This website uses cookies to ensure the best user experience. Privacy & Cookies Notice Accept Cookies

Manage My Cookies

Manage Cookie Preferences

Confirm My Selections

- Monetary Policy

- Health Care

- Climate Change

- Artificial Intelligence

- All Chicago Booth Review Topics

Are We Really More Productive Working from Home?

Data from the pandemic can guide organizations struggling to reimagine the new office..

- By Rebecca Stropoli

- August 18, 2021

- CBR - Economics

- Share This Page

Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg isn’t your typical office worker. He was No. 3 on the 2020 Forbes list of the richest Americans, with a net worth of $125 billion, give or take. But there’s at least one thing Zuckerberg has in common with many other workers: he seems to like working from home. In an internal memo, which made its way to the Wall Street Journal , as Facebook announced plans to offer increased flexibility to employees, Zuckerberg explained that he would work remotely for at least half the year.

“Working remotely has given me more space for long-term thinking and helped me spend more time with my family, which has made me happier and more productive at work,” Zuckerberg wrote. He has also said that he expects about half of Facebook’s employees to be fully remote within the next decade.

The coronavirus pandemic continues to rage in many countries, and variants are complicating the picture, but in some parts of the world, including the United States, people are desperate for life to return to normal—everywhere but the office. After more than a year at home, some employees are keen to return to their workplaces and colleagues. Many others are less eager to do so, even quitting their jobs to avoid going back. Somewhere between their bedrooms and kitchens, they have established new models of work-life balance they are loath to give up.

This has left some companies trying to recreate their work policies, determining how best to handle a workforce that in many cases is demanding more flexibility. Some, such as Facebook, Twitter, and Spotify, are leaning into remote work. Others, such as JPMorgan Chase and Goldman Sachs, are reverting to the tried-and-true office environment, calling everyone back in. Goldman’s CEO David Solomon, in February, called working from home an “aberration that we’re going to correct as quickly as possible.” And JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon said of exclusively remote work: “It doesn’t work for those who want to hustle. It doesn’t work for spontaneous idea generation. It doesn’t work for culture.”

This pivotal feature of pandemic life has accelerated a long-running debate: What do employers and employees lose and gain through remote work? In which setting—the office or the home—are employees more productive? Some research indicates that working from home can boost productivity and that companies offering more flexibility will be best positioned for success. But this giant, forced experiment has only just begun.

An accelerated debate

A persistent sticking point in this debate has been productivity. Back in 2001, a group of researchers from the Human-Computer Interaction Institute at Carnegie Mellon, led by Robert E. Kraut , wrote that “collaboration at a distance remains substantially harder to accomplish than collaboration when members of a work group are collocated.” Two decades later, this statement remains part of today’s discussion.

However, well before Zoom, which came on the scene in 2011, or even Skype, which launched in 2003, the researchers acknowledged some of the potential benefits of remote work, allowing that “dependence on physical proximity imposes substantial costs as well, and may undercut successful collaboration.” For one, they noted, email, answering machines, and computer bulletin boards could help eliminate the inconvenience of organizing in-person meetings with multiple people at the same time.

Two decades later, remote-work technology is far more developed. Data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics indicate that, even in pre-pandemic 2019, more than 26 million Americans—approximately 16 percent of the total US workforce—worked remotely on an average day. The Pew Research Center put that pre-pandemic number at 20 percent, and in December 2020 reported that 71 percent of workers whose responsibilities allowed them to work from home were doing so all or most of the time.

The sentiment toward and effectiveness of remote work depend on the industry involved. It makes sense that executives working in and promoting social media are comfortable connecting with others online, while those in industries in which deals are typically closed with handshakes in a conference room, or over drinks at dinner, don’t necessarily feel the same. But data indicate that preferences and productivity are shaped by factors beyond a person’s line of work.

The productivity paradigm

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Stanford’s Nicholas Bloom was bullish on work-from-home trends. His 2015 study, for one—with James Liang , John Roberts , and Zhichun Jenny Ying , all then at Stanford—finds a 13 percent increase in productivity among remotely working call-center employees at a Chinese travel agency.

But in the early days of the pandemic, Bloom was less optimistic about remote work. “We are home working alongside our kids, in unsuitable spaces, with no choice and no in-office days,” Bloom told a Stanford publication in March 2020. “This will create a productivity disaster for firms.”

To test that thesis, Jose Maria Barrero of the Mexico Autonomous Institute of Technology, Bloom, and Chicago Booth’s Steven J. Davis launched a monthly survey of US workers in May 2020, tracking more than 30,000 workers aged 20–64 who earned at least $20,000 per year in 2019.

Companies that offer more flexibility in work arrangements may have the best chance of attracting top talent at the best price.

The survey measured the incidence of working from home as the pandemic continued, focusing on how a more permanent shift to remote work might affect not only productivity but also overall employee well-being. It also examined factors including how work from home would affect spending and revenues in major urban centers. In addition to the survey, the researchers drew on informal conversations with dozens of US business executives. They are publishing the results of the survey and related research at wfhresearch.com .

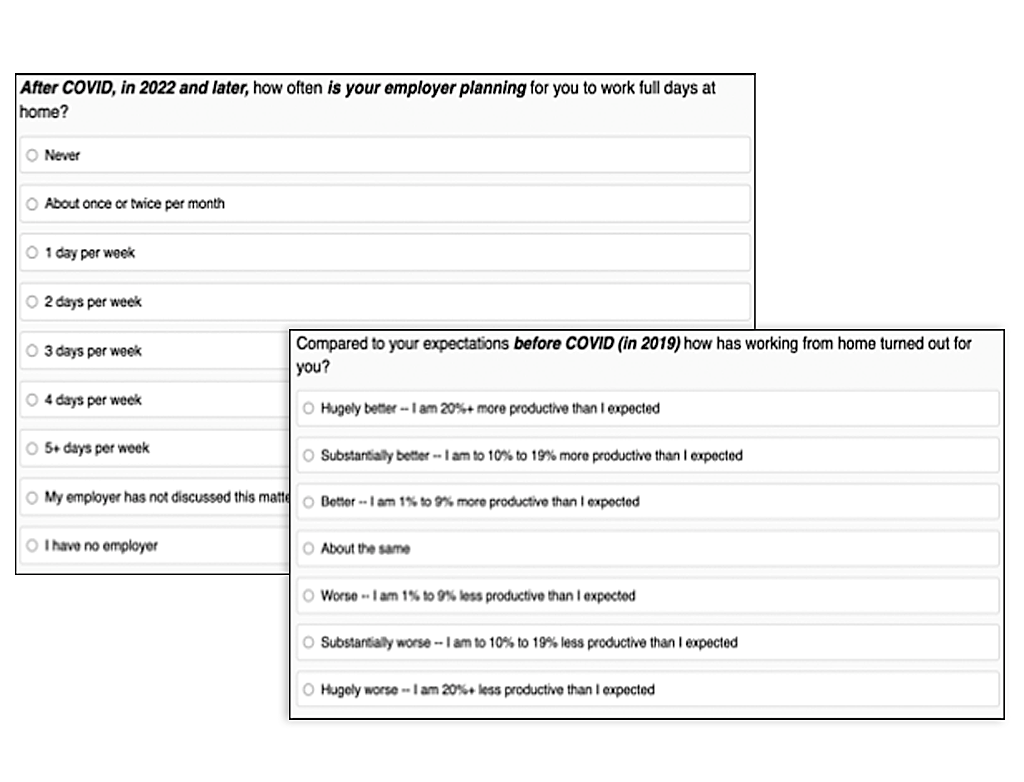

In an analysis of the data collected through March 2021, they find that nearly six out of 10 workers reported being more productive working from home than they expected to be, compared with 14 percent who said they got less done. On average, respondents’ productivity at home was 7 percent higher than they expected. Forty percent of workers reported they were more productive at home during the pandemic than they had been when in the office, and only 15 percent said the opposite was true. The researchers argue that the work-from-home trend is here to stay, and they calculate that these working arrangements will increase overall worker productivity in the US by 5 percent as compared with the pre-pandemic economy.

“Working from home under the pandemic has been far more productive than I or pretty much anyone else predicted,” Bloom says.

No commute, and fewer hours worked

Some workers arguing in favor of flexibility might say they’re more efficient at home away from chatty colleagues and the other distractions of an office, and that may be true. But above all, the increased productivity comes from saving transit time, an effect overlooked by standard productivity calculations. “Three-quarters or more of the productivity gains that we find are coming from a reduction in commuting time,” Davis says. Eliminate commuting as a factor, and the researchers project only a 1 percent productivity boost in the postpandemic work-from-home environment, as compared with before.

It makes sense that standard statistics miss the impact of commutes, Davis explains. Ordinarily, commuting time generally doesn’t shift significantly in the aggregate. But much like rare power outages in Manhattan have made it possible for New Yorkers to suddenly see the nighttime stars, the dramatic work-from-home shift that occurred during the pandemic made it possible to recognize the impact traveling to and from an office had on productivity.

Before the pandemic, US workers were commuting an average of 54 minutes daily, according to Barrero, Bloom, and Davis. In the aggregate, the researchers say, the pandemic-induced shift to remote work meant 62.5 million fewer commuting hours per workday.

People who worked from home spent an average of 35 percent of saved commuting time on their jobs, the researchers find. They devoted the rest to other activities, including household chores, childcare, leisure activities such as watching movies and TV, outdoor exercise, and even second jobs.

Infographic: People want working from home to stick after the pandemic subsides

With widespread lockdowns abruptly forcing businesses to halt nonessential, in-person activity, the COVID-19 pandemic drove a mass social experiment in working from home, according to Jose Maria Barrero of the Mexico Autonomous Institute of Technology, Stanford’s Nicholas Bloom , and Chicago Booth’s Steven J. Davis . The researchers launched a survey of US workers, starting in May 2020 and continuing in waves for more than a year since, to capture a range of information including workers’ attitudes about their new remote arrangements.

Read more >>

Aside from commuting less, remote workers may also be sleeping more efficiently, another phenomenon that could feed into productivity. On days they worked remotely, people rose about 30 minutes later than on-site workers did, according to pre-pandemic research by Sabrina Wulff Pabilonia of the US Bureau of Labor Statistics and SUNY Empire’s Victoria Vernon . Both groups worked the same number of hours and slept about the same amount each night, so it’s most likely that “working from home permits a more comfortable personal sleep schedule,” says Vernon. “Teleworkers who spend less time commuting may be happier and less tired, and therefore more productive,” write the researchers, who analyzed BLS data from 2017 to 2018.

While remote employees gained back commuting time during the pandemic, they also worked fewer hours, note Barrero, Bloom, and Davis. Hours on the job averaged about 32 per week, compared with 36 pre-pandemic, although the work time stretched past traditional office hours. “Respondents may devote a few more minutes in the morning to chores and childcare, while still devoting about a third of their old commuting time slot to their primary job. At the end of the day, they might end somewhat early and turn on the TV. They might interrupt TV time to respond to a late afternoon or early evening work request,” the researchers explain.

This interpretation, they write, is consistent with media reports that employees worked longer hours from home during the pandemic but with the added flexibility to interrupt the working day. Yet, according to the survey, this does not have a negative overall effect on productivity, contradicting one outdated stereotype of a remote worker eating bonbons, watching TV, and getting no work done.

Remote-work technology goes mainstream

The widespread implementation of remote-working technology, a defining feature of the pandemic, is another important factor for productivity. This technology will boost work-from-home productivity by 46 percent by the end of the pandemic, relative to the pre-pandemic situation, according to a model developed by Rutgers’s Morris A. Davis , University of North Carolina’s Andra C. Ghent , and University of Wisconsin’s Jesse M. Gregory . “While many home-office technologies have been around for a while, the technologies become much more useful after widespread adoption,” the researchers note.

There are significant costs to leaving the office, Rutgers’s Davis says, pointing to the loss of face-to-face interaction, among other things. “Working at home is always less productive than working at the office. Always,” he said on a June episode of the Freakonomics podcast.

One reason, he says , has to do with the function of cities as business centers. “Cities exist because, we think, the crowding of employment makes everyone more productive,” he explains. “This idea also applies to firms: a firm puts all workers on the same floor of a building, or all in the same suite rather than spread throughout a building, for reasons of efficiency. It is easier to communicate and share ideas with office mates, which leads to more productive outcomes.” While some employees are more productive at home, that’s not the case overall, according to the model, which after calibration “implies that the average high-skill worker is less productive at home than at the office, even postpandemic,” he says.

How remote work could change city centers

What will happen to urban business districts and the cities in which they are located in the age of increasing remote work?

About three-quarters of Fortune 500 CEOs expect to need less office space in the future, according to a May 2021 poll. In Manhattan, the overall office vacancy rate was at a multidecade high of 16 percent in the first quarter of 2021, according to real-estate services firm Cushman & Wakefield.

And yet Davis, Ghent, and Gregory’s model projects that after the pandemic winds down, highly skilled, college-educated workers will spend 30 percent of their time working from home, as opposed to 10 percent in prior times. While physical proximity may be superior, working from home is far more productive than it used to be. Had the pandemic hit in 1990, it would not have produced this rise in relative productivity, per the researchers’ model, because the technology available at the time was not sufficient to support remote work.

A June article in the MIT Technology Review by Stanford’s Erik Brynjolfsson and MIT postdoctoral scholar Georgios Petropoulos corroborates this view. Citing the 5.4 percent increase in US labor productivity in the first quarter of 2021, as reported by the BLS, the researchers attribute at least some of this to the rise of work-from-home technologies. The pandemic, they write, has “compressed a decade’s worth of digital innovation in areas like remote work into less than a year.” The biggest productivity impact of the pandemic will be realized in the longer run, as the work-from-home trend continues, they argue.

Lost ideas, longer hours?

Not all the research supports the idea that remote work increases productivity and decreases the number of hours workers spend on the job. Chicago Booth’s Michael Gibbs and University of Essex’s Friederike Mengel and Christoph Siemroth find contradictory evidence from a study of 10,000 high-skilled workers at a large Asian IT-services company.

The researchers used personnel and analytics data from before and during the coronavirus work-from-home period. The company provided a rich data set for these 10,000 employees, who moved to 100 percent work from home in March 2020 and began returning to the office in late October.

Total hours worked during that time increased by approximately 30 percent, including an 18 percent rise in working beyond normal business hours, the researchers find. At the same time, however, average output—as measured by the company through setting work goals and tracking progress toward them—declined slightly. Time spent on coordination activities and meetings also increased, while uninterrupted work hours shrank. Additionally, employees spent less time networking and had fewer one-on-one meetings with their supervisors, find the researchers, adding that the increase in hours worked and the decline in productivity were more significant for employees with children at home. Weighing output against hours worked, the researchers conclude that productivity decreased by about 20 percent. They estimate that, even after accounting for the loss of commuting time, employees worked about a third of an hour per day more than they did at the office. “Of course, that time was spent in productive work instead of sitting in traffic, which is beneficial,” they acknowledge.

Regardless of what research establishes in the long run about productivity, many workers are already demanding flexibility in their schedules.

Overall, though, do workers with more flexibility work fewer hours (as Barrero, Bloom, and Davis find) or more (as at the Asian IT-services company)? It could take more data to answer this question. “I suspect that a high fraction of employees of all types, across the globe, value the flexibility, lack of a commute, and other aspects of work from home. This might bias survey respondents toward giving more positive answers to questions about their productivity,” says Gibbs.

The findings of his research do not entirely contradict those of Barrero, Bloom, and Davis, however. For one, Gibbs, Mengel, and Siemroth acknowledge that their study doesn’t necessarily reflect the remote-work model as it might look in postpandemic times, when employees are relieved of the weight of a massive global crisis. “While the average effect of working from home on productivity is negative in our study, this does not rule out that a ‘targeted working from home’ regime might be desirable,” they write.

Additionally, the research data are derived from a single company and may not be representative of the wider economy, although Gibbs notes that the IT company is one that should be able to optimize remote work. Most employees worked on company laptops, “and IT-related industries and occupations are usually at the top of lists of those areas most likely to be able to do WFH effectively.” Thus, he says, the findings may represent a cautionary note that remote work has costs and complexities worth addressing.

As he, Mengel, and Siemroth write, some predictions of work-from-home success may be overly optimistic, “perhaps because professionals engage in many tasks that require collaboration, communication, and innovation, which are more difficult to achieve with virtual, scheduled interactions.”

Attracting top talent

The focus on IT employees’ productivity, however, excludes issues such as worker morale and retention, Booth’s Davis notes. More generally, “the producer has to attract workers . . . and if workers really want to commute less, and they can save time on their end, and employers can figure out some way to accommodate that, they’re going to have more success with workers at a given wage cost.”

Companies that offer more flexibility in work arrangements may have the best chance of attracting top talent at the best price. The data from Barrero, Bloom, and Davis reveal that some workers are willing to take a sizable pay cut in exchange for the opportunity to work remotely two or three days a week. This may give threats from CEOs such as Morgan Stanley’s James Gorman—who said at the company’s US Financials, Payments & CRE conference in June, “If you want to get paid New York rates, you work in New York”—a bit less bite. Meanwhile, Duke PhD student John W. Barry , Cornell’s Murillo Campello , Duke’s John R. Graham , and Chicago Booth’s Yueran Ma find that companies offering flexibility are the ones most poised to grow.

Working policies may be shaped by employees’ preferences. Some workers still prefer working from the office; others prefer to stay working remotely; many would opt for a hybrid model, with some days in the office and some at home (as Amazon and other companies have introduced). As countries emerge from the pandemic and employers recalibrate, companies could bring back some employees and allow others to work from home. This should ultimately boost productivity, Booth’s Davis says.

Or they could allow some to work from far-flung locales. Harvard’s Prithwiraj Choudhury has long focused his research on working not just from home but “from anywhere.” This goes beyond the idea of employees working from their living room in the same city in which their company is located—instead, if they want to live across the country, or even in another country, they can do so without any concern about being near headquarters.

Does remote work promote equity?

At many companies, the future will involve remote work and more flexibility than before. That could be good for reducing the earnings gap between men and women—but only to a point.

“In my mind, there’s no question that it has to be a plus, on net,” says Harvard’s Claudia Goldin. Before the pandemic, many women deemphasized their careers when they started families, she says.

Research Choudhury conducted with Harvard PhD student Cirrus Foroughi and Northeastern University’s Barbara Larson analyzes a 2012 transition from a work-from-home to a work-from-anywhere model among patent examiners with the United States Patent and Trademark Office. The researchers exploited a natural experiment and estimate that there was a 4.4 percent increase in work output when the examiners transitioned from a work-from-home regime to the work-from-anywhere regime.

“Work from anywhere offers workers geographic flexibility and can help workers relocate to their preferred locations,” Choudhury says. “Workers could gain additional utility by relocating to a cheaper location, moving closer to family, or mitigating frictions around immigration or dual careers.”

He notes as well the potential advantages for companies that allow workers to be located anywhere across the globe. “In addition to benefits to workers and organizations, WFA might also help reverse talent flows from smaller towns to larger cities and from emerging markets,” he says. “This might lead to a more equitable distribution of talent across geographies.”

More data to come

It is still early to draw strong conclusions about the impact of remote work on productivity. People who were sent home to work because of the COVID-19 pandemic may have been more motivated than before to prove they were essential, says Booth’s Ayelet Fishbach, a social psychologist. Additionally, there were fewer distractions from the outside because of the broad shutdowns. “The world helped them stay motivated,” she says, adding that looking at such an atypical year may not tell us as much about the future as performing the same experiment in a typical year would.

Before the pandemic, workers who already knew they performed better in a remote-working lifestyle self-selected into it, if allowed. During the pandemic, shutdowns forced remote work on millions. An experiment that allowed for random selection would likely be more telling. “The work-from-home experience seems to be more positive than what people believed, but we still don’t have great data,” Fishbach says.

Adding to the less optimistic view of a work-from-home future, Booth’s Austan D. Goolsbee says that some long-term trends may challenge remote work. Since the 1980s, as the largest companies have gained market power, corporate profits have risen dramatically while the share of profits going to workers has dropped to record lows. “This divergence between productivity and pay may very well come to pass regarding time,” he told graduating Booth students at their convocation ceremony. Companies may try to claw back time from those who are remote, he says, by expecting employees to work for longer hours or during their off hours.

And author and behavioral scientist Jon Levy argues in the Boston Globe that having some people in the office and others at home runs counter to smooth organizational processes. To this, Bloom offers a potential solution: instead of letting employees pick their own remote workdays, employers should ensure all workers take remote days together and come into the office on the same days. This, he says, could help alleviate the challenges of managing a hybrid team and level the playing field, whereas a looser model could potentially hurt employees who might be more likely to choose working from home (such as mothers with young children) while elevating those who might find it easier to come into the office every day (such as single men).

Gibbs concurs, noting that companies using a hybrid model will have to find ways to make sure employees who should interact will be on campus simultaneously. “Managers may specify that the entire team meets in person every Monday morning, for example,” he says. “R&D groups may need to make sure that researchers are on campus at the same time, to spur unplanned interactions that sometimes lead to new ideas and innovations.”

Sentiments vary by location, industry, and culture. Japanese workers are reportedly still mostly opting to go to the office, even as the government promotes remote work. Among European executives, a whopping 88 percent reportedly disagree with the idea that remote work is as or more productive than working at the office.

Regardless of what research establishes in the long run about productivity, many workers are already demanding flexibility in their schedules. While only about 28 percent of US office workers were back onsite by June 2021, employees who had become used to more flexibility were demanding it remain. A May survey of 1,000 workers by Morning Consult on behalf of Bloomberg News finds that about half of millennial and Gen Z workers, and two-fifths of all workers, would consider quitting if their employers weren’t flexible about work-from-home policies. And additional research from Barrero, Bloom, and Davis finds that four in 10 Americans who currently work from home at least one day a week would look for another job if their employers told them to come back to the office full time. Additionally, most employees would look favorably upon a new job that offered the same pay as their current job along with the option to work from home two to three days a week.

The shift to remote work affects a significant slice of the US workforce. A study by Chicago Booth’s Jonathan Dingel and Brent Neiman finds that while the majority of all jobs in the US require appearing in person, more than a third can potentially be performed entirely remotely. Of these jobs, the majority—including many in engineering, computing, law, and finance—pay more than those that cannot be done at home, such as food service, construction, and building-maintenance jobs.

Barrero, Bloom, and Davis project that, postpandemic, Americans overall will work approximately 20 percent of full workdays from home, four times the pre-pandemic level. This would make remote work less an aberration than a new norm. As the pandemic has demonstrated, many workers can be both productive and get dinner started between meetings.

Works Cited

- Jose Maria Barrero, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis, “Why Working from Home Will Stick,” Working paper, April 2021.

- ———, “60 Million Fewer Commuting Hours per Day: How Americans Use Time Saved by Working from Home,” Working paper, September 2020.

- ———, “Let Me Work From Home Or I Will Find Another Job,” Working paper, July 2021.

- John W. Barry, Murillo Campello, John R. Graham, and Yueran Ma, “Corporate Flexibility in a Time of Crisis,” Working paper, February 2021.

- Nicholas Bloom, James Liang, John Roberts, and Zhichun Jenny Ying, “Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment,” Quarterly Journal of Economics , October 2015.

- Prithwiraj Choudhury, Cirrus Foroughi, and Barbara Larson, “Work-from-Anywhere: The Productivity Effects of Geographic Flexibility,” Strategic Management Journal , forthcoming.

- Morris A. Davis, Andra C. Ghent, and Jesse M. Gregory, “The Work-at-Home Technology Boon and Its Consequences,” Working paper, April 2021.

- Jonathan Dingel and Brent Neiman, “How Many Jobs Can Be Done at Home?” White paper, June 2020.

- Allison Dunatchik, Kathleen Gerson, Jennifer Glass, Jerry A. Jacobs, and Haley Stritzel, “Gender, Parenting, and the Rise of Remote Work during the Pandemic: Implications for Domestic Inequality in the United States,” Gender & Society , March 2021.

- Michael Gibbs, Friederike Mengel, and Christoph Siemroth, “Work from Home & Productivity: Evidence from Personnel & Analytics Data on IT Professionals,” Working paper, May 2021.

- Robert E. Kraut, Susan R. Fussell, Susan E. Brennan, and Jane Siegel, “Understanding Effects of Proximity on Collaboration: Implications for Technologies to Support Remote Collaborative Work,” in Distributed Work , eds. Pamela J. Hinds and Sara Kiesler, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002.

- Sabrina Wulff Pabilonia and Victoria Vernon, “Telework and Time Use in the United States,” Working paper, May 2020.

More from Chicago Booth Review

College bests benefits for injured workers.

In Denmark, those who picked education benefits over disability payments got back to work within seven years, and with a 25 percent raise.

If Big Tech Is a Problem, What’s the Solution?

The answer will have major implications for US and global markets.

- CBR - Public Policy

Some Fathers Are Less Willing to Spend on Daughters than on Sons

Findings from a series of surveys suggest that simple gender preference may be the explanation.

Related Topics

- CBR - Fall 2021

- CBR - Remote Work

- Coronavirus

- CBR - Coronavirus

More from Chicago Booth

Your Privacy We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice , which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.

Golf, rent, and commutes: 7 impacts of working from home

The pandemic sharply accelerated trends of people working from home, leaving lasting impacts on how we work going forward. Stanford scholar Nicholas Bloom details how working from home is affecting the office, our homes, and more.

The massive surge in the number of people working from home may be the largest change to the U.S. economy since World War II, says Stanford scholar Nicholas Bloom .

And the shift to working from home, catalyzed by the pandemic, is here to stay, with further growth expected in the long run through improvements in technology.

Looking at data going back to 1965, when less than 1% of people worked from home, the number of people working from home had been rising continuously up to the pandemic, doubling roughly every 15 years, said Bloom, the William D. Eberle Professor in Economics in the School of Humanities and Sciences and professor, by courtesy, at Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Before the pandemic, only around 5% of the typical U.S. workforce worked from home; at the pandemic’s onset, it skyrocketed to 61.5%. Currently, about 30% of employees work from home.

“In some ways, one of the biggest lasting legacies of the pandemic will be the shift to work from home,” said Bloom.

Bloom shared his research on working from home at the Stanford Distinguished Careers Institute ’s “The Future of Work” Winter 2023 Colloquium, which focused on how the ways we work are changing.

DCI Director Richard Saller moderated the event , which featured scholars from Stanford and beyond discussing working arrangements and attitudes, challenges to office real estate, learned lessons about the power of proximity, and more.

Below are seven takeaways from Bloom’s discussion:

- The employees. About 58% of people in the U.S. can’t work from home at all, and they are typically frontline workers with lower pay. Those who work entirely from home are primarily professionals, managers, and in higher-paying fields such as IT support, payroll, and call centers. The highest paid group includes the 30% of people working from home in a hybrid capacity, and these include professionals and managers.

- The move. Almost 1 million people left city centers like New York and San Francisco during the pandemic. Those who used to go to the office five days a week are now willing to commute farther because they are only in the office a couple days a week, and they want larger homes to accommodate needs such as a home office. This has changed property markets substantially with rents and home values in the suburbs surging, Bloom said. Home values in city centers have risen but not by much.

- The commute. Public transit journeys have plummeted and are currently down by a third compared to pre-pandemic levels. This sharp reduction is threatening the survival of mass transit, Bloom said. These are systems that have relatively fixed costs because the hardware and labor, which is largely unionized, are relatively hard to adjust. A lot of the revenues come from ticket sales, and these agencies are losing a lot of money.

- The office. Offices are changing, with cubicles becoming less popular and meeting rooms more desirable. As some companies incorporate an organized hybrid schedule in which everyone comes in on certain days, they are redesigning spaces to support more meetings, presentations, trainings, lunches, and social time.

- The startups. Startup rates are surging, up by 20% from pre-pandemic numbers. The reasons: working from home provides a cheaper way to start a new company by saving a lot on initial capital and rent. Also, people can more easily work on a startup on the side when their regular job offers the option to work from home.

- The downtime. The number of people playing golf mid-week has more than doubled since 2019. People used to go before or after work, or on the weekends, but now the mid-day, mid-week golf game is becoming more common. The same is probably true for things like gyms, tennis courts, retail hairdressers, ski resorts, and anything else that consumers used to pack into the weekends.

- The organization. More and more, firms are outsourcing or offshoring their information technology, human resources, and finance to access talent, save costs, and free up space. There has been a big increase in part-time employees, independent contractors, and outsourcing. “After seeing how well it worked with remote work at the beginning of the pandemic, companies may not see a need to have employees in the country,” Bloom said.

Interested in hearing more about the future of work? Stanford Continuing Studies will feature Bloom as he discusses “The Future of and Impact of Working from Home” on May 1 as part of the Stanford Monday University web seminar series .

Bloom is also co-director of the Productivity, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship program at the National Bureau of Economic Research, a fellow at the Centre for Economic Performance, and a senior fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research .

Does Working from Home Boost Productivity Growth?

Ethan Goode

Brigid Meisenbacher

Download PDF (255 KB)

FRBSF Economic Letter 2024-02 | January 16, 2024

An enduring consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic is a notable shift toward remote and hybrid work. This has raised questions regarding whether the shift had a significant effect on the growth rate of U.S. productivity. Analyzing the relationship between GDP per hour growth and the ability to telework across industries shows that industries that are more adaptable to remote work did not experience a bigger decline or boost in productivity growth since 2020 than less adaptable industries. Thus, teleworking most likely has neither substantially held back nor boosted productivity growth.

The U.S. labor market experienced a massive increase in remote and hybrid work during the COVID-19 pandemic. At its peak, more than 60% of paid workdays were done remotely—compared with only 5% before the pandemic. As of December 2023, about 30% of paid workdays are still done remotely (Barrero, Bloom, and Davis 2021).

Some reports have suggested that teleworking might either boost or harm overall productivity in the economy. And certainly, overall productivity statistics have been volatile. In 2020, U.S. productivity growth surged. This led to optimistic views in the media about the gains from forced digital innovation and the productivity benefits of remote work. However, the surge ended, and productivity growth has retreated to roughly its pre-pandemic trend. Fernald and Li (2022) find from aggregate data that this pattern was largely explained by a predictable cyclical effect from the economy’s downturn and recovery.

In aggregate data, it thus appears difficult to see a large cumulative effect—either positive or negative—from the pandemic so far. But it is possible that aggregate data obscure the effects of teleworking. For example, factors beyond telework could have affected the overall pace of productivity growth. Surveys of businesses have found mixed effects from the pandemic, with many businesses reporting substantial productivity disruptions.

In this Economic Letter , we ask whether we can detect the effects of remote work in the productivity performance of different industries. There are large differences across sectors in how easy it is to work off-site. Thus, if remote work boosts productivity in a substantial way, then it should improve productivity performance, especially in those industries where teleworking is easy to arrange and widely adopted, such as professional services, compared with those where tasks need to be performed in person, such as restaurants.

After controlling for pre-pandemic trends in industry productivity growth rates, we find little statistical relationship between telework and pandemic productivity performance. We conclude that the shift to remote work, on its own, is unlikely to be a major factor explaining differences across sectors in productivity performance. By extension, despite the important social and cultural effects of increased telework, the shift is unlikely to be a major factor explaining changes in aggregate productivity.

Possible productivity effects of telework

Teleworking might affect output per hour in different ways. For example, in surveys, many workers claim to be more productive remotely (Barrero et al 2021). That said, some workers might face more disruptions, such as childcare demands or inferior equipment. In addition, idea sharing may be more difficult online, and workers may need to devote time to learning new skills. Alternatively, any association between the ability to telework and productivity performance could reflect other factors. For example, industries where the majority of work needs to be done in person could have faced more disruptions from social-distancing requirements or supply chain bottlenecks.

Thus, in theory the relationship between telework and productivity balances both positive and negative effects. The net effect may also change over time as businesses and workers adjust to new modes of working.

Empirical evidence tends to involve relatively narrow sets of tasks, such as call centers, where output can be easily measured. For example, Bloom et al. (2015) find that workers in a call center in China who were randomly assigned to remote work were more productive than in-person workers. In contrast, Emanuel and Harrington (2023) find that call-center workers at a Fortune 500 company were slightly less productive after they were forced to work remotely at the onset of the pandemic. Emanuel and Harrington (2023) discuss other literature that finds a mix of productivity gains and costs. Because of the narrow scope of the empirical evidence, we turn to industry data to provide more insight.

Measuring productivity growth by industry

In this Letter , we measure industry productivity by output, using value added, per hour. We focus on 43 industries that span the private economy, including, for example, chemical manufacturing, retail trade, and accommodation and food services. We exclude the real estate, rental, and leasing industry because a large fraction of output in this industry is imputed rather than directly measured.

We construct industry-level productivity by combining national accounts measures of output by industry from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) and all-employee aggregate weekly hours from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Our industry-level productivity data set is available quarterly starting in the second quarter of 2006 and ending in the first quarter of 2023. For each industry, we calculate the average annualized growth in quarterly productivity to measure changes in industry productivity over the pandemic.

We measure teleworkability by industry using the occupational mix of different industries and the teleworkability of different occupations. For the latter, we rely on occupational teleworkability scores from Dingel and Neiman (2020), which assigns 462 occupations a score between zero and one based on the job characteristics reported in the O*NET survey. Occupations that cannot be done remotely, such as custodial workers and waiters, were given a score of zero, while entirely teleworkable jobs, such as mathematicians and research scientists, received scores of one. Occupations that fall between the poles include counselors and medical records technicians, which receive scores of 0.5. Bick, Blandin, and Mertens (2020) report that actual teleworking shares are highly related to the Dingel and Neiman measures.

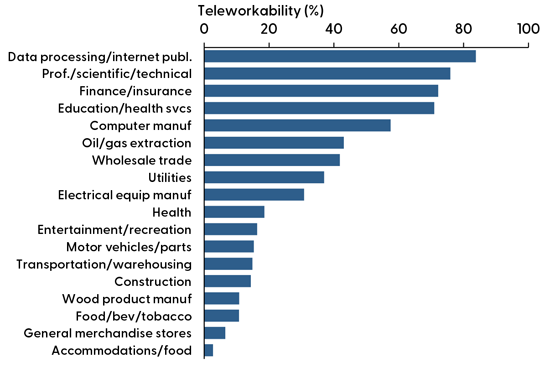

We aggregate these occupation-level scores to an industry-level average by weighing the teleworkability score for each occupation by the 2018 share of industry employment from the BLS Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics. For example, we assign the data processing industry a score of 0.88 because most of the workers in this industry are in highly teleworkable occupations, such as software developers and programmers.

Figure 1 displays scores for a subset of industries ordered from the most teleworkable on the top to the least teleworkable on the bottom. The most teleworkable industries are data processing and professional services. The least teleworkable industries are accommodation and food services and some retailers. The figure demonstrates that teleworkability varies widely across industries, ranging from less than 10% to close to 90% of an industry’s workers.

Figure 1 Teleworkability by industry

Industry productivity and teleworkability

Since industries differ considerably in their adaptability to remote work, one would imagine that the shift to telework during the pandemic would affect industries differently. For example, if teleworking offered an important way to circumvent production disruptions brought on by the pandemic, teleworkable industries would have performed better because they faced lower costs to adopting teleworking.

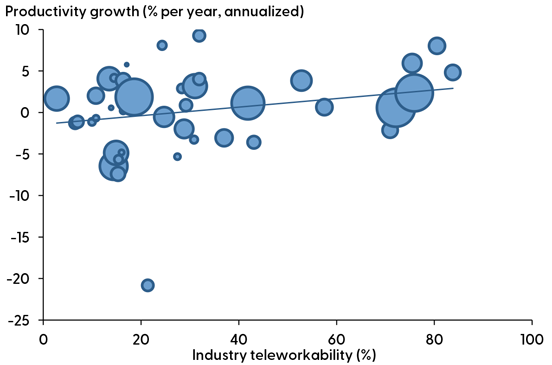

We next examine this relationship between teleworkability and industry productivity growth during and following the pandemic, shown in Figure 2. The horizontal axis measures teleworkability by industry, constructed from the Dingel and Neiman measures in Figure 1. The vertical axis is annualized quarterly productivity growth from the fourth quarter of 2019 to the first quarter of 2023, measured in percentage points. The size of the bubbles conveys the pre-pandemic share of an industry’s contribution to total output, measured as industry value-added, as of the fourth quarter of 2019.

Figure 2 Industry productivity growth versus teleworkability

The blue fitted line reflects the average relationship between the two variables. The figure shows that more-teleworkable industries grew somewhat faster during the pandemic than less-teleworkable industries. A 1 percentage point increase in teleworkability is associated with a 0.05 percentage point increase in an industry’s predicted pandemic productivity growth rate. The relationship is statistically significant.

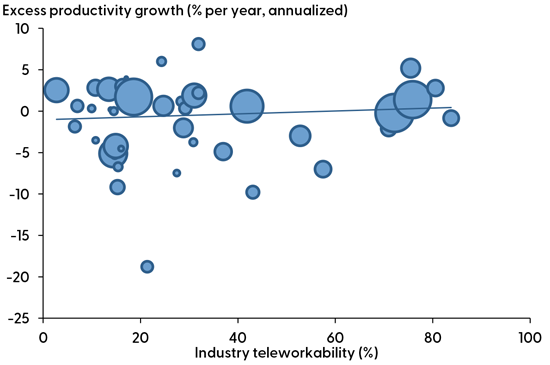

However, it turns out that more-teleworkable industries also grew faster before the pandemic. To better isolate the association with the shift to remote work during the pandemic, Figure 3 controls for pre-pandemic trends by removing each industry’s average annualized productivity growth for 2006–2019 from its pandemic average. Hence, the vertical axis now captures the amount by which an industry’s pandemic productivity growth exceeded or fell short of its pre-pandemic pace.

In Figure 3, the nearly flat blue line reflects that there is essentially no relationship between teleworkability and excess pandemic productivity growth. Although the association is still slightly positive, the relationship is much weaker than in Figure 2 and is not statistically significant.

Figure 3 Productivity growth, accounting for pre-pandemic trends

Both Figures 2 and 3, show that productivity growth varied significantly across industries. But based on Figure 3, it appears unlikely that the differences in performance during the pandemic across industries have much to do with differences in teleworking. Fernald and Li (2022) take the analysis one step further by considering that growth in work hours might be mismeasured to the extent that people are working more “off the clock” (Barrero et al. 2021). That analysis reinforces the conclusion from Figure 3, that there is essentially no relationship between teleworkability and pandemic productivity growth. We found similar results using only data during 2020 when firms were first adjusting to new work arrangements. The results are also similar for 2021-23, when firms had more experience with remote work and were also shifting to reopening office workspaces and, increasingly, to hybrid work.

The shift to remote and hybrid work has reshaped society in important ways, and these effects are likely to continue to evolve. For example, with less time spent commuting, some people have moved out of cities, and the lines between work and home life have blurred. Despite these noteworthy effects, in this Letter we find little evidence in industry data that the shift to remote and hybrid work has either substantially held back or boosted the rate of productivity growth.

Our findings do not rule out possible future changes in productivity growth from the spread of remote work. The economic environment has changed in many ways during and since the pandemic, which could have masked the longer-run effects of teleworking. Continuous innovation is the key to sustained productivity growth. Working remotely could foster innovation through a reduction in communication costs and improved talent allocation across geographic areas. However, working off-site could also hamper innovation by reducing in-person office interactions that foster idea generation and diffusion. The future of work is likely to be a hybrid format that balances the benefits and limitations of remote work.

Barrero, Jose Maria, Nicolas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis. 2021. “Why Working from Home Will Stick.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 28731. Updated survey results available from https://wfhresearch.com/ .

Bick, Alexander, Adam Blandin, and Karel Mertens. 2020. “ Work from Home before and after the COVID-19 Outbreak .” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 15(4), pp. 1-39.

Bloom, Nicholas, James Liang, John Roberts, and Zhichun Jenny Ying. 2015. “Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 130(1), pp. 165¬-218.

Dingel, Jonathan I., and Brent Neiman. 2020. “How Many Jobs Can Be Done at Home?” Journal of Public Economics 189(104235).

Emanuel, Natalia, and Emma Harrington. 2023. “ Working Remotely? Selection, Treatment, and the Market for Remote Work .” FRB New York Staff Report 1061 (May).

Fernald, John, and Huiyu Li. 2022. “ The Impact of COVID on Productivity and Potential Output .” Paper presented at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s Economic Policy Symposium, Jackson Hole, WY, August 25.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to [email protected]

The Truth About Work-From-Home Productivity

Hybrid and fully remote teams can be far more productive than in-person teams..

Posted October 3, 2022 | Reviewed by Davia Sills

- What Is a Career

- Find a career counselor near me

- Most employees prefer hybrid or remote work, but companies are wary of the cost to effectiveness.

- Work-from-home productivity is generally higher than in the office, research shows, especially on individual tasks.

- A policy of flexibility helps companies maximize both retention and productivity of employees.

Is work-from-home productivity higher or lower than in the office? Research shows that hybrid and even fully remote teams can gain a substantial productivity advantage if their leaders stop relying on traditional office-based culture and methods of collaboration . Instead, by adopting best practices for hybrid and remote work, forward-thinking leaders can drastically outcompete in-person teams in productivity.

Work-From-Home Productivity

Alex, the Chief Executive Officer of a 900-employee SaaS (Software as a Service) company, wanted to figure out his future work arrangements. His default plan was an office-centric environment. He feared that if his team didn’t return to the office full time, he would lose out to rivals who could do so and gain productivity benefits by working from the office.

This is not an unusual situation. Indeed, numerous companies are concerned about workplace productivity in remote work. The belief underlying this thought process is that people can’t be truly productive outside of the office: Elon Musk claimed those working remotely are only “pretending to work.”

Alex hired a consultant with expertise in hybrid and remote work, who told the CEO that many employees might leave if forced to come back to the office full time because the large majority of employees prefer fully remote or at least hybrid work arrangements. In fact, data clearly show that workers—especially tech workers like at his company—are more productive working remotely.

External Research on Work-From-Home Productivity

A two-year study published in February 2021 of 3 million employees at 715 U.S. companies, including many from the Fortune 500 list, showed that working from home improved employee productivity by an average of 6 percent.

Another survey of 800 employers found that 94 percent of employers said their employees were just as productive or even more productive while working remotely. And 83 percent of workers said they were happy with remote work arrangements, while only 7 percent wanted to return to an office immediately. Most workers said they wanted a hybrid setup when they do eventually return to their workplaces, splitting their time between home and the office.

Such remote work productivity gains aren’t surprising. Pre-COVID research showed that telework boosted productivity; after all, remote work removes many hassles taking up time for in-office work, such as lengthy daily commutes. Moreover, working from home allows employees much more flexibility to do work tasks at times that work best for their work-life balance, rather than the traditional 9-to-5 schedule. Such flexibility matches research showing we all have different times of day when we are best suited for certain tasks, enabling us to be more productive when we have more flexible schedules.

Some might feel worried that these productivity gains are limited to the context of the pandemic. Fortunately, research shows that after a forced period of work from home, if workers are given the option to keep working from home, those who choose to do so experience even greater productivity gains than in the initial forced period.

An important academic paper from the University of Chicago provides further evidence of why working at home will stick. First, the researchers found that working at home proved a much more positive experience for employers and employees alike than either had anticipated. That led employers to report a willingness to continue work-from-home after the pandemic.

Second, an average worker spent over 14 hours and $600 to support their work-from-home. In turn, companies made large-scale investments in back-end IT facilitating remote work. Some paid for home office equipment for employees. Furthermore, remote work technology improved over this time. Therefore, both workers and companies will be more invested in telework after the pandemic.

Apart from that, non-survey research similarly shows significant productivity gains for remote workers during the pandemic. Moreover, governments plan to invest in improving teleworking infrastructure, making higher productivity gains even more likely.

Academics demonstrated a further increase in productivity in remote work throughout the pandemic. A study from Stanford showed that efficiency for remote work increased from 5 percent greater than in the office in the summer of 2020 to 9 percent greater in May 2022, as companies and employees alike grew more comfortable with work-from-home arrangements.

A Hybrid-First Model of Work-From-Home Productivity

The next step involved figuring out how to improve worker productivity further for the SaaS company. To better understand what staff needed, the consultant helped the company conduct an internal survey to ascertain work preferences and productivity.

Upon gathering data on the preferred working styles of employees, the consultant discovered that employees expressed a strong desire to work from home. Around 59 percent of employees indicated a preference for hybrid work environments (one to two days per week in the office) and no full-time in-office work, while 32 percent indicated a strong willingness to work at home full-time, and only 19 percent wanted three or more days of in-office work.

After analyzing the results of the internal as well as external data, the consultant advised Alex to implement a hybrid-first approach with one day in the office for most staff and fully-remote options for those who wanted them. A hybrid-first approach proved most compatible with the desires of the vast majority of employees, allowing them to remain productive while retaining them effectively. The consultant concluded that the company should transition to a hybrid-first model in which some work is done from home and some from the office.

Hybrid-first models work even better when leaders adopt best practices for hybrid work. These involve addressing proximity bias , maximizing social capital, and facilitating remote innovation .

Alex and the rest of the management team were initially skeptical of the proposed hybrid-first approach, but after trying it out and seeing months of high employee productivity and retention, they are now believers. Those employees permitted to remain fully remote proved willing to go above and beyond to get the job done. They also swiftly adapted to changes required for their company’s success by working flexible hours to accommodate the shift of most employees to working occasionally in the office. As a result, the hybrid-first work strategy established an environment where employees could effectively manage their tasks while maintaining a good work-life balance.

To best maximize the productivity of their employees, companies must understand where they are most productive. And if they wish to retain them, employers need to appreciate and meet the preferences of their employees. Fortunately, hybrid and fully-remote work options allow the best of both worlds. A hybrid-first model is the best practice for hybrid and remote work, enabling leaders willing to let go of their intuitions and rely on evidence from both academic research, internal and external surveys, and case studies from progressive companies to seize a competitive advantage in the future of work.

Tsipursky, G. (2021). Leading Hybrid and Remote Teams: A Manual on Benchmarking to Best Practices for Competitive Advantage. Columbus, OH: Intentional Insights Press.

Alexander, A., De Smet, A., Langstaff, M., & Ravid, D. (2021). What employees are saying about the future of remote work. McKinsey & Company.

Bloom, Nicholas, et al. "Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 130.1 (2015): 165-218.

Chatterjee, S., Chaudhuri, R., & Vrontis, D. (2022). Does remote work flexibility enhance organization performance? Moderating role of organization policy and top management support. Journal of Business Research, 139, 1501-1512.

Donati, S., Viola, G., Toscano, F., & Zappalà, S. (2021). Not all remote workers are similar: technology acceptance, remote work beliefs, and wellbeing of remote workers during the second wave of the covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 12095.

Ferreira, Rafael, et al. "Decision factors for remote work adoption: advantages, disadvantages, driving forces and challenges." Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 7.1 (2021): 70.

Galanti, T., Guidetti, G., Mazzei, E., Zappalà, S., & Toscano, F. (2021). Work from home during the COVID-19 outbreak: The impact on employees’ remote work productivity, engagement, and stress. Journal of occupational and environmental medicine, 63(7), e426.

Yang, L., Holtz, D., Jaffe, S., Suri, S., Sinha, S., Weston, J., ... & Teevan, J. (2022). The effects of remote work on collaboration among information workers. Nature human behaviour, 6(1), 43-54.

Gleb Tsipursky, Ph.D. , is on the editorial board of the journal Behavior and Social Issues. He is in private practice.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Are you more productive working from home? This study looks for answers

Studies in Japan suggest home workers' productivity has increased during the pandemic. Image: Unsplash/Avel Chuklanov

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Masayuki Morikawa

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Future of Work is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, future of work.

- The pandemic helped lead a huge rise in remote working, but there is still relatively little data about the practice and and its impact.

- Researchers compare two recent studies conducted with home workers in Japan during the pandemic.

- Their findings suggest the average productivity of home workers has increased but is still lower than that of the usual workplace.

- They warn that while WFH could become a preferred way of working for employees in the future, a recent survey of Japanese employers found many plan to discontinue the practice.

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of workers working from home (WFH) has been increasing rapidly. There has also been a rapid, parallel increase in research on WFH. We now know what workers need to be able to WFH as well as what type of workers are actually WFH. Findings generally show that highly skilled, high-wage, white-collar employees in large firms tend to WFH, meaning that the expansion of WFH has tended to increase inequality in the labour market. However, productivity of WFH has not yet been well understood.

Studies on WFH productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic

Currently, business managers and policy practitioners are interested in whether WFH will continue as a new workstyle after the COVID-19 pandemic ends. Productivity of WFH is a key determinant of whether WFH will persist or not, but quantitative evidence on WFH productivity is still limited. Studies based on surveys of workers include Etheridge et al. (2020), Barrero et al. (2021), and my work (Morikawa 2020). 1 Since it is extremely challenging to measure the productivity of white-collar workers, who perform a large variety of tasks, all of these studies depend on the workers’ self-assessment of WFH productivity.

Etheridge et al. (2020) show that, on average, workers in the UK adopting WFH report little difference in productivity relative to productivity before the pandemic. In the US, Barrero et al. (2021) indicate that most respondents who adopted WFH report equal to or higher WFH productivity than productivity on business premises. My study (Morikawa 2020) was based on a 2020 survey of workers in Japan and documents that the mean WFH productivity was approximately 60% to 70% relative to working at the usual workplace and that it was lower for employees who were forced to start WFH only after the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. To summarise, studies on the productivity of WFH under the COVID-19 pandemic are still limited, and the results are far from conclusive.

To explore the productivity dynamics of WFH during the COVID-19 pandemic, I extend the analysis of my 2020 study. I conducted a follow-up survey in 2021 to explore the changes in prevalence, frequency, and productivity of WFH during a year of the pandemic and discuss the future of WFH after the COVID-19 pandemic (Morikawa 2021).

Keeping workers well. It is the united aim of a global community influencing how companies will keep employees safe. What is the role of COVID-19 testing? What is the value of contact tracing? How do organizations ensure health at work for all employees?

Members from a diverse range of industries – from healthcare to food, utilities, software and more – and from over 25 countries and 250 companies representing more than 1 million employees are involved in the COVID-19 Workplace Commons: Keeping Workers Well initiative. Launched in July 2020, the project is a partnership between the World Economic Forum and Arizona State University with support from The Rockefeller Foundation.

The COVID-19 Workplace Commons: Keeping Workers Well initiative leverages the Forum’s platforms, networks and global convening ability to collect, refine and share strategies and approaches for returning to the workplace safely as part of broader COVID-19 recovery strategies.

Companies can apply to share their learnings and participate in the initiative as a partner, by joining the Forum’s Platform for Shaping the Future of Health and Healthcare.

Learn more about the impact .

Prevalence and frequency of WFH

Our 2021 survey asked workers in Japan about the adoption and frequency of WFH. The responses show that 21.5% of workers were practising WFH, which is a decrease from 32.2% a year prior. Among only continuing (panel) respondents, the extent of the decline was larger: it decreased from 37.1% to 21.1%. Of the employees who responded to both 2020 and 2021 surveys, 41.7% stopped practising WFH, indicating that a non-negligible number of workers reverted to working at their usual workplace. In particular, individuals with lower WFH productivity had a higher probability of exiting from WFH.

In contrast, the mean share of WFH days (WFH days divided by weekly working days) is almost unchanged during the past year: 55.7% in the 2020 survey and 56.6% in the 2021 survey. Even for the subsample of those who responded to both surveys and who continued to implement WFH, the mean frequencies of WFH are almost unchanged (55.9% in 2020 and 54.3% in 2021). While the change in the extensive margin (adoption) is relatively large, the change in the intensive margin (frequency) is negligible.

Productivity dynamics of WFH

The surveys asked the subjects to self-assess WFH productivity relative to one’s productivity at the usual workplace (= 100). The distributions of WFH productivity in 2020 and 2021 are in Figure 1. The figure shows that (1) the overall distribution has shifted slightly right, and (2) the lower end of the distribution has shrunk substantially. The mean WFH productivity has improved from 61 in 2020 to 78 in 2021 (where productivity at the usual workplace = 100). The subsample of panel employees shows a similar pattern: the mean productivity has improved from 61 to 77.

Figure 1 Change in WFH productivity distribution

The WFH productivity of those who continuously engaged in WFH improved from 70 in 2020 to 78 in 2021. The 8-point increase in WFH productivity comes from, for example, learning effects and investment in WFH infrastructure at home. The mean WFH productivity in the 2020 survey of those who exit from WFH was 49, far lower than that of WFH continuers (70). This selection mechanism contributes to a 9-point improvement in mean WFH productivity. In short, (1) a ‘selection effect’ arising from the exit of low-WFH-productivity employees from WFH practice, and (2) the improvement in WFH productivity through a ‘learning effect’ contributed almost equally to the improved mean WFH productivity.

WFH after the COVID-19 pandemic

Both the 2020 and 2021 surveys asked the telecommuters about their intention to continue WFH after the pandemic. The percentage of WFH workers who answered they would like to practice WFH at the same frequency as they currently do even when the COVID-19 pandemic subsides increased substantially from 38.1% in the 2020 survey to 62.6% in the 2021 survey (Figure 2). Even for the subsample of WFH continuers, the percentage has increased from 56.2% to 68.2%.

Figure 2 WFH after the COVID-19 pandemic

We posit that the possible reasons behind this change are (1) the improvement in WFH productivity, and (2) the increasing recognition of the amenity value of WFH. Since there was a strong positive correlation between the intention in 2020 to continue frequent WFH and the actual implementation of WFH in 2021, the result suggests that WFH may become a preferred work style even after the pandemic subsides. As described before, the productivity of WFH is, on average, still lower than that of the usual workplace, meaning that WFH has a high amenity value for teleworkers.

Have you read?

Working from home here’s why you should start your day with a ‘virtual commute’, covid-19: most american workers want to keep working from home, how does working from home impact productivity.

However, according to a survey of Japanese firms conducted in late 2021, the majority of firms are planning to discontinue the WFH practice and revert to the conventional workstyle after the end of COVID-19 (Morikawa 2022b). These contrasting results indicate that there is a large gap between firms’ interests and the preferences of WFH workers. From the viewpoints of the productivity-wage parity and the compensating wage differential, it is possible that WFH workers’ relative wages will be reduced. However, since it is difficult to accurately capture the productivity of individual workers who perform WFH, there is a potential that conflict between workers and management over WFH will arise after the pandemic.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Future of Work .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Green job vacancies are on the rise – but workers with green skills are in short supply

Andrea Willige

February 29, 2024

Digital Cooperation Organization - Deemah Al Yahya

Why clear job descriptions matter for gender equality

Kara Baskin

February 22, 2024

Improve staff well-being and your workplace will run better, says this CEO

Explainer: What is a recession?

Stephen Hall and Rebecca Geldard

February 19, 2024

Is your organization ignoring workplace bullying? Here's why it matters

Jason Walker and Deborah Circo

February 12, 2024

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Research: Knowledge Workers Are More Productive from Home

- Julian Birkinshaw,

- Jordan Cohen,

- Pawel Stach

More people are focusing on work they find worthwhile.

Researchers studied knowledge workers in 2013 and again during the 2020 pandemic lockdown and found significant changes in how they are working. They learned that lockdown helps people focus on the tasks that really matter. They spent 12% less time drawn into large meetings and 9% more time interacting with customers and external partners. Lockdown also helped people take responsibility for our own schedules. They did 50% more activities through personal choice and half as many because someone else asked them to. Finally, during lockdown, people viewed their work as more worthwhile. The number of tasks rated as tiresome dropped from 27% to 12%, and the number we could readily offload to others dropped from 41% to 27%.

In these difficult times, we’ve made a number of our coronavirus articles free for all readers. To get all of HBR’s content delivered to your inbox, sign up for the Daily Alert newsletter.

For many years, we have sought to understand and measure the productivity of knowledge workers, whose inputs and outputs can’t be tracked in the same way as a builder, shelf-stacker, or call center worker. Knowledge workers apply subjective judgment to tasks, they decide what to do when, and they can withhold effort (by not fully engaging their brain) often without anyone noticing. This make attempts to improve their productivity very difficult.

- Julian Birkinshaw is a professor at London Business School. He is the coauthor of Fast/Forward: Make Your Company Fit for the Future .

- Jordan Cohen is the Chief People Officer at Lumanity and a regular contributor to HBR.

- Pawel Stach is a researcher at London Business School.

Partner Center

To sign up for monthly results updates please click here.

Download our time series data on the extent of working from home., new working from home around the globe: 2023 report , by cevat aksoy, jose maria barrero,, nicholas bloom, steven j. davis, mathias dolls, and pablo zarate, coverage : the economist “the fight over working from home goes global”, download summary data.

Research papers

Read our detailed research output and find historical results updates in our Research and Policy page.

Latest Results Summary

Read the latest monthly results summary based on our US SWAA data.

U.S. Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes

Download the latest data from the Survey of Workplace Arrangements & Attitudes (SWAA).

Global Survey of Working Arrangements

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Researchers working from home: Benefits and challenges

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Institute of Psychology, ELTE Eotvos Lorand University, Budapest, Hungary

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Institute of Psychology, ELTE Eotvos Lorand University, Budapest, Hungary, Doctoral School of Psychology, ELTE Eotvos Lorand University, Budapest, Hungary

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Sociology, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

- Balazs Aczel,

- Marton Kovacs,

- Tanja van der Lippe,

- Barnabas Szaszi

- Published: March 25, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249127

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

The flexibility allowed by the mobilization of technology disintegrated the traditional work-life boundary for most professionals. Whether working from home is the key or impediment to academics’ efficiency and work-life balance became a daunting question for both scientists and their employers. The recent pandemic brought into focus the merits and challenges of working from home on a level of personal experience. Using a convenient sampling, we surveyed 704 academics while working from home and found that the pandemic lockdown decreased the work efficiency for almost half of the researchers but around a quarter of them were more efficient during this time compared to the time before. Based on the gathered personal experience, 70% of the researchers think that in the future they would be similarly or more efficient than before if they could spend more of their work-time at home. They indicated that in the office they are better at sharing thoughts with colleagues, keeping in touch with their team, and collecting data, whereas at home they are better at working on their manuscript, reading the literature, and analyzing their data. Taking well-being also into account, 66% of them would find it ideal to work more from home in the future than they did before the lockdown. These results draw attention to how working from home is becoming a major element of researchers’ life and that we have to learn more about its influencer factors and coping tactics in order to optimize its arrangements.

Citation: Aczel B, Kovacs M, van der Lippe T, Szaszi B (2021) Researchers working from home: Benefits and challenges. PLoS ONE 16(3): e0249127. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249127

Editor: Johnson Chun-Sing Cheung, The University of Hong Kong, HONG KONG

Received: September 24, 2020; Accepted: March 11, 2021; Published: March 25, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Aczel et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All research materials, the collected raw and processed anonymous data, just as well the code for data management and statistical analyses are publicly shared on the OSF page of the project: OSF: https://osf.io/v97fy/ .

Funding: TVL's contribution is part of the research program Sustainable Cooperation – Roadmaps to Resilient Societies (SCOOP). She is grateful to the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) and the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (OCW) for their support in the context of its 2017 Gravitation Program (grant number 024.003.025).

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction