for different syntheses, such a summary need be provided once only (Item 20a)

- Indicate which studies were included in each synthesis (such as by listing each study in a forest plot or table or citing studies in the text) (Item 20a)

- Report results of all statistical syntheses described in the protocol and all syntheses conducted that were not pre-specified (Item 20b)

Meta-Analysis (or other quantitative methods used)

- the summary estimate and its precision (such as standard error or 95% confidence/credible interval).

- measures of statistical heterogeneity (such as τ2, I2, prediction interval).

- If other statistical synthesis methods were used (such as summarising effect estimates, combining P values), report the synthesised result and a measure of precision (or equivalent information, for example, the number of studies and total sample size) (Item 20b)

- If the statistical synthesis method does not yield an estimate of effect (such as when P values are combined), report the relevant statistics (such as P value from the statistical test), along with an interpretation of the result that is consistent with the question addressed by the synthesis method (for example, “There was strong evidence of benefit of the intervention in at least one study (P < 0.001, 10 studies)” when P values have been combined) (Item 20b)

- If comparing groups , describe the direction of effect (such as fewer events in the intervention group, or higher pain in the comparator group) (Item 20b)

- If synthesising mean differences , specify for each synthesis, where applicable, the unit of measurement (such as kilograms or pounds for weight), the upper and lower limits of the measurement scale (for example, anchors range from 0 to 10), direction of benefit (for example, higher scores denote higher severity of pain), and the minimally important difference , if known. If synthesising standardised mean differences and the effect estimate is being re-expressed to a particular instrument, details of the instrument, as per the mean difference, should be reported (Item 20b)

- present results regardless of the statistical significance, magnitude, or direction of effect modification (Item 20c)

- identify the studies contributing to each subgroup (Item 20c)

- report results with due consideration to the observational nature of the analysis and risk of confounding due to other factors (Item 20c)

- If subgroup analysis was conducted, report for each analysis the exact P value for a test for interaction as well as, within each subgroup, the summary estimates , their precision (such as standard error or 95% confidence/credible interval) and measures of heterogeneity . Results from subgroup analyses might usefully be presented graphically (Item 20c)

- If meta-regression was conducted, report for each analysis the exact P value for the regression coefficient and its precision (Item 20c)

- If informal methods (that is, those that do not involve a formal statistical test) were used to investigate heterogeneity —which may arise particularly when the data are not amenable to meta-analysis— describe the results observed . For example, present a table that groups study results by dose or overall risk of bias and comment on any patterns observed (Item 20c)

- report the results for each sensitivity analysis (Item 20d)

- comment on how robust the main analysis was given the results of all corresponding sensitivity analyses (Item 20d)

- If subgroup analysis was conducted, consider presenting the estimate for the difference between subgroups and its precision (Item 20c)

- If meta-regression was conducted, consider presenting a meta-regression scatterplot with the study effect estimates plotted against the potential effect modifier (Item 20c)

- the summary effect estimate , a measure of precision (and potentially other relevant statistics, for example, I2 statistic) and contributing studies for the original meta-analysis;

- the same information for the sensitivity analysis ; and

- details of the original and sensitivity analysis assumptions (Item 20d)

- presenting results of sensitivity analyses visually using forest plots (Item 20d)

Reporting Biases (Item 21; report in results )

- Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed.

- If a tool was used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis, present responses to questions in the tool, judgments about risk of bias, and any i nformation used to support such judgments to help readers understand why particular judgments were made.

- If a funnel plot was generated to evaluate small-study effects (one cause of which is reporting biases), present the plot and specify the effect estimate and measure of precision used in the plot (presented typically on the horizontal axis and vertical axis respectively). If a contour-enhanced funnel plot was generated, specify the “milestones” of statistical significance that the plotted contour lines represent (P=0.01, 0.05, 0.1, etc).

- If a test for funnel plot asymmetry was used, report the exact P value observed for the test and potentially other relevant statistics, such as the standardised normal deviate, from which the P value is derived.

- If any sensitivity analyses seeking to explore the potential impact of missing results on the synthesis were conducted, present results of each analysis (see item #20d), compare them with results of the primary analysis, and report results with due consideration of the limitations of the statistical method.

- If studies were assessed for selective non-reporting of results by comparing outcomes and analyses pre-specified in study registers, protocols, and statistical analysis plans with results that were available in study reports, consider presenting a matrix (with rows as studies and columns as syntheses) to present the availability of study results.

- If an assessment of selective non-reporting of results reveals that some studies are missing from the synthesis, consider displaying the studies with missing results underneath a forest plot or including a table with the available study results (for example, see forest plot in Page et al)

Discussion (Item 23)

- Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence (Item 23a)

- Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review (Item 23b)

- Discuss any limitations of the review processes used and comment on the potential impact of each limitation (Item 23c)

- Discuss implications of the results for practice and policy (Item 23d)

- Make explicit recommendations for future research (Item 23d)

- << Previous: Data Extraction

- Next: Assess Certainty >>

- Last Updated: Apr 12, 2024 12:41 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.vt.edu/SRMA

- Langson Library

- Science Library

- Grunigen Medical Library

- Law Library

- Connect From Off-Campus

- Accessibility

- Gateway Study Center

Email this link

Systematic reviews & evidence synthesis methods.

- Schedule a Consultation / Meet our Team

- What is Evidence Synthesis?

- Types of Evidence Synthesis

- Evidence Synthesis Across Disciplines

- Finding and Appraising Existing Systematic Reviews

- 1. Develop a Protocol

- 2. Draft your Research Question

- 3. Select Databases

- 4. Select Grey Literature Sources

- 5. Write a Search Strategy

- 6. Register a Protocol

- 7. Translate Search Strategies

- 8. Citation Management

- 9. Article Screening

- 10. Risk of Bias Assessment

- 11. Data Extraction

- 12. Synthesize, Map, or Describe the Results

- Open Access Evidence Synthesis Resources

Requirements for the Systematic Review Process

Systematic reviews are a huge endeavor, so here are a few requirements if you are thinking of employing this methodology:

- Systematic reviews require time . 12-24 months is usual from conception to submission.

- Systematic reviews require a team . Four (4) or more team members are recommended. A principal investigator, a second investigator, a librarian, and someone well-versed in statistics forms the basic team. Ideally the team might have another investigator and someone to coordinate all the moving pieces. Smaller teams are possible, three is the realistic minimum . Two investigators each wearing more than one hat and one librarian. Sometimes an investigator has the time and energy to coordinate. Occasionally one of the investigators is also a statistical guru.

- * An exception to this rule is an "empty review," which retrieves zero studies that meet the inclusion criteria. Empty reviews are relatively uncommon, but may be used to demonstrate a need for future research in an area. However, an empty review may instead indicate that the research question was defined too narrowly.

Why do a systematic review? A well done systematic review is a major contribution to the literature. But the requirements in time and effort are massive. Cochrane estimates one year from conception to completion. This does not including time for review, revision and publication. You need to assemble a team and they need to commit for the duration.

A good place to start is with a consultation with a librarian. Visit the " Schedule a Consultation " page to learn why.

- << Previous: Finding and Appraising Existing Systematic Reviews

- Next: 1. Develop a Protocol >>

- Last Updated: Apr 22, 2024 7:04 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uci.edu/evidence-synthesis

Off-campus? Please use the Software VPN and choose the group UCIFull to access licensed content. For more information, please Click here

Software VPN is not available for guests, so they may not have access to some content when connecting from off-campus.

Systematic Reviews and Meta Analysis

- Getting Started

- Guides and Standards

- Review Protocols

- Databases and Sources

- Randomized Controlled Trials

- Controlled Clinical Trials

- Observational Designs

- Tests of Diagnostic Accuracy

- Software and Tools

- Where do I get all those articles?

- Collaborations

- EPI 233/528

- Countway Mediated Search

- Risk of Bias (RoB)

Systematic review Q & A

What is a systematic review.

A systematic review is guided filtering and synthesis of all available evidence addressing a specific, focused research question, generally about a specific intervention or exposure. The use of standardized, systematic methods and pre-selected eligibility criteria reduce the risk of bias in identifying, selecting and analyzing relevant studies. A well-designed systematic review includes clear objectives, pre-selected criteria for identifying eligible studies, an explicit methodology, a thorough and reproducible search of the literature, an assessment of the validity or risk of bias of each included study, and a systematic synthesis, analysis and presentation of the findings of the included studies. A systematic review may include a meta-analysis.

For details about carrying out systematic reviews, see the Guides and Standards section of this guide.

Is my research topic appropriate for systematic review methods?

A systematic review is best deployed to test a specific hypothesis about a healthcare or public health intervention or exposure. By focusing on a single intervention or a few specific interventions for a particular condition, the investigator can ensure a manageable results set. Moreover, examining a single or small set of related interventions, exposures, or outcomes, will simplify the assessment of studies and the synthesis of the findings.

Systematic reviews are poor tools for hypothesis generation: for instance, to determine what interventions have been used to increase the awareness and acceptability of a vaccine or to investigate the ways that predictive analytics have been used in health care management. In the first case, we don't know what interventions to search for and so have to screen all the articles about awareness and acceptability. In the second, there is no agreed on set of methods that make up predictive analytics, and health care management is far too broad. The search will necessarily be incomplete, vague and very large all at the same time. In most cases, reviews without clearly and exactly specified populations, interventions, exposures, and outcomes will produce results sets that quickly outstrip the resources of a small team and offer no consistent way to assess and synthesize findings from the studies that are identified.

If not a systematic review, then what?

You might consider performing a scoping review . This framework allows iterative searching over a reduced number of data sources and no requirement to assess individual studies for risk of bias. The framework includes built-in mechanisms to adjust the analysis as the work progresses and more is learned about the topic. A scoping review won't help you limit the number of records you'll need to screen (broad questions lead to large results sets) but may give you means of dealing with a large set of results.

This tool can help you decide what kind of review is right for your question.

Can my student complete a systematic review during her summer project?

Probably not. Systematic reviews are a lot of work. Including creating the protocol, building and running a quality search, collecting all the papers, evaluating the studies that meet the inclusion criteria and extracting and analyzing the summary data, a well done review can require dozens to hundreds of hours of work that can span several months. Moreover, a systematic review requires subject expertise, statistical support and a librarian to help design and run the search. Be aware that librarians sometimes have queues for their search time. It may take several weeks to complete and run a search. Moreover, all guidelines for carrying out systematic reviews recommend that at least two subject experts screen the studies identified in the search. The first round of screening can consume 1 hour per screener for every 100-200 records. A systematic review is a labor-intensive team effort.

How can I know if my topic has been been reviewed already?

Before starting out on a systematic review, check to see if someone has done it already. In PubMed you can use the systematic review subset to limit to a broad group of papers that is enriched for systematic reviews. You can invoke the subset by selecting if from the Article Types filters to the left of your PubMed results, or you can append AND systematic[sb] to your search. For example:

"neoadjuvant chemotherapy" AND systematic[sb]

The systematic review subset is very noisy, however. To quickly focus on systematic reviews (knowing that you may be missing some), simply search for the word systematic in the title:

"neoadjuvant chemotherapy" AND systematic[ti]

Any PRISMA-compliant systematic review will be captured by this method since including the words "systematic review" in the title is a requirement of the PRISMA checklist. Cochrane systematic reviews do not include 'systematic' in the title, however. It's worth checking the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews independently.

You can also search for protocols that will indicate that another group has set out on a similar project. Many investigators will register their protocols in PROSPERO , a registry of review protocols. Other published protocols as well as Cochrane Review protocols appear in the Cochrane Methodology Register, a part of the Cochrane Library .

- Next: Guides and Standards >>

- Last Updated: Feb 26, 2024 3:17 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/meta-analysis

Systematic Review and Evidence Synthesis

Acknowledgements.

This guide is directly informed by and selectively reuses, with permission, content from:

- Systematic Reviews, Scoping Reviews, and other Knowledge Syntheses by Genevieve Gore and Jill Boruff, McGill University (CC-BY-NC-SA)

- A Guide to Evidence Synthesis , Cornell University Library Evidence Synthesis Service

Primary University of Minnesota Libraries authors are: Meghan Lafferty, Scott Marsalis, & Erin Reardon

Last updated: September 2022

Guidance by Methodology

- PRISMA reporting guidelines

- Systematic review guidance

- Meta-analysis guidance

- Scoping review guidance

- Evidence and gap map guidance

- Rapid review guidance

- Qualitative meta-synthesis guidance

- Umbrella review guidance

PRISMA Statement introduction

Prisma statement introduction.

The PRISMA statement is the main reporting standard for evidence synthesis. The acronym refers to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. In addition to the main PRISMA statement there are many extensions for other methodologies; these are notated by a suffix. Please refer to www.prisma-statement.org for the most recent information and updates and a complete list of extensions. We list only the most frequently used on this page.

When using PRISMA or its extensions it is important to carefully read the key documents. Typically there will be a paper introducing the standard and its development, an "E&E" or "Explanation & Elaboration" paper which explains the components of the statement and gives examples, and a checklist, which helps the authors make sure they fully comply in reporting their study.

One of the most familiar aspects of PRISMA is the flow diagram which summarized the flow of information through the process, from record identification through screening and synthesis. Only including the flow diagram is not enough to comply with PRISMA or its extensions.

PRISMA Key Documents

- PRISMA 2020 Checklist

- PRISMA 2020 flow diagram

- PRISMA 2020 Statement

- PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration

PRISMA Extensions

- PRISMA for Abstracts

- PRISMA for Acupuncture

- PRISMA for Diagnostic Test Accuracy

- PRISMA for EcoEvo

- PRISMA Equity

- PRISMA Harms (for reviews including Harm outcomes)

- PRISMA Individual Patient Data

- PRISMA for Network Meta-Analyses

- PRISMA for Protocols

- PRISMA for Scoping Reviews

- PRISMA for Searching

- Extensions in development

Systematic Review Guidance

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions

Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews

An Introduction to Systematic Reviews

JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis

Meta-Analysis Guidance

Research synthesis and meta-analysis : a step-by-step approach (Fifth edition.) Cooper. (2017). Research synthesis and meta-analysis : a step-by-step approach (Fifth edition.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

Scoping Review Guidance

- JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis - Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews

- Tricco, A., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., . . . Straus, S. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467-473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

- Arksey, H. & O'Malley, L. (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8:1, 19-32, DOI: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Peters, M.D., Marnie, C., Tricco, A.C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C.M. and Khalil, H., (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), pp.2119-2126.

- Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x (Open access)

Evidence & Gap Map Guidance