Famous Philosophers

Biography, Facts and Works

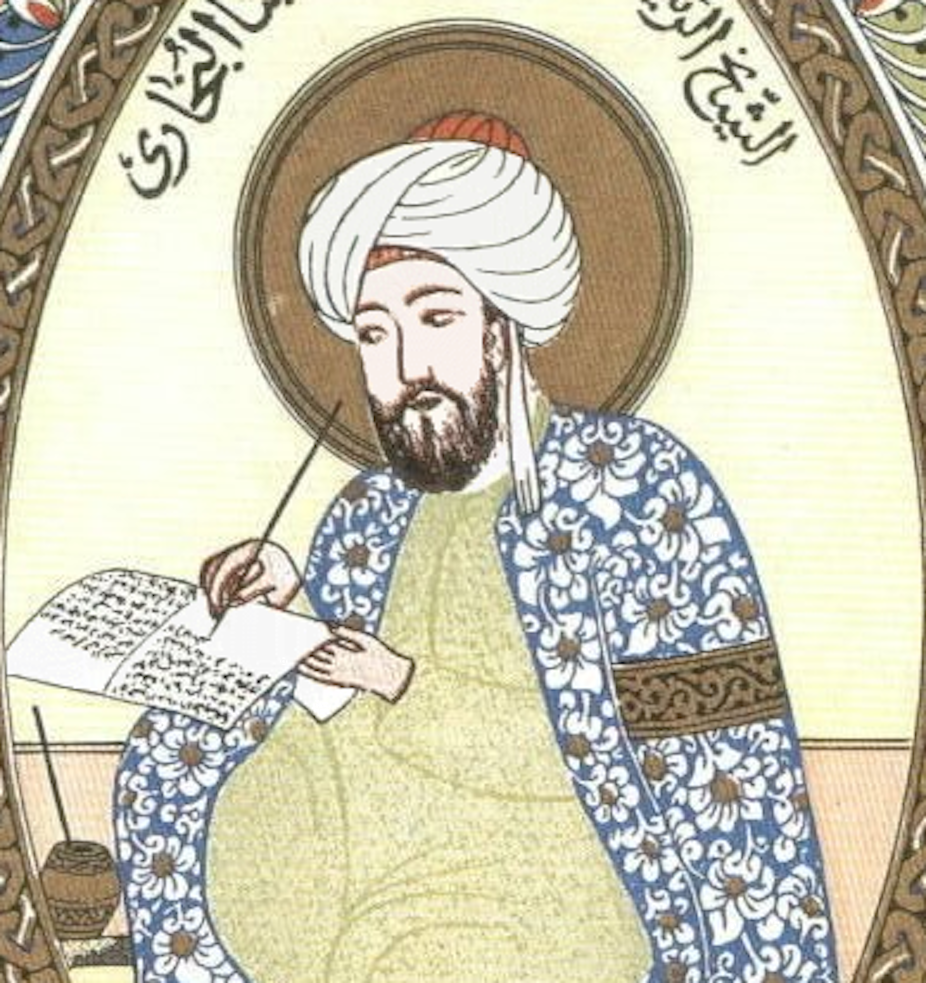

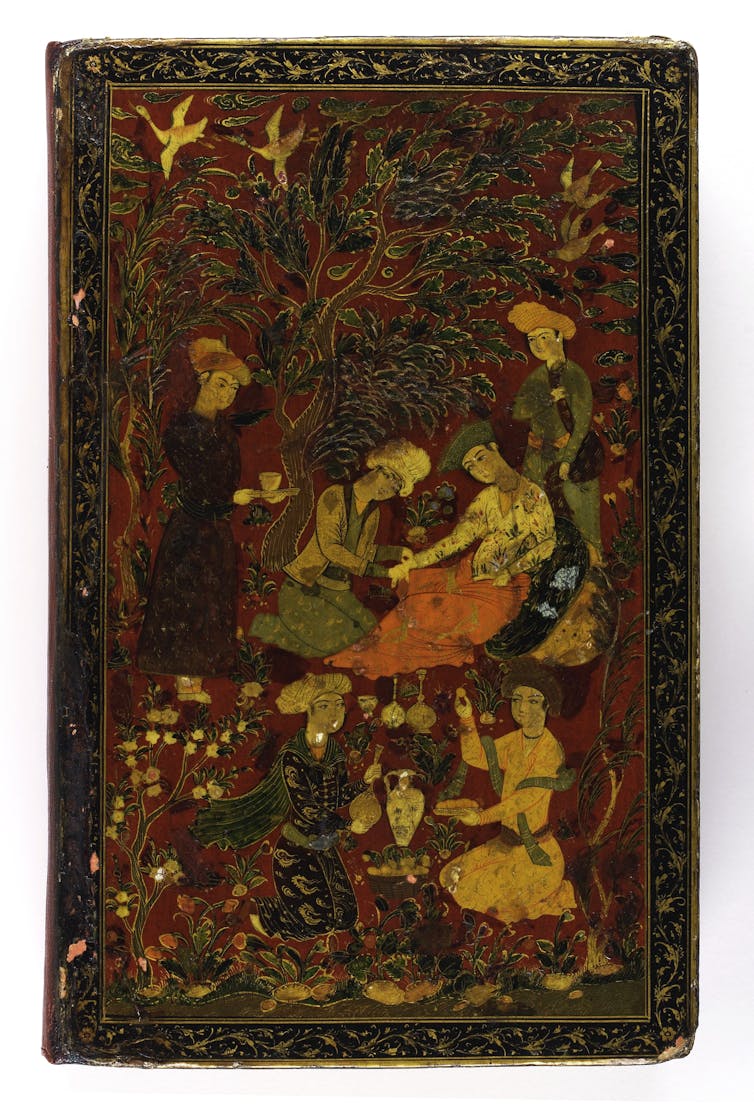

Ibn Sina, also known by his Latinized name in Europe as Avicenna, was a Persian philosopher and polymath, born in 980 CE. Regarded as one of the most influential thinkers and writers of the Islamic Golden Age, Ibn Sina wrote extensively on philosophy of ethics and metaphysics, medicine, astronomy, alchemy, geology psychology and Islamic theology. He was also a logician, mathematician and a poet.

Born in Afshana, Bukhara in Central Asia, his work on medicine, specifically the Canon, or the Qanun fil Tibb , was taught in schools in the Islamic world and in Europe alike till the early modern era. His treatise on philosophy, the Cure, or al Shifa , was greatly influential on European scholastics, such as Thomas Aquinas .

Chiefly being a metaphysical philosopher, Ibn e Sina attempted at presenting a comprehensive system linking human existence and experiences with its contingency, while staying in harmony with the Islamic exigency. Thus, he is considered as the first significant Muslim philosopher of all times. He based his theories on God as the chief Existence, and this forms the foundations of his ideas on soul, human rationale and the cosmos. He also attempted at a philosophical interpretation of religion and religious beliefs.

For Ibn Sina, gaining education was of foremost importance. Grasping the logic and the comprehensible is the first step towards determining the fate of one’s soul, thereby deciding human actions. For Ibn Sina, people can be categorized on the basis of their ability to grasp the intelligible. The highest category comprises of the prophets, who have pure rational souls and have knowledge of all things intelligible. The lowest is the person with an impure soul, who lacks the capability of developing an argument. People can elevate their position in the categories by having a rational approach, balanced temperament and by purifying their soul.

In the field of metaphysics, Ibn Sina differentiates between what exists and its essence. Essence is what comprises the nature of things, and should be recognized as something separate from the physical and mental realization of things. This difference applies to all things except God, said Ibn Sina. For him, God is the basic cause and so it is both the essence and the existence. He further argued that soul is ethereal and intangible; it cannot be destroyed. Is it the soul which compels a person to choose between good and evil in this world, and is a source of reward or punishment in the hereafter.

Being a devout Muslim himself, Ibn Sina applied rational philosophy at interpreting divine text and Islamic theology. His ultimate aim was to prove God’s presence and existence and the world is His creation through scientific reason and logic. His teachings and views on theology were part of the core curriculum of various schools across the Islamic world well into the nineteenth century. Ibn Sina also penned down a significant number of short treatise on Islamic theology and the prophets, whom he termed as ‘inspired philosophers’. He also linked rational philosophy with interpretation of Quran, the holy book of muslims.

Ibn e Sina passed away in June 1037, in the Hamadan area of Iran. Out of his 450 various publications and treatises, almost 240 of them have survived, majority of which belongs to philosophy and medicine.

Buy books by Ibn Sina

- John Searle

- John Stuart Mill

- Jonathan Edwards

- Judith Butler

- Julia Kristeva

- Jürgen Habermas

- Karl Jaspers

- Lucien Goldmann

- Ludwig Wittgenstein

- Marcus Aurelius

- Mario Bunge

- Martha Nussbaum

- Martin Buber

- Martin Heidegger

- Mary Wollstonecraft

- Max Scheler

- Max Stirner

- Meister Eckhart

- Michel Foucault

- Miguel De Unamuno

- Niccolò Machiavelli

- Nick Bostrom

- Noam Chomsky

- Peter Singer

- René Descartes

- Robert Nozick

- Roland Barthes

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Rudolf Steiner

- Sigmund Freud

- Simone De Beauvoir

- Simone Weil

- Søren Kierkegaard

- Theodor Adorno

- Thomas Aquinas

- Thomas Hobbes

- Thomas Jefferson

- Thomas Kühn

- U.G. Krishnamurti

- Walter Benjamin

- Wilhelm Reich

- William James

- William Lane Craig

- Alain de Benoist

- Alan Turing

- Albert Camus

- Albertus Magnus

- Arthur Schopenhauer

- Auguste Comte

- Baruch Spinoza

- Bertrand Russell

- Cesare Beccaria

- Charles Sanders Peirce

- Daniel Dennett

- Edmund Burke

- Edmund Husserl

- Emile Durkheim

- Emma Goldman

- Francis Bacon

- Friedrich Engels

- Friedrich Hayek

- Friedrich Nietzsche

- George Berkeley

- George Herbert Mead

- George Santayana

- Georges Bataille

- Gilles Deleuze

- Giordano Bruno

- Gottfried Leibniz

- Hannah Arendt

- Henry David Thoreau

- Hildegard Of Bingen

- Immanuel Kant

- Iris Murdoch

- Jacques Derrida

- Jacques Lacan

- Jean Baudrillard

- Jean Jacques Rousseau

- Jean-Paul Sartre

- Jeremy Bentham

- Jiddu Krishnamurti

MacTutor

Abu ali al-husain ibn abdallah ibn sina (avicenna).

Destiny had plunged [ ibn Sina ] into one of the tumultuous periods of Iranian history, when new Turkish elements were replacing Iranian domination in Central Asia and local Iranian dynasties were trying to gain political independence from the 'Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad ( in modern Iraq ) .

... the power of concentration and the intellectual prowess of [ ibn Sina ] was such that he was able to continue his intellectual work with remarkable consistency and continuity and was not at all influenced by the outward disturbances.

... but he escaped to Isafan, disguised as a Sufi, and joined Ala al-Dwla.

... of a mysterious illness, apparently a colic that was badly treated; he may, however, have been poisoned by one of his servants.

... it is important to gain knowledge. Grasp of the intelligibles determines the fate of the rational soul in the hereafter, and therefore is crucial to human activity.

Ibn Sina sought to integrate all aspects of science and religion in a grand metaphysical vision. With this vision he attempted to explain the formation of the universe as well as to elucidate the problems of evil, prayer, providence, prophecies, miracles, and marvels. also within its scope fall problems relating to the organisation of the state in accord with religious law and the question of the ultimate destiny of man.

References ( show )

- A Z Iskandar, Biography in Dictionary of Scientific Biography ( New York 1970 - 1990) . See THIS LINK .

- Biography in Encyclopaedia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/biography/Avicenna

- S M Afnan, Avicenna: His life and works ( London, 1958) .

- M B Baratov, The great thinker Abu Ali ibn Sina ( Russian ) ( Tashkent, 1980) .

- M B Baratov, P G Bulgakov and U I Karimov ( eds. ) , Abu 'Ali Ibn Sina : On the 1000 th anniversary of his birth ( Tashkent, 1980) .

- M N Boltaev, Abu Ali ibn Sina - great thinker, scholar and encyclopedist of the Medieval East ( Russian ) ( Tashkent, 1980) .

- W E Gohlman ( ed. and trans. ) , The life of Ibn Sina ( New York, 1974) .

- L Goodman, Avicenna ( London, 1992) .

- D Gutas, Avicenna and the Aristotelian tradition ( Leiden, 1988) .

- I M Muminov ( ed. ) , al-Biruni and Ibn Sina : Correspondence ( Russian ) ( Tashkent, 1973) .

- S H Nasr, An Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines (1964) .

- B Ja Sidfar, Ibn Sina : Writers and Scientists of the East ( Moscow, 1981) .

- S Kh Sirazhdinov ( ed. ) , Mathematics and astronomy in the works of Ibn Sina, his contemporaries and successors ( Russian ) ( Tashkent, 1981) .

- V N Ternovskii, Ibn Sina ( Avicenna ) 980 - 1037 ( Russian ) , 'Nauka' ( Moscow, 1969) .

- G W Wickens ( ed. ) , Avicenna: Scientist and Philosopher (1952) .

- H F Abdulla-Zade, A list of Ibn Sina's work in the natural sciences ( Russian ) , Izv. Akad. Nauk Tadzhik. SSR Otdel. Fiz.-Mat. Khim. i Geol. Nauk (3)(77) (1980) , 101 - 104 .

- M A Ahadova, The part of Ibn Sina's 'Book of knowledge' devoted to geometry ( Russian ) , Buharsk. Gos. Ped. Inst. Ucen. Zap. Ser. Fiz.-Mat. Nauk Vyp. 1 (13) (1964) , 143 - 205 .

- M F Aintabi, Ibn Sina : genius of Arab-Islamic civilization, Indian J. Hist. Sci. 21 (3) (1986) , 217 - 219 .

- M A Akhadova, Some works of Ibn Sina in mathematics and physics ( Russian ) , in Mathematics and astronomy in the works of Ibn Sina, his contemporaries and successors ( Tashkent, 1981) , 41 - 47 ; 156 .

- M S Asimov, The life and teachings of Ibn Sina, Indian J. Hist. Sci. 21 (3) (1986) , 220 - 243 .

- M S Asimov, Ibn Sina in the history of world culture ( Russian ) , Voprosy Filos. (7) (1980) , 45 - 53 ; 187 .

- A K Bag, Ibn Sina and Indian science, Indian J. Hist. Sci. 21 (3) (1986) , 270 - 275 .

- R B Baratov, Ibn Sina's views on natural science ( Russian ) , Izv. Akad. Nauk Tadzhik. SSR Otdel. Fiz.-Mat. Khim. i Geol. Nauk (1)(79) (1981) , 52 - 57 .

- D L Black, Estimation ( wahm ) in Avicenna : the logical and psychological dimensions, Dialogue 32 (2) (1993) , 219 - 258 .

- O M Bogolyubov and V O Gukovich, On the thousandth anniversary of the birth of Ibn-Sina ( Avicenna ) ( Ukrainian ) , Narisi Istor. Prirodoznav. i Tekhn. 29 (1983) , 35 - 38 .

- E Craig ( ed. ) , Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy 4 ( London-New York, 1998) , 647 - 654 .

- O V Dobrovol'skii and H F Abdulla-Zade, The astronomical heritage of Ibn Sina ( Russian ) , Izv. Akad. Nauk Tadzhik. SSR Otdel. Fiz.-Mat. Khim. i Geol. Nauk (3)(77) (1980) , 5 - 15 .

- A Ghorbani and J Hamadanizadeh, A brief biography of Abu 'Ali Sina ( Ibn Sina ) , Bull. Iranian Math. Soc. 8 (1) (1980 / 81) , 33 - 34 .

- R Glasner, The Hebrew version of 'De celo et mundo' attributed to Ibn Sina, Arabic Sci. Philos. 6 (1) (1996) , 4 ; 6 - 7 ; 89 - 112 .

- N G Hairetdinova, Trigonometry in the works of al-Farabi and Ibn Sina ( Russian ) , Voprosy Istor. Estestvoznan. i Tehn. Vyp. 3 (28) (1969) , 29 - 31 .

- M M Hairullaev and A Zahidov, Little-known pages of Ibn Sina's heritage ( correspondence and epistles of Ibn Sina ) ( Russian ) , Voprosy Filos. (7) (1980) , 76 - 83 .

- A Kahhorov and I Hodziev, Ibn Sina - mathematician ( on the occasion of the 1000 th anniversary of his birth ) ( Russian ) , Izv. Akad. Nauk Tadzik. SSR Otdel. Fiz.-Mat. i Geolog.-Him. Nauk (3)(65) (1977) , 121 - 124 .

- A de Libera, D'Avicenne à Averroès, et retour : Sur les sources arabes de la théorie scolastique de l'un transcendantal, Arabic Sci. Philos. 4 (1) (1994) , 6 - 7 , 141 - 179 .

- M E Mamura, Some aspects of Avicenna's theory of God's knowledge of particulars, J. Amer. Oriental Soc. 82 (1962) , 299 - 312 .

- P Morewedge, Philosophical analysis and Ibn Sina's 'Essence-Existence' distinction, J. Amer. Oriental Soc. 92 (1972) , 425 - 435 .

- H R Muzafarova, Basic planimetry concepts of Euclid's 'Elements' as presented by Qutb al-Din al Shirazi, Ibn Sina and their contemporaries ( Russian ) , Izv. Akad. Nauk Tadzhik. SSR Otdel. Fiz.-Mat. Khim. i Geol. Nauk (3)(77) (1980 , 16 - 23 .

- S H Nasr, Ibn Sina's oriental philosophy, in History of Islamic philosophy ( London, 1996) , 247 - 251 .

- F Rahman, Essence and existence in Avicenna, Medieval and Renaissance Studies 4 (1958) , 1 - 16 .

- I W Rath, Wie die Logik auf vor-Urteilen beruht : Überlegungen zu Aristoteles, zu Ibn Sina und zur modernen Logik, Conceptus 28 (72) (1995) , 1 - 19 .

- N Rescher, Avicenna on the logic of 'conditional' propositions, Notre Dame J. Formal Logic 4 (1963) , 48 - 58 .

- A I Sabra, The sources of Avicenna's 'Usul al-Handasa' ( Geometry ) ( Arabic ) , J. Hist. Arabic Sci. 4 (2) (1980) , 416 - 404 .

- A V Sagadeev, Ibn Sina as a systematizer of medieval scientific knowledge ( Russian ) , Vestnik Akad. Nauk SSSR (11) (1980) , 91 - 103 .

- A S Sadykov, Ibn Sina and the development of the natural sciences ( Russian ) , Voprosy Filos. (7) (1980) , 54 - 61 ; 187 .

- H M Said, Ibn Sina as a scientist, Indian J. Hist. Sci. 21 (3) (1986) , 261 - 269 .

- G Saliba, Ibn Sina and Abu 'Ubayd al-Juzjani : the problem of the Ptolemaic equant, J. Hist. Arabic Sci. 4 (2) (1980) , 403 - 376 .

- A N Shamin, The works of Ibn Sina in Europe in the epoch of the Renaissance ( Russian ) , Voprosy Istor. Estestvoznan. i Tekhn. (4) (1980) , 73 - 76 .

- S Kh Sirazhdinov, G P Matvievskaya and A Akhmedov, Ibn Sina and the physical and mathematical sciences ( Russian ) , Voprosy Filos. (9) (1980 , ) 106 - 111 .

- S Kh Sirazhdinov, G P Matvievskaya and A Akhmedov, Ibn Sina's role in the history of the development of the physico-mathematical sciences ( Russian ) , Izv. Akad. Nauk UzSSR Ser. Fiz.-Mat. Nauk (5) (1980) , 29 - 32 ; 99 .

- Z K Sokolovskaya, The scientific instruments of Ibn Sina ( Russian ) , in Mathematics and astronomy in the works of Ibn Sina, his contemporaries and successors ( Tashkent, 1981) , 48 - 54 ; 156 .

- T Street, Tusi on Avicenna's logical connectives, Hist. Philos. Logic 16 (2) (1995) , 257 - 268 .

- B A Tulepbaev, The scholar- encyclopedist of the medieval Orient Abu Ali Ibn Sina ( Avicenna ) ( Russian ) , Vestnik Akad. Nauk Kazakh. SSR (11) (1980) , 10 - 13 .

- A Tursunov, On the ideological collision of the philosophical and the theological ( on the example of the creative work of Ibn Sina ) ( Russian ) , Voprosy Filos. (7) (1980) , 62 - 75 ; 187 .

- A U Usmanov, Ibn Sina and his contributions in the history of the development of the mathematical sciences ( Russian ) , in Mathematics and astronomy in the works of Ibn Sina, his contemporaries and successors ( Tashkent, 1981) , 55 - 58 ; 156 .

Additional Resources ( show )

Other pages about Avicenna:

- See Avicenna on a timeline

- Heinz Klaus Strick biography

- Miller's postage stamps

Other websites about Avicenna:

- Dictionary of Scientific Biography

- Encyclopaedia Britannica

- A Google doodle

- Google books

- MathSciNet Author profile

- Google doodle

Honours ( show )

Honours awarded to Avicenna

- Lunar features Crater Avicenna

- Popular biographies list Number 114

- Google doodle 2018

Cross-references ( show )

- History Topics: The Arabic numeral system

- Other: Jeff Miller's postage stamps

- Other: Most popular biographies – 2024

- Other: Popular biographies 2018

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

- Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Ibn Sina’s Natural Philosophy

Ibn Sīnā (980–1037)—the Avicenna of Latin fame—is arguably the most important representative of falsafa , the Graeco-Arabic philosophical tradition beginning with Plato and Aristotle, extending through the Neoplatonic commentary tradition and continuing among philosophers and scientists in the medieval Arabic world. Avicenna’s fame in many ways is a result of his ability to synthesize and to extend the many intellectual trends of his time. These trends included not only the aforementioned Greek traditions, but also the Islamic theological tradition, Kalām, which was emerging at the same time that the Greek scientific and philosophical texts were being translated into Arabic. Avicenna’s own unique system survives in no fewer than three philosophical encyclopedias— Cure (or The Healing ), The Salvation and Pointers and Reminders . Each provides a comprehensive worldview ranging from logic to psychology, from metaphysics to ethics (although admittedly, ethics is treated only scantly). At the middle of this Avicennan worldview is natural philosophy or physics ( ʿilm ṭabīʿī ). The significance of natural philosophy, and Avicenna’s physics in particular, is twofold. First, it represents Avicenna’s best attempt to explain the sensible world in which we live and to provide the principles for many of the other special sciences. Second, Avicenna’s natural philosophy lays the foundations for a full understanding of his advancements in other fields. Examples of this second point include, but are certainly not limited to, the ramifications of logical distinctions for the sciences, the physical basis of psychology (as well as the limitation of physicalism for a philosophy of mind) and the introduction of key problems that would become the focal points of metaphysical inquiry. In all cases, Avicenna assumes his readers know their physics.

As others before him, Avicenna understands natural philosophy as the study of body insofar as it is subject to motion. Thus the present entry, after an overview of medieval physics generally, turns to Avicenna’s account of the nature of body followed by his account of motion. Central to an account of bodies is whether they are continuous or atomic, and so one must consider Avicenna’s critique of atomism and his defense and analysis of continuous magnitudes. The discussion of motion follows in two steps: one, his account of motion and, two, his account of the conditions for motion. The section on motion concentrates on Avicenna’s unique understanding of the Aristotelian definition of motion as the first actuality of potential as potential, while the conditions for motion involve his understanding of time and place.

1.1 Physical Causes and the Principles of Nature

2.1 general background, 2.2.1 kalām atomism, 2.2.2 avicenna’s criticisms of atomism, 2.3 continuity, 2.4 infinity and the shape of the cosmos, 2.5.1 the motions and qualitative powers of the elements.

- 2.5.2 Natural Minimums

- 3.1 Motion as First Actuality

- 3.2 Two Senses of Motion: Traversal and Medial Motion

- 3.3.1 The Genus and Species of Motion

- 3.3.2 An Analysis of Positional Motion

- 4.1 Place and Void

- 4.2 Time and the Age of the Universe

- al-Kindī

- Secondary Sources

- Other Internet Resources

- Related Entries

1. Medieval Physics

For Avicenna, the proper subject of natural philosophy, in its broadest or most general sense, is body insofar as it is subject to motion. Beyond general physics ( al-samāʿ al-ṭabīʿī ), the physical sciences are further divided into various special sciences distinguished according to either the kind of motion investigated or the kind of body treated. While Avicenna himself does not explicitly identify his decision procedure for dividing the special natural sciences, it is evidenced in the way that he divides up the books of his monumental encyclopedia of philosophy and the sciences, The Cure (al-Shifāʾ) . For example, his book On the Heavens and Earth (Fī l-Samāʾ wa-l-ʿālam) from The Cure generally treats rectilinear and circular motion; On Generation and Corruption (Fī l-Kawn wa-l-fasād) deals with change as it occurs in the Aristotelian category of substance, whereas On Actions and Passions (Fī l-Afʿāl wa-l-infiʿālāt) concerns how bodies are affected and affect one another with respect to, for example, the primary qualities of hot-cold and wet-dry, which they possess. Avicenna distinguishes additional special natural sciences according to the specific sort of body being considered, namely, whether the body is inanimate—generally the subject matter of Meteorology ( al-Maʿādin wa-l-āthār al-ʿulwiyya )—or the body is animate—the subject of psychology (literally, the science of the soul or animating principle). Avicenna further divides the study of living bodies into general psychology ( ʿilm al-nafs ), botany ( al-nabāt ) and zoology ( ṭabāʾiʿ al-hayawān ). The focus of the present study is limited primarily to Avicenna’s general natural philosophy, although at times the discussion is supplemented with developments in the special physical sciences.

The hallmark of natural philosophy and indeed of any science (sing. Gk. epistēmē , Ar. ʿilm ) for Avicenna and the entire Aristotelian tradition is to uncover and to grasp the basic causes (sing. ʿilla ) of the phenomenon under consideration. Like Aristotle before him, Avicenna identifies four sorts of causes: the matter, form, agent (or efficient cause) and end (or final cause) (Avicenna, [Ph], 1.10 and Avicenna, [MPh], bk. 6). For Avicenna the material cause is a wholly inert substratum for form. The matter explains any passivity or potentiality to be acted upon that a body might have. The form ( ṣūra ) is the cause, primarily, of a body’s being the actual kind or species that it is and performing the various actions associated with that species; secondarily, a form might be the cause of the accidental features and determinations that belong to that body (Avicenna occasionally uses hayʾa for this second sense of form). In general then, the form is the cause of any actuality, that is positive features or actions, that the body has or does. The efficient cause accounts for a body’s undergoing motion and change (or even for its existence), while the final cause is that for the sake of which the form occurs in the matter.

Unlike Aristotle, Avicenna also recognizes a broader division of causes into physical causes and metaphysical causes (Avicenna, [Ph], 1.10 [3]). The distinction is best approached by considering the Aristotelian division between substances and accidents as found in the ten categories. (Within the Aristotelian tradition, including Avicenna, the ten categories purport to provide the broadest classification of ways things are found ( mawjūd ) in the world; Avicenna, [Cat], 1.1 and [MPh], 3.1.) The primary category is that of substance, which for Avicenna is the existence that belongs to a thing through itself, for example, the existence that belong to a human as human or a dog as dog (Avicenna, [MPh], 2.1 [1–2]). Accidents are what exist in another, namely, in a substance, and include a substance’s quantity, quality, relation, where, when, position, possession, activity and passivity. Metaphysical causes involve what accounts for the existence and continual conservation of a substance, or, more exactly, of a concrete particular. Physical causes in contrast involve those factors that bring about changes in the accidental features of bodies, primarily changes of quality, quantity, location and position. For example, a father is responsible for seeing that his semen becomes located within the mother, and the mother ensures that the right womb temperature for the fetus is maintained and that the fetus is fed. Location, temperature, possession of nutriment and the like belong to categories of accidents, not to that of substance. Consequently, for Avicenna the father and mother are most properly physical agents, that is, the cause of accidental changes that prepare the matter for the form. As such the parents are not the cause of the existence of the offspring’s species form by which it is the specific substance it is. Instead, the metaphysical agent—the one who imparts the species form to the matter such that there comes to be a substance of the same kind as the parents—is a separate (immaterial) agent, which Avicenna calls the Giver of Forms (Avicenna, [Ph], 1.10 [3]; [AP], 2.1; [MPh], 6.2 [5] & 9.5 [3–4]). [ 1 ]

Regardless of whether one is considering physical or metaphysical causes, any motion or change (whether of some specific existence itself or just of some new accident), Avicenna explains, requires three things: (1) the form that comes to be as a result of the change, (2) the matter in which that form comes to be and (3) the matter’s initial privation of that form (Avicenna, [Ph], 1.2 [12–13]). These three—the form, matter and privation—are frequently referred to, following Aristotle, as “principles of nature” (cf. Aristotle, Physics , 1.7). While Avicenna happily agrees that these three factors are present in every instance of something’s coming to be after not having been, he is not as happy as to whether all three of these features are equally “principles” (sing. mabdaʾ ). His concern is that, strictly speaking, causes and principles exist simultaneous with their effects, whereas privation is only ever prior to the change and passes away with the change (Avicenna, [Ph], 1.3 [14]; McGinnis 2012, Lammer 2018, §3.3). More properly speaking, Avicenna contends, privation is a precondition for change rather than a principle. Still, he concedes that if one is lax in one’s use of “principle” so as to understand a principle as “whatever must exist, however it might exist, in order that something else exists, but not conversely” ( ibid ) privation would count as a principle of change. Avicenna reasons thusly: The elimination of the privation from something as changeable renders that thing no longer changeable, whereas the elimination of that changeable thing itself does not eliminate the privation. In other words, insofar as something is changeable, it depends on or requires that there be some privation. Conversely, privation does not depend on and does not require that there be anything changeable. For example, for Avicenna, the celestial Intellects—think Angelic host—are not subject to change; nonetheless, they all possess some privation of existence and perfection, which is found in God. Thus privation has a certain ontological priority to the changeable. There can be privation without the changeable, but there cannot be the changeable without privation.

Closely related to causes and principles is the notion of a nature (Gk. phusis , Ar. ṭabīʿa ), for Aristotle defined a nature as “a principle of being moved and being at rest in that to which it belongs primarily, not accidentally but essentially” (Aristotle, Physics , 2.1, 192b21–3). Before commenting Aristotle’s definition of nature, Avicenna begins his chapter “On Defining Nature” from The Cure (Avicenna, [Ph], 1.5) by distinguishing between the motions and actions that proceed from a substance owing to external causes and those that proceed from a substance owing to the substance itself. For instance, water becomes hot as a result of some external heat sources, whereas it becomes cool of itself. Avicenna next identifies two sets of parameters for describing those motions and actions that proceed from a substance owing to that substance itself. They may either proceed from the substance as a result of volition or without volition. Additionally they may proceed either uniformly without deviation or non-uniformly with deviation. Thus there are four very general ways for dividing and describing all the motions and actions that are found in the cosmos.

(1) Motions and actions may proceed as a result of volition and do so in a uniform and unvarying way, such as the motion of the heavenly bodies. The internal cause in these cases, Avicenna tells us, is a celestial soul. [ 2 ] (2) Other motions and actions may proceed as a result of volition but do so in a non-uniform and varying way, like the motions and actions of animals; the internal cause in these cases is an animal soul. (3) Again, other motions and actions may not proceed as a result of volition and are non-uniform and varying, like plant growth; the internal cause in these cases is a plant soul. Finally (4) some motions and actions may proceed without volition while doing so in a uniform and unvarying way, like the downward motion of a clod of earth and the heating of fire; the internal cause in these cases is a nature.

Next, he turns to Aristotle’s own account of nature and begins by chiding Aristotle for his cavalier assertion that trying to prove that natures exist is a fool’s errand, since it is self-evident that things have such (internal) causes. While we are immediately aware of motions and actions that seemingly proceed from substances of themselves, that there truly exist internal causes of these actions and motions is certainly in need of demonstration. Indeed, one who first encounters the motion of a magnet, Avicenna gives as an example, might imagine that its motion is a result solely of itself rather than of iron in the vicinity. Moreover, during Avicenna’s time the question of whether natures existed at all was a hotly debated topic between philosophers in the Graeco-Arabic tradition, like Avicenna, and thinkers in the Kalām tradition, the tradition of Islamic speculative theology and cosmology.

Proponents of the Kalām tradition, such as al-Bāqillānī (950–1013) and al-Ghazālī (1058–1111), had a two-stage critique. First, anticipating Hume by at least 700 years, these thinkers noted that observation alone could not distinguish between causal connections and mere constant conjunctions. (A contemporary example often found in statistic classes is that the summer sun’s heat seems to be causally connected with ice cream’s melting, whereas eating ice cream is only constantly conjoined, at least in the US, with an increase in violent crimes.) Observation alone, these thinkers warn us, cannot determine, for example, whether the cotton’s burning, which follows upon placing fire in the cotton, or intoxication, which follows upon imbibing alcohol, is causally connected with the natures of fire and alcohol respectively, or whether these sets of events are merely constantly conjoined. Indeed the concurrence of two events may be a result of God’s habit or custom ( ʿāda or sunna ) of causing the one event together with the other. While one might think that appealing to God to explain the various mundane events that we constantly observe around us is extravagant, Kalām thinkers countered that it was in fact the philosophers who are ontologically profligate, for the theologians assume only one class of causes, namely, willful agent(s), whereas the philosophers are committed to two ontologically distinct classes of causes, if not more. This point leads to the second stage of the Kalām critique of natures. God’s (omnipotent) causal power extends to every actual or even possible event. God’s causal power is either sufficient to produce these effects or it is not. If God’s power is not sufficient, then either the deity needs the added “boost” of natural powers, or it needs natures as a tool or instrument, etc. This later position flirts with impiety. If, however, God’s causal power is sufficient to produce every effect and there are also natures, functioning as internal causes, every event is over-determined. Indeed it is not clear at all what causal role natures have to play. A principle of parsimony, so the Kalām critique concludes, suggests that natures be jettisoned and one reserve all causal power to God alone. While Avicenna addresses the issue of the existence of natures and offers up a demonstration for their existence in the Metaphysics (4.2, 9.2 & 9.5; also see Dadikhuda 2019), he also notes that the science of physics is not the proper place to undertake such an enterprise. That is because the existence of a science’s subject matter, Avicenna notes following Aristotle, is never demonstrated within that very science itself but only in a higher science.

Having set aside the issue of whether natures exist and for present purposes posits that they do, Avicenna now unpacks Aristotle’s definition. Before considering his analysis, however, it should be noted that there is a certain ambiguity in Aristotle’s overall treatment of nature. The ambiguity involves whether nature should be taken in a passive sense: is nature a cause of a substance’s being moved ? Or, alternatively, should nature be taken in an active sense: is a nature a cause of a substance’s (self) motion? In Physics , 2.1, the text where Aristotle defines nature, he suggests, although does not explicitly claim, that nature can be understood in both senses: a passive nature, which corresponds with a substance’s matter, and an active nature, which corresponds with the form of that substance, and so is a cause of its motion. In contrast, later in the Physics , he argues that natures should be understood exclusively as passive (Aristotle, Physics , 8.4, 225b29–256a3). This conclusion follows upon Aristotle’s principle that everything that is moved must be moved by something, which he established at Physics , 7. The principle is significant for a key element in Aristotle’s his natural philosophy, namely, his proof for an unmoved mover. (The unmoved mover is intended to explain why there is motion at all.) The aforementioned principle is significant because if all natural substances were capable of self motion, it is no longer clear that there is a need for an unmoved mover to account for the motion of the cosmos. This ambiguity in Aristotle account of nature, namely, whether nature is an active source of moving or a passive factor of being moved, was the source of much discussion among Aristotle’s subsequent Greek commentators, who included Alexander of Aphrodisias (ca. 200 CE) and the late Christian, Neoplatonic Philosopher John Philoponus (ca. 490–570). (For more detailed studies of this tradition see Macierowski & Hassing 1988, Lang 1992, 97–124 and Lammer 2015, 2018, ch. 4).

Aristotle’s definition of nature as it came down to Avicenna in Arabic literally translates into English as “the primary principle of motion and rest in that to which it belongs essentially rather than accidentally” (quoted in Avicenna, [Ph], 1.5 [4]). [ 3 ] A “principle of motion,” Avicenna tells us, means “an efficient cause from which proceeds the production of motion in another, namely, the moved body” (ibid). Immediately we recognize that a nature for Avicenna can be understood as an active cause that produces motion. Such a position is to be contrasted with Aristotle’s claim at Physics 8.4 that a nature is not an internal cause of a thing’s motion, but of its being moved . [ 4 ] Next we learn that “primary” in the definition means that the nature causes the motion in the body without some further intermediary cause. As for “essentially,” (Gk. kath hauto , Ar. bi-dhātihi ) it is an equivocal notion with two senses, Avicenna tells us. In one sense, “essentially” is predicated relative to the mover, while in another sense it is predicated relative to what is subject to motion, namely, the body. Thus, on the one hand, when “essentially” is said relative to the mover, a substance’s nature, as efficient cause, essentially produces those motions and actions that typify the substance as the kind that it is. On the other hand, when “essentially” is said relative to the body, it refers to the body’s essentially being subject to those naturally characteristic motions and actions. In effect, by distinguishing the two relative senses of “essentially,” Avicenna has made room for Aristotle’s definition to include nature as an active and as passive principle. To sum up, for Avicenna, a substance’s nature is the immediate efficient cause for all of the naturally characteristic actions and motions it produces (active nature) as well as explaining why the body is subject to those characteristic actions and motions (passive nature).

2. Bodies and Magnitudes

With the distinction between nature as active and nature as passive in place, it becomes clear why Avicenna identifies the proper subject matter of natural philosophy with body insofar as it is subject to motion, for the science of physics studies nature in both of its active and passive senses. Nature as passive refers to that which is subject to motion, namely, bodies, while nature as active refers to the causes and conditions of the motions and actions that bodies naturally undergo. In this section, I begin with Avicenna’s general introduction to bodies. I then take up his critique of atomism, specifically as that theory was developed within Kalām. Thereafter, I turn to Avicenna’s theory of the continuity of magnitudes and his conception of infinity, concluding with a brief survey of his theory of the elements.

Sensible body ( jism or occasionally jirm ), one can assume, is an aggregation of parts. Starting from this assumption, Avicenna next says of the body that it either (1) has actual parts or (2) has no actual parts. Avicenna effectively divides the logical space for a discussion of the aggregation of body into two categorical propositions: either “Some parts in a body are actual” or “No parts in a body are actual.” These are logically contradictory propositions, and so along one dimension they exhaust all logically possible options. In the case of “some parts,” the obvious question is, “How many?” where “finite” and “infinite” exhaust the possible options. Of course, the question, “How many?” is irrelevant when applied to no or 0 parts. Thus, there are three possible positions: body is an aggregate of (1) a finite number of actual parts, a position identified with that of the atomists; (2) an infinite number of actual parts, a position identified with that of Ibrāhīm al-Naẓẓām (c. 775–c. 845); (3) no actual parts, a position associated with the Aristotelian tradition and the contention that bodies are continuous and so not an aggregate of actual parts, even if potentially divisible ad inifinitum.

Avicenna makes short work of (2), al-Naẓẓām’s position (Avicenna, [PR], namaṭ 1, ch. 2; and [Ph], 3.4 [1]). The parts are units of the whole, which must have either no magnitude or some magnitude. If the units have no magnitude, then while multiplying them may increase the number of units present in a body, it will not increase the size of the body. Consequently, bodies would not have any magnitude, an obviously false conclusion. If the units have some magnitude, be it ever so small, and the body is composed of an actual infinity of these units, then complains Avicenna, “the relation of the finite units to the infinite units would be the relation of a finite to a finite, which is an absurd contradiction” (Avicenna, [PR], namaṭ 1, ch. 2, p. 162). For instance, assume that al-Naẓẓām’s unit measures some extremely small yet positive amount of distance, for example, 1.5 x 10 -35 of a meter, then:

∞ al-Naẓẓām’s-units : 1 m :: 1.5 x 10 -35 al-Naẓẓām’s-units : 1 m.

Thus ∞ : 1.5 x 10 -35 , that is, an infinite is proportional to a finite, which, as Avicenna notes, is absurd.

Avicenna’s more important target was Kalām atomism, which is significantly different from the Democritean atomism, which Aristotle had criticized. Thus, let us consider it quickly before turning to Avicenna’s critique of atomism.

2.2 Avicenna on Atomic/Discrete Magnitudes

Aristotle had in his physical writings addressed and critiqued atomism (e.g., Aristotle, Physics , 6.1 and On Generation and Corruption , 1.2). In the time between Aristotle and Avicenna, however, there were a number of developments in atomic theory both by Epicurus, one generation after Aristotle, and by Muslim theologians, that is, proponents of Kalām, most of whom were atomists (Dhanani 1994, 2015). As a result, Avicenna’s critique of atomism needed to address new innovations and challenges. One such innovation, which can be traced back to the Greek world, is a distinction between physical divisibility and conceptual divisibility. Thus, for example, the atoms of Democritus (d. 370 BCE) have as one of their properties shapes. If atoms have a shape and to have a shape is to have definite limits, then one might reason that Democritean atoms have distinct limits into which they can at least be conceptually divided, even if not physically divided. Aristotle in fact exploited this point in his critique of Democritus. In contrast, the minimal parts of Epicurus (d. 270 BCE) had no shape, and so were not subject to the same criticism. Indeed, Epicurean minimal parts are purportedly not merely physically indivisible but also conceptually indivisible. To provide a rough and ready image of an Epicurean minimal part, one might think of the surface thickness of a plank, and the plank itself as the aggregation of such surfaces. For example, then, when the surfaces of two planks are brought together tightly, intuitively one may think that the two surfaces remain two distinct physical things; the bottom of the top plank, for instance, is distinct from the top of the bottom plank. When some enormous number of these surfaces is aggregated, a plank with a definite thickness, one might imagine, results. So how thick are these surfaces? One cannot fathom, but again being so thin that dividing it further is inconceivable is the very point of Epicurus’ minimal parts. Whatever the chain of transmission, it was something much like Epicurus’ minimal parts that Muslim atomists identified with their atoms, or more precisely, indivisible parts ( sing. al-juzʾ alladhī lā yatajazzaʾu )—a spatial magnitude that was not merely physically indivisible but also conceptually indivisible.

Another difference between the theory of atomism that Aristotle addressed and the one that Avicenna does is the very nature of the atoms themselves. Democritus’ atoms with their differences in shapes as well as differences in possible arrangement and positions are best considered as corpuscles, that is, small bodies. Thus when speaking of Democritus, we can speak of “corpuscular atomism.” Such is not necessarily the case with Epicurean minimal parts or Kalām atoms, which, while making up the parts of bodies, were not themselves considered bodies. While there is some dispute about this point concerning Epicurus, Kalām atomists are fairly consistent in saying that the sole property of their atoms is that they occupy space ( mutaḥayyiz ) but otherwise lack any other determinations. In fact, Kalām atoms might best be thought of as a matrix making up all space, with the individual atom representing the smallest spatial magnitude necessary for the occurrence of some co-incidental event, determination or accident, like being red or hot or wet or even possessing power. In this respect, Kalām atoms are comparable to the pixels on a modern-day TV or computer screen. The two are comparable in that both are the smallest relevant units in which a sensible effect occurs, whether some color for modern pixels or any accident more generally for Kalām atomists. Consequently, this variety of atomism might be called “pixelated atomism” to contrast it with the corpuscular atomism that had been the target of Aristotle’s criticisms. The significant point is that Avicenna could not simply appeal to Aristotle and his attack on corpuscular atomism when critiquing atomism as he found it.

Regardless of what form of atomism one endorsed, a common argument in atomism’s favor appeals to the notion of a sensible body’s being an aggregation of parts. The argument is directed against the idea that a continuous magnitude, which for the philosophers included the natural sensible bodies that make up the world, can be potentially divisible ad infinitum (cf. Aristotle, Physics 3.7, 207b16). The most general form of the argument rests on two principles: (1) the impossibility of an actual infinity, a premise that even most Aristotelians accepted; and (2) an analysis of potentiality in terms of an agent’s power, namely, to say that some action φ is potential is to say that there exists an agent who has the power actually to do φ. As part of a reductio-style argument, one is asked to assume (3), bodies are potentially divisible infinitely. In that case, from (2), there must exist some agent (e.g., God) that can actually bring about the division. So let the agent enact the potential division. Either the result is an actually infinite number of parts or a finite number of parts. From (1), recall, an actual infinity is impossible. Therefore, the totality of potential parts that actually can be produced from the division is finite, but it was assumed that they were infinite, a contradiction. Since (1), (2) and (3) are mutually incompatible, one of these assumptions must be false. The atomists point to the assumption of infinite divisibility and a potentially infinite number of parts. Thus, the argument concludes, the parts from which sensible bodies are aggregated must be finite, whether actually or potentially.

Avicenna’s response to this argument against the potentially infinite divisibility of bodies is considered when discussing his theory of continuity . Prior to that, his reasons for rejecting atomism must be examined. To start, Avicenna accepts that division with respect to body is of two sorts: physical division and conceptual division. In physical division, there is the actual fragmentation of a body, with the parts of the body becoming physically separated and at a distance from one another. An example would be when one takes a single quantity of water and places part of it in one vessel and the other part in another vessel. Avicenna concedes that it well may be the case that bodies have some physical limit beyond which they no longer can be physically divided and still remain the same sort of body. To provide an example of Avicenna’s point, our quantity of water can be divided as water until one reaches a single water molecule; division beyond that point, while producing hydrogen and oxygen atoms, does not produce smaller particles of water. A single water molecule, then, is physically indivisible as water; it no longer remains as water after any further division. Still, inasmuch as a single water molecule occupies some space, however small, one can conceive of half of that water molecule, and so it is conceptually divisible qua magnitude. Whether there actually are such physically indivisible units, Avicenna insists, requires proof, which I consider when looking at Avicenna’s elemental theory .

The form of atomism that Avicenna rejects is that there exist minimal parts that cannot even be conceptually divided further. These are the minimal parts of Epicurus and the atoms of Kalām. Avicenna’s arguments against this conception of atomism takes two forms: one, arguments showing that there is a physical absurdity with such atoms and, two, arguments showing that this form of atomism is incompatible with our best mathematics, namely, that of Euclidean geometry. The following two examples give one a sense of how Avicenna’s physical-style and mathematical-style criticisms work (Avicenna, [PR], namaṭ 1, ch. 1 and [Ph], 3.4; Lettinck 1988). While all the arguments considered are specifically directed toward a theory of pixilated atomism, they apply equally well to corpuscular atomism. Additionally, Avicenna has a series of arguments, not considered here, showing the absurdities that would follow on the purported motion of corpuscular atoms.

While some of Avicenna’s physical-style arguments are quite complex and sophisticated, showing that the aggregation of bodies would simply be impossible on the Kalām atomists’ view (an example can be found in Section 2.3 of the entry on Arabic and Islamic natural philosophy and natural science ), the following thought experiment is perhaps more intuitively obvious. Posit a sheet of conceptually indivisible atoms between yourself and the sun. Certainly the side facing the sun is distinct from the side facing you, for if the side that the sun is illuminating is the very same side upon which you are gazing, there is no sense in which the sheet of atoms is between you and the sun. Thus on the assumption that it is physically possible for this sheet to exist between you and the sun, all the atoms composing the sheet have a sun-side and a you-side, and these two sides are distinct. Purportedly, conceptually indivisible atoms have been divided, a contradiction.

Avicenna’s mathematical-style critique of Kalām atomism frequently appeal to issues associated with incommensurability. In this vein he argues that such geometrical commonplaces as diagonals and circles would be impossible on the assumption of conceptually indivisible atoms. For example, in the pixilated atomism of the Kalām, the atoms might be thought to form a three-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system with each atom corresponding to some ordered triplet on this space. A two-dimensional plane, then, would look something like a chessboard. Avicenna now has us describe a right isosceles triangle on this chessboard, setting the two equal sides, for instance, at 3 units. Given the Pythagorean Theorem, A 2 + B 2 = C 2 , we should be able to solve for the length of the hypotenuse, which is √18 ≈ 4.25. Avicenna, next observes that assuming Kalām atomism, the hypotenuse of our triangle must fall either well below the solution given by the Pythagorean theorem—namely, it would be 3 units if one just counts the 3 squares along the diagonal of a 3x3 chessboard—or significantly exceed it—for instance 6 units, if the atoms can somehow be stair stepped. Alternatively, one might consider units smaller than the atoms, but such a move is to give up atomism. Kalām atomism, then, cannot even approximate the answer of the Pythagorean Theorem, and yet the Pythagorean Theorem is arguably the most well-proven theorem in the history of mathematics. Given the choice between a dubious physical theory and our best mathematics, Avicenna sides with Euclidean geometry and its assumption of continuous magnitudes. [ 5 ]

Having rejected atomism, with its central claim that sensible bodies must be aggregates of a finite number of conceptually indivisible parts, Avicenna must explain and defend his preferred account of bodies. Avicenna adopts a modified form of Aristotle’s theory of the continuity of bodies. Aristotle himself had provided no fewer than three different accounts of continuity (Gk. sunecheia , Ar. ittiṣāl ):

- AB is continuous iff AB can be divided into things always capable of further division ( Physics , 3.7 & De Caelo , 1.1)

- A is continuous with B iff the extremities of A and B are one and the same ( Physics , 6.1)

- A is continuous with B iff there is a common boundary at which they join together ( Categories , 6)

Precisely because these three accounts are different, Avicenna starts his own discussion of continuity, claiming that “being continuous is an equivocal expression that is said in three ways” (Avicenna, [Ph], 3.2 [8]). Two of these senses, he continues, are relative notions, while only one, i.e., (3) above, identifies the true essence of what it is to be continuous. In fact, he even goes as far as to say that account (1) is not truly a definition of being continuous at all; rather, it is a necessary accident of the continuous that must be demonstrated, a point to which I return when I look at what Avicenna considers to be the proper account of continuity.

As for the relative notions of continuity, the explanations can be quick. First, discrete objects might be said to constitute a continuous whole relative to a motion. For example, all the connected cars on a moving locomotive are clearly distinct and separate things, and yet they move together as a continuous whole. Second, discrete objects might be said to be continuous according to Aristotle’s definition (2) relative to some shared extremity. For example, for any angle ∠ABC greater than or less than 180°, the lines AB and BC share one and the same extremity, B, and yet are distinct and jointed. Neither of these senses is strictly speaking the target of the atomist’s critique nor the thesis concerning the continuity of bodies and magnitudes that Avicenna (or other Aristotelians) is keen to defend. Thus for Avicenna only (3), that two things are continuous if and only if there is a common boundary at which they join together, captures the proper definition of continuity.

A continuous sensible body (or any magnitude), Avicenna insists, must ultimately lack any parts and instead must be considered entirely as a unified whole. Admittedly, one can posit parts in this unified whole, like the left-part and the right-part, but such accidental parts are wholly the result of one’s positing and they vanish, claims Avicenna, with the cessation of the positing.

[Such parts are] like what happens when our estimative faculty imagines or we posit two parts for a line that is actually one, where we distinguish one [part] from the other by positing. In that way, a limit is distinguished for [the line] that is the same as the limit of the other division. In that case, both are said to be continuous with each other. Each one, however, exists individually only as long as there is the positing, and so, when the positing ceases, there is no longer this and that [part]; rather, there is the unified whole that actually has no division within it. Now, if what occurs through positing were to be something existing in the thing itself and not [merely] by positing, then it would be possible for an actually infinite number of parts to exist within the body (as we shall explain), but this is absurd (Avicenna, [Ph], 3.2 [8]).

To press Avicenna’s point a bit further, a continuous body has no parts in it, not even potential parts, if by “potential parts” one means points or the like latent within the body waiting for some power to actualize them or divide the body at them. To appreciate Avicenna’s point here fully, a few words must be said about his conception of the form-matter constitution of bodies and the relation of his view of continuity to psychological processes.

Like Aristotle and other Aristotelians both before and after him, Avicenna is convinced that bodies are constituted of matter and form. If one considers just body as such, that is, disregarding any specific kind of body it might be, then this absolute body, Avicenna tells us, is a composite of matter ( hayūlā ) and the form of corporeality ( ṣūra jismiyya ). Avicenna conceives matter as wholly passive, having no active qualities or features. (For discussion’s of Avicenna theory of matter see Hyman 1965; Buschmann 1979; Stone 2001; McGinnis 2012; but also see Lammer 2018, §3.2 for corrections of some of these earlier views.) In fact, Avicennan matter has no positive characterizations of its own at all by which it can be defined; rather, for Avicenna, matter is best understood solely in relation to the forms by which it is actualized and informed. Avicenna’s matter, then, is intimately linked with relative privation ( ʿadam ), that is, some lack, which under the right conditions can be realized. Given matter’s essentially privative character, it, then, cannot be the explanation for a sensible body’s having the positive characteristics of being unified and one, nor the cause of that body’s being extended so as to be subject to division. Instead, according to Avicenna, what makes a body a unified whole and subject to division is its form of corporeality.

For a determinate body to exist at all, Avicenna believes, it must have a determinate shape, and so be three dimensional, and so be localized in space. Both of these features are the result of its corporeal form (For a fuller discussion see Hyman 1965; Shihadeh 2014; Lammer 2018, §3.1). When the form of corporeality comes to inform matter, there comes to be a single unified body, existing on account of its particular and individual form of corporeality. Should the body be physically divided, the particular and individual form of corporeality is not so much divided as destroyed and replaced with two new particular and individual forms of corporeality corresponding with two new bodies. It is essentially the form of corporeality that unifies and makes a body numerically and actually one. Additionally, while the form of corporeality makes the body actually one, it also makes the body potentially many. That is to say, the form of corporeality is the cause of a body’s being three-dimensional such that one can posit such divisions as right-side and left-side in it.

We are now led to the role of psychological processes in Avicenna’s account of a continuous body’s infinite divisibility. While it is true for Avicenna that continuous bodies can conceptually be divided without end, such a feature is not the result of any positive attribute within the body. This potentiality for division does not correspond with any positive features latent within the body. Instead the potentiality for infinite division refers to a privation in the matter of the body. The matter, extended and possessing quantity as a result of the form of corporeality, does not preclude or prevent one from positing imagined divisions within the body as small as one wants. Indeed, this psychological process of imaging or positing divisions in principle has no end. Thus, looking at, for example, a meter stick, one can posit a halfway point, then the halfway point of one side and then a further halfway point and so on as long as one likes; however, as soon as one stops the process of imagining halfway points, the imagined points (regardless of how many one has imagined) do not magically remain but altogether cease with the cessation of their being posited. The body remains as it always was, a unified whole, whose unity is only ever lost by actual physical division, not conceptual division.

With this conception of continuity in place, the Kalām argument against potential divisibility ad infinitum dissolves. Again that argument assumed two principles: (1) the impossibility of an actual infinity; and (2) an analysis of potentiality in terms of an agent’s power, namely, the view that some action φ is potential if and only if there is an agent who has the power actually to do φ. In point of fact, Avicenna rejects both principles (his conception of infinity is discussed at 2.4 ); for now he simply questions the theologians’ inference from something’s being potential to the possibility of its being realized all at once at some moment or other. The original Kalām argument assumed that a potential infinity of divisions existed in a continuous body. In that case, the argument continued, let God actualize that potential, and one is confronted with an actual infinity. Avicenna in contrast understands the potential infinite divisibility of bodies in terms of an ongoing process of positing successive divisions within the magnitude, a process that by definition has no end. Of course, there is a contradiction here in assuming that some agent, even God, can get to the end of some process that has no end, but such a contradiction does not tell against Avicenna’s theory of continuous bodies. In fact, Avicenna’s conception of potential infinite divisibility is compatible with (2), since there is no immediate contradiction in saying that God eternally and without ceasing posits ever-decreasing halfway points in some magnitude. Still even in this case, there never is an actual infinity of such halfway points, as the proponents of Kalām atomism maintain.

With the introduction of continuity and its corresponding notion of infinite divisibility one is also obliquely introduced to the notion of infinity ( lā nihāya ). Avicenna, following Aristotle’s account of the infinite ( apeiron ) at Physics , 3.6, defines it as “that which whatever you take from it—and any of the things equal to that thing you took from it—you [always] find something outside of it” (Avicenna, [Ph], 3.7 [2]). In natural philosophy, the immediate issue is whether an infinity exists either in quantities that posses some position or in numbers in an ordered series (Avicenna, [Ph], 3.7 [1]). The mutakallimūn, that is, the proponents of Kalām, were for the most part opposed to predicating the infinite of anything other than God. This opposition included both actual infinity and potential infinity, as we have seen. While it is notoriously difficult to give a precise account of the difference between the actual as opposed to the potential infinite, a rough characterization is this: In the case of an actually infinite magnitude, all the parts of that magnitude are somehow simultaneously and fully present, whereas in the case of the potentially infinite there is an going process or succession in which the units come to be, never wholly existing as actual at some given point or moment. While Avicenna happily accepts the reality of potential infinities, he denies that there are material instances of either actually infinite qualities, like infinitely large bodies, or numbers, like infinitely large sets of bodies, all of which exist simultaneously. [ 6 ]

Avicenna has a number of arguments attempting to show that an actual infinity in nature is impossible (for a presentation and assessment of some of these arguments see Zarepour 2020). These arguments can be divided into those that appeal to motion as part of the proof, and those that do not appeal to motion. Here I merely consider one of Avicenna’s non-motion proofs against an actual (spatial) infinity. The argument, which I present, is not the preferred proof in either The Cure or The Salvation , although he had toyed with it in The Cure (Avicenna, [Ph], 3.8 [5–7]). Still it is his preferred and indeed only argument against an actual infinity in his shorter and last philosophical encyclopedia, Pointers and Reminders (Avicenna, [PR], namaṭ 1, ch. 11, p. 183–90). [ 7 ] Moreover, the proof is a uniquely Avicennan one.

The argument asks one to posit some actually infinite ray, AB and then another actually infinite ray, AC, so as to form an acute angle ∠BAC. Next Avicenna asks one to consider the gap, BC, between the two rays. The farther from A that BC is, the larger BC becomes. Since the two rays are actually infinitely extended, BC should, in principle, also be actually infinite; however, BC always lies between AB and AC and of necessity terminates at them, so BC is finite. Thus, there is a contradiction: BC is both finite and infinite and, claims Avicenna, what produced the contradiction is the assumption that there is actually infinite space. Whether Avicenna’s new argument is successful became a matter of intense debate in post-classical Islamic natural philosophy, with such notables as Abū l-Barakāt al-Baghdādī (1080–1165) and Najm al-Dīn al-Kātibī al-Qazwīnī (ca. 1203–1277) finding it wanting, whereas Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (1201–1274) and Mullā Ṣadrā (1571–1636) considered it defensible (McGinnis 2018).

Avicenna’s arguments against an actual infinity in nature are in general all directed against the possibility of infinite spatial magnitude. Consequently, since space must be finite (i.e., limited), all bodies must be limited, and in being limited they have shape. This conclusion holds for the cosmos as a whole as well. As for the shape of the cosmos, while such a topic takes us slightly afield from a discussion of infinity, it does round out Avicenna’s abstract discussion of body. For a number of reasons, Avicenna thinks that the shape of the cosmos must be spherical. While in some ways Avicenna takes this claim to be a matter of empirical observation, he also argues that since the nature of the heavenly bodies is completely homogeneous and unvarying, there cannot be dissimilarities in a heavenly body such that a part of it would be angular and another part rectilinear or such that part of it has one sort of curve and another part a different sort (Avicenna, [DC], 3; also Avicenna, [Ph], 1.8 [2] provides the general argument, albeit there it is applied to showing the sphericity of the Earth). Inasmuch as the cosmos is spherical, it must have some center, which, at least from the point of physics, Avicenna identifies with the Earth. (Strictly speaking the Earth is a bit off center in accordance with the demands of the Ptolemaic astronomy, which Avicenna adopts.)

We thus now have a general picture of Avicenna’s conception of body in the abstract. Body is not composed of conceptually indivisible atoms but must be continuous and finite. In the next section I briefly consider body not in the abstract, but particular kinds of bodies, namely, the so-called elements.

2.5 Simple Bodies and the Elements

When Avicenna speaks of elements (sing. usṭuquss ) and (elemental) components (sing. ʿunṣur ), he means simple bodies, that is, bodies that are not composed of other sorts of bodies in the way that flesh, blood and bones, for example, are composed of more basics elements. Despite being simple, the elements are form-matter composites (Avicenna, [DC], 1). On account of their form and matter, elements have two powers: an active power following upon the element’s form and a passive power following upon its matter.

Avicenna: the Persian polymath who shaped modern science, medicine and philosophy

Doctoral Candidate, Comparative Literature, Religion and History of Philosophy, University of Sydney

Disclosure statement

Darius Sepehri does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Sydney provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Over a thousand years ago, Nuh ibn Mansur, the reigning prince of the medieval city of Bukhara, fell badly ill. The doctors, unable to do anything for him, were forced to send for a young man named Ibn Sina, who was already renowned, despite his very young age, for his vast knowledge. The ruler was healed.

Ibn Sina was an 11th century Persian philosopher, physician, pharmacologist, scientist and poet, who exerted a profound impact on philosophy and medicine in Europe and the Islamic world. He was known to the Latin West as Avicenna.

Avicenna’s Canon of medicine , first translated from Arabic into Latin during the 12th century, was the most important medical reference book in the West until the 17th century, introducing technical medical terminology used for centuries afterwards.

Avicenna’s Canon established a tradition of scientific experimentation in physiology without which modern medicine as we know it would be inconceivable.

For example, his use of scientific principles to test the safety and effectiveness of medications forms the basis of contemporary pharmacology and clinical trials.

Avicenna has been in the news recently due to his work on contagions. He produced an early version of the germ theory of disease in the Canon where he also advocated quarantine to control the transmission of contagious diseases.

Uniquely, Avicenna is the rare philosopher who became as influential on a foreign philosophical culture as his own. He is regarded by some as the greatest medieval thinker .

Read more: Explainer: what Western civilisation owes to Islamic cultures

Maverick and prodigious

He was born Abdallāh ibn Sīnā in 980AD in Bukhara, (present day Uzbekistan, then part of the Iranian Samanid empire ). Avicenna was prodigious from youth, claiming in his autobiography to have mastered all known philosophy by 18.

Avicenna’s output was extraordinarily prolific. One estimate of his body of work counts 132 texts. These cover logic, natural philosophy, cosmology, metaphysics, psychology, geology, and more. Some of these texts he wrote while on horseback, travelling from one city to another!

His work was a virtuosic kind of encylopedism , gathering the various traditions of Greek late antiquity, the early Islamic period and Iranian civilisation into one rational knowledge system covering all of reality.

Avicenna’s texts were forged out of the colossal Graeco-Arabic translation movement that took place in medieval Baghdad . They then played a key role in the Arabic to Latin translation movement that brought Aristotle’s philosophy back, in a highly enriched manner, into Western thought.

This was a chapter in the story of large-scale transmission of knowledge from the Islamic world to Europe .

From the 12th century on, Avicenna shaped the thought of major European medieval thinkers. Thomas Aquinas’s writings feature hundreds of quotations from Avicenna regarding issues such as God’s providence . Aquinas also sought to refute some of Avicenna’s positions such as that which argued the world was eternal .

Book of Healing

Avicenna’s Kitāb al-shifā , The Book of Healing , was as influential in Latin as his medical Canon.

Divided into sections covering logic, science, mathematics and metaphysics, it produced highly influential theses on the distinction between essence and existence and the famous Flying Man thought experiment , which aims to establish how the soul is innately aware of itself.

Read more: Four centuries of trying to prove God’s existence

A medical pioneer

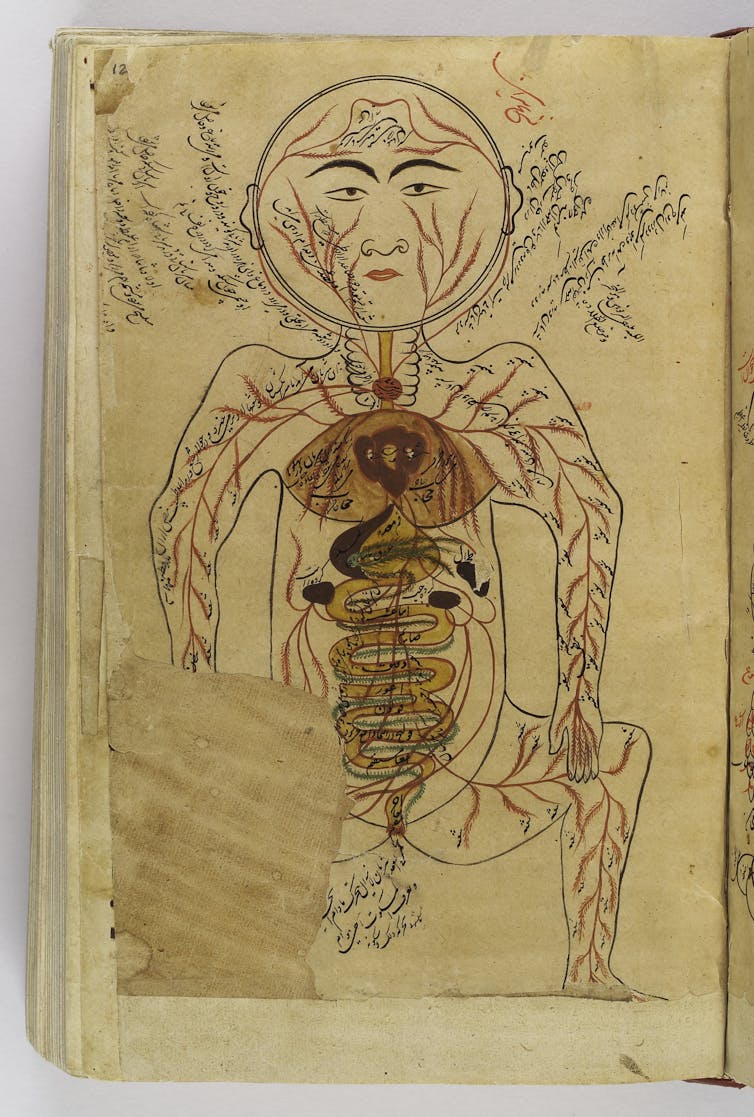

Avicenna’s Canon brilliantly synthesises Islamic medicine with that of Hippocrates (460 – 370 BC) and Galen (129 – 200 AD). There are also elements of ancient Persian, Mesopotamian and Indian medicine. This was supplemented by Avicenna’s extensive medical experiences.

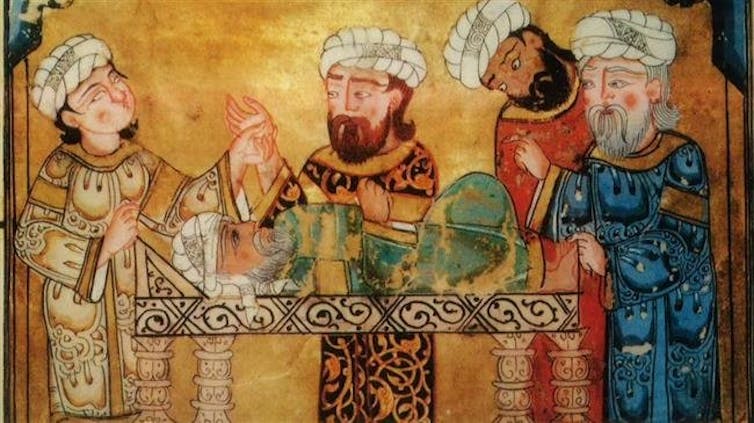

In the Canon, Avicenna introduced diagnoses and treatments for illnesses unknown to the Greeks, being the first doctor to describe meningitis. He made new arguments for the use of anaesthetics, analgesics, and anti-inflammatory substances .

Read more: Forget folk remedies, Medieval Europe spawned a golden age of medical theory

Looking forward to modern notions of disease prevention, Avicenna proposed adjustments in diet and physical exercise could heal or prevent illnesses.

Avicenna was also vital to the development of cardiology , pulsology , and our understanding of cardiovascular diseases .

Avicenna’s detailed descriptions of capillary flow and arterial and ventricular contractions in the cardiovascular system (the blood and circulatory system) assisted the Arab-Syrian polymath Ibn al Nafis (1213-1288), who became the first physician to describe the blood’s pulmonary circulation , the movement of blood from the heart to the lungs and back again to the heart.

This happened in 1242, centuries before scientist William Harvey arrived at the same conclusion in 17th century England.

Holistic medicine

Another innovative aspect of Avicenna’s Canon is its exploration of how our body’s well-being depends on the state of our mind, and the interaction between the heart’s health and our emotional life.

This connection has been seen in the last few months, with doctors describing increases in heart damage due to the psycho-emotional pressures of the pandemic.

Avicenna’s advocacy for an interrelated, organic and systems-based understanding of health gives his thought universal, ongoing relevance.

- Medical history

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Project Offier - Diversity & Inclusion

Senior Lecturer - Earth System Science

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

World History Edu

Ibn Sina (aka Avicenna): Life, Accomplishments and Major Works of the Renowned Persian Polymath

by World History Edu · November 29, 2022

It’s common knowledge that the advances in modern medicine are the result of numerous centuries of research, development and experimentation. However, unbeknownst to many people, a large number of those advancements took place in the Islamic world between the 9th and 14th centuries, a period historians like to refer to as the Islamic Golden age. Inspired by the works of ancient Greeks and Romans, Islamic Golden age scholars were tolerant and open to new knowledge and technology from different parts of the world, including from non-Muslims. One of such distinguished scholars was the Persian polymath ibn Sīnā, who is known in the West as Avicenna. ibn Sīnā’s medical texts had profound influence on the study of medicine throughout Europe for many centuries. For example, until the late 17th century, his work “The Canon of Medicine” remained the standard textbook in many medical schools across Europe and beyond.

What else was ibn Sīnā best known for? And how did his works and contributions to medicine come to epitomize the Islamic Golden Age?

Below, we look at the life and major achievements of Ibn Sina, the Persian polymath who is often hailed as the “Father of Early Modern Medicine”.

Abu Ali al-Husayn Ibn Abd Allan Ibn Sina, popularly known in Western societies as Avicenna, was the son of Abdullah and Setareh. He was born in c. 980 in Transoxiana, a place in central Asia. Soon after his birth, his family relocated to Bukhara, where he received his early education in Hanafi jurisprudence from Isma’il Zahid and began his studies in medicine under the tutelage of a variety of experts.

He became a well-known doctor by the time he was 16 years old and spent a lot of time learning about physics, natural sciences, and philosophy in addition to his medical studies. He rose to notoriety after successfully curing a very rare illness that had plagued Nuh ibn Mansur, the Sultan of Bukhara of the Samanid Court, Nuh ibn Mansur.

In 997, after Ibn Sina had healed Nun ibn Mansur of his disease, Mansur employed him as his personal physician. In addition to that, the sultan granted him access to his library and its collection of priceless manuscripts so that he could continue his studies. This education and access to the medical library of the Samanid court aided him in his pursuit of philosophical understanding. As one of the finest of its sort in the medieval world, the sultan’s royal library was a source of great prestige for his country, and Ibn Sina took full advantage of the opportunity to advance his knowledge in a host of disciplines.

What was the polymath best known for?

Avicenna also wrote numerous psychological works about the connection between the mind, the body, and the senses.

Ibn Sina’s book “Al-Qanun fi al-Tibb” ( The Canon of Medicine ) is widely regarded as a landmark in the field of medicine because of the way it skillfully weaves together old medical wisdom with modern discoveries made by Islamic scientists of the Golden Age.

At some point in the 12th century, the book was translated into Latin, and from that point on, it was employed as a go-to medicine textbook at universities across Europe until the middle of the 17th century.

Ibn Sina not only outlined the anatomy of various body components, including the eye and the heart, but he also listed over 550 potential treatments for common diseases. The physician also discusses the impact that plants and roots have on the human body, demonstrating his expertise as a botanist.

One of his most important contributions to medicine was his research on the usefulness of quarantines in preventing the transmission of disease. He argued that a quarantine of at least 40 days was necessary to prevent the spread of infection. This became one of his most notable contributions to medicine.

The Book of Healing

“The Book of Healing”, one of his most influential writings outside of medicine, is divided into four parts and covers a wide range of topics, including mathematics, physics, biological sciences, and psychology. After an extensive 50 page a day write up, Sina completed “The Book of Healing”; however, the book only became available in Europe fifty years later under a new title known as “Sufficientia”.

The book is regarded as one of the most notable works of physiology and taking a closer would reveal the polymath’s knowledge displayed across numerous fields.

Did Avicenna believe in God?

The establishment of his own version of Aristotelian logic and the use of reason to prove the presence of God were Ibn Sina’s most significant contributions to the field of philosophy.

The Persian polymath, while challenging his Greek predecessor Aristotle , held the view that humans possessed three souls: the vegetative, the animal, and the intellectual. He believed that humans’ reasoning ability was the link between them and God, whereas the first two tied them to the ground.

With this philsophy, Ibn Sina authored a book titled “Burhan al-Siddiqin” ( Proof of the Truthful ) in which he argued that God must exist because there is no such thing as a nonexistent being. He went on to say that everything other than this is dependent on the existence of another entity. A person’s own existence, for instance, is dependent on the presence of their parents, who in turn depend on the existence of their family members, and so forth.

Ibn Sina reasoned that even when everything in the universe is added up, it is still contingent, since everything needs a non-contingent cause outside of itself, which he believed to be God. Ibn Rushd later argued that this kind of thinking was flawed because it relied on unprovable metaphysical principles rather than observable natural rules. Therefore, Ibn Sina kept his belief in God.

READ MORE: Top 10 Philosophers from Ancient Greece

The link between the human senses and soul

Ibn Sina dedicated most of his life to learning the ins and outs of the human senses and proving that they were more complex than previously thought. He suggested that we possess inner senses that work in tandem with the five traditionally recognized senses (i.e. taste, smell, hearing, sight, and touch).

An avid intuitive scholar, he considered common sense to be an internal sense and even credited it with performing some of the soul’s tasks. Therefore, in his view, the process of coming up with an opinion and deciding on an action is an act of the soul.

He believed that aside from using common sense, individuals also relied on their retentive imagination to recall the facts they had learned. This perceptual faculty saves numerous information in the mind, allowing you to recall this information and identify them.

Finally, Ibn Sina explained that understanding is the ability to use all the information to the best of our internal senses’ capacities, while memory is responsible for preserving all the knowledge created by the other senses.

Other discoveries of the polymath

In his scientific writings, Avicenna argued that light traveled at a constant velocity. He also described the path of sound in the air and proposed a theory of motion. Here are some other notable discoveries and works made by Avicenna:

- The polymath, during his study of an early kind of psychiatry, discussed the physical manifestations of mental health problems like depression and anxiety.

- The study of earthquakes and cloud formation were two examples of the natural phenomena studied by the Persian polymath. He explained that surface-level earthquakes are caused by plate movements and other subsurface processes.

- By comparing the apparent size of Venus to the sun’s disc, Ibn Sina deduced that Venus was actually further from the sun than the Earth. It’s been said that he may have discovered that the SN 1006 supernova, visible for three months around the turn of the first millennium CE, briefly outshone Venus and was visible even in broad daylight.