Help | Advanced Search

Computer Science > Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition

Title: simple online and realtime tracking with a deep association metric.

Abstract: Simple Online and Realtime Tracking (SORT) is a pragmatic approach to multiple object tracking with a focus on simple, effective algorithms. In this paper, we integrate appearance information to improve the performance of SORT. Due to this extension we are able to track objects through longer periods of occlusions, effectively reducing the number of identity switches. In spirit of the original framework we place much of the computational complexity into an offline pre-training stage where we learn a deep association metric on a large-scale person re-identification dataset. During online application, we establish measurement-to-track associations using nearest neighbor queries in visual appearance space. Experimental evaluation shows that our extensions reduce the number of identity switches by 45%, achieving overall competitive performance at high frame rates.

Submission history

Access paper:.

- Other Formats

References & Citations

- Google Scholar

- Semantic Scholar

1 blog link

Dblp - cs bibliography, bibtex formatted citation.

Bibliographic and Citation Tools

Code, data and media associated with this article, recommenders and search tools.

- Institution

arXivLabs: experimental projects with community collaborators

arXivLabs is a framework that allows collaborators to develop and share new arXiv features directly on our website.

Both individuals and organizations that work with arXivLabs have embraced and accepted our values of openness, community, excellence, and user data privacy. arXiv is committed to these values and only works with partners that adhere to them.

Have an idea for a project that will add value for arXiv's community? Learn more about arXivLabs .

MARK H. EBELL, M.D., M.S., JAY SIWEK, M.D., BARRY D. WEISS, M.D., STEVEN H. WOOLF, M.D., M.P.H., JEFFREY SUSMAN, M.D., BERNARD EWIGMAN, M.D., M.P.H., AND MARJORIE BOWMAN, M.D., M.P.A.

Am Fam Physician. 2004;69(3):548-556

See editorial on page 483.

A large number of taxonomies are used to rate the quality of an individual study and the strength of a recommendation based on a body of evidence. We have developed a new grading scale that will be used by several family medicine and primary care journals (required or optional), with the goal of allowing readers to learn one taxonomy that will apply to many sources of evidence. Our scale is called the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy. It addresses the quality, quantity, and consistency of evidence and allows authors to rate individual studies or bodies of evidence. The taxonomy is built around the information mastery framework, which emphasizes the use of patient-oriented outcomes that measure changes in morbidity or mortality. An A-level recommendation is based on consistent and good-quality patient-oriented evidence; a B-level recommendation is based on inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence; and a C-level recommendation is based on consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, or case series for studies of diagnosis, treatment, prevention, or screening. Levels of evidence from 1 to 3 for individual studies also are defined. We hope that consistent use of this taxonomy will improve the ability of authors and readers to communicate about the translation of research into practice.

Review articles (or overviews) are highly valued by physicians as a way to keep up-to-date with the medical literature. Sometimes, though, these articles are based more on the authors' personal experience, anecdotes, or incomplete surveys of the literature than on a comprehensive collection of the best available evidence. As a result, there is an ongoing effort in the medical publishing field to improve the quality of review articles through the use of more explicit grading of the strength of evidence on which recommendations are based. 1 – 4

Several journals, including American Family Physician and The Journal of Family Practice , have adopted evidence-grading scales that are used in some of the articles published in those journals. Other organizations and publications also have developed evidence-grading scales. The diversity of these scales can be confusing for readers. More than 100 grading scales are in use by various medical publications. 5 A level B recommendation in one journal may not mean the same thing as a level B recommendation in another. Even within journals, different evidence-grading scales sometimes are used in separate articles within the same issue. Journal readers do not have the time, energy, or interest to interpret multiple grading scales, and more complex scales are difficult to integrate into daily practice.

Therefore, the editors of the U.S. family medicine and primary care journals (i.e., American Family Physician, Family Medicine, The Journal of Family Practice, Journal of the American Board of Family Practice , and BMJ-USA ) and the Family Practice Inquiries Network (FPIN) came together to develop a unified taxonomy for the strength of recommendations based on a body of evidence. The new taxonomy should: (1) be uniform in most family medicine journals and electronic databases; (2) allow authors to evaluate the strength of recommendation of a body of evidence; (3) allow authors to rate the level of evidence for an individual study; (4) be comprehensive and allow authors to evaluate studies of screening, diagnosis, therapy, prevention, and prognosis; (5) be easy to use and not too time-consuming for authors, reviewers, and editors who may be content experts but not experts in critical appraisal or clinical epidemiology; and (6) be straightforward enough that primary care physicians can readily integrate the recommendations into daily practice.

Definitions

A number of relevant terms must be defined for clarification.

Disease-Oriented Outcomes

These outcomes include intermediate, histopathologic, physiologic, or surrogate results (e.g., blood sugar, blood pressure, flow rate, coronary plaque thickness) that may or may not reflect improvement in patient outcomes.

Patient-Oriented Outcomes

These are outcomes that matter to patients and help them live longer or better lives, including reduced morbidity, reduced mortality, symptom improvement, improved quality of life, or lower cost.

Level of Evidence

The validity of an individual study is based on an assessment of its study design. According to some methodologies, 6 levels of evidence can refer not only to individual studies but also to the quality of evidence from multiple studies about a specific question or the quality of evidence supporting a clinical intervention. For purposes of maintaining simplicity and consistency in this proposal, we use the term “level of evidence” to refer to individual studies.

Strength of Recommendation

The strength (or grade) of a recommendation for clinical practice is based on a body of evidence (typically more than one study). This approach takes into account the level of evidence of individual studies; the type of outcomes measured by these studies (patient-oriented or disease-oriented); the number, consistency, and coherence of the evidence as a whole; and the relationship between benefits, harms, and costs.

Practice Guideline (Evidence-Based)

These guidelines are recommendations for practice that involve a comprehensive search of the literature, an evaluation of the quality of individual studies, and recommendations that are graded to reflect the quality of the supporting evidence. All search, critical appraisal, and grading methods should be described explicitly and be replicable by similarly skilled authors.

Practice Guideline (Consensus)

Consensus guidelines are recommendations for practice based on expert opinions that typically do not include a systematic search, an assessment of the quality of individual studies, or a system to label the strength of recommendations explicitly.

Research Evidence

This evidence is presented in publications of original research, involving collection of original data or the systematic review of other original research publications. It does not include editorials, opinion pieces, or review articles (other than systematic reviews or meta-analyses).

Review Article

A nonsystematic overview of a topic is a review article. In most cases, it is not based on an exhaustive, structured review of the literature and does not evaluate the quality of included studies systematically.

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

A systematic review is a critical assessment of existing evidence that addresses a focused clinical question, includes a comprehensive literature search, appraises the quality of studies, and reports results in a systematic manner. If the studies report comparable quantitative data and have a low degree of variation in their findings, a meta-analysis can be performed to derive a summary estimate of effect.

Existing Strength-of-Evidence Scales

In March 2002, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) published a report that summarized the state-of-the-art in methods of rating the strength of evidence. 5 The report identified a large number of systems for rating the quality of individual studies: 20 for systematic reviews, 49 for randomized controlled trials, 19 for observational studies, and 18 for diagnostic test studies. It also identified 40 scales that graded the strength of a body of evidence consisting of one or more studies.

The authors of the AHRQ report proposed that any system for grading the strength of evidence should consider three key elements: quality, quantity, and consistency. Quality is the extent to which the identified studies minimize the opportunity for bias and is synonymous with the concept of validity. Quantity is the number of studies and subjects included in those studies. Consistency is the extent to which findings are similar between different studies on the same topic. Only seven of the 40 systems identified and addressed all three of these key elements. 6 – 11

Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT)

The authors of this article represent the major family medicine journals in the United States and a large family medicine academic consortium. Our process began with a series of e-mail exchanges, was developed during a meeting of the editors, and continued through another series of e-mail exchanges.

We decided that our taxonomy for rating the strength of a recommendation should address the three key elements identified in the AHRQ report: quality, quantity, and consistency of evidence. We also were committed to creating a grading scale that could be applied by authors with varying degrees of expertise in evidence-based medicine and clinical epidemiology, and interpreted by physicians with little or no formal training in these areas. We believed that the taxonomy should address the issue of patient-oriented evidence versus disease-oriented evidence explicitly and be consistent with the information mastery framework proposed by Slawson and Shaughnessy. 2

After considering these criteria and reviewing the existing taxonomies for grading the strength of a recommendation, we decided that a new taxonomy was needed to reflect the needs of our specialty. Existing grading scales were focused on a particular kind of study (e.g., prevention or treatment), were too complex, or did not take into account the type of outcome.

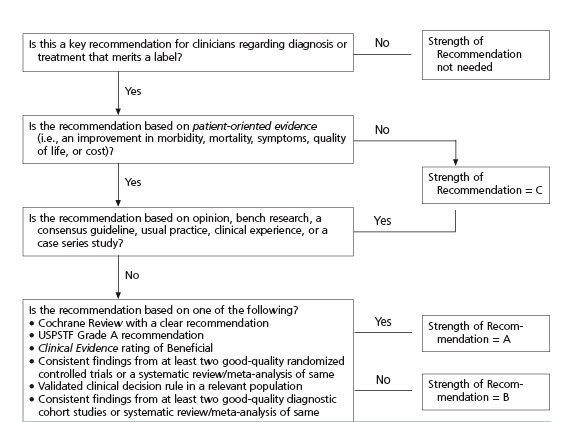

Our proposed taxonomy is called the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT). It is shown in Figure 1 . The taxonomy includes ratings of A, B, or C for the strength of recommendation for a body of evidence. The table in the center of Figure 1 explains whether a body of evidence represents good-quality or limited-quality evidence, and whether evidence is consistent or inconsistent. The quality of individual studies is rated 1, 2, or 3; numbers are used to distinguish ratings of individual studies from the letters A, B, and C used to evaluate the strength of a recommendation based on a body of evidence. Figure 2 provides information about how to determine the strength of recommendation for management recommendations, and Figure 3 explains how to determine the level of evidence for an individual study. These two algorithms should be helpful to authors preparing papers for submission to family medicine journals. The algorithms are to be considered general guidelines, and special circumstances may dictate assignment of a different strength of recommendation (e.g., a single, large, well-designed study in a diverse population may warrant an A-level recommendation).

Recommendations based only on improvements in surrogate or disease-oriented outcomes are always categorized as level C, because improvements in disease-oriented outcomes are not always associated with improvements in patient-oriented outcomes, as exemplified by several well-known findings from the medical literature. For example, doxazosin lowers blood pressure in black patients—a seemingly beneficial outcome—but it also increases mortality rates. 12 Similarly, encainide and flecainide reduce the incidence of arrhythmias after acute myocardial infarction, but they also increase mortality rates. 13 Finasteride improves urinary flow rates, but it does not significantly improve urinary tract symptoms in patients with benign prostatic hypertrophy, 14 while arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee improves the appearance of cartilage but does not reduce pain or improve joint function. 15 Additional examples of clinical situations where disease-oriented evidence conflicts with patient-oriented evidence are shown in Table 1 . 12 – 24 Examples of how to apply the taxonomy are given in Table 2 .

We believe there are several advantages to our proposed taxonomy. It is straightforward and comprehensive, is easily applied by authors and physicians, and explicitly addresses the issue of patient-oriented versus disease-oriented evidence. The latter attribute distinguishes SORT from most other evidence-grading scales. These strengths also create some limitations. Some clinicians may be concerned that the taxonomy is not as detailed in its assessment of study designs as others, such as that of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM). 25 However, the primary difference between the two taxonomies is that the CEBM version distinguishes between good and poor observational studies while the SORT version does not. We concluded that the advantages of a system that provides the physician with a clear recommendation that is strong (A), moderate (B), or weak (C) in its support of a particular intervention outweighs the theoretic benefit of distinguishing between lower quality and higher quality observational studies, particularly because there is no objective evidence that the latter distinction carries important differences in clinical recommendations.

Any publication applying SORT (or any other evidence-based taxonomy) should describe carefully the search process that preceded the assignment of a SORT rating. For example, authors could perform a comprehensive search of MEDLINE and the gray literature, a comprehensive search of MEDLINE alone, or a more focused search of MEDLINE plus secondary evidence-based sources of information.

Walkovers: Creating Linkages with SORT

Some organizations, such as the CEBM, 25 the Cochrane Collaboration, 7 and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 6 have developed their own grading scales for the strength of recommendation based on a body of evidence and are unlikely to abandon them. Other organizations, such as the FPIN, 26 publish their work in a variety of settings and must be able to move between taxonomies. We have developed a set of optional walkovers that suggest how authors, editors, and readers might move from one taxonomy to another. Walkovers for the CEBM and BMJ Clinical Evidence taxonomies are shown in Table 3 .

Many authors and experts in evidence-based medicine use the “Level of Evidence” taxonomy from the CEBM to rate the quality of individual studies. 25 A walkover from the five-level CEBM scale to the simpler three-level SORT scale for individual studies is shown in Table 4 .

Final Comment

The SORT is a comprehensive taxonomy for evaluating the strength of a recommendation based on a body of evidence and the quality of an individual study. If applied consistently by authors and editors in the family medicine literature, it has the potential to make it easier for physicians to apply the results of research in their practice through the information mastery approach and to incorporate evidence-based medicine into their patient care.

Like any such grading scale, it is a work in progress. As we learn more about biases in study design, and as the authors and readers who use the taxonomy become more sophisticated about principles of information mastery, evidence-based medicine, and critical appraisal, it is likely to evolve. We remain open to suggestions from the primary care community for refining and improving SORT.

Evidence-based medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA. 1992;268:2420-5.

Slawson DC, Shaughnessy AF, Bennett JH. Becoming a medical information master: feeling good about not knowing everything. J Fam Pract. 1994;38:505-13.

Shaughnessy AF, Slawson DC, Bennett JH. Becoming an information master: a guidebook to the medical information jungle. J Fam Pract. 1994;39:489-99.

Siwek J, Gourlay ML, Slawson DC, Shaughnessy AF. How to write an evidence-based clinical review article. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:251-8.

Systems to rate the strength of scientific evidence. Summary, evidence report/technology assessment: number 47. AHRQ publication no. 02-E015, March 2002. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, Md. Accessed November 13, 2003, at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/epc-sums/strengthsum.htm.

Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, Lohr KN, Mulrow CD, Teutsch SM, et al. Current methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: a review of the process. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(3 suppl):21-35.

Clarke M, Oxman AD. Cochrane reviewers' handbook 4.2.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2003. Accessed November 13, 2003, at: http://www.cochrane.org/resources/handbook/handbook.pdf.

Gyorkos TW, Tannenbaum TN, Abrahamowicz M, Oxman AD, Scott EA, Millson ME, et al. An approach to the development of practice guidelines for community health interventions. Can J Public Health. 1994;85(suppl 1):S8-13.

Briss PA, Zaza S, Pappaioanou M, Fielding J, Wright-De Aguero L, Truman BI, et al. Developing an evidence-based guide to community preventive services—methods. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1 suppl):35-43.

Greer N, Mosser G, Logan G, Halaas GW. A practical approach to evidence grading. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2000;26:700-12.

Guyatt GH, Haynes RB, Jaeschke RZ, Cook DJ, Green L, Naylor CD, et al. Users' guides to the medical literature: XXV. Evidence-based medicine: principles for applying the users' guides to patient care. JAMA. 2000;284:1290-6.

Major cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients randomized to doxazosin vs chlorthalidone: the antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT) [published correction in JAMA 2002;288:2976]. JAMA. 2000;283:1967-75.

Echt DS, Liebson PR, Mitchell LB, Peters RW, Obias-Manno D, Barker AH, et al. Mortality and morbidity in patients receiving encainide, flecainide, or placebo. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:781-8.

Lepor H, Williford WO, Barry MJ, Brawer MK, Dixon CM, Gormley G, et al. The efficacy of terazosin, finasteride, or both in benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:533-9.

Moseley JB, O'Malley K, Petersen NJ, Menke TJ, Brody BA, Kuykendall DH, et al. A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:81-8.

Dwyer T, Ponsonby AL. Sudden infant death syndrome: after the “back to sleep” campaign. BMJ. 1996;313:180-1.

Yusuf S, Dagenais G, Pogue J, Bosch J, Sleight P. Vitamin E supplementation and cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:154-60.

Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, Delaney B, Innes M, Forman D. Pharmacological interventions for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003(1):CD001960.

Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321-33.

Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet. 1998;352:837-53.

Meunier PJ, Sebert JL, Reginster JY, Briancon D, Appelboom T, Netter P, et al. Fluoride salts are no better at preventing new vertebral fractures than calcium-vitamin D in post-menopausal osteoporosis: the FAVOStudy. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:4-12.

MacMahon S, Collins R, Peto R, Koster RW, Yusuf S. Effects of prophylactic lidocaine in suspected acute myocardial infarction. An overview of results from the randomized, controlled trials. JAMA. 1988;260:1910-6.

Grumbach K. How effective is drug treatment of hypercholesterolemia? A guided tour of the major clinical trials for the primary care physician. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1991;4:437-45.

Heidenreich PA, Lee TT, Massie BM. Effect of beta-blockade on mortality in patients with heart failure: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:27-34.

Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Levels of evidence and grades of recommendation. Accessed November 13, 2003, at: http://www.cebm.net/levels_of_evidence.asp.

Family Practice Inquiries Network (FPIN). Accessed November 13, 2003, at: http://www.fpin.org .

Continue Reading

More in afp, more in pubmed.

Copyright © 2004 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- About This Blog

- Official PLOS Blog

- EveryONE Blog

- Speaking of Medicine

- PLOS Biologue

- Absolutely Maybe

- DNA Science

- PLOS ECR Community

- All Models Are Wrong

- About PLOS Blogs

Organizing Papers and References without Losing your Mind

In January, Ulrike Träger wrote a great PLOS ECR post describing how to stay on top of reading during graduate school. If you haven’t read it yet, go take a look, as it’s relevant for people at all career stages. As a follow up, here are a few tips on how to keep track of the papers you want to read without losing your mind.

Choose a reference manager. Sure, you can get by creating a poster or two without a reference manager, but it’s incredibly risky to cite references by hand for manuscripts and grant proposals. Choosing and using a reference manager is also a great way to track papers as you collect them, particularly because reference managers often have powerful search functions. There are many to choose from. Some are free, like Zotero and some versions of Mendeley . Others, like Papers and EndNote , are not, though some paid programs may be free through your institution. Spend some time researching which manager fits your needs, but don’t get bogged down, you can always switch later. Personally, I have transferred references from RefWorks to Zotero to Mendeley to EndNote over the past several years without much trouble.

Choose a place to keep unread papers. Whether it’s a physical folder on your desk or a virtual folder on your desktop, it’s important to have a designated place for unread papers. This folder is more than just a storage space, it should also be a reminder for you to review unread papers. It’s tempting to download papers and forget about them, falling prey to PDF alibi syndrome , wherein you fool yourself into thinking that by downloading a paper you’ve somehow read it. So, set aside some time every few weeks (on your calendar if you need to) to review papers. You won’t necessarily read each paper in detail, but you should complete a quick skim and take a few notes. Try to resist the urge to leave notes like “finish reading later.” However, if needed, consider using notes like “need to read again before citing” for papers that were skimmed particularly quickly.

Choose how to keep track of your notes. It’s a great idea to create a summary of each paper as you read it, but where do you keep this information? Some people write separate documents for each paper (e.g., using the Rhetorical Précis Format ), others write nothing at all, but tag papers (virtually or physically) with key words. The exact components of your system matter less than having a system. Right now, I keep a running document with a few sentences about each paper I read. I also note whether I read it on paper or as a PDF so that I can find notes taken on the paper itself later. If I’m doing a deep read on a specific topic, I might also start another document that has in-depth summaries. I usually keep notes in Word documents, but it’s also possible to store these notes in many reference managers.

Choose how to file read papers. Again, having a system probably matters more than which system you choose. Given the interdisciplinary nature of science, it can be complex to file by topic. Therefore, I find it easiest to file papers by last name of the first author and the publication year. It’s also useful to include a few words in the file name that summarize its content. This will help you differentiate between articles written by authors with similar last names. So, for example, using this method, you might label this blog post as Breland_2017_tracking refs. I keep articles I’ve read in a folder labeled “Articles” that includes a folder for each letter of the alphabet. Therefore, I’d file this blog post in the “B” folder for Breland.

TL;DR. The goal of creating a system to organize papers and references is to be able to easily access them later. If you follow the steps above, it’s relatively easy to keep track of and use what you’ve read – if you want to find a paper, you can search for a key word in your reference manager and/or in your running document of article summaries and then find a copy of the paper in the appropriate alphabetized folder. That said, there is no right way to organize references and I’m curious about how others manage their files. Chime in through the comments and we’ll update the post with any interesting answers!

Pat Thomson (2015) PDF alibi syndrome , Patter blog. Accessed 2/27/17.

Ulrike Träger (2017) Ten tips to stay on top of your reading during grad school , PLoS ECR Community Blog.

Sample Rhetorical Précis: http://oregonstate.edu/instruct/phl201/modules/rhetorical-precis/sample/peirce_sample_precis_click.html

Featured image available through CC0 license.

[…] Organizing Papers And References Without Losing Your Mind – Jessica Breland […]

You have a great organizing skills! I appreciate your tips!

Fantastic tips! Thank you for sharing.

Great tips! It helps me a lot while I’m doing my final diploma project. Thank you.

This is great, very helpful. Nicely written and clearly organized [like your ref lib 😉 ] C

im at the start of my phd and already feeling that i have a lot of literature. i am taking your notes onboard and going to spend some time to organise my files asap. thanks

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name and email for the next time I comment.

How to Organize Research Papers: A Cheat Sheet for Graduate Students

- August 8, 2022

- PRODUCTIVITY

It is crucial to organize research papers so that the literature survey process goes smoothly once the data has been gathered and analyzed. This is where a research organizer is useful.

It may be helpful to plan the structure of your writing before you start writing: organizing your ideas before you begin to write will help you decide what to write and how to write it.

It can be challenging to keep your research organized when writing an essay. The truth is, there’s no one “ best ” way to get organized, and there’s no one answer. Whatever system you choose, make sure it works for your learning style and writing habits.

As a graduate student, learning how to organize research papers is therefore essential.

This blog post will cover the basics of organizing research papers and the tools I use to organize my research.

Before you start

The importance of organizing research papers.

No matter how good your paper management system is, even if you keep all your literature in places that are easy to find, you won’t be able to “create” anything unless you haven’t thought about organizing what you get from them.

The goal of the research is to publish your own work to society for the benefit of everyone in the field and, ultimately, humanity.

In your final year of your PhD, when you see all the papers you’ve stored over the years, imagine the frustration you might experience if you hadn’t gathered the information from those papers in a way that allows you to “create” something with i.

This is why organizing research papers is important when starting your research.

Research with your final product in mind

It is very important to have a clear idea of what your research’s outcome will be to collect the information you really need.

If you don’t yet have all your information, consider what “subheadings” or chunks you could write about.

Write a concept map if you need help identifying your topic chunks. As an introduction to concept mapping, it involves writing down a term or idea and then brainstorming other ideas within it.

To gather information like this, you can use a mind map.

When you find useful information.

Come up with a proper file management system.

Sort your literature with a file management system. There’s no need to come up with a very narrow filing system at this point. Try sorting your research into broader areas of your field. When you’re more familiar with your own research, you’ll be able to narrow down your filing system.

Start with these methods:

Don’t waste your time on stuff that’s interesting but not useful :

In your own research, what’s the most important part of a particular paper? You won’t have to pay attention to other sections of that paper if you find that section first.

What is the argument behind your research? Make notes on that information, and then throw everything else away.

Create multiple folders :

Create a file containing related topics if you’re using a computer. Bind the related articles together if you like to print out papers. In other words, keep related things together!

Color code your research papers:

To organize notes and articles, assign different colors to each sub-topic and use highlighters, tabs, or font colors.

Organize your literature chronologically:

Even in a short period of time, you might have missed overarching themes or arguments if you hadn’t read them previously. It’s best to organize your research papers chronologically.

If you want to do all this at once, I suggest using a reference manager like Zotero or Mendeley (more on reference managers later).

File renaming

Make sure you rename your files on your computer according to your own renaming strategy. Taking this step will save you time and confusion as your research progresses.

My usual way of naming a pdf is to use the first author’s last name, followed by the first ten letters of the title and then the year of publication. As an example, For the paper “ Temperature-Dependent Infrared Refractive Index of Polymers from a Calibrated Attenuated Total Reflection Infrared Measurement ” by Azam et al., I renamed the file as “ Azam_Temperature-Dependent_2022.pdf “.

One thing to notice is that I don’t do this manually for all the papers I download. That wouldn’t be as productive, and I’d probably give up after some time renaming every single file. In my reference manager of choice (Zotero), I use a plugin called Zotfile to do this automatically. Zotfile automatically renames files and puts them in the folder I specify every time I add a new paper.

Organizing your research articles by the last names of the lead authors will simplify your citation and referencing process since you have to cite the names of the researchers everywhere. The articles will also be easier to find because they’ll be lined up alphabetically by any researcher’s name you can remember.

Use keywords wisely

Keywords are the most important part of sorting. It’s easy to forget to move a paper to a specific file sometimes because you’re overwhelmed. But you can tag a paper in seconds.

When organizing research papers, don’t forget to develop a better keyword system, especially if you use a reference manager.

My reference manager, for instance, allows me to view all the keywords I have assigned in the main window, making life much easier.

Create annotations

When reading literature, it is very important to create your own annotations, as discussed in the blog post series, “ Bulletproof literature management system “.

This is the fourth post of the four-part blog series: The Bulletproof Literature Management System . Follow the links below to read the other posts in the series:

- How to How to find Research Papers

- How to Manage Research Papers

- How to Read Research Papers

- How to Organize Research Papers (You are here)

The best thing to do is to summarize each section of the article/book you are reading that interests you. Don’t forget to include the key parts/arguments/quotes you liked.

Write your own notes

If you decide to read the whole paper, make sure you write your own summary. The reason is that 95% of the things you read will be forgotten after a certain period of time. When that happens, you may have to read the paper all over again if you do not take notes and write your own summary.

By writing your own summary, you will likely memorize the basic idea of the research paper. Additionally, you can link to other similar papers. In this way, you can benefit from the knowledge you gain from reading research papers.

After reading a paper, make sure to ask these questions:

- Why is this source helpful for your essay?

- How does it support your thesis?

Keep all the relevant information in one place so that you can refer to it when writing your own thesis.

Use an app like Obsidian to link your thinking if you keep all your files on a computer, making things much easier.

When you are ready to write

Write out of order .

Once you have all the necessary information, you can use your filing system, PDF renaming strategy, and keywords to draw the annotations and notes you need.

Now that you’re all set to write, don’t worry about writing the perfect paper or thesis right away.

Your introduction doesn’t have to come first.

If necessary, you can change your introduction at the end – sometimes, your essay takes a different direction. Nothing to worry about!

Write down ideas as they come to you

As you complete your research, many full-sentence paragraphs will come to your mind. Do not forget to write these down – even in your notes or annotations. Keep a notebook or your phone handy to jot down ideas as you get them. You can then find the information and revise it again to develop a better version if you’re working on the same project for a few days/weeks.

My toolbox to organize research papers

Stick with the free stuff.

Trying to be a productive grease monkey, I’ve tried many apps over the years. Here’s what I learned.

- The simplest solution is always the best solution (the Occam razor principle always wins!).

- The free solution is always the best (because they have the best communities to help you out and are more customizable).

As someone who used to believe that if something is free, you’re the product, I’ve learned that statement isn’t always true.

Ironically, open-source software tends to get better support than proprietary stuff. It’s better to have millions of enthusiasts working for free than ten paid support staff.

There are a lot of reviews out there, and EndNote usually comes out at the bottom. I used EndNote for five years – it worked fine, but other software improved faster. Now I use Zotero, which I like for its web integration.

Obsidian, my note-taking app of choice, is also free software. Furthermore, you own your files; also, you’ve got a thriving community.

There are a lot of similarities between the software as they adopt each other’s features, and it’s just a matter of preference.

In any researcher’s toolbox, a reference manager is an essential tool.

A reference manager has two important features: the ability to get citation data into the app and the ability to use the citation data in your writing tool.

It should also work on Windows just as well as macOS or Linux, be free, and allow you to manage PDFs of papers or scanned book chapters.

Zotero , in my opinion, gives you all of this and more.

Zotero is one of the best free reference managers for collecting citation data. It includes a browser plugin that lets you save citation information on Google Scholar, journal pages, YouTube, Amazon, and many other websites, including news articles. It automatically downloads a PDF of the associated source when available for news articles, which is very convenient.

One of the things I really like about Zotero is that it has so many third-party plugins that we have almost complete control over how we use it.

With Zotero 6, you can also read and annotate PDFs, which is perfect for your needs.

My Research paper organizing workflow in Zotero :

- Get References and PDF papers into Zotero : I use Zotero’s web plugin to import PDFs directly

- Filing and sorting : I save files from the web plugin into the file system I already have created in Zotero and assign tags as I do so.

- File renaming : When I save the file, the Zotero plugin (Zotfile) automatically renames it and stores the pdf where I specified.

- Extracting Annotations and taking notes : I use Zotero in the build pdf reader to take notes and annotate, and then I extract them and link them in Obsidian (next section).

You need to keep your notes organized and accessible once you’ve established a strong reading habit. For this purpose, I use Obsidian . I use Obsidian to manage everything related to my graduate studies, including notes, projects, and tasks.

Using a plugin called mdnotes , Obsidian can also sync up with my reference manager of choice, Zotero. It automatically adds new papers to my Obsidian database whenever I add them to Zotero.

Obsidian may have a steep learning curve for those unfamiliar with bi-directional linking , but using similar software will make things much easier. Thus, you may be better off investing your time in devising a note-taking system that works for you.

You can also use a spreadsheet! Make a table with all the papers you read, whatever tool you choose. Include the paper’s status (e.g., whether you’ve read it) and any relevant projects. This is what mine looks like.

I keep all my notes on an associated page for each paper. In a spreadsheet, you can write your notes directly in the row or link to a Google document for each row. Zotero, for example, allows you to attach notes directly to reference files.

While it might seem like a lot of work, keeping a database of papers you’ve read helps with literature reviews, funding applications, and more. I can filter by keywords or relevant projects, so I don’t have to re-read anything.

The habit of reading papers and learning how to organize research papers has made me a better researcher. It takes me much less time to read now, and I use it to improve my experiments. I used this system a lot when putting together my PhD fellowship application and my candidacy exam. In the future, I will thank myself for having the foresight to take these steps today before starting to write my dissertation.

I am curious to know how others organize their research papers since there is no “ right ” way. Feel free to comment, and we will update the post with any interesting responses!

Images courtesy : Classified vector created by storyset – www.freepik.com

Aruna Kumarasiri

Founder at Proactive Grad, Materials Engineer, Researcher, and turned author. In 2019, he started his professional carrier as a materials engineer with the continuation of his research studies. His exposure to both academic and industrial worlds has provided many opportunities for him to give back to young professionals.

Did You Enjoy This?

Then consider getting the ProactiveGrad newsletter. It's a collection of useful ideas, fresh links, and high-spirited shenanigans delivered to your inbox every two weeks.

I accept the Privacy Policy

Hand-picked related articles

Why do graduate students struggle to establish a productive morning routine? And how to handle it?

- March 17, 2024

How to stick to a schedule as a graduate student?

- October 10, 2023

The best note-taking apps for graduate students: How to choose the right note-taking app

- September 20, 2022

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Name *

Email *

Add Comment *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Post Comment

Your personal research assistant

Zotero is a free, easy-to-use tool to help you collect, organize, annotate, cite, and share research.

Available for Mac, Windows, Linux, and iOS

Just need to create a quick bibliography? Try ZoteroBib .

Meet Zotero.

Collect with a click..

Zotero automatically senses research as you browse the web. Need an article from JSTOR or a preprint from arXiv.org? A news story from the New York Times or a book from a library? Zotero has you covered, everywhere.

Organize your way.

Zotero helps you organize your research any way you want. You can sort items into collections and tag them with keywords. Or create saved searches that automatically fill with relevant materials as you work.

Cite in style.

Zotero instantly creates references and bibliographies for any text editor, and directly inside Word, LibreOffice, and Google Docs. With support for over 10,000 citation styles, you can format your work to match any style guide or publication.

Stay in sync.

Zotero can optionally synchronize your data across devices, keeping your files, notes, and bibliographic records seamlessly up to date. If you decide to sync, you can also always access your research from any web browser.

Collaborate freely.

Zotero lets you co-write a paper with a colleague, distribute course materials to students, or build a collaborative bibliography. You can share a Zotero library with as many people you like, at no cost.

Zotero is open source and developed by an independent, nonprofit organization that has no financial interest in your private information. With Zotero, you always stay in control of your own data.

Still not sure which program to use for your research? See why we think you should choose Zotero .

Ready to try Zotero?

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER COLUMN

- 07 July 2022

How to find, read and organize papers

- Maya Gosztyla 0

Maya Gosztyla is a PhD student in biomedical sciences at the University of California, San Diego.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

“I’ll read that later,” I told myself as I added yet another paper to my 100+ open browser tabs.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-01878-7

This is an article from the Nature Careers Community, a place for Nature readers to share their professional experiences and advice. Guest posts are encouraged .

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Related Articles

- Research management

Londoners see what a scientist looks like up close in 50 photographs

Career News 18 APR 24

Deadly diseases and inflatable suits: how I found my niche in virology research

Spotlight 17 APR 24

How young people benefit from Swiss apprenticeships

Researchers want a ‘nutrition label’ for academic-paper facts

Nature Index 17 APR 24

How we landed job interviews for professorships straight out of our PhD programmes

Career Column 08 APR 24

I dive for fish in the longest freshwater lake in the world

Female academics need more support — in China as elsewhere

Correspondence 16 APR 24

Postdoctoral Position

We are seeking highly motivated and skilled candidates for postdoctoral fellow positions

Boston, Massachusetts (US)

Boston Children's Hospital (BCH)

Qiushi Chair Professor

Distinguished scholars with notable achievements and extensive international influence.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Zhejiang University

ZJU 100 Young Professor

Promising young scholars who can independently establish and develop a research direction.

Head of the Thrust of Robotics and Autonomous Systems

Reporting to the Dean of Systems Hub, the Head of ROAS is an executive assuming overall responsibility for the academic, student, human resources...

Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (Guangzhou)

Head of Biology, Bio-island

Head of Biology to lead the discovery biology group.

BeiGene Ltd.

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Master Your Homework

- Do My Homework

Organizing Research Papers: A Step-by-Step Guide

Writing research papers can be an arduous task, especially when it comes to organizing the materials needed for a successful paper. In order to simplify this process, this article will provide a step-by-step guide on how to effectively organize your research papers. It will discuss topics such as where and how to store information, proper citing practices, effective note taking strategies and more in depth guidance that is essential for producing quality work. By following these instructions you will not only save time but also produce better results from your efforts in writing comprehensive research papers.

I. Introduction to Organizing Research Papers

Ii. benefits of an effective research paper organization system.

- III. Creating a Research Plan: A Step-by-Step Guide

IV. The Importance of Properly Formatting and Referencing Sources

V. utilizing index cards for topic outlining and categorization, vi. constructing file folders to store relevant materials efficiently, vii . conclusion: implementing structured strategies for long-term success.

Research papers can be a daunting task for any student. To make the process easier, it’s important to have an organized approach . A research paper organizer helps keep all of your notes and resources in one place so that you don’t miss anything or lose focus while writing. It also allows you to easily search for relevant information and quickly move between sources.

An easy way to start organizing is by using a basic outline format with headers and subheaders such as: I. Introduction; II. Background Information; III. Methodology & Results; IV Conclusion & Future Directions.

- The introduction should provide context on why the topic is being discussed and how your work relates.

- Background info should include prior works related to the topic from other authors, if applicable.

- Methodology outlines what data was collected, how it was analyzed, etc..

Maximizing the Outcomes of Research Paper Writing Organization is a crucial part in producing an effective research paper. Having a systematic system to structure one’s work will yield results that are both productive and efficient, especially when it comes to meeting deadlines. A research paper organizer can help organize ideas before committing them onto written form. This allows for more structured thought process with better clarity on which information should be included or excluded from the final product. The use of an organized approach can lead to higher-quality outputs as well as increased productivity overall due to less time spent revising after submission deadline passes. It is also easier for readers or evaluators of the document follow through its content if there exists a logical flow between sections instead of having all arguments scattered throughout the entire page without any tangible direction linking these together.

Furthermore, organizing one’s thoughts with the aid of devices such as color coding makes it simpler to navigate within texts by visually highlighting important points while potentially disregarding those that may not be necessary at first glance; allowing researchers better efficiency in identifying which areas need further examination or expansion upon during their writing journey thus creating an effective organizational tool for researchers looking improve their quality and increase output timeliness.

- Color Coding:

A simple yet highly useful organization technique used in arranging text.

- Research Paper Organizer:

Developing a Research Plan: Creating an effective research plan is essential for successful execution of the project. It involves formulating questions, selecting appropriate sources and materials, establishing timelines and budgets, and outlining tasks that need to be completed. Here is a step-by-step guide to help you create your own customized research plan:

- Establish Your Goals – Start by deciding what information or results you hope to gain from your project.

- Research Paper Organizer – Use this tool to keep track of references used in the paper as well as other relevant resources.

Organize Resources & Collect Data – Establish parameters for data collection (e.g., type of source material). Gather all relevant documents, reports, articles etc that support your goal objectives.

- Outline Tasks – Draft up a comprehensive list outlining steps necessary for completion.

Create Timeline/Set Deadlines – Set deadlines for each task along with due dates on key milestones such as drafts , revisions etc Finally , develop an efficient system so you can stay on top of everything . Monitor progress frequently while remaining flexible enough if changes have to be made midway through .

Correctly Citing Sources and Proper Formatting Enhance Academic Writing It is essential for students to properly cite sources when writing an academic paper. Proper citation allows readers to identify the origin of borrowed ideas, thoughts, and information used in a text. Additionally, correctly citing sources helps authors avoid accusations of plagiarism which can lead to serious consequences including failure on assignments or even expulsion from college. Referencing outside materials also provides authors with credibility since they are able to back up their work with reliable evidence that has been obtained by other well-respected professionals within a field of study. To ensure proper citations are utilized throughout an entire paper, writers should create a research paper organizer . This will help them remember all applicable references as well as provide them with accurate formatting information such as:

- The typeface size.

- Spacing between lines.

Moreover, correctly referencing sources can also add value to one’s own written work due it allowing others potential access into other related fields of research often generated by experts in those respective areas; thus providing readers with further points for consideration not originally included within the body itself. Therefore following correct source formats gives any writer additional insight into topics being discussed while strengthening his/her argument overall through useful contextual support sourced externally beyond their original scope of content generation alone.

Organizing Ideas with Index Cards Index cards are an excellent tool for organizing ideas and structuring research papers. Not only do they help keep information organized, but index cards also allow you to quickly move around pieces of your project as needed while keeping everything together in one place.

Using the right colors for different categories can make a big difference when it comes to sorting through data. For example, red could be used to designate all primary sources; yellow could denote secondary sources; green or blue might identify keywords associated with the topic being researched. Once each card has been properly labeled and categorized, using them becomes much easier because you know exactly where everything should go!

An easy way to organize multiple lines of thought is by writing a main idea on an individual card then taping several other related cards underneath it. This makes for quick access when trying to find certain notes at a later date – just flip over the original card and voila! It’s like having your own personal research paper organizer.

- Create separate sections in notebooks (or on digital documents) so that changes can be made without compromising existing work.

- Label each page according to its category—for instance: “Primary Sources” or “Secondary Sources”.

Having this system allows researchers not only track progress but easily refer back if necessary. Assembling topics into logical sequences is another key component when utilizing index cards during outlining stages — use numbering systems that connect subtopics under headings so they’re more cohesive upon completion

Organizing Your Research Materials

Research papers can quickly become overwhelming if materials are not stored in an organized manner. One of the most efficient ways to keep everything together is by constructing file folders for each research paper topic you cover. You can use any type of filing system such as manila files, plastic folders or online documents that all store information related to a particular project.

When making your folder, it’s important to remember what materials need to be included within the designated space. This may include:

- Drafts and outlines of research papers

- Notes from relevant books, articles and other sources

- Audio recordings from interviews conducted

Any items that could help further support your paper should also be saved along with these above materials – creating a comprehensive research paper organizer. Keep all physical copies in labeled manilla envelopes so they don’t get mixed up while digital versions can stay sorted on different drives or external hard disks. Having this organized will save time when having to refer back at some point during the writing process.

Structured strategies are essential for achieving long-term success in any endeavor. To that end, there have been a number of research studies exploring the various elements of successful strategy implementation.

- Motivation: What drives individuals and organizations to achieve success?

The key is not only setting realistic objectives but also having a comprehensive approach when it comes time for implementing those objectives. This requires an understanding of the particular context in which the organization finds itself—which means being aware of both internal and external factors such as technological advancements, changes in consumer tastes, or economic cycles—and taking steps toward bridging any gaps between current capabilities and desired outcomes. Companies should take a holistic view when constructing their strategies, making sure each element serves its own unique purpose while working together with others towards common goal attainment over time.

As this step-by-step guide to organizing research papers illustrates, a well thought out and organized approach can save time and ensure more successful research outcomes. By following the outlined steps from creating a preliminary structure to utilizing efficient information retrieval systems, researchers can easily refine their process in order to maximize productivity while still producing quality results. It is imperative that those conducting research remain cognizant of the importance of organization for not only successful completion but also for ethical considerations related to reproducibility and accuracy of data collection methods. Such intentional structuring should be applied consistently throughout all stages of the project’s lifecycle in order create greater efficiencies in both time management as well as resources used along the way—ultimately resulting in higher quality output with fewer missteps along the path toward success.

Organizing Academic Research Papers: Making an Outline

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Executive Summary

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tertiary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Annotated Bibliography

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- How to Manage Group Projects

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Essays

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Acknowledgements

An outline is a formal system used to develop a framework for thinking about what the eventual contents and organization of your paper should be. An outline helps you predict the overall structure and flow of a paper.

Importance of...

Writing papers in college requires you to come up with sophisticated, complex, and sometimes very creative ways of structuring your ideas . Taking the time to draft an outline can help you see whether your ideas connect to each other, what order of ideas works best, where gaps in your thinking may exist, or whether you have sufficient evidence to support each of your points.

A good outline is important because :

- You will be much less likely to get writer's block because an outline will show where you're going and what the next step is.

- It will help you stay organized and focused throughout the writing process and helps ensure a proper coherence [flow of ideas] in your final paper. However, the outline should be viewed as a guide, not a straitjacket.

- A clear, detailed outline ensures that you always have something to help re-calibrate your writing should you feel yourself drifting into subject areas unrelated to the larger research problem.

- The outline can be key to staying motivated . You can put together an outline when you're excited about the project and everything is clicking; making an outline is never as overwhelming as sitting down and beginning to write a twenty page paper without any sense of where it is going.

- An outline help you organize multiple ideas about a topic . Most research problems can be analyzed in any number of inter-related ways; an outline can help you sort out which modes of analysis are most appropriate or ensure the most robust findings.

How to Structure and Organize Your Paper . Odegaard Writing & Research Center. University of Washington.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Approaches

There are two general approaches you can take when writing an outline for your paper:

The topic outline consists of short phrases. This approach is useful when you are dealing with a number of different issues that could be arranged in a variety of different ways in your paper. Due to short phrases having more content than using simple sentences, they create better content from which to build your paper.

The sentence outline is done in full sentences. This approach is useful when your paper focuses on complex issues in detail. The sentence outline is also useful because sentences themselves have many of the details in them and it allows you to include those details in the sentences instead of having to create an outline of many short phrases that goes on page after page.

II. Steps to Making the Outline

A strong outline details each topic and subtopic in your paper, organizing these points so that they build your argument toward an evidence-based conclusion. Writing an outline will also help you focused on the task at hand and avoid unnecessary tangents, logical fallacies, and underdeveloped paragraphs.

- Identify the research problem . The research problem is the focal point from which the rest of the outline flows. Try to sum up the point of your paper in one sentence or phrase. It also can be key to deciding what the title of your paper should be.

- Identify the main categories . What main points will you analyze? The introduction describes all of your main points, the rest of your paper can be spent developing those points.

- Create the first category . What is the first point you want to cover? If the paper centers around a complicated term, a definition can be a good place to start. For a paper about a particular theory, giving the general background on the theory can be a good place to begin.

- Create subcategories . After you have the main point, create points under it that provide support for the main point. The number of categories that you use depends on the amount of information that you are trying to cover; there is no right or wrong number to use.

Once you have developed the basic outline of the paper, organize the contents to match the standard format of a research paper as described in this guide.

III. Things to Consider When Writing an Outline

- There is no rule dictating which approach is best . Choose either a topic outline or a sentence outline based on which one you believe will work best for you. However, once you begin developing an outline, it's helpful to stick to only one approach.

- Both topic and sentence outlines use Roman and Arabic numerals along with capital and small letters of the alphabet arranged in a consistent and rigid sequence. A rigid format should be used especially if you are required to hand in your outline.

- Although the format of an outline is rigid, it shouldn't make you inflexible about how to write your paper. Often when you start investigating a research problem [i.e., reviewing the research literature], especially if you are unfamiliar with the topic, you should anticipate the likelihood your analysis could go in different directions. If your paper changes focus, or you need to add new sections, then feel free to reorganize the outline.

- If appropriate, organize the main points of your outline in chronological order . In papers where you need to trace the history or chronology of events or issues, it is important to arrange your outline in the same manner, knowing that it's easier to re-arrange things now than when you've almost finished your paper.

- For a standard research paper of 15-20 pages, your outline should be no more than four pages in length . It may be helpful as your are developing your outline to also jot down a tentative list of references.

Four Main Components for Effective Outlines. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; How to Make an Outline. Psychology Writing Center. University of Washington; Organization: Informal Outlines . The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Organization: Standard Outline Form . The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Outlining. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University; Plotnic, Jerry. Organizing an Essay . University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Reverse Outline . The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Reverse Outlines: A Writer's Technique for Examining Organization . The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Using Outlines. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University; Writing: Considering Structure and Organization . Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College.

Writing Tip

A Disorganized Outline Means a Disorganized Paper!

If, in writing your paper, it begins to diverge from your outline, this is very likely a sign that you've lost your focus. How do you know whether to change the paper to fit the outline, or, that you need to reconsider the outline so that fits the paper? A good way to check yourself is to use what you have written to recreate the outline. This is an effective strategy for assessing the organization of your paper. If the resulting outline says what you want it to say and it is in an order that is easy to follow, then the organization of your paper has been successful. If you discover that it's difficult to create an outline from what you have written, then you likely need to revise your paper.

- << Previous: Choosing a Title

- Next: Paragraph Development >>

- Last Updated: Jul 18, 2023 11:58 AM

- URL: https://library.sacredheart.edu/c.php?g=29803

- QuickSearch

- Library Catalog

- Databases A-Z

- Publication Finder

- Course Reserves

- Citation Linker

- Digital Commons

- Our Website

Research Support

- Ask a Librarian

- Appointments

- Interlibrary Loan (ILL)

- Research Guides

- Databases by Subject

- Citation Help

Using the Library

- Reserve a Group Study Room

- Renew Books

- Honors Study Rooms

- Off-Campus Access

- Library Policies

- Library Technology

User Information

- Grad Students

- Online Students

- COVID-19 Updates

- Staff Directory

- News & Announcements

- Library Newsletter

My Accounts

- Interlibrary Loan

- Staff Site Login

FIND US ON

- 9 Free Online Earth Day Games for Kids

- The Best Gadgets for The Beach or Pool

15 Best Free Web Tools to Organize Your Research

How to stay organized when researching and writing papers

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/tim-fisher-5820c8345f9b581c0b5a63cf.jpg)

- Emporia State University

- Cloud Services

- Error Messages

- Family Tech

- Home Networking

- Around the Web

Organizing research is important not only for your own sanity, but because when it comes time to unfold the data and put it to use, you want the process to go as smoothly as possible. This is where research organizers come in.

There are lots of free web-based organizers that you can use for any purpose. Maybe you're collecting interviews for a news story, digging up newspaper archives for a history project, or writing a research paper over a science topic. Research organizers are also helpful for staying productive and preparing for tests.

Regardless of the topic, when you have multiple sources of information and lots to comb through later, optimizing your workflow with a dedicated organizer is essential.

Patrick Tomasso / Unsplash

Many of these tools provide unique features, so you might decide to use multiple resources simultaneously in whatever way suits your particular needs.

Research and Study

You need a place to gather the information you're finding. To avoid a cluttered space when collecting and organizing data, you can use a tool dedicated to research.

- Pocket : Save web pages to your online account to reference them again later. It's much tidier than bookmarks, and it can all be retrieved from the web or the Pocket mobile app .

- Mendeley : Organize papers and references, and generate citations and bibliographies.

- Quizlet : Learn vocabulary with these free online flashcards .

- Wikipedia : Find information on millions of different topics.

- Quora : This is a question and answer website where you can ask the community for help with any question.

- SparkNotes : Free online study guides on a wide variety of subjects, anything from famous literary works of the past century to the present day.

- Zotero : Collect, manage, and cite your research sources. Lets you organize data into collections and search through them by adding tags to every source. This is a computer program, but there's a browser extension that helps you send data to it.

- Google Scholar : A simple way to search for scholarly literature on any subject.

- Diigo : Collect, share, and interact with information from anywhere on the web. It's all accessible through the browser extension and saved to your online account.

- GoConqr : Create flashcards, mind maps, notes, quizzes, and more to bridge the gap between your research and studying.

Writing Tools

Writing is the other half of a research paper, so you need somewhere useful to go to jot down notes, record information you might use in the final paper, create drafts, track sources, and finalize the paper.

- Web Page Sticky Notes : For Chrome users, this tool lets you place sticky notes on any web page as you do your research. There are tons of settings you can customize, they're backed up to your Google Drive account, and they're visible not only on each page you created them on but also on a single page from the extension's settings.

- Google Docs or Word Online : These are online word processors where you can write the entire research paper, organize lists, paste URLs, store off-hand notes, and more.

- Google Keep : This note-taking app and website catalogs notes within labels that make sense for your research. Access them from the web on any computer or from your mobile device. It supports collaborations, custom colors, images, drawings, and reminders.

- Yahoo Notepad : If you use Yahoo Mail , the notes area of your account is a great place to store text-based snippets for easy recall when you need them.

- Notion : Workflows, notes, and more, in a space where you can collaborate with others.

Get the Latest Tech News Delivered Every Day

- The 10 Best Bookmarking Tools for the Web

- The 10 Best Free Online Classes for Adults in 2024

- The 8 Best Search Engines of 2024

- 17 Best Sites to Download Free Books in 2024

- 5 Best Free Online Word Processors for 2024

- The 10 Best Note Taking Apps of 2024

- The 8 Best Free Genealogy Websites of 2024

- The 10 Best Chrome Extensions for Android in 2024

- The 10 Best Productivity Apps of 2024

- The 10 Best Writing Apps of 2024

- The Best Brainstorming Tools for 2024

- The Best Mac Shortcuts in 2024

- The 10 Best Word Processing Apps for iPad in 2024

- The 20 Best Free iPhone Apps of 2024

- The 15 Best Free AI Courses of 2024

- The Top 10 Internet Browsers for 2024

- How to write a research paper

Last updated

11 January 2024

Reviewed by

With proper planning, knowledge, and framework, completing a research paper can be a fulfilling and exciting experience.

Though it might initially sound slightly intimidating, this guide will help you embrace the challenge.

By documenting your findings, you can inspire others and make a difference in your field. Here's how you can make your research paper unique and comprehensive.

- What is a research paper?

Research papers allow you to demonstrate your knowledge and understanding of a particular topic. These papers are usually lengthier and more detailed than typical essays, requiring deeper insight into the chosen topic.

To write a research paper, you must first choose a topic that interests you and is relevant to the field of study. Once you’ve selected your topic, gathering as many relevant resources as possible, including books, scholarly articles, credible websites, and other academic materials, is essential. You must then read and analyze these sources, summarizing their key points and identifying gaps in the current research.

You can formulate your ideas and opinions once you thoroughly understand the existing research. To get there might involve conducting original research, gathering data, or analyzing existing data sets. It could also involve presenting an original argument or interpretation of the existing research.

Writing a successful research paper involves presenting your findings clearly and engagingly, which might involve using charts, graphs, or other visual aids to present your data and using concise language to explain your findings. You must also ensure your paper adheres to relevant academic formatting guidelines, including proper citations and references.

Overall, writing a research paper requires a significant amount of time, effort, and attention to detail. However, it is also an enriching experience that allows you to delve deeply into a subject that interests you and contribute to the existing body of knowledge in your chosen field.

- How long should a research paper be?

Research papers are deep dives into a topic. Therefore, they tend to be longer pieces of work than essays or opinion pieces.

However, a suitable length depends on the complexity of the topic and your level of expertise. For instance, are you a first-year college student or an experienced professional?

Also, remember that the best research papers provide valuable information for the benefit of others. Therefore, the quality of information matters most, not necessarily the length. Being concise is valuable.

Following these best practice steps will help keep your process simple and productive:

1. Gaining a deep understanding of any expectations

Before diving into your intended topic or beginning the research phase, take some time to orient yourself. Suppose there’s a specific topic assigned to you. In that case, it’s essential to deeply understand the question and organize your planning and approach in response. Pay attention to the key requirements and ensure you align your writing accordingly.

This preparation step entails

Deeply understanding the task or assignment

Being clear about the expected format and length

Familiarizing yourself with the citation and referencing requirements

Understanding any defined limits for your research contribution

Where applicable, speaking to your professor or research supervisor for further clarification

2. Choose your research topic

Select a research topic that aligns with both your interests and available resources. Ideally, focus on a field where you possess significant experience and analytical skills. In crafting your research paper, it's crucial to go beyond summarizing existing data and contribute fresh insights to the chosen area.

Consider narrowing your focus to a specific aspect of the topic. For example, if exploring the link between technology and mental health, delve into how social media use during the pandemic impacts the well-being of college students. Conducting interviews and surveys with students could provide firsthand data and unique perspectives, adding substantial value to the existing knowledge.

When finalizing your topic, adhere to legal and ethical norms in the relevant area (this ensures the integrity of your research, protects participants' rights, upholds intellectual property standards, and ensures transparency and accountability). Following these principles not only maintains the credibility of your work but also builds trust within your academic or professional community.